Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Karoline von Günderrode

(1780 – 1806)

Tendenz des Künstlers

Sage! was treibt doch den Künstler, sein Ideal aus dem Lande

Der Ideen zu ziehn, und es dem Stoff zu vertraun?

Schöner wird ihm sein Bilden gelingen im Reich der Gedanken,

Wäre es flüchtiger zwar, dennoch auch freier dafür,

Und sein Eigenthum mehr, und nicht dem Stoff unterthänig.

Frager! der du so fragst, du verstehst nicht des Geistes Beginnen,

Siehst nicht was er erstrebt, nicht was der Künstler ersehnt.

Alle! sie wollen unsterbliches thun, die sterblichen Menschen.

Leben im Himmel die Frommen, in guten Thaten die Guten,

Bleibend will sein der Künstler im Reiche der Schönheit,

Darum in dauernder Form stellt den Gedanken er dar.

Karoline Günderrode Gedichte

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Karoline von Günderrode

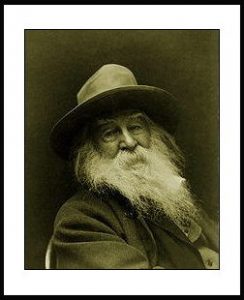

Walt Whitman

(1819 – 1892)

“So Long!”

1

To conclude–I announce what comes after me;

I announce mightier offspring, orators, days, and then depart,

I remember I said, before my leaves sprang at all,

I would raise my voice jocund and strong, with reference to consummations.

When America does what was promised,

When there are plentiful athletic bards, inland and sea-board,

When through these States walk a hundred millions of superb persons,

When the rest part away for superb persons, and contribute to them,

When breeds of the most perfect mothers denote America,

Then to me my due fruition.

I have pressed through in my own right,

I have offered my style to every one–I have journeyed with confident step.

While my pleasure is yet at the full, I whisper, ” So long!”

And take the young woman’s hand, and the young man’s hand for the last

time.

2

I announce natural persons to arise,

I announce justice triumphant,

I announce uncompromising liberty and equality,

I announce the justification of candour, and the justification of pride.

I announce that the identity of these States is a single identity only,

I announce the Union, out of all its struggles and wars, more and more

compact,

I announce splendours and majesties to make all the previous politics of

the earth insignificant.

I announce a man or woman coming–perhaps you are the one (“So long!”)

I announce the great individual, fluid as Nature, chaste, affectionate,

compassionate, fully armed.

I announce a life that shall be copious, vehement, spiritual, bold,

And I announce an old age that shall lightly and joyfully meet its

translation.

3

O thicker and faster! (“So long!”)

O crowding too close upon me;

I foresee too much–it means more than I thought,

It appears to me I am dying.

Hasten throat, and sound your last!

Salute me–salute the days once more. Peal the old cry once more.

Screaming electric, the atmosphere using,

At random glancing, each as I notice absorbing,

Swiftly on, but a little while alighting,

Curious enveloped messages delivering,

Sparkles hot, seed ethereal, down in the dirt dropping,

Myself unknowing, my commission obeying, to question it never daring,

To ages, and ages yet, the growth of the seed leaving,

To troops out of me rising–they the tasks I have set promulging,

To women certain whispers of myself bequeathing–their affection me more

clearly explaining,

To young men my problems offering–no dallier I–I the muscle of their

brains trying,

So I pass–a little time vocal, visible, contrary,

Afterward, a melodious echo, passionately bent for–death making me really

undying,–

The best of me then when no longer visible–for toward that I have been

incessantly preparing.

What is there more, that I lag and pause, and crouch extended with unshut

mouth?

Is there a single final farewell?

4

My songs cease–I abandon them,

From behind the screen where I hid, I advance personally, solely to you.

Camerado! This is no book;

Who touches this touches a man.

(Is it night? Are we here alone?)

It is I you hold, and who holds you,

I spring from the pages into your arms–decease calls me forth.

O how your fingers drowse me!

Your breath falls around me like dew–your pulse lulls the tympans of my

ears,

I feel immerged from head to foot,

Delicious–enough.

Enough, O deed impromptu and secret!

Enough, O gliding present! Enough, O summed-up past!

5

Dear friend, whoever you are, here, take this kiss,

I give it especially to you–Do not forget me,

I feel like one who has done his work–I progress on,–(long enough have I

dallied with Life,)

The unknown sphere, more real than I dreamed, more direct, awakening rays

about me–“So long!”

Remember my words–I love you–I depart from materials,

I am as one disembodied, triumphant, dead.

Walt Whitman poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive W-X, Whitman, Walt

William Shakespeare

(1564-1616)

Now is the winter of our discontent

Now is the winter of our discontent

Made glorious summer by this sun of York,

And all the clouds that loured upon our house

In the deep bosom of the ocean buried.

Now are our brows bound with victorious wreaths,

Our bruised arms hung up for monuments,

Our stern alarums changed to merry meetings,

Our dreadful marches to delightful measures.

Grim-visaged war hath smoothed his wrinkled front;

And now, instead of mounting barbed steeds

To fright the souls of fearful adversaries,

He capers nimbly in a lady’s chamber

To the lascivious pleasing of a lute.

But I, that am not shaped for sportive tricks,

Nor made to court an amorous looking-glass;

I, that am rudely stamped, and want love’s majesty

To strut before a wanton ambling nymph;

I, that am curtailed of this fair proportion,

Cheated of feature by dissembling nature,

Deformed, unfinished, sent before my time

Into this breathing world, scarce half made up,

And that so lamely and unfashionable

That dogs bark at me as I halt by them,–

Why, I, in this weak piping time of peace,

Have no delight to pass away the time,

Unless to spy my shadow in the sun.

William Shakespeare, “King Richard III”, Act 1 scene 1

Shakespeare 400 (1616 – 2016)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: 4SEASONS#Winter, Archive S-T, Shakespeare, William

Feuille d’Album

by Katherine Mansfield

He really was an impossible person. Too shy altogether. With absolutely nothing to say for himself. And such a weight. Once he was in your studio he never knew when to go, but would sit on and on until you nearly screamed, and burned to throw something enormous after him when he did finally blush his way out-something like the tortoise stove. The strange thing was that at first sight he looked most interesting. Everybody agreed about that.

You would drift into the café one evening and there you would see, sitting in a corner, with a glass of coffee in front of him, a thin dark boy, wearing a blue jersey with a little grey flannel jacket buttoned over it. And somehow that blue jersey and the grey jacket with the sleeves that were too short gave him the air of a boy that has made up his mind to run away to sea. Who has run away, in fact, and will get up in a moment and sling a knotted handkerchief containing his nightshirt and his mother’s picture on the end of a stick, and walk out into the night and be drowned. . . . Stumble over the wharf edge on his way to the ship, even. . . . He had black close-cropped hair, grey eyes with long lashes, white cheeks and a mouth pouting as though he were determined not to cry. . . . How could one resist him? Oh, one’s heart was wrung at sight. And, as if that were not enough, there was his trick of blushing. . . . Whenever the waiter came near him he turned crimson-he might have been just out of prison and the waiter in the know . . . .

“Who is he, my dear? Do you know?”

“Yes. His name is Ian French. Painter. Awfully clever, they say. Someone started by giving him a mother’s tender care. She asked him how often he heard from home, whether he had enough blankets on his bed, how much milk he drank a day. But when she went round to his studio to give an eye to his socks, she rang and rang, and though she could have sworn she heard someone breathing inside, the door was not answered. . . . Hopeless!”

Someone else decided that he ought to fall in love. She summoned him to her side, called him “boy,” leaned over him so that he might smell the enchanting perfume of her hair, took his arm, told him how marvellous life could be if one only had the courage, and went round to his studio one evening and rang and rang. . . . Hopeless.

“What the poor boy really wants is thoroughly rousing,” said a third. So off they went to café’s and cabarets, little dances, places where you drank something that tasted like tinned apricot juice, but cost twenty-seven shillings a bottle and was called champagne, other places, too thrilling for words, where you sat in the most awful gloom, and where someone had always been shot the night before. But he did not turn a hair. Only once he got very drunk, but instead of blossoming forth, there he sat, stony, with two spots of red on his cheeks, like, my dear, yes, the dead image of that rag-time thing they were playing, like a “Broken Doll.” But when she took him back to his studio he had quite recovered, and said “good night” to her in the street below, as though they had walked home from church together. . . . Hopeless.

After heaven knows how many more attempts-for the spirit of kindness dies very hard in women-they gave him up. Of course, they were still perfectly charming, and asked him to their shows, and spoke to him in the café but that was all. When one is an artist one has no time simply for people who won’t respond. Has one?

“And besides I really think there must be something rather fishy somewhere . . . don’t you? It can’t all be as innocent as it looks! Why come to Paris if you want to be a daisy in the field? No, I’m not suspicious. But –”

He lived at the top of a tall mournful building overlooking the river. One of those buildings that look so romantic on rainy nights and moonlight nights, when the shutters are shut, and the heavy door, and the sign advertising “a little apartment to let immediately” gleams forlorn beyond words. One of those buildings that smell so unromantic all the year round, and where the concierge lives in a glass cage on the ground floor, wrapped up in a filthy shawl, stirring something in a saucepan and ladling out tit-bits to the swollen old dog lolling on a bead cushion. . . . Perched up in the air the studio had a wonderful view. The two big windows faced the water; he could see the boats and the barges swinging up and down, and the fringe of an island planted with trees, like a round bouquet. The side window looked across to another house, shabbier still and smaller, and down below there was a flower market. You could see the tops of huge umbrellas, with frills of bright flowers escaping from them, booths covered with striped awning where they sold plants in boxes and clumps of wet gleaming palms in terra-cotta jars. Among the flowers the old women scuttled from side to side, like crabs. Really there was no need for him to go out. If he sat at the window until his white beard fell over the sill he still would have found something to draw . . . .

How surprised those tender women would have been if they had managed to force the door. For he kept his studio as neat as a pin. Everything was arranged to form a pattern, a little “still life” as it were-the saucepans with their lids on the wall behind the gas stove, the bowl of eggs, milk jug and teapot on the shelf, the books and the lamp with the crinkly paper shade on the table. An Indian curtain that had a fringe of red leopards marching round it covered his bed by day, and on the wall beside the bed on a level with your eyes when you were lying down there was a small neatly printed notice: GET UP AT ONCE.

Every day was much the same. While the light was good he slaved at his painting, then cooked his meals and tidied up the place. And in the evenings he went off to the café, or sat at home reading or making out the most complicated list of expenses headed: “What I ought to be able to do it on,” and ending with a sworn statement . . . “I swear not to exceed this amount for next month. Signed, Ian French.”

Nothing very fishy about this; but those far-seeing women were quite right. It wasn’t all.

One evening he was sitting at the side window eating some prunes and throwing the stones on to the tops of the huge umbrellas in the deserted flower market. It had been raining – the first real spring rain of the year had fallen-a bright spangle hung on everything, and the air smelled of buds and moist earth. Many voices sounding languid and content rang out in the dusky air, and the people who had come to close their windows and fasten the shutters leaned out instead. Down below in the market the trees were peppered with new green. What kind of trees were they? he wondered. And now came the lamplighter. He stared at the house across the way, the small, shabby house, and suddenly, as if in answer to his gaze, two wings of windows opened and a girl came out on to the tiny balcony carrying a pot of daffodils. She was a strangely thin girl in a dark pinafore, with a pink handkerchief tied over her hair. Her sleeves were rolled up almost to her shoulders and her slender arms shone against the dark stuff.

“Yes, it is quite warm enough. It will do them good,” she said, puffing down the pot and turning to someone in the room inside. As she turned she put her hands up to the handkerchief and tucked away some wisps of hair. She looked down at the deserted market and up at the sky, but where he sat there might have been a hollow in the air. She simply did not see the house opposite. And then she disappeared.

His heart fell out of the side window of his studio, and down to the balcony of the house opposite-buried itself in the pot of daffodils under the half-opened buds and spears of green. . . . That room with the balcony was the sitting-room, and the one next door to it was the kitchen. He heard the clatter of the dishes as she washed up after supper, and then she came to the window, knocked a little mop against the ledge, and hung it on a nail to dry. She never sang or unbraided her hair, or held out her arms to the moon as young girls are supposed to do. And she always wore the same dark pinafore and the pink handkerchief over her hair. . . . Whom did she live with? Nobody else came to those two windows, and yet she was always talking to someone in the room. Her mother, he decided, was an invalid. They took in sewing. The father was dead. . . . He had been a journalist-very pale, with long moustaches, and a piece of black hair falling over his forehead.

By working all day they just made enough money to live on, but they never went out and they had no friends. Now when he sat down at his table he had to make an entirely new set of sworn statements. . . . Not to go to the side window before a certain hour: signed, Ian French. Not to think about her until he had put away his painting things for the day: signed, Ian French.

It was quite simple. She was the only person he really wanted to know, because she was, he decided, the only other person alive who was just his age. He couldn’t stand giggling girls, and he had no use for grown-up women. . . . She was his age, she was-well, just like him. He sat in his dusky studio, tired, with one arm hanging over the back of his chair, staring in at her window and seeing himself in there with her. She had a violent temper; they quarrelled terribly at times, he and she. She had a way of stamping her foot and twisting her hands in her pinafore . . . furious. And she very rarely laughed. Only when she told him about an absurd little kitten she once had who used to roar and pretend to be a lion when it was given meat to eat. Things like that made her laugh. . . . But as a rule they sat together very quietly; he, just as he was sitting now, and she with her hands folded in her lap and her feet tucked under, talking in low tones, or silent and tired after the day’s work. Of course, she never asked him about his pictures, and of course he made the most wonderful drawings of her which she hated, because he made her so thin and so dark. . . . But how could he get to know her? This might go on for years . . . .

Then he discovered that once a week, in the evenings, she went out shopping. On two successive Thursdays she came to the window wearing an old-fashioned cape over the pinafore, and carrying a basket. From where he sat he could not see the door of her house, but on the next Thursday evening at the same time he snatched up his cap and ran down the stairs. There was a lovely pink light over everything. He saw it glowing in the river, and the people walking towards him had pink faces and pink hands.

He leaned against the side of his house waiting for her and he had no idea of what he was going to do or say. “Here she comes,” said a voice in his head. She walked very quickly, with small, light steps; with one hand she carried the basket, with the other she kept the cape together. . . . What could he do? He could only follow. . . . First she went into the grocer’s and spent a long time in there, and then she went into the butcher’s where she had to wait her turn. Then she was an age at the draper’s matching something, and then she went to the fruit shop and bought a lemon. As he watched her he knew more surely than ever he must get to know her, now. Her composure, her seriousness and her loneliness, the very way she walked as though she was eager to be done with this world of grown-ups all was so natural to him and so inevitable.

“Yes, she is always like that,” he thought proudly. “We have nothing to do with-these people.”

But now she was on her way home and he was as far off as ever. . . . She suddenly turned into the dairy and he saw her through the window buying an egg. She picked it out of the basket with such care-a brown one, a beautifully shaped one, the one he would have chosen. And when she came out of the dairy he went in after her. In a moment he was out again, and following her past his house across the flower market, dodging among the huge umbrellas and treading on the fallen flowers and the round marks where the pots had stood. . . . Through her door he crept, and up the stairs after, taking care to tread in time with her so that she should not notice. Finally, she stopped on the landing, and took the key out of her purse. As she put it into the door he ran up and faced her.

Blushing more crimson than ever, but looking at her severely he said, almost angrily: “Excuse me, Mademoiselle, you dropped this.”

And he handed her an egg.

Feuille d’Album

by Katherine Mansfield (1888 – 1923)

From: Bliss, and other stories

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive M-N, DRUGS & DISEASE & MEDICINE & LITERATURE, Katherine Mansfield, Mansfield, Katherine

Rainer Maria Rilke

(1875 – 1926)

Die Kathedrale

In jenen kleinen Städten, wo herum

die alten Häuser wie ein Jahrmarkt hocken

der sie bemerkt hat plötzlich und, erschrocken,

die Buden zumacht und, ganz zu und stumm,

die Schreier still, die Trommel angehalten,

zu ihr hinaufhorcht aufgeregten Ohrs –

dieweil sie ruhig immer in dem alten

Faltenmantel ihrer Contreforts

dasteht und von den Häusern gar nicht weiß:

in jenen kleinen Städten kannst du sehn,

wie sehr entwachsen ihrem Umgangskreis

die Kathedralen waren. Ihr Erstehn

ging über alles fort, so wie den Blick

des eignen Lebens viel zu große Nähe

fortwährend übersteigt, und als geschähe

nichts anderes; als wäre Das Geschick,

was sich in ihnen aufhäuft ohne Maßen,

versteinert und zum Dauernden bestimmt,

nicht Das, was unten in den dunkeln Straßen

vom Zufall irgendwelche Namen nimmt

und darin geht, wie Kinder Grün und Rot

und was der Krämer hat als Schürze tragen.

Da war Geburt in diesen Unterlagen,

und Kraft und Andrang war in diesem Ragen

und Liebe überall wie Wein und Brot,

und die Portale voller Liebesklagen.

Das Leben zögerte im Stundenschlagen,

und in den Türmen, welche voll Entsagen

auf einmal nicht mehr stiegen, war der Tod.

Rainer Maria Rilke Gedichte

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive Q-R, Rilke, Rainer Maria

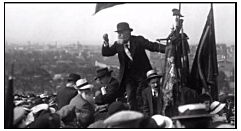

Jean Jaurès

(1859 – 1914)

Sous les étoiles

La prairie où reluisent les brins d’herbe et les fleurs semble,

dans les jours d’été, je ne sais quelle couche plus épaisse et

plus grasse de clarté déposée tout au fond d’un océan infini de

lumière subtile. De même, dans les nuits baignées de lune, les

étoiles sont comme des gouttes de lumière concentrée en un

lac de limpidité légère.

Jean Jaurès poésie

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive I-J, Jaurès, Jean

alma-tadema (1836 – 1912)

de meest succesvolle schilder van de 19e eeuw

Verleidelijke Romeinse vrouwen gesluierd in fijne gewaden tegen dromerige vergezichten, mijmerende geliefden op bijna doorschijnend marmeren bankjes en dames die hun tijd doorbrengen met pootjebaden, vissen voeren en luieren. Maar ook een farao met zijn stervende zoon in zijn armen en een nietsvermoedend feestend gezelschap dat elk moment verstikt gaat worden onder een lawine van rozenblaadjes. Alma-Tadema neemt ons mee naar scenes uit de klassieke oudheid en brengt deze tijd, als eerste, echt tot leven. Hij verbeeldt de oudheid zo mooi en overtuigend, dat regisseurs zijn schilderijen gebruiken als blauwdruk voor spektakelfilms als Gladiator. Uit heel de wereld komen meer dan tachtig topschilderijen van een van de meest succesvolle schilders van de 19de eeuw naar Leeuwarden. Samen met persoonlijke voorwerpen en filmfragmenten geven zij een inkijk in zijn wereld.

van lourens naar sir lawrence

Alma-Tadema wordt in 1836 geboren als de Friese Lourens. Na zijn opleiding aan de kunstacademie in Antwerpen vertrekt hij voor de liefde naar Londen, waar hij zich laat naturaliseren tot Engelsman en zichzelf Lawrence gaat noemen. Al snel wordt hij ontdekt door het grote publiek en zijn roem is ongekend, vooral in Engeland en Amerika. In 1899 wordt hij zelfs geridderd en gaat voortaan als Sir door het leven. Alma-Tadema stierf in 1912 en ligt begraven in de St. Paul’s Cathedral in Londen.

wereldfaam

Tijdens zijn leven wordt Alma-Tadema wereldberoemd met zijn werk. Hij schildert in opdracht van welgestelde zakenlieden en weet als geen ander zijn netwerk te cultiveren. Als een ware entertainer vermaakt hij op chique soirees de Londense high society. De opdrachten blijven binnenstromen en Tadema verdient een fortuin. Zo wordt hij een van de meest succesvolle schilders van de 19de eeuw. Ook tegenwoordig zijn werken van de geridderde schilder in het bezit van grote namen als George Lucas, de steenrijke Amerikaanse William Vanderbilt, de Getty familie, Andrew Lloyd Webber en Jack Nicholson. Zelfs ons koningshuis is de trotste eigenaar van een Tadema.

tadema en hollywood

Sinds zijn huwelijksreis naar Rome en Pompeï is Alma-Tadema gefascineerd door de klassieke oudheid. Hij is de eerste schilder die deze tijd met zoveel zorg en precisie in beeld brengt. Menig regisseur baseert zich op zijn schilderijen bij het maken van historische blockbusters zoals The Ten Commandments(1956). Ook nu nog; Tadema’s werk is een directe inspiratiebron voor Ridley Scott voor Gladiator (2000). In de tentoonstelling wordt glashelder hoe Tadema de filmwereld heeft beïnvloed. Daarnaast is er een bijpassend filmprogramma in samenwerking met Slieker Film en EYE filmmuseum.

grootste collectie

Het museum beschikte al over de grootste Alma-Tadema-collectie van Nederland, deels gekregen van Alma-Tadema en zijn dochters Laurence en Anna. In het najaar van 2015 doet het Fries Museum de grootste aankoop uit de historie van het museum: Tadema’s Entrance of the theatre. Door deze aankoop kan het Fries Museum als enige museum in Nederland de volledige ontwikkeling tonen die de schilder in zijn carrière doormaakte.

audiotour

Alma-Tadema wekt met zijn schilderijen verhalen uit de oudheid tot leven. Maar welke verhalen vertelt hij eigenlijk en welke symboliek schuilt er achter de objecten die we in zijn werken zien? In een levendige audiotour vertelt acteur Peter Tuinman je alles over zeventien hoogtepunten van de tentoonstelling. Je kiest zelf over welke schilderijen je meer wilt horen waardoor je in alle vrijheid door de tentoonstelling kunt lopen. De verhalentour kost slechts € 1,- per persoon en is ook online te reserveren. Voor buitenlandse bezoekers is er een Engelstalige Storytour beschikbaar.

Het Fries Museum heeft voor deze vernieuwende tentoonstelling over Alma-Tadema de Turing Toekenning 2015 gewonnen. De Turing Foundation kent deze prijs ter waarde van 500.000 euro eens in de twee jaar toe voor het beste tentoonstellingsplan van een Nederlands museum.

De tentoonstelling Alma-Tadema, klassieke verleiding is onderdeel van Leeuwarden-Fryslân Culturele Hoofdstad van Europa 2018. Voor deze tentoonstelling en het begeleidende filmprogramma werkt het Fries Museum samen met EYE filmmuseum en Slieker Film.

Alma-Tadema – klassieke verleiding is nog te zien tot en met 7 februari 2017.

Fries Museum

Wilhelminaplein 92

8911 BS Leeuwarden

T: 058 255 55 00

# Meer info op website friesmuseum

fleurdumal.nl magazine

More in: *The Pre-Raphaelites Archive, Art & Literature News, Exhibition Archive, The Ideal Woman, The talk of the town

Hart Crane

(1889 – 1932)

To Brooklyn Bridge

How many dawns, chill from his rippling rest

The seagull’s wings shall dip and pivot him,

Shedding white rings of tumult, building high

Over the chained bay waters Liberty–

Then, with inviolate curve, forsake our eyes

As apparitional as sails that cross

Some page of figures to be filed away;

–Till elevators drop us from our day . . .

I think of cinemas, panoramic sleights

With multitudes bent toward some flashing scene

Never disclosed, but hastened to again,

Foretold to other eyes on the same screen;

And Thee, across the harbor, silver-paced

As though the sun took step of thee, yet left

Some motion ever unspent in thy stride,–

Implicitly thy freedom staying thee!

Out of some subway scuttle, cell or loft

A bedlamite speeds to thy parapets,

Tilting there momently, shrill shirt ballooning,

A jest falls from the speechless caravan.

Down Wall, from girder into street noon leaks,

A rip-tooth of the sky’s acetylene;

All afternoon the cloud-flown derricks turn . . .

Thy cables breathe the North Atlantic still.

And obscure as that heaven of the Jews,

Thy guerdon . . . Accolade thou dost bestow

Of anonymity time cannot raise:

Vibrant reprieve and pardon thou dost show.

O harp and altar, of the fury fused,

(How could mere toil align thy choiring strings!)

Terrific threshold of the prophet’s pledge,

Prayer of pariah, and the lover’s cry,–

Again the traffic lights that skim thy swift

Unfractioned idiom, immaculate sigh of stars,

Beading thy path–condense eternity:

And we have seen night lifted in thine arms.

Under thy shadow by the piers I waited;

Only in darkness is thy shadow clear.

The City’s fiery parcels all undone,

Already snow submerges an iron year . . .

O Sleepless as the river under thee,

Vaulting the sea, the prairies’ dreaming sod,

Unto us lowliest sometime sweep, descend

And of the curveship lend a myth to God.

Hart Crane poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Crane, Hart

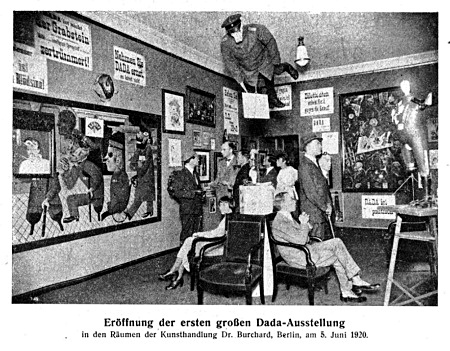

De Nacht van DADA viert zaterdag 3 december 2016 in DE Studio de 100ste verjaardag van de explosieve kunstbeweging met optredens van BLIXA BARGELD en een ontregeld leger artiesten. Let’s DADA! VONK & Zonen en Villanella presenteren op zaterdag 3 december de Nacht van DADA in DE Studio. Deze festivalnacht staat helemaal in het teken van 100 jaar dada, de anarchistische en explosieve kunstbeweging die Europa in vuur en vlam zette kort na de eerste wereldoorlog. VONK & Zonen verzamelde een ontregeld leger artiesten die de DADA-geest uit de fles laten die in gesprek gaat met deze woelige tijden.

De Nacht van DADA viert zaterdag 3 december 2016 in DE Studio de 100ste verjaardag van de explosieve kunstbeweging met optredens van BLIXA BARGELD en een ontregeld leger artiesten. Let’s DADA! VONK & Zonen en Villanella presenteren op zaterdag 3 december de Nacht van DADA in DE Studio. Deze festivalnacht staat helemaal in het teken van 100 jaar dada, de anarchistische en explosieve kunstbeweging die Europa in vuur en vlam zette kort na de eerste wereldoorlog. VONK & Zonen verzamelde een ontregeld leger artiesten die de DADA-geest uit de fles laten die in gesprek gaat met deze woelige tijden.

De Nacht van DADA wordt geopend door een uurlange ‘Solo Vocal Performance’ van BLIXA BARGELD. Hij ontleende niet voor niets zijn artiestennaam van de Duitse dichter en kunstenaar Johannes Theodor Baargeld (actief in de dadagroep in Keulen). Bargeld brengt een vocale performance in de geest van Kurt Schwitters. Daarna barst het festival uit zijn voegen in de verschillende zalen in DE Studio.

HERR SEELE, MARCEL VANTHILT en TEUN VERBRUGGEN & BONOM bereiden gepast dadaïstisch vuurwerk voor. Poëzierotten JAAP BLONK, PETER HOLVOET-HANSSEN en DIDI DE PARIS knipogen naar de historische dadapoëzie. Er is ook beeldende kunst met collage’s van BARBARA BERVOETS, spielereien van BERT LEZY en fluxus art van LUDO MICH. Tip Toe Topic, met o.a. ELKO BLIJWEERT, begeleiden oude experimentele dadafilmpjes. Danser MICHAEL VAN REMOORTERE toont zijn kont. Dichter ANDY FIERENS en muzikant MICHAËL BRIJS verzamelen een 30-koppig gelegenheidskoor onder de noemer De Bronstige Bazooka’s dat hun nieuwe dadawereldcreatie ‘World Reet Center’, waarin goede smaak wanhopig en helaas tevergeefs vecht voor zichzelf, in première zal zingen. De kunstenaars van Yellow Art uit Geel en het psychiatrisch centrum Sint-Amadeus uit Mortsel zorgen voor een 100-tal dadaïstisch beschilderde maskers die tijdens de Nacht van DADA worden uitgedeeld.

Al wat te serieus is in deze wereld zal er aan moeten geloven, dus doe uw beste boots aan en trek een zak over uw lelijke kop. Here we go. Let’s DADA!

De Nacht van DADA is een organisatie van VONK & Zonen i.s.m. Villanella en met steun van het Vlaams Fonds voor de Letteren en de stad Antwerpen.

De vorige Nacht van VONK is niet onopgemerkt voorbij gegleden. Meer dan vijftig schrijvers, muzikanten en kunstenaars brachten de geest van Jean-Marie Berckmans tot leven en doopten deze wilde nacht om tot de Nacht van PAFKE.

Dit jaar zet VONK & Zonen het festival in het teken van 100 jaar dada, de anarchistische, explosieve kunstbeweging die Europa in vuur en vlam zette kort na de eerste wereldoorlog. Verwacht u aan interventies van onze beste artiesten, van Herr Seele over Marcel Vanthilt tot Jaap Blonk. Als knallende openingsact hebben we Blixa Bargeld gestrikt voor een solo vocale performance in de geest van Kurt Schwitters. Al wat te serieus is in deze wereld, zal er aan moeten geloven.

DE Studio zal op zijn grondvesten daveren, dus doe uw beste boots aan en trek een zak over uw kop.

Here we go. Let’s dada!

DE VOLLEDIGE PROGRAMMATIE

EN TICKETS VIND JE OP

WWW.DESTUDIO.COM &

WWW.VONKENZONEN.BE

Met o.a.

HERR SEELE

JAAP BLONK

TEUN VERBRUGGEN

MARCEL VANTHILT

TIP TOE TOPIC

LUDO MICH

PETER HOLVOET-HANSSEN

BONOM

BARBARA BERVOETS

ANDREW CLAES

BERT LEZY

ANDY FIERENS

MICHAËL BRIJS

DE BRONSTIGE BAZOOKA’S

HERSENCELLEN

GERT VANLERBERGHE

ELKO BLIJWEERT

KUNSTHUIS YELLOW ART

DJ BOOTS

DIANE GRACE

TROEBEL NEYNTJE

KATJA STONEWOOD

VITALSKI

DJ WAGONMAN

SVEN DE SWERTS

MICHAEL VAN REMOORTERE

ANNELEEN VAN OFFEL

ELENA PEETERS

DOMINIQUE OSIER

DIDI DE PARIS

BUTSENZELLER

JEUGD & POËZIE

HAMSTER AXIS OF THE ONE CLICK PANTHER

PHILIP MEERSMAN

GEERT BEULLENS

MCHNRY

FREDERIK LUCIEN DE LAERE

ATERITIS BELDEMOR

DE Studio

Maarschalk Gérardstraat 4

2000 Antwerpen

# Meer info op website DE Studio

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #Archive A-Z Sound Poetry, Art & Literature News, Baargeld, Johannes Theodor, Ball, Hugo, Dada, DADA, Dadaïsme, Doesburg, Theo van, FLUXUS LEGACY, Kok, Antony, Literary Events, Ostaijen, Paul van, Schwitters, Kurt, THEATRE, Tzara, Tristan

Dafydd ap Gwilym

Dafydd ap Gwilym

Wales is een land van dichters, maar de beroemdste is nog steeds Dafydd ap Gwilym (circa 1315-1350). Zijn beheersing van de complexe metrische vormen van de traditionele Welse poëzie is fenomenaal, hij schreef over liefde, de natuur en mensen om hem heen en deed dat lyrisch, met menselijke warmte en een enkele keer ook vol weerzin en haat. Bovendien is Dafydd ap Gwilym belangrijk omdat hij als eerste op grote schaal en met ongekende vaardigheid nieuwe onderwerpen en thema’s die vanuit, vooral, de Franstalige poëzie in Wales doordrongen een volwaardige plaats wist te geven in de eigen traditie

In 1996 verscheen mijn tweetalige bloemlezing uit het werk van Dafydd ap Gwilym als een aflevering van het onvolprezen ‘literair kwartaalschrift’ Kruispunt. De bundel raakte snel uitverkocht, werd een antiquarische zeldzaamheid en leidde daardoor een min of meer ondergronds bestaan. Dat er waardering voor was, bleek uit de reacties die ik kreeg van lezers die de bundel wel in handen kregen en lazen. De wens om deze bloemlezing opnieuw toegankelijk te maken bestond dan ook al geruime tijd. Het vinden van een uitgever voor een herdruk leek daarbij geen optie. Dat was ook voor de eerste druk al erg lastig gebleken: het werk van een onbekende dichter in een onbekende taal is moeilijk te ‘vermarkten’, was vaak het argument.

Digitaal lag dan ook al snel voor de hand en nu is het zo ver. De oude tekstbestanden (in WordPerfect 5.1) werden opgeschoond en zodanig bewerkt dat nu in een pdf-bestand opnieuw in twee kolommen de vertalingen direct naast de oorspronkelijke gedichten staan. Bovendien zijn enkele (tik)fouten verbeterd en is op enkele punten de tekst (inleiding) en de vertaling aangepast. In die zin is hier dus sprake van een ‘tweede, herziene uitgave’. Wat ik niet heb gedaan, is geprobeerd de inleiding van de bloemlezing in zijn geheel up-to-date te maken. Enerzijds meen ik dat deze tekst nog steeds volwaardig op eigen benen kan staan en anderzijds biedt de geheel aan Dafydd ap Gwilym gewijde website www.dafyddapgwilym.net uitstekend toegang tot de recentere literatuur.

Graag dank ik op deze plaats ook de Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales voor de toestemming om gebruik te maken van de foto van Brogynin, de plaats waar Dafydd ap Gwilym werd geboren.

Lauran Toorians

# Voor de bloemlezing klik hier: toorians-dafydd_ap_gwilym

# Meer teksten en projekten van Lauran Toorians op website De Fakkel (Bijlichten en aansteken)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: CELTIC LITERATURE, Lauran Toorians, TRANSLATION ARCHIVE

The Tomb

The Tomb

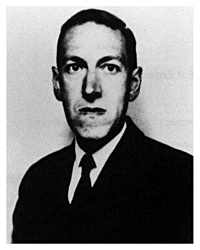

by H. P. Lovecraft

“Sedibus ut saltem placidis in morte quiescam.”

(Virgil)

In relating the circumstances which have led to my confinement within this refuge for the demented, I am aware that my present position will create a natural doubt of the authenticity of my narrative. It is an unfortunate fact that the bulk of humanity is too limited in its mental vision to weigh with patience and intelligence those isolated phenomena, seen and felt only by a psychologically sensitive few, which lie outside its common experience. Men of broader intellect know that there is no sharp distinction betwixt the real and the unreal; that all things appear as they do only by virtue of the delicate individual physical and mental media through which we are made conscious of them; but the prosaic materialism of the majority condemns as madness the flashes of super-sight which penetrate the common veil of obvious empiricism.

My name is Jervas Dudley, and from earliest childhood I have been a dreamer and a visionary. Wealthy beyond the necessity of a commercial life, and temperamentally unfitted for the formal studies and social recreations of my acquaintances, I have dwelt ever in realms apart from the visible world; spending my youth and adolescence in ancient and little-known books, and in roaming the fields and groves of the region near my ancestral home. I do not think that what I read in these books or saw in these fields and groves was exactly what other boys read and saw there; but of this I must say little, since detailed speech would but confirm those cruel slanders upon my intellect which I sometimes overhear from the whispers of the stealthy attendants around me. It is sufficient for me to relate events without analysing causes.

I have said that I dwelt apart from the visible world, but I have not said that I dwelt alone. This no human creature may do; for lacking the fellowship of the living, he inevitably draws upon the companionship of things that are not, or are no longer, living. Close by my home there lies a singular wooded hollow, in whose twilight deeps I spent most of my time; reading, thinking, and dreaming. Down its moss-covered slopes my first steps of infancy were taken, and around its grotesquely gnarled oak trees my first fancies of boyhood were woven. Well did I come to know the presiding dryads of those trees, and often have I watched their wild dances in the struggling beams of a waning moon—but of these things I must not now speak. I will tell only of the lone tomb in the darkest of the hillside thickets; the deserted tomb of the Hydes, an old and exalted family whose last direct descendant had been laid within its black recesses many decades before my birth.

The vault to which I refer is of ancient granite, weathered and discoloured by the mists and dampness of generations. Excavated back into the hillside, the structure is visible only at the entrance. The door, a ponderous and forbidding slab of stone, hangs upon rusted iron hinges, and is fastened ajar in a queerly sinister way by means of heavy iron chains and padlocks, according to a gruesome fashion of half a century ago. The abode of the race whose scions are here inurned had once crowned the declivity which holds the tomb, but had long since fallen victim to the flames which sprang up from a disastrous stroke of lightning. Of the midnight storm which destroyed this gloomy mansion, the older inhabitants of the region sometimes speak in hushed and uneasy voices; alluding to what they call “divine wrath” in a manner that in later years vaguely increased the always strong fascination which I felt for the forest-darkened sepulchre. One man only had perished in the fire. When the last of the Hydes was buried in this place of shade and stillness, the sad urnful of ashes had come from a distant land; to which the family had repaired when the mansion burned down. No one remains to lay flowers before the granite portal, and few care to brave the depressing shadows which seem to linger strangely about the water-worn stones.

I shall never forget the afternoon when first I stumbled upon the half-hidden house of death. It was in mid-summer, when the alchemy of Nature transmutes the sylvan landscape to one vivid and almost homogeneous mass of green; when the senses are well-nigh intoxicated with the surging seas of moist verdure and the subtly indefinable odours of the soil and the vegetation. In such surroundings the mind loses its perspective; time and space become trivial and unreal, and echoes of a forgotten prehistoric past beat insistently upon the enthralled consciousness. All day I had been wandering through the mystic groves of the hollow; thinking thoughts I need not discuss, and conversing with things I need not name. In years a child of ten, I had seen and heard many wonders unknown to the throng; and was oddly aged in certain respects. When, upon forcing my way between two savage clumps of briers, I suddenly encountered the entrance of the vault, I had no knowledge of what I had discovered. The dark blocks of granite, the door so curiously ajar, and the funereal carvings above the arch, aroused in me no associations of mournful or terrible character. Of graves and tombs I knew and imagined much, but had on account of my peculiar temperament been kept from all personal contact with churchyards and cemeteries. The strange stone house on the woodland slope was to me only a source of interest and speculation; and its cold, damp interior, into which I vainly peered through the aperture so tantalisingly left, contained for me no hint of death or decay. But in that instant of curiosity was born the madly unreasoning desire which has brought me to this hell of confinement. Spurred on by a voice which must have come from the hideous soul of the forest, I resolved to enter the beckoning gloom in spite of the ponderous chains which barred my passage. In the waning light of day I alternately rattled the rusty impediments with a view to throwing wide the stone door, and essayed to squeeze my slight form through the space already provided; but neither plan met with success. At first curious, I was now frantic; and when in the thickening twilight I returned to my home, I had sworn to the hundred gods of the grove that at any cost I would some day force an entrance to the black, chilly depths that seemed calling out to me. The physician with the iron-grey beard who comes each day to my room once told a visitor that this decision marked the beginning of a pitiful monomania; but I will leave final judgment to my readers when they shall have learnt all.

The months following my discovery were spent in futile attempts to force the complicated padlock of the slightly open vault, and in carefully guarded inquiries regarding the nature and history of the structure. With the traditionally receptive ears of the small boy, I learned much; though an habitual secretiveness caused me to tell no one of my information or my resolve. It is perhaps worth mentioning that I was not at all surprised or terrified on learning of the nature of the vault. My rather original ideas regarding life and death had caused me to associate the cold clay with the breathing body in a vague fashion; and I felt that the great and sinister family of the burned-down mansion was in some way represented within the stone space I sought to explore. Mumbled tales of the weird rites and godless revels of bygone years in the ancient hall gave to me a new and potent interest in the tomb, before whose door I would sit for hours at a time each day. Once I thrust a candle within the nearly closed entrance, but could see nothing save a flight of damp stone steps leading downward. The odour of the place repelled yet bewitched me. I felt I had known it before, in a past remote beyond all recollection; beyond even my tenancy of the body I now possess.

The year after I first beheld the tomb, I stumbled upon a worm-eaten translation of Plutarch’s Lives in the book-filled attic of my home. Reading the life of Theseus, I was much impressed by that passage telling of the great stone beneath which the boyish hero was to find his tokens of destiny whenever he should become old enough to lift its enormous weight. This legend had the effect of dispelling my keenest impatience to enter the vault, for it made me feel that the time was not yet ripe. Later, I told myself, I should grow to a strength and ingenuity which might enable me to unfasten the heavily chained door with ease; but until then I would do better by conforming to what seemed the will of Fate.

Accordingly my watches by the dank portal became less persistent, and much of my time was spent in other though equally strange pursuits. I would sometimes rise very quietly in the night, stealing out to walk in those churchyards and places of burial from which I had been kept by my parents. What I did there I may not say, for I am not now sure of the reality of certain things; but I know that on the day after such a nocturnal ramble I would often astonish those about me with my knowledge of topics almost forgotten for many generations. It was after a night like this that I shocked the community with a queer conceit about the burial of the rich and celebrated Squire Brewster, a maker of local history who was interred in 1711, and whose slate headstone, bearing a graven skull and crossbones, was slowly crumbling to powder. In a moment of childish imagination I vowed not only that the undertaker, Goodman Simpson, had stolen the silver-buckled shoes, silken hose, and satin small-clothes of the deceased before burial; but that the Squire himself, not fully inanimate, had turned twice in his mound-covered coffin on the day after interment.

But the idea of entering the tomb never left my thoughts; being indeed stimulated by the unexpected genealogical discovery that my own maternal ancestry possessed at least a slight link with the supposedly extinct family of the Hydes. Last of my paternal race, I was likewise the last of this older and more mysterious line. I began to feel that the tomb was mine, and to look forward with hot eagerness to the time when I might pass within that stone door and down those slimy stone steps in the dark. I now formed the habit of listening very intently at the slightly open portal, choosing my favourite hours of midnight stillness for the odd vigil. By the time I came of age, I had made a small clearing in the thicket before the mould-stained facade of the hillside, allowing the surrounding vegetation to encircle and overhang the space like the walls and roof of a sylvan bower. This bower was my temple, the fastened door my shrine, and here I would lie outstretched on the mossy ground, thinking strange thoughts and dreaming strange dreams.

The night of the first revelation was a sultry one. I must have fallen asleep from fatigue, for it was with a distinct sense of awakening that I heard the voices. Of those tones and accents I hesitate to speak; of their quality I will not speak; but I may say that they presented certain uncanny differences in vocabulary, pronunciation, and mode of utterance. Every shade of New England dialect, from the uncouth syllables of the Puritan colonists to the precise rhetoric of fifty years ago, seemed represented in that shadowy colloquy, though it was only later that I noticed the fact. At the time, indeed, my attention was distracted from this matter by another phenomenon; a phenomenon so fleeting that I could not take oath upon its reality. I barely fancied that as I awoke, a light had been hurriedly extinguished within the sunken sepulchre. I do not think I was either astounded or panic-stricken, but I know that I was greatly and permanently changed that night. Upon returning home I went with much directness to a rotting chest in the attic, wherein I found the key which next day unlocked with ease the barrier I had so long stormed in vain.

It was in the soft glow of late afternoon that I first entered the vault on the abandoned slope. A spell was upon me, and my heart leaped with an exultation I can but ill describe. As I closed the door behind me and descended the dripping steps by the light of my lone candle, I seemed to know the way; and though the candle sputtered with the stifling reek of the place, I felt singularly at home in the musty, charnel-house air. Looking about me, I beheld many marble slabs bearing coffins, or the remains of coffins. Some of these were sealed and intact, but others had nearly vanished, leaving the silver handles and plates isolated amidst certain curious heaps of whitish dust. Upon one plate I read the name of Sir Geoffrey Hyde, who had come from Sussex in 1640 and died here a few years later. In a conspicuous alcove was one fairly well-preserved and untenanted casket, adorned with a single name which brought to me both a smile and a shudder. An odd impulse caused me to climb upon the broad slab, extinguish my candle, and lie down within the vacant box.

In the grey light of dawn I staggered from the vault and locked the chain of the door behind me. I was no longer a young man, though but twenty-one winters had chilled my bodily frame. Early-rising villagers who observed my homeward progress looked at me strangely, and marvelled at the signs of ribald revelry which they saw in one whose life was known to be sober and solitary. I did not appear before my parents till after a long and refreshing sleep.

Henceforward I haunted the tomb each night; seeing, hearing, and doing things I must never reveal. My speech, always susceptible to environmental influences, was the first thing to succumb to the change; and my suddenly acquired archaism of diction was soon remarked upon. Later a queer boldness and recklessness came into my demeanour, till I unconsciously grew to possess the bearing of a man of the world despite my lifelong seclusion. My formerly silent tongue waxed voluble with the easy grace of a Chesterfield or the godless cynicism of a Rochester. I displayed a peculiar erudition utterly unlike the fantastic, monkish lore over which I had pored in youth; and covered the flyleaves of my books with facile impromptu epigrams which brought up suggestions of Gay, Prior, and the sprightliest of the Augustan wits and rimesters. One morning at breakfast I came close to disaster by declaiming in palpably liquorish accents an effusion of eighteenth-century Bacchanalian mirth; a bit of Georgian playfulness never recorded in a book, which ran something like this:

Come hither, my lads, with your tankards of ale,

And drink to the present before it shall fail;

Pile each on your platter a mountain of beef,

For ’tis eating and drinking that bring us relief:

So fill up your glass,

For life will soon pass;

When you’re dead ye’ll ne’er drink to your king or your lass!

Anacreon had a red nose, so they say;

But what’s a red nose if ye’re happy and gay?

Gad split me! I’d rather be red whilst I’m here,

Than white as a lily—and dead half a year!

So Betty, my miss,

Come give me a kiss;

In hell there’s no innkeeper’s daughter like this!

Young Harry, propp’d up just as straight as he’s able,

Will soon lose his wig and slip under the table;

But fill up your goblets and pass ’em around—

Better under the table than under the ground!

So revel and chaff

As ye thirstily quaff:

Under six feet of dirt ’tis less easy to laugh!

The fiend strike me blue! I’m scarce able to walk,

And damn me if I can stand upright or talk!

Here, landlord, bid Betty to summon a chair;

I’ll try home for a while, for my wife is not there!

So lend me a hand;

I’m not able to stand,

But I’m gay whilst I linger on top of the land!

About this time I conceived my present fear of fire and thunderstorms. Previously indifferent to such things, I had now an unspeakable horror of them; and would retire to the innermost recesses of the house whenever the heavens threatened an electrical display. A favourite haunt of mine during the day was the ruined cellar of the mansion that had burned down, and in fancy I would picture the structure as it had been in its prime. On one occasion I startled a villager by leading him confidently to a shallow sub-cellar, of whose existence I seemed to know in spite of the fact that it had been unseen and forgotten for many generations.

At last came that which I had long feared. My parents, alarmed at the altered manner and appearance of their only son, commenced to exert over my movements a kindly espionage which threatened to result in disaster. I had told no one of my visits to the tomb, having guarded my secret purpose with religious zeal since childhood; but now I was forced to exercise care in threading the mazes of the wooded hollow, that I might throw off a possible pursuer. My key to the vault I kept suspended from a cord about my neck, its presence known only to me. I never carried out of the sepulchre any of the things I came upon whilst within its walls.

One morning as I emerged from the damp tomb and fastened the chain of the portal with none too steady hand, I beheld in an adjacent thicket the dreaded face of a watcher. Surely the end was near; for my bower was discovered, and the objective of my nocturnal journeys revealed. The man did not accost me, so I hastened home in an effort to overhear what he might report to my careworn father. Were my sojourns beyond the chained door about to be proclaimed to the world? Imagine my delighted astonishment on hearing the spy inform my parent in a cautious whisper that I had spent the night in the bower outside the tomb; my sleep-filmed eyes fixed upon the crevice where the padlocked portal stood ajar! By what miracle had the watcher been thus deluded? I was now convinced that a supernatural agency protected me. Made bold by this heaven-sent circumstance, I began to resume perfect openness in going to the vault; confident that no one could witness my entrance. For a week I tasted to the full the joys of that charnel conviviality which I must not describe, when the thing happened, and I was borne away to this accursed abode of sorrow and monotony.

I should not have ventured out that night; for the taint of thunder was in the clouds, and a hellish phosphorescence rose from the rank swamp at the bottom of the hollow. The call of the dead, too, was different. Instead of the hillside tomb, it was the charred cellar on the crest of the slope whose presiding daemon beckoned to me with unseen fingers. As I emerged from an intervening grove upon the plain before the ruin, I beheld in the misty moonlight a thing I had always vaguely expected. The mansion, gone for a century, once more reared its stately height to the raptured vision; every window ablaze with the splendour of many candles. Up the long drive rolled the coaches of the Boston gentry, whilst on foot came a numerous assemblage of powdered exquisites from the neighbouring mansions. With this throng I mingled, though I knew I belonged with the hosts rather than with the guests. Inside the hall were music, laughter, and wine on every hand. Several faces I recognised; though I should have known them better had they been shrivelled or eaten away by death and decomposition. Amidst a wild and reckless throng I was the wildest and most abandoned. Gay blasphemy poured in torrents from my lips, and in my shocking sallies I heeded no law of God, Man, or Nature. Suddenly a peal of thunder, resonant even above the din of the swinish revelry, clave the very roof and laid a hush of fear upon the boisterous company. Red tongues of flame and searing gusts of heat engulfed the house; and the roysterers, struck with terror at the descent of a calamity which seemed to transcend the bounds of unguided Nature, fled shrieking into the night. I alone remained, riveted to my seat by a grovelling fear which I had never felt before. And then a second horror took possession of my soul. Burnt alive to ashes, my body dispersed by the four winds, I might never lie in the tomb of the Hydes! Was not my coffin prepared for me? Had I not a right to rest till eternity amongst the descendants of Sir Geoffrey Hyde? Aye! I would claim my heritage of death, even though my soul go seeking through the ages for another corporeal tenement to represent it on that vacant slab in the alcove of the vault. Jervas Hyde should never share the sad fate of Palinurus!

As the phantom of the burning house faded, I found myself screaming and struggling madly in the arms of two men, one of whom was the spy who had followed me to the tomb. Rain was pouring down in torrents, and upon the southern horizon were flashes of the lightning that had so lately passed over our heads. My father, his face lined with sorrow, stood by as I shouted my demands to be laid within the tomb; frequently admonishing my captors to treat me as gently as they could. A blackened circle on the floor of the ruined cellar told of a violent stroke from the heavens; and from this spot a group of curious villagers with lanterns were prying a small box of antique workmanship which the thunderbolt had brought to light. Ceasing my futile and now objectless writhing, I watched the spectators as they viewed the treasure-trove, and was permitted to share in their discoveries. The box, whose fastenings were broken by the stroke which had unearthed it, contained many papers and objects of value; but I had eyes for one thing alone. It was the porcelain miniature of a young man in a smartly curled bag-wig, and bore the initials “J. H.” The face was such that as I gazed, I might well have been studying my mirror.

On the following day I was brought to this room with the barred windows, but I have been kept informed of certain things through an aged and simple-minded servitor, for whom I bore a fondness in infancy, and who like me loves the churchyard. What I have dared relate of my experiences within the vault has brought me only pitying smiles. My father, who visits me frequently, declares that at no time did I pass the chained portal, and swears that the rusted padlock had not been touched for fifty years when he examined it. He even says that all the village knew of my journeys to the tomb, and that I was often watched as I slept in the bower outside the grim facade, my half-open eyes fixed on the crevice that leads to the interior. Against these assertions I have no tangible proof to offer, since my key to the padlock was lost in the struggle on that night of horrors. The strange things of the past which I learnt during those nocturnal meetings with the dead he dismisses as the fruits of my lifelong and omnivorous browsing amongst the ancient volumes of the family library. Had it not been for my old servant Hiram, I should have by this time become quite convinced of my madness.

But Hiram, loyal to the last, has held faith in me, and has done that which impels me to make public at least a part of my story. A week ago he burst open the lock which chains the door of the tomb perpetually ajar, and descended with a lantern into the murky depths. On a slab in an alcove he found an old but empty coffin whose tarnished plate bears the single word “Jervas”. In that coffin and in that vault they have promised me I shall be buried.

The Tomb (1917)

by H. P. Lovecraft (1890 – 1937)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Lovecraft, H.P., Tales of Mystery & Imagination

Leigh Hunt

(1784 – 1859)

On Receiving A Crown Of Ivy From John Keats

A Crown of of ivy! I submit my head

To the young hand that gives it, –young, ’tis true,

But with a right, for ’tis a poet’s too.

How pleasant the leaves feel! and how they spread

With their broad angles, like a nodding shed

Over both eyes! and how complete and new,

As on my hand I lean, to feel them strew

My sense with freshness, — Fancy’s rustling bed!

Tress-tossing girls, with smell of flowers and grapes

Come dancing by, and downward piping cheeks,

And up-thrown cymbals, and Silenus old

Lumpishly borne, and many trampling shapes,–

And lastly, with his bright eyes on her bent,

Bacchus, — whose bride has of his hand fast hold.

Leigh Hunt poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Archive K-L, Hunt, Leigh, Keats, John

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature