Fleurs du Mal Magazine

A l f o n s i n a S t o r n i

(1892-1938)

Parásitos

Jamás pensé que Dios tuviera alguna forma.

Absoluta su vida; y absoluta su norma.

Ojos no tuvo nunca: mira con las estrellas.

Manos no tuvo nunca: golpea con los mares.

Lengua no tuvo nunca: habla con los centellas.

Te diré, no te asombres;

Sé que tiene parásitos: las cosas y los hombres.

![]()

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Storni, Alfonsina

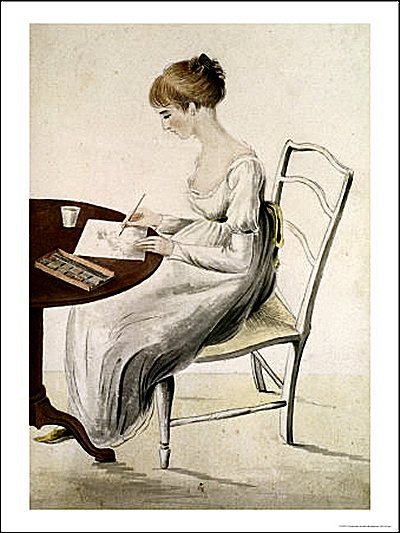

J a n e A u s t e n

(1775 – 1817)

Of A Ministry Pitiful, Angry, Mean

Of a Ministry pitiful, angry, mean,

A gallant commander the victim is seen.

For promptitude, vigour, success, does he stand

Condemn’d to receive a severe reprimand!

To his foes I could wish a resemblance in fate:

That they, too, may suffer themselves, soon or late,

The injustice they warrent. But vain is my spite

They cannot so suffer who never do right.

.jpg)

More in: Archive A-B, Austen, Jane, Austen, Jane

.jpg)

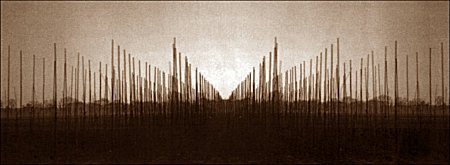

jef van kempen: 8 photos

fleursdumal.nl magazine

© fdm

m u s e u m o f l o s t c o n c e p t s

More in: Dutch Landscapes, Jef van Kempen, Jef van Kempen Photos & Drawings, Kempen, Jef van

.jpg)

J o h n K e a t s

(1795-1821)

T o A u t u m n

Season of mists and mellow fruitfulness,

Close bosom-friend of the maturing sun;

Conspiring with him how to load and bless

With fruit the vines that round the thatch-eves run;

To bend with apples the moss’d cottage-trees,

And fill all fruit with ripeness to the core;

To swell the gourd, and plump the hazel shells

With a sweet kernel; to set budding more,

And still more, later flowers for the bees,

Until they think warm days will never cease,

For Summer has o’er-brimm’d their clammy cells.

Who hath not seen thee oft amid thy store?

Sometimes whoever seeks abroad may find

Thee sitting careless on a granary floor,

Thy hair soft-lifted by the winnowing wind;

Or on a half-reap’d furrow sound asleep,

Drows’d with the fume of poppies, while thy hook

Spares the next swath and all its twined flowers:

And sometimes like a gleaner thou dost keep

Steady thy laden head across a brook;

Or by a cyder-press, with patient look,

Thou watchest the last oozings hours by hours.

Where are the songs of Spring? Ay, where are they?

Think not of them, thou hast thy music too,–

While barred clouds bloom the soft-dying day,

And touch the stubble-plains with rosy hue;

Then in a wailful choir the small gnats mourn

Among the river sallows, borne aloft

Or sinking as the light wind lives or dies;

And full-grown lambs loud bleat from hilly bourn;

Hedge-crickets sing; and now with treble soft

The red-breast whistles from a garden-croft;

And gathering swallows twitter in the skies.

Natuurdagboek Hans Hermans October 2009

Photos Hans Hermans – Poem: John Keats

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: 4SEASONS#Autumn, Hans Hermans Photos, John Keats, Keats, John

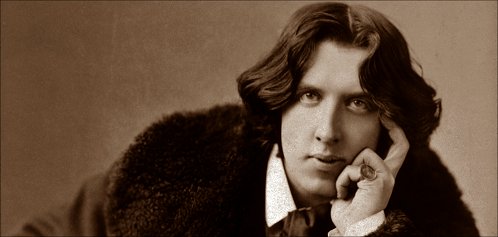

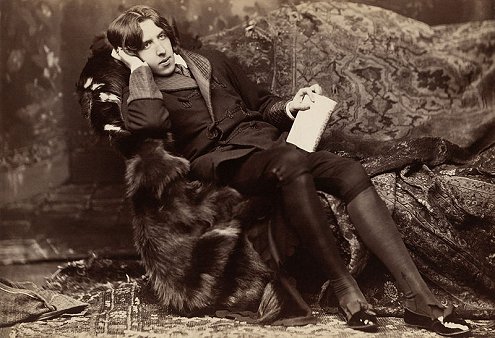

O s c a r W i l d e

(1854-1900)

The Ballad of Reading Gaol

He did not wear his scarlet coat,

For blood and wine are red,

And blood and wine were on his hands

When they found him with the dead,

The poor dead woman whom he loved,

And murdered in her bed.

He walked amongst the Trial Men

In a suit of shabby gray;

A cricket cap was on his head,

And his step seemed light and gay;

But I never saw a man who looked

So wistfully at the day.

I never saw a man who looked

With such a wistful eye

Upon that little tent of blue

Which prisoners call the sky,

And at every drifting cloud that went

With sails of silver by.

I walked, with other souls in pain,

Within another ring,

And was wondering if the man had done

A great or little thing,

When a voice behind me whispered low,

"That fellow’s got to swing."

Dear Christ! the very prison walls

Suddenly seemed to reel,

And the sky above my head became

Like a casque of scorching steel;

And, though I was a soul in pain,

My pain I could not feel.

I only knew what haunted thought

Quickened his step, and why

He looked upon the garish day

With such a wistful eye;

The man had killed the thing he loved,

And so he had to die.

Yet each man kills the thing he loves,

By each let this be heard,

Some do it with a bitter look,

Some with a flattering word,

The coward does it with a kiss,

The brave man with a sword!

Some kill their love when they are young,

And some when they are old;

Some strangle with the hands of Lust,

Some with the hands of Gold:

The kindest use a knife, because

The dead so soon grow cold.

Some love too little, some too long,

Some sell, and others buy;

Some do the deed with many tears,

And some without a sigh:

For each man kills the thing he loves,

Yet each man does not die.

He does not die a death of shame

On a day of dark disgrace,

Nor have a noose about his neck,

Nor a cloth upon his face,

Nor drop feet foremost through the floor

Into an empty space.

He does not sit with silent men

Who watch him night and day;

Who watch him when he tries to weep,

And when he tries to pray;

Who watch him lest himself should rob

The prison of its prey.

He does not wake at dawn to see

Dread figures throng his room,

The shivering Chaplain robed in white,

The Sheriff stern with gloom,

And the Governor all in shiny black,

With the yellow face of Doom.

He does not rise in piteous haste

To put on convict-clothes,

While some coarse-mouthed Doctor gloats, and notes

Each new and nerve-twitched pose,

Fingering a watch whose little ticks

Are like horrible hammer-blows.

He does not feel that sickening thirst

That sands one’s throat, before

The hangman with his gardener’s gloves

Comes through the padded door,

And binds one with three leathern thongs,

That the throat may thirst no more.

He does not bend his head to hear

The Burial Office read,

Nor, while the anguish of his soul

Tells him he is not dead,

Cross his own coffin, as he moves

Into the hideous shed.

He does not stare upon the air

Through a little roof of glass:

He does not pray with lips of clay

For his agony to pass;

Nor feel upon his shuddering cheek

The kiss of Caiaphas.

II

Six weeks the guardsman walked the yard,

In the suit of shabby gray:

His cricket cap was on his head,

And his step was light and gay,

But I never saw a man who looked

So wistfully at the day.

I never saw a man who looked

With such a wistful eye

Upon that little tent of blue

Which prisoners call the sky,

And at every wandering cloud that trailed

Its ravelled fleeces by.

He did not wring his hands, as do

Those witless men who dare

To try to rear the changeling Hope

In the cave of black Despair:

He only looked upon the sun,

And drank the morning air.

He did not wring his hands nor weep,

Nor did he peek or pine,

But he drank the air as though it held

Some healthful anodyne;

With open mouth he drank the sun

As though it had been wine!

And I and all the souls in pain,

Who tramped the other ring,

Forgot if we ourselves had done

A great or little thing,

And watched with gaze of dull amaze

The man who had to swing.

For strange it was to see him pass

With a step so light and gay,

And strange it was to see him look

So wistfully at the day,

And strange it was to think that he

Had such a debt to pay.

The oak and elm have pleasant leaves

That in the spring-time shoot:

But grim to see is the gallows-tree,

With its alder-bitten root,

And, green or dry, a man must die

Before it bears its fruit!

The loftiest place is the seat of grace

For which all worldlings try:

But who would stand in hempen band

Upon a scaffold high,

And through a murderer’s collar take

His last look at the sky?

It is sweet to dance to violins

When Love and Life are fair:

To dance to flutes, to dance to lutes

Is delicate and rare:

But it is not sweet with nimble feet

To dance upon the air!

So with curious eyes and sick surmise

We watched him day by day,

And wondered if each one of us

Would end the self-same way,

For none can tell to what red Hell

His sightless soul may stray.

At last the dead man walked no more

Amongst the Trial Men,

And I knew that he was standing up

In the black dock’s dreadful pen,

And that never would I see his face

For weal or woe again.

Like two doomed ships that pass in storm

We had crossed each other’s way:

But we made no sign, we said no word,

We had no word to say;

For we did not meet in the holy night,

But in the shameful day.

A prison wall was round us both,

Two outcast men we were:

The world had thrust us from its heart,

And God from out His care:

And the iron gin that waits for Sin

Had caught us in its snare.

III

In Debtors’ Yard the stones are hard,

And the dripping wall is high,

So it was there he took the air

Beneath the leaden sky,

And by each side a warder walked,

For fear the man might die.

Or else he sat with those who watched

His anguish night and day;

Who watched him when he rose to weep,

And when he crouched to pray;

Who watched him lest himself should rob

Their scaffold of its prey.

The Governor was strong upon

The Regulations Act:

The Doctor said that Death was but

A scientific fact:

And twice a day the Chaplain called,

And left a little tract.

And twice a day he smoked his pipe,

And drank his quart of beer:

His soul was resolute, and held

No hiding-place for fear;

He often said that he was glad

The hangman’s day was near.

But why he said so strange a thing

No warder dared to ask:

For he to whom a watcher’s doom

Is given as his task,

Must set a lock upon his lips,

And make his face a mask.

Or else he might be moved, and try

To comfort or console:

And what should Human Pity do

Pent up in Murderers’ Hole?

What word of grace in such a place

Could help a brother’s soul?

With slouch and swing around the ring

We trod the Fools’ Parade!

We did not care: we knew we were

The Devils’ Own Brigade:

And shaven head and feet of lead

Make a merry masquerade.

We tore the tarry rope to shreds

With blunt and bleeding nails;

We rubbed the doors, and scrubbed the floors,

And cleaned the shining rails:

And, rank by rank, we soaped the plank,

And clattered with the pails.

We sewed the sacks, we broke the stones,

We turned the dusty drill:

We banged the tins, and bawled the hymns,

And sweated on the mill:

But in the heart of every man

Terror was lying still.

So still it lay that every day

Crawled like a weed-clogged wave:

And we forgot the bitter lot

That waits for fool and knave,

Till once, as we tramped in from work,

We passed an open grave.

With yawning mouth the horrid hole

Gaped for a living thing;

The very mud cried out for blood

To the thirsty asphalte ring:

And we knew that ere one dawn grew fair

The fellow had to swing.

Right in we went, with soul intent

On Death and Dread and Doom:

The hangman, with his little bag,

Went shuffling through the gloom:

And I trembled as I groped my way

Into my numbered tomb.

That night the empty corridors

Were full of forms of Fear,

And up and down the iron town

Stole feet we could not hear,

And through the bars that hide the stars

White faces seemed to peer.

He lay as one who lies and dreams

In a pleasant meadow-land,

The watchers watched him as he slept,

And could not understand

How one could sleep so sweet a sleep

With a hangman close at hand.

But there is no sleep when men must weep

Who never yet have wept:

So we- the fool, the fraud, the knave-

That endless vigil kept,

And through each brain on hands of pain

Another’s terror crept.

Alas! it is a fearful thing

To feel another’s guilt!

For, right within, the sword of Sin

Pierced to its poisoned hilt,

And as molten lead were the tears we shed

For the blood we had not spilt.

The warders with their shoes of felt

Crept by each padlocked door,

And peeped and saw, with eyes of awe,

Gray figures on the floor,

And wondered why men knelt to pray

Who never prayed before.

All through the night we knelt and prayed,

Mad mourners of a corse!

The troubled plumes of midnight shook

Like the plumes upon a hearse:

And as bitter wine upon a sponge

Was the savour of Remorse.

The gray cock crew, the red cock crew,

But never came the day:

And crooked shapes of Terror crouched,

In the corners where we lay:

And each evil sprite that walks by night

Before us seemed to play.

They glided past, the glided fast,

Like travellers through a mist:

They mocked the moon in a rigadoon

Of delicate turn and twist,

And with formal pace and loathsome grace

The phantoms kept their tryst.

With mop and mow, we saw them go,

Slim shadows hand in hand:

About, about, in ghostly rout

They trod a saraband:

And the damned grotesques made arabesques,

Like the wind upon the sand!

With the pirouettes of marionettes,

They tripped on pointed tread:

But with flutes of Fear they filled the ear,

As their grisly masque they led,

And loud they sang, and long they sang,

For they sang to wake the dead.

"Oho!" they cried, "the world is wide,

But fettered limbs go lame!

And once, or twice, to throw the dice

Is a gentlemanly game,

But he does not win who plays with Sin

In the secret House of Shame."

No things of air these antics were,

That frolicked with such glee:

To men whose lives were held in gyves,

And whose feet might not go free,

Ah! wounds of Christ! they were living things,

Most terrible to see.

Around, around, they waltzed and wound;

Some wheeled in smirking pairs;

With the mincing step of a demirep

Some sidled up the stairs:

And with subtle sneer, and fawning leer,

Each helped us at our prayers.

The morning wind began to moan,

But still the night went on:

Through its giant loom the web of gloom

Crept till each thread was spun:

And, as we prayed, we grew afraid

Of the Justice of the Sun.

The moaning wind went wandering round

The weeping prison wall:

Till like a wheel of turning steel

We felt the minutes crawl:

O moaning wind! what had we done

To have such a seneschal?

At last I saw the shadowed bars,

Like a lattice wrought in lead,

Move right across the whitewashed wall

That faced my three-plank bed,

And I knew that somewhere in the world

God’s dreadful dawn was red.

At six o’clock we cleaned our cells,

At seven all was still,

But the sough and swing of a mighty wing

The prison seemed to fill,

For the Lord of Death with icy breath

Had entered in to kill.

He did not pass in purple pomp,

Nor ride a moon-white steed.

Three yards of cord and a sliding board

Are all the gallows’ need:

So with rope of shame the Herald came

To do the secret deed.

We were as men who through a fen

Of filthy darkness grope:

We did not dare to breathe a prayer,

Or to give our anguish scope:

Something was dead in each of us,

And what was dead was Hope.

For Man’s grim Justice goes its way

And will not swerve aside:

It slays the weak, it slays the strong,

It has a deadly stride:

With iron heel it slays the strong

The monstrous parricide!

We waited for the stroke of eight:

Each tongue was thick with thirst:

For the stroke of eight is the stroke of Fate

That makes a man accursed,

And Fate will use a running noose

For the best man and the worst.

We had no other thing to do,

Save to wait for the sign to come:

So, like things of stone in a valley lone,

Quiet we sat and dumb:

But each man’s heart beat thick and quick,

Like a madman on a drum!

With sudden shock the prison-clock

Smote on the shivering air,

And from all the gaol rose up a wail

Of impotent despair,

Like the sound the frightened marshes hear

From some leper in his lair.

And as one sees most fearful things

In the crystal of a dream,

We saw the greasy hempen rope

Hooked to the blackened beam,

And heard the prayer the hangman’s snare

Strangled into a scream.

And all the woe that moved him so

That he gave that bitter cry,

And the wild regrets, and the bloody sweats,

None knew so well as I:

For he who lives more lives than one

More deaths that one must die.

IV

There is no chapel on the day

On which they hang a man:

The Chaplain’s heart is far too sick,

Or his face is far too wan,

Or there is that written in his eyes

Which none should look upon.

So they kept us close till nigh on noon,

And then they rang the bell,

And the warders with their jingling keys

Opened each listening cell,

And down the iron stair we tramped,

Each from his separate Hell.

Out into God’s sweet air we went,

But not in wonted way,

For this man’s face was white with fear,

And that man’s face was gray,

And I never saw sad men who looked

So wistfully at the day.

I never saw sad men who looked

With such a wistful eye

Upon that little tent of blue

We prisoners called the sky,

And at every happy cloud that passed

In such strange freedom by.

But there were those amongst us all

Who walked with downcast head,

And knew that, had each got his due,

They should have died instead:

He had but killed a thing that lived,

Whilst they had killed the dead.

For he who sins a second time

Wakes a dead soul to pain,

And draws it from its spotted shroud

And makes it bleed again,

And makes it bleed great gouts of blood,

And makes it bleed in vain!

Like ape or clown, in monstrous garb

With crooked arrows starred,

Silently we went round and round

The slippery asphalte yard;

Silently we went round and round,

And no man spoke a word.

Silently we went round and round,

And through each hollow mind

The Memory of dreadful things

Rushed like a dreadful wind,

And Horror stalked before each man,

And Terror crept behind.

The warders strutted up and down,

And watched their herd of brutes,

Their uniforms were spick and span,

And they wore their Sunday suits,

But we knew the work they had been at,

By the quicklime on their boots.

For where a grave had opened wide,

There was no grave at all:

Only a stretch of mud and sand

By the hideous prison-wall,

And a little heap of burning lime,

That the man should have his pall.

For he has a pall, this wretched man,

Such as few men can claim:

Deep down below a prison-yard,

Naked, for greater shame,

He lies, with fetters on each foot,

Wrapt in a sheet of flame!

And all the while the burning lime

Eats flesh and bone away,

It eats the brittle bones by night,

And the soft flesh by day,

It eats the flesh and bone by turns,

But it eats the heart alway.

For three long years they will not sow

Or root or seedling there:

For three long years the unblessed spot

Will sterile be and bare,

And look upon the wondering sky

With unreproachful stare.

They think a murderer’s heart would taint

Each simple seed they sow.

It is not true! God’s kindly earth

Is kindlier than men know,

And the red rose would but glow more red,

The white rose whiter blow.

Out of his mouth a red, red rose!

Out of his heart a white!

For who can say by what strange way,

Christ brings His will to light,

Since the barren staff the pilgrim bore

Bloomed in the great Pope’s sight?

But neither milk-white rose nor red

May bloom in prison air;

The shard, the pebble, and the flint,

Are what they give us there:

For flowers have been known to heal

A common man’s despair.

So never will wine-red rose or white,

Petal by petal, fall

On that stretch of mud and sand that lies

By the hideous prison-wall,

To tell the men who tramp the yard

That God’s Son died for all.

Yet though the hideous prison-wall

Still hems him round and round,

And a spirit may not walk by night

That is with fetters bound,

And a spirit may but weep that lies

In such unholy ground,

He is at peace- this wretched man-

At peace, or will be soon:

There is no thing to make him mad,

Nor does Terror walk at noon,

For the lampless Earth in which he lies

Has neither Sun nor Moon.

They hanged him as a beast is hanged:

They did not even toll

A requiem that might have brought

Rest to his startled soul,

But hurriedly they took him out,

And hid him in a hole.

The warders stripped him of his clothes,

And gave him to the flies:

They mocked the swollen purple throat,

And the stark and staring eyes:

And with laughter loud they heaped the shroud

In which the convict lies.

The Chaplain would not kneel to pray

By his dishonoured grave:

Nor mark it with that blessed Cross

That Christ for sinners gave,

Because the man was one of those

Whom Christ came down to save.

Yet all is well; he has but passed

To Life’s appointed bourne:

And alien tears will fill for him

Pity’s long-broken urn,

For his mourners be outcast men,

And outcasts always mourn.

V

I know not whether Laws be right,

Or whether Laws be wrong;

All that we know who lie in gaol

Is that the wall is strong;

And that each day is like a year,

A year whose days are long.

But this I know, that every Law

That men have made for Man,

Since first Man took His brother’s life,

And the sad world began,

But straws the wheat and saves the chaff

With a most evil fan.

This too I know- and wise it were

If each could know the same-

That every prison that men build

Is built with bricks of shame,

And bound with bars lest Christ should see

How men their brothers maim.

With bars they blur the gracious moon,

And blind the goodly sun:

And the do well to hide their Hell,

For in it things are done

That Son of things nor son of Man

Ever should look upon!

The vilest deeds like poison weeds

Bloom well in prison-air:

It is only what is good in Man

That wastes and withers there:

Pale Anguish keeps the heavy gate,

And the warder is Despair.

For they starve the little frightened child

Till it weeps both night and day:

And they scourge the weak, and flog the fool,

And gibe the old and gray,

And some grow mad, and all grow bad,

And none a word may say.

Each narrow cell in which we dwell

Is a foul and dark latrine,

And the fetid breath of living Death

Chokes up each grated screen,

And all, but Lust, is turned to dust

In Humanity’s machine.

The brackish water that we drink

Creeps with a loathsome slime,

And the bitter bread they weigh in scales

Is full of chalk and lime,

And Sleep will not lie down, but walks

Wild-eyed, and cries to Time.

But though lean Hunger and green Thirst

Like asp with adder fight,

We have little care of prison fare,

For what chills and kills outright

Is that every stone one lifts by day

Becomes one’s heart by night.

With midnight always in one’s heart,

And twilight in one’s cell,

We turn the crank, or tear the rope,

Each in his separate Hell,

And the silence is more awful far

Than the sound of a brazen bell.

And never a human voice comes near

To speak a gentle word:

And the eye that watches through the door

Is pitiless and hard:

And by all forgot, we rot and rot,

With soul and body marred.

And thus we rust Life’s iron chain

Degraded and alone:

And some men curse, and some men weep,

And some men make no moan:

But God’s eternal Laws are kind

And break the heart of stone.

And every human heart that breaks,

In prison-cell or yard,

Is as that broken box that gave

Its treasure to the Lord,

And filled the unclean leper’s house

With the scent of costliest nard.

Ah! happy they whose hearts can break

And peace of pardon win!

How else may man make straight his plan

And cleanse his soul from Sin?

How else but through a broken heart

May Lord Christ enter in?

And he of the swollen purple throat,

And the stark and staring eyes,

Waits for the holy hands that took

The Thief to Paradise;

And a broken and a contrite heart

The Lord will not despise.

The man in red who reads the Law

Gave him three weeks of life,

Three little weeks in which to heal

His soul of his soul’s strife,

And cleanse from every blot of blood

The hand that held the knife.

And with tears of blood he cleansed the hand,

The hand that held the steel:

For only blood can wipe out blood,

And only tears can heal:

And the crimson stain that was of Cain

Became Christ’s snow-white seal.

VI

In Reading gaol by Reading town

There is a pit of shame,

And in it lies a wretched man

Eaten by teeth of flame,

In a burning winding-sheet he lies,

And his grave has got no name.

And there, till Christ call forth the dead,

In silence let him lie:

No need to waste the foolish tear,

Or heave the windy sigh:

The man had killed the thing he loved,

And so he had to die.

And all men kill the thing they love,

By all let this be heard,

Some do it with a bitter look,

Some with a flattering word,

The coward does it with a kiss,

The brave man with a sword!

THE END

O s c a r W i l d e p o e t r y

k e m p i s p o e t r y m a g a z i n e

More in: Wilde, Oscar

.jpg)

W i l l i a m S h a k e s p e a r e

(1564-1616)

T H E S O N N E T S

2

When forty winters shall besiege thy brow,

And dig deep trenches in thy beauty’s field,

Thy youth’s proud livery so gazed on now,

Will be a tattered weed of small worth held:

Then being asked, where all thy beauty lies,

Where all the treasure of thy lusty days;

To say within thine own deep sunken eyes,

Were an all-eating shame, and thriftless praise.

How much more praise deserved thy beauty’s use,

If thou couldst answer ‘This fair child of mine

Shall sum my count, and make my old excuse’

Proving his beauty by succession thine.

This were to be new made when thou art old,

And see thy blood warm when thou feel’st it cold.

![]()

k e m p i s p o e t r y m a g a z i n e

More in: -Shakespeare Sonnets

L I L A L I T E R A I R

6 november 2009

Rashid Novaire, Driek van Wissen,

Jean Pierre Rawie en Ton van Reen

Toptalent in overvloed tijdens Lila Literair

Rashid Novaire, Driek van Wissen, Jean Pierre Rawie en Ton van Reen. Ter afsluiting van de luisterrijke literaire avond volgt een boekenfeest met muziek van Gino en Jiri Taihuttu, de folkgroep Parelmoer en Bert van den Bergh.

Limburg is klaar voor een nieuw literair evenement dat gaat plaatsvinden op 6 november om 20.00 uur ’t Raodhoes in Blerick. De Stichting Lalibela, BlariaCultura en Cultureel Centrum ’t Raodhoes in Blerick hebben de handen ineengeslagen om het literatuur- en cultuurminnende publiek een onvergetelijke avond te bezorgen.

Maar liefst vier topauteurs laten het achterste van hun tong zien. Ze vertellen over hun eigen werk en gaan met elkaar in gesprek over hun visie op literatuur.

In de eerste sessie kruisen Ton van Reen en Rashid Novaire de degens. Van Reen werd in 2007 door het Limburgs Dagblad en L1 uitverkozen tot de grootste Limburgse schrijver aller tijden. Hij is dé chroniqueur van het rijke Roomse leven, maar zijn maatschappelijke betrokkenheid reikt veel verder dan de grenzen van zijn eigen streek. De jonge Rashid Novaire timmert al tien jaar aan de weg met grenzeloze verhalen en een tomeloze verbeeldingskracht. Afgelopen zomer werd hij gekozen tot president van de Zomerparkfeesten in Venlo.

Na de pauze zorgen de twee markantste dichters van Nederland voor verbaal vuurwerk. Voormalig Dichter des Vaderlands Driek van Wissen vertelt over zijn werk met de ernst van een vakman en tegelijkertijd de innemende humor en relativeringszin van een artiest. Rawie is niet alleen vanwege zijn flamboyante uitstraling een icoon, ook zijn werk spreekt bij een breed publiek tot de verbeelding. Op milde, ironische toon bezingt hij op geheel eigen wijze de klassieke thema’s. Rawie en Van Wissen debuteerden in 1976 samen en raakten sindsdien steeds beter op elkaar ingespeeld. Zij maken er op 6 november zonder twijfel een boeiend spektakel van.

Na de voordrachten en discussies van de auteurs kunt u nader kennismaken met de auteurs en hun werk op de boekenmarkt. Daar staat ook een boekenkraam van Boeken Steunen Mensen en een informatiestand van Stichting Lalibela.

Om 22.30 uur nemen diverse topartiesten het roer over om er een spetterend muzikaal feest van te maken. Gino en Jiri Taihuttu, de folkgroep Parelmoer en Bert van den Bergh zorgen voor een mooie ambiance.

Voor € 12,50 bent u getuige van een uniek spektakel in Limburg én levert u een bijdrage aan de projecten van de door Ton van Reen opgerichte Stichting Lalibela. De stichting zet zich in voor de armsten van de armsten in het Ethiopische stadje Lalibela en probeert hen op weg te helpen naar een zelfstandige toekomst. Zie voor meer informatie www.stichtinglalibela.nl.

Alle auteurs en artiesten treden belangeloos op, zodat de opbrengst van de kaartverkoop ten goede komt aan het goede doel.

Kaarten zijn te verkrijgen bij ´t Raodhoes in Blerick, Boekhandel Koops in Venlo en via lilaliterair.stichtinglalibela.nl.

![]()

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Art & Literature News, Reen, Ton van

.jpg)

R a i n e r M a r i a R i l k e

(1875-1926)

R e q u i e m

Für eine Freundin

Ich habe Tote, und ich ließ sie hin

und war erstaunt, sie so getrost zu sehn,

so rasch zuhaus im Totsein, so gerecht,

so anders als ihr Ruf. Nur du, du kehrst

zurück; du streifst mich, du gehst um, du willst

an etwas stoßen, daß es klingt von dir

und dich verrät. O nimm mir nicht, was ich

langsam erlern. Ich habe recht; du irrst

wenn du gerührt zu irgend einem Ding

ein Heimweh hast. Wir wandeln dieses um;

es ist nicht hier, wir spiegeln es herein

aus unserm Sein, sobald wir es erkennen.

Ich glaubte dich viel weiter. Mich verwirrts,

daß du gerade irrst und kommst, die mehr

verwandelt hat als irgend eine Frau.

Daß wir erschraken, da du starbst, nein, daß

dein starker Tod uns dunkel unterbrach,

das Bisdahin abreißend vom Seither:

das geht uns an; das einzuordnen wird

die Arbeit sein, die wir mit allem tun.

Doch daß du selbst erschrakst und auch noch jetzt

den Schrecken hast, wo Schrecken nicht mehr gilt;

daß du von deiner Ewigkeit ein Stück

verlierst und hier hereintrittst, Freundin, hier,

wo alles noch nicht ist; daß du zerstreut,

zum ersten Mal im All zerstreut und halb,

den Aufgang der unendlichen Naturen

nicht so ergriffst wie hier ein jedes Ding;

daß aus dem Kreislauf, der dich schon empfing,

die stumme Schwerkraft irgend einer Unruh

dich niederzieht zur abgezählten Zeit – :

dies weckt mich nachts oft wie ein Dieb, der einbricht.

Und dürft ich sagen, daß du nur geruhst,

daß du aus Großmut kommst, aus Überfülle,

weil du so sicher bist, so in dir selbst,

daß du herumgehst wie ein Kind, nicht bange

vor Örtern, wo man einem etwas tut – :

doch nein: du bittest. Dieses geht mir so

bis ins Gebein und querrt wie eine Säge.

Ein Vorwurf, den du trügest als Gespenst,

nachtrügest mir, wenn ich mich nachts zurückzieh

in meine Lunge, in die Eingeweide,

in meines Herzens letzte ärmste Kammer,

ein solcher Vorwurf wäre nicht so grausam,

wie dieses Bitten ist. Was bittest du?

Sag, soll ich reisen? Hast du irgendwo

ein Ding zurückgelassen, das sich quält

und das dir nachwill? Soll ich in ein Land,

das du nicht sahst, obwohl es dir verwandt

war wie die andre Hälfte deiner Sinne?

Ich will auf seinen Flüssen fahren, will

an Land gehn und nach alten Sitten fragen,

will mit den Frauen in den Türen sprechen

und zusehn, wenn sie ihre Kinder rufen.

Ich will mir merken, wie sie dort die Landschaft

umnehmen draußen bei der alten Arbeit

der Wiesen und der Felder; will begehren,

vor ihren König hingeführt zu sein,

und will die Priester durch Bestechung reizen,

daß sie mich legen vor das stärkste Standbild

und fortgehn und die Tempeltore schließen.

Dann aber will ich, wenn ich vieles weiß,

einfach die Tiere anschaun, daß ein Etwas

von ihrer Wendung mir in die Gelenke

herübergleitet; will ein kurzes Dasein

in ihren Augen haben, die mich halten

und langsam lassen, ruhig, ohne Urteil.

Ich will mir von den Gärtnern viele Blumen

hersagen lassen, daß ich in den Scherben

der schönen Eigennamen einen Rest

herüberbringe von den hundert Düften.

Und Früchte will ich kaufen, Früchte, drin

das Land noch einmal ist, bis an den Himmel.

Denn Das verstandest du: die vollen Früchte.

Die legtest du auf Schalen vor dich hin

und wogst mit Farben ihre Schwere auf.

Und so wie Früchte sahst du auch die Fraun

und sahst die Kinder so, von innen her

getrieben in die Formen ihres Daseins.

Und sahst dich selbst zuletzt wie eine Frucht,

nahmst dich heraus aus deinen Kleidern, trugst

dich vor den Spiegel, ließest dich hinein

bis auf dein Schauen; das blieb groß davor

und sagte nicht: das bin ich; nein: dies ist.

So ohne Neugier war zuletzt dein Schaun

und so besitzlos, von so wahrer Armut,

daß es dich selbst nicht mehr begehrte: heilig.

So will ich dich behalten, wie du dich

hinstelltest in den Spiegel, tief hinein

und fort von allem. Warum kommst du anders?

Was widerrufst du dich? Was willst du mir

einreden, daß in jenen Bernsteinkugeln

um deinen Hals noch etwas Schwere war

von jener Schwere, wie sie nie im Jenseits

beruhigter Bilder ist; was zeigst du mir

in deiner Haltung eine böse Ahnung;

was heißt dich die Konturen deines Leibes

auslegen wie die Linien einer Hand,

daß ich sie nicht mehr sehn kann ohne Schicksal?

Komm her ins Kerzenlicht. Ich bin nicht bang,

die Toten anzuschauen. Wenn sie kommen,

so haben sie ein Recht, in unserm Blick

sich aufzuhalten, wie die andern Dinge.

Komm her; wir wollen eine Weile still sein.

Sieh diese Rose an auf meinem Schreibtisch;

ist nicht das Licht um sie genau so zaghaft

wie über dir: sie dürfte auch nicht hier sein.

Im Garten draußen, unvermischt mit mir,

hätte sie bleiben müssen oder hingehn, –

nun währt sie so: was ist ihr mein Bewußtsein?

Erschrick nicht, wenn ich jetzt begreife, ach,

da steigt es in mir auf: ich kann nicht anders,

ich muß begreifen, und wenn ich dran stürbe.

Begreifen, daß du hier bist. Ich begreife.

Ganz wie ein Blinder rings ein Ding begreift,

fühl ich dein Los und weiß ihm keinen Namen.

Laß uns zusammen klagen, daß dich einer

aus deinem Spiegel nahm. Kannst du noch weinen?

Du kannst nicht. Deiner Tränen Kraft und Andrang

hast du verwandelt in dein reifes Anschaun

und warst dabei, jeglichen Saft in dir

so umzusetzen in ein starkes Dasein,

das steigt und kreist im Gleichgewicht und blindlings.

Da riß ein Zufall dich, dein letzter Zufall

riß dich zurück aus deinem fernsten Fortschritt

in eine Welt zurück, wo Säfte wollen.

Riß dich nicht ganz; riß nur ein Stück zuerst,

doch als um dieses Stück von Tag zu Tag

die Wirklichkeit so zunahm, daß es schwer ward,

da brauchtest du dich ganz: da gingst du hin

und brachst in Brocken dich aus dem Gesetz

mühsam heraus, weil du dich brauchtest. Da

trugst du dich ab und grubst aus deines Herzens

nachtwarmem Erdreich die noch grünen Samen,

daraus dein Tod aufkeimen sollte: deiner,

dein eigner Tod zu deinem eignen Leben.

Und aßest sie, die Körner deines Todes,

wie alle andern, aßest seine Körner,

und hattest Nachgeschmack in dir von Süße,

die du nicht meintest, hattest süße Lippen,

du: die schon innen in den Sinnen süß war.

O laß uns klagen. Weißt du, wie dein Blut

aus einem Kreisen ohnegleichen zögernd

und ungern wiederkam, da du es abriefst?

Wie es verwirrt des Leibes kleinen Kreislauf

noch einmal aufnahm; wie es voller Mißtraun

und Staunen eintrat in den Mutterkuchen

und von dem weiten Rückweg plötzlich müd war.

Du triebst es an, du stießest es nach vorn,

du zerrtest es zur Feuerstelle, wie

man eine Herde Tiere zerrt zum Opfer;

und wolltest noch, es sollte dabei froh sein.

Und du erzwangst es schließlich: es war froh

und lief herbei und gab sich hin. Dir schien,

weil du gewohnt warst an die andern Maße,

es wäre nur für eine Weile; aber

nun warst du in der Zeit, und Zeit ist lang.

Und Zeit geht hin, und Zeit nimmt zu, und Zeit

ist wie ein Rückfall einer langen Krankheit.

Wie war dein Leben kurz, wenn du’s vergleichst

mit jenen Stunden, da du saßest und

die vielen Kräfte deiner vielen Zukunft

schweigend herabbogst zu dem neuen Kindkeim,

der wieder Schicksal war. O wehe Arbeit.

O Arbeit über alle Kraft. Du tatest

sie Tag für Tag, du schlepptest dich zu ihr

und zogst den schönen Einschlag aus dem Webstuhl

und brauchtest alle deine Fäden anders.

Und endlich hattest du noch Mut zum Fest.

Denn da’s getan war, wolltest du belohnt sein,

wie Kinder, wenn sie bittersüßen Tee

getrunken haben, der vielleicht gesund macht.

So lohntest du dich: denn von jedem andern

warst du zu weit, auch jetzt noch; keiner hätte

ausdenken können, welcher Lohn dir wohltut.

Du wußtest es. Du saßest auf im Kindbett,

und vor dir stand ein Spiegel, der dir alles

ganz wiedergab. Nun war das alles Du

und ganz davor, und drinnen war nur Täuschung,

die schöne Täuschung jeder Frau, die gern

Schmuck umnimmt und das Haar kämmt und verändert.

So starbst du, wie die Frauen früher starben,

altmodisch starbst du in dem warmen Hause

den Tod der Wöchnerinnen, welche wieder

sich schließen wollen und es nicht mehr können,

weil jenes Dunkel, das sie mitgebaren,

noch einmal wiederkommt und drängt und eintritt.

Ob man nicht dennoch hätte Klagefrauen

auftreiben müssen? Weiber, welche weinen

für Geld, und die man so bezahlen kann,

daß sie die Nacht durch heulen, wenn es still wird.

Gebräuche her! wir haben nicht genug

Gebräuche. Alles geht und wird verredet.

So mußt du kommen, tot, und hier mit mir

Klagen nachholen. Hörst du, daß ich klage?

Ich möchte meine Stimme wie ein Tuch

hinwerfen über deines Todes Scherben

und zerrn an ihr, bis sie in Fetzen geht,

und alles, was ich sage, müßte so

zerlumpt in dieser Stimme gehn und frieren;

blieb es beim Klagen. Doch jetzt klag ich an:

den Einen nicht, der dich aus dir zurückzog,

(ich find ihn nicht heraus, er ist wie alle)

doch alle klag ich in ihm an: den Mann.

Wenn irgendwo ein Kindgewesensein

tief in mir aufsteigt, das ich noch nicht kenne,

vielleicht das reinste Kindsein meiner Kindheit:

ich wills nicht wissen. Einen Engel will

ich daraus bilden ohne hinzusehn

und will ihn werfen in die erste Reihe schreiender

Engel, welche Gott erinnern.

Denn dieses Leiden dauert schon zu lang,

und keiner kanns; es ist zu schwer für uns,

das wirre Leiden von der falschen Liebe,

die, bauend auf Verjährung wie Gewohnheit,

ein Recht sich nennt und wuchert aus dem Unrecht.

Wo ist ein Mann, der Recht hat auf Besitz?

Wer kann besitzen, was sich selbst nicht hält,

was sich von Zeit zu Zeit nur selig auffängt

und wieder hinwirft wie ein Kind den Ball.

Sowenig wie der Feldherr eine Nike

festhalten kann am Vorderbug des Schiffes,

wenn das geheime Leichtsein ihrer Gottheit

sie plötzlich weghebt in den hellen Meerwind:

so wenig kann einer von uns die Frau

anrufen, die uns nicht mehr sieht und die

auf einem schmalen Streifen ihres Daseins

wie durch ein Wunder fortgeht, ohne Unfall:

er hätte denn Beruf und Lust zur Schuld.

Denn das ist Schuld, wenn irgendeines Schuld ist:

die Freiheit eines Lieben nicht vermehren

um alle Freiheit, die man in sich aufbringt.

Wir haben, wo wir lieben, ja nur dies:

einander lassen; denn daß wir uns halten,

das fällt uns leicht und ist nicht erst zu lernen.

Bist du noch da? In welcher Ecke bist du? –

Du hast so viel gewußt von alledem

und hast so viel gekonnt, da du so hingingst

für alles offen, wie ein Tag, der anbricht.

Die Frauen leiden: lieben heißt allein sein,

und Künstler ahnen manchmal in der Arbeit,

daß sie verwandeln müssen, wo sie lieben.

Beides begannst du; beides ist in Dem,

was jetzt ein Ruhm entstellt, der es dir fortnimmt.

Ach du warst weit von jedem Ruhm. Du warst

unscheinbar; hattest leise deine Schönheit

hineingenommen, wie man eine Fahne

einzieht am grauen Morgen eines Werktags,

und wolltest nichts, als eine lange Arbeit, –

die nicht getan ist: dennoch nicht getan.

Wenn du noch da bist, wenn in diesem Dunkel

noch eine Stelle ist, an der dein Geist

empfindlich mitschwingt auf den flachen Schallwelln,

die eine Stimme, einsam in der Nacht,

aufregt in eines hohen Zimmers Strömung:

So hör mich: Hilf mir. Sieh, wir gleiten so,

nicht wissend wann, zurück aus unserm Fortschritt

in irgendwas, was wir nicht meinen; drin

wir uns verfangen wie in einem Traum

und drin wir sterben, ohne zu erwachen.

Keiner ist weiter. Jedem, der sein Blut

hinaufhob in ein Werk, das lange wird,

kann es geschehen, daß ers nicht mehr hochhält

und daß es geht nach seiner Schwere, wertlos.

Denn irgendwo ist eine alte Feindschaft

zwischen dem Leben und der großen Arbeit.

Daß ich sie einseh und sie sage: hilf mir.

Komm nicht zurück. Wenn du’s erträgst, so sei

tot bei den Toten. Tote sind beschäftigt.

Doch hilf mir so, daß es dich nicht zerstreut,

wie mir das Fernste manchmal hilft: in mir.

Rainer Maria Rilke: Requiem. Für eine Freundin (1908)

fleursdumal.nl m a g a z i n e

More in: Archive Q-R, Rilke, Rainer Maria

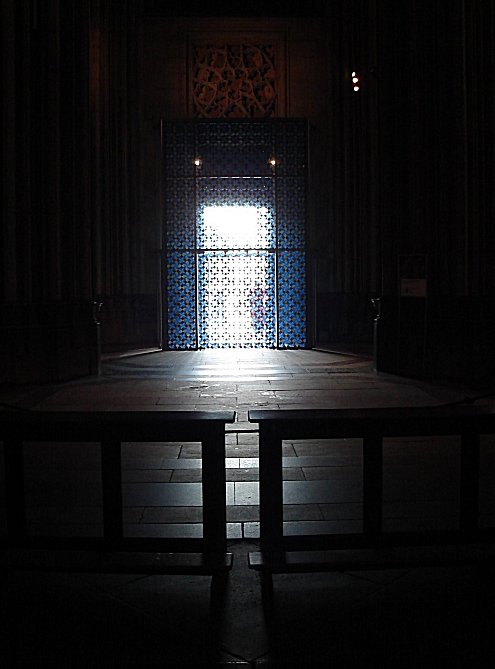

.jpg)

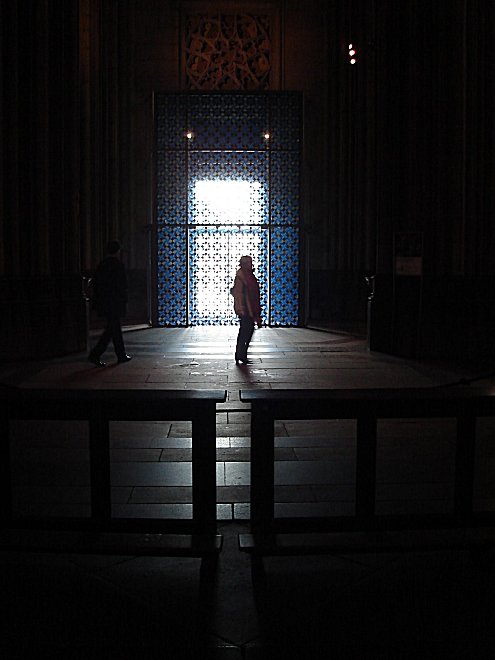

Monica Richter: Die Tür -2

![]()

Monica Richter: Die Tür -2

Kölner Dom 2009

![]()

kemp=mag poetry magazine – magazine for art & literature

More in: Monica Richter, Richter, Monica

W i l l i a m S h a k e s p e a r e

(1564-1616)

T H E S O N N E T S

1

From fairest creatures we desire increase,

That thereby beauty’s rose might never die,

But as the riper should by time decease,

His tender heir might bear his memory:

But thou contracted to thine own bright eyes,

Feed’st thy light’s flame with self-substantial fuel,

Making a famine where abundance lies,

Thy self thy foe, to thy sweet self too cruel:

Thou that art now the world’s fresh ornament,

And only herald to the gaudy spring,

Within thine own bud buriest thy content,

And tender churl mak’st waste in niggarding:

Pity the world, or else this glutton be,

To eat the world’s due, by the grave and thee.

![]()

k e m p i s p o e t r y m a g a z i n e

More in: -Shakespeare Sonnets

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

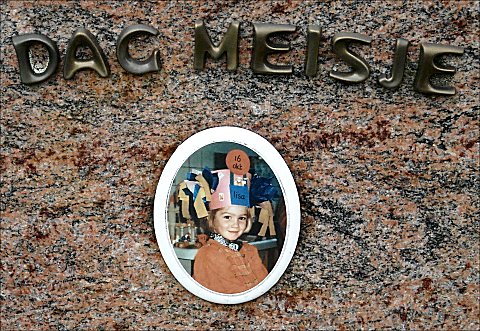

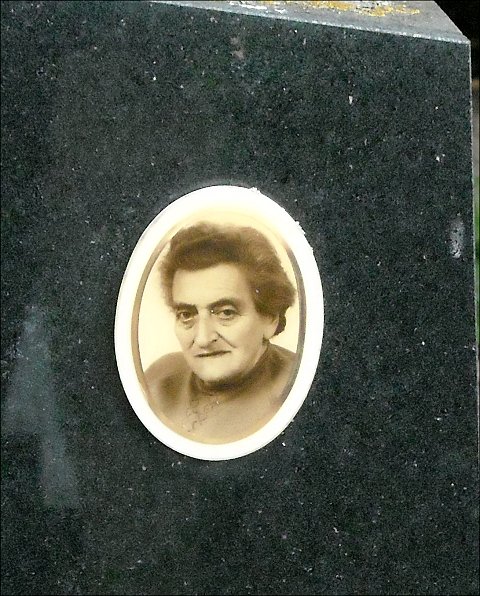

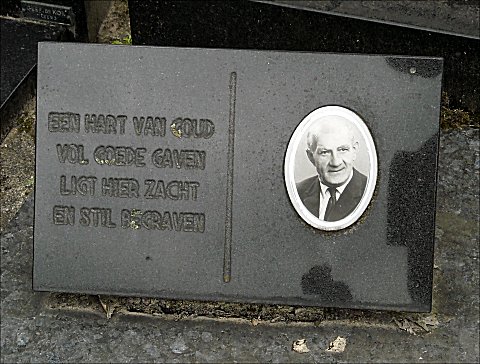

G A L E R I E D E S M O R T S XIII

Les morts de Tilburg NL (De Schans) – © photos kempis

kempis poetry magazine – magazine for art & literature

m u s e u m o f l o s t c o n c e p t s

More in: Galerie des Morts

.jpg)

C h a r l e s B a u d e l a i r e

(1821-1867)

6 P o è m e s

Le serpent qui danse

Que j’aime voir, chère indolente,

De ton corps si beau,

Comme une étoile vacillante,

Miroiter la peau!

Sur ta chevelure profonde

Aux âcres parfums,

Mer odorante et vagabonde

Aux flots bleus et bruns.

Comme un navire qui s’éveille

Au vent du matin,

Mon âme rêveuse appareille

Pour un ciel lointain.

Tes yeux, où rien ne se révèle

De doux ni d’amer,

Sont deux bijoux froids où se mêle

L’or avec le fer.

A te voir marcher en cadence,

Belle d’abandon,

On dirait un serpent qui danse

Au bout d’un bâton;

Sous le fardeau de ta paresse

Ta tête d’enfant

Se balance avec la mollesse

D’un jeune éléphant,

Et son corps se penche et s’allonge

Comme un fin vaisseau

Qui roule bord sur bord, et plonge

Ses vergues dans l’eau.

Comme un flot grossi par la fonte

Des glaciers grondants,

Quand l’eau de ta bouche remonte

Au bord de tes dents,

Je crois boire un vin de Bohême,

Amer et vainqueur,

Un ciel liquide qui parsème

D’étoiles mon coeur!

Tout entière

Le Démon, dans ma chambre haute,

Ce matin est venu me voir,

Et, tâchant à me prendre en faute,

Me dit: « Je voudrais bien savoir,

Parmi toutes les belles choses

Dont est fait son enchantement,

Parmi les objets noirs ou roses

Qui composent son corps charmant,

Quel est le plus doux. »–O mon âme!

Tu répondis à l’Abhorré:

« Puisqu’en elle tout est dictame,

Rien ne peut être préféré.

Lorsque tout me ravit, j’ignore

Si quelque chose me séduit.

Elle éblouit comme l’Aurore

Et console comme la Nuit;

Et l’harmonie est trop exquise,

Qui gouverne tout son beau corps,

Pour que l’impuissante analyse

En note les nombreux accords.

O métamorphose mystique

De tous mes sens fondus en un!

Son haleine fait la musique,

Comme sa voix fait le parfum! »

Que diras-tu ce soir, pauvre âme solitaire,

Que diras-tu, mon coeur, coeur autrefois flétri,

A la très belle, à la très bonne, à la très chère,

Dont le regard divin t’a soudain refleuri?

–Nous mettrons noire orgueil à chanter ses louanges,

Rien ne vaut la douceur de son autorité;

Sa chair spirituelle a le parfum des Anges,

Et son oeil nous revêt d’un habit de clarté.

Que ce soit dans la nuit et dans la solitude.

Que ce soit dans la rue et dans la multitude;

Son fantôme dans l’air danse comme un flambeau.

Parfois il parle et dit: « Je suis belle, et j’ordonne

Que pour l’amour de moi vous n’aimiez que le Beau.

Je suis l’Ange gardien, la Muse et la Madone. »

Confession

Une fois, une seule, aimable et douce femme,

A mon bras votre bras poli

S’appuya (sur le fond ténébreux de mon âme

Ce souvenir n’est point pâli).

Il était tard; ainsi qu’une médaille neuve

La pleine lune s’étalait,

Et la solennité de la nuit, comme un fleuve,

Sur Paris dormant ruisselait.

Et le long des maisons, sous les portes cochères,

Des chats passaient furtivement,

L’oreille au guet, ou bien, comme des ombres chères,

Nous accompagnaient lentement.

Tout à coup, au milieu de l’intimité libre

Eclose à la pâle clarté,

De vous, riche et sonore instrument où ne vibre

Que la radieuse gaîté,

De vous, claire et joyeuse ainsi qu’une fanfare

Dans le matin étincelant,

Une note plaintive, une note bizarre

S’échappa, tout en chancelant.

Comme une enfant chétive, horrible, sombre, immonde

Dont sa famille rougirait,

Et qu’elle aurait longtemps, pour la cacher au monde,

Dans un caveau mise au secret!

Pauvre ange, elle chantait, votre note criarde:

« Que rien ici-bas n’est certain,

Et que toujours, avec quelque soin qu’il se farde,

Se trahit l’égoïsme humain;

Que c’est un dur métier que d’être belle femme,

Et que c’est le travail banal

De la danseuse folle et froide qui se pâme

Dans un sourire machinal;

Que bâtir sur les coeurs est une chose sotte,

Que tout craque, amour et beauté,

Jusqu’à ce que l’Oubli les jette dans sa hotte

Pour les rendre à l’Eternité! »

J’ai souvent évoqué cette lune enchantée,

Ce silence et cette langueur,

Et cette confidence horrible chuchotée

Au confessionnal du coeur.

Le flacon

Il est de forts parfums pour qui toute matière

Est poreuse. On dirait qu’ils pénètrent le verre.

En ouvrant un coffret venu de l’orient

Dont la serrure grince et rechigne en criant,

Ou dans une maison déserte quelque armoire

Pleine de l’âcre odeur des temps, poudreuse et noire,

Parfois on trouve un vieux flacon qui se souvient,

D’où jaillit toute vive une âme qui revient.

Mille pensers dormaient, chrysalides funèbres,

Frémissant doucement dans tes lourdes ténèbres,

Qui dégagent leur aile et prennent leur essor,

Teintés d’azur, glacés de rose, lamés d’or.

Voilà le souvenir enivrant qui voltige

Dans l’air troublé; les yeux se ferment; le Vertige

Saisit l’âme vaincue et la pousse à deux mains

Vers un gouffre obscurci de miasmes humains;

Il la terrasse au bord d’un gouffre séculaire,

Où, Lazare odorant déchirant son suaire,

Se meut dans son réveil le cadavre spectral

D’un vieil amour ranci, charmant et sépulcral.

Ainsi, quand je serai perdu dans la mémoire

Des hommes, dans le coin d’une sinistre armoire;

Quand on m’aura jeté, vieux flacon désolé,

Décrépit, poudreux, sale, abject, visqueux, fêlé,

Je serai ton cercueil, aimable pestilence!

Le témoin de ta force et de ta virulence,

Cher poison préparé par les anges! liqueur

Qui me ronge, ô la vie et la mort de mon coeur!

Le poison

Le vin sait revêtir le plus sordide bouge

D’un luxe miraculeux,

Et fait surgir plus d’un portique fabuleux

Dans l’or de sa vapeur rouge,

Comme un soleil couchant dans un ciel nébuleux.

L’opium agrandit ce qui n’a pas de bornes,

Allonge l’illimité,

Approfondit le temps, creuse la volupté,

Et de plaisirs noirs et mornes

Remplit l’âme au delà de sa capacité.

Tout cela ne vaut pas le poison qui découle

De tes yeux, de tes yeux verts,

Lacs où mon âme tremble et se voit à l’envers…

Mes songes viennent en foule

Pour se désaltérer à ces gouffres amers.

Tout cela ne vaut pas le terrible prodige

De ta salive qui mord,

Qui plonge dans l’oubli mon âme sans remord,

Et, charriant le vertige,

La roule défaillante aux rives de la mort!

Femmes damnés

Comme un bétail pensif sur le sable couchées,

Elles tournent leurs yeux vers l’horizon des mers,

Et leurs pieds se cherchant et leurs mains rapprochées

Ont de douces langueurs et des frissons amers:

Les unes, coeurs épris des longues confidences,

Dans le fond des bosquets où jasent les ruisseaux,

Vont épelant l’amour des craintives enfances

Et creusent le bois vert des jeunes arbrisseaux;

D’autres, comme des soeurs, marchent lentes et graves

A travers les rochers pleins d’apparitions,

Où saint Antoine a vu surgir comme des laves

Les seins nus et pourprés de ses tentations;

Il en est, aux lueurs des résines croulantes,

Qui dans le creux muet des vieux antres païens

T’appellent au secours de leurs fièvres hurlantes,

O Bacchus, endormeur des remords anciens!

Et d’autres, dont la gorge aime les scapulaires,

Qui, recelant un fouet sous leurs longs vêtements,

Mêlent dans le bois sombre et les nuits solitaires

L’écume du plaisir aux larmes des tourments.

O vierges, ô démons, ô monstres, ô martyres,

De la réalité grands esprits contempteurs,

Chercheuses d’infini, dévotes et satyres,

Tantôt pleines de cris, tantôt pleines de pleurs,

Vous que dans votre enfer mon âme a poursuivies,

Pauvres soeurs, je vous aime autant que je vous plains,

Pour vos mornes douleurs, vos soifs inassouvies,

Et les urnes d’amour dont vos grands coeurs sont pleins!

C h a r l e s B a u d e l a i r e p o e t r y

fleursdumal.nl magazine – magazine for art & literature

More in: Archive A-B, Baudelaire, Baudelaire, Charles

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature