Fleurs du Mal Magazine

William Shakespeare

(1564-1616)

THE SONNETS

Sonnet 133

Beshrew that heart that makes my heart to groan

For that deep wound it gives my friend and me;

Is’t not enough to torture me alone,

But slave to slavery my sweet’st friend must be?

Me from my self thy cruel eye hath taken,

And my next self thou harder hast engrossed,

Of him, my self, and thee I am forsaken,

A torment thrice three-fold thus to be crossed:

Prison my heart in thy steel bosom’s ward,

But then my friend’s heart let my poor heart bail,

Whoe’er keeps me, let my heart be his guard,

Thou canst not then use rigour in my gaol.

And yet thou wilt, for I being pent in thee,

Perforce am thine and all that is in me.

![]()

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shakespeare Sonnets

Immer wieder, ob wir der Liebe Landschaft

Immer wieder, ob wir der Liebe Landschaft auch kennen

und den kleinen Kirchhof mit seinen klagenden Namen

und die furchtbar verschweigende Schlucht, in welcher die andern

enden: immer wieder gehn wir zu zweien hinaus

unter die alten Bäume, lagern uns immer wieder

zwischen die Blumen, gegenüber dem Himmel.

Rainer Maria Rilke

(1875-1926)

Hans Hermans photos – Natuurdagboek 03-12

Gedicht Rainer Maria Rilke

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Hans Hermans Photos, Rilke, Rainer Maria

J.A. Woolf: Making memories (18)

kempis.nl poetry magazine 2012

More in: J.A. Woolf

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (22)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926). The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator by Luigi Pirandello. Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK IV

5

I think that it would be a good thing for me if I had a different mind and a different heart.

Who will exchange with me?

Given my intention, which grows steadily more determined, to remain an impassive spectator, this mind, this heart are of little use to me. I have reason to believe (and more than once, before now, I have been glad of it) that the reality in which I invest other people corresponds exactly to the reality in which those people invest themselves, because I endeavour to feel them in myself as they feel themselves, to wish for them as they wish for themselves: a reality, therefore, that is entirely disinterested. But I see at the same time that, without meaning it, I am letting myself be caught by that reality which, being what it is, ought to remain outside me: matter, to which I give a form, not for my sake, but for its own; something to contemplate.

No doubt, there is an underlying deception, a mocking deception in all this. I see myself caught. So much so, that I am no longer able even to smile, if, beside or beneath a complication of circumstances or passions which grows steadily stronger and more unpleasant, I see escape some other circumstance or some other passion that might be expected to raise my spirits. The case of Signorina Luisetta Cavalena, for instance.

The other day Polacco had the inspiration to make that young lady come to the Bosco Sacro and there take a small part in a film. I know that, to engage her to take part in the remaining scenes of the film, he has sent her father a five hundred lire note and, as he promised, a pretty sunshade for herself and a collar with lots of little silver bells for the old dog, Piccini. He ought never to have done such a thing I It appears that Cavalena had given his wife to understand that, when he went with his scenarios to the Kosmograph, each with its inevitable gallant suicide, and all of them, therefore, invariably rejected, he never saw anyone there, except Cocò Polacco: Cocò Polacco and then home again. And who knows how he had described to her the interior of the Kosmograph: perhaps as an austere hermitage, from which all women were resolutely banished, like demons. Only, alas, the other day, the fierce wife, becoming suspicious, decided to accompany her husband. I do not know what she saw, but I can easily imagine it. The fact remains that this morning, just as I was going into the Kosmograph, I saw all four Cavalena arrive in a carriage: husband, wife, daughter and little dog: Signorina Luisetta, pale and trembling; Piccini, more surly than ever; Cavalena, looking as usual like a mouldy lemon, among the curls of his wig that protruded from under his broad-brimmed hat; his wife, like a cyclone barely held in check, her hat knocked askew as she dismounted from the carriage.

Under his arm Cavalena had the long parcel containing the sunshade presented by Polacco to his daughter and in his hand the box containing Piccini’s collar. He had come to return them.

Signorina Luisetta recognised me at once. I hastened up to her to greet her; she wished to introduce me to her mother and father, but could not remember my name. I helped her out of her difficulty, by introducing myself.

“The operator, the man who turns the handle, you understand, Nene?” Cavalena at once explained, with timid haste, to his wife, smiling, as though to implore a little condescension.

Heavens, what a face Signora Nene has! The face of an old, colourless doll. A compact helmet of almost quite grey hair presses upon her low, hard forehead, on which her eyebrows, joined together, short, bushy, and straight, are like a line boldly ruled to give a character of stupid tenacity to the pale eyes that gleam with a glassy stiffness. She seems apathetic; but, if you study her closely, you observe on the surface of her skin certain strange nervous prickings, certain sudden changes of colour, in patches, which at once disappear. She also, every now and then, makes rapid unexpected gestures, of the most curious nature. I caught her, for instance, at one moment, in reply to a beseeching glance from her daughter, shaping her mouth in a round O across which she laid her finger. Evidently, this gesture was intended to mean:

“Silly girl! Why do you look at me like that?”

But they are always looking at her, surreptitiously at least, her husband and daughter, perplexed and anxious in their fear lest at any moment she may indulge in some flaming outburst of rage. And certainly, by looking at her like that, they irritate her all the more. But imagine the life they lead, poor creatures!

Polacco has already given me some account of it. Perhaps she never thought of becoming a mother, this woman! She found this poor man, who, in her clutches, after all these years, has been reduced to the most pitiable condition imaginable; no matter: she will fight for him; she continues to fight for him savagely. Polacco tells me that, when assailed by the furies of jealousy, she loses all self-restraint; and in front of everyone, without a thought even of her daughter who stands listening, looking on, she strips bare (bare, as they flash before her eyes in those moments of fury) and lashes her husband’s alleged misdeeds: misdeeds that are highly improbable. Certainly, in that hideous humiliation, Signorina Luisetta cannot fail to see her father in a ridiculous light, albeit, as can be seen from the way in which she looks at him, he must arouse so much pity in her! Ridiculous, from the way in which, stripped bare, lashed, the poor man still seeks to gather up from all sides, to cover himself in them hastily and as best he may, the shreds and tatters of his dignity. Cocò Polacco has repeated to me some of the phrases in which, stunned by her savage, unexpected onslaughts, he replies to his wife at such moments: sillier, more ingenuous, more puerile things one could not imagine! And for that reason alone I am convinced that Cocò Polacco did not invent them himself.

“Nene, for pity’s sake, I am a man of five and forty…

“Nene, I have held His Majesty’s commission …

“Nene, good God, when a man has held a commission and gives you his word of honour…”

And yet, every now and then–oh, in the long run even a worm will turn–wounded with a refinement of cruelty in his most sacred feelings, barbarously chastised where the lash hurts most–every now and then, he says, it appears that Cavalena escapes from the house, bolts from his prison. Like a madman, at any moment he may be found wandering in the street, without a penny in his pocket, determined to “take up the threads of his life again” somewhere or other. He goes here and there in search of friends; and his friends, at first, welcome him joyously in the ‘caffè’, in the newspaper offices, because they like to see him enjoying himself; but the warmth of their welcome begins at once to cool as soon as he expresses his urgent need of finding employment once more among them, without a moment’s delay, in order that he may be able to provide for himself as quickly as possible. Yes indeed! Because he has not even the price of a cup of coffee, a mouthful of supper, a bed in an inn for the night. Who will oblige him, for the time being, with twenty lire or so? He makes an appeal, among the journalists, to the spirit of old comradeship. He will come round next day with an article to his old paper. What? Yes, something literary or light and scientific. He has ever so much material stored up in his head… new stuff, you know…. Such as? Oh, Lord, such as, well, this…”

He has not finished speaking, before all these good friends burst out laughing in his face. New stuff? Why, Noah used to tell that to his sons, in the ark, to beguile the tedium of their voyage over the waters of the Deluge….

Ah, I too know them well, those old friends of the ‘caffè’! They all talk like that, in a forced burlesque manner, and each of them becomes excited by the verbal exaggerations of the rest and takes courage to utter an even grosser exaggeration, which does not however exceed the limit, does not depart from the tone, so as not to be received with a general outcry; they laugh at one another in turn, making a sacrifice of all their most cherished vanities, fling them in one another’s face with gay savagery, and apparently no one takes offence; but the resentment within grows, the bile ferments; the effort to keep the conversation in that burlesque tone which provokes laughter, because amid general laughter insults are tempered and lose their gall, becomes gradually more laboured and difficult; then, the prolonged, sustained effort leaves in each of them a weariness of anger and disgust; each of them is conscious with bitter regret of having done violence to his own thoughts, to his own feelings; more than remorse, an outraged sincerity; an inward uneasiness, as though the swelling, infuriated spirit no longer adhered to its own intimate substance; and they all heave deep sighs to rid themselves of the hot air of their own disgust; but, the very next day, they all fall back into that furnace, and scorch themselves, afresh, miserable grasshoppers, doomed to saw frantically away at their own shell of boredom.

Woe to him who arrives a newcomer, or returns after a certain interval to their midst! But Cavalena perhaps does not take offence, does not complain of the sacrifice that his good friends make of him, tortured as he is in his heart by the discovery that he has failed, in his seclusion, to “keep in touch with life.” Since his last escape from the prison-house there have passed, shall we say, eighteen months? Well; it is as though there had passed eighteen centuries! All of them, as they hear issuing from his lips certain slang expressions, then the very latest thing, which he has preserved like precious jewels in the strong-box of his memory, screw up their faces and gaze at him, as one gazes in a chop-house at a warmed-up dish, which smells of rancid fat a mile off! Oh, poor Cavalena, just listen to him! Listen to him! He still admires the man who, eighteen months ago, was the greatest man of the twentieth century. But who was that? Ah, listen…. So and so of Such and such…. That idiot! That bore! That dummy! What, is he still alive? No, not really alive? Yes, Cavalena swears he saw him, actually alive, only a week ago; in fact, believing that… (no, as far as being alive goes, he is alive) still, if he is no longer a great man… why, he proposed to write an article about him … he won’t write it now!

Utterly abased, his face livid with bile, but with patches of red here and there, as though his friends in their mortification of him had amused themselves by pinching him on the brow, the cheeks, the nose, Cavalena meanwhile is inwardly devouring his wife, like a cannibal after a three-days’ fast: his wife, who has made him a public laughing-stock. He swears to himself that he will never again let himself fall into her clutches; but gradually, alas, his anxiety to resume “life” begins to transform itself into a mania which at first he is unable to define, but which becomes steadily more and more exasperating within him. For years past he has exercised all his mental faculties in defending his own dignity against the unjust suspicions of his wife. And now his faculties, suddenly diverted from this assiduous, desperate defence, are no longer adaptable, must make an effort to convert themselves and to devote themselves to other uses. But his dignity, so long and so strenuously defended, has now settled upon him, like the mould of a statue, immovable. Cavalena feels himself empty inside, but outwardly incrusted all over. He has become the walking mould of this statue. He cannot any longer scrape it off himself. Forever, henceforward, inexorably, he is the most dignified man in the world. And this dignity of his has so exquisite a sensibility that it takes umbrage, grows disturbed at the slightest indication that is vouchsafed to it of the most trifling transgression of his duties as a citizen, a husband, the father of a family. He has so often sworn to his wife that he has never proved false, even in thought, to these duties, that really now he cannot even think of transgressing them, and suffers, and turns all the colours of the rainbow when he sees other people so light-heartedly transgressing them. His friends laugh at him and call him a hypocrite. There, in their midst, incrusted all over, amid the noise and impetuous volubility of a life that knows no restraint either of faith or of affection, Cavalena feels himself outraged, begins to imagine that he is in serious peril; he has the impression that he is standing on feet of glass in the midst of a tumult of madmen who trample on him with iron shoes. The life imagined in his seclusion as full of attractions and indispensable to him reveals itself as being vacuous, stupid, insipid. How can he have suffered so keenly from being deprived of the company of these friends; of the spectacle of all their fatuity, all the wretched disorder of their life?

Poor Cavalena! The truth perhaps lies elsewhere! The truth is that in his harsh seclusion, without meaning it, he has become too much accustomed to converse with himself, that is to say with the worst enemy that any of us can have; and thus has acquired a clear perception of the futility of everything, and has seen himself thus lost, alone, surrounded by shadows and crushed by the mystery of himself and of everything. … Illusions? Hopes? Of what use are they? Vanity…. And his own personality, prostrated, annulled in itself, has gradually re-arisen as a pitiful consciousness of other people, who are ignorant and deceive themselves, who are ignorant and labour and love and suffer. What fault is it of his wife, his poor Nene, if she is so jealous? He is a doctor and knows that this fierce jealousy is really and truly a mental disease, a form of reasoning madness. Typical, a typical form of paranoia, with persecution mania too. He goes about telling everybody. Typical! Typical! She has finally come to suspect, his poor Nene, that he is seeking to kill her, in order to take possession, with the daughter, of her money! Ah, what an ideal life they would lead then, without her…. Liberty, liberty: one foot here, the other there! She says this, poor Nene, because she herself perceives that life, as she makes it for herself and for the others, is not possible, it is the destruction of life; she destroys herself, poor Nene, with her ravings, and naturally supposes that the others wish to destroy her: with a knife, no, because it would be discovered! By concentrated spite! And she does not observe that the spite originates with herself; originates in all the phantoms of her madness to which she gives substance. But is not he a doctor? And if he, as a doctor, understands all this, does it not follow that he ought to treat his poor Nene as a sick patient, not responsible for the harm she has done him and continues to do him? Why rebel? Against whom? He ought to feel for her and to shew pity, to stand by her lovingly, to endure with patience and resignation her inevitable cruelty. And then there is poor Luisetta, left alone in that hell, at the mercy of that mother who does not stop to think…. Ah, off with him, he must return home at once! At once. Perhaps, underlying his decision, masked by this pity for his wife and daughter, there is the need to escape from that precarious and uncertain life, which is no longer the life for him. Is he not, moreover, entitled to feel some pity for himself also? Who has brought him down to this state? Can he at his age take up life again, after having severed all the ties, after having closed all the doors, to please his wife? And, in the end, he goes back to shut himself up in his prison!

The poor man bears so clearly displayed in his whole appearance the great disaster that weighs upon him, he makes it so plainly visible in the embarrassment of his every step, his every glance, when he has his wife with him, by his constant terror lest she, in that step, in that glance, may find a pretext for a scene, that one cannot help laughing at him, sympathise with him as one may.

And perhaps I should have laughed at him too, this morning, had not Signorina Luisetta been there. Who knows what she is made to suffer by the inevitable absurdity of her father, poor girl.

A man of five and forty, reduced to that condition, whose wife is still so fiercely jealous of him, cannot fail to be grotesquely absurd! All the more so since, owing to another hidden tragedy, an indecent precocious baldness, the effect of typhoid fever, which he managed by a miracle to survive, the poor man is obliged to wear that artistic wig under a hat large enough to cover it. The effrontery of this hat and of all those curled locks that protrude from it is in such marked contrast to the frightened, shocked, cautious expression of his face, that it is nothing short of ruination to his seriousness, and must also, certainly, be a constant grief to his daughter.

“No, one moment, my dear Sir… excuse me, what did you say your name was!”

“Gubbio.”

“Gubbio, thanks. Mine is Cavalena, at your service.”

“Cavalena, thanks, I know.”

“Fabrizio Cavalena: in Rome I am better known as…”

“I should say so, a buffoon!”

Cavalena turned round, pale as death, his mouth agape, to gaze at his wife.

“Buffoon, buffoon, buffoon,” she reiterated, three times in succession.

“Nene, for heaven’s sake, shew some respect. …” Cavalena began threateningly; but all of a sudden he broke off: shut his eyes, screwed up his face, clenched his fists, as though seized by a sudden, sharp internal spasm…. Not at all! It was the tremendous effort which he has to make every time to contain himself, to wring from his infuriated animal nature the consciousness that he is a doctor and ought therefore to treat and to pity his wife as a poor sick person.

“May I?”

And he took my arm in his, to draw me a little way apart.

“Typical, you know? Poor thing…. Ah, it requires true heroism, believe me, the greatest heroism on my part to put up with her. I should not be able, perhaps, if it were not for my poor child here. But there! I was saying just now … this Polacco, God in heaven… this Polacco! But I ask you, is it a trick to play upon a friend, knowing my misfortune? He carries my daughter off to , pose’… with a light woman… with an actor who, notoriously… Can you imagine the scene that occurred at home! And then he sends me these presents… a collar too for the animal… and five hundred lire!”

I tried to make it clear to him that, so far at any rate as the presents and the five hundred lire went, it did not appear to me that there was any such harm in them as he chose to make out. He? But he saw no harm in them whatsoever! What harm should there bel He was delighted, overjoyed at what had happened! Most grateful in his heart of hearts to Polacco for having given that little part to his daughter! He had to pretend to be so indignant to appease his wife. I noticed this at once, as soon as I had begun to speak. He was enraptured with the argument that I set before him, proving that after all no harm had been done. He gripped me by the arm, led me impetuously back to his wife.

“Do you hear? Do you hear?… I know nothing about it…. This gentleman says… Tell her, will you please, tell her what you said to me. I don’t wish to open my mouth…. I came here with the presents and the five hundred lire, you understand? To hand everything back. But if that would be, as this gentleman says… I know nothing about it… a gratuitous insult … replying with rudeness to a person who never had the slightest intention to offend us, to do us any harm, because he thinks that… I know nothing, I know nothing… that there is no occasion… I beg of you, in heaven’s name, my dear Sir, do you speak… repeat to my wife what you have been so kind as to say to me!”

But his wife did not give me time to speak: she sprang upon me with the glassy, phosphorescent eyes of a maddened cat.

“Don’t listen to this buffoon, hypocrite, clown! It is not his daughter he’s thinking about, it is not the figure he would cut! He wants to hang about here all day, because here it would be like being in his own garden, with all the pretty ladies he’s so fond of, artists like himself, mincing round him! And he’s not ashamed, the scoundrel, to put his daughter forward as an excuse, to shelter behind his daughter, at the cost of compromising her and ruining her, the wretch!

He would have the excuse of bringing his daughter here, you understand? He would come here for his daughter!”

“But you would come too,” Fabrizio Cavalena shouted, losing all patience. “Aren’t you here too? With me?”

“I?” roared his wife. “I, here?”

“Why not?” Cavalena went on unperturbed; and, turning again to myself: “Tell her, you tell her, does not Zeme come here as well?”

“Zeme?” inquired the wife in perplexity, knitting her brows. “Who is Zeme?”

“Zeme, the Senator!” exclaimed Cavalena. “A Senator of the Realm, a scientist of world-wide fame!”

“He must be as big a clown as yourself!”

“Zeme, who goes to the Quirinal? Invited to all the State Banquets? The venerable Senator Zeme, the pride of Italy! The Keeper of the Astronomical Observatory! Good Lord, you ought to be ashamed of yourself! Shew some respect, if not for me, for one of the glories of the country! He has been here, hasn’t he? But speak, my dear Sir, tell her, for pity’s sake, I beg of you! Zeme has been here, he has helped to arrange a film, hasn’t he? He, Senator Zeme! And if Zeme comes here, if Zeme offers his services, a world-famous scientist, then, I mean to say… surely I can come here too, can offer my services too…. But it doesn’t matter to me in the least! I shall not come again! I am speaking now to make it clear to this woman that this is not a place of ill-fame, to which I, for immoral purposes, am seeking to lead my daughter to her ruin! You will understand, my dear Sir, and forgive me: this is why I am speaking. It burns my ears to hear it said in front of my daughter that I wish to compromise her, to ruin her, by taking her to a place of ill-fame. … Come, come, do me a favour: take me in at once to Polacco, so that I may give him back these presents and the money, and thank him for them. When a man has the misfortune to possess a wife like mine, he ought to dig a grave for himself, and finish things off once and for all! Take me in to Polacco!”

What happened was not my fault on this occasion either, but, flinging open carelessly, without knocking, the door of the Art Director’s office, in which Polacco was to be found, I saw inside a spectacle which at once altered my state of mind completely, so that I was no longer able to give a thought to Cavalena, nor indeed to see anything clearly.

Huddled in the chair by Polacco’s desk a man was sobbing, his face buried in his hands, desperately.

Immediately Polacco, seeing the door open, raised his head abruptly and made an angry sign to me to shut it.

I obeyed. The man who was sobbing inside the room was unquestionably Aldo Nuti. Cavalena, his wife, his daughter, looked at me in bewilderment.

“What is it?” Cavalena asked.

I could barely find the breath to answer:

“There’s… there’s some one there….”

Shortly afterwards, there issued from the Art Director’s office Cocò Polacco, in evident confusion. He saw Cavalena and made a sign to him to wait:

“You here? Excellent. I want to speak to you.”

And without so much as a thought of greeting the ladies, he took me by the arm and drew me aside.

“He has come! He simply must not be left alone for a minute! I have mentioned you to him. He remembers you perfectly. Where are your lodgings? Wait a minute! Do you mind….”

He turned and called to Cavalena.

“You let a couple of rooms, don’t you? Are they vacant just now?”

“I should think so!” sighed Cavalena. “For the last three months and more….”

“Gubbio,” Polacco said to me, “I want you to give up your lodgings at once; pay whatever you have to pay, a month’s rent, two months’, three months’; take one of these two rooms at Cavalena’s. The other will be for him.”

“Delighted!” Cavalena exclaimed radiant, holding out both his hands to me.

“Hurry up,” Polacco went on. “Off with you! You, go and get the rooms ready; you, pack up your traps and transport everything at once to Cavalena’s. Then come back here! Is that all quite clear?”

I threw open my arms, resigned.

Polacco retired to his room. And I drove off with the Cavalena family, bewildered, and most anxious to have from me an explanation of all this mystery.

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (22)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shoot!

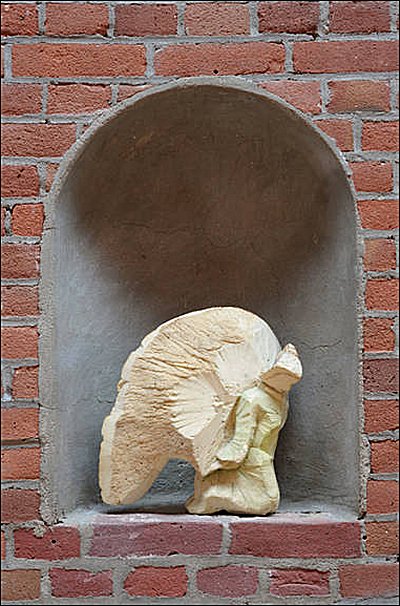

Rob Birza, De engel van Tilburg, Museum De Pont Tilburg

Engel verstopt

Eenieder heeft een sprookje nodig

Al is ’t maar om de dag goed door te komen

En niemand kan eraan ontkomen

We zijn allen een beetje gelovig

Een nis als plek, tentoongesteld.

Of juist aan ’t zicht ontweken

Dit is waar ik ben neergestreken

Betekenis op het beeld gespeld

Jaloers zou ik zijn, op de mensen

Ik weet niets van goed en kwaad

Weet niks van liefde, lust of haat

Zou ’t amper kunnen wensen

Zwichtend voor de Grote Hand

Die leven vonkte op de aarde

Waar jullie eeuwenlang voor naar kruizen staarden

Als zwaarte lichtheid overmant

Wie zou ik moeten benijden dan?

De wezens die niets geloven?

Die niet durven dromen dat ze hopen?

Ik weet niet hoe misschien, en kán.

Zuiver mogelijk is wat ik benijd

Het alles kunnen zijn en meer

Maar ik was alles wat je wilde en weer

Zou ik alles kunnen zijn.

Ik zou uit andere verhalen willen stelen

Over keizers en ridders en vrouwen van sneeuw

Jachthonden die prinsen redden en monniken leeuwen

Maar wie wil er in mijn sprookje delen?

Esther Porcelijn

Voor: ‘De Engel van Tilburg’. Rob Birza, Museum De Pont , 23 juni 2012

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Porcelijn, Esther

William Shakespeare

Sonnet 132

Thine eyes I love, and they as pitying me,

Knowing thy heart torment me with disdain,

Have put on black, and loving mourners be,

Looking with pretty ruth upon my pain.

And truly not the morning sun of heaven

Better becomes the grey cheeks of the east,

Nor that full star that ushers in the even

Doth half that glory to the sober west

As those two mourning eyes become thy face:

O let it then as well beseem thy heart

To mourn for me since mourning doth thee grace,

And suit thy pity like in every part.

Then will I swear beauty herself is black,

And all they foul that thy complexion lack.

William Shakespeare

Sonnet 132

Ik heb jouw ogen lief, en zij uit deernis mij

Maar kwellen mij, jouw hart ziend als ontrouw;

Dus zwart gefloerst in liefde treuren zij,

Mijn pijn aanschouwend in hun fraaie rouw.

Voorwaar, de hemelzon in ochtendluister

Verlicht de grijze oostwang minder goed,

Ook wordt het westen dof in avondduister

Door Venus veel halfslachtiger begroet

Dan elk oog jouw gelaat met rouwen viert:

O, dat het evenzeer jouw hart bekoort

Voor mij te rouwen, daar zo’n rouw jou siert,

Waarmee elk deel je deernis toebehoort.

Dan zweer ‘k dat schoonheid zelf met zwart verkeert,

En elk als klad oogt die jouw kleur ontbeert.

Vertaald door Cornelis W. Schoneveld, juni 2012

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Shakespeare

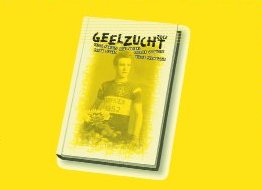

Vier van de vijf dichters van het collectief GeelZucht:v.l.n.r. Patrick Cornillie, Bert Bevers, Frank Pollet en Yella Arnouts. Willie Verhegghe was op dat moment de Kemmelberg aan het bedwingen…. (foto Moniek Vermeulen)

GeelZucht III

FLEURSDUMAL-medewerker Bert Bevers is een van de auteurs die dit jaar werken aan GeelZucht. Dat is een blog die de Tour de France op poëtische wijze volgt. Vijf dichters (behalve Bert Bevers zijn dat Yella Arnouts, Patrick Cornillie, Frank Pollet en Willie Verhegghe) beloven de lezers iedere dag van De Ronde om uiterlijk 19.00 uur een vers gedicht te posten dat is geïnspireerd op de rit (of de rustdag).

De poëtische krachttoer, die de derde editie beleeft, start op 30 juni met de proloog en moet 22 dagen later – rustdagen inbegrepen – minstens evenveel nieuwe schrijfsels opleveren.

Een en ander is te volgen op de druk bezochte blog www.geelzucht.wordpress.com

Ook gastdichters kunnen er met hun poëzie over de Tour 2012 terecht. De gedichten van het vijftal verschijnen ook weer in boekvorm – evenzeer voor de derde keer. De presentatie van de papieren versie van GeelZucht III staat op de rol voor zondag 12 augustus, in de bibliotheek van Stekene.

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Bevers, Bert

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (21)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926). The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator by Luigi Pirandello. Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK IV

4

“Signor Gubbio, please: I have something to say to you.”

Night had fallen: I was hurrying along beneath the big planes of the avenue. I knew that he–Carlo Ferro–was following me, in breathless haste, so as to pass me and then perhaps to turn round, pretending to have remembered all of a sudden that he had something to say to me. I wished to deprive him of this pleasure, and kept increasing my pace, expecting at every moment that he–growing tired at length–would admit himself beaten and call out to me. As indeed he did…. I turned, as though in surprise. He overtook me and with ill-concealed annoyance asked:

“Do you mind!”

“Go on.”

“Are you going home?”

“Yes.”

“Do you live far off?”

“Some way.”

“I have something to say to you,” he repeated, and stood still, looking at me with an evil glint in his eye. “You probably know that, thank God, I can spit on the contract I have with the Kosmograph. I can secure another, just as good and better, at any moment, whenever I choose, anywhere, for myself and my lady friend. Do you know that or don’t you?”

I smiled, shrugging my shoulders:

“I can believe it, if it gives you any pleasure.”

“You can believe it, because it is the truth!” he shouted back at me, in a provocative, challenging tone.

I continued to smile; and said:

“It may be; but I do not see why you come and tell me about it, and in

that tone.”

“This is why,” he went on. “I intend to remain, my dear Sir, with the Kosmograph.”

“Remain? Why; I never even knew that you had any idea of leaving.”

“Some one else had the idea,” Carlo Ferro retorted, laying stress on the words ‘some one else’. “But I tell you that I intend to remain: do you understand?”

“I understand.”

“And I remain, not because I care about the contract, which doesn’t matter a damn to me; but because I have never yet run away from anyone!”

So saying, he took the lapel of my coat between his fingers, and gave it a tug.

“Do you mind?” it was now my turn to ask, calmly, as I removed his hand; and I felt in my pocket for a box of matches; I struck one of them to light the cigarette which I had already taken from my case and held between my lips; I drew in a mouthful or two of smoke; stood for a while with the burning match in my fingers to let him see that his words, his threatening tone, his aggressive manner, were not causing me the slightest uneasiness; then I went on, quietly: “I may possibly understand to what you wish to allude; but, I repeat, I do not understand why you come and say these things to me,”

“It is not true,” Carlo Ferro shouted. “You are pretending not to understand.”

Placidly, but in a firm voice, I replied:

“I do not see why. If you, my dear Sir, wish to provoke me, you are making a mistake; not only because you have no reason, but also because, precisely like yourself, I am not in the habit of running away from anyone.”

Whereupon, “What do you mean?” he sneered. “I have had to run pretty fast to catch you!”

I gave a hearty laugh:

“Oh, so that’s it! You really thought that I was running away from you? You are mistaken, my dear Sir, and I can prove it to you straight away. You suspect, perhaps, that I have something to do with the arrival here, shortly, of a certain person who annoys you?”

“He doesn’t annoy me in the least!”

“All the better. On the strength of this suspicion, you were capable of believing that I was running away from you?”

“I know that you were a friend of a certain painter, who committed suicide at Naples.”

“Yes. Well?”

“Well, you who have mixed yourself up in this business….”

“I? Nothing of the sort! Who told you so? I know as much about it as you; perhaps not so much as you.”

“But you must know this Signor Nuti!”

“Nothing of the sort! I saw him, some years ago, as a young man on one or two occasions, not more. I have never spoken to him.”

“Which means…”

“Which means, my dear Sir, that not knowing this Signor Nuti, and feeling annoyed at seeing myself looked at askance for the last few days by you, from the suspicion that I had mixed myself up, or wished to mix myself up in this business, I did not wish you, just now, to overtake me, and so increased my pace. That is the explanation of my ‘running away’. Are you satisfied?”

With a sudden change of expression Carlo Ferro held out his hand, saying with emotion:

“May I have the honour and pleasure of becoming your friend?”

I took his hand and answered:

“You know very well that I am so unimportant a person compared with

yourself, that the honour will be mine.”

Carlo Ferro shook himself like a bear.

“Don’t say that! You are a man who knows his own business, more than any of the others; you know, you see, and you don’t speak…. What a world, Signor Grubbio, what a wicked world we live in! How revolting! Everyone seems… what shall I say? But why must it be like this? Disguised, disguised, always disguised! Can you tell me? Why, as soon as we come together, face to face, do we become like a lot of puppets? Yes, I too; I include myself; all of us! Disguised! One putting on this air, another that…. And inside we are different! We have a heart, inside us, like… like a child hiding in a corner,

whose feelings are hurt, crying and ashamed! Yes, I assure you: the heart is ashamed! I am longing, Signor Gubbio, I am longing for a little sincerity… to be with other people as I so often am with myself, inside myself; a child, I swear to you, a new-born infant that whimpers because its precious mother, scolding it, has told it that she does not love it any more! I myself, always, when I feel the blood rush to my eyes, think of that old mother of mine, away in Sicily, don’t you know? But look out for trouble if I begin to cry! The tears in my eyes, if anyone doesn’t understand me and thinks that I am crying from fear, may at any moment turn to blood on my hands; I know it, and that is why I am always afraid when I feel the tears start to my eyes! My fingers, look, become like this!”

In the darkness of the wide, empty avenue, I saw him thrust out beneath my eyes a pair of muscular fists, savagely clenched and clawed.

Concealing with a great effort the disturbance which this unexpected outburst of sincerity aroused in me, so as not to exacerbate the secret grief that was doubtless preying upon him and had found in this outburst, unintentionally I was certain on his part, a relief which he already regretted; I modulated my voice until I felt that I could speak in such a way that he, while appreciating my sympathy for his sincerity, might be led to think rather than to feel; and said:

“You are right; that is just how it is, Signor Ferro! But inevitably, don’t you see, we put constructions upon ourselves, living as we do in a social environment…. Why, society by its very nature is no longer the natural world. It is a constructed world, even in the material sense! Nature knows no home but the den or the cave.”

“Are you alluding to me?”

“To you? No.”

“Am I of the den or of the cave?”

“Why, of course not! I was trying to explain to you why, as I look at it, people invariably lie. And I say that while nature knows no other house than the den or cave, society ‘constructs’ houses; and man, when he comes from a ‘constructed’ house, where as it is he no longer leads a natural life, entering into relations with his fellows, ‘constructs’ himself also, that is all; presents himself, not as he is, but as he thinks he ought to be or is capable of being, that is to say in a construction adapted to the relations which each of us thinks that he can form with his neighbour. And so in the heart of things, that is to say inside these constructions of ours set face to face in this way, there remain carefully hidden, behind the blinds and shutters, our most intimate thoughts, our most secret feelings. But every now and then we feel that we are stifling; we are overcome by an irresistible need to tear down blinds and shutters, and shout out into the street, in everyone’s face, our thoughts, our feelings that we have so long kept hidden and secret.”

“Quite so… quite so…” Carlo Ferro repeated his endorsement several times, his face again darkening. “But there is a person who takes up his post behind those constructions of which you speak, like a dirty cutthroat at a street corner, to spring on you behind your back, in a treacherous assault! I know such a man, here with the Kosmograph, and you know him too.”

He was alluding of course to Polacco. I at once realised that he at that moment could not be made to think. He was feeling too keenly.

“Signor Gubbio,” he went on resolutely, “I see that you are a man, and I feel that to you I can speak openly. You might give this ‘constructed’ gentleman, whom we both know, a hint of what we have been saying. I cannot talk to him; I know my own violent nature; if I once start talking to him, I may know how I shall begin, I cannot tell where I may end. Because covert thoughts, and people who act covertly, who construct themselves, to use your expression, I simply cannot stand. To me they are like serpents, and I want to crush their heads, like that … look, like that….”

He stamped twice on the ground with his heel, furiously. Then he went on:

“What harm have I done him? What harm has my lady friend done him, that he should plot against us so desperately in secret? Don’t refuse, please… please don’t… you must be straight with me, for God’s sake! You won’t do it?”

“Why, yes…”

“You can see that I am speaking to you frankly? So please! Listen; it was he, knowing that I as a matter of honour would never try to back out, it was he that suggested my name to Commendator Borgalli for killing the tiger…. He went as far as that, do you understand! To the length of catching me on a point of honour and getting rid of me! You don’t agree? But that is the idea; the intention is that and nothing else: I tell you it is, and you’ve got to believe me! Because it doesn’t require any courage, as you know, to Shoot! a tiger in a cage: it requires calm, coolness is what it requires, a firm hand, a keen eye. Very well, he nominates me! He puts me down for the part, because he knows that I can, at a pinch, be a wild beast when I’m face to face with a man, but that as a man face to face with a wild beast I am worth nothing! I have dash, calm is just what I lack! When I see a wild beast in front of me, my instinct tells me to rush at it; I have not the coolness to stand still where I am and take aim at it carefully so as to hit it in the right place. I have never shot; I don’t know how to hold a gun; I am capable of flinging it away, of feeling it a burden on my hands, do you understand? And he knows this! He knows it perfectly! And so he has deliberately wished to expose me to the risk of being torn in pieces by that animal. And with what object? But just look, just look to what a pitch that man’s perfidy has reached! He makes Nuti come here; he acts as his agent; he clears the way for him, by getting rid of me! ‘Yes, my dear fellow, come,’ will be what he has written to him, ‘I shall look after you, I shall get him out of your way! Don’t worry, but come!’ You don’t agree?”

So aggressive and peremptory was this question, that to have met it with a blunt plain-spoken dissent would have been to inflame his anger even farther. I merely shrugged my shoulders; and answered:

“What would you have me say? You yourself must admit that at this moment you are extremely excited.”

“But how can I be calm?”

“No, there is that…”

“I am quite right, it seems to me!”

“Yes, yes, of course! But when one is in that state, my dear Ferro, it is also very easy to exaggerate things.”

“Oh, so I am exaggerating, am I? Why, yes, … because people who are cool, people who reason, when they set to work quietly to commit a crime, ‘construct’ it in such a way that inevitably, if discovered, it must appear exaggerated. Of course they do! They have constructed it in silence with such cunning, ever so quietly, with gloves on, oh yes, so as not to dirty their hands! In secret, yes, keeping it secret from themselves even! Oh, he has not the slightest idea that he is committing a crime! What! He would be horrified, if anyone were to call his attention to it. ‘I, a crime? Go on! How you exaggerate!’ But where is the exaggeration, by God? Reason it out for yourself as I do! You take a man and make him enter a cage, into which a tiger is to be driven, and you say to him: ‘Keep calm, now. Take a careful aim, and fire. Oh, and remember to bring it down with your first shot, see that you hit it in the right spot; otherwise, even if you wound it, it will spring upon you and tear you in pieces!’ All this, I know, if they choose a calm, cool man, a skilled marksman, is nothing, it is not a crime. But if they deliberately choose a man like myself? Think of it, a man like myself! Go and tell him: he will be amazed: ‘What! Ferro? Why, I chose him on purpose because I know how brave he is!’ There is the treachery! There is where the crime lurks: in that ‘knowing how brave I am’! In taking advantage of my courage, of my sense of honour, you follow me? He knows quite well that courage is not what is required! He pretends to think that it is! There is the crime! And go and ask him why, at the same time, he is secretly at work trying to pave the way for a friend of his who would like to get back the woman, the woman who is at present living with the very man nominated by him to enter the cage. He will be even more amazed! ‘Why, what connexion is there between the two things’? Oh, but really, he suspects this as well, does he? What an ex-ag-ge-ra-tion!’ Why, you yourself said that I exaggerated…. But think it over carefully; penetrate to the root of the matter; you will discover what he himself refuses to see, hiding beneath that artificial show of reason; tear off is gloves, and you will find that the gentleman’s hands are red with blood!”

I myself too had often thought, that each of us–however honest and upright he may esteem himself, considering his own actions in the abstract, that is to say apart from the incidents and coincidences that give them their weight and value–may commit a crime ‘in secret even from himself’, that I was stupefied to hear my own thought expressed to me with such clearness, such debating force, and, moreover, by a man whom until then I had regarded as narrow-minded and of a vulgar spirit.

I was, nevertheless, perfectly convinced that Polacco was not acting ‘really’ with any consciousness of committing a crime, nor was he favouring Nuti for the purpose that Carlo Ferro suspected. But it might also, this purpose, be included ‘without his knowledge’, as well in the selection of Ferro to kill the tiger as in the facilitation of Nuti’s coming: actions that only in appearance and in his eyes were unconnected. Certainly, since he could not ‘in any other way’ rid himself of the Nestoroff, the idea that she might once more become the mistress of Nuti, his friend, might be one of his secret aspirations, a desire that was not however apparent. As the mistress of one of his friends, the Nestoroff would no longer be such an enemy; not only that, but perhaps also Nuti, having secured what he wanted, and being as rich as he was, would refuse to allow the Nestoroff to remain an actress, and would take her away with him.

“But you,” I said, “have still time, my’dear Ferro, if you think…”

“No, Sir!” he interrupted me sharply. “This Signor Nuti, by Polacco’s handiwork, has already bought the right to join the Kosmograph.”

“No, excuse me; what I mean is, you have still time to refuse the part that has been given you. No one who knows you can think that you are doing so from fear.”

“They would all think it!” cried Carlo Ferro. “And I should be the first! Yes, Sir… because courage I can and do have, in front of a man, but in front of a wild beast, if I have not calm I cannot have courage; the man who does not feel calm must feel afraid. And I should feel afraid, yes Sir! Afraid not for myself, you understand! Afraid for the people who care for me. I have insisted that my mother should receive an insurance policy; but if to-morrow they give her a wad of paper money stained with blood, my mother will die! What do you expect her to do with the money? You see the shame that conjurer has brought on me! The shame of saying these things, which appear to be dictated by a tremendous, preposterously exaggerated fear! Yes, because everything that I do, and feel, and say is bound to strike everyone as exaggerated. Good God, they have shot ever so many wild beasts in every cinematograph company, and no actor has ever been killed, no actor has ever taken the thing so seriously. But I take it seriously, because here, at this moment, I see myself played with, I see myself trapped, deliberately selected with the sole object of making me lose my calm! I am certain that nothing is going to happen; that it will all be over in a moment and that I shall kill the tiger without the slightest danger to myself. But I am furious at the trap that has been set for me, in the hope that some accident will happen to me, for which Signor Nuti, there you have it, will be waiting ready to step in, with the way clear before him. That… that… is what I… I…”

He broke off abruptly; clenched his fists together and wrung his hands, grinding his teeth. In a flash of inspiration, I realised that the man was torn by all the furies of jealousy. So that was why he had shouted after me! That was why he had spoken at such length! That was why he was in such a state!

And so Carlo Ferro is not sure of the Nestoroff. I scanned him by the light of one of the infrequent street-lamps: his face was distorted, his eyes glared savagely.

“My dear Ferro,” I assured him cordially, “if you think that I can be of use to you in any way, to the best of my ability…”

“Thanks!” he replied coldly. “No… it’s not possible… ‘you’ can’t…”

Perhaps he meant to say at first: “You are of no use to me!” He managed to restrain himself, and went on:

“You can help me only in one way: by telling this Signor Polacco that I am not a man to be played with, because whether it is my life or the lady, I am not the sort of man to let myself be robbed of either of them as easily as he seems to think! That you can tell him! And that if anything should happen here–as it certainly will–it will be the worse for him: take the word of Carlo Ferro! Tell him this, and I am your grateful servant.”

Barely indicating a contemptuous farewell with a wave of his hand, he lengthened his pace and left me.

And his offer of friendship?

How glad I was of this unexpected relapse into contempt! Carlo Ferro may think for a moment that he is my friend; he cannot feel any friendship for me. And certainly, to-morrow, he will hate me all the more, for having treated me this evening as a friend.

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (21)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shoot!

William Shakespeare

(1564-1616)

THE SONNETS

Sonnet 132

Thine eyes I love, and they as pitying me,

Knowing thy heart torment me with disdain,

Have put on black, and loving mourners be,

Looking with pretty ruth upon my pain.

And truly not the morning sun of heaven

Better becomes the grey cheeks of the east,

Nor that full star that ushers in the even

Doth half that glory to the sober west

As those two mourning eyes become thy face:

O let it then as well beseem thy heart

To mourn for me since mourning doth thee grace,

And suit thy pity like in every part.

Then will I swear beauty herself is black,

And all they foul that thy complexion lack.

![]()

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shakespeare Sonnets

An eine Landschaft

Verliere dein Geheimnis nicht vor mir,

Ich bitte dich, verbirg mir deine Reize,

Und wenn ich sehnlich nach Erkenntnis geize,

So schweige sphinxhaft meiner Wissbegier.

Erkennen heisst, ich hab’ es längst erkannt,

Die Welt in seine armen Grenzen pferchen;

Du lehre mich aus deinen hundert Lerchen,

Dass deine Schönheit kein Verstand umspannt.

Christian Morgenstern

(1871-1914)

Hans Hermans photos – Natuurdagboek 02-12

Gedicht Christian Morgenstern

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive M-N, Christian Morgenstern, Expressionism, Hans Hermans Photos, Morgenstern, Christian

Heinrich von Kleist

(1777-1811)

Das letzte Lied

Fernab am Horizont, auf Felsenrissen,

Liegt der gewitterschwarze Krieg getürmt;

Die Blitze zucken schon, die Ungewissen,

Der Wandrer sucht das Laubdach, das ihn schirmt;

Und wie ein Strom, geschwellt von Regengüssen,

Aus seines Ufers Bette heulend stürmt,

Kommt das Verderben mit entbundnen Wogen

Auf alles, was besteht, herangezogen.

Der alten Staaten graues Prachtgerüste

Sinkt donnernd ein, von ihm hinweggespült,

Wie auf der Heide Grund ein Wurmgeniste,

Von einem Knaben scharrend weggewühlt;

Und wo das Leben um der Menschen Brüste

In tausend Lichtern jauchzend hat gespielt,

Ist es so lautlos jetzt wie in den Reichen,

Durch die die Wellen des Cocytus schleichen.

Und ein Geschlecht, von düsterm Haar umflogen,

Tritt aus der Nacht, das keinen Namen führt,

Das, wie ein Hirngespinst der Mythologen,

Hervor aus der Erschlagnen Knochen stiert;

Das ist geboren nicht und nicht erzogen

Vom alten, das im deutschen Land regiert:

Das läßt in Tönen, wie der Nord an Strömen,

Wenn er im Schilfrohr seufzet, sich vernehmen.

Und du, o Lied voll unnennbarer Wonnen,

Das das Gefühl so wunderbar erhebt,

Das, einer Himmelsurne wie entronnen,

Zu den entzückten Ohren niederschwebt,

Bei dessen Klang empor ins Reich der Sonnen,

Von allen Banden frei, die Seele strebt:

Dich trifft der Todespfeil; die Parzen winken,

Und stumm ins Grab mußt du daniedersinken.

Ein Götterkind, bekränzt im Jugendreigen,

Wirst du nicht mehr von Land zu Lande ziehn,

Nicht mehr in unsre Tänze niedersteigen,

Nicht hochrot mehr bei unserm Mahl erglühn.

Und nur wo einsam unter Tannenzweigen

Zu Leichensteinen stille Pfade fliehn,

Wird Wanderern, die bei den Toten leben,

Ein Schatten deiner Schön’ entgegenschweben.

Und stärker rauscht der Sänger in die Saiten,

Der Töne ganze Macht lockt er hervor,

Er singt die Lust, fürs Vaterland zu streiten,

Und machtlos schlägt sein Ruf an jedes Ohr,

Und wie er flatternd das Panier der Zeiten

Sich näher pflanzen sieht, von Tor zu Tor,

Schließt er sein Lied; er wünscht mit ihm zu enden

Und legt die Leier tränend aus den Händen.

Heinrich von Kleist poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Heinrich von Kleist, Kleist, Heinrich von

Amputeer acrobaten.

Henk & Ingrid

http://www.henkeningrid.org/

More in: MUSEUM OF PUBLIC PROTEST, The talk of the town

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature