Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Jack l’Égareur

À Denise

Dans les trémies du ciel

un archange nage, comme il sied, vers une usine.

Faux-monnayeurs que faites-vous de mes ongles ?

J’ai lu dans le journal un roman dont j’étais le héros

toujours à l’aise quand il fait pluie.

Mon cœur bat l’extinction des feux,

Mes yeux sont la nuit.

Je veille mes lendemains avec anxiété.

Au bout d’un an et deux jours…

alors il se fit une journée de pluie et les sept phares merveilleux

du monde…

Escadres souterraines ne vous approchez pas de mon tombeau :

Je suis employé à déclouer les vieux cercueils

pour répartir équitablement les ossements

entre les anciennes sépultures

et les neuves.

Quelle profession ? Profession de foi tu ne figures pas au Bottin.

Les photographes rougiraient si vous les regardiez en pleurant.

Je suis un mort de fraîche date.

Si vous rencontrez un corbillard déchaussez-vous,

Cela fera du bien au mort.

Il se lèvera,

il se sortira,

il chantera,

il chantera la chanson des quadrilles

et dans le futur on verra les nouveau-nés arriver au monde

escortés de squelettes.

Ce ne seront partout que grossesses de géantes,

Il sera de bon ton chez les élégantes

de faire monter en bague

les larmes solides des morts à l’occasion des naissances.

Amour haut parleur, sirène à corps d’oiseau,

je vous quitte.

Je vais goûter le silence cette belle algue où dorment les requins.

Robert Desnos (1900 – 1945)

Jack l’Égareur

À Denise

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Desnos, Robert, Surrealism

Onlangs verscheen de dichtbundel Gedichten van Paul Bezembinder, bij Uitg. Pittige Pixels Amsterdam, 2018, Eerste druk, 104 pag., ISBN 978-90-829774-0-0.

Bezembinder (1961) studeerde theoretische natuurkunde in Nijmegen. In zijn poëzie zoekt hij in vooral klassieke versvormen en thema’s naar de balans tussen serieuze poëzie, pastiche en smartlap.

Bezembinder (1961) studeerde theoretische natuurkunde in Nijmegen. In zijn poëzie zoekt hij in vooral klassieke versvormen en thema’s naar de balans tussen serieuze poëzie, pastiche en smartlap.

Zijn gedichten (Nederlands) en vertalingen (Russisch – Nederlands) verschenen in verschillende (online) literaire tijdschriften, waaronder in het bijzonder op fleursdumal.nl. De bundel Gedichten is zijn tweede bundel.

Bezembinders eerste bundel, Kwatrijnen. Filosofische Verkenningen, verscheen in de reeks digitale publicaties van fleursdumal.nl: Fantom Ebooks.

De reeks is een uitgave van Art Brut Digital Editions, die onregelmatig bijzondere kunst- en literatuurprojecten publiceert. Deze bundel is als pdf op de site van fleursdumal.nl te vinden.

Meer voorbeelden van Bezembinders werk zijn te vinden op de website van de auteur, paulbezembinder.nl

Paul Bezembinder

Kwatrijnen

Uitgeverij. Pittige Pixels Amsterdam,

2018 Eerste druk,

104 pag.,

ISBN 978-90-829774-0-0

De bundel is per e-mail te bestellen.

Prijs: €17.50.

www.paulbezembinder.nl

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, - Book News, Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Art & Literature News, Bezembinder, Paul, PRESS & PUBLISHING

Because I could not

stop for Death

Because I could not stop for Death –

He kindly stopped for me –

The Carriage held but just Ourselves –

And Immortality.

We slowly drove – He knew no haste

And I had put away

My labor and my leisure too,

For His Civility –

We passed the School, where Children strove

At Recess – in the Ring –

We passed the Fields of Gazing Grain –

We passed the Setting Sun –

Or rather – He passed Us –

The Dews drew quivering and Chill –

For only Gossamer, my Gown –

My Tippet – only Tulle –

We paused before a House that seemed

A Swelling of the Ground –

The Roof was scarcely visible –

The Cornice – in the Ground –

Since then – ’tis Centuries – and yet

Feels shorter than the Day

I first surmised the Horses’ Heads

Were toward Eternity –

Emily Dickinson

(1830-1886)

Because I could not stop for Death

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Archive E-F, Dickinson, Emily

Je ne crois plus

aux mots des poème

Je ne crois plus aux mots des poèmes,

car ils ne soulèvent rien

et ne font rien.

Autrefois il y avait des poèmes

qui envoyaient un guerrier

se faire trouer la gueule,

mais la gueule trouée

le guerrier était mort,

et que lui restait-il de sa gloire à lui ?

Je veux dire de son transport ?

Rien.

Il était mort,

cela servait à éduquer dans les classes

les cons et les fils de cons qui viendraient

après lui et sont allés à de nouvelles guerres

atomiquement réglementées,

je crois qu’il y a un état où le guerrier

la gueule trouée

et mort, reste là

il continue à se battre

et à avancer,

il n’est pas mort,

il avance pour l’éternité.

Mais qui en voudrait

sauf moi ?

Et moi, qu’il vienne celui

qui me trouera la gueule

je l’attends.

Antonin Artaud

(1896 — 1948)

Je ne crois plus aux mots des poème

Poème

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Antonin Artaud, Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Artaud, Antonin

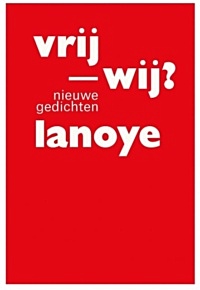

Het thema van de Poëzieweek 2019 is Vrijheid, met als motto: Zonder handen, zonder tanden.

De week opent op donderdag 31 januari met Gedichtendag en wordt woensdagavond 6 februari feestelijk afgesloten met De Grote Poëzieprijs, de Awater Poëzieprijs en de Turing Gedichtenwedstrijd. Tom Lanoye schrijft het Poëziegeschenk Vrij – Wij?, cadeau van de boekwinkel bij aankoop van € 12,50 aan poëzie.

Met Gedichtendag (31 januari 2019) gaat op de laatste donderdag van januari traditiegetrouw de Poëzieweek van start. Gedichtendag, sinds 2000 georganiseerd door Poetry International Rotterdam, is hét poëziefeest van Nederland en Vlaanderen.

Poëzieliefhebbers in Nederland en Vlaanderen organiseren die dag een grote diversiteit aan eigen poëzieactiviteiten en ook de media klinken die dag een stuk poëtischer.

Poëzieliefhebbers in Nederland en Vlaanderen organiseren die dag een grote diversiteit aan eigen poëzieactiviteiten en ook de media klinken die dag een stuk poëtischer.

Voor de enorme hoeveelheid optredens, publicaties, poëzieprijzen, -programma’s en -activiteiten is één dag simpelweg veel te kort!

De Poëzieweek wil een zo groot mogelijk bereik voor poëzie creëren en bundelt tal van activiteiten van organisatoren in Nederland en Vlaanderen.

De Poëzieweek is een samenwerking van Stichting CPNB, Poëziecentrum, Stichting Poetry International, Vlaams Fonds voor de Letteren, Nederlands Letterenfonds, Stichting Lezen Nederland, Iedereen Leest Vlaanderen, De Schrijverscentrale, Boek.be, Taalunie, Stichting Van Beuningen/Peterich-fonds, Turing Foundation, Awater, Het Literatuurhuis, Poëzieclub, SLAG, School der Poëzie en De Nieuwe Oost | Wintertuin.

# Voor een overzicht van alle activiteiten zie de website POËZIEWEEK

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #Archive A-Z Sound Poetry, #Archive Concrete & Visual Poetry, #More Poetry Archives, *War Poetry Archive, - Book Lovers, - Bookstores, Art & Literature News, LIGHT VERSE, Literary Events, MODERN POETRY, Poetry International, Poetry Slam, Poëziepaleis, Poëzieweek, STREET POETRY, THEATRE, Tilt Festival Tilburg, Tom Lanoye

THE LYNCHING OF JUBE BENSON

Gordon Fairfax’s library held but three men, but the air was dense with clouds of smoke. The talk had drifted from one topic to another much as the smoke wreaths had puffed, floated, and thinned away. Then Handon Gay, who was an ambitious young reporter, spoke of a lynching story in a recent magazine, and the matter of punishment without trial put new life into the conversation.

“I should like to see a real lynching,” said Gay rather callously.

“I should like to see a real lynching,” said Gay rather callously.

“Well, I should hardly express it that way,” said Fairfax, “but if a real, live lynching were to come my way, I should not avoid it.”

“I should,” spoke the other from the depths of his chair, where he had been puffing in moody silence. Judged by his hair, which was freely sprinkled with gray, the speaker might have been a man of forty-five or fifty, but his face, though lined and serious, was youthful, the face of a man hardly past thirty.

“What, you, Dr. Melville? Why, I thought that you physicians wouldn’t weaken at anything.”

“I have seen one such affair,” said the doctor gravely, “in fact, I took a prominent part in it.”

“Tell us about it,” said the reporter, feeling for his pencil and notebook, which he was, nevertheless, careful to hide from the speaker.

The men drew their chairs eagerly up to the doctor’s, but for a minute he did not seem to see them, but sat gazing abstractedly into the fire, then he took a long draw upon his cigar and began:

“I can see it all very vividly now. It was in the summer time and about seven years ago. I was practising at the time down in the little town of Bradford. It was a small and primitive place, just the location for an impecunious medical man, recently out of college.

“In lieu of a regular office, I attended to business in the first of two rooms which I rented from Hiram Daly, one of the more prosperous of the townsmen. Here I boarded and here also came my patients—white and black—whites from every section, and blacks from ‘nigger town,’ as the west portion of the place was called.

“The people about me were most of them coarse and rough, but they were simple and generous, and as time passed on I had about abandoned my intention of seeking distinction in wider fields and determined to settle into the place of a modest country doctor. This was rather a strange conclusion for a young man to arrive at, and I will not deny that the presence in the house of my host’s beautiful young daughter, Annie, had something to do with my decision. She was a beautiful young girl of seventeen or eighteen, and very far superior to her surroundings. She had a native grace and a pleasing way about her that made everybody that came under her spell her abject slave. White and black who knew her loved her, and none, I thought, more deeply and respectfully than Jube Benson, the black man of all work about the place.

“He was a fellow whom everybody trusted; an apparently steady-going, grinning sort, as we used to call him. Well, he was completely under Miss Annie’s thumb, and would fetch and carry for her like a faithful dog. As soon as he saw that I began to care for Annie, and anybody could see that, he transferred some of his allegiance to me and became my faithful servitor also. Never did a man have a more devoted adherent in his wooing than did I, and many a one of Annie’s tasks which he volunteered to do gave her an extra hour with me. You can imagine that I liked the boy and you need not wonder any more that as both wooing and my practice waxed apace, I was content to give up my great ambitions and stay just where I was.

“It wasn’t a very pleasant thing, then, to have an epidemic of typhoid break out in the town that kept me going so that I hardly had time for the courting that a fellow wants to carry on with his sweetheart while he is still young enough to call her his girl. I fumed, but duty was duty, and I kept to my work night and day. It was now that Jube proved how invaluable he was as a coadjutor. He not only took messages to Annie, but brought sometimes little ones from her to me, and he would tell me little secret things that he had overheard her say that made me throb with joy and swear at him for repeating his mistress’ conversation. But best of all, Jube was a perfect Cerberus, and no one on earth could have been more effective in keeping away or deluding the other young fellows who visited the Dalys. He would tell me of it afterwards, chuckling softly to himself. ‘An,’ Doctah, I say to Mistah Hemp Stevens, “‘Scuse us, Mistah Stevens, but Miss Annie, she des gone out,” an’ den he go outer de gate lookin’ moughty lonesome. When Sam Elkins come, I say, “Sh, Mistah Elkins, Miss Annie, she done tuk down,” an’ he say, “What, Jube, you don’ reckon hit de——” Den he stop an’ look skeert, an’ I say, “I feared hit is, Mistah Elkins,” an’ sheks my haid ez solemn. He goes outer de gate lookin’ lak his bes’ frien’ done daid, an’ all de time Miss Annie behine de cu’tain ovah de po’ch des’ a laffin’ fit to kill.’

“Jube was a most admirable liar, but what could I do? He knew that I was a young fool of a hypocrite, and when I would rebuke him for these deceptions, he would give way and roll on the floor in an excess of delighted laughter until from very contagion I had to join him—and, well, there was no need of my preaching when there had been no beginning to his repentance and when there must ensue a continuance of his wrong-doing.

“This thing went on for over three months, and then, pouf! I was down like a shot. My patients were nearly all up, but the reaction from overwork made me an easy victim of the lurking germs. Then Jube loomed up as a nurse. He put everyone else aside, and with the doctor, a friend of mine from a neighbouring town, took entire charge of me. Even Annie herself was put aside, and I was cared for as tenderly as a baby. Tom, that was my physician and friend, told me all about it afterward with tears in his eyes. Only he was a big, blunt man and his expressions did not convey all that he meant. He told me how my nigger had nursed me as if I were a sick kitten and he my mother. Of how fiercely he guarded his right to be the sole one to ‘do’ for me, as he called it, and how, when the crisis came, he hovered, weeping, but hopeful, at my bedside, until it was safely passed, when they drove him, weak and exhausted, from the room. As for me, I knew little about it at the time, and cared less. I was too busy in my fight with death. To my chimerical vision there was only a black but gentle demon that came and went, alternating with a white fairy, who would insist on coming in on her head, growing larger and larger and then dissolving. But the pathos and devotion in the story lost nothing in my blunt friend’s telling.

“It was during the period of a long convalescence, however, that I came to know my humble ally as he really was, devoted to the point of abjectness. There were times when for very shame at his goodness to me, I would beg him to go away, to do something else. He would go, but before I had time to realise that I was not being ministered to, he would be back at my side, grinning and pottering just the same. He manufactured duties for the joy of performing them. He pretended to see desires in me that I never had, because he liked to pander to them, and when I became entirely exasperated, and ripped out a good round oath, he chuckled with the remark, ‘Dah, now, you sholy is gittin’ well. Nevah did hyeah a man anywhaih nigh Jo’dan’s sho’ cuss lak dat.’

“Why, I grew to love him, love him, oh, yes, I loved him as well—oh, what am I saying? All human love and gratitude are damned poor things; excuse me, gentlemen, this isn’t a pleasant story. The truth is usually a nasty thing to stand.

“It was not six months after that that my friendship to Jube, which he had been at such great pains to win, was put to too severe a test.

“It was in the summer time again, and as business was slack, I had ridden over to see my friend, Dr. Tom. I had spent a good part of the day there, and it was past four o’clock when I rode leisurely into Bradford. I was in a particularly joyous mood and no premonition of the impending catastrophe oppressed me. No sense of sorrow, present or to come, forced itself upon me, even when I saw men hurrying through the almost deserted streets. When I got within sight of my home and saw a crowd surrounding it, I was only interested sufficiently to spur my horse into a jog trot, which brought me up to the throng, when something in the sullen, settled horror in the men’s faces gave me a sudden, sick thrill. They whispered a word to me, and without a thought, save for Annie, the girl who had been so surely growing into my heart, I leaped from the saddle and tore my way through the people to the house.

“It was Annie, poor girl, bruised and bleeding, her face and dress torn from struggling. They were gathered round her with white faces, and, oh, with what terrible patience they were trying to gain from her fluttering lips the name of her murderer. They made way for me and I knelt at her side. She was beyond my skill, and my will merged with theirs. One thought was in our minds.

“‘Who?’ I asked.

“Her eyes half opened, ‘That black——’ She fell back into my arms dead.

“We turned and looked at each other. The mother had broken down and was weeping, but the face of the father was like iron.

“‘It is enough,’ he said; ‘Jube has disappeared.’ He went to the door and said to the expectant crowd, ‘She is dead.’

“I heard the angry roar without swelling up like the noise of a flood, and then I heard the sudden movement of many feet as the men separated into searching parties, and laying the dead girl back upon her couch, I took my rifle and went out to join them.

“As if by intuition the knowledge had passed among the men that Jube Benson had disappeared, and he, by common consent, was to be the object of our search. Fully a dozen of the citizens had seen him hastening toward the woods and noted his skulking air, but as he had grinned in his old good-natured way they had, at the time, thought nothing of it. Now, however, the diabolical reason of his slyness was apparent. He had been shrewd enough to disarm suspicion, and by now was far away. Even Mrs. Daly, who was visiting with a neighbour, had seen him stepping out by a back way, and had said with a laugh, ‘I reckon that black rascal’s a-running off somewhere.’ Oh, if she had only known.

“‘To the woods! To the woods!’ that was the cry, and away we went, each with the determination not to shoot, but to bring the culprit alive into town, and then to deal with him as his crime deserved.

“I cannot describe the feelings I experienced as I went out that night to beat the woods for this human tiger. My heart smouldered within me like a coal, and I went forward under the impulse of a will that was half my own, half some more malignant power’s. My throat throbbed drily, but water nor whiskey would not have quenched my thirst. The thought has come to me since that now I could interpret the panther’s desire for blood and sympathise with it, but then I thought nothing. I simply went forward, and watched, watched with burning eyes for a familiar form that I had looked for as often before with such different emotions.

“Luck or ill-luck, which you will, was with our party, and just as dawn was graying the sky, we came upon our quarry crouched in the corner of a fence. It was only half light, and we might have passed, but my eyes had caught sight of him, and I raised the cry. We levelled our guns and he rose and came toward us.

“‘I t’ought you wa’n’t gwine see me,’ he said sullenly, ‘I didn’t mean no harm.’

“‘Harm!’

“Some of the men took the word up with oaths, others were ominously silent.

“We gathered around him like hungry beasts, and I began to see terror dawning in his eyes. He turned to me, ‘I’s moughty glad you’s hyeah, doc,’ he said, ‘you ain’t gwine let ’em whup me.’

“‘Whip you, you hound,’ I said, ‘I’m going to see you hanged,’ and in the excess of my passion I struck him full on the mouth. He made a motion as if to resent the blow against even such great odds, but controlled himself.

“‘W’y, doctah,’ he exclaimed in the saddest voice I have ever heard, ‘w’y, doctah! I ain’t stole nuffin’ o’ yo’n, an’ I was comin’ back. I only run off to see my gal, Lucy, ovah to de Centah.’

“‘You lie!’ I said, and my hands were busy helping the others bind him upon a horse. Why did I do it? I don’t know. A false education, I reckon, one false from the beginning. I saw his black face glooming there in the half light, and I could only think of him as a monster. It’s tradition. At first I was told that the black man would catch me, and when I got over that, they taught me that the devil was black, and when I had recovered from the sickness of that belief, here were Jube and his fellows with faces of menacing blackness. There was only one conclusion: This black man stood for all the powers of evil, the result of whose machinations had been gathering in my mind from childhood up. But this has nothing to do with what happened.

“After firing a few shots to announce our capture, we rode back into town with Jube. The ingathering parties from all directions met us as we made our way up to the house. All was very quiet and orderly. There was no doubt that it was as the papers would have said, a gathering of the best citizens. It was a gathering of stern, determined men, bent on a terrible vengeance.

“We took Jube into the house, into the room where the corpse lay. At sight of it, he gave a scream like an animal’s and his face went the colour of storm-blown water. This was enough to condemn him. We divined, rather than heard, his cry of ‘Miss Ann, Miss Ann, oh, my God, doc, you don’t t’ink I done it?’

“Hungry hands were ready. We hurried him out into the yard. A rope was ready. A tree was at hand. Well, that part was the least of it, save that Hiram Daly stepped aside to let me be the first to pull upon the rope. It was lax at first. Then it tightened, and I felt the quivering soft weight resist my muscles. Other hands joined, and Jube swung off his feet.

“No one was masked. We knew each other. Not even the Culprit’s face was covered, and the last I remember of him as he went into the air was a look of sad reproach that will remain with me until I meet him face to face again.

“We were tying the end of the rope to a tree, where the dead man might hang as a warning to his fellows, when a terrible cry chilled us to the marrow.

“‘Cut ‘im down, cut ‘im down, he ain’t guilty. We got de one. Cut him down, fu’ Gawd’s sake. Here’s de man, we foun’ him hidin’ in de barn!’

“Jube’s brother, Ben, and another Negro, came rushing toward us, half dragging, half carrying a miserable-looking wretch between them. Someone cut the rope and Jube dropped lifeless to the ground.

“‘Oh, my Gawd, he’s daid, he’s daid!’ wailed the brother, but with blazing eyes he brought his captive into the centre of the group, and we saw in the full light the scratched face of Tom Skinner—the worst white ruffian in the town—but the face we saw was not as we were accustomed to see it, merely smeared with dirt. It was blackened to imitate a Negro’s.

“God forgive me; I could not wait to try to resuscitate Jube. I knew he was already past help, so I rushed into the house and to the dead girl’s side. In the excitement they had not yet washed or laid her out. Carefully, carefully, I searched underneath her broken finger nails. There was skin there. I took it out, the little curled pieces, and went with it to my office.

“There, determinedly, I examined it under a powerful glass, and read my own doom. It was the skin of a white man, and in it were embedded strands of short, brown hair or beard.

“How I went out to tell the waiting crowd I do not know, for something kept crying in my ears, ‘Blood guilty! Blood guilty!’

“The men went away stricken into silence and awe. The new prisoner attempted neither denial nor plea. When they were gone I would have helped Ben carry his brother in, but he waved me away fiercely, ‘You he’ped murder my brothah, you dat was his frien’, go ‘way, go ‘way! I’ll tek him home myse’f’ I could only respect his wish, and he and his comrade took up the dead man and between them bore him up the street on which the sun was now shining full.

“I saw the few men who had not skulked indoors uncover as they passed, and I—I—stood there between the two murdered ones, while all the while something in my ears kept crying, ‘Blood guilty! Blood guilty!'”

The doctor’s head dropped into his hands and he sat for some time in silence, which was broken by neither of the men, then he rose, saying, “Gentlemen, that was my last lynching.”

Paul Laurence Dunbar

(1872 – 1906)

The Lynching Of Jube Benson

From The Heart Of Happy Hollow, a collection of short stories reprinted in 1904 by Dodd, Mead and Company, New York.

Short Story

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Archive C-D, Dunbar, Paul Laurence, Dunbar, Paul Laurence, Paul Laurence Dunbar, Paul Laurence Dunbar

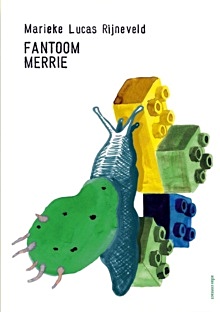

Op 24 januari 2019 verscheen ‘Fantoommerrie’ de nieuwe dichtbundel van Marieke Lucas Rijneveld, een van de grootste nieuwe talenten van de Nederlandse letteren.

Je zou kunnen zeggen dat deze bundel verder gaat waar haar vorige bundel,‘Kalfsvlies’, was opgehouden, maar dat suggereert dat we met een vervolg te maken hebben, en dat is niet zo.

Je zou kunnen zeggen dat deze bundel verder gaat waar haar vorige bundel,‘Kalfsvlies’, was opgehouden, maar dat suggereert dat we met een vervolg te maken hebben, en dat is niet zo.

Deze bundel is een nieuwe verkenning in het universum van Rijneveld, dat paradoxaal genoeg aan de ene kant compleet onnavolgbaar is, maar aan de andere kant ook onmiddellijk herkenbaar en altijd eigen. Over een oma die onsterfelijk had moeten zijn, het noodlottig einde van een onvoorzichtige kat, over dromen natuurlijk: mooie en lelijke, over bidden om speelgoed, de zithouding van de schrijver – en over voorleesvaders, die lastige vragen krijgen: ‘waar komen kinderen vandaan als ouders nooit kussen?

‘Fantoommerrie’ is een dichtbundel om in te verdwalen, en dan te besluiten om er te blijven.

Marieke Lucas Rijneveld

Fantoommerrie

Gedichten

Gepubliceerd 24 januari 2019

Uitgeverij Atlas Contact

Pagina’s 64

Type Paperback / softback

ISBN 9789025453459

€ 19,99

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Archive Q-R, Archive Q-R, Art & Literature News, Marieke Lucas Rijneveld, Rijneveld, Marieke Lucas

Kun jij goed schrijven? Ben jij creatief met woorden en heb je gevoel voor dichten, rappen of songteksten schrijven? Doe dan gauw mee met de dichtwedstrijd Doe Maar Dicht Maar. De honderd beste gedichten winnen een plekje in een mooie dichtbundel!

De deadline van de editie Doe Maar Dicht Maar 2018-2019 is 5 februari 2019. Stuur nu maximaal 3 gedichten in via het wedstrijdformulier. Vanzelfsprekend schrijf jij deze gedichten zelf; plagiaat is verboden! Omdat er duizenden gedichten worden ingestuurd, krijgen alleen de honderd winnaars begin mei 2019 bericht. De uitslag komt half mei op de website te staan.

Wanneer mag je meedoen?

– Je bent 12 t/m 18 jaar;

– Je spreekt en schrijft Nederlands;

– Je zit op het VMBO/ Havo/ VWO/ ROC of MBO;

– Je zit op de eerste t/m de derde graad van het secundair onderwijs in België.

Wat kun je winnen?

Wat kun je winnen?

Van de duizenden inzendingen worden 100 gedichten gekozen die een plekje in de dichtbundel Doe Maar Dicht Maar 2018 krijgen.

De tien allerbeste dichters, vijf winnaars uit de leeftijdscategorie 12 t/m 14 jaar en vijf winnaars uit de leeftijdscategorie 15 t/m 18 jaar, krijgen een uniek cadeau met hun gedicht erop. De winnaars uit deze categorieën, gekozen door de jury, winnen een hoofdprijs!

Bovendien organiseert Het Poëziepaleis ieder jaar de dichtwedstrijd Kinderen & Poëzie voor basisschoolleerlingen uit groep 3 t/m 8. Alle kinderen van 6 t/m 12 jaar uit Nederland en België mogen meedoen.

Bovendien organiseert Het Poëziepaleis ieder jaar de dichtwedstrijd Kinderen & Poëzie voor basisschoolleerlingen uit groep 3 t/m 8. Alle kinderen van 6 t/m 12 jaar uit Nederland en België mogen meedoen.

Schrijf een gedicht over wat jij leuk, spannend, mooi of grappig vindt. Het gedicht mag rijmen, maar dat hoeft zeker niet. Je kunt dichten over jezelf, gebeurtenissen, dromen, verzinsels, mensen, dieren, gevoelens… je kunt het zo gek niet bedenken! Alles mag, zolang het gedicht maar door jou is verzonnen en geschreven.

# meer informtie op website Poëziepaleis

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #More Poetry Archives, Art & Literature News, Children's Poetry, Kinderstadsdichters / Children City Poets, MODERN POETRY, Poëziepaleis

Ich

Du steht! Du steht!

Und ich

Und ich

Ich winge

Raumlos zeitlos wäglos!

Du steht! Du steht!

Und

Rasen bäret mich

Ich

Bär mich selber!

Du!

Du!

Du bannt die Zeit

Du bogt der Kreis

Du seelt der Geist

Du blickt der Blick

Du

Kreist die Welt

Die Welt

Welt!

Ich

Kreis das All!

Und du

Und du

Du

Stehst

Das Ich

Das

Ich!

August Stramm

(1874-1915)

Ich, 1914

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: *War Poetry Archive, Archive S-T, Expressionism, Stramm, August

Het was Frans-Joseph die de nieuwe tijd naar het dorp had gehaald, toen hij het gezellenhuis had laten bouwen. Jonggezellen op kamertjes hadden meisjes nodig. Een van de kasteleins was op die behoefte ingesprongen, had rode lampen voor het raam gezet en meisjes uit de stad laten komen.

Frans-Joseph dacht als een grootindustrieel. Hij was ook de man die het grote flatgebouw had laten bouwen, net niet zo hoog als de silo. Zestig woningen in vier lagen, niet ver van de fabriek. Flats voor buitenlandse gezinnen met veel kinderen die later, naar hij dacht, vanzelf in de fabriek zouden gaan werken. Maar daar had hij zich in misrekend. Met de fabriek liep het mis toen de kinderen groot waren. Bovendien wilden de zonen van de gastarbeiders geen werkezels zijn zoals hun vaders.

Frans-Joseph dacht als een grootindustrieel. Hij was ook de man die het grote flatgebouw had laten bouwen, net niet zo hoog als de silo. Zestig woningen in vier lagen, niet ver van de fabriek. Flats voor buitenlandse gezinnen met veel kinderen die later, naar hij dacht, vanzelf in de fabriek zouden gaan werken. Maar daar had hij zich in misrekend. Met de fabriek liep het mis toen de kinderen groot waren. Bovendien wilden de zonen van de gastarbeiders geen werkezels zijn zoals hun vaders.

Mels rommelt wat in de paperassen. Vraagt zich af of hij al de kladjes en volgeschreven vellen toch nog kan ordenen tot een boek. Een exemplaar voor zichzelf. Na zijn dood kan dat naar het archief van de gemeente.

Hij heeft moeite om het verhaal rond te maken. Hij zit met te veel losse stukjes. Van de arbeidersfamilies die in de jaren zeventig naar het dorp kwamen, weet hij maar weinig. In de flats is hij nooit geweest.

Vanaf de dag dat de fabriek gesloten is en de arbeiders uit de uitgewoonde flatwoningen zijn vertrokken, op zoek naar werk elders of door verhuizing naar de nieuwe wijken in het dorp, staat de flat erbij als een blind bakbeest. Kapotgegooide ruiten. Uitgebroken sponningen. Graffiti, waaruit nog steeds de haat van de nieuwkomers tegen de oorspronkelijke dorpsbevolking af te lezen is. En omgekeerd. Het heeft nooit geboterd tussen de flatbewoners en de dorpelingen.

Er zijn nog een paar flats bewoond. Enkele weduwvrouwen die nergens naartoe kunnen en een halfdemente man die wacht op een plaats in een inrichting. En mevrouw Lecoeur, de hoerenmadam, die er, samen met een paar jongere vrouwen, mannen ontvangt. Iedereen spreekt er schande van. Niemand doet er wat aan. Mels weet niet wat hij van haar moet denken. In het café, waar ze elke ochtend komt en koffie met cognac drinkt, praat hij wel eens met haar. Ze is innemend. Als ze over de mannen praat die haar meisjes bezoeken, is het net alsof ze het over haar jongens heeft. In haar ogen zijn mannen kinderen die beschermd en getroost moeten worden.

Hij doet de mappen dicht, trekt zijn jas aan, slaat de plaid over zijn benen, rolt naar de lift en gaat naar beneden.

Hij weet dat Lizet in de keuken is en luistert. Het blijft stil. Ze negeert hem.

Hij opent de deur en rijdt naar buiten.

Even stopt hij bij de marktkramen die ze aan het opbouwen zijn. Eén middag in de week is er markt. Een kraam met groenten en fruit, een kaaswagen, een viskar, een poelier met roze kippen en konijnen, een broodjesbar, een Turkse kraam met olijven, dadels en paprika’s.

Bij de bakkerskraam koopt hij krentenbollen. Met de zak broodjes op schoot rijdt hij de straat uit.

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (088)

wordt vervolgd

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

A Flower

Given to My Daughter

Frail the white rose and frail are

Her hands that gave

Whose soul is sere and paler

Than time’s wan wave.

Rosefrail and fair — yet frailest

A wonder wild

In gentle eyes thou veilest,

My blueveined child.

James Joyce

(1882-1941)

A Flower Given to My Daughter

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive I-J, Archive I-J, Joyce, James, Joyce, James

I Would I Were a Careless Child

I would I were a careless child,

Still dwelling in my Highland cave,

Or roaming through the dusky wild,

Or bounding o’er the dark blue wave;

The cumbrous pomp of Saxon pride

Accords not with the freeborn soul,

Which loves the mountain’s craggy side,

And seeks the rocks where billows roll.

Fortune! take back these cultured lands,

Take back this name of splendid sound!

I hate the touch of servile hands,

I hate the slaves that cringe around.

Place me among the rocks I love,

Which sound to Ocean’s wildest roar;

I ask but this – again to rove

Through scenes my youth hath known before.

Few are my years, and yet I feel

The world was ne’er designed for me:

Ah! why do dark’ning shades conceal

The hour when man must cease to be?

Once I beheld a splendid dream,

A visionary scene of bliss:

Truth! – wherefore did thy hated beam

Awake me to a world like this?

I loves – but those I love are gone;

Had friends – my early friends are fled:

How cheerless feels the heart alone,

When all its former hopes are dead!

Though gay companions o’er the bowl

Dispel awhile the sense of ill’

Though pleasure stirs the maddening soul,

The heart – the heart – is lonely still.

How dull! to hear the voice of those

Whom rank or chance, whom wealth or power,

Have made, though neither friends nor foes,

Associates of the festive hour.

Give me again a faithful few,

In years and feelings still the same,

And I will fly the midnight crew,

Where boist’rous joy is but a name.

And woman, lovely woman! thou,

My hope, my comforter, my all!

How cold must be my bosom now,

When e’en thy smiles begin to pall!

Without a sigh would I resign

This busy scene of splendid woe,

To make that calm contentment mine,

Which virtue know, or seems to know.

Fain would I fly the haunts of men –

I seek to shun, not hate mankind;

My breast requires the sullen glen,

Whose gloom may suit a darken’d mind.

Oh! that to me the wings were given

Which bear the turtle to her nest!

Then would I cleave the vault of heaven,

To flee away, and be at rest.

George Gordon Byron

(1788 – 1824)

I Would I Were a Careless Child

(Poem)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Byron, Lord

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature