Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Kunstenaar JCJ van der Heyden (83) overleden

Beeldend kunstenaar JCJ van der Heyden, ook wel JCJ Vanderheyden genoemd, is op maandag 27 februari 2012, op 83-jarige leeftijd, in zijn woonplaats Den Bosch overleden. Van der Heyden was de eerste Nederlandse kunstenaar die met nieuwe media werkte. Hij werd onder meer bekend met zijn experimenten met kopieermachines. Vorig jaar wijdde het Museum Boijmans van Beuningen in Rotterdam nog een tentoonstelling aan zijn werk.

JCJ Van der Heyden studeerde aan de kunstacademies in Den Bosch en Maastricht. Hij schilderde abstracte schilderijen maar hield zich ook bezig met fotografie, film en het maken van installaties. Van der Heyden experimenteerde met rechthoekige vormen en maakte schilderijen naar aanleiding van foto’s die hij uit het raam nam als hij met een vliegtuig onderweg was.

Van der Heyden heeft in veel belangrijke musea geëxposeerd. Vorig jaar werden nog twee van zijn werken gestolen uit Galerie 68 in Den Bosch.

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Exhibition Archive, In Memoriam

Royal de Luxe

Het bezoek dat de sultan der Indiën op zijn

olifant die door de tijd kan reizen in juli 2006

aan Antwerpen bracht indachtig

Niet uit het oosten weggebleven

passeert mij langzaam dreunend

een olifant van rubber, staal en tover.

Wat mij betreft blijft deze langskomst

immer duren maar daar gaat hij al.

Hoe je deel van sprookjes uit kunt

maken. Het benoemen van de onderdelen

waaruit dit monter wonder bestaat

is hoogverraad. Door merg en been

zijn twaalf meter hoge vreugdeschal.

En dan, dan krijg ik tranen in de ogen

omdat ik wil geloven in de wimpers

van het meisje dat gemaakt van kostbaar

hout is, dat slechts bestaat bij gratie

van een reuzenfantasie. Het ziet mij aan

met quasi echte sympathie en schrijdt

vervolgens zonderlinge uren tegemoet.

Wie haar aanschouwden wensen zich

aan deze aanblik vast te klampen.

Eeuwig delen wij gekwetste liefde.

O lieve dode schone, keer behouden

weer, behouden

Bert Bevers

Verschenen in Stroom, Antwerpen, nummer 22, herfst 2006

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Bevers, Bert

Ton van Reen

vanaf de toren

Vanaf de toren

is de Maas een worm

met schubben

op het lijf

en de paarden

in de wei

zijn op hol geslagen mieren

uit dikke korrels zand

die de houten deuren

uit huizen vreten

Uit: Ton van Reen, Blijvend vers, Verzamelde gedichten (1965-2007). Uitgeverij De Contrabas, 2011, ISBN 9789079432462, 144 pagina’s, paperback

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

Het VUmc is niet veilig meer

Een paar jaar geleden was ik bij de diploma-uitreiking van een van m’n neefjes die afstudeerde aan een medische faculteit. Ik raakte onder de indruk van de ceremonie en van de ernst waarmee deze universiteit de jonge doktoren op de rails zette, aan de start van een medische carrière. Ze moesten een eed afleggen waarvan ik me ‘ik zal geheim houden wat mij is toevertrouwd en ik ken mijn verantwoordelijkheid voor de samenleving’ nog goed herinner. Sinds kort weet ik dat deze houding niet door alle medici gedeeld wordt, dat er ook universiteiten zijn waar men deze verantwoordelijkheid aan de laars lapt, dat er een universitair medisch centrum is waar de privacy van een patiënt niet veilig is, waar je in je ellende gevolgd kunt worden door zoemende camera’s, waar maatschappelijke verantwoordelijkheid betekent dat profilering en voldoen aan de sensatiegeilheid van de verzamelde Henk en Ingrids belangrijker wordt gevonden dan het fysieke en psychische welzijn van de patiënt. Als gevolg van alle commotie is de TV serie inmiddels stopgezet en heeft de voorzitter van de Raad van Bestuur van het VUmc spijt betuigt, er waren toch wel wat klachten binnengekomen en de protocollen zijn niet altijd goed gevolgd. Geen woord over het overtreden van beroepsgeheim en het schofferen van de privacy van de patiënten. De man doet me denken aan de wielrenner die spijt betuigt over zijn dopinggebruik maar die in wezen alleen spijt heeft dat hij betrapt is.

Melseke

(in het VUmc zijn patiënten op de eerste hulp gevolgd en gefilmd door een team dat niet gebonden was aan een beroepsgeheim en zonder voorafgaande toestemming door de patiënt)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Melseke, Columns, The talk of the town

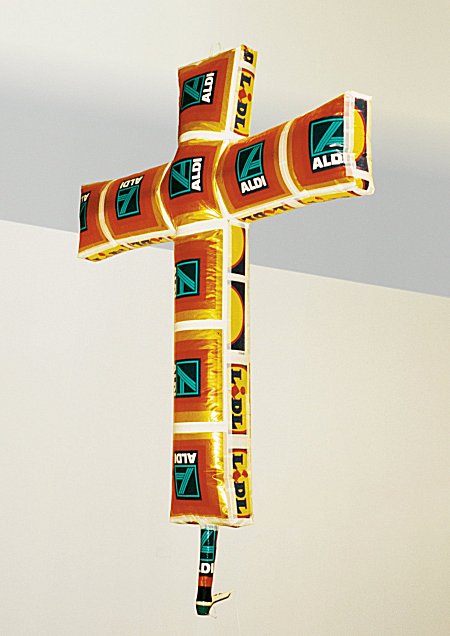

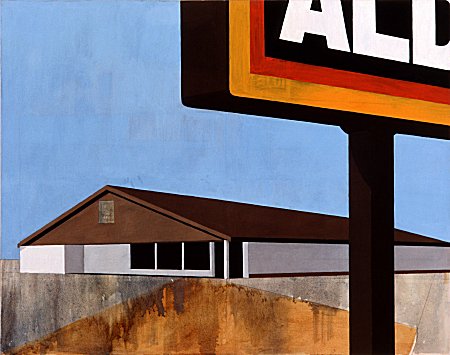

Wilhelm Hack Museum Ludwigshafen

I love ALDI

bis 04.03.2012

Das Prinzip ALDI ist eines der erfolgreichsten Geschäftsmodelle in Deutschland. Das Versprechen lautet »hohe Qualität, niedriger Preis«. Eingelöst werden kann dieses Versprechen nur über ein konsequentes Verfolgen des Discount-Prinzips: Masse bzw. Menge (im Ein- und Verkauf!) als oberstes Gebot; danach ist das wichtigste Prinzip Verzicht: Verzicht auf Zwischenhändler, auf aufwändige Markenwerbung, auf schillernde Wareninszenierungen, auf großes Sortiment. Längst ist das Phänomen ALDI ein gesellschaftliches Thema geworden. Es geht dabei nicht um die Marke ALDI, sondern um das System, das in dieser Marke Kultstatus erreicht hat. Nicht nur in Arbeiterstädten wie Ludwigshafen hat die »Aldisierung« als Gegenmodell zum Luxus-Markenfetischismus alle Einkommens- und Bildungsschichten erreicht und mit dem Billig-Virus infiziert. Das Wilhelm-Hack-Museum widmet sich nun erstmals konsequent dem Thema »Discount« und »billig«. Unter dem Titel »I love ALDI« reflektieren 38 Künstlerinnen und Künstler teils unmittelbar, teils im weiteren Sinne Fragen der industriellen Lebensmittelproduktion, der Billigware und des postmodernen Konsumverhaltens. In fünf Kapiteln (Verpackung,

Inhalt, Konsum, Kunst, Gesellschaft) entfaltet sich ein vielfältiger Ausstellungs-Parcours: Ästhetische Fragen zum Erscheinungsbild der Discounter wie Architektur, Warenpräsentation, Verpackungs- und Logo-Design sind ebenso Thema wie gesellschaftskritische Aspekte bei Joseph Beuys und dessen Schüler Felix Droese. Große, eigens für die Ausstellung geschaffene Installationen von Thomas Rentmeister und Alice Musiol werfen Fragen nach unserem Umgang mit Lebensmitteln auf. Arbeiten wie der Kunstautomat von Baumann/Bien, die (käuflichen!) Discount-Bilder von Hötsch Höhle wie auch die gesamte Aldi-Kunstedition von 2003 agieren auf der Grenzlinie zwischen Kunst und Massenware. Eine kleine Sonderpräsentation zeigt einen Ausschnitt aus Elke Koskas legendärer (Plastik-)Tütenschau, die 1982 im Düsseldorfer Kunstverein präsentiert wurde. Das umfangreiche Begleitprogramm behandelt weitere Aspekte in Podiumsgesprächen und Workshops mit Lebensmittel- und Design-Experten.

Künstlerinnen und Künstler: Peter Anton, Winfried Baumann/Anna Bien, Günther Beier, Joseph Beuys, Tatjana Doll, Felix Droese, Gardar Eide Einarsson, Robert Filiou, Lili Fischer, Sebastian Freytag, Günther Fruhtrunk, Heinrich Gartentor, Torben Giehler, Joachim Grommek, Thomas Henke, Hötsch Höhle, Christian Jankowski, Gabriele Langendorf, Jani Leinonen, Alexander Kosolapov, M+M, Guido Münch, Alice Musiol, Birgit Nadrau, Katinka Pilscheur, Thomas Rentmeister, Pietro Sanguineti, Stefanie Schneider, Angelika Schröder, Stephanie Senge, Francisco Sierra, Florian Slotawa, Daniel Spoerri, Piero Steinle, Markus Vater, Konstantin Voit, Ina Weber, Iskender Yediler.

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Exhibition Archive, Galerie Deutschland

foto joep eijkens

Esther Porcelijn

In Breda en in Tilburg

Ik woonde in een ansichtkaart

Breda is één groot vroeger

Een raam op zolder starend naar

De kerk en alle kroegen;

Waar mensen feestend zweterig

Zich door de biertjes zwoegen.

Omlijst is elk klein detail

De hofjes en de muren

Van baksteen staat elk huis zo lang

Dat al eeuwenoude uren

Mensen turend hun gedachten

Op de stad afvuren.

Toch lijken de inwoners

De schoonheid niet te delen

Ze ogen rijk en carnaval

Religie gaat vervelen;

Het boordje is geruild voor polo

‘t Verstikt nog steeds hun kelen.

Hen lijkt de vreemdheid ongehoord

Ze houden niet van anders

Geen polo: is te stumperig

En de rest, de omstanders?

Zij drinken er lustig op los

En dansen hun polonaise om de bijstanders.

Nu ik verhuis naar een andere stad

Waar oude muren zeldzaam

En hofjes onbestaand

Kijk ik door mijn nieuwe raam:

Een plein met auto’s en bomen

Vroeger heeft hier een andere naam.

De mensen, echter, zijn zélf anders

Sferen van raarheid, hun gelaat

Is minder strak hooghartig

Rokerige dronkenmanspraat,

Tijdens lange cafénachten,

Dragen ze als een sieraad.

Ik woonde in een ansichtkaart

Waar ik de schoonheid had

De nieuwe plaats is anders, ja,

Maar vrolijk en minder glad

Bij dat besef verscheur ik mijn post

Een ansichtkaart is toch maar plat.

Esther Porcelijn is stadsdichter van Tilburg

Kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: City Poets / Stadsdichters, Porcelijn, Esther, Porcelijn, Esther

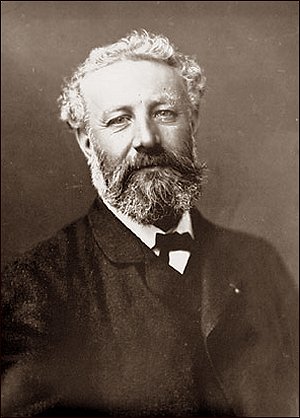

Jules Verne

(1828-1905)

Le génie

(Sonnet)

Comme un pur stalactite, oeuvre de la nature,

Le génie incompris apparaît à nos yeux.

Il est là, dans l’endroit où l’ont placé les Cieux,

Et d’eux seuls, il reçoit sa vie et sa structure.

Jamais la main de l’homme assez audacieuse

Ne le pourra créer, car son essence est pure,

Et le Dieu tout-puissant le fit à sa figure ;

Le mortel pauvre et laid, pourrait-il faire mieux ?

Il ne se taille pas, ce diamant byzarre,

Et de quelques couleurs dont l’azur le chamarre,

Qu’il reste tel qu’il est, que le fit l’éternel !

Si l’on veut corriger le brillant stalactite,

Ce n’est plus aussitôt qu’un caillou sans mérite,

Qui ne réfléchit plus les étoiles du ciel.

Jules Verne poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive U-V

E.E. Cummings

(1894 – 1962)

nobody loses all the time

nobody loses all the time

i had an uncle named

Sol who was a born failure and

nearly everybody said he should have gone

into vaudeville perhaps because my Uncle Sol could

sing McCann He Was A Diver on Xmas Eve like Hell Itself which

may or may not account for the fact that my Uncle

Sol indulged in that possibly most inexcusable

of all to use a highfalootin phrase

luxuries that is or to

wit farming and be

it needlessly

added

my Uncle Sol’s farm

failed because the chickens

ate the vegetables so

my Uncle Sol had a

chicken farm till the

skunks ate the chickens when

my Uncle Sol

had a skunk farm but

the skunks caught cold and

died so

my Uncle Sol imitated the

skunks in a subtle manner

or by drowning himself in the watertank

but somebody who’d given my Unde Sol a Victor

Victrola and records while he lived presented to

him upon the auspicious occasion of his decease a

scrumptious not to mention splendiferous funeral with

tall boys in black gloves and flowers and everything and

i remember we all cried like the Missouri

when my Uncle Sol’s coffin lurched because

somebody pressed a button

(and down went

my Uncle

Sol

and started a worm farm)

Edward Estlin Cummings

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive C-D

William Shakespeare

(1564-1616)

THE SONNETS

117

Accuse me thus, that I have scanted all,

Wherein I should your great deserts repay,

Forgot upon your dearest love to call,

Whereto all bonds do tie me day by day,

That I have frequent been with unknown minds,

And given to time your own dear-purchased right,

That I have hoisted sail to all the winds

Which should transport me farthest from your sight.

Book both my wilfulness and errors down,

And on just proof surmise, accumulate,

Bring me within the level of your frown,

But shoot not at me in your wakened hate:

Since my appeal says I did strive to prove

The constancy and virtue of your love.

![]()

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shakespeare Sonnets

Schrijver Ton van Reen

opent Bibliotheek Maasbree

Op zondag 26 februari a.s. opent de geheel vernieuwde Bibliotheek Maasbree haar deuren. De opening vindt plaats om 13.00 uur en wordt verricht door de auteur Ton van Reen. Speciaal voor deze gelegenheid heeft de Bibliotheek Maasbree een boekje van Ton van Reen uitgegeven met de titel “Een nog schonere schijn van witheid; Een winterverhaal”. Delen van deze tekst zijn straks in het interieur van de bibliotheek terug te vinden.

De Bibliotheek Maasbree maakt momenteel een ingrijpende ontwikkeling door. In juli 2011 al werden de openingstijden uitgebreid met een extra avondopenstelling op de maandag. Tevens werd toen een inloopspreekuur voor Poolse arbeidsmigranten ingesteld. Dat de bibliotheek hiermee in een grote behoefte voorziet is wel gebleken op een willekeurige maandagavond in augustus toen de bibliotheek tussen 18.00 uur en 20.00 uur door 240 mensen bezocht werd.

Daarna werd gestart met cursussen Nederlands voor Poolse migranten. Inmiddels worden er drie parallelle cursussen gegeven op dinsdag, woensdag en donderdag. Een vierde cursus start binnenkort op de zaterdagmiddagen. Daarnaast is een cursus Pools voor Nederlandse ondernemers in voorbereiding. Inmiddels is de bibliotheek ook van WiFi voorzien en verder is er een PC met Pools toetsenbord en de Poolse versie van het Office-pakket beschikbaar. De Poolse afdeling is in december officieel met een groots feest geopend.

Vanaf 1 januari is de Bibliotheek Maasbree nu ook op zondagen geopend. De bibliotheek gaat open om 10.30 uur en sluit om 14.00 uur. Deze uitbreiding is mogelijk geworden door de ingebruikname van zelfservice-apparatuur en de inzet van een Poolstalige medewerker. Hierdoor kunnen ook op zondagen extra diensten aan de Poolse migranten verleend worden. De Bibliotheek Maasbree is, buiten de bibliotheken van Maastricht, Heerlen en Roermond, overigens de enige Limburgse bibliotheek die op zondagen is geopend.

De inventaris van de bibliotheek was inmiddels al zo’n vijftig jaar oud en voldeed niet meer aan de eisen die aan de inrichting van een eigentijdse bibliotheek mogen worden gesteld. De nieuwe inrichting biedt veel mogelijkheden om de boeken frontaal te presenteren. Hierbij wordt gebruik gemaakt van principes uit de retail. De nieuwe opstelling nodigt uit tot snuffelen, tot ontdekken en tot verrast worden door de vele rijkdommen die de bibliotheek te bieden heeft.

Iedereen is van harte uitgenodigd om op zondag 26 februari om 13.00 uur aanwezig te zijn. Het boekje van Ton van Reen is door alle inwoners van Maasbree gratis af te halen bij de bibliotheek.

Volwassenen die nog geen lid van de bibliotheek zijn, maar dat willen worden, ontvangen ook nog eens het boek “Over geluk” van Twan Huys.

Speciaal voor de jeugd wordt er op zondag 11 maart om 13.30 uur in de bibliotheek een voorstelling geven door de Boxmeerse jeugdboekenauteur Gerard Sonnemans. Tijdens deze voorstelling staan de Middeleeuwse ridders en monniken centraal. De toegang is gratis.

fotojefvankempen

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Reen, Ton van, Ton van Reen

James Joyce

(1882-1941)

A Painful Case

Mr. James Duffy lived in Chapelizod because he wished to live as far as possible from the city of which he was a citizen and because he found all the other suburbs of Dublin mean, modern and pretentious. He lived in an old sombre house and from his windows he could look into the disused distillery or upwards along the shallow river on which Dublin is built. The lofty walls of his uncarpeted room were free from pictures. He had himself bought every article of furniture in the room: a black iron bedstead, an iron washstand, four cane chairs, a clothes-rack, a coal-scuttle, a fender and irons and a square table on which lay a double desk. A bookcase had been made in an alcove by means of shelves of white wood. The bed was clothed with white bedclothes and a black and scarlet rug covered the foot. A little hand-mirror hung above the washstand and during the day a white-shaded lamp stood as the sole ornament of the mantelpiece. The books on the white wooden shelves were arranged from below upwards according to bulk. A complete Wordsworth stood at one end of the lowest shelf and a copy of the Maynooth Catechism, sewn into the cloth cover of a notebook, stood at one end of the top shelf. Writing materials were always on the desk. In the desk lay a manuscript translation of Hauptmann’s Michael Kramer, the stage directions of which were written in purple ink, and a little sheaf of papers held together by a brass pin. In these sheets a sentence was inscribed from time to time and, in an ironical moment, the headline of an advertisement for Bile Beans had been pasted on to the first sheet. On lifting the lid of the desk a faint fragrance escaped, the fragrance of new cedarwood pencils or of a bottle of gum or of an overripe apple which might have been left there and forgotten.

Mr. Duffy abhorred anything which betokened physical or mental disorder. A medival doctor would have called him saturnine. His face, which carried the entire tale of his years, was of the brown tint of Dublin streets. On his long and rather large head grew dry black hair and a tawny moustache did not quite cover an unamiable mouth. His cheekbones also gave his face a harsh character; but there was no harshness in the eyes which, looking at the world from under their tawny eyebrows, gave the impression of a man ever alert to greet a redeeming instinct in others but often disappointed. He lived at a little distance from his body, regarding his own acts with doubtful side-glasses. He had an odd autobiographical habit which led him to compose in his mind from time to time a short sentence about himself containing a subject in the third person and a predicate in the past tense. He never gave alms to beggars and walked firmly, carrying a stout hazel.

He had been for many years cashier of a private bank in Baggot Street. Every morning he came in from Chapelizod by tram. At midday he went to Dan Burke’s and took his lunch, a bottle of lager beer and a small trayful of arrowroot biscuits. At four o’clock he was set free. He dined in an eating-house in George’s Street where he felt himself safe from the society of Dublin’s gilded youth and where there was a certain plain honesty in the bill of fare. His evenings were spent either before his landlady’s piano or roaming about the outskirts of the city. His liking for Mozart’s music brought him sometimes to an opera or a concert: these were the only dissipations of his life.

He had neither companions nor friends, church nor creed. He lived his spiritual life without any communion with others, visiting his relatives at Christmas and escorting them to the cemetery when they died. He performed these two social duties for old dignity’s sake but conceded nothing further to the conventions which regulate the civic life. He allowed himself to think that in certain circumstances he would rob his hank but, as these circumstances never arose, his life rolled out evenly, an adventureless tale.

One evening he found himself sitting beside two ladies in the Rotunda. The house, thinly peopled and silent, gave distressing prophecy of failure. The lady who sat next him looked round at the deserted house once or twice and then said:

“What a pity there is such a poor house tonight! It’s so hard on people to have to sing to empty benches.”

He took the remark as an invitation to talk. He was surprised that she seemed so little awkward. While they talked he tried to fix her permanently in his memory. When he learned that the young girl beside her was her daughter he judged her to be a year or so younger than himself. Her face, which must have been handsome, had remained intelligent. It was an oval face with strongly marked features. The eyes were very dark blue and steady. Their gaze began with a defiant note but was confused by what seemed a deliberate swoon of the pupil into the iris, revealing for an instant a temperament of great sensibility. The pupil reasserted itself quickly, this half-disclosed nature fell again under the reign of prudence, and her astrakhan jacket, moulding a bosom of a certain fullness, struck the note of defiance more definitely.

He met her again a few weeks afterwards at a concert in Earlsfort Terrace and seized the moments when her daughter’s attention was diverted to become intimate. She alluded once or twice to her husband but her tone was not such as to make the allusion a warning. Her name was Mrs. Sinico. Her husband’s great-great-grandfather had come from Leghorn. Her husband was captain of a mercantile boat plying between Dublin and Holland; and they had one child.

Meeting her a third time by accident he found courage to make an appointment. She came. This was the first of many meetings; they met always in the evening and chose the most quiet quarters for their walks together. Mr. Duffy, however, had a distaste for underhand ways and, finding that they were compelled to meet stealthily, he forced her to ask him to her house. Captain Sinico encouraged his visits, thinking that his daughter’s hand was in question. He had dismissed his wife so sincerely from his gallery of pleasures that he did not suspect that anyone else would take an interest in her. As the husband was often away and the daughter out giving music lessons Mr. Duffy had many opportunities of enjoying the lady’s society. Neither he nor she had had any such adventure before and neither was conscious of any incongruity. Little by little he entangled his thoughts with hers. He lent her books, provided her with ideas, shared his intellectual life with her. She listened to all.

Sometimes in return for his theories she gave out some fact of her own life. With almost maternal solicitude she urged him to let his nature open to the full: she became his confessor. He told her that for some time he had assisted at the meetings of an Irish Socialist Party where he had felt himself a unique figure amidst a score of sober workmen in a garret lit by an inefficient oil-lamp. When the party had divided into three sections, each under its own leader and in its own garret, he had discontinued his attendances. The workmen’s discussions, he said, were too timorous; the interest they took in the question of wages was inordinate. He felt that they were hard-featured realists and that they resented an exactitude which was the produce of a leisure not within their reach. No social revolution, he told her, would be likely to strike Dublin for some centuries.

She asked him why did he not write out his thoughts. For what, he asked her, with careful scorn. To compete with phrasemongers, incapable of thinking consecutively for sixty seconds? To submit himself to the criticisms of an obtuse middle class which entrusted its morality to policemen and its fine arts to impresarios?

He went often to her little cottage outside Dublin; often they spent their evenings alone. Little by little, as their thoughts entangled, they spoke of subjects less remote. Her companionship was like a warm soil about an exotic. Many times she allowed the dark to fall upon them, refraining from lighting the lamp. The dark discreet room, their isolation, the music that still vibrated in their ears united them. This union exalted him, wore away the rough edges of his character, emotionalised his mental life. Sometimes he caught himself listening to the sound of his own voice. He thought that in her eyes he would ascend to an angelical stature; and, as he attached the fervent nature of his companion more and more closely to him, he heard the strange impersonal voice which he recognised as his own, insisting on the soul’s incurable loneliness. We cannot give ourselves, it said: we are our own. The end of these discourses was that one night during which she had shown every sign of unusual excitement, Mrs. Sinico caught up his hand passionately and pressed it to her cheek.

Mr. Duffy was very much surprised. Her interpretation of his words disillusioned him. He did not visit her for a week, then he wrote to her asking her to meet him. As he did not wish their last interview to be troubled by the influence of their ruined confessional they meet in a little cakeshop near the Parkgate. It was cold autumn weather but in spite of the cold they wandered up and down the roads of the Park for nearly three hours. They agreed to break off their intercourse: every bond, he said, is a bond to sorrow. When they came out of the Park they walked in silence towards the tram; but here she began to tremble so violently that, fearing another collapse on her part, he bade her good-bye quickly and left her. A few days later he received a parcel containing his books and music.

Four years passed. Mr. Duffy returned to his even way of life. His room still bore witness of the orderliness of his mind. Some new pieces of music encumbered the music-stand in the lower room and on his shelves stood two volumes by Nietzsche: Thus Spake Zarathustra and The Gay Science. He wrote seldom in the sheaf of papers which lay in his desk. One of his sentences, written two months after his last interview with Mrs. Sinico, read: Love between man and man is impossible because there must not be sexual intercourse and friendship between man and woman is impossible because there must be sexual intercourse. He kept away from concerts lest he should meet her. His father died; the junior partner of the bank retired. And still every morning he went into the city by tram and every evening walked home from the city after having dined moderately in George’s Street and read the evening paper for dessert.

One evening as he was about to put a morsel of corned beef and cabbage into his mouth his hand stopped. His eyes fixed themselves on a paragraph in the evening paper which he had propped against the water-carafe. He replaced the morsel of food on his plate and read the paragraph attentively. Then he drank a glass of water, pushed his plate to one side, doubled the paper down before him between his elbows and read the paragraph over and over again. The cabbage began to deposit a cold white grease on his plate. The girl came over to him to ask was his dinner not properly cooked. He said it was very good and ate a few mouthfuls of it with difficulty. Then he paid his bill and went out.

He walked along quickly through the November twilight, his stout hazel stick striking the ground regularly, the fringe of the buff Mail peeping out of a side-pocket of his tight reefer overcoat. On the lonely road which leads from the Parkgate to Chapelizod he slackened his pace. His stick struck the ground less emphatically and his breath, issuing irregularly, almost with a sighing sound, condensed in the wintry air. When he reached his house he went up at once to his bedroom and, taking the paper from his pocket, read the paragraph again by the failing light of the window. He read it not aloud, but moving his lips as a priest does when he reads the prayers Secreto. This was the paragraph:

DEATH OF A LADY AT SYDNEY PARADE

A PAINFUL CASE

Today at the City of Dublin Hospital the Deputy Coroner (in the absence of Mr. Leverett) held an inquest on the body of Mrs. Emily Sinico, aged forty-three years, who was killed at Sydney Parade Station yesterday evening. The evidence showed that the deceased lady, while attempting to cross the line, was knocked down by the engine of the ten o’clock slow train from Kingstown, thereby sustaining injuries of the head and right side which led to her death.

James Lennon, driver of the engine, stated that he had been in the employment of the railway company for fifteen years. On hearing the guard’s whistle he set the train in motion and a second or two afterwards brought it to rest in response to loud cries. The train was going slowly.

P. Dunne, railway porter, stated that as the train was about to start he observed a woman attempting to cross the lines. He ran towards her and shouted, but, before he could reach her, she was caught by the buffer of the engine and fell to the ground.

A juror. “You saw the lady fall?”

Witness. “Yes.”

Police Sergeant Croly deposed that when he arrived he found the deceased lying on the platform apparently dead. He had the body taken to the waiting-room pending the arrival of the ambulance.

Constable 57 corroborated.

Dr. Halpin, assistant house surgeon of the City of Dublin Hospital, stated that the deceased had two lower ribs fractured and had sustained severe contusions of the right shoulder. The right side of the head had been injured in the fall. The injuries were not sufficient to have caused death in a normal person. Death, in his opinion, had been probably due to shock and sudden failure of the heart’s action.

Mr. H. B. Patterson Finlay, on behalf of the railway company, expressed his deep regret at the accident. The company had always taken every precaution to prevent people crossing the lines except by the bridges, both by placing notices in every station and by the use of patent spring gates at level crossings. The deceased had been in the habit of crossing the lines late at night from platform to platform and, in view of certain other circumstances of the case, he did not think the railway officials were to blame.

Captain Sinico, of Leoville, Sydney Parade, husband of the deceased, also gave evidence. He stated that the deceased was his wife. He was not in Dublin at the time of the accident as he had arrived only that morning from Rotterdam. They had been married for twenty-two years and had lived happily until about two years ago when his wife began to be rather intemperate in her habits.

Miss Mary Sinico said that of late her mother had been in the habit of going out at night to buy spirits. She, witness, had often tried to reason with her mother and had induced her to join a League. She was not at home until an hour after the accident. The jury returned a verdict in accordance with the medical evidence and exonerated Lennon from all blame.

The Deputy Coroner said it was a most painful case, and expressed great sympathy with Captain Sinico and his daughter. He urged on the railway company to take strong measures to prevent the possibility of similar accidents in the future. No blame attached to anyone.

Mr. Duffy raised his eyes from the paper and gazed out of his window on the cheerless evening landscape. The river lay quiet beside the empty distillery and from time to time a light appeared in some house on the Lucan road. What an end! The whole narrative of her death revolted him and it revolted him to think that he had ever spoken to her of what he held sacred. The threadbare phrases, the inane expressions of sympathy, the cautious words of a reporter won over to conceal the details of a commonplace vulgar death attacked his stomach. Not merely had she degraded herself; she had degraded him. He saw the squalid tract of her vice, miserable and malodorous. His soul’s companion! He thought of the hobbling wretches whom he had seen carrying cans and bottles to be filled by the barman. Just God, what an end! Evidently she had been unfit to live, without any strength of purpose, an easy prey to habits, one of the wrecks on which civilisation has been reared. But that she could have sunk so low! Was it possible he had deceived himself so utterly about her? He remembered her outburst of that night and interpreted it in a harsher sense than he had ever done. He had no difficulty now in approving of the course he had taken.

As the light failed and his memory began to wander he thought her hand touched his. The shock which had first attacked his stomach was now attacking his nerves. He put on his overcoat and hat quickly and went out. The cold air met him on the threshold; it crept into the sleeves of his coat. When he came to the public-house at Chapelizod Bridge he went in and ordered a hot punch.

The proprietor served him obsequiously but did not venture to talk. There were five or six workingmen in the shop discussing the value of a gentleman’s estate in County Kildare They drank at intervals from their huge pint tumblers and smoked, spitting often on the floor and sometimes dragging the sawdust over their spits with their heavy boots. Mr. Duffy sat on his stool and gazed at them, without seeing or hearing them. After a while they went out and he called for another punch. He sat a long time over it. The shop was very quiet. The proprietor sprawled on the counter reading the Herald and yawning. Now and again a tram was heard swishing along the lonely road outside.

As he sat there, living over his life with her and evoking alternately the two images in which he now conceived her, he realised that she was dead, that she had ceased to exist, that she had become a memory. He began to feel ill at ease. He asked himself what else could he have done. He could not have carried on a comedy of deception with her; he could not have lived with her openly. He had done what seemed to him best. How was he to blame? Now that she was gone he understood how lonely her life must have been, sitting night after night alone in that room. His life would be lonely too until he, too, died, ceased to exist, became a memory, if anyone remembered him.

It was after nine o’clock when he left the shop. The night was cold and gloomy. He entered the Park by the first gate and walked along under the gaunt trees. He walked through the bleak alleys where they had walked four years before. She seemed to be near him in the darkness. At moments he seemed to feel her voice touch his ear, her hand touch his. He stood still to listen. Why had he withheld life from her? Why had he sentenced her to death? He felt his moral nature falling to pieces.

When he gained the crest of the Magazine Hill he halted and looked along the river towards Dublin, the lights of which burned redly and hospitably in the cold night. He looked down the slope and, at the base, in the shadow of the wall of the Park, he saw some human figures lying. Those venal and furtive loves filled him with despair. He gnawed the rectitude of his life; he felt that he had been outcast from life’s feast. One human being had seemed to love him and he had denied her life and happiness: he had sentenced her to ignominy, a death of shame. He knew that the prostrate creatures down by the wall were watching him and wished him gone. No one wanted him; he was outcast from life’s feast. He turned his eyes to the grey gleaming river, winding along towards Dublin. Beyond the river he saw a goods train winding out of Kingsbridge Station, like a worm with a fiery head winding through the darkness, obstinately and laboriously. It passed slowly out of sight; but still he heard in his ears the laborious drone of the engine reiterating the syllables of her name.

He turned back the way he had come, the rhythm of the engine pounding in his ears. He began to doubt the reality of what memory told him. He halted under a tree and allowed the rhythm to die away. He could not feel her near him in the darkness nor her voice touch his ear. He waited for some minutes listening. He could hear nothing: the night was perfectly silent. He listened again: perfectly silent. He felt that he was alone.

James Joyce: A Painful Case

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive I-J, Joyce, James, Joyce, James

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (7)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926)

The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio,

Cinematograph Operator

by Luigi Pirandello

Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK II

1

Dear house in the country, the ‘Grandparents’, full of the

indescribable fragrance of the oldest family memories, where all the

old-fashioned chairs and tables, vitalised by these memories, were no

longer inanimate objects but, so to speak, intimate parts of the

people who lived in the house, since in them they came in contact

with, became aware of the precious, tranquil, safe reality of their

existence.

There really did linger in those rooms a peculiar aroma, which I seem

to smell now as I write: an aroma of the life of long ago which seemed

to have given a fragrance to all the things that were preserved there.

I see again the drawing-room, a trifle gloomy, it must be admitted,

with its walls stuccoed in rectangular panels which strove to imitate

ancient marbles: red and green alternately; and each panel was set in

a handsome border of its own, of stucco likewise, in a pattern of

foliage; except that in the course of time these imitation marbles had

grown weary of their innocent make-believe, had bulged out a little

here and there, and one saw a few tiny cracks on the surface. All of

which said to me kindly:

“You are poor; the seams of your jacket are rent; but you see that

even in a gentleman’s house…”

Ah, yes! I had only to turn and look at those curious brackets which

seemed to shrink from touching the floor with their gilded spidery

legs. The marble top of each was a trifle yellow, and in the sloping

mirror above were reflected exactly in their immobility the pair of

baskets that stood upon the marble: baskets of fruit, also of marble,

coloured: figs, peaches, limes, corresponding exactly, on either side,

with their reflexions, as though there were four baskets instead of

two.

In that motionless, clear reflexion was embodied all the limpid calm

which reigned in that house. It seemed as though nothing could ever

happen there. This was the message, also, of the little bronze

timepiece between the baskets, only the back of which was to be seen

in the mirror. It represented a fountain, and had a spiral rod of

rock-crystal, which spun round and round with the movement of the

clockwork. How much water had that fountain poured forth? And yet the

little basin beneath it was never full.

Next I see the room from which one goes down to the garden. (From one

room to the other one passes between a pair of low doors, which seem

full of their own importance, and perfectly aware of the treasures

committed to their charge.) This room, leading down to the garden, is

the favourite sitting-room at all times of the year. It has a floor of

large, square tiles of terra-cotta, a trifle worn with use. The

wallpaper, patterned with damask roses, is a trifle faded, as are the

gauze curtains, also patterned with damask roses, screening the

windows and the glass door beyond which one sees the landing of the

little wooden outside stair, and the green railing and the pergola of

the garden bathed in an enchantment of sunshine and stillness.

The light filters green and fervid between the slats of the little

sun-blind outside the window, and does not pour into the room, which

remains in a cool delicious shadow, embalmed with the scents from the

garden.

What bliss, what a bath of purity for the soul, to sit at rest for a

little upon that old sofa with its high back, its cylindrical cushions

of green rep, likewise a trifle discoloured.

“Giorgio! Giorgio!”

Who is calling from the garden? It is Granny Rosa, who cannot succeed

in reaching, even with the end of her cane, the flowers of the

jasmine, now that the plant has grown so big and has climbed right up

high upon the wall.

Granny Rosa does so love those jasmines! She has upstairs, in the

cupboard in the wall of her room, a box full of umbrella-shaped heads

of cummin, dried; she takes one out every morning, before she goes

down to the garden; and, when she has gathered the blossoms with her

cane, she sits down in the shade of the pergola, puts on her

spectacles, and slips the jasmines one by one into the spidery stems

of that umbrella-shaped head, until she has turned it into a lovely

round white rose, with an intense, delicious perfume, which she goes

and places religiously in a little vase on the top of the chest of

drawers in her room, in front of the portrait of her only son, who

died long ago.

It is so intimate and sheltered, this little house, so contented with

the life that it encloses within its walls, without any desire for the

other life that goes noisily on outside, far away. It remains there,

as though perched in a niche behind the green hill, and has not wished

for so much as a glimpse of the sea and the marvellous Bay. It has

chosen to remain apart, unknown to all the world, almost hidden away

in that green, deserted corner, outside and far away from all the

vicissitudes of life.

There was at one time on the gatepost a marble tablet, which bore the

name of the owner: Carlo Mirelli. Grandfather Carlo decided to

remove it, when Death found his way, for the first time, into that

modest little house buried in the country, and carried off with him

the son of the house, barely thirty years old, already the father

himself of two little children.

Did Grandfather Carlo think, perhaps, that when the tablet was removed

from the gatepost, Death would not find his way back to the house

again?

Grandfather Carlo was one of those old men who wore a velvet cap with

a silken tassel, but could read Horace. He knew, therefore, that

death, ‘aequo pede’, knocks at all doors alike, whether or not they

have a name engraved on a tablet.

Were it not that each of us, blinded by what he considers the

injustice of his own lot, feels an unreasoning need to vent the fury

of his own grief upon somebody or something. Grandfather Carlo’s fury,

on that occasion, fell upon the innocent tablet on the gatepost.

If Death allowed us to catch hold of him, I would catch him by the arm

and lead him in front of that mirror where with such limpid precision

are reflected in their immobility the two baskets of fruit and the

back of the bronze timepiece, and would say to him:

“You see? Now be off with you! Everything here must be allowed to

remain as it is!”

But Death does not allow us to catch hold of him.

By taking down that tablet, perhaps Grandfather Carlo meant to imply

that–once his son was dead–there was nobody left alive in the house.

A little later, Death came again.

There was one person left alive who called upon him desperately every

night: the widowed daughter-in-law who, after her husband’s death,

felt as though she were divided from the family, a stranger in the

house.

And so, the two little orphans: Lidia, the elder, who was nearly five,

and Giorgetto who was three, remained in the sole charge of their

grandparents, who were still not so very old.

To start life afresh when one is already beginning to grow feeble, and

to rediscover in oneself all the first amazements of childhood; to

create once again round a pair of rosy children the most innocent

affection, the most pleasant dreams, and to drive away, as being

importunate and tiresome, Experience, who from time to time thrusts in

her head, the face of a withered old woman, to say, blinking behind

her spectacles: “This will happen, that will happen,” when as yet

nothing has ever happened, and it is so delightful that nothing should

have happened; and to act and think and speak as though really one

knew nothing more than is already known to two little children who

know nothing at all: to act as though things were seen not in

retrospect but through the eyes of a person going forwards for the

first time, and for the first time seeing and hearing: this miracle

was performed by Grandfather Carlo and Granny Rosa; they did, that is

to say, for the two little ones, far more than would have been done by

the father and mother, who, if they had lived, young as they both

were, might have wished to enjoy life a little longer themselves. Nor

did their not having anything left to enjoy render the task more easy

for the two old people, for we know that to the old everything is a

heavy burden, when it no longer has any meaning or value for them.

The two grandparents accepted the meaning and value which their two

grandchildren gradually, as they grew older, began to give to things,

and all the world took on the bright colours of youth for them, and

life recaptured the candour and freshness of innocence. But what could

they know of a world so wide, of a life so different from their own,

which was going on outside, far away, those two young creatures born

and brought up in the house in the country? The old people had

forgotten that life and that world, everything had become new again

for them, the sky, the scenery, the song of the birds, the taste of

food. Outside the gate, life existed no longer. Life began there, at

the gate, and gilded afresh everything round about; nor did the old

people imagine that anything could come to them from outside; and even

Death, even Death they had almost forgotten, albeit he had already

come there twice.

Have patience a little while, Death, to whom no house, however remote

and hidden, can remain unknown! But how in the world, starting from

thousands and thousands of miles away, thrust aside, or dragged,

tossed hither and thither by the turmoil of ever so many mysterious

changes of fortune, could there have found her way to that modest

little house, perched in its niche there behind the green hill, a

woman, to whom the peace and the affection that reigned there not only

must have been incomprehensible, must have been not even conceivable?

I have no record, nor perhaps has anyone, of the path followed by this

woman to bring her to the dear house in the country, near Sorrento.

There, at that very spot, before the gatepost, from which Grandfather

Carlo, long ago, had had the tablet removed, she did not arrive of her

own accord; that is certain; she did not raise her hand, uninvited, to

ring the bell, to make them open the gate to her. But not far from

there she stopped to wait for a young man, guarded until then with the

life and soul of two old grandparents, handsome, innocent, ardent, his

soul borne on the wings of dreams, to come out of that gate and

advance confidently towards life.

Oh, Granny Rosa, do you still call to him from the garden, for him to

pull down with your cane your jasmine blossoms?

“Giorgio! Giorgio!”

There still rings in my ears, Granny Rosa, the sound of your voice.

And I feel a bitter delight, which I cannot express in words, in

imagining you as still there, in your little house, which I see again

as though I were there at this moment, and were at this moment

breathing the atmosphere that lingers there of an old-fashioned

existence; in imagining you as knowing nothing of all that has

happened, as you were at first, when I, in the summer holidays, came

out from Sorrento every morning to prepare for the October

examinations your grandson Giorgio, who refused to learn a word of

Latin or Greek, and instead covered every scrap of paper that came

into his hands, the margins of his books, the top of the schoolroom

table, with sketches in pen and pencil, with caricatures. There must

even be one of me, still, on the top of that table, covered all over

with scribblings.

“Ah, Signor Serafino,” you sigh, Granny Rosa, as you hand me in an old

cup the familiar coffee with essence of cinnamon, like the coffee that

our aunts in religion offer us in their convents, “ah, Signor

Serafino, Giorgio has bought a box of paints; he wants to leave us; he

wants to become a painter…”

And over your shoulder opens her sweet, clear, sky-blue eyes and

blushes a deep red Lidiuccia, your granddaughter; Duccella, as you

call her. Why?

Ah, because…. There has come now three times from Naples a young

gentleman, a fine young gentleman all covered with scent, in a velvet

coat, with yellow chamois-leather gloves, an eyeglass in his right eye

and a baron’s coronet on his handkerchief and portfolio. He was sent

by his grandfather, Barone Nuti, a friend of Grandfather Carlo, who

was like a brother to him before Grandfather Carlo, growing weary of

the world, retired from Naples, here, to the Sorrentine villa. You

know this, Granny Rosa. But you do not know that the young gentleman

from Naples is fervently encouraging Giorgio to devote himself to art

and to go off to Naples with him. Duccella knows, because young Aldo

Nuti (how very strange!), when speaking with such fervour of art,

never looks at Giorgio, but looks at her, into her eyes, as though it

were her that he had to encourage, and not Giorgio; yes, yes, her, to

come to Naples to stay there for ever with himself.

So that is why Duccella blushes a deep red, over your shoulder, Granny

Rosa, whenever she hears you say that Giorgio wishes to become a

painter.

He too, the young gentleman from Naples, if his grandfather would

allow him… Not a painter, no… He would like to go upon the stage,

to become an actor. How he would love that! But his grandfather does

not wish it…. Dare we wager, Granny Rosa, that Duccella does not

wish it either?

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (7)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shoot!

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature