Fleurs du Mal Magazine

This is a book of tragicomic gurlesque word-witchery inspired by the Kate Bush cosmos.

Campily glamorous, darkly funny, obsessively ekphrastic, boozily baroque, psychedelically girly & musically ecstatic, 50 Things Kate Bush Taught Me About the Multiverse dazzles as Karyna McGlynn’s third collection of poems.

Campily glamorous, darkly funny, obsessively ekphrastic, boozily baroque, psychedelically girly & musically ecstatic, 50 Things Kate Bush Taught Me About the Multiverse dazzles as Karyna McGlynn’s third collection of poems.

Karyna McGlynn is a writer, professor & collagist living in Memphis. She is the author of I Have to Go Back to 1994 and Kill a Girl (Sarabande 2009) and Hothouse (Sarabande 2017), which was a New York Times Editor’s Choice.

Karyna holds an MFA in Poetry from the University of Michigan, and a PhD in Creative Writing & English Literature from the University of Houston. Recent honors include the Diane Middlebrook Poetry Fellowship at the University of Wisconsin, a visiting professorship at Oberlin College, the Rumi Prize for Poetry selected by Cate Marvin, and the Florida Review Editors’ Award in Fiction. With Erika Jo Brown, she’s co-editing the anthology Clever Girl: Witty Poetry by Women.

50 Things Kate Bush Taught Me About the Multiverse

Karyna McGlynn

Publisher: Sarabande Books

April 26, 2022

Language: English

Paperback: 96 pages

ISBN-10: 194644894X

ISBN-13: 978-1946448941

€ 23,10

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #Editors Choice Archiv, - Book News, Archive M-N, Archive M-N, Kate Bush

A man returns home to the hearts of the great spaces.

He recounts his life, which he burned by both ends and which reveals another History of America. Also, through his own history and his characters, he tells his relationship to the world.

He recounts his life, which he burned by both ends and which reveals another History of America. Also, through his own history and his characters, he tells his relationship to the world.

Through this spiritual and joyful testament, from Livingston MO to Patagonia AZ, he invites you to go back to basics and live in harmony with Nature.

This man is one of the greatest American writers and poets. His name is Jim Harrison.

Jim Harrison was born in 1937 in Grayling, Michigan, USA. He was a writer, poet and producer, known for Wolf (1994), Revenge (1990) and Legends of the Fall (1994). He died in 2016 in Patagonia, Arizona, USA.

‘Seule la terre est éternelle’

Documentary 2019

1h 56m

Directors: François Busnel & Adrien Soland

Writer: François Busnel

Stars: Jim Harrison, Louise Erdrich, Jim Fergus

François Busnel is a writer and producer, known for Seule la terre est éternelle (2019), Les Grands Mythes (2014) and Mythologies (2001).

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Archive G-H, AUDIO, CINEMA, RADIO & TV, Harrison, Jim, Jim Harrison, Western Fiction, Western Non-Fiction

For more than 30 years, S corresponds with her first love, J.

There is one story she does not tell: one about three men and an alley. She learns a new story: one in which she is unable to leave the two blocks surrounding her house, and unable to tell J exactly what happened to her. Isolated by trauma and depression, S finds a way back into her skin through the strangers she meets online for sex.

There is one story she does not tell: one about three men and an alley. She learns a new story: one in which she is unable to leave the two blocks surrounding her house, and unable to tell J exactly what happened to her. Isolated by trauma and depression, S finds a way back into her skin through the strangers she meets online for sex.

The retellings of her adventures titillate J, who urges her on to more encounters. As in the 1001 Nights, this is a story made of stories: S’s own stories are interrupted and overwritten by similar, culturally reified stories. S’s life becomes scenes from everything from The Graduate and The Story of O to the words of Charles Manson and the Bible.

What emerges in words, invocations and collage is a grasping at presence and absence in the age of the internet: to be read in real time is life, and the blank screen is death.

San Francisco-based Performance Poet Daphne Gottlieb stitches together the ivory tower and the gutter just using her tongue. She is the author and editor of 10 books, most recently the short stories “Pretty Much Dead. She is also the author of five books of poetry, two anthologies, and a graphic novel with artist Diane DiMassa. She is also the co-editor (with Lisa Kester) of Dear Dawn: Aileen Wuornos in her Own Words, letters from the “First Female Serial Killer” from Death Row to her childhood best friend.

She is the winner of the Acker Award, the Audre Lorde Award in Poetry, the Firecracker Alternative Book Award, and a five-time finalist for the Lambda Literary Award.

Gottlieb teaches graduate-level creative writing, and has also performed and taught creative writing workshops at all levels around the country. She received her MFA from Mills College.

Saint 1001

by Daphne Gottlieb

Publisher: MadHat Press

2021

Language: English

Paperback: 264 pages

ISBN-10: 1952335256

ISBN-13: 978-1952335259

$21.95

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #Editors Choice Archiv, - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive G-H, Archive G-H

God Sees the Truth, But Waits

by Leo Tolstoy

In the town of Vladimir lived a young merchant named Ivan Dmitrich Aksionov. He had two shops and a house of his own.

Aksionov was a handsome, fair-haired, curly-headed fellow, full of fun, and very fond of singing. When quite a young man he had been given to drink, and was riotous when he had had too much; but after he married he gave up drinking, except now and then.

One summer Aksionov was going to the Nizhny Fair, and as he bade good-bye to his family, his wife said to him, “Ivan Dmitrich, do not start to-day; I have had a bad dream about you.”

Aksionov laughed, and said, “You are afraid that when I get to the fair I shall go on a spree.”

His wife replied: “I do not know what I am afraid of; all I know is that I had a bad dream. I dreamt you returned from the town, and when you took off your cap I saw that your hair was quite grey.”

His wife replied: “I do not know what I am afraid of; all I know is that I had a bad dream. I dreamt you returned from the town, and when you took off your cap I saw that your hair was quite grey.”

Aksionov laughed. “That’s a lucky sign,” said he. “See if I don’t sell out all my goods, and bring you some presents from the fair.”

So he said good-bye to his family, and drove away.

When he had travelled half-way, he met a merchant whom he knew, and they put up at the same inn for the night. They had some tea together, and then went to bed in adjoining rooms.

It was not Aksionov’s habit to sleep late, and, wishing to travel while it was still cool, he aroused his driver before dawn, and told him to put in the horses.

Then he made his way across to the landlord of the inn (who lived in a cottage at the back), paid his bill, and continued his journey.

When he had gone about twenty-five miles, he stopped for the horses to be fed. Aksionov rested awhile in the passage of the inn, then he stepped out into the porch, and, ordering a samovar to be heated, got out his guitar and began to play.

Suddenly a troika drove up with tinkling bells and an official alighted, followed by two soldiers. He came to Aksionov and began to question him, asking him who he was and whence he came. Aksionov answered him fully, and said, “Won’t you have some tea with me?” But the official went on cross-questioning him and asking him. “Where did you spend last night? Were you alone, or with a fellow-merchant? Did you see the other merchant this morning? Why did you leave the inn before dawn?”

Aksionov wondered why he was asked all these questions, but he described all that had happened, and then added, “Why do you cross-question me as if I were a thief or a robber? I am travelling on business of my own, and there is no need to question me.”

Then the official, calling the soldiers, said, “I am the police-officer of this district, and I question you because the merchant with whom you spent last night has been found with his throat cut. We must search your things.”

They entered the house. The soldiers and the police-officer unstrapped Aksionov’s luggage and searched it. Suddenly the officer drew a knife out of a bag, crying, “Whose knife is this?”

Aksionov looked, and seeing a blood-stained knife taken from his bag, he was frightened.

“How is it there is blood on this knife?”

Aksionov tried to answer, but could hardly utter a word, and only stammered: “I–don’t know–not mine.” Then the police-officer said: “This morning the merchant was found in bed with his throat cut. You are the only person who could have done it. The house was locked from inside, and no one else was there. Here is this blood-stained knife in your bag and your face and manner betray you! Tell me how you killed him, and how much money you stole?”

Aksionov swore he had not done it; that he had not seen the merchant after they had had tea together; that he had no money except eight thousand rubles of his own, and that the knife was not his. But his voice was broken, his face pale, and he trembled with fear as though he went guilty.

The police-officer ordered the soldiers to bind Aksionov and to put him in the cart. As they tied his feet together and flung him into the cart, Aksionov crossed himself and wept. His money and goods were taken from him, and he was sent to the nearest town and imprisoned there. Enquiries as to his character were made in Vladimir. The merchants and other inhabitants of that town said that in former days he used to drink and waste his time, but that he was a good man. Then the trial came on: he was charged with murdering a merchant from Ryazan, and robbing him of twenty thousand rubles.

His wife was in despair, and did not know what to believe. Her children were all quite small; one was a baby at her breast. Taking them all with her, she went to the town where her husband was in jail. At first she was not allowed to see him; but after much begging, she obtained permission from the officials, and was taken to him. When she saw her husband in prison-dress and in chains, shut up with thieves and criminals, she fell down, and did not come to her senses for a long time. Then she drew her children to her, and sat down near him. She told him of things at home, and asked about what had happened to him. He told her all, and she asked, “What can we do now?”

“We must petition the Czar not to let an innocent man perish.”

His wife told him that she had sent a petition to the Czar, but it had not been accepted.

Aksionov did not reply, but only looked downcast.

Then his wife said, “It was not for nothing I dreamt your hair had turned grey. You remember? You should not have started that day.” And passing her fingers through his hair, she said: “Vanya dearest, tell your wife the truth; was it not you who did it?”

“So you, too, suspect me!” said Aksionov, and, hiding his face in his hands, he began to weep. Then a soldier came to say that the wife and children must go away; and Aksionov said good-bye to his family for the last time.

When they were gone, Aksionov recalled what had been said, and when he remembered that his wife also had suspected him, he said to himself, “It seems that only God can know the truth; it is to Him alone we must appeal, and from Him alone expect mercy.”

And Aksionov wrote no more petitions; gave up all hope, and only prayed to God.

Aksionov was condemned to be flogged and sent to the mines. So he was flogged with a knot, and when the wounds made by the knot were healed, he was driven to Siberia with other convicts.

For twenty-six years Aksionov lived as a convict in Siberia. His hair turned white as snow, and his beard grew long, thin, and grey. All his mirth went; he stooped; he walked slowly, spoke little, and never laughed, but he often prayed.

In prison Aksionov learnt to make boots, and earned a little money, with which he bought The Lives of the Saints. He read this book when there was light enough in the prison; and on Sundays in the prison-church he read the lessons and sang in the choir; for his voice was still good.

The prison authorities liked Aksionov for his meekness, and his fellow-prisoners respected him: they called him “Grandfather,” and “The Saint.” When they wanted to petition the prison authorities about anything, they always made Aksionov their spokesman, and when there were quarrels among the prisoners they came to him to put things right, and to judge the matter.

No news reached Aksionov from his home, and he did not even know if his wife and children were still alive.

One day a fresh gang of convicts came to the prison. In the evening the old prisoners collected round the new ones and asked them what towns or villages they came from, and what they were sentenced for. Among the rest Aksionov sat down near the newcomers, and listened with downcast air to what was said.

One of the new convicts, a tall, strong man of sixty, with a closely-cropped grey beard, was telling the others what be had been arrested for.

“Well, friends,” he said, “I only took a horse that was tied to a sledge, and I was arrested and accused of stealing. I said I had only taken it to get home quicker, and had then let it go; besides, the driver was a personal friend of mine. So I said, ‘It’s all right.’ ‘No,’ said they, ‘you stole it.’ But how or where I stole it they could not say. I once really did something wrong, and ought by rights to have come here long ago, but that time I was not found out. Now I have been sent here for nothing at all… Eh, but it’s lies I’m telling you; I’ve been to Siberia before, but I did not stay long.”

“Where are you from?” asked some one.

“From Vladimir. My family are of that town. My name is Makar, and they also call me Semyonich.”

Aksionov raised his head and said: “Tell me, Semyonich, do you know anything of the merchants Aksionov of Vladimir? Are they still alive?”

“Know them? Of course I do. The Aksionovs are rich, though their father is in Siberia: a sinner like ourselves, it seems! As for you, Gran’dad, how did you come here?”

Aksionov did not like to speak of his misfortune. He only sighed, and said, “For my sins I have been in prison these twenty-six years.”

“What sins?” asked Makar Semyonich.

But Aksionov only said, “Well, well–I must have deserved it!” He would have said no more, but his companions told the newcomers how Aksionov came to be in Siberia; how some one had killed a merchant, and had put the knife among Aksionov’s things, and Aksionov had been unjustly condemned.

When Makar Semyonich heard this, he looked at Aksionov, slapped his own knee, and exclaimed, “Well, this is wonderful! Really wonderful! But how old you’ve grown, Gran’dad!”

The others asked him why he was so surprised, and where he had seen Aksionov before; but Makar Semyonich did not reply. He only said: “It’s wonderful that we should meet here, lads!”

These words made Aksionov wonder whether this man knew who had killed the merchant; so he said, “Perhaps, Semyonich, you have heard of that affair, or maybe you’ve seen me before?”

“How could I help hearing? The world’s full of rumours. But it’s a long time ago, and I’ve forgotten what I heard.”

“Perhaps you heard who killed the merchant?” asked Aksionov.

Makar Semyonich laughed, and replied: “It must have been him in whose bag the knife was found! If some one else hid the knife there, ‘He’s not a thief till he’s caught,’ as the saying is. How could any one put a knife into your bag while it was under your head? It would surely have woke you up.”

When Aksionov heard these words, he felt sure this was the man who had killed the merchant. He rose and went away. All that night Aksionov lay awake. He felt terribly unhappy, and all sorts of images rose in his mind. There was the image of his wife as she was when he parted from her to go to the fair. He saw her as if she were present; her face and her eyes rose before him; he heard her speak and laugh. Then he saw his children, quite little, as they: were at that time: one with a little cloak on, another at his mother’s breast. And then he remembered himself as he used to be-young and merry. He remembered how he sat playing the guitar in the porch of the inn where he was arrested, and how free from care he had been. He saw, in his mind, the place where he was flogged, the executioner, and the people standing around; the chains, the convicts, all the twenty-six years of his prison life, and his premature old age. The thought of it all made him so wretched that he was ready to kill himself.

“And it’s all that villain’s doing!” thought Aksionov. And his anger was so great against Makar Semyonich that he longed for vengeance, even if he himself should perish for it. He kept repeating prayers all night, but could get no peace. During the day he did not go near Makar Semyonich, nor even look at him.

A fortnight passed in this way. Aksionov could not sleep at night, and was so miserable that he did not know what to do.

One night as he was walking about the prison he noticed some earth that came rolling out from under one of the shelves on which the prisoners slept. He stopped to see what it was. Suddenly Makar Semyonich crept out from under the shelf, and looked up at Aksionov with frightened face. Aksionov tried to pass without looking at him, but Makar seized his hand and told him that he had dug a hole under the wall, getting rid of the earth by putting it into his high-boots, and emptying it out every day on the road when the prisoners were driven to their work.

“Just you keep quiet, old man, and you shall get out too. If you blab, they’ll flog the life out of me, but I will kill you first.”

Aksionov trembled with anger as he looked at his enemy. He drew his hand away, saying, “I have no wish to escape, and you have no need to kill me; you killed me long ago! As to telling of you–I may do so or not, as God shall direct.”

Next day, when the convicts were led out to work, the convoy soldiers noticed that one or other of the prisoners emptied some earth out of his boots. The prison was searched and the tunnel found. The Governor came and questioned all the prisoners to find out who had dug the hole. They all denied any knowledge of it. Those who knew would not betray Makar Semyonich, knowing he would be flogged almost to death. At last the Governor turned to Aksionov whom he knew to be a just man, and said:

“You are a truthful old man; tell me, before God, who dug the hole?”

Makar Semyonich stood as if he were quite unconcerned, looking at the Governor and not so much as glancing at Aksionov. Aksionov’s lips and hands trembled, and for a long time he could not utter a word. He thought, “Why should I screen him who ruined my life? Let him pay for what I have suffered. But if I tell, they will probably flog the life out of him, and maybe I suspect him wrongly. And, after all, what good would it be to me?”

“Well, old man,” repeated the Governor, “tell me the truth: who has been digging under the wall?”

Aksionov glanced at Makar Semyonich, and said, “I cannot say, your honour. It is not God’s will that I should tell! Do what you like with me; I am your hands.”

However much the Governor! tried, Aksionov would say no more, and so the matter had to be left.

That night, when Aksionov was lying on his bed and just beginning to doze, some one came quietly and sat down on his bed. He peered through the darkness and recognised Makar.

“What more do you want of me?” asked Aksionov. “Why have you come here?”

Makar Semyonich was silent. So Aksionov sat up and said, “What do you want? Go away, or I will call the guard!”

Makar Semyonich bent close over Aksionov, and whispered, “Ivan Dmitrich, forgive me!”

“What for?” asked Aksionov.

“It was I who killed the merchant and hid the knife among your things. I meant to kill you too, but I heard a noise outside, so I hid the knife in your bag and escaped out of the window.”

Aksionov was silent, and did not know what to say. Makar Semyonich slid off the bed-shelf and knelt upon the ground. “Ivan Dmitrich,” said he, “forgive me! For the love of God, forgive me! I will confess that it was I who killed the merchant, and you will be released and can go to your home.”

“It is easy for you to talk,” said Aksionov, “but I have suffered for you these twenty-six years. Where could I go to now?… My wife is dead, and my children have forgotten me. I have nowhere to go…”

Makar Semyonich did not rise, but beat his head on the floor. “Ivan Dmitrich, forgive me!” he cried. “When they flogged me with the knot it was not so hard to bear as it is to see you now … yet you had pity on me, and did not tell. For Christ’s sake forgive me, wretch that I am!” And he began to sob.

When Aksionov heard him sobbing he, too, began to weep. “God will forgive you!” said he. “Maybe I am a hundred times worse than you.” And at these words his heart grew light, and the longing for home left him. He no longer had any desire to leave the prison, but only hoped for his last hour to come.

In spite of what Aksionov had said, Makar Semyonich confessed, his guilt. But when the order for his release came, Aksionov was already dead.

Leo Tolstoy (1828-1910) short stories

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #Short Stories Archive, Archive S-T, Archive S-T, Tolstoy, Leo

“When we first met, I was a child, and she had been dead for centuries.”

On discovering her murdered husband’s body, an eighteenth-century Irish noblewoman drinks handfuls of his blood and composes an extraordinary lament. Eibhlín Dubh Ní Chonaill’s poem travels through the centuries, finding its way to a new mother who has narrowly avoided her own fatal tragedy. When she realizes that the literature dedicated to the poem reduces Eibhlín Dubh’s life to flimsy sketches, she wants more: the details of the poet’s girlhood and old age; her unique rages, joys, sorrows, and desires; the shape of her days and site of her final place of rest.

On discovering her murdered husband’s body, an eighteenth-century Irish noblewoman drinks handfuls of his blood and composes an extraordinary lament. Eibhlín Dubh Ní Chonaill’s poem travels through the centuries, finding its way to a new mother who has narrowly avoided her own fatal tragedy. When she realizes that the literature dedicated to the poem reduces Eibhlín Dubh’s life to flimsy sketches, she wants more: the details of the poet’s girlhood and old age; her unique rages, joys, sorrows, and desires; the shape of her days and site of her final place of rest.

What follows is an adventure in which Doireann Ní Ghríofa sets out to discover Eibhlín Dubh’s erased life—and in doing so, discovers her own.

Moving fluidly between past and present, quest and elegy, poetry and those who make it, A Ghost in the Throat is a shapeshifting book: a record of literary obsession; a narrative about the erasure of a people, of a language, of women; a meditation on motherhood and on translation; and an unforgettable story about finding your voice by freeing another’s.

Doireann Ní Ghríofa is a poet and essayist. ‘A Ghost in the Throat’ was awarded the James Tait Black Prize for Biography and was voted Book of the Year at the Irish Book Awards; it has been described as “powerful” (New York Times), “captivatingly original” (The Guardian) and a “masterpiece” (Sunday Business Post). Doireann is also author of six critically-acclaimed books of poetry, each a deepening exploration of birth, death, desire, and domesticity. Awards for her writing include a Lannan Literary Fellowship (USA), the Ostana Prize (Italy), a Seamus Heaney Fellowship (Queen’s University), and the Rooney Prize for Irish Literature, among others.

A Ghost in the Throat

by Doireann Ní Ghríofa (Author)

Publisher: Biblioasis

2021

Language: English

Paperbac : 336 pages

ISBN-10: 1771964111

ISBN-13: 978-1771964111

Paperback

$15.99

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Archive G-H, Archive G-H, Archive M-N, Doireann Ní Ghríofa, Ghríofa, Doireann Ni

Speels, poëtisch en gelaagd. Zo valt het oeuvre te omschrijven van de in Breda geboren kunstenaar Pieter Laurens Mol. De tentoonstelling Nachtvlucht laat een selectie van zijn werk zien vanaf 1965 tot nu.

Voor het eerst in 30 jaar is zo’n groot aantal werken van deze internationaal gerenommeerd kunstenaar tegelijkertijd in één tentoonstelling te zien. Het thema van de tentoonstelling Nachtvlucht is de kleur zwart en de uiteenlopende betekenissen van de duisternis.

Een zonsondergang geschilderd met explosieve ingrediënten als salpeter en zwavel. In het werk The Black Sun Sets komt de agressieve kant van het duister naar voren. Maar bij beeldend kunstenaar Pieter Laurens Mol (1946, Breda) staan de kleur zwart en het duister voor veel meer dan alleen vernietiging en dood.

Al sinds zijn jeugd is hij gefascineerd door de symbolische en de wetenschappelijke betekenissen van duisternis, zoals deze bijvoorbeeld terugkomen in de melancholie of astronomie. Zwarte gaten koppelt hij aan de zwaarmoedige lading van de Spaanse woorden confusión en pesimismo. De ‘o’s’ op de teksttekening Studie Voor Zwarte Gaten zijn uitgesneden. De zwaartekracht van de begrippen is zó groot dat de ‘o’s in een zwart gat weggezogen worden. Het werk toont de uitgesproken poëtische en lyrische kant van Mols kunst.

Al sinds zijn jeugd is hij gefascineerd door de symbolische en de wetenschappelijke betekenissen van duisternis, zoals deze bijvoorbeeld terugkomen in de melancholie of astronomie. Zwarte gaten koppelt hij aan de zwaarmoedige lading van de Spaanse woorden confusión en pesimismo. De ‘o’s’ op de teksttekening Studie Voor Zwarte Gaten zijn uitgesneden. De zwaartekracht van de begrippen is zó groot dat de ‘o’s in een zwart gat weggezogen worden. Het werk toont de uitgesproken poëtische en lyrische kant van Mols kunst.

Nachtvlucht is ingedeeld in zes thematische ensembles met namen als Nachtbraker, Hellevaart en Stille Smart. In de tentoonstelling word je meegenomen in zowel de destructie als de schoonheid van het duister. Het laatste ensemble, getiteld Geboorte van de Kleur, gaat over de hergeboorte die op het donker volgt.

Voor het werk The Total Amount vult Mol tientallen bakjes met pure pigmenten: ‘Om je ogen te planten in dit zuivere poeder uit de natuur voelt als een omarming, een prachtig intieme en intense ervaring.’ Hoog boven de kleurenbakjes hangt een fotonegatief van de kunstenaar zelf aan de muur. Hulpeloos bungelend aan een kraanwerker kan de eenzame schilder zo in één blik al het prachtige materiaal overzien dat tot zijn beschikking staat. Het idee dat hij schoonheid geboren kan laten worden zodra hij er mee aan de slag gaat vormt een hoopvolle gedachte.

Voor Mol zelf is het een tekenend werk uit de tentoonstelling. Hij onderzoekt op welke wijze de mens onderdeel is van een groter geheel en hoe hij zich daartoe kan verhouden.

Naast astronomie laat Mol zich inspireren door alchemie, natuurwetenschappen, mythologie, vaderlandse geschiedenis en oude kunst. Hierover zegt hij: ‘Een oud Egyptisch beeld kan dezelfde emotie oproepen als een stuk dat enkele minuten geleden is gemaakt. De enige echte tijd is het nu en ik breng er dingen uit het verleden en de toekomst naartoe.’

Net zo veelzijdig als zijn bronnen zijn de vormen waarin hij zich uitdrukt. Dat kunnen installaties, sculpturen of objecten zijn. Maar ook fotowerken, schilderijen, tekeningen en grafiek behoren tot de soms nooit eerder tentoongestelde werken.

Mol start zijn carrière in zijn geboorteplaats Breda. Van daaruit groeit hij uit tot een van de meest vooraanstaande kunstenaars van zijn generatie. Als een van de weinigen van zijn leeftijdsgenoten maakt hij de stap naar het buitenland.

De afgelopen vijftig jaar is zijn werk tentoongesteld bij toonaangevende instellingen wereldwijd, zoals het Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven, de Kunsthalle Basel, Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève, Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlijn, Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, Museum of Modern Art in New York en Heide Museum of Modern Art in Melbourne.  Daarnaast is Mols werk opgenomen in diverse publieke- en privécollecties.

Daarnaast is Mols werk opgenomen in diverse publieke- en privécollecties.

Voor Mol zijn de geschiedenis van Noord-Brabant en kunstenaars afkomstig uit deze regio een bron van inspiratie. De stad is, zeker in de beginperiode van zijn kunstenaarschap, een inspiratiebron.

Tijdens de tentoonstellingsperiode van Nachtvlucht wordt deze verbinding met de stad benadrukt. Zo wordt in de Grote Kerk Breda werk van hem getoond waarin de kerk een prominente rol heeft. Gelijktijdig met Nachtvlucht is er een tentoonstelling in de stad te bezoeken die in samenwerking met Stichting KOP ontwikkeld is en waarvoor vier jonge kunstenaars zijn uitgenodigd nieuw werk te maken voor de publieke ruimte dat geïnspireerd is op het oeuvre van Mol en de thematiek van Nachtvlucht.

Stedelijk Museum Breda

t/m 13 nov 2022

Pieter Laurens Mol – Nachtvlucht

Een ode aan de duisternis

Tentoonstelling

Stedelijk Museum Breda

Boschstraat 22

4811 GH Breda

076 529 9900

info@stedelijkmuseumbreda.nl

Pieter Laurens Mol

Nachtvlucht

W-Books

Speciaal voor de tentoonstelling Pieter Laurens Mol – Nachtvlucht, verschijnt de gelijknamige publicatie Nachtvlucht. In de publicatie wordt de lezer aan de hand van de uiteenlopende betekenissen van het duister en de kleur zwart meegenomen door het oeuvre van Pieter Laurens Mol. Zes thematische opgezette hoofdstukken belichten elk een deelgebied van deze thematiek in zijn werk, waarbij een ruime selectie beeldmateriaal een goed beeld geeft van zijn werk uit de jaren zestig tot nu.

Pieter Laurens Mol

Nachtvlucht

W-Books

Formaat 17 x 24 cm

Aantal pagina’s 192

In samenwerking met Stedelijk Museum Breda

Illustraties: Circa 100 afbeeldingen in kleur en zwartwit

ISBN 978 94 625 8491 4

Jaar 2022

Taal Nederlands

Uitvoering Gebonden

24,95 euro

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Archive M-N, Art & Literature News, AUDIO, CINEMA, RADIO & TV, Dutch Landscapes, Exhibition Archive, Pieter Laurens Mol

Mijn broertje vliegt

Voor mijn broer Peter

Ik kijk hoe onze vader af probeert te

drukken als mijn broertje door de lucht

beweegt. Kun je denken dat je vliegt

wanneer je amper weet dat je bestaat?

Niet zo heel ver weg van ons wieken

kraanvogels over deze lente heen. Licht

lijkt wel rood en motor mama tolt onder je

maar rond en rond zodat de lens bijna niet

weet hoe scherp te stellen. Daar blijf je dan

hangen op het ogenblik dat jij dat verre later

lijkt te weten. Je kijkt. Ik sta erbij en kijk

ernaar. Hoe hoog mijn broertje zweeft,

hoe blauw zijn broekje is. Hoe jong we zijn

besef ik al en ook hoe verder we nog mogen.

Hoe we leven in kamers zonder wolken.

Hoe rekbaar als de tijd wij schijnen.

Verschenen in de herinneringenspecial van

het tijdschrift G., Antwerpen, 2018

Gedicht: Bert Bevers

Illustratie: Peter Bevers

220922

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Bevers, Bert, Spurensicherung

« J’ai été aimantée par cette double mission impossible. Acheter la maison et retrouver les armes cachées. C’était inespéré et je n’ai pas flairé l’engrenage qui allait faire basculer notre existence. Parce que la maison est au coeur de ce qui a provoqué l’accident. »

En un récit tendu qui agit comme un véritable compte à rebours, Brigitte Giraud tente de comprendre ce qui a conduit à l’accident de moto qui a coûté la vie à son mari le 22 juin 1999. Vingt ans après, elle fait pour ainsi dire le tour du propriétaire et sonde une dernière fois les questions restées sans réponse.

En un récit tendu qui agit comme un véritable compte à rebours, Brigitte Giraud tente de comprendre ce qui a conduit à l’accident de moto qui a coûté la vie à son mari le 22 juin 1999. Vingt ans après, elle fait pour ainsi dire le tour du propriétaire et sonde une dernière fois les questions restées sans réponse.

Hasard, destin, coïncidences? Elle revient sur ces journées qui s’étaient emballées en une suite de dérèglements imprévisibles jusqu’à produire l’inéluctable. À ce point électrisé par la perspective du déménagement, à ce point pressé de commencer les travaux de rénovation, le couple en avait oublié que vivre était dangereux.

Brigitte Giraud mène l’enquête et met en scène la vie de Claude, et la leur, miraculeusement ranimées.

Brigitte Giraud est l’autrice de dix romans parmi lesquels À présent (Stock mention spéciale du prix Wepler 2001), L’amour est très surestimé (Stock bourse Goncourt de la nouvelle 2007), Une année étrangère (Stock prix Jean-Giono 2009), Un loup pour l’homme et Jour de courage (Flammarion 2017 et 2019).

Vivre vite

par Brigitte Giraud

Paru le 24/08/2022

Genre : Littérature française

Flammarion

208 pages

138 x 208 mm

Broché

EAN : 9782080207340

ISBN : 9782080207340

€ 20,00

• • •

Maison de la Poésie Paris

28 septembre 2022

BRIGITTE GIRAUD – VIVRE VITE

Rencontre animée par Sylvie Tanette

« Si je n’avais pas voulu vendre l’appartement. » « Si je ne m’étais pas entêtée à visiter cette maison. » « Si mon frère n’y avait pas garé sa moto pendant sa semaine de vacances. » « S’il avait plu. » Voici quelques-unes des questions qui hantent ce récit remuant. Vingt ans après, Brigitte Giraud tente de comprendre ce qui a conduit à l’accident de moto qui a coûté la vie à son mari. Hasard, destin, coïncidences ? En tout cas, une suite de dérèglements imprévisibles qui se solde par une tragédie : « Nous avions oublié que vivre était dangereux. » Un livre marquant.

À lire – Brigitte Giraud, Vivre vite, Flammarion, 2022.

Maison de la Poésie

Passage Moliėre

157, rue Saint-Martin – 75003 Paris

M ° Rambuteau – RER Les Halles

Mercredi 28 septembre 2022 – 21H00

tarif : 6 €

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive G-H, Maison de la Poésie

Ourselves Alone*

One morning, when dreaming in deep meditation,

I met a sweet colleen a-making her moan.

With sighing and sobbing she cried and lamented;

“Oh, where is my lost one, and where has he flown?

“My house it is small, and my field is but little,

Yet round flew my wheel as I sat in the sun,

He crossed the deep sea and went forth for my battle:

Oh, has he proved faithless—the fight is not won?”

And then I said: “Kathleen, ah! do you remember

When you were a queen, and your castles were strong,

You cried for the love of a cold-hearted stranger,

And in your fair island you planted the wrong?

“And oh,” I cried, “Kathleen, I once heard you weeping

And sighing and sobbing and making your moan.

You sang of a lost one, a dear one, a false one—

‘Oh, gone is my blackbird, and where has he flown?’

“Ah! many came forth to the sound of your crying,

And fought down the years for the freedom you pined.

How many lie still, in their cold exile sleeping,

Who sought in far lands your lost blackbird to find?

“And many are caught in the net of the stranger,

And all but forgotten the sound of your name,

For other loves call them to help and to save them:

They fell to dishonour—we hold them in shame.

“Oh, why drive me forth from your hearth into exile

And into far dangers? Your house is my own.

Faithful I serve, as I ever did serve you,

Standing together, ourselves—and alone.”

*Sinn Fein Amhain

Dora Maria Sigerson Shorter

(1866 – 1918)

Ourselves Alone

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Archive S-T, Sigerson Shorter, Dora Maria, WAR & PEACE

Shards of colours

I paint the world in the wet,

in colours mixed with liquid light,

and like tears of love, reality emerges

and seals itself therein.

The dormant awakes everywhere,

in my silence, in my journey,

and like the joy of happiness,

truth emerges and beauty stands.

An empty space in the universe

offers itself up to the feast before it.

Colours as miracles, drops of God’s

love for the immensity before us all.

I wash my hands after the day’s work,

the colours trickle from my fingers

like fish with sacred wings, I am given

these tiny shards of shimmering miracles,

and then when I wake the following day,

to my surprise, I find small traces remain

to remind me to rejoice in them again.

Vincent Berquez

Poem: Shards of colours

Vincent Berquez is a London–based artist and poet

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Berquez, Vincent, Vincent Berquez

Natur

Hinter den Häusern der Stadt, dort wo die Verbotstafeln

stehn,

beginnt Gottes freie Natur, die den Menschen gehört.

Parzelliert und in Grundbüchern eingetragen sind

die Quellen, die Äcker, die Wälder, der Wind,

die Tannen, die Eichen, die Buchen, die Linden,

die Hasen, die Hirsche, der Lerchenschlag,

der Mond in den Nächten, die Sonne am Achtstundentag

und die Vögel, die, von Sorgen angeblich unbeschwert,

die segensreiche Ordnung dieser Welt verkünden – –

Leibeigene Eichkätzchen springen auf Eichen,

als wären sie unabhängig vom Kapital – –

und wissen nicht, daß unterdessen Förster ohne Zahl

auf hinterlistigen Pfaden zum Schießen schleichen – –

Nur die Schriftsteller wandern umher und werden Wunder

gewahr

und schreiben Gedichte, Skizzen und Romane,

sie leben in ihrem göttlichen Wahne

und sterben vom menschlichen Honorar.

Joseph Roth

(1894 – 1939)

Natur

Lachen links – 1. 2. 1924

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive Q-R, Archive Q-R, Joseph Roth, MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY - department of ravens & crows, birds of prey, riding a zebra, spring, summer, autumn, winter

An Goethe

Das Unvergängliche

Ist nur dein Gleichnis!

Gott der Verfängliche

Ist Dichter-Erschleichnis…

Welt-Rad, das rollende,

Streift Ziel auf Ziel:

Not – nennt′ s der Grollende,

Der Narr nennt′ s – Spiel…

Welt-Spiel, das herrische,

Mischt Sein und Schein: –

Das Ewig-Närrische

Mischt uns – hinein!…

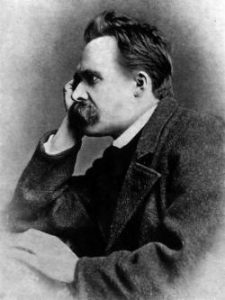

Friedrich Nietzsche

(1844 – 1900)

An Goethe

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive M-N, Archive M-N, Friedrich Nietzsche, Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von, Nietzsche

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature