Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (3)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926) The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio,

Cinematograph Operator by Luigi Pirandello

Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK I

OF THE NOTES OF SERAFINO GUBBIO CINEMATOGRAPH OPERATOR

3

I cannot get out of my mind the man I met a year ago, on the night of

my arrival in Rome.

It was in November, a bitterly cold night. I was wandering in search

of a modest lodging, not so much for myself, accustomed to spend my

nights in the open, on friendly terms with the bats and the stars, as

for my portmanteau, which was my sole worldly possession, left behind

in the railway cloakroom, when I happened to run into one of my

friends from Sassari, of whom I had long lost sight: Simone Pau, a man

of singular originality and freedom from prejudice. Hearing of my

hapless plight, he proposed that I should come and sleep that night in

his hotel. I accepted the invitation, and we set off on foot through

the almost deserted streets. On our way, I told him of my many

misadventures and of the frail hopes that had brought me to Rome.

Every now and then Simone Pau raised his hat-less head, on which the

long, sleek, grey hair was parted down the middle in flowing locks,

but zigzag, the parting being made with his fingers, for want of a

comb. These locks, drawn back behind his ears on either side, gave him

a curious, scanty, irregular mane. He expelled a large mouthful of

smoke, and stood for a while listening to me, with his huge swollen

lips held apart, like those of an ancient comic mask. His crafty,

mouselike eyes, sharp as needles, seemed to dart to and fro, as though

trapped in his big, rugged, massive face, the face of a savage and

unsophisticated peasant. I supposed him to have adopted this attitude,

with his mouth open, to laugh at me, at my misfortunes and hopes. But,

at a certain point in my recital, I saw him stop in the middle of the

street lugubriously lighted by its gas lamps, and heard him say aloud

in the silence of the night:

“Excuse me, but what do I know about the mountain, the tree, the sea?

The mountain is a mountain because I say: ‘That is a mountain.’ In

other words: ‘_I am the mountain_.’ What are we? We are whatever, at

any given moment, occupies our attention. I am the mountain, I am the

tree, I am the sea. I am also the star, which knows not its own

existence!”

I remained speechless. But not for long. I too have, inextricably

rooted in the very depths of my being, the same malady as my friend.

A malady which, to my mind, proves in the clearest manner that

everything that happens happens probably because the earth was made

not so much for mankind as for the animals. Because animals have in

themselves by nature only so much as suffices them and is necessary

for them to live in the conditions to which they were, each after its

own kind, ordained; whereas men have in them a superfluity which

constantly and vainly torments them, never making them satisfied with

any conditions, and always leaving them uncertain of their destiny. An

inexplicable superfluity, which, to afford itself an outlet, creates

in nature an artificial world, a world that has a meaning and value

for them alone, and yet one with which they themselves cannot ever be

content, so that without pause they keep on frantically arranging and

rearranging it, like a thing which, having been fashioned by

themselves from a need to extend and relieve an activity of which they

can see neither the end nor the reason, increases and complicates ever

more and more their torments, carrying them farther from the simple

conditions laid down by nature for life on this earth, conditions to

which only dumb animals know how to remain faithful and obedient.

My friend Simone Pau is convinced in good faith that he is worth a

great deal more than a dumb animal, because the animal does not know

and is content always to repeat the same action.

I too am convinced that he is of far greater value than an animal, but

not for those reasons. Of what benefit is it to a man not to be

content with always repeating the same action? Why, those actions that

are fundamental and indispensable to life, he too is obliged to

perform and to repeat, day after day, like the animals, if he does not

wish to die. All the rest, arranged and rearranged continually and

frantically, can hardly fail to reveal themselves sooner or later as

illusions or vanities, being as they are the fruit of that

superfluity, of which we do not see on this earth either the end or

the reason. And where did my friend Simone Pau learn that the animal

does not know? It knows what is necessary to itself, and does not

bother about the rest, because the animal has not in its nature any

superfluity. Man, who has a superfluity, and simply because he has it,

torments himself with certain problems, destined on earth to remain

insoluble. And this is where his superiority lies! Perhaps this

torment is a sign and proof (riot, let us hope, an earnest also) of

another life beyond this earth; but, things being as they are upon

earth, I feel that I am in the right when I say that it was made more

for the animals than for men.

I do not wish to be misunderstood. What I mean is, that on this earth

man is destined to fare ill, because he has in him more than is

sufficient for him to fare well, that is to say in peace and

contentment. And that it is indeed an excess, _for life on earth_,

this element which man has within him (and which makes him a man and

not a beast), is proved by the fact that it–this excess–never

succeeds in finding rest in anything, nor in deriving contentment from

anything here below, so that it seeks and demands elsewhere, beyond

the life on earth, the reason and recompense for its torment. So much

the worse, then, does man fare, the more he seeks to employ, upon the

earth itself, in frantic constructions and complications, his own

superfluity.

This I know, I who turn a handle.

As for my friend Simone Pau, the beauty of it is this: that he

believes that he has set himself free from all superfluity, reducing

all his wants to a minimum, depriving himself of every comfort and

living the naked life of a snail. And he does not see that, on the

contrary, he, by reducing himself thus, has immersed himself

altogether in the superfluity and lives now by nothing else.

That evening, having just come to Rome, I was not yet aware of this. I

knew him, I repeat, to be a man of singular originality and freedom

from prejudice, but I could never have imagined that his originality

and his freedom from prejudice would reach the point that I am about

to relate.

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (3)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shoot!

Street poetry: Anti-climb paint (London)

photo fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Street Art

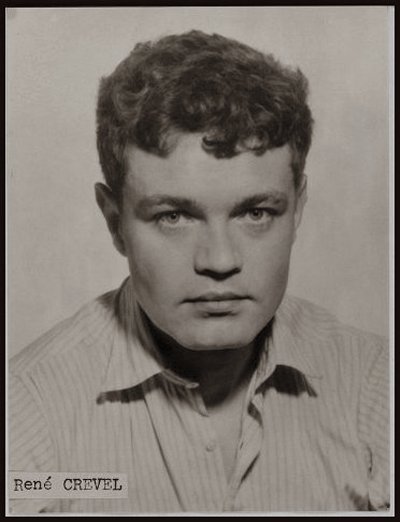

Renée Crevel

(1900-1935)

Regard

Ton regard couleur de fleuve

Est l’eau docile et qui change

Avec le jour qu’elle abreuve.

Petit matin, Robe d’ange

Un pan du manteau céleste

Sous tes cils, entre les rives

S’est pris. Coule, coule eau vive.

La nuit part, mais l’amour reste

Et ma main sent battre un cœur.

L’aube a voulu parer nos corps de sa candeur.

Fête-Dieu.

Le désir matinal a repris nos corps nus

Pour sculpter une chair que nous avions cru lasse.

Sur les fleuves au loin déjà les bateaux passent.

Nos peaux après l’amour ont l’odeur du pain chaud.

Si l’eau des fleuves est pour nos membres,

Tes yeux laveront mon âme ;

Mais ton regard liquide au midi que je crains

Deviendra-t-il de plomb ?

J’ai peur du jour, du jour trop long

Du jour qu’abreuve ton regard couleur de fleuve

Or dans un soir pavé pour de jumeaux triomphes

Si la victoire crie la volupté des anges,

Que se révèle en lui la Majesté d’un Gange.

Renée Crevel poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Crevel, Renée

Misschien klopt het niet allemaal, maar het is wel waar.

(Henk & Ingrid)

http://www.henkeningrid.org/

More in: MUSEUM OF PUBLIC PROTEST, The talk of the town

Amnesty International condemns harsh sentence for Chinese activist and writer Chen Wei

25 December 2011

The nine-year jail sentence handed down to activist Chen Wei for writing critical articles about the Communist Party is unacceptable, Amnesty International said today, and urged Chinese authorities to release him immediately and unconditionally.

Chen Wei was sentenced for “inciting subversion of state power”. His lawyer, Zheng Jianwei, said the trial lasted less than two hours and added that his family said he would not appeal.

“Chen Wei is being punished for peacefully expressing his ideas,” said Catherine Baber, Deputy Asia-Pacific Director for Amnesty International.

“I wish we could say we were surprised by this sentence, but we have seen the Chinese government use this vague charge of “incitement” over and over to silence its critics and suppress discussion of human rights and political change,” she added.

According to the indictment, seen by Amnesty International, Chen Wei’s charge stems from essays he allegedly posted online and “sent to overseas organizations,” including New York-based human rights group, Human Rights in China.

“This is the toughest sentence given to anyone who was arrested and charged during the so-called Jasmine crackdown, when the government rounded up activists out of fear for potential demonstrations inspired by the Middle East and North Africa,” Catherine Baber said.

“We think the government is punishing Chen Wei for his many years of activism and trying to send a strong message to any would-be critics.”

Chen Wei, 42, was one of more than 130 activists detained after the U.S.-based news site, Boxun, reported an anonymous appeal for people to stage protests across China last February.

The online call to protest, inspired by the uprisings across the Middle East and North Africa and the “Jasmine Revolution” in Tunisia, led to one of the harshest crackdowns on dissent in China in recent years.

Government critics, bloggers, artists, “netizens” and other activists were detained, the vast majority of whom have been released without charges or on bail.

Authorities in Suining City, Sichuan Province, detained Chen Wei on 20 February and formally arrested him on 28 March. Since then, he has been held at the Suining City Detention Centre. His case was sent back twice to prosecutors because of a lack of evidence.

Zheng Jianwei said he was only able to meet with his client twice. Another lawyer reportedly met with Chen Wei once. The activist has only been allowed to communicate with his family in writing.

Chen Wei served as one of the leaders of the 1989 student democracy movement, for which he was imprisoned until January 1991. In May 1992, authorities arrested him again, this time for commemorating the anniversary of the Tiananmen Square massacre and for organizing a political party. They sentenced him to five years for “counterrevolutionary propaganda and incitement.”

Chinese law does not define the meaning of “subversion,” nor does the law or related regulations or interpretations adequately define what it means to incite others to subvert state power.

Amnesty International is calling on the Chinese government to release other activists who have been held on the vague charge of “inciting subversion of state power,” including:

*“Netizen” Liang Haiyi, reportedly taken away by police on 19 February in the northern city of Harbin for sharing videos and information about the “Jasmine Revolution” on the Internet. Liang Haiyi, perhaps the first person to be arrested as part of the Jasmine crackdown, is reportedly being held on suspicion of “inciting subversion” and could be tried at any time.

*Veteran activist Chen Youcai, also known as Chen Xi, who was detained 29 November for being a member of the Guizhou Human Rights Forum, which authorities declared was an illegal organization. Chen Xi could stand trial at any time and, like Chen Wei, could face a harsh sentence due to his long work as a rights advocate.

*Human rights lawyer, Gao Zhisheng, who was sent back to prison last week after “violating” his probation, according to reports in China’s state media. Authorities charged him with “inciting subversion” in December 2006 and sentenced him to a three–year suspended prison sentence. He was initially held under house arrest and then subjected to enforced disappearance repeatedly over nearly three years.

•Nobel Peace Prize Winner Liu Xiaobo, who was awarded the prize in absentia on 10 December 2010. Liu Xiaobo was sentenced in 2009 to 11 years in prison for his role in drafting Charter 08, and other writings which called for democratic reforms. His wife, artist Liu Xia, is under illegal house arrest. She has not been charged with any crime and Amnesty International has called for authorities to immediately restore her freedom.

*Sichuan-based activist Liu Xianbin, who was sentenced in March to 10 years in prison for his role in promoting democratic reform, including his support of the Charter 08 petition movement.

*Beijing-based activist Hu Jia, who was released from prison in June after serving three and a half years for “inciting subversion” but now lives in conditions equivalent to house arrest along with his wife, Zeng Jinyan, and young daughter.

More information: http://www.amnesty.org/

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: REPRESSION OF WRITERS, JOURNALISTS & ARTISTS

William Shakespeare

(1564-1616)

THE SONNETS

108

What’s in the brain that ink may character,

Which hath not figured to thee my true spirit,

What’s new to speak, what now to register,

That may express my love, or thy dear merit?

Nothing sweet boy, but yet like prayers divine,

I must each day say o’er the very same,

Counting no old thing old, thou mine, I thine,

Even as when first I hallowed thy fair name.

So that eternal love in love’s fresh case,

Weighs not the dust and injury of age,

Nor gives to necessary wrinkles place,

But makes antiquity for aye his page,

Finding the first conceit of love there bred,

Where time and outward form would show it dead.

![]()

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shakespeare Sonnets

John Milton

(1608-1674 )

On Time

FLy envious Time, till thou run out thy race,

Call on the lazy leaden-stepping hours,

Whose speed is but the heavy Plummets pace;

And glut thy self with what thy womb devours,

Which is no more then what is false and vain,

And meerly mortal dross;

So little is our loss,

So little is thy gain.

For when as each thing bad thou hast entomb’d,

And last of all, thy greedy self consum’d,

Then long Eternity shall greet our bliss

With an individual kiss;

And Joy shall overtake us as a flood,

When every thing that is sincerely good

And perfectly divine,

With Truth, and Peace, and Love shall ever shine

About the supreme Throne

Of him, t’ whose happy-making sight alone,

When once our heav’nly-guided soul shall clime,

Then all this Earthy grosnes quit,

Attir’d with Stars, we shall for ever sit,

Triumphing over Death, and Chance, and thee O Time.

John Milton poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive M-N, Milton, John

![]()

P.C. Hooft-prijs 2012 voor Tonnus Oosterhoff

Het bestuur van de Stichting P.C. Hooft-prijs voor Letterkunde heeft maandag 19 december besloten de P.C. Hooft-prijs 2012 toe te kennen aan Tonnus Oosterhoff (Leiden, 1953). Deze oeuvreprijs is dit jaar bestemd voor poëzie en wordt uitgereikt op een feestelijke bijeenkomst in het Letterkundig Museum, op donderdag 24 mei 2012, drie dagen na de sterfdag van de naamgever van de prijs, de dichter P.C. Hooft (1581-1647), onze grootste renaissancedichter.

Tonnus Oosterhoff, van wie dit jaar de bundel Leegte lacht verscheen, ontving eerder belangrijke literaire prijzen voor afzonderlijke verschenen bundels, o.a.

de C. Buddingh’-prijs (1990) voor Boerentijger, de Herman Gorter-prijs (1994) voor De ingeland, de Jan Campert-prijs (1998) voor (Robuuste tongwerken,) een stralend plenum en de VSB Poëzieprijs (2003) voor Wij zagen ons in een klein groepje mensen veranderen.

De P.C. Hooft-prijs 2012 voor het gehele oeuvre van Tonnus Oosterhoff is toegekend op voordracht van een jury bestaande uit Kees Verheul (voorzitter), Yra van Dijk, Hester Knibbe, Erik Menkveld en Rob Schouten. Recente eerdere laureaten in het genre poëzie waren Hans Verhagen (2009), H.C. ten Berge (2006), H.H. ter Balkt (2003), Eva Gerlach (2000) en Judith Herzberg (1997). Aan de prijs is een bedrag verbonden van € 60.000.

Fragment uit het juryrapport:

– ‘Oosterhoffs poëzie is in hoge mate vernieuwend, ze heeft de Nederlandse dichtkunst van diverse keurslijven bevrijd, niet planmatig of vanuit een dichterlijke ideologie, maar door persoonlijke oorspronkelijkheid en het bijzondere talent van de auteur voor het vastleggen of liever gezegd juist beweeglijk maken van moeilijk benoembare sensaties.’

Het water begon zich te schamen

Het water begon zich te schamen

voor wat het was en altijd gedaan had.

Namens iedereen kwam een vis aan land

om een regeling te treffen.

De vis rechte zijn rug:

‘Mensen: drie wensen’

Het strand was leeg, alleen de schelpen

hadden de vorm van mutsen met oren eronder.

Het uitgekookte dier moest zijn lachen inhouden.

Ik kan beloven wat ik wil, dacht het

Dit kost me geen stuiver. De geschiedenis is ja nog niet begonnen.

Ik moest maar eens gaan teruglopen door de branding.

Of zal ik hier nog wat blijven? Droog ben ik nu toch.

Het is wel heerlijk, die zeewind.

Tonnus Oosterhoff

(Uit: Hersenmutor; gedichten 1990-2005, Bezige Bij 2005.)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Art & Literature News

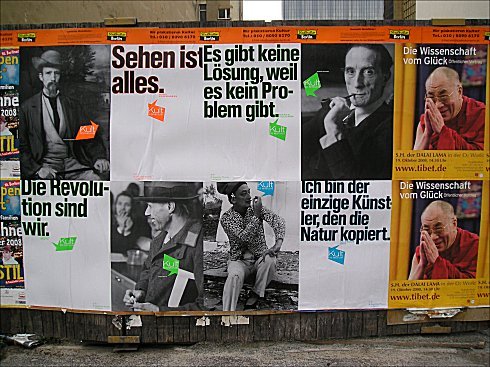

Street poetry: Betreten verboten (Berlin)

photo Anton K. – fleursdumal.nl poetry magazine

More in: Street Art

.jpg)

Georg Trakl

(1887-1914)

Romanze zur Nacht

Einsamer unterm Stenenzelt

Geht durch die Mitternacht.

Der Knab aus Träumen wirr erwacht,

Sein Antlitz grau im Mond verfällt.

Die Närrin weint mit offnem Haar

Am Fenster, das vergittert starrt.

Im Teich vorbei auf süßer Fahrt

Ziehn Liebende sehr wunderbar.

Der Mörder lächelt bleich im Wein,

Die Kranken Todesgrausen packt.

Die Nonne betet wund und nackt

Vor des Heilands Kreuzespein.

Die Mutter leis’ im Schlafe singt.

Sehr friedlich schaut zur Nacht das Kind

Mit Augen, die ganz wahrhaft sind.

Im Hurenhaus Gelächter klingt.

Beim Talglicht drunt’ im Kellerloch

Der Tote malt mit weißer Hand

Ein grinsend Schweigen an die Wand.

Der Schläfer flüstert immer noch.

.jpg)

Georg Trakl poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Trakl, Georg

Emily Dickinson

(1830-1886)

I Died For Beauty

I died for beauty, but was scarce

Adjusted in the tomb,

When one who died for truth was lain

In an adjoining room.

He questioned softly why I failed?

“For beauty,” I replied.

“And I for truth, — the two are one;

We brethren are,” he said.

And so, as kinsmen met a night,

We talked between the rooms,

Until the moss had reached our lips,

And covered up our names.

Emily Dickinson poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Dickinson, Emily

Street poetry: Sehen ist alles (Berlin)

photo Anton K. -fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Street Art

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature