Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

Emma Lazarus

(1849–1887)

Dreams

A dream of lilies: all the blooming earth,

A garden full of fairies and of flowers;

Its only music the glad cry of mirth,

While the warm sun weaves golden-tissued hours;

Hope a bright angel, beautiful and true

As Truth herself, and life a lovely toy,

Which ne’er will weary us, ne’er break, a new

Eternal source of pleasure and of joy.

A dream of roses: vision of Loves tree,

Of beauty and of madness, and as bright

As naught on earth save only dreams can be,

Made fair and odorous with flower and light;

A dream that Love is strong to outlast Time,

That hearts are stronger than forgetfulness,

The slippery sand than changeful waves that climb,

The wind-blown foam than mighty waters’ stress.

A dream of laurels: after much is gone,

Much buried, much lamented, much forgot,

With what remains to do and what is done,

With what yet is, and what, alas! is not,

Man dreams a dream of laurel and of bays,

A dream of crowns and guerdons and rewards,

Wherein sounds sweet the hollow voice of praise,

And bright appears the wreath that it awards.

A dream of poppies, sad and true as Truth,—

That all these dreams were dreams of vanity;

And full of bitter penitence and ruth,

In his last dream, man deems ’twere good to die;

And weeping o’er the visions vain of yore,

In the sad vigils he doth nightly keep,

He dreams it may be good to dream no more,

And life has nothing like Death’s dreamless sleep.

Emma Lazarus poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Archive Tombeau de la jeunesse, Archive K-L, Lazarus, Emma

Renée Vivien

(1877–1909)

Prolong the night

Prolong the night, Goddess who sets us aflame!

Hold back from us the golden-sandalled dawn!

Already on the sea the first faint gleam

Of day is coming on.

Sleeping under your veils, protect us yet,

Having forgotten the cruelty day may give!

The wine of darkness, wine of the stars let

Overwhelm us with love!

Since no one knows what dawn will come,

Bearing the dismal future with its sorrows

In its hands, we tremble at full day, our dream

Fears all tomorrows.

Oh! keeping our hands on our still-closed eyes,

Let us vainly recall the joys that take flight!

Goddess who delights in the ruin of the rose,

Prolong the night!

Renée Vivien poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive U-V, Renée Vivien, Vivien, Renée

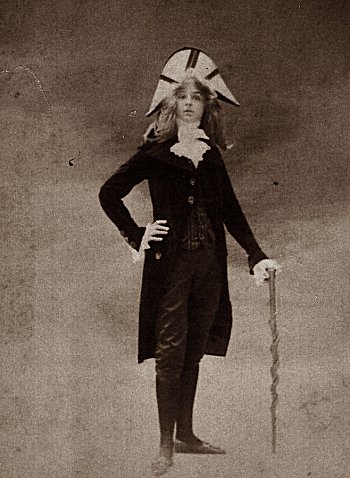

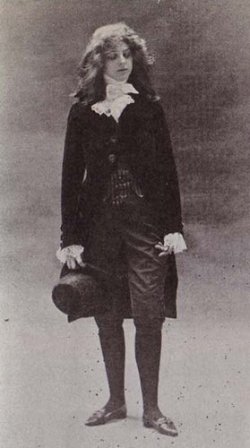

Renée Vivien (1877–1909)

born Pauline Mary Tarn (11 June 1877 – 18 November 1909) was a writer and poet.

She was born in London and has been buried in Paris in Cimetière de Passy.

photos: jef van kempen 2011

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: FDM in Paris, Galerie des Morts, Renée Vivien, Vivien, Renée

Henry Bataille

(1872-1922)

Le mois mouillé

Par les vitres grises de la lavanderie,

J’ai vu tomber la, nuit d’automne que voilà…

Quelqu’un marche le long des fossés pleins de pluie…

Voyageur, voyageur de jadis, qui t’en vas,

A l’heure où les bergers descendent des montagnes,

Hâte-toi. – Les foyers sont éteints où tu vas,

Closes les portes au pays que tu regagnes…

La grande route est vide et le bruit des luzernes

Vient de si loin qu’il ferait peur… Dépêche-toi :

Les vieilles carrioles ont soufflé leurs lanternes…

C’est l’automne : elle s’est assise et dort de froid

Sur la chaise de paille au fond de la cuisine…

L’automne chante dans les sarments morts des vignes…

C’est le moment où les cadavres introuvés,

Les blancs noyés, flottant, songeurs, entre deux ondes,

Saisis eux-mêmes aux premiers froids soulevés,

Descendent s’abriter dans les vases profondes.

Henry Bataille poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Bataille, Henry

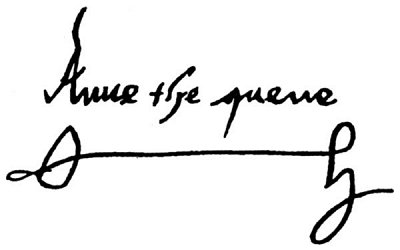

ANNE BOLEYN (1507-1536)

It was for Anne that Henry VIII gave up the wife with whom he had lived for twenty years; it was for Anne that he broke his hitherto unbroken allegiance of England to the Pope of Rome; tl was for Anne that he braved the anger of the great powers of Europe.Yet it was this same Anne who, but two years after her marriage, was writing to her passionate lover the following heart-broken letter—while awaiting her death.

TO THE KING

SIR, Your Grace’s displeasure and my imprisonment are things so strange unto me, as what to write, or what to excuse, I am altogether ignorant. Whereas you send unto me (willing [me] to confess a truth, and to obtain your favour) by such an one whom you know to be mine ancient professed enemy. I no sooner conceived this message by him, than I rightly conceived your meaning; and, as you say, confessing a truth indeed may procure my safety, I shall with all willingness and duty perform your command.

But let not your Grace ever imagine that your poor wife will ever be brought to acknowledge a fault where not so much as a thought thereof proceeded. And to speak a truth, never prince had wife more loyal in all duty, and in all true affection, than you have ever found in Anne Boleyn; with which name and place I could willingly have contented myself, if God and your Grace’s pleasure had been so pleased. Neither did I at any time so far forget myself in my exaltation or received queenship, but that I always looked for such an alteration as now I find: for the ground of my preferment being on no surer foundation than your Grace’s fancy, the least alteration I knew was fit and sufficient to draw that fancy to some other subject. You have chosen me from a low estate to be your queen and companion, far beyond my desert or desire. If then you found me worthy of such honour, good your Grace, let not any light fancy or bad counsel of mine enemies withdraw your princely favour from me; neither let that stain, that unworthy stain, of a disloyal heart towards your good Grace, ever cast so foul a blot on your most dutiful wife, and the infant princess, your daughter.

Try me, good king, but let me have a lawful trial; and let not my sworn enemies sit as my accusers and my judges; yea, let me receive an open trial, for my truth shall fear no open shame. Then shall you see either mine innocency cleared, your suspicions and conscience satisfied, the ignominy and slander of the world stopped, or my guilt openly declared; so that, whatsoever God or you may determine of me, your Grace may be freed from an open censure; and mine offence being so lawfully proved, your Grace is at liberty, both before God and man, not only to execute worthy punishment on me, as an unlawful wife, but to follow your affection already settled on that party for whose sake I am now as I am, whose name I could some good while since have pointed unto; your Grace not being ignorant of my suspicion therein.

But if you have already determined of me; and that not only my death, but an infamous slander, must bring you the enjoying of your desired happiness; then I desire of God that he will pardon your great sin therein, and likewise my enemies the instruments thereof; and that He will not call you to a strict account for your unprincely and cruel usage of me, at his general judgementseat, where both you and myself must shortly appear; and in whose judgement, I doubt not, whatsoever the world may think of me, mine innocence shall be openly known and sufficiently cleared.

My last and only request shall be, that myself may only bear the burden of your Grace’s displeasure, and that it may not touch the innocent souls of those poor gentlemen who, as I understand, are likewise in strait imprison¬ment for my sake. If ever I have found favour in your sight, if ever the name of Anne Boleyn hath been pleasing in your ears, then let me obtain this request; and I will so leave to trouble your Grace any further; with mine earnest prayers to the Trinity, to have your Grace in his good keeping, and to direct you in all your actions. From my doleful prison in the Tower, this 6th of May. Your most loyal and ever faithful wife.

ANNE BOLEYN (1536)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Anne Boleyn, Archive A-B

Een diva en haar nachtegalen

De stilte maakt haar gedachten onrustig

zij die denkt het leven te beheersen

met koffie, vrienden en bio-groenten

zij weet dat het anders kan

met vaste eettijdstippen, slaaprituelen

uitstappen en familiebezoeken

meer als vroeger

retro, dit woord bekt nu beter

is ze ouderwets, niet van deze planeet

verzuurd, gefrustreerd of alternatief bevlogen

ze opent koffer waar de muziekplaten in zitten

haar vingers weten precies waar te stoppen

uit een afgeleefde kaft, haar lievelingsnummer

in het spiegelglas van de keukendeur zingt ze

als diva, zo doordringend hapervrij dat

zelfs de nachtegalen op de linnen lampenkap

zich blozend verrast omdraaien

Erica De Stercke

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, De Stercke, Erika

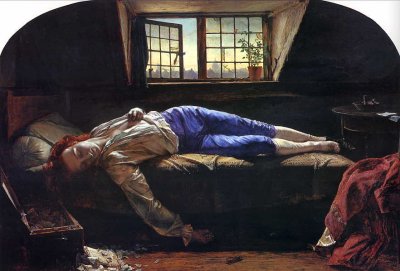

Thomas Chatterton

(1752-1770)

A New Song

Ah blame me not, Catcott, if from the right way

My notions and actions run far.

How can my ideas do other but stray,

Deprived of their ruling North-Star?

A blame me not, Broderip, if mounted aloft,

I chatter and spoil the dull air;

How can I imagine thy foppery soft,

When discord’s the voice of my fair?

If Turner remitted my bluster and rhymes,

If Hardind was girlish and cold,

If never an ogle was got from Miss Grimes,

If Flavia was blasted and old;

I chose without liking, and left without pain,

Nor welcomed the frown with a sigh;

I scorned, like a monkey, to dangle my chain,

And paint them new charms with a lie.

Once Cotton was handsome; I flam’d and I burn’d,

I died to obtain the bright queen;

But when I beheld my epistle return’d,

By Jesu it alter’d the scene.

She’s damnable ugly, my Vanity cried,

You lie, says my Conscience, you lie;

Resolving to follow the dictates of Pride,

I’d view her a hag to my eye.

But should she regain her bright lustre again,

And shine in her natural charms,

‘Tis but to accept of the works of my pen,

And permit me to use my own arms.

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Chatterton, Thomas, Thomas Chatterton

P.C. Boutens

(1870-1943)

Avondwandeling

Langs de lampverlichte straten,

Onbewust als ademhalen,

Tusschen vreemde menschgelaten

Loop ik avondlijk te dwalen.

Doffe wanden wijken. Leef ik

Dieper of ondieper leven? –

Licht door lichte wezens zweef ik

Als gezamenlijk geheven.

Oogen peilen, oogen stralen

Van gedachten vluchtger, lichter

Dan waar woorden van verhalen

In de wijzen van den dichter.

Wondere geheimen kelken

Rooder monden volle boorden –

Schromen voor het ras verwelken

Der ontbloeide bloemewoorden.

Kussen konden wij en dansen

Al nachts glansbeslagen uren,

Maar wij kiezen ons verschansen

In dit klare koele turen

Waar wij geven en ontvangen

In en uit onze eenzaamheden

Schatten nooit bekend verlangen,

Levens zuivre diepste reden.

P.C. Boutens poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Boutens, P.C.

Freda Kamphuis©

Titel: k’s

multimedia 2013

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Freda Kamphuis, Kamphuis, Freda

Esther Porcelijn

WZDOJ?

In de trein.

Twee dames voor mij bespreken hun zorgen: “..Dus ík zeg tegen haar, je moet je kind juíst even laten huilen, anders raakt ze te gewend aan haar moeder die bij elke kik op haar afrent. Kinderen kunnen met je sollen hoor. Nou, wat ik tóen toch over mij heen kreeg! Dus ik zeg, kijk, het is maar míjn mening hoor. Ik denk dus, even tussen ons, dat ze echt overbezorgd is. Komt door de band met haar eigen moeder enzo.”

De andere vrouw antwoordt: “Maar, dan denk ik toch, waarom voel jij de behoefte om haar iets te vertellen over haar kind? Wat zegt dat over jou en jouw band met je moeder? Ik vraag het mij gewoon af hè, mijn mening.”

Ergens tussen de weilanden en de vrouwen vraag ik mij af of het waar is dat wat jij vindt van anderen en de wereld, meer zegt over jezelf dan over die wereld of die anderen.

Zou het?

Zou het zo zijn dat de tuttigheid waarin ik die vrouwen neerpen iets zegt over mij? Ben ik tuttig? Of juist bang voor tuttigheid? Moet ik daar dan iets aan doen?

Hoe wij kijken, waar onze aandacht naartoe gaat, zegt wellicht iets over onze interesses. En, filosofisch gezien, is er wat voor te zeggen dat wij zelfs alles wat wij zien/proeven/voelen, en waar wij een begrip van vormen, meer zegt over ons kenapparaat en onze hersens dan dat wij werkelijk alles waarnemen als exact beeld van de werkelijkheid. Wij kunnen bijvoorbeeld geen tijd waarnemen, maar wel verandering. Het feit dat we een concept vormen van tijd zegt iets over ons interne systeem (dat concepten op waarnemingen plakt), maar weinig over de ‘echte’ werkelijkheid.

Zou kunnen.

Maar, als je dit doortrekt dan is al onze beleving een gevolg van dit interne systeem. Al is het niet zo dat een Kantiaan je ooit, als je huilt om een zielige dierenreclame, zal beschuldigen van het bezitten van een eigenaardige verstandscategorie (interne concepten).

Het gaat hier dus niet om filosofie maar om psychologie.

Let op: De grond is hier ijskoud!

Mensen die deze: “Wat Zegt Het Over Jou”-methode toepassen bedoelen meestal dat het aanwijzen van een probleem met een ander mens, of fenomeen, in het leven iets zegt over jouw eigen angsten en problemen en dat heftige reacties op bepaald gedrag vaak wijzen op het feit dat je zelf misschien bang bent dat je zulk gedrag vertoont. Dat je iets stiekem herkent, of indirect reageert op een ander iemand uit je verleden (vader, moeder, opa). Dat je dit conflict van vroeger, dit trauma, projecteert op de persoon of het fenomeen in het heden.

‘Projectie’ is een woord wat heel veel gebruikt wordt in dit soort gesprekken. De mensen die deze WZDOJ-methode veel toepassen hebben namelijk allemaal een abonnement op het Psychologie Magazine.

Een paar voorbeelden:

Stel, je haat katten.

Vroeg of laat zal iemand vragen waarom je katten haat.

Je antwoordt dat je niet houdt van haren op je kleren en dat je hun scherpe nagels naar vindt.

De gesprekspartner zal dan vragen of er ooit iets in je leven is gebeurd (bij voorkeur in de jeugd) waardoor je nu deze gevoelens ervaart.

Dit geval is nog te doen want, inderdaad, je opa had een valse kat. Zelfs als je niet weet waarom je katten niet mag vind je het nog geen extreem domme vraag.

Dan, valt je bij het eten met vrienden in een restaurant op dat de ober heel gehaast is en amper aandacht aan je besteedt. Hij zegt niet eens ‘tot ziens’ nadat je de rekening hebt betaald.

Je vindt dit onbeleefd en klaagt erover bij je vrienden. Een vriend merkt op dat het restaurant erg vol was en dat de ober misschien met zijn handen in het haar zat door het harde werken. De vriend vindt dat jij het gedrag te snel als onbeleefd hebt afgedaan. Jij antwoordt dat je toch betaalt in een restaurant voor het eten en dat de aandacht van het personeel daarbij hoort. De vriend zegt nu dat de aandacht nu eenmaal niet altijd naar jou gericht kan zijn en hij vraagt zich af wat dit over jou zegt dat jij deze behoefte wel schijnt te hebben.

Dit laatste voorbeeld is meer een interpretatie en inlevingskwestie. Die vriend leeft zich in, jij niet. Dan nog is het zeer vervelend dat die vriend de bal naar jou kaatst en vraagt wat dit over jou zegt. Je vraagt je toch af waarom hij dit zou vragen, een ober hoort toch beleefd te zijn?

Nu, je bent zo iemand die weinig warme gevoeld koestert ten opzichte van het huwelijk.

Een vriendin van je gaat trouwen en, ondanks dat je blij bent voor haar, begrijp je werkelijk niets van die keuze, waarom zou iemand in deze tijd nog trouwen?

Je deelt je twijfels over de idee huwelijk met je vrienden en een vriendin merkt op dat dit wellicht iets over jou zou kunnen zeggen. “Ben jij zelf bang voor een commitment”, vraagt ze. Je zegt dat je denkt van niet, dat je gewoon niet snapt dat twee mensen zo’n ouderwetse afspraak nodig hebben om hun liefde te bevestigen. Je vriendin begint uiteraard weer te morren en zegt: “Klinkt toch als een indirecte vorm van bindingsangst hoor!”

Bij dit laatste voorbeeld is het zo vervelend als iemand deze methode toepast omdat je dus het hele inhoudelijke gesprek niet meer kan voeren. Je staat schaakmat. Wat je nu ook zegt, het zal allemaal een bevestiging zijn van haar vermoedens en diagnose: Bindingsangst. Zal wel.

Dan heb je nog de allerergste vorm: Het soort mensen dat minstens 5 jaar een abonnement heeft lopen op het Psychologie Magazine en de drang niet kan weerstaan om, als iemand anders in de ruimte de WZDOJ-methode heeft uitgekraamd, zelf nog even extra toegepast zegt: “Maar, wat zegt dit over jou dat jij zo begint over de achterliggende redenen van iemands gedrag?”

De opmerking lijkt scherp maar wordt jammer genoeg altijd net iets te schertsend gebracht, met een blik waaruit blijkt dat deze persoon zichzelf zeer opmerkzaam vindt, waardoor het heel naar wordt. Daarbij is het hier een retorisch trucje.

Laatst was ik op een feest en mijn vriendje had een enorme mep op zijn hoofd gekregen. Hij moest naar huis want hij knoeide bloed over de dansvloer.

Ik ging, ondanks dat ik nog wel zin had om te dansen, met hem mee naar huis.

Om afscheid te nemen van twee vriendinnen ging ik terug de dansvloer op. Ik riep dat ik naar huis ging. “Wat? Nu al??” vroeg de ene. Ik zei dat ik met mijn vriendje echt naar huis moest. “Oja!”, zei ze, “jij hebt natuurlijk een relatie!” Ik zei dat ik het zelf ook fijn zou vinden als hij met mij mee zou gaan als ik in die situatie zou zitten. Zij riep meteen uit, met de armen in de lucht op de dancemuziek: “God, wat ben ík blij dat ik geen relatie heb!” De andere vriendin riep mee. Ik kon niets meer zeggen. Ik wilde heel graag zeggen dat deze opmerking betuigt van exact het omgekeerde en dat iemand die zo’n opmerking maakt het allerliefste een vriendje zou willen hebben. Inclusief IKEA-huis met twee labradors, en wel zeven abbonementen op elke vorm van Libelle of psychowhatever, dat dit haast wel haar allergrootste droom moet zijn.

Maar ik zei het niet. Het deed pijn maar ik hield mij in.

De vraag is dus wat je aan dit fenomeen kan doen. Hoe krijgen we deze vreselijke methode van de aardbodem? Moet er wel iets aan gedaan worden?

Wat kun je nog zeggen op zo’n moment, misschien is er geen goed antwoord op de WZDOJ-methode te geven.

Is het een interessante vraag naar de fundamenten van de menselijke intentie of is het een retorisch trucje?

Wat zegt het?

Het zegt iets over mij dat ik inschat dat het nog meer over jou zegt. En zo zeggen we dingen over elkaar, prima.

Wat het over mij zegt dat ik hiermee zit?

Of ik iets heb meegemaakt waardoor ik nu..

Ja, inderdaad. Heb een enorm trauma.

Veel te groot om over te schrijven, letterlijk. Past niet op dit vel/scherm.

Gigantisch!

Esther Porcelijn: WZDOJ?

Eerder gepubliceerd in: Univers Blog

photo: fleursdumal.nl

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Porcelijn, Esther, Porcelijn, Esther

Trucage

Het is wat: een tijd waarin nog geloofd wordt,

een tijd waarin matrassen streepjes hebben,

uit kussens veertjes steken. Messen met

paarlemoeren heft trillen in geurig wildgebraad,

en van gezuiverde zinnen slaan vlammetjes.

Wij werden wie we zijn. Vermoed: achter

doorkijkspiegels worden kushandjes geblazen.

Bert Bevers

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Bevers, Bert

John Keats

(1795 – 1821)

To some ladies

What though while the wonders of nature exploring,

I cannot your light, mazy footsteps attend;

Nor listen to accents, that almost adoring,

Bless Cynthia’s face, the enthusiast’s friend:

Yet over the steep, whence the mountain stream rushes,

With you, kindest friends, in idea I rove;

Mark the clear tumbling crystal, its passionate gushes,

Its spray that the wild flower kindly bedews.

Why linger you so, the wild labyrinth strolling?

Why breathless, unable your bliss to declare?

Ah! you list to the nightingale’s tender condoling,

Responsive to sylphs, in the moon beamy air.

‘Tis morn, and the flowers with dew are yet drooping,

I see you are treading the verge of the sea:

And now! ah, I see it–you just now are stooping

To pick up the keep-sake intended for me.

If a cherub, on pinions of silver descending,

Had brought me a gem from the fret-work of heaven;

And smiles, with his star-cheering voice sweetly blending,

The blessings of Tighe had melodiously given;

It had not created a warmer emotion

Than the present, fair nymphs, I was blest with from you,

Than the shell, from the bright golden sands of the ocean

Which the emerald waves at your feet gladly threw.

For, indeed, ’tis a sweet and peculiar pleasure,

(And blissful is he who such happiness finds,)

To possess but a span of the hour of leisure,

In elegant, pure, and aerial minds.

john keats poetry

fleursdumal.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive K-L, John Keats, Keats, John

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature