Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

The Sorrows of Young Werther (36) by J.W. von Goethe

JANUARY 8, 1772.

What beings are men, whose whole thoughts are occupied with form and

ceremony, who for years together devote their mental and physical

exertions to the task of advancing themselves but one step, and

endeavouring to occupy a higher place at the table. Not that such

persons would otherwise want employment: on the contrary, they give

themselves much trouble by neglecting important business for such petty

trifles. Last week a question of precedence arose at a sledging-party,

and all our amusement was spoiled.

The silly creatures cannot see that it is not place which constitutes

real greatness, since the man who occupies the first place but

seldom plays the principal part. How many kings are governed by their

ministers–how many ministers by their secretaries? Who, in such cases,

is really the chief? He, as it seems to me, who can see through the

others, and possesses strength or skill enough to make their power or

passions subservient to the execution of his own designs.

JANUARY 20.

I must write to you from this place, my dear Charlotte, from a small

room in a country inn, where I have taken shelter from a severe storm.

During my whole residence in that wretched place D–, where I lived

amongst strangers,–strangers, indeed, to this heart,–I never at any

time felt the smallest inclination to correspond with you; but in this

cottage, in this retirement, in this solitude, with the snow and hail

beating against my lattice-pane, you are my first thought. The instant

I entered, your figure rose up before me, and the remembrance! O my

Charlotte, the sacred, tender remembrance! Gracious Heaven! restore to

me the happy moment of our first acquaintance.

Could you but see me, my dear Charlotte, in the whirl of

dissipation,–how my senses are dried up, but my heart is at no time

full. I enjoy no single moment of happiness: all is vain–nothing

touches me. I stand, as it were, before the raree-show: I see the little

puppets move, and I ask whether it is not an optical illusion. I am

amused with these puppets, or, rather, I am myself one of them: but,

when I sometimes grasp my neighbour’s hand, I feel that it is not

natural; and I withdraw mine with a shudder. In the evening I say I will

enjoy the next morning’s sunrise, and yet I remain in bed: in the day I

promise to ramble by moonlight; and I, nevertheless, remain at home. I

know not why I rise, nor why I go to sleep.

The leaven which animated my existence is gone: the charm which cheered

me in the gloom of night, and aroused me from my morning slumbers, is

for ever fled.

I have found but one being here to interest me, a Miss B–. She

resembles you, my dear Charlotte, if any one can possibly resemble you.

“Ah!” you will say, “he has learned how to pay fine compliments.” And

this is partly true. I have been very agreeable lately, as it was not

in my power to be otherwise. I have, moreover, a deal of wit: and the

ladies say that no one understands flattery better, or falsehoods you

will add; since the one accomplishment invariably accompanies the

other. But I must tell you of Miss B–. She has abundance of soul,

which flashes from her deep blue eyes. Her rank is a torment to her, and

satisfies no one desire of her heart. She would gladly retire from

this whirl of fashion, and we often picture to ourselves a life of

undisturbed happiness in distant scenes of rural retirement: and then we

speak of you, my dear Charlotte; for she knows you, and renders homage

to your merits; but her homage is not exacted, but voluntary, she loves

you, and delights to hear you made the subject of conversation.

Oh, that I were sitting at your feet in your favourite little room, with

the dear children playing around us! If they became troublesome to you,

I would tell them some appalling goblin story; and they would crowd

round me with silent attention. The sun is setting in glory; his last

rays are shining on the snow, which covers the face of the country: the

storm is over, and I must return to my dungeon. Adieu!–Is Albert with

you? and what is he to you? God forgive the question.

The Sorrows of Young Werther (Die Leiden des jungen Werther) by J.W. von Goethe. Translated by R.D. Boylan.

To be continued

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: -Die Leiden des jungen Werther, Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von

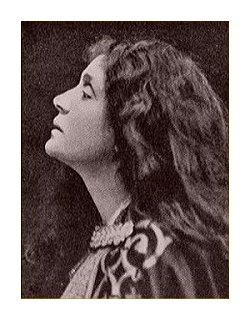

Renée Vivien

(1877-1909)

Ta royale jeunesse a la mélancolie

Ta royale jeunesse a la mélancolie

Du Nord où le brouillard efface les couleurs,

Tu mêles la discorde et le désir aux pleurs,

Grave comme Hamlet, pâle comme Ophélie.

Tu passes, dans l’éclair d’une belle folie,

Comme elle, prodiguant les chansons et les fleurs,

Comme lui, sous l’orgueil dérobant tes douleurs,

Sans que la fixité de ton regard oublie.

Souris, amante blonde, ou rêve, sombre amant,

Ton être double attire, ainsi qu’un double aimant,

Et ta chair brûle avec l’ardeur froide d’un cierge.

Mon coeur déconcerté se trouble quand je vois

Ton front pensif de prince et tes yeux bleus de vierge,

Tantôt l’Un, tantôt l’Autre, et les Deux à la fois.

Renée Vivien poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive U-V, Renée Vivien, Vivien, Renée

Hans Leybold

(1892-1914)

Auf einer Feldpostkarte

Zerflossen alles

in wirren Schaum,

mein Hirn ein weiter

luftleerer Raum.

Von außen schlagen

die Hämmer drauf:

mein Schädel ist

ein Kirchturmknauf.

Hans Leybold poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: *War Poetry Archive, Archive K-L, Hans Leybold, Leybold, Hans

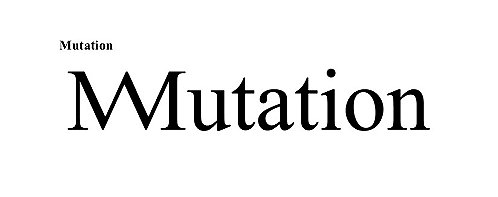

Rob Stuart: Mutation

Biography: Rob Stuart is a media studies lecturer, filmmaker and writer living in Southeast England. He has contributed poetry to a variety of magazines and e-zines including Ink, Sweat & Tears, Light, Lighten Up Online, Magma, New Statesman, The Oldie, The Spectator and Snakeskin.

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: *Concrete + Visual Poetry P-T, Rob Stuart, Rob Stuart, Stuart, Rob

Photo by David Shankbone

In memory of Lucy Gordon

To One in Paradise

by Edgar Allan Poe

Thou wast that all to me, love,

For which my soul did pine—

A green isle in the sea, love,

A fountain and a shrine,

All wreathed with fairy fruits and flowers,

And all the flowers were mine.

Ah, dream too bright to last!

Ah, starry Hope! that didst arise

But to be overcast!

A voice from out the Future cries,

“On! on!”—but o’er the Past

(Dim gulf!) my spirit hovering lies

Mute, motionless, aghast!

For, alas! alas! with me

The light of Life is o’er!

No more—no more—no more—

(Such language holds the solemn sea

To the sands upon the shore)

Shall bloom the thunder-blasted tree,

Or the stricken eagle soar!

And all my days are trances,

And all my nightly dreams

Are where thy grey eye glances,

And where thy footstep gleams—

In what ethereal dances,

By what eternal streams.

20 May 2014: In memory of Lucy Gordon (22 May 1980 – 20 May 2009)

Photo Lucy gordon by David Shankbone: Lucy Gordon at the 2007 premiere of Spider-Man 3

(David Shankbone: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license), 2007)

Tombeau de la Jeunesse – fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: In Memoriam, Lucy Gordon, Poe, Edgar Allan

Emma Lazarus

(1849 – 1887)

Loneliness

All stupor of surprise hath passed away;

She sees, with clearer vision than before,

A world far off of light and laughter gay,

Herself alone and lonely evermore.

Folk come and go, and reach her in no wise,

Mere flitting phantoms to her heavy eyes.

All outward things, that once seemed part of her,

Fall from her, like the leaves in autumn shed.

She feels as one embalmed in spice and myrrh,

With the heart eaten out, a long time dead;

Unchanged without, the features and the form;

Within, devoured by the thin red worm.

By her own prowess she must stand or fall,

This grief is to be conquered day by day.

Who could befriend her? who could make this small,

Or her strength great? she meets it as she may.

A weary struggle and a constant pain,

She dreams not they may ever cease nor wane.

Emma Lazarus poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Lazarus, Emma

The Sorrows of Young Werther (35) by J.W. von Goethe

DECEMBER 24.

As I anticipated, the ambassador occasions me infinite annoyance. He is

the most punctilious blockhead under heaven. He does everything step by

step, with the trifling minuteness of an old woman; and he is a man whom

it is impossible to please, because he is never pleased with himself. I

like to do business regularly and cheerfully, and, when it is finished,

to leave it. But he constantly returns my papers to me, saying, “They

will do,” but recommending me to look over them again, as “one may

always improve by using a better word or a more appropriate particle.”

I then lose all patience, and wish myself at the devil’s. Not a

conjunction, not an adverb, must be omitted: he has a deadly antipathy

to all those transpositions of which I am so fond; and, if the music

of our periods is not tuned to the established, official key, he cannot

comprehend our meaning. It is deplorable to be connected with such a

fellow.

My acquaintance with the Count C–is the only compensation for such an

evil. He told me frankly, the other day, that he was much displeased

with the difficulties and delays of the ambassador; that people like him

are obstacles, both to themselves and to others. “But,” added he, “one

must submit, like a traveller who has to ascend a mountain: if the

mountain was not there, the road would be both shorter and pleasanter;

but there it is, and he must get over it.”

The old man perceives the count’s partiality for me: this annoys him,

and, he seizes every opportunity to depreciate the count in my hearing.

I naturally defend him, and that only makes matters worse. Yesterday he

made me indignant, for he also alluded to me. “The count,” he said, “is

a man of the world, and a good man of business: his style is good,

and he writes with facility; but, like other geniuses, he has no solid

learning.” He looked at me with an expression that seemed to ask if I

felt the blow. But it did not produce the desired effect: I despise a

man who can think and act in such a manner. However, I made a stand, and

answered with not a little warmth. The count, I said, was a man entitled

to respect, alike for his character and his acquirements. I had never

met a person whose mind was stored with more useful and extensive

knowledge,–who had, in fact, mastered such an infinite variety of

subjects, and who yet retained all his activity for the details of

ordinary business. This was altogether beyond his comprehension; and I

took my leave, lest my anger should be too highly excited by some new

absurdity of his.

And you are to blame for all this, you who persuaded me to bend my

neck to this yoke by preaching a life of activity to me. If the man who

plants vegetables, and carries his corn to town on market-days, is not

more usefully employed than I am, then let me work ten years longer at

the galleys to which I am now chained.

Oh, the brilliant wretchedness, the weariness, that one is doomed

to witness among the silly people whom we meet in society here! The

ambition of rank! How they watch, how they toil, to gain precedence!

What poor and contemptible passions are displayed in their utter

nakedness! We have a woman here, for example, who never ceases to

entertain the company with accounts of her family and her estates. Any

stranger would consider her a silly being, whose head was turned by

her pretensions to rank and property; but she is in reality even

more ridiculous, the daughter of a mere magistrate’s clerk from this

neighbourhood. I cannot understand how human beings can so debase

themselves.

Every day I observe more and more the folly of judging of others by

ourselves; and I have so much trouble with myself, and my own heart is

in such constant agitation, that I am well content to let others pursue

their own course, if they only allow me the same privilege.

What provokes me most is the unhappy extent to which distinctions of

rank are carried. I know perfectly well how necessary are inequalities

of condition, and I am sensible of the advantages I myself derive

therefrom; but I would not have these institutions prove a barrier to

the small chance of happiness which I may enjoy on this earth.

I have lately become acquainted with a Miss B–, a very agreeable girl,

who has retained her natural manners in the midst of artificial life.

Our first conversation pleased us both equally; and, at taking leave,

I requested permission to visit her. She consented in so obliging a

manner, that I waited with impatience for the arrival of the happy

moment. She is not a native of this place, but resides here with her

aunt. The countenance of the old lady is not prepossessing. I paid her

much attention, addressing the greater part of my conversation to her;

and, in less than half an hour, I discovered what her niece subsequently

acknowledged to me, that her aged aunt, having but a small fortune, and

a still smaller share of understanding, enjoys no satisfaction except

in the pedigree of her ancestors, no protection save in her noble birth,

and no enjoyment but in looking from her castle over the heads of the

humble citizens. She was, no doubt, handsome in her youth, and in her

early years probably trifled away her time in rendering many a poor

youth the sport of her caprice: in her riper years she has submitted

to the yoke of a veteran officer, who, in return for her person and her

small independence, has spent with her what we may designate her age of

brass. He is dead; and she is now a widow, and deserted. She spends her

iron age alone, and would not be approached, except for the loveliness

of her niece.

The Sorrows of Young Werther (Die Leiden des jungen Werther) by J.W. von Goethe. Translated by R.D. Boylan.

To be continued

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: -Die Leiden des jungen Werther, Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von

Verhuizing van een vrouwelijke stadsdichter

Als het droste-effect hoogtij viert

En scheve ogen uit oude mannen puilen

Om net onder mijn rok te kijken

Wachtend op hun jeugdigheid

Heb ik toch geen medelijden.

Was ik maar één van hen,

Een rijpere oude man

onder mijn eigen rok kijkend.

Elke dag dat ik verplaats is

Als een enorme verhuizing

Maar mochten mensen bang zijn

Dat ik te Amsterdams ben

Wees niet gevreesd,

Ik ben ook maar een mens.

We zitten allen in dezelfde carrousel.

Het ene paardje is roze en de andere paars

Maar allen in dezelfde carrousel van het droste-effect.

Merry Go-Merry Go

Merry Go Round

Misschien word ik ooit nog een echte vent.

Tot die tijd ben ik de kleinste vrouw,

of, als ik op een landkaart sta, de grootste ter wereld.

Het is wit en het staat in het Vondelpark..

Witte gij ut?

Esther Porcelijn

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Porcelijn, Esther

Renée Vivien

(1877-1909)

Prolong the night

Prolong the night, Goddess who sets us aflame!

Hold back from us the golden-sandalled dawn!

Already on the sea the first faint gleam

Of day is coming on.

Sleeping under your veils, protect us yet,

Having forgotten the cruelty day may give!

The wine of darkness, wine of the stars let

Overwhelm us with love!

Since no one knows what dawn will come,

Bearing the dismal future with its sorrows

In its hands, we tremble at full day, our dream

Fears all tomorrows.

Oh! keeping our hands on our still-closed eyes,

Let us vainly recall the joys that take flight!

Goddess who delights in the ruin of the rose,

Prolong the night!

Renée Vivien poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive U-V, Renée Vivien, Vivien, Renée

Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven

(1874 – 1927)

CAFÉ DU DÔME

FOR THE LOVE OF MIKE !

LOOK AT THAT –

MARCELLED –

BE – WHISKERED –

BE – SPATTED –

PATHETIC –

LYMPHATIC –

ESTHETIC-

PIGPINK –

QUAINT –

NATTY –

SAINT KYK!

GARCON?? !

UN PNEUMATIC CROSS – AVEC SUCTIONDISC’S

TOPPED AVEC RUBBER THISTLE WREATH –

S’IL VOUS PLAIT.

E.V.F.L

Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive E-F, Dada, Freytag-Loringhoven, Elsa von

Cookham door Stanley Spencer en

Jezus Christus aan de vergetelheid ontrukt

Gemeen aan Jordaan en Theems is het water. Wat nog?

Natuurlijk de aanwezigheid van Jezus Christus.

Want de verlosser predikte niet enkel in Kafarnaüm,

Gadara en Gennezaret maar deed ook Cookham,

Berkshire, aan. Kijk er Stanley Spencer maar op na.

De schilder bedenkt ons. Met prekend de koning

der joden tijdens regatta’s. Met punters vol mensen

die zich verbazen over dit tegengif voor wantijd.

Op de oevers begerig beschouwen. Hier en daar

toch ongelovigen ook, vrouwen veelal. Koudogige.

Zelfs massale verrijzenis in het dorp laat hen onbewogen,

alsof ze een bioscoop leeg zien lopen. Herkennen ze dan

Matthew Sweeney’s oma niet die jonger en dunner

dan ooit opstaat uit de doden? Zijn ze ervaren in verdwalen?

In mijn geheugen is het gebeier van de kathedraal getatoeëerd.

Drieslagsmaten. Vijfduizendenveertig variaties.

Een man die veertig jaren klokken luidde moest van een arm af.

Bert Bevers

(uit In de buurt van de wereld, Uitgeverij Kleinood & Grootzeer, Bergen op Zoom, 2002)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Bevers, Bert

Sara Teasdale

(1884 – 1933)

I Shall Not Care

When I am dead and over me bright April

Shakes out her rain-drenched hair,

Tho’ you should lean above me broken-hearted,

I shall not care.

I shall have peace, as leafy trees are peaceful

When rain bends down the bough,

And I shall be more silent and cold-hearted

Than you are now.

Sara Teasdale poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Teasdale, Sara

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature