Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

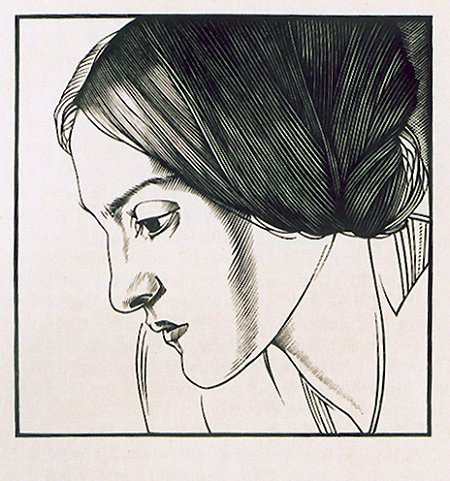

Christina Rossetti

(1830-1894)

In an Artist’s Studio

One face looks out from all his canvases,

One selfsame figure sits or walks or leans;

We found her hidden just behind those screens,

That mirror gave back all her loveliness.

A queen in opal or in ruby dress,

A nameless girl in freshest summer-greens,

A saint, an angel; – every canvass means

The same one meaning, neither more nor less.

He feeds upon her face by day and night,

And she with true kind eyes looks back on him

Fair as the moon and joyful as the light:

Not wan with waiting, not with sorrow dim;

Not as she is, but was when hope shone bright;

Not as she is, but as she fills his dream.

1856

In een schildersatelier

Uit al zijn doeken kijkt slechts één gezicht,

Slechts één figuur die loopt, of zit, of rijst;

We ontdekten haar pal achter elke lijst,

Waar haar lieftalligheid weerspiegeld ligt.

‘n Prinses, gekleed in rood of in opaal,

Een naamloos wicht in zomergroenen fris,

Engel of heilige; – ‘n betekenis

Die steeds dezelfde is, bij allemaal.

Hij leeft bij dag en nacht van haar gezicht,

En zij blikt terug, haar oog van trouw vervuld

Fraai als de maan, en vreugdevol als ‘t licht:

Niet bleek van smart, en niet vol ongeduld;

Niet als ze is, maar was, hoop nog in zicht;

Niet als zij is, maar zoâls zijn droom zij vult.

Volgens een andere broer van Christina en Dante Gabriel zou het beschreven portret dat van Elizabeth Siddal zijn, die later met D.G. Rossetti trouwde.

Uit: Bestorm mijn hart, de beste Engelse gedichten uit de 16e-19e eeuw gekozen en vertaald door Cornelis W. Schoneveld, tweetalige editie. Rainbow Essentials no. 55, Uitgeverij Maarten Muntinga, Amsterdam, 2008, 296 pp, € 9,95 ISBN: 9789041740588

Bestorm mijn hart bevat een dwarsdoorsnede van vier eeuwen lyrische Engelse dichtkunst. Dichters uit de zestiende tot en met de negentiende eeuw dichter onder andere over liefde, natuur, dood en religie. Niet alleen de Nederlandse vertaling is in deze bundel te vinden, maar ook de originele Engelse versie. Deze prachtige bloemlezing, met gedichten van onder anderen Shakespeare, Milton, Pope en Wordsworth, is samengesteld en vertaald door Cornelis W. Schoneveld. Hij is vele jaren docent historische Engelse letterkunde en vertaalwetenschapper aan de Universiteit van Leiden geweest.

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Rossetti, Rossetti, Christina

Choosing’- George Frederic Watts – London 1864 – Oil on strawboard – National Portrait Gallery, London – This painting depicts the young actress Ellen Terry reaching out to the opulent but scentless camellia and discarding the common, but fragrant violets in her hand

Victoria & Albert Museum London

until 17 July 2011 last chance to see

THE CULT OF BEAUTY

THE AESTHETIC MOVEMENT 1860-1900

The exhibition has been arranged in four main chronological sections, charting the development of the Aesthetic Movement in art and design through the decades from the 1860s to the 1890s. As well as paintings, prints and drawings, the show will include examples of all the ‘artistic’ decorative arts, together with drawings, designs and photographs, as well as portraits, fashionable dress and jewellery of the era. Literary life will be represented by some of the most beautiful books of the day, whilst a number of set-pieces will reveal the visual world of the Aesthetes, evoking the kind of rooms and ensembles of exquisite objects through which they expressed their sensibilities.

‘Symphony in White, No. 3′- James McNeill Whistler – London 1867 – Oil on canvas – The Trustees of the Barber Institute of Fine Arts, University of Birmingham – One critic claimed that this painting was ‘not precisely a symphony in white’ because it also included other colours. Whistler retorted that ‘a symphony in F…contains no other note, but a continued repetition of F, F, F-Fool!’

The search for new beauty

1860s

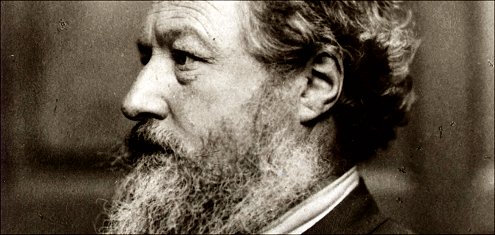

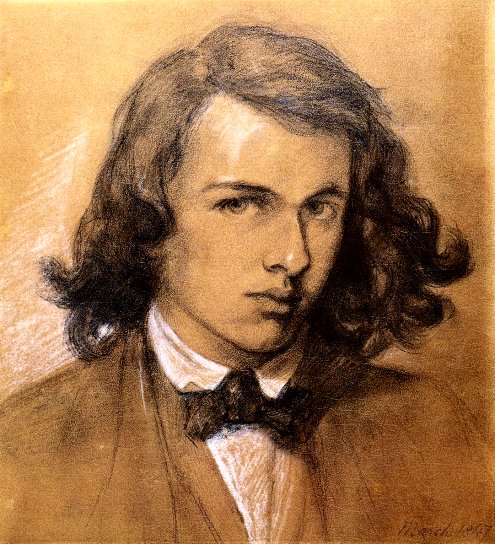

In the 1860s the new and exciting ‘Cult of Beauty’ united, for a while at least, romantic bohemians such as Dante Gabriel Rossetti (and his younger Pre-Raphaelite followers William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones), maverick figures such as James McNeill Whistler, then fresh from Paris and full of ‘dangerous’ French ideas about modern painting, and the ‘Olympians’ – the painters of grand classical subjects who belonged to the circle of Frederic Leighton and G.F.Watts. Choosing unconventional models, such as Rossetti’s muse Lizzie Siddal or Leighton’s sultry favourite ‘La Nanna’, these painters created entirely new types of female beauty.

Rossetti and his friends were also the first to attempt to realise their imaginative world in the creation of ‘artistic’ furniture and the decoration of rooms. In this period, artists’ houses and their extravagant lifestyles became the object of public fascination and sparked a revolution in the architecture and interior decoration of houses that led to a widespread recognition of the need for beauty in everyday life.

Armchair – Lawrence Alma-Tadema – Made by Johnstone, Norman & Co. London 1884-6 – Mahogany, with cedar and ebony veneer, inlay of several woods, ivory and abalone shell – Museum no. W.25:1-1980 – This armchair was designed for a ‘Greek parlour’ and belonged to Henry Gourdon Marquand, the second director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York

Art for Arts Sake

1870s-1880s

One of the most important examples of the mutual influence between artists and designers is to be found in the startling collaborations between James McNeill Whistler and the architect E.W.Godwin who designed the painter’s studio, The White House, and created some of the most innovative furniture of the day. Characterised equally by elegance and eccentricity, Whistler and Godwin’s work drew upon influences as diverse as ancient Greek art and the Japanese prints and other artifacts just beginning to arrive in Europe.

In the 1870s, the leading Aesthetic artists, Whistler, Leighton, Watts, Albert Moore and Burne-Jones evolved a new kind of self-consciously exquisite painting in which mood, colour harmony and beauty of form were all, and subject played little or no part. The opening of the Grosvenor Gallery (with its famous ‘greenery-yallery’ walls) in 1877 at last gave the Aesthetic painters a fashionable and glamorous showcase for their much-discussed art. But the decade closed with intense controversy exemplified by the critic John Ruskin’s savage attack on Whistler, which prompted the painter’s spirited defence of the ideals of ‘Art for Art’s Sake’ in his writings and by the staging of his own exhibitions.

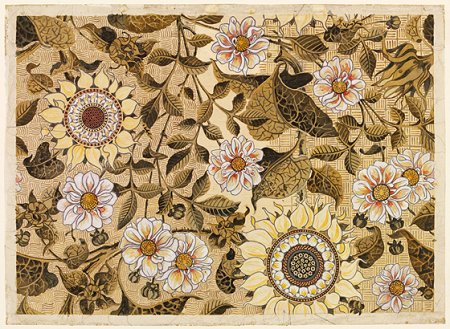

Design for ‘The Sunflower’ wallpaper – Bruce James Talbert – Made by Jeffrey & Co. London 1878 – Watercolour and body colour – Museum no. E.37-1945 Given by Mrs Margaret Warner – The wallpaper manufacturer Jeffrey & Co. employed Aesthetic designers such as Bruce Talbert to bring ‘art’ to their products

Beautiful people and Aesthetic houses

1870s-1880s

The immense success of the Grosvenor Gallery signalled the emergence of a new artistic elite whose social prestige offered an unprecedented challenge to the Royal Academy. Aesthetic painting became the fashionable enthusiasm of a circle that was grand, wealthy and intellectual. As well as buying paintings these new patrons were keen to embrace Aesthetic ideals, commissioning portraits and even adopting the styles of ‘artistic’ dress.

The rise of Aestheticism in painting was paralleled in the decorative arts by a new and increasingly widespread interest in the decoration of houses. Many of the key avant-garde architects and designers interested themselves not only in working for wealthy clients but also in the reform of design for the middle-class home. The notion of ‘The House Beautiful’ became a touchstone of cultured life.

Attracted by the growing popularity of Aesthetic taste, many of the leading firms making furniture, ceramics, domestic metalwork and textiles courted artists such as Walter Crane and a growing band of professional designers, most notably Christopher Dresser. Co-inciding with a period of unprecedented expansion of domestic markets, the styles favoured by Aesthetic designers were among the very first to be exploited and disseminated widely through commercial enterprise.

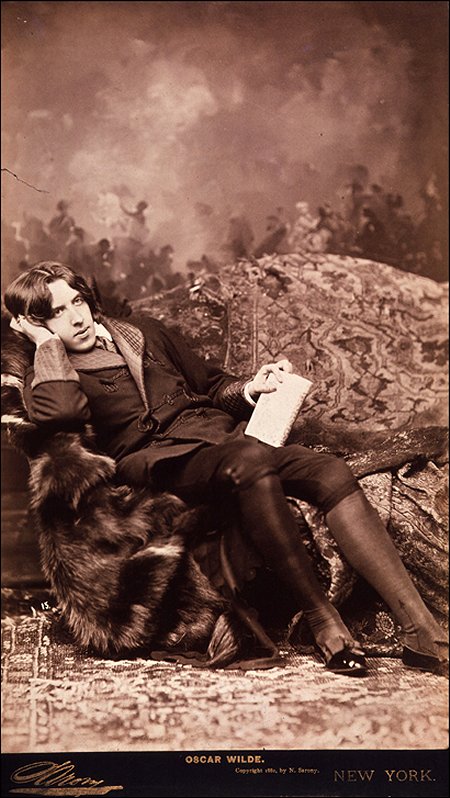

‘Oscar Wilde’ – Napoleon Sarony – New York 1882 – Albumen panel print – National Portrait Gallery, London – Sarony’s photographs, taken at the beginning of Oscar Wilde’s American lecture tour, fixed his image in the public imagination as the epitome of the Aesthete

Late-flowering beauty

1880s-1890s

Oscar Wilde, the first celebrity style-guru, invented a brilliant pose of ‘poetic intensity’, but initially made his name promoting the idea of ‘The House Beautiful’. By the 1880s Britain was in the grip of the ‘greenery-yallery’ Aesthetic Craze, lovingly satirised by Gilbert and Sullivan in their famous comic opera Patience and by the caricaturist George Du Maurier in the pages of Punch.

In the last decade of Queen Victoria’s reign the Aesthetic Movement entered its final, fascinating Decadent phase, characterised by the extraordinary black-and-white drawings of Aubrey Beardsley in The Yellow Book.

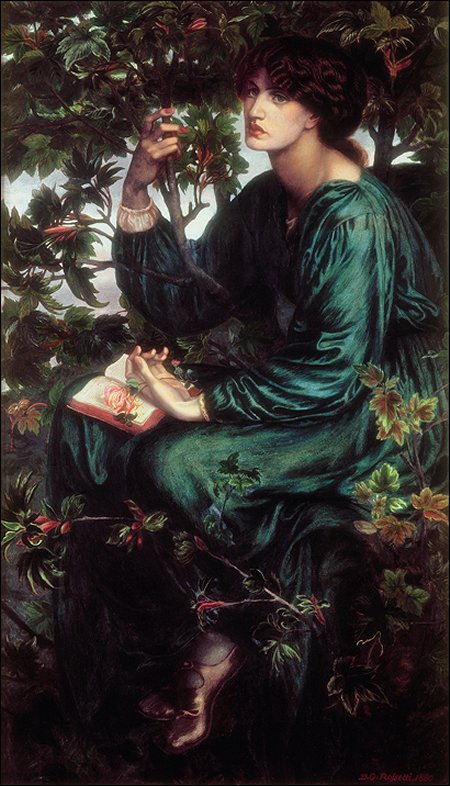

The exhibition ends with a superb group of the greatest late Aesthetic paintings, including masterpieces such as Leighton’s Bath of Psyche, Moore’s Midsummer and Rossetti’s final picture The Daydream, shown alongside the sensuous nude figures sculpted in bronze and precious materials by Alfred Gilbert and other brilliant younger exponents of ‘The New Sculpture’.

‘The Day Dream’ – Dante Gabriel Rossetti – 1880 London – Oil on canvas – Museum no. CAI.3 – Bequeathed by Constantine Alexander Ionides – This is one of the last major oil paintings that Rossetti completed. The lush green leaves match the fullness of Jane Morris’s figure in her green silk dress

Victoria & Albert Museum London

until 17 July 2011 last chance to see

THE CULT OF BEAUTY: THE AESTHETIC MOVEMENT 1860-1900

‘Icarus’ – Alfred Gilbert – Rome and Naples – Cast in the foundry of Sabatino de Angelis 1884 – Bronze – Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales – © National Museum of Wales – Frederic Leighton commissioned Gilbert to produce a bronze statue, leaving him to choose the subject. Gilbert took the mythical figure of Icarus, the ambitious youth who flew too close to the sun

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: *The Pre-Raphaelites Archive

.jpg)

George Meredith

(1828 – 1909)

Winter Heavens

Sharp is the night, but stars with frost alive

Leap off the rim of earth across the dome.

It is a night to make the heavens our home

More than the nest whereto apace we strive.

Lengths down our road each fir-tree seems a hive,

In swarms outrushing from the golden comb.

They waken waves of thoughts that burst to foam:

The living throb in me, the dead revive.

Yon mantle clothes us: there, past mortal breath,

Life glistens on the river of the death.

It folds us, flesh and dust; and have we knelt,

Or never knelt, or eyed as kine the springs

Of radiance, the radiance enrings:

And this is the soul’s haven to have felt.

Photos: Hans Hermans 2010 – Natuurdagboek November 2010

Poem: George Meredith

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: 4SEASONS#Winter, Hans Hermans Photos, Meredith, George

.jpg)

Dirge in Woods

by George Meredith

(1828 – 1909)

A wind sways the pines,

And below

Not a breath of wild air;

Still as the mosses that glow

On the flooring and over the lines

Of the roots here and there.

The pine-tree drops its dead;

They are quiet, as under the sea.

Overhead, overhead

Rushes life in a race,

As the clouds the clouds chase;

And we go,

And we drop like the fruits of the tree,

Even we,

Even so.

Photos: Hans Hermans 2010 – Natuurdagboek september 2010

Poem: George Meredith

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Hans Hermans Photos, Meredith, George

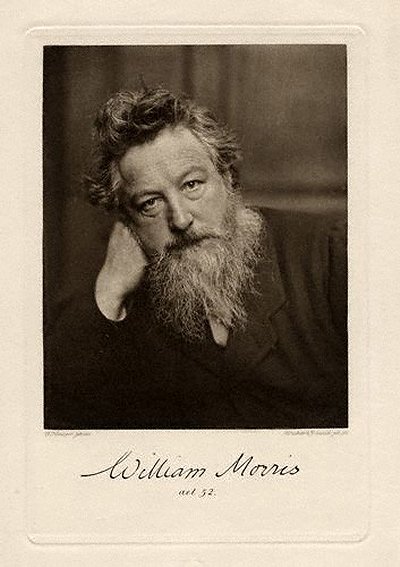

William Morris

(1834-1896)

A Death Song

What cometh here from west to east awending?

And who are these, the marchers stern and slow?

We bear the message that the rich are sending

Aback to those who bade them wake and know.

Not one, not one, nor thousands must they slay,

But one and all if they would dusk the day.

We asked them for a life of toilsome earning,

They bade us bide their leisure for our bread;

We craved to speak to tell our woeful learning:

We come back speechless, bearing back our dead.

Not one, not one, nor thousands must they slay,

But one and all if they would dusk the day.

They will not learn; they have no ears to hearken.

They turn their faces from the eyes of fate;

Their gay-lit halls shut out the skies that darken.

But, lo! this dead man knocking at the gate.

Not one, not one, nor thousands must they slay,

But one and all if they would dusk the day.

Here lies the sign that we shall break our prison;

Amidst the storm he won a prisoner’s rest;

But in the cloudy dawn the sun arisen

Brings us our day of work to win the best.

Not one, not one, nor thousands must they slay,

But one and all if they would dusk the day.

![]()

William Morris poetry

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Morris, William

.jpg)

Virginia Woolf

(1882-1941)

“I Am Christina Rossetti”

On the fifth of this December [1930] Christina Rossetti will celebrate her centenary, or, more properly speaking, we shall celebrate it for her, and perhaps not a little to her distress, for she was one of the shyest of women, and to be spoken of, as we shall certainly speak of her, would have caused her acute discomfort. Nevertheless, it is inevitable; centenaries are inexorable; talk of her we must. We shall read her life; we shall read her letters; we shall study her portraits, speculate about her diseases — of which she had a great variety; and rattle the drawers of her writing-table, which are for the most part empty. Let us begin with the biography — for what could be more amusing? As everybody knows, the fascination of reading biographies is irresistible. No sooner have we opened the pages of Miss Sandars’s careful and competent book (Life of Christina Rossetti, by Mary F. Sandars. (Hutchinson)) than the old illusion comes over us. Here is the past and all its inhabitants miraculously sealed as in a magic tank; all we have to do is to look and to listen and to listen and to look and soon the little figures — for they are rather under life size — will begin to move and to speak, and as they move we shall arrange them in all sorts of patterns of which they were ignorant, for they thought when they were alive that they could go where they liked; and as they speak we shall read into their sayings all kinds of meanings which never struck them, for they believed when they were alive that they said straight off whatever came into their heads. But once you are in a biography all is different.

Here, then, is Hallam Street, Portland Place, about the year 1830; and here are the Rossettis, an Italian family consisting of father and mother and four small children. The street was unfashionable and the home rather poverty-stricken; but the poverty did not matter, for, being foreigners, the Rossettis did not care much about the customs and conventions of the usual middle-class British family. They kept themselves to themselves, dressed as they liked, entertained Italian exiles, among them organ-grinders and other distressed compatriots, and made ends meet by teaching and writing and other odd jobs. By degrees Christina detached herself from the family group. It is plain that she was a quiet and observant child, with her own way of life already fixed in her head — she was to write — but all the more did she admire the superior competence of her elders. Soon we begin to surround her with a few friends and to endow her with a few characteristics. She detested parties. She dressed anyhow. She liked her brother’s friends and little gatherings of young artists and poets who were to reform the world, rather to her amusement, for although so sedate, she was also whimsical and freakish, and liked making fun of people who took themselves with egotistic solemnity. And though she meant to be a poet she had very little of the vanity and stress of young poets; her verses seem to have formed themselves whole and entire in her head, and she did not worry very much what was said of them because in her own mind she knew that they were good. She had also immense powers of admiration — for her mother, for example, who was so quiet, and so sagacious, so simple and so sincere; and for her elder sister Maria, who had no taste for painting or for poetry, but was, for that very reason, perhaps more vigorous and effective in daily life. For example, Maria always refused to visit the Mummy Room at the British Museum because, she said, the Day of Resurrection might suddenly dawn and it would be very unseemly if the corpses had to put on immortality under the gaze of mere sight-seers — a reflection which had not struck Christina, but seemed to her admirable. Here, of course, we, who are outside the tank, enjoy a hearty laugh, but Christina, who is inside the tank and exposed to all its heats and currents, thought her sister’s conduct worthy of the highest respect. Indeed, if we look at her a little more closely we shall see that something dark and hard, like a kernel, had already formed in the centre of Christina Rossetti’s being.

It was religion, of course. Even when she was quite a girl her lifelong absorption in the relation of the soul with God had taken possession of her. Her sixty-four years might seem outwardly spent in Hallam Street and Endsleigh Gardens and Torrington Square, but in reality she dwelt in some curious region where the spirit strives towards an unseen God — in her case, a dark God, a harsh God — a God who decreed that all the pleasures of the world were hateful to Him. The theatre was hateful, the opera was hateful, nakedness was hateful — when her friend Miss Thompson painted naked figures in her pictures she had to tell Christina that they were fairies, but Christina saw through the imposture — everything in Christina’s life radiated from that knot of agony and intensity in the centre. Her belief regulated her life in the smallest particulars. It taught her that chess was wrong, but that whist and cribbage did not matter. But also it interfered in the most tremendous questions of her heart. There was a young painter called James Collinson, and she loved James Collinson and he loved her, but he was a Roman Catholic and so she refused him. Obligingly he became a member of the Church of England, and she accepted him. Vacillating, however, for he was a slippery man, he wobbled back to Rome, and Christina, though it broke her heart and for ever shadowed her life, cancelled the engagement. Years afterwards another, and it seems better founded, prospect of happiness presented itself. Charles Cayley proposed to her. But alas, this abstract and erudite man who shuffled about the world in a state of absent-minded dishabille, and translated the gospel into Iroquois, and asked smart ladies at a party “whether they were interested in the Gulf Stream”, and for a present gave Christina a sea mouse preserved in spirits, was, not unnaturally, a free thinker. Him, too, Christina put from her. Though “no woman ever loved a man more deeply”, she would not be the wife of a sceptic. She who loved the “obtuse and furry”— the wombats, toads, and mice of the earth — and called Charles Cayley “my blindest buzzard, my special mole”, admitted no moles, wombats, buzzards, or Cayleys to her heaven.

So one might go on looking and listening for ever. There is no limit to the strangeness, amusement, and oddity of the past sealed in a tank. But just as we are wondering which cranny of this extraordinary territory to explore next, the principal figure intervenes. It is as if a fish, whose unconscious gyrations we had been watching in and out of reeds, round and round rocks, suddenly dashed at the glass and broke it. A tea-party is the occasion. For some reason Christina went to a party given by Mrs. Virtue Tebbs. What happened there is unknown — perhaps something was said in a casual, frivolous, tea-party way about poetry. At any rate,

suddenly there uprose from a chair and paced forward into the centre of the room a little woman dressed in black, who announced solemnly, “I am Christina Rossetti!” and having so said, returned to her chair.

With those words the glass is broken. Yes [she seems to say], I am a poet. You who pretend to honour my centenary are no better than the idle people at Mrs. Tebb’s tea-party. Here you are rambling among unimportant trifles, rattling my writing-table drawers, making fun of the Mummies and Maria and my love affairs when all I care for you to know is here. Behold this green volume. It is a copy of my collected works. It costs four shillings and sixpence. Read that. And so she returns to her chair.

How absolute and unaccommodating these poets are! Poetry, they say, has nothing to do with life. Mummies and wombats, Hallam Street and omnibuses, James Collinson and Charles Cayley, sea mice and Mrs. Virtue Tebbs, Torrington Square and Endsleigh Gardens, even the vagaries of religious belief, are irrelevant, extraneous, superfluous, unreal. It is poetry that matters. The only question of any interest is whether that poetry is good or bad. But this question of poetry, one might point out if only to gain time, is one of the greatest difficulty. Very little of value has been said about poetry since the world began. The judgment of contemporaries is almost always wrong. For example, most of the poems which figure in Christina Rossetti’s complete works were rejected by editors. Her annual income from her poetry was for many years about ten pounds. On the other hand, the works of Jean Ingelow, as she noted sardonically, went into eight editions. There were, of course, among her contemporaries one or two poets and one or two critics whose judgment must be respectfully consulted. But what very different impressions they seem to gather from the same works — by what different standards they judge! For instance, when Swinburne read her poetry he exclaimed: “I have always thought that nothing more glorious in poetry has ever been written”, and went on to say of her New Year Hymn that it was

touched as with the fire and bathed as in the light of sunbeams, tuned as to chords and cadences of refluent sea-music beyond reach of harp and organ, large echoes of the serene and sonorous tides of heaven

Then Professor Saintsbury comes with his vast learning, and examines Goblin Market, and reports that

The metre of the principal poem [“Goblin Market”] may be best described as a dedoggerelised Skeltonic, with the gathered music of the various metrical progress since Spenser, utilised in the place of the wooden rattling of the followers of Chaucer. There may be discerned in it the same inclination towards line irregularity which has broken out, at different times, in the Pindaric of the late seventeenth and earlier eighteenth centuries, and in the rhymelessness of Sayers earlier and of Mr. Arnold later.

And then there is Sir Walter Raleigh:

I think she is the best poet alive. . . . The worst of it is you cannot lecture on really pure poetry any more than you can talk about the ingredients of pure water — it is adulterated, methylated, sanded poetry that makes the best lectures. The only thing that Christina makes me want to do, is cry, not lecture.

It would appear, then, that there are at least three schools of criticism: the refluent sea-music school; the line-irregularity school, and the school that bids one not criticise but cry. This is confusing; if we follow them all we shall only come to grief. Better perhaps read for oneself, expose the mind bare to the poem, and transcribe in all its haste and imperfection whatever may be the result of the impact. In this case it might run something as follows: O Christina Rossetti, I have humbly to confess that though I know many of your poems by heart, I have not read your works from cover to cover. I have not followed your course and traced your development. I doubt indeed that you developed very much. You were an instinctive poet. You saw the world from the same angle always. Years and the traffic of the mind with men and books did not affect you in the least. You carefully ignored any book that could shake your faith or any human being who could trouble your instincts. You were wise perhaps. Your instinct was so sure, so direct, so intense that it produced poems that sing like music in one’s ears — like a melody by Mozart or an air by Gluck. Yet for all its symmetry, yours was a complex song. When you struck your harp many strings sounded together. Like all instinctives you had a keen sense of the visual beauty of the world. Your poems are full of gold dust and “sweet geraniums’ varied brightness”; your eye noted incessantly how rushes are “velvet-headed”, and lizards have a “strange metallic mail”— your eye, indeed, observed with a sensual pre-Raphaelite intensity that must have surprised Christina the Anglo-Catholic. But to her you owed perhaps the fixity and sadness of your muse. The pressure of a tremendous faith circles and clamps together these little songs. Perhaps they owe to it their solidity. Certainly they owe to it their sadness — your God was a harsh God, your heavenly crown was set with thorns. No sooner have you feasted on beauty with your eyes than your mind tells you that beauty is vain and beauty passes. Death, oblivion, and rest lap round your songs with their dark wave. And then, incongruously, a sound of scurrying and laughter is heard. There is the patter of animals’ feet and the odd guttural notes of rooks and the snufflings of obtuse furry animals grunting and nosing. For you were not a pure saint by any means. You pulled legs; you tweaked noses. You were at war with all humbug and pretence. Modest as you were, still you were drastic, sure of your gift, convinced of your vision. A firm hand pruned your lines; a sharp ear tested their music. Nothing soft, otiose, irrelevant cumbered your pages. In a word, you were an artist. And thus was kept open, even when you wrote idly, tinkling bells for your own diversion, a pathway for the descent of that fiery visitant who came now and then and fused your lines into that indissoluble connection which no hand can put asunder:

But bring me poppies brimmed with sleepy death

And ivy choking what it garlandeth

And primroses that open to the moon.

Indeed so strange is the constitution of things, and so great the miracle of poetry, that some of the poems you wrote in your little back room will be found adhering in perfect symmetry when the Albert Memorial is dust and tinsel. Our remote posterity will be singing:

When I am dead, my dearest,

or:

My heart is like a singing bird,

when Torrington Square is a reef of coral perhaps and the fishes shoot in and out where your bedroom window used to be; or perhaps the forest will have reclaimed those pavements and the wombat and the ratel will be shuffling on soft, uncertain feet among the green undergrowth that will then tangle the area railings. In view of all this, and to return to your biography, had I been present when Mrs. Virtue Tebbs gave her party, and had a short elderly woman in black risen to her feet and advanced to the middle of the room, I should certainly have committed some indiscretion — have broken a paper-knife or smashed a tea-cup in the awkward ardour of my admiration when she said, “I am Christina Rossetti”.

.jpg)

Virginia Woolf: The Common Reader, Second Series

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Rossetti, Christina, Woolf, Virginia

.jpg)

Algernon Charles Swinburne

(1873-1909)

Autumn And Winter

Three months bade wane and wax the wintering moon

Between two dates of death, while men were fain

Yet of the living light that all too soon

Three months bade wane.

Cold autumn, wan with wrath of wind and rain,

Saw pass a soul sweet as the sovereign tune

That death smote silent when he smote again.

First went my friend, in life’s mid light of noon,

Who loved the lord of music: then the strain

Whence earth was kindled like as heaven in June

Three months bade wane.

A herald soul before its master’s flying

Touched by some few moons first the darkling goal

Where shades rose up to greet the shade, espying

A herald soul;

Shades of dead lords of music, who control

Men living by the might of men undying,

With strength of strains that make delight of dole.

The deep dense dust on death’s dim threshold lying

Trembled with sense of kindling sound that stole

Through darkness, and the night gave ear, descrying

A herald soul.

One went before, one after, but so fast

They seem gone hence together, from the shore

Whence we now gaze: yet ere the mightier passed

One went before;

One whose whole heart of love, being set of yore

On that high joy which music lends us, cast

Light round him forth of music’s radiant store.

Then went, while earth on winter glared aghast,

The mortal god he worshipped, through the door

Wherethrough so late, his lover to the last,

One went before.

A star had set an hour before the sun

Sank from the skies wherethrough his heart’s pulse yet

Thrills audibly: but few took heed, or none,

A star had set.

All heaven rings back, sonorous with regret,

The deep dirge of the sunset: how should one

Soft star be missed in all the concourse met?

But, O sweet single heart whose work is done,

Whose songs are silent, how should I forget

That ere the sunset’s fiery goal was won

A star had set?

Ton van Kempen photos: Autumn 5

A.C. Swinburne poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: 4SEASONS#Autumn, Archive S-T, Swinburne, Algernon Charles, Ton van Kempen Photos

.jpg)

Dante Gabriel Rossetti

(1828-1882)

Autumn Song

Know’st thou not at the fall of the leaf

How the heart feels a languid grief

Laid on it for a covering,

And how sleep seems a goodly thing

In Autumn at the fall of the leaf?

And how the swift beat of the brain

Falters because it is in vain,

In Autumn at the fall of the leaf

Knowest thou not? and how the chief

Of joys seems–not to suffer pain?

Know’st thou not at the fall of the leaf

How the soul feels like a dried sheaf

Bound up at length for harvesting,

And how death seems a comely thing

In Autumn at the fall of the leaf?

Ton van Kempen photos: Autumn 3

D.G. Rossetti poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: *The Pre-Raphaelites Archive, 4SEASONS#Autumn, Archive Q-R, Rossetti, Dante Gabriel, Ton van Kempen Photos

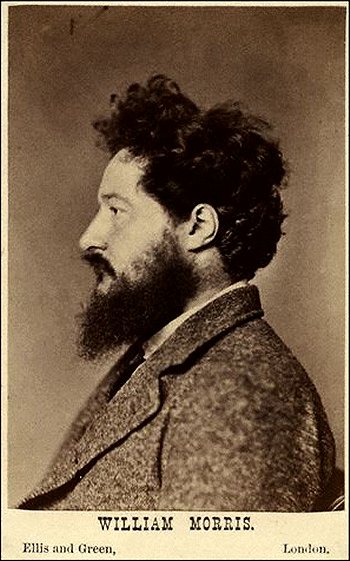

William Morris

(1834-1896)

Spring’s Bedfellow

Spring went about the woods to-day,

The soft-foot winter-thief,

And found where idle sorrow lay

‘Twixt flower and faded leaf.

She looked on him, and found him fair

For all she had been told;

She knelt adown beside him there,

And sang of days of old.

His open eyes beheld her nought,

Yet ‘gan his lips to move;

But life and deeds were in her thought,

And he would sing of love.

So sang they till their eyes did meet,

And faded fear and shame;

More bold he grew, and she more sweet,

Until they sang the same.

Until, say they who know the thing,

Their very lips did kiss,

And Sorrow laid abed with Spring

Begat an earthly bliss.

![]()

William Morris poetry

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: *The Pre-Raphaelites Archive, 4SEASONS#Spring, Archive M-N, Archive M-N, Morris, William

W i l l i a m M o r r i s

(1834-1896)

Mother and Son

Now sleeps the land of houses,

and dead night holds the street,

And there thou liest, my baby,

and sleepest soft and sweet;

My man is away for awhile,

but safe and alone we lie,

And none heareth thy breath but thy mother,

and the moon looking down from the sky

On the weary waste of the town,

as it looked on the grass-edged road

Still warm with yesterday’s sun,

when I left my old abode;

Hand in hand with my love,

that night of all nights in the year;

When the river of love o’erflowed

and drowned all doubt and fear,

And we two were alone in the world,

and once if never again,

We knew of the secret of earth

and the tale of its labour and pain.

Lo amidst London I lift thee,

and how little and light thou art,

And thou without hope or fear

thou fear and hope of my heart!

Lo here thy body beginning,

O son, and thy soul and thy life;

But how will it be if thou livest,

and enterest into the strife,

And in love we dwell together

when the man is grown in thee,

When thy sweet speech I shall hearken,

and yet ‘twixt thee and me

Shall rise that wall of distance,

that round each one doth grow,

And maketh it hard and bitter

each other’s thought to know.

Now, therefore, while yet thou art little

and hast no thought of thine own,

I will tell thee a word of the world;

of the hope whence thou hast grown;

Of the love that once begat thee,

of the sorrow that hath made

Thy little heart of hunger,

and thy hands on my bosom laid.

Then mayst thou remember hereafter,

as whiles when people say

All this hath happened before

in the life of another day;

So mayst thou dimly remember

this tale of thy mother’s voice,

As oft in the calm of dawning

I have heard the birds rejoice,

As oft I have heard the storm-wind

go moaning through the wood;

And I knew that earth was speaking,

and the mother’s voice was good.

Now, to thee alone will I tell it

that thy mother’s body is fair,

In the guise of the country maidens

Who play with the sun and the air;

Who have stood in the row of the reapers

in the August afternoon,

Who have sat by the frozen water

in the high day of the moon,

When the lights of the Christmas feasting

were dead in the house on the hill,

And the wild geese gone to the salt-marsh

had left the winter still.

Yea, I am fair, my firstling;

if thou couldst but remember me!

The hair that thy small hand clutcheth

is a goodly sight to see;

I am true, but my face is a snare;

soft and deep are my eyes,

And they seem for men’s beguiling

fulfilled with the dreams of the wise.

Kind are my lips, and they look

as though my soul had learned

Deep things I have never heard of,

my face and my hands are burned

By the lovely sun of the acres;

three months of London town

And thy birth-bed have bleached them indeed,

"But lo, where the edge of the gown"

(So said thy father) "is parting

the wrist that is white as the curd

From the brown of the hand that I love,

bright as the wing of a bird."

Such is thy mother, O firstling,

yet strong as the maidens of old,

Whose spears and whose swords were the warders

of homestead, of field and of fold.

Oft were my feet on the highway,

often they wearied the grass;

From dusk unto dusk of the summer

three times in a week would I pass

To the downs from the house on the river

through the waves of the blossoming corn.

Fair then I lay down in the even,

and fresh I arose on the morn,

And scarce in the noon was I weary.

Ah, son, in the days of thy strife,

If thy soul could but harbour a dream

of the blossom of my life!

It would be as the sunlit meadows

beheld from a tossing sea,

And thy soul should look on a vision

of the peace that is to be.

Yet, yet the tears on my cheek!

and what is this doth move

My heart to thy heart, beloved,

save the flood of yearning love?

For fair and fierce is thy father,

and soft and strange are his eyes

That look on the days that shall be

with the hope of the brave and the wise.

It was many a day that we laughed,

as over the meadows we walked,

And many a day I hearkened

and the pictures came as he talked;

It was many a day that we longed,

and we lingered late at eve

Ere speech from speech was sundered,

and my hand his hand could leave.

Then I wept when I was alone,

and I longed till the daylight came;

And down the stairs I stole,

and there was our housekeeping dame

(No mother of me, the foundling)

kindling the fire betimes

Ere the haymaking folk went forth

to the meadows down by the limes;

All things I saw at a glance;

the quickening fire-tongues leapt

Through the crackling heap of sticks,

and the sweet smoke up from it crept,

And close to the very hearth

the low sun flooded the floor,

And the cat and her kittens played

in the sun by the open door.

The garden was fair in the morning,

and there in the road he stood

Beyond the crimson daisies

and the bush of southernwood.

Then side by side together

through the grey-walled place we went,

And O the fear departed,

and the rest and sweet content!

Son, sorrow and wisdom he taught me,

and sore I grieved and learned

As we twain grew into one;

and the heart within me burned

With the very hopes of his heart.

Ah, son, it is piteous,

But never again in my life

shall I dare to speak to thee thus;

So may these lonely words

about thee creep and cling,

These words of the lonely night

in the days of our wayfaring.

Many a child of woman

to-night is born in the town,

The desert of folly and wrong;

and of what and whence are they grown?

Many and many an one

of wont and use is born;

For a husband is taken to bed

as a hat or a ribbon is worn.

Prudence begets her thousands;

"good is a housekeeper’s life,

So shall I sell my body

that I may be matron and wife."

"And I shall endure foul wedlock

and bear the children of need."

Some are there born of hate,

many the children of greed.

"I, I too can be wedded,

though thou my love hast got."

"I am fair and hard of heart,

and riches shall be my lot."

And all these are the good and the happy,

on whom the world dawns fair.

O son, when wilt thou learn

of those that are born of despair,

As the fabled mud of the Nile

that quickens under the sun

With a growth of creeping things,

half dead when just begun?

E’en such is the care of Nature

that man should never die,

Though she breed of the fools of the earth,

and the dregs of the city sty.

But thou, O son, O son,

of very love wert born,

When our hope fulfilled bred hope,

and fear was a folly outworn.

On the eve of the toil and the battle

all sorrow and grief we weighed,

We hoped and we were not ashamed,

we knew and we were not afraid.

Now waneth the night and the moon;

ah, son, it is piteous

That never again in my life

shall I dare to speak to thee thus.

But sure from the wise and the simple

shall the mighty come to birth;

And fair were my fate, beloved,

if I be yet on the earth

When the world is awaken at last,

and from mouth to mouth they tell

Of thy love and thy deeds and thy valour,

and thy hope that nought can quell.

.jpg)

William Morris poetry

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Morris, William

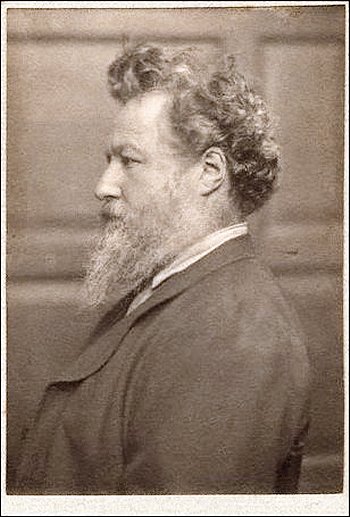

William Morris

(1834-1896)

Meeting in Winter

Winter in the world it is,

Round about the unhoped kiss

Whose dream I long have sorrowed o’er;

Round about the longing sore,

That the touch of thee shall turn

Into joy too deep to burn.

Round thine eyes and round thy mouth

Passeth no murmur of the south,

When my lips a little while

Leave thy quivering tender smile,

As we twain, hand holding hand,

Once again together stand.

Sweet is that, as all is sweet;

For the white drift shalt thou meet,

Kind and cold-cheeked and mine own,

Wrapped about with deep-furred gown

In the broad-wheeled chariot:

Then the north shall spare us not;

The wide-reaching waste of snow

Wilder, lonelier yet shall grow

As the reddened sun falls down.

But the warders of the town,

When they flash the torches out

O’er the snow amid their doubt,

And their eyes at last behold

Thy red-litten hair of gold;

Shall they open, or in fear

Cry, “Alas! What cometh here?

Whence hath come this Heavenly

To tell of all the world undone?”

They shall open, and we shall see

The long street litten scantily

By the long stream of light before

The guest-hall’s half-open door;

And our horses’ bells shall cease

As we reach the place of peace;

Thou shalt tremble, as at last

The worn threshold is o’er-past,

And the fire-light blindeth thee:

Trembling shalt thou cling to me

As the sleepy merchants stare

At thy cold hands slim and fair,

Thy soft eyes and happy lips

Worth all lading of their ships.

O my love, how sweet and sweet

That first kissing of thy feet,

When the fire is sunk alow,

And the hall made empty now

Groweth solemn, dim and vast!

O my love, the night shall last

Longer than men tell thereof

Laden with our lonely love!

William Morris poetry

kempis poetry magazine

More in: 4SEASONS#Winter, Archive M-N, Morris, William

.jpg)

Fleursdumal.nl magazine Gallery of Poets’ Portraits:

Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882) &

Elizabeth (Lizzy) Siddal (1829-1862)

fleursdumal.nl magazine – magazine for art & literature

More in: *The Pre-Raphaelites Archive, Poets' Portraits

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature