Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Hans Hermans© photos: landscape

(101 – lac du der F)

# more on website hans hermans photos

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: FDM Art Gallery, Hans Hermans Photos, Photography

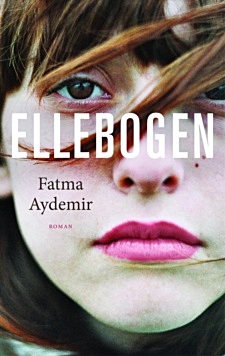

Een jonge Turks-Duitse duwt een Duitser voor de metro. Hij sterft, zij voelt geen berouw. Warm en vurig vertelt Fatma Aydemir over diegenen die tussen culturen en landen leven en hun plaats op de wereld zoeken.

Ze is zeventien. Ze is in Berlijn geboren. Ze heet Hazal Akgündüz. Er werd haar beloofd dat ze alles kon worden wat ze maar wou. Maar steeds opnieuw moet ze opboksen tegen vooroordelen en discriminatie.

Ze is zeventien. Ze is in Berlijn geboren. Ze heet Hazal Akgündüz. Er werd haar beloofd dat ze alles kon worden wat ze maar wou. Maar steeds opnieuw moet ze opboksen tegen vooroordelen en discriminatie.

Tot ze op een nacht te veel gedronken heeft en een Duitse student die haar uitdaagt, voor de metro duwt. Als de politie haar achterna zit vlucht Hazal naar Istanbul, waar ze nooit eerder is geweest. Ze ziet op krantenfoto’s de grijns op haar gezicht terwijl ze de jongen aanvalt maar voelt geen berouw.

Ellebogen is een urgent, gewaagd en onverzoenlijk verhaal over de woede van een migrantendochter in een Europa waar ze zich nooit helemaal thuis voelde.

Fatma Aydemir (1986) is de dochter van Turkse gastarbeiders. Ze heeft Duits en Amerikanistiek gestudeerd en werkt als redacteur voor de krant Taz. Haar controversiële debuutroman Ellebogen werd meteen een fenomeen in Duitsland. Op 11 maart 2017 kopte de Volkskrant al: ‘Over dit debuut schrijven alle Duitse kwaliteitskranten’. Aydemir neemt met regelmaat deel aan het publieke debat over integratie in Duitsland.

“‘Ellebogen is een stomp in de maag. Of beter gezegd, twee. Eén voor de misogyne Turkse gemeenschap. En één voor de huichelarij van onze o zo liberale samenleving.’” – Süddeutsche Zeitung

Titel: Ellebogen

Auteur: Fatma Aydemir

Vertaler(s): Marcel Misset

240 pagina’s

€ 19,99

Uitgever: Signatuur

2017

ISBN: 978-90-5672-590-7

NUR: 302

new books

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive A-B, Art & Literature News, Galerie Deutschland

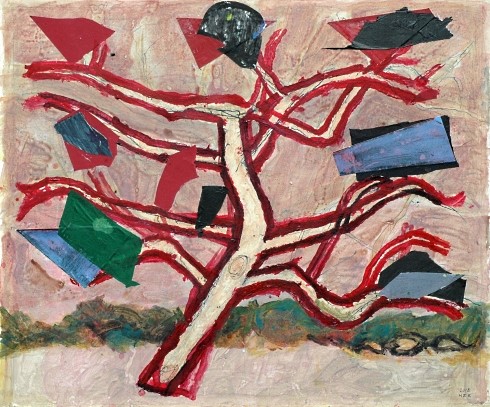

Hans Ebeling Koning

Appelboom (Apple tree)

Hans Ebeling Koning (1931) received his education at AKI in Enschede where he later became a teacher in drawing and painting. His work is represented in many public and private collections including Museum Henriette Polak in Zutphen, Rijksmuseum Twente and the Museum of Modern Art in Arnhem.

Hans Ebeling Koning © 2018

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Art & Literature News, Exhibition Archive, FDM Art Gallery, Hans Ebeling Koning

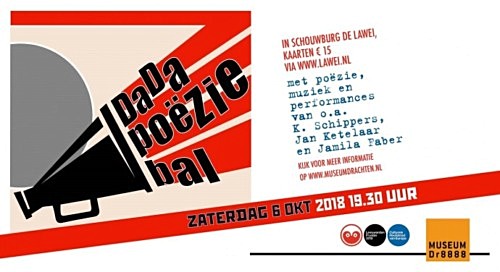

Op zaterdag 6 oktober organiseert Museum Dr8888 (Drachten) het Dada Poëziebal in Schouwburg De Lawei.

Vanaf 19.30 uur presenteert het museum in de Kleine Zaal een verrassend en onvoorspelbaar programma met poëzie, performances, muziek, beeld en dans.

Optredens worden verzorgd door o.a. K. Schippers, Astrid Lampe, Nyk de Vries, Jan Ketelaar, Meindert Talma en Andries de Jong. Het Poëziebal is onderdeel van het buitenprogramma van Museum Dr8888 en vindt plaats in het kader van Leeuwarden-Friesland 2018.

De avond wordt een beleving op zich en laat zich het best omschrijven als extravagant, intiem, verrassend en een tikkeltje rebels. Het Dada Poëziebal begint om 19.30 uur en vindt plaats in de Kleine Zaal van De Lawei. Het wordt een avondvullend programma met een divers palet aan multidisciplinaire performances waarin tegelijkertijd en op meerdere plekken tegelijk wordt geprogrammeerd. Optredens worden verzorgd door K. Schippers, Astrid Lampe, Jan Ketelaar, Alison Isadora, Jaap Blonk, Tim Schouten, Felicity Provan en Laura Polence, studenten Beeld en Taal van de Gerrit Rietveld Academie, Meindert Talma, Tijdelijke Toon, Bram Zielman, Andries de Jong, Leendert Vooijce, Nyk de Vries, Redactielokaal met Jamila Faber en Arjan Hut, Natasja Hoekstra en dansers en Willie Darktrousers.

Presentator van de avond: Karel Hermans. Regie van de avond is in handen van Janneke de Haan i.s.m. Sanne van Balen.

# Kaarten zijn verkrijgbaar via: www.lawei.nl

Dada Poëziebal met o.a. Jan Ketelaar, K. Schippers en Astrid Lampe in Schouwburg De Lawei in Drachten op zaterdag 6 oktober 2018

more dada

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Antony Kok, Art & Literature News, DADA, Dada, Dadaïsme, De Stijl, Doesburg, Theo van, Evert en Thijs Rinsema, K. Schippers, Kok, Antony, Kurt Schwitters, Kurt Schwitters, Performing arts, Schippers, K., Schwitters, Kurt, THEATRE, Theo van Doesburg, Tzara, Tristan, Visual & Concrete Poetry, Werkman, Hendrik Nicolaas

“One of the strongest and most vital accounts of a life ever set down on paper. . . . Genet has dramatized the story of his own life with a power and vision which take the breath away. The Thief’s Journal will undoubtedly establish Genet as one of the most daring literary figures of all time.” — The New York Post

The Thief’s Journal is perhaps Jean Genet’s most authentically biographical novel, personifying his quest for spiritual glory through the pursuit of evil. Writing in the intensely lyrical prose style that is his trademark, the man Jean Cocteau dubbed France’s “Black Prince of Letters” here reconstructs his early adult years—time he spent as a petty criminal and vagabond, traveling through Spain and Antwerp, occasionally border hopping across the rest of Europe, always one step ahead of the authorities.

The Thief’s Journal is perhaps Jean Genet’s most authentically biographical novel, personifying his quest for spiritual glory through the pursuit of evil. Writing in the intensely lyrical prose style that is his trademark, the man Jean Cocteau dubbed France’s “Black Prince of Letters” here reconstructs his early adult years—time he spent as a petty criminal and vagabond, traveling through Spain and Antwerp, occasionally border hopping across the rest of Europe, always one step ahead of the authorities.

The infamous playwright, poet, novelist, and criminal, Jean Genet, was born December 19th, 1910, in France. Genet’s mother, who was a young prostitute at the time of his birth, gave him up for adoption to a provincial family. By the age of fifteen, for repeated misdemeanors, Genet was incarcerated for three years, after which he joined the French Foreign Legion. He was dishonorably discharged for “lewd acts”, henceforth spending the next several years traveling around Europe, at times as a prostitute. In 1937 he came to Paris, where again he was arrested and imprisoned for vagabondage. It was in prison, though, that Genet personally funded his first novel Our Lady of the Flowers (1944).

After being released from prison, Genet sought out the avant-garde writer, Jean Cocteau, who was impressed by Genet’s work, and even petitioned the French president, along with Jean-Paul Sartre, to exonerate Genet, after being faced with a life sentence. Genet became associated with the Theatre of Cruelty, which his most famous pieces became associated with, for example, The Maids (1949), Deathwatch (1949), The Balcony (1956), and The Blacks (1958). Other celebrated works of Genet include the novel, A Thief’s Journal (1949), about his experiences in prison, and The Screens (1963), a biting political play about the Algerian War of Independence. Genet died of throat cancer in 1986.

Published in 1964, and again on August 21, 2018: Jean Genet’s The Thief’s Journal, with a new intro by Patti Smith

The Thief’s Journal

by Jean Genet

With a New Introduction by Patti Smith

Translated from French by Bernard Frechtman

Foreword by Jean-Paul Sartre

Imprint Grove Paperback

Grove Press

272 pages

Publication Date August 21, 2018

ISBN-13 978-0-8021-2827-0

Dimensions 5.5″ x 8.25″

US List Price $16.00

new books

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Archive G-H, Art & Literature News, Jean Genet, Jean-Paul Sartre, Smith, Patti

Het grootste poëziefeest van het jaar kent in 2018, op 29 september, zijn 36ste editie, in de vertrouwde Grote Zaal van TivoliVredenburg in Utrecht. De beste Nederlandstalige dichters, van debutant tot veteraan, bieden het publiek een poëtische marathon die zijn weerga niet kent.

En dan zijn er nog muzikale entr’actes, die de dichters gedurende de avond in razend tempo afwisselen.

De Nacht van de Poëzie betovert haar bezoekers tot diep in de nacht en laat ze met een glimlach huiswaarts keren.

Onder de dichters bevinden zich dit jaar onder meer ‘nachtveteraan’ Judith Herzberg, P.C. Hooftprijswinnaar Willem Jan Otten en Radna Fabias, die dit jaar de C. Buddingh’-prijs voor het beste debuut in ontvangst mocht nemen. Na ruim duizend optredens, maakt Arthur Japin zijn debuut op De Nacht naar aanleiding van zijn bundel Nachtkaravaan, met liedjes en gedichten. Verder zijn er dichters die schrijven over dwaallichten en vloekschriften, buigt de een zich over het paringsritueel en de ander over de begrafenis van de mannen. Iemand zegt: ‘Ik was een hond’, een ander begint een oefening in het alleen lopen; er zijn lofzangen op een kapstok en een röntgenfotomodel. ‘Zo kan het niet langer,’ foetert de een, ‘het leven deugt, althans, op onderdelen’, besluit de ander. De bundeltitels van de optredende dichters tijdens deze nacht beloven alvast een bonte parade van taalgiganten, fluisterdichters, tongbrekers en woordacrobaten.

De presentatie van de avond is als vanouds in handen van het Nachtduo Piet Piryns & Ester Naomi Perquin. In de aanloop naar De Nacht worden steeds meer dichters en muzikanten bekend gemaakt.

Tip: met een Nacht-de-Luxe-kaart ontloop je de Nachtelijke Volksverhuizing, zoals Ingmar Heytze het ooit noemde, waarbij je nooit zeker weet of je stoel nog vrij is.

Dit seizoen is er ook weer een KinderNacht van de Poëzie! Kinderen kunnen samen met hun ouders, familie en vriendjes luisteren naar grappige gedichten en raadselachtige rijmpjes.

Radna Fabias – Ester Naomi Perquin – Arthur Japin – Arno Van Vlierberghe – The Tallest Man On Earth – Kreek Daey Ouwens – Rodaan Al-Galidi – Moya De Feyter – Ted van Lieshout – Piet Piryns – Tsead Bruinja – Thomas Möhlmann – Anton Korteweg – Anneke Claus – Benno Barnard – Paul Bogaert – Delphine Lecompte – Willem Thies – Vicky Francken – Judith Herzberg

36ste Nacht van de Poëzie

Het grootste poëziefeest van het jaar

zaterdag 29 september 2018

Tijd: 20:00 uur

Poëzie

Nederlands

TivoliVredenburg

Vredenburgkade 11

3511 WC Utrecht

# Meer informatie op website nachtvandepoezie

36ste Nacht van de Poëzie

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: # Music Archive, #Archive Concrete & Visual Poetry, #Editors Choice Archiv, Art & Literature News, Heytze, Ingmar, Lecompte, Delphine, Nacht van de Poëzie, STREET POETRY, THEATRE

The Music on the Hill

Sylvia Seltoun ate her breakfast in the morning-room at Yessney with a pleasant sense of ultimate victory, such as a fervent Ironside might have permitted himself on the morrow of Worcester fight. She was scarcely pugnacious by temperament, but belonged to that more successful class of fighters who are pugnacious by circumstance.

Fate had willed that her life should be occupied with a series of small struggles, usually with the odds slightly against her, and usually she had just managed to come through winning. And now she felt that she had brought her hardest and certainly her most important struggle to a successful issue. To have married Mortimer Seltoun, “Dead Mortimer” as his more intimate enemies called him, in the teeth of the cold hostility of his family, and in spite of his unaffected indifference to women, was indeed an achievement that had needed some determination and adroitness to carry through; yesterday she had brought her victory to its concluding stage by wrenching her husband away from Town and its group of satellite watering-places and “settling him down,” in the vocabulary of her kind, in this remote wood-girt manor farm which was his country house.

Fate had willed that her life should be occupied with a series of small struggles, usually with the odds slightly against her, and usually she had just managed to come through winning. And now she felt that she had brought her hardest and certainly her most important struggle to a successful issue. To have married Mortimer Seltoun, “Dead Mortimer” as his more intimate enemies called him, in the teeth of the cold hostility of his family, and in spite of his unaffected indifference to women, was indeed an achievement that had needed some determination and adroitness to carry through; yesterday she had brought her victory to its concluding stage by wrenching her husband away from Town and its group of satellite watering-places and “settling him down,” in the vocabulary of her kind, in this remote wood-girt manor farm which was his country house.

“You will never get Mortimer to go,” his mother had said carpingly, “but if he once goes he’ll stay; Yessney throws almost as much a spell over him as Town does. One can understand what holds him to Town, but Yessney —” and the dowager had shrugged her shoulders.

There was a sombre almost savage wildness about Yessney that was certainly not likely to appeal to town-bred tastes, and Sylvia, notwithstanding her name, was accustomed to nothing much more sylvan than “leafy Kensington.” She looked on the country as something excellent and wholesome in its way, which was apt to become troublesome if you encouraged it overmuch. Distrust of town-life had been a new thing with her, born of her marriage with Mortimer, and she had watched with satisfaction the gradual fading of what she called “the Jermyn-street-look” in his eyes as the woods and heather of Yessney had closed in on them yesternight. Her will-power and strategy had prevailed; Mortimer would stay.

Outside the morning-room windows was a triangular slope of turf, which the indulgent might call a lawn, and beyond its low hedge of neglected fuchsia bushes a steeper slope of heather and bracken dropped down into cavernous combes overgrown with oak and yew. In its wild open savagery there seemed a stealthy linking of the joy of life with the terror of unseen things. Sylvia smiled complacently as she gazed with a School-of-Art appreciation at the landscape, and then of a sudden she almost shuddered.

“It is very wild,” she said to Mortimer, who had joined her; “one could almost think that in such a place the worship of Pan had never quite died out.”

“The worship of Pan never has died out,” said Mortimer. “Other newer gods have drawn aside his votaries from time to time, but he is the Nature–God to whom all must come back at last. He has been called the Father of all the Gods, but most of his children have been stillborn.”

Sylvia was religious in an honest vaguely devotional kind of way, and did not like to hear her beliefs spoken of as mere aftergrowths, but it was at least something new and hopeful to hear Dead Mortimer speak with such energy and conviction on any subject.

“You don’t really believe in Pan?” she asked incredulously.

“I’ve been a fool in most things,” said Mortimer quietly, “but I’m not such a fool as not to believe in Pan when I’m down here. And if you’re wise you won’t disbelieve in him too boastfully while you’re in his country.”

It was not till a week later, when Sylvia had exhausted the attractions of the woodland walks round Yessney, that she ventured on a tour of inspection of the farm buildings. A farmyard suggested in her mind a scene of cheerful bustle, with churns and flails and smiling dairymaids, and teams of horses drinking knee-deep in duck-crowded ponds. As she wandered among the gaunt grey buildings of Yessney manor farm her first impression was one of crushing stillness and desolation, as though she had happened on some lone deserted homestead long given over to owls and cobwebs; then came a sense of furtive watchful hostility, the same shadow of unseen things that seemed to lurk in the wooded combes and coppices. From behind heavy doors and shuttered windows came the restless stamp of hoof or rasp of chain halter, and at times a muffled bellow from some stalled beast. From a distant corner a shaggy dog watched her with intent unfriendly eyes; as she drew near it slipped quietly into its kennel, and slipped out again as noiselessly when she had passed by. A few hens, questing for food under a rick, stole away under a gate at her approach. Sylvia felt that if she had come across any human beings in this wilderness of barn and byre they would have fled wraith-like from her gaze. At last, turning a corner quickly, she came upon a living thing that did not fly from her. Astretch in a pool of mud was an enormous sow, gigantic beyond the town-woman’s wildest computation of swine-flesh, and speedily alert to resent and if necessary repel the unwonted intrusion. It was Sylvia’s turn to make an unobtrusive retreat. As she threaded her way past rickyards and cowsheds and long blank walls, she started suddenly at a strange sound — the echo of a boy’s laughter, golden and equivocal. Jan, the only boy employed on the farm, a towheaded, wizen-faced yokel, was visibly at work on a potato clearing half-way up the nearest hill-side, and Mortimer, when questioned, knew of no other probable or possible begetter of the hidden mockery that had ambushed Sylvia’s retreat. The memory of that untraceable echo was added to her other impressions of a furtive sinister “something” that hung around Yessney.

Of Mortimer she saw very little; farm and woods and trout-streams seemed to swallow him up from dawn till dusk. Once, following the direction she had seen him take in the morning, she came to an open space in a nut copse, further shut in by huge yew trees, in the centre of which stood a stone pedestal surmounted by a small bronze figure of a youthful Pan. It was a beautiful piece of workmanship, but her attention was chiefly held by the fact that a newly cut bunch of grapes had been placed as an offering at its feet. Grapes were none too plentiful at the manor house, and Sylvia snatched the bunch angrily from the pedestal. Contemptuous annoyance dominated her thoughts as she strolled slowly homeward, and then gave way to a sharp feeling of something that was very near fright; across a thick tangle of undergrowth a boy’s face was scowling at her, brown and beautiful, with unutterably evil eyes. It was a lonely pathway, all pathways round Yessney were lonely for the matter of that, and she sped forward without waiting to give a closer scrutiny to this sudden apparition. It was not till she had reached the house that she discovered that she had dropped the bunch of grapes in her flight.

“I saw a youth in the wood today,” she told Mortimer that evening, “brown-faced and rather handsome, but a scoundrel to look at. A gipsy lad, I suppose.”

“A reasonable theory,” said Mortimer, “only there aren’t any gipsies in these parts at present.”

“Then who was he?” asked Sylvia, and as Mortimer appeared to have no theory of his own, she passed on to recount her finding of the votive offering.

“I suppose it was your doing,” she observed; “it’s a harmless piece of lunacy, but people would think you dreadfully silly if they knew of it.”

“Did you meddle with it in any way?” asked Mortimer.

“I— I threw the grapes away. It seemed so silly,” said Sylvia, watching Mortimer’s impassive face for a sign of annoyance.

“I don’t think you were wise to do that,” he said reflectively. “I’ve heard it said that the Wood Gods are rather horrible to those who molest them.”

“Horrible perhaps to those that believe in them, but you see I don’t,” retorted Sylvia.

“All the same,” said Mortimer in his even, dispassionate tone, “I should avoid the woods and orchards if I were you, and give a wide berth to the horned beasts on the farm.”

It was all nonsense, of course, but in that lonely wood-girt spot nonsense seemed able to rear a bastard brood of uneasiness.

“Mortimer,” said Sylvia suddenly, “I think we will go back to Town some time soon.”

Her victory had not been so complete as she had supposed; it had carried her on to ground that she was already anxious to quit.

“I don’t think you will ever go back to Town,” said Mortimer. He seemed to be paraphrasing his mother’s prediction as to himself.

Sylvia noted with dissatisfaction and some self-contempt that the course of her next afternoon’s ramble took her instinctively clear of the network of woods. As to the horned cattle, Mortimer’s warning was scarcely needed, for she had always regarded them as of doubtful neutrality at the best: her imagination unsexed the most matronly dairy cows and turned them into bulls liable to “see red” at any moment. The ram who fed in the narrow paddock below the orchards she had adjudged, after ample and cautious probation, to be of docile temper; today, however, she decided to leave his docility untested, for the usually tranquil beast was roaming with every sign of restlessness from corner to corner of his meadow. A low, fitful piping, as of some reedy flute, was coming from the depth of a neighbouring copse, and there seemed to be some subtle connection between the animal’s restless pacing and the wild music from the wood. Sylvia turned her steps in an upward direction and climbed the heather-clad slopes that stretched in rolling shoulders high above Yessney. She had left the piping notes behind her, but across the wooded combes at her feet the wind brought her another kind of music, the straining bay of hounds in full chase. Yessney was just on the outskirts of the Devon-and-Somerset country, and the hunted deer sometimes came that way. Sylvia could presently see a dark body, breasting hill after hill, and sinking again and again out of sight as he crossed the combes, while behind him steadily swelled that relentless chorus, and she grew tense with the excited sympathy that one feels for any hunted thing in whose capture one is not directly interested. And at last he broke through the outermost line of oak scrub and fern and stood panting in the open, a fat September stag carrying a well-furnished head. His obvious course was to drop down to the brown pools of Undercombe, and thence make his way towards the red deer’s favoured sanctuary, the sea. To Sylvia’s surprise, however, he turned his head to the upland slope and came lumbering resolutely onward over the heather. “It will be dreadful,” she thought, “the hounds will pull him down under my very eyes.” But the music of the pack seemed to have died away for a moment, and in its place she heard again that wild piping, which rose now on this side, now on that, as though urging the failing stag to a final effort. Sylvia stood well aside from his path, half hidden in a thick growth of whortle bushes, and watched him swing stiffly upward, his flanks dark with sweat, the coarse hair on his neck showing light by contrast. The pipe music shrilled suddenly around her, seeming to come from the bushes at her very feet, and at the same moment the great beast slewed round and bore directly down upon her. In an instant her pity for the hunted animal was changed to wild terror at her own danger; the thick heather roots mocked her scrambling efforts at flight, and she looked frantically downward for a glimpse of oncoming hounds. The huge antler spikes were within a few yards of her, and in a flash of numbing fear she remembered Mortimer’s warning, to beware of horned beasts on the farm. And then with a quick throb of joy she saw that she was not alone; a human figure stood a few paces aside, knee-deep in the whortle bushes.

“Drive it off!” she shrieked. But the figure made no answering movement.

The antlers drove straight at her breast, the acrid smell of the hunted animal was in her nostrils, but her eyes were filled with the horror of something she saw other than her oncoming death. And in her ears rang the echo of a boy’s laughter, golden and equivocal.

The Music on the Hill

From ‘The Chronicles of Clovis’

by Saki (H. H. Munro)

(1870 – 1916)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Saki, Saki

Running Upon The Wires is Kate Tempest’s first book of free-standing poetry since the acclaimed Hold Your Own.

In a beautifully varied series of formal poems, spoken songs, fragments, vignettes and ballads, Tempest charts the heartbreak at the end of one relationship and the joy at the beginning of a new love; but also tells us what happens in between, when the heart is pulled both ways at once.

In a beautifully varied series of formal poems, spoken songs, fragments, vignettes and ballads, Tempest charts the heartbreak at the end of one relationship and the joy at the beginning of a new love; but also tells us what happens in between, when the heart is pulled both ways at once.

Running Upon The Wires is, in a sense, a departure from her previous work, and unashamedly personal and intimate in its address – but will also confirm Tempest’s role as one of our most important poetic truth–tellers: it will be no surprise to readers to discover that she’s no less a direct and unflinching observer of matters of the heart than she is of social and political change. Running Upon The Wires is a heartbreaking, moving and joyous book about love, in its endings and in its beginnings.

Kate Tempest:

Running Upon The Wires

publisher: Picador

paperback

6 September 2018

ISBN 9781509830022

64 pages

£9.99

Kate Tempest was born in London in 1985. She works across the shrinking gaps of a steadily converging media industry. Equally at home within the genres of theatre, performance, poetry and music, her name now appears on album covers, poetry books, and billboard hoardings. It is fitting then, that her individual works blend elements of oral, sonic, visual and written culture.

Kate Tempest was born in London in 1985. She works across the shrinking gaps of a steadily converging media industry. Equally at home within the genres of theatre, performance, poetry and music, her name now appears on album covers, poetry books, and billboard hoardings. It is fitting then, that her individual works blend elements of oral, sonic, visual and written culture.

Her 2016 work, Let Them Eat Chaos, was published by Picador, composed for live performance and released as an album of the same name.

Kate Tempest was nominated for the Mercury Music Prize for her debut album, Everybody Down, and received the Ted Hughes Award and a Herald Angel Award for Brand New Ancients. Kate was also named a Next Generation poet in 2014.

Books by Kate Tempest

2016 Let Them Eat Chaos

2016 The Bricks that Built the Houses

2015 Hopelessly Devoted

2014 Hold Your Own

2014 Everybody Down

2013 Wasted

2012 Everything Speaks in its Own Way

Awards

2016 Costa Book Award for Best Poetry Collection (shortlist)

2014 Next Generation Poet

2013 Ted Hughes Award

new poetry

by Kate Tempest

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Archive S-T, Art & Literature News, Kate/Kae Tempest, Tempest, Kate/Kae

Mels wordt verblind door de schittering van de zon op de Wijer.

Het door het water gewitte zonlicht maakt alles wit. Het kleurt de weilanden rond het dorp wit.

Het door het water gewitte zonlicht maakt alles wit. Het kleurt de weilanden rond het dorp wit.

De rode daken zijn wit. De blauwe daken zijn zilverwit. De lichtgroene bomen zijn blinkend wit als van parelmoer. De kinderen in de straat zijn wit, allemaal in het wit gekleed, met witte schoenen en met ijskoude witte gezichten.

Het witste wit zet de tijd stil. Wit van woede is hij. Omdat ze hem allemaal hebben laten barsten.

Een wolk schuift voor de zon en laat zijn woede verdampen. De kinderen krijgen hun kleur terug. Ze hebben rode kersentrosjes rond de oren en hinkelen zingend over de stoep.

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (072)

wordt vervolgd

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

Le paranoïaque est souvent convaincant. Charismatique, même. La folie qui l’habite ne se manifeste pas au premier coup d’œil. Incapable de regarder en lui, il part de la certitude inébranlable que le mal vient toujours des autres.

Un mécanisme insensé mais qui ne perd jamais l’apparence de la raison.

Un mécanisme insensé mais qui ne perd jamais l’apparence de la raison.

Une « folie lucide » dépourvue de toute dimension morale, qui représente un danger pour la société. Car la paranoïa atteint une intensité explosive dès qu’elle sort de la pathologie individuelle pour contaminer la masse. Elle peut alors marquer l’histoire de son empreinte, du massacre des Indiens d’Amérique à la Grande Guerre en passant par les pogroms, les totalitarismes monstrueux du XXe siècle et les guerres préventives des démocraties de notre temps. Il manquait une étude globale sur ce mal collectif, à cheval entre psychiatrie et histoire.

Pour la première fois, le psychanalyste Luigi Zoja explore la dynamique, la perversité, l’absurdité mais aussi la puissance de cette contamination psychique à grande échelle. De quoi nous faire regarder d’un autre œil des événements que nous pensions connaître. Des horreurs définitivement révolues ? Rien n’est moins sûr. La lumière de la conscience n’est jamais totale, ni définitive. La paranoïa peut encore affirmer à bon droit : « L’histoire, c’est moi. »

Luigi Zoja, intellectuel italien, sociologue et avant tout psychanalyste jungien, vit et travaille à Milan ; il a notamment été président de l’Association internationale de psychologie analytique (IAAP). Dans ses nombreux ouvrages, il analyse les travers collectifs des sociétés contemporaines, en les mettant en perspective dans la longue durée culturelle. Il a publié Le Père. Le geste d’Hector envers son fils. Histoire culturelle et psychologique de la paternité (coédition Les Belles Lettres / La Compagnie du Livre rouge, 2015).

Luigi Zoja

Paranoïa.

La folie qui fait l’histoire

Traduit de l’italien par Marc Lesage

Langue: Français

Société d’édition Les Belles Lettres Paris

540 pages

Bibliographie

Livre broché

15.1 x 21.6 cm

Parution : 15/06/2018

Langue : Français

ISBN-10: 2251448152

ISBN-13: 978-2251448152

CLIL : 3378

€25,90

new books

Luigi Zoja – Paranoïa

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive Y-Z, Art & Literature News, DRUGS & DISEASE & MEDICINE & LITERATURE, Psychiatric hospitals

De jury van de Europese Literatuurprijs 2018 kent de prijs toe aan de Noorse auteur Johan Harstad en zijn Nederlandse vertalers Edith Koenders en Paula Stevens voor de roman Max, Mischa & het Tet-offensief (Podium). Schrijver en vertalers ontvangen de prijs op woensdagavond 31 oktober op het Crossing Border Festival in Den Haag.

De Europese Literatuurprijs bekroont de beste hedendaagse Europese roman die vorig jaar in Nederlandse vertaling is verschenen. De vakjury bestond dit jaar uit voorzitter Anna Enquist, schrijver en recensent Kees ’t Hart, boekhandelaren Nienke Willemsen (Literaire Boekhandel Lijnmarkt, Utrecht) en Hein van Kemenade (Boekhandel Van Kemenade & Hollaers, Breda), en literair vertaler Saskia van der Lingen (ELP-laureaat 2017).

De Europese Literatuurprijs bekroont de beste hedendaagse Europese roman die vorig jaar in Nederlandse vertaling is verschenen. De vakjury bestond dit jaar uit voorzitter Anna Enquist, schrijver en recensent Kees ’t Hart, boekhandelaren Nienke Willemsen (Literaire Boekhandel Lijnmarkt, Utrecht) en Hein van Kemenade (Boekhandel Van Kemenade & Hollaers, Breda), en literair vertaler Saskia van der Lingen (ELP-laureaat 2017).

Max, Mischa & het Tet-offensief is het verhaal van Max Hansen, die in de jaren zeventig en tachtig opgroeit in het Noorse Stavanger, waar hij uiting geeft aan zijn fascinatie voor de Vietnam-oorlog door met zijn vriendjes het Tet-offensief – de onverwachte aanval van de Vietcong op de Amerikanen – na te spelen. Als tiener verhuist hij (noodgedwongen) met zijn vader naar Amerika, naar New York. Daar probeert hij zin te geven aan zijn nieuwe bestaan samen met zijn beste vriend Mordecai, zijn geliefde Mischa en zijn oom en Vietnam-veteraan Owen, alle drie net als Max ontheemde migranten.

“Een overrompelende roman,” aldus de jury, “die de lezer meesleurt in de achtbaan van de recente geschiedenis.”

De vertalers hebben met deze duo-vertaling een tour de force geleverd, waarbij de vele verwijzingen van de auteur naar bestaande én fictieve kunstwerken, films en toneelstukken een bijzondere uitdaging vormden.

Ook zijn de juryleden onder de indruk van de kernachtige, met gevoel voor humor geformuleerde zinnen die de essentie van het leven raken, zoals op de laatste pagina van het 1.232 pagina’s tellende boek: ‘Dat alles beweging is. Stilstand bestaat niet. Er bestaan alleen te veel woorden.’

De jury heeft met deze prijs een roman willen bekronen die zij bewondert om haar briljante stijl en veelomvattendheid, een roman waarin de ‘veelheid’ als stijlfiguur dient om de onvermijdelijke loop der dingen in het leven voelbaar te maken.

Johan Harstad (Stavanger, 1979) debuteerde in 2001 met een bundel verzameld proza. Zijn debuutroman Buzz Aldrin, waar ben je gebleven? werd opgevolgd door de roman Hässelby, een David Lynch-achtig verhaal over een man die al 42 jaar bij zijn vader woont. In 2011 verscheen zijn young adult sf-roman Darlah. Voorafgaand aan zijn succesvolle roman Buzz Aldrin, waar ben je gebleven? publiceerde de Noorse schrijver Johan Harstad de verhalenbundel Ambulance. De Nederlandse vertaling van deze verhalenbundel verscheen in 2014. In 2017 verscheen zijn nieuwe roman Max, Mischa & het Tet-offensief. Naast zijn schrijverschap werkt Harstad als grafisch ontwerper onder het label LACKTR.

Paula Stevens verzorgde deze Harstad-vertalingen, en vertaalde werk van onder anderen Per Petterson, Roy Jacobsen, Lars Saabye Christensen, Åsne Seierstad en Karl Ove Knausgård.

Edith Koenders vertaalde eerder Deense auteurs als Dorthe Nors, Hans Christian Andersen, Søren Kierkegaard, Peter Høeg en Erling Jepsen. Over de vertaling van de nu bekroonde roman schreven ze voor de website van Athenaeum en het Letterenfonds.

Johan Harstad

Max, Mischa & het Tet-offensief

Vertaler: Edith Koenders & Paula Stevens

Uitgeverij Podium

Omslag: b’IJ Barbara

ISBN: 978 90 5759 849 4

Verschenen 08-05-2017

1232 pagina’s

Paperback

€ 29,99

# Meer info op website www.europeseliteratuurprijs.nl

more books

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Book Stories, Archive G-H, Art & Literature News, Awards & Prizes

A young woman in Buenos Aires spies three women in the house across the street from her family’s home. Intrigued, she begins to watch them. She imagines them as accomplices to an unknown crime, as troubled spinsters contemplating suicide, or as players in an affair with dark and mysterious consequences.

Lange’s imaginative excesses and almost hallucinatory images make this uncanny exploration of desire, domestic space, voyeurism and female isolation a twentieth century masterpiece. Too long viewed as Borges’s muse, Lange is today recognized in the Spanish-speaking world as a great writer and is here translated into English for the first time, to be read alongside Virginia Woolf, Clarice Lispector and Marguerite Duras.

Lange’s imaginative excesses and almost hallucinatory images make this uncanny exploration of desire, domestic space, voyeurism and female isolation a twentieth century masterpiece. Too long viewed as Borges’s muse, Lange is today recognized in the Spanish-speaking world as a great writer and is here translated into English for the first time, to be read alongside Virginia Woolf, Clarice Lispector and Marguerite Duras.

Born in 1905 to Norwegian parents in Buenos Aires, Norah Lange was a key figure in the Argentinean avant-garde of the early to mid-twentieth century. Though she began her career writing poetry in the ultraísta mode of urban modernism, her first major success came in 1937 with her memoir Notes from Childhood, followed by the companion memoir Before They Die, and the novels People in the Room and The Two Portraits.

She contributed to the magazines Proa and Martín Fierro, and was a friend to figures such as Jorge Luis Borges, Pablo Neruda, and Federico García Lorca. From her teenage years, when her family home became the site of many literary gatherings, Norah was a mainstay of the Buenos Aires literary scene, and was famous for the flamboyant speeches she gave at parties in celebration of her fellow writers. She traveled widely alone and with her husband, the poet Oliverio Girondo, always returning to Buenos Aires, where she wrote in the house they shared, and where they continued to host legendary literary gatherings. She died in 1972.

Charlotte Whittle has translated works by Silvia Goldman, Jorge Comensal, and Rafael Toriz, among others. Her translations, essays, and reviews have appeared in publications including Mantis, The Literary Review, The Los Angeles Times, Guernica, Electric Literature, BOMB, and the Northwest Review of Books. Originally from England and Utah, she has lived in Mexico, Peru, and Chile, and is now based in New York. She is an editor at Cardboard House Press, a bilingual publisher of Spanish and Latin American poetry.

“Deathly scenes from a wax museum come to life, in a closed, feminine world.” – César Aira

People in the Room

Author: Norah Lange

Translator: Charlotte Whittle

Introduced by César Aira

Language: English

Original language: Spanish

Publisher: And Other Stories

Format: paperback

Publication date: 9 August 2018

ISBN: 9781911508229

Availability: World

Number of pages: 176

Price: €11.09

new books

novel Norah Lange (1905 – 1972)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive K-L, Art & Literature News, Borges J.L., Garcia Lorca, Federico, Libraries in Literature, LITERARY MAGAZINES, Neruda, Pablo

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature