Fleurs du Mal Magazine

De Gouden Griffel is gewonnen door Annet Schaap voor haar prozadebuut Lampje.

De bekendste kinderboekenprijs van Nederland en Vlaanderen is gisteren bekendgemaakt en uitgereikt op het Kinderboekenbal in Amsterdam.

De bekendste kinderboekenprijs van Nederland en Vlaanderen is gisteren bekendgemaakt en uitgereikt op het Kinderboekenbal in Amsterdam.

Annet Schaap is geen onbekende in de Nederlandse kinderboekenwereld: velen kennen haar illustraties uit de Hoe overleef ik-reeks van Francine Oomen, de boeken van Janneke Schotveld en Jacques Vriens.

De Gouden Griffel is de derde prijs die zij wint voor Lampje (Querido): al eerder ontving zij de Nienke van Hichtum-prijs en de Woutertje Pieterse Prijs. De overige genomineerden waren Joukje Akveld, Annet Huizing, Pim Lammers, Joke van Leeuwen, Marit Törnqvist, Susanne Wouda, Bette Westera, Tjibbe Veldkamp en Edward van de Vendel.

Annet wilde altijd al tekenaar worden of schrijver of ontdekkingsreizigster. Ze studeerde aan twee kunstacademies en een schrijversschool. Sinds 1991 illustreerde ze bijna 200 kinderboeken en is in Nederland het meest bekend door haar tekeningen in de succesvolle kinderboeken van Francine Oomen, Janneke Schotveld en Jacques Vriens.

kinderboekenweek van 3 t/m 14 oktober 2018

De Gouden Griffel: Annet Schaap – Lampje

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Awards & Prizes, Grimm, Andersen e.o.: Fables, Fairy Tales & Stories, Illustrators, Illustration, Kinderboekenweek

Proceeding from Hélène Cixous’s charge to “kill the false woman who is preventing the live one from breathing,” The Fix forges that woman’s reckoning with her violent past, with her sexuality, and with a future unmoored from the trappings of domestic life.

Proceeding from Hélène Cixous’s charge to “kill the false woman who is preventing the live one from breathing,” The Fix forges that woman’s reckoning with her violent past, with her sexuality, and with a future unmoored from the trappings of domestic life.

These poems of lyric beauty and unflinching candor negotiate the terrain of contradictory desire—often to darkly comedic effect.

These poems of lyric beauty and unflinching candor negotiate the terrain of contradictory desire—often to darkly comedic effect.

In encounters with strangers in dive bars and on highway shoulders, and through ekphrastic engagement with visionaries like William Blake, José Clemente Orozco, and the Talking Heads, this book seeks the real beneath the dissembling surface.

Here, nothing is fixed, but grace arrives by diving into the complicated past in order to find a way to live, now.

Often I am permitted to return to this kitchen

tipsy, pinned to the fridge, to the precise

instant the kiss smashed in.

When the jaws of night are grinding

and the double bed is half asleep

the snore beside me syncs

to the traffic light, pulsing red, ragged up

in the linen curtain.

(From “Woman Seated with Thighs Apart”)

Lisa Wells is a poet and nonfiction writer who lives in Tucson, Arizona. Her work has appeared in Best New Poets, the Believer, Denver Quarterly, Rumpus, Third Coast, and the Iowa Review.

Lisa Wells (Author)

The Fix

Publisher: University Of Iowa Press

1 edition (April 15, 2018)

Series: Iowa Poetry Prize

Language: English

Product Dimensions:

6 x 0.3 x 8 inches

ISBN-10: 1609385470

ISBN-13: 978-1609385477

Paperback

70 pages

$19.95

new poetry

lisa wells: the fix

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive W-X, Archive W-X

Er bestaat slechts één roman, en daar zijn wij tegelijkertijd zowel de verteller als het onderwerp van: de Geschiedenis.

Al de rest is een schaamteloze kopie. Deze wereldroman vertelt de Geschiedenis eeuw na eeuw en laat ons de avonturen en ontdekkingen van de mensheid herbeleven.

Al de rest is een schaamteloze kopie. Deze wereldroman vertelt de Geschiedenis eeuw na eeuw en laat ons de avonturen en ontdekkingen van de mensheid herbeleven.

De Geschiedenis is zowel oermens, Romein als Napoleons minnares; ze begroet de boekdrukkunst, de Nieuwe Wereld en de moderne wetenschappen en voelt zich thuis in Jeruzalem, Byzantium, Venetië en New York.

Ik leef altijd is een meesterwerk vol ironie en blijmoedigheid, en een intellectuele autobiografie van de auteur.

Jean d’Ormesson (1925 – 2017) was een groot Frans schrijver, filosoof, journalist en lid van de Académie Française. Hij schreef meer dan 40 boeken, fictie en essays. Drie dagen voor zijn overlijden finaliseerde hij zijn laatste boek, Ik leef altijd. Bij publicatie werd het meteen nummer 1 in Frankrijk.

Jean D’Ormesson:

Ik leef altijd

Auteur: Jean D’Ormesson

Vertaling: Johan op de Beeck

Taal: Nederlands

Paperback

Verschijningsdatum

6 september 2018

1e druk

Afmetingen 21 x 13,6 x 2,8 cm

288 pagina’s

ISBN: 9789492626875

Uitg. Horizon

€ 21.99

# new books

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive O-P, Art & Literature News

Jenny Xie’s award-winning debut, Eye Level, takes us far and near, to Phnom Penh, Corfu, Hanoi, New York, and elsewhere, as we travel closer and closer to the acutely felt solitude that centers this searching, moving collection.

“Magnificent . . . [Jenny Xie] braids in the lonesomeness and sorrow of being unmoored and on your own.”—The Paris Review, Staff Picks

“Magnificent . . . [Jenny Xie] braids in the lonesomeness and sorrow of being unmoored and on your own.”—The Paris Review, Staff Picks

Animated by a restless inner questioning, these poems meditate on the forces that moor the self and set it in motion, from immigration to travel to estranging losses and departures. The sensual worlds here―colors, smells, tastes, and changing landscapes―bring to life questions about the self as seer and the self as seen.

As Xie writes, “Me? I’m just here in my traveler’s clothes, trying on each passing town for size.” Her taut, elusive poems exult in a life simultaneously crowded and quiet, caught in between things and places, and never quite entirely at home. Xie is a poet of extraordinary perception―both to the tangible world and to “all that is untouchable as far as the eye can reach.”

Jenny Xie was born in Hefei, China, and raised in New Jersey. She holds degrees from Princeton University and New York University, and has received fellowships and support from Kundiman, the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, the Elizabeth George Foundation, and Poets & Writers. She is the recipient of the 2017 Walt Whitman Award of the Academy of American Poets for Eye Level and the 2016 Drinking Gourd Chapbook Prize for Nowhere to Arrive. Her poems have appeared in the American Poetry Review, Harvard Review, the New Republic, Tin House, and elsewhere. She teaches at New York University.

“For years now, I’ve been using the wrong palette.

Each year with its itchy blue, as the bruise of solitude reaches its expiration date.

Planes and buses, guesthouse to guesthouse.

I’ve gotten to where I am by dint of my poor eyesight,

my overreactive motion sickness.

9 p.m., Hanoi’s Old Quarter: duck porridge and plum wine.

Voices outside the door come to a soft boil.”

(from “Phnom Penh Diptych: Dry Season”)

Title Eye Level

Subtitle Poems

Author Jenny Xie

Publisher Graywolf Press

Format Paperback

ISBN-10 1555978029

ISBN-13 9781555978020

Publication Date 03 April 2018

Main content page count 80

$16.00

new poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive W-X, Archive Y-Z, Art & Literature News

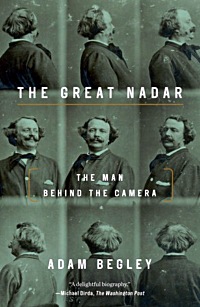

A dazzling, stylish biography of a fabled Parisian photographer, adventurer, and pioneer.

A recent French biography begins, Who doesn’t know Nadar? In France, that’s a rhetorical question. Of all of the legendary figures who thrived in mid-19th-century Paris—a cohort that includes Victor Hugo, Baudelaire, Gustave Courbet, and Alexandre Dumas—Nadar was perhaps the most innovative, the most restless, the most modern.

A recent French biography begins, Who doesn’t know Nadar? In France, that’s a rhetorical question. Of all of the legendary figures who thrived in mid-19th-century Paris—a cohort that includes Victor Hugo, Baudelaire, Gustave Courbet, and Alexandre Dumas—Nadar was perhaps the most innovative, the most restless, the most modern.

The first great portrait photographer, a pioneering balloonist, the first person to take an aerial photograph, and the prime mover behind the first airmail service, Nadar was one of the original celebrity artist-entrepreneurs. A kind of 19th-century Andy Warhol, he knew everyone worth knowing and photographed them all, conferring on posterity psychologically compelling portraits of Manet, Sarah Bernhardt, Delacroix, Daumier and countless others—a priceless panorama of Parisian celebrity.

Born Gaspard-Félix Tournachon, he adopted the pseudonym Nadar as a young bohemian, when he was a budding writer and cartoonist. Later he affixed the name Nadar to the façade of his opulent photographic studio in giant script, the illuminated letters ten feet tall, the whole sign fifty feet long, a garish red beacon on the boulevard. Nadar became known to all of Europe and even across the Atlantic when he launched “The Giant,” a gas balloon the size of a twelve-story building, the largest of its time. With his daring exploits aboard his humongous balloon (including a catastrophic crash that made headlines around the world), he gave his friend Jules Verne the model for one of his most dynamic heroes.

The Great Nadar is a brilliant, lavishly illustrated biography of a larger-than-life figure, a visionary whose outsized talent and canny self-promotion put him way ahead of his time.

Adam Begley is the author of Updike. He was the books editor of The New York Observer for twelve years. He has been a Guggenheim fellow and a fellow at the Leon Levy Center for Biography. His writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Guardian, The Financial Times, The London Review of Books, and The Times Literary Supplement. He lives with his wife in Cambridgeshire.

“Irresistible. . . . A richly entertaining and thoughtful biography. . . . Begley seems wonderfully at home in the Second Empire, and shifts effortlessly between historical backgrounds, technical explanation, and close-up scenes, brilliantly recreating Nadar at work.” —Richard Holmes, The New York Review of Books

The Great Nadar

The Man Behind the Camera

By Adam Begley

Arts & Entertainment

Biographies & Memoirs

History

Paperback

Jul 10, 2018

256 Pages

$16.00

Published by Tim Duggan Books

ISBN 9781101902622

new books

biographie Nadar

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #Biography Archives, - Book News, - Book Stories, - Objets Trouvés (Ready-Mades), Art & Literature News, History of Britain, Photography

Laura

“You are not really dying, are you?” asked Amanda.

“I have the doctor’s permission to live till Tuesday,” said Laura.

“But today is Saturday; this is serious!” gasped Amanda.

“I don’t know about it being serious; it is certainly Saturday,” said Laura.

“Death is always serious,” said Amanda.

“I never said I was going to die. I am presumably going to leave off being Laura, but I shall go on being something. An animal of some kind, I suppose. You see, when one hasn’t been very good in the life one has just lived, one reincarnates in some lower organism. And I haven’t been very good, when one comes to think of it. I’ve been petty and mean and vindictive and all that sort of thing when circumstances have seemed to warrant it.”

“I never said I was going to die. I am presumably going to leave off being Laura, but I shall go on being something. An animal of some kind, I suppose. You see, when one hasn’t been very good in the life one has just lived, one reincarnates in some lower organism. And I haven’t been very good, when one comes to think of it. I’ve been petty and mean and vindictive and all that sort of thing when circumstances have seemed to warrant it.”

“Circumstances never warrant that sort of thing,” said Amanda hastily.

“If you don’t mind my saying so,” observed Laura, “Egbert is a circumstance that would warrant any amount of that sort of thing. You’re married to him — that’s different; you’ve sworn to love, honour, and endure him: I haven’t.”

“I don’t see what’s wrong with Egbert,” protested Amanda.

“Oh, I daresay the wrongness has been on my part,” admitted Laura dispassionately; “he has merely been the extenuating circumstance. He made a thin, peevish kind of fuss, for instance, when I took the collie puppies from the farm out for a run the other day.”

“They chased his young broods of speckled Sussex and drove two sitting hens off their nests, besides running all over the flower beds. You know how devoted he is to his poultry and garden.”

“Anyhow, he needn’t have gone on about it for the entire evening and then have said, ‘Let’s say no more about it’ just when I was beginning to enjoy the discussion. That’s where one of my petty vindictive revenges came in,” added Laura with an unrepentant chuckle; “I turned the entire family of speckled Sussex into his seedling shed the day after the puppy episode.”

“How could you?” exclaimed Amanda.

“It came quite easy,” said Laura; “two of the hens pretended to be laying at the time, but I was firm.”

“And we thought it was an accident!”

“You see,” resumed Laura, “I really have some grounds for supposing that my next incarnation will be in a lower organism. I shall be an animal of some kind. On the other hand, I haven’t been a bad sort in my way, so I think I may count on being a nice animal, something elegant and lively, with a love of fun. An otter, perhaps.”

“I can’t imagine you as an otter,” said Amanda.

“Well, I don’t suppose you can imagine me as an angel, if it comes to that,” said Laura.

Amanda was silent. She couldn’t.

“Personally I think an otter life would be rather enjoyable,” continued Laura; “salmon to eat all the year round, and the satisfaction of being able to fetch the trout in their own homes without having to wait for hours till they condescend to rise to the fly you’ve been dangling before them; and an elegant svelte figure —”

“Think of the otter hounds,” interposed Amanda; “how dreadful to be hunted and harried and finally worried to death!”

“Rather fun with half the neighbourhood looking on, and anyhow not worse than this Saturday-to-Tuesday business of dying by inches; and then I should go on into something else. If I had been a moderately good otter I suppose I should get back into human shape of some sort; probably something rather primitive — a little brown, unclothed Nubian boy, I should think.”

“I wish you would be serious,” sighed Amanda; “you really ought to be if you’re only going to live till Tuesday.”

As a matter of fact Laura died on Monday.

“So dreadfully upsetting,” Amanda complained to her uncle-inlaw, Sir Lulworth Quayne. “I’ve asked quite a lot of people down for golf and fishing, and the rhododendrons are just looking their best.”

“Laura always was inconsiderate,” said Sir Lulworth; “she was born during Goodwood week, with an Ambassador staying in the house who hated babies.”

“She had the maddest kind of ideas,” said Amanda; “do you know if there was any insanity in her family?”

“Insanity? No, I never heard of any. Her father lives in West Kensington, but I believe he’s sane on all other subjects.”

“She had an idea that she was going to be reincarnated as an otter,” said Amanda.

“One meets with those ideas of reincarnation so frequently, even in the West,” said Sir Lulworth, “that one can hardly set them down as being mad. And Laura was such an unaccountable person in this life that I should not like to lay down definite rules as to what she might be doing in an after state.”

“You think she really might have passed into some animal form?” asked Amanda. She was one of those who shape their opinions rather readily from the standpoint of those around them.

Just then Egbert entered the breakfast-room, wearing an air of bereavement that Laura’s demise would have been insufficient, in itself, to account for.

“Four of my speckled Sussex have been killed,” he exclaimed; “the very four that were to go to the show on Friday. One of them was dragged away and eaten right in the middle of that new carnation bed that I’ve been to such trouble and expense over. My best flower bed and my best fowls singled out for destruction; it almost seems as if the brute that did the deed had special knowledge how to be as devastating as possible in a short space of time.”

“Was it a fox, do you think?” asked Amanda.

“Sounds more like a polecat,” said Sir Lulworth.

“No,” said Egbert, “there were marks of webbed feet all over the place, and we followed the tracks down to the stream at the bottom of the garden; evidently an otter.”

Amanda looked quickly and furtively across at Sir Lulworth.

Egbert was too agitated to eat any breakfast, and went out to superintend the strengthening of the poultry yard defences.

“I think she might at least have waited till the funeral was over,” said Amanda in a scandalised voice.

“It’s her own funeral, you know,” said Sir Lulworth; “it’s a nice point in etiquette how far one ought to show respect to one’s own mortal remains.”

Disregard for mortuary convention was carried to further lengths next day; during the absence of the family at the funeral ceremony the remaining survivors of the speckled Sussex were massacred. The marauder’s line of retreat seemed to have embraced most of the flower beds on the lawn, but the strawberry beds in the lower garden had also suffered.

“I shall get the otter hounds to come here at the earliest possible moment,” said Egbert savagely.

“On no account! You can’t dream of such a thing!” exclaimed Amanda. “I mean, it wouldn’t do, so soon after a funeral in the house.”

“It’s a case of necessity,” said Egbert; “once an otter takes to that sort of thing it won’t stop.”

“Perhaps it will go elsewhere now there are no more fowls left,” suggested Amanda.

“One would think you wanted to shield the beast,” said Egbert.

“There’s been so little water in the stream lately,” objected Amanda; “it seems hardly sporting to hunt an animal when it has so little chance of taking refuge anywhere.”

“Good gracious!” fumed Egbert, “I’m not thinking about sport. I want to have the animal killed as soon as possible.”

Even Amanda’s opposition weakened when, during church time on the following Sunday, the otter made its way into the house, raided half a salmon from the larder and worried it into scaly fragments on the Persian rug in Egbert’s studio.

“We shall have it hiding under our beds and biting pieces out of our feet before long,” said Egbert, and from what Amanda knew of this particular otter she felt that the possibility was not a remote one.

On the evening preceding the day fixed for the hunt Amanda spent a solitary hour walking by the banks of the stream, making what she imagined to be hound noises. It was charitably supposed by those who overheard her performance, that she was practising for farmyard imitations at the forth-coming village entertainment.

It was her friend and neighbour, Aurora Burret, who brought her news of the day’s sport.

“Pity you weren’t out; we had quite a good day. We found at once, in the pool just below your garden.”

“Did you — kill?” asked Amanda.

“Rather. A fine she-otter. Your husband got rather badly bitten in trying to ‘tail it.’ Poor beast, I felt quite sorry for it, it had such a human look in its eyes when it was killed. You’ll call me silly, but do you know who the look reminded me of? My dear woman, what is the matter?”

When Amanda had recovered to a certain extent from her attack of nervous prostration Egbert took her to the Nile Valley to recuperate. Change of scene speedily brought about the desired recovery of health and mental balance. The escapades of an adventurous otter in search of a variation of diet were viewed in their proper light. Amanda’s normally placid temperament reasserted itself. Even a hurricane of shouted curses, coming from her husband’s dressing-room, in her husband’s voice, but hardly in his usual vocabulary, failed to disturb her serenity as she made a leisurely toilet one evening in a Cairo hotel.

“What is the matter? What has happened?” she asked in amused curiosity.

“The little beast has thrown all my clean shirts into the bath! Wait till I catch you, you little —”

“What little beast?” asked Amanda, suppressing a desire to laugh; Egbert’s language was so hopelessly inadequate to express his outraged feelings.

“A little beast of a naked brown Nubian boy,” spluttered Egbert.

And now Amanda is seriously ill.

Laura

From ‘Beasts and Super-Beasts’

by Saki (H. H. Munro)

(1870 – 1916)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Saki, Saki, The Art of Reading

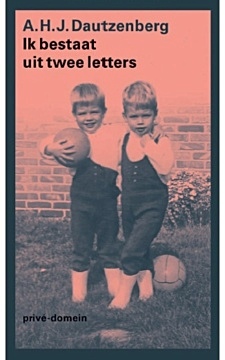

In de vroege ochtend van 13 december 1967 wordt A.H.J. Dautzenberg geboren, drie minuten na zijn broer.

Pas enkele uren voor de bevalling hoort zijn moeder dat ze zwanger is van een tweeling, en in allerijl wordt een tweede naam bedacht.

Een halve eeuw later gaat Dautzenberg op zoek naar zijn gelukkige jeugd.

Hij trekt tijdelijk in bij zijn tweelingbroer die sinds enkele jaren in het ouderlijk huis woont en met wie hij een gecompliceerde relatie onderhoudt.

Uiterst consciëntieus houdt Dautzenberg een dagboek bij. Hij spaart zichzelf (en zijn omgeving) niet en bevraagt het idioom van de autobiografie. (uitgever)

A.H.J. Dautzenberg (Heerlen, 1967) debuteerde in 2010 met de verhalenbundel Vogels met zwarte poten kun je niet vreten. Sindsdien is hij niet meer weg te denken uit de Nederlandse letteren. Dautzenberg schrijft romans, verhalen, essays, gedichten en toneel. Zijn werk werd genomineerd voor verschillende literaire prijzen, waaronder de AKO Literatuurprijs en de J.M.A. Biesheuvelprijs. Hij werd door NRC Handelsblad uitgeroepen tot een van de belangrijke nieuwkomers van de afgelopen jaren. Zijn nieuwste roman Wie zoet is, verscheen 22 september. Op 26 november verschijnt de bloemlezing Vuur! over engagement in de literatuur, een verzameling hemelbestormende schrijvers en bezielde boeken. J.M.A. Biesheuvelprijs, 2015, shortlist (voor En dan komen de foto’s) Mercur 2014, beste nieuwe tijdschrift, shortlist (voor de Quiet 500) Nieuwsmaker van het jaar 2013, Brabants Dagblad (voor de Quiet 500) Beste 25 romans van de afgelopen 5 jaar, 2013, NRC Handelsblad (voor Samaritaan) Beste boek van 2013, Nacht van de NRC (voor Extra tijd) A.L. Snijdersprijs, 2012, longlist (voor Lotusbloemen) AKO Literatuurprijs 2011, longlist (voor Samaritaan) Cutting Edge Beste Roman van 2011, shortlist (voor Samaritaan) Selexyz Debuutprijs 2011, shortlist (voor Vogels met zwarte poten kun je niet vreten)

A.J.H. Dautzenberg:

Ik bestaat uit twee letters

Serie: Privé-domein

Uitgever: De Arbeiderspers

publicatiedatum: 23-05-2018

640 pagina’s

paperback

afm.: 115 x 195 x 44 mm

Illustraties

ISBN 9789029524117

NUR: 321

prijs: € 27,99

# new books

A.J.H. Dautzenberg

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Book Stories, A.H.J. Dautzenberg, Archive C-D, Art & Literature News

Banned Books Week is the annual celebration of the Freedom to Read

The event is sponsored by a coalition of organizations dedicated to free expression, including: American Booksellers Association; American Library Association; American Society of Journalists and Authors; Association of University Presses; The Authors Guild; Comic Book Legal Defense Fund; Dramatists Legal Defense Fund; Freedom to Read Foundation; Index on Censorship; National Coalition Against Censorship; National Council of Teachers of English; PEN America; People for the American Way; and Project Censored. It is endorsed by the Center for the Book in the Library of Congress. Banned Books Week also receives generous support from DKT Liberty Project and Penguin Random House. © 2018 Banned Books Week

Banned Books Week is an annual event celebrating the freedom to read. Banned Books Week was launched in 1982 in response to a sudden surge in the number of challenges to books in schools, bookstores and libraries. Typically held during the last week of September, it highlights the value of free and open access to information. Banned Books Week brings together the entire book community — librarians, booksellers, publishers, journalists, teachers, and readers of all types — in shared support of the freedom to seek and to express ideas, even those some consider unorthodox or unpopular.

Banned Books Week 2018 will be held September 23 – 29. The 2018 theme, “Banning Books Silences Stories,” is a reminder that everyone needs to speak out against the tide of censorship.

By focusing on efforts across the country to remove or restrict access to books, Banned Books Week draws national attention to the harms of censorship. The ALA Office for Intellectual Freedom (OIF) compiles lists of challenged books as reported in the media and submitted by librarians and teachers across the country. The Top Ten Challenged Books of 2017 are:

By focusing on efforts across the country to remove or restrict access to books, Banned Books Week draws national attention to the harms of censorship. The ALA Office for Intellectual Freedom (OIF) compiles lists of challenged books as reported in the media and submitted by librarians and teachers across the country. The Top Ten Challenged Books of 2017 are:

01

Thirteen Reasons Why written by Jay Asher

Originally published in 2007, this New York Times bestseller has resurfaced as a controversial book after Netflix aired a TV series by the same name. This YA novel was challenged and banned in multiple school districts because it discusses suicide.

02

The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian written by Sherman Alexie

Consistently challenged since its publication in 2007 for acknowledging issues such as poverty, alcoholism, and sexuality, this National Book Award winner was challenged in school curriculums because of profanity and situations that were deemed sexually explicit.

03

Drama written and illustrated by Raina Telgemeier

This Stonewall Honor Award-winning, 2012 graphic novel from an acclaimed cartoonist was challenged and banned in school libraries because it includes LGBT characters and was considered “confusing.”

04

The Kite Runner written by Khaled Hosseini

This critically acclaimed, multigenerational novel was challenged and banned because it includes sexual violence and was thought to “lead to terrorism” and “promote Islam.”

05

George written by Alex Gino

Written for elementary-age children, this Lambda Literary Award winner was challenged and banned because it includes a transgender child.

06

Sex is a Funny Word written by Cory Silverberg and illustrated by Fiona Smyth

This 2015 informational children’s book written by a certified sex educator was challenged because it addresses sex education and is believed to lead children to “want to have sex or ask questions about sex.”

07

To Kill a Mockingbird written by Harper Lee

This Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, considered an American classic, was challenged and banned because of violence and its use of the N-word.

08

The Hate U Give written by Angie Thomas

Despite winning multiple awards and being the most searched-for book on Goodreads during its debut year, this YA novel was challenged and banned in school libraries and curriculums because it was considered “pervasively vulgar” and because of drug use, profanity, and offensive language.

09

And Tango Makes Three written by Peter Parnell and Justin Richardson and illustrated by Henry Cole

Returning after a brief hiatus from the Top Ten Most Challenged list, this ALA Notable Children’s Book, published in 2005, was challenged and labeled because it features a same-sex relationship.

10

I Am Jazz written by Jessica Herthel and Jazz Jennings and illustrated by Shelagh McNicholas

This autobiographical picture book co-written by the 13-year-old protagonist was challenged because it addresses gender identity.

https://bannedbooksweek.org/

# Banned Books Week 2018, the annual celebration of the freedom to read – Sept. 23 – 29, 2018

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, - Book News, - Book Stories, Art & Literature News, Banned Books, Literary Events, PRESS & PUBLISHING, REPRESSION OF WRITERS, JOURNALISTS & ARTISTS

Selected Poems 1968-2014 offers forty-five years of work drawn from twelve individual collections by a poet who ‘began as a prodigy and has gone on to become a virtuoso’ (Michael Hofmann).

Hailed by Seamus Heaney as ‘one of the era’s true originals’, Muldoon seems determined to escape definition yet this volume, chosen by the poet himself, serves as an indispensable introduction to his trademark combination of intellectual high jinx and emotional honesty. Among his many honours are the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry and the Shakespeare Prize ‘for contributions from English-speaking Europe to the European inheritance.’

Hailed by Seamus Heaney as ‘one of the era’s true originals’, Muldoon seems determined to escape definition yet this volume, chosen by the poet himself, serves as an indispensable introduction to his trademark combination of intellectual high jinx and emotional honesty. Among his many honours are the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry and the Shakespeare Prize ‘for contributions from English-speaking Europe to the European inheritance.’

Paul Muldoon was born in County Armagh in 1951. He read English at Queen’s University, Belfast, and published his first collection of poems, New Weather, in 1973. He is the author of ten books of poetry, including Moy Sand and Gravel (2002), for which he received the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry, and Horse Latitudes (2006). Since 1987 he has lived in the United States, where he is the Howard G. B. Clark Professor in the Humanities at Princeton University. From 1999 to 2004 he was Professor of Poetry at Oxford University. A Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, Paul Muldoon was given an American Academy of Arts and Letters award in 1996. Other recent awards include the 1994 T. S. Eliot Prize, the 1997 Irish Times Poetry Prize, and the 2003 Griffin Prize.

Paul Muldoon

Selected Poems 1968–2014

Published 01/06/2017

Publisher: Faber & Faber

Length 240 pages

Language: English

ISBN-10: 0571327966

ISBN-13: 978-0571327966

Paperback

£12.99

# new books

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive M-N, Art & Literature News

Mels wordt wakker. Verbaasd ziet hij dat er sneeuw op het matje voor zijn bed ligt. Hij vliegt het bed uit. De vensterbank is nat. De gesmolten sneeuw heeft zijn schoolschrift doorweekt. Het opstel dat hij gisteren heeft geschreven, is onleesbaar op het natte papier. Alle letters zijn uitgelopen. Ze zijn nog het best te lezen in het spiegelschrift aan de andere kant van de blaadjes.

Hij hangt het schrift te drogen op het wasrekje bij de kachel. Even later begint het papier te dampen. Het ruikt naar gesmolten boter.

Als hij zich heeft aangekleed en zijn boterham op heeft, is het schrift droog, maar de tekst blijft onleesbaar. Het is het schrift van een alchemist.

Als hij zich heeft aangekleed en zijn boterham op heeft, is het schrift droog, maar de tekst blijft onleesbaar. Het is het schrift van een alchemist.

Thija en Tijger halen hem op. Hij laat hun het schrift zien.

`Het lijkt op Chinees’, zegt Thija, de letters in spiegelschrift bekijkend. `Het is knap gedaan, maar toch krijg je een slecht cijfer.’

Vandaag zijn ze vrij. Al de hele week. Op school worden de houtkachels vervangen door oliehaarden.

Lange sporen trekkend door de sneeuw, schuiven ze over straat, op weg naar de winkel van juffrouw Fijnhout.

Nu ze niet meer achter haar toonbank kan staan, is de winkel alleen open als er mensen zijn om haar te helpen. Meestal is dat op zaterdagmiddag en door de week van vijf tot zes. Dan staan Mels en Tijger achter de toonbank en zorgt Thija voor juffrouw Fijnhout. Soms, als het druk is, helpen de moeders van Tijger en Mels.

Juffrouw Fijnhout is net uit bed. Haar haren staan uit als pieken, zoals ze op het kussen hebben gelegen. Ze haalt haar hand als een kam door het haar. Ze heeft nog niet ontbeten.

Thija maakt thee.

Juffrouw Fijnhout eet bijna niets meer. Ze drinkt wat thee en pakt er een mariakaakje bij. Ze wordt elke dag geler. Misschien komt het van te veel thee. Soms, als ze even opstaat, schuifelt ze door de keuken en herschikt ze de heiligenprentjes die ze achter de spiegel en de schilderijtjes heeft gestoken, net als de vergeelde rekeningen, briefjes met namen en telefoonnummers en de jarenoude palmtakjes tegen blikseminslag.

`Kun je me helpen een brief te schrijven?’ vraagt ze aan Mels.

`Zeker.’ Hij pakt het schrijfblok en de vulpen uit de bureaulade.

`Wij gaan de winkel poetsen’, zegt Thija. Zij en Tijger verdwijnen met vegers en stofdoeken naar de winkel.

Juffrouw Fijnhout dicteert.

`Lieve nicht Jozefien.’

`Hebt u een nicht?’

Ze hoort zijn vraag niet.

`Ik moet je schrijven over mijn toestand. Ik val maar met de deur in huis: het gaat niet goed met mij. De dokter zegt dat ik kanker heb en dat hij niets voor me kan doen.’

`Kanker?’ zegt Mels. `Ik dacht de gele verf.’

Ze hoort hem niet.

`Misschien kun je me komen opzoeken om mijn voorstel te bespreken. Ik weet dat je het vreemd zult vinden, maar ik denk dat mijn huis en mijn winkel wel wat voor jou zouden zijn. Het winkeltje heeft altijd goed gedraaid. Er komen steeds meer mensen in het dorp wonen, vooral nu de meelfabriek gaat uitbreiden. Ik wil graag dat alles blijft zoals het is, tenslotte was de zaak ook al van je grootouders en heeft jouw moeder, mijn zus Johanna zaliger, net zo veel rechten op het bezit als ik. Jij bezit haar rechten. Als jij de zaak wilt overnemen, is alles van jou, want mijn deel schenk ik je ook. Zie je ervan af, dan schenk ik alles aan de kerk. Ik hoop dat jij jouw deel dan ook aan de kerk laat.’ Ze wacht even. `Heb je dat?’

`Heb je dat?’ vraagt Mels. `Hoe, wat, heb je dat? Het staat er al.’

`Heb je dat allemaal opgeschreven?’

`Ja, alles. Alleen “heb je dat?” moet ik weer doorstrepen.’

`Geeft niet. En zet er maar onder, je liefhebbende tante Jozefien.’

`Jozefien?’

`Mijn nicht heet naar mij.’ Ze zet haar handtekening onder de brief. Mels vouwt hem dicht, stopt hem in een envelop en plakt er een postzegel op.

`Erft Jozefien ook die soldaten op de slaapkamer?’ Hij flapt het er zomaar uit.

Ze kijkt hem aan, met pretlichtjes in haar ogen.

`Je wilt weten hoe ik eraan kom?’

`Eigenlijk wel.’

`Toen ik jong was heb ik als naaister in een atelier voor legerkleding gewerkt. Tot de zaak failliet ging omdat uniformen in Duitsland voordeliger werden gemaakt. Daar waren grotere fabrieken. De jongens die elkaar later hebben afgemaakt, droegen kleren van hetzelfde fabrikaat. Wel droevig. Toen de zaak ophield te bestaan, mocht ik de paspoppen meenemen. Met die kerels in huis voelde ik me niet zo alleen.’

Juffrouw Fijnhout zakt wat verder onderuit op haar stoel en sluit haar ogen.

Mels gaat de anderen helpen in de winkel.

Nadat ze zo geruisloos mogelijk het werk in de winkel hebben gedaan, doen ze de deur achter zich dicht, met het bordje `gesloten’ voor het glas.

Door de dikke laag verse sneeuw lopen ze langs de Wijer naar het molenhuis van grootvader Bernhard, waar ze bij regen of sneeuw vaak zitten te wachten tot het droog is.

Tussen de witte oevers is de Wijer zwart. Aan de kanten heeft ze zich versierd met randjes van bevroren kant. Ze kunnen de duiveltjes die in de beek wonen, van de kou horen kermen, maar ja, wie heeft er medelijden met die gemene opdondertjes? Niemand toch? Behalve Thija. Op een ochtend toen het zo koud was dat de lucht als een mes door je mond sneed, heeft ze een keteltje kokend water in de Wijer gegoten, zodat de duiveltjes zich tenminste eventjes konden warmen.

`Mijn voeten bevriezen’, zegt Mels, die net als Tijger bij elke stap een schep sneeuw in zijn lage schoenen krijgt.

Grootvader is niet thuis, maar het huis is niet op slot. De deur is nooit op slot. Er hangt een briefje, waarop geschreven staat: ik ben naar het kerkhof.

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (073)

wordt vervolgd

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

In Anagnorisis: Poems, the award-winning poet Kyle Dargan ignites a reckoning.

From the depths of his rapidly changing home of Washington, D.C., the poet is both enthralled and provoked, having witnessed-on a digital loop running in the background of Barack Obama‘s unlikely presidency—the rampant state-sanctioned murder of fellow African Americans.

From the depths of his rapidly changing home of Washington, D.C., the poet is both enthralled and provoked, having witnessed-on a digital loop running in the background of Barack Obama‘s unlikely presidency—the rampant state-sanctioned murder of fellow African Americans.

He is pushed toward the same recognition articulated by James Baldwin decades earlier: that an African American may never be considered an equal in citizenship or humanity.

This recognition—the moment at which a tragic hero realizes the true nature of his own character, condition, or relationship with an antagonistic entity—is what Aristotle called anagnorisis.

Not concerned with placatory gratitude nor with coddling the sensibilities of the country’s racial majority, Dargan challenges America: “You, friends- / you peckish for a peek / at my cloistered, incandescent / revelry-were you as earnest / about my frostbite, my burns, / I would have opened / these hands, sated you all.”

At a time when U.S. politics are heavily invested in the purported vulnerability of working-class and rural white Americans, these poems allow readers to examine themselves and the nation through the eyes of those who have been burned for centuries.

KYLE DARGAN is the author of four collections of poetry—Honest Engine (2015), Logorrhea Dementia (2010), Bouquet of Hungers (2007), and The Listening (2004). For his work, he has received the Cave Canem Poetry Prize, the Hurston/Wright Legacy Award, and grants from the D.C. Commission on the Arts and Humanities. His books also have been finalists for the Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award and the Eric Hoffer Book Award Grand Prize. Dargan has partnered with the President’s Committee on the Arts and Humanities to produce poetry programming at the White House and Library of Congress. He has worked with and supports a number of youth writing organizations, such as 826DC, Writopia Lab, and the Young Writers Workshop. He is currently an associate professor of literature and director of creative writing at American University, as well as the founder and editor of POST NO ILLS magazine.

Anagnorisis.

Poems

by Kyle Dargan (Author)

Publication Date

September 2018

Categories

Poetry

African-American Studies

Social Science/Cultural Studies

Trade Paper – $18.00

ISBN 978-0-8101-3784-4

96 pages

Size 6 x 9

Northwestern University Press

# new poetry

Kyle Dargan

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive C-D, Art & Literature News, James Baldwin, The Art of Reading

In volle werking

Die man daar, in volle werking, heeft nooit

iets anders geleerd dan te doen wat hij doet.

Wat hij moet. Dat zag hij goed, de bekijker.

Reeds jong vermoedde hij het: groot genoeg

is nooit je jeugd. De scheppingsdrift? Check.

De hitte van jong bloed? Check. Van wijken

geen weet. Hij wilde weg van louter wit en

zwart. Wenste naar de vervaarlijke geheimen

van zanglijstereiblauw en zonnebloemgeel.

Naar het ruw idioom van vergeten sermoenen.

Hij wist het vroeg reeds, en hij leefde ernaar:

het heeft geen zin om in dode akkers te spitten.

Bert Bevers

Gedicht: In volle werking

Geschreven bij Brief met schets aan Theo van Gogh van Vincent van Gogh, en verschenen in Omtrent Vincent, Uitgeverij Trajart, Chaam, april 2015

Bert Bevers is a poet and writer who lives and works in Antwerp (Be)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Bevers, Bert

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature