Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Die junge Magd

1

Oft am Brunnen, wenn es dämmert,

Sieht man sie verzaubert stehen

Wasser schöpfen, wenn es dämmert.

Eimer auf und niedergehen.

In den Buchen Dohlen flattern

Und sie gleichet einem Schatten.

Ihre gelben Haare flattern

Und im Hofe schrein die Ratten.

Und umschmeichelt von Verfalle

Senkt sie die entzundenen Lider.

Dürres Gras neigt im Verfalle

Sich zu ihren Füßen nieder.

2

Stille schafft sie in der Kammer

Und der Hof liegt längst verödet.

Im Hollunder vor der Kammer

Kläglich eine Amsel flötet.

Silbern schaut ihr Bild im Spiegel

Fremd sie an im Zwielichtscheine

Und verdämmert fahl im Spiegel

Und ihr graut vor seiner Reine.

Traumhaft singt ein Knecht im Dunkel

Und sie starrt von Schmerz geschüttelt.

Röte träufelt durch das Dunkel.

Jäh am Tor der Südwind rüttelt.

3

Nächtens übern kahlen Anger

Gaukelt sie in Fieberträumen.

Mürrisch greint der Wind im Anger

Und der Mond lauscht aus den Bäumen.

Balde rings die Sterne bleichen

Und ermattet von Beschwerde

Wächsern ihre Wangen bleichen.

Fäulnis wittert aus der Erde.

Traurig rauscht das Rohr im Tümpel

Und sie friert in sich gekauert.

Fern ein Hahn kräht. Übern Tümpel

Hart und grau der Morgen schauert.

4

In der Schmiede dröhnt der Hammer

Und sie huscht am Tor vorüber.

Glührot schwingt der Knecht den Hammer

Und sie schaut wie tot hinüber.

Wie im Traum trifft sie ein Lachen;

Und sie taumelt in die Schmiede,

Scheu geduckt vor seinem Lachen,

Wie der Hammer hart und rüde.

Hell versprühn im Raum die Funken

Und mit hilfloser Geberde

Hascht sie nach den wilden Funken

Und sie stürzt betäubt zur Erde.

5

Schmächtig hingestreckt im Bette

Wacht sie auf voll süßem Bangen

Und sie sieht ihr schmutzig Bette

Ganz von goldnem Licht verhangen.

Die Reseden dort am Fenster

Und den bläulich hellen Himmel.

Manchmal trägt der Wind ans Fenster

Einer Glocke zag Gebimmel.

Schatten gleiten übers Kissen,

Langsam schlägt die Mittagsstunde

Und sie atmet schwer im Kissen

Und ihr Mund gleicht einer Wunde.

6

Abends schweben blutige Linnen,

Wolken über stummen Wäldern,

Die gehüllt in schwarze Linnen,

Spatzen lärmen auf den Feldern.

Und sie liegt ganz weiß im Dunkel.

Unterm Dach verhaucht ein Girren.

Wie ein Aas in Busch und Dunkel

Fliegen ihren Mund umschwirren.

Traumhaft klingt im braunen Weiler

Nach ein Klang von Tanz und Geigen,

Schwebt ihr Antlitz durch den Weiler,

Weht ihr Haar in kahlen Zweigen.

Georg Trakl

(1887 – 1914)

Die junge Magd, 1913

•fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Trakl, Georg, Trakl, Georg

Johnny Grey

Johnny Grey

What did he say. I was disagreeing with him. He said he didn’t have it by his side. He said. Hurry.

Eat it.

I am not going to talk about it. I am not going to talk about it.

Another thing.

This is mentioned. He was silly. He said there would have been many more elevators if it hadn’t been for this war.

He was so thirsty.

They asked him.

Please.

If it weren’t for them there would be wind.

I said there wasn’t.

I said it was balmy.

I said that when I was little I asked for a closet.

This was the way it was written.

I was awed.

It is so injudicious to make plans.

We will not decide about three.

Three is the best way to add.

The bank opens tomorrow.

I was mistaken.

I hope I can continue.

To be a tailor.

The other said nothing.

The other one said he was hindering him and he made that mistake and he would not prepare further.

It is not deceiving.

I can say so gladly.

It’s always better.

It’s wonderful how it always comes out.

Conversational.

Plants were said to bring lining together. This is not deceived. This is not deceived. Plants.

Plants were said to bring meadows springing. Shattering stubbornly in their teeth.

Plants aid sad and not furniture.

This is it.

Plants are riotous.

Not even.

If you give money.

Plants are said to be left out if you give money.

Join or gray.

Points are spoken. This in one. Picturesque. It is just the same.

I cannot freeze.

I understand a picture. It is to have stop it who does. It is to have asked about it the sneezing bell. Bell or better.

A simple extenuation.

I mean to be fine with it.

A picture with all of it bitten by that supper. Call it. I shall please. Nowadays.

I find this a very pleasant pencil. Do I. I find this a very pleasant pencil. Do I find this a pleasant pencil.

How to give soldiers fresh water.

How do you.

You use the echoes.

Dear Jenny.

I am your brother. Nestling.

Nestling noses.

My gay.

Baby.

Little.

Lobster.

Chatter.

Sweet.

Joy.

My.

Baby.

Example.

Be good.

Always.

Six.

Seven.

Eight.

Nine.

All.

The.

Time.

Me.

Extra.

My.

Baby.

Scenes where there is no piece of a let it go.

No I am not pleased with their descriptions.

This is not their year.

Two of them.

Johnny Grey and Eddy.

Why not however.

It was not polite.

A long way.

I understand and I say, I understand him to say that, I see him I say I see him or I say, I say that I understand. What is it. He doesn’t realise. I don’t say that he isn’t there I don’t solidly favor him. I said I was prepared. I was prepared to relieve him. I was prepared to relieve him then or then and I was holding, I was holding anything. I am often for them. They gave it. They were pleased. So pleased and side with it. So pleased and have it. So have it and say it. Say it then. If he was promised, it, he had been left by the belief. He had the action. All old. In it. He was wretched. I do not believe or for it. I do not arouse rubbers. When we went away were we then told to be left with them. Do they or do they do it. Do they believe the truth.

I am beginning. Go on Saturday. I believe for Sunday. We deceived everbody.

I forgot to drink water.

No I haven’t seen it.

He said it.

It’s wonderful.

Target.

They don’t believe it either.

Call it.

That.

Fat.

Cheeks.

By.

That.

Time.

Drenced.

By.

That.

Time.

Obligation.

To sign.

That

Today

When

By

That

Field.

He said he was a Spanish family.

It will make.

A

Terrible

Not terrible.

It will not make that one believe me it is not for my pleasure that I promise it.

No

Neither.

That

Or

Another

Neither

One

Lightly

Widened.

Widened by what.

Not this.

Not left.

Buy

Their

It’s not a country.

I told him so.

I wish to begin.

Lining.

Of that thing.

By that time.

It.

Or.

It.

Was.

How.

We don’t know whom to invite for lunch. You told me you’d tell me. I don’t know.

Either.

I do get wonderful action into them don’t I.

Blame.

Worthy.

Out.

Standing.

Eraser.

That was a seat.

Leave it out.

Seat.

Stretch.

Sober.

Left.

Over.

Curling.

Irresistible.

I come to it at last.

I know what I want.

Call.

Tried.

To be.

Just.

Seated.

Beside.

The.

Meaning.

Please come.

I met.

A steady house which was neither blocking nor behaving as if it would for the road.

He looks like it.

A ladder insults.

Me.

I do stem when in.

I don’t look at them any more.

Johnny Grey.

What did I say.

I said I would leave it.

He was so kind.

That was lasting.

I am so certain.

Please.

It’s remarkable that I can make good sentences.

It reminds me of a play that I remember which is better.

It is better.

Everything.

In.

I am coming.

To it.

I know it.

Please.

Pleased.

Pleased with me.

Pleased with me.

Canvas covers.

I wished to go away.

I asked for an astonishing green I asked for more Bertie.

I asked only once.

Pack it.

Package.

A little leaving.

We went to eat.

I have plenty of food.

Always.

Nearly.

Always.

Certainly.

By an example.

I was never afraid.

He doesn’t say anything.

In that way.

Not after.

He was.

Sure.

Of it.

Then.

By then.

We were.

In Munich.

And sat.

Today.

By way

Of

Staring.

And nearly all of it.

In.

That.

Shining.

Firm.

Spread.

Paul.

Slices.

If I copy nature.

If I copy nature.

If I copy nature.

If I copy nature.

For it.

Open.

Seen

Piling.

Left.

In.

Left in.

Not in.

Border

Sew.

Spaces.

I.

Mean.

To.

Laugh.

Do be.

Do be all.

Do be all out.

If you can.

Come.

To stay.

And.

After.

All.

Have.

A.

Night.

Which.

Means.

That.

There

Is.

Not

This

Essential.

By that way.

It was all out in it.

By this time.

Which was reasonable and an explanation.

We never expected he would tell a lie.

Not this.

For.

More.

To be.

Indians are disappointing.

Not to me.

I was never disappointed in an Indian.

I was never disappointed in an Indian in any way.

How old are you.

Careless.

Heavy all the time.

I know she is.

I am.

Politely.

Finished.

Gertrude Stein

(1874-1946)

Johnny Grey

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Archive S-T, Gertrude Stein, Stein, Gertrude

Strange Meeting

It seemed that out of battle I escaped

Down some profound dull tunnel, long since scooped

Through granites which titanic wars had groined.

Yet also there encumbered sleepers groaned,

Too fast in thought or death to be bestirred.

Then, as I probed them, one sprang up, and stared

With piteous recognition in fixed eyes,

Lifting distressful hands, as if to bless.

And by his smile, I knew that sullen hall,—

By his dead smile I knew we stood in Hell.

With a thousand fears that vision’s face was grained;

Yet no blood reached there from the upper ground,

And no guns thumped, or down the flues made moan.

“Strange friend,” I said, “here is no cause to mourn.”

“None,” said that other, “save the undone years,

The hopelessness. Whatever hope is yours,

Was my life also; I went hunting wild

After the wildest beauty in the world,

Which lies not calm in eyes, or braided hair,

But mocks the steady running of the hour,

And if it grieves, grieves richlier than here.

For by my glee might many men have laughed,

And of my weeping something had been left,

Which must die now. I mean the truth untold,

The pity of war, the pity war distilled.

Now men will go content with what we spoiled.

Or, discontent, boil bloody, and be spilled.

They will be swift with swiftness of the tigress.

None will break ranks, though nations trek from progress.

Courage was mine, and I had mystery;

Wisdom was mine, and I had mastery:

To miss the march of this retreating world

Into vain citadels that are not walled.

Then, when much blood had clogged their chariot-wheels,

I would go up and wash them from sweet wells,

Even with truths that lie too deep for taint.

I would have poured my spirit without stint

But not through wounds; not on the cess of war.

Foreheads of men have bled where no wounds were.

“I am the enemy you killed, my friend.

I knew you in this dark: for so you frowned

Yesterday through me as you jabbed and killed.

I parried; but my hands were loath and cold.

Let us sleep now. . . .”

Wilfred Owen

(1893 – 1918)

Strange Meeting (Poem)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Archive O-P, Galerie des Morts, Owen, Wilfred, WAR & PEACE

De slag.

De zon.

Een woud.

Een veld.

Een vliet:

‘t Is geel,

groen, blauw,

maar rood

is ‘t niet.

Gerij.

Gedraaf.

Geschut.

Gedreun:

Gegil!

Gekerm!

Gezucht!

Gekreun!

Geen zon.

Geen woud.

Geen mensch!

Geen hart!

‘t Is bloed!

‘t Is rood!

‘t Is grijs!

‘t Is zwart!

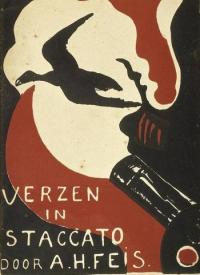

Agnita Feis

(1881 – 1944)

Uit: Oorlog. Verzen in Staccato (1916).

De Slag

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Stories, Agnita Feis, Archive E-F, Archive E-F, De Stijl, Feis, Agnita, Theo van Doesburg

Euthanasia

When Time, or soon or late, shall bring

The dreamless sleep that lulls the dead,

Oblivion! may thy languid wing

Wave gently o’er my dying bed!

No band of friends or heirs be there,

To weep, or wish, the coming blow:

No maiden, with dishevelled hair,

To feel, or feign, decorous woe.

But silent let me sink to earth,

With no officious mourners near:

I would not mar one hour of mirth,

Nor startle friendship with a tear.

Yet Love, if Love in such an hour

Could nobly check its useless sighs,

Might then exert its latest power

In her who lives, and him who dies.

‘Twere sweet, my Psyche! to the last

Thy features still serene to see:

Forgetful of its struggles past,

E’en Pain itself should smile on thee.

But vain the wish?for Beauty still

Will shrink, as shrinks the ebbing breath;

And women’s tears, produced at will,

Deceive in life, unman in death.

Then lonely be my latest hour,

Without regret, without a groan;

For thousands Death hath ceas’d to lower,

And pain been transient or unknown.

`Ay, but to die, and go,’ alas!

Where all have gone, and all must go!

To be the nothing that I was

Ere born to life and living woe!

Count o’er the joys thine hours have seen,

Count o’er thy days from anguish free,

And know, whatever thou hast been,

‘Tis something better not to be.

George Gordon Byron

(1788 – 1824)

Euthanasia

(Poem)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Byron, Lord

The Background

“That woman’s art-jargon tires me,” said Clovis to his journalist friend. “She’s so fond of talking of certain pictures as ‘growing on one,’ as though they were a sort of fungus.”

“That reminds me,” said the journalist, “of the story of Henri Deplis. Have I ever told it you?”

“That reminds me,” said the journalist, “of the story of Henri Deplis. Have I ever told it you?”

Clovis shook his head.

“Henri Deplis was by birth a native of the Grand Duchy of Luxemburg. On maturer reflection he became a commercial traveller. His business activities frequently took him beyond the limits of the Grand Duchy, and he was stopping in a small town of Northern Italy when news reached him from home that a legacy from a distant and deceased relative had fallen to his share.

“It was not a large legacy, even from the modest standpoint of Henri Deplis, but it impelled him towards some seemingly harmless extravagances. In particular it led him to patronize local art as represented by the tattoo-needles of Signor Andreas Pincini. Signor Pincini was, perhaps, the most brilliant master of tattoo craft that Italy had ever known, but his circumstances were decidedly impoverished, and for the sum of six hundred francs he gladly undertook to cover his client’s back, from the collar-bone down to the waistline, with a glowing representation of the Fall of Icarus. The design, when finally developed, was a slight disappointment to Monsieur Deplis, who had suspected Icarus of being a fortress taken by Wallenstein in the Thirty Years’ War, but he was more than satisfied with the execution of the work, which was acclaimed by all who had the privilege of seeing it as Pincini’s masterpiece.

“It was his greatest effort, and his last. Without even waiting to be paid, the illustrious craftsman departed this life, and was buried under an ornate tombstone, whose winged cherubs would have afforded singularly little scope for the exercise of his favourite art. There remained, however, the widow Pincini, to whom the six hundred francs were due. And thereupon arose the great crisis in the life of Henri Deplis, traveller of commerce. The legacy, under the stress of numerous little calls on its substance, had dwindled to very insignificant proportions, and when a pressing wine bill and sundry other current accounts had been paid, there remained little more than 430 francs to offer to the widow. The lady was properly indignant, not wholly, as she volubly explained, on account of the suggested writing-off of 170 francs, but also at the attempt to depreciate the value of her late husband’s acknowledged masterpiece. In a week’s time Deplis was obliged to reduce his offer to 405 francs, which circumstance fanned the widow’s indignation into a fury. She cancelled the sale of the work of art, and a few days later Deplis learned with a sense of consternation that she had presented it to the municipality of Bergamo, which had gratefully accepted it. He left the neighbourhood as unobtrusively as possible, and was genuinely relieved when his business commands took him to Rome, where he hoped his identity and that of the famous picture might be lost sight of.

“But he bore on his back the burden of the dead man’s genius. On presenting himself one day in the steaming corridor of a vapour bath, he was at once hustled back into his clothes by the proprietor, who was a North Italian, and who emphatically refused to allow the celebrated Fall of Icarus to be publicly on view without the permission of the municipality of Bergamo. Public interest and official vigilance increased as the matter became more widely known, and Deplis was unable to take a simple dip in the sea or river on the hottest afternoon unless clothed up to the collarbone in a substantial bathing garment. Later on the authorities of Bergamo, conceived the idea that salt water might be injurious to the masterpiece, and a perpetual injunction was obtained which debarred the muchly harassed commercial traveller from sea bathing under any circumstances. Altogether, he was fervently thankful when his firm of employers found him a new range of activities in the neighbourhood of Bordeaux. His thankfulness, however, ceased abruptly at the Franco–Italian frontier. An imposing array of official force barred his departure, and he was sternly reminded of the stringent law which forbids the exportation of Italian works of art.

“A diplomatic parley ensued between the Luxemburgian and Italian Governments, and at one time the European situation became overcast with the possibilities of trouble. But the Italian Government stood firm; it declined to concern itself in the least with the fortunes or even the existence of Henri Deplis, commercial traveller, but was immovable in its decision that the Fall of Icarus (by the late Pincini, Andreas) at present the property of the municipality of Bergamo, should not leave the country.

“The excitement died down in time, but the unfortunate Deplis, who was of a constitutionally retiring disposition, found himself a few months later, once more the storm-centre of a furious controversy. A certain German art expert, who had obtained from the municipality of Bergamo permission to inspect the famous masterpiece, declared it to be a spurious Pincini, probably the work of some pupil whom he had employed in his declining years. The evidence of Deplis on the subject was obviously worthless, as he had been under the influence of the customary narcotics during the long process of pricking in the design. The editor of an Italian art journal refuted the contentions of the German expert and undertook to prove that his private life did not conform to any modern standard of decency. The whole of Italy and Germany were drawn into the dispute, and the rest of Europe was soon involved in the quarrel. There were stormy scenes in the Spanish Parliament, and the University of Copenhagen bestowed a gold medal on the German expert (afterwards sending a commission to examine his proofs on the spot), while two Polish schoolboys in Paris committed suicide to show what THEY thought of the matter.

“Meanwhile, the unhappy human background fared no better than before, and it was not surprising that he drifted into the ranks of Italian anarchists. Four times at least he was escorted to the frontier as a dangerous and undesirable foreigner, but he was always brought back as the Fall of Icarus (attributed to Pincini, Andreas, early Twentieth Century). And then one day, at an anarchist congress at Genoa, a fellow-worker, in the heat of debate, broke a phial full of corrosive liquid over his back. The red shirt that he was wearing mitigated the effects, but the Icarus was ruined beyond recognition. His assailant was severely reprimanded for assaulting a fellow-anarchist and received seven years’ imprisonment for defacing a national art treasure. As soon as he was able to leave the hospital Henri Deplis was put across the frontier as an undesirable alien.

“In the quieter streets of Paris, especially in the neighbourhood of the Ministry of Fine Arts, you may sometimes meet a depressed, anxious-looking man, who, if you pass him the time of day, will answer you with a slight Luxemburgian accent. He nurses the illusion that he is one of the lost arms of the Venus de Milo, and hopes that the French Government may be persuaded to buy him. On all other subjects I believe he is tolerably sane.”

The Background

From ‘The Chronicles of Clovis’

by Saki (H. H. Munro)

(1870 – 1916)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Saki, Saki, The Art of Reading

Kind met het bleek gelaat

Kind met het bleek gelaat, dat van uw wijde blikken

geen liefde in mat gebaar noch in lede ogen ziet,

maar in uw zedig kleed uw knieën weet te schikken

zó, dat me te elken male een laaie drift doorschiet:

gij zult het nimmer aan mijn vrome woorden weten

hoe mijn begeren om uw kleren dolen dorst;

maar ìk draag in me-zelf de wonde, zelf gereten,

waarvan de koortse rilt en davert door mijn borst.

Want ‘k heb de straffe zélf in ‘t lillend vlees geslagen;

ik heb een spijt’ge spot gehamerd in mijn brein…

– Gij echter, ga voorbij, arm kind, en zónder vragen:

ik haat u om dees geert’, die ‘k minne om deze pijn…

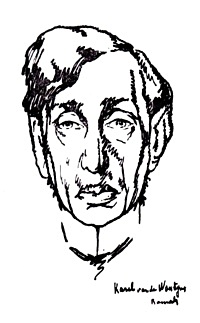

Karel van de Woestijne

(1878 – 1929)

Kind met het bleek gelaat

Portret: Karel van de Woestijne, Ramah – Journal Het Roode Zeil, 15 April 1920

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive W-X, Archive W-X, Woestijne, Karel van de

Triolet En Scie Majeure

Ce jeune lapin gras et digne

A pour petit nom Daniel.

Il est rouge comme une guigne,

Ce jeune lapin gras et digne.

Vous n’avez qu’à lui faire signe:

Il file doux comme du miel.

Ce jeune lapin gras et digne

A pour petit nom Daniel.

Ce jeune lapin gras et digne

A pour petit nom Daniel.

Si vous avez une consigne,

Ce jeune lapin gras et digne

De sa main blanche comme un cygne

Vous fera monter jusqu’au ciel.

Ce jeune lapin gras et digne

A pour petit nom Daniel.

Ce jeune lapin gras et digne

A pour petit nom Daniel.

Le teint fleuri comme la vigne,

Ce jeune lapin gras et digne,

Avec une oeillade maligne,

Flûte en parlant, comme Ariel.

Ce jeune lapin gras et digne

A pour petit nom Daniel.

Ce jeune lapin gras et digne

A pour petit nom Daniel.

Depuis huit jours il a la guigne,

Ce jeune lapin gras et digne:

Je ne puis écrire une ligne

Sans qu’il y soit trempé de fiel.

Ce jeune lapin gras et digne

A pour petit nom Daniel.

Marcel Schwob

(1867-1905)

Triolet En Scie Majeure

Juin 1888

Portrait: Félix Vallotton

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Archive S-T, Félix Vallotton, Marcel Schwob

The Breath

A trembling crest

Of smoke, the winter sky

Congeals to bloom,

To please a poet’s eye:

A slender reed

Arisen from some gold

Recess or womb

Of flame to spaces cold.

Between the twigs,

That for a nest are spun

On flight’s grey loom,

A sapphire thread may run

And so between the grey,

The woven boughs of trees,

A little plume

Of mist the poet sees :

It will suffice —

Too scant a breath to name

For him to whom

It signifies a flame.

Gladys Cromwell

(1885-1919)

The Breath

From: Poems 1919

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Cromwell, Gladys, Gladys Cromwell

Het Portugese woord pessoa komt van het Latijnse persona, dat zowel ‘mens’ als ‘masker’ betekent.

Precies daar moeten we Fernando Pessoa plaatsen, in de wereld van schijn, vermomming, spel, fictie. Hij vergelijkt zichzelf met een podium waarop allerlei acteurs rondlopen.

Precies daar moeten we Fernando Pessoa plaatsen, in de wereld van schijn, vermomming, spel, fictie. Hij vergelijkt zichzelf met een podium waarop allerlei acteurs rondlopen.

Zijn bekendste heteroniemen zijn Bernardo Soares (schrijver van het Boek der rusteloosheid) en de dichters Alberto Caeiro, Ricardo Reis en Álvaro de Campos. Pessoa heeft echter ook onder zijn eigen naam gedichten geschreven. Van dat orthonieme werk zag maar weinig het licht tijdens zijn leven.

Pas lang na zijn dood werden alle losse orthonieme gedichten bijeengebracht in drie delen van elk ruim vijfhonderd bladzijden.

Fernando Pessoa (1888-1935) was een groot Portugees dichter. Bij leven publiceerde deze kantoorklerk uit Lissabon slechts enkele werken. Na zijn dood werd op zijn huurkamer een kist aangetroffen met 27 duizend vol gekrabbelde velletjes. Uit die chaos kon een kolossaal oeuvre worden samengesteld. Niet dat van één dichter, maar van zo’n 25 ‘heteroniemen’ – afzonderlijke ‘schrijverspersoonlijkheden’ met elk een eigen stijl en woordkeus. Pessoa stierf op 47-jarige leeftijd, hij dronk zich dood.

De Arbeiderspers heeft de exclusieve vertaalrechten op zijn oeuvre. August Willemsen (1936-2007) vertaalde het leeuwendeel daarvan en schreef als introductie op de Pessoa-bibliotheek: Het ik als vreemde.

Auteur: Fernando Pessoa

Een spoor van mezelf.

Een keuze uit de orthonieme gedichten

Vertaler: Harrie Lemmens

Nederlands

Uitgeverij: De Arbeiderspers

NUR: 306

Poëzie

Paperback

296 pagina’s

ISBN: 9789029526456

Prijs: € 24,99

Publicatiedatum: 04-06-2019

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Archive O-P, Archive O-P, Pessoa, Fernando, TRANSLATION ARCHIVE

In Punk Rock Is Cool for the End of the World, David Trinidad brings together a comprehensive selection of Ed Smith’s work: his published books; unpublished poems; excerpts from his extensive notebooks; photos and ephemera; and his timely “cry for civilization,” “Return to Lesbos”: put down that gun / stop electing Presidents.

Ed Smith blazed onto the Los Angeles poetry scene in the early 1980s from out of the hardcore punk scene. The charismatic, nerdy young man hit home with his funny/scary off-the-cuff-sounding poems, like “Fishing”: This is a good line. / This is a bad line. This is a fishing line.

Ed Smith blazed onto the Los Angeles poetry scene in the early 1980s from out of the hardcore punk scene. The charismatic, nerdy young man hit home with his funny/scary off-the-cuff-sounding poems, like “Fishing”: This is a good line. / This is a bad line. This is a fishing line.

Ed’s vibrant “gang” of writer and artist friends―among them Amy Gerstler, Dennis Cooper, Bob Flanagan, Mike Kelley, and David Trinidad―congregated at Beyond Baroque in Venice, on LA’s west side. They read and partied and performed together, and shared and published each others’ work.

Ed was more than bright and versatile: he worked as a math tutor, an animator, and a typesetter. In the mid-1990s, he fell in love with Japanese artist Mio Shirai; they married and moved to New York City. Despite productive years and joyful times, Ed was plagued by mood disorders and drug problems, and at the age of forty-eight, he took his own life.

Ed Smith’s poems speak to living in an increasingly dehumanizing consumer society and corrupt political system. This “punk Dorothy Parker” is more relevant than ever for our ADD, technology-distracted times.

Ed Smith (1957–2005) was a poet involved in the punk and alternative arts scenes in Los Angeles in the early 1980s. His books were Fantasyworld (1983) and Tim’s Bunnies (1988). His poems appeared in Rolling Stone, St. Mark’s Poetry Project Newsletter, and other publications. Smith also worked as an animator on Nickelodeon’s Blue’s Clues.

David Trinidad is the author of more than twenty books of poetry, collabora-tions, and edited volumes. These include Swinging on a Star (2017), Notes on a Past Life (2016), Dear Prudence: New and Selected Poems (2011), and Plasticville (2000), finalist for the Lenore Marshall Poetry Prize. Trinidad is editor of A Fast Life: The Collected Poems of Tim Dlugos (2011), which won a Lambda Literary Award. He is a professor of poetry in the English and Creative Writing Department at Columbia College, Chicago.

Punk Rock Is Cool for the End of the World:

Poems and Notebooks of Ed Smith

by Ed Smith (Author), David Trinidad (Editor)

June 11, 2019

Publisher: Turtle Point Press

Language: English

ISBN-10: 1885983670

ISBN-13: 978-1885983671

Paperback

400 pages

$15.78

# new books

Poems and Notebooks

Ed Smith

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: # Music Archive, # Punk poetry, - Book News, - Book Stories, Archive S-T, Archive S-T

De ballon strijkt neer op het dak van de silo. Thija stapt uit.

`Dat jij er ook weer bent’, zegt Mels verbaasd. Hij herkent haar aan het litteken op de knie. Het is net een kleine mond. Hij heeft er een mensenleven lang naar gezocht.

`Dat jij er ook weer bent’, zegt Mels verbaasd. Hij herkent haar aan het litteken op de knie. Het is net een kleine mond. Hij heeft er een mensenleven lang naar gezocht.

Net als Tijger is ze ouder geworden. Grijs. Bijna wit.

`Bij die film,’ zegt ze, `bij dat fragment op de vrachtwagen, Tijger kwam uit de pagode naar buiten kruipen, waar was jij?’

`Ik zat ook op die wagen. Ik had net zo’n punthoed op als jij.’

`Dat ik dat totaal vergeten ben.’

`Ik ving je op toen je over een touw viel. Je zou van de wagen zijn gevallen.’

Ze buigt zich naar hem toe en geeft hem een kus. Het is alsof ze nooit uit het dorp vertrokken is. Opeens herkent hij alles aan haar, haar een beetje schuinstaande ogen. Haar oorschelpen waar je doorheen kunt kijken. Om iets van haar gedaan te krijgen, moest je het haar verbieden. Als je wilde dat ze je kuste, moest je zeggen dat je dat juist niet wilde. Dan kuste ze je extra lang, zo lang tot haar oorschelpen van porselein werden. Als je tegen haar wilde zeggen dat je haar mooi vond, kon je beter zeggen dat je bloemen mooi vond, of hemelbeestjes. Soms wist ze dan dat je haar bedoelde.

`Je hebt me lang alleen gelaten’, zegt Mels.

`Natuurlijk wist ik dat je verliefd op me was’, zegt ze. `Maar ouders houden daar geen rekening mee als ze gaan verhuizen.’

`Je had me toch kunnen schrijven! Ik weet nog steeds niet of je voor Tijger had gekozen, als hij niet was verongelukt.’

`Dat weet ik ook niet’, zegt ze. `Toen Tijger nog in leven was, deed ik altijd raadselspelletjes om erachter te komen van wie ik het meest hield, van jou of van hem. Ken je het aftelversje “Koning Karel had geen brood en daarom sloeg hij een van zijn soldaten dood” nog? Het blad dat overbleef aan de tak was koning Karel, maar altijd vergat ik of jij of Tijger koning Karel was. Toen Tijger dood was, vond ik het niet eerlijk dat ik niet meer voor hem kon kiezen. Dat was ook niet eerlijk tegenover jou, want misschien had ik later gedacht dat ik toch voor Tijger had moeten kiezen. Daarom vond ik het ook goed dat mijn ouders gingen verhuizen, ook al was ik toen heel verdrietig om jou. Omdat ik nooit een keus heb kunnen maken, had het nooit meer álles kunnen zijn.’

`Dat is waar’, zegt Mels. `Ik heb gezien hoe je gehuild hebt toen Tijger dood op straat lag. Zo kun je maar één keer in je leven huilen.’

`Die dag herinner ik me nog goed.’

`We hadden verhalen verteld’, zegt Mels. `Jij kon het best vertellen. Jij vertelde altijd prachtige verhalen over China.’

`Ik ben nooit in China geweest’, zegt ze. `Dat maakte ik jullie wijs. Om interessant te zijn. Ik kon er wel alles over verzinnen.’

`Je moeder wel?’

`Zij wel, ze is er geboren, maar ze is er al jong vertrokken. We hebben altijd heimwee gehad naar een land dat we niet kenden.’

`Met jou waren we overal naartoe gegaan.’

`Ik heb de dood van Tijger nog vaak opnieuw beleefd’, zegt Mels. `Maar altijd alleen tot aan het moment van de begrafenis. Ik weet dat de stoet naar de kerk trok. Daarna weet ik niets meer.’

`Je viel flauw’, zegt Thija. `Ze hebben je naar huis gebracht en de dokter heeft je een slaapmiddel gegeven. Ik heb een hele dag aan je bed gezeten terwijl je sliep.’

`Dat ik dat niet meer weet?’

`Je hebt toen zeker twee dagen geslapen.’

`En toen?’

`We zijn samen naar het kerkhof gegaan, om naar de bloemen te kijken op het graf.’

`En toen?’

`Kort daarna zijn we verhuisd.’

`Naar Rotterdam, zei je. Naar China had je op een briefje geschreven. Naar een van de twee China’s. Naar welk China?’

`Naar het China in mijn hoofd. Ik wist zelf ook niet wat er gebeurde. Ik wist niets van China.’

`Daarna was ik helemaal alleen’, zegt Mels. `Ik had niemand meer.’

`Net als ik. Precies, net als ik.’

`Hoe is het je later vergaan?’ vraagt hij.

`Dat doet er niet meer toe. Ik weet ook niet veel over jou, al weet ik dat je altijd hier bent gebleven. En dat je een dochter hebt. En kleinkinderen.’

`Ja’, geeft Mels toe. Hij denkt aan Afke. Hij hoort zijn dochter in de straat. Ze praat tegen iemand.

`Hoor je die stem? Dat is mijn dochter. Ze lijkt op mij, maar ze vindt me lastig. Door die rolstoel. Alleen mijn kleindochter houdt van me. Afke heeft me nooit anders gekend dan in een rolstoel. Ik vertel haar vaak over ons. Hoe wij vroeger waren, jij, Tijger en ik.’

`Hoe kwam je in die rolstoel terecht?’

`Aangereden door een auto. Ik kwam uit het café. Ik had wat gedronken. Dat neemt Lizet me nu nog kwalijk. Meer is er niet over te vertellen. Vanaf toen was ik alleen. Ik wist niet dat een mens zo eenzaam kon zijn.’

Ongerust, omdat hij het ademen van de baby niet meer hoort, buigt hij zich over de rand. Hij hoort alleen nog het soezen van de kat, die in de wagen opgeschoven is tot op de buik van het kind.

Moet hij schreeuwen? Nee. Naar hem luisteren ze niet. Van zo hoog horen ze hem trouwens niet.

Hij wacht, terwijl het zweet hem uitbreekt. Hij weet dat het een ramp kan worden.

Hij ziet dat zijn dochter naar de slagerij loopt. Nu hoort hij ook de stem van Kemp. Het gesprek is vrolijk. Hij hoort Marjan ongegeneerd lachen, zoals ze altijd lacht als ze met haar schoonvader praat. Ze is zich niet bewust van de rampen die haar vandaag kunnen treffen. Hij hoort ook Kemp lachen. Zoals hij altijd tegen vrouwen lacht.

In de eerste tijd dat hij in zijn rolstoel zat, stak Kemp zijn hand op als hij hem naar de brug zag rijden, maar later deed hij dat niet meer. Vanaf dat moment keek hij ook nooit meer naar de winkel van de slager, maar reed hij recht door naar de brug. Meestal probeerde hij het er zo lang mogelijk vol te houden, uitkijkend over de Wijer. In het begin om met de passerende mensen te praten. Toen dat was afgelopen, vooral om zo lang mogelijk thuis weg te zijn.

Alleen zijn was het enige dat hij in de laatste jaren nog verdroeg. Alleen zijn, zonder eeuwig dankbaar te moeten zijn voor hulp. Zonder het alledaags gekijf aan te hoeven horen. Niet meer te hoeven horen dat hij lastig is. Dat hij te zwaar wordt om op te tillen. En dat het jammer is dat ze hem in het revalidatiecentrum niet terug willen.

Hij hoort een gil. Het is de stem van zijn vrouw. Tussen zijn voeten door ziet hij haar bij de wieg staan. Ze houdt de baby in haar armen en rent ermee de straat op, naar haar dochter, die staat te lachen met Kemp.

Lizets stem slaat barsten in alles.

`De kat lag op zijn buik! Hij had dood kunnen zijn!’

Zijn dochter neemt de baby in de armen.

`Waarom let je niet beter op het kind!’ schreeuwt Lizet.

`Hij lag te slapen’, zegt Marjan.

`Je vader heeft het al zo vaak gezegd! Hij zegt altijd dat je op de kat moet letten.’

`Waar is vader?’

Mels schrikt van de haat in de stem van zijn dochter. Zo’n diepe haat.

`Hij behekst die kat’, zegt Marjan.

`Hoe kan dat nou’, hoort Mels zijn vrouw zeggen. `Die man kan niks meer. Hij is aan het dementeren.’

Zijn hart krimpt. Het is de eerste keer dat hij het haar hardop hoort zeggen. Hij heeft het haar vaak zien denken. Met de hoop in de ogen dat het ook waar zou zijn, zodat ze hem dan naar een verpleeghuis kon afschuiven.

`Die kat moet kapot’, roept Kemp. `Ze is gevaarlijk voor het kind.’ Met zijn hakbijl loopt hij naar het beest dat zich, nietsvermoedend en lekker lui, uitstrekt op de stoep. Met één klap hakt hij haar kop in tweeën, pakt het stuiptrekkende dier bij de staart en gooit het kreng in een vuilniston.

Opeens ruikt Mels versgebakken brood. Hij ziet de schoorsteen van de bakker roken. Het water staat hem in de mond.

Het is zes uur. Etenstijd. Tijd om naar huis te gaan. Elke dag zit zijn vrouw op hem te wachten. Ongeduldig. Kwaad. De mond al bijna open voor de uitval.

`Ik moet naar huis’, zegt hij. `Lizet wacht op me.’

`Ik begrijp het’, zegt Thija.

`Het leven dwingt’, zegt Tijger.

De gedachte aan haar kwade gezicht dwingt Mels tot haast. Hij haalt de handrem los. De wind krijgt vat op hem. De stoel rolt naar voren en valt over de rand. Hij duikelt over de kop en valt recht naar beneden. Een schok. Even blijft de stoel hangen op een richel. Genoeg tijd voor Mels om te veranderen in een vogel. Op vleugels zo groot als van een adelaar wiekt hij over het dorp. Van zo hoog ziet hij hoe de rolstoel verder naar beneden tuimelt, op een zuigslang van de silo stuitert en op straat valt.

De mensen schieten toe. Terwijl hij hoog over het dorp vliegt, weet hij dat ze nu allemaal aan hem denken. Hij vliegt over de rode, blauwe en grijze daken die glinsteren in het lage zonlicht. Hij vliegt over akkers en weilanden, tot aan de boorden van de Wijer, en ploft in de boot.

`Wat hebben wij lang op jou moeten wachten’, zegt Tijger, die voor op de plecht zit.

`Ben ik nog op tijd?’

`Natuurlijk’, zegt Thija. `Jij hoort erbij. Zonder jou zouden wij niet naar China gaan.’

Mels grijpt de riemen en roeit.

`De Wijer stroomt flink’, zegt Tijger vergenoegd.

`Het heeft hard geregend’, zegt Thija. `Kijk maar eens hoe groen de weilanden zijn, en dat midden in de zomer.’

Ze heeft de reistas op haar knieën. Hij ziet het roze litteken in de vorm van een mondje op haar knie. Het nodigt hem uit om het te kussen, maar hij houdt zich in. Straks, in China.

Ze glijden naar de brug toe. Hij ziet hoe zijn moeder op de brug staat, samen met de twee grootvaders en de moeder van Thija en van Tijger.

`We gaan naar China!’ roept hij naar zijn moeder als ze bijna bij de brug zijn. `Ik breng een rode lampion voor je mee! En een zijden jurk! En een gouden haarspeld met een drakenkop!’

Zijn moeder roept wat terug, maar hij hoort haar niet, net zomin als hij de andere roepende mensen hoort die als mist verdampen in het licht van de zon.

De boot glijdt onder de brug door. Als ze in het halfdonker zijn, die toverachtige plek waar lichtgevende polsdikke slakken kleven op muren die druipen van het vocht, verandert de boot in een klein vliegtuig. Brullend schiet het toestel onder de brug uit en klimt de lucht in.

`Waar vliegen we heen?’ vraagt Mels.

`Ik weet een mooie plaats bij de Wijer’, roept Tijger boven het lawaai van de brullende motor uit. `Het weitje achter het huis van grootvader Bernhard. Daar komt nooit iemand.’

`Als er niemand komt, kan er zich ook niemand aan storen dat ik van jullie allebei evenveel hou’, zegt Thija, terwijl ze zich aan Mels vasthoudt omdat het vliegtuig als een jong hert door de lucht springt.

`Ik heb daar spullen begraven’, roept Tijger.

`Ik dacht dat we naar China zouden gaan’, zegt Mels.

`Dat gaan we ook.’

`China ligt toch niet aan de Wijer?’

`Toch’, zegt Thija. `Tijger heeft gelijk. We hebben er lang over gedaan om erachter te komen dat China zo dichtbij is.’

Het vliegtuig landt op de weg voor de watermolen, waar vroeger de paardenkarren stonden, die het graan brachten. Ze staan er weer. Dikke, knokige trekpaarden met hondstrouwe ogen, voor platte karren.

`Dat die paarden er weer zijn’, zegt Mels.

`Hoezo?’ vraagt Tijger. `Ze zijn nooit weggeweest. Ik heb ze nooit gemist.’

`Later zijn ze vervangen door vrachtwagens en tractors. Dat heb jij niet meer meegemaakt.’

`Wel! Ik ben vaak met de vrachtwagen van grootvader Bernhard mee geweest. Net als jullie.’

Ze lopen naar het weitje.

Tijger weet het nog precies, de plek waar hij zijn schat begraven heeft. Tien meter vanaf de achterdeur van het molenhuis, vijf meter vanaf het bruggetje. Nadat hij op het oog heeft gemeten, begint hij te graven. Even later schuurt de schop over het metaal van een kist. Een blauwe, aan de hoeken verroeste gereedschapskist.

Tijger graaft hem uit. Het deksel is vastgeroest. Tijger klopt erop met de schop. Het slot springt open, met een geluid of er binnen in de kist een veer knapt.

Hij opent de kist. Pakjes in cellofaanpapier. Hij pakt een van de pakjes uit. Het papier knispert. Er zitten ballonnen in. Ze blazen ze op. Ze zijn vreemd blauw en rood. Het lijkt meer op waterverfblauw en op tomatenrood. Kleuren van toen. Zelfs kleuren blijken anders te zijn geworden.

Tijger pakt een ander pakje uit. Het is de harmonica die hij van Mels heeft gekregen.

`Zie je, hij is nog helemaal goed. Alleen een beetje roestig.’

Hij blaast erop. Het ding doet het nog. Een paar schrille tonen, een beetje vals.

`Geeft niet’, zegt Thija. `Een mondharmonica mag best een beetje vals zijn. Als je van muziek wilt huilen, moet het juist een beetje anders klinken. Zuiver zingen komt alleen de vogels toe.’

`Vogels zijn er hier genoeg’, roept Tijger. `Wielewalen, koolmeesjes, hoor maar, alles.’

Tijger begint weer te spelen, met langgerekte, droevig klinkende halen. Ze kennen het lied. Het gaat over een moeder die in de kerk komt bidden voor haar zoon die ze heeft verloren. `Achter in het stille klooster, weent een moeder om haar kind.’ Terwijl Mels zingt, hoort hij de stem van zijn moeder, die het lied honderden keren heeft gezongen. Hij vraagt zich af of hij het kind was waarover ze zo vaak gezongen heeft. Een kind dat er was en van wie ze hield maar dat er niet had mogen zijn. Heeft hij geleefd in de plaats van een ander? Hij voelt zich schuldig aan het verdriet van zijn moeder.

`Kom, we gaan langs het water zitten’, zegt Thija. `Het is nu geen tijd voor melancholie.’

Ze lopen naar de beek en gaan op de oever liggen, in het zachte, groene gras.

Tijger speelt een ander deuntje. Ze zingen het mee, zacht. `Er waren eens twee koningskinderen. En ze hadden elkander zo lief.’

Terwijl ze zingen en naar de muziek luisteren, speuren ze naar forellen, die vadsig, vol ingehouden snelheid, in de stroom liggen. Om ze te vangen is het zaak om niet alleen net zo vadsig, maar ook net zo snel als zij te zijn.

Langzaam strekt Mels zijn arm over het water, bijna zonder te bewegen. Onder zijn hand schurkt de forel zich aan het in de stroom langgerekte wier. Het is zaak om de hand, voordat de schaduw over de forel valt, als een speer door het water te laten schieten.

Plots, zonder dat het water spat, schiet Mels’ hand uit. Beet. In één haal grijpt hij de forel en gooit hem op de kant.

`Wat nu?’ vraagt Thija.

`Vraag het maar aan de vis’, zegt Mels. `Misschien kan hij praten. Net als de vissen uit jouw sprookjes.’

`Kom vis, zeg hoe je heet.’ Thija kietelt hem onder zijn openstaande bek.

De vis zegt niets. Zijn grote, wijdopen ogen staren naar de hemel.

`Hij verstaat ons niet’, zegt Mels. `We eten hem op.’

`Daar is hij veel te mooi voor.’

`Je bent week.’

Het spijt Mels direct dat hij dat heeft gezegd. Hij ziet hoe Thija wegkijkt als hij de vis bij de staart pakt en hem met zijn kop op een steen doodslaat.

`Durf je hem wel te eten?’

`Dood is hij nog net zo mooi’, zegt Thija. `Denk je er wel eens aan dat wij ook doodgaan? Dat wij hier net zo liggen als die vis?’

`Welnee’, zegt Tijger. `Wij toch niet. Wij leven eeuwig.’

`Kom, we gaan thuis de vis braden’, zegt Mels.

Ze springen op de fiets.

`Zullen we doen wie het eerst bij de kerk is?’ roept Tijger.

`Jij maakt altijd van alles een wedstrijd’, zegt Mels.

`Dat zeg je omdat je niet durft. Om jouw horloge?’

`Goed. Jij je zin.’

`Je krijgt tien meter voorsprong.’

Ze schieten weg. Mels trapt als een bezetene, hij wil zijn horloge houden, maar even later zoeft Tijger al langs hem heen.

`Die gek’, zegt Thija. `Hij fietst zich nog eens dood.’

EINDE

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (108 – slot)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature