Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry (1900-1944) aspirait à un monde où l’action et le rêve fussent intimement liés, convaincu qu’en cette coïncidence résidait la vérité de l’expérience vécue.

Sa voie fut celle du consentement au risque : le désert et les périls aériens, qui ouvrent alors au trésor caché de l’existence, à la révélation de ce qui nous tient fraternellement et spirituellement aux nôtres et au monde.

Sa voie fut celle du consentement au risque : le désert et les périls aériens, qui ouvrent alors au trésor caché de l’existence, à la révélation de ce qui nous tient fraternellement et spirituellement aux nôtres et au monde.

Saint-Exupéry s’est appuyé sur son exceptionnelle expérience d’aviateur pour affirmer sa confiance dans la grandeur humaine, accessible à chacun par l’engagement librement consenti. Toute son œuvre littéraire – ici resituée dans le mouvement biographique qui l’a vue naître – est une tentative admirable pour restituer poétiquement la substance même de l’existence, sa vérité intime et sincère – celle du cœur.

Réunissant les œuvres littéraires d’Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, de ses premiers contes et poèmes de jeunesse, inspirés par son apprentissage de pilote, à Citadelle, incluant ses quatre grands romans et Le Petit Prince, cette édition est enrichie de très nombreux documents inédits ou méconnus, se fonde sur les plus récentes découvertes et offre pour la première fois dans la collection Quarto un volume illustré en couleurs.

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

Du vent, du sable et des étoiles. Œuvres

Littérature française

XXe siècle

Édition d’Alban Cerisier

Éditions Gallimard

Collection Quarto

Parution : 15-11-2018

1680 pages

602 ill.

sous couverture illustrée, 140 x 205 mm

ISBN : 9782072742422

Gencode : 9782072742422

Code distributeur : G00982

32€

# New books

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

Œuvres

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Bookstores, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, Archive E-F, Art & Literature News

John Keats Poem

Who killed John Keats?

‘I,’ says the Quarterly,

So savage and Tartarly;

”Twas one of my feats.’

Who shot the arrow?

‘The poet-priest Milman

(So ready to kill man),

Or Southey or Barrow.

George Gordon Byron

(1788 – 1824)

John Keats Poem

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Byron, Lord, Keats, John

“See glossy photos of bathroom doorknobs and mail slots, learn more about early community newsletters, whistle with the neighborhood bagpiper. In two words: be amazed.” –Sebastian Hofer, The Detroit News

Lafayette Park, a middle-class residential area in downtown Detroit, is home to the largest collection of buildings designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe in the world.

Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, it remained one of Detroit’s most racially integrated and economically stable neighborhoods, although it was surrounded by evidence of a city in financial distress.

Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, it remained one of Detroit’s most racially integrated and economically stable neighborhoods, although it was surrounded by evidence of a city in financial distress.

Through interviews with and essays by residents, reproductions of archival material: new photographs by Karin Jobst, Vasco Roma and Corine Vermeulen, and previously unpublished photographs by documentary filmmaker Janine Debanné.

Thanks for the View, Mr. Mies examines the way that Lafayette Park residents confront and interact with this unique modernist environment.

This book is a reaction against the way that iconic modernist architecture is often represented. Whereas other writers may focus on the design intentions of the architect, authors Aubert, Cavar and Chandani seek to show the organic and idiosyncratic ways in which the people who live in Lafayette Park actually use the architecture and how this experience, in turn, affects their everyday lives.

Thanks for the View, Mr. Mies was originally published in 2012, two years before the city of Detroit entered into the largest municipal bankruptcy in the country.

The 2019 edition of Thanks for the View, Mr. Mies includes a revised introduction and two new texts by Lafayette Park residents, and authors, Marsha Music and Matthew Piper.

Music and Piper reflect on the changes the neighborhood underwent between 2012 and 2018, when the city went through and emerged from bankruptcy and entered into a new phase, as a desirable place for real estate investment.

Thanks for the View, Mr. Mies

Lafayette Park, Detroit

Edited by Danielle Aubert, Lana Cavar, Natasha Chandani. Text by Danielle Aubert, Lana Cavar, Natasha Chandani, Marsha Music, Matthew Piper.

URBAN STUDIES AND THEORY

Publisher Metropolis Books

Forthcoming | 4/23/2019

Paperback, 6.5 x 9.5 in.

304 pgs

Illustrated throughout

ISBN 9781942884408

$29.95

# New books

Thanks for the View, Mr. Mies

Lafayette Park, Detroit

URBAN STUDIES AND THEORY

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Bookstores, Architecture, Archive Q-R, Art & Literature News, Bauhaus, Bauhaus, De Stijl, Modernisme

`Ik heb het schrift van Jacob bij me’, zegt Mels. `Ik wil eruit voorlezen.’

`Dat doen we op het dak van de silo’, zegt Thija. `Kom op.’

Aan de achterkant van de fabriek lopen ze door een openstaande deur naar binnen. De fabriek zelf is klein en valt in het niet bij de silo waarin het graan wordt opgeslagen.

Aan de achterkant van de fabriek lopen ze door een openstaande deur naar binnen. De fabriek zelf is klein en valt in het niet bij de silo waarin het graan wordt opgeslagen.

Over een ijzeren trap gaan ze omhoog. Hun schoenen klepperen op de stalen roosters die de traptreden vormen.

Het gebouw is gevuld met vier kleinere, ronde silo’s, voor elke graansoort een. Het ruikt er naar de enorme berg graan die opgeslagen is. Stoffig graan, dat op hun keel werkt.

`Het is helemaal niet wit hierbinnen’, zegt Thija. `Ik dacht altijd dat het vol meel zat.’

`Na de oogst komt hier het graan binnen’, zegt Tijger. `Genoeg om de fabriek het hele jaar te laten draaien.’

Door kleine raampjes kijken ze uit over het dorp en de Wijer, die nu lang en dun is en op een slang lijkt.

Door een luik stappen ze op het dak. De wind krijgt vat op Thija’s rok en blaast hem bollend op.

`Hou je vast!’ roept Tijger. `Je vliegt weg!’

`Dat wil ik juist’, lacht Thija, maar toch houdt ze zich aan hem vast.

Ze kijken uit over het dorp. Ze horen de mensen beneden, die bonkende, kloppende en tikkende geluiden maken.

Ze gaan op hun rug op het dak liggen. Van zo hoog lijkt de hemel veel weidser.

Mels droomt, met open ogen. Met z’n drieën zitten ze in de boot op de Wijer. Ze zijn van plan naar China te gaan. Thija heeft haar reistas op schoot, met daarin een cadeautje voor de keizer. Alleen zij weet wat het is. Ze heeft er Tijger en Mels niets over gezegd. Die vragen er ook niet naar. Dat heeft geen zin, want als je haar wat vraagt, zegt ze het zeker niet.

De boot gaat maar langzaam vooruit. Het water staat laag. Mels moet flink roeien.

Eindelijk komen ze in het dorp aan. Tijd om afscheid te nemen. Er staat maar één persoon op de brug. Tijgers moeder, in een zwarte flodderjurk. Door de wind wappert haar rode haar rond haar hoofd. Mels mist zijn moeder. En waar zijn de grootvaders? Hij is teleurgesteld. Ze horen er te staan, om hen uit te wuiven. Interesseert het hen niet meer dat ze weggaan?

Mels vindt het vooral vreemd dat zijn eigen moeder hem niet uitzwaait en dat ze doodgewoon de ramen aan het lappen is. Hij hoort haar zingen. `Je bent al groter dan mijn buik voordat je werd geboren. Ik zal nog van je houden, ook al word je zo groot als de kerktoren.’ Maar als ze zo veel van hem houdt, waarom zwaait ze hem dan niet uit?

Terwijl ze onder de brug door varen, verandert de boot in een groene helikopter.

Tijger zit aan de stuurknuppel. Hij roept iets. Wat? Het lawaai van de helikopter is zo oorverdovend dat Mels hem niet verstaat. Hij ziet dat Thija tegen Tijger praat, want haar mond beweegt. Hij hoort alleen zijn moeder die zingt: `Je bent al groter dan mijn buik voordat je werd geboren.’

Dan gebeurt er iets vreemds. De helikopter verandert in een zwarte flodderjurk. Opeens zitten Mels en Thija in de donkere buik van Tijgers moeder. Tijger zit in haar glazen hoofd. Hij kijkt door haar ogen en veegt de wapperende rode haren weg die hem het uitzicht ontnemen.

`Ze vliegt ons naar de duivel!’ roept Mels.

Mels hoort dat Tijger iets terugroept, in paniek, maar zijn stem gaat verloren in het geraas. Met een enorme klap vliegen ze tegen de silo. De jurk van zwart glas laat een sneeuwbui van zwarte splinters over het dorp vallen.

`Je ligt te slapen’, zegt Thija.

`Het komt door de wind’, zegt Mels. `Ik droomde dat we naar China vertrokken, in een groene helikopter die veranderde in Tijgers moeder.’

`En toen?’

`We vlogen tegen de silo.’

`Zie je wel’, zegt Thija. `Die droom voorspelt dat onze reis nooit zal lukken. Tijger komt nooit van zijn moeder los.’

`En jij?’

`Ik?’ Thija lijkt verbaasd. `Ik ben geen moederskindje. Jij?’

`Nee’, zegt Mels, maar hij weet dat het anders is. Hij houdt ervan dat zijn moeder zingt.

Om zich niet verder te hoeven verdedigen, pakt Mels het schrift van Jacob.

`Lees jij voor?’ Hij geeft het schrift aan Thija.

Ze slaat het open, bladert het door.

`Hij schreef ook gedichten.’

Ze schraapt haar keel, zoals ook meester Hajenius altijd deed als hij begon met voorlezen.

`Ze vroegen aan mij waarom ik huilde.

Het was de wind die mij dat vroeg,

het waren de vogels die mij vroegen,

jongen, waarom ben jij zo alleen?

Ze zeggen tegen mij,

ze zeggen het niet,

maar ze zouden het willen zeggen.

Waarom is je huis zo leeg?

Waarom is je hart alleen?

Waarom ben je verlaten?

Ze zeggen het niet.

Het was de wind die mij dat vroeg,

het waren de vogels die mij dat vroegen.

Als ik gestorven ben,

zal de wind het aan jullie vragen.

Als ik gestorven ben,

zullen de vogels aan jullie vragen,

waarom ik zo alleen was.’

Ze zijn er stil van, omdat Jacob zo precies had geweten hoe het hem zou vergaan.

Ze staan op en dalen de trap af.

Beneden, in bijna lege ruimtes, draaien de machines die het lawaai veroorzaken. Het is er zo lawaaiig dat ze naar elkaar schreeuwen en elkaar toch nauwelijks kunnen verstaan. Het is niet duidelijk wat de machines doen. Er is niemand. Het is net of er niemand werkt. Het is een spookfabriek.

`Het lijkt of we in een boek van Jules Verne terecht zijn gekomen’, roept Tijger.

`We zijn op de maan’, roept Mels terug in Tijgers oor. `De machines maken lucht en water, zodat wij hier ook kunnen leven.’

`Bij die herrie kan niemand leven’, roept Thija, de handen voor de oren.

`Ik wel’, roept Tijger. `Ik hou van hard. Lawaai is mooi. Ik zou hier graag willen wonen.’

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (091)

wordt vervolgd

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

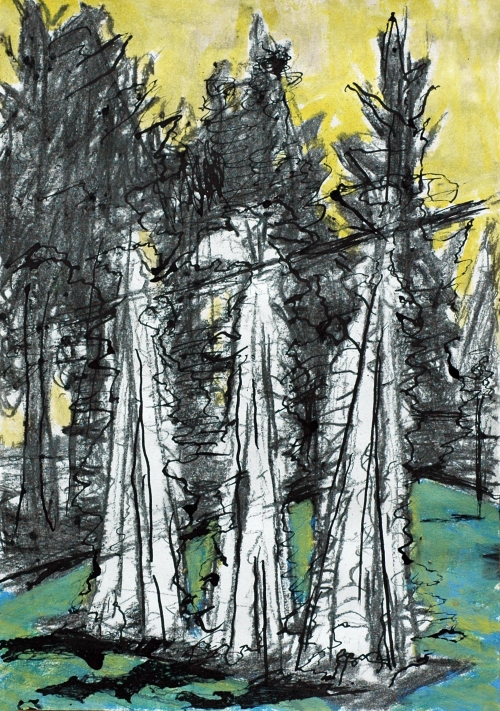

Hans Ebeling Koning

Vegetation II

Hans Ebeling Koning (1931) received his education at AKI in Enschede where he later became a teacher in drawing and painting. His work is represented in many public and private collections including Museum Henriette Polak in Zutphen, Rijksmuseum Twente and the Museum of Modern Art in Arnhem.

# More work of on Hans Ebeling Koning website

Hans Ebeling Koning ©

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Art & Literature News, Dutch Landscapes, FDM Art Gallery, Hans Ebeling Koning, Natural history

Jean Cocteau (1889 – 1963) is een kunstenaar die tot de verbeelding spreekt. Hij uitte zich in bijna alle artistieke media: poëzie, literatuur, beeldende kunst, vormgeving, theater en zijn favoriete medium: film.

Meer nog dan om zijn werk was Cocteau bekend om zijn opmerkelijke leven. Hij omgaf zich met beroemdheden als Sergei Diaghilev, Edith Piaf, Pablo Picasso en Coco Chanel, en raakte geregeld in opspraak vanwege zijn homoseksualiteit en drugsgebruik.

Meer nog dan om zijn werk was Cocteau bekend om zijn opmerkelijke leven. Hij omgaf zich met beroemdheden als Sergei Diaghilev, Edith Piaf, Pablo Picasso en Coco Chanel, en raakte geregeld in opspraak vanwege zijn homoseksualiteit en drugsgebruik.

Het oeuvre van Cocteau was een voorbode van de multidisciplinaire praktijken van ontwerpers en kunstenaars van nu. Jean Cocteau | Metamorphosis werpt licht op zijn voortdurende zelftransformatie en zijn zoektocht naar een eigen identiteit. In de hedendaagse maatschappij, waarin het emancipatiedebat weer hoogtij viert en waarin de persoonlijke beeld-en identiteitsvorming in hoge mate beïnvloedbaar is, zijn Cocteau’s leven en werk opnieuw actueel.

Zoals jonge mensen zich tegenwoordig digitaal een identiteit aanmeten, had Cocteau de gave om zichzelf via diverse media steeds met andere ogen te bezien en te laten zien. Jean Cocteau | Metamorphosis toont veel van die gezichten, in woord en in beeld.

Jean Cocteau

Metamorphosis

door Ioannis Kontaxopoulos

november 2018

ISBN 978-94-6208-470-4

design: Berry van Gerwen

Nederlands, Frans

paperback

17 x 24 cm

320 pag.

geillustreerd (150 kleur)

in samenwerking met: Design Museum den Bosch

NAi Boekverkopers / Booksellers

€ 34,95

De tentoonstelling over Jean Cocteau in het Design Museum Den Bosch, loopt nog tot en met 10 maart 2019.

# New books

Jean Cocteau

Metamorphosis

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive C-D, Archive C-D, Art & Literature News, DANCE & PERFORMANCE, Design, Exhibition Archive, FDM Art Gallery, Jean Cocteau, LGBT+ (lhbt+), Maison de la Poésie, Museum of Literary Treasures, SURREALISM, Surrealism, Surrealisme, THEATRE

This book provides a fresh assessment of the works of poet and painter Mina Loy (1882 – 1966).

Laura Scuriatti shows how Loy’s “eccentric” writing and art celebrate ideas and aesthetics central to the modernist movement while simultaneously critiquing them, resulting in a continually self-reflexive and detached stance that Scuriatti terms “critical modernism.”

Laura Scuriatti shows how Loy’s “eccentric” writing and art celebrate ideas and aesthetics central to the modernist movement while simultaneously critiquing them, resulting in a continually self-reflexive and detached stance that Scuriatti terms “critical modernism.”

Drawing on neglected archival material, Scuriatti illuminates the often-overlooked influence of Loy’s time spent amid Italian avant-garde culture. In particular, she considers Loy’s assessment of the nature of genius and sexual identity as defined by philosopher Otto Weininger and in Lacerba, a magazine founded by Futurist leader Giovanni Papini. She also investigates Loy’s reflections on the artistic masterpiece in relation to the world of commodities; explores the dialogic nature of the self in Loy’s autobiographical projects; and shows how Loy used her “eccentric” stance as a political position, especially in her later career in the United States.

Offering new insights into Loy’s feminism and tracing the writer’s lifelong exploration of themes such as authorship, art, identity, genius, and cosmopolitanism, this volume prompts readers to rethink the place, value, and function of key modernist concepts through the critical spaces created by Loy’s texts.

Laura Scuriatti, professor of English and comparative literature at Bard College Berlin, is coeditor of The Exhibit in the Text: Museological Practices of Literature.

Mina Loy’s Critical Modernism

Laura Scuriatti

Hardcover

320 pages

Literature – European

ISBN 13: 9780813056302

$85.00

Available for pre-order.

This book will be available in July 2019

(Pub Date: 5/7/2019)

# New books

Mina Loy

Critical Modernism

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive K-L, Archive K-L, Archive S-T, Art & Literature News, Futurism, Loy, Mina

Aan de basis van Richard Longs werken ligt steeds een eenvoudige geometrische vorm: de cirkel, de lijn, de spiraal of het kruis – minimale vormen die in het landschap opvallen omdat ze door mensenhanden zijn gemaakt.

Long heeft ze tijdens wandelingen overal ter wereld achtergelaten: cirkels van steen en hout in Frankrijk en Alaska of in de mist in Schotland; een kronkelende lijn in een stenige vlakte in de Sahara en een lijn van water uitgegoten op een brugje in de Italiaanse Alpen.

Long heeft ze tijdens wandelingen overal ter wereld achtergelaten: cirkels van steen en hout in Frankrijk en Alaska of in de mist in Schotland; een kronkelende lijn in een stenige vlakte in de Sahara en een lijn van water uitgegoten op een brugje in de Italiaanse Alpen.

Van al het werk maakt hij foto’s, die hij in galeries en musea laat zien. Ook op andere manieren haalt hij zijn werken het museum binnen, door stenen of takken die hij in de natuur heeft verzameld te rangschikken tot strakke banen of cirkels, maar ook door tekeningen en schilderingen te maken met rivierklei.

Richard Long

16 feb – 16 juni 2019

De Pont is vernoemd naar de jurist en zakenman Jan de Pont (1915-1987) uit wiens nalatenschap in 1988 een stichting ‘ter stimulering van de hedendaagse kunst’ kon worden opgericht.

Het museum is sinds 1992 gevestigd in een voormalige wolspinnerij die is verbouwd tot een ruimte waar hedendaagse kunst optimaal tot haar recht kan komen. De monumentale oude fabriek met de grote, lichte zaal en de intieme ‘wolhokken’ vormt een prachtige omgeving voor de vele kunstwerken.

Museum De Pont

Wilhelminapark 1

5041 EA Tilburg

Nederland

# Website Museum De Pont Tilburg

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Art & Literature News, Exhibition Archive, FDM Art Gallery, Land Art, Richard Long

«Une semaine qu’elle tient. Une semaine qu’elle n’a pas cédé. Adèle a été sage. En quatre jours, elle a couru trente-deux kilomètres.

Elle est allée de Pigalle aux Champs-Élysées, du musée d’Orsay à Bercy. Elle a couru le matin sur les quais déserts.

Elle est allée de Pigalle aux Champs-Élysées, du musée d’Orsay à Bercy. Elle a couru le matin sur les quais déserts.

La nuit, sur le boulevard Rochechouart et la place de Clichy. Elle n’a pas bu d’alcool et elle s’est couchée tôt.

Mais cette nuit, elle en a rêvé et n’a pas pu se rendormir.

Un rêve moite, interminable, qui s’est introduit en elle comme un souffle d’air chaud.

Adèle ne peut plus penser qu’à ça. Elle se lève, boit un café très fort dans la maison endormie. Debout dans la cuisine, elle se balance d’un pied sur l’autre.

Elle fume une cigarette. Sous la douche, elle a envie de se griffer, de se déchirer le corps en deux. Elle cogne son front contre le mur. Elle veut qu’on la saisisse, qu’on lui brise le crâne contre la vitre.

Dès qu’elle ferme les yeux, elle entend les bruits, les soupirs, les hurlements, les coups. Un homme nu qui halète, une femme qui jouit. Elle voudrait n’être qu’un objet au milieu d’une horde, être dévorée, sucée, avalée tout entière.

Qu’on lui pince les seins, qu’on lui morde le ventre.

Elle veut être une poupée dans le jardin de l’ogre.»

Leïla Slimani

Dans le jardin de l’ogre

Nouvelle édition à tirage limité en 2018

Prix littéraire de la Mamounia 2015

Collection Folio, Gallimard

Parution : 01-11-2018

240 pages

sous couverture illustrée

108 x 178 mm

Roman

Littérature française

ISBN : 9782072821967

Gencode : 9782072821967

Code distributeur : G02382

Prix : 8,05 €

# New books

Leïla Slimani

Dans le jardin de l’ogre

Nouvelle édition

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive S-T, Art & Literature News, Leïla Slimani

The Unrest-Cure

On the rack in the railway carriage immediately opposite Clovis was a solidly wrought travelling-bag, with a carefully written label, on which was inscribed, “J. P. Huddle, The Warren, Tilfield, near Slowborough.” Immediately below the rack sat the human embodiment of the label, a solid, sedate individual, sedately dressed, sedately conversational.

Even without his conversation (which was addressed to a friend seated by his side, and touched chiefly on such topics as the backwardness of Roman hyacinths and the prevalence of measles at the Rectory), one could have gauged fairly accurately the temperament and mental outlook of the travelling bag’s owner. But he seemed unwilling to leave anything to the imagination of a casual observer, and his talk grew presently personal and introspective.

Even without his conversation (which was addressed to a friend seated by his side, and touched chiefly on such topics as the backwardness of Roman hyacinths and the prevalence of measles at the Rectory), one could have gauged fairly accurately the temperament and mental outlook of the travelling bag’s owner. But he seemed unwilling to leave anything to the imagination of a casual observer, and his talk grew presently personal and introspective.

“I don’t know how it is,” he told his friend, “I’m not much over forty, but I seem to have settled down into a deep groove of elderly middle-age. My sister shows the same tendency. We like everything to be exactly in its accustomed place; we like things to happen exactly at their appointed times; we like everything to be usual, orderly, punctual, methodical, to a hair’s breadth, to a minute. It distresses and upsets us if it is not so. For instance, to take a very trifling matter, a thrush has built its nest year after year in the catkin-tree on the lawn; this year, for no obvious reason, it is building in the ivy on the garden wall. We have said very little about it, but I think we both feel that the change is unnecessary, and just a little irritating.”

“Perhaps,” said the friend, “it is a different thrush.”

“We have suspected that,” said J. P. Huddle, “and I think it gives us even more cause for annoyance. We don’t feel that we want a change of thrush at our time of life; and yet, as I have said, we have scarcely reached an age when these things should make themselves seriously felt.”

“What you want,” said the friend, “is an Unrest-cure.”

“An Unrest-cure? I’ve never heard of such a thing.”

“You’ve heard of Rest-cures for people who’ve broken down under stress of too much worry and strenuous living; well, you’re suffering from overmuch repose and placidity, and you need the opposite kind of treatment.”

“But where would one go for such a thing?”

“Well, you might stand as an Orange candidate for Kilkenny, or do a course of district visiting in one of the Apache quarters of Paris, or give lectures in Berlin to prove that most of Wagner’s music was written by Gambetta; and there’s always the interior of Morocco to travel in. But, to be really effective, the Unrest-cure ought to be tried in the home. How you would do it I haven’t the faintest idea.”

It was at this point in the conversation that Clovis became galvanized into alert attention. After all, his two days’ visit to an elderly relative at Slowborough did not promise much excitement. Before the train had stopped he had decorated his sinister shirt-cuff with the inscription, “J. P. Huddle, The Warren, Tilfield, near Slowborough.”

Two mornings later Mr. Huddle broke in on his sister’s privacy as she sat reading Country Life in the morning room. It was her day and hour and place for reading Country Life, and the intrusion was absolutely irregular; but he bore in his hand a telegram, and in that household telegrams were recognized as happening by the hand of God. This particular telegram partook of the nature of a thunderbolt. “Bishop examining confirmation class in neighbourhood unable stay rectory on account measles invokes your hospitality sending secretary arrange.”

“I scarcely know the Bishop; I’ve only spoken to him once,” exclaimed J. P. Huddle, with the exculpating air of one who realizes too late the indiscretion of speaking to strange Bishops. Miss Huddle was the first to rally; she disliked thunderbolts as fervently as her brother did, but the womanly instinct in her told her that thunderbolts must be fed.

“We can curry the cold duck,” she said. It was not the appointed day for curry, but the little orange envelope involved a certain departure from rule and custom. Her brother said nothing, but his eyes thanked her for being brave.

“A young gentleman to see you,” announced the parlour-maid.

“The secretary!” murmured the Huddles in unison; they instantly stiffened into a demeanour which proclaimed that, though they held all strangers to be guilty, they were willing to hear anything they might have to say in their defence. The young gentleman, who came into the room with a certain elegant haughtiness, was not at all Huddle’s idea of a bishop’s secretary; he had not supposed that the episcopal establishment could have afforded such an expensively upholstered article when there were so many other claims on its resources. The face was fleetingly familiar; if he had bestowed more attention on the fellow-traveller sitting opposite him in the railway carriage two days before he might have recognized Clovis in his present visitor.

“You are the Bishop’s secretary?” asked Huddle, becoming consciously deferential.

“His confidential secretary,” answered Clovis. “You may call me Stanislaus; my other name doesn’t matter. The Bishop and Colonel Alberti may be here to lunch. I shall be here in any case.”

It sounded rather like the programme of a Royal visit.

“The Bishop is examining a confirmation class in the neighbourhood, isn’t he?” asked Miss Huddle.

“Ostensibly,” was the dark reply, followed by a request for a large-scale map of the locality.

Clovis was still immersed in a seemingly profound study of the map when another telegram arrived. It was addressed to “Prince Stanislaus, care of Huddle, The Warren, etc.” Clovis glanced at the contents and announced: “The Bishop and Alberti won’t be here till late in the afternoon.” Then he returned to his scrutiny of the map.

The luncheon was not a very festive function. The princely secretary ate and drank with fair appetite, but severely discouraged conversation. At the finish of the meal he broke suddenly into a radiant smile, thanked his hostess for a charming repast, and kissed her hand with deferential rapture.

Miss Huddle was unable to decide in her mind whether the action savoured of Louis Quatorzian courtliness or the reprehensible Roman attitude towards the Sabine women. It was not her day for having a headache, but she felt that the circumstances excused her, and retired to her room to have as much headache as was possible before the Bishop’s arrival. Clovis, having asked the way to the nearest telegraph office, disappeared presently down the carriage drive. Mr. Huddle met him in the hall some two hours later, and asked when the Bishop would arrive.

“He is in the library with Alberti,” was the reply.

“But why wasn’t I told? I never knew he had come!” exclaimed Huddle.

“No one knows he is here,” said Clovis; “the quieter we can keep matters the better. And on no account disturb him in the library. Those are his orders.”

“But what is all this mystery about? And who is Alberti? And isn’t the Bishop going to have tea?”

“The Bishop is out for blood, not tea.”

“Blood!” gasped Huddle, who did not find that the thunderbolt improved on acquaintance.

“To-night is going to be a great night in the history of Christendom,” said Clovis. “We are going to massacre every Jew in the neighbourhood.”

“To massacre the Jews!” said Huddle indignantly. “Do you mean to tell me there’s a general rising against them?”

“No, it’s the Bishop’s own idea. He’s in there arranging all the details now.”

“But — the Bishop is such a tolerant, humane man.”

“That is precisely what will heighten the effect of his action. The sensation will be enormous.”

That at least Huddle could believe.

“He will be hanged!” he exclaimed with conviction.

“A motor is waiting to carry him to the coast, where a steam yacht is in readiness.”

“But there aren’t thirty Jews in the whole neighbourhood,” protested Huddle, whose brain, under the repeated shocks of the day, was operating with the uncertainty of a telegraph wire during earthquake disturbances.

“We have twenty-six on our list,” said Clovis, referring to a bundle of notes. “We shall be able to deal with them all the more thoroughly.”

“Do you mean to tell me that you are meditating violence against a man like Sir Leon Birberry,” stammered Huddle; “he’s one of the most respected men in the country.”

“He’s down on our list,” said Clovis carelessly; “after all, we’ve got men we can trust to do our job, so we shan’t have to rely on local assistance. And we’ve got some Boy-scouts helping us as auxiliaries.”

“Boy-scouts!”

“Yes; when they understood there was real killing to be done they were even keener than the men.”

“This thing will be a blot on the Twentieth Century!”

“And your house will be the blotting-pad. Have you realized that half the papers of Europe and the United States will publish pictures of it? By the way, I’ve sent some photographs of you and your sister, that I found in the library, to the MATIN and DIE WOCHE; I hope you don’t mind. Also a sketch of the staircase; most of the killing will probably be done on the staircase.”

The emotions that were surging in J. P. Huddle’s brain were almost too intense to be disclosed in speech, but he managed to gasp out: “There aren’t any Jews in this house.”

“Not at present,” said Clovis.

“I shall go to the police,” shouted Huddle with sudden energy.

“In the shrubbery,” said Clovis, “are posted ten men who have orders to fire on anyone who leaves the house without my signal of permission. Another armed picquet is in ambush near the front gate. The Boy-scouts watch the back premises.”

At this moment the cheerful hoot of a motor-horn was heard from the drive. Huddle rushed to the hall door with the feeling of a man half awakened from a nightmare, and beheld Sir Leon Birberry, who had driven himself over in his car. “I got your telegram,” he said, “what’s up?”

Telegram? It seemed to be a day of telegrams.

“Come here at once. Urgent. James Huddle,” was the purport of the message displayed before Huddle’s bewildered eyes.

“I see it all!” he exclaimed suddenly in a voice shaken with agitation, and with a look of agony in the direction of the shrubbery he hauled the astonished Birberry into the house. Tea had just been laid in the hall, but the now thoroughly panic-stricken Huddle dragged his protesting guest upstairs, and in a few minutes’ time the entire household had been summoned to that region of momentary safety. Clovis alone graced the tea-table with his presence; the fanatics in the library were evidently too immersed in their monstrous machinations to dally with the solace of teacup and hot toast. Once the youth rose, in answer to the summons of the front-door bell, and admitted Mr. Paul Isaacs, shoemaker and parish councillor, who had also received a pressing invitation to The Warren. With an atrocious assumption of courtesy, which a Borgia could hardly have outdone, the secretary escorted this new captive of his net to the head of the stairway, where his involuntary host awaited him.

And then ensued a long ghastly vigil of watching and waiting. Once or twice Clovis left the house to stroll across to the shrubbery, returning always to the library, for the purpose evidently of making a brief report. Once he took in the letters from the evening postman, and brought them to the top of the stairs with punctilious politeness. After his next absence he came half-way up the stairs to make an announcement.

“The Boy-scouts mistook my signal, and have killed the postman. I’ve had very little practice in this sort of thing, you see. Another time I shall do better.”

The housemaid, who was engaged to be married to the evening postman, gave way to clamorous grief.

“Remember that your mistress has a headache,” said J. P. Huddle. (Miss Huddle’s headache was worse.)

Clovis hastened downstairs, and after a short visit to the library returned with another message:

“The Bishop is sorry to hear that Miss Huddle has a headache. He is issuing orders that as far as possible no firearms shall be used near the house; any killing that is necessary on the premises will be done with cold steel. The Bishop does not see why a man should not be a gentleman as well as a Christian.”

That was the last they saw of Clovis; it was nearly seven o’clock, and his elderly relative liked him to dress for dinner. But, though he had left them for ever, the lurking suggestion of his presence haunted the lower regions of the house during the long hours of the wakeful night, and every creak of the stairway, every rustle of wind through the shrubbery, was fraught with horrible meaning. At about seven next morning the gardener’s boy and the early postman finally convinced the watchers that the Twentieth Century was still unblotted.

“I don’t suppose,” mused Clovis, as an early train bore him townwards, “that they will be in the least grateful for the Unrest-cure.”

The Unrest-Cure

From ‘The Chronicles of Clovis’

by Saki (H. H. Munro)

(1870 – 1916)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Saki, Saki, The Art of Reading

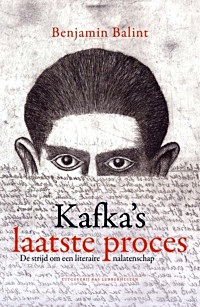

Het nagelaten werk van Franz Kafka is dankzij zijn vriend Max Brod bewaard gebleven, maar na het overlijden van Brod in 1968 begint een hevige en absurde strijd om het eigendomsrecht.

De originele, handgeschreven versies van meesterwerken als Het proces en De gedaanteverwisseling komen achtereenvolgens in handen van Brods secretaresse Esther Hoffe en haar dochter Eva.

De originele, handgeschreven versies van meesterwerken als Het proces en De gedaanteverwisseling komen achtereenvolgens in handen van Brods secretaresse Esther Hoffe en haar dochter Eva.

Er ontvouwt zich echter een juridisch getouwtrek als zowel Israël als Duitsland het werk claimen.

Duitsland, waar drie zussen van Kafka stierven tijdens de Tweede Wereldoorlog, wil de schrijver recht doen, en Israël meent rechten te hebben als Joodse staat en Kafka’s gedroomde land.

Kafka’s laatste proces leest als een waargebeurde thriller, maar maakt pijnlijk duidelijk hoe de Joodse schrijver Franz Kafka inzet wordt van zionistische claims. In de verbeten strijd die de twee landen uitvechten, lijken ze vooral de geschiedenis te willen herschrijven.

Benjamin Balint woont in Jeruzalem, waar hij verbonden is aan het Van Leer Institute. Hij schrijft o.a. voor Haaretz en de Wall Street Journal. Over de Joods-Amerikaanse schrijvers die publiceerden in het tijdschrift Commentary, schreef hij Running Commentary (2010).

Benjamin Balint (Auteur)

Kafka’s laatste proces.

De strijd om een literaire nalatenschap

Vertaling Frank Lekens

Oorspronkelijke titel:

Kafka’s Last Trial.

The Case of a Literary Legacy

Omslagtekening Jirí Slíva

Omslag Bart van den Tooren

Uitg. Bas Lubberhuizen

304 pagina’s

15 x 23 cm

Geïllustreerde paperback

ISBN 9789059375284

Verschenen: januari 2019

€ 24,99

# New books

Benjamin Balint

Kafka’s Last Trial.

The Case of a Literary Legacy

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive A-B, Archive K-L, Archive K-L, Art & Literature News, Franz Kafka, Kafka, Franz, Kafka, Franz

Een lange vrachtwagen van Bouwbedrijf Leon van Wijk en Zonen stopt bij de silo. Een kraan takelt bouwmateriaal uit de bak: planken, stalen stutbalken, steigermateriaal, een werkkeet en een bouwlift. Een ploegje arbeiders begint met het bouwen van de steigers.

Met gemengde gevoelens ziet Mels het aan. Als een moederkloek heeft het enorme gebouw altijd het dorp beheerst. Tot zomaar, van de ene op de andere dag, aan de werknemers werd verteld dat het bedrijf verkocht was en de productie werd gestaakt. Terwijl het toch volop winst maakte en er een paar maanden eerder nog een uitbreiding was aangekondigd. De fabriek was ten onder gegaan aan haar eigen succes en was opgekocht door de concurrentie om te worden uitgeschakeld.

Met gemengde gevoelens ziet Mels het aan. Als een moederkloek heeft het enorme gebouw altijd het dorp beheerst. Tot zomaar, van de ene op de andere dag, aan de werknemers werd verteld dat het bedrijf verkocht was en de productie werd gestaakt. Terwijl het toch volop winst maakte en er een paar maanden eerder nog een uitbreiding was aangekondigd. De fabriek was ten onder gegaan aan haar eigen succes en was opgekocht door de concurrentie om te worden uitgeschakeld.

De vrachtwagen van het bouwbedrijf vertrekt. De chauffeur steekt een hand op. Mels groet terug.

Even later loopt de opzichter naar het café. Hij staat stil op de brug en kijkt naar het water.

`Viswater?’

`Vroeger zat er forel in’, zegt Mels. `Als jongen heb ik er genoeg gevangen. En aal.’

`Nu niets meer?’

`Ze vangen soms baars. Een enkele snoek.’

`Kom ik zondag eens kijken. Ik gooi graag een hengeltje uit.’

Hij loopt door naar het café en komt even later naar buiten met een pakje shag.

`Wat komt er in de silo?’ vraagt Mels.

`Appartementen.’ De man rolt een sigaret. `Ze worden verkocht als exclusief.’

`Dat ding is toch niet apart?’

`Ze zeggen dat het een monument is. Een dorpsbepalend beeld. Zoiets. Hij moet blijven staan vanwege het historisch belang.’ Hij likt zijn shagje dicht. `Ze hadden er beter een bom op kunnen gooien. Hadden ze plaats gehad voor echte huizen. Mij maakt het niks uit. Wij hebben er een mooie klus aan.’

`Ik wil je wat vragen. Ik zoek iemand om een paar pannen op mijn dak te vervangen.’

`Heb je nog pannen?’

`Genoeg.’

`Ik stuur wel een mannetje. Stop hem maar wat toe. Altijd goed.’

`Dank je.’

De man loopt verder.

`Toch missen we de fabriek’, zegt Mels nog. `We waren eraan gewend. Het lawaai in de maalderij was onbeschrijflijk mooi.’

`Mooi?’

`De een vindt dit mooi, de ander dat.’

`Gelukkig dat we allemaal van andere meisjes houden,’ lacht de man, `anders bleven er veel over.’

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (090)

wordt vervolgd

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature