Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Hannah Sullivan’s debut collection is a revelation – three long poems of fresh ambition, intensity, and substance.

Though each poem stands apart, their inventive and looping encounters make for a compelling unity.

Though each poem stands apart, their inventive and looping encounters make for a compelling unity.

“You, Very Young in New York” captures a great American city, in all its alluring detail. It is a wry and tender study of romantic possibility, disappointment, and the obduracy of innocence.

“Repeat until Time” begins with a move to California and unfolds into an essay on repetition and returning home, at once personal and philosophical.

“The Sandpit after Rain” explores the birth of a child and the loss of a father with exacting clarity.

In Three Poems, readers will experience Sullivan’s work with the same exhilaration as they might the great modernizing poems of Eliot and Pound, but with the unique perspective of a brilliant new female voice.

Hannah Sullivan lives in London with her husband and two sons and is an Associate Professor of English at New College, Oxford. She received her PhD from Harvard in 2008 and taught in California for four years.

She is currently associate professor of English at New College, Oxford. Her study of modernist writing, The Work of Revision, was published in 2013 and awarded the Rose Mary Crawshay Prize by the British Academy. Her debut poetry collection, Three Poems, was published by Faber in 2018 and was awarded the prestigious TS Eliot Prize.

Three Poems

by Hannah Sullivan

Paperback: 80 pages

Publisher: Faber & Faber; Main edition (18 Jan. 2018)

Language: English

ISBN-10: 9780571337675

ISBN-13: 978-0571337675

ASIN: 0571337678

Product Dimensions: 15.9 x 1.3 x 21 cm

# new poetry

Three Poems

by Hannah Sullivan

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive S-T, Archive S-T, Art & Literature News, Awards & Prizes

Franz Kafka remains one of the most influential writers of the twentieth century.

His novels, stories, and letters are still regarded today as the epitome of the dark, fascinating, and uncanny, a model of the modernist aesthetic.

Peter-André Alt’s landmark biography, Franz Kafka, the Eternal Son, recounts and explores Kafka’s life and literary work throughout the cultural and political upheavals of central Europe.

Alt’s biography explores Franz Kafka’s own view of life and writing as a unity that shaped his identity. He locates links and echoes among the author’s work, life, and surroundings, situating him within the traditions of Prague’s German literature, modernity, psychoanalysis, and philosophy as well as within its Jewish culture, arts, theater, and intellectual tradition.

In this biographical tour de force, Kafka emerges as an observant flaneur and wistful loner, an anxious ascetic, an ecstatic and skeptic, a specialist in terror, and a master of irony. Alt masterfully illuminates Kafka’s life not as source material but as a mirror of his literary genius. Readers begin to see Kafka’s unforgettable novels and stories as shards reflecting the life of their creator.

About the Author

Peter-André André Alt is a German literary scholar and the president of the Free University in Berlin.

Kristine A, Thorsen is a lecturer emeritus of German at Northwestern University.

Franz Kafka, the Eternal Son

A Biography

Contributors

Peter-André Alt (Author)

Kristine Thorsen (Translator)

Publication Date September 2018

Categories Biography

704 pages

Trim Size 7 x 10

ISBN 0-8101-2607-9

Northwestern University Press

-Cloth Text

– $120.00

ISBN 978-0-8101-6243-3

-Paper Text

– $45.00

ISBN 978-0-8101-2607-7

# new books

Franz Kafka

A Biography

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Book Stories, Archive A-B, Archive K-L, Archive K-L, Art & Literature News, Franz Kafka, Kafka, Franz, Kafka, Franz, MONTAIGNE

Ian Buruma, (Den Haag, 1951) is een internationaal befaamd essayist, historicus en Azië-deskundige. Hij schrijft regelmatig voor The New Yorker, The New York Review of Books en in ons eigen land voor NRC Handelsblad, en werkte mee aan documentaires voor de BBC en CNN.

Momenteel is hij hoogleraar Democracy, Human Rights and Journalism aan het Bard College in New York.

Momenteel is hij hoogleraar Democracy, Human Rights and Journalism aan het Bard College in New York.

In 2008 ontving Buruma de Erasmusprijs voor zijn buitengewone bijdrage aan de Nederlandse cultuur.

Tot zijn bekendste boeken horen Occidentalisme, De spiegel van de zonnegodin, Dood van een gezonde roker, Het loon van de schuld en 1945. Biografie van een jaar en Hun beloofde land. Mijn grootouders in tijden van liefde en oorlog. In 2018 verscheen Tokio mon amour. Japanse avonturen, het portret van een jonge schrijver en van de stad die hem mede vormde.

Op donderdag 25 april a.s. ontvangt Ian Buruma de Gouden Ganzenveer 2019.

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, - Book News, Archive A-B, Art & Literature News, Awards & Prizes, PRESS & PUBLISHING

Mels is met zijn vader in het café en mag bier tappen omdat de kastelein meedoet met kaarten.

Hij bedient de paar mannen die op het terras zitten.

Mannen van het soort dat hier eerst verdwaald leek, maar van wie hij nu weet dat het wandelaars zijn die de Wijer nalopen. Van de monding van de beek in de rivier terug naar de bron. Ze dragen hoge laarzen om door de broeklanden en rietvelden te stappen.

Mannen van het soort dat hier eerst verdwaald leek, maar van wie hij nu weet dat het wandelaars zijn die de Wijer nalopen. Van de monding van de beek in de rivier terug naar de bron. Ze dragen hoge laarzen om door de broeklanden en rietvelden te stappen.

Over hun rug kijkt hij mee naar de kaart van het riviertje en het opengeslagen boek op tafel. Hij verbaast zich erover dat de Wijer meer dan honderd kilometer lang is en dat de bron ergens ligt bij een dorp dat Weierwiese heet. En dat het officieel geen beek maar een rivier is. En dat er honderdtachtig soorten vis in zitten, terwijl hij er maar tien kent. En dat hij nog nooit een zoetwaterkreeft met schaarvormige kaken heeft gezien. Geen wonder, want volgens het onderschrift bij het plaatje van het dier is het nog geen halve centimeter groot.

De mannen drinken chocomel. De bierdrinkende kerels die zitten te kaarten, lachen hen uit. Mels is boos, vooral over de opmerkingen van meneer Frans-Joseph. Die scheldt de wandelaars uit voor mietjes en hoerenlopers. Het is extra gênant omdat iedereen weet dat hij zelf een hoerenloper is.

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (087)

wordt vervolgd

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

Dictatuur, schendingen van mensenrechten, milieuvervuiling, verdronken vluchtelingen: dit zijn niet alleen de urgentste kwesties in de wereldpolitiek, maar ook de thema’s in het werk van Ai Weiwei.

Met zijn enorm veelzijdige creativiteit en maatschappelijke engagement zet hij als een van de beroemdste en grootste kunstenaars van onze tijd vrijwel alles op het spel: hij werd gearresteerd, zijn paspoort werd ingenomen, en afgelopen zomer nog sloopten de Chinese autoriteiten zonder waarschuwing zijn studio in Beijing.

Met zijn enorm veelzijdige creativiteit en maatschappelijke engagement zet hij als een van de beroemdste en grootste kunstenaars van onze tijd vrijwel alles op het spel: hij werd gearresteerd, zijn paspoort werd ingenomen, en afgelopen zomer nog sloopten de Chinese autoriteiten zonder waarschuwing zijn studio in Beijing.

Als geen ander kan Ai Weiwei dus vertellen over de verantwoordelijkheid van de kunstenaar. Wat vermag de kunst in een tijd waarin dissidenten worden opgesloten en journalisten zonder pardon het land uit worden gezet?

Hoe ver mag de kunstenaar gaan?

Hoe ver moét hij gaan?

Hoor het bij de Nexus-lezing 2019, The Responsibilities of an Artist.

The Responsibilities of an Artist

Nexus-lezing Ai Weiwei

25 mei 2019

14.30 – 17.30

Aula VU Amsterdamhttps://nexus-instituut.nl/

# meer informatie op website nexus-instituut

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Ai Weiwei, Art & Literature News, AUDIO, CINEMA, RADIO & TV, DICTIONARY OF IDEAS, Nexus Instituut

The Match-Maker

The grill-room clock struck eleven with the respectful unobtrusiveness of one whose mission in life is to be ignored. When the flight of time should really have rendered abstinence and migration imperative the lighting apparatus would signal the fact in the usual way.

Six minutes later Clovis approached the supper-table, in the blessed expectancy of one who has dined sketchily and long ago.

Six minutes later Clovis approached the supper-table, in the blessed expectancy of one who has dined sketchily and long ago.

“I’m starving,” he announced, making an effort to sit down gracefully and read the menu at the same time.

“So I gathered;” said his host, “from the fact that you were nearly punctual. I ought to have told you that I’m a Food Reformer. I’ve ordered two bowls of bread-and-milk and some health biscuits. I hope you don’t mind.”

Clovis pretended afterwards that he didn’t go white above the collar-line for the fraction of a second.

“All the same,” he said, “you ought not to joke about such things. There really are such people. I’ve known people who’ve met them. To think of all the adorable things there are to eat in the world, and then to go through life munching sawdust and being proud of it.”

“They’re like the Flagellants of the Middle Ages, who went about mortifying themselves.”

“They had some excuse,” said Clovis. “They did it to save their immortal souls, didn’t they? You needn’t tell me that a man who doesn’t love oysters and asparagus and good wines has got a soul, or a stomach either. He’s simply got the instinct for being unhappy highly developed.”

Clovis relapsed for a few golden moments into tender intimacies with a succession of rapidly disappearing oysters.

“I think oysters are more beautiful than any religion,” he resumed presently. “They not only forgive our unkindness to them; they justify it, they incite us to go on being perfectly horrid to them. Once they arrive at the supper-table they seem to enter thoroughly into the spirit of the thing. There’s nothing in Christianity or Buddhism that quite matches the sympathetic unselfishness of an oyster. Do you like my new waistcoat? I’m wearing it for the first time to-night.”

“It looks like a great many others you’ve had lately, only worse. New dinner waistcoats are becoming a habit with you.”

“They say one always pays for the excesses of one’s youth; mercifully that isn’t true about one’s clothes. My mother is thinking of getting married.”

“Again!”

“It’s the first time.”

“Of course, you ought to know. I was under the impression that she’d been married once or twice at least.”

“Three times, to be mathematically exact. I meant that it was the first time she’d thought about getting married; the other times she did it without thinking. As a matter of fact, it’s really I who am doing the thinking for her in this case. You see, it’s quite two years since her last husband died.”

“You evidently think that brevity is the soul of widowhood.”

“Well, it struck me that she was getting moped, and beginning to settle down, which wouldn’t suit her a bit. The first symptom that I noticed was when she began to complain that we were living beyond our income. All decent people live beyond their incomes nowadays, and those who aren’t respectable live beyond other peoples. A few gifted individuals manage to do both.”

“It’s hardly so much a gift as an industry.”

“The crisis came,” returned Clovis, “when she suddenly started the theory that late hours were bad for one, and wanted me to be in by one o’clock every night. Imagine that sort of thing for me, who was eighteen on my last birthday.”

“On your last two birthdays, to be mathematically exact.”

“Oh, well, that’s not my fault. I’m not going to arrive at nineteen as long as my mother remains at thirty-seven. One must have some regard for appearances.”

“Perhaps your mother would age a little in the process of settling down.”

“That’s the last thing she’d think of. Feminine reformations always start in on the failings of other people. That’s why I was so keen on the husband idea.”

“Did you go as far as to select the gentleman, or did you merely throw out a general idea, and trust to the force of suggestion?”

“If one wants a thing done in a hurry one must see to it oneself. I found a military Johnny hanging round on a loose end at the club, and took him home to lunch once or twice. He’d spent most of his life on the Indian frontier, building roads, and relieving famines and minimizing earthquakes, and all that sort of thing that one does do on frontiers. He could talk sense to a peevish cobra in fifteen native languages, and probably knew what to do if you found a rogue elephant on your croquet-lawn; but he was shy and diffident with women. I told my mother privately that he was an absolute woman-hater; so, of course, she laid herself out to flirt all she knew, which isn’t a little.”

“And was the gentleman responsive?”

“I hear he told some one at the club that he was looking out for a Colonial job, with plenty of hard work, for a young friend of his, so I gather that he has some idea of marrying into the family.”

“You seem destined to be the victim of the reformation, after all.”

Clovis wiped the trace of Turkish coffee and the beginnings of a smile from his lips, and slowly lowered his dexter eyelid. Which, being interpreted, probably meant, “I DON’T think!”

The Match-Maker

From ‘The Chronicles of Clovis’

by Saki (H. H. Munro)

(1870 – 1916)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Saki, Saki, The Art of Reading

Poète noir

Poète noir, un sein de pucelle

te hante,

poète aigri, la vie bout

et la ville brûle,

et le ciel se résorbe en pluie,

ta plume gratte au cœur de la vie.

Forêt, forêt, des yeux fourmillent

sur les pignons multipliés ;

cheveux d’orage, les poètes

enfourchent des chevaux, des chiens.

Les yeux ragent, les langues tournent,

le ciel afflue dans les narines

comme un lait nourricier et bleu ;

je suis suspendu à vos bouches

femmes, cœurs de vinaigre durs.

Antonin Artaud

(1896 — 1948)

Poète noir

Poème

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Antonin Artaud, Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Artaud, Antonin

Wir leben im Zeitalter des Gedichts.

Die Poesie ist auf Erfolgskurs, schließlich sind einige der begabtesten Autoren einer ganzen Generation in der Lyrikszene zu finden. Warum das so ist und was die Lyrik der Gegenwart auszeichnet, erzählt Christian Metz in seinem grundlegenden Essay.

Angetrieben von den epochalen Veränderungen unserer Zeit forciert die Lyrik der Gegenwart ein poetisches Denken. Es ist ein Denken mit poetischen Mitteln, das der sinnlichen Erfahrung, der Leidenschaft und dem Spiel Raum gibt. In dieses poetische Denken führt Metz systematisch ein. Ausgehend von ihren Gemeinsamkeiten folgt Metz einigen der wichtigsten Autorinnen und Autoren der neuen Lyrik – wie Monika Rinck und Jan Wagner, Ann Cotten und Steffen Popp – in ihr poetisches Universum.

Angetrieben von den epochalen Veränderungen unserer Zeit forciert die Lyrik der Gegenwart ein poetisches Denken. Es ist ein Denken mit poetischen Mitteln, das der sinnlichen Erfahrung, der Leidenschaft und dem Spiel Raum gibt. In dieses poetische Denken führt Metz systematisch ein. Ausgehend von ihren Gemeinsamkeiten folgt Metz einigen der wichtigsten Autorinnen und Autoren der neuen Lyrik – wie Monika Rinck und Jan Wagner, Ann Cotten und Steffen Popp – in ihr poetisches Universum.

Christian Metz, geboren 1975, nach seiner Rückkehr von der Cornell University Stipendiat der Alexander von Humboldt-Stiftung an der LMU in München. Jahrelang wissenschaftlicher Mitarbeiter am Institut für deutsche Literatur und ihre Didaktik an der Goethe-Universität Frankfurt und Literaturkritiker für die »Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung«. Promotion mit einer Arbeit zur »Narratologie der Liebe«. Habilitation zum Thema: »Kitzel. Studien zur Kultur einer menschlichen Empfindung«, deren Monographie bei S. Fischer Wissenschaft im Herbst 2019 erscheint. Lehraufträge an der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin und der Universität Tromsø (Norwegen). Schwerpunkte in Forschung und Lehre: Literatur vom 17. Jahrhundert bis zur Gegenwart, Literaturtheorie, Anthropologie und Literatur. Gemeinsam mit Ina Hartwig und Oliver Vogel Herausgeber der »Neuen Rundschau. Gegenwartsliteratur!« (Heft 2015/1).

Christian Metz

Poetisch denken

Die Lyrik der Gegenwart

Erscheinungstermin: 04.10.2018

Umfang: 432 Seiten

Paperback

ISBN-10: 3100024400

ISBN-13: 978-3100024404

Verlag: S. FISCHER

Lyrik

Sprache: Deutsch

Nr. 473 in Literaturkritik

Nr. 14136 in Film, Kunst & Kultur

432 Seiten

13,4 x 3,2 x 21,5 cm

Paperback Preis € 20,00

# new books

Christian Metz

Poetisch denken

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive M-N, Archive M-N, Art & Literature News, MODERN POETRY, STREET POETRY

A Terre

(Being the philosophy of many Soldiers.)

Sit on the bed; I’m blind, and three parts shell.

Be careful; can’t shake hands now; never shall.

Both arms have mutinied against me,—brutes.

My fingers fidget like ten idle brats.

I tried to peg out soldierly,—no use!

One dies of war like any old disease.

This bandage feels like pennies on my eyes.

I have my medals?—Discs to make eyes close.

My glorious ribbons?—Ripped from my own back

In scarlet shreds. (That’s for your poetry book.)

A short life and a merry one, my buck!

We used to say we’d hate to live dead-old,—

Yet now … I’d willingly be puffy, bald,

And patriotic. Buffers catch from boys

At least the jokes hurled at them. I suppose

Little I’d ever teach a son, but hitting,

Shooting, war, hunting, all the arts of hurting.

Well, that’s what I learnt,—that, and making money.

Your fifty years ahead seem none too many?

Tell me how long I’ve got? God! For one year

To help myself to nothing more than air!

One Spring! Is one too good to spare, too long?

Spring wind would work its own way to my lung,

And grow me legs as quick as lilac-shoots.

My servant’s lamed, but listen how he shouts!

When I’m lugged out, he’ll still be good for that.

Here in this mummy-case, you know, I’ve thought

How well I might have swept his floors for ever.

I’d ask no night off when the bustle’s over,

Enjoying so the dirt. Who’s prejudiced

Against a grimed hand when his own’s quite dust,

Less live than specks that in the sun-shafts turn,

Less warm than dust that mixes with arms’ tan?

I’d love to be a sweep, now, black as Town,

Yes, or a muckman. Must I be his load?

O Life, Life, let me breathe,—a dug-out rat!

Not worse than ours the lives rats lead—

Nosing along at night down some safe rut,

They find a shell-proof home before they rot.

Dead men may envy living mites in cheese,

Or good germs even. Microbes have their joys,

And subdivide, and never come to death.

Certainly flowers have the easiest time on earth.

“I shall be one with nature, herb, and stone,”

Shelley would tell me. Shelley would be stunned:

The dullest Tommy hugs that fancy now.

“Pushing up daisies,” is their creed, you know.

To grain, then, go my fat, to buds my sap,

For all the usefulness there is in soap.

D’you think the Boche will ever stew man-soup?

Some day, no doubt, if …

Friend, be very sure

I shall be better off with plants that share

More peaceably the meadow and the shower.

Soft rains will touch me,— as they could touch once,

And nothing but the sun shall make me ware.

Your guns may crash around me. I’ll not hear;

Or, if I wince, I shall not know I wince.

Don’t take my soul’s poor comfort for your jest.

Soldiers may grow a soul when turned to fronds,

But here the thing’s best left at home with friends.

My soul’s a little grief, grappling your chest,

To climb your throat on sobs; easily chased

On other sighs and wiped by fresher winds.

Carry my crying spirit till it’s weaned

To do without what blood remained these wounds.

Wilfred Owen

(1893 – 1918)

A Terre (Poem)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Archive O-P, Galerie des Morts, Owen, Wilfred, WAR & PEACE

THE BOY AND THE BAYONET

It was June, and nearing the closing time of school. The air was full of the sound of bustle and preparation for the final exercises, field day, and drills. Drills especially, for nothing so gladdens the heart of the Washington mother, be she black or white, as seeing her boy in the blue cadet’s uniform, marching proudly to the huzzas of an admiring crowd. Then she forgets the many nights when he has come in tired out and dusty from his practice drill, and feels only the pride and elation of the result.

Although Tom did all he could outside of study hours, there were many days of hard work for Hannah Davis, when her son went into the High School. But she took it upon herself gladly, since it gave Bud the chance to learn, that she wanted him to have. When, however, he entered the Cadet Corps it seemed to her as if the first steps toward the fulfilment of all her hopes had been made. It was a hard pull to her, getting the uniform, but Bud himself helped manfully, and when his mother saw him rigged out in all his regimentals, she felt that she had not toiled in vain. And in fact it was worth all the trouble and expense just to see the joy and pride of “little sister,” who adored Bud.

Although Tom did all he could outside of study hours, there were many days of hard work for Hannah Davis, when her son went into the High School. But she took it upon herself gladly, since it gave Bud the chance to learn, that she wanted him to have. When, however, he entered the Cadet Corps it seemed to her as if the first steps toward the fulfilment of all her hopes had been made. It was a hard pull to her, getting the uniform, but Bud himself helped manfully, and when his mother saw him rigged out in all his regimentals, she felt that she had not toiled in vain. And in fact it was worth all the trouble and expense just to see the joy and pride of “little sister,” who adored Bud.

As the time for the competitive drill drew near there was an air of suppressed excitement about the little house on “D” Street, where the three lived. All day long “little sister,” who was never very well and did not go to school, sat and looked out of the window on the uninteresting prospect of a dusty thoroughfare lined on either side with dull red brick houses, all of the same ugly pattern, interspersed with older, uglier, and viler frame shanties. In the evening Hannah hurried home to get supper against the time when Bud should return, hungry and tired from his drilling, and the chore work which followed hard upon its heels.

Things were all cheerful, however, for as they applied themselves to the supper, the boy, with glowing face, would tell just how his company “A” was getting on, and what they were going to do to companies “B” and “C.” It was not boasting so much as the expression of a confidence, founded upon the hard work he was doing, and Hannah and the “little sister” shared that with him.

The child often, listening to her brother, would clap her hands or cry, “Oh, Bud, you’re just splendid an’ I know you’ll beat ’em.”

“If hard work’ll beat ’em, we’ve got ’em beat,” Bud would reply, and Hannah, to add an admonitory check to her own confidence, would break in with, “Now, don’t you be too sho’, son; dey ain’t been no man so good dat dey wasn’t somebody bettah.” But all the while her face and manner were disputing what her words expressed.

The great day came, and it was a wonderful crowd of people that packed the great baseball grounds to overflowing. It seemed that all of Washington’s coloured population was out, when there were really only about one-tenth of them there. It was an enthusiastic, banner-waving, shouting, hallooing crowd. Its component parts were strictly and frankly partisan, and so separated themselves into sections differentiated by the colours of the flags they carried and the ribbons they wore. Side yelled defiance at side, and party bantered party. Here the blue and white of Company “A” flaunted audaciously on the breeze beside the very seats over which the crimson and gray of “B” were flying, and these in their turn nodded defiance over the imaginary barrier between themselves and “C’s” black and yellow.

The band was thundering out “Sousa’s High School Cadet’s March,” the school officials, the judges, and reporters, and some with less purpose were bustling about, discussing and conferring. Altogether doing nothing much with beautiful unanimity. All was noise, hurry, gaiety, and turbulence. In the midst of it all, with blue and white rosettes pinned on their breasts, sat two spectators, tense and silent, while the breakers of movement and sound struck and broke around them. It meant too much to Hannah and “little sister” for them to laugh and shout. Bud was with Company “A,” and so the whole programme was more like a religious ceremonial to them. The blare of the brass to them might have been the trumpet call to battle in old Judea, and the far-thrown tones of the megaphone the voice of a prophet proclaiming from the hill-top.

Hannah’s face glowed with expectation, and “little sister” sat very still and held her mother’s hand save when amid a burst of cheers Company “A” swept into the parade ground at a quick step, then she sprang up, crying shrilly, “There’s Bud, there’s Bud, I see him,” and then settled back into her seat overcome with embarrassment. The mother’s eyes danced as soon as the sister’s had singled out their dear one from the midst of the blue-coated boys, and it was an effort for her to keep from following her little daughter’s example even to echoing her words.

Company “A” came swinging down the field toward the judges in a manner that called for more enthusiastic huzzas that carried even the Freshman of other commands “off their feet.” They were, indeed, a set of fine-looking young fellows, brisk, straight, and soldierly in bearing. Their captain was proud of them, and his very step showed it. He was like a skilled operator pressing the key of some great mechanism, and at his command they moved like clockwork. Seen from the side it was as if they were all bound together by inflexible iron bars, and as the end man moved all must move with him. The crowd was full of exclamations of praise and admiration, but a tense quiet enveloped them as Company “A” came from columns of four into line for volley firing. This was a real test; it meant not only grace and precision of movement, singleness of attention and steadiness, but quickness tempered by self-control. At the command the volley rang forth like a single shot. This was again the signal for wild cheering and the blue and white streamers kissed the sunlight with swift impulsive kisses. Hannah and Little Sister drew closer together and pressed hands.

The “A” adherents, however, were considerably cooled when the next volley came out, badly scattering, with one shot entirely apart and before the rest. Bud’s mother did not entirely understand the sudden quieting of the adherents; they felt vaguely that all was not as it should be, and the chill of fear laid hold upon their hearts. What if Bud’s company, (it was always Bud’s company to them), what if his company should lose. But, of course, that couldn’t be. Bud himself had said that they would win. Suppose, though, they didn’t; and with these thoughts they were miserable until the cheering again told them that the company had redeemed itself.

Someone behind Hannah said, “They are doing splendidly, they’ll win, they’ll win yet in spite of the second volley.”

Company “A,” in columns of fours, had executed the right oblique in double time, and halted amid cheers; then formed left halt into line without halting. The next movement was one looked forward to with much anxiety on account of its difficulty. The order was marching by fours to fix or unfix bayonets. They were going at a quick step, but the boys’ hands were steady—hope was bright in their hearts. They were doing it rapidly and freely, when suddenly from the ranks there was the bright gleam of steel lower down than it should have been. A gasp broke from the breasts of Company “A’s” friends. The blue and white drooped disconsolately, while a few heartless ones who wore other colours attempted to hiss. Someone had dropped his bayonet. But with muscles unquivering, without a turned head, the company moved on as if nothing had happened, while one of the judges, an army officer, stepped into the wake of the boys and picked up the fallen steel.

No two eyes had seen half so quickly as Hannah and Little Sister’s who the blunderer was. In the whole drill there had been but one figure for them, and that was Bud, Bud, and it was he who had dropped his bayonet. Anxious, nervous with the desire to please them, perhaps with a shade too much of thought of them looking on with their hearts in their eyes, he had fumbled, and lost all that he was striving for. His head went round and round and all seemed black before him.

He executed the movements in a dazed way. The applause, generous and sympathetic, as his company left the parade ground, came to him from afar off, and like a wounded animal he crept away from his comrades, not because their reproaches stung him, for he did not hear them, but because he wanted to think what his mother and “Little Sister” would say, but his misery was as nothing to that of the two who sat up there amid the ranks of the blue and white holding each other’s hands with a despairing grip. To Bud all of the rest of the contest was a horrid nightmare; he hardly knew when the three companies were marched back to receive the judges’ decision. The applause that greeted Company “B” when the blue ribbons were pinned on the members’ coats meant nothing to his ears. He had disgraced himself and his company. What would his mother and his “Little Sister” say?

To Hannah and “Little Sister,” as to Bud, all of the remainder of the drill was a misery. The one interest they had had in it failed, and not even the dropping of his gun by one of Company “E” when on the march, halting in line, could raise their spirits. The little girl tried to be brave, but when it was all over she was glad to hurry out before the crowd got started and to hasten away home. Once there and her tears flowed freely; she hid her face in her mother’s dress, and sobbed as if her heart would break.

“Don’t cry, Baby! don’t cry, Lammie, dis ain’t da las’ time da wah goin’ to be a drill. Bud’ll have a chance anotha time and den he’ll show ’em somethin’; bless you, I spec’ he’ll be a captain.” But this consolation of philosophy was nothing to “Little Sister.” It was so terrible to her, this failure of Bud’s. She couldn’t blame him, she couldn’t blame anyone else, and she had not yet learned to lay all such unfathomed catastrophes at the door of fate. What to her was the thought of another day; what did it matter to her whether he was a captain or a private? She didn’t even know the meaning of the words, but “Little Sister,” from the time she knew Bud was a private, knew that that was much better than being captain or any of those other things with a long name, so that settled it.

Her mother finally set about getting the supper, while “Little Sister” drooped disconsolately in her own little splint-bottomed chair. She sat there weeping silently until she heard the sound of Bud’s step, then she sprang up and ran away to hide. She didn’t dare to face him with tears in her eyes. Bud came in without a word and sat down in the dark front room.

“Dat you, Bud?” asked his mother.

“Yassum.”

“Bettah come now, supper’s puty ‘nigh ready.”

“I don’ want no supper.”

“You bettah come on, Bud, I reckon you mighty tired.”

He did not reply, but just then a pair of thin arms were put around his neck and a soft cheek was placed close to his own.

“Come on, Buddie,” whispered “Little Sister,” “Mammy an’ me know you didn’t mean to do it, an’ we don’ keer.”

Bud threw his arms around his little sister and held her tightly.

“It’s only you an’ ma I care about,” he said, “though I am sorry I spoiled the company’s drill; they say “B” would have won anyway on account of our bad firing, but I did want you and ma to be proud.”

“We is proud,” she whispered, “we’s mos’ prouder dan if you’d won,” and pretty soon she led him by the hand out to supper.

Hannah did all she could to cheer the boy and to encourage him to hope for next year, but he had little to say in reply, and went to bed early.

In the morning, though it neared school time, Bud lingered around and seemed in no disposition to get ready to go.

“Bettah git ready fer school,” said Hannah cheerily to him.

“I don’t believe I want to go any more,” Bud replied.

“Not go any more? Why ain’t you shamed to talk that way! O’ cose you a goin’ to school.”

“I’m ashamed to show my face to the boys.”

“What you say about de boys? De boys ain’t a-goin’ to give you no edgication when you need it.”

“Oh, I don’t want to go, ma; you don’t know how I feel.”

“I’m kinder sorry I let you go into dat company,” said Hannah musingly; “’cause it was de teachin’ I wanted you to git, not de prancin’ and steppin’; but I did t’ink it would make mo’ of a man of you, an’ it ain’t. Yo’ pappy was a po’ man, ha’d wo’kin’, an’ he wasn’t high-toned neither, but from the time I first see him to the day of his death I nevah seen him back down because he was afeared of anything,” and Hannah turned to her work.

“Little Sister” went up to Bud and slipped her hand in his. “You ain’t a-goin’ to back down, is you, Buddie?” she said.

“No,” said Bud stoutly, as he braced his shoulders, “I’m a-goin’.”

But no persuasion could make him wear his uniform.

The boys were a little cold to him, and some were brutal. But most of them recognised the fact that what had happened to Tom Harris might have happened to any one of them. Besides, since the percentage had been shown, it was found that “B” had outpointed them in many ways, and so their loss was not due to the one grave error. Bud’s heart sank when he dropped into his seat in the Assembly Hall to find seated on the platform one of the blue-coated officers who had acted as judge the day before. After the opening exercises were over he was called upon to address the school. He spoke readily and pleasantly, laying especial stress upon the value of discipline; toward the end of his address he said: “I suppose Company ‘A’ is heaping accusations upon the head of the young man who dropped his bayonet yesterday.” Tom could have died. “It was most regrettable,” the officer continued, “but to me the most significant thing at the drill was the conduct of that cadet afterward. I saw the whole proceeding; I saw that he did not pause for an instant, that he did not even turn his head, and it appeared to me as one of the finest bits of self-control I had ever seen in any youth; had he forgotten himself for a moment and stopped, however quickly, to secure the weapon, the next line would have been interfered with and your whole movement thrown into confusion.” There were a half hundred eyes glancing furtively at Bud, and the light began to dawn in his face. “This boy has shown what discipline means, and I for one want to shake hands with him, if he is here.”

When he had concluded the Principal called Bud forward, and the boys, even his detractors, cheered as the officer took his hand.

“Why are you not in uniform, sir?” he asked.

“I was ashamed to wear it after yesterday,” was the reply.

“Don’t be ashamed to wear your uniform,” the officer said to him, and Bud could have fallen on his knees and thanked him.

There were no more jeers from his comrades now, and when he related it all at home that evening there were two more happy hearts in that South Washington cottage.

“I told you we was more prouder dan if you’d won,” said “Little Sister.”

“An’ what did I tell you ’bout backin’ out?” asked his mother.

Bud was too happy and too busy to answer; he was brushing his uniform.

Paul Laurence Dunbar

(1872 – 1906)

The Boy and The Bayonet

From The Heart Of Happy Hollow, a collection of short stories reprinted in 1904 by Dodd, Mead and Company, New York.

Short Story

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Archive C-D, Dunbar, Paul Laurence, Dunbar, Paul Laurence, Paul Laurence Dunbar, Paul Laurence Dunbar

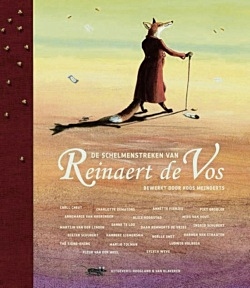

Terwijl Reinaert de Vos tijdens het monopoly-spelen met zijn kinderen stiekem een briefje van duizend uit de bank jatte en zich te goed deed aan een kipkluifje, verklaarde Koning Nobel in de paleistuin de jaarlijkse Hofdag voor geopend.

Met de opening van de Hofdag opent ook de fonkelende bewerking die Koos Meinderts maakte van het bekendste epos uit de Middelnederlandse literatuur: Van den Vos Reynaerde.

Met de opening van de Hofdag opent ook de fonkelende bewerking die Koos Meinderts maakte van het bekendste epos uit de Middelnederlandse literatuur: Van den Vos Reynaerde.

In achttien hoofdstukken verhaalt Meinderts over de belevenissen van de geslepen vos Reinaert en zijn beklagenswaardige tegenspelers, waaronder Tibeert de Kater, Bruun de Beer en Cuwaert de Haas. Elk hoofdstuk werd geïllustreerd door een vooraanstaand kinderboekillustrator.

Koos Meinderts:

De schelmenstreken van Reinaert de Vos

1e druk

EAN: 978 90 8967 273 5

NUR: 274

Verschenen 12-11-2018

Formaat: 23,5 x 27 cm

48 bladzijden

Gebondend

Bindwijze Hardcover

Genre Kinderboeken

Uitgever Hoogland & Van Klaveren, Uitgeverij

Taal Nederlands

Illustraties Charlotte Dematons e.a.

Prijs: € 17,50

# New books

Koos Meinderts

Reinaert de Vos

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Book Stories, Archive M-N, Archive Q-R, Archive Q-R, Art & Literature News, Grimm, Andersen e.o.: Fables, Fairy Tales & Stories

Een tik op zijn schouder. Hij trekt de plaid van zijn gezicht en opent zijn ogen. Het is Afke.

`Je was tegen iemand aan het praten.’

`Ik praatte met Tijger en Thija.’

`Over school?’

`Goh, dat ik zo duidelijk praat als ik droom.’

Ze helpt hem van het bed in zijn stoel. Ze helpt hem vaak. Tegenover haar voelt hij niet de gêne die hij wel voelt bij zijn vrouw en zijn dochter. Soms is ook Zhia erbij. Dan helpen ze hem als twee jonge verpleegsters.

Zijn vrouw haat het als de meisjes boven zijn, al weet hij niet waarom.

`Je bent nat van het zweet.’

`Je bent nat van het zweet.’

`Dat komt door de medicijnen. Ik zweet nog als het vriest.’

Ze trekt zijn overhemd uit.

`De haren op je rug zijn nog zwart.’ Ze droogt zijn rug en hals. `Had je vroeger zwart haar? Vonden de meisjes je knap?’

`Er waren hier niet zo veel meisjes. Het dorp was nog klein.’

`En die paar dan?’

`Thija vond me knap. Maar ik denk dat ze Tijger knapper vond.’

`En oma?’

`Toen zij een meisje was? Ze wilde me alleen hebben omdat ze jaloers was op Thija. Dat denk ik nu.’

`Vond jij haar knap?’

`Anders.’

`Je was toch wel verliefd op haar? Je bent toch met haar getrouwd?’

`Het liep nu eenmaal zo. Er waren hier maar een paar meisjes, dat zei ik toch. Kemp wilde haar ook.’

`Ben je met haar getrouwd omdat je haar niet aan Kemp gunde?’

`Ja.’ Tegen haar kan hij alleen maar eerlijk zijn.

`Wel vreemd’, zegt ze. `Nu heb ik precies zulke grootvaders zoals jij had.’

`Hoezo?’

`Jij zegt toch altijd dat ze elkaar niet mochten.’

Ze rijdt hem voor de wastafel.

`Moet ik je scheren?’

`Ik doe het zelf.’

Ze pakt het mes uit de la, haalt het uit de houder en pakt kwast en scheerzeep uit de kast.

`Scheerzeep ruikt lekker.’

`Het ruikt naar jongens.’

`Jongens! Was je gelukkig als kind?’

`Alleen toen Tijger en Thija er nog waren.’

`Er waren toch ook anderen die van je hielden.’

`Wie dan?’

`Je moeder.’

`Dat is ook zo.’

`Ik hou ook van je.’

Hij ziet haar oprechte gezicht in de spiegel.

`Het is waar’, zegt hij. `Jij houdt net zo veel van mij als ik van jou. En je opa Kemp?’

`Van hem hou ik ook. Anders. Zal ik je inzepen?’ Ze haalt de kwast door het schuim en zeept hem zorgvuldig in. `Ik kan je ook scheren. Laat mij het maar doen. Jij snijdt je te vaak.’

`Ik heb een zware baard. Een scheerapparaat werkt niet bij mij.’

`Voortaan scheer ik je wel.’ Ze zet het mes aan. Protesteren helpt niet. Hij voelt hoe zacht het mes over zijn huid glijdt. In de spiegel ziet hij de inspanning op haar gezicht. Hij blijft muisstil zitten. Ze wil het beter doen dan hij.

Terwijl ze met hem bezig is, hoort hij een zacht gebrom, door de muur heen. Net alsof in het buurhuis een of ander apparaat aanstaat. Hij spant zich in om het geluid te kunnen traceren. Het kan ook een vliegtuig zijn, ver weg.

`Klaar’, zegt ze triomfantelijk en ze bet zijn gezicht. `Geen bloed. Zie je dat ik het beter kan.’

`Mooi. Je moet verpleegster worden.’

`Later ga ik met dieren werken. In een circus. Of bij een dierenarts. Of in een asiel. Zhia wordt verpleegster. Of dokter. Ze wil naar Afrika. Of in een kindertehuis.’

`Dat jullie al zo goed weten wat je wilt! Toen ik twaalf was, wist ik nog niets.’

Hij hoort de voordeur dichtslaan.

`Kan ik boven komen?’

`Kom maar’, roept Afke.

Zhia holt de trap op en komt de kamer binnen.

`Bij de silo is een ongeluk gebeurd’, hijgt Zhia.

`Ernstig?’ schrikt Mels.

`Een witte muis is van het dak gevallen. Recht in de bek van een buizerd.’

`Dat is dubbele pech’, zegt Mels.

`Of dubbel geluk’, zegt Zhia. `Misschien was de muis blij dat ze werd opgevreten en dat ze niet te pletter viel.’

`Van dat laatste had ze niets gevoeld’, zegt Mels. `Maar zo’n roofvogel die je verslindt, dat is wel erg.’

`Het is niet waar’, zegt Zhia. `Het was geen witte muis, het was een zwarte.’

Afke trekt hem een overhemd aan en maakt de knoopjes dicht.

`We moeten naar school. Na het avondeten kom ik weer, als je zin hebt in vertellen.’

`Daar heb ik altijd zin in.’

Hij hoort hen de trap af lopen. De deur valt dicht.

Ze hollen weg. Hij luistert tot hij niets meer hoort in de straat. Hij weet weer voor wie hij leeft.

Hij rolt naar de kast en pakt het boek. Elke dag kijkt hij er even in. Het boek dat Thija aan Tijger heeft gegeven toen hij twaalf werd, maar dat hij niet wilde. `Chine, pays inconnu.’ `Les couleurs pastel de la Chine’, leest hij onder een foto van een rivier van blauw krijt. De oevers zijn van pastelkleurig paars, de lucht is blauw en vet van de regen en gepokt met zwarte ganzen die zich op het water laten vallen. Boten met rieten daken, met naakte jongens voorop die met een stok de diepte peilen, drijven op het water.

De foto van een riviertje van blauw porselein, en een man in een bootje van bamboe, omringd door groenten met de kleur van gras. `Un homme transporte des légumes’.

Hij zet het boek terug, rolt naar het bureau en opent het album met de levenslopen van de directeuren van de fabriek. Hun levensbeschrijvingen, hun foto’s en doodsprentjes. Hij is bezig ze te ordenen, er een lijn in te krijgen.

Een grote leugen is het doodsprentje van Frans-Joseph Hubben, waarop te lezen staat dat hij zijn leven lang gehoorzaam aan God is geweest en een goed en trouw echtgenoot en vader was. Mels weet beter. Meneer Frans-Joseph kwam zelden in de kerk. Vlak na de verkoop van de fabriek is hij in Zwitserland gestorven aan een hartaanval, naar men zegt nadat ze hem uit een café hadden gezet waar hij vrouwen lastigviel.

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (086)

wordt vervolgd

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature