Fleurs du Mal Magazine

If I should die

If I should die,

And you should live,

And time should gurgle on,

And morn should beam,

And noon should burn,

As it has usual done;

If birds should build as early,

And bees as bustling go,—

One might depart at option

From enterprise below!

’T is sweet to know that stocks will stand

When we with daisies lie,

That commerce will continue,

And trades as briskly fly.

It makes the parting tranquil

And keeps the soul serene,

That gentlemen so sprightly

Conduct the pleasing scene!

Emily Dickinson

(1830-1886)

If I should die

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Dickinson, Emily

The Flying Man

The Ethnologist looked at the bhimraj feather thoughtfully. “They seemed loth to part with it,” he said.

“It is sacred to the Chiefs,” said the lieutenant; “just as yellow silk, you know, is sacred to the Chinese Emperor.”

The Ethnologist did not answer. He hesitated. Then opening the topic abruptly, “What on earth is this cock-and-bull story they have of a flying man?”

The lieutenant smiled faintly. “What did they tell you?”

The lieutenant smiled faintly. “What did they tell you?”

“I see,” said the Ethnologist, “that you know of your fame.”

The lieutenant rolled himself a cigarette. “I don’t mind hearing about it once more. How does it stand at present?”

“It’s so confoundedly childish,” said the Ethnologist, becoming irritated. “How did you play it off upon them?”

The lieutenant made no answer, but lounged back in his folding-chair, still smiling.

“Here am I, come four hundred miles out of my way to get what is left of the folk-lore of these people, before they are utterly demoralised by missionaries and the military, and all I find are a lot of impossible legends about a sandy-haired scrub of an infantry lieutenant. How he is invulnerable — how he can jump over elephants — how he can fly. That’s the toughest nut. One old gentleman described your wings, said they had black plumage and were not quite as long as a mule. Said he often saw you by moonlight hovering over the crests out towards the Shendu country. — Confound it, man!”

The lieutenant laughed cheerfully. “Go on,” he said. “Go on.”

The Ethnologist did. At last he wearied. “To trade so,” he said, “on these unsophisticated children of the mountains. How could you bring yourself to do it, man?”

“I’m sorry,” said the lieutenant, “but truly the thing was forced upon me. I can assure you I was driven to it. And at the time I had not the faintest idea of how the Chin imagination would take it. Or curiosity. I can only plead it was an indiscretion and not malice that made me replace the folk-lore by a new legend. But as you seem aggrieved, I will try and explain the business to you.

“It was in the time of the last Lushai expedition but one, and Walters thought these people you have been visiting were friendly. So, with an airy confidence in my capacity for taking care of myself, he sent me up the gorge — fourteen miles of it — with three of the Derbyshire men and half a dozen Sepoys, two mules, and his blessing, to see what popular feeling was like at that village you visited. A force of ten — not counting the mules — fourteen miles, and during a war! You saw the road?”

“Road!” said the Ethnologist.

“It’s better now than it was. When we went up we had to wade in the river for a mile where the valley narrows, with a smart stream frothing round our knees and the stones as slippery as ice. There it was I dropped my rifle. Afterwards the Sappers blasted the cliff with dynamite and made the convenient way you came by. Then below, where those very high cliffs come, we had to keep on dodging across the river — I should say we crossed it a dozen times in a couple of miles.

“We got in sight of the place early the next morning. You know how it lies, on a spur halfway between the big hills, and as we began to appreciate how wickedly quiet the village lay under the sunlight, we came to a stop to consider.

“At that they fired a lump of filed brass idol at us, just by way of a welcome. It came twanging down the slope to the right of us where the boulders are, missed my shoulder by an inch or so, and plugged the mule that carried all the provisions and utensils. I never heard such a death-rattle before or since. And at that we became aware of a number of gentlemen carrying matchlocks, and dressed in things like plaid dusters, dodging about along the neck between the village and the crest to the east.

“‘Right about face,’ I said. ‘Not too close together.’

“And with that encouragement my expedition of ten men came round and set off at a smart trot down the valley again hitherward. We did not wait to save anything our dead had carried, but we kept the second mule with us — he carried my tent and some other rubbish — out of a feeling of friendship.

“So ended the battle — ingloriously. Glancing back, I saw the valley dotted with the victors, shouting and firing at us. But no one was hit. These Chins and their guns are very little good except at a sitting shot. They will sit and finick over a boulder for hours taking aim, and when they fire running it is chiefly for stage effect. Hooker, one of the Derbyshire men, fancied himself rather with the rifle, and stopped behind for half a minute to try his luck as we turned the bend. But he got nothing.

“I’m not a Xenophon to spin much of a yarn about my retreating army. We had to pull the enemy up twice in the next two miles when he became a bit pressing, by exchanging shots with him, but it was a fairly monotonous affair — hard breathing chiefly — until we got near the place where the hills run in towards the river and pinch the valley into a gorge. And there we very luckily caught a glimpse of half a dozen round black heads coming slanting-ways over the hill to the left of us — the east that is — and almost parallel with us.

“At that I called a halt. ‘Look here,’ says I to Hooker and the other Englishmen; ‘what are we to do now?’ and I pointed to the heads.

“‘Headed orf, or I’m a nigger,’ said one of the men.

“‘We shall be,’ said another. ‘You know the Chin way, George?’

“‘They can pot every one of us at fifty yards,’ says Hooker, ‘in the place where the river is narrow. It’s just suicide to go on down.’

“I looked at the hill to the right of us. It grew steeper lower down the valley, but it still seemed climbable. And all the Chins we had seen hitherto had been on the other side of the stream.

“‘It’s that or stopping,’ says one of the Sepoys.

“So we started slanting up the hill. There was something faintly suggestive of a road running obliquely up the face of it, and that we followed. Some Chins presently came into view up the valley, and I heard some shots. Then I saw one of the Sepoys was sitting down about thirty yards below us. He had simply sat down without a word, apparently not wishing to give trouble. At that I called a halt again; I told Hooker to try another shot, and went back and found the man was hit in the leg. I took him up, carried him along to put him on the mule — already pretty well laden with the tent and other things which we had no time to take off. When I got up to the rest with him, Hooker had his empty Martini in his hand, and was grinning and pointing to a motionless black spot up the valley. All the rest of the Chins were behind boulders or back round the bend. ‘Five hundred yards,’ says Hooker, ‘if an inch. And I’ll swear I hit him in the head.’

“So we started slanting up the hill. There was something faintly suggestive of a road running obliquely up the face of it, and that we followed. Some Chins presently came into view up the valley, and I heard some shots. Then I saw one of the Sepoys was sitting down about thirty yards below us. He had simply sat down without a word, apparently not wishing to give trouble. At that I called a halt again; I told Hooker to try another shot, and went back and found the man was hit in the leg. I took him up, carried him along to put him on the mule — already pretty well laden with the tent and other things which we had no time to take off. When I got up to the rest with him, Hooker had his empty Martini in his hand, and was grinning and pointing to a motionless black spot up the valley. All the rest of the Chins were behind boulders or back round the bend. ‘Five hundred yards,’ says Hooker, ‘if an inch. And I’ll swear I hit him in the head.’

“I told him to go and do it again, and with that we went on again.

“Now the hillside kept getting steeper as we pushed on, and the road we were following more and more of a shelf. At last it was mere cliff above and below us. ‘It’s the best road I have seen yet in Chin Lushai land,’ said I to encourage the men, though I had a fear of what was coming.

“And in a few minutes the way bent round a corner of the cliff. Then, finis! the ledge came to an end.

“As soon as he grasped the position one of the Derbyshire men fell a-swearing at the trap we had fallen into. The Sepoys halted quietly. Hooker grunted and reloaded, and went back to the bend.

“Then two of the Sepoy chaps helped their comrade down and began to unload the mule.

“Now, when I came to look about me, I began to think we had not been so very unfortunate after all. We were on a shelf perhaps ten yards across it at widest. Above it the cliff projected so that we could not be shot down upon, and below was an almost sheer precipice of perhaps two or three hundred feet. Lying down we were invisible to anyone across the ravine. The only approach was along the ledge, and on that one man was as good as a host. We were in a natural stronghold, with only one disadvantage, our sole provision against hunger and thirst was one live mule. Still we were at most eight or nine miles from the main expedition, and no doubt, after a day or so, they would send up after us if we did not return.

“After a day or so . . . ”

The lieutenant paused. “Ever been thirsty, Graham?”

“Not that kind,” said the Ethnologist.

“H’m. We had the whole of that day, the night, and the next day of it, and only a trifle of dew we wrung out of our clothes and the tent. And below us was the river going giggle, giggle, round a rock in mid stream. I never knew such a barrenness of incident, or such a quantity of sensation. The sun might have had Joshua’s command still upon it for all the motion one could see; and it blazed like a near furnace. Towards the evening of the first day one of the Derbyshire men said something — nobody heard what — and went off round the bend of the cliff. We heard shots, and when Hooker looked round the corner he was gone. And in the morning the Sepoy whose leg was shot was in delirium, and jumped or fell over the cliff. Then we took the mule and shot it, and that must needs go over the cliff too in its last struggles, leaving eight of us.

“We could see the body of the Sepoy down below, with the head in the water. He was lying face downwards, and so far as I could make out was scarcely smashed at all. Badly as the Chins might covet his head, they had the sense to leave it alone until the darkness came.

“At first we talked of all the chances there were of the main body hearing the firing, and reckoned whether they would begin to miss us, and all that kind of thing, but we dried up as the evening came on. The Sepoys played games with bits of stone among themselves, and afterwards told stories. The night was rather chilly. The second day nobody spoke. Our lips were black and our throats afire, and we lay about on the ledge and glared at one another. Perhaps it’s as well we kept our thoughts to ourselves. One of the British soldiers began writing some blasphemous rot on the rock with a bit of pipeclay, about his last dying will, until I stopped it. As I looked over the edge down into the valley and saw the river rippling I was nearly tempted to go after the Sepoy. It seemed a pleasant and desirable thing to go rushing down through the air with something to drink — or no more thirst at any rate — at the bottom. I remembered in time, though, that I was the officer in command, and my duty to set a good example, and that kept me from any such foolishness.

“Yet, thinking of that, put an idea into my head. I got up and looked at the tent and tent ropes, and wondered why I had not thought of it before. Then I came and peered over the cliff again. This time the height seemed greater and the pose of the Sepoy rather more painful. But it was that or nothing. And to cut it short, I parachuted.

“I got a big circle of canvas out of the tent, about three times the size of that table-cover, and plugged the hole in the centre, and I tied eight ropes round it to meet in the middle and make a parachute. The other chaps lay about and watched me as though they thought it was a new kind of delirium. Then I explained my notion to the two British soldiers and how I meant to do it, and as soon as the short dusk had darkened into night, I risked it. They held the thing high up, and I took a run the whole length of the ledge. The thing filled with air like a sail, but at the edge I will confess I funked and pulled up.

“As soon as I stopped I was ashamed of myself — as well I might be in front of privates — and went back and started again. Off I jumped this time — with a kind of sob, I remember — clean into the air, with the big white sail bellying out above me.

“I must have thought at a frightful pace. It seemed a long time before I was sure that the thing meant to keep steady. At first it heeled sideways. Then I noticed the face of the rock which seemed to be streaming up past me, and me motionless. Then I looked down and saw in the darkness the river and the dead Sepoy rushing up towards me. But in the indistinct light I also saw three Chins, seemingly aghast at the sight of me, and that the Sepoy was decapitated. At that I wanted to go back again.

“Then my boot was in the mouth of one, and in a moment he and I were in a heap with the canvas fluttering down on the top of us. I fancy I dashed out his brains with my foot. I expected nothing more than to be brained myself by the other two, but the poor heathen had never heard of Baldwin, and incontinently bolted.

“I struggled out of the tangle of dead Chin and canvas, and looked round. About ten paces off lay the head of the Sepoy staring in the moonlight. Then I saw the water and went and drank. There wasn’t a sound in the world but the footsteps of the departing Chins, a faint shout from above, and the gluck of the water. So soon as I had drunk my full I started off down the river.

“That about ends the explanation of the flying man story. I never met a soul the whole eight miles of the way. I got to Walters’ camp by ten o’clock, and a born idiot of a sentinel had the cheek to fire at me as I came trotting out of the darkness. So soon as I had hammered my story into Winter’s thick skull, about fifty men started up the valley to clear the Chins out and get our men down. But for my own part I had too good a thirst to provoke it by going with them.

“You have heard what kind of a yarn the Chins made of it. Wings as long as a mule, eh? — And black feathers! The gay lieutenant bird! Well, well.”

The lieutenant meditated cheerfully for a moment. Then he added, “You would scarcely credit it, but when they got to the ridge at last, they found two more of the Sepoys had jumped over.”

“The rest were all right?” asked the Ethnologist.

“Yes,” said the lieutenant; “the rest were all right, barring a certain thirst, you know.”

And at the memory he helped himself to soda and whisky again.

Herbert George Wells

(1866-1946)

The Stolen Bacillus and other incidents

short stories

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, Archive W-X, H.G. Wells, Tales of Mystery & Imagination, Wells, H.G.

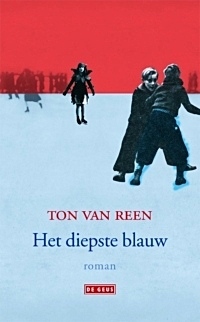

Mels is ziek van eenzaamheid. Tijger en Thija hebben diepe gaten in zijn hoofd achtergelaten. En grootvader Bernhard kan hem niet troosten, al vertelt hij nog zulke mooie verhalen. Zijn hoofd wil geen verhalen meer horen. Zelfs zijn moeder kan hem niet troosten, terwijl ze heel goed begrijpt wat er in hem omgaat.

Maar zijn vader vindt hem een mietje omdat hij zo lang verdriet heeft over een meisje.

Maar zijn vader vindt hem een mietje omdat hij zo lang verdriet heeft over een meisje.

`Het land zit vol meisjes’, zegt zijn vader. `En stuk voor stuk zijn ze mooier dan dat spichtige ding. Je wordt nog honderd keer verliefd.’ Hij kan zijn vader wel vermoorden.

Lusteloos zit hij in de boot en kijkt in het dode, zwarte water van de Wijer. Hij snapt niet dat ze hier vroeger zulke vette, blinkende vissen hebben gevangen. Zilveren forellen met roze buiken. Het is nu al meer dan een week geleden dat Thija vertrokken is en nog steeds heeft ze geen brief gestuurd.

Met moeite roeit hij naar de brug, maar de boot is veel zwaarder dan vroeger en loopt steeds aan de grond. Elke keer als hij, tot aan de knieën in het water, de boot vlot moet duwen, zou hij het liefst gillend naar het andere eind van de wereld rennen. Wat heb je aan een boot als je er helemaal alleen in zit en niet weet waar je naartoe wilt varen?

Eindelijk is hij bij de brug. Lizet van het café hangt over de reling. Hij ziet haar pas als hij de boot vastlegt en op de wal wil springen.

`Wíj hebben een echte boot’, zegt Lizet.

`Krijg de pest met je boot’, wil hij roepen, maar hij doet het niet.

`Mijn vader heeft een motorboot gekocht. Zondag gaan we varen. Je mag mee als je wilt.’

`Als ik niks te doen heb’, zegt Mels, maar hij weet nu al dat hij niet mee wil.

`Er is nooit wat te doen op zondag’, zegt Lizet.

Mels weet dat ze gelijk heeft. Dat heeft hij afgelopen zondag voor het eerst gemerkt. Toen was Thija pas één dag weg. Toen Tijger er nog was, gingen ze met z’n drieën roeien, schaatsen, of eekhoorns vangen. Op zondagen reisden ze naar China op de woorden van Thija. De zondagen waren veel te kort. Maar aan de eerste zondag waarop hij alleen was, kwam geen einde.

Hij wordt al ziek als hij denkt aan de komende zondag.

`Verdomme!’ Hij schreeuwt het uit.

`Praat je vaak in jezelf?’ vraagt Lizet.

`Hoezo?’

`Je vloekt tegen jezelf.’

`Die rotboot. Het is meer duwen dan varen.’

`Ga toch mee, zondag. Dan zie je pas een echte boot. Met een kajuit.’

`Goed, ik ga mee.’ Hij zegt het omdat hij bang is voor de komende zondag. Hij kan niet tegen een zwarte zondag, waarop alle bomen zwart zijn en het riet zwart is en hij niet eens bij zijn grootvader Bernhard kan zijn omdat alles in zijn huis zwart, morsdood en leeg is.

`We vertrekken om acht uur, met de auto.’

`Niet met de boot?’

`Je denkt toch niet dat we met een motorboot op de Wijer gaan varen. Zo’n roestbeek. We hebben de boot op de Maas liggen.’

Mels heeft al spijt van zijn belofte.

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (101)

wordt vervolgd

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

Le Voyage

Oh! sable

Si fin,

Qu’accable

Matin

Mon pas,

J’espère

Là-bas,

Repaire

Du jour,

Mourir!

Et le sable lui dit, en paraissant s’ouvrir:

Marche! Marche toujours!

Marcel Schwob

(1867-1905)

Le Voyage

Portrait: Félix Vallotton

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Archive S-T, Félix Vallotton, Marcel Schwob

De Dichter

Geen zomer-schaâuwe is schoon als ‘t beeld, in volle teilen,

der welv’ge melk die ront, van roerig licht ommaald.

Mijn schamel huis, waar zoel een geur van peren draalt,

weegt teerder in mijn schroom dan ‘t hele herfst-verwijlen.

En, waar van ‘t winter-dak een schone mane daalt,

‘n weifelt ijl een hele lente in hare wijle,

o mijn gezóende blik, en moe van eigen-peilen?

– Geen zoen is goed, dan die vergeten zorg verhaalt…

Aldus wie zijn geluk in ‘t noden van een teken

gelijk een geurig brood meewarig-blij durft breken,

en nut de zuurste zemel-korst in heil’ge waan;

om bij het heil dat weende en ‘t vreemde leed dat lachte,

en in de hoede van uw deemstren, o Gedachte,

eens, als een schone vraag, glim-lachend heen te gaan.

De Boom-Gaard der Vogelen en der Vruchten (1903 – 1905)

Karel van de Woestijne

(1878 – 1929)

De Dichter

Portret van Karel van de Woestijne (1937) door Henri van Straten (1892 – 1944)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive W-X, Archive W-X, Woestijne, Karel van de

Farewell!

If Ever Fondest Prayer

Farewell! if ever fondest prayer

For other’s weal availed on high,

Mine will not all be lost in air,

But waft thy name beyond the sky.

‘Twere vain to speak, to weep, to sigh:

Oh! more than tears of blood can tell,

When wrung from guilt’s expiring eye,

Are in that word – Farewell! – Farewell!

These lips are mute, these eyes are dry;

But in my breast and in my brain,

Awake the pangs that pass not by,

The thought that ne’er shall sleep again.

My soul nor deigns nor dares complain,

Though grief and passion there rebel;

I only know we loved in vain –

I only feel – Farewell! – Farewell!

George Gordon Byron

(1788 – 1824)

Farewell! If Ever Fondest Prayer

(Poem)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Byron, Lord

The Fugitive

Fool, fool,

They can hear thy frighted feet,

And they poke fun at thee,

Or pity thee,

Or pity thee.

They can hear thy steps retreat,

Shuffling timidly.

Thy gait is hobbling and uncouth,

For stubborn is earth’s clay;

There was a day,

There was a day,

When from the doom of its own youth,

Thy spirit stole away.

Do they not know thy spirit’s home?

Thy spirit, glancing, glides

Beneath all tides,

Beneath all tides.

It is a coral under foam;

In the cool deep it hides.

For lo, the yielding element

Of immortality

Is like the sea,

Is like the sea.

Do they not hear, in wonderment,

The tides enfolding thee?

Gladys Cromwell

(1885-1919)

The Fugitive

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Cromwell, Gladys, Gladys Cromwell

Wel honderd keer is hij naar Rotterdam gereisd, op zoek naar Thija. Een paar keer per jaar. Hij heeft zich nooit los kunnen maken van de Wijer en de boottochtjes met Tijger en Thija. Die herinneringen zijn z’n intiemste bezit. Als een schatbewaarder is hij bij de Wijer blijven wonen.

In Rotterdam heeft hij geen spoor van haar gevonden. Zijn hele leven is hij op zoek geweest naar een schim. Natuurlijk was ze anders geworden. Natuurlijk was ze net zo oud als hij en moest hij haar niet zoeken tussen de kinderen die op straat speelden, maar tussen de vrouwen in de winkels, in de trams, in de restaurants, in de opiumkitten. Bij alle vrouwen keek hij naar de knieën, op zoek naar het roze mondje op de rechterknie, maar hij vond het nooit terug. Vaak had hij er zich belachelijk door gemaakt.

In Rotterdam heeft hij geen spoor van haar gevonden. Zijn hele leven is hij op zoek geweest naar een schim. Natuurlijk was ze anders geworden. Natuurlijk was ze net zo oud als hij en moest hij haar niet zoeken tussen de kinderen die op straat speelden, maar tussen de vrouwen in de winkels, in de trams, in de restaurants, in de opiumkitten. Bij alle vrouwen keek hij naar de knieën, op zoek naar het roze mondje op de rechterknie, maar hij vond het nooit terug. Vaak had hij er zich belachelijk door gemaakt.

En haar vader? Hij had er vaak over gesproken met de heer Wong Lun Hing, die een hotelletje had waar hij altijd had overnacht. De heer Wong had overal navraag gedaan in de Chinese gemeenschap, maar geen spoor gevonden van een Lacoste die getrouwd was met een Chinese. De enige Lacoste die ze hadden kunnen ontdekken was een Fransman geweest, die een theeplantage had gehad in China en die, al wat ouder, toen hij zijn plantage aan de communisten had verloren, in Rotterdam was gaan wonen en een handel in thee had opgezet. Een thee-imperium dat handelde over de hele wereld. Hij woonde in Rotterdam en had een zoon. Navraag bij hem had niets opgeleverd.

Tot Wong Lun Hing op zekere dag had geopperd dat die heren van de thee er in hun goede tijden in China meestal bijzitten op na hielden. Buitenvrouwen. Had Lacoste zo’n buitenvrouw laten overkomen en haar ver weg van Rotterdam in een huis gezet waar hij haar af en toe bezocht?

Op eigen houtje was Mels achter Lacoste aangegaan, maar op het adres dat Wong Lun Hing had achterhaald, woonde iemand anders, iemand die alleen maar wist dat hij het huis had gekocht van een makelaar, die het te koop had aangeboden omdat de vorige eigenaar was gestorven, waarna zijn weduwe met onbekende bestemming was vertrokken.

Een dood spoor, maar wel een spoor dat veel onrust in hem had gewekt.

In een paar kranten had hij een oproep geplaatst aan Thija Lacoste, ondertekend met Mels Gommans. Nooit had hij er iets op gehoord.

Door al zijn zoektochten had hij de stad Rotterdam leren kennen. De havens, die jaar na jaar veranderden. De straten die nooit hetzelfde waren. De mensen van wie hij zich nooit een gezicht herinnerde, maar wel het rumoer dat ze maakten. De hoerenbuurt. Chinese meisjes bij de vleet. Matrozenhoeren die spaarden voor een eigen zaak, een eigen bordeel.

Telkens was hij teleurgesteld teruggekomen uit Rotterdam. Thuis was zijn eerste gang steeds naar de Wijer, waar de boot lag te verrotten in het riet. Na jaren restte er niet meer van dan het rondhout van de boeg. Hij nam het mee naar huis en bewaarde het op zolder. De laatste tastbare herinnering aan Tijger en Thija.

Sinds hij in de rolstoel zit, is hij niet meer in Rotterdam geweest.

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (100)

wordt vervolgd

•fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

A brilliant second collection by Sally Wen Mao on the violence of the spectacle ― starring the film legend Anna May Wong

In Oculus, Sally Wen Mao explores exile not just as a matter of distance and displacement but as a migration through time and a reckoning with technology. The title poem follows a nineteen-year-old girl in Shanghai who uploaded her suicide onto Instagram.

In Oculus, Sally Wen Mao explores exile not just as a matter of distance and displacement but as a migration through time and a reckoning with technology. The title poem follows a nineteen-year-old girl in Shanghai who uploaded her suicide onto Instagram.

Other poems cross into animated worlds, examine robot culture, and haunt a necropolis for electronic waste. A fascinating sequence spanning the collection speaks in the voice of the international icon and first Chinese American movie star Anna May Wong, who travels through the history of cinema with a time machine, even past her death and into the future of film, where she finds she has no progeny.

With a speculative imagination and a sharpened wit, Mao powerfully confronts the paradoxes of seeing and being seen, the intimacies made possible and ruined by the screen, and the many roles and representations that women of color are made to endure in order to survive a culture that seeks to consume them.

I will blow a hole

in the airwaves, duck lasers in my dugout.

I’m done kidding them. Today I fly

the hell out in my Chrono-Jet.

To the future, where I’m forgotten.

(from “Anna May Wong Fans Her Time Machine”)

“The poems in Oculus are rangy, protean, contradictory. They offer an alternative to the selfie, that static reduction of a person to her most photogenic poses.”— The New Yorker

Sally Wen Mao is the author of a previous poetry collection, Mad Honey Symposium. Her work has won a Pushcart Prize and fellowships at Kundiman, George Washington University, and the New York Public Library Cullman Center.

Oculus: Poems

by Sally Wen Mao (Author)

Paperback

96 pages

January 15, 2019

Publisher: Graywolf Press

Language: English

Subject: Poetry

ISBN-10: 1555978258

ISBN-13: 978-1555978259

Product Dimensions: 6.9 x 0.4 x 9.1 inches

$16.00

# more poetry

Sally Wen Mao

Oculus

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Archive M-N, Archive M-N, Art & Literature News

De Vlaamse televisiemaker, muzikant en schrijver Jan Leyers (1958) is de winnaar van de E. du Perronprijs 2018.

De jury honoreert zijn boek Allah in Europa: reisverslag van een ongelovige. Volgens de jury een: ‘fascinerend boek waarin een veelheid aan ideeën en opinies aan de orde komt, waaraan de lezer zijn of haar eigen mening kan scherpen’.

De jury honoreert zijn boek Allah in Europa: reisverslag van een ongelovige. Volgens de jury een: ‘fascinerend boek waarin een veelheid aan ideeën en opinies aan de orde komt, waaraan de lezer zijn of haar eigen mening kan scherpen’.

De andere genomineerden voor de prijs waren Ilja Leonard Pfeijffer met Grand Hotel Europa en Jolande Withuis Raadselvader.

Leyers krijgt 2500 euro voor de E. du Perronprijs, een initiatief van de gemeente Tilburg, de Tilburg School of Humanities & Digital Sciences van de Tilburgse universiteit en de organisatie Kunstloc Brabant.

E. du Perronprijs 2018 voor het boek Allah in Europa: reisverslag van een ongelovige van Jan Leyers

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Book Stories, Archive K-L, Art & Literature News, Awards & Prizes, MONTAIGNE, PRESS & PUBLISHING, WAR & PEACE

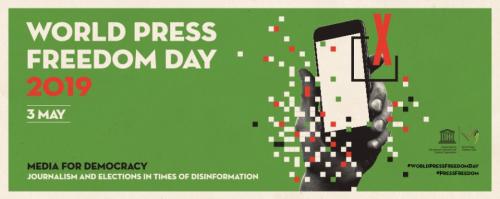

Every year, 3 May is a date which celebrates the fundamental principles of press freedom, to evaluate press freedom around the world, to defend the media from attacks on their independence and to pay tribute to journalists who have lost their lives in the exercise of their profession.

World Press Freedom Day was proclaimed by the UN General Assembly in 1993 following a Recommendation adopted at the twenty-sixth session of UNESCO‘s General Conference in 1991. This in turn was a response to a call by African journalists who in 1991 produced the landmark Windhoek Declaration (link is external) on media pluralism and independence.

At the core of UNESCO’s mandate is freedom of the press and freedom of expression. UNESCO believes that these freedoms allow for mutual understanding to build a sustainable peace.

It serves as an occasion to inform citizens of violations of press freedom – a reminder that in dozens of countries around the world, publications are censored, fined, suspended and closed down, while journalists, editors and publishers are harassed, attacked, detained and even murdered.

It is a date to encourage and develop initiatives in favour of press freedom, and to assess the state of press freedom worldwide.

3 May acts as a reminder to governments of the need to respect their commitment to press freedom and is also a day of reflection among media professionals about issues of press freedom and professional ethics. Just as importantly, World Press Freedom Day is a day of support for media which are targets for the restraint, or abolition, of press freedom. It is also a day of remembrance for those journalists who lost their lives in the pursuit of a story.

WORLD PRESS FREEDOM DAY

May 3, 2019

# more information website unesco

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Stories, Art & Literature News, AUDIO, CINEMA, RADIO & TV, LITERARY MAGAZINES, Photography, PRESS & PUBLISHING, REPRESSION OF WRITERS, JOURNALISTS & ARTISTS

Alle bomen in het woud

Wolfgrijs zwaar als naamloze nachten

versteende wachtwoorden. Alles begint

en eindigt met verhalen. Over verborgen

offers bijvoorbeeld. Of de vraag: ‘Ben je

als je droomt iedereen?’ Ken je dan van

de wind het geheim? Waait het dan stil?

Alle bomen in het woud is ons land.

Bert Bevers

Alle bomen in het woud

Verschenen in de catalogus Enghuizer Dialogen 2015, Hummelo, 2015

Bert Bevers is a poet and writer who lives and works in Antwerp (Be)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Bevers, Bert

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature