Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Het Russische absurdisme laat zich gemakkelijk terugbrengen tot één man: Daniil Charms. “Charms is kunst,’ schreef een vriend over hem.

Met zijn opvallende verschijning, zijn excentriciteit, zijn creatieve tegendraadsheid was hij een fenomeen en groeide hij na zijn dood uit tot een wereldwijd bekende cultschrijver. “Mij interesseert alleen “onzin”,’ schreef hij ooit, “alleen dat wat geen enkele praktische zin heeft.’

Met zijn opvallende verschijning, zijn excentriciteit, zijn creatieve tegendraadsheid was hij een fenomeen en groeide hij na zijn dood uit tot een wereldwijd bekende cultschrijver. “Mij interesseert alleen “onzin”,’ schreef hij ooit, “alleen dat wat geen enkele praktische zin heeft.’

Charms blinkt uit in het tonen van de onsamenhangendheid van het bestaan en de onvoorspelbaarheid van het lot. Hij zoekt naar een ongefilterde verbeelding van de chaos die wij voortbrengen, los van zingeving en in de hoop op nieuwe ervaringen en aha-erlebnissen. In zijn werk laat hij willekeur vergezeld gaan van een stevige dosis, vaak zwartgallige, humor.

Voor het eerst verschijnt een grote uitgave van Charms’ werk in de Russische Bibliotheek, samengesteld uit proza, toneelteksten, gedichten, autobiografisch proza en kinderverhalen, en rijkelijk aangevuld met avantgardistische illustraties.

Auteur: Daniil Charms

Verzameld werk

Vertaald door Yolanda Bloemen

Russische Bibliotheek (RB)

Uitgeverij van Oorschot

Verschijningsdatum januari 2018

Taal Nederlands

1e druk

Bindwijze: Hardcover

Afmetingen 20,3 x 12,8 x 3,4 cm

736 pagina’s

ISBN 9789028282353

€ 44,99

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: *Concrete + Visual Poetry A-E, - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive C-D, Archive C-D, Art & Literature News, Expressionism, Kharms (Charms), Daniil, Psychiatric hospitals

I Speak Not

I speak not, I trace not, I breathe not thy name;

There is grief in the sound, there is guilt in the fame;

But the tear that now burns on my cheek may impart

The deep thoughts that dwell in that silence of heart.

Too brief for our passion, too long for our peace,

Were those hours – can their joy or their bitterness cease?

We repent, we abjure, we will break from our chain, –

We will part, we will fly to – unite it again!

Oh! thine be the gladness, and mine be the guilt!

Forgive me, adored one! – forsake if thou wilt;

But the heart which is thine shall expire undebased,

And man shall not break it – whatever thou may’st.

And stern to the haughty, but humble to thee,

This soul in its bitterest blackness shall be;

And our days seem as swift, and our moments more sweet,

With thee at my side, than with worlds at our feet.

One sigh of thy sorrow, one look of thy love,

Shall turn me or fix, shall reward or reprove.

And the heartless may wonder at all I resign –

Thy lips shall reply, not to them, but to mine.

George Gordon Byron

(1788 – 1824)

I Speak Not

(Poem)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Byron, Lord

10 décembre 1919: le prix Goncourt est attribué à Marcel Proust pour À l’ombre des jeunes filles en fleurs.

Aussitôt éclate un tonnerre de protestations : anciens combattants, pacifistes, réactionnaires, révolutionnaires, chacun se sent insulté par un livre qui, ressuscitant le temps perdu, semble dédaigner le temps présent.

Aussitôt éclate un tonnerre de protestations : anciens combattants, pacifistes, réactionnaires, révolutionnaires, chacun se sent insulté par un livre qui, ressuscitant le temps perdu, semble dédaigner le temps présent.

Pendant des semaines, Proust est vilipendé dans la presse, brocardé, injurié, menacé. Son tort? Ne plus être jeune, être riche, ne pas avoir fait la guerre, ne pas raconter la vie dans les tranchées.

Retraçant l’histoire du prix et les manœuvres en vue de son attribution à Proust, s’appuyant sur des documents inédits, dont il dévoile nombre d’extraits savoureux, Thierry Laget fait le récit d’un événement inouï – cette partie de chamboule-tout qui a déplacé le pôle magnétique de la littérature – et de l’émeute dont il a donné le signal.

Retraçant l’histoire du prix et les manœuvres en vue de son attribution à Proust, s’appuyant sur des documents inédits, dont il dévoile nombre d’extraits savoureux, Thierry Laget fait le récit d’un événement inouï – cette partie de chamboule-tout qui a déplacé le pôle magnétique de la littérature – et de l’émeute dont il a donné le signal.

Thierry Laget

Proust, prix Goncourt. Une émeute littéraire

Collection Blanche, Gallimard

Parution : 04-04-2019

272 pages

140 x 205 mm

ISBN : 9782072846786

Genre : Essais

Prix €19,50

# new books

Thierry Laget

Proust

prix Goncourt

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Archive K-L, Archive O-P, Archive O-P, Art & Literature News, Awards & Prizes, Marcel Proust, Proust, Marcel

This year, the Poetry International Festival Rotterdam turns 50!

The milestone makes it the oldest festival in the city, and one of the oldest in the country, with a wealth of history and highlights. Nobel Prize-winning poets once stood on Poetry’s stages as bright young talents, and the festival is both a shining example for, and founding parent of, poetry festivals worldwide.

Poetry International celebrates its golden anniversary with an extra festive edition at Concertgebouw De Doelen, which also hosted the debut festival back in 1970. Trailblazing poets will deliver transformative work thrumming with the now.

Unique fusions of poetry by engaging artists from the worlds of music, cinema, and dance amplify the power, the beauty, and the personal impact of poetry, here in the form of an intimate reading or workshop, there as a multidisciplinary theatrical poetry spectacle. Right in the heart of the city, inviting, challenging, unmissable.

What Happened to the Future? Since 1970, poetry luminaries from all over the world travel to Rotterdam for the annual Poetry International Festival. Thousands of poets have shared their work on the stages of De Doelen and the Schouwburg, but also in the city’s squares, parks, and trams. A landmark anniversary like this is an invitation to look back and celebrate the past, but at the same time, Poetry International will be looking ahead. Under the title What Happened to the Future?, the 50th Poetry International Festival unites its rich history with the world’s poems and poets of today and tomorrow.

The Metropole Orchestra – nominated for 18 Grammy Awards – will open the 50th Poetry International Festival with a literal bang. In this theatrical kick-off, the orchestra will perform unique duets with poets, including the legendary Last Poets, godfathers of hip hop and spoken word. Inspired by the festival’s theme, “What Happened to the Future?”, poets from the festival’s rich past, such as Judith Herzberg, Antjie Krog, Rita Dove, Raúl Zurita, and Tom Lanoye, will perform side by side with poets of a more recent vintage, such as Marieke Lucas Rijneveld, Koleka Putuma, Patricia Lockwood, Lieke Marsman, Frank Báez, Sayaka Osaki, Ulrike Almut Sandig, and Galina Rymboe. Whether rooted in the past or inspired by the future, their readings will festively raise the curtains on this golden-anniversary edition.

From festival hub De Doelen, Poetry International will take you on a poetic walking tour through the heart of Rotterdam. Led by a guide from UrbanGuides, you will discover extraordinary art in public spaces and have surprising encounters with festival poets and spoken-word artists. Explore the city’s hidden stories together!

Practical festival information

Following the Opening Night on 13 June the 50th Poetry International Festival will presents three days packed with readings, concerts, workshops, specials, poetic city walks, interviews, award ceremonies and book presentations. Check the changing starting times beforehand! Almost all programs take place or depart from De Doelen, in the heart of the city within a 5-minute walk of Rotterdam Central Station.

The 50th Poetry International Festival will kick-off on 13 June in the Main Auditorium of de Doelen. On 14, 15 and 16 June most events will take place in or around the Jurriaanse zaal. De Doelen is situated within walking distance of Rotterdam Central Station

# More information on website Poetry International Festival

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #Archive A-Z Sound Poetry, #More Poetry Archives, - Book News, Art & Literature News, AUDIO, CINEMA, RADIO & TV, LITERARY MAGAZINES, Marieke Lucas Rijneveld, MODERN POETRY, Poetry International, STREET POETRY, Tom Lanoye

Voor de bouwvakkers zit de werkdag erop. Ze lopen terug naar de auto en vertrekken. Mels rolt naar de silo om het resultaat beter te bekijken. De steigers staan al een paar meter boven de grond.

De deur van de voormalige directiekamer staat open. Hij kan er zo binnenrijden. De meubels van de laatste directeuren staan er nog. Alles is gebleven zoals het was. Niemand heeft ooit de moeite genomen hier iets weg te halen. Alles is verrot en vervuild. Het heeft voor niemand waarde meer. Het ziet ernaaruit dat de arbeiders het allemaal in een container voor grof vuil zullen gooien.

De deur van de voormalige directiekamer staat open. Hij kan er zo binnenrijden. De meubels van de laatste directeuren staan er nog. Alles is gebleven zoals het was. Niemand heeft ooit de moeite genomen hier iets weg te halen. Alles is verrot en vervuild. Het heeft voor niemand waarde meer. Het ziet ernaaruit dat de arbeiders het allemaal in een container voor grof vuil zullen gooien.

Het gepolitoerde bureau van Frans-Joseph zit onder het vuil. De kast, met de monsters van de meelproducten die ze maakten, staat er nog. De affiches aan de muur, huisvrouwen die glunderend hun pakken meel vasthouden. De foto’s van de stichters van de fabriek, de weduwe Hubben-Houba zo breed als de molenaar zelf, aan haar rokken zoon Frits, die later de molen zou overnemen, en Tom, de zoon die naar Amerika zou verdwijnen. En de dochters die naar het klooster werden gestuurd, zodat ze geen beroep konden doen op de erfenis, en zo geruisloos uit de geschiedenis van de familie en van de fabriek werden weggesluisd.

De grote foto van Frits Hubben, de erfgenaam die het bedrijf liet verhuizen van de watermolen naar de fabriek, zittend aan een bureau. Naast hem de twee zonen, Frans-Hubert en Frans-Joseph, beiden al met een blik in de ogen die verraadt dat het hen allemaal geen bal interesseert.

De foto’s van de laatste generatie. De kinderen van Frans-Hubert en van Frans-Joseph, van wie niemand nog in het bedrijf heeft gewerkt, vrolijk lachend bijeen op een grasveld voor een villa.

Hij vindt het jammer dat hij niet eerder wist dat dit hier allemaal hing te vergaan. Hij had het graag willen behouden. De foto’s had hij kunnen bewaren in zijn archief, maar nu zijn ze waardeloos. Vocht heeft ze aangetast en beschimmeld. Waterkringen lopen door het rottende papier. Deze rotzooi kan hij niet meer mee naar huis nemen, ook al zou hij het willen. Lizet wil het zeker niet in huis hebben.

In een laatje vindt hij stukken van het reclamearchief, waar Frits Hubben zo zorgvuldig mee omging. Foto’s van vrouwen die verlekkerd een beslag kloppen, met in hun hand een pak patentmeel van Hubben. Foto’s van de verpakkingen van Luxe- en Excellentmeel, die zo mooi zijn dat ze van meel een kostbaarheid maken. Een foto van een dikke man, glunderend met een pak anti-obstipatiemeel vol zemelen in de hand, het wondermeel waarvan hardlijvige mensen een gezonde stoelgang zouden krijgen. Foto’s in een bakkerij waar de balen Hubben Broodmeel hoog liggen opgeslagen, en de bakker en zijn knechten trots de glimmende broden met suikerkorst tonen. Winkels in levensmiddelen en koloniale waren met Hubbens bijzondere soorten brood- en bakmeel in de rekken. Hubbens broodmeel in Indonesië en Zuid-Afrika. Alle foto’s stralen glorie uit en demonstreren daardoor des te meer hoe onnodig de ondergang van de fabriek was.

In zijn woede grijpt hij een pot met een verdroogde bloem van de vensterbank en gooit hem naar het familieportret van de lapzwansen. Het glas rinkelt. Dat doet goed.

Dan pas ziet hij de bouwlift, aan de achterkant van de silo. Die moeten ze vandaag hebben geplaatst. In een opwelling rijdt hij ernaartoe en rolt het platform op van de lift. Hij drukt op de knop. Het ding werkt. Ze hebben vergeten de stroom uit te schakelen.

Langzaam gaat hij naar boven. Het is opwindend. Hij voelt zich een klein kind dat iets doet wat verboden is.

De lift staat stil. Hij is op het hoogste punt aangekomen. Nu weer naar beneden? Of het dak op? De vloerplaat kan uitgeschoven worden. Door een druk op een knop schuift de plaat tot op het dak en vormt een brug.

Hij rijdt het dak op. Hij kijkt rond en voelt zich vrij.

Op nog geen halve meter van de rand stopt hij de rolstoel. Tussen zijn voeten doorkijkend, in de diepte, ziet hij het dorp zoals een vogel het ziet. De rookpluimen boven de rode, blauwe en grauwe daken. Hij kan ze tellen. Nu hij er bovenop kijkt, ontdekt hij de regelmaat in het patroon. Broederlijk liggen de huizen dicht naast elkaar. Hun goten omarmen elkaar en verbinden meer dan honderd huizen. Aan elkaar gesloten pannenrijen, rood, blauw en grijs, versterken het beeld van een gesloten dorp.

Vanaf hier is zijn huis het zevende dak van rechts. Als je het dorp vanaf het noorden binnenkomt, is zijn huis het derde aan de rechterkant. Kom je vanuit het zuiden, dan is het ‘t tweeëntwintigste huis aan de linkerkant. Kom je van de weg langs de Wijer, dan is het vanaf de brug het zevende huis rechts, aan de overkant van de straat.

Zou je met een bootje over de Wijer het dorp binnenvaren tegen de stroom op, dan is het het negende huis links. Tegenover zijn huis ligt slagerij Kemp. Kemp levert bierworst aan café De Zwaan, dat aan de andere kant van de brug ligt, en fijne vleeswaren als er in De Zwaan een uitvaartmaal wordt geserveerd of als er een trouwpartij is.

Maar er komt niemand over de Wijer het dorp binnenvaren. Nu, laat in de middag, is de beek een zilveren streep tussen de weilanden, die soms heel even zwart wordt als er een wolk voor de zon trekt. Vanmiddag zijn er weinig wolken. De zon schijnt zo overdadig dat de miljoenen margrieten langs het riviertje een breed wit tapijt vormen. De oevers zijn net zo wit als vroeger, toen de weide wit was omdat zijn moeder er de lakens op te bleken had gelegd en hij haar moest helpen om stenen op de hoeken te leggen, zodat de wind ze niet kon meenemen.

Van bovenaf lijkt het dorp veel lieflijker dan het in werkelijkheid is. Het centrum van vroeger is maar klein. De huizen staan er dicht op elkaar, alsof ze bang zijn voor de uitgestrektheid van de velden, weilanden en bossen die het dorp omringen, maar vooral voor de groeiende buitenwijken.

Hoewel het dorp diep beneden hem ligt, lijkt alles waar hij naar kijkt toch heel dichtbij. De wand van de silo versterkt de geluiden van beneden, zodat hij alles hoort wat zich daar afspeelt. Er zijn maar een paar mensen op straat, maar doordat hij van zo hoog op hen neerkijkt, hebben ze hun proporties verloren: het zijn gedrongen poppetjes.

Nu hoeft hij alleen maar de rem van zijn rolstoel te ontkoppelen, de wind zal hem wel een zetje willen geven. Voor het eerst sinds lang zullen ze naar hem kijken, allemaal, daar in het dorp. Hij glimlacht bij de gedachte, juist omdat hij dat niet nodig heeft. Hij hoeft geen aandacht, hij wil alleen maar dat ze weten wie hij is.

Hij hoort hoe de mensen met elkaar praten. De daken kunnen wel het zicht op de mensen verbergen, maar nemen niet hun stemmen weg. Hij meent zelfs het ademen van de baby in de tuin van zijn dochter te horen. En het snorren van de poes, die als een bal opgerold aan het voeteneind in de kinderwagen ligt. Het is gevaarlijk. De kat mag niet op de baby gaan liggen, dat zou de dood van het kind kunnen betekenen.

Eigenlijk zou hij moeten schreeuwen, om de kat te verjagen. Maar het beest zal hem niet horen. Van beneden kan niemand hem horen. Hij heeft eens een man vanaf het dak van de silo naar beneden zien schreeuwen, de mond wijdopen, de handen als een toeter aan de mond, maar niemand hoorde hem.

Het is zelfs nog maar de vraag of ze hem van de straat af kunnen zien. Als ze naar boven zouden kijken, kijken ze tegen de onderkant van de rolstoel aan, de voetenplankjes. Ze zullen denken dat het ding iets is van de aannemer die de silo verbouwt.

Opeens hoort hij zoemen achter zijn rug. De lift. De vloerplaat wordt naar binnen gehaald. Dan zakt de lift naar beneden. Heeft iemand hem ontdekt? Halen ze hem nu van het dak?

Hij hoort veel stemmen tegelijk en doet moeite om het koor van geluiden te ontrafelen. Een voor een weet hij de stemmen in zijn oren te ontcijferen. De stem van Kemp, de slager, de stemmen van de samenwonende nichtjes Tinie en Tinie van de Bercken, die beiden al bijna honderd moeten zijn en theedrinken op het terras achter het huis waarmee ze samen in de tijd wegzakken. De postbode, die `post!’ roept bij elke brievenbus waar hij wat in gooit, ook bij een huis dat al jaren leegstaat en waarin de post zich in de gang tot een berg heeft opgehoopt.

Hij hoort niet alleen de stemmen van degenen die beneden zijn, er klinken ook fragmenten door van stemmen van langgeleden. De bewoners van het kerkhof. Grootvader Bernhard. Juffrouw Fijnhout. Ze zijn rumoerig en praten door elkaar heen, net of ze hem allemaal tegelijk iets willen zeggen. Of ze hem roepen. Eén stem is goed te verstaan omdat hij zacht en rustig is. Grootvader Bernhard. Fragmenten van zinnen. `Zonnebloemen zijn … zomerbui … lusten jullie een … heb ik al klaar’, waaruit Mels begrijpt dat regen goed was voor zonnebloemen en dat grootvader glazen limonade voor hen op het aanrecht heeft staan. Hoewel grootvader Bernhard steeds stukken van zinnen inslikt, begrijpt hij hem toch goed als hij zegt: `Niet doen … is heilig … niet de hand aan …’ Even ziet hij hem zitten, in zijn leunstoel, boven op de betonnen grafsteen, maar dan lost zijn beeld op in het zonlicht om weer op te duiken bij het molenhuis, op zijn stukje land bij de Wijer.

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (102)

wordt vervolgd

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

Metershoge spinnen, kolossale ogen en hangende spiralen in de monumentale vleugelnootboom.

Dit voorjaar presenteert het Rijksmuseum Louise Bourgeois in de Rijksmuseumtuinen. Het is voor het eerst dat een ruime selectie van Bourgeois’ buitenbeelden bijeen wordt gebracht.

Met twaalf beelden toont het Rijksmuseum een overzicht van een halve eeuw werk, van The Blind Leading the Blind (1947-49) tot Crouching Spider (2003). Veel van deze werken zijn nooit eerder in Nederland te zien geweest.

Louise Bourgeois (1911-2010) geniet internationale faam als een van de belangrijkste vrouwelijke kunstenaars van de twintigste eeuw en werd wereldberoemd met haar monumentale beelden van spinnen.

Louise Bourgeois in de Rijksmuseumtuinen

Tentoonstelling 24 mei – 3 november 2019

Van de hand van de samensteller van de tentoonstelling, Alfred Pacquement, verschijnt een catalogus: Louise Bourgeois in de Rijksmuseumtuinen in het Nederlands en Engels. Vanaf begin juni verkrijgbaar via rijksmuseumshop.nl. Prijs: €15,-

# meer informatie op website rijksmuseum

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Archive A-B, Art & Literature News, Exhibition Archive, Louise Bourgeois, Sculpture

THE SCAPEGOAT (II)

A year is not a long time. It was short enough to prevent people from forgetting Robinson, and yet long enough for their pity to grow strong as they remembered. Indeed, he was not gone a year. Good behaviour cut two months off the time of his sentence, and by the time people had come around to the notion that he was really the greatest and smartest man in Cadgers he was at home again.

He came back with no flourish of trumpets, but quietly, humbly. He went back again into the heart of the black district. His business had deteriorated during his absence, but he put new blood and new life into it. He did not go to work in the shop himself, but, taking down the shingle that had swung idly before his office door during his imprisonment, he opened the little room as a news- and cigar-stand.

He came back with no flourish of trumpets, but quietly, humbly. He went back again into the heart of the black district. His business had deteriorated during his absence, but he put new blood and new life into it. He did not go to work in the shop himself, but, taking down the shingle that had swung idly before his office door during his imprisonment, he opened the little room as a news- and cigar-stand.

Here anxious, pitying custom came to him and he prospered again. He was very quiet. Uptown hardly knew that he was again in Cadgers, and it knew nothing whatever of his doings.

“I wonder why Asbury is so quiet,” they said to one another. “It isn’t like him to be quiet.” And they felt vaguely uneasy about him.

So many people had begun to say, “Well, he was a mighty good fellow after all.”

Mr. Bingo expressed the opinion that Asbury was quiet because he was crushed, but others expressed doubt as to this. There are calms and calms, some after and some before the storm. Which was this?

They waited a while, and, as no storm came, concluded that this must be the after-quiet. Bingo, reassured, volunteered to go and seek confirmation of this conclusion.

He went, and Asbury received him with an indifferent, not to say, impolite, demeanour.

“Well, we’re glad to see you back, Asbury,” said Bingo patronisingly. He had variously demonstrated his inability to lead during his rival’s absence and was proud of it. “What are you going to do?”

“I’m going to work.”

“That’s right. I reckon you’ll stay out of politics.”

“What could I do even if I went in?”

“Nothing now, of course; but I didn’t know—-“

He did not see the gleam in Asbury’s half shut eyes. He only marked his humility, and he went back swelling with the news.

“Completely crushed–all the run taken out of him,” was his report.

The black district believed this, too, and a sullen, smouldering anger took possession of them. Here was a good man ruined. Some of the people whom he had helped in his former days–some of the rude, coarse people of the low quarter who were still sufficiently unenlightened to be grateful–talked among themselves and offered to get up a demonstration for him. But he denied them. No, he wanted nothing of the kind. It would only bring him into unfavourable notice. All he wanted was that they would always be his friends and would stick by him.

They would to the death.

There were again two factions in Cadgers. The school-master could not forget how once on a time he had been made a tool of by Mr. Bingo. So he revolted against his rule and set himself up as the leader of an opposing clique. The fight had been long and strong, but had ended with odds slightly in Bingo’s favour.

But Mr. Morton did not despair. As the first of January and Emancipation Day approached, he arrayed his hosts, and the fight for supremacy became fiercer than ever. The school-teacher is giving you a pretty hard brought the school-children in for chorus singing, secured an able orator, and the best essayist in town. With all this, he was formidable.

Mr. Bingo knew that he had the fight of his life on his hands, and he entered with fear as well as zest. He, too, found an orator, but he was not sure that he was as good as Morton’s. There was no doubt but that his essayist was not. He secured a band, but still he felt unsatisfied. He had hardly done enough, and for the school-master to beat him now meant his political destruction.

It was in this state of mind that he was surprised to receive a visit from Mr. Asbury.

“I reckon you’re surprised to see me here,” said Asbury, smiling.

“I am pleased, I know.” Bingo was astute.

“Well, I just dropped in on business.”

“To be sure, to be sure, Asbury. What can I do for you?”

“It’s more what I can do for you that I came to talk about,” was the reply.

“I don’t believe I understand you.”

“Well, it’s plain enough. They say that the school-teacher is giving you a pretty hard fight.”

“Oh, not so hard.”

“No man can be too sure of winning, though. Mr. Morton once did me a mean turn when he started the faction against me.”

Bingo’s heart gave a great leap, and then stopped for the fraction of a second.

“You were in it, of course,” pursued Asbury, “but I can look over your part in it in order to get even with the man who started it.”

It was true, then, thought Bingo gladly. He did not know. He wanted revenge for his wrongs and upon the wrong man. How well the schemer had covered his tracks! Asbury should have his revenge and Morton would be the sufferer.

“Of course, Asbury, you know what I did I did innocently.”

“Oh, yes, in politics we are all lambs and the wolves are only to be found in the other party. We’ll pass that, though. What I want to say is that I can help you to make your celebration an overwhelming success. I still have some influence down in my district.”

“Certainly, and very justly, too. Why, I should be delighted with your aid. I could give you a prominent place in the procession.”

“I don’t want it; I don’t want to appear in this at all. All I want is revenge. You can have all the credit, but let me down my enemy.”

Bingo was perfectly willing, and, with their heads close together, they had a long and close consultation. When Asbury was gone, Mr. Bingo lay back in his chair and laughed. “I’m a slick duck,” he said.

From that hour Mr. Bingo’s cause began to take on the appearance of something very like a boom. More bands were hired. The interior of the State was called upon and a more eloquent orator secured. The crowd hastened to array itself on the growing side.

With surprised eyes, the school-master beheld the wonder of it, but he kept to his own purpose with dogged insistence, even when he saw that he could not turn aside the overwhelming defeat that threatened him. But in spite of his obstinacy, his hours were dark and bitter. Asbury worked like a mole, all underground, but he was indefatigable. Two days before the celebration time everything was perfected for the biggest demonstration that Cadgers had ever known. All the next day and night he was busy among his allies.

On the morning of the great day, Mr. Bingo, wonderfully caparisoned, rode down to the hall where the parade was to form. He was early. No one had yet come. In an hour a score of men all told had collected. Another hour passed, and no more had come. Then there smote upon his ear the sound of music. They were coming at last. Bringing his sword to his shoulder, he rode forward to the middle of the street. Ah, there they were. But–but–could he believe his eyes? They were going in another direction, and at their head rode–Morton! He gnashed his teeth in fury. He had been led into a trap and betrayed. The procession passing had been his–all his. He heard them cheering, and then, oh! climax of infidelity, he saw his own orator go past in a carriage, bowing and smiling to the crowd.

There was no doubting who had done this thing. The hand of Asbury was apparent in it. He must have known the truth all along, thought Bingo. His allies left him one by one for the other hall, and he rode home in a humiliation deeper than he had ever known before.

Asbury did not appear at the celebration. He was at his little news-stand all day.

In a day or two the defeated aspirant had further cause to curse his false friend. He found that not only had the people defected from him, but that the thing had been so adroitly managed that he appeared to be in fault, and three-fourths of those who knew him were angry at some supposed grievance. His cup of bitterness was full when his partner, a quietly ambitious man, suggested that they dissolve their relations.

His ruin was complete.

The lawyer was not alone in seeing Asbury’s hand in his downfall. The party managers saw it too, and they met together to discuss the dangerous factor which, while it appeared to slumber, was so terribly awake. They decided that he must be appeased, and they visited him.

He was still busy at his news-stand. They talked to him adroitly, while he sorted papers and kept an impassive face. When they were all done, he looked up for a moment and replied, “You know, gentlemen, as an ex-convict I am not in politics.”

Some of them had the grace to flush.

“But you can use your influence,” they said.

“I am not in politics,” was his only reply.

And the spring elections were coming on. Well, they worked hard, and he showed no sign. He treated with neither one party nor the other. “Perhaps,” thought the managers, “he is out of politics,” and they grew more confident.

It was nearing eleven o’clock on the morning of election when a cloud no bigger than a man’s hand appeared upon the horizon. It came from the direction of the black district. It grew, and the managers of the party in power looked at it, fascinated by an ominous dread. Finally it began to rain Negro voters, and as one man they voted against their former candidates. Their organisation was perfect. They simply came, voted, and left, but they overwhelmed everything. Not one of the party that had damned Robinson Asbury was left in power save old Judge Davis. His majority was overwhelming.

The generalship that had engineered the thing was perfect. There were loud threats against the newsdealer. But no one bothered him except a reporter. The reporter called to see just how it was done. He found Asbury very busy sorting papers. To the newspaper man’s questions he had only this reply, “I am not in politics, sir.”

But Cadgers had learned its lesson.

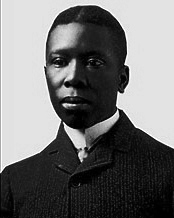

Paul Laurence Dunbar

(1872 – 1906)

The Scapegoat (II)

Short story

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Archive C-D, Dunbar, Paul Laurence, Dunbar, Paul Laurence, Paul Laurence Dunbar, Paul Laurence Dunbar

THE SCAPEGOAT (I)

The law is usually supposed to be a stern mistress, not to be lightly wooed, and yielding only to the most ardent pursuit. But even law, like love, sits more easily on some natures than on others.

This was the case with Mr. Robinson Asbury. Mr. Asbury had started life as a bootblack in the growing town of Cadgers. From this he had risen one step and become porter and messenger in a barber-shop. This rise fired his ambition, and he was not content until he had learned to use the shears and the razor and had a chair of his own. From this, in a man of Robinson’s temperament, it was only a step to a shop of his own, and he placed it where it would do the most good.

This was the case with Mr. Robinson Asbury. Mr. Asbury had started life as a bootblack in the growing town of Cadgers. From this he had risen one step and become porter and messenger in a barber-shop. This rise fired his ambition, and he was not content until he had learned to use the shears and the razor and had a chair of his own. From this, in a man of Robinson’s temperament, it was only a step to a shop of his own, and he placed it where it would do the most good.

Fully one-half of the population of Cadgers was composed of Negroes, and with their usual tendency to colonise, a tendency encouraged, and in fact compelled, by circumstances, they had gathered into one part of the town. Here in alleys, and streets as dirty and hardly wider, they thronged like ants.

It was in this place that Mr. Asbury set up his shop, and he won the hearts of his prospective customers by putting up the significant sign, “Equal Rights Barber-Shop.” This legend was quite unnecessary, because there was only one race about, to patronise the place. But it was a delicate sop to the people’s vanity, and it served its purpose.

Asbury came to be known as a clever fellow, and his business grew. The shop really became a sort of club, and, on Saturday nights especially, was the gathering-place of the men of the whole Negro quarter. He kept the illustrated and race journals there, and those who cared neither to talk nor listen to someone else might see pictured the doings of high society in very short skirts or read in the Negro papers how Miss Boston had entertained Miss Blueford to tea on such and such an afternoon. Also, he kept the policy returns, which was wise, if not moral.

It was his wisdom rather more than his morality that made the party managers after a while cast their glances toward him as a man who might be useful to their interests. It would be well to have a man–a shrewd, powerful man–down in that part of the town who could carry his people’s vote in his vest pocket, and who at any time its delivery might be needed, could hand it over without hesitation. Asbury seemed that man, and they settled upon him. They gave him money, and they gave him power and patronage. He took it all silently and he carried out his bargain faithfully. His hands and his lips alike closed tightly when there was anything within them. It was not long before he found himself the big Negro of the district and, of necessity, of the town. The time came when, at a critical moment, the managers saw that they had not reckoned without their host in choosing this barber of the black district as the leader of his people.

Now, so much success must have satisfied any other man. But in many ways Mr. Asbury was unique. For a long time he himself had done very little shaving–except of notes, to keep his hand in. His time had been otherwise employed. In the evening hours he had been wooing the coquettish Dame Law, and, wonderful to say, she had yielded easily to his advances.

It was against the advice of his friends that he asked for admission to the bar. They felt that he could do more good in the place where he was.

“You see, Robinson,” said old Judge Davis, “it’s just like this: If you’re not admitted, it’ll hurt you with the people; if you are admitted, you’ll move uptown to an office and get out of touch with them.”

Asbury smiled an inscrutable smile. Then he whispered something into the judge’s ear that made the old man wrinkle from his neck up with appreciative smiles.

“Asbury,” he said, “you are–you are–well, you ought to be white, that’s all. When we find a black man like you we send him to State’s prison. If you were white, you’d go to the Senate.”

The Negro laughed confidently.

He was admitted to the bar soon after, whether by merit or by connivance is not to be told.

“Now he will move uptown,” said the black community. “Well, that’s the way with a coloured man when he gets a start.”

But they did not know Asbury Robinson yet. He was a man of surprises, and they were destined to disappointment. He did not move uptown. He built an office in a small open space next his shop, and there hung out his shingle.

“I will never desert the people who have done so much to elevate me,” said Mr. Asbury.

“I will live among them and I will die among them.”

This was a strong card for the barber-lawyer. The people seized upon the statement as expressing a nobility of an altogether unique brand.

They held a mass meeting and indorsed him. They made resolutions that extolled him, and the Negro band came around and serenaded him, playing various things in varied time.

All this was very sweet to Mr. Asbury, and the party managers chuckled with satisfaction and said, “That Asbury, that Asbury!”

Now there is a fable extant of a man who tried to please everybody, and his failure is a matter of record. Robinson Asbury was not more successful. But be it said that his ill success was due to no fault or shortcoming of his.

For a long time his growing power had been looked upon with disfavour by the coloured law firm of Bingo & Latchett. Both Mr. Bingo and Mr. Latchett themselves aspired to be Negro leaders in Cadgers, and they were delivering Emancipation Day orations and riding at the head of processions when Mr. Asbury was blacking boots. Is it any wonder, then, that they viewed with alarm his sudden rise? They kept their counsel, however, and treated with him, for it was best. They allowed him his scope without open revolt until the day upon which he hung out his shingle. This was the last straw. They could stand no more. Asbury had stolen their other chances from them, and now he was poaching upon the last of their preserves. So Mr. Bingo and Mr. Latchett put their heads together to plan the downfall of their common enemy.

The plot was deep and embraced the formation of an opposing faction made up of the best Negroes of the town. It would have looked too much like what it was for the gentlemen to show themselves in the matter, and so they took into their confidence Mr. Isaac Morton, the principal of the coloured school, and it was under his ostensible leadership that the new faction finally came into being.

Mr. Morton was really an innocent young man, and he had ideals which should never have been exposed to the air. When the wily confederates came to him with their plan he believed that his worth had been recognised, and at last he was to be what Nature destined him for–a leader.

The better class of Negroes–by that is meant those who were particularly envious of Asbury’s success–flocked to the new man’s standard. But whether the race be white or black, political virtue is always in a minority, so Asbury could afford to smile at the force arrayed against him.

The new faction met together and resolved. They resolved, among other things, that Mr. Asbury was an enemy to his race and a menace to civilisation. They decided that he should be abolished; but, as they couldn’t get out an injunction against him, and as he had the whole undignified but still voting black belt behind him, he went serenely on his way.

“They’re after you hot and heavy, Asbury,” said one of his friends to him.

“Oh, yes,” was the reply, “they’re after me, but after a while I’ll get so far away that they’ll be running in front.”

“It’s all the best people, they say.”

“Yes. Well, it’s good to be one of the best people, but your vote only counts one just the same.”

The time came, however, when Mr. Asbury’s theory was put to the test. The Cadgerites celebrated the first of January as Emancipation Day. On this day there was a large procession, with speechmaking in the afternoon and fireworks at night. It was the custom to concede the leadership of the coloured people of the town to the man who managed to lead the procession. For two years past this honour had fallen, of course, to Robinson Asbury, and there had been no disposition on the part of anybody to try conclusions with him.

Mr. Morton’s faction changed all this. When Asbury went to work to solicit contributions for the celebration, he suddenly became aware that he had a fight upon his hands. All the better-class Negroes were staying out of it. The next thing he knew was that plans were on foot for a rival demonstration.

“Oh,” he said to himself, “that’s it, is it? Well, if they want a fight they can have it.”

He had a talk with the party managers, and he had another with Judge Davis.

“All I want is a little lift, judge,” he said, “and I’ll make ’em think the sky has turned loose and is vomiting niggers.”

The judge believed that he could do it. So did the party managers. Asbury got his lift. Emancipation Day came.

There were two parades. At least, there was one parade and the shadow of another. Asbury’s, however, was not the shadow. There was a great deal of substance about it–substance made up of many people, many banners, and numerous bands. He did not have the best people. Indeed, among his cohorts there were a good many of the pronounced rag-tag and bobtail. But he had noise and numbers. In such cases, nothing more is needed. The success of Asbury’s side of the affair did everything to confirm his friends in their good opinion of him.

When he found himself defeated, Mr. Silas Bingo saw that it would be policy to placate his rival’s just anger against him. He called upon him at his office the day after the celebration.

“Well, Asbury,” he said, “you beat us, didn’t you?”

“It wasn’t a question of beating,” said the other calmly. “It was only an inquiry as to who were the people–the few or the many.”

“Well, it was well done, and you’ve shown that you are a manager. I confess that I haven’t always thought that you were doing the wisest thing in living down here and catering to this class of people when you might, with your ability, to be much more to the better class.”

“What do they base their claims of being better on?”

“Oh, there ain’t any use discussing that. We can’t get along without you, we see that. So I, for one, have decided to work with you for harmony.”

“Harmony. Yes, that’s what we want.”

“If I can do anything to help you at any time, why you have only to command me.”

“I am glad to find such a friend in you. Be sure, if I ever need you, Bingo, I’ll call on you.”

“And I’ll be ready to serve you.”

Asbury smiled when his visitor was gone. He smiled, and knitted his brow. “I wonder what Bingo’s got up his sleeve,” he said. “He’ll bear watching.”

It may have been pride at his triumph, it may have been gratitude at his helpers, but Asbury went into the ensuing campaign with reckless enthusiasm. He did the most daring things for the party’s sake. Bingo, true to his promise, was ever at his side ready to serve him. Finally, association and immunity made danger less fearsome; the rival no longer appeared a menace.

With the generosity born of obstacles overcome, Asbury determined to forgive Bingo and give him a chance. He let him in on a deal, and from that time they worked amicably together until the election came and passed.

It was a close election and many things had had to be done, but there were men there ready and waiting to do them. They were successful, and then the first cry of the defeated party was, as usual, “Fraud! Fraud!” The cry was taken up by the jealous, the disgruntled, and the virtuous.

Someone remembered how two years ago the registration books had been stolen. It was known upon good authority that money had been freely used. Men held up their hands in horror at the suggestion that the Negro vote had been juggled with, as if that were a new thing. From their pulpits ministers denounced the machine and bade their hearers rise and throw off the yoke of a corrupt municipal government. One of those sudden fevers of reform had taken possession of the town and threatened to destroy the successful party.

They began to look around them. They must purify themselves. They must give the people some tangible evidence of their own yearnings after purity. They looked around them for a sacrifice to lay upon the altar of municipal reform. Their eyes fell upon Mr. Bingo. No, he was not big enough. His blood was too scant to wash away the political stains. Then they looked into each other’s eyes and turned their gaze away to let it fall upon Mr. Asbury. They really hated to do it. But there must be a scapegoat. The god from the Machine commanded them to slay him.

Robinson Asbury was charged with many crimes–with all that he had committed and some that he had not. When Mr. Bingo saw what was afoot he threw himself heart and soul into the work of his old rival’s enemies. He was of incalculable use to them.

Judge Davis refused to have anything to do with the matter. But in spite of his disapproval it went on. Asbury was indicted and tried. The evidence was all against him, and no one gave more damaging testimony than his friend, Mr. Bingo. The judge’s charge was favourable to the defendant, but the current of popular opinion could not be entirely stemmed. The jury brought in a verdict of guilty.

“Before I am sentenced, judge, I have a statement to make to the court. It will take less than ten minutes.”

“Go on, Robinson,” said the judge kindly.

Asbury started, in a monotonous tone, a recital that brought the prosecuting attorney to his feet in a minute. The judge waved him down, and sat transfixed by a sort of fascinated horror as the convicted man went on. The before-mentioned attorney drew a knife and started for the prisoner’s dock. With difficulty he was restrained. A dozen faces in the court-room were red and pale by turns.

“He ought to be killed,” whispered Mr. Bingo audibly.

Robinson Asbury looked at him and smiled, and then he told a few things of him. He gave the ins and outs of some of the misdemeanours of which he stood accused. He showed who were the men behind the throne. And still, pale and transfixed, Judge Davis waited for his own sentence.

Never were ten minutes so well taken up. It was a tale of rottenness and corruption in high places told simply and with the stamp of truth upon it.

He did not mention the judge’s name. But he had torn the mask from the face of every other man who had been concerned in his downfall. They had shorn him of his strength, but they had forgotten that he was yet able to bring the roof and pillars tumbling about their heads.

The judge’s voice shook as he pronounced sentence upon his old ally–a year in State’s prison.

Some people said it was too light, but the judge knew what it was to wait for the sentence of doom, and he was grateful and sympathetic.

When the sheriff led Asbury away the judge hastened to have a short talk with him.

“I’m sorry, Robinson,” he said, “and I want to tell you that you were no more guilty than the rest of us. But why did you spare me?”

“Because I knew you were my friend,” answered the convict.

“I tried to be, but you were the first man that I’ve ever known since I’ve been in politics who ever gave me any decent return for friendship.”

“I reckon you’re about right, judge.”

In politics, party reform usually lies in making a scapegoat of someone who is only as criminal as the rest, but a little weaker. Asbury’s friends and enemies had succeeded in making him bear the burden of all the party’s crimes, but their reform was hardly a success, and their protestations of a change of heart were received with doubt. Already there were those who began to pity the victim and to say that he had been hardly dealt with.

Mr. Bingo was not of these; but he found, strange to say, that his opposition to the idea went but a little way, and that even with Asbury out of his path he was a smaller man than he was before. Fate was strong against him. His poor, prosperous humanity could not enter the lists against a martyr. Robinson Asbury was now a martyr.

Paul Laurence Dunbar

(1872 – 1906)

The Scapegoat (I)

Short story

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Archive C-D, Dunbar, Paul Laurence, Dunbar, Paul Laurence, Paul Laurence Dunbar, Paul Laurence Dunbar

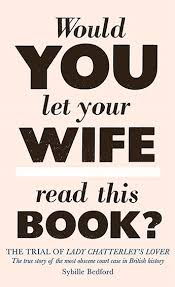

English PEN have launched a crowdfunding campaign to ensure that a hand-annotated copy of Lady Chatterley’s Lover used by the judge in its landmark obscenity trial can remain in the UK

During the trial, the presiding judge, the Hon. Sir Laurence Byrne, referred to a copy of the book which had been annotated by his wife. She had made notes of character names in the margins, underlined important sections, and had produced a list of page numbers relating to significant passages in the book (“love making”, “coarse”, etc).

Because of its unique crucial importance in British history, the arts minister, Michael Ellis, has determined that it should remain in the UK and has placed a temporary bar preventing its overseas export from being exported overseas if a UK-based bidder can match its price. English PEN have launched the GoFundMe campaign to raise the money required to keep the book in the UK.

Because of its unique crucial importance in British history, the arts minister, Michael Ellis, has determined that it should remain in the UK and has placed a temporary bar preventing its overseas export from being exported overseas if a UK-based bidder can match its price. English PEN have launched the GoFundMe campaign to raise the money required to keep the book in the UK.

Philippe Sands QC, President of English PEN, said:

DH Lawrence was an active member of English PEN and unique in the annals of English literary history. Lady Chatterley’s Lover was at the heart of the struggle for freedom of expression, in the courts and beyond. This rare copy of the book, used and marked up by the judge, must remain in the UK, accessible to the British public to help understand what is lost without freedom of expression. This unique text belongs here, a symbol of the continuing struggle to protect the rights of writers and readers at home and abroad.

Lady Chatterley’s Lover was published in Europe in 1928, but remained unpublished in the UK for thirty years following DH Lawrence’s death in 1930. Its narrative – of an aristocratic woman embarking on a passionate relationship with a groundskeeper outside of her sexless marriage – challenged establishment sensibilities, and publishers were unwilling to publish it through fear of prosecution.

The 1960 obscenity trial of Lady Chatterley’s Lover was one of the most important cases in British literary and social history, and led to a significant shift in the cultural landscape. The trial highlighted the distance between modern society and an out-of-touch establishment, shown in the opening remarks of Mervyn Griffith-Jones, the lead prosecutor:

The 1960 obscenity trial of Lady Chatterley’s Lover was one of the most important cases in British literary and social history, and led to a significant shift in the cultural landscape. The trial highlighted the distance between modern society and an out-of-touch establishment, shown in the opening remarks of Mervyn Griffith-Jones, the lead prosecutor:

Would you approve of your young sons, young daughters – because girls can read as well as boys – reading this book?

Is it a book that you would have lying around in your own house? Is it a book that you would even wish your wife or your servants to read?

However, it took the jury just three hours to reach a decision that the novel was not obscene, and, within a day, the book sold 200,000 copies, rising to more than 2 million copies in the next two years.

The verdict was a crucial step in ushering the permissive and liberal sixties and was an enormously important victory for freedom of expression.

We want to ensure this piece of our cultural history remains in the UK. Please support us and help spread the word.

# Support the campaign see website ENGLISH PEN

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Stories, Archive K-L, D.H. Lawrence, Erotic literature, Lawrence, D.H., PRESS & PUBLISHING, REPRESSION OF WRITERS, JOURNALISTS & ARTISTS

Saudi Arabia has long been considered one of the most restrictive countries in the world for human rights, and particularly for women.

The fleeting hope that generational transition in the Saudi leadership would open the door toward greater respect for individual rights and international law has collapsed entirely, with individuals paying the highest price as the government resorts to rank barbarism as a blunt means to suppress and deter dissent.

Through their writing and activism, Nouf Abdulaziz, Loujain Al-Hathloul, and Eman Al-Nafjan have challenged the Saudi government, demanding human rights, even in the face of intimidation and brutality.

These three courageous women—who are being honored this month with the 2019 PEN/Barbey Freedom to Write Award—have challenged one of the world’s most notoriously misogynist governments, inspiring the world with their demand to drive, to govern their own lives, and to liberate all Saudi women from a form of repression that has no place in the 21st century.

Sign the petition to call on the Saudi Arabian government to drop all charges against these courageous writer-activists and ensure that they and others have the right to speak and advocate freely and without fear of repercussions.

Nouf Abdulaziz, Loujain Al-Hathloul, Eman Al-Nafjan

To the Saudi Arabian government:

We are distressed to observe the continuation of systematic rights abuses in Saudi Arabia, and the brutal crackdown against critical voices whose peaceful efforts are aimed at encouraging their government to uphold the most basic standards of human rights and international law. We call on your government to drop all charges against Nouf Abdulaziz, Loujain Al-Hathloul, and Eman Al-Nafjan, and their fellow activists and ensure that they and others have the right to speak and advocate freely and without fear of repercussions.

# Take action – See website PEN America

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Art & Literature News, AUDIO, CINEMA, RADIO & TV, PRESS & PUBLISHING, REPRESSION OF WRITERS, JOURNALISTS & ARTISTS

For the first time in a quarter century, a major new volume of translations of the beloved poetry of Federico García Lorca, presented in a beautiful bilingual edition

The fluid and mesmeric lines of these new translations by the award-winning poet Sarah Arvio bring us closer than ever to the talismanic perfection of the great García Lorca. Poet in Spain invokes the “wild, innate, local surrealism” of the Spanish voice, in moonlit poems of love and death set among poplars, rivers, low hills, and high sierras.

The fluid and mesmeric lines of these new translations by the award-winning poet Sarah Arvio bring us closer than ever to the talismanic perfection of the great García Lorca. Poet in Spain invokes the “wild, innate, local surrealism” of the Spanish voice, in moonlit poems of love and death set among poplars, rivers, low hills, and high sierras.

Arvio’s ample and rhythmically rich offering includes, among other essential works, the folkloric yet modernist Gypsy Ballads, the plaintive flamenco Poem of the Cante Jondo, and the turbulent and beautiful Dark Love Sonnets—addressed to Lorca’s homosexual lover—which Lorca was revising at the time of his brutal political murder by Fascist forces in the early days of the Spanish Civil War.

Here, too, are several lyrics translated into English for the first time and the play Blood Wedding—also a great tragic poem. Arvio has created a fresh voice for Lorca in English, full of urgency, pathos, and lyricism—showing the poet’s work has grown only more beautiful with the passage of time.

Federico García Lorca may be Spain’s most famous poet and dramatist of all time. Born in Andalusia in 1898, he grew up in a village on the Vega and in the city of Granada. His prolific works, known for their powerful lyricism and an obsession with love and death, include the Gypsy Ballads, which brought him far-reaching fame, and the homoerotic Dark Love Sonnets, which did not see print until almost fifty years after his death. His murder in 1936 by Fascist forces at the outset of the Spanish Civil War became a literary cause célébre; in Spain, his writings were banned. Lorca’s poems and plays are now read and revered in many languages throughout the world.

Sarah Arvio is the author of night thoughts:70 dream poems & notes from an analysis, Sono: Cantos, and Visits from the Seventh: Poems. Winner of the Rome Prize and the Bogliasco and Guggenheim fellowships, among other honors, Arvio works as a translator for the United Nations in New York and Switzerland and has taught poetry at Princeton University.

Poet in Spain

By Federico Garcia Lorca

Translated by Sarah Arvio

Hardcover

576 Pages

Published by Knopf

2017

ISBN 9781524733117

Category: Poetry

$35.00

# More poetry

Federico Garcia Lorca

Poet in Spain

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Archive K-L, Archive K-L, Art & Literature News, Garcia Lorca, Federico, REPRESSION OF WRITERS, JOURNALISTS & ARTISTS, WAR & PEACE

From blogger Heather B. Armstrong (dooce), author of It Sucked and Then I Cried, comes The Valedictorian of Being Dead (Gallery), an irreverent new memoir – reminiscent of Brain on Fire – about her experience as one of only a few people to participate in an experimental treatment for depression involving 10 rounds of a chemically-induced coma approximating brain death.

For years, Heather Armstrong has alluded to her struggle with depression on her website, dooce. It’s scattered throughout her archive, where it weaves its way through posts about pop culture, music, and motherhood. But in 2016, Heather found herself in the depths of a depression she just couldn’t shake, an episode darker and longer than anything she had previously experienced. She had never felt so discouraged by the thought of waking up in the morning, and it threatened to destroy her life. So, for the sake of herself and her family, Heather decided to risk it all by participating in an experimental clinical trial involving a chemically induced coma approximating brain death.

For years, Heather Armstrong has alluded to her struggle with depression on her website, dooce. It’s scattered throughout her archive, where it weaves its way through posts about pop culture, music, and motherhood. But in 2016, Heather found herself in the depths of a depression she just couldn’t shake, an episode darker and longer than anything she had previously experienced. She had never felt so discouraged by the thought of waking up in the morning, and it threatened to destroy her life. So, for the sake of herself and her family, Heather decided to risk it all by participating in an experimental clinical trial involving a chemically induced coma approximating brain death.

Now, for the first time, Heather recalls the torturous eighteen months of suicidal depression she endured and the month-long experimental study in which doctors used propofol anesthesia to quiet all brain activity for a full fifteen minutes before bringing her back from a flatline. Ten times. The experience wasn’t easy. Not for Heather or her family. But a switch was flipped, and Heather hasn’t experienced a single moment of suicidal depression since.

Disarmingly honest, self-deprecating, and scientifically fascinating, The Valedictorian of Being Dead brings to light a groundbreaking new treatment for depression.

Author: Heather B. Armstrong

The Valedictorian of Being Dead:

The True Story of Dying Ten Times to Live

Binding: Hardcover

Publication date: 04/23/2019

Publisher: SIMON & SCHUSTER TRADE

Pages: 272

ISBN13: 9781501197048

ISBN10: 1501197045

List Price $26.00

# new books

Heather B. Armstrong

The Valedictorian of Being Dead

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Archive A-B, DRUGS & DISEASE & MEDICINE & LITERATURE, MONTAIGNE, NONFICTION: ESSAYS & STORIES

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature