Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

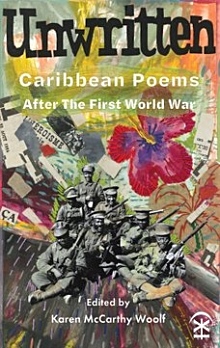

What does it mean to fight for a ‘mother country’ that refuses to accept you as one of its own?

Britain’s First World War poets changed the way we view military conflict and had a deep impact on the national psyche. Yet the stories of the 15,600 volunteers who signed up to the British West Indian Regiment remain largely unknown. Sadly, these citizens of empire were not embraced as compatriots on an equal footing. Instead they faced prejudice, injustice and discrimination while being confined to menial and auxiliary work, regardless of rank or status.

Britain’s First World War poets changed the way we view military conflict and had a deep impact on the national psyche. Yet the stories of the 15,600 volunteers who signed up to the British West Indian Regiment remain largely unknown. Sadly, these citizens of empire were not embraced as compatriots on an equal footing. Instead they faced prejudice, injustice and discrimination while being confined to menial and auxiliary work, regardless of rank or status.

As a collaborative project, co-commissioned by 14-18 NOW, BBC Contains Strong Language and the British Council, Unwritten Poems invited contemporary Caribbean and Caribbean diaspora poets to write into that vexed space, and explore the nature of war and humanity – as it exists now, and at a time when Britain’s colonial ambitions were still at a peak. Unwritten: Caribbean Poems After the First World War is a result of that provocation and also includes new material written for broadcast and live performance.

Unwritten:

Caribbean Poems After the First World War

by Karen McCarthy Woolf (Author, Editor)

With contributions from Jay Bernard, Malika Booker, Kat Francois, Jay T. John, Anthony Joseph, Ishion Hutchinson, Charnell Lucien, Vladimir Lucien, Rachel Manley, Tanya Shirley and Karen McCarthy Woolf.

Paperback

Publisher: Nine Arches Press

4 Oct. 2018

Poetry

Language: English

ISBN-10: 1911027298

ISBN-13: 978-1911027294

Product Dimensions: 16.3 x 1 x 23 cm

160 pages

Price: £14.99

# new book

Caribbean Poems After the First World War

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #Editors Choice Archiv, #More Poetry Archives, - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive W-X, Art & Literature News

Hij heeft geen idee waar Jacob begraven is. Toen heeft hij er niet naar gevraagd.

Hebben ze met z’n drieën nooit bloemen willen brengen naar zijn graf? Hij weet het niet meer. Er was te veel afstand tussen de zigeuners en de dorpelingen. Ze werden gedoogd, daar hield het mee op. Je ging er niet mee om. Dat wilden ze zelf waarschijnlijk ook niet. Ze bleven onder elkaar.

Hij rijdt door naar huis. Het is bijna twaalf uur.

Met moeite kan hij bij de bel.

Lizet doet open.

Lizet doet open.

`Dat werd tijd. Ik zit op je te wachten.’

`Het is nog geen twaalf uur.’

`Ik wil de boel aan kant hebben. Hoe was het?’

`Geen mens. Jij niet. Niemand.’

Over die hoerenmadam praat hij niet.

Hij rijdt door naar de keuken. De tafel is gedekt. In een hoek staat de kinderwagen. De baby van zijn dochter slaapt. De kat ligt in het mandje onder in de wagen.

Lizet legt een beboterde snee brood op zijn bord en doet er een omelet op.

Hij neemt een hap. Het ei is koud. Hij schuift het bord terug.

`Is het niet goed?’

`Het smaakt niet als het koud is.’

Buiten slaat de torenklok twaalf uur. Hij rolt zijn stoel terug.

`Eet je niet?’

`Nee.’

`Doe ik daar al die moeite voor?’

`Vanochtend gooide je mijn koffie weg. Nu is het ei koud.’

`Je was beter af in dat revalidatiecentrum’, gooit ze eruit.

`Ik ben blij dat je het gezegd hebt.’

`Zo bedoel ik het niet.’

`Je krijgt je zin.’

`Dram niet zo door.’

`Ik geef je gelijk.’

Ze weet dat ze te ver is gegaan. Nu heeft hij haar in de tang, ook al is het maar voor een paar tellen.

Met de lift gaat hij naar boven. Hij kijkt niet naar de schilderijen van de Wijer bij de trap. Hij wil niets zien.

Als hij van buiten komt, ziet hij elke keer hoe klein zijn kamer is. Ze lijkt steeds kleiner te worden. Een cel. Hij wil hier weg.

Hij kijkt niet in de spiegel. Hij wil zijn kwade hoofd niet zien.

Zijn bed is niet opgemaakt. Hij sluit zijn ogen en houdt de handen voor zijn oren, om de woede in hem te bedaren. Hij moet rustig worden. Aanvallen van woede kunnen het tekort aan bloed in zijn hoofd verergeren, zodat hij een aanval van verwardheid kan krijgen. Hij wil het niet. Hij moet overeind blijven. Als hij een aanval krijgt, laat ze hem in zijn vet gaar koken. Dan komt ze niet eens naar zijn kamer om hem te verzorgen.

Ze heeft hem al eens een hele nacht in zijn rolstoel laten zitten, voor straf. Hij was zo duizelig dat hij niet bij machte was om zelf in bed te komen. Toen hij naar het toilet ging, was hij naast de pot gevallen. Pas toen had ze hem geholpen. De vernedering had meer pijn gedaan dan de blauwe plekken.

Toch moet hij eventjes gaan liggen. Plat liggen is het best voor de bloedtoevoer naar zijn hoofd. Hij glijdt vanuit de rolstoel op bed en valt achterover. Het is gelukt. Hij rukt de plaid uit de rolstoel en trekt die over zijn hoofd. Donker verzacht zijn woede.

In huis is het stil. Zijn woorden hebben pijn gedaan, daar is hij zeker van. Hij heeft het niet gewild, maar hij heeft het ook niet kunnen voorkomen.

Hoe moet hij hier weg? Nergens zitten ze te wachten op een man die thuis nog een vrouw en dochter heeft die hem kunnen verzorgen. Maar de grens is bereikt.

Kan hij zijn manuscripten meenemen? Al die mappen? Het zijn stofnesten. Daar hebben ze de pest aan in zo’n verpleeghuis.

Hij zal het dorp missen. En de kleine rivier. De kleuren en de geuren van de Wijer.

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (084)

wordt vervolgd

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

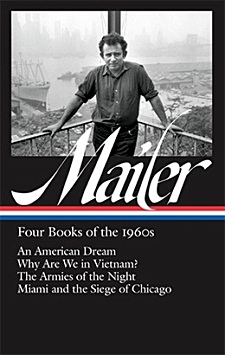

No writer plunged more vigorously into the chaotic energies of the 1960s than Norman Mailer, fearlessly revolutionizing literary norms and genres to capture the decade’s political, social, and sexual explosions.

Declaring himself to have “the mind of an outlaw,” he adhered closely to his own vision of what it meant to be a writer.

Declaring himself to have “the mind of an outlaw,” he adhered closely to his own vision of what it meant to be a writer.

In a way uniquely his own, he merged the public and the private, the personal and the political, taking risks with every sentence. Here, for the first time in a single volume, are four of his most extraordinary works.

War hero, television star, existential hipster, seducer, murderer: such is Stephen Rojack, the hero of An American Dream (1965), Mailer’s hallucinatory voyage through the dark night of an America awash in money, sex, and violence.

Mailer challenged himself by serializing the book while he was still writing it, an approach he compared to “ten-second chess.” The result is a fever dream of a novel, navigating through the most extreme fears and fantasies of a culture hooked on power.

In Why Are We in Vietnam? (1967) a motor-mouthed eighteen-year-old Texan on the eve of military service recounts an exclusive grizzly bear hunt in Alaska with an obscene exuberance that finally comes close to horror. Although the word “Vietnam” appears only on the book’s final page, the whole work is imbued with a sense of frantic bloodthirstiness that exposes the macho roots of the war.

With the acclaimed “non-fiction novel” The Armies of the Night (1968), an account of the October 1967 anti-Vietnam War march on the Pentagon, Mailer brought a new approach to journalism, casting himself (“he would have been admirable, except that he was an absolute egomaniac, a Beast”) as a player in the drama as he reported, alongside a stunning gallery of student activists, politicians, intellectuals, and policemen. Winning both the Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award, The Armies of the Night immediately established itself as an essential record of its moment.

In Miami and the Siege of Chicago (1968) Mailer continued his eyewitness chronicle of American political life, embedding himself at the 1968 Republican and Democratic presidential conventions and drawing unforgettable portraits of Richard Nixon, Nelson Rockefeller, Lyndon Johnson, Eugene McCarthy, and many others. His reading of the nation’s political undercurrents continues to surprise with its relevance.

J. Michael Lennon, editor, emeritus professor of English at Wilkes University, is Norman Mailer’s archivist, editor, and authorized biographer, and president of the Norman Mailer Society. His books include Norman Mailer: A Double Life (2013) and Selected Letters of Norman Mailer (2014).

This Library of America series edition is printed on acid-free paper and features Smyth-sewn binding, a full cloth cover, and a ribbon marker.

Norman Mailer: Four Books of the 1960s (LOA #305):

-An American Dream

-Why Are We in Vietnam?

-The Armies of the Night

-Miami and the Siege of Chicago

Hardcover

March 13, 2018

by Norman Mailer (Author)

J. Michael Lennon (Editor)

937 pages

ISBN: 978-1-59853-558-7

Library of America Series

N° 305

LOA books are distributed worldwide by Penguin Random House

List Price: $45.00

LIBRARY OF AMERICA is an independent nonprofit cultural organization founded in 1979 to preserve our nation’s literary heritage by publishing, and keeping permanently in print, America’s best and most significant writing. The Library of America series includes more than 300 volumes to date, authoritative editions that average 1,000 pages in length, feature cloth covers, sewn bindings, and ribbon markers, and are printed on premium acid-free paper that will last for centuries.

# new books

Norman Mailer:

Four Books of the 1960s (LOA #305):

-An American Dream

-Why Are We in Vietnam?

-The Armies of the Night

-Miami and the Siege of Chicago

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, - Book Stories, Archive M-N, Art & Literature News, Norman Mailer, WAR & PEACE

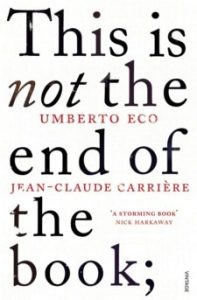

The perfect gift for book lovers: a beautifully designed hardcover in which two of the world’s great men have a delightfully rambling conversation about the future of the book in the digital era, and decide it is here to stay.

‘The book is like the spoon: once invented, it cannot be bettered.’ Umberto Eco These days it is almost impossible to get away from discussions of whether the ‘book’ will survive the digital revolution.

Blogs, tweets and newspaper articles on the subject appear daily, many of them repetitive, most of them admitting they don’t know what will happen. Amidst the twittering, the thoughts of Jean-Claude Carrière and Umberto Eco come as a breath of fresh air. There are few people better placed to discuss the past, present and future of the book. Both avid book collectors with a deep understanding of history, they have explored through their work the many and varied ways ideas have been represented through the ages.

Blogs, tweets and newspaper articles on the subject appear daily, many of them repetitive, most of them admitting they don’t know what will happen. Amidst the twittering, the thoughts of Jean-Claude Carrière and Umberto Eco come as a breath of fresh air. There are few people better placed to discuss the past, present and future of the book. Both avid book collectors with a deep understanding of history, they have explored through their work the many and varied ways ideas have been represented through the ages.

This thought-provoking book takes the form of a long conversation in which Carrière and Eco discuss everything from what can be defined as the first book to what is happening to knowledge now that infinite amounts of information are available at the click of a mouse. En route there are delightful digressions into personal anecdote. We find out about Eco’s first computer and the book Carrière is most sad to have sold.

Readers will close this entertaining book feeling they have had the privilege of eavesdropping on an intimate discussion between two great minds. And while, as Carrière says, the one certain thing about the future is that it is unpredictable, it is clear from this conversation that, in some form or other, the book will survive.

Umberto Eco (1932–2016) wrote fiction, literary criticism and philosophy. His first novel, The Name of the Rose, was a major international bestseller. His other works include Foucault’s Pendulum, The Island of the Day Before, Baudolino, The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana, The Prague Cemetery and Numero Zero along with many brilliant collections of essays.

Jean-Claude Carrière is a writer, playwright and screenwriter. He is notably the co-author of Conversations About the End of Time (with Stephen Jay Gould, Umberto Eco, etc.) He has also worked with Peter Brook, Milos Forman, Buñuel, Godard and the Dalaï Lama.

This is Not the End of the Book

A conversation curated by Jean-Philippe de Tonnac

By Umberto Eco, Jean-Claude Carrière

Language & Literary Studies

Paperback

ISBN 9780099552451

2012

Vintage Publ.

352 pages

$24.99

# new books

This is Not the End of the Book

Umberto Eco & Jean-Claude Carrière

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, - Book News, - Book Stories, - Bookstores, Archive C-D, Archive E-F, Art & Literature News, The Art of Reading, Umberto Eco

Oliver Sacks (1933 – 2015), befaamd neuroloog, wetenschapper en arts. Sacks studeerde medicijnen in Oxford, woonde sinds 1965 in New York en werkte als hoogleraar aan de NYU School of Medicine.

Oliver Sacks verwierf internationale roem met zijn populairwetenschappelijke boeken over de belevingswereld van zijn patiënten. Hij is de auteur van internationale bestsellers als Migraine, Ontwaken in verbijstering, De man die zijn vrouw voor een hoed hield, Stemmen zien, Een antropoloog op Mars, Musicofilia en Hallucinaties. In 2015 verscheen zijn autobiografie Onderweg. In augustus 2015 overleed hij in zijn woonplaats New York.

Oliver Sacks verwierf internationale roem met zijn populairwetenschappelijke boeken over de belevingswereld van zijn patiënten. Hij is de auteur van internationale bestsellers als Migraine, Ontwaken in verbijstering, De man die zijn vrouw voor een hoed hield, Stemmen zien, Een antropoloog op Mars, Musicofilia en Hallucinaties. In 2015 verscheen zijn autobiografie Onderweg. In augustus 2015 overleed hij in zijn woonplaats New York.

“Ik heb van mensen gehouden en zij hebben van mij gehouden, ik heb veel gekregen en ik heb iets teruggegeven, ik heb gelezen, gereisd, nagedacht en geschreven. Ik heb in contact gestaan met de wereld en de bijzondere uitwisselingen ervaren tussen een schrijver en zijn lezers. Maar in de eerste plaats ben ik op deze prachtige planeet een bewust denkend wezen geweest, een denkend dier, en dat alleen al was een enorm voorrecht en avontuur.”

In februari 2015 maakte Oliver Sacks, in een aangrijpend stuk in The New York Times, bekend dat hij ongeneeslijk ziek was. Eind augustus overleed hij in New York, 82 jaar oud. Sinds het bericht van zijn ziekte werkte hij met grote gedrevenheid verder aan de boeken die hij nog wilde afmaken. Intussen publiceerde hij een reeks essays waarin hij probeerde grip te krijgen op het verloop van zijn ziekte en de betekenis van zijn naderende dood.

In Dankbaarheid zijn deze stukken bijeengebracht. Het is een boek dat getuigt van een grote veerkracht en menselijkheid: het laat zien hoe iemand die geconfronteerd wordt met het naderende einde toch het leven kan vieren en dankbaar kan zijn.

Auteur: Oliver Sacks

Titel: Dankbaarheid

Taal: Nederlands

Hardcover

2015

1e druk

80 pagina’s

ISBN13 9789023497912

Uitgever De Bezige Bij

Vertaald door Luud Dorresteijn

€ 12,99

# new books

Oliver Sacks

Dankbaarheid. Essays

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Book Stories, Archive S-T, AUDIO, CINEMA, RADIO & TV, Oliver Sacks, Psychiatric hospitals

In this book, Gerald Janecek provides a comprehensive account of Moscow Conceptualist poetry and performance, arguably the most important development in the arts of the late Soviet period and yet one underappreciated in the West.

Such innovative poets as Vsevolod Nekrasov, Lev Rubinstein, and Dmitry Prigov are among the most prominent literary figures of Russia in the 1980s and 1990s, yet they are virtually unknown outside Russia. The same is true of the numerous active Russian performance art groups, especially the pioneering Collective Actions group, led by the brilliantly inventive Andrey Monastyrsky.

Such innovative poets as Vsevolod Nekrasov, Lev Rubinstein, and Dmitry Prigov are among the most prominent literary figures of Russia in the 1980s and 1990s, yet they are virtually unknown outside Russia. The same is true of the numerous active Russian performance art groups, especially the pioneering Collective Actions group, led by the brilliantly inventive Andrey Monastyrsky.

Everything Has Already Been Written strives to make Moscow Conceptualism more accessible, to break the language barrier and to foster understanding among an international readership by thoroughly discussing a broad range of specific works and theories.

Janecek’s study is the first comprehensive analysis of Moscow Conceptualist poetry and theory, vital for an understanding of Russian culture in the post-Conceptualist era.

Gerald Janecek: is a professor emeritus of Russian at the University of Kentucky. He is the author of The Look of Russian Literature: Avant-Garde Visual Experiments, 1900–1930; ZAUM: The Transrational Poetry of Russian Futurism; and Sight and Sound Entwined: Studies of the New Russian Poetry; and the editor of Staging the Image: Dmitry Prigov as Artist and Writer.

Everything Has Already Been Written.

Moscow Conceptualist Poetry and Performance

Gerald Janecek (Author)

Publication Date: December 2018

Studies in Russian Literature and Theory

312 pages

Northwestern University Press

-Paper Text – $39.95

ISBN 978-0-8101-3901-5

-Cloth Text – $120.00

ISBN 978-0-8101-3902-2

# new books

Moscow Conceptualist Poetry and Performance

Gerald Janecek

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #Archive A-Z Sound Poetry, #Archive Concrete & Visual Poetry, #Editors Choice Archiv, - Book News, Archive I-J, Art & Literature News, Chlebnikov, Velimir, Conceptual writing, FDM Art Gallery, FLUXUS LEGACY, Kharms (Charms), Daniil, Majakovsky, Vladimir, Performing arts, REPRESSION OF WRITERS, JOURNALISTS & ARTISTS, Visual & Concrete Poetry

His Hands Were Gentle brings together, for the first time in both Spanish and English, the best of Víctor Jara’s lyrics, from early songs like ‘El arado’ to ‘Estadio Chile’ written in the hours before his execution there.

They reveal Jara as an ardent political poet, an eloquent advocate for the peasantry from which he arose, a socialist visionary and a poetic balladeer of the highest order.

Translations by Martín Espada, Eduardo Embry, John Green, Joan Jara and Adrian Mitchell.

Translations by Martín Espada, Eduardo Embry, John Green, Joan Jara and Adrian Mitchell.

Foreword by Joan Jara, Preface by Emma Thompson, Introduction by Martín Espada.

Víctor Jara (1932–73) was a legendary Chilean singer, songwriter, guitarist and theatre director. Between 1966 and 1973 he released eight albums, such as Canto libre and El derecho de vivir en paz. He was a member of the Communist Party of Chile, a prominent supporter of Salvador Allende’s Popular Unity government, and a leader of the New Song Movement during the cultural renaissance of the Allende years. In the days following the US–backed military coup of September 11, 1973, Jara was arrested, imprisoned and murdered. His recordings were banned for many years in Chile.

On my way to work

I think of you,

through the streets of the town

I think of you,

when I look at the faces

through steamy windows

not knowing who they are, where they go…

I think of you

my love, I think of you

of you, compañera of my life

and of the future

of the bitter hours and the happiness

of being able to live

working at the beginning of a story

without knowing the end.

(…)

When I come home

you are there

and we weave our dreams together…

Working at the beginning of a story

without knowing the end.

(From: On My Way to Work/ Cuando voy al trabajo.

Translated by Joan Jara)

His Hands Were Gentle brings together, for the first time in both Spanish and English, the best of V¡ctor Jara’s lyrics, from early songs like ‘El arado’ to ‘Estadio Chile’ written in the hours before his execution there. They reveal Jara as an ardent political poet, an eloquent advocate for the peasantry from which he arose, a socialist visionary and a poetic balladeer of the highest order. Translations by Martin Espada, Eduardo Embry, John Green, Joan Jara and Adrian Mitchell.

His Hands Were Gentle

Selected Lyrics of Victor Jara

Martin Espada (Editor)

Translations by Martín Espada, Eduardo Embry, John Green, Joan Jara and Adrian Mitchell.

Foreword by Joan Jara,

Preface by Emma Thompson,

Introduction by Martín Espada.

Paperback

84 pages

Publisher: Smokestack Books

Bilingual edition

2014

Language: English

ISBN-10: 0956814417

ISBN-13: 978-0956814418

Price: £8.95

# more poetry

His Hands Were Gentle

Selected Lyrics of Victor Jara

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: # Music Archive, #Editors Choice Archiv, - Book News, Archive I-J, Art & Literature News

Stairs and Whispers: D/deaf and Disabled Poets Write Back, edited by Sandra Alland, Khairani Barokka and Daniel Sluman, is a ground-breaking anthology examining UK disabled and D/deaf poetics.

Packed with fierce poetry, essays, photos and links to accessible online videos and audio recordings, it showcases a diversity of opinions and survival strategies for an ableist world.

With contributions that span Vispo to Surrealism, and range from hard-hitting political commentary to intimate lyrical pieces, these poets refuse to perform or inspire according to tired old narratives.

With poetry & prose by: Aaron Williamson, Abi Palmer, Abigail Penny, Alec Finlay, Alison Smith, Andra Simons, Angela Readman, Bea Webster, Cath Nichols, Catherine Edmunds, Cathy Bryant, Claire Cunningham, Clare Hill, Colin Hambrook, Daniel Sluman, Debjani Chatterjee, Donna Williams, El Clarke, Eleanor Ward, Emily Ingram, Gary Austin Quinn, Georgi Gill, Giles L. Turnbull, Gram Joel Davies, Grant Tarbard, Holly Magill, Isha, Jackie Hagan, Jacqueline Pemberton, Joanne Limburg, Julie McNamara, Karen Hoy, Khairani Barokka, Kitty Coles, Kuli Kohli, Lisa Kelly, Lydia Popowich, Mark Mace Smith, Markie Burnhope, Michelle Green, Miki Byrne, Miss Jacqui, Naomi Woddis, Nuala Watt, Rachael Boast, Raisa Kabir, Raymond Antrobus, Rosamund McCullain, Rose Cook, Sandra Alland, Saradha Soobrayen, Sarah Golightley, sean burn, Stephanie Conn

With poetry & prose by: Aaron Williamson, Abi Palmer, Abigail Penny, Alec Finlay, Alison Smith, Andra Simons, Angela Readman, Bea Webster, Cath Nichols, Catherine Edmunds, Cathy Bryant, Claire Cunningham, Clare Hill, Colin Hambrook, Daniel Sluman, Debjani Chatterjee, Donna Williams, El Clarke, Eleanor Ward, Emily Ingram, Gary Austin Quinn, Georgi Gill, Giles L. Turnbull, Gram Joel Davies, Grant Tarbard, Holly Magill, Isha, Jackie Hagan, Jacqueline Pemberton, Joanne Limburg, Julie McNamara, Karen Hoy, Khairani Barokka, Kitty Coles, Kuli Kohli, Lisa Kelly, Lydia Popowich, Mark Mace Smith, Markie Burnhope, Michelle Green, Miki Byrne, Miss Jacqui, Naomi Woddis, Nuala Watt, Rachael Boast, Raisa Kabir, Raymond Antrobus, Rosamund McCullain, Rose Cook, Sandra Alland, Saradha Soobrayen, Sarah Golightley, sean burn, Stephanie Conn

About the Editors: Alland’s collections include Blissful Times (BookThug, 2007) and Naturally Speaking (espresso, 2012). Barokka’s works include Indigenous Species (Tilted Axis, 2016) and Rope (Nine Arches, 2017). Sluman has two books with Nine Arches: Absence has a weight of its own (2012) and The Terrible (2015).

Stairs and Whispers:

D/deaf and Disabled Poets Write Back

Edited by Sandra Alland, Khairani Barokka & Daniel Sluman

Paperback

264 pages

Publisher: Nine Arches Press

2017

Language: English

ISBN-10: 1911027190

ISBN-13: 978-1911027195

Product Dimensions: 13.8 x 1 x 21.6 cm

eBook: Available at Amazon Kindle Store from September 2017

Discover the audio content that accompanies this book available on Soundcloud

Discover the video content that accompanies this book on Youtube

Price: £14.99

More information on website Nine Arches Press (http://ninearchespress.com/)

# more books

Stairs and Whispers:

D/deaf and Disabled Poets Write Back

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #Editors Choice Archiv, #More Poetry Archives, - Audiobooks, - Book News, - Book Stories, Art & Literature News, AUDIO, CINEMA, RADIO & TV, The Art of Reading

Winternachten festival geeft het woord aan schrijvers en dichters over brandende kwesties van nu.

Van 17 tot en met 20 januari 2019 presenteert het internationale literatuurfestival gesprekken, proza, poëzie, spoken word en films op twaalf Haagse podia. Ruim 80 binnen- en buitenlandse auteurs komen naar Den Haag. De 24e festivaleditie staat onder het motto Who Wants to Live Forever? in het teken van onze toekomst.

Winternachten internationaal literatuurfestival Den Haag inspireert met vertellen, lezen, luisteren en denken. Tijdens vier sfeervolle winterse dagen nodigen gesprekken, voordrachten en films uit tot nadenken over de grote vragen van onze tijd.

Sinds de start in 1995 is het festival uitgegroeid tot het belangrijkste internationale literaire evenement van Nederland waar schrijvers en dichters zich uitspreken over actuele thema’s. Ook bezoekers – onder hen veel wijkbewoners, studenten en scholieren – dragen actief bij met eigen verhalen of gedichten.

‘Who Wants to Live Forever?’

Ieder Winternachten festival krijgt een actueel thema mee. Deze 24e editie staat in het teken van het oeroude verlangen van de mens naar eeuwig leven in het licht van de technologie van nu. Onder het motto Who Wants to Live Forever? spreken auteurs onder meer over de relatie tussen mens en robot, over de impact van technologische innovatie en over hoop en vrees rond de politieke toekomst.

De 24e editie van het festival Winternachten staat met het motto ‘Who Wants to Live Forever’ in het teken van onze toekomst.

Gesprekken, voordachten, muziek en film over de verhouding tussen mens en robot, over nieuwe maakbaarheid door technologische innovatie, over hoop en vrees voor de politieke toekomst en over het terugkerend verlangen naar eeuwig leven.

Het festival verwelkomt uit het buitenland onder anderen schrijvers Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi uit Oeganda, Leni Zumas uit de VS, Basma Abdelaziz uit Egypte, Jennifer Clement uit Mexico, Ayelet Gundar-Goshen uit Israël, Mark O’Connell uit Ierland, David Van Reybrouck uit België, Ramayana-expert Arshia Sattar uit India en de Zuid-Afrikaanse rapper, spoken word-artiest en schrijver HemelBesem, Adam Zagajewski (Polen), Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi (Oeganda), Mark O’Connell (Ierland), Leni Zumas (VS) en Basma Abdelaziz (Egypte).

Uit Nederland nemen tientallen schrijvers, dichters, denkers en performers deel, zoals Akwasi, Elfie Tromp, Youp van ‘t Hek, Ian Buruma, Nelleke Noordervliet, Radna Fabias, Dimitri Verhulst, Aafke Romeijn, Damiaan Denys, Derek Otte, Luuk van Middelaar, Auke Hulst, Hanna Bervoets, Simone van Saarloos, Rodaan Al Galidi, ASKO/Schönberg, Lounar en Vamba Sherif.

De grote festivalavonden Friday Night Unlimited (vrijdag 18 januari) en Saturday Night Unlimited (zaterdag 19 januari) vormen de kern van het festival. De bezoeker kiest per avond uit vijfentwintig programma’s op zes podia in Theater aan het Spui en Filmhuis Den Haag. Dit jaar is in samenwerking met Filmhuis Den Haag het filmprogramma uitgebreid.

Nieuw is ook de Winternachten-editie van het spoken-word programma ‘Woorden worden Zinnen’ in het popcentrum Paard. Daarnaast zijn er festivalprogramma’s in Theater Dakota, de Speakers’ Corner in de Haagse Hogeschool, de bibliotheken Schilderswijk en Nieuw Waldeck en het International Institute of Social Studies.

Graag tot ziens in Theater aan het Spui, Filmhuis Den Haag, Paard, Theater Dakota, International Institute of Social Studies en de andere festivallocaties van dit jaar!

# more informatie op website writersunlimited.nl

Winternachten festival

17 tot en met 20 januari 2019

Den Haag

# fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: # Music Archive, #Biography Archives, #More Poetry Archives, - Book Lovers, - Bookstores, Art & Literature News, AUDIO, CINEMA, RADIO & TV, LITERARY MAGAZINES, PRESS & PUBLISHING, STREET POETRY, THEATRE, Winternachten

PARK vierde in oktober 2018 het vijfjarig bestaan en maakte een boek waarin de activiteiten in de periode 2016-2018 zijn vastgelegd.

Het rijk geïllustreerde full-colour boek, met teksten van Esther Porcelijn en Rob Moonen, is opnieuw vormgegeven door Berry van Gerwen.

Het rijk geïllustreerde full-colour boek, met teksten van Esther Porcelijn en Rob Moonen, is opnieuw vormgegeven door Berry van Gerwen.

Het telt ruim 240 pagina’s en heeft een oplage van 600 stuks.

Alle tentoonstellingsprojecten, de bijna 200 exposerende kunstenaars en de extra activiteiten in de periode 2016-2018 komen aan bod. Het is de opvolger van het eerder verschenen ‘PARK 2013-2015‘.

Het boek kost € 20,- inclusief BTW, exclusief eventuele verzendkosten. Het verschijnt verschijnt op zondag 16 december 2018 tijdens een boekpresentatie om 16:00 uur bij PARK.

U kunt uw exemplaar ook bestellen via shop@park013.nl

PARK 2016-2018

Teksten van Esther Porcelijn en Rob Moonen

Vormgeving door Berry van Gerwen

PARK

Platform for visual arts

240 pagina’s

Oplage 600 stuks

€ 20,-

PARK is een kunstinitiatief opgericht in 2013 door Rob Moonen in samenwerking met een zestal andere Tilburgse kunstenaars. Op dit moment bestaat de PARK werkgroep uit Linda Arts, René Korten, Rob Moonen en Liza Voetman.

PARK richt zich op actuele ontwikkelingen binnen de hedendaagse kunst én op kunstenaars met gedegen ervaring en bewezen kwaliteit. Er wordt plek geboden aan regionale collega’s maar ook aan landelijk of internationaal opererende kunstenaars, juist om een positieve bijdrage aan de discussie over actuele kunst tot stand te brengen. De werkgroep ambieert het podium van belang te laten zijn op landelijk niveau, maar bij elk project wordt met nadruk gezocht naar een inhoudelijke koppeling met de stad. De werkgroep is er van overtuigd dat samenwerking met andere partijen de zichtbaarheid en functionaliteit van de plek zal versterken, maar ook dat de plek een waardevolle stimulans voor de beeldende kunst in de stad en de regio zal kunnen zijn.

PARK wil steeds nieuwe verbindingen leggen, bijvoorbeeld door (internationaal opererende) curatoren uit te nodigen om kennis te nemen van de keur aan regionale beeldende kunstenaars en daarvan mogelijk enkele op te nemen in een tentoonstellingsproject. PARK wil een bijdrage leveren aan de ontwikkeling van een gunstig productie- en vestigingsklimaat voor beeldend kunstenaars uit de regio door deze in contact te brengen met een nationaal en internationaal netwerk.

Per jaar worden er vijf projecten gerealiseerd met waar mogelijk een bijpassend raamprogramma in de vorm van lezingen, kunstenaarsgesprekken, muziek en film.

PARK

Wilhelminapark 53, 5041 ED Tilburg

info@park013.nl

Twitter.com/ParkTilburg

Facebook.com/Park013

Instagram.com/platform_for_visual_arts

Tijdens tentoonstellingen geopend:

vrijdag 13.00 – 17.00 uur

zaterdag 13.00 – 17.00 uur

zondag 13.00 – 17.00 uur

Toegang is gratis

PARK ligt op 10 minuten loopafstand van het Centraal Station Tilburg in de nabijheid van Museum De Pont. Er is beperkt gratis parkeergelegenheid voor de deur.

# new books

visual arts

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #Editors Choice Archiv, - Book News, Architecture, Art & Literature News, Art Criticism, FDM Art Gallery, Linda Arts, Park, Performing arts, Porcelijn, Esther, Porcelijn, Esther, Sculpture, The talk of the town

`Doe de deur achter je dicht en loop maar naar boven’, roept Tijgers moeder, de lieve roodharige heks.

Mels holt de trap op, zijn vingers roffelend langs de spijlen. De deur van Tijgers slaapkamer staat open. Thija is er al. Ze zit op het hoofdeinde naast Tijger, haar arm om zijn hals. Hun ogen zijn gericht op iets wat voor Tijger op het bed ligt, maar Mels kan het niet zien.

Mels holt de trap op, zijn vingers roffelend langs de spijlen. De deur van Tijgers slaapkamer staat open. Thija is er al. Ze zit op het hoofdeinde naast Tijger, haar arm om zijn hals. Hun ogen zijn gericht op iets wat voor Tijger op het bed ligt, maar Mels kan het niet zien.

Ze hebben hem niet gehoord. Geruisloos gaat Mels achterwaarts de trap af, opent zacht de voordeur en sluipt naar buiten. Met kloppend hart loopt hij naar de Wijer, de handen gebald in zijn broekzakken, alsof hij iemand wil wurgen.

Pas laat komt hij thuis. Het is al donker. Zijn moeder vraagt niets, ze begrijpt altijd alles.

Ze geeft hem thee met een stapel biscuitjes en wacht tot hij tot rust is gekomen.

`Ik heb slecht nieuws’, zegt ze dan. `Wil je het horen. Of is het voor vandaag te veel?’

`Zeg maar.’

`Die zigeunerjongen is gestorven.’

`Hij wilde nog lang niet dood.’ Mels is geschokt. En kwaad. `Het is niet eerlijk.’

`In het leven is niets eerlijk. Wat je graag wilt hebben, krijg je nooit.’

Denkt ze aan zijn vader? Hij vindt het verschrikkelijk dat die twee zo verschillend zijn en bijna nooit met elkaar praten. Zou zijn moeder gelukkiger zijn geweest met een andere man?

Omdat zijn vader er niet is, kan hij wat tegen zijn moeder aanhangen op de bank, op zoek naar troost. Zijn vader wil nooit dat hij zich door haar laat aanhalen. Hij vindt het iets voor moederskindjes.

Die nacht kan hij niet slapen. De hele nacht klinkt er vioolmuziek van heel ver. Woedende muziek. Alsof er wolven naar de maan huilen.

Als het nog donker is, staat hij al op en zoekt op de radio naar verre zenders. Vier uur. Tijd voor nachtraven. De fluitende en joelende tonen die van wie weet waar komen, stemmen hem rustig. Hij weet zeker dat het geheime boodschappen zijn. Misschien zijn er berichten bij uit China. Van de Chinese communisten voor de communisten hier die in het land geheime cellen opzetten, om later, samen met de Chinese legers, de macht te grijpen. Grootvader Rudolf weet zeker dat het ooit zover komt. Hij heeft visioenen van horden grijnzende gele mannetjes die het land onder de voet lopen. Voor elk van hen die sneuvelt komen er tientallen anderen.

Volgens grootvader hebben de Chinezen meer ruimte nodig in de wereld omdat ze met zo veel zijn. `Ze planten zich voort als ratten’, zegt hij. `Alleen maar om de wereld te overheersen. Wij zijn hier al bijna net zover. In het Rood Dorp zijn ook gezinnen met tien of twaalf kinderen. Die leggen rode lopers voor hen uit. Heel Europa zal worden platgewalst door het Gele Gevaar.’ `Is dat net zoiets als de gele verf?’ `Jazeker, mijn jongen, alleen wat erger.’ Maar grootvader Bernhard denkt er precies het tegenovergestelde van. Hij zegt juist dat de Chinezen liever in China blijven en dat China groot genoeg voor hen is. `En als ze dan toch zullen komen, dan zal ik ze vriendelijk ontvangen. In China heb ik alleen maar aardige mensen gezien.’

Mels probeert de code van een zender die een aantal verschillende pieptonen laat horen, te ontcijferen. Drie pieptonen in veel verschillende combinaties. Hij schrijft zijn vingers blauw op een velletje papier, maar alle rijtjes naast elkaar laten geen enkel verband met elkaar zien. Is het een zender die er juist voor bedoeld is om de vijand in de war te brengen? Hij komt er niet eens achter van wie de zender is en uit welk land hij zendt.

Al vroeg staat hij bij Thija aan de deur. Tijger heeft hem voorbij zien komen en volgt hem op de voet.

`Waar was je gisteren?’ vraagt Thija.

`Ik kon niet’, zegt hij. `Heb jij vannacht die viool ook gehoord?’

`Ik heb niets gehoord.’

`Jacob is dood’, zegt Mels. `Het moet zijn vader zijn geweest.’

`We wisten dat hij doodging.’

`We hadden vaker naar hem toe moeten gaan.’

`Stom, om zoiets achteraf te zeggen’, zegt Thija.

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (083)

wordt vervolgd

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

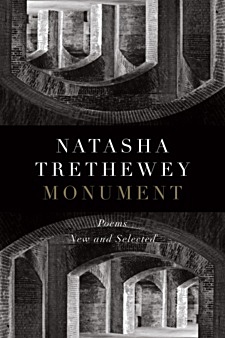

Layering joy and urgent defiance—against physical and cultural erasure, against white supremacy whether intangible or graven in stone—Trethewey’s work gives pedestal and witness to unsung icons.

Monument, Trethewey’s first retrospective, draws together verse that delineates the stories of working class African American women, a mixed-race prostitute, one of the first black Civil War regiments, mestizo and mulatto figures in Casta paintings, Gulf coast victims of Katrina. Through the collection, inlaid and inextricable, winds the poet’s own family history of trauma and loss, resilience and love.

Monument, Trethewey’s first retrospective, draws together verse that delineates the stories of working class African American women, a mixed-race prostitute, one of the first black Civil War regiments, mestizo and mulatto figures in Casta paintings, Gulf coast victims of Katrina. Through the collection, inlaid and inextricable, winds the poet’s own family history of trauma and loss, resilience and love.

In this setting, each section, each poem drawn from an “opus of classics both elegant and necessary,”* weaves and interlocks with those that come before and those that follow.

As a whole, Monument casts new light on the trauma of our national wounds, our shared history. This is a poet’s remarkable labor to source evidence, persistence, and strength from the past in order to change the very foundation of the vocabulary we use to speak about race, gender, and our collective future.

*Academy of American Poets’ chancellor Marilyn Nelson

Natasha Trethewey, two term U.S. Poet Laureate, Pulitzer Prize winner, and 2017 Heinz Award recipient, has written five collections of poetry and one book of nonfiction. An American Academy of Arts and Sciences fellow, she is currently Board of Trustees professor of English at Northwestern University. She lives in Evanston, Illinois.

Monument: Poems New and Selected

by Natasha Trethewey

Poetry

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

Format: Hardcover

ISBN-13/EAN: 9781328507846

ISBN-10: 132850784X

Pages: 208

Price: $26.00

November 6, 2018

# new books

Natasha Trethewey

Monument: Poems New and Selected

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive S-T, Art & Literature News

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature