Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

Christian Kunda Mutoki porte un nouveau regard sur Le Horla de Guy de Maupassant.

Il est précédé d’une préface et suivi d’une postface.

Il est précédé d’une préface et suivi d’une postface.

Il vient rafraîchir les problématiques qui touchent à la morale, à l’athéisme, à des amours tumultueuses et infidèles. . .

Le monde d’aujourd’hui diffère-t-il de celui décrit au XIXe siècle par l’écrivain français ? La science a-t-elle amélioré la condition existentielle de l’homme ?

Voici quelques questions majeures qui trouvent ici un regard neuf.

Christian Kunda Mutoki a préparé sa thèse de doctorat à l’Université Paul Verlaine, actuelle Université de la Lorraine (Metz, France). Il est écrivain et professeur de Littérature et civilisation françaises à l’Université de Lubumbashi, en RDC.

GUY DE MAUPASSANT

Une certaine idée de l’homme dans Le Horla

Christian Kunda Mutoki

Cahiers des sciences du langage

Langue Linguistique Littérature

Broché

Format : 15,5 x 24 cm

ISBN : 978-2-8066-3665-2

14 décembre 2018

70 pages

€ 11,5

# New books

Une certaine idée de l’homme dans Le Horla

de Guy de Maupassant

Christian Kunda Mutoki

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive M-N, Archive M-N, Art & Literature News, Guy de Maupassant, Maupassant, Guy de, Maupassant, Guy de

THE RACE QUESTION

Scene—Race track. Enter old coloured man, seating himself.

“Oomph, oomph. De work of de devil sho’ do p’ospah. How ‘do, suh? Des tol’able, thankee, suh. How you come on? Oh, I was des a-sayin’ how de wo’k of de ol’ boy do p’ospah. Doesn’t I frequent the racetrack? No, suh; no, suh. I’s Baptis’ myse’f, an’ I ‘low hit’s all devil’s doin’s. Wouldn’t ‘a’ be’n hyeah to-day, but I got a boy named Jim dat’s long gone in sin an’ he gwine ride one dem hosses. Oomph, dat boy! I sut’ny has talked to him and labohed wid him night an’ day, but it was allers in vain, an’ I’s feahed dat de day of his reckonin’ is at han’.

“Ain’t I nevah been intrusted in racin’? Humph, you don’t s’pose I been dead all my life, does you? What you laffin’ at? Oh, scuse me, scuse me, you unnerstan’ what I means. You don’ give a ol’ man time to splain hisse’f. What I means is dat dey has been days when I walked in de counsels of de on-gawdly and set in de seats of sinnahs; and long erbout dem times I did tek most ovahly strong to racin’.

“Ain’t I nevah been intrusted in racin’? Humph, you don’t s’pose I been dead all my life, does you? What you laffin’ at? Oh, scuse me, scuse me, you unnerstan’ what I means. You don’ give a ol’ man time to splain hisse’f. What I means is dat dey has been days when I walked in de counsels of de on-gawdly and set in de seats of sinnahs; and long erbout dem times I did tek most ovahly strong to racin’.

“How long dat been? Oh, dat’s way long back, ‘fo’ I got religion, mo’n thuty years ago, dough I got to own I has fell from grace several times sense.

“Yes, suh, I ust to ride. Ki-yi! I nevah furgit de day dat my ol’ Mas’ Jack put me on ‘June Boy,’ his black geldin’, an’ say to me, ‘Si,’ says he, ‘if you don’ ride de tail offen Cunnel Scott’s mare, “No Quit,” I’s gwine to larrup you twell you cain’t set in de saddle no mo’.’ Hyah, hyah. My ol’ Mas’ was a mighty han’ fu’ a joke. I knowed he wan’t gwine to do nuffin’ to me.

“Did I win? Why, whut you spec’ I’s doin’ hyeah ef I hadn’ winned? W’y, ef I’d ‘a’ let dat Scott maih beat my ‘June Boy’ I’d ‘a’ drowned myse’f in Bull Skin Crick.

“Yes, suh, I winned; w’y, at de finish I come down dat track lak hit was de Jedgment Day an’ I was de las’ one up! Ef I didn’t race dat maih’s tail clean off, I ‘low I made hit do a lot o’ switchin’. An’ aftah dat my wife Mandy she ma’ed me. Hyah, hyah, I ain’t bin much on hol’in’ de reins sence.

“Sh! dey comin’ in to wa’m up. Dat Jim, dat Jim, dat my boy; you nasty putrid little rascal. Des a hundred an’ eight, suh, des a hundred an’ eight. Yas, suh, dat’s my Jim; I don’t know whaih he gits his dev’ment at.

“What’s de mattah wid dat boy? Whyn’t he hunch hisse’f up on dat saddle right? Jim, Jim, whyn’t you limber up, boy; hunch yo’se’f up on dat hoss lak you belonged to him and knowed you was dah. What I done showed you? De black raskil, goin’ out dah tryin’ to disgrace his own daddy. Hyeah he come back. Dat’s bettah, you scoun’ril.

“Dat’s a right smaht-lookin’ hoss he’s a-ridin’, but I ain’t a-trustin’ dat bay wid de white feet—dat is, not altogethah. She’s a favourwright too; but dey’s sumpin’ else in dis worl’ sides playin’ favourwrights. Jim bettah had win dis race. His hoss ain’t a five to one shot, but I spec’s to go way fum hyeah wid money ernuff to mek a donation on de pa’sonage.

“Does I bet? Well, I don’ des call hit bettin’; but I resks a little w’en I t’inks I kin he’p de cause. ‘Tain’t gamblin’, o’ co’se; I wouldn’t gamble fu nothin’, dough my ol’ Mastah did ust to say dat a honest gamblah was ez good ez a hones’ preachah an’ mos’ nigh ez skace.

“Look out dah, man, dey’s off, dat nasty bay maih wid de white feet leadin’ right fu’m ‘de pos’. I knowed it! I knowed it! I had my eye on huh all de time. Oh, Jim, Jim, why didn’t you git in bettah, way back dah fouf? Dah go de gong! I knowed dat wasn’t no staht. Troop back dah, you raskils, hyah, hyah.

“I wush dat boy wouldn’t do so much jummying erroun’ wid dat hoss. Fust t’ing he know he ain’t gwine to know whaih he’s at.

“Dah, dah dey go ag’in. Hit’s a sho’ t’ing dis time. Bettah, Jim, bettah. Dey didn’t leave you dis time. Hug dat bay mare, hug her close, boy. Don’t press dat hoss yit. He holdin’ back a lot o’ t’ings.

“He’s gainin’! doggone my cats, he’s gainin’! an’ dat hoss o’ his’n gwine des ez stiddy ez a rockin’-chair. Jim allus was a good boy.

“Confound these spec’s, I cain’t see ’em skacely; huh, you say dey’s neck an’ neck; now I see ’em! now I see ’em! and Jimmy’s a-ridin’ like——Huh, huh, I laik to said sumpin’.

“De bay maih’s done huh bes’, she’s done huh bes’! Dey’s turned into the stretch an’ still see-sawin’. Let him out, Jimmy, let him out! Dat boy done th’owed de reins away. Come on, Jimmy, come on! He’s leadin’ by a nose. Come on, I tell you, you black rapscallion, come on! Give ’em hell, Jimmy! give ’em hell! Under de wire an’ a len’th ahead. Doggone my cats! wake me up w’en dat othah hoss comes in.

“No, suh, I ain’t gwine stay no longah, I don’t app’ove o’ racin’, I’s gwine ‘roun’ an’ see dis hyeah bookmakah an’ den I’s gwine dreckly home, suh, dreckly home. I’s Baptis’ myse’f, an’ I don’t app’ove o’ no sich doin’s!”

Paul Laurence Dunbar

(1872 – 1906)

The Race Question

From The Heart Of Happy Hollow, a collection of short stories reprinted in 1904 by Dodd, Mead and Company, New York.

Short story

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: *Archive African American Literature, Archive C-D, Archive C-D, Dunbar, Paul Laurence, Dunbar, Paul Laurence, Paul Laurence Dunbar, Paul Laurence Dunbar

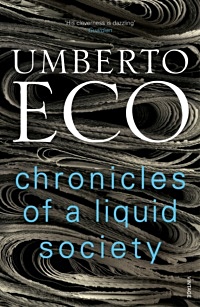

The final book from one of Europe’s cultural giants: an entertaining collection of essays about the modern world – from unbridled individualism to mobile phones.

Umberto Eco was an international cultural superstar. A celebrated essayist as well as novelist, in this, his last collection, he explores many aspects of the modern world with irrepressible curiosity and wisdom written in his uniquely ironic voice.

Umberto Eco was an international cultural superstar. A celebrated essayist as well as novelist, in this, his last collection, he explores many aspects of the modern world with irrepressible curiosity and wisdom written in his uniquely ironic voice.

Written by Eco as articles for his regular column in l’Espresso magazine, he brings his dazzling erudition, incisiveness and keen sense of the everyday to bear on topics such as popular culture and politics, unbridled individualism, conspiracies, the old and the young, mobile phones, mass media, racism, good manners and the crisis in ideological values.

It is a final gift to his readers – astute, witty and illuminating.

“ A swan song from one of Europe’s great intellectuals…Eco entertains with his intellect, humor, and insatiable curiosity…there’s much here to enjoy and ponder ”. Tim Parks, Guardian

Chronicles of a Liquid Society

by Umberto Eco

Paperback

ISBN 9781784705206

Hardback

ISNB 9781911215318

2017/2018

Harvill Secker / Vintage

320 pages

Language & Literary Studies

# New books

Chronicles of a Liquid Society

by Umberto Eco

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive E-F, Art & Literature News, AUDIO, CINEMA, RADIO & TV, DICTIONARY OF IDEAS, MONTAIGNE, Museum of Literary Treasures, NONFICTION: ESSAYS & STORIES, Umberto Eco

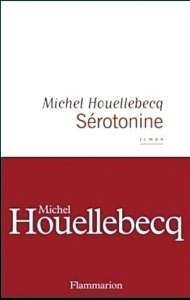

«Mes croyances sont limitées, mais elles sont violentes. Je crois à la possibilité du royaume restreint. Je crois à l’amour» écrivait récemment Michel Houellebecq.

«Mes croyances sont limitées, mais elles sont violentes. Je crois à la possibilité du royaume restreint. Je crois à l’amour» écrivait récemment Michel Houellebecq.

Le narrateur de Sérotonine approuverait sans réserve. Son récit traverse une France qui piétine ses traditions, banalise ses villes, détruit ses campagnes au bord de la révolte. Il raconte sa vie d’ingénieur agronome, son amitié pour un aristocrate agriculteur (un inoubliable personnage de roman – son double inversé), l’échec des idéaux de leur jeunesse, l’espoir peut-être insensé de retrouver une femme perdue.

Ce roman sur les ravages d’un monde sans bonté, sans solidarité, aux mutations devenues incontrôlables, est aussi un roman sur le remords et le regret.

Michel Houellebecq

Sérotonine

Littérature française

Flammarion

À paraître le 04/01/2019

352 pages

139 x 210 mm

Broché

EAN : 9782081471757

ISBN : 9782081471757

€ 22,00

# Nouveau roman

Michel Houellebecq

Sérotonine

•fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive G-H, Art & Literature News, Michel Houellebecq

The Blind Spot

“You’ve just come back from Adelaide’s funeral, haven’t you?” said Sir Lulworth to his nephew; “I suppose it was very like most other funerals?”

“I’ll tell you all about it at lunch,” said Egbert.

“You’ll do nothing of the sort. It wouldn’t be respectful either to your great-aunt’s memory or to the lunch. We begin with Spanish olives, then a borshch, then more olives and a bird of some kind, and a rather enticing Rhenish wine, not at all expensive as wines go in this country, but still quite laudable in its way. Now there’s absolutely nothing in that menu that harmonises in the least with the subject of your great-aunt Adelaide or her funeral. She was a charming woman, and quite as intelligent as she had any need to be, but somehow she always reminded me of an English cook’s idea of a Madras curry.”

“You’ll do nothing of the sort. It wouldn’t be respectful either to your great-aunt’s memory or to the lunch. We begin with Spanish olives, then a borshch, then more olives and a bird of some kind, and a rather enticing Rhenish wine, not at all expensive as wines go in this country, but still quite laudable in its way. Now there’s absolutely nothing in that menu that harmonises in the least with the subject of your great-aunt Adelaide or her funeral. She was a charming woman, and quite as intelligent as she had any need to be, but somehow she always reminded me of an English cook’s idea of a Madras curry.”

“She used to say you were frivolous,” said Egbert. Something in his tone suggested that he rather endorsed the verdict.

“I believe I once considerably scandalised her by declaring that clear soup was a more important factor in life than a clear conscience. She had very little sense of proportion. By the way, she made you her principal heir, didn’t she?”

“Yes,” said Egbert, “and executor as well. It’s in that connection that I particularly want to speak to you.”

“Business is not my strong point at any time,” said Sir Lulworth, “and certainly not when we’re on the immediate threshold of lunch.”

“It isn’t exactly business,” explained Egbert, as he followed his uncle into the dining-room.

“It’s something rather serious. Very serious.”

“Then we can’t possibly speak about it now,” said Sir Lulworth; “no one could talk seriously during a borshch. A beautifully constructed borshch, such as you are going to experience presently, ought not only to banish conversation but almost to annihilate thought. Later on, when we arrive at the second stage of olives, I shall be quite ready to discuss that new book on Borrow, or, if you prefer it, the present situation in the Grand Duchy of Luxemburg. But I absolutely decline to talk anything approaching business till we have finished with the bird.”

For the greater part of the meal Egbert sat in an abstracted silence, the silence of a man whose mind is focussed on one topic. When the coffee stage had been reached he launched himself suddenly athwart his uncle’s reminiscences of the Court of Luxemburg.

“I think I told you that great-aunt Adelaide had made me her executor. There wasn’t very much to be done in the way of legal matters, but I had to go through her papers.”

“That would be a fairly heavy task in itself. I should imagine there were reams of family letters.”

“Stacks of them, and most of them highly uninteresting. There was one packet, however, which I thought might repay a careful perusal. It was a bundle of correspondence from her brother Peter.”

“The Canon of tragic memory,” said Lulworth.

“Exactly, of tragic memory, as you say; a tragedy that has never been fathomed.”

“Probably the simplest explanation was the correct one,” said Sir Lulworth; “he slipped on the stone staircase and fractured his skull in falling.”

Egbert shook his head. “The medical evidence all went to prove that the blow on the head was struck by some one coming up behind him. A wound caused by violent contact with the steps could not possibly have been inflicted at that angle of the skull. They experimented with a dummy figure falling in every conceivable position.”

“But the motive?” exclaimed Sir Lulworth; “no one had any interest in doing away with him, and the number of people who destroy Canons of the Established Church for the mere fun of killing must be extremely limited. Of course there are individuals of weak mental balance who do that sort of thing, but they seldom conceal their handiwork; they are more generally inclined to parade it.”

“His cook was under suspicion,” said Egbert shortly.

“I know he was,” said Sir Lulworth, “simply because he was about the only person on the premises at the time of the tragedy. But could anything be sillier than trying to fasten a charge of murder on to Sebastien? He had nothing to gain, in fact, a good deal to lose, from the death of his employer. The Canon was paying him quite as good wages as I was able to offer him when I took him over into my service. I have since raised them to something a little more in accordance with his real worth, but at the time he was glad to find a new place without troubling about an increase of wages. People were fighting rather shy of him, and he had no friends in this country. No; if anyone in the world was interested in the prolonged life and unimpaired digestion of the Canon it would certainly be Sebastien.”

“People don’t always weigh the consequences of their rash acts,” said Egbert, “otherwise there would be very few murders committed. Sebastien is a man of hot temper.”

“He is a southerner,” admitted Sir Lulworth; “to be geographically exact I believe he hails from the French slopes of the Pyrenees. I took that into consideration when he nearly killed the gardener’s boy the other day for bringing him a spurious substitute for sorrel. One must always make allowances for origin and locality and early environment; ‘Tell me your longitude and I’ll know what latitude to allow you,’ is my motto.”

“There, you see,” said Egbert, “he nearly killed the gardener’s boy.”

“My dear Egbert, between nearly killing a gardener’s boy and altogether killing a Canon there is a wide difference. No doubt you have often felt a temporary desire to kill a gardener’s boy; you have never given way to it, and I respect you for your self-control. But I don’t suppose you have ever wanted to kill an octogenarian Canon. Besides, as far as we know, there had never been any quarrel or disagreement between the two men. The evidence at the inquest brought that out very clearly.”

“Ah!” said Egbert, with the air of a man coming at last into a deferred inheritance of conversational importance, “that is precisely what I want to speak to you about.”

He pushed away his coffee cup and drew a pocket-book from his inner breast-pocket. From the depths of the pocket-book he produced an envelope, and from the envelope he extracted a letter, closely written in a small, neat handwriting.

“One of the Canon’s numerous letters to Aunt Adelaide,” he explained, “written a few days before his death. Her memory was already failing when she received it, and I daresay she forgot the contents as soon as she had read it; otherwise, in the light of what subsequently happened, we should have heard something of this letter before now. If it had been produced at the inquest I fancy it would have made some difference in the course of affairs. The evidence, as you remarked just now, choked off suspicion against Sebastien by disclosing an utter absence of anything that could be considered a motive or provocation for the crime, if crime there was.”

“Oh, read the letter,” said Sir Lulworth impatiently.

“It’s a long rambling affair, like most of his letters in his later years,” said Egbert. “I’ll read the part that bears immediately on the mystery.

“‘I very much fear I shall have to get rid of Sebastien. He cooks divinely, but he has the temper of a fiend or an anthropoid ape, and I am really in bodily fear of him. We had a dispute the other day as to the correct sort of lunch to be served on Ash Wednesday, and I got so irritated and annoyed at his conceit and obstinacy that at last I threw a cupful of coffee in his face and called him at the same time an impudent jackanapes. Very little of the coffee went actually in his face, but I have never seen a human being show such deplorable lack of self-control. I laughed at the threat of killing me that he spluttered out in his rage, and thought the whole thing would blow over, but I have several times since caught him scowling and muttering in a highly unpleasant fashion, and lately I have fancied that he was dogging my footsteps about the grounds, particularly when I walk of an evening in the Italian Garden.’

“It was on the steps in the Italian Garden that the body was found,” commented Egbert, and resumed reading.

“‘I daresay the danger is imaginary; but I shall feel more at ease when he has quitted my service.’”

Egbert paused for a moment at the conclusion of the extract; then, as his uncle made no remark, he added: “If lack of motive was the only factor that saved Sebastien from prosecution I fancy this letter will put a different complexion on matters.”

“Have you shown it to anyone else?” asked Sir Lulworth, reaching out his hand for the incriminating piece of paper.

“No,” said Egbert, handing it across the table, “I thought I would tell you about it first. Heavens, what are you doing?”

Egbert’s voice rose almost to a scream. Sir Lulworth had flung the paper well and truly into the glowing centre of the grate. The small, neat handwriting shrivelled into black flaky nothingness.

“What on earth did you do that for?” gasped Egbert. “That letter was our one piece of evidence to connect Sebastien with the crime.”

“That is why I destroyed it,” said Sir Lulworth.

“But why should you want to shield him?” cried Egbert; “the man is a common murderer.”

“A common murderer, possibly, but a very uncommon cook.”

The Blind Spot

From ‘Beasts and Super-Beasts’

by Saki (H. H. Munro)

(1870 – 1916)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Saki, Saki, The Art of Reading

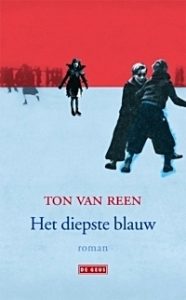

`Als we China hebben gezien, zullen we pas begrijpen hoe nietig het hier allemaal is’, zegt Tijger.

`Hoe klein het dorp is, hoe smal de beek, hoe de fabriek stinkt.’

`Hoe klein het dorp is, hoe smal de beek, hoe de fabriek stinkt.’

`Jij hoeft helemaal niet op reis te gaan om dat te ontdekken’, zegt Thija. `Jij weet het nu al.’

`Na de zomervakantie gaan we ieder naar een andere school’, zegt Tijger.

`Het is ellendig’, zegt Mels. `Ik wil helemaal niet naar een andere school. We moeten bij elkaar blijven.’

`We hebben er niets over te zeggen’, zegt Tijger. `Het is allemaal al beslist.’

`Stom’, zegt Thija. `Ik zal jullie maanden niet zien.’

`Dat is het ergst van alles,’ zegt Mels, `dat jij naar kostschool moet.’

`Ik wil het niet. Mijn váder wil het.’

`Ons vragen ze niets’, zegt Mels.

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (085)

wordt vervolgd

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

Qui suis-je ?

Qui suis-je ?

D’où je viens ?

Je suis Antonin Artaud

et que je le dise

comme je sais le dire

immédiatement

vous verrez mon corps actuel

voler en éclats

et se ramasser

sous dix mille aspects

notoires

un corps neuf

où vous ne pourrez

plus jamais

m’oublier.

Antonin Artaud

Poème

Qui suis-je ?

(1896 – 1948)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Antonin Artaud, Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Artaud, Antonin

Deathwatch, Jean Genet‘s earliest, shortest and most formally straightforward play, was first performed in Paris in 1949.

It retains an intense power and makes an excellent introduction to his later dramas – The Maids, The Balcony, The Blacks, The Screens. The French text of Deathwatch, published by Gallimard, was extensively altered by Genet during rehearsal; and Bernard Frechtman’s translation is of the final ‘performance’ version, which supersedes the original published text.Three convicts share a cramped prison cell.

It retains an intense power and makes an excellent introduction to his later dramas – The Maids, The Balcony, The Blacks, The Screens. The French text of Deathwatch, published by Gallimard, was extensively altered by Genet during rehearsal; and Bernard Frechtman’s translation is of the final ‘performance’ version, which supersedes the original published text.Three convicts share a cramped prison cell.

There is no question as to which of them is the dominant dog in the pack: Green Eyes (Yeux-Verts) has brutally murdered a woman and is to be executed.

Lefranc and the younger novice-like Maurice are inside for less grave crimes. But both of them covet Green Eyes’ attention, baiting each other in the process, a duel that drives inexorably toward violence

Three young convicts share a cell. Locked into a world of dangerous rivalries, criminals Lefranc and Maurice compete for the attention of the charismatic condemned man, Green-Eyes.

Informed by his own experience in French prisons, Jean Genet’s first play, Deathwatch is an explosive exploration of the inversion of moral order.

Genet was one of the most prominent and provocative writers of the twentieth century.

Jean Genet’s Deathwatch premiered in this translation by David Rudkin with the Royal Shakespeare Company in 1987 and was revived at the Print Room, London, in April 2016.

Jean Genet was born in Paris in 1910. An illegitimate child who never knew his parents, he was abandoned to the Public Assistance Authorities. He was ten when he was sent to a reformatory for stealing; thereafter he spent time in the prisons of nearly every country he visited in thirty years of prowling through the European underworld. With ten convictions for theft in France to his credit he was, the eleventh time, condemned to life imprisonment. Eventually he was granted a pardon by President Auriol as a result of appeals from France’s leading artists and writers led by Jean Cocteau. His first novel, Our Lady of the Flowers, was written while he was in prison, followed by Miracle of the Rose, the autobiographical The Thief’s Journal, Querelle of Brest and Funeral Rites. He wrote six plays: The Balcony, The Blacks, The Screens, The Maids, Deathwatch and Splendid’s (the manuscript of which was rediscovered only in 1993). Jean Genet died in 1986.

Deathwatch

by Jean Genet

English

Translated by David Rudkin

Play

Faber & Faber

Paperback

64 pages

2016

ISBN 9780571332618

£9.99

# more books

Deathwatch by Jean Genet

• fleursdumal.nl

More in: - Book Lovers, - Book Stories, Archive G-H, Art & Literature News, AUDIO, CINEMA, RADIO & TV, CRIME & PUNISHMENT, Jean Genet, THEATRE

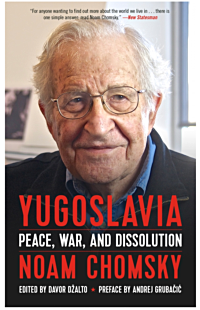

The Balkans, in particular the turbulent ex-Yugoslav territory, have been among the most important world regions in Noam Chomsky’s political reflections and activism for decades.

His articles, public talks, and correspondence have provided a critical voice on political and social issues crucial not only to the region but the entire international community, including “humanitarian intervention,” the relevance of international law in today’s politics, media manipulations, and economic crisis as a means of political control.

This volume provides a comprehensive survey of virtually all of Chomsky’s texts and public talks that focus on the region of the former Yugoslavia, from the 1970s to the present. With numerous articles and interviews, this collection presents a wealth of materials appearing in book form for the first time along with reflections on events twenty-five years after the official end of communist Yugoslavia and the beginning of the war in Bosnia.

This volume provides a comprehensive survey of virtually all of Chomsky’s texts and public talks that focus on the region of the former Yugoslavia, from the 1970s to the present. With numerous articles and interviews, this collection presents a wealth of materials appearing in book form for the first time along with reflections on events twenty-five years after the official end of communist Yugoslavia and the beginning of the war in Bosnia.

The book opens with a personal and wide-ranging preface by Andrej Grubačić that affirms the ongoing importance of Yugoslav history and identity, providing a context for understanding Yugoslavia as an experiment in self-management, antifascism, and mutlethnic coexistence.

Noam Chomsky (1928) is Institute Professor in the Department of Linguistics and Philosophy at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Boston. A member of the American Academy of Science, he has published widely in both linguistics and current affairs. His books include At War with Asia, Towards a New Cold War, Fateful Triangle: The U. S., Israel and the Palestinians, Necessary Illusions, Hegemony or Survival, Deterring Democracy, Failed States: The Abuse of Power and the Assault on Democracy and Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media.

Title: Yugoslavia: Peace, War, and Dissolution

Author: Noam Chomsky

Edited by Davor Džalto

Preface by Andrej Grubačić

Subjects: Politics / History-Europe

Publisher: PM Press

ISBN: 978-1-62963-442-5

Published: 04/2018

Language: English

Format: Paperback

Size: 6×9

240 pages

$15.63

# new books

Noam Chomsky

Yugoslavia: Peace, War, and Dissolution

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Book Stories, Archive C-D, AUDIO, CINEMA, RADIO & TV, MONTAIGNE, Noam Chomsky, WAR & PEACE

Vanaf 30 november 2018 tot 28 april 2019 presenteert het Bonnefantenmuseum het omvangrijke retrospectief Someone is in my House van de Amerikaanse kunstenaar David Lynch.

Hoewel David Lynch onmiskenbaar een spilfiguur is in de internationale film- en tv-wereld, is zijn werk als beeldend kunstenaar veel minder bekend. Dat is op zijn minst vreemd, aangezien Lynch zelf altijd heeft benadrukt dat hij zichzelf vóór alles ziet als beeldend kunstenaar.

Hoewel David Lynch onmiskenbaar een spilfiguur is in de internationale film- en tv-wereld, is zijn werk als beeldend kunstenaar veel minder bekend. Dat is op zijn minst vreemd, aangezien Lynch zelf altijd heeft benadrukt dat hij zichzelf vóór alles ziet als beeldend kunstenaar.

Een beeldend kunstenaar die tijdens zijn studie aan de kunstacademie toevallig in aanraking kwam met het medium film, waarmee de basis gelegd werd voor zijn carrière als filmregisseur.

Naast zijn werk als regisseur is Lynch altijd actief gebleven als beeldend kunstenaar en heeft hij in de afgelopen decennia een grenzeloos oeuvre gecreëerd van onder andere schilderijen, tekeningen, litho’s, foto’s, lampsculpturen, muziek en installaties.

Naast zijn werk als regisseur is Lynch altijd actief gebleven als beeldend kunstenaar en heeft hij in de afgelopen decennia een grenzeloos oeuvre gecreëerd van onder andere schilderijen, tekeningen, litho’s, foto’s, lampsculpturen, muziek en installaties.

Een oeuvre dat tot nu toe nog maar zelden is belicht en in musea werd getoond. Met ruim 500 werken brengt het Bonnefantenmuseum niet alleen de eerste Nederlandse museumpresentatie van Lynch’ beeldend oeuvre, maar ook de grootste overzichtstentoonstelling ooit.

David Lynch: Someone is in my House

30.11.2018 – 28.04.2019

David Lynch, beeldend kunstenaar

Anders dan het werk van Lynch (1946, Missoula, Montana, VS), vol duister geweld en seksualiteit, doet vermoeden, is de kindertijd van de kunstenaar en filmmaker gelukkig en liefdevol.

Anders dan het werk van Lynch (1946, Missoula, Montana, VS), vol duister geweld en seksualiteit, doet vermoeden, is de kindertijd van de kunstenaar en filmmaker gelukkig en liefdevol.

Lynch groeit op met reislustige ouders en leidt op jonge leeftijd een nomadenbestaan, een voor hem idyllische en veilige omgeving. Van jongs af aan aangemoedigd om zich creatief te ontplooien – kleurboeken waren uit den boze, eigen verbeelding gebruiken was het credo – komt hij uiteindelijk op de Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia terecht om schilderkunst te studeren.

Hier ontwikkelt Lynch zijn artistieke vocabulaire en thema’s die blijvend aanwezig zullen zijn in zijn werk. En hier ligt de voedingsbodem voor zijn eerste mixed-media installatie met stop-motion film Six Men Getting Sick (Six Times) (1967), die een opmaat vormde naar zijn eerste speelfilm, Eraserhead (1977). De rest is (film)geschiedenis en inmiddels zijn Lynch’ films moderne klassiekers.

Hier ontwikkelt Lynch zijn artistieke vocabulaire en thema’s die blijvend aanwezig zullen zijn in zijn werk. En hier ligt de voedingsbodem voor zijn eerste mixed-media installatie met stop-motion film Six Men Getting Sick (Six Times) (1967), die een opmaat vormde naar zijn eerste speelfilm, Eraserhead (1977). De rest is (film)geschiedenis en inmiddels zijn Lynch’ films moderne klassiekers.

Lynch’ kunstenaarschap loopt als een rode draad door zijn leven en films. Hij is gedurende zijn vijftigjarige carrière altijd blijven tekenen en schilderen, ook als er vanwege zijn werk als filmregisseur weinig tijd was om in het atelier door te brengen.

“I miss painting when I’m not painting”, zegt Lynch zelf in de recente biografie Room to Dream. * David Lynch en Kristine McKenna. Room to Dream. Edinburgh, Canongate Books, 2018, p. 301

In samenwerking met David Lynch toont het Bonnefanten een indrukwekkend artistiek overzicht van het veelzijdige kunstenaarschap van Lynch.

In samenwerking met David Lynch toont het Bonnefanten een indrukwekkend artistiek overzicht van het veelzijdige kunstenaarschap van Lynch.

De tentoonstelling omvat schilderijen, foto’s, tekeningen, litho’s en aquarellen uit de jaren 60 tot heden, unieke tekeningen op luciferboekjes uit de jaren 70, schetsboektekeningen uit de jaren 60/70/80, zwart-wit foto’s uit verschillende periodes, waaronder de befaamde Snow Men-fotoserie (1993), cartoons uit de serie The Angriest Dog in the World (1982-1993), audiowerken én een aantal kortfilms uit 1968-2015.

Voor het eerst sinds het ontstaan in 1967, zal ook het allesbepalende academiewerk Six Men Getting Sick (Six Times) in een museumtentoonstelling te zien zijn.

Voor het eerst sinds het ontstaan in 1967, zal ook het allesbepalende academiewerk Six Men Getting Sick (Six Times) in een museumtentoonstelling te zien zijn.

Publicatie

Bij de tentoonstelling verschijnt een rijk geïllustreerde monografie met tekstbijdragen van curator Stijn Huijts (artistiek directeur Bonnefantenmuseum), Kristine McKenna (journalist en curator, Verenigde Staten), Petra Giloy-Hirtz (schrijver en curator, Duitsland) en Michael Chabon (schrijver, Verenigde Staten). De publicatie is verkrijgbaar in het Nederlands, Engels en Frans en wordt uitgegeven door Uitgeverij Hannibal in samenwerking met Prestel.

Bij de tentoonstelling verschijnt een rijk geïllustreerde monografie met tekstbijdragen van curator Stijn Huijts (artistiek directeur Bonnefantenmuseum), Kristine McKenna (journalist en curator, Verenigde Staten), Petra Giloy-Hirtz (schrijver en curator, Duitsland) en Michael Chabon (schrijver, Verenigde Staten). De publicatie is verkrijgbaar in het Nederlands, Engels en Frans en wordt uitgegeven door Uitgeverij Hannibal in samenwerking met Prestel.

Tentoonstellingsteaser

In aanloop naar zijn omvangrijke retrospectief Someone is in my House, maakte Lynch speciaal voor het Bonnefanten een unieke tentoonstellingsteaser. In deze typisch Lynchiaanse kortfilm, met in de hoofdrol naast Lynch zelf de ‘White Monkey’ – een personage dat eerder opdook in Lynch’ Weird daily weather report – nodigt hij de kijker uit om naar het Bonnefanten te komen.

In aanloop naar zijn omvangrijke retrospectief Someone is in my House, maakte Lynch speciaal voor het Bonnefanten een unieke tentoonstellingsteaser. In deze typisch Lynchiaanse kortfilm, met in de hoofdrol naast Lynch zelf de ‘White Monkey’ – een personage dat eerder opdook in Lynch’ Weird daily weather report – nodigt hij de kijker uit om naar het Bonnefanten te komen.

Flankerend programma

Parallel aan de tentoonstelling is er in samenwerking met Lumière Cinema in Maastricht een compleet filmretrospectief gewijd aan de films en het leven van David Lynch met filmvertoningen, documentaires en lezingen over de filmmaker.

Parallel aan de tentoonstelling is er in samenwerking met Lumière Cinema in Maastricht een compleet filmretrospectief gewijd aan de films en het leven van David Lynch met filmvertoningen, documentaires en lezingen over de filmmaker.

Daarnaast brengt EYE filmmuseum drie digitaal gerestaureerde films opnieuw uit in de filmtheaters in heel het land. Voor meer informatie: https://www.eyefilm.nl/themas/gerestaureerde-david-lynch-klassiekers

De philharmonie zuidnederland werkte met de Poolse componist Marek Zebrowski aan een compositie en uitvoering van Music for David, een strijkkwartet dat Zebrowski in 2015 componeerde als een hommage aan Lynch, die op zijn beurt de korte animatie film Pożar (Fire) maakte bij Zebrowski’s compositie. Het muziekstuk zal een aantal keren live (op zaal) bij de film ten gehore worden gebracht.

De philharmonie zuidnederland werkte met de Poolse componist Marek Zebrowski aan een compositie en uitvoering van Music for David, een strijkkwartet dat Zebrowski in 2015 componeerde als een hommage aan Lynch, die op zijn beurt de korte animatie film Pożar (Fire) maakte bij Zebrowski’s compositie. Het muziekstuk zal een aantal keren live (op zaal) bij de film ten gehore worden gebracht.

# meer informatie op website Bonnefantenmuseum

# Expositie & publicatie

David Lynch: Someone is in my House

30.11.2018 – 28.04.2019

• photos: jef van kempen

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #Archive A-Z Sound Poetry, *Concrete + Visual Poetry K-O, - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive K-L, Art & Literature News, AUDIO, CINEMA, RADIO & TV, David Lynch, Exhibition Archive, FDM Art Gallery, Jef van Kempen Photos & Drawings, Museum of Literary Treasures, Photography, Tales of Mystery & Imagination, THEATRE

Undeterred by the embarrassing success of his ridiculous four-volume verse epic The Limerickiad, award-winning cartoonist Martin Rowson continues to lower the tone with a series of metrical rants and cautionary tales about contemporary political and literary life.

Accompanied by the ghosts of Chesterton, Shelley, Burns and Browning, Rowson casts his gaze across the satirical spectrum from governments, gammon-faced racists, class war, nationalism and the harsh realities of child rearing to the world of literary festivals, international book fairs, best-sellers, book-launches, holiday reading lists, bottom lines, liggers, bloggers, blaggers, book-signings and book-burnings.

Accompanied by the ghosts of Chesterton, Shelley, Burns and Browning, Rowson casts his gaze across the satirical spectrum from governments, gammon-faced racists, class war, nationalism and the harsh realities of child rearing to the world of literary festivals, international book fairs, best-sellers, book-launches, holiday reading lists, bottom lines, liggers, bloggers, blaggers, book-signings and book-burnings.

Martin Rowson is an award-winning cartoonist whose work appears regularly in The Guardian, The Independent on Sunday, The Daily Mirror, The Morning Star and many other publications.

His books include graphic adaptations of The Waste Land, Tristram Shandy and Gulliver’s Travels. Among his other books are Snatches, The Dog Allusion, Fuck, Stuff (long-listed for the Samuel Johnson Prize) and four volumes of The Limerickiad. His most recent book is The Communist Manifesto: A Graphic Novel.

Martin Rowson

Pastrami Faced Racist

Published by Smokestack Books

Release date: 01 Nov. 2018

Language: English

Paperback

84 pages

ISBN-10: 1999827686

ISBN-13: 978-1999827687

£8.99

# new books

Martin Rowson

Pastrami Faced Racist

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Book Stories, Archive Q-R, Archive Q-R, Art & Literature News, Illustrators, Illustration

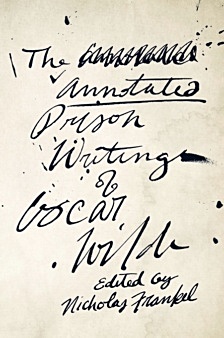

“And I? May I say nothing, my lord?” With these words, Oscar Wilde’s courtroom trials came to a close. The lord in question, High Court justice Sir Alfred Wills, sent Wilde to the cells, sentenced to two years in prison with hard labor for the crime of “gross indecency” with other men.

As cries of “shame” emanated from the gallery, the convicted aesthete was roundly silenced.

As cries of “shame” emanated from the gallery, the convicted aesthete was roundly silenced.

But he did not remain so. Behind bars and in the period immediately after his release, Wilde wrote two of his most powerful works—the long autobiographical letter De Profundis and an expansive best-selling poem, The Ballad of Reading Gaol.

In The Annotated Prison Writings of Oscar Wilde, Nicholas Frankel collects these and other prison writings, accompanied by historical illustrations and his rich facing-page annotations. As Frankel shows, Wilde experienced prison conditions designed to break even the toughest spirit, and yet his writings from this period display an imaginative and verbal brilliance left largely intact.

Wilde also remained politically steadfast, determined that his writings should inspire improvements to Victorian England’s grotesque regimes of punishment. But while his reformist impulse spoke to his moment, Wilde also wrote for eternity.

At once a savage indictment of the society that jailed him and a moving testimony to private sufferings, Wilde’s prison writings—illuminated by Frankel’s extensive notes—reveal a very different man from the famous dandy and aesthete who shocked and amused the English-speaking world.

Nicholas Frankel is Professor of English at Virginia Commonwealth University.

“Frankel provides a valuable service in comprehensively editing these works for a fresh generation of readers.” — Joseph Bristow, University of California, Los Angeles

The Annotated Prison Writings of Oscar Wilde

Oscar Wilde

Edited by Nicholas Frankel

Harvard University Press

Paperback

408 pages

Publication: May 2018

ISBN 9780674984387

€17.00

# more books

The Annotated Prison Writings of Oscar Wilde

-Clemency Petition to the Home Secretary, 2 July 1896

-De Profundis

-Letter to the Daily Chronicle, 27 May 1897

-The Ballad of Reading Gaol

-Letter to the Daily Chronicle, 23 March 1898

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Book Stories, Archive W-X, Archive W-X, Art & Literature News, CRIME & PUNISHMENT, REPRESSION OF WRITERS, JOURNALISTS & ARTISTS, Wilde, Oscar, Wilde, Oscar

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature