Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

Jacob & Wilhelm Grimm ♦ Rumpelstiltskin ♦ There was once a miller who was poor, but he had one beautiful daughter. It happened one day that he came to speak with the king, and, to give himself consequence, he told him that he had a daughter who could spin gold out of straw. The king said to the miller, “That is an art that pleases me well; if thy daughter is as clever as you say, bring her to my castle to-morrow, that I may put her to the proof.”

Jacob & Wilhelm Grimm ♦ Rumpelstiltskin ♦ There was once a miller who was poor, but he had one beautiful daughter. It happened one day that he came to speak with the king, and, to give himself consequence, he told him that he had a daughter who could spin gold out of straw. The king said to the miller, “That is an art that pleases me well; if thy daughter is as clever as you say, bring her to my castle to-morrow, that I may put her to the proof.”

When the girl was brought to him, he led her into a room that was quite full of straw, and gave her a wheel and spindle, and said, “Now set to work, and if by the early morning thou hast not spun this straw to gold thou shalt die.” And he shut the door himself, and left her there alone. And so the poor miller’s daughter was left there sitting, and could not think what to do for her life: she had no notion how to set to work to spin gold from straw, and her distress grew so great that she began to weep. Then all at once the door opened, and in came a little man, who said, “Good evening, miller’s daughter; why are you crying?”

“Oh!” answered the girl, “I have got to spin gold out of straw, and I don’t understand the business.” Then the little man said, “What will you give me if I spin it for you?” – “My necklace,” said the girl. The little man took the necklace, seated himself before the wheel, and whirr, whirr, whirr! three times round and the bobbin was full; then he took up another, and whirr, whirr, whirr! three times round, and that was full; and so he went on till the morning, when all the straw had been spun, and all the bobbins were full of gold.

“Oh!” answered the girl, “I have got to spin gold out of straw, and I don’t understand the business.” Then the little man said, “What will you give me if I spin it for you?” – “My necklace,” said the girl. The little man took the necklace, seated himself before the wheel, and whirr, whirr, whirr! three times round and the bobbin was full; then he took up another, and whirr, whirr, whirr! three times round, and that was full; and so he went on till the morning, when all the straw had been spun, and all the bobbins were full of gold.

At sunrise came the king, and when he saw the gold he was astonished and very much rejoiced, for he was very avaricious. He had the miller’s daughter taken into another room filled with straw, much bigger than the last, and told her that as she valued her life she must spin it all in one night. The girl did not know what to do, so she began to cry, and then the door opened, and the little man appeared and said, “What will you give me if I spin all this straw into gold?” – “The ring from my finger,” answered the girl. So the little man took the ring, and began again to send the wheel whirring round, and by the next morning all the straw was spun into glistening gold. The king was rejoiced beyond measure at the sight, but as he could never have enough of gold, he had the miller’s daughter taken into a still larger room full of straw, and said, “This, too, must be spun in one night, and if you accomplish it you shall be my wife.” For he thought, “Although she is but a miller’s daughter, I am not likely to find any one richer in the whole world.” As soon as the girl was left alone, the little man appeared for the third time and said, “What will you give me if I spin the straw for you this time?” – “I have nothing left to give,” answered the girl. “Then you must promise me the first child you have after you are queen,” said the little man. “But who knows whether that will happen?” thought the girl; but as she did not know what else to do in her necessity, she promised the little man what he desired, upon which he began to spin, until all the straw was gold. And when in the morning the king came and found all done according to his wish, he caused the wedding to be held at once, and the miller’s pretty daughter became a queen.

In a year’s time she brought a fine child into the world, and thought no more of the little man; but one day he came suddenly into her room, and said, “Now give me what you promised me.” The queen was terrified greatly, and offered the little man all the riches of the kingdom if he would only leave the child; but the little man said, “No, I would rather have something living than all the treasures of the world.” Then the queen began to lament and to weep, so that the little man had pity upon her. “I will give you three days,” said he, “and if at the end of that time you cannot tell my name, you must give up the child to me.”

In a year’s time she brought a fine child into the world, and thought no more of the little man; but one day he came suddenly into her room, and said, “Now give me what you promised me.” The queen was terrified greatly, and offered the little man all the riches of the kingdom if he would only leave the child; but the little man said, “No, I would rather have something living than all the treasures of the world.” Then the queen began to lament and to weep, so that the little man had pity upon her. “I will give you three days,” said he, “and if at the end of that time you cannot tell my name, you must give up the child to me.”

Then the queen spent the whole night in thinking over all the names that she had ever heard, and sent a messenger through the land to ask far and wide for all the names that could be found. And when the little man came next day, (beginning with Caspar, Melchior, Balthazar) she repeated all she knew, and went through the whole list, but after each the little man said, “That is not my name.” The second day the queen sent to inquire of all the neighbours what the servants were called, and told the little man all the most unusual and singular names, saying, “Perhaps you are called Roast-ribs, or Sheepshanks, or Spindleshanks?” But he answered nothing but “That is not my name.” The third day the messenger came back again, and said, “I have not been able to find one single new name; but as I passed through the woods I came to a high hill, and near it was a little house, and before the house burned a fire, and round the fire danced a comical little man, and he hopped on one leg and cried,

“To-day do I bake, to-morrow I brew,

“To-day do I bake, to-morrow I brew,

The day after that the queen’s child comes in;

And oh! I am glad that nobody knew

That the name I am called is Rumpelstiltskin!”

You cannot think how pleased the queen was to hear that name, and soon afterwards, when the little man walked in and said, “Now, Mrs Queen, what is my name?” she said at first, “Are you called Jack?” – “No,” answered he. “Are you called Harry?” she asked again. “No,” answered he. And then she said, “Then perhaps your name is Rumpelstiltskin?”

“The Devil told you that! the Devil told you that!” cried the little man, and in his anger he stamped with his right foot so hard that it went into the ground above his knee; then he seized his left foot with both his hands in such a fury that he split in two, and there was an end of him.

THE END

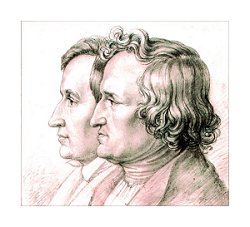

Jacob Grimm (1785-1863) & Wilhelm Grimm (1786-1859). This Brothers Grimm version of the story has been translated in 1844 into English by Margarate Hunt. KHM1 055: Kinder- und Hausmärchen (Children’s and Household Tales)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Grimm, Grimm, Jacob & Wilhelm

Jacob & Wilhelm Grimm ♦ The Girl Without Hands or The Armless Maiden ♦ A certain miller had little by little fallen into poverty, and had nothing left but his mill and a large apple-tree behind it. Once when he had gone into the forest to fetch wood, an old man stepped up to him whom he had never seen before, and said, “Why dost thou plague thyself with cutting wood, I will make thee rich, if thou wilt promise me what is standing behind thy mill?” – “What can that be but my apple-tree?” thought the miller, and said, “Yes,” and gave a written promise to the stranger. He, however, laughed mockingly and said, “When three years have passed, I will come and carry away what belongs to me,” and then he went. When the miller got home, his wife came to meet him and said, “Tell me, miller, from whence comes this sudden wealth into our house? All at once every box and chest was filled; no one brought it in, and I know not how it happened.” He answered, “It comes from a stranger who met me in the forest, and promised me great treasure. I, in return, have promised him what stands behind the mill; we can very well give him the big apple-tree for it.” – “Ah, husband,” said the terrified wife, “that must have been the Devil! He did not mean the apple-tree, but our daughter, who was standing behind the mill sweeping the yard.”

Jacob & Wilhelm Grimm ♦ The Girl Without Hands or The Armless Maiden ♦ A certain miller had little by little fallen into poverty, and had nothing left but his mill and a large apple-tree behind it. Once when he had gone into the forest to fetch wood, an old man stepped up to him whom he had never seen before, and said, “Why dost thou plague thyself with cutting wood, I will make thee rich, if thou wilt promise me what is standing behind thy mill?” – “What can that be but my apple-tree?” thought the miller, and said, “Yes,” and gave a written promise to the stranger. He, however, laughed mockingly and said, “When three years have passed, I will come and carry away what belongs to me,” and then he went. When the miller got home, his wife came to meet him and said, “Tell me, miller, from whence comes this sudden wealth into our house? All at once every box and chest was filled; no one brought it in, and I know not how it happened.” He answered, “It comes from a stranger who met me in the forest, and promised me great treasure. I, in return, have promised him what stands behind the mill; we can very well give him the big apple-tree for it.” – “Ah, husband,” said the terrified wife, “that must have been the Devil! He did not mean the apple-tree, but our daughter, who was standing behind the mill sweeping the yard.”

The miller’s daughter was a beautiful, pious girl, and lived through the three years in the fear of God and without sin. When therefore the time was over, and the day came when the Evil-one was to fetch her, she washed herself clean, and made a circle round herself with chalk. The devil appeared quite early, but he could not come near to her. Angrily, he said to the miller, “Take all water away from her, that she may no longer be able to wash herself, for otherwise I have no power over her.” The miller was afraid, and did so. The next morning the devil came again, but she had wept on her hands, and they were quite clean. Again he could not get near her, and furiously said to the miller, “Cut her hands off, or else I cannot get the better of her.” The miller was shocked and answered, “How could I cut off my own child’s hands?” Then the Evil-one threatened him and said, “If thou dost not do it thou art mine, and I will take thee thyself.” The father became alarmed, and promised to obey him. So he went to the girl and said, “My child, if I do not cut off both thine hands, the devil will carry me away, and in my terror I have promised to do it. Help me in my need, and forgive me the harm I do thee.” She replied, “Dear father, do with me what you will, I am your child.” Thereupon she laid down both her hands, and let them be cut off. The devil came for the third time, but she had wept so long and so much on the stumps, that after all they were quite clean. Then he had to give in, and had lost all right over her.

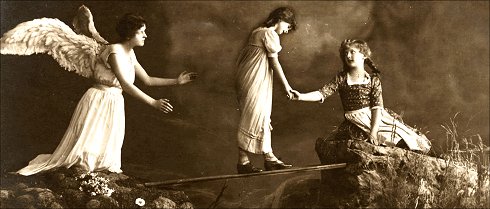

The miller said to her, “I have by means of thee received such great wealth that I will keep thee most delicately as long as thou livest.” But she replied, “Here I cannot stay, I will go forth, compassionate people will give me as much as I require.” Thereupon she caused her maimed arms to be bound to her back, and by sunrise she set out on her way, and walked the whole day until night fell. Then she came to a royal garden, and by the shimmering of the moon she saw that trees covered with beautiful fruits grew in it, but she could not enter, for there was much water round about it. And as she had walked the whole day and not eaten one mouthful, and hunger tormented her, she thought, “Ah, if I were but inside, that I might eat of the fruit, else must I die of hunger!” Then she knelt down, called on God the Lord, and prayed. And suddenly an angel came towards her, who made a dam in the water, so that the moat became dry and she could walk through it. And now she went into the garden and the angel went with her. She saw a tree covered with beautiful pears, but they were all counted. Then she went to them, and to still her hunger, ate one with her mouth from the tree, but no more. The gardener was watching; but as the angel was standing by, he was afraid and thought the maiden was a spirit, and was silent, neither did he dare to cry out, or to speak to the spirit. When she had eaten the pear, she was satisfied, and went and concealed herself among the bushes. The King to whom the garden belonged, came down to it next morning, and counted, and saw that one of the pears was missing, and asked the gardener what had become of it, as it was not lying beneath the tree, but was gone. Then answered the gardener, “Last night, a spirit came in, who had no hands, and ate off one of the pears with its mouth.” The King said, “How did the spirit get over the water, and where did it go after it had eaten the pear?” The gardener answered, “Some one came in a snow-white garment from heaven who made a dam, and kept back the water, that the spirit might walk through the moat. And as it must have been an angel, I was afraid, and asked no questions, and did not cry out. When the spirit had eaten the pear, it went back again.” The King said, “If it be as thou sayest, I will watch with thee to-night.”

The miller said to her, “I have by means of thee received such great wealth that I will keep thee most delicately as long as thou livest.” But she replied, “Here I cannot stay, I will go forth, compassionate people will give me as much as I require.” Thereupon she caused her maimed arms to be bound to her back, and by sunrise she set out on her way, and walked the whole day until night fell. Then she came to a royal garden, and by the shimmering of the moon she saw that trees covered with beautiful fruits grew in it, but she could not enter, for there was much water round about it. And as she had walked the whole day and not eaten one mouthful, and hunger tormented her, she thought, “Ah, if I were but inside, that I might eat of the fruit, else must I die of hunger!” Then she knelt down, called on God the Lord, and prayed. And suddenly an angel came towards her, who made a dam in the water, so that the moat became dry and she could walk through it. And now she went into the garden and the angel went with her. She saw a tree covered with beautiful pears, but they were all counted. Then she went to them, and to still her hunger, ate one with her mouth from the tree, but no more. The gardener was watching; but as the angel was standing by, he was afraid and thought the maiden was a spirit, and was silent, neither did he dare to cry out, or to speak to the spirit. When she had eaten the pear, she was satisfied, and went and concealed herself among the bushes. The King to whom the garden belonged, came down to it next morning, and counted, and saw that one of the pears was missing, and asked the gardener what had become of it, as it was not lying beneath the tree, but was gone. Then answered the gardener, “Last night, a spirit came in, who had no hands, and ate off one of the pears with its mouth.” The King said, “How did the spirit get over the water, and where did it go after it had eaten the pear?” The gardener answered, “Some one came in a snow-white garment from heaven who made a dam, and kept back the water, that the spirit might walk through the moat. And as it must have been an angel, I was afraid, and asked no questions, and did not cry out. When the spirit had eaten the pear, it went back again.” The King said, “If it be as thou sayest, I will watch with thee to-night.”

When it grew dark the King came into the garden and brought a priest with him, who was to speak to the spirit. All three seated themselves beneath the tree and watched. At midnight the maiden came creeping out of the thicket, went to the tree, and again ate one pear off it with her mouth, and beside her stood the angel in white garments3. Then the priest went out to them and said, “Comest thou from heaven or from earth? Art thou a spirit, or a human being?” She replied, “I am no spirit, but an unhappy mortal deserted by all but God.” The King said, “If thou art forsaken by all the world, yet will I not forsake thee.” He took her with him into his royal palace, and as she was so beautiful and good, he loved her with all his heart, had silver hands made for her, and took her to wife.

After a year the King had to take the field4, so he commended his young Queen to the care of his mother and said, “If she is brought to bed take care of her, nurse her well, and tell me of it at once in a letter.” Then she gave birth to a fine boy. So the old mother made haste to write and announce the joyful news to him. But the messenger rested by a brook on the way, and as he was fatigued by the great distance, he fell asleep. Then came the Devil, who was always seeking to injure the good Queen, and exchanged the letter for another, in which was written that the Queen had brought a monster into the world. When the King read the letter he was shocked and much troubled, but he wrote in answer that they were to take great care of the Queen and nurse her well until his arrival. The messenger went back with the letter, but rested at the same place and again fell asleep. Then came the Devil once more, and put a different letter in his pocket, in which it was written that they were to put the Queen and her child to death. The old mother was terribly shocked when she received the letter, and could not believe it. She wrote back again to the King, but received no other answer, because each time the Devil substituted a false letter, and in the last letter it was also written that she was to preserve the Queen’s tongue and eyes as a token that she had obeyed.

After a year the King had to take the field4, so he commended his young Queen to the care of his mother and said, “If she is brought to bed take care of her, nurse her well, and tell me of it at once in a letter.” Then she gave birth to a fine boy. So the old mother made haste to write and announce the joyful news to him. But the messenger rested by a brook on the way, and as he was fatigued by the great distance, he fell asleep. Then came the Devil, who was always seeking to injure the good Queen, and exchanged the letter for another, in which was written that the Queen had brought a monster into the world. When the King read the letter he was shocked and much troubled, but he wrote in answer that they were to take great care of the Queen and nurse her well until his arrival. The messenger went back with the letter, but rested at the same place and again fell asleep. Then came the Devil once more, and put a different letter in his pocket, in which it was written that they were to put the Queen and her child to death. The old mother was terribly shocked when she received the letter, and could not believe it. She wrote back again to the King, but received no other answer, because each time the Devil substituted a false letter, and in the last letter it was also written that she was to preserve the Queen’s tongue and eyes as a token that she had obeyed.

But the old mother wept to think such innocent blood was to be shed, and had a hind brought by night and cut out her tongue and eyes, and kept them. Then said she to the Queen, “I cannot have thee killed as the King commands, but here thou mayst stay no longer. Go forth into the wide world with thy child, and never come here again.” The poor woman tied her child on her back, and went away with eyes full of tears. She came into a great wild forest, and then she fell on her knees and prayed to God, and the angel of the Lord appeared to her and led her to a little house on which was a sign with the words, “Here all dwell free.” A snow-white maiden came out of the little house and said, ‘Welcome, Lady Queen,” and conducted her inside. Then they unbound the little boy from her back, and held him to her breast that he might feed, and laid him in a beautifully-made little bed. Then said the poor woman, “From whence knowest thou that I was a queen?” The white maiden answered, “I am an angel sent by God, to watch over thee and thy child.” The Queen stayed seven7 years in the little house, and was well cared for, and by God’s grace, because of her piety, her hands which had been cut off, grew once more.

At last the King came home again from the war, and his first wish was to see his wife and the child. Then his aged mother began to weep and said, “Thou wicked man, why didst thou write to me that I was to take those two innocent lives?” and she showed him the two letters which the Evil-one had forged, and then continued, “I did as thou badest me,” and she showed the tokens, the tongue and eyes. Then the King began to weep for his poor wife and his little son so much more bitterly than she was doing, that the aged mother had compassion on him and said, “Be at peace, she still lives; I secretly caused a hind to be killed, and took these tokens from it; but I bound the child to thy wife’s back and bade her go forth into the wide world, and made her promise never to come back here again, because thou wert so angry with her.” Then spoke the King, “I will go as far as the sky is blue, and will neither eat nor drink until I have found again my dear wife and my child, if in the meantime they have not been killed, or died of hunger.”

Thereupon the King travelled about for seven long years, and sought her in every cleft of the rocks and in every cave, but he found her not, and thought she had died of want. During the whole of this time he neither ate nor drank, but God supported him. At length he came into a great forest, and found therein the little house whose sign was, “Here all dwell free.” Then forth came the white maiden, took him by the hand, led him in, and said, “Welcome, Lord King,” and asked him from whence he came. He answered, “Soon shall I have travelled about for the space of seven years, and I seek my wife and her child, but cannot find them.” The angel offered him meat and drink, but he did not take anything, and only wished to rest a little. Then he lay down to sleep, and put a handkerchief over his face.

Thereupon the King travelled about for seven long years, and sought her in every cleft of the rocks and in every cave, but he found her not, and thought she had died of want. During the whole of this time he neither ate nor drank, but God supported him. At length he came into a great forest, and found therein the little house whose sign was, “Here all dwell free.” Then forth came the white maiden, took him by the hand, led him in, and said, “Welcome, Lord King,” and asked him from whence he came. He answered, “Soon shall I have travelled about for the space of seven years, and I seek my wife and her child, but cannot find them.” The angel offered him meat and drink, but he did not take anything, and only wished to rest a little. Then he lay down to sleep, and put a handkerchief over his face.

Thereupon the angel went into the chamber where the Queen sat with her son, whom she usually called “Sorrowful,” and said to her, “Go out with thy child, thy husband hath come.” So she went to the place where he lay, and the handkerchief fell from his face. Then said she, “Sorrowful, pick up thy father’s handkerchief, and cover his face again.” The child picked it up, and put it over his face again. The King in his sleep heard what passed, and had pleasure in letting the handkerchief fall once more. But the child grew impatient, and said, “Dear mother, how can I cover my father’s face when I have no father in this world? I have learnt to say the prayer, ‘Our Father, which art in Heaven,’ thou hast told me that my father was in Heaven, and was the good God, and how can I know a wild man like this? He is not my father.” When the King heard that, he got up, and asked who they were. Then said she, “I am thy wife, and that is thy son, Sorrowful.” And he saw her living hands, and said, “My wife had silver hands.” She answered, “The good God has caused my natural hands to grow again;” and the angel went into the inner room, and brought the silver hands, and showed them to him. Hereupon he knew for a certainty that it was his dear wife and his dear child, and he kissed them, and was glad, and said, “A heavy stone has fallen from off mine heart.” Then the angel of God gave them one meal with her, and after that they went home to the King’s aged mother. There were great rejoicings everywhere, and the King and Queen were married again, and lived contentedly to their happy end.

THE END

Jacob Grimm (1785-1863) & Wilhelm Grimm (1786-1859). This Brothers Grimm version of the story has been translated in 1844 into English by Margarate Hunt. KHM1 031: Kinder- und Hausmärchen (Children’s and Household Tales)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Grimm, Grimm, Jacob & Wilhelm

Jacob & Wilhelm Grimm: The story of the youth who went forth to learn what fear was ♦ A certain father had two sons, the elder of whom was smart and sensible, and could do everything, but the younger was stupid and could neither learn nor understand anything, and when people saw him they said, “There’s a fellow who will give his father some trouble!” When anything had to be done, it was always the elder who was forced to do it; but if his father bade him fetch anything when it was late, or in the night-time, and the way led through the churchyard, or any other dismal place, he answered “Oh, no, father, I’ll not go there, it makes me shudder!” for he was afraid. Or when stories were told by the fire at night which made the flesh creep, the listeners sometimes said “Oh, it makes us shudder!” The younger sat in a corner and listened with the rest of them, and could not imagine what they could mean. “They are always saying ‘it makes me shudder, it makes me shudder!’ It does not make me shudder,” thought he. “That, too, must be an art of which I understand nothing.”

Jacob & Wilhelm Grimm: The story of the youth who went forth to learn what fear was ♦ A certain father had two sons, the elder of whom was smart and sensible, and could do everything, but the younger was stupid and could neither learn nor understand anything, and when people saw him they said, “There’s a fellow who will give his father some trouble!” When anything had to be done, it was always the elder who was forced to do it; but if his father bade him fetch anything when it was late, or in the night-time, and the way led through the churchyard, or any other dismal place, he answered “Oh, no, father, I’ll not go there, it makes me shudder!” for he was afraid. Or when stories were told by the fire at night which made the flesh creep, the listeners sometimes said “Oh, it makes us shudder!” The younger sat in a corner and listened with the rest of them, and could not imagine what they could mean. “They are always saying ‘it makes me shudder, it makes me shudder!’ It does not make me shudder,” thought he. “That, too, must be an art of which I understand nothing.”

Now it came to pass that his father said to him one day “Hearken to me, thou fellow in the corner there, thou art growing tall and strong, and thou too must learn something by which thou canst earn thy living. Look how thy brother works, but thou dost not even earn thy salt.” – “Well, father,” he replied, “I am quite willing to learn something – indeed, if it could but be managed, I should like to learn how to shudder. I don’t understand that at all yet.” The elder brother smiled when he heard that, and thought to himself, “Good God, what a blockhead that brother of mine is! He will never be good for anything as long as he lives. He who wants to be a sickle must bend himself betimes.” The father sighed, and answered him “thou shalt soon learn what it is to shudder, but thou wilt not earn thy bread by that.”

Soon after this the sexton2 came to the house on a visit, and the father bewailed his trouble, and told him how his younger son was so backward in every respect that he knew nothing and learnt nothing. “Just think,” said he, “when I asked him how he was going to earn his bread, he actually wanted to learn to shudder.” – “If that be all,” replied the sexton, “he can learn that with me. Send him to me, and I will soon polish him.” The father was glad to do it, for he thought, “It will train the boy a little.” The sexton therefore took him into his house, and he had to ring the bell. After a day or two, the sexton awoke him at midnight, and bade him arise and go up into the church tower and ring the bell. “Thou shalt soon learn what shuddering is,” thought he, and secretly went there before him; and when the boy was at the top of the tower and turned round, and was just going to take hold of the bell rope, he saw a white figure standing on the stairs opposite the sounding hole. “Who is there?” cried he, but the figure made no reply, and did not move or stir. “Give an answer,” cried the boy, “or take thy self off, thou hast no business here at night.” The sexton, however, remained standing motionless that the boy might think he was a ghost. The boy cried a second time, “What do you want here? – speak if thou art an honest fellow, or I will throw thee down the steps!” The sexton thought, “he can’t intend to be as bad as his words,” uttered no sound and stood as if he were made of stone. Then the boy called to him for the third time, and as that was also to no purpose, he ran against him and pushed the ghost down the stairs, so that it fell down ten steps and remained lying there in a corner. Thereupon he rang the bell, went home, and without saying a word went to bed, and fell asleep. The sexton’s wife waited a long time for her husband, but he did not come back. At length she became uneasy, and wakened the boy, and asked, “Dost thou not know where my husband is? He climbed up the tower before thou didst.” – “No, I don’t know,” replied the boy, “but some one was standing by the sounding hole on the other side of the steps, and as he would neither give an answer nor go away, I took him for a scoundrel, and threw him downstairs, just go there and you will see if it was he. I should be sorry if it were.” The woman ran away and found her husband, who was lying moaning in the corner, and had broken his leg.

She carried him down, and then with loud screams she hastened to the boy’s father. “Your boy,” cried she, “has been the cause of a great misfortune! He has thrown my husband down the steps and made him break his leg. Take the good-for-nothing fellow away from our house.” The father was terrified, and ran thither and scolded the boy. “What wicked tricks are these?” said he, “the Devil must have put this into thy head.” – “Father,” he replied, “do listen to me. I am quite innocent. He was standing there by night like one who is intending to do some evil. I did not know who it was, and I entreated him three times either to speak or to go away.” – “Ah,” said the father, “I have nothing but unhappiness with you. Go out of my sight. I will see thee no more.” – “Yes, father, right willingly, wait only until it is day. Then will I go forth and learn how to shudder, and then I shall, at any rate, understand one art which will support me.” – “Learn what thou wilt,” spake the father, “it is all the same to me. Here are fifty thalers3 for thee. Take these and go into the wide world, and tell no one from whence thou comest, and who is thy father, for I have reason to be ashamed of thee.” – “Yes, father, it shall be as you will. If you desire nothing more than that, I can easily keep it in mind.”

She carried him down, and then with loud screams she hastened to the boy’s father. “Your boy,” cried she, “has been the cause of a great misfortune! He has thrown my husband down the steps and made him break his leg. Take the good-for-nothing fellow away from our house.” The father was terrified, and ran thither and scolded the boy. “What wicked tricks are these?” said he, “the Devil must have put this into thy head.” – “Father,” he replied, “do listen to me. I am quite innocent. He was standing there by night like one who is intending to do some evil. I did not know who it was, and I entreated him three times either to speak or to go away.” – “Ah,” said the father, “I have nothing but unhappiness with you. Go out of my sight. I will see thee no more.” – “Yes, father, right willingly, wait only until it is day. Then will I go forth and learn how to shudder, and then I shall, at any rate, understand one art which will support me.” – “Learn what thou wilt,” spake the father, “it is all the same to me. Here are fifty thalers3 for thee. Take these and go into the wide world, and tell no one from whence thou comest, and who is thy father, for I have reason to be ashamed of thee.” – “Yes, father, it shall be as you will. If you desire nothing more than that, I can easily keep it in mind.”

When day dawned, therefore, the boy put his fifty thalers into his pocket, and went forth on the great highway, and continually said to himself, “If I could but shudder! If I could but shudder!” Then a man approached who heard this conversation which the youth was holding with himself, and when they had walked a little farther to where they could see the gallows, the man said to him, “Look, there is the tree where seven1 men have married the ropemaker’s daughter, and are now learning how to fly. Sit down below it, and wait till night comes, and you will soon learn how to shudder.” – “If that is all that is wanted,” answered the youth, “it is easily done; but if I learn how to shudder as fast as that, thou shalt have my fifty thalers. Just come back to me early in the morning.” Then the youth went to the gallows, sat down below it, and waited till evening came. And as he was cold, he lighted himself a fire, but at midnight the wind blew so sharply that in spite of his fire, he could not get warm. And as the wind knocked the hanged men against each other, and they moved backwards and forwards, he thought to himself “Thou shiverest below by the fire, but how those up above must freeze and suffer!” And as he felt pity for them, he raised the ladder, and climbed up, unbound one of them after the other, and brought down all seven. Then he stirred the fire, blew it, and set them all round it to warm themselves. But they sat there and did not stir, and the fire caught their clothes. So he said, “Take care, or I will hang you up again.” The dead men, however, did not hear, but were quite silent, and let their rags go on burning. On this he grew angry, and said, “If you will not take care, I cannot help you, I will not be burnt with you,” and he hung them up again each in his turn. Then he sat down by his fire and fell asleep, and the next morning the man came to him and wanted to have the fifty thalers, and said, “Well, dost thou know how to shudder?” – “No,” answered he, “how was I to get to know? Those fellows up there did not open their mouths, and were so stupid that they let the few old rags which they had on their bodies get burnt.” Then the man saw that he would not get the fifty thalers that day, and went away saying, “One of this kind has never come my way before.”

The youth likewise went his way, and once more began to mutter to himself, “Ah, if I could but shudder! Ah, if I could but shudder!” A waggoner who was striding behind him heard that and asked, “Who are you?” – “I don’t know,” answered the youth. Then the waggoner asked, “From whence comest thou?” – “I know not.” – “Who is thy father?” – “That I may not tell thee.” – “What is it that thou art always muttering between thy teeth.” – “Ah,” replied the youth, “I do so wish I could shudder, but no one can teach me how to do it.” – “Give up thy foolish chatter,” said the waggoner. “Come, go with me, I will see about a place for thee.” The youth went with the waggoner, and in the evening they arrived at an inn where they wished to pass the night. Then at the entrance of the room the youth again said quite loudly, “If I could but shudder! If I could but shudder!” The host who heard this, laughed and said, “If that is your desire, there ought to be a good opportunity for you here.” – “Ah, be silent,” said the hostess, “so many inquisitive persons have already lost their lives, it would be a pity and a shame if such beautiful eyes as these should never see the daylight again.” But the youth said, “However difficult it may be, I will learn it and for this purpose indeed have I journeyed forth.” He let the host have no rest, until the latter told him, that not far from thence stood a haunted castle where any one could very easily learn what shuddering was, if he would but watch in it for three nights. The King had promised that he who would venture should have his daughter to wife, and she was the most beautiful maiden the sun shone on. Great treasures likewise lay in the castle, which were guarded by evil spirits, and these treasures would then be freed, and would make a poor man rich enough. Already many men had gone into the castle, but as yet none had come out again. Then the youth went next morning to the King and said if he were allowed he would watch three nights in the haunted castle. The King looked at him, and as the youth pleased him, he said, “Thou mayest ask for three things to take into the castle with thee, but they must be things without life.” Then he answered, “Then I ask for a fire, a turning lathe, and a cutting-board with the knife.”

The King had these things carried into the castle for him during the day. When night was drawing near, the youth went up and made himself a bright fire in one of the rooms, placed the cutting-board and knife beside it, and seated himself by the turning-lathe. “Ah, if I could but shudder!” said he, “but I shall not learn it here either.” Towards midnight he was about to poke his fire, and as he was blowing it, something cried suddenly from one corner, “Au, miau! how cold we are!” – “You simpletons!” cried he, “what are you crying about? If you are cold, come and take a seat by the fire and warm yourselves.” And when he had said that, two great black cats came with one tremendous leap and sat down on each side of him, and looked savagely at him with their fiery eyes. After a short time, when they had warmed themselves, they said, “Comrade, shall we have a game at cards?” – “Why not?” he replied, “but just show me your paws.” Then they stretched out their claws. “Oh,” said he, “what long nails you have! Wait, I must first cut them for you.” Thereupon he seized them by the throats, put them on the cutting-board and screwed their feet fast. “I have looked at your fingers,” said he, “and my fancy for card-playing has gone,” and he struck them dead and threw them out into the water. But when he had made away with these two, and was about to sit down again by his fire, out from every hole and corner came black cats and black dogs with red-hot chains, and more and more of them came until he could no longer stir, and they yelled horribly, and got on his fire, pulled it to pieces, and tried to put it out. He watched them for a while quietly, but at last when they were going too far, he seized his cutting-knife, and cried, “Away with ye, vermin,” and began to cut them down. Part of them ran away, the others he killed, and threw out into the fish-pond. When he came back he fanned the embers of his fire again and warmed himself. And as he thus sat, his eyes would keep open no longer, and he felt a desire to sleep. Then he looked round and saw a great bed in the corner. “That is the very thing for me,” said he, and got into it. When he was just going to shut his eyes, however, the bed began to move of its own accord, and went over the whole of the castle. “That’s right,” said he, “but go faster.” Then the bed rolled on as if six horses were harnessed to it, up and down, over thresholds and steps, but suddenly hop, hop, it turned over upside down, and lay on him like a mountain.

The King had these things carried into the castle for him during the day. When night was drawing near, the youth went up and made himself a bright fire in one of the rooms, placed the cutting-board and knife beside it, and seated himself by the turning-lathe. “Ah, if I could but shudder!” said he, “but I shall not learn it here either.” Towards midnight he was about to poke his fire, and as he was blowing it, something cried suddenly from one corner, “Au, miau! how cold we are!” – “You simpletons!” cried he, “what are you crying about? If you are cold, come and take a seat by the fire and warm yourselves.” And when he had said that, two great black cats came with one tremendous leap and sat down on each side of him, and looked savagely at him with their fiery eyes. After a short time, when they had warmed themselves, they said, “Comrade, shall we have a game at cards?” – “Why not?” he replied, “but just show me your paws.” Then they stretched out their claws. “Oh,” said he, “what long nails you have! Wait, I must first cut them for you.” Thereupon he seized them by the throats, put them on the cutting-board and screwed their feet fast. “I have looked at your fingers,” said he, “and my fancy for card-playing has gone,” and he struck them dead and threw them out into the water. But when he had made away with these two, and was about to sit down again by his fire, out from every hole and corner came black cats and black dogs with red-hot chains, and more and more of them came until he could no longer stir, and they yelled horribly, and got on his fire, pulled it to pieces, and tried to put it out. He watched them for a while quietly, but at last when they were going too far, he seized his cutting-knife, and cried, “Away with ye, vermin,” and began to cut them down. Part of them ran away, the others he killed, and threw out into the fish-pond. When he came back he fanned the embers of his fire again and warmed himself. And as he thus sat, his eyes would keep open no longer, and he felt a desire to sleep. Then he looked round and saw a great bed in the corner. “That is the very thing for me,” said he, and got into it. When he was just going to shut his eyes, however, the bed began to move of its own accord, and went over the whole of the castle. “That’s right,” said he, “but go faster.” Then the bed rolled on as if six horses were harnessed to it, up and down, over thresholds and steps, but suddenly hop, hop, it turned over upside down, and lay on him like a mountain.

But he threw quilts and pillows up in the air, got out and said, “Now any one who likes, may drive,” and lay down by his fire, and slept till it was day. In the morning the King came, and when he saw him lying there on the ground, he thought the evil spirits had killed him and he was dead. Then said he, “After all it is a pity, he is a handsome man.” The youth heard it, got up, and said, “It has not come to that yet.” Then the King was astonished, but very glad, and asked how he had fared. “Very well indeed,” answered he; “one night is past, the two others will get over likewise.” Then he went to the innkeeper, who opened his eyes very wide, and said, “I never expected to see thee alive again! Hast thou learnt how to shudder yet?” – “No,” said he, “it is all in vain. If some one would but tell me.”

But he threw quilts and pillows up in the air, got out and said, “Now any one who likes, may drive,” and lay down by his fire, and slept till it was day. In the morning the King came, and when he saw him lying there on the ground, he thought the evil spirits had killed him and he was dead. Then said he, “After all it is a pity, he is a handsome man.” The youth heard it, got up, and said, “It has not come to that yet.” Then the King was astonished, but very glad, and asked how he had fared. “Very well indeed,” answered he; “one night is past, the two others will get over likewise.” Then he went to the innkeeper, who opened his eyes very wide, and said, “I never expected to see thee alive again! Hast thou learnt how to shudder yet?” – “No,” said he, “it is all in vain. If some one would but tell me.”

The second night he again went up into the old castle, sat down by the fire, and once more began his old song, “If I could but shudder.” When midnight came, an uproar and noise of tumbling about was heard; at first it was low, but it grew louder and louder. Then it was quiet for awhile, and at length with a loud scream, half a man came down the chimney and fell before him. “Hollo!” cried he, “another half belongs to this. This is too little!” Then the uproar began again, there was a roaring and howling, and the other half fell down likewise. “Wait,” said he, “I will just blow up the fire a little for thee.” When he had done that and looked round again, the two pieces were joined together, and a frightful man was sitting in his place. “That is no part of our bargain,” said the youth, “the bench is mine.” The man wanted to push him away; the youth, however, would not allow that, but thrust him off with all his strength, and seated himself again in his own place. Then still more men fell down, one after the other; they brought nine dead men’s legs and two skulls, and set them up and played at nine-pins with them. The youth also wanted to play and said “Hark you, can I join you?” – “Yes, if thou hast any money.” – “Money enough,” replied he, “but your balls are not quite round.” Then he took the skulls and put them in the lathe and turned them till they were round. “There, now, they will roll better!” said he. “Hurrah! Now it goes merrily!” He played with them and lost some of his money, but when it struck twelve, everything vanished from his sight. He lay down and quietly fell asleep. Next morning the King came to inquire after him. “How has it fared with you this time?” asked he. “I have been playing at nine-pins,” he answered, “and have lost a couple of hellers1.” – “Hast thou not shuddered then?” – “Eh, what?” said he, “I have made merry. If I did but know what it was to shudder!”

The third night he sat down again on his bench and said quite sadly, “If I could but shudder.” When it grew late, six tall men came in and brought a coffin. Then said he, “Ha, ha, that is certainly my little cousin, who died only a few days ago,” and he beckoned with his finger, and cried “Come, little cousin, come.” They placed the coffin on the ground, but he went to it and took the lid off, and a dead man lay therein. He felt his face, but it was cold as ice. “Stop,” said he, “I will warm thee a little,” and went to the fire and warmed his hand and laid it on the dead man’s face, but he remained cold. Then he took him out, and sat down by the fire and laid him on his breast and rubbed his arms that the blood might circulate again. As this also did no good, he thought to himself “When two people lie in bed together, they warm each other,” and carried him to the bed, covered him over and lay down by him. After a short time the dead man became warm too, and began to move. Then said the youth, “See, little cousin, have I not warmed thee?” The dead man, however, got up and cried, “Now will I strangle thee.” – “What!” said he, “is that the way thou thankest me? Thou shalt at once go into thy coffin again,” and he took him up, threw him into it, and shut the lid. Then came the six men and carried him away again. “I cannot manage to shudder,” said he. “I shall never learn it here as long as I live.”

Then a man entered who was taller than all others, and looked terrible. He was old, however, and had a long white beard. “Thou wretch,” cried he, “thou shalt soon learn what it is to shudder, for thou shalt die.” – “Not so fast,” replied the youth. “If I am to die, I shall have to have a say in it.” – “I will soon seize thee,” said the fiend. “Softly, softly, do not talk so big. I am as strong as thou art, and perhaps even stronger.” – “We shall see,” said the old man. “If thou art stronger, I will let thee go – come, we will try.” Then he led him by dark passages to a smith’s forge, took an axe, and with one blow struck an anvil into the ground. “I can do better than that,” said the youth, and went to the other anvil. The old man placed himself near and wanted to look on, and his white beard hung down. Then the youth seized the axe, split the anvil with one blow, and struck the old man’s beard in with it. “Now I have thee,” said the youth. “Now it is thou who will have to die.” Then he seized an iron bar and beat the old man till he moaned and entreated him to stop, and he would give him great riches. The youth drew out the axe and let him go. The old man led him back into the castle, and in a cellar showed him three chests full of gold. “Of these,” said he, “one part is for the poor, the other for the king, the third is thine.” In the meantime it struck twelve, and the spirit disappeared; the youth, therefore, was left in darkness. “I shall still be able to find my way out,” said he, and felt about, found the way into the room, and slept there by his fire. Next morning the King came and said “Now thou must have learnt what shuddering is?” – “No,” he answered; “what can it be? My dead cousin was here, and a bearded man came and showed me a great deal of money down below, but no one told me what it was to shudder.” – “Then,” said the King, “thou hast delivered from the castle, and shalt marry my daughter.” – “That is all very well,” said he, “but still I do not know what it is to shudder.”

Then a man entered who was taller than all others, and looked terrible. He was old, however, and had a long white beard. “Thou wretch,” cried he, “thou shalt soon learn what it is to shudder, for thou shalt die.” – “Not so fast,” replied the youth. “If I am to die, I shall have to have a say in it.” – “I will soon seize thee,” said the fiend. “Softly, softly, do not talk so big. I am as strong as thou art, and perhaps even stronger.” – “We shall see,” said the old man. “If thou art stronger, I will let thee go – come, we will try.” Then he led him by dark passages to a smith’s forge, took an axe, and with one blow struck an anvil into the ground. “I can do better than that,” said the youth, and went to the other anvil. The old man placed himself near and wanted to look on, and his white beard hung down. Then the youth seized the axe, split the anvil with one blow, and struck the old man’s beard in with it. “Now I have thee,” said the youth. “Now it is thou who will have to die.” Then he seized an iron bar and beat the old man till he moaned and entreated him to stop, and he would give him great riches. The youth drew out the axe and let him go. The old man led him back into the castle, and in a cellar showed him three chests full of gold. “Of these,” said he, “one part is for the poor, the other for the king, the third is thine.” In the meantime it struck twelve, and the spirit disappeared; the youth, therefore, was left in darkness. “I shall still be able to find my way out,” said he, and felt about, found the way into the room, and slept there by his fire. Next morning the King came and said “Now thou must have learnt what shuddering is?” – “No,” he answered; “what can it be? My dead cousin was here, and a bearded man came and showed me a great deal of money down below, but no one told me what it was to shudder.” – “Then,” said the King, “thou hast delivered from the castle, and shalt marry my daughter.” – “That is all very well,” said he, “but still I do not know what it is to shudder.”

Then the gold was brought up and the wedding celebrated; but howsoever much the young king loved his wife, and however happy he was, he still said always “If I could but shudder – if I could but shudder.” And at last she was angry at this. Her waiting-maid said, “I will find a cure for him; he shall soon learn what it is to shudder.” She went out to the stream which flowed through the garden, and had a whole bucketful of gudgeons brought to her. At night when the young king was sleeping, his wife was to draw the clothes off him and empty the bucketful of cold water with the gudgeons in it over him, so that the little fishes would sprawl about him. When this was done, he woke up and cried “Oh, what makes me shudder so? What makes me shudder so, dear wife? Ah! now I know what it is to shudder!”

THE END

Jacob Grimm (1785-1863) & Wilhelm Grimm (1786-1859). This is the Brothers Grimm version of the story and in 1844 translated into English by Margarate Hunt. KHM1 004: Kinder- und Hausmärchen (Children’s and Household Tales)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Grimm, Grimm, Andersen e.o.: Fables, Fairy Tales & Stories, Grimm, Jacob & Wilhelm

Märchen der Brüder Grimm

Jacob Grimm (1785-1863) & Wilhelm Grimm (1786-1859)

Der Gevatter Tod

Es hatte ein armer Mann zwölf Kinder und mußte Tag und Nacht arbeiten, damit er ihnen nur Brot geben konnte. Als nun das dreizehnte zur Welt kam, wußte er sich in seiner Not nicht zu helfen, lief hinaus auf die große Landstraße und wollte den ersten, der ihm begegnete, zu Gevatter bitten. Der erste, der ihm begegnete, das war der liebe Gott. Der wußte schon, was er auf dem Herzen hatte, und sprach zu ihm: “Armer Mann, du dauerst mich, ich will dein Kind aus der Taufe heben, will für es sorgen und es glücklich machen auf Erden.” Der Mann sprach: “Wer bist du?” – “Ich bin der liebe Gott.” – “So begehr’ ich dich nicht zu Gevatter,” sagte der Mann, “du gibst dem Reichen und lässest den Armen hungern.” Das sprach der Mann, weil er nicht wußte, wie weislich Gott Reichtum und Armut verteilt. Also wendete er sich von dem Herrn und ging weiter. Da trat der Teufel zu ihm und sprach: “Was suchst du? Willst du mich zum Paten deines Kindes nehmen, so will ich ihm Gold die Hülle und Fülle und alle Lust der Welt dazu geben.” Der Mann fragte: “Wer bist du?” – “Ich bin der Teufel.” – “So begehr’ ich dich nicht zu Gevatter,” sprach der Mann, “du betrügst und verführst die Menschen.” Er ging weiter; da kam der dürrbeinige Tod auf ihn zugeschritten und sprach: “Nimm mich zu Gevatter.” Der Mann fragte: “Wer bist du?” – “Ich bin der Tod, der alle gleichmacht.” Da sprach der Mann: “Du bist der Rechte, du holst den Reichen wie den Armen ohne Unterschied, du sollst mein Gevattersmann sein.” Der Tod antwortete: “Ich will dein Kind reich und berühmt machen; denn wer mich zum Freunde hat, dem kann’s nicht fehlen.” Der Mann sprach: “Künftigen Sonntag ist die Taufe, da stelle dich zu rechter Zeit ein.” Der Tod erschien, wie er versprochen hatte, und stand ganz ordentlich Gevatter.

Als der Knabe zu Jahren gekommen war, trat zu einer Zeit der Pate ein und hieß ihn mitgehen. Er führte ihn hinaus in den Wald, zeigte ihm ein Kraut, das da wuchs, und sprach: “Jetzt sollst du dein Patengeschenk empfangen. Ich mache dich zu einem berühmten Arzt. Wenn du zu einem Kranken gerufen wirst, so will ich dir jedesmal erscheinen: steh ich zu Häupten des Kranken, so kannst du keck sprechen, du wolltest ihn wieder gesund machen, und gibst du ihm dann von jenem Kraut ein, so wird er genesen; steh ich aber zu Füßen des Kranken, so ist er mein, und du mußt sagen, alle Hilfe sei umsonst und kein Arzt in der Welt könne ihn retten. Aber hüte dich, daß du das Kraut nicht gegen meinen Willen gebrauchst, es könnte dir schlimm ergehen!”

Es dauerte nicht lange, so war der Jüngling der berühmteste Arzt auf der ganzen Welt. “Er braucht nur den Kranken anzusehen, so weiß er schon, wie es steht, ob er wieder gesund wird oder ob er sterben muß,” so hieß es von ihm, und weit und breit kamen die Leute herbei, holten ihn zu den Kranken und gaben ihm so viel Gold, daß er bald ein reicher Mann war. Nun trug es sich zu, daß der König erkrankte. Der Arzt ward berufen und sollte sagen, ob Genesung möglich wäre. Wie er aber zu dem Bette trat, so stand der Tod zu den Füßen des Kranken, und da war für ihn kein Kraut mehr gewachsen. “Wenn ich doch einmal den Tod überlisten könnte,” dachte der Arzt, “er wird’s freilich übelnehmen, aber da ich sein Pate bin, so drückt er wohl ein Auge zu, ich will’s wagen.” Er fasste also den Kranken und legte ihn verkehrt, so daß der Tod zu Haupten desselben zu stehen kam. Dann gab er ihm von dem Kraute ein, und der König erholte sich und ward wieder gesund. Der Tod aber kam zu dem Arzte, machte ein böses und finsteres Gesicht, drohte mit dem Finger und sagte: “Du hast mich hinter das Licht geführt, diesmal will ich dir’s nachsehen, weil du mein Pate bist, aber wagst du das noch einmal, so geht dir’s an den Kragen, und ich nehme dich selbst mit fort.”

Bald hernach verfiel die Tochter des Königs in eine schwere Krankheit. Sie war sein einziges Kind, er weinte Tag und Nacht, daß ihm die Augen erblindeten, und ließ bekanntmachen, wer sie vom Tode errette, der sollte ihr Gemahl werden und die Krone erben. Der Arzt, als er zu dem Bette der Kranken kam, erblickte den Tod zu ihren Füßen. Er hätte sich der Warnung seines Paten erinnern sollen, aber die große Schönheit der Königstochter und das Glück, ihr Gemahl zu werden, betörten ihn so, daß er alle Gedanken in den Wind schlug. Er sah nicht, daß der Tod ihm zornige Blicke zuwarf, die Hand in die Höhe hob und mit der dürren Faust drohte; er hob die Kranke auf und legte ihr Haupt dahin, wo die Füße gelegen hatten. Dann gab er ihr das Kraut ein, und alsbald regte sich das Leben von neuem.

Der Tod, als er sich zum zweitenmal um sein Eigentum betrogen sah, ging mit langen Schritten auf den Arzt zu und sprach: “Es ist aus mit dir, und die Reihe kommt nun an dich,” packte ihn mit seiner eiskalten Hand so hart, daß er nicht widerstehen konnte, und führte ihn in eine unterirdische Höhle. Da sah er, wie tausend und tausend Lichter in unübersehbaren Reihen brannten, einige groß, andere halbgroß, andere klein. Jeden Augenblick verloschen einige, und andere brannten wieder auf, also daß die Flämmchen in beständigem Wechsel zu sein schienen. “Siehst du,” sprach der Tod, “das sind die Lebenslichter der Menschen. Die großen gehören Kindern, die halbgroßen Eheleuten in ihren besten Jahren, die kleinen gehören Greisen. Doch auch Kinder und junge Leute haben oft nur ein kleines Lichtchen.” – “Zeige mir mein Lebenslicht,” sagte der Arzt und meinte, es wäre noch recht groß. Der Tod deutete auf ein kleines Endchen, das eben auszugehen drohte, und sagte: “Siehst du, da ist es.” – “Ach, lieber Pate,” sagte der erschrockene Arzt, “zündet mir ein neues an, tut mir’s zuliebe, damit ich König werde und Gemahl der schönen Königstochter.” – “Ich kann nicht,” antwortete der Tod, “erst muß eins verlöschen, eh’ ein neues anbrennt.” – “So setzt das alte auf ein neues, das gleich fortbrennt, wenn jenes zu Ende ist,” bat der Arzt. Der Tod stellte sich, als ob er seinen Wunsch erfüllen wollte, langte ein frisches, großes Licht herbei, aber weil er sich rächen wollte, versah er’s beim Umstecken absichtlich, und das Stöckchen fiel um und verlosch. Alsbald sank der Arzt zu Boden und war nun selbst in die Hand des Todes geraten.

ENDE

Die Märchen der Brüder Grimm

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Grimm, Andersen e.o.: Fables, Fairy Tales & Stories, Grimm, Jacob & Wilhelm

Märchen der Brüder Grimm

Jacob Grimm (1785-1863) & Wilhelm Grimm (1786-1859)

Der arme Junge im Grab

Es war einmal ein armer Hirtenjunge’ dem war Vater und Mutter gestorben, und er war von der Obrigkeit einem reichen Mann in das Haus gegeben, der sollte ihn ernähren und erziehen. Der Mann aber und seine Frau hatten ein böses Herz, waren bei allem Reichtum geizig und mißgünstig, und ärgerten sich, wenn jemand einen Bissen von ihrem Brot in den Mund steckte. Der arme Junge mochte tun, was er wollte, er erhielt wenig zu essen, aber desto mehr Schläge.

Eines Tages sollte er die Glucke mit ihren Küchlein hüten. Sie verlief sich aber mit ihren Jungen durch einen Heckenzaun: gleich schoß der Habicht herab und entführte sie durch die Lüfte. Der Junge schrie aus Leibeskräften ‘Dieb, Dieb, Spitzbub.’ Aber was half das? der Habicht brachte seinen Raub nicht wieder zurück. Der Mann hörte den Lärm, lief herbei, und als er vernahm, daß seine Henne weg war, so geriet er in Wut und gab dem Jungen eine solche Tracht Schläge, daß er sich ein paar Tage lang nicht regen konnte. Nun mußte er die Küchlein ohne die Henne hüten, aber da war die Not noch größer, das eine lief dahin, das andere dorthin. Da meinte er es klug zu machen, wenn er sie alle zusammen an eine Schnur bände, weil ihm dann der Habicht keins wegstehlen könnte. Aber weit gefehlt. Nach ein paar Tagen, als er von dem Herumlaufen und vom Hunger ermüdet einschlief, kam der Raubvogel und packte eins von den Küchlein, und da die andern daran festhingen, so trug er sie alle mit fort, setzte sich auf einen Baum und schluckte sie hinunter. Der Bauer kam eben nach Haus, und als er das Unglück sah, erboste er sich und schlug den Jungen so unbarmherzig, daß er mehrere Tage im Bette liegen mußte.

Als er wieder auf den Beinen war, sprach der Bauer zu ihm ‘du bist mir zu dumm, ich kann dich zum Hüter nicht brauchen, du sollst als Bote gehen.’ Da schickte er ihn zum Richter, dem er einen Korb voll Trauben bringen sollte, und gab ihm noch einen Brief mit. Unterwegs plagte Hunger und Durst den armen Jungen so heftig, daß er zwei von den Trauben aß. Er brachte dem Richter den Korb, als dieser aber den Brief gelesen und die Trauben gezählt hatte, so sagte er ‘es fehlen zwei Stück.’ Der Junge gestand ganz ehrlich, daß er, von Hunger und Durst getrieben, die fehlenden verzehrt habe. Der Richter schrieb einen Brief an den Bauer und verlangte noch einmal soviel Trauben. Auch diese mußte der Junge mit einem Brief hintragen. Als ihn wieder so gewaltig hungerte und durstete, so konnte er sich nicht anders helfen, er verzehrte abermals zwei Trauben. Doch nahm er vorher den Brief aus dem Korb, legte ihn unter einen Stein und setzte sich darauf, damit der Brief nicht zusehen und ihn verraten könnte. Der Richter aber stellte ihn doch der fehlenden Stücke wegen zur Rede. ‘Ach,’ sagte der Junge, ‘wie habt Ihr das erfahren? der Brief konnte es nicht wissen, denn ich hatte ihn zuvor unter einen Stein gelegt.’ Der Richter mußte über die Einfalt lachen, und schickte dem Mann einen Brief, worin er ihn ermahnte, den armen Jungen besser zu halten und es ihm an Speis und Trank nicht fehlen zu lassen; auch möchte er ihn lehren, was recht und unrecht sei.

‘Ich will dir den Unterschied schon zeigen,’ sagte der harte Mann; ‘willst du aber essen’ so mußt du auch arbeiten, und tust du etwas Unrechtes, so sollst du durch Schläge hinlänglich belehrt werden.’ Am folgenden Tag stellte er ihn an eine schwere Arbeit. Er sollte ein paar Bund Stroh zum Futter für die Pferde schneiden; dabei drohte der Mann: ‘in fünf Stunden,’ sprach er, ‘bin ich wieder zurück, wenn dann das Stroh nicht zu Häcksel geschnitten ist, so schlage ich dich so lange, bis du kein Glied mehr regen kannst.’ Der Bauer ging mit seiner Frau, dem Knecht und der Magd auf den Jahrmarkt und ließ dem Jungen nichts zurück als ein kleines Stück Brot. Der Junge stellte sich an den Strohstuhl und fing an, aus allen Leibeskräften zu arbeiten. Da ihm dabei heiß ward, so zog er sein Röcklein aus und warfs auf das Stroh. In der Angst, nicht fertig zu werden, schnitt er immerzu, und in seinem Eifer zerschnitt er unvermerkt mit dem Stroh auch sein Röcklein. Zu spät ward er das Unglück gewahr, das sich nicht wieder gutmachen ließ. ‘Ach,’ rief er, ‘jetzt ist es aus mit mir. Der böse Mann hat mir nicht umsonst gedroht, kommt er zurück und sieht, was ich getan habe, so schlägt er mich tot. Lieber will ich mir selbst das Leben nehmen.’

Der Junge hatte einmal gehört, wie die Bäuerin sprach ‘unter dem Bett habe ich einen Topf mit Gift stehen.’ Sie hatte es aber nur gesagt, um die Näscher zurückzuhalten, denn es war Honig darin. Der Junge kroch unter das Bett, holte den Topf hervor und aß ihn ganz aus. ‘Ich weiß nicht,’ sprach er, ‘die Leute sagen’ der Tod sei bitter, mir schmeckt er süß. Kein Wunder, daß die Bäuerin sich so oft den Tod wünscht.’ Er setzte sich auf ein Stühlchen und war gefaßt zu sterben. Aber statt daß er schwächer werden sollte, fühlte er sich von der nahrhaften Speise gestärkt. ‘Es muß kein Gift gewesen sein,’ sagte er, ‘aber der Bauer hat einmal gesagt’ in seinem Kleiderkasten läge ein Fläschchen mit Fliegengift, das wird wohl das wahre Gift sein und mir den Tod bringen.’ Es war aber kein Fliegengift’ sondern Ungarwein. Der Junge holte die Flasche heraus und trank sie aus. ‘Auch dieser Tod schmeckt süß,’ sagte er, doch als bald hernach der Wein anfing ihm ins Gehirn zu steigen und ihn zu betäuben, so meinte er, sein Ende nahte sich heran. ‘Ich fühle, daß ich sterben muß,’ sprach er, ‘ich will hinaus auf den Kirchhof gehen und ein Grab suchen.’ Er taumelte fort, erreichte den Kirchhof und legte sich in ein frisch geöffnetes Grab. Die Sinne verschwanden ihm immer mehr. In der Nähe stand ein Wirtshaus, wo eine Hochzeit gefeiert wurde: als er die Musik hörte, deuchte er sich schon im Paradies zu sein, bis er endlich alle Besinnung verlor. Der arme Junge erwachte nicht wieder, die Glut des heißen Weines und der kalte Tau der Nacht nahmen ihm das Leben, und er verblieb in dem Grab, in das er sich selbst gelegt hatte.

Als der Bauer die Nachricht von dem Tod des Jungen erhielt, erschrak er und fürchtete, vor das Gericht geführt zu werden: ja die Angst faßte ihn so gewaltig, daß er ohnmächtig zur Erde sank. Die Frau, die mit einer Pfanne voll Schmalz am Herde stand, lief herzu, um ihm Beistand zu leisten. Aber das Feuer schlug in die Pfanne, ergriff das ganze Haus, und nach wenigen Stunden lag es schon in Asche. Die Jahre, die sie noch zu leben hatten, brachten sie, von Gewissensbissen geplagt, in Armut und Elend zu.

ENDE

Die Märchen der Brüder Grimm

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Grimm, Grimm, Andersen e.o.: Fables, Fairy Tales & Stories, Grimm, Jacob & Wilhelm

.jpg)

Märchen der Brüder Grimm

Jacob Grimm (1785-1863) & Wilhelm Grimm (1786-1859)

Der Wolf und der Mensch

Der Fuchs erzählte einmal dem Wolf von der Stärke des Menschen, kein Tier könnte ihm widerstehen, und sie müßten List gebrauchen, um sich vor ihm zu erhalten. Da antwortete der Wolf ‘wenn ich nur einmal einen Menschen zu sehen bekäme, ich wollte doch auf ihn losgehen.’ ‘Dazu kann ich dir helfen,’ sprach der Fuchs, ‘komm nur morgen früh zu mir, so will ich dir einen zeigen.’ Der Wolf stellte sich frühzeitig ein, und der Fuchs brachte ihn hinaus auf den Weg, den der Jäger alle Tage ging. Zuerst kam ein alter abgedankter Soldat. ‘Ist das ein Mensch?’ fragte der Wolf. ‘Nein,’ antwortete der Fuchs, ‘das ist einer gewesen.’ Danach kam ein kleiner Knabe, der zur Schule wollte. ‘Ist das ein Mensch?’ ‘Nein, das will erst einer werden.’ Endlich kam der Jäger, die Doppelflinte auf dem Rücken und den Hirschfänger an der Seite. Sprach der Fuchs zum Wolf ‘siehst du, dort kommt ein Mensch, auf den mußt du losgehen, ich aber will mich fort in meine Höhle machen.’ Der Wolf ging nun auf den Menschen los, der Jäger, als er ihn erblickte, sprach ‘es ist schade, daß ich keine Kugel geladen habe,’ legte an und schoß dem Wolf das Schrot ins Gesicht. Der Wolf verzog das Gesicht gewaltig, doch ließ er sich nicht schrecken und ging vorwärts: da gab ihm der Jäger die zweite Ladung. Der Wolf verbiß den Schmerz und rückte dem Jäger zu Leibe: da zog dieser seinen blanken Hirschfänger und gab ihm links und rechts ein paar Hiebe, daß er, über und über blutend, mit Geheul zu dem Fuchs zurücklief. ‘Nun, Bruder Wolf,’ sprach der Fuchs, ‘wie bist du mit dem Menschen fertig worden?’ ‘Ach,’ antwortete der Wolf, ‘so hab ich mir die Stärke des Menschen nicht vorgestellt, erst nahm er einen Stock von der Schulter und blies hinein, da flog mir etwas ins Gesicht, das hat mich ganz entsetzlich gekitzelt: danach pustete er noch einmal in den Stock, da flog mirs um die Nase wie Blitz und Hagelwetter, und wie ich ganz nah war, da zog er eine blanke Rippe aus dem Leib, damit hat er so auf mich losgeschlagen, daß ich beinah tot wäre liegen geblieben.’ ‘Siehst du,’ sprach der Fuchs, ‘was du für ein Prahlhans bist: du wirfst das Beil so weit, daß dus nicht wieder holen kannst.’

ENDE

Die Märchen der Brüder Grimm

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Grimm, Grimm, Andersen e.o.: Fables, Fairy Tales & Stories, Grimm, Jacob & Wilhelm

.jpg)

Märchen der Brüder Grimm

Jacob Grimm (1785-1863) & Wilhelm Grimm (1786-1859)

Die drei Sprachen

In der Schweiz lebte einmal ein alter Graf, der hatte nur einen einzigen Sohn, aber er war dumm und konnte nichts lernen. Da sprach der Vater: “Höre, mein Sohn, ich bringe nichts in deinen Kopf, ich mag es anfangen, wie ich will. Du mußt fort von hier, ich will dich einem berühmten Meister übergeben. der soll es mit dir versuchen.” Der Junge ward in eine fremde Stadt geschickt, und blieb bei dem Meister ein ganzes Jahr. Nach Verlauf dieser Zeit kam er wieder heim, und der Vater fragte: “Nun mein Sohn, was hast du gelernt?” – “Vater, ich habe gelernt, was die Hunde bellen,” antwortete er. “Daß Gott erbarm!” rief der Vater aus, “ist das alles, was du gelernt hast? ich will dich in eine andere Stadt zu einem andern Meister tun.”

Der Junge ward hingebracht, und blieb bei diesem Meister auch ein Jahr. Als er zurückkam, fragte der Vater wiederum: “Mein Sohn, was hast du gelernt?” Er antwortete: “Vater, ich habe gelernt, was die Vögli sprechen.” Da geriet der Vater in Zorn und sprach: “O, du verlorner Mensch, hast die kostbare Zeit hingebracht und nichts gelernt, und schämst dich nicht, mir unter die Augen zu treten? Ich will dich zu einem dritten Meister schicken, aber lernst du auch diesmal nichts, so will ich dein Vater nicht mehr sein.” Der Sohn blieb bei dem dritten Meister ebenfalls ein ganzes Jahr, und als er wieder nach Haus kam und der Vater fragte: “Mein Sohn, was hast du gelernt?” so antwortete er: “Lieber Vater, ich habe dieses Jahr gelernt, was die Frösche quaken.” Da geriet der Vater in den höchsten Zorn, sprang auf, rief seine Leute herbei und sprach:“Dieser Mensch ist mein Sohn nicht mehr, ich stoße ihn aus und gebiete euch, daß ihr ihn hinaus in den Wald führt und ihm das Leben nehmt.” Sie führten ihn hinaus, aber als sie ihn töten sollten, konnten sie nicht vor Mitleiden und ließen ihn gehen. Sie schnitten einem Reh Augen und Zunge aus, damit sie dem Alten die Wahrzeichen bringen konnten.

Der Jüngling wanderte fort und kam nach einiger Zeit zu einer Burg, wo er um Nachtherberge bat. “Ja,” sagte der Burgherr, “wenn du da unten in dem alten Turm übernachten willst, so gehe hin, aber ich warne dich, es ist lebensgefährlich, denn er ist voll wilder Hunde, die bellen und heulen in einem fort, und zu gewissen Stunden müssen sie einen Menschen ausgeliefert haben, den sie auch gleich verzehren.” Die ganze Gegend war darüber in Trauer und Leid, und konnte doch niemand helfen. Der Jüngling aber war ohne Furcht und sprach: “Laßt mich nur hinab zu den bellenden Hunden, und gebt mir etwas, das ich ihnen vorwerfen kann; mir sollen sie nichts tun.” Weil er nun selber nicht anders wollte, so gaben sie ihm etwas Essen für die wilden Tiere und brachten ihn hinab zu dem Turm. Als er hineintrat, bellten ihn die Hunde nicht an, wedelten mit den Schwänzen ganz freundlich um ihn herum, fraßen, was er ihnen hinsetzte, und krümmten ihm kein Härchen. Am andern Morgen kam er zu jedermanns Erstaunen gesund und unversehrt wieder zum Vorschein und sagte zu dem Burgherrn: “Die Hunde haben mir in ihrer Sprache offenbart, warum sie da hausen und dem Lande Schaden bringen. Sie sind verwünscht und müssen einen großen Schatz hüten, der unten im Turme liegt, und kommen nicht eher zur Ruhe, als bis er gehoben ist, und wie dies geschehen muß, das habe ich ebenfalls aus ihren Reden vernommen.” Da freuten sich alle, die das hörten, und der Burgherr sagte, er wollte ihn an Sohnes Statt annehmen, wenn er es glücklich vollbrächte. Er stieg wieder hinab, und weil er wußte, was er zu tun hatte, so vollführte er es und brachte eine mit Gold gefüllte Truhe herauf. Das Geheul der wilden Hunde ward von nun an nicht mehr gehört, sie waren verschwunden, und das Land war von der Plage befreit.

Über eine Zeit kam es ihm in den Sinn, er wollte nach Rom fahren. Auf dem Weg kam er an einem Sumpf vorbei, in welchem Frösche saßen und quakten. Er horchte auf, und als er vernahm, was sie sprachen, ward er ganz nachdenklich und traurig. Endlich langte er in Rom an, da war gerade der Papst gestorben, und unter den Kardinälen großer Zweifel, wen sie zum Nachfolger bestimmen sollten. Sie wurden zuletzt einig, derjenige sollte zum Papst erwählt werden, an dem sich ein göttliches Wunderzeichen offenbaren würde. Und als das eben beschlossen war, in demselben Augenblick trat der junge Graf in die Kirche, und plötzlich flogen zwei schneeweiße Tauben auf seine beiden Schultern und blieben da sitzen. Die Geistlichkeit erkannte darin das Zeichen Gottes und fragte ihn auf der Stelle, ob er Papst werden wolle. Er war unschlüssig und wußte nicht, ob er dessen würdig wäre, aber die Tauben redeten ihm zu, daß er es tun möchte, und endlich sagte er “Ja.” Da wurde er gesalbt und geweiht, und damit war eingetroffen, was er von den Fröschen unterwegs gehört und was ihn so bestürzt gemacht hatte, daß er der heilige Papst werden sollte. Darauf mußte er eine Messe singen und wußte kein Wort davon, aber die zwei Tauben saßen stets auf seinen Schultern und sagten ihm alles ins Ohr.

ENDE

Die Märchen der Brüder Grimm

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Grimm, Grimm, Andersen e.o.: Fables, Fairy Tales & Stories, Grimm, Jacob & Wilhelm

Märchen der Brüder Grimm

Jacob Grimm (1785-1863) & Wilhelm Grimm (1786-1859)

Das Totenhemdchen

Es hatte eine Mutter ein Büblein von sieben Jahren, das war so schön und lieblich, daß es niemand ansehen konnte, ohne mit ihm gut zu sein, und sie hatte es auch lieber als alles auf der Welt. Nun geschah es, daß es plötzlich krank ward, und der liebe Gott es zu sich nahm; darüber konnte sich die Mutter nicht trösten und weinte Tag und Nacht. Bald darauf aber, nachdem es begraben war, zeigte sich das Kind nachts an den Plätzen, wo es sonst im Leben gesessen und gespielt hatte; weinte die Mutter, so weinte es auch, und wenn der Morgen kam, war es verschwunden. Als aber die Mutter gar nicht aufhören wollte zu weinen, kam es in einer Nacht mit seinem weißen Totenhemdchen, in welchem es in den Sarg gelegt war, und mit dem Kränzchen auf dem Kopf, setzte sich zu ihren Füßen auf das Bett und sprach ‘ach Mutter, höre doch auf zu weinen, sonst kann ich in meinem Sarge nicht einschlafen, denn mein Totenhemdchen wird nicht trocken von deinen Tränen, die alle darauf fallen.’ Da erschrak die Mutter, als sie das hörte, und weinte nicht mehr. Und in der andern Nacht kam das Kindchen wieder, hielt in der Hand ein Lichtchen und sagte ‘siehst du, nun ist mein Hemdchen bald trocken, und ich habe Ruhe in meinem Grab.’ Da befahl die Mutter dem lieben Gott ihr Leid und ertrug es still und geduldig, und das Kind kam nicht wieder, sondern schlief in seinem unterirdischen Bettchen.

ENDE

Die Märchen der Brüder Grimm

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Grimm, Grimm, Andersen e.o.: Fables, Fairy Tales & Stories, Grimm, Jacob & Wilhelm

.jpg)

Märchen der Brüder Grimm

Jacob Grimm (1785-1863) & Wilhelm Grimm (1786-1859)

Die Sterntaler

Es war einmal ein kleines Mädchen, dem war Vater und Mutter gestorben, und es war so arm, dass es kein Kämmerchen mehr hatte, darin zu wohnen, und kein Bettchen mehr hatte, darin zu schlafen, und endlich gar nichts mehr als die Kleider auf dem Leib und ein Stückchen Brot in der Hand, das ihm ein mitleidiges Herz geschenkt hatte. Es war aber gut und fromm. Und weil es so von aller Welt verlassen war, ging es im Vertrauen auf den lieben Gott hinaus ins Feld.

Da begegnete ihm ein armer Mann, der sprach: “Ach, gib mir etwas zu essen, ich bin so hungrig.” Es reichte ihm das ganze Stückchen Brot und sagte: “Gott segne dir’s,” und ging weiter. Da kam ein Kind, das jammerte und sprach: “Es friert mich so an meinem Kopfe, schenk mir etwas, womit ich ihn bedecken kann.” Da tat es seine Mütze ab und gab sie ihm. Und als es noch eine Weile gegangen war, kam wieder ein Kind und hatte kein Leibchen an und fror: da gab es ihm seins; und noch weiter, da bat eins um ein Röcklein, das gab es auch von sich hin. Endlich gelangte es in einen Wald, und es war schon dunkel geworden, da kam noch eins und bat um ein Hemdlein, und das fromme Mädchen dachte: “Es ist dunkle Nacht, da sieht dich niemand, du kannst wohl dein Hemd weggeben,” und zog das Hemd ab und gab es auch noch hin.

Und wie es so stand und gar nichts mehr hatte, fielen auf einmal die Sterne vom Himmel, und waren lauter blanke Taler; und ob es gleich sein Hemdlein weggegeben, so hatte es ein neues an, und das war vom allerfeinsten Linnen. Da sammelte es sich die Taler hinein und war reich für sein Lebtag.

ENDE

Die Märchen der Brüder Grimm

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Grimm, Grimm, Andersen e.o.: Fables, Fairy Tales & Stories, Grimm, Jacob & Wilhelm

.jpg)

Märchen der Brüder Grimm

Jacob Grimm (1785-1863) & Wilhelm Grimm (1786-1859)

Frau Trude