Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

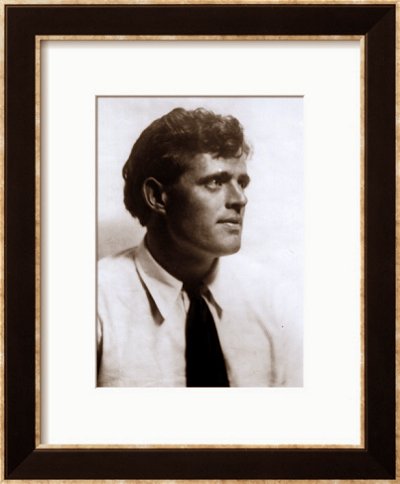

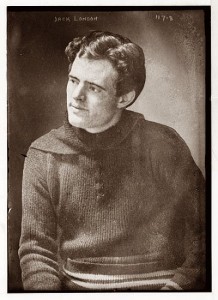

Jack London

(1876-1916)

The Water Baby

I lent a weary ear to old Kohokumu’s interminable chanting of the

deeds and adventures of Maui, the Promethean demi-god of Polynesia

who fished up dry land from ocean depths with hooks made fast to

heaven, who lifted up the sky whereunder previously men had gone on

all-fours, not having space to stand erect, and who made the sun

with its sixteen snared legs stand still and agree thereafter to

traverse the sky more slowly–the sun being evidently a trade

unionist and believing in the six-hour day, while Maui stood for

the open shop and the twelve-hour day.

“Now this,” said Kohokumu, “is from Queen Lililuokalani’s own

family mele:

“Maui became restless and fought the sun

With a noose that he laid.

And winter won the sun,

And summer was won by Maui . . . “

Born in the Islands myself, I knew the Hawaiian myths better than

this old fisherman, although I possessed not his memorization that

enabled him to recite them endless hours.

“And you believe all this?” I demanded in the sweet Hawaiian

tongue.

“It was a long time ago,” he pondered. “I never saw Maui with my

own eyes. But all our old men from all the way back tell us these

things, as I, an old man, tell them to my sons and grandsons, who

will tell them to their sons and grandsons all the way ahead to

come.”

“You believe,” I persisted, “that whopper of Maui roping the sun

like a wild steer, and that other whopper of heaving up the sky

from off the earth?”

“I am of little worth, and am not wise, O Lakana,” my fisherman

made answer. “Yet have I read the Hawaiian Bible the missionaries

translated to us, and there have I read that your Big Man of the

Beginning made the earth, and sky, and sun, and moon, and stars,

and all manner of animals from horses to cockroaches and from

centipedes and mosquitoes to sea lice and jellyfish, and man and

woman, and everything, and all in six days. Why, Maui didn’t do

anything like that much. He didn’t make anything. He just put

things in order, that was all, and it took him a long, long time to

make the improvements. And anyway, it is much easier and more

reasonable to believe the little whopper than the big whopper.”

And what could I reply? He had me on the matter of reasonableness.

Besides, my head ached. And the funny thing, as I admitted it to

myself, was that evolution teaches in no uncertain voice that man

did run on all-fours ere he came to walk upright, that astronomy

states flatly that the speed of the revolution of the earth on its

axis has diminished steadily, thus increasing the length of day,

and that the seismologists accept that all the islands of Hawaii

were elevated from the ocean floor by volcanic action.

Fortunately, I saw a bamboo pole, floating on the surface several

hundred feet away, suddenly up-end and start a very devil’s dance.

This was a diversion from the profitless discussion, and Kohokumu

and I dipped our paddles and raced the little outrigger canoe to

the dancing pole. Kohokumu caught the line that was fast to the

butt of the pole and under-handed it in until a two-foot ukikiki,

battling fiercely to the end, flashed its wet silver in the sun and

began beating a tattoo on the inside bottom of the canoe. Kohokumu

picked up a squirming, slimy squid, with his teeth bit a chunk of

live bait out of it, attached the bait to the hook, and dropped

line and sinker overside. The stick floated flat on the surface of

the water, and the canoe drifted slowly away. With a survey of the

crescent composed of a score of such sticks all lying flat,

Kohokumu wiped his hands on his naked sides and lifted the

wearisome and centuries-old chant of Kuali:

“Oh, the great fish-hook of Maui!

Manai-i-ka-lani–“made fast to the heavens”!

An earth-twisted cord ties the hook,

Engulfed from lofty Kauiki!

Its bait the red-billed Alae,

The bird to Hina sacred!

It sinks far down to Hawaii,

Struggling and in pain dying!

Caught is the land beneath the water,

Floated up, up to the surface,

But Hina hid a wing of the bird

And broke the land beneath the water!

Below was the bait snatched away

And eaten at once by the fishes,

The Ulua of the deep muddy places!

His aged voice was hoarse and scratchy from the drinking of too

much swipes at a funeral the night before, nothing of which

contributed to make me less irritable. My head ached. The sun-

glare on the water made my eyes ache, while I was suffering more

than half a touch of mal de mer from the antic conduct of the

outrigger on the blobby sea. The air was stagnant. In the lee of

Waihee, between the white beach and the roof, no whisper of breeze

eased the still sultriness. I really think I was too miserable to

summon the resolution to give up the fishing and go in to shore.

Lying back with closed eyes, I lost count of time. I even forgot

that Kohokumu was chanting till reminded of it by his ceasing. An

exclamation made me bare my eyes to the stab of the sun. He was

gazing down through the water-glass.

“It’s a big one,” he said, passing me the device and slipping over-

side feet-first into the water.

He went under without splash and ripple, turned over and swam down.

I followed his progress through the water-glass, which is merely an

oblong box a couple of feet long, open at the top, the bottom

sealed water-tight with a sheet of ordinary glass.

Now Kohokumu was a bore, and I was squeamishly out of sorts with

him for his volubleness, but I could not help admiring him as I

watched him go down. Past seventy years of age, lean as a

toothpick, and shrivelled like a mummy, he was doing what few young

athletes of my race would do or could do. It was forty feet to

bottom. There, partly exposed, but mostly hidden under the bulge

of a coral lump, I could discern his objective. His keen eyes had

caught the projecting tentacle of a squid. Even as he swam, the

tentacle was lazily withdrawn, so that there was no sign of the

creature. But the brief exposure of the portion of one tentacle

had advertised its owner as a squid of size.

The pressure at a depth of forty feet is no joke for a young man,

yet it did not seem to inconvenience this oldster. I am certain it

never crossed his mind to be inconvenienced. Unarmed, bare of body

save for a brief malo or loin cloth, he was undeterred by the

formidable creature that constituted his prey. I saw him steady

himself with his right hand on the coral lump, and thrust his left

arm into the hole to the shoulder. Half a minute elapsed, during

which time he seemed to be groping and rooting around with his left

hand. Then tentacle after tentacle, myriad-suckered and wildly

waving, emerged. Laying hold of his arm, they writhed and coiled

about his flesh like so many snakes. With a heave and a jerk

appeared the entire squid, a proper devil-fish or octopus.

But the old man was in no hurry for his natural element, the air

above the water. There, forty feet beneath, wrapped about by an

octopus that measured nine feet across from tentacle-tip to

tentacle-tip and that could well drown the stoutest swimmer, he

coolly and casually did the one thing that gave to him and his

empery over the monster. He shoved his lean, hawk-like face into

the very centre of the slimy, squirming mass, and with his several

ancient fangs bit into the heart and the life of the matter. This

accomplished, he came upward, slowly, as a swimmer should who is

changing atmospheres from the depths. Alongside the canoe, still

in the water and peeling off the grisly clinging thing, the

incorrigible old sinner burst into the pule of triumph which had

been chanted by the countless squid-catching generations before

him:

“O Kanaloa of the taboo nights!

Stand upright on the solid floor!

Stand upon the floor where lies the squid!

Stand up to take the squid of the deep sea!

Rise up, O Kanaloa!

Stir up! Stir up! Let the squid awake!

Let the squid that lies flat awake! Let the squid that lies spread

out . . . “

I closed my eyes and ears, not offering to lend him a hand, secure

in the knowledge that he could climb back unaided into the unstable

craft without the slightest risk of upsetting it.

“A very fine squid,” he crooned. “It is a wahine” (female) “squid.

I shall now sing to you the song of the cowrie shell, the red

cowrie shell that we used as a bait for the squid–“

“You were disgraceful last night at the funeral,” I headed him off.

“I heard all about it. You made much noise. You sang till

everybody was deaf. You insulted the son of the widow. You drank

swipes like a pig. Swipes are not good for your extreme age. Some

day you will wake up dead. You ought to be a wreck to-day–“

“Ha!” he chuckled. “And you, who drank no swipes, who was a babe

unborn when I was already an old man, who went to bed last night

with the sun and the chickens–this day are you a wreck. Explain

me that. My ears are as thirsty to listen as was my throat thirsty

last night. And here to-day, behold, I am, as that Englishman who

came here in his yacht used to say, I am in fine form, in devilish

fine form.”

“I give you up,” I retorted, shrugging my shoulders. “Only one

thing is clear, and that is that the devil doesn’t want you.

Report of your singing has gone before you.”

“No,” he pondered the idea carefully. “It is not that. The devil

will be glad for my coming, for I have some very fine songs for

him, and scandals and old gossips of the high aliis that will make

him scratch his sides. So, let me explain to you the secret of my

birth. The Sea is my mother. I was born in a double-canoe, during

a Kona gale, in the channel of Kahoolawe. From her, the Sea, my

mother, I received my strength. Whenever I return to her arms, as

for a breast-clasp, as I have returned this day, I grow strong

again and immediately. She, to me, is the milk-giver, the life-

source–“

“Shades of Antaeus!” thought I.

“Some day,” old Kohokumu rambled on, “when I am really old, I shall

be reported of men as drowned in the sea. This will be an idle

thought of men. In truth, I shall have returned into the arms of

my mother, there to rest under the heart of her breast until the

second birth of me, when I shall emerge into the sun a flashing

youth of splendour like Maui himself when he was golden young.”

“A queer religion,” I commented.

“When I was younger I muddled my poor head over queerer religions,”

old Kohokumu retorted. “But listen, O Young Wise One, to my

elderly wisdom. This I know: as I grow old I seek less for the

truth from without me, and find more of the truth from within me.

Why have I thought this thought of my return to my mother and of my

rebirth from my mother into the sun? You do not know. I do not

know, save that, without whisper of man’s voice or printed word,

without prompting from otherwhere, this thought has arisen from

within me, from the deeps of me that are as deep as the sea. I am

not a god. I do not make things. Therefore I have not made this

thought. I do not know its father or its mother. It is of old

time before me, and therefore it is true. Man does not make truth.

Man, if he be not blind, only recognizes truth when he sees it. Is

this thought that I have thought a dream?”

“Perhaps it is you that are a dream,” I laughed. “And that I, and

sky, and sea, and the iron-hard land, are dreams, all dreams.”

“I have often thought that,” he assured me soberly. “It may well

be so. Last night I dreamed I was a lark bird, a beautiful singing

lark of the sky like the larks on the upland pastures of Haleakala.

And I flew up, up, toward the sun, singing, singing, as old

Kohokumu never sang. I tell you now that I dreamed I was a lark

bird singing in the sky. But may not I, the real I, be the lark

bird? And may not the telling of it be the dream that I, the lark

bird, am dreaming now? Who are you to tell me ay or no? Dare you

tell me I am not a lark bird asleep and dreaming that I am old

Kohokumu?”

I shrugged my shoulders, and he continued triumphantly:

“And how do you know but what you are old Maui himself asleep and

dreaming that you are John Lakana talking with me in a canoe? And

may you not awake old Maui yourself, and scratch your sides and say

that you had a funny dream in which you dreamed you were a haole?”

“I don’t know,” I admitted. “Besides, you wouldn’t believe me.”

“There is much more in dreams than we know,” he assured me with

great solemnity. “Dreams go deep, all the way down, maybe to

before the beginning. May not old Maui have only dreamed he pulled

Hawaii up from the bottom of the sea? Then would this Hawaii land

be a dream, and you, and I, and the squid there, only parts of

Maui’s dream? And the lark bird too?”

He sighed and let his head sink on his breast.

“And I worry my old head about the secrets undiscoverable,” he

resumed, “until I grow tired and want to forget, and so I drink

swipes, and go fishing, and sing old songs, and dream I am a lark

bird singing in the sky. I like that best of all, and often I

dream it when I have drunk much swipes . . . “

In great dejection of mood he peered down into the lagoon through

the water-glass.

“There will be no more bites for a while,” he announced. “The

fish-sharks are prowling around, and we shall have to wait until

they are gone. And so that the time shall not be heavy, I will

sing you the canoe-hauling song to Lono. You remember:

“Give to me the trunk of the tree, O Lono!

Give me the tree’s main root, O Lono!

Give me the ear of the tree, O Lono!–“

“For the love of mercy, don’t sing!” I cut him short. “I’ve got a

headache, and your singing hurts. You may be in devilish fine form

to-day, but your throat is rotten. I’d rather you talked about

dreams, or told me whoppers.”

“It is too bad that you are sick, and you so young,” he conceded

cheerily. “And I shall not sing any more. I shall tell you

something you do not know and have never heard; something that is

no dream and no whopper, but is what I know to have happened. Not

very long ago there lived here, on the beach beside this very

lagoon, a young boy whose name was Keikiwai, which, as you know,

means Water Baby. He was truly a water baby. His gods were the

sea and fish gods, and he was born with knowledge of the language

of fishes, which the fishes did not know until the sharks found it

out one day when they heard him talk it.

“It happened this way. The word had been brought, and the

commands, by swift runners, that the king was making a progress

around the island, and that on the next day a luau” (feast) “was to

be served him by the dwellers here of Waihee. It was always a

hardship, when the king made a progress, for the few dwellers in

small places to fill his many stomachs with food. For he came

always with his wife and her women, with his priests and sorcerers,

his dancers and flute-players, and hula-singers, and fighting men

and servants, and his high chiefs with their wives, and sorcerers,

and fighting men, and servants.

“Sometimes, in small places like Waihee, the path of his journey

was marked afterward by leanness and famine. But a king must be

fed, and it is not good to anger a king. So, like warning in

advance of disaster, Waihee heard of his coming, and all food-

getters of field and pond and mountain and sea were busied with

getting food for the feast. And behold, everything was got, from

the choicest of royal taro to sugar-cane joints for the roasting,

from opihis to limu, from fowl to wild pig and poi-fed puppies–

everything save one thing. The fishermen failed to get lobsters.

“Now be it known that the king’s favourite food was lobster. He

esteemed it above all kai-kai” (food), “and his runners had made

special mention of it. And there were no lobsters, and it is not

good to anger a king in the belly of him. Too many sharks had come

inside the reef. That was the trouble. A young girl and an old

man had been eaten by them. And of the young men who dared dive

for lobsters, one was eaten, and one lost an arm, and another lost

one hand and one foot.

“But there was Keikiwai, the Water Baby, only eleven years old, but

half fish himself and talking the language of fishes. To his

father the head men came, begging him to send the Water Baby to get

lobsters to fill the king’s belly and divert his anger.

“Now this what happened was known and observed. For the fishermen,

and their women, and the taro-growers and the bird-catchers, and

the head men, and all Waihee, came down and stood back from the

edge of the rock where the Water Baby stood and looked down at the

lobsters far beneath on the bottom.

“And a shark, looking up with its cat’s eyes, observed him, and

sent out the shark-call of ‘fresh meat’ to assemble all the sharks

in the lagoon. For the sharks work thus together, which is why

they are strong. And the sharks answered the call till there were

forty of them, long ones and short ones and lean ones and round

ones, forty of them by count; and they talked to one another,

saying: ‘Look at that titbit of a child, that morsel delicious of

human-flesh sweetness without the salt of the sea in it, of which

salt we have too much, savoury and good to eat, melting to delight

under our hearts as our bellies embrace it and extract from it its

sweet.’

“Much more they said, saying: ‘He has come for the lobsters. When

he dives in he is for one of us. Not like the old man we ate

yesterday, tough to dryness with age, nor like the young men whose

members were too hard-muscled, but tender, so tender that he will

melt in our gullets ere our bellies receive him. When he dives in,

we will all rush for him, and the lucky one of us will get him,

and, gulp, he will be gone, one bite and one swallow, into the

belly of the luckiest one of us.’

“And Keikiwai, the Water Baby, heard the conspiracy, knowing the

shark language; and he addressed a prayer, in the shark language,

to the shark god Moku-halii, and the sharks heard and waved their

tails to one another and winked their cat’s eyes in token that they

understood his talk. And then he said: ‘I shall now dive for a

lobster for the king. And no hurt shall befall me, because the

shark with the shortest tail is my friend and will protect me.

“And, so saying, he picked up a chunk of lava-rock and tossed it

into the water, with a big splash, twenty feet to one side. The

forty sharks rushed for the splash, while he dived, and by the time

they discovered they had missed him, he had gone to bottom and come

back and climbed out, within his hand a fat lobster, a wahine

lobster, full of eggs, for the king.

“‘Ha!’ said the sharks, very angry. ‘There is among us a traitor.

The titbit of a child, the morsel of sweetness, has spoken, and has

exposed the one among us who has saved him. Let us now measure the

lengths of our tails!

“Which they did, in a long row, side by side, the shorter-tailed

ones cheating and stretching to gain length on themselves, the

longer-tailed ones cheating and stretching in order not to be out-

cheated and out-stretched. They were very angry with the one with

the shortest tail, and him they rushed upon from every side and

devoured till nothing was left of him.

“Again they listened while they waited for the Water Baby to dive

in. And again the Water Baby made his prayer in the shark language

to Moku-halii, and said: ‘The shark with the shortest tail is my

friend and will protect me.’ And again the Water Baby tossed in a

chunk of lava, this time twenty feet away off to the other side.

The sharks rushed for the splash, and in their haste ran into one

another, and splashed with their tails till the water was all foam,

and they could see nothing, each thinking some other was swallowing

the titbit. And the Water Baby came up and climbed out with

another fat lobster for the king.

“And the thirty-nine sharks measured tails, devoting the one with

the shortest tail, so that there were only thirty-eight sharks.

And the Water Baby continued to do what I have said, and the sharks

to do what I have told you, while for each shark that was eaten by

his brothers there was another fat lobster laid on the rock for the

king. Of course, there was much quarrelling and argument among the

sharks when it came to measuring tails; but in the end it worked

out in rightness and justice, for, when only two sharks were left,

they were the two biggest of the original forty.

“And the Water Baby again claimed the shark with the shortest tail

was his friend, fooled the two sharks with another lava-chunk, and

brought up another lobster. The two sharks each claimed the other

had the shorter tail, and each fought to eat the other, and the one

with the longer tail won–“

“Hold, O Kohokumu!” I interrupted. “Remember that that shark had

already–“

“I know just what you are going to say,” he snatched his recital

back from me. “And you are right. It took him so long to eat the

thirty-ninth shark, for inside the thirty-ninth shark were already

the nineteen other sharks he had eaten, and inside the fortieth

shark were already the nineteen other sharks he had eaten, and he

did not have the appetite he had started with. But do not forget

he was a very big shark to begin with.

“It took him so long to eat the other shark, and the nineteen

sharks inside the other shark, that he was still eating when

darkness fell, and the people of Waihee went away home with all the

lobsters for the king. And didn’t they find the last shark on the

beach next morning dead, and burst wide open with all he had

eaten?”

Kohokumu fetched a full stop and held my eyes with his own shrewd

ones.

“Hold, O Lakana!” he checked the speech that rushed to my tongue.

“I know what next you would say. You would say that with my own

eyes I did not see this, and therefore that I do not know what I

have been telling you. But I do know, and I can prove it. My

father’s father knew the grandson of the Water Baby’s father’s

uncle. Also, there, on the rocky point to which I point my finger

now, is where the Water Baby stood and dived. I have dived for

lobsters there myself. It is a great place for lobsters. Also,

and often, have I seen sharks there. And there, on the bottom, as

I should know, for I have seen and counted them, are the thirty-

nine lava-rocks thrown in by the Water Baby as I have described.”

“But–” I began.

“Ha!” he baffled me. “Look! While we have talked the fish have

begun again to bite.”

He pointed to three of the bamboo poles erect and devil-dancing in

token that fish were hooked and struggling on the lines beneath.

As he bent to his paddle, he muttered, for my benefit:

“Of course I know. The thirty-nine lava rocks are still there.

You can count them any day for yourself. Of course I know, and I

know for a fact.”

GLEN ELLEN.

October 2, 1916.

From Jack London: ON THE MAKALOA MAT/ISLAND TALES

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, London, Jack

Jack London

(1876-1916)

The Tears of Ah Kim

There was a great noise and racket, but no scandal, in Honolulu’s

Chinatown. Those within hearing distance merely shrugged their

shoulders and smiled tolerantly at the disturbance as an affair of

accustomed usualness. “What is it?” asked Chin Mo, down with a

sharp pleurisy, of his wife, who had paused for a second at the

open window to listen.

“Only Ah Kim,” was her reply. “His mother is beating him again.”

The fracas was taking place in the garden, behind the living rooms

that were at the back of the store that fronted on the street with

the proud sign above: AH KIM COMPANY, GENERAL MERCHANDISE. The

garden was a miniature domain, twenty feet square, that somehow

cunningly seduced the eye into a sense and seeming of illimitable

vastness. There were forests of dwarf pines and oaks, centuries

old yet two or three feet in height, and imported at enormous care

and expense. A tiny bridge, a pace across, arched over a miniature

river that flowed with rapids and cataracts from a miniature lake

stocked with myriad-finned, orange-miracled goldfish that in

proportion to the lake and landscape were whales. On every side

the many windows of the several-storied shack-buildings looked

down. In the centre of the garden, on the narrow gravelled walk

close beside the lake Ah Kim was noisily receiving his beating.

No Chinese lad of tender and beatable years was Ah Kim. His was

the store of Ah Kim Company, and his was the achievement of

building it up through the long years from the shoestring of

savings of a contract coolie labourer to a bank account in four

figures and a credit that was gilt edged. An even half-century of

summers and winters had passed over his head, and, in the passing,

fattened him comfortably and snugly. Short of stature, his full

front was as rotund as a water-melon seed. His face was moon-

faced. His garb was dignified and silken, and his black-silk

skull-cap with the red button atop, now, alas! fallen on the

ground, was the skull-cap worn by the successful and dignified

merchants of his race.

But his appearance, in this moment of the present, was anything but

dignified. Dodging and ducking under a rain of blows from a bamboo

cane, he was crouched over in a half-doubled posture. When he was

rapped on the knuckles and elbows, with which he shielded his face

and head, his winces were genuine and involuntary. From the many

surrounding windows the neighbourhood looked down with placid

enjoyment.

And she who wielded the stick so shrewdly from long practice!

Seventy-four years old, she looked every minute of her time. Her

thin legs were encased in straight-lined pants of linen stiff-

textured and shiny-black. Her scraggly grey hair was drawn

unrelentingly and flatly back from a narrow, unrelenting forehead.

Eyebrows she had none, having long since shed them. Her eyes, of

pin-hole tininess, were blackest black. She was shockingly

cadaverous. Her shrivelled forearm, exposed by the loose sleeve,

possessed no more of muscle than several taut bowstrings stretched

across meagre bone under yellow, parchment-like skin. Along this

mummy arm jade bracelets shot up and down and clashed with every

blow.

“Ah!” she cried out, rhythmically accenting her blows in series of

three to each shrill observation. “I forbade you to talk to Li

Faa. To-day you stopped on the street with her. Not an hour ago.

Half an hour by the clock you talked.–What is that?”

“It was the thrice-accursed telephone,” Ah Kim muttered, while she

suspended the stick to catch what he said. “Mrs. Chang Lucy told

you. I know she did. I saw her see me. I shall have the

telephone taken out. It is of the devil.”

“It is a device of all the devils,” Mrs. Tai Fu agreed, taking a

fresh grip on the stick. “Yet shall the telephone remain. I like

to talk with Mrs. Chang Lucy over the telephone.”

“She has the eyes of ten thousand cats,” quoth Ah Kim, ducking and

receiving the stick stinging on his knuckles. “And the tongues of

ten thousand toads,” he supplemented ere his next duck.

“She is an impudent-faced and evil-mannered hussy,” Mrs. Tai Fu

accented.

“Mrs. Chang Lucy was ever that,” Ah Kim murmured like the dutiful

son he was.

“I speak of Li Faa,” his mother corrected with stick emphasis.

“She is only half Chinese, as you know. Her mother was a shameless

kanaka. She wears skirts like the degraded haole women–also

corsets, as I have seen for myself. Where are her children? Yet

has she buried two husbands.”

“The one was drowned, the other kicked by a horse,” Ah Kim

qualified.

“A year of her, unworthy son of a noble father, and you would

gladly be going out to get drowned or be kicked by a horse.”

Subdued chucklings and laughter from the window audience applauded

her point.

“You buried two husbands yourself, revered mother,” Ah Kim was

stung to retort.

“I had the good taste not to marry a third. Besides, my two

husbands died honourably in their beds. They were not kicked by

horses nor drowned at sea. What business is it of our neighbours

that you should inform them I have had two husbands, or ten, or

none? You have made a scandal of me, before all our neighbours,

and for that I shall now give you a real beating.”

Ah Kim endured the staccato rain of blows, and said when his mother

paused, breathless and weary:

“Always have I insisted and pleaded, honourable mother, that you

beat me in the house, with the windows and doors closed tight, and

not in the open street or the garden open behind the house.

“You have called this unthinkable Li Faa the Silvery Moon Blossom,”

Mrs. Tai Fu rejoined, quite illogically and femininely, but with

utmost success in so far as she deflected her son from continuance

of the thrust he had so swiftly driven home.

“Mrs. Chang Lucy told you,” he charged.

“I was told over the telephone,” his mother evaded. “I do not know

all voices that speak to me over that contrivance of all the

devils.”

Strangely, Ah Kim made no effort to run away from his mother, which

he could easily have done. She, on the other hand, found fresh

cause for more stick blows.

“Ah! Stubborn one! Why do you not cry? Mule that shameth its

ancestors! Never have I made you cry. From the time you were a

little boy I have never made you cry. Answer me! Why do you not

cry?”

Weak and breathless from her exertions, she dropped the stick and

panted and shook as if with a nervous palsy.

“I do not know, except that it is my way,” Ah Kim replied, gazing

solicitously at his mother. “I shall bring you a chair now, and

you will sit down and rest and feel better.”

But she flung away from him with a snort and tottered agedly across

the garden into the house. Meanwhile recovering his skull-cap and

smoothing his disordered attire, Ah Kim rubbed his hurts and gazed

after her with eyes of devotion. He even smiled, and almost might

it appear that he had enjoyed the beating.

Ah Kim had been so beaten ever since he was a boy, when he lived on

the high banks of the eleventh cataract of the Yangtse river. Here

his father had been born and toiled all his days from young manhood

as a towing coolie. When he died, Ah Kim, in his own young

manhood, took up the same honourable profession. Farther back than

all remembered annals of the family, had the males of it been

towing coolies. At the time of Christ his direct ancestors had

been doing the same thing, meeting the precisely similarly modelled

junks below the white water at the foot of the canyon, bending the

half-mile of rope to each junk, and, according to size, tailing on

from a hundred to two hundred coolies of them and by sheer, two-

legged man-power, bowed forward and down till their hands touched

the ground and their faces were sometimes within a foot of it,

dragging the junk up through the white water to the head of the

canyon.

Apparently, down all the intervening centuries, the payment of the

trade had not picked up. His father, his father’s father, and

himself, Ah Kim, had received the same invariable remuneration–per

junk one-fourteenth of a cent, at the rate he had since learned

money was valued in Hawaii. On long lucky summer days when the

waters were easy, the junks many, the hours of daylight sixteen,

sixteen hours of such heroic toil would earn over a cent. But in a

whole year a towing coolie did not earn more than a dollar and a

half. People could and did live on such an income. There were

women servants who received a yearly wage of a dollar. The net-

makers of Ti Wi earned between a dollar and two dollars a year.

They lived on such wages, or, at least, they did not die on them.

But for the towing coolies there were pickings, which were what

made the profession honourable and the guild a close and hereditary

corporation or labour union. One junk in five that was dragged up

through the rapids or lowered down was wrecked. One junk in every

ten was a total loss. The coolies of the towing guild knew the

freaks and whims of the currents, and grappled, and raked, and

netted a wet harvest from the river. They of the guild were looked

up to by lesser coolies, for they could afford to drink brick tea

and eat number four rice every day.

And Ah Kim had been contented and proud, until, one bitter spring

day of driving sleet and hail, he dragged ashore a drowning

Cantonese sailor. It was this wanderer, thawing out by his fire,

who first named the magic name Hawaii to him. He had himself never

been to that labourer’s paradise, said the sailor; but many Chinese

had gone there from Canton, and he had heard the talk of their

letters written back. In Hawaii was never frost nor famine. The

very pigs, never fed, were ever fat of the generous offal disdained

by man. A Cantonese or Yangtse family could live on the waste of

an Hawaii coolie. And wages! In gold dollars, ten a month, or, in

trade dollars, two a month, was what the contract Chinese coolie

received from the white-devil sugar kings. In a year the coolie

received the prodigious sum of two hundred and forty trade dollars-

-more than a hundred times what a coolie, toiling ten times as

hard, received on the eleventh cataract of the Yangtse. In short,

all things considered, an Hawaii coolie was one hundred times

better off, and, when the amount of labour was estimated, a

thousand times better off. In addition was the wonderful climate.

When Ah Kim was twenty-four, despite his mother’s pleadings and

beatings, he resigned from the ancient and honourable guild of the

eleventh cataract towing coolies, left his mother to go into a boss

coolie’s household as a servant for a dollar a year, and an annual

dress to cost not less than thirty cents, and himself departed down

the Yangtse to the great sea. Many were his adventures and severe

his toils and hardships ere, as a salt-sea junk-sailor, he won to

Canton. When he was twenty-six he signed five years of his life

and labour away to the Hawaii sugar kings and departed, one of

eight hundred contract coolies, for that far island land, on a

festering steamer run by a crazy captain and drunken officers and

rejected of Lloyds.

Honourable, among labourers, had Ah Kim’s rating been as a towing

coolie. In Hawaii, receiving a hundred times more pay, he found

himself looked down upon as the lowest of the low–a plantation

coolie, than which could be nothing lower. But a coolie whose

ancestors had towed junks up the eleventh cataract of the Yangtse

since before the birth of Christ inevitably inherits one character

in large degree, namely, the character of patience. This patience

was Ah Kim’s. At the end of five years, his compulsory servitude

over, thin as ever in body, in bank account he lacked just ten

trade dollars of possessing a thousand trade dollars.

On this sum he could have gone back to the Yangtse and retired for

life a really wealthy man. He would have possessed a larger sum,

had he not, on occasion, conservatively played che fa and fan tan,

and had he not, for a twelve-month, toiled among the centipedes and

scorpions of the stifling cane-fields in the semi-dream of a

continuous opium debauch. Why he had not toiled the whole five

years under the spell of opium was the expensiveness of the habit.

He had had no moral scruples. The drug had cost too much.

But Ah Kim did not return to China. He had observed the business

life of Hawaii and developed a vaulting ambition. For six months,

in order to learn business and English at the bottom, he clerked in

the plantation store. At the end of this time he knew more about

that particular store than did ever plantation manager know about

any plantation store. When he resigned his position he was

receiving forty gold a month, or eighty trade, and he was beginning

to put on flesh. Also, his attitude toward mere contract coolies

had become distinctively aristocratic. The manager offered to

raise him to sixty fold, which, by the year, would constitute a

fabulous fourteen hundred and forty trade, or seven hundred times

his annual earning on the Yangtse as a two-legged horse at one-

fourteenth of a gold cent per junk.

Instead of accepting, Ah Kim departed to Honolulu, and in the big

general merchandise store of Fong & Chow Fong began at the bottom

for fifteen gold per month. He worked a year and a half, and

resigned when he was thirty-three, despite the seventy-five gold

per month his Chinese employers were paying him. Then it was that

he put up his own sign: AH KIM COMPANY, GENERAL MERCHANDISE.

Also, better fed, there was about his less meagre figure a

foreshadowing of the melon-seed rotundity that was to attach to him

in future years.

With the years he prospered increasingly, so that, when he was

thirty-six, the promise of his figure was fulfilling rapidly, and,

himself a member of the exclusive and powerful Hai Gum Tong, and of

the Chinese Merchants’ Association, he was accustomed to sitting as

host at dinners that cost him as much as thirty years of towing on

the eleventh cataract would have earned him. Two things he missed:

a wife, and his mother to lay the stick on him as of yore.

When he was thirty-seven he consulted his bank balance. It stood

him three thousand gold. For twenty-five hundred down and an easy

mortgage he could buy the three-story shack-building, and the

ground in fee simple on which it stood. But to do this, left only

five hundred for a wife. Fu Yee Po had a marriageable, properly

small-footed daughter whom he was willing to import from China, and

sell to him for eight hundred gold, plus the costs of importation.

Further, Fu Yee Po was even willing to take five hundred down and

the remainder on note at 6 per cent.

Ah Kim, thirty-seven years of age, fat and a bachelor, really did

want a wife, especially a small-footed wife; for, China born and

reared, the immemorial small-footed female had been deeply

impressed into his fantasy of woman. But more, even more and far

more than a small-footed wife, did he want his mother and his

mother’s delectable beatings. So he declined Fu Yee Po’s easy

terms, and at much less cost imported his own mother from servant

in a boss coolie’s house at a yearly wage of a dollar and a thirty-

cent dress to be mistress of his Honolulu three-story shack

building with two household servants, three clerks, and a porter of

all work under her, to say nothing of ten thousand dollars’ worth

of dress goods on the shelves that ranged from the cheapest cotton

crepes to the most expensive hand-embroidered silks. For be it

known that even in that early day Ah Kim’s emporium was beginning

to cater to the tourist trade from the States.

For thirteen years Ah Kim had lived tolerably happily with his

mother, and by her been methodically beaten for causes just or

unjust, real or fancied; and at the end of it all he knew as

strongly as ever the ache of his heart and head for a wife, and of

his loins for sons to live after him, and carry on the dynasty of

Ah Kim Company. Such the dream that has ever vexed men, from those

early ones who first usurped a hunting right, monopolized a sandbar

for a fish-trap, or stormed a village and put the males thereof to

the sword. Kings, millionaires, and Chinese merchants of Honolulu

have this in common, despite that they may praise God for having

made them differently and in self-likable images.

And the ideal of woman that Ah Kim at fifty ached for had changed

from his ideal at thirty-seven. No small-footed wife did he want

now, but a free, natural, out-stepping normal-footed woman that,

somehow, appeared to him in his day dreams and haunted his night

visions in the form of Li Faa, the Silvery Moon Blossom. What if

she were twice widowed, the daughter of a kanaka mother, the wearer

of white-devil skirts and corsets and high-heeled slippers! He

wanted her. It seemed it was written that she should be joint

ancestor with him of the line that would continue the ownership and

management through the generations, of Ah Kim Company, General

Merchandise.

“I will have no half-pake daughter-in-law,” his mother often

reiterated to Ah Kim, pake being the Hawaiian word for Chinese.

“All pake must my daughter-in-law be, even as you, my son, and as

I, your mother. And she must wear trousers, my son, as all the

women of our family before her. No woman, in she-devil skirts and

corsets, can pay due reverence to our ancestors. Corsets and

reverence do not go together. Such a one is this shameless Li Faa.

She is impudent and independent, and will be neither obedient to

her husband nor her husband’s mother. This brazen-faced Li Faa

would believe herself the source of life and the first ancestor,

recognizing no ancestors before her. She laughs at our joss-

sticks, and paper prayers, and family gods, as I have been well

told–“

“Mrs. Chang Lucy,” Ah Kim groaned.

“Not alone Mrs. Chang Lucy, O son. I have inquired. At least a

dozen have heard her say of our joss house that it is all monkey

foolishness. The words are hers–she, who eats raw fish, raw

squid, and baked dog. Ours is the foolishness of monkeys. Yet

would she marry you, a monkey, because of your store that is a

palace and of the wealth that makes you a great man. And she would

put shame on me, and on your father before you long honourably

dead.”

And there was no discussing the matter. As things were, Ah Kim

knew his mother was right. Not for nothing had Li Faa been born

forty years before of a Chinese father, renegade to all tradition,

and of a kanaka mother whose immediate forebears had broken the

taboos, cast down their own Polynesian gods, and weak-heartedly

listened to the preaching about the remote and unimageable god of

the Christian missionaries. Li Faa, educated, who could read and

write English and Hawaiian and a fair measure of Chinese, claimed

to believe in nothing, although in her secret heart she feared the

kahunas (Hawaiian witch-doctors), who she was certain could charm

away ill luck or pray one to death. Li Faa would never come into

Ah Kim’s house, as he thoroughly knew, and kow-tow to his mother

and be slave to her in the immemorial Chinese way. Li Faa, from

the Chinese angle, was a new woman, a feminist, who rode horseback

astride, disported immodestly garbed at Waikiki on the surf-boards,

and at more than one luau (feast) had been known to dance the hula

with the worst and in excess of the worst, to the scandalous

delight of all.

Ah Kim himself, a generation younger than his mother, had been

bitten by the acid of modernity. The old order held, in so far as

he still felt in his subtlest crypts of being the dusty hand of the

past resting on him, residing in him; yet he subscribed to heavy

policies of fire and life insurance, acted as treasurer for the

local Chinese revolutionises that were for turning the Celestial

Empire into a republic, contributed to the funds of the Hawaii-born

Chinese baseball nine that excelled the Yankee nines at their own

game, talked theosophy with Katso Suguri, the Japanese Buddhist and

silk importer, fell for police graft, played and paid his insidious

share in the democratic politics of annexed Hawaii, and was

thinking of buying an automobile. Ah Kim never dared bare himself

to himself and thrash out and winnow out how much of the old he had

ceased to believe in. His mother was of the old, yet he revered

her and was happy under her bamboo stick. Li Faa, the Silvery Moon

Blossom, was of the new, yet he could never be quite completely

happy without her.

For he loved Li Faa. Moon-faced, rotund as a water-melon seed,

canny business man, wise with half a century of living–

nevertheless Ah Kim became an artist when he thought of her. He

thought of her in poems of names, as woman transmuted into flower-

terms of beauty and philosophic abstractions of achievement and

easement. She was, to him, and alone to him of all men in the

world, his Plum Blossom, his Tranquillity of Woman, his Flower of

Serenity, his Moon Lily, and his Perfect Rest. And as he murmured

these love endearments of namings, it seemed to him that in them

were the ripplings of running waters, the tinklings of silver wind-

bells, and the scents of the oleander and the jasmine. She was his

poem of woman, a lyric delight, a three-dimensions of flesh and

spirit delicious, a fate and a good fortune written, ere the first

man and woman were, by the gods whose whim had been to make all men

and women for sorrow and for joy.

But his mother put into his hand the ink-brush and placed under it,

on the table, the writing tablet.

“Paint,” said she, “the ideograph of TO MARRY.”

He obeyed, scarcely wondering, with the deft artistry of his race

and training painting the symbolic hieroglyphic.

“Resolve it,” commanded his mother.

Ah Kim looked at her, curious, willing to please, unaware of the

drift of her intent.

“Of what is it composed?” she persisted. “What are the three

originals, the sum of which is it: to marry, marriage, the coming

together and wedding of a man and a woman? Paint them, paint them

apart, the three originals, unrelated, so that we may know how the

wise men of old wisely built up the ideograph of to marry.”

And Ah Kim, obeying and painting, saw that what he had painted were

three picture-signs–the picture-signs of a hand, an ear, and a

woman.

“Name them,” said his mother; and he named them.

“It is true,” said she. “It is a great tale. It is the stuff of

the painted pictures of marriage. Such marriage was in the

beginning; such shall it always be in my house. The hand of the

man takes the woman’s ear, and by it leads her away to his house,

where she is to be obedient to him and to his mother. I was taken

by the ear, so, by your long honourably dead father. I have looked

at your hand. It is not like his hand. Also have I looked at the

ear of Li Faa. Never will you lead her by the ear. She has not

that kind of an ear. I shall live a long time yet, and I will be

mistress in my son’s house, after our ancient way, until I die.”

“But she is my revered ancestress,” Ah Kim explained to Li Faa.

He was timidly unhappy; for Li Faa, having ascertained that Mrs.

Tai Fu was at the temple of the Chinese AEsculapius making a food

offering of dried duck and prayers for her declining health, had

taken advantage of the opportunity to call upon him in his store.

Li Faa pursed her insolent, unpainted lips into the form of a half-

opened rosebud, and replied:

“That will do for China. I do not know China. This is Hawaii, and

in Hawaii the customs of all foreigners change.”

“She is nevertheless my ancestress,” Ah Kim protested, “the mother

who gave me birth, whether I am in China or Hawaii, O Silvery Moon

Blossom that I want for wife.”

“I have had two husbands,” Li Faa stated placidly. “One was a

pake, one was a Portuguese. I learned much from both. Also am I

educated. I have been to High School, and I have played the piano

in public. And I learned from my two husbands much. The pake

makes the best husband. Never again will I marry anything but a

pake. But he must not take me by the ear–“

“How do you know of that?” he broke in suspiciously.

“Mrs. Chang Lucy,” was the reply. “Mrs. Chang Lucy tells me

everything that your mother tells her, and your mother tells her

much. So let me tell you that mine is not that kind of an ear.”

“Which is what my honoured mother has told me,” Ah Kim groaned.

“Which is what your honoured mother told Mrs. Chang Lucy, which is

what Mrs. Chang Lucy told me,” Li Faa completed equably. “And I

now tell you, O Third Husband To Be, that the man is not born who

will lead me by the ear. It is not the way in Hawaii. I will go

only hand in hand with my man, side by side, fifty-fifty as is the

haole slang just now. My Portuguese husband thought different. He

tried to beat me. I landed him three times in the police court and

each time he worked out his sentence on the reef. After that he

got drowned.”

“My mother has been my mother for fifty years,” Ah Kim declared

stoutly.

“And for fifty years has she beaten you,” Li Faa giggled. “How my

father used to laugh at Yap Ten Shin! Like you, Yap Ten Shin had

been born in China, and had brought the China customs with him.

His old father was for ever beating him with a stick. He loved his

father. But his father beat him harder than ever when he became a

missionary pake. Every time he went to the missionary services,

his father beat him. And every time the missionary heard of it he

was harsh in his language to Yap Ten Shin for allowing his father

to beat him. And my father laughed and laughed, for my father was

a very liberal pake, who had changed his customs quicker than most

foreigners. And all the trouble was because Yap Ten Shin had a

loving heart. He loved his honourable father. He loved the God of

Love of the Christian missionary. But in the end, in me, he found

the greatest love of all, which is the love of woman. In me he

forgot his love for his father and his love for the loving Christ.

“And he offered my father six hundred gold, for me–the price was

small because my feet were not small. But I was half kanaka. I

said that I was not a slave-woman, and that I would be sold to no

man. My high-school teacher was a haole old maid who said love of

woman was so beyond price that it must never be sold. Perhaps that

is why she was an old maid. She was not beautiful. She could not

give herself away. My kanaka mother said it was not the kanaka way

to sell their daughters for a money price. They gave their

daughters for love, and she would listen to reason if Yap Ten Shin

provided luaus in quantity and quality. My pake father, as I have

told you, was liberal. He asked me if I wanted Yap Ten Shin for my

husband. And I said yes; and freely, of myself, I went to him. He

it was who was kicked by a horse; but he was a very good husband

before he was kicked by the horse.

“As for you, Ah Kim, you shall always be honourable and lovable for

me, and some day, when it is not necessary for you to take me by

the ear, I shall marry you and come here and be with you always,

and you will be the happiest pake in all Hawaii; for I have had two

husbands, and gone to high school, and am most wise in making a

husband happy. But that will be when your mother has ceased to

beat you. Mrs. Chang Lucy tells me that she beats you very hard.”

“She does,” Ah Kim affirmed. “Behold! He thrust back his loose

sleeves, exposing to the elbow his smooth and cherubic forearms.

They were mantled with black and blue marks that advertised the

weight and number of blows so shielded from his head and face.

“But she has never made me cry,” Ah Kim disclaimed hastily.

“Never, from the time I was a little boy, has she made me cry.”

“So Mrs. Chang Lucy says,” Li Faa observed. “She says that your

honourable mother often complains to her that she has never made

you cry.”

A sibilant warning from one of his clerks was too late. Having

regained the house by way of the back alley, Mrs. Tai Fu emerged

right upon them from out of the living apartments. Never had Ah

Kim seen his mother’s eyes so blazing furious. She ignored Li Faa,

as she screamed at him:

“Now will I make you cry. As never before shall I beat you until

you do cry.”

“Then let us go into the back rooms, honourable mother,” Ah Kim

suggested. “We will close the windows and the doors, and there may

you beat me.”

“No. Here shall you be beaten before all the world and this

shameless woman who would, with her own hand, take you by the ear

and call such sacrilege marriage! Stay, shameless woman.”

“I am going to stay anyway,” said Li Faa. She favoured the clerks

with a truculent stare. “And I’d like to see anything less than

the police put me out of here.”

“You will never be my daughter-in-law,” Mrs. Tai Fu snapped.

Li Faa nodded her head in agreement.

“But just the same,” she added, “shall your son be my third

husband.”

“You mean when I am dead?” the old mother screamed.

“The sun rises each morning,” Li Faa said enigmatically. “All my

life have I seen it rise–“

“You are forty, and you wear corsets.”

“But I do not dye my hair–that will come later,” Li Faa calmly

retorted. “As to my age, you are right. I shall be forty-one next

Kamehameha Day. For forty years I have seen the sun rise. My

father was an old man. Before he died he told me that he had

observed no difference in the rising of the sun since when he was a

little boy. The world is round. Confucius did not know that, but

you will find it in all the geography books. The world is round.

Ever it turns over on itself, over and over and around and around.

And the times and seasons of weather and life turn with it. What

is, has been before. What has been, will be again. The time of

the breadfruit and the mango ever recurs, and man and woman repeat

themselves. The robins nest, and in the springtime the plovers

come from the north. Every spring is followed by another spring.

The coconut palm rises into the air, ripens its fruit, and departs.

But always are there more coconut palms. This is not all my own

smart talk. Much of it my father told me. Proceed, honourable

Mrs. Tai Fu, and beat your son who is my Third Husband To Be. But

I shall laugh. I warn you I shall laugh.”

Ah Kim dropped down on his knees so as to give his mother every

advantage. And while she rained blows upon him with the bamboo

stick, Li Faa smiled and giggled, and finally burst into laughter.

“Harder, O honourable Mrs. Tai Fu!” Li Faa urged between paroxysms

of mirth.

Mrs. Tai Fu did her best, which was notably weak, until she

observed what made her drop the stick by her side in amazement. Ah

Kim was crying. Down both cheeks great round tears were coursing.

Li Faa was amazed. So were the gaping clerks. Most amazed of all

was Ah Kim, yet he could not help himself; and, although no further

blows fell, he cried steadily on.

“But why did you cry?” Li Faa demanded often of Ah Kim. “It was so

perfectly foolish a thing to do. She was not even hurting you.”

“Wait until we are married,” was Ah Kim’s invariable reply, “and

then, O Moon Lily, will I tell you.”

Two years later, one afternoon, more like a water-melon seed in

configuration than ever, Ah Kim returned home from a meeting of the

Chinese Protective Association, to find his mother dead on her

couch. Narrower and more unrelenting than ever were the forehead

and the brushed-back hair. But on her face was a withered smile.

The gods had been kind. She had passed without pain.

He telephoned first of all to Li Faa’s number but did not find her

until he called up Mrs. Chang Lucy. The news given, the marriage

was dated ahead with ten times the brevity of the old-line Chinese

custom. And if there be anything analogous to a bridesmaid in a

Chinese wedding, Mrs. Chang Lucy was just that.

“Why,” Li Faa asked Ah Kim when alone with him on their wedding

night, “why did you cry when your mother beat you that day in the

store? You were so foolish. She was not even hurting you.”

“That is why I cried,” answered Ah Kim.

Li Faa looked up at him without understanding.

“I cried,” he explained, “because I suddenly knew that my mother

was nearing her end. There was no weight, no hurt, in her blows.

I cried because I knew SHE NO LONGER HAD STRENGTH ENOUGH TO HURT

ME. That is why I cried, my Flower of Serenity, my Perfect Rest.

That is the only reason why I cried.”

WAIKIKI, HONOLULU.

June 16, 1916.

From Jack London: ON THE MAKALOA MAT/ISLAND TALES

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, London, Jack

Jack London

(1876-1916)

Shin-Bones

They have gone down to the pit with their weapons of war, and they have laid their swords under their heads.

“It was a sad thing to see the old lady revert.”

Prince Akuli shot an apprehensive glance sideward to where, under the shade of a kukui tree, an old wahine (Hawaiian woman) was just settling herself to begin on some work in hand.

“Yes,” he nodded half-sadly to me, “in her last years Hiwilani went back to the old ways, and to the old beliefs–in secret, of course. And, BELIEVE me, she was some collector herself. You should have seen her bones. She had them all about her bedroom, in big jars, and they constituted most all her relatives, except a half-dozen or so that Kanau beat her out of by getting to them first. The way the pair of them used to quarrel about those bones was aweinspiring. And it gave me the creeps, when I was a boy, to go into that big, for-ever-twilight room of hers, and know that in this jar was all that remained of my maternal grand-aunt, and that in that jar was my great-grandfather, and that in all the jars were the preserved bone-remnants of the shadowy dust of the ancestors whose seed had come down and been incorporated in the living, breathing me. Hiwilani had gone quite native at the last, sleeping on mats on the hard floor–she’d fired out of the room the great, royal, canopied four-poster that had been presented to her grandmother by Lord Byron, who was the cousin of the Don Juan Byron and came here in the frigate Blonde in 1825.

“She went back to all native, at the last, and I can see her yet, biting a bite out of the raw fish ere she tossed them to her women to eat. And she made them finish her poi, or whatever else she did not finish of herself. She–“

But he broke off abruptly, and by the sensitive dilation of his nostrils and by the expression of his mobile features I saw that he had read in the air and identified the odour that offended him.

“Deuce take it!” he cried to me. “It stinks to heaven. And I shall be doomed to wear it until we’re rescued.”

There was no mistaking the object of his abhorrence. The ancient crone was making a dearest-loved lei (wreath) of the fruit of the hala which is the screw-pine or pandanus of the South Pacific. She was cutting the many sections or nut-envelopes of the fruit into fluted bell-shapes preparatory to stringing them on the twisted and tough inner bark of the hau tree. It certainly smelled to heaven, but, to me, a malahini (new-comer), the smell was wine-woody and fruit-juicy and not unpleasant.

Prince Akuli’s limousine had broken an axle a quarter of a mile away, and he and I had sought shelter from the sun in this veritable bowery of a mountain home. Humble and grass-thatched was the house, but it stood in a treasure-garden of begonias that sprayed their delicate blooms a score of feet above our heads, that were like trees, with willowy trunks of trees as thick as a man’s arm. Here we refreshed ourselves with drinking-coconuts, while a cowboy rode a dozen miles to the nearest telephone and summoned a machine from town. The town itself we could see, the Lakanaii metropolis of Olokona, a smudge of smoke on the shore-line, as we looked down across the miles of cane-fields, the billow-wreathed reef-lines, and the blue haze of ocean to where the island of Oahu shimmered like a dim opal on the horizon.

Maui is the Valley Isle of Hawaii, and Kauai the Garden Isle; but Lakanaii, lying abreast of Oahu, is recognized in the present, and was known of old and always, as the Jewel Isle of the group. Not the largest, nor merely the smallest, Lakanaii is conceded by all to be the wildest, the most wildly beautiful, and, in its size, the richest of all the islands. Its sugar tonnage per acre is the highest, its mountain beef-cattle the fattest, its rainfall the most generous without ever being disastrous. It resembles Kauai in that it is the first-formed and therefore the oldest island, so that it had had time sufficient to break down its lava rock into the richest soil, and to erode the canyons between the ancient craters until they are like Grand Canyons of the Colorado, with numberless waterfalls plunging thousands of feet in the sheer or dissipating into veils of vapour, and evanescing in mid-air to descend softly and invisibly through a mirage of rainbows, like so much dew or gentle shower, upon the abyss-floors.

Yet Lakanaii is easy to describe. But how can one describe Prince Akuli? To know him is to know all Lakanaii most thoroughly. In addition, one must know thoroughly a great deal of the rest of the world. In the first place, Prince Akuli has no recognized nor legal right to be called “Prince.” Furthermore, “Akuli” means the “squid.” So that Prince Squid could scarcely be the dignified title of the straight descendant of the oldest and highest aliis (high chiefs) of Hawaii–an old and exclusive stock, wherein, in the ancient way of the Egyptian Pharaohs, brothers and sisters had even wed on the throne for the reason that they could not marry beneath rank, that in all their known world there was none of higher rank, and that, at every hazard, the dynasty must be perpetuated.

I have heard Prince Akuli’s singing historians (inherited from his father) chanting their interminable genealogies, by which they demonstrated that he was the highest alii in all Hawaii. Beginning with Wakea, who is their Adam, and with Papa, their Eve, through as many generations as there are letters in our alphabet they trace down to Nanakaoko, the first ancestor born in Hawaii and whose wife was Kahihiokalani. Later, but always highest, their generations split from the generations of Ua, who was the founder of the two distinct lines of the Kauai and Oahu kings.

In the eleventh century A.D., by the Lakanaii historians, at the time brothers and sisters mated because none existed to excel them, their rank received a boost of new blood of rank that was next to heaven’s door. One Hoikemaha, steering by the stars and the ancient traditions, arrived in a great double-canoe from Samoa. He married a lesser alii of Lakanaii, and when his three sons were grown, returned with them to Samoa to bring back his own youngest brother. But with him he brought back Kumi, the son of Tui Manua, which latter’s rank was highest in all Polynesia, and barely second to that of the demigods and gods. So the estimable seed of Kumi, eight centuries before, had entered into the aliis of Lakanaii, and been passed down by them in the undeviating line to reposit in Prince Akuli.

Him I first met, talking with an Oxford accent, in the officers’ mess of the Black Watch in South Africa. This was just before that famous regiment was cut to pieces at Magersfontein. He had as much right to be in that mess as he had to his accent, for he was Oxford-educated and held the Queen’s Commission. With him, as his guest, taking a look at the war, was Prince Cupid, so nicknamed, but the true prince of all Hawaii, including Lakanaii, whose real and legal title was Prince Jonah Kuhio Kalanianaole, and who might have been the living King of Hawaii Nei had it not been for the haole (white man) Revolution and Annexation–this, despite the fact that Prince Cupid’s alii genealogy was lesser to the heaven-boosted genealogy of Prince Akuli. For Prince Akuli might have been King of Lakanaii, and of all Hawaii, perhaps, had not his grandfather been soundly thrashed by the first and greatest of the Kamehamehas.

This had occurred in the year 1810, in the booming days of the sandalwood trade, and in the same year that the King of Kauai came in, and was good, and ate out of Kamehameha’s hand. Prince Akuli’s grandfather, in that year, had received his trouncing and subjugating because he was “old school.” He had not imaged island empire in terms of gunpowder and haole gunners. Kamehameha, farther-visioned, had annexed the service of haoles, including such men as Isaac Davis, mate and sole survivor of the massacred crew of the schooner Fair American, and John Young, captured boatswain of the snow Eleanor. And Isaac Davis, and John Young, and others of their waywardly adventurous ilk, with six-pounder brass carronades from the captured Iphigenia and Fair American, had destroyed the war canoes and shattered the morale of the King of Lakanaii’s landfighters, receiving duly in return from Kamehameha, according to agreement: Isaac Davis, six hundred mature and fat hogs; John Young, five hundred of the same described pork on the hoof that was split.

And so, out of all incests and lusts of the primitive cultures and beast-man’s gropings toward the stature of manhood, out of all red murders, and brute battlings, and matings with the younger brothersof the demigods, world-polished, Oxford-accented, twentieth century to the tick of the second, comes Prince Akuli, Prince Squid, pure-veined Polynesian, a living bridge across the thousand centuries, comrade, friend, and fellow-traveller out of his wrecked seven-thousand-dollar limousine, marooned with me in a begonia paradise fourteen hundred feet above the sea, and his island metropolis of Olokona, to tell me of his mother, who reverted in her old age to ancientness of religious concept and ancestor worship, and collected and surrounded herself with the charnel bones of those who had been her forerunners back in the darkness of time.

“King Kalakaua started this collecting fad, over on Oahu,” Prince Akuli continued. “And his queen, Kapiolani, caught the fad from him. They collected everything–old makaloa mats, old tapas, old calabashes, old double-canoes, and idols which the priests had saved from the general destruction in 1819. I haven’t seen a pearl-shell fish-hook in years, but I swear that Kalakaua accumulated ten thousand of them, to say nothing of human jaw-bone fish-hooks, and feather cloaks, and capes and helmets, and stone adzes, and poi-pounders of phallic design. When he and Kapiolani made their royal progresses around the islands, their hosts had to hide away their personal relics. For to the king, in theory, belongs all property of his people; and with Kalakaua, when it came to the old things, theory and practice were one.

“From him my father, Kanau, got the collecting bee in his bonnet, and Hiwilani was likewise infected. But father was modern to his finger-tips. He believed neither in the gods of the kahunas” (priests) “nor of the missionaries. He didn’t believe in anything except sugar stocks, horse-breeding, and that his grandfather had been a fool in not collecting a few Isaac Davises and John Youngs and brass carronades before he went to war with Kamehameha. So he collected curios in the pure collector’s spirit; but my mother took it seriously. That was why she went in for bones. I remember, too, she had an ugly old stone-idol she used to yammer to and crawl around on the floor before. It’s in the Deacon Museum now. I sent it there after her death, and her collection of bones to the Royal Mausoleum in Olokona.

“I don’t know whether you remember her father was Kaaukuu. Well, he was, and he was a giant. When they built the Mausoleum, his bones, nicely cleaned and preserved, were dug out of their hidingplace, and placed in the Mausoleum. Hiwilani had an old retainer, Ahuna. She stole the key from Kanau one night, and made Ahuna go and steal her father’s bones out of the Mausoleum. I know. And he must have been a giant. She kept him in one of her big jars. One day, when I was a tidy size of a lad, and curious to know if Kaaukuu was as big as tradition had him, I fished his intact lower jaw out of the jar, and the wrappings, and tried it on. I stuck my head right through it, and it rested around my neck and on my shoulders like a horse collar. And every tooth was in the jaw, whiter than porcelain, without a cavity, the enamel unstained and unchipped. I got the walloping of my life for that offence, although she had to call old Ahuna in to help give it to me. But the incident served me well. It won her confidence in me that I was not afraid of the bones of the dead ones, and it won for me my Oxford education. As you shall see, if that car doesn’t arrive first.

“Old Ahuna was one of the real old ones with the hall-mark on him and branded into him of faithful born-slave service. He knew more about my mother’s family, and my father’s, than did both of them put together. And he knew, what no living other knew, the burial-place of centuries, where were hid the bones of most of her ancestors and of Kanau’s. Kanau couldn’t worm it out of the old fellow, who looked upon Kanau as an apostate.

“Hiwilani struggled with the old codger for years. How she ever succeeded is beyond me. Of course, on the face of it, she was faithful to the old religion. This might have persuaded Ahuna to loosen up a little. Or she may have jolted fear into him; for she knew a lot of the line of chatter of the old Huni sorcerers, and she could make a noise like being on terms of utmost intimacy with Uli, who is the chiefest god of sorcery of all the sorcerers. She could skin the ordinary kahuna lapaau” (medicine man) “when it came to praying to Lonopuha and Koleamoku; read dreams and visions and signs and omens and indigestions to beat the band; make the practitioners under the medicine god, Maiola, look like thirty cents; pull off a pule hee incantation that would make them dizzy; and she claimed to a practice of kahuna hoenoho, which is modern spiritism, second to none. I have myself seen her drink the wind, throw a fit, and prophesy. The aumakuas were brothers to her when she slipped offerings to them across the altars of the ruined heiaus” (temples) “with a line of prayer that was as unintelligible to me as it was hair-raising. And as for old Ahuna, she could make him get down on the floor and yammer and bite himself when she pulled the real mystery dope on him.

“Nevertheless, my private opinion is that it was the anaana stuff that got him. She snipped off a lock of his hair one day with a pair of manicure scissors. This lock of hair was what we call the maunu, meaning the bait. And she took jolly good care to let him know she had that bit of his hair. Then she tipped it off to him that she had buried it, and was deeply engaged each night in her offerings and incantations to Uli.”

“That was the regular praying-to-death?” I queried in the pause of Prince Akuli’s lighting his cigarette.

“Sure thing,” he nodded. “And Ahuna fell for it. First he tried to locate the hiding-place of the bait of his hair. Failing that, he hired a pahiuhiu sorcerer to find it for him. But Hiwilani queered that game by threatening to the sorcerer to practise apo leo on him, which is the art of permanently depriving a person of the power of speech without otherwise injuring him.

“Then it was that Ahuna began to pine away and get more like a corpse every day. In desperation he appealed to Kanau. I happened to be present. You have heard what sort of a man my father was.

“‘Pig!’ he called Ahuna. ‘Swine-brains! Stinking fish! Die and be done with it. You are a fool. It is all nonsense. There is nothing in anything. The drunken haole, Howard, can prove the missionaries wrong. Square-face gin proves Howard wrong. The doctors say he won’t last six months. Even square-face gin lies.

Life is a liar, too. And here are hard times upon us, and a slump in sugar. Glanders has got into my brood mares. I wish I could lie down and sleep for a hundred years, and wake up to find sugar up a hundred points.’

“Father was something of a philosopher himself, with a bitter wit and a trick of spitting out staccato epigrams. He clapped his hands. ‘Bring me a high-ball,’ he commanded; ‘no, bring me two high-balls.’ Then he turned on Ahuna. ‘Go and let yourself die, old heathen, survival of darkness, blight of the Pit that you are. But don’t die on these premises. I desire merriment and laughter, and the sweet tickling of music, and the beauty of youthful motion,

not the croaking of sick toads and googly-eyed corpses about me still afoot on their shaky legs. I’ll be that way soon enough if I live long enough. And it will be my everlasting regret if I don’t live long enough. Why in hell did I sink that last twenty thousand into Curtis’s plantation? Howard warned me the slump was coming, but I thought it was the square-face making him lie. And Curtis has blown his brains out, and his head luna has run away with his daughter, and the sugar chemist has got typhoid, and everything’s going to smash.’

“He clapped his hands for his servants, and commanded: ‘Bring me my singing boys. And the hula dancers–plenty of them. And send for old Howard. Somebody’s got to pay, and I’ll shorten his six months of life by a month. But above all, music. Let there be music. It is stronger than drink, and quicker than opium.’

“He with his music druggery! It was his father, the old savage, who was entertained on board a French frigate, and for the first time heard an orchestra. When the little concert was over, the captain, to find which piece he liked best, asked which piece he’d like repeated. Well, when grandfather got done describing, what piece do you think it was?”

I gave up, while the Prince lighted a fresh cigarette.

“Why, it was the first one, of course. Not the real first one, but the tuning up that preceded it.”

I nodded, with eyes and face mirthful of appreciation, and Prince Akuli, with another apprehensive glance at the old wahine and her half-made hala lei, returned to his tale of the bones of his ancestors.

“It was somewhere around this stage of the game that old Ahuna gave in to Hiwilani. He didn’t exactly give in. He compromised. That’s where I come in. If he would bring her the bones of her mother, and of her grandfather (who was the father of Kaaukuu, and who by tradition was rumoured to have been even bigger than his giant son, she would return to Ahuna the bait of his hair she was praying him to death with. He, on the other hand, stipulated that he was not to reveal to her the secret burial-place of all the alii of Lakanaii all the way back. Nevertheless, he was too old to dare the adventure alone, must be helped by some one who of necessity would come to know the secret, and I was that one. I was the highest alii, beside my father and mother, and they were no higher than I.

“So I came upon the scene, being summoned into the twilight room to confront those two dubious old ones who dealt with the dead. They were a pair–mother fat to despair of helplessness, Ahuna thin as a skeleton and as fragile. Of her one had the impression that if she lay down on her back she could not roll over without the aid of block-and-tackle; of Ahuna one’s impression was that the tooth-pickedness of him would shatter to splinters if one bumped into him.