Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

The Song of the Wreck

The wind blew high, the waters raved,

A ship drove on the land,

A hundred human creatures saved

Kneel’d down upon the sand.

Three-score were drown’d, three-score were thrown

Upon the black rocks wild,

And thus among them, left alone,

They found one helpless child.

A seaman rough, to shipwreck bred,

Stood out from all the rest,

And gently laid the lonely head

Upon his honest breast.

And travelling o’er the desert wide

It was a solemn joy,

To see them, ever side by side,

The sailor and the boy.

In famine, sickness, hunger, thirst,

The two were still but one,

Until the strong man droop’d the first

And felt his labours done.

Then to a trusty friend he spake,

“Across the desert wide,

O take this poor boy for my sake!”

And kiss’d the child and died.

Toiling along in weary plight

Through heavy jungle, mire,

These two came later every night

To warm them at the fire.

Until the captain said one day,

“O seaman good and kind,

To save thyself now come away,

And leave the boy behind!”

The child was slumbering near the blaze:

“O captain, let him rest

Until it sinks, when God’s own ways

Shall teach us what is best!”

They watch’d the whiten’d ashy heap,

They touch’d the child in vain;

They did not leave him there asleep,

He never woke again.

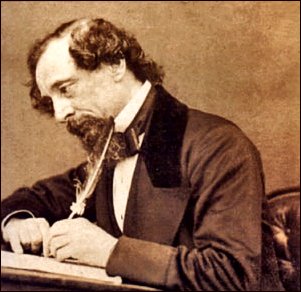

Charles Dickens

(1812-1870)

The Song of the Wreck

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Archive C-D, Charles Dickens, Dickens, Charles

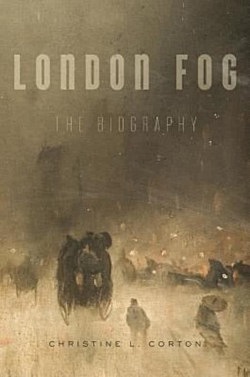

In popular imagination, London is a city of fog. The classic London fogs, the thick yellow “pea-soupers,” were born in the industrial age of the early nineteenth century.

The first globally notorious instance of air pollution, they remained a constant feature of cold, windless winter days until clean air legislation in the 1960s brought about their demise. Christine L. Corton tells the story of these epic London fogs, their dangers and beauty, and their lasting effects on our culture and imagination.

The first globally notorious instance of air pollution, they remained a constant feature of cold, windless winter days until clean air legislation in the 1960s brought about their demise. Christine L. Corton tells the story of these epic London fogs, their dangers and beauty, and their lasting effects on our culture and imagination.

As the city grew, smoke from millions of domestic fires, combined with industrial emissions and naturally occurring mists, seeped into homes, shops, and public buildings in dark yellow clouds of water droplets, soot, and sulphur dioxide. The fogs were sometimes so thick that people could not see their own feet.

By the time London’s fogs lifted in the second half of the twentieth century, they had changed urban life. Fogs had created worlds of anonymity that shaped social relations, providing a cover for crime, and blurring moral and social boundaries.

They had been a gift to writers, appearing famously in the works of Charles Dickens, Henry James, Oscar Wilde, Robert Louis Stevenson, Joseph Conrad, and T. S. Eliot. Whistler and Monet painted London fogs with a fascination other artists reserved for the clear light of the Mediterranean.

Corton combines historical and literary sensitivity with an eye for visual drama—generously illustrated here—to reveal London fog as one of the great urban spectacles of the industrial age.

Christine L. Corton is a Senior Member of Wolfson College, Cambridge, and a freelance writer. She worked for many years at publishing houses in London.

London Fog

The Biography

Christine L. Corton

Paperback – 2017

408 pages

28 color illustrations, 63 halftones

Belknap Press / Harvard University Press

ISBN 9780674979819

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Book Stories, Archive C-D, Art & Literature News, Arthur Conan Doyle, Charles Dickens, Eliot, T. S., FDM in London, Natural history, Tales of Mystery & Imagination

Don Marquis

(1878 – 1937)

Dickens

“The only book that the party had was a volume of Dickens.

During the six months that they lay in the cave which they

had hacked in the ice, waiting for spring to come, they read

this volume through again and again.”—From a

newspaper report of an antarctic expedition.

Huddled within their savage lair

They hearkened to the prowling wind;

They heard the loud wings of despair . . .

And madness beat against the mind. . . .

A sunless world stretched stark outside

As if it had cursed God and died;

Dumb plains lay prone beneath the weight

Of cold unutterably great;

Iron ice bound all the bitter seas,

The brutal hills were bleak as hate. . . .

Here none but Death might walk at ease!

Then Dickens spoke, and, lo! the vast

Unpeopled void stirred into life;

The dead world quickened, the mad blast

Hushed for an hour its idiot strife

With nothingness. . . .

And from the gloom,

Parting the flaps of frozen skin,

Old friends and dear came trooping in,

And light and laughter filled the room. . . .

Voices and faces, shapes beloved,

Babbling lips and kindly eyes,

Not ghosts, but friends that lived and moved . . .

They brought the sun from other skies,

They wrought the magic that dispels

The bitterer part of loneliness . . .

And when they vanished each man dreamed

His dream there in the wilderness. . . .

One heard the chime of Christmas bells,

And, staring down a country lane,

Saw bright against the window-pane

The firelight beckon warm and red. . . .

And one turned from the waterside

Where Thames rolls down his slothful tide

To breast the human sea that beats

Through roaring London’s battered streets

And revel in the moods of men. . . .

And one saw all the April hills

Made glad with golden daffodils,

And found and kissed his love again. . . .

. . . . . .

By all the troubled hearts he cheers

In homely ways or by lost trails,

By all light shed through all dark years

When hope grows sick and courage quails,

We hail him first among his peers;

Whether we sorrow, sing, or feast,

He, too, hath known and understood—

Master of many moods, high priest

Of mirth and lord of cleansing tears!

Don Marquis poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive M-N, Charles Dickens, CLASSIC POETRY

Charles Dickens

Literatuur als bron van kennis

We kennen Charles Dickens als chroniqueur van het negentiende-eeuwse Engeland, met steeds opnieuw uitgegeven en verfilmde werken als Oliver Twist, Hard Times en Bleak House. Zijn eigen leven leest ook als een roman, doorspekt met figuren die verwant zijn met personages uit zijn werk.

Het vroege werk van Dickens, waarin hij de ellende van gevangenissen en armenhuizen tot in detail beschreef, had een enorme impact op de Engelse maatschappij. Ook nu nog levert het lezen van die boeken belangrijke inzichten over de inrichting van de maatschappij en hoe die inwerkt op individuele levens. Later schreef Dickens meer autobiografisch. Met een kritische maar zachtaardige pen beschreef hij de mens, niet alleen als persoonlijkheid, maar ook juist in zijn sociale rol. Artsen, juristen, dominees, maar ook historici en sociale wetenschappers kunnen daar veel van opsteken. Daarom wordt volgens het klassieke ideaal van de academie literatuur lezen aanbevolen. Juist kennis van cultuur en geschiedenis kan onze blik scherpen.

Prof. mr. Jan Lokin (Rechtsgeschiedenis, UU) toont in vier lezingen over het werk van de Engelse schrijver Charles Dickens hoe literatuur kan werken als bron van mensenkennis en begrip van de wereld.

Programma

DINSDAG 11 OKTOBER

Het leven van Dickens

DINSDAG 18 OKTOBER

De vroege werken

DINSDAG 25 OKTOBER

Latere romans

DINSDAG 1 NOVEMBER

Engeland, Amerika en Kerstmis

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: BIOGRAPHY, Charles Dickens

.jpg)

Charles Dickens

(1812-1870)

Little Nell’s Funeral

And now the bell, — the bell

She had so often heard by night and day

And listened to with solemn pleasure,

E’en as a living voice, —

Rung its remorseless toll for her,

So young, so beautiful, so good.

Decrepit age, and vigorous life,

And blooming youth, and helpless infancy,

Poured forth, — on crutches, in the pride of strength

And health, in the full blush

Of promise, the mere dawn of life, —

To gather round her tomb. Old men were there,

Whose eyes were dim

And senses failing, —

Grandames, who might have died ten years ago,

And still been old, — the deaf, the blind, the lame,

The palsied,

The living dead in many shapes and forms,

To see the closing of this early grave.

What was the death it would shut in,

To that which still could crawl and keep above it!

Along the crowded path they bore her now;

Pure as the new fallen snow

That covered it; whose day on earth

Had been as fleeting.

Under that porch, where she had sat when Heaven

In mercy brought her to that peaceful spot,

She passed again, and the old church

Received her in its quiet shade.

They carried her to one old nook,

Where she had many and many a time sat musing,

And laid their burden softly on the pavement.

The light streamed on it through

The colored window, — a window where the boughs

Of trees were ever rustling

In the summer, and where the birds

Sang sweetly all day long.

.jpg)

Charles Dickens poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Charles Dickens, Dickens, Charles

.jpg)

Charles Dickens

(1812-1870)

Squire Norton’s Song

HE child and the old man sat alone

In the quiet, peaceful shade

Of the old green boughs, that had richly grown

In the deep, thick forest glade.

It was a soft and pleasant sound,

That rustling of the oak;

And the gentle breeze played lightly round

As thus the fair boy spoke:–

"Dear father, what can honor be,

Of which I hear men rave?

Field, cell and cloister, land and sea,

The tempest and the grave:–

It lives in all, ’tis sought in each,

‘Tis never heard or seen:

Now tell me, father, I beseech,

What can this honor mean?"

"It is a name — a name, my child —

It lived in other days,

When men were rude, their passions wild,

Their sport, thick battle-frays.

When, in armor bright, the warrior bold

Knelt to his lady’s eyes:

Beneath the abbey pavement old

That warrior’s dust now lies.

"The iron hearts of that old day

Have mouldered in the grave;

And chivalry has passed away,

With knights so true and brave;

The honor, which to them was life,

Throbs in no bosom now;

It only gilds the gambler’s strife,

Or decks the worthless vow."

.jpg)

Charles Dickens poetry

kempis.nl = kempis poetry magazine

More in: Charles Dickens, Dickens, Charles

.jpg)

Charles Dickens

(1812-1870)

Lucy’s Song

How beautiful at eventide

To see the twilight shadows pale,

Steal o’er the landscape, far and wide,

O’er stream and meadow, mound and dale!

How soft is Nature’s calm repose

When ev’ning skies their cool dews weep:

The gentlest wind more gently blows,

As if to soothe her in her sleep!

The gay morn breaks,

Mists roll away,

All Nature awakes

To glorious day.

In my breast alone

Dark shadows remain;

The peace it has known

It can never regain.

.jpg)

Charles Dickens poetry

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Charles Dickens, Dickens, Charles

C h a r l e s D i c k e n s

(1812-1870)

George Edmund’s Song

Autumn leaves, autumn leaves, lie strewn around he here;

Autumn leaves, autumn leaves, how sad, how cold, how drear!

How like the hopes of childhood’s day,

Thick clust’ring on the bough!

How like those hopes in their decay–

How faded are they now!

Autumn leaves, autumn leaves, lie strewn around me here;

Autumn leaves, autumn leaves, how sad, how cold, how drear!

Wither’d leaves, wither’d leaves, that fly before the gale:

Withered leaves, withered leaves, ye tell a mournful tale,

Of love once true, and friends once kind,

And happy moments fled:

Dispersed by every breath of wind,

Forgotten, changed, or dead!

Autumn leaves, autumn leaves, lie strewn around me here!

Autumn leaves, autumn leaves, how sad, how cold, how drear!

.jpg)

Charles Dickens poetry

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Charles Dickens, Dickens, Charles

.jpg)

Charles Dickens

(1812-1870)

The Song of the Wreck

THE wind blew high, the waters raved,

A ship drove on the land,

A hundred human creatures saved

Kneel’d down upon the sand.

Threescore were drown’d, threescore were thrown

Upon the black rocks wild,

And thus among them, left alone,

They found one helpless child.

A seaman rough, to shipwreck bred,

Stood out from all the rest,

And gently laid the lonely head

Upon his honest breast.

And travelling o’er the desert wide

It was a solemn joy,

To see them, ever side by side,

The sailor and the boy.

In famine, sickness, hunger, thirst,

The two were still but one,

Until the strong man droop’d the first

And felt his labors done.

Then to a trusty friend he spake,

"Across the desert wide,

Oh, take this poor boy for my sake!"

And kiss’d the child and died.

Toiling along in weary plight

Through heavy jungle, mire,

These two came later every night

To warm them at the fire.

Until the captain said one day

"O seaman, good and kind,

To save thyself now come away,

And leave the boy behind!"

The child was slumbering near the blaze:

"O captain, let him rest

Until it sinks, when God’s own ways

Shall teach us what is best!"

They watch’d the whiten’d, ashy heap,

They touch’d the child in vain;

They did not leave him there asleep,

He never woke again.

.jpg)

Charles Dickens poetry

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Charles Dickens, Dickens, Charles

.jpg)

Charles Dickens

(1812-1870)

A Child’s Hymn

Hear my prayer, O heavenly Father,

Ere I lay me down to sleep;

Bid Thy angels, pure and holy,

Round my bed their vigil keep.

My sins are heavy, but Thy mercy

Far outweighs them, every one;

Down before Thy cross I cast them,

Trusting in Thy help alone.

Keep me through this night of peril

Underneath its boundless shade;

Take me to Thy rest, I pray Thee,

When my pilgrimage is made.

None shall measure out Thy patience

By the span of human thought;

None shall bound the tender mercies

Which Thy Holy Son has bought.

Pardon all my past transgressions,

Give me strength for days to come;

Guide and guard me with Thy blessing

Till Thy angels bid me home.

Charles Dickens poetry

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Charles Dickens, Dickens, Charles

.jpg)

Charles Dickens

(1812-1870)

A fine Old English Gentleman

I’ll sing you a new ballad, and I’ll warrant it first-rate,

Of the days of that old gentleman who had that old estate;

When they spent the public money at a bountiful old rate

On ev’ry mistress, pimp, and scamp, at ev’ry noble gate,

In the fine old English Tory times;

Soon may they come again!

The good old laws were garnished well with gibbets, whips, and chains,

With fine old English penalties, and fine old English pains,

With rebel heads, and seas of blood once hot in rebel veins;

For all these things were requisite to guard the rich old gains

Of the fine old English Tory times;

Soon may they come again!

This brave old code, like Argus, had a hundred watchful eyes,

And ev’ry English peasant had his good old English spies,

To tempt his starving discontent with fine old English lies,

Then call the good old Yeomanry to stop his peevish cries,

In the fine old English Tory times;

Soon may they come again!

The good old times for cutting throats that cried out in their need,

The good old times for hunting men who held their fathers’ creed,

The good old times when William Pitt, as all good men agreed,

Came down direct from Paradise at more than railroad speed. . . .

Oh the fine old English Tory times;

When will they come again!

In those rare days, the press was seldom known to snarl or bark,

But sweetly sang of men in pow’r, like any tuneful lark;

Grave judges, too, to all their evil deeds were in the dark;

And not a man in twenty score knew how to make his mark.

Oh the fine old English Tory times;

Soon may they come again!

Those were the days for taxes, and for war’s infernal din;

For scarcity of bread, that fine old dowagers might win;

For shutting men of letters up, through iron bars to grin,

Because they didn’t think the Prince was altogether thin,

In the fine old English Tory times;

Soon may they come again!

But Tolerance, though slow in flight, is strong-wing’d in the main;

That night must come on these fine days, in course of time was plain;

The pure old spirit struggled, but Its struggles were in vain;

A nation’s grip was on it, and it died in choking pain,

With the fine old English Tory days,

All of the olden time.

The bright old day now dawns again; the cry runs through the land,

In England there shall be dear bread — in Ireland, sword and brand;

And poverty, and ignorance, shall swell the rich and grand,

So, rally round the rulers with the gentle iron hand,

Of the fine old English Tory days; Hail to the coming time!

.jpg)

Charles Dickens poetry

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Charles Dickens, Dickens, Charles

.jpg)

Charles Dickens

(1812-1870)

The Ivy Green

Oh, a dainty plant is the Ivy green,

That creepeth o’er ruins old!

Of right choice food are his meals, I ween,

In his cell so lone and cold.

The wall must be crumbled, the stone decayed,

To pleasure his dainty whim:

And the mouldering dust that years have made

Is a merry meal for him.

Creeping where no life is seen,

A rare old plant is the Ivy green.

Fast he stealeth on, though he wears no wings,

And a staunch old heart has he.

How closely he twineth, how tight he clings

To his friend the huge Oak Tree!

And slyly he traileth along the ground,

And his leaves he gently waves,

As he joyously hugs and crawleth round

The rich mould of dead men’s graves.

Creeping where grim death hath been,

A rare old plant is the Ivy green.

Whole ages have fled and their works decayed,

And nations have scattered been;

But the stout old Ivy shall never fade,

From its hale and hearty green.

The brave old plant, in its lonely days,

Shall fatten upon the past:

For the stateliest building man can raise

Is the Ivy’s food at last.

Creeping on where time has been,

A rare old plant is the Ivy green.

.jpg)

Charles Dickens poetry

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Charles Dickens, Dickens, Charles

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature