Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

This little bag

This little bag I hope will prove

To be not vainly made–

For, if you should a needle want

It will afford you aid.

And as we are about to part

T’will serve another end,

For when you look upon the Bag

You’ll recollect your friend

Jane Austen

(1775 – 1817)

This little bag

Poem

•fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Austen, Jane, Austen, Jane, Jane Austen

O. Henry (William Sydney Porter):

The Gift of the Magi

A Christmas story

One dollar and eighty-seven cents. That was all. And sixty cents of it was in pennies. Pennies saved one and two at a time by bulldozing the grocer and the vegetable man and the butcher until one’s cheeks burned with the silent imputation of parsimony that such close dealing implied. Three times Della counted it. One dollar and eighty-seven cents. And the next day would be Christmas.

There was clearly nothing left to do but flop down on the shabby little couch and howl. So Della did it. Which instigates the moral reflection that life is made up of sobs, sniffles, and smiles, with sniffles predominating.

While the mistress of the home is gradually subsiding from the first stage to the second, take a look at the home. A furnished flat at $8 per week. It did not exactly beggar description, but it certainly had that word on the look-out for the mendicancy squad.

In the vestibule below was a letter-box into which no letter would go, and an electric button from which no mortal finger could coax a ring. Also appertaining thereunto was a card bearing the name “Mr. James Dillingham Young.”

The “Dillingham” had been flung to the breeze during a former period of prosperity when its possessor was being paid $30 per week. Now, when the income was shrunk to $20, the letters of “Dillingham” looked blurred, as though they were thinking seriously of contracting to a modest and unassuming D. But whenever Mr. James Dillingham Young came home and reached his flat above he was called “Jim” and greatly hugged by Mrs. James Dillingham Young, already introduced to you as Della. Which is all very good.

Della finished her cry and attended to her cheeks with the powder rag. She stood by the window and looked out dully at a grey cat walking a grey fence in a grey backyard. To-morrow would be Christmas Day, and she had only $1.87 with which to buy Jim a present. She had been saving every penny she could for months, with this result. Twenty dollars a week doesn’t go far. Expenses had been greater than she had calculated. They always are. Only $1.87 to buy a present for Jim. Her Jim. Many a happy hour she had spent planning for something nice for him. Something fine and rare and sterling–something just a little bit near to being worthy of the honour of being owned by Jim.

There was a pier-glass between the windows of the room. Perhaps you have seen a pier-glass in an $8 Bat. A very thin and very agile person may, by observing his reflection in a rapid sequence of longitudinal strips, obtain a fairly accurate conception of his looks. Della, being slender, had mastered the art.

Suddenly she whirled from the window and stood before the glass. Her eyes were shining brilliantly, but her face had lost its colour within twenty seconds. Rapidly she pulled down her hair and let it fall to its full length.

Now, there were two possessions of the James Dillingham Youngs in which they both took a mighty pride. One was Jim’s gold watch that had been his father’s and his grandfather’s. The other was Della’s hair. Had the Queen of Sheba lived in the flat across the airshaft, Della would have let her hair hang out of the window some day to dry just to depreciate Her Majesty’s jewels and gifts. Had King Solomon been the janitor, with all his treasures piled up in the basement, Jim would have pulled out his watch every time he passed, just to see him pluck at his beard from envy.

So now Della’s beautiful hair fell about her, rippling and shining like a cascade of brown waters. It reached below her knee and made itself almost a garment for her. And then she did it up again nervously and quickly. Once she faltered for a minute and stood still while a tear or two splashed on the worn red carpet.

On went her old brown jacket; on went her old brown hat. With a whirl of skirts and with the brilliant sparkle still in her eyes, she cluttered out of the door and down the stairs to the street.

Where she stopped the sign read: “Mme Sofronie. Hair Goods of All Kinds.” One Eight up Della ran, and collected herself, panting. Madame, large, too white, chilly, hardly looked the “Sofronie.”

“Will you buy my hair?” asked Della.

“I buy hair,” said Madame. “Take yer hat off and let’s have a sight at the looks of it.”

Down rippled the brown cascade.

“Twenty dollars,” said Madame, lifting the mass with a practised hand.

“Give it to me quick” said Della.

Oh, and the next two hours tripped by on rosy wings. Forget the hashed metaphor. She was ransacking the stores for Jim’s present.

She found it at last. It surely had been made for Jim and no one else. There was no other like it in any of the stores, and she had turned all of them inside out. It was a platinum fob chain simple and chaste in design, properly proclaiming its value by substance alone and not by meretricious ornamentation–as all good things should do. It was even worthy of The Watch. As soon as she saw it she knew that it must be Jim’s. It was like him. Quietness and value–the description applied to both. Twenty-one dollars they took from her for it, and she hurried home with the 78 cents. With that chain on his watch Jim might be properly anxious about the time in any company. Grand as the watch was, he sometimes looked at it on the sly on account of the old leather strap that he used in place of a chain.

When Della reached home her intoxication gave way a little to prudence and reason. She got out her curling irons and lighted the gas and went to work repairing the ravages made by generosity added to love. Which is always a tremendous task dear friends–a mammoth task.

Within forty minutes her head was covered with tiny, close-lying curls that made her look wonderfully like a truant schoolboy. She looked at her reflection in the mirror long, carefully, and critically.

“If Jim doesn’t kill me,” she said to herself, “before he takes a second look at me, he’ll say I look like a Coney Island chorus girl. But what could I do–oh! what could I do with a dollar and eighty-seven cents?”

At 7 o’clock the coffee was made and the frying-pan was on the back of the stove hot and ready to cook the chops.

Jim was never late. Della doubled the fob chain in her hand and sat on the corner of the table near the door that he always entered. Then she heard his step on the stair away down on the first flight, and she turned white for just a moment. She had a habit of saying little silent prayers about the simplest everyday things, and now she whispered: “Please, God, make him think I am still pretty.”

The door opened and Jim stepped in and closed it. He looked thin and very serious. Poor fellow, he was only twenty-two–and to be burdened with a family! He needed a new overcoat and he was with out gloves.

Jim stepped inside the door, as immovable as a setter at the scent of quail. His eyes were fixed upon Della, and there was an expression in them that she could not read, and it terrified her. It was not anger, nor surprise, nor disapproval, nor horror, nor any of the sentiments that she had been prepared for. He simply stared at her fixedly with that peculiar expression on his face.

Della wriggled off the table and went for him.

“Jim, darling,” she cried, “don’t look at me that way. I had my hair cut off and sold it because I couldn’t have lived through Christmas without giving you a present. It’ll grow out again–you won’t mind, will you? I just had to do it. My hair grows awfully fast. Say ‘Merry Christmas!’ Jim, and let’s be happy. You don’t know what a nice-what a beautiful, nice gift I’ve got for you.”

“You’ve cut off your hair?” asked Jim, laboriously, as if he had not arrived at that patent fact yet, even after the hardest mental labour.

“Cut it off and sold it,” said Della. “Don’t you like me just as well, anyhow? I’m me without my hair, ain’t I?”

Jim looked about the room curiously.

“You say your hair is gone?” he said, with an air almost of idiocy.

“You needn’t look for it,” said Della. “It’s sold, I tell you–sold and gone, too. It’s Christmas Eve, boy. Be good to me, for it went for you. Maybe the hairs of my head were numbered,” she went on with a sudden serious sweetness, “but nobody could ever count my love for you. Shall I put the chops on, Jim?”

Out of his trance Jim seemed quickly to wake. He enfolded his Della. For ten seconds let us regard with discreet scrutiny some inconsequential object in the other direction. Eight dollars a week or a million a year–what is the difference? A mathematician or a wit would give you the wrong answer. The magi brought valuable gifts, but that was not among them. This dark assertion will be illuminated later on.

Jim drew a package from his overcoat pocket and threw it upon the table.

“Don’t make any mistake, Dell,” he said, “about me. I don’t think there’s anything in the way of a haircut or a shave or a shampoo that could make me like my girl any less. But if you’ll unwrap that package you may see why you had me going a while at first.”

White fingers and nimble tore at the string and paper. And then an ecstatic scream of joy; and then, alas! a quick feminine change to hysterical tears and wails, necessitating the immediate employment of all the comforting powers of the lord of the flat.

For there lay The Combs–the set of combs, side and back, that Della had worshipped for long in a Broadway window. Beautiful combs, pure tortoise-shell, with jewelled rims–just the shade to wear in the beautiful vanished hair. They were expensive combs, she knew, and her heart had simply craved and yearned over them without the least hope of possession. And now, they were hers, but the tresses that should have adorned the coveted adornments were gone.

But she hugged them to her bosom, and at length she was able to look up with dim eyes and a smile and say: “My hair grows so fast, Jim!”

And then Della leaped up like a little singed cat and cried, “Oh, oh!”

Jim had not yet seen his beautiful present. She held it out to him eagerly upon her open palm. The dull precious metal seemed to flash with a reflection of her bright and ardent spirit.

“Isn’t it a dandy, Jim? I hunted all over town to find it. You’ll have to look at the time a hundred times a day now. Give me your watch. I want to see how it looks on it.”

Instead of obeying, Jim tumbled down on the couch and put his hands under the back of his head and smiled.

“Dell,” said he, “let’s put our Christmas presents away and keep ’em a while. They’re too nice to use just at present. I sold the watch to get the money to buy your combs. And now suppose you put the chops on.”

The magi, as you know, were wise men–wonderfully wise men-who brought gifts to the Babe in the manger. They invented the art of giving Christmas presents. Being wise, their gifts were no doubt wise ones, possibly bearing the privilege of exchange in case of duplication. And here I have lamely related to you the uneventful chronicle of two foolish children in a flat who most unwisely sacrificed for each other the greatest treasures of their house. But in a last word to the wise of these days let it be said that of all who give gifts these two were the wisest. Of all who give and receive gifts, such as they are wisest. Everywhere they are wisest. They are the magi.

O. Henry

(William Sydney Porter 1862 – 1910)

This story was originally published on Dec 10, 1905 in The New York Sunday World as “Gifts of the Magi.” It was subsequently published as The Gift of the Magi in O. Henry’s 1906 short story collection The Four Million.

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Henry, O., PRESS & PUBLISHING, Western Fiction

Symphony In Yellow

An omnibus across the bridge

Crawls like a yellow butterfly,

And, here and there a passer-by

Shows like a little restless midge.

Big barges full of yellow hay

Are moored against the shadowy wharf,

And, like a yellow silken scarf,

The thick fog hangs along the quay.

The yellow leaves begin to fade

And flutter from the temple elms,

And at my feet the pale green Thames

Lies like a rod of rippled jade.

Oscar Wilde

(1854 – 1900)

Symphony In Yellow

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive W-X, Archive W-X, Wilde, Oscar, Wilde, Oscar

Ballade De Marguerite

(Normande)

I am weary of lying within the chase

When the knights are meeting in market-place.

Nay, go not thou to the red-roofed town

Lest the hoofs of the war-horse tread thee down.

But I would not go where the Squires ride,

I would only walk by my Lady’s side.

Alack! and alack! thou art overbold,

A Forester’s son may not eat off gold.

Will she love me the less that my Father is seen

Each Martinmas day in a doublet green?

Perchance she is sewing at tapestrie,

Spindle and loom are not meet for thee.

Ah, if she is working the arras bright

I might ravel the threads by the fire-light.

Perchance she is hunting of the deer,

How could you follow o’er hill and mere?

Ah, if she is riding with the court,

I might run beside her and wind the morte.

Perchance she is kneeling in St. Denys,

(On her soul may our Lady have gramercy!)

Ah, if she is praying in lone chapelle,

I might swing the censer and ring the bell.

Come in, my son, for you look sae pale,

The father shall fill thee a stoup of ale.

But who are these knights in bright array?

Is it a pageant the rich folks play?

‘T is the King of England from over sea,

Who has come unto visit our fair countrie.

But why does the curfew toll sae low?

And why do the mourners walk a-row?

O ‘t is Hugh of Amiens my sister’s son

Who is lying stark, for his day is done.

Nay, nay, for I see white lilies clear,

It is no strong man who lies on the bier.

O ‘t is old Dame Jeannette that kept the hall,

I knew she would die at the autumn fall.

Dame Jeannette had not that gold-brown hair,

Old Jeannette was not a maiden fair.

O ‘t is none of our kith and none of our kin,

(Her soul may our Lady assoil from sin!)

But I hear the boy’s voice chaunting sweet,

‘Elle est morte, la Marguerite.’

Come in, my son, and lie on the bed,

And let the dead folk bury their dead.

O mother, you know I loved her true:

O mother, hath one grave room for two?

Oscar Wilde

(1854 – 1900)

Ballade De Marguerite

(Normande)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive W-X, Archive W-X, Wilde, Oscar, Wilde, Oscar

The Garden of Eros

IT is full summer now, the heart of June,

Not yet the sun-burnt reapers are a-stir

Upon the upland meadow where too soon

Rich autumn time, the season’s usurer,

Will lend his hoarded gold to all the trees,

And see his treasure scattered by the wild and spendthrift breeze.

Too soon indeed! yet here the daffodil,

That love-child of the Spring, has lingered on

To vex the rose with jealousy, and still

The harebell spreads her azure pavilion,

And like a strayed and wandering reveller

Abandoned of its brothers, whom long since June’s messenger

The missel-thrush has frighted from the glade,

One pale narcissus loiters fearfully

Close to a shadowy nook, where half afraid

Of their own loveliness some violets lie

That will not look the gold sun in the face

For fear of too much splendour,—ah! methinks it is a place

Which should be trodden by Persephone

When wearied of the flowerless fields of Dis!

Or danced on by the lads of Arcady!

The hidden secret of eternal bliss

Known to the Grecian here a man might find,

Ah! you and I may find it now if Love and Sleep be kind.

There are the flowers which mourning Herakles

Strewed on the tomb of Hylas, columbine,

Its white doves all a-flutter where the breeze

Kissed them too harshly, the small celandine,

That yellow-kirtled chorister of eve,

And lilac lady’s-smock,—but let them bloom alone, and leave

Yon spired holly-hock red-crocketed

To sway its silent chimes, else must the bee,

Its little bellringer, go seek instead

Some other pleasaunce; the anemone

That weeps at daybreak, like a silly girl

Before her love, and hardly lets the butterflies unfurl

Their painted wings beside it,—bid it pine

In pale virginity; the winter snow

Will suit it better than those lips of thine

Whose fires would but scorch it, rather go

And pluck that amorous flower which blooms alone,

Fed by the pander wind with dust of kisses not its own.

The trumpet-mouths of red convolvulus

So dear to maidens, creamy meadow-sweet

Whiter than Juno’s throat and odorous

As all Arabia, hyacinths the feet

Of Huntress Dian would be loth to mar

For any dappled fawn,—pluck these, and those fond flowers which are

Fairer than what Queen Venus trod upon

Beneath the pines of Ida, eucharis,

That morning star which does not dread the sun,

And budding marjoram which but to kiss

Would sweeten Cytheræa’s lips and make

Adonis jealous,—these for thy head,—and for thy girdle take

Yon curving spray of purple clematis

Whose gorgeous dye outflames the Tyrian King,

And fox-gloves with their nodding chalices,

But that one narciss which the startled Spring

Let from her kirtle fall when first she heard

In her own woods the wild tempestuous song of summer’s bird,

Ah! leave it for a subtle memory

Of those sweet tremulous days of rain and sun,

When April laughed between her tears to see

The early primrose with shy footsteps run

From the gnarled oak-tree roots till all the wold,

Spite of its brown and trampled leaves, grew bright with shimmering gold.

Nay, pluck it too, it is not half so sweet

As thou thyself, my soul’s idolatry!

And when thou art a-wearied at thy feet

Shall oxlips weave their brightest tapestry,

For thee the woodbine shall forget its pride

And vail its tangled whorls, and thou shalt walk on daisies pied.

And I will cut a reed by yonder spring

And make the wood-gods jealous, and old Pan

Wonder what young intruder dares to sing

In these still haunts, where never foot of man

Should tread at evening, lest he chance to spy

The marble limbs of Artemis and all her company.

And I will tell thee why the jacinth wears

Such dread embroidery of dolorous moan,

And why the hapless nightingale forbears

To sing her song at noon, but weeps alone

When the fleet swallow sleeps, and rich men feast,

And why the laurel trembles when she sees the lightening east.

And I will sing how sad Proserpina

Unto a grave and gloomy Lord was wed,

And lure the silver-breasted Helena

Back from the lotus meadows of the dead,

So shalt thou see that awful loveliness

For which two mighty Hosts met fearfuly in war’s abyss!

And then I ’ll pipe to thee that Grecian tale

How Cynthia loves the lad Endymion,

And hidden in a grey and misty veil

Hies to the cliffs of Latmos once the Sun

Leaps from his ocean bed in fruitless chase

Of those pale flying feet which fade away in his embrace.

And if my flute can breathe sweet melody,

We may behold Her face who long ago

Dwelt among men by the Ægean sea,

And whose sad house with pillaged portico

And friezeless wall and columns toppled down

Looms o’er the ruins of that fair and violet-cinctured town.

Spirit of Beauty! tarry still a-while,

They are not dead, thine ancient votaries,

Some few there are to whom thy radiant smile

Is better than a thousand victories,

Though all the nobly slain of Waterloo

Rise up in wrath against them! tarry still, there are a few.

Who for thy sake would give their manlihood

And consecrate their being, I at least

Have done so, made thy lips my daily food,

And in thy temples found a goodlier feast

Than this starved age can give me, spite of all

Its new-found creeds so sceptical and so dogmatical.

Here not Cephissos, not Ilissos flows,

The woods of white Colonos are not here,

On our bleak hills the olive never blows,

No simple priest conducts his lowing steer

Up the steep marble way, nor through the town

Do laughing maidens bear to thee the crocus-flowered gown.

Yet tarry! for the boy who loved thee best,

Whose very name should be a memory

To make thee linger, sleeps in silent rest

Beneath the Roman walls, and melody

Still mourns her sweetest lyre, none can play

The lute of Adonais, with his lips Song passed away.

Nay, when Keats died the Muses still had left

One silver voice to sing his threnody,

But ah! too soon of it we were bereft

When on that riven night and stormy sea

Panthea claimed her singer as her own,

And slew the mouth that praised her; since which time we walk alone,

Save for that fiery heart, that morning star

Of re-arisen England, whose clear eye

Saw from our tottering throne and waste of war

The grand Greek limbs of young Democracy

Rise mightily like Hesperus and bring

The great Republic! him at least thy love hath taught to sing,

And he hath been with thee at Thessaly,

And seen white Atalanta fleet of foot

In passionless and fierce virginity

Hunting the tuskéd boar, his honied lute

Hath pierced the cavern of the hollow hill,

And Venus laughs to know one knee will bow before her still.

And he hath kissed the lips of Proserpine,

And sung the Galilæan’s requiem,

That wounded forehead dashed with blood and wine

He hath discrowned, the Ancient Gods in him

Have found their last, most ardent worshipper,

And the new Sign grows grey and dim before its conqueror.

Spirit of Beauty! tarry with us still,

It is not quenched the torch of poesy,

The star that shook above the Eastern hill

Holds unassailed its argent armoury

From all the gathering gloom and fretful fight—

O tarry with us still! for through the long and common night,

Morris, our sweet and simple Chaucer’s child,

Dear heritor of Spenser’s tuneful reed,

With soft and sylvan pipe has oft beguiled

The weary soul of man in troublous need,

And from the far and flowerless fields of ice

Has brought fair flowers meet to make an earthly paradise.

We know them all, Gudrun the strong men’s bride,

Aslaug and Olafson we know them all,

How giant Grettir fought and Sigurd died,

And what enchantment held the king in thrall

When lonely Brynhild wrestled with the powers

That war against all passion, ah! how oft through summer hours,

Long listless summer hours when the noon

Being enamoured of a damask rose

Forgets to journey westward, till the moon

The pale usurper of its tribute grows

From a thin sickle to a silver shield

And chides its loitering car—how oft, in some cool grassy field

Far from the cricket-ground and noisy eight,

At Bagley, where the rustling bluebells come

Almost before the blackbird finds a mate

And overstay the swallow, and the hum

Of many murmuring bees flits through the leaves,

Have I lain poring on the dreamy tales his fancy weaves,

And through their unreal woes and mimic pain

Wept for myself, and so was purified,

And in their simple mirth grew glad again;

For as I sailed upon that pictured tide

The strength and splendour of the storm was mine

Without the storm’s red ruin, for the singer is divine,

The little laugh of water falling down

Is not so musical, the clammy gold

Close hoarded in the tiny waxen town

Has less of sweetness in it, and the old

Half-withered reeds that waved in Arcady

Touched by his lips break forth again to fresher harmony.

Spirit of Beauty tarry yet a-while!

Although the cheating merchants of the mart

With iron roads profane our lovely isle,

And break on whirling wheels the limbs of Art,

Ay! though the crowded factories beget

The blind-worm Ignorance that slays the soul, O tarry yet!

For One at least there is,—He bears his name

From Dante and the seraph Gabriel,—

Whose double laurels burn with deathless flame

To light thine altar; He too loves thee well,

Who saw old Merlin lured in Vivien’s snare,

And the white feet of angels coming down the golden stair,

Loves thee so well, that all the World for him

A gorgeous-coloured vestiture must wear,

And Sorrow take a purple diadem,

Or else be no more Sorrow, and Despair

Gild its own thorns, and Pain, like Adon, be

Even in anguish beautiful;—such is the empery

Which Painters hold, and such the heritage

This gentle solemn Spirit doth possess,

Being a better mirror of his age

In all his pity, love, and weariness,

Than those who can but copy common things,

And leave the Soul unpainted with its mighty questionings.

But they are few, and all romance has flown,

And men can prophesy about the sun,

And lecture on his arrows—how, alone,

Through a waste void the soulless atoms run,

How from each tree its weeping nymph has fled,

And that no more ’mid English reeds a Naïad shows her head.

Methinks these new Actæons boast too soon

That they have spied on beauty; what if we

Have analyzed the rainbow, robbed the moon

Of her most ancient, chastest mystery,

Shall I, the last Endymion, lose all hope

Because rude eyes peer at my mistress through a telescope!

What profit if this scientific age

Burst through our gates with all its retinue

Of modern miracles! Can it assuage

One lover’s breaking heart? what can it do

To make one life more beautiful, one day

More god-like in its period? but now the Age of Clay

Returns in horrid cycle, and the earth

Hath borne again a noisy progeny

Of ignorant Titans, whose ungodly birth

Hurls them against the august hierarchy

Which sat upon Olympus, to the Dust

They have appealed, and to that barren arbiter they must

Repair for judgment, let them, if they can,

From Natural Warfare and insensate Chance,

Create the new Ideal rule for man!

Methinks that was not my inheritance;

For I was nurtured otherwise, my soul

Passes from higher heights of life to a more supreme goal.

Lo! while we spake the earth did turn away

Her visage from the God, and Hecate’s boat

Rose silver-laden, till the jealous day

Blew all its torches out: I did not note

The waning hours, to young Endymions

Time’s palsied fingers count in vain his rosary of suns!—

Mark how the yellow iris wearily

Leans back its throat, as though it would be kissed

By its false chamberer, the dragon-fly,

Who, like a blue vein on a girl’s white wrist,

Sleeps on that snowy primrose of the night,

Which ’gins to flush with crimson shame, and die beneath the light.

Come let us go, against the pallid shield

Of the wan sky the almond blossoms gleam,

The corn-crake nested in the unmown field

Answers its mate, across the misty stream

On fitful wing the startled curlews fly,

And in his sedgy bed the lark, for joy that Day is nigh,

Scatters the pearléd dew from off the grass,

In tremulous ecstasy to greet the sun,

Who soon in gilded panoply will pass

Forth from yon orange-curtained pavilion

Hung in the burning east, see, the red rim

O’ertops the expectant hills! it is the God! for love of him

Already the shrill lark is out of sight,

Flooding with waves of song this silent dell,—

Ah! there is something more in that bird’s flight

Than could be tested in a crucible!—

But the air freshens, let us go,—why soon

The woodmen will be here; how we have lived this night of June!

Oscar Wilde

(1854 – 1900)

The Garden of Eros

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive W-X, Archive W-X, Wilde, Oscar, Wilde, Oscar

The Sleeper

At midnight, in the month of June,

I stand beneath the mystic moon.

An opiate vapor, dewy, dim,

Exhales from out her golden rim,

And softly dripping, drop by drop,

Upon the quiet mountain top,

Steals drowsily and musically

Into the universal valley.

The rosemary nods upon the grave;

The lily lolls upon the wave;

Wrapping the fog about its breast,

The ruin moulders into rest;

Looking like Lethe, see! the lake

A conscious slumber seems to take,

And would not, for the world, awake.

All Beauty sleeps!—and lo! where lies

Irene, with her Destinies!

Oh, lady bright! can it be right—

This window open to the night?

The wanton airs, from the tree-top,

Laughingly through the lattice drop—

The bodiless airs, a wizard rout,

Flit through thy chamber in and out,

And wave the curtain canopy

So fitfully—so fearfully—

Above the closed and fringéd lid

’Neath which thy slumb’ring soul lies hid,

That, o’er the floor and down the wall,

Like ghosts the shadows rise and fall!

Oh, lady dear, hast thou no fear?

Why and what art thou dreaming here?

Sure thou art come o’er far-off seas,

A wonder to these garden trees!

Strange is thy pallor! strange thy dress!

Strange, above all, thy length of tress,

And this all solemn silentness!

The lady sleeps! Oh, may her sleep,

Which is enduring, so be deep!

Heaven have her in its sacred keep!

This chamber changed for one more holy,

This bed for one more melancholy,

I pray to God that she may lie

Forever with unopened eye,

While the pale sheeted ghosts go by!

My love, she sleeps! Oh, may her sleep,

As it is lasting, so be deep!

Soft may the worms about her creep!

Far in the forest, dim and old,

For her may some tall vault unfold—

Some vault that oft hath flung its black

And wingéd pannels fluttering back,

Triumphant, o’er the crested palls

Of her grand family funerals—

Some sepulchre, remote, alone,

Against whose portals she hath thrown,

In childhood, many an idle stone—

Some tomb from out whose sounding door

She ne’er shall force an echo more,

Thrilling to think, poor child of sin!

It was the dead who groaned within.

Edgar Allan Poe

(1809 – 1849)

The Sleeper

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Archive Tombeau de la jeunesse, Archive O-P, Archive O-P, Edgar Allan Poe, Poe, Edgar Allan, Poe, Edgar Allan, Tales of Mystery & Imagination

Les oies sauvages

Tout est muet, l’oiseau ne jette plus ses cris.

La morne plaine est blanche au loin sous le ciel gris.

Seuls, les grands corbeaux noirs, qui vont cherchant leurs proies,

Fouillent du bec la neige et tachent sa pâleur.

Voilà qu’à l’horizon s’élève une clameur ;

Elle approche, elle vient, c’est la tribu des oies.

Ainsi qu’un trait lancé, toutes, le cou tendu,

Allant toujours plus vite, en leur vol éperdu,

Passent, fouettant le vent de leur aile sifflante.

Le guide qui conduit ces pèlerins des airs

Delà les océans, les bois et les déserts,

Comme pour exciter leur allure trop lente,

De moment en moment jette son cri perçant.

Comme un double ruban la caravane ondoie,

Bruit étrangement, et par le ciel déploie

Son grand triangle ailé qui va s’élargissant.

Mais leurs frères captifs répandus dans la plaine,

Engourdis par le froid, cheminent gravement.

Un enfant en haillons en sifflant les promène,

Comme de lourds vaisseaux balancés lentement.

Ils entendent le cri de la tribu qui passe,

Ils érigent leur tête ; et regardant s’enfuir

Les libres voyageurs au travers de l’espace,

Les captifs tout à coup se lèvent pour partir.

Ils agitent en vain leurs ailes impuissantes,

Et, dressés sur leurs pieds, sentent confusément,

A cet appel errant se lever grandissantes

La liberté première au fond du coeur dormant,

La fièvre de l’espace et des tièdes rivages.

Dans les champs pleins de neige ils courent effarés,

Et jetant par le ciel des cris désespérés

Ils répondent longtemps à leurs frères sauvages.

Guy de Maupassant

(1850 – 1893)

Les oies sauvages

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: 4SEASONS#Winter, Archive M-N, Archive M-N, Guy de Maupassant, Maupassant, Guy de, Maupassant, Guy de

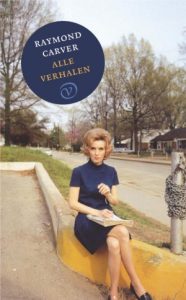

Raymond Carvers wereldfaam berust op tweeënzeventig korte verhalen waarin zelden iets bijzonders gebeurt.

Carver beschrijft de gewone wederwaardigheden van gewone mensen in gewoon proza. Zijn grote talent is het naar boven brengen van het bijzondere, het beangstigende en het dramatische in al die gewoonheid.

In zijn eigen woorden: ‘Het is mogelijk om in een gedicht of verhaal over alledaagse dingen en voorwerpen te schrijven in alledaagse maar dan wel precieze taal en die dingen – een stoel, het gordijn voor een raam, een vork, een steen, de oorbel van een vrouw – een immense, zelfs aangrijpende lading mee te geven.’

De verhalen van Carver vormen het schoolvoorbeeld van het korte verhaal als een slice of life: er is weinig plot, weinig expliciete voorgeschiedenis; hoe het afloopt krijg je ook nooit te lezen, maar de kennismaking met een volstrekt authentiek, onbekend leven, dat in zijn beperktheid toch een volledig beeld geeft, brandt de lezer in de ziel.

Carver-vertaler Sjaak Commandeur selecteerde speciaal voor deze uitgave 200 pagina’s nooit eerder vertaald werk. Een kleine weldaad is de grootste verzameling van Carvers werk die ooit in Nederland verscheen, met onder veel meer de klassiekers Wees alsjeblieft stil, alsjeblieft, Waar we over praten als we over liefde praten en Kathedraal.

Raymond Carver (1938–1988) brak in 1976 door met de publicatie van zijn verhaal ‘Will You Please Be Quiet, Please?’ en de gelijknamige bundel. Later volgden de verhalenbundels What We Talk About When We Talk About Love (1981) en Cathedral (1983). Carver groeide op in een gezin uit de lagere middenklasse. De uitdagingen en moeilijkheden die hij in die sociale klasse observeerde, vormen een centraal thema in zijn gehele oeuvre, evenals zijn eigen worstelingen in zijn huwelijk en met een alcoholverslaving. Carver is een van de meest karakteristieke stemmen uit de twintigste-eeuwse Amerikaanse literatuur.

Auteur: Raymond Carver

Een kleine weldaad.

Alle Verhalen

Vertaler: Sjaak Commandeur

Taal: Nederlands

Releasedatum: 01 september 2023

Bindwijze: Gebonden

ISBN 9789028232075

812 pagina’s

Prijs: € 45,00

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive C-D, Archive C-D, Carver, Raymond

Vintage Readers are a perfect introduction to some of the great modern writers: The celebrated bestselling author of The House on Mango Street “knows both that the heart can be broken and that it can rise and soar like a bird.

Whatever story she chooses to tell, we should be listening for a long time to come” (The Washington Post Book World).

Whatever story she chooses to tell, we should be listening for a long time to come” (The Washington Post Book World).

A winner of the PEN/Nabokov Award for Achievement in International Literature and the prestigious MacArthur Fellowship, Sandra Cisneros evokes working-class Latino experience with an irresistible mix of realism and lyrical exuberance.

Vintage Cisneros features an excerpt from her bestselling novel The House on Mango Street, which has become a favorite in school classrooms across the country.

Also included are a chapter from her novel, Caramelo; a generous selection of poems from My Wicked Wicked Ways and Loose Woman; and seven stories from her award-winning collection Woman Hollering Creek.

SANDRA CISNEROS is a poet, short story writer, novelist and essayist whose work explores the lives of the working-class. Her numerous awards include NEA fellowships in both poetry and fiction, the Texas Medal of the Arts, a MacArthur Fellowship, several honorary doctorates and national and international book awards, including Chicago’s Fifth Star Award, the PEN Center USA Literary Award, and the National Medal of the Arts awarded to her by President Obama in 2016. Most recently, she received the Ford Foundation’s Art of Change Fellowship, was recognized among The Frederick Douglass 200, and was awarded the PEN/Nabokov Award for Achievement in International Literature.

Her classic, coming-of-age novel, The House on Mango Street, has sold over six million copies, has been translated into over twenty languages, and is required reading in elementary, high school, and universities across the nation.

In addition to her writing, Cisneros has fostered the careers of many aspiring and emerging writers through two non-profits she founded: the Macondo Foundation and the Alfredo Cisneros del Moral Foundation. She is also the organizer of Los MacArturos, Latino MacArthur fellows who are community activists. Her literary papers are preserved in Texas at the Wittliff Collections at Texas State University.

Sandra Cisneros is a dual citizen of the United States and Mexico and earns her living by her pen. She currently lives in San Miguel de Allende.

Vintage Readers

By Sandra Cisneros

Publisher: Vintage

Series: Vintage Readers

Language: English

2004

Pages: 208

ISBN: 9781400034055

ISBN-10: 1400034051

paperback

$12.95

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #Short Stories Archive, - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive C-D

Het Incident

Geachte Heer en Mevrouw Waasdorp,

Via deze weg wil ik graag nog even terugkomen op het incident van 13 november jongstleden.

Het spijt ons –ik moet hier specifiek Mevr. Van Eeken, onze gewaardeerde docent Aardrijkskunde, ook niet onbenoemd laten- ten zeerste dat wat begon als een klein voorval, zo uit de hand kon lopen. In het verlengde hiervan doet het ons zeer veel verdriet dat de schorsing van uw zoon Wesley dan ook niet vermeden kon worden.

Als school staan we ontegenzeggelijk voor goed onderwijs, maar vooral ook voor inclusie, we vormen immers het voorportaal van de maatschappij. Het feit dat Wesley in zijn periode van schorsing niet deel kan nemen aan het onderwijs –en in feite dus aan de maatschappij – raakt óók ons diep in ons onderwijshart.

In het gesprek wat we 15 november hebben gevoerd op school was er achteraf gezien iets teveel emotie om objectief te bespreken wat er nou daadwerkelijk was gebeurd. Om die reden vinden we het belangrijk om middels deze brief enkele –in onze bescheiden optiek- onderbelichte aspecten nog eens aan te stippen.

Laat ik voorop stellen dat Wesley een immer aanwezige leerling is binnen de muren van onze scholengemeenschap. Een energieke jongen die door docenten vooral omschreven wordt als vindingrijk en sociaal georiënteerd. Iemand die zelden tot nooit ziek is en nooit te beroerd is om zijn mening in de klas te geven. Iets wat wij als voorstanders van dialoog en debat alleen maar kunnen toejuichen.

Natuurlijk, hij is wel eens betrokken geweest bij vechtpartijen, pesterijen, enkele bewezen gevallen van fraude bij schoolexamens en drugshandel op school. Maar laten we geen oude koeien uit de sloot halen. Voor het laatste heeft hij overigens zijn straf al gehad toen hij drie maanden in detentie zat in Sassenheim. Ook toen was Wesley een lange periode verstoken van (goed) onderwijs. In dat opzicht kunnen we stellen dat de huidige situatie ons des te meer zorgen baart.

Ik kan me niet voorstellen dat Wesley thuis wel inzet toont en een wezenlijke bijdrage aan bijvoorbeeld het huishouden levert. Zelfs een bordje naar de keuken brengen is waarschijnlijk al teveel gevraagd. Op school herkennen we dat wel. Als we hem vriendelijk vragen om een geleend boek terug te leggen in de kast wenst hij ons steevast allerhande ziektes toe, waarbij we vooral de rattentyfus en de grafebola niet onbenoemd willen laten. Wenst hij u deze creatieve ziektes ook toe als u hem vraagt een kommetje kerriesoep weer op het aanrecht te zetten? Van meehelpen in het huishouden kan geen sprake zijn. U zou het eigenlijk beter tegenwerken van het huishouden kunnen noemen als u eerlijk bent. Dat brengt me eigenlijk meteen terug naar de kern: Eerlijkheid. Daar schort het toch wel een beetje aan bij Wesley. Mag ik dat zeggen? De wijze waarop hij de ene na de andere leugen schijnbaar zonder enige moeite tussen zijn ongepoetste tanden door laat glippen, is even onbeschoft als zorgwekkend te noemen. Maar dit terzijde.

Laten we nog even terug gaan naar die bewuste middag vorige week. Ik zal de situatie zo objectief mogelijk trachten te schetsen.

Wesley kwam (wederom) tien minuten te laat in de les bij mevr. Van Eeken. Volgens zijn zeggen was hij vanwege een toiletbezoek te laat. Dat leek Mevr. Van Eeken wat overdreven en zij heeft mij telefonisch op de hoogte gesteld. We hebben polshoogte genomen bij de toiletten op de eerste verdieping en troffen daar op de muur een onrealistisch groot getekende jongeheer aan. Met veel aandacht –als ik een hang naar drama had, zou ik “liefde” zeggen- met zwarte watervaste stift op de muur gekalkt. Precies zo’n marker vonden we in de tas van Wesley. Helemaal bewijzen kunnen we het uiteraard niet maar het riekt er toch wel naar dat Wesley deze kunstuiting op zijn palmares kan schrijven. Op ingeleverd werk vonden we immers tekeningen die ernstige overeenkomsten vertoonden met het kunstwerk in de toiletten. Hier was verder forensisch sporenonderzoek in onze optiek dan ook overbodig. Overigens konden we in het toilet niet de kenmerkende geur van Wesley’s uitwerpselen waarnemen, wat de achterdocht jegens Wesley’s vermeende onschuld deed groeien.

Enfin, Wesley was na deze betichting onzer zijde zo verbolgen dat er geen spreekwoordelijk land meer mee te bezeilen was. De woorden die hij hierbij gebruikte kan ik lastig herhalen, maar kwamen er op neer dat Mevr. Van Eeken de betreffende marker in haar vleesportemonnee kon opbergen. Volgens Mevrouw Van Eeken was dit verzoek gekoppeld aan een irreëel verwachtingspatroon en leek bovendien fysiek onhaalbaar gezien de medische status van Mevrouw Van Eeken. Wesley maakte hier op onvolwassen wijze misbruik van de uitgelekte kennis betreffende mevrouw Van Eeken’s recente operatie in de onderste regionen. Hoewel uitgelekt hier misschien een onhandig gekozen term is.

Toegegeven, iedereen verdient een tweede kans, maar over een eventuele zesentwintigste kans zijn de kaarten wat mij betreft nog niet geschud. Ik heb hier echter weinig over te zeggen zolang het Bestuur van mening is dat we leerlingen niet kunnen verwijderen voordat we op zijn minst van doodslag kunnen spreken. Ik kan wel verklappen dat het voltallige docentencorps er in hoge mate tegenop ziet om het kadaver dat Wesley genoemd wordt, weer met zijn beschimmelde blik door het schoolgebouw te zien struinen. Wat hij hier komt halen weet dan ook geen mens. Het zou mooi zijn als er een beroep zou zijn waar het tekenen van strakke plassers tot de kerntaken behoort, maar zolang dat er niet is, zien we het somber in wat betreft de toekomstkansen van Wesley.

Ik zou deze brief kunnen besluiten met de verwachting uit te spreken dat het vanaf nu anders zal gaan, maar we weten allemaal wel beter. Waarschijnlijk spreken we elkaar binnen luttele dagen om het volgende incident te bespreken. We kunnen enkel hopen dat jullie dan als gezin iets meer gewassen ten tonele zult verschijnen. De exotische mengeling van even grote delen knoflook, opgedroogd zweet en iets wat ik enkel kan omschrijven als menselijke ontlasting, is vrees ik in het leer van onze fauteuils getrokken om erin te blijven wonen.

Hoogachtend,

Drs. J. Schuddetrut

Rector O.S.G. Balthasar Gerards

Tekst: Thomas van der Vliet

Thomas van der Vliet is van oorsprong een muzikant. Hij heeft met zijn band The Bullfight in 2022 nationaal hoge ogen gegooid (**** – Volkskrant) met het spoken word album Some Divine Gift, waarbij hij gedichten en korte verhalen van onder andere Barry Hay, Spinvis, Alex Roeka en David Boulter (Tindersticks) op muziek heeft gezet.

Thomas van der Vliet is van oorsprong een muzikant. Hij heeft met zijn band The Bullfight in 2022 nationaal hoge ogen gegooid (**** – Volkskrant) met het spoken word album Some Divine Gift, waarbij hij gedichten en korte verhalen van onder andere Barry Hay, Spinvis, Alex Roeka en David Boulter (Tindersticks) op muziek heeft gezet.

Als schrijver was Van der Vliet eerder betrokken bij educatieve uitgaven (Uitgeverij SWP) en als scenarist voor een korte film voor het Rotterdams Film Festival.

In 2024 verschijnt zijn romandebuut Het Interview via Uitgeverij Studio Kers. Naast de gedrukte versie zal een audioboek beschikbaar komen, ingesproken door muzikant Alex Roeka en van soundtrack voorzien door Van der Vliet’s band The Bullfight.

(linosnede door Hélène Bautista)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: # Music Archive, #Short Stories Archive, Archive U-V

Le Yalou

Civilization, according to the interpretation of the

Occident, serves only to satisfy men of large desires.

Vicomte Torio.

En septembre mil huit cent quatre-vingt-quinze, et en Chine, un jour bleu et blanc, le lettré me conduisit à un phare de bois noir, sur le sable du rivage.

Nous quittâmes les derniers bosquets. Nous marchâmes, dormants, assoupis par la paresse du sol en poudre fondante, par qui étaient bus nos efforts, et qui descendait sous nos pas. Nous quittâmes le sable, enfin. Je regardai, en résumé, la vague trace de notre chemin se tordre et fuser sur la plage. Je vis dans les jambes du phare cligner la lumière de l’eau.

A chaque marche, nous devenions plus légers, et nous respirions et nous voyions davantage. Vers la mi-hauteur, nous devînmes plus lourds. Un vent plein et bien tendu se mit heureusement à exister : il a tâtonné les barres de bois tièdes à travers la soie se gonflant de la robe du Chinois. La mer monte avec nous.

A chaque marche, nous devenions plus légers, et nous respirions et nous voyions davantage. Vers la mi-hauteur, nous devînmes plus lourds. Un vent plein et bien tendu se mit heureusement à exister : il a tâtonné les barres de bois tièdes à travers la soie se gonflant de la robe du Chinois. La mer monte avec nous.

Toute la vue nous vint comme un frais aliment. Là-haut, il faisait si bon que nous sentîmes bientôt un petit besoin à satisfaire. Au bout d’un temps indifférent, la douce égalité du mouvement, du calme nous saisit.

La mer, qui me remuait tendrement, me rendait facile. Elle emplissait tout le reste de ma vie, avec une grande patience qui me faisait plaisir elle m’usait, je me sentais devenir régulier.

Les ondes, tournant sans peine, me donnaient la sensation de fumer, après avoir beaucoup fumé, et de devoir fumer infiniment encore. C’est alors que le souvenir édulcoré de maintes choses importantes passa aisément dans mon esprit : je sentis une volupté principale à y penser avec indifférence ; je souris à l’idée que ce bien-être pouvait éliminer certains erreurs, et m’éclairer.

Donc . . . Et je baissai mes paupières, ne voyant plus de la brillante mer que ce qu’on voit d’un petit verre de liqueur dorée, portée aux yeux. Et je fermai les yeux. Les sons de la promenade de l’eau me comblaient.

J’ignore comment vint à mon compagnon un désir de parler et de vaincre l’air délicieux, l’oubli. Je me disais : Que va-t-il dire ? aux premiers mots obscurs.

– Nippon, dit-il, nous faire la guerre. Ses grands bateaux blancs fument dans nos mauvais rêves. Ils vont troubler nos golfes. Ils feront des feux dans la nuit paisible.

– Ils sont très forts, soupirai-je, ils nous imitent.

– Vous êtes des enfants, dit le Chinois, je connais ton Europe.

– En souriant tu l’as visitée.

– J’ai peut-être souri. Sûrement, à l’ombre des autres regards, j’ai ri. La figure que je me vois seul, riait abondamment, tandis que les joyeux moqueurs qui me suivaient et me montraient du doigt n’auraient pu supporter la réflexion de leur propre vie. Mais je voyais et je touchais le désordre insensé de l’Europe. Je ne puis même pas comprendre la durée, pourtant bien courte, d’une telle confusion. Vous n’avez ni la patience qui tisse les longues vies, ni le sentiment de l’irrégularité, ni le sens de la place la plus exquise d’une chose, ni la connaissance du gouvernement. Vous vous épuisez à recommencer sans cesse l’œuvre du premier jour. Vos pères ainsi sont deux fois morts, et vous, vous avez peur de la mort.

« Chez vous, le pouvoir ne peut rien. Votre politique est faite de repentirs, elle conduit à des révolutions générales, et ensuite aux regrets des révolutions, qui sont aussi des révolutions. Vos chefs ne commandent pas, vos hommes libres travaillent, vos esclaves vous font peur, vos grands hommes baisent les pieds des foules, adorent les petits, ont besoin de tout le monde. Vous êtes livrés à la richesse et à l’opinion féroces. Mais touche de ton esprit la plus exquise de vos erreurs.

« L’intelligence, pour vous, n’est pas une chose comme les autres. Elle n’est ni prévue, ni amortie, ni protégée, ni réprimée, ni dirigée; vous l’adorez comme une bête prépondérante. Chaque jour elle dévore ce qui existe. Elle aimerait à terminer chaque soir un nouvel état de société. Un particulier qu’elle enivre, compare sa pensée aux décisions des lois, aux faits eux-mêmes, nés de la foule et de la durée : il confond le rapide changement de son cœur avec la variation imperceptible des formes réelles et des Êtres durables. (Durant une fleur, mille désirs ont existé ; mille fois, on a pu jouir d’avoir trouvé le défaut de la corolle… mille corolles qu’on a crues plus belles ont été coloriées dans l’esprit, mais ont disparu…) C’est par cette loi que l’intelligence méprise les lois . . . et vous encouragez sa violence ! Vous en êtes fous jusqu’au moment de la peur. Car vos idées sont terribles et vos cœurs faibles. Vos pitiés, vos cruautés sont absurdes, sans calme, comme irrésistibles. Enfin, vous craignez le sang, de plus en plus. Vous craignez le sang et le temps.

« Cher barbare, ami imparfait, je suis un lettré du pays de Thsin, près de la mer Bleue. Je connais l’écriture, le commandement à la guerre, et la direction de l’agriculture. Je veux ignorer votre maladie d’inventions et votre débauche de mélange d’idées. Je sais quelque chose de plus puissant. Oui, nous, hommes d’ici, nous mangeons par millions continuels, les plus favorables vallées de la terre ; et la profondeur de ce golfe immense d’individus garde la forme d’une famille ininterrompue depuis les premiers temps. Chaque homme d’ici se sent fils et père, entre le mille et le dix mille, et se voit saisi dans le peuple autour de lui, et dans le peuple mort au-dessous de lui, et dans le peuple à venir, comme la brique dans le mur de briques. Il tient. Chaque homme d’ici sait qu’il n’est rien sans cette terre pleine, et hors de la merveilleuse construction d’ancêtres. Au point où les aïeux pâlissent, commencent les foules des Dieux. Celui qui médite peut mesurer dans sa pensée la belle forme et la solidité de notre tour éternelle.

« Songe à la trame de notre race ; et, dis-moi, vous qui coupez vos racines et qui desséchez vos fleurs, comment existez-vous encore ? Sera-ce longtemps?

« Notre empire est tissu de vivants et de morts et de la nature. Il existe parce qu’il arrange toutes les choses. Ici, tout est historique : une certaine fleur, la douceur d’une heure qui tourne, la chair délicate des lacs entrouverts par le rayon, une éclipse émouvante… Sur ces choses, se rencontrent les esprits de nos pères avec les nôtres. Elles se reproduisent et, tandis que nous répétons les sons qu’ils leur ont donnés pour noms, le souvenir nous joint à eux et nous éternise.

« Tels, nous semblons dormir et nous sommes méprisés. Pourtant, tout se dissout dans notre magnifique quantité. Les conquérants se perdent dans notre eau jaune. Les armées étrangères se noient dans le flux de notre génération, ou s’écrasent contre nos ancêtres. Les chutes majestueuses de nos fleuves d’existences et la descente grossissante de nos pères les emportent.

« Ils nous faut donc une politique infinie, atteignant les deux fonds du temps, qui conduisent mille millions d’hommes, de leurs pères à leurs fils, sans que les liens se brisent ou se brouillent. Là est l’immense direction sans désir. Vous nous jugez inertes. Nous conservons simplement la sagesse suffisante pour croître démesurément, au-delà de toute puissance humaine, et pour vous voir, malgré votre science furieuse, vous fondre dans les eaux pleines du pays du Thsin. Vous qui savez tant de choses, vous ignorez les plus antiques et les plus fortes, et vous désirez avec fureur ce qui est immédiat, et vous détruisez en même temps vos pères et vos fils.

« Doux, cruels, subtils ou barbares, nous étions ce qu’il faut à son heure. Nous ne voulons pas savoir trop. La science des hommes ne doit pas s’augmenter indéfiniment. Si elle s’étend toujours, elle cause un trouble incessant et elle se désespère elle-même. Si elle s’arrête, la décadence paraît. Mais, nous qui pensons à une durée plus forte que la force de l’Occident, nous évitons l’ivresse dévorante de sagesse. Nous gardons nos anciennes réponses, nos Dieux, nos étages de puissance. Si l’on n’avait conservé aux supérieurs, l’aide inépuisable des incertitudes de l’esprit, si, en détruisant la simplicité des hommes, on avait excité le désir en eux, et changé la notion qu’ils ont d’eux-mêmes – si les supérieurs étaient restés seuls dans une nature devenue mauvaise, vis-à-vis du nombre effrayant des sujets et de la violence des désirs – ils auraient succombé, et avec eux, toute la force de tout le pays. Mais notre écriture est trop difficile. Elle est politique. Elle renferme les idées. Ici, pour pouvoir penser, il faut connaître des signes nombreux ; seuls y parviennent les lettrés, au prix d’un labeur immense. Les autres ne peuvent réfléchir profondément, ni combiner leurs informes desseins. Ils sentent, mais le sentiment est toujours une chose enfermée. Tous les pouvoirs contenus dans l’intelligence restent donc aux lettrés, et un ordre inébranlable se fonde sur la difficulté et l’esprit.

« Rappelle-toi maintenant que vos grandes inventions eurent chez nous leur germe. Comprends-tu désormais pourquoi elles n’ont pas été poursuivies ? Leur perfection spéciale eût gâté notre lente et grande existence en troublant le régime simple de son cours. Tu vois qu’il ne faut pas nous mépriser, car, nous avons inventé la poudre, pour brandir, le soir, des fusées.

Je regarde. Le Chinois était déjà très petit sur le sable, regagnant les bosquets de l’intérieur. Je laisse passer quelques vagues. J’entends le mélange de tous les oiseaux légèrement bouillir dans la brise ou dans une vapeur d’arbustes, derrière moi et loin. La mer me soigne.

A quoi penser ? Pensai-je ? Que reste-t-il à saisir ? Où repousser ce qui maintenant me caresse, satisfaisant, habile, aisé ? Se mouvoir, en goûtant certaines difficultés, là-dedans, dans l’air ?… Tu me reposes, simple idée de me transporter si haut, et, au moindre élan, si près de toute pointe de vague qui crève ; ou d’arriver vers chaque chose infiniment peu désirée, avec nul effort, un temps imperceptible selon d’immenses trajets, amusants par eux-mêmes, si faciles, et revenir. Je suis attiré ; dans ce calme, ma plus petite idée se corrige, en se laissant, dans tout l’espace, se satisfaire, en improvisant tout de suite son exécution parfaite et le plaisir de se contenter qui la termine. Elle meurt chaque fois, ayant d’elle-même rétabli l’ensemble antérieur. Mais toute autre l’imite, et s’épuise pareille, voluptueusement, car le groupe de lumière et pensée qui dans ce moment me constitue, demeure encore identique. Alors, le changement est nul. Le temps ne marche plus. Ma vie se pose.

Presque rien ne me le fait sentir, puisque je reconquiers à chaque minute la précédente ; et mon esprit voltige à tous les points d’ici. Tout ce qui est possible est becqueté… Si tous les points de l’étendue d’ici se confondent successivement – si je puis en finir si vite avec ce qui continue –, si cette eau brillante qui tourne et s’enfonce comme une vis brillante dans le lointain de ma gauche –, si cette chute de neige dorée, mince, posée au large, en face . . .

Désormais, ouverte comme une huître, la mer me rafraîchit au soleil par l’éclat de sa chair grasse et humide : j’entends aussi l’eau, tout près, boire longuement, ou, dans les bois du phare, sauter à la corde, ou faire un bruit de poules.

Pour mieux l’écouter, je coupe le regard. Je baisse les paupières, et vois bouger bientôt deux ou trois petites fenêtres lumineuses, précieuses : des lunules orangées qui se contractent et sont sensibles ; une ombre où elles battent et m’aveuglent moi-même. Je veux reconstruire alors toute la vue que je viens de clore ; j’appelle les bleus nombreux, et les lignes fermées du tissu simple étendu sur une chose tremblante ; je fais une vague qui bouffe et qui m’élève . . .

Je n’en puis faire mille. Pourquoi ? Et la mer que je formais, disparaît. Déjà, je raisonne, et je trouve.

Rouvrons. Revenons au jour fixe. Ici il faut se laisser faire.

Les voilà toutes. Elles se roulent : je me roule. Elles murmurent je parle. Elles se brisent en fragments, elles se lèchent, elles retournent, elles flottent encore, elles moussent et me laissent mourant sur un sable baisé. Je revis au lointain dans le premier bruit du moindre qui ressuscite, au seuil du large. La force me revient. Nager contre elles – non, nager sur elles –, c’est la même chose ; debout dans l’eau où les pieds se perdent, le cœur en avant, les yeux fondus sans poids, sans corps . . .

L’individu, alors, sent profondément sa liaison avec ce qui se passe sous ses yeux, l’eau. (Paul Valéry, 1895)

Paul Valéry

(1871-1945)

Le Yalou

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #Short Stories Archive, Archive U-V, Archive U-V, Valéry, Paul

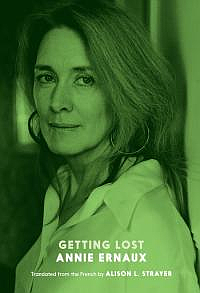

The 2022 Nobel prize in literature has been awarded to Annie Ernaux “for the courage and clinical acuity with which she uncovers the roots, estrangements and collective restraints of personal memory”.

Ernaux, who writes novels about daily life in France as well as non-fiction and is one of her country’s most acclaimed authors, had been among the favourites to win the prize.

Ernaux, who writes novels about daily life in France as well as non-fiction and is one of her country’s most acclaimed authors, had been among the favourites to win the prize.

Ernaux is the first French writer to win the Nobel since Patrick Modiano in 2014. She becomes the 16th French writer to have won the Nobel to date.

Anders Olsson, chair of the Nobel committee, said that in her work, “Ernaux consistently and from different angles, examines a life marked by strong disparities regarding gender, language and class”.

Ernaux was born in 1940 and grew up in the small town of Yvetot in Normandy. She studied at Rouen University, and later taught at secondary school.

From 1977 to 2000, she was a professor at the Centre National d’Enseignement par Correspondance. Olsson said her “path to authorship was long and arduous”.

Works

Works

Les Armoires vides, Paris, Gallimard, 1974; Gallimard, 1984.

Ce qu’ils disent ou rien, Paris, Gallimard, 1977; French & European Publications, Incorporated.

La Femme gelée, Paris, Gallimard, 1981; French & European Publications, Incorporated, 1987.

La Place, Paris, Gallimard, 1983; Distribooks Inc, 1992.

Une Femme, Paris, Gallimard, 1987.

Passion simple, Paris, Gallimard, 1991; Gallimard, 1993.

Journal du dehors, Paris, Gallimard, 1993.

La Honte, Paris, Gallimard, 1997.

Je ne suis pas sortie de ma nuit, Paris, Gallimard, 1997.

La Vie extérieure : 1993-1999, Paris, Gallimard, 2000.

L’Événement, Paris, Gallimard, 2000.

Se perdre, Paris, Gallimard, 2001.

L’Occupation, Paris, Gallimard, 2002.

L’Usage de la photo, with Marc Marie, Paris, Gallimard, 2005.

Les Années, Paris, Gallimard, 2008.

L’Autre fille, Paris, Nil 2011.

L’Atelier noir, Paris, éditions des Busclats, 2011.

Écrire la vie, Paris, Gallimard, 2011.

Retour à Yvetot, éditions du Mauconduit, 2013.

Regarde les lumières mon amour, Seuil, 2014.

Mémoire de fille, Gallimard, 2016.

Hôtel Casanova, Gallimard Folio, 2020.

Le jeune homme, Gallimard, 2022.

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #Short Stories Archive, - Book Lovers, Annie Ernaux, Archive E-F, Art & Literature News, Awards & Prizes

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature