Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Novalis

Das Gedicht

Himmlisches Leben im blauen Gewande

Stiller Wunsch in blassem Schein –

Flüchtig gräbt in bunten Sande

Sie den Zug des Namens ein –

Unter hohen festen Bogen

Nur von Lampenlicht erhellt

Liegt, seitdem der Geist entflogen

Nun das Heiligste der Welt.

Leise kündet beßre Tage

Ein verlornes Blatt uns an

Und wir sehn der alten Sage

Mächtige Augen aufgetan.

Naht euch stumm dem ernsten Tore,

Harrt auf seinen Flügelschlag

Und vernehmt herab vom Chore

Wo weissagend der Marmor lag.

Flüchtiges Leben und lichte Gestalten

Füllten die weite, leere Nacht

Nur von Scherzen aufgehalten

Wurden unendliche Zeiten verbracht –

Liebe brachte gefüllte Becher

Also perlt in Blumen der Geist

Ewig trinken die kindlichen Zecher

Bis der geheiligte Teppich zerreißt.

Fort durch unabsehliche Reihn

Schwanden die bunten rauschenden Wagen

Endlich von farbigen Käfern getragen

Kam die Blumenfürstin allein[.]

Schleier, wie Wolken zogen

Von der blendenden Stirn zu den Füßen

Wir fielen nieder sie zu grüßen

Wir weinten bald – sie war entflogen.

Novalis (1772 – 1801)

Gedicht: Das Gedicht

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive M-N, Novalis, Novalis

Hans Hermans© photos: Night

# more on website hans hermans

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Hans Hermans Photos, Photography

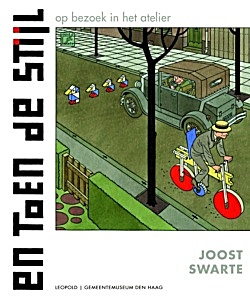

Nieuw kunstprentenboek over De Stijl door Joost Swarte

Nieuw kunstprentenboek over De Stijl door Joost Swarte

In 2017 is het honderd jaar geleden dat het tijdschrift De Stijl werd opgericht. Nederland viert dit met het feestjaar Mondriaan tot Dutch design. 100 jaar De Stijl. Met ’s werelds grootste Mondriaan-collectie – en tevens een van de grootste De Stijl-collecties – is het Gemeentemuseum Den Haag het middelpunt van dit feestelijke jaar. Op 11 februari trapt het museum dit jaar af met een tentoonstelling over de ontstaansgeschiedenis van een nieuwe kunst die de wereld voorgoed heeft veranderd. Bij Uitgeverij Leopold verschijnt op 11 februari het prentenboek dat Joost Swarte voor dit jubileumjaar maakte: En toen De Stijl.

Joost Swarte is Nederlands bekendste striptekenaar. Zijn werk is vertaald in het Engels, Frans, Spaans, Noors, Italiaans en Duits en zijn illustraties verschenen in toonaangevende magazines met The New Yorker als belangrijkste blikvanger. Naast striptekenaar is Swarte ook illustrator, architect en vormgever.

En toen De Stijl is een hommage aan de kunstenaars, architecten en ontwerpers die bij De Stijl betrokken waren of erdoor werden beïnvloed. Joost Swarte laat een kat een kijkje nemen in hun ateliers. Die zitten vol verwijzingen naar hun ontwikkeling: van de oprichting van De Stijl door Theo van Doesburg, tot de weg naar abstractie die Van der Leck doormaakte, de ultieme abstractie van Mondriaan, de meubels van Gerrit Rietveld, het door Rietveld geïnspireerde houten speelgoed van Ko Verzuu, tot het grafische werk en de bekende Bruynzeelkeuken van Piet Zwart. Een feest van ontdekking voor jong en oud. –

Joost Swarte:

En toen De Stijl.

Op bezoek in het atelier

Pagina’s 32

ISBN 978-90-258-7238-0

Prijs € 14,99

Uitg.Leopold

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Constructivism, Constuctivisme, De Stijl, Illustrators, Illustration, Piet Mondriaan, Piet Mondriaan, Theo van Doesburg, Theo van Doesburg

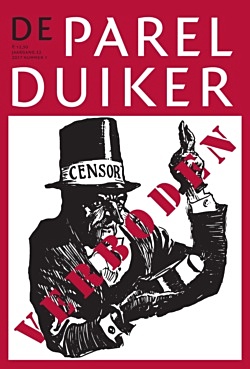

Boeken en kunstwerken kunnen om uiteenlopende redenen verboden vruchten worden. Wegens hun scabreuze karakter natuurlijk. Of om politiek ongewenste c.q. verwerpelijk geachte elementen.

Boeken en kunstwerken kunnen om uiteenlopende redenen verboden vruchten worden. Wegens hun scabreuze karakter natuurlijk. Of om politiek ongewenste c.q. verwerpelijk geachte elementen.

In de speciale Parelduiker zoomen we vier keer in op verboden boeken: de als pornografie bestempelde ‘realistische romans’ van Jan Brandts, de in beslag genomen realistische romans van Hugo Beersman, de als fascistisch gebrandmerkte kunstwerken van de Schotse kunstenaar Ian Hamilton Finlay en het toneelstuk Jan Pietersz. Coen van J. Slauerhoff.

Marco Entrop, Rendez-vous op ’t Tulpplein. Een verboden liefdesgeschiedenis

Nederland kon in de wederopbouw geen ondermijnende krachten gebruiken. Een steen des aanstoots was de pornografie. De schrijver Jan Brandts zag zich als een van de eersten geslachtofferd. Zijn in 1947 verschenen roman over de oprechte liefde tussen twee jonge mensen werd in beslag genomen, omdat ze het met elkaar deden.

Bert Sliggers, ‘Gretig gleden zijn handen over haar weelderige borsten’. De verboden realistische romans van Hugo Beersman

Hoewel er in 1914 al een Rijksbureau was dat de handel in ‘ontuchtige uitgaven’ moest tegengaan, duurde het nog tot 1930 voordat de rotte appels binnen de lectuur en literatuur grootscheeps werden opgespoord. Zo kon het gebeuren dat boeken die aan het begin van die eeuw zonder bemoeienis van de politie werden verhandeld en gelezen opeens in beslag werden genomen en de eigenaren bekeurd. Uitgever Jan Hilbingh Mulder, die een boekwinkel in de Amsterdamse Cornelis Schuytstraat dreef en boeken van Hugo Beersman uitgaf, werd door Justitie streng aangepakt.

Marco Daane, Osso? Oh, zo! Een Schotse tuinman, een Duits struikelblok en Franse houthakkers

Boeken en kunstwerken kunnen om uiteenlopende redenen verboden vruchten worden. Wegens hun scabreuze karakter natuurlijk – zie elders in dit nummer. Of om politiek ongewenste c.q. verwerpelijk geachte elementen, vooral antisemitische of nazistische. In de westerse cultuur komt dat eigenlijk niet eens zo vaak voor, maar is niet Hitlers eigen Mein Kampf formeel nog altijd verboden? Ook de Schotse kunstenaar Ian Hamilton Finlay ondervond in 1988 in Frankrijk hoe gevoelig dit thema is. Enkele Nederlanders en Vlamingen werden eveneens door de affaire beroerd.

Hein Aalders, Een ‘ploertig stuk’ en de openbare orde. De wereldpremière van Slauerhoffs Jan Pietersz. Coen

Uitvoeringen van Slauerhoffs toneelstuk Jan Pietersz. Coen (1931) stuitten keer op keer op bezwaren bij vooral burgemeesters, die opvoering ofwel verboden ofwel sterk ontrieden met een beroep op de openbare orde. Het stuk zou door zijn kritische kijk op de Hollandse koloniaal de Nederlandse politiek ten aanzien van Indonesië en Nieuw-Guinea kunnen verstoren. Uiteindelijk werd Slauerhoffs Jan Pietersz. Coen pas voor het eerst opgevoerd in 1961, door een Amsterdams studentengezelschap, maar slechts eenmalig en tijdens een besloten bijeenkomst.

Hans Olink, Berliner Beobachter: Theun de Vries in de DDR

Jan Paul Hinrichs, Schoon & haaks (over Joeri Olesja, Fritzi Harmsen van Beek, Frans Erens en J.M.A. Biesheuvel)

Paul Arnoldussen, De Laatste Pagina: Hubert van Herreweghen (1920-2016)

De Parelduiker is een uitgave van Uitgeverij Bas Lubberhuizen | Postbus 51140 | 1007 EC Amsterdam | T 020 618 41 32

Parelduikermiddag 25 maart in de Oba

De Parelduiker nodigt zijn abonnees, lezers en andere geïnteresseerden van harte uit voor een feestelijke Parelduikermiddag aan het begin van de Boekenweek, op zaterdag 25 maart van 16 tot 17.30 uur in de Openbare Bibliotheek Amsterdam (oba), Theater van het Woord, 7de etage (adres: Oosterdokskade 143, 1011 dl Amsterdam. Centraal staat: Jan Pietersz. Coen – een verboden toneelstuk van Slauerhoff

Vele malen werd een uitvoering van dit toneeldrama verboden. Pas in 1961 werd een eenmalige opvoering toegestaan. Spelers van toen vertellen erover. Scènes uit het gewraakte stuk worden gelezen en van commentaar voorzien.

M.m.v. Slauerhoff-biograaf Wim Hazeu, Hugo Koolschijn, Celia Nufaar, Ger Thijs, Krijn ter Braak, Paul Rutgers van der Loeff en Boudewijn Chabot. De middag wordt afgesloten door de dichteres Marieke Rijneveld (C. Buddingh’-prijs 2016), die voordraagt uit haar werk. Moderator: Anton de Goede.

De Parelduiker 2017/1

Themanummer: VERBODEN

# Meer informatie op website de parelduiker

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Stories, Art & Literature News, Boekenweek, Literary Events, LITERARY MAGAZINES, Magazines, Marco Entrop, Rijneveld, Marieke Lucas

The Los Amigos Fiasco

The Los Amigos Fiasco

by Arthur Conan Doyle

I used to be the leading practitioner of Los Amigos. Of course, everyone has heard of the great electrical generating gear there. The town is wide spread, and there are dozens of little townlets and villages all round, which receive their supply from the same centre, so that the works are on a very large scale. The Los Amigos folk say that they are the largest upon earth, but then we claim that for everything in Los Amigos except the gaol and the death-rate. Those are said to be the smallest.

Now, with so fine an electrical supply, it seemed to be a sinful waste of hemp that the Los Amigos criminals should perish in the old-fashioned manner. And then came the news of the eleotrocutions in the East, and how the results had not after all been so instantaneous as had been hoped. The Western Engineers raised their eyebrows when they read of the puny shocks by which these men had perished, and they vowed in Los Amigos that when an irreclaimable came their way he should be dealt handsomely by, and have the run of all the big dynamos. There should be no reserve, said the engineers, but he should have all that they had got. And what the result of that would be none could predict, save that it must be absolutely blasting and deadly. Never before had a man been so charged with electricity as they would charge him. He was to be smitten by the essence of ten thunderbolts. Some prophesied combustion, and some disintegration and disappearance. They were waiting eagerly to settle the question by actual demonstration, and it was just at that moment that Duncan Warner came that way.

Warner had been wanted by the law, and by nobody else, for many years. Desperado, murderer, train robber and road agent, he was a man beyond the pale of human pity. He had deserved a dozen deaths, and the Los Amigos folk grudged him so gaudy a one as that. He seemed to feel himself to be unworthy of it, for he made two frenzied attempts at escape. He was a powerful, muscular man, with a lion head, tangled black locks, and a sweeping beard which covered his broad chest. When he was tried, there was no finer head in all the crowded court. It’s no new thing to find the best face looking from the dock. But his good looks could not balance his bad deeds. His advocate did all he knew, but the cards lay against him, and Duncan Warner was handed over to the mercy of the big Los Amigos dynamos.

I was there at the committee meeting when the matter was discussed. The town council had chosen four experts to look after the arrangements. Three of them were admirable. There was Joseph M’Conner, the very man who had designed the dynamos, and there was Joshua Westmacott, the chairman of the Los Amigos Electrical Supply Company, Limited. Then there was myself as the chief medical man, and lastly an old German of the name of Peter Stulpnagel. The Germans were a strong body at Los Amigos, and they all voted for their man. That was how he got on the committee. It was said that he had been a wonderful electrician at home, and he was eternally working with wires and insulators and Leyden jars; but, as he never seemed to get any further, or to have any results worth publishing he came at last to be regarded as a harmless crank, who had made science his hobby. We three practical men smiled when we heard that he had been elected as our colleague, and at the meeting we fixed it all up very nicely among ourselves without much thought of the old fellow who sat with his ears scooped forward in his hands, for he was a trifle hard of hearing, taking no more part in the proceedings than the gentlemen of the press who scribbled their notes on the back benches.

We did not take long to settle it all. In New York a strength of some two thousand volts had been used, and death had not been instantaneous. Evidently their shock had been too weak. Los Amigos should not fall into that error. The charge should be six times greater, and therefore, of course, it would be six times more effective. Nothing could possibly be more logical. The whole concentrated force of the great dynamos should be employed on Duncan Warner.

So we three settled it, and had already risen to break up the meeting, when our silent companion opened his month for the first time.

“Gentlemen,” said he, “you appear to me to show an extraordinary ignorance upon the subject of electricity. You have not mastered the first principles of its actions upon a human being.”

The committee was about to break into an angry reply to this brusque comment, but the chairman of the Electrical Company tapped his forehead to claim its indulgence for the crankiness of the speaker.

“Pray tell us, sir,” said he, with an ironical smile, “what is there in our conclusions with which you find fault?”

“With your assumption that a large dose of electricity will merely increase the effect of a small dose. Do you not think it possible that it might have an entirely different result? Do you know anything, by actual experiment, of the effect of such powerful shocks?”

“We know it by analogy,” said the chairman, pompously. “All drugs increase their effect when they increase their dose; for example—for example——”

“Whisky,” said Joseph M’Connor.

“Quite so. Whisky. You see it there.”

Peter Stulpnagel smiled and shook his head.

“Your argument is not very good,” said he. “When I used to take whisky, I used to find that one glass would excite me, but that six would send me to sleep, which is just the opposite. Now, suppose that electricity were to act in just the opposite way also, what then?”

We three practical men burst out laughing. We had known that our colleague was queer, but we never had thought that he would be as queer as this.

“What then?” repeated Philip Stulpnagel.

“We’ll take our chances,” said the chairman.

“Pray consider,” said Peter, “that workmen who have touched the wires, and who have received shocks of only a few hundred volts, have died instantly. The fact is well known. And yet when a much greater force was used upon a criminal at New York, the man struggled for some little time. Do you not clearly see that the smaller dose is the more deadly?”

“I think, gentlemen, that this discussion has been carried on quite long enough,” said the chairman, rising again. “The point, I take it, has already been decided by the majority of the committee, and Duncan Warner shall be electrocuted on Tuesday by the full strength of the Los Amigos dynamos. Is it not so?”

“I agree,” said Joseph M’Connor.

“I agree,” said I.

“And I protest,” said Peter Stulpnagel.

“Then the motion is carried, and your protest will be duly entered in the minutes,” said the chairman, and so the sitting was dissolved.

The attendance at the electrocution was a very small one. We four members of the committee were, of course, present with the executioner, who was to act under their orders. The others were the United States Marshal, the governor of the gaol, the chaplain, and three members of the press. The room was a small brick chamber, forming an outhouse to the Central Electrical station. It had been used as a laundry, and had an oven and copper at one side, but no other furniture save a single chair for the condemned man. A metal plate for his feet was placed in front of it, to which ran a thick, insulated wire. Above, another wire depended from the ceiling, which could be connected with a small metallic rod projecting from a cap which was to be placed upon his head. When this connection was established Duncan Warner’s hour was come.

There was a solemn hush as we waited for the coming of the prisoner. The practical engineers looked a little pale, and fidgeted nervously with the wires. Even the hardened Marshal was ill at ease, for a mere hanging was one thing, and this blasting of flesh and blood a very different one. As to the pressmen, their faces were whiter than the sheets which lay before them. The only man who appeared to feel none of the influence of these preparations was the little German crank, who strolled from one to the other with a smile on his lips and mischief in his eyes. More than once he even went so far as to burst into a shout of laughter, until the chaplain sternly rebuked him for his ill-timed levity.

“How can you so far forget yourself, Mr. Stulpnagel,” said he, “as to jest in the presence of death?”

But the German was quite unabashed.

“If I were in the presence of death I should not jest,” said he, “but since I am not I may do what I choose.”

This flippant reply was about to draw another and a sterner reproof from the chaplain, when the door was swung open and two warders entered leading Duncan Warner between them. He glanced round him with a set face, stepped resolutely forward, and seated himself upon the chair.

“Touch her off!” said he.

It was barbarous to keep him in suspense. The chaplain murmured a few words in his ear, the attendant placed the cap upon his head, and then, while we all held our breath, the wire and the metal were brought in contact.

“Great Scott!” shouted Duncan Warner.

He had bounded in his chair as the frightful shock crashed through his system. But he was not dead. On the contrary, his eyes gleamed far more brightly than they had done before. There was only one change, but it was a singular one. The black had passed from his hair and beard as the shadow passes from a landscape. They were both as white as snow. And yet there was no other sign of decay. His skin was smooth and plump and lustrous as a child’s.

The Marshal looked at the committee with a reproachful eye.

“There seems to be some hitch here, gentlemen,” said he.

We three practical men looked at each other.

Peter Stulpnagel smiled pensively.

“I think that another one should do it,” said I.

Again the connection was made, and again Duncan Warner sprang in his chair and shouted, but, indeed, were it not that he still remained in the chair none of us would have recognised him. His hair and his beard had shredded off in an instant, and the room looked like a barber’s shop on a Saturday night. There he sat, his eyes still shining, his skin radiant with the glow of perfect health, but with a scalp as bald as a Dutch cheese, and a chin without so much as a trace of down. He began to revolve one of his arms, slowly and doubtfully at first, but with more confidence as he went on.

Again the connection was made, and again Duncan Warner sprang in his chair and shouted, but, indeed, were it not that he still remained in the chair none of us would have recognised him. His hair and his beard had shredded off in an instant, and the room looked like a barber’s shop on a Saturday night. There he sat, his eyes still shining, his skin radiant with the glow of perfect health, but with a scalp as bald as a Dutch cheese, and a chin without so much as a trace of down. He began to revolve one of his arms, slowly and doubtfully at first, but with more confidence as he went on.

“That jint,” said he, “has puzzled half the doctors on the Pacific Slope. It’s as good as new, and as limber as a hickory twig.”

“You are feeling pretty well?” asked the old German.

“Never better in my life,” said Duncan Warner cheerily.

The situation was a painful one. The Marshal glared at the committee. Peter Stulpnagel grinned and rubbed his hands. The engineers scratched their heads. The bald-headed prisoner revolved his arm and looked pleased.

“I think that one more shock——” began the chairman.

“No, sir,” said the Marshal “we’ve had foolery enough for one morning. We are here for an execution, and a execution we’ll have.”

“What do you propose?”

“There’s a hook handy upon the ceiling. Fetch in a rope, and we’ll soon set this matter straight.”

There was another awkward delay while the warders departed for the cord. Peter Stulpnagel bent over Duncan Warner, and whispered something in his ear. The desperado started in surprise.

“You don’t say?” he asked.

The German nodded.

“What! Noways?”

Peter shook his head, and the two began to laugh as though they shared some huge joke between them.

The rope was brought, and the Marshal himself slipped the noose over the criminal’s neck. Then the two warders, the assistant and he swung their victim into the air. For half an hour he hung—a dreadful sight—from the ceiling. Then in solemn silence they lowered him down, and one of the warders went out to order the shell to be brought round. But as he touched ground again what was our amazement when Duncan Warner put his hands up to his neck, loosened the noose, and took a long, deep breath.

“Paul Jefferson’s sale is goin’ well,” he remarked, “I could see the crowd from up yonder,” and he nodded at the hook in the ceiling.

“Up with him again!” shouted the Marshal, “we’ll get the life out of him somehow.”

In an instant the victim was up at the hook once more.

They kept him there for an hour, but when he came down he was perfectly garrulous.

“Old man Plunket goes too much to the Arcady Saloon,” said he. “Three times he’s been there in an hour; and him with a family. Old man Plunket would do well to swear off.”

It was monstrous and incredible, but there it was. There was no getting round it. The man was there talking when he ought to have been dead. We all sat staring in amazement, but United States Marshal Carpenter was not a man to be euchred so easily. He motioned the others to one side, so that the prisoner was left standing alone.

“Duncan Warner,” said he, slowly, “you are here to play your part, and I am here to play mine. Your game is to live if you can, and my game is to carry out the sentence of the law. You’ve beat us on electricity. I’ll give you one there. And you’ve beat us on hanging, for you seem to thrive on it. But it’s my turn to beat you now, for my duty has to be done.”

He pulled a six-shooter from his coat as he spoke, and fired all the shots through the body of the prisoner. The room was so filled with smoke that we could see nothing, but when it cleared the prisoner was still standing there, looking down in disgust at the front of his coat.

“Coats must be cheap where you come from,” said he. “Thirty dollars it cost me, and look at it now. The six holes in front are bad enough, but four of the balls have passed out, and a pretty state the back must be in.”

The Marshal’s revolver fell from his hand, and he dropped his arms to his sides, a beaten man.

“Maybe some of you gentlemen can tell me what this means,” said he, looking helplessly at the committee.

Peter Stulpnagel took a step forward.

“I’ll tell you all about it,” said he.

“You seem to be the only person who knows anything.”

“I AM the only person who knows anything. I should have warned these gentlemen; but, as they would not listen to me, I have allowed them to learn by experience. What you have done with your electricity is that you have increased this man’s vitality until he can defy death for centuries.”

“Centuries!”

“Yes, it will take the wear of hundreds of years to exhaust the enormous nervous energy with which you have drenched him. Electricity is life, and you have charged him with it to the utmost. Perhaps in fifty years you might execute him, but I am not sanguine about it.”

“Great Scott! What shall I do with him?” cried the unhappy Marshal.

Peter Stulpnagel shrugged his shoulders.

“It seems to me that it does not much matter what you do with him now,” said he.

“Maybe we could drain the electricity out of him again. Suppose we hang him up by the heels?”

“No, no, it’s out of the question.”

“Well, well, he shall do no more mischief in Los Amigos, anyhow,” said the Marshal, with decision. “He shall go into the new gaol. The prison will wear him out.”

“On the contrary,” said Peter Stulpnagel, “I think that it is much more probable that he will wear out the prison.”

It was rather a fiasco and for years we didn’t talk more about it than we could help, but it’s no secret now and I thought you might like to jot down the facts in your case-book.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859 – 1930)

Round the Red Lamp: Being Facts and Fancies of Medical Life

The Los Amigos Fiasco (#13)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Doyle, Arthur Conan, Doyle, Arthur Conan, DRUGS & DISEASE & MEDICINE & LITERATURE, Round the Red Lamp

G.K. Chesterton

A Ballade of Suicide

The gallows in my garden, people say,

Is new and neat and adequately tall;

I tie the noose on in a knowing way

As one that knots his necktie for a ball;

But just as all the neighbours on the wall

Are drawing a long breath to shout “Hurray!”

The strangest whim has seized me. . . After all

I think I will not hang myself to-day.

To-morrow is the time I get my pay

My uncle’s sword is hanging in the hall

I see a little cloud all pink and grey

Perhaps the rector’s mother will NOT call

I fancy that I heard from Mr. Gall

That mushrooms could be cooked another way

I never read the works of Juvenal

I think I will not hang myself to-day.

The world will have another washing-day;

The decadents decay; the pedants pall;

And H.G. Wells has found that children play,

And Bernard Shaw discovered that they squall;

Rationalists are growing rational

And through thick woods one finds a stream astray,

So secret that the very sky seems small

I think I will not hang myself to-day.

ENVOI

Prince, I can hear the trumpet of Germinal,

The tumbrils toiling up the terrible way;

Even to-day your royal head may fall

I think I will not hang myself to-day.

G. K. Chesterton (1874 – 1936)

A Ballade of Suicide

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Chesterton, Gilbert Keith, G.K. Chesterton, Suicide

Rainer Maria Rilke

(1875 – 1926)

Musik

Wüsste ich für wen ich spiele, ach!

immer könnt ich rauschen wie der Bach.

Ahnte ich, ob tote Kinder gern

tönen hören meinen innern Stern;

ob die Mädchen, die vergangen sind,

lauschend wehn um mich im Abendwind.

Ob ich einem, welcher zornig war,

leise streife durch das Totenhaar…

Denn was wär Musik, wenn sie nicht ging

weit hinüber über jedes Ding.

Sie, gewiss, die weht, sie weiss es nicht,

wo uns die Verwandlung unterbricht.

Dass uns Freunde hören, ist wohl gut -,

aber sie sind nicht so ausgeruht

wie die Andern, die man nicht mehr sieht:

tiefer fühlen sie ein Lebens-Lied,

weil sie wehen unter dem, was weht,

und vergehen, wenn der Ton vergeht.

Rainer Maria Rilke Gedichte

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive Q-R, MUSIC, Rilke, Rainer Maria

William Blake

London

I wander thro’ each charter’d street,

Near where the charter’d Thames does flow,

And mark in every face I meet

Marks of weakness, marks of woe.

In every cry of every Man,

In every Infant’s cry of fear,

In every voice, in every ban,

The mind-forg’d manacles I hear.

How the Chimney-sweeper’s cry

Every black’ning Church appalls;

And the hapless Soldier’s sigh

Runs in blood down Palace walls.

But most thro’ midnight streets I hear

How the youthful Harlot’s curse

Blasts the new born Infant’s tear,

And blights with plagues the Marriage hearse.

William Blake (1757 – 1827)

Poem: London

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Blake, William

Oscar Wilde

(1854 – 1900)

Les Silhouettes

The sea is flecked with bars of grey,

The dull dead wind is out of tune,

And like a withered leaf the moon

Is blown across the stormy bay.

Etched clear upon the pallid sand

Lies the black boat: a sailor boy

Clambers aboard in careless joy

With laughing face and gleaming hand.

And overhead the curlews cry,

Where through the dusky upland grass

The young brown-throated reapers pass,

Like silhouettes against the sky.

Oscar Wilde

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive W-X, Wilde, Oscar, Wilde, Oscar

Emile Verhaeren

Vénus

Vénus,

La joie est morte au jardin de ton corps

Et les grands lys des bras et les glaïeuls des lèvres

Et les grappes de gloire et d’or,

Sur l’espalier mouvant que fut ton corps,

ont morts.

Les cormorans des temps d’octobre ont laissé choir

Plume à plume, leur deuil, au jardin de tes charmes ;

Mélancoliques, les soirs

Ont laissé choir

Leur deuil, sur tes flambeaux et sur tes armes.

Hélas ! Tant d’échos morts et mortes tant de voix !

Au loin, là-bas, sur l’horizon de cendre rouge,

Un Christ élève au ciel ses bras en croix :

Miserere par les grands soirs et les grands bois !

Vénus,

Sois doucement l’ensevelie,

Dans la douceur et la mélancolie

Et dans la mort du jardin clair ;

Mais que dans l’air

Persiste à s’exalter l’odeur immense de ta chair.

Tes yeux étaient dardés, comme des feux d’ardeur,

Vers les étoiles éternelles ;

Et les flammes de tes prunelles

Définissaient l’éternité, par leur splendeur.

Tes mains douces, comme du miel vermeil,

Cueillaient, divinement, sur les branches de l’heure,

Les fruits de la jeunesse à son éveil ;

Ta chevelure était un buisson de soleil ;

Ton torse, avec ses feux de clartés rondes,

Semblait un firmament d’astres puissants et lourds ;

Et quand tes bras serraient, contre ton coeur, l’Amour,

Le rythme de tes seins rythmait l’amour du monde.

Sur l’or des mers, tu te dressais, tel un flambeau.

Tu te donnais à tous comme la terre,

Avec ses fleurs, ses lacs, ses monts, ses renouveaux

Et ses tombeaux.

Mais aujourd’hui que sont venus

D’autres désirs de l’Inconnu,

Sois doucement, Vénus, la triste et la perdue,

Au jardin mort, parmi les bois et les parfums,

Avec, sur ton sommeil, la douceur suspendue

D’une fleur, par l’automne et l’ouragan, tordue.

Tes mains douces, comme du miel vermeil,

Cueillaient, divinement, sur les branches de l’heure,

Les fruits de la jeunesse à son éveil ;

Ta chevelure était un buisson de soleil ;

Ton torse, avec ses feux de clartés rondes,

Semblait un firmament d’astres puissants et lourds ;

Et quand tes bras serraient, contre ton coeur, l’Amour,

Le rythme de tes seins rythmait l’amour du monde.

Sur l’or des mers, tu te dressais, tel un flambeau.

Tu te donnais à tous comme la terre,

Avec ses fleurs, ses lacs, ses monts, ses renouveaux

Et ses tombeaux.

Mais aujourd’hui que sont venus

D’autres désirs de l’Inconnu,

Sois doucement, Vénus, la triste et la perdue,

Au jardin mort, parmi les bois et les parfums,

Avec, sur ton sommeil, la douceur suspendue

D’une fleur, par l’automne et l’ouragan, tordue.

Emile Verhaeren (1855-1916) poésie

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive U-V, Verhaeren, Emile

Ton van Reen schreef de roman ‘Geen Oorlog’ toen hij 23 jaar oud was. Overtuigend beschrijft hij het leven van Jarde, een joodse jongen, in drie verschillende levensfasen. ‘Geen Oorlog’ is naast een roman over vervreemding, een scherpe kritiek op de moderne maatschappij, waarin iedereen langs elkaar heen leeft en waarin geen plaats is voor dromers.

Ton van Reen schreef de roman ‘Geen Oorlog’ toen hij 23 jaar oud was. Overtuigend beschrijft hij het leven van Jarde, een joodse jongen, in drie verschillende levensfasen. ‘Geen Oorlog’ is naast een roman over vervreemding, een scherpe kritiek op de moderne maatschappij, waarin iedereen langs elkaar heen leeft en waarin geen plaats is voor dromers.

Dagblad De Limburger: ‘Een dichterlijke aanklacht tegen de oorlog en de vernietiging van het individu, geschreven in heldere beeldende taal, door een fascinerend natuurtalent.’ De Volkskrant: ‘Van Reen schrijft in een heel mooi Nederlands met een zuidelijk taalgebruik, dat randstedelingen soms vreemd zal voorkomen maar dat een warme klankkleur geeft aan zijn werk.’ Deze uitgave van ‘Geen Oorlog’, met het oorspronkelijke omslag en in de originele vormgeving, verschijnt vijftig jaar na de eerste uitgave, ter gelegenheid van de vijfenzeventigste verjaardag van de schrijver.

Ton van Reen is schrijver en journalist. Hij schrijft romans, jeugdromans en kinderboeken. Hij is oprichter van de Stichting Lalibela in Ethiopië die vooral gehandicapte kinderen en dakloze ouderen helpt. Hij verblijft vaak in Afrika. Zijn bekendste boek voor de jeugd is ‘De bende van de bokkenrijders’ dat verfilmd werd tot een tv-serie. Zijn verzameld prozawerk, zeventien romans, novellen en verhalenbundels, verscheen in 2010 in twee delen, samen 1800 bladzijden, bij Uitgeverij De Geus. Bij Uitgeverij De Contrabas verschenen zijn verzamelde gedichten met de titel ‘Blijvend vers’. In voorjaar 2016 verscheen zijn nieuwe roman ‘De verdwenen stad’ bij Uitgeverij In de Knipscheer.

Ton van Reen

Geen oorlog

Roman

Nederland

Paperback, 160 blz., € 8,90

ISBN 978-90-6265-922-7

Heruitgave (6de druk) 2016

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van, Ton van Reen

Wakker

Met verbazing werden ze wakker na een gebed

met een end. Hoe makkelijk raadselen zich

laten vinden. In petto oud Latijn voor trage

jarentellers, dagbelevers, slapers in de lange,

lange heuvelnachten. Natuurlijk passen ze

op het huis van vrienden. Braaf is het. Graag

vertellen ze over bomen prachtige verhalen.

Bert Bevers

Uit Andere taal, Uitgeverij Litera Este, Borgerhout, 2010

Bert Bevers gedichten

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Bevers, Bert

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature