Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Dioraphte Literatour Prijs

De Dioraphte Literatour Prijs bestaat uit een vakjuryprijs en een publieksprijs waarbij jongeren worden opgeroepen te stemmen op genomineerde boeken van de vakjury.

De beste boeken uit 2015 worden door de vakjury uitgelicht en bekroond. De DLP richt zich op alle jongeren van 15-18 jaar.

Je kunt op de website literatour.nu stemmen van 5 t/m 15 september 2016

De genomineerden in de categorie Oorspronkelijk Nederlandstalig zijn:

De genomineerden in de categorie Oorspronkelijk Nederlandstalig zijn:

De IJsmakers van Ernest van der Kwast (De Bezige Bij)

De zee zien van Koos Meinderts (De Fontein)

Het bestand van Arnon Grunberg (Nijgh & Van Ditmar)

Het uur van Zimmerman van Karolien Berkvens (Lebowski)

Oliver van Edward van de Vendel (Querido)

Underdog van Elfie Tromp (De Geus)

In de categorie Vertaald zijn genomineerd:

De naam van mijn broer van Larry Tremblay (Nieuw Amsterdam) en vertaald door Gertrud Maes

Doorgang van David Mitchell (Nieuw Amsterdam) en vertaald door Harm Damsma

Waar het licht is van Jennifer Niven (Moon) en vertaald door Aleid van Eekelen-Benders

Vuur & as van Sabaa Tahir (Luitingh-Sijthoff) en vertaald door Hanneke van Soest

Eerdere winnaars:

In 2015 ging de Dioraphte Literatour Prijs naar De veteraan van Johan Faber (Oorspronkelijk Nederlandstalig), Eleanor & Park van Rainbow Rowell (Vertaald) en Birk van Jaap Robben (Publieksprijs).

Nog meer verhalen:

Nog meer verhalen:

3PAK is een verhalenbundel met drie korte verhalen die speciaal geschreven zijn voor Literatour. Mirjam Mous, Helen Vreeswijk en Alex Boogers zijn de auteurs van de verhalen. De eerste twee verhalen worden online verspreid, het complete 3PAK is te verkrijgen bij de deelnemende bibliotheken & boekhandels.

Verhalen:

Domino Day – Mirjam Mous

De Rebel – Helen Vreeswijk

Vergeet Amy – Alex Boogers

Docenten opgelet:

Bij Literatour & 3Pak zijn er mogelijkheden tot klassikale lessen. Hiervoor kunt u terecht op de Voor Scholen pagina van de website van Literatour.

# Meer info op website Literatour

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, - Book News, - Bookstores, Art & Literature News, Elfie Tromp, FICTION & NONFICTION ARCHIVE, Literary Events

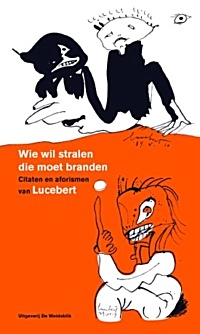

‘Alles van waarde is weerloos’, staat er in grote neonletters op het dak van een Nederlandse verzekeraar. Het is een tot aforisme, zelfs tot spreekwoord geworden versregel van Lucebert.

‘Alles van waarde is weerloos’, staat er in grote neonletters op het dak van een Nederlandse verzekeraar. Het is een tot aforisme, zelfs tot spreekwoord geworden versregel van Lucebert.

Lucebert werd en wordt weleens getypeerd als een ontoegankelijk dichter. Des te opmerkelijker is het hoeveel sporen hij heeft achtergelaten in de omgangstaal. In tal van niet-literaire teksten wordt onnadrukkelijk of juist expliciet verwezen naar passages uit zijn gedichten: ‘de ruimte van het volledig leven’, ‘omroeper van oproer’, ‘dichters van fluweel’, ‘het proefondervindelijk gedicht’, ‘de blote kont van de kunst’, ‘ritselende revolutie’, ‘overal zanikt bagger’ – het is maar een greep uit het dichterlijk erfgoed van Lucebert dat zich in de omgangstaal heeft genesteld.

In Wie wil stralen die moet branden zijn deze citaten en aforismen uit het oeuvre van Lucebert bijeengebracht door Ton den Boon (hoofdredacteur van de Dikke Van Dale), die daarbij een inleiding schreef over de invloed van Lucebert op de Nederlandse taal. Het boekje is verlucht met niet eerder gepubliceerde tekeningen van Lucebert.

Wie wil stralen die moet branden.

Citaten en aforismen van Lucebert – Lucebert, Ton den Boon

Auteurs: Lucebert, Ton den Boon

Vormgeving: Huug Schipper, Studio Tint

Omvang: 96 pagina’s

Afwerking: paperback

Formaat: 12 x 20 cm

ISBN: 9789077767658

€ 7,50

Verschijning: september 2016, De Weideblik

De Weideblik is een middelgrote uitgeverij, gespecialiseerd in uitgaven op het gebied van de beeldende kunst. Veel van onze boeken worden gemaakt in nauwe samenwerking met een kunstenaar (of diens nazaten) en/of een tentoonstellingsinstelling.

# Meer info website Uitgeverij Weideblik

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive K-L, Lucebert, Lucebert

Fotoweek benoemt Robin de Puy (1986) tot vierde Fotograaf des Vaderlands, als opvolger van Ahmet Polat.

Fotoweek benoemt Robin de Puy (1986) tot vierde Fotograaf des Vaderlands, als opvolger van Ahmet Polat.

De Fotograaf des Vaderlands is een jaar lang de ambassadeur van Fotoweek en het gezicht van de Nederlandse professionele fotografie. Rond het thema van Fotoweek 2016 ‘Kijk! Dit ben ik’ maakt de Fotograaf des Vaderlands, speciaal voor Fotoweek, een bijzondere fotoserie die wordt getoond tijdens het tweejaarlijkse internationale fotofestival BredaPhoto dat dit jaar plaatsvindt van 15 september tot 30 oktober.

De foto’s van de Nederlandse portretfotograaf Robin de Puy zijn altijd intiem en vol leven. Haar stijl is karakteristiek: zwart-wit, en balancerend op de rand van documentairefotografie. Haar werk is vaak een combinatie van fotografie en film, want; taal en beweging zijn voor de Puy een essentieel onderdeel van identiteit.

Fotoweek is trots Robin de Puy te presenteren als vierde Fotograaf des Vaderlands. Ze is een fotograaf met een succesvolle carrière, een perfect boegbeeld voor het vak fotografie. Vanwege de Puy’s aansprekende talent om karakters bloot te leggen, kijkt Fotoweek uit naar haar nieuwe serie in het thema van 2016 ‘Kijk! Dit ben ik’.

Voor Fotoweek maakt de Puy een intiem portret van de oom van haar vader, Jan Mallan, een 81-jarige man met Alzheimer. Ze heeft een warme band met deze man, die begin jaren zestig met zijn Deense vrouw naar Denemarken verhuisde. Ze was naar eigen zeggen bang om hem te verliezen, bang dat zijn uniciteit verloren zou gaan door de ziekte. Maar wat neemt de ziekte precies weg van zijn identiteit? Wat komt ervoor in de plaats?

Op 15 september worden de fotoserie en film onthuld in een tentoonstelling op het internationale fotofestival BredaPhoto. Het thema van BredaPhoto 2016 is ‘YOU’. Een interessante combinatie met het thema van de Fotoweek, want wat is een ‘ík’, zonder een ‘jij’?

Biografie Robin de Puy

Robin de Puy (1986) studeerde in 2009 af aan de Fotoacademie Rotterdam. Vanaf deze periode nam haar carrière een spurt en won zij met haar serie ‘Meisjes in de prostitutie’ in 2009 de Photo Academy Award. Vervolgens won zij In 2013 de Nationale Portretprijs en was haar eerste solotentoonstelling in het Fotomuseum Den Haag. Haar werk is gepubliceerd in nationale en internationale bladen, waaronder New York Magazine, Bloomberg Businessweek, ELLE, L’Officiel, de Volkskrant en LINDA.

Thema Fotoweek 2016: ‘Kijk: Dit ben ik’

Met het thema van dit jaar, ‘Kijk! Dit ben ik’, wordt de nadruk gelegd op portretfotografie. En op de wisselwerking tussen de geportretteerde en de fotograaf. Wie ben jij? Hoe kijk je naar jezelf? Wat wil je van jezelf laten zien? Weerspiegelt jouw portret je ware ik, of is dat slechts het beeld dat de fotograaf van je heeft? Hoeveel van zichzelf kan de fotograaf overbrengen in het portret van een ander? Fotoweek legt de focus op het individu: zowel voor als achter de lens.

Tijdens de Fotoweek zullen verschillende instellingen pop-up studio’s organiseren waar bezoekers hun portret kunnen laten maken door bekende en onbekende portretfotografen. Verder zijn er activiteiten en programma’s in verschillende musea en culturele instellingen, zoals het Groninger Museum, het Joods Historisch Museum, de Kunsthal Rotterdam, het Nationaal Archief in Den Haag en het Nieuwe Instituut. Bezoek deze zomer onze website www.defotoweek.nl voor een overzicht van de diverse activiteiten.

Fotograaf des Vaderlands: een traditie

In 2013 benoemde Fotoweek Ilvy Njiokiktjien tot de eerste Fotograaf des Vaderlands. Zij maakte voor het thema ‘Kijk! Mijn Familie’ een fotoserie over Hollandse verjaardagen. In 2014 werd Njiokiktjien opgevolgd door Koen Hauser. Voor Fotoweek 2014 maakte Hauser een fotoserie passend bij het thema ‘Kijk! Mijn Geluk’ die tijdens Fotoweek 2014 onthuld werd en te zien was bij het internationale fotografiefestival BredaPhoto. De huidige Fotograaf des Vaderlands, Ahmet Polat, zal op woensdag 7 september 2016 opgevolgd worden door een nieuwe Fotograaf des Vaderlands.

Van vrijdag 9 t/m zondag 18 september 2016, vindt de vierde editie van Fotoweek plaats. Tien dagen lang zet Fotoweek de schijnwerpers op fotografie. De start van Fotoweek wordt gemarkeerd door de bekendmaking van de nieuwe Fotograaf des Vaderlands op 7 september. Het thema dit jaar is ‘Kijk! Dit ben ik’.

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Art & Literature News, FDM Art Gallery, Photography, PRESS & PUBLISHING, Robin de Puy

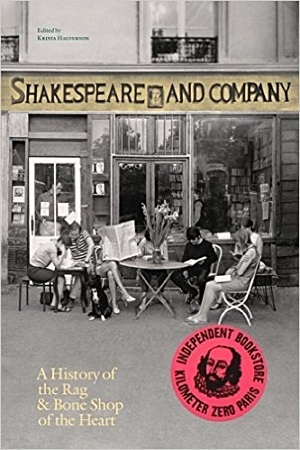

A Biography of a Bookstore – Shakespeare and Company, Paris: A History of the Rag & Bone Shop of the Heart – by Krista Halverson (Editor) – Sylvia Whitman (Afterword) – Jeannette Winterson (Foreword)

A Biography of a Bookstore – Shakespeare and Company, Paris: A History of the Rag & Bone Shop of the Heart – by Krista Halverson (Editor) – Sylvia Whitman (Afterword) – Jeannette Winterson (Foreword)

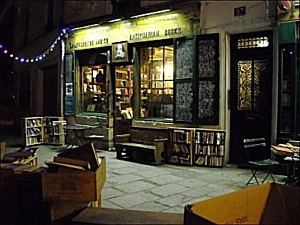

A copiously illustrated account of the famed Paris bookstore on its 65th anniversary.

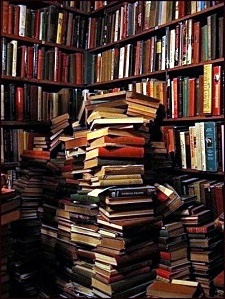

For almost 70 years, Shakespeare and Company has been a home-away-from-home for celebrated writers—including James Baldwin, Jorge Luis Borges, A. M. Homes, and Dave Eggers—as well as for young, aspiring authors and poets. Visitors are invited to read in the library, share a pot of tea, and sometimes even live in the shop itself, sleeping in beds tucked among the towering shelves of books. Since 1951, more than 30,000 have slept at the “rag and bone shop of the heart.”

This first-ever history of the legendary bohemian bookstore in Paris interweaves essays and poetry from dozens of writers associated with the shop–Allen Ginsberg, Anaïs Nin, Ethan Hawke, Robert Stone and Jeanette Winterson, among others–with hundreds of never-before-seen archival pieces, including photographs of James Baldwin, William Burroughs and Langston Hughes, plus a foreword by the celebrated British novelist Jeanette Winterson and an epilogue by Sylvia Whitman, the daughter of the store’s founder, George Whitman. The book has been edited by Krista Halverson, director of the newly founded Shakespeare and Company publishing house.

This first-ever history of the legendary bohemian bookstore in Paris interweaves essays and poetry from dozens of writers associated with the shop–Allen Ginsberg, Anaïs Nin, Ethan Hawke, Robert Stone and Jeanette Winterson, among others–with hundreds of never-before-seen archival pieces, including photographs of James Baldwin, William Burroughs and Langston Hughes, plus a foreword by the celebrated British novelist Jeanette Winterson and an epilogue by Sylvia Whitman, the daughter of the store’s founder, George Whitman. The book has been edited by Krista Halverson, director of the newly founded Shakespeare and Company publishing house.

George Whitman opened his bookstore in a tumbledown 16th-century building just across the Seine from Notre-Dame in 1951, a decade after the original Shakespeare and Company had closed. Run by Sylvia Beach, it had been the meeting place for the Lost Generation and the first publisher of James Joyce’s Ulysses. (This book includes an illustrated adaptation of Beach’s memoir.) Since Whitman picked up the mantle, Shakespeare and Company has served as a home-away-from-home for many celebrated writers, from Jorge Luis Borges to Ray Bradbury, A.M. Homes to Dave Eggers, as well as for young authors and poets. Visitors are invited not only to read the books in the library and to share a pot of tea, but sometimes also to live in the bookstore itself–all for free.

George Whitman opened his bookstore in a tumbledown 16th-century building just across the Seine from Notre-Dame in 1951, a decade after the original Shakespeare and Company had closed. Run by Sylvia Beach, it had been the meeting place for the Lost Generation and the first publisher of James Joyce’s Ulysses. (This book includes an illustrated adaptation of Beach’s memoir.) Since Whitman picked up the mantle, Shakespeare and Company has served as a home-away-from-home for many celebrated writers, from Jorge Luis Borges to Ray Bradbury, A.M. Homes to Dave Eggers, as well as for young authors and poets. Visitors are invited not only to read the books in the library and to share a pot of tea, but sometimes also to live in the bookstore itself–all for free.

More than 30,000 people have stayed at Shakespeare and Company, fulfilling Whitman’s vision of a “socialist utopia masquerading as a bookstore.” Through the prism of the shop’s history, the book traces the lives of literary expats in Paris from 1951 to the present, touching on the Beat Generation, civil rights, May ’68 and the feminist movement–all while pondering that perennial literary question, “What is it about writers and Paris?”

In this first-ever history of the bookstore, photographs and ephemera are woven together with personal essays, diary entries, and poems from writers including Allen Ginsberg, Anaïs Nin, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Sylvia Beach, Nathan Englander, Dervla Murphy, Jeet Thayil, David Rakoff, Ian Rankin, Kate Tempest, and Ethan Hawke.

In this first-ever history of the bookstore, photographs and ephemera are woven together with personal essays, diary entries, and poems from writers including Allen Ginsberg, Anaïs Nin, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Sylvia Beach, Nathan Englander, Dervla Murphy, Jeet Thayil, David Rakoff, Ian Rankin, Kate Tempest, and Ethan Hawke.

With hundreds of images, it features Tumbleweed autobiographies, precious historical documents, and beautiful photographs, including ones of such renowned guests as William Burroughs, Henry Miller, Langston Hughes, Alberto Moravia, Zadie Smith, Jimmy Page, and Marilynne Robinson.

Tracing more than 100 years in the French capital, the book touches on the Lost Generation and the Beats, the Cold War, May ’68, and the feminist movement—all while reflecting on the timeless allure of bohemian life in Paris.

Krista Halverson is the director of Shakespeare and Company bookstore’s publishing venture. Previously, she was the managing editor of Zoetrope: All-Story, the art and literary quarterly published by Francis Ford Coppola, which has won several National Magazine Awards for Fiction and numerous design prizes. She was responsible for the magazine’s art direction, working with guest designers including Lou Reed, Kara Walker, Mikhail Baryshnikov, Zaha Hadid, Wim Wenders and Tom Waits, among others.

Krista Halverson is the director of Shakespeare and Company bookstore’s publishing venture. Previously, she was the managing editor of Zoetrope: All-Story, the art and literary quarterly published by Francis Ford Coppola, which has won several National Magazine Awards for Fiction and numerous design prizes. She was responsible for the magazine’s art direction, working with guest designers including Lou Reed, Kara Walker, Mikhail Baryshnikov, Zaha Hadid, Wim Wenders and Tom Waits, among others.

Jeanette Winterson‘s first novel, Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit, was published in 1985. In 1992 she was one of Granta’s Best of Young British Novelists. She has won numerous awards and is published around the world. Her memoir, Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal?, was an international bestseller. Her latest novel, The Gap of Time, is a “cover version” of Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale.

Sylvia Whitman is the owner of Shakespeare and Company bookstore, which her father opened in 1951. She took on management of the shop in 2004, when she was 23, and now co-manages the bookstore with her partner, David Delannet. Together they have opened an adjoining cafe, as well as launched a literary festival, a contest for unpublished novellas, and a publishing arm.

“I created this bookstore like a man would write a novel, building each room like a chapter, and I like people to open the door the way they open a book, a book that leads into a magic world in their imaginations.” —George Whitman, founder

Drawing on a century’s worth of never-before-seen archives, this first history of the bookstore features more than 300 images and 70 editorial contributions from shop visitors such as Allen Ginsberg, Anaïs Nin, Kate Tempest, and Ethan Hawke. With a foreword by Jeanette Winterson and an epilogue by Sylvia Whitman, the 400-page book is fully illustrated with color throughout.

Drawing on a century’s worth of never-before-seen archives, this first history of the bookstore features more than 300 images and 70 editorial contributions from shop visitors such as Allen Ginsberg, Anaïs Nin, Kate Tempest, and Ethan Hawke. With a foreword by Jeanette Winterson and an epilogue by Sylvia Whitman, the 400-page book is fully illustrated with color throughout.

Shakespeare and Company, Paris: A History of the Rag & Bone Shop of the Heart by Krista Halverson

Foreword by: Jeanette Winterson

Epilogue by: Sylvia Whitman

Contributions by:

Allen Ginsberg

Anaïs Nin

Lawrence Ferlinghetti

Sylvia Beach

Nathan Englander

Dervla Murphy

Ian Rankin

Kate Tempest

Ethan Hawke

David Rakoff

Publisher: Shakespeare and Company Paris

Publication date: August 2016

Hardback – ISBN: 979-1-09610-100-9

€ 35.00

Publication country:France

Pages:384

Weight: 1501.000g.

# More information on website Shakespeare & Company

Photos: Shakespeare & Comp, Jef van Kempen FDM

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, - Book News, - Book Stories, - Bookstores, Art & Literature News, BEAT GENERATION, Borges J.L., Burroughs, William S., Ernest Hemingway, Ginsberg, Allen, J.A. Woolf, James Baldwin, Kate/Kae Tempest, Samuel Beckett, Shakespeare, William, Tempest, Kate/Kae

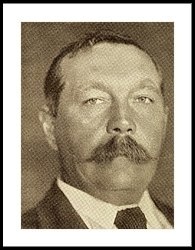

His First Operation

His First Operation

by Arthur Conan Doyle

It was the first day of the winter session, and the third year’s man was walking with the first year’s man. Twelve o’clock was just booming out from the Tron Church.

“Let me see,” said the third year’s man. “You have never seen an operation?”

“Never.”

“Then this way, please. This is Rutherford’s historic bar. A glass of sherry, please, for this gentleman. You are rather sensitive, are you not?”

“My nerves are not very strong, I am afraid.”

“Hum! Another glass of sherry for this gentleman. We are going to an operation now, you know.”

The novice squared his shoulders and made a gallant attempt to look unconcerned.

“Nothing very bad—eh?”

“Well, yes—pretty bad.”

“An—an amputation?”

“No; it’s a bigger affair than that.”

“I think—I think they must be expecting me at home.”

“There’s no sense in funking. If you don’t go to-day, you must to-morrow. Better get it over at once. Feel pretty fit?”

“Oh, yes; all right!” The smile was not a success.

“One more glass of sherry, then. Now come on or we shall be late. I want you to be well in front.”

“Surely that is not necessary.”

“Oh, it is far better! What a drove of students! There are plenty of new men among them. You can tell them easily enough, can’t you? If they were going down to be operated upon themselves, they could not look whiter.”

“I don’t think I should look as white.”

“Well, I was just the same myself. But the feeling soon wears off. You see a fellow with a face like plaster, and before the week is out he is eating his lunch in the dissecting rooms. I’ll tell you all about the case when we get to the theatre.”

The students were pouring down the sloping street which led to the infirmary—each with his little sheaf of note-books in his hand. There were pale, frightened lads, fresh from the high schools, and callous old chronics, whose generation had passed on and left them. They swept in an unbroken, tumultuous stream from the university gate to the hospital. The figures and gait of the men were young, but there was little youth in most of their faces. Some looked as if they ate too little—a few as if they drank too much. Tall and short, tweed-coated and black, round-shouldered, bespectacled, and slim, they crowded with clatter of feet and rattle of sticks through the hospital gate. Now and again they thickened into two lines, as the carriage of a surgeon of the staff rolled over the cobblestones between.

“There’s going to be a crowd at Archer’s,” whispered the senior man with suppressed excitement. “It is grand to see him at work. I’ve seen him jab all round the aorta until it made me jumpy to watch him. This way, and mind the whitewash.”

They passed under an archway and down a long, stone-flagged corridor, with drab-coloured doors on either side, each marked with a number. Some of them were ajar, and the novice glanced into them with tingling nerves. He was reassured to catch a glimpse of cheery fires, lines of white-counterpaned beds, and a profusion of coloured texts upon the wall. The corridor opened upon a small hall, with a fringe of poorly clad people seated all round upon benches. A young man, with a pair of scissors stuck like a flower in his buttonhole and a note-book in his hand, was passing from one to the other, whispering and writing.

“Anything good?” asked the third year’s man.

“You should have been here yesterday,” said the out-patient clerk, glancing up. “We had a regular field day. A popliteal aneurism, a Colles’ fracture, a spina bifida, a tropical abscess, and an elephantiasis. How’s that for a single haul?”

“I’m sorry I missed it. But they’ll come again, I suppose. What’s up with the old gentleman?”

A broken workman was sitting in the shadow, rocking himself slowly to and fro, and groaning. A woman beside him was trying to console him, patting his shoulder with a hand which was spotted over with curious little white blisters.

“It’s a fine carbuncle,” said the clerk, with the air of a connoisseur who describes his orchids to one who can appreciate them. “It’s on his back and the passage is draughty, so we must not look at it, must we, daddy? Pemphigus,” he added carelessly, pointing to the woman’s disfigured hands. “Would you care to stop and take out a metacarpal?”

“No, thank you. We are due at Archer’s. Come on!” and they rejoined the throng which was hurrying to the theatre of the famous surgeon.

The tiers of horseshoe benches rising from the floor to the ceiling were already packed, and the novice as he entered saw vague curving lines of faces in front of him, and heard the deep buzz of a hundred voices, and sounds of laughter from somewhere up above him. His companion spied an opening on the second bench, and they both squeezed into it.

“This is grand!” the senior man whispered. “You’ll have a rare view of it all.”

Only a single row of heads intervened between them and the operating table. It was of unpainted deal, plain, strong, and scrupulously clean. A sheet of brown water-proofing covered half of it, and beneath stood a large tin tray full of sawdust. On the further side, in front of the window, there was a board which was strewed with glittering instruments—forceps, tenacula, saws, canulas, and trocars. A line of knives, with long, thin, delicate blades, lay at one side. Two young men lounged in front of this, one threading needles, the other doing something to a brass coffee-pot-like thing which hissed out puffs of steam.

“That’s Peterson,” whispered the senior, “the big, bald man in the front row. He’s the skin-grafting man, you know. And that’s Anthony Browne, who took a larynx out successfully last winter. And there’s Murphy, the pathologist, and Stoddart, the eye-man. You’ll come to know them all soon.”

“Who are the two men at the table?”

“Nobody—dressers. One has charge of the instruments and the other of the puffing Billy. It’s Lister’s antiseptic spray, you know, and Archer’s one of the carbolic-acid men. Hayes is the leader of the cleanliness-and-cold-water school, and they all hate each other like poison.”

A flutter of interest passed through the closely packed benches as a woman in petticoat and bodice was led in by two nurses. A red woolen shawl was draped over her head and round her neck. The face which looked out from it was that of a woman in the prime of her years, but drawn with suffering, and of a peculiar beeswax tint. Her head drooped as she walked, and one of the nurses, with her arm round her waist, was whispering consolation in her ear. She gave a quick side-glance at the instrument table as she passed, but the nurses turned her away from it.

“What ails her?” asked the novice.

“Cancer of the parotid. It’s the devil of a case; extends right away back behind the carotids. There’s hardly a man but Archer would dare to follow it. Ah, here he is himself!”

As he spoke, a small, brisk, iron-grey man came striding into the room, rubbing his hands together as he walked. He had a clean-shaven face, of the naval officer type, with large, bright eyes, and a firm, straight mouth. Behind him came his big house-surgeon, with his gleaming pince-nez, and a trail of dressers, who grouped themselves into the corners of the room.

“Gentlemen,” cried the surgeon in a voice as hard and brisk as his manner, “we have here an interesting case of tumour of the parotid, originally cartilaginous but now assuming malignant characteristics, and therefore requiring excision. On to the table, nurse! Thank you! Chloroform, clerk! Thank you! You can take the shawl off, nurse.”

The woman lay back upon the water-proofed pillow, and her murderous tumour lay revealed. In itself it was a pretty thing—ivory white, with a mesh of blue veins, and curving gently from jaw to chest. But the lean, yellow face and the stringy throat were in horrible contrast with the plumpness and sleekness of this monstrous growth. The surgeon placed a hand on each side of it and pressed it slowly backwards and forwards.

“Adherent at one place, gentlemen,” he cried. “The growth involves the carotids and jugulars, and passes behind the ramus of the jaw, whither we must be prepared to follow it. It is impossible to say how deep our dissection may carry us. Carbolic tray. Thank you! Dressings of carbolic gauze, if you please! Push the chloroform, Mr. Johnson. Have the small saw ready in case it is necessary to remove the jaw.”

The patient was moaning gently under the towel which had been placed over her face. She tried to raise her arms and to draw up her knees, but two dressers restrained her. The heavy air was full of the penetrating smells of carbolic acid and of chloroform. A muffled cry came from under the towel, and then a snatch of a song, sung in a high, quavering, monotonous voice:

“He says, says he,

If you fly with me

You’ll be mistress of the ice-cream van.

You’ll be mistress of the——”

It mumbled off into a drone and stopped. The surgeon came across, still rubbing his hands, and spoke to an elderly man in front of the novice.

“Narrow squeak for the Government,” he said.

“Oh, ten is enough.”

“They won’t have ten long. They’d do better to resign before they are driven to it.”

“Oh, I should fight it out.”

“What’s the use. They can’t get past the committee even if they got a vote in the House. I was talking to——”

“Patient’s ready, sir,” said the dresser.

“Talking to McDonald—but I’ll tell you about it presently.” He walked back to the patient, who was breathing in long, heavy gasps. “I propose,” said he, passing his hand over the tumour in an almost caressing fashion, “to make a free incision over the posterior border, and to take another forward at right angles to the lower end of it. Might I trouble you for a medium knife, Mr. Johnson?”

The novice, with eyes which were dilating with horror, saw the surgeon pick up the long, gleaming knife, dip it into a tin basin, and balance it in his fingers as an artist might his brush. Then he saw him pinch up the skin above the tumour with his left hand. At the sight his nerves, which had already been tried once or twice that day, gave way utterly. His head swain round, and he felt that in another instant he might faint. He dared not look at the patient. He dug his thumbs into his ears lest some scream should come to haunt him, and he fixed his eyes rigidly upon the wooden ledge in front of him. One glance, one cry, would, he knew, break down the shred of self-possession which he still retained. He tried to think of cricket, of green fields and rippling water, of his sisters at home—of anything rather than of what was going on so near him.

And yet somehow, even with his ears stopped up, sounds seemed to penetrate to him and to carry their own tale. He heard, or thought that he heard, the long hissing of the carbolic engine. Then he was conscious of some movement among the dressers. Were there groans, too, breaking in upon him, and some other sound, some fluid sound, which was more dreadfully suggestive still? His mind would keep building up every step of the operation, and fancy made it more ghastly than fact could have been. His nerves tingled and quivered. Minute by minute the giddiness grew more marked, the numb, sickly feeling at his heart more distressing. And then suddenly, with a groan, his head pitching forward, and his brow cracking sharply upon the narrow wooden shelf in front of him, he lay in a dead faint.

When he came to himself, he was lying in the empty theatre, with his collar and shirt undone. The third year’s man was dabbing a wet sponge over his face, and a couple of grinning dressers were looking on.

“All right,” cried the novice, sitting up and rubbing his eyes. “I’m sorry to have made an ass of myself.”

“Well, so I should think,” said his companion.

“What on earth did you faint about?”

“I couldn’t help it. It was that operation.”

“What operation?”

“Why, that cancer.”

There was a pause, and then the three students burst out laughing. “Why, you juggins!” cried the senior man, “there never was an operation at all! They found the patient didn’t stand the chloroform well, and so the whole thing was off. Archer has been giving us one of his racy lectures, and you fainted just in the middle of his favourite story.”

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859 – 1930)

Round the Red Lamp: Being Facts and Fancies of Medical Life

His First Operation (#02)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Doyle, Arthur Conan, Doyle, Arthur Conan, DRUGS & DISEASE & MEDICINE & LITERATURE, Round the Red Lamp

Over the past seven years, NEU NOW has established an innovative international festival that features a curated selection of emerging artists entering international art arenas. For the eighth edition, NEU NOW returns to the spaces of the Westergasfabriek to present a multidisciplinary programme that aims to highlight cultural exchange and the fluid character of the artistic disciplines.

NEU NOW 2016 is a five-day celebration of arts in Amsterdam that welcomes 60 artists from 18 countries. From the 14th to the 18th of September, NEU NOW brings together a generation of rising artists from across Europe and beyond to share their works, practices and cultural perspectives in ways that encourage future collaborations.

NEU NOW exhibition

At the heart of the festival is the NEU NOW exhibition. Located in the Machinegebouw at the Westergasfabriek, NEU NOW exhibition houses 12 artworks from a broad range of disciplines including design, architecture, visual art and more. On Sunday the 18th of September, each exhibiting artist will present and explain their work in an interactive artist talk that explores their unique artistic practice and perspective. The exhibition is open every day and free of charge.

Artists on view at NEU NOW exhibition are:

Design/Architecture

Emilia Strzempek-Plasun (PL), Emma Dahlqvist (SE), Katalin Júlia Herter (HU), Stine Aas (NO)

Visual Arts

Alberto Condotta (UK), Alicja Symela (PL), Massimiliano Di Franca (BE), Jaeyong Choi (DE), Jonas Böttern and Emily Mennerdahl (SE), Lana Ruellan (FR), Lea Schiess (NL), Yi-Ting Tsai (TW), Viktorija Eksta (LV), Vladimir Novak (CR), Eva Giolo (BE)

NEU NOW performance

This year NEU NOW performance will take place in the Westergastheater and its surrounding area, with two or more exciting performances occurring daily. From theatre and dance, to music and sound, the performances offer a variety of themes and styles. After each performance visitors are invited to join the NEU NOW artist talks.

Performing artists are:

Theatre/Dance

Destiny’s Children (CH), Hsu Chen Wei Production Dance Company (TW), Nína Sigridur Hjalmarsdottir (IS), Theodore Livesey & Jacob Storer (BE), Zapia Company (SP)

Music/Sound

Jimmi Hueting (NL) , Teresa Doblinger (CH), Topos Kolektiv (CZ)

NEU NOW film

The 90 minute NEU NOW film programme at Ketelhuis will feature screenings of a variety of genres.

Film/Animation

Andrea Alessi (IT), HXZ (BE), Marek Jasan (SK), Sophie Dros (NL), Yaron Cohen (NL)

NEU NOW next

NEU NOW next

In addition to the core programme, NEU NOW invites visitors to delve deeper into their understanding of the presented artworks and artistic practices by getting involved in a variety of artist talks offered onsite at the Westergasfabriek. NEU NOW is also proud to present its very first speaker’s programme, during which a variety of influencers from the art world will talk about the ever-pressing issue of (Making a) Living in the Arts.

The speaker’s programme is free of charge and open to the public.

NEU NOW nacht

On the evening of Saturday the 17th of September, NEU NOW, in collaboration with Warsteiner, invites visitors to enjoy a festive late-night programme, with music, drinks, and much more. Music of the night will be provided by deadHYPE and Jimmie Hueting’s avant-garde pop band Jo Goes Hunting.

View the timetable for the exact dates and times.

NEU NOW 2016 will be held at Amsterdam’s Westergasfabriek from the 14th to the 18th of September 2016.

Locations Amsterdam NL

NEU NOW exhibition – Machinegebouw, Pazzanistraat 8

NEU NOW performance – Westergastheater, Pazzanistraat 15

NEU NOW film – Het Ketelhuis, Pazzanistraat 4

# More information on website NEU NOW 2016

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Art & Literature News, AUDIO, CINEMA, RADIO & TV, DANCE & PERFORMANCE, Design, Exhibition Archive, Fashion, Literary Events, MUSIC, Photography, THEATRE

Leigh Hunt

(1784 – 1859)

To John Keats

‘Tis well you think me truly one of those,

Whose sense discerns the loveliness of things;

For surely as I feel the bird that sings

Behind the leaves, or dawn as it up grows,

Or the rich bee rejoicing as he goes,

Or the glad issue of emerging springs,

Or overhead the glide of a dove’s wings,

Or turf, or trees, or, midst of all, repose.

And surely as I feel things lovelier still,

The human look, and the harmonious form

Containing woman, and the smile in ill,

And such a heart as Charles’s, wise and warm,–

As surely as all this, I see, ev’n now,

Young Keats, a flowering laurel on your brow.

Leigh Hunt poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Archive K-L, Hunt, Leigh, Keats, John

De Parelduiker 2016/3

De Parelduiker 2016/3

Nozzing but ze bloes. Het vergeten schrijversleven van Bert Jansen

Bert Jansen (1949-2002) is de auteur van Nozzing but ze bloes (1975), het gebundelde feuilleton van de jaren zestig, later herdrukt als En nog steeds vlekken in de lakens. Hij publiceerde een groot aantal boeken, maar nog veel meer niet. Zijn archief in het Letterkundig Museum getuigt van vele manuscripten die keer op keer werden geweigerd. Dit lot trof ook het boek dat zijn magnum opus had moeten worden, een biografie van de Drentse blueszanger en streekgenoot Harry Muskee. Voor De Parelduiker ontsluit Rutger Vahl het schrijversarchief van Bert Jansen.

Onbekende foto’s van Slauerhoff

Onlangs kreeg het Letterkundig Museum twee albums met foto’s van Slauerhoff in bezit. Ze zijn afkomstig van Lenie van der Goes, een vrouw die Slauerhoff in 1927 in Soerabaja ontmoette en met wie hij trouwplannen smeedde. Hoewel ze voorkomt in Wim Hazeus Slauerhoff-biografie, is er nog veel onbekend over deze vrouw, die ten faveure van de exotische dichter de brui gaf aan haar kersverse huwelijk met de arts Leendert Eerland. Wie was zij en wie maakte de andere foto’s in het album, waarop Slauerhoff in Macao te zien is?

En verder:

menno voskuil, Ben je in de winterboom. James Purdy en de Nederlandse private press

marco entrop, Tussen wilde zwanen en onsterfelijke nachtegalen.Op verjaarsvisite bij J.C. Bloem

bart slijper, Desperate charges. Tachtigers en sport

hans olink, Het geheim van Buchenwald

jan paul hinrichs, Schoon & haaks

paul arnoldussen, Wout Vuyk (1922-2016)

De Parelduiker is een uitgave van Uitgeverij Bas Lubberhuizen | Postbus 51140 | 1007 EC Amsterdam

# Meer op website De Parelduiker

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, - Book Stories, Art & Literature News, Bloem, J.C., LITERARY MAGAZINES, PRESS & PUBLISHING, Slauerhoff, Jan

Beat Generation

Beat Generation

Until 3 October 2016

The Centre Pompidou is to present Beat Generation, a novel retrospective dedicated to the literary and artistic movement born in the late 1940s that would exert an ever-growing influence for the next two decades. The theme will be reflected in all the Centre’s activities, with a rich programme of events devised in collaboration with the Bibliothèque Public d’Information and Ircam: readings, concerts, discussions, film screenings, a colloquium, a young people’s programme at Studio 13/16, etc.

Foreshadowing the youth culture and the cultural and sexual liberation of the 1960s, the emergence of the Beat Generation in the years following the Second World War, just as the Cold War was setting in, scandalised a puritan and Mc Carthyite America. Then seen as subversive rebels, the Beats appear today as the representatives of one of the most important cultural movements of the 20th century – a movement the Centre Pompidou’s survey will examine in all its breadth and geographical amplitude, from New York to Los Angeles, from Paris to Tangier.

The Centre Pompidou’s exhibition maps both the shifting geographical focus of the movement and its ever-shifting contours. For the artistic practices of the Beat Generation – readings, performances, concerts and films – testify to a breaking down of artistic boundaries and a desire for interdisciplinary collaboration that puts the singularity of the artist into question. Alongside notable visual artists, mostly representative of the California scene (Wallace Berman, Bruce Conner, George Herms, Jay DeFeo, Jess…), an important place is given to the literary dimension of the movement, to spoken poetry in its relationship to jazz, and more particularly to the Black American poetry (LeRoi Jones, Bob Kaufman…) that remains largely unknown in Europe, like the magazines in which it circulated (Beatitude, Umbra…). Photography was also an important medium, represented here by the productions of Allen Ginsberg and William Burroughs – mostly portraits – and a substantial body of photographs by Robert Frank (Les Américains, From the Bus…), Fred McDarrah, and John Cohen, all taken during the shooting of Pull my Daisy, as well as work by Harold Chapman, who chronicled the life of the Beat Hotel in Paris between 1958 and 1963. The same was true of the films (Christopher MacLaine, Bruce Baillie, Stan Brakhage, Ron Rice…) that would both reflect and document the history and development of the movement.

Exhibition at the Centre Pompidou in Paris until October 3, 2016

New publication:

New publication:

Beat generation – exhibition album

Movement of literary and artistic inspiration born in the United States in the 1950s, at the initiative of William Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac, the Beat Generation has profoundly influenced contemporary creation.

The book displays the different artworks exhibited along with short explanatory essays. A clear and precise album suitable for a large audience.

Bilingual version French / English.

Binding: Softbound

Language: Bilingual French / English

EAN 9782844267467

Number of pages 60

Number of illustrations 60

Publication date 15/06/2016

Dimensions 27 x 27 cm

Author: Philippe-Alain Michaud

Publisher: Centre Pompidou

€9.50

# Information and schedule about the Beat Generation exhibition on website Centre Pompidou

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #Beat Generation Archives, - Book News, Burroughs, William S., DICTIONARY OF IDEAS, DRUGS & DISEASE & MEDICINE & LITERATURE, Ginsberg, Allen, Kerouac, Jack, Literaire sporen, LITERARY MAGAZINES

De Boekenparade is hét grootste boekenevenement van 2016 Jaar van het Boek: van 2 t/m 25 september 2016 staan boeken en verhalen centraal. De focus van het festival ligt op beleving en ontmoeting. De Boekenparade belicht op prikkelende wijze het fenomeen boek in al zijn verrassende vormen en biedt een uitgebreid cross-over programma van evenementen, performances, podiumkunsten, muziek, workshops en een expositie.

De Boekenparade is hét grootste boekenevenement van 2016 Jaar van het Boek: van 2 t/m 25 september 2016 staan boeken en verhalen centraal. De focus van het festival ligt op beleving en ontmoeting. De Boekenparade belicht op prikkelende wijze het fenomeen boek in al zijn verrassende vormen en biedt een uitgebreid cross-over programma van evenementen, performances, podiumkunsten, muziek, workshops en een expositie.

Ook Manuscripta, traditioneel de opening van het boekenseizoen, is dit jaar onderdeel van de Boekenparade en vindt plaats op zaterdag 3 september in de Tolhuistuin.

Pepijn Lanen, Herman Koch en Herman Brusselmans verzorgen de openingsact van de Boekenparade. Verder geven onder meer acte de présence: Griet Op de Beeck, Abdelkader Benali, Michael Berg, Marion Bloem, Joris van Casteren, Renate Dorrestein, Michel van Egmond, Sophie Hannah, Astrid Harrewijn, Patrick van Hees, Arno Kantelberg, Geert Mak, Isa Maron, Tosca Menten, Nelleke Noordervliet, Christine Otten, Hagar Peeters, Dokter Pol, Ntjam Rosie, Mirjam Rotenstreich, Geronimo Stilton en Harmen van Straaten.

In de weekenden vinden aan de IJpromenade tegenover Amsterdam CS grote evenementen plaats en ook doordeweeks zijn er programma’s. De eerste programma’s (het concert met Pepijn Lanen en High Tea & Books) zijn bekend. Op 9 augustus volgt de precieze line-up van de overige events. In de kalender hieronder wordt een tipje van de sluier opgelicht.

Het hart van de Boekenparade is de – culturele en kunstzinnige broed- en ontmoetingsplaats – Tolhuistuin. Daarnaast is er ook programmering in filmmuseum EYE.

De Boekenparade is, mede door de diverse programmering en de doorlopende exposities, aantrekkelijk voor jong en oud, uit de stad of op bezoek, van laaggeletterd tot boekenwurm: de Boekenparade is voor iedereen. Een dagje Boekenparade is een ervaring, beginnend bij aankomst op het Centraal Station, gevolgd door de pont ofwel de heenenweer, wandelend langs de verschillende locaties en podia waar meegedaan, gegeten, bekeken en geluisterd kan worden. Met één rode draad: het verhaal en het boek als uitgangspunt voor deze ‘reis’.

De Boekenparade is, mede door de diverse programmering en de doorlopende exposities, aantrekkelijk voor jong en oud, uit de stad of op bezoek, van laaggeletterd tot boekenwurm: de Boekenparade is voor iedereen. Een dagje Boekenparade is een ervaring, beginnend bij aankomst op het Centraal Station, gevolgd door de pont ofwel de heenenweer, wandelend langs de verschillende locaties en podia waar meegedaan, gegeten, bekeken en geluisterd kan worden. Met één rode draad: het verhaal en het boek als uitgangspunt voor deze ‘reis’.

02 sept: OFFICIËLE OPENING

02 sept: NAAMLOOS – DE FAVORIETE AVOND VAN PEPIJN LANEN

03 sept: MANUSCRIPTA

04 sept: DIES IST WAS WIR TEILEN

05 sept: START VAN DE WEEK VAN DE ALFABETISERING

09 sept: MEDIABORREL NOORD en DE BETERE BOEKENSHOW

10 sept: HIGH TEA & BOOKS

11 sept: REAL MEN READ & Listen

12 sept: THRILLERS: 100 JAAR HERCULE POIROT

14 sept: CPI KONINKLIJKE WÖHRMANN

15 sept: BOEKHANDEL ATHENAEUM 50 JAAR

15 sept: MORGENLANDFESTIVAL

16 sept: YALBAL

17 sept: YA-WEEKENDER: SATURDAY

17 sept: BOEKVERFILMINGEN

18 sept: Kinderboekenparade aan ’t IJ

20 sept: FRAMER FRAMED

21 sept: MÖHLEMANNS en KÖHLEMANNS

22 sept: KICK-OFF RENEW THE BOOK

23 sept: MIJN WOORDEN ZIJN MUZIEK en AC/DJ

24 sept: SPANNENDE WANDELING EN DOKTER POL

25 sept: KOOKBOEKENFESTIVAL

25 sept: Lancering van lees.magazine.bol

25 sept: NIGHTWATCH MET DIMITRI VERHULST

# Meer info op website Boekenparade 2016

De Tolhuistuin, adres Tolhuistuin: IJpromenade 2, Amsterdam

De Tolhuistuin, adres Tolhuistuin: IJpromenade 2, Amsterdam

De Tolhuistuin ligt recht tegenover het Centraal Station van Amsterdam. Bij de uitgang aan de Noordzijde neem je de gratis pont ‘Buiksloterwegveer’ om het IJ over te steken.

Pont: Vanaf Amsterdam CS gaat iedere 5 minuten een gratis pont naar de overkant van het IJ (Buiksloterweg, reisduur 3 minuten). De pont vaart dag en nacht, 24 uur per dag.

Bus: Vanuit Amsterdam-Noord is de Tolhuistuin te bereiken met bus 38. De bus stopt direct naast de Tolhuistuin. Op zaterdag rijdt bus 38 om de 12 minuten. Op zondag rijdt bus 38 om het half uur.

Stichting Tolhuistuin

Tolhuisweg 5 – 1031 CL Amsterdam

www.stichtingtolhuistuin.nl

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, - Book News, Art & Literature News, Herman Brusselmans, Literary Events, Peeters, Hagar, Renate Dorrestein

David Claerbout

David Claerbout

FUTURE

3 sept 2016 – 29 jan 2017

Zeven jaar geleden exposeerde David Claerbout (Kortrijk, 1969) voor het eerst in De Pont. De tentoonstelling The Shape of Time met een tiental video-installaties liet een onuitwisbare indruk achter. Een magische schemerwereld van oude zwart witfoto’s die op een subtiele manier tot leven worden gewekt en vertraagde filmopnames van een vrouw die koffie inschenkt op het terras van een achttiende-eeuws Frans landhuis en vervolgens bij de ondergaande zon zwaaiend afscheid neemt van de toeschouwer. Het zichtbaar verstrijken van de tijd riep een gevoel van verwondering en vervreemding op. De nieuwe tentoonstelling van Claerbout, de eerste in de nieuwbouw van het museum, is getiteld FUTURE.

FUTURE lijkt bij de feestelijke gelegenheid een toepasselijke titel, maar blijkt bij nader inzien nogal dubbelzinnig. Een van de meest recente videowerken op de tentoonstelling, Olympia (The real time disintegration into ruins of the Berlin Olympic stadium over the course of a thousand years), brengt het verval in beeld van het historisch beladen gebouw waar in 1936 de Olympische Spelen werden gehouden. Het werk verwijst naar een duistere periode, toen Hitler aan de macht was en hij samen met zijn huisarchitect Albert Speer megalomane bouwprojecten ontwikkelde. Bij hun plannen hielden beide heren al rekening met de ‘ruïnewaarde’ van een gebouw over duizend jaar. De overblijfselen van het Derde Rijk moesten dan minstens zo imposant zijn als het Colosseum in Rome nu.

Sinds de laatste tentoonstelling in De Pont heeft Claerbout zijn werkwijze radicaal veranderd. Hij volgde een opleiding 3D animatie en werkt niet langer met acteurs en filmopnames. Alles gebeurt nu in zijn studio waar hij samen met negen medewerkers elk beeld stap voor stap digitaal opbouwt. Zo creëren zij een niet-reëel bestaande werkelijkheid. Een virtuele wereld waarin elk detail moet kloppen anders verliezen de videobeelden direct hun geloofwaardigheid. Bij het maken van een foto liggen keuzes over details zoals plek, seizoen en tijdstip van de dag automatisch vast – bij een digitaal beeld moet de kunstenaar zelf steeds voor ‘god’ spelen.

De bezoeker van de tentoonstelling zal van deze technische vernieuwingen echter nauwelijks iets merken. De hand van de meester blijkt vrijwel onveranderd. Je herkent dezelfde fenomenen als licht, schaduw en wind die het oppervlak van water, bomen en architectuur zachtjes, zonder geluid, in beweging brengen. De transformaties voltrekken zich in slow motion: ‘Ik beeldhouw met duur,’ zegt Claerbout. Duur is volgens hem iets anders dan tijd: ‘duur is geen onafhankelijk verschijnsel zoals tijd, maar bevindt zich altijd ergens tussenin.’

Voor het eerst in Europa toont Claerbout zijn video-installaties in combinatie met de tekeningen die het maanden- of soms zelfs jarenlange proces van de totstandkoming van de videofilms begeleiden en ondersteunen. De Pont bezit naast videowerken ook een mooie serie tekeningen van hem. Hij is een begenadigd tekenaar die zijn gedachten snel op papier kan zetten. Zo houdt hij greep op het ingewikkelde ontstaansproces waarbij talloze medewerkers betrokken zijn. Deze functie van het tekenen verschilt in wezen niet van de schets of voorstudie die een traditionele schilder gebruikt om zijn ideeën vast te leggen. Voor 3D-animatie moet je naast moderne computertechnologie ook traditionele vakken als tekenen, schilderen, beeldhouwen en cinematografie beheersen. Met als resultaat, tot Claerbouts eigen verbazing, een ‘conservatief’ schilderkunstig realisme. Maar de tekeningen vormen voor hem ook een soort uitlaatklep gezien de uitvoerige en soms heftige teksten die hij soms in de marge schrijft. De recent verschenen tekeningencatalogus ontlokte Claerbout de opmerking dat het wel eens tijd werd om zijn recepten en keukengeheimen prijs te geven.

David Claerbout

FUTURE

3 sept 2016 – 29 jan 2017

Op 3 september tevens opening nieuwe vleugel Museum De Pont

Museum De Pont

Wilhelminapark 1

5041 EA Tilburg

# Meer info op website Museum De Pont

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: AUDIO, CINEMA, RADIO & TV, Exhibition Archive, Photography

Hiroo Onoda zit 29

jaar zonder nieuws

Thuis groeide een compleet nieuw

geslacht op terwijl hij door gebladerte

spiedde, voortdurend op zijn hoede:

maar niemand duurde almaar langer.

Pal in zijn oerwoud, van alles afgesneden.

Het zwaard nooit wijkend van de zij,

geweren tot vervelens toe gesmeerd.

Hij had geleerd hoe stand te houden.

Dagelijks menu banaan, gedroogd soms,

en vogels uit de lucht. De slapen licht

en bol van zege. Meer dan tienduizend

dagen en nachten de vijand in het hoofd.

Zelfs een havik is tussen kraaien een arend,

o zoon van de bloedrode zon.

Bert Bevers

Uit: Onaangepaste tijden, Zinderend, Bergen op Zoom, 2006

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Bevers, Bert

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature