Fleurs du Mal Magazine

TILT Festival

29 maart – 1 april 2017

Tilburg

de eerste namen:

Yves Petry,

Astrid Roemer,

De Optimist

tiltfestival.nu

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Art & Literature News, AUDIO, CINEMA, RADIO & TV, DANCE & PERFORMANCE, MUSIC, THEATRE, Tilt Festival Tilburg

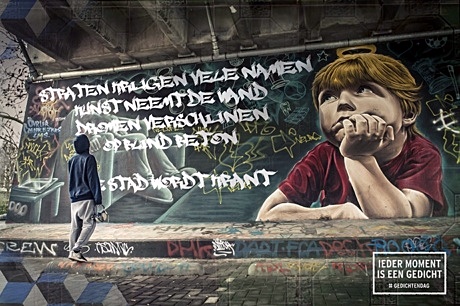

Gedichtendag 2017 (26 januari)

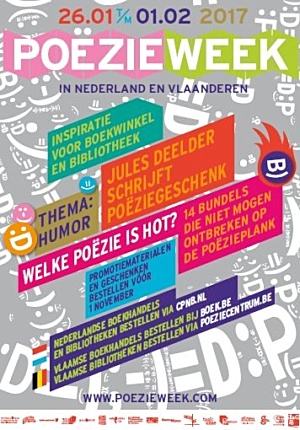

Poëzieweek 2017 (26 januari t/m/ 1 februari)

Opening Poëzieweek 2017 (26 januari t/m/ 1 februari)

Opening Poëzieweek 2017 (26 januari t/m/ 1 februari)

Met Gedichtendag gaat op de laatste donderdag van januari traditiegetrouw de Poëzieweek van start. Gedichtendag, sinds 2000 georganiseerd door Poetry International Rotterdam, is hét poëziefeest van Nederland en Vlaanderen. Poëzieliefhebbers in Nederland en Vlaanderen organiseren die dag een grote diversiteit aan eigen poëzieactiviteiten en ook de media klinken die dag een stuk poëtischer.

Voor de enorme hoeveelheid optredens, publicaties, poëzieprijzen, -programma’s en -activiteiten is één dag simpelweg veel te kort!

Verspreid poëzie op social media

Breng poëzie in uw leven! Laat u inspireren door de foto-gedichten en deel het op social media met #Gedichtendag. Wijs vrienden en contacten op website poezieweek.com

Lees ook poëzie op website: fleursdumal.nl magazine

Dicht mee!

More in: #Archive A-Z Sound Poetry, Art & Literature News, CLASSIC POETRY, CONCRETE , VISUAL & SOUND POETRY, EDITOR'S CHOICE, EXPERIMENTAL POETRY, LIGHT VERSE, Literary Events, MODERN POETRY, POETRY ARCHIVE, Poëzieweek, PRESS & PUBLISHING, STREET POETRY, The talk of the town

Humor en poëzie? ”Jawel”, zegt Jules Deelder (Rotterdam-Overschie, 1944), die het Poëziegeschenk 2017 zal schrijven. Met het thema humor in de Poëzieweek 2017 komt er aandacht voor gedichten die op de lachspieren werken, uit hilariteit, herkenbaarheid of uit ironie. Humor is in Deelders poëzie in ieder geval geen curiosum. Deze Nederlandse dichter van een omvangrijk oeuvre staat in binnen- en buitenland bekend om zijn memorabele performances, waarbij de Beat Generation nooit veraf lijkt.

Aan de vooravond van de Poëzieweek wordt in Nederland voor de 23ste keer de VSB Poëzieprijs uitgereikt en in Vlaanderen de Herman de Coninckprijs. De Poëzieweek start op donderdag 26 januari in Vlaanderen en Nederland met Gedichtendag en loopt t/m woensdag 1 februari; de prijsuitreiking van de Turing Gedichtenwedstrijd. Tijdens de Poëzieweek krijgen de klanten van de boekhandel bij aankoop van € 12,50 aan poëzie het Poëziegeschenk cadeau.

Gedichten worden in onze contreien eerder met ernst dan met humor geassocieerd. Het verdriet is eindeloos en de liefde hopeloos. Toch wordt er ook heel wat afgelachen in poëtenland. Soms is er de luide bulderlach bij een kolderiek nonsensgedicht, vaak is er ook een grijns van herkenning. De verwarrende situatie die de dichter beschrijft, hebben we zelf allemaal ook meegemaakt. Humor in poëzie kan ook wat ongemakkelijk zijn: valt hier wel om te lachen? Dichters gebruiken humor ook in de vorm van ironie of spot om een maatschappelijke wantoestand aan te klagen. Humor is bovenal een manier om met de meerduidigheid van de dingen om te gaan en dat is bij poëzie niet anders…

Gedichten worden in onze contreien eerder met ernst dan met humor geassocieerd. Het verdriet is eindeloos en de liefde hopeloos. Toch wordt er ook heel wat afgelachen in poëtenland. Soms is er de luide bulderlach bij een kolderiek nonsensgedicht, vaak is er ook een grijns van herkenning. De verwarrende situatie die de dichter beschrijft, hebben we zelf allemaal ook meegemaakt. Humor in poëzie kan ook wat ongemakkelijk zijn: valt hier wel om te lachen? Dichters gebruiken humor ook in de vorm van ironie of spot om een maatschappelijke wantoestand aan te klagen. Humor is bovenal een manier om met de meerduidigheid van de dingen om te gaan en dat is bij poëzie niet anders…

J.A. Deelder zette zijn eerste stappen in zijn carrière als performer in 1966. Na zijn poëziedebuut Gloria Satoria bij De Bezige Bij volgden nog vele bundels met als meest recente publicaties Tussentijds (2008), Ruisch (2011), Het graf van Descartes (2013) en Dag en nacht (2014). In zijn vaak absurdistische, maar steeds glasheldere poëzie wordt de jazz haast tastbaar. De onderwerpen die Deelder aansnijdt zijn de Tweede Wereldoorlog, Duitsland, Rotterdam, jazz en het leven van Deelder zelf. In 1982 debuteerde Deelder als prozaïst met Schöne Welt. Hierna verschenen een groot aantal verhalenbundels en gelegenheidsuitgaven waaronder Deelderama (2001), Swingkoning (2006) en Deelder lacht (2007). Deelder ontving voor zijn gehele oeuvre de Anna Blaman Prijs (1988), de Johnny Van Doorn-prijs voor de gesproken letteren (1999), en de Tollensprijs (2005). In 2005 mocht hij ook een Edison voor zijn cd Deelder blijft draaien in ontvangst nemen.

De Poëzieweek is een Nederlands-Vlaamse samenwerking van Stichting Poetry International, Poëziecentrum, Iedereen Leest Vlaanderen, Stichting Lezen Nederland, Awater, Poëzieclub, Het Literatuurhuis, Wintertuin, SLAG, Taalunie, SSS, het Nederlands Letterenfonds, Vlaams Fonds voor de Letteren, Turing Foundation, VSBfonds, Boek.be en de CPNB. Met de bundeling van deze activiteiten willen de organisatoren een groter bereik creëren voor poëzie.

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Art & Literature News, Jules Deelder, LIGHT VERSE, Literary Events, Poëzieweek

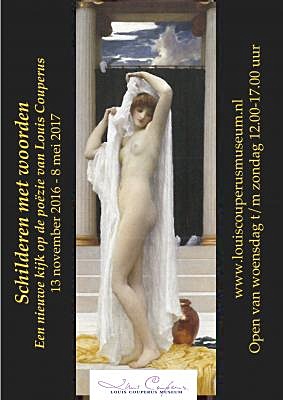

Nieuwe tentoonstelling Schilderen met woorden. Een nieuwe kijk op de poëzie van Louis Couperus. 13 november 2016 – 8 mei 2017 in het Louis Couperus Museum.

Nieuwe tentoonstelling Schilderen met woorden. Een nieuwe kijk op de poëzie van Louis Couperus. 13 november 2016 – 8 mei 2017 in het Louis Couperus Museum.

Gedurende een groot deel van zijn leven (om precies te zijn 25 jaar) heeft Louis Couperus poëzie geschreven. Tot nu toe is er te weinig aandacht geschonken aan dit onderwerp.

Deze winter visualiseert het Louis Couperus Museum de dichtkunst van de Haagse schrijver door middel van afbeeldingen en beeldhouwwerk waardoor de schrijver was geïnspireerd.

Tentoonstelling

Aan de wanden worden representatieve gedichten of citaten daaruit groot weer gegeven, op textiel afgedrukt. Bij elk fragment komt een afbeelding te hangen die inhoudelijk in verband staat met het betreffende gedicht. Reproducties van schilderijen – in een enkel geval zelfs een beeldhouwwerk – hebben Couperus soms regelrecht tot voorbeeld gediend. Ook de doorwerking van zijn poëzie in zijn proza komt aan bod. Op de televisiemonitor is een voordracht van zijn dichtkunst door acteur Joop Keesmaat te zien en te horen.

De expositie is gecentreerd rond 5 thema’s uit Couperus’ poëzie. Allereerst de figuur van Petrarca die hem de Laura-cyclus in gaf. Ten tweede de salon-schilderkunst uit de negentiende eeuw en daarmee samenhangend gedichten waarin Couperus bijna letterlijk ‘met woorden schildert’. Vervolgens het beeld Alba van de Friese beeldhouwer Pier Pander, dat Couperus in het gelijknamige sonnet bezong. Dan de wereld van de Arthurlegenden die hem zo boeide, en de door Italië geïnspireerde gedichten. De ‘aardse Couperus’ (Arjan Peters) komt in de ‘sonnettenroman’ Endymion aan bod. Hierin vereenzelvigt Couperus zich met een volksjongen die in de klassieke metropool Alexandrië allerlei avonturen beleeft. Dit wordt op eigentijdse wijze gevisualiseerd door een stripverhaal van de hand van Mees Arnzt, een student van de Koninklijke Academie voor Beeldende Kunsten.

Verantwoording

De tentoonstelling wordt ingericht door gastconservator Frans van der Linden, medewerker van het Louis Couperus Museum, winnaar van de Couperuspenning en samensteller van het boekje O gouden, stralenshelle fantazie! Bloemlezing uit de poëzie van Louis Couperus (in de Prominentreeks van Uitgeverij Tiem, 2015).

De expositie wordt mede mogelijk gemaakt dankzij een bijdrage van het Prins Bernhard Cultuurfonds.

schilderen met woorden.

een nieuwe kijk op de poëzie van Couperus

13 november 2016 – 8 mei 2017

Louis Couperus Museum

Javastraat 17

2585 AB Den Haag

070-3640653

info@louiscouperusmuseum.nl

Openingstijden

Woensdag t/m zondag 12.00-17.00 uur

Voor groepen ook op afspraak

Het gehele jaar door geopend, met uitzondering van 1ste en 2de Kerstdag en Nieuwjaarsdag

Toegankelijk voor gehandicapten

# Meer informatie op website van het Couperus Museum

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Archive C-D, Art & Literature News, DICTIONARY OF IDEAS, Literary Events, Louis Couperus, Museum of Literary Treasures

The Ambitious Guest

The Ambitious Guest

by Nathaniel Hawthorne

One September night a family had gathered round their hearth, and piled it high with the driftwood of mountain streams, the dry cones of the pine, and the splintered ruins of great trees that had come crashing down the precipice. Up the chimney roared the fire, and brightened the room with its broad blaze. The faces of the father and mother had a sober gladness; the children laughed; the eldest daughter was the image of Happiness at seventeen; and the aged grandmother, who sat knitting in the warmest place, was the image of Happiness grown old. They had found the “herb, heart’s-ease,” in the bleakest spot of all New England. This family were situated in the Notch of the White Hills, where the wind was sharp throughout the year, and pitilessly cold in the winter–giving their cottage all its fresh inclemency before it descended on the valley of the Saco. They dwelt in a cold spot and a dangerous one; for a mountain towered above their heads, so steep, that the stones would often rumble down its sides and startle them at midnight.

The daughter had just uttered some simple jest that filled them all with mirth, when the wind came through the Notch and seemed to pause before their cottage–rattling the door, with a sound of wailing and lamentation, before it passed into the valley. For a moment it saddened them, though there was nothing unusual in the tones. But the family were glad again when they perceived that the latch was lifted by some traveller, whose footsteps had been unheard amid the dreary blast which heralded his approach, and wailed as he was entering, and went moaning away from the door.

Though they dwelt in such a solitude, these people held daily converse with the world. The romantic pass of the Notch is a great artery, through which the life-blood of internal commerce is continually throbbing between Maine, on one side, and the Green Mountains and the shores of the St. Lawrence, on the other. The stage-coach always drew up before the door of the cottage. The way-farer, with no companion but his staff, paused here to exchange a word, that the sense of loneliness might not utterly overcome him ere he could pass through the cleft of the mountain, or reach the first house in the valley. And here the teamster, on his way to Portland market, would put up for the night; and, if a bachelor, might sit an hour beyond the usual bedtime, and steal a kiss from the mountain maid at parting. It was one of those primitive taverns where the traveller pays only for food and lodging, but meets with a homely kindness beyond all price. When the footsteps were heard, therefore, between the outer door and the inner one, the whole family rose up, grandmother, children, and all, as if about to welcome someone who belonged to them, and whose fate was linked with theirs.

The door was opened by a young man. His face at first wore the melancholy expression, almost despondency, of one who travels a wild and bleak road, at nightfall and alone, but soon brightened up when he saw the kindly warmth of his reception. He felt his heart spring forward to meet them all, from the old woman, who wiped a chair with her apron, to the little child that held out its arms to him. One glance and smile placed the stranger on a footing of innocent familiarity with the eldest daughter.

“Ah, this fire is the right thing!” cried he; “especially when there is such a pleasant circle round it. I am quite benumbed; for the Notch is just like the pipe of a great pair of bellows; it has blown a terrible blast in my face all the way from Bartlett.”

“Then you are going towards Vermont?” said the master of the house, as he helped to take a light knapsack off the young man’s shoulders.

“Yes; to Burlington, and far enough beyond,” replied he. “I meant to have been at Ethan Crawford’s tonight; but a pedestrian lingers along such a road as this. It is no matter; for, when I saw this good fire, and all your cheerful faces, I felt as if you had kindled it on purpose for me, and were waiting my arrival. So I shall sit down among you, and make myself at home.”

The frank-hearted stranger had just drawn his chair to the fire when something like a heavy footstep was heard without, rushing down the steep side of the mountain, as with long and rapid strides, and taking such a leap in passing the cottage as to strike the opposite precipice. The family held their breath, because they knew the sound, and their guest held his by instinct.

“The old mountain has thrown a stone at us, for fear we should forget him,” said the landlord, recovering himself. “He sometimes nods his head and threatens to come down; but we are old neighbors, and agree together pretty well upon the whole. Besides we have a sure place of refuge hard by if he should be coming in good earnest.”

Let us now suppose the stranger to have finished his supper of bear’s meat; and, by his natural felicity of manner, to have placed himself on a footing of kindness with the whole family, so that they talked as freely together as if he belonged to their mountain brood. He was of a proud, yet gentle spirit–haughty and reserved among the rich and great; but ever ready to stoop his head to the lowly cottage door, and be like a brother or a son at the poor man’s fireside. In the household of the Notch he found warmth and simplicity of feeling, the pervading intelligence of New England, and a poetry of native growth, which they had gathered when they little thought of it from the mountain peaks and chasms, and at the very threshold of their romantic and dangerous abode. He had travelled far and alone; his whole life, indeed, had been a solitary path; for, with the lofty caution of his nature, he had kept himself apart from those who might otherwise have been his companions. The family, too, though so kind and hospitable, had that consciousness of unity among themselves, and separation from the world at large, which, in every domestic circle, should still keep a holy place where no stranger may intrude. But this evening a prophetic sympathy impelled the refined and educated youth to pour out his heart before the simple mountaineers, and constrained them to answer him with the same free confidence. And thus it should have been. Is not the kindred of a common fate a closer tie than that of birth?

The secret of the young man’s character was a high and abstracted ambition. He could have borne to live an undistinguished life, but not to be forgotten in the grave. Yearning desire had been transformed to hope; and hope, long cherished, had become like certainty, that, obscurely as he journeyed now, a glory was to beam on all his pathway-though not, perhaps, while he was treading it. But when posterity should gaze back into the gloom of what was now the present, they would trace the brightness of his footsteps, brightening as meaner glories faded, and confess that a gifted one had passed from his cradle to his tomb with none to recognize him.

“As yet,” cried the stranger–his cheek glowing and his eye flashing with enthusiasm–“as yet, I have done nothing. Were I to vanish from the earth tomorrow, none would know so much of me as you: that a nameless youth came up at nightfall from the valley of the Saco, and opened his heart to you in the evening, and passed through the Notch by sunrise, and was seen no more. Not a soul would ask, ‘Who was he? Whither did the wanderer go?’ But I cannot die till I have achieved my destiny. Then, let Death come! I shall have built my monument!”

There was a continual flow of natural emotion, gushing forth amid abstracted reverie, which enabled the family to understand this young man’s sentiments, though so foreign from their own. With quick sensibility of the ludicrous, he blushed at the ardor into which he had been betrayed

“You laugh at me,” said he, taking the eldest daughter’s hand, and laughing himself. “You think my ambition as nonsensical as if I were to freeze myself to death on the top of Mount Washington, only that people might spy at me from the country round about. And, truly, that would be a noble pedestal for a man’s statue!”

“It is better to sit here by this fire,” answered the girl, blushing, “and be comfortable and contented, though nobody thinks about us.”

“I suppose,” said her father, after a fit of musing, “there is something natural in what the young man says; and if my mind had been turned that way, I might have felt just the same. It is strange, wife, how his talk has set my head running on things that are pretty certain never to come to pass.”

“Perhaps they may,” observed the wife. “Is the man thinking what he will do when he is a widower?”

“No, no!” cried he, repelling the idea with reproachful kindness. “When I think of your death, Esther, I think of mine, too. But I was wishing we had a good farm in Bartlett, or Bethlehem, or Littleton, or some other township round the White Mountains; but not where they could tumble on our heads. I should want to stand well with my neighbors and be called Squire, and sent to General Court for a term or two; for a plain, honest man may do as much good there as a lawyer. And when I should be grown quite an old man, and you an old woman, so as not to be long apart, I might die happy enough in my bed, and leave you all crying around me. A slate gravestone would suit me as well as a marble one–with just my name and age, and a verse of a hymn, and something to let people know that I lived an honest man and died a Christian.”

“There now!” exclaimed the stranger; “it is our nature to desire a monument, be it slate or marble, or a pillar of granite, or a glorious memory in the universal heart of man.”

“We’re in a strange way, tonight,” said the wife, with tears in her eyes. “They say it’s a sign of something, when folks’ minds go a-wandering so. Hark to the children!”

They listened accordingly. The younger children had been put to bed in another room, but with an open door between, so that they could be heard talking busily among themselves. One and all seemed to have caught the infection from the fireside circle, and were outvying each other in wild wishes, and childish projects, of what they would do when they came to be men and women. At length a little boy, instead of addressing his brothers and sisters, called out to his mother.

“I’ll tell you what I wish, mother,” cried he. “I want you and father and grandma’m, and all of us, and the stranger too, to start right away, and go and take a drink out of the basin of the Flume!”

Nobody could help laughing at the child’s notion of leaving a warm bed, and dragging them from a cheerful fire, to visit the basin of the Flume–a brook, which tumbles over the precipice, deep within the Notch. The boy had hardly spoken when a wagon rattled along the road, and stopped a moment before the door. It appeared to contain two or three men, who were cheering their hearts with the rough chorus of a song, which resounded, in broken notes, between the cliffs, while the singers hesitated whether to continue their journey or put up here for the night.

“Father,” said the girl, “they are calling you by name.”

But the good man doubted whether they had really called him, and was unwilling to show himself too solicitous of gain by inviting people to patronize his house. He therefore did not hurry to the door; and the lash being soon applied, the travellers plunged into the Notch, still singing and laughing, though their music and mirth came back drearily from the heart of the mountain.

“There, mother!” cried the boy, again. “They’d have given us a ride to the Flume.”

Again they laughed at the child’s pertinacious fancy for a night ramble. But it happened that a light cloud passed over the daughter’s spirit; she looked gravely into the fire, and drew a breath that was almost a sigh. It forced its way, in spite of a little struggle to repress it. Then starting and blushing, she looked quickly round the circle, as if they had caught a glimpse into her bosom. The stranger asked what she had been thinking of.

“Nothing,” answered she, with a downcast smile. “Only I felt lonesome just then.”

“Oh, I have always had a gift of feeling what is in other people’s hearts,” said he, half seriously. “Shall I tell the secrets of yours? For I know what to think when a young girl shivers by a warm hearth, and complains of lonesomeness at her mother’s side. Shall I put these feelings into words?”

“They would not be a girl’s feelings any longer if they could be put into words,” replied the mountain nymph, laughing, but avoiding his eye.

All this was said apart. Perhaps a germ of love was springing in their hearts, so pure that it might blossom in Paradise, since it could not be matured on earth; for women worship such gentle dignity as his; and the proud, contemplative, yet kindly soul is oftenest captivated by simplicity like hers. But while they spoke softly, and he was watching the happy sadness, the lightsome shadows, the shy yearnings of a maiden’s nature, the wind through the Notch took a deeper and drearier sound. It seemed, as the fanciful stranger said, like the choral strain of the spirits of the blast, who in old Indian times had their dwelling among these mountains, and made their heights and recesses a sacred region.

There was a wail along the road, as if a funeral were passing. To chase away the gloom, the family threw pine branches on their fire, till the dry leaves crackled and the flame arose, discovering once again a scene of peace and humble happiness. The light hovered about them fondly, and caressed them all. There were the little faces of the children, peeping from their bed apart, and here the father’s frame of strength, the mother’s subdued and careful mien, the high-browed youth, the budding girl, and the good old grandam, still knitting in the warmest place. The aged woman looked up from her task, and, with fingers ever busy, was the next to speak.

“Old folks have their notions,” said she, “as well as young ones. You’ve been wishing and planning; and letting your heads run on one thing and another, till you’ve set my mind a-wandering too. Now what should an old woman wish for, when she can go but a step or two before she comes to her grave? Children, it will haunt me night and day till I tell you.”

“What is it, mother?” cried the husband and wife at once.

Then the old woman, with an air of mystery which drew the circle closer round the fire, informed them that she had provided her grave-clothes some years before–a nice linen shroud, a cap with a muslin ruff, and everything of a finer sort than she had worn since her wedding day. But this evening an old superstition had strangely recurred to her. It used to be said, in her younger days, that if anything were amiss with a corpse, if only the ruff were not smooth, or the cap did not set right, the corpse in the coffin and beneath the clods would strive to put up its cold hands and arrange it. The bare thought made her nervous.

“Don’t talk so, grandmother!” said the girl, shuddering.

“Now,” continued the old woman, with singular earnestness, yet smiling strangely at her own folly, “I want one of you, my children- when your mother is dressed and in the coffin–I want one of you to hold a looking-glass over my face. Who knows but I may take a glimpse at myself, and see whether all’s right?”

“Old and young, we dream of graves and monuments,” murmured the stranger youth. “I wonder how mariners feel when the ship is sinking, and they, unknown and undistinguished, are to be buried together in the ocean–that wide and nameless sepulchre?”

For a moment, the old woman’s ghastly conception so engrossed the minds of her hearers that a sound abroad in the night, rising like the roar of a blast, had grown broad, deep, and terrible, before the fated group were conscious of it. The house and all within it trembled; the foundations of the earth seemed to be shaken, as if this awful sound were the peal of the last trump. Young and old exchanged one wild glance, and remained an instant, pale, affrighted, without utterance, or power to move. Then the same shriek burst simultaneously from all their lips.

“The Slide! The Slide!”

The simplest words must intimate, but not portray, the unutterable horror of the catastrophe. The victims rushed from their cottage, and sought refuge in what they deemed a safer spot–where, in contemplation of such an emergency, a sort of barrier had been reared. Alas! they had quitted their security, and fled right into the pathway of destruction. Down came the whole side of the mountain, in a cataract of ruin. Just before it reached the house, the stream broke into two branches–shivered not a window there, but overwhelmed the whole vicinity, blocked up the road, and annihilated everything in its dreadful course. Long ere the thunder of the great Slide had ceased to roar among the mountains, the mortal agony had been endured, and the victims were at peace. Their bodies were never found.

The next morning, the light smoke was seen stealing from the cottage chimney up the mountain side. Within, the fire was yet smouldering on the hearth, and the chairs in a circle round it, as if the inhabitants had but gone forth to view the devastation of the Slide, and would shortly return, to thank Heaven for their miraculous escape. All had left separate tokens, by which those who had known the family were made to shed a tear for each. Who has not heard their name? The story has been told far and wide, and will forever be a legend of these mountains. Poets have sung their fate.

There were circumstances which led some to suppose that a stranger had been received into the cottage on this awful night, and had shared the catastrophe of all its inmates. Others denied that there were sufficient grounds for such a conjecture. Wo for the high-souled youth, with his dream of Earthly Immortality! His name and person utterly unknown; his history, his way of life, his plans, a mystery never to be solved, his death and his existence equally a doubt! Whose was the agony of that death moment?

Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804-1864)

The Ambitious Guest

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #Short Stories Archive, Archive G-H

Ben jij het poëzietalent van het jaar 2017?

Ben jij het poëzietalent van het jaar 2017?

Jouw gedicht in een dichtbundel? Dat kan! Doe mee aan de dichtwedstrijd Doe Maar Dicht Maar. Je hoeft geen doorgewinterd dichter te zijn om mee te doen. Je hoeft ook geen ‘klassiek’ gedicht te schrijven; een rap of een songtekst mag ook! Laat dus vooral je fantasie de vrije loop.

Poëziepaleis zoekt talent!

Kun jij goed schrijven? Ben jij creatief met woorden en heb je gevoel voor dichten, rappen of songteksten schrijven? Doe dan gauw mee met de dichtwedstrijd Doe Maar Dicht Maar. De honderd beste gedichten winnen een plekje in een mooie dichtbundel!

Hoe kun je meedoen?

Stuur voor 5 februari 2017 maximaal 3 gedichten in van elk maximaal 24 regels via het wedstrijdformulier. Vanzelfsprekend schrijf jij deze gedichten zelf; plagiaat is verboden! Omdat er duizenden gedichten worden ingestuurd, krijgen alleen de honderd winnaars begin mei 2016 bericht. De uitslag komt half mei op de website te staan.

Wanneer mag je meedoen?

Wanneer mag je meedoen?

– Je bent 12 t/m 18 jaar;

– Je spreekt en schrijft Nederlands;

– Je zit op het VMBO/ Havo/ VWO/ ROC of MBO;

– Je zit op de eerste t/m de derde graad van het secundair onderwijs in België.

Wat kun je winnen?

Van de duizenden inzendingen worden 100 gedichten gekozen die een plekje in de dichtbundel Doe Maar Dicht Maar 2015/2016 krijgen. De tien allerbeste dichters, vijf winnaars uit de leeftijdscategorie 12 t/m 14 jaar en vijf winnaars uit de leeftijdscategorie 15 t/m 18 jaar, krijgen een uniek cadeau met hun gedicht erop. De winnaars uit deze categorieën winnen een hoofdprijs!

Wil je tips voor het schrijven van gedichten? Neem dan een kijkje bij Tips & Inspiratie.

# Meer te vinden op de website van het poëziepaleis

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, Art & Literature News, Children's Poetry, MODERN POETRY, POETRY ARCHIVE

Kinderen en poëzie 2017

Kinderen en poëzie 2017

Kinderen en Poëzie is een landelijke dichtwedstrijd voor kinderen van 6 t/m 12 jaar die het leuk vinden om gedichten te schrijven. Je kunt deelnemen via school, maar je kunt ook thuis of op de BSO een gedicht schrijven en dat insturen. Vul het wedstrijdformulier in of stuur je gedicht per post. Vraag je ouders, juf of meester om je te helpen als je het niet snapt.

Wanneer mag je meedoen?

– Als je 6 t/m 12 jaar oud bent;

– Als je in groep 3 t/m 8 van de basisschool zit;

– Als je op het speciaal onderwijs zit; je mag dan zelfs meedoen als je ouder bent dan 12. Geef dit dan aan bij opmerkingen op het wedstrijdformulier.

Hoe kun je meedoen?

Stuur voor 5 februari 2017 maximaal drie zelfbedachte gedichten in. Gedichten in braille, een groepsgedicht of een gedicht in een andere taal (stuur wel even een vertaling mee) zijn ook welkom. Alles wat je maar wilt, zolang het maar zelfverzonnen en -geschreven is!

Wanneer mag je meedoen?

Wanneer mag je meedoen?

– Als je 6 t/m 12 jaar oud bent;

– Als je in groep 3 t/m 8 van de basisschool zit;

– Als je op het speciaal onderwijs zit; je mag dan zelfs meedoen als je ouder bent dan 12. Geef dit dan aan bij opmerkingen op het wedstrijdformulier.

Wat kun je winnen?

Als je meedoet aan de wedstrijd kun je leuke prijzen winnen, waaronder een plekje in een echte dichtbundel. Je maakt ook kans op één van de twee hoofdprijzen. Er is een hoofdprijs voor de middenbouw en een hoofdprijs voor de bovenbouw. Daarnaast is er ook nog een speciale prijs van de Kinderjury. Genoeg redenen om mee te doen dus!

Poëziepaleis zoekt talent!

Kinderen van 6 t/m 12 jaar

Wil je tips voor het schrijven van gedichten? Neem dan een kijkje bij tips & Inspiratie.

# Meer informatie op website poëziepaleis

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, Art & Literature News, Children's Poetry, MODERN POETRY

Sara Teasdale

(1884 – 1933)

“Only in Sleep”

Only in sleep I see their faces,

Children I played with when I was a child,

Louise comes back with her brown hair braided,

Annie with ringlets warm and wild.

Only in sleep Time is forgotten—

What may have come to them, who can know?

Yet we played last night as long ago,

And the doll-house stood at the turn of the stair.

The years had not sharpened their smooth round faces,

I met their eyes and found them mild—

Do they, too, dream of me, I wonder,

And for them am I too a child?

Sara Teasdale

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Teasdale, Sara

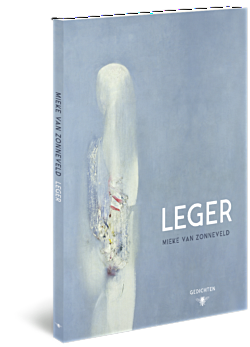

De salon van zaterdag 28 januari 2017 staat in het teken van Mieke van Zonneveld; zij presenteert haar debuutbundel ‘Leger’, uitgegeven door De Bezige Bij, en draagt eruit voor. Het programma brengt dichters die haar inspireren uit het heden en verleden, afgewisseld door passende muziek. Roland Holstprijswinnaar en voormalige stadsdichter van Amsterdam Menno Wigman draagt voor uit o.a. zijn laatste bundel ‘Slordig met geluk’. Simon Mulder draagt voor uit favoriete werken van J. H. Leopold.

De salon van zaterdag 28 januari 2017 staat in het teken van Mieke van Zonneveld; zij presenteert haar debuutbundel ‘Leger’, uitgegeven door De Bezige Bij, en draagt eruit voor. Het programma brengt dichters die haar inspireren uit het heden en verleden, afgewisseld door passende muziek. Roland Holstprijswinnaar en voormalige stadsdichter van Amsterdam Menno Wigman draagt voor uit o.a. zijn laatste bundel ‘Slordig met geluk’. Simon Mulder draagt voor uit favoriete werken van J. H. Leopold.

Presentatie debuut Mieke van Zonneveld met Menno Wigman

Op zaterdagavond 28 januari presenteert het Feest der Poëzie de dichter Mieke van Zonneveld met haar bundel ‘Leger’, uitgegeven door De Bezige Bij. Het programma vindt plaats in de prachtige omgeving van het Pianola Museum te Amsterdam. Naast een voordracht van Mieke van Zonneveld uit de nieuwe bundel, zal ook Menno Wigman, voormalig stadsdichter van Amsterdam en winnaar van de A. Roland Holstprijs, voordragen. Ook zijn er gedichten van J. H. Leopold en een pianorecital van Henk van Zonneveld.

Tevens vindt op 18 februari de akoestische reprise van Project Diepenbrock, onze voorstelling tijdens het Feest der Poëzie van 2014, plaats, met chansontrio En Vrac, Mieke van Zonneveld en Simon Mulder.

Praktische informatie

Datum: zaterdag 28 januari 2017

Tijd: zaal open: 20 uur, aanvang: 20:30 uur

Locatie: Pianola Museum, Westerstraat 106, Amsterdam

Reserveren via info@pianola.nl wordt zeer aangeraden.

Meer informatie: www.feestderpoezie.nl onder ‘Salon der Verzen’

Mieke van Zonneveld (1989) – lid van collectief het Feest der Poëzie sinds het begin in 2008 – studeerde Nederlands en oudheidkunde aan de Vrije Universiteit en rondt momenteel haar onderzoeksmaster letterkunde af. Ze won in 2014 de landelijke Turing Gedichtenwedstrijd. Zij debuteert met een klassiek aandoende bundel over liefde en vriendschap, over ziekte en geloof. Leger is een gemystificeerd en genadeloos zelfonderzoek van een jonge dichter die de dood in de ogen heeft gekeken. Uitgeverij is Bezige Bij.

Mieke van Zonneveld debuteert met een klassiek aandoende bundel over liefde en vriendschap, over ziekte en geloof. Haar poëzie wekt de indruk van volledige helderheid, maar ze versluiert tegelijk. De eenvoud van woorden roept een grootsheid van beelden op waaronder telkens het risico sluimert uit het volle leven geknipt te worden. Slechts in dromen bestaat de mogelijkheid barrières te beslechten. Leger is een gemystificeerd en genadeloos zelfonderzoek van een jonge dichter die de dood in de ogen heeft gekeken.

Mieke van Zonneveld publiceerde enkele gedichten in voormalig literair tijdschrift De tweede ronde en in het ambachtelijk gedrukte Avantgaerde. Als lid van het Feest der Poëzie treedt ze af en toe op tijdens literaire salons. Ze is bezig met haar masteronderzoek Letterkunde aan de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam.

# Meer informatie op website feestderpoezie

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Archive Y-Z, Art & Literature News, City Poets / Stadsdichters, Feest der Poëzie, Leopold, J.H., Literary Events, MODERN POETRY, MUSIC, Wigman, Menno

A Physiologist’s Wife

A Physiologist’s Wife

by Arthur Conan Doyle

Professor Ainslie Grey had not come down to breakfast at the usual hour. The presentation chiming-clock which stood between the terra-cotta busts of Claude Bernard and of John Hunter upon the dining-room mantelpiece had rung out the half-hour and the three-quarters. Now its golden hand was verging upon the nine, and yet there were no signs of the master of the house.

It was an unprecedented occurrence. During the twelve years that she had kept house for him, his youngest sister had never known him a second behind his time. She sat now in front of the high silver coffee-pot, uncertain whether to order the gong to be resounded or to wait on in silence. Either course might be a mistake. Her brother was not a man who permitted mistakes.

Miss Ainslie Grey was rather above the middle height, thin, with peering, puckered eyes, and the rounded shoulders which mark the bookish woman. Her face was long and spare, flecked with colour above the cheek-bones, with a reasonable, thoughtful forehead, and a dash of absolute obstinacy in her thin lips and prominent chin. Snow white cuffs and collar, with a plain dark dress, cut with almost Quaker-like simplicity, bespoke the primness of her taste. An ebony cross hung over her flattened chest. She sat very upright in her chair, listening with raised eyebrows, and swinging her eye-glasses backwards and forwards with a nervous gesture which was peculiar to her.

Suddenly she gave a sharp, satisfied jerk of the head, and began to pour out the coffee. From outside there came the dull thudding sound of heavy feet upon thick carpet. The door swung open, and the Professor entered with a quick, nervous step. He nodded to his sister, and seating himself at the other side of the table, began to open the small pile of letters which lay beside his plate.

Professor Ainslie Grey was at that time forty-three years of age—nearly twelve years older than his sister. His career had been a brilliant one. At Edinburgh, at Cambridge, and at Vienna he had laid the foundations of his great reputation, both in physiology and in zoology.

His pamphlet, On the Mesoblastic Origin of Excitomotor Nerve Roots, had won him his fellowship of the Royal Society; and his researches, Upon the Nature of Bathybius, with some Remarks upon Lithococci, had been translated into at least three European languages. He had been referred to by one of the greatest living authorities as being the very type and embodiment of all that was best in modern science. No wonder, then, that when the commercial city of Birchespool decided to create a medical school, they were only too glad to confer the chair of physiology upon Mr. Ainslie Grey. They valued him the more from the conviction that their class was only one step in his upward journey, and that the first vacancy would remove him to some more illustrious seat of learning.

In person he was not unlike his sister. The same eyes, the same contour, the same intellectual forehead. His lips, however, were firmer, and his long, thin, lower jaw was sharper and more decided. He ran his finger and thumb down it from time to time, as he glanced over his letters.

“Those maids are very noisy,” he remarked, as a clack of tongues sounded in the distance.

“It is Sarah,” said his sister; “I shall speak about it.”

She had handed over his coffee-cup, and was sipping at her own, glancing furtively through her narrowed lids at the austere face of her brother.

“The first great advance of the human race,” said the Professor, “was when, by the development of their left frontal convolutions, they attained the power of speech. Their second advance was when they learned to control that power. Woman has not yet attained the second stage.”

He half closed his eyes as he spoke, and thrust his chin forward, but as he ceased he had a trick of suddenly opening both eyes very wide and staring sternly at his interlocutor.

“I am not garrulous, John,” said his sister.

“No, Ada; in many respects you approach the superior or male type.”

The Professor bowed over his egg with the manner of one who utters a courtly compliment; but the lady pouted, and gave an impatient little shrug of her shoulders.

“You were late this morning, John,” she remarked, after a pause.

“Yes, Ada; I slept badly. Some little cerebral congestion, no doubt due to over-stimulation of the centers of thought. I have been a little disturbed in my mind.”

His sister stared across at him in astonishment. The Professor’s mental processes had hitherto been as regular as his habits. Twelve years’ continual intercourse had taught her that he lived in a serene and rarefied atmosphere of scientific calm, high above the petty emotions which affect humbler minds.

“You are surprised, Ada,” he remarked. “Well, I cannot wonder at it. I should have been surprised myself if I had been told that I was so sensitive to vascular influences. For, after all, all disturbances are vascular if you probe them deep enough. I am thinking of getting married.”

“Not Mrs. O’James” cried Ada Grey, laying down her egg-spoon.

“My dear, you have the feminine quality of receptivity very remarkably developed. Mrs. O’James is the lady in question.”

“But you know so little of her. The Esdailes themselves know so little. She is really only an acquaintance, although she is staying at The Lindens. Would it not be wise to speak to Mrs. Esdaile first, John?”

“I do not think, Ada, that Mrs. Esdaile is at all likely to say anything which would materially affect my course of action. I have given the matter due consideration. The scientific mind is slow at arriving at conclusions, but having once formed them, it is not prone to change. Matrimony is the natural condition of the human race. I have, as you know, been so engaged in academical and other work, that I have had no time to devote to merely personal questions. It is different now, and I see no valid reason why I should forego this opportunity of seeking a suitable helpmate.”

“And you are engaged?”

“Hardly that, Ada. I ventured yesterday to indicate to the lady that I was prepared to submit to the common lot of humanity. I shall wait upon her after my morning lecture, and learn how far my proposals meet with her acquiescence. But you frown, Ada!”

His sister started, and made an effort to conceal her expression of annoyance. She even stammered out some few words of congratulation, but a vacant look had come into her brother’s eyes, and he was evidently not listening to her.

“I am sure, John, that I wish you the happiness which you deserve. If I hesitated at all, it is because I know how much is at stake, and because the thing is so sudden, so unexpected.” Her thin white hand stole up to the black cross upon her bosom. “These are moments when we need guidance, John. If I could persuade you to turn to spiritual——”

The Professor waved the suggestion away with a deprecating hand.

“It is useless to reopen that question,” he said. “We cannot argue upon it. You assume more than I can grant. I am forced to dispute your premises. We have no common basis.”

His sister sighed.

“You have no faith,” she said.

“I have faith in those great evolutionary forces which are leading the human race to some unknown but elevated goal.”

“You believe in nothing.”

“On the contrary, my dear Ada, I believe in the differentiation of protoplasm.”

She shook her head sadly. It was the one subject upon which she ventured to dispute her brother’s infallibility.

“This is rather beside the question,” remarked the Professor, folding up his napkin. “If I am not mistaken, there is some possibility of another matrimonial event occurring in the family. Eh, Ada? What!”

His small eyes glittered with sly facetiousness as he shot a twinkle at his sister. She sat very stiff, and traced patterns upon the cloth with the sugar-tongs.

“Dr. James M’Murdo O’Brien——” said the Professor, sonorously.

“Don’t, John, don’t!” cried Miss Ainslie Grey.

“Dr. James M’Murdo O’Brien,” continued her brother inexorably, “is a man who has already made his mark upon the science of the day. He is my first and my most distinguished pupil. I assure you, Ada, that his ‘Remarks upon the Bile-Pigments, with special reference to Urobilin,’ is likely to live as a classic. It is not too much to say that he has revolutionised our views about urobilin.”

He paused, but his sister sat silent, with bent head and flushed cheeks. The little ebony cross rose and fell with her hurried breathings.

“Dr. James M’Murdo O’Brien has, as you know, the offer of the physiological chair at Melbourne. He has been in Australia five years, and has a brilliant future before him. To-day he leaves us for Edinburgh, and in two months’ time, he goes out to take over his new duties. You know his feeling towards you. It, rests with you as to whether he goes out alone. Speaking for myself, I cannot imagine any higher mission for a woman of culture than to go through life in the company of a man who is capable of such a research as that which Dr. James M’Murdo O’Brien has brought to a successful conclusion.”

“He has not spoken to me,” murmured the lady.

“Ah, there are signs which are more subtle than speech,” said her brother, wagging his head. “But you are pale. Your vasomotor system is excited. Your arterioles have contracted. Let me entreat you to compose yourself. I think I hear the carriage. I fancy that you may have a visitor this morning, Ada. You will excuse me now.”

With a quick glance at the clock he strode off into the hall, and within a few minutes he was rattling in his quiet, well-appointed brougham through the brick-lined streets of Birchespool.

His lecture over, Professor Ainslie Grey paid a visit to his laboratory, where he adjusted several scientific instruments, made a note as to the progress of three separate infusions of bacteria, cut half-a-dozen sections with a microtome, and finally resolved the difficulties of seven different gentlemen, who were pursuing researches in as many separate lines of inquiry. Having thus conscientiously and methodically completed the routine of his duties, he returned to his carriage and ordered the coachman to drive him to The Lindens. His face as he drove was cold and impassive, but he drew his fingers from time to time down his prominent chin with a jerky, twitchy movement.

The Lindens was an old-fashioned, ivy-clad house which had once been in the country, but was now caught in the long, red-brick feelers of the growing city. It still stood back from the road in the privacy of its own grounds. A winding path, lined with laurel bushes, led to the arched and porticoed entrance. To the right was a lawn, and at the far side, under the shadow of a hawthorn, a lady sat in a garden-chair with a book in her hands. At the click of the gate she started, and the Professor, catching sight of her, turned away from the door, and strode in her direction.

“What! won’t you go in and see Mrs. Esdaile?” she asked, sweeping out from under the shadow of the hawthorn.

She was a small woman, strongly feminine, from the rich coils of her light-coloured hair to the dainty garden slipper which peeped from under her cream-tinted dress. One tiny well-gloved hand was outstretched in greeting, while the other pressed a thick, green-covered volume against her side. Her decision and quick, tactful manner bespoke the mature woman of the world; but her upraised face had preserved a girlish and even infantile expression of innocence in its large, fearless, grey eyes, and sensitive, humorous mouth. Mrs. O’James was a widow, and she was two-and-thirty years of age; but neither fact could have been deduced from her appearance.

“You will surely go in and see Mrs. Esdaile,” she repeated, glancing up at him with eyes which had in them something between a challenge and a caress.

“I did not come to see Mrs. Esdaile,” he answered, with no relaxation of his cold and grave manner; “I came to see you.”

“I am sure I should be highly honoured,” she said, with just the slightest little touch of brogue in her accent. “What are the students to do without their Professor?”

“I have already completed my academic duties. Take my arm, and we shall walk in the sunshine. Surely we cannot wonder that Eastern people should have made a deity of the sun. It is the great beneficent force of Nature—man’s ally against cold, sterility, and all that is abhorrent to him. What were you reading?”

“Hale’s Matter and Life.”

The Professor raised his thick eyebrows.

“Hale!” he said, and then again in a kind of whisper, “Hale!”

“You differ from him?” she asked.

“It is not I who differ from him. I am only a monad—a thing of no moment. The whole tendency of the highest plane of modern thought differs from him. He defends the indefensible. He is an excellent observer, but a feeble reasoner. I should not recommend you to found your conclusions upon Hale.”

“I must read Nature’s Chronicle to counteract his pernicious influence,” said Mrs. O’James, with a soft, cooing laugh.

Nature’s Chronicle was one of the many books in which Professor Ainslie Grey had enforced the negative doctrines of scientific agnosticism.

“It is a faulty work,” said he; “I cannot recommend it. I would rather refer you to the standard writings of some of my older and more eloquent colleagues.”

There was a pause in their talk as they paced up and down on the green, velvet-like lawn in the genial sunshine.

“Have you thought at all,” he asked at last, “of the matter upon which I spoke to you last night?”

She said nothing, but walked by his side with her eyes averted and her face aslant.

“I would not hurry you unduly,” he continued. “I know that it is a matter which can scarcely be decided off-hand. In my own case, it cost me some thought before I ventured to make the suggestion. I am not an emotional man, but I am conscious in your presence of the great evolutionary instinct which makes either sex the complement of the other.”

“You believe in love, then?” she asked, with a twinkling, upward glance.

“I am forced to.”

“And yet you can deny the soul?”

“How far these questions are psychic and how far material is still sub judice,” said the Professor, with an air of toleration. “Protoplasm may prove to be the physical basis of love as well as of life.”

“How inflexible you are!” she exclaimed; “you would draw love down to the level of physics.”

“Or draw physics up to the level of love.”

“Come, that is much better,” she cried, with her sympathetic laugh. “That is really very pretty, and puts science in quite a delightful light.”

Her eyes sparkled, and she tossed her chin with the pretty, wilful air of a woman who is mistress of the situation.

“I have reason to believe,” said the Professor, “that my position here will prove to be only a stepping-stone to some wider scene of scientific activity. Yet, even here, my chair brings me in some fifteen hundred pounds a year, which is supplemented by a few hundreds from my books. I should therefore be in a position to provide you with those comforts to which you are accustomed. So much for my pecuniary position. As to my constitution, it has always been sound. I have never suffered from any illness in my life, save fleeting attacks of cephalalgia, the result of too prolonged a stimulation of the centres of cerebration. My father and mother had no sign of any morbid diathesis, but I will not conceal from you that my grandfather was afflicted with podagra.”

Mrs. O’James looked startled.

“Is that very serious?” she asked.

“It is gout,” said the Professor.

“Oh, is that all? It sounded much worse than that.”

“It is a grave taint, but I trust that I shall not be a victim to atavism. I have laid these facts before you because they are factors which cannot be overlooked in forming your decision. May I ask now whether you see your way to accepting my proposal?”

He paused in his walk, and looked earnestly and expectantly down at her.

A struggle was evidently going on in her mind. Her eyes were cast down, her little slipper tapped the lawn, and her fingers played nervously with her chatelain. Suddenly, with a sharp, quick gesture which had in it something of ABANDON and recklessness, she held out her hand to her companion.

“I accept,” she said.

They were standing under the shadow of the hawthorn. He stooped gravely down, and kissed her glove-covered fingers.

“I trust that you may never have cause to regret your decision,” he said.

“I trust that you never may,” she cried, with a heaving breast.

There were tears in her eyes, and her lips twitched with some strong emotion.

“Come into the sunshine again,” said he. “It is the great restorative. Your nerves are shaken. Some little congestion of the medulla and pons. It is always instructive to reduce psychic or emotional conditions to their physical equivalents. You feel that your anchor is still firm in a bottom of ascertained fact.”

“But it is so dreadfully unromantic,” said Mrs. O’James, with her old twinkle.

“Romance is the offspring of imagination and of ignorance. Where science throws her calm, clear light there is happily no room for romance.”

“But is not love romance?” she asked.

“Not at all. Love has been taken away from the poets, and has been brought within the domain of true science. It may prove to be one of the great cosmic elementary forces. When the atom of hydrogen draws the atom of chlorine towards it to form the perfected molecule of hydrochloric acid, the force which it exerts may be intrinsically similar to that which draws me to you. Attraction and repulsion appear to be the primary forces. This is attraction.”

“And here is repulsion,” said Mrs. O’James, as a stout, florid lady came sweeping across the lawn in their direction. “So glad you have come out, Mrs. Esdaile! Here is Professor Grey.”

“How do you do, Professor?” said the lady, with some little pomposity of manner. “You were very wise to stay out here on so lovely a day. Is it not heavenly?”

“It is certainly very fine weather,” the Professor answered.

“Listen to the wind sighing in the trees!” cried Mrs. Esdaile, holding up one finger. “It is Nature’s lullaby. Could you not imagine it, Professor Grey, to be the whisperings of angels?”

“The idea had not occurred to me, madam.”

“Ah, Professor, I have always the same complaint against you. A want of rapport with the deeper meanings of nature. Shall I say a want of imagination. You do not feel an emotional thrill at the singing of that thrush?”

“I confess that I am not conscious of one, Mrs. Esdaile.”

“Or at the delicate tint of that background of leaves? See the rich greens!”

“Chlorophyll,” murmured the Professor.

“Science is so hopelessly prosaic. It dissects and labels, and loses sight of the great things in its attention to the little ones. You have a poor opinion of woman’s intellect, Professor Grey. I think that I have heard you say so.”

“It is a question of avoirdupois,” said the Professor, closing his eyes and shrugging his shoulders. “The female cerebrum averages two ounces less in weight than the male. No doubt there are exceptions. Nature is always elastic.”

“But the heaviest thing is not always the strongest,” said Mrs. O’James, laughing. “Isn’t there a law of compensation in science? May we not hope to make up in quality for what we lack in quantity?”

“I think not,” remarked the Professor, gravely. “But there is your luncheon-gong. No, thank you, Mrs. Esdaile, I cannot stay. My carriage is waiting. Good-bye. Good-bye, Mrs. O’James.”

He raised his hat and stalked slowly away among the laurel bushes.

“He has no taste,” said Mrs. Esdaile—“no eye for beauty.”

“On the contrary,” Mrs. O’James answered, with a saucy little jerk of the chin. “He has just asked me to be his wife.”

As Professor Ainslie Grey ascended the steps of his house, the hall-door opened and a dapper gentleman stepped briskly out. He was somewhat sallow in the face, with dark, beady eyes, and a short, black beard with an aggressive bristle. Thought and work had left their traces upon his face, but he moved with the brisk activity of a man who had not yet bade good-bye to his youth.

“I’m in luck’s way,” he cried. “I wanted to see you.”

“Then come back into the library,” said the Professor; “you must stay and have lunch with us.”

The two men entered the hall, and the Professor led the way into his private sanctum. He motioned his companion into an arm-chair.

“I trust that you have been successful, O’Brien,” said he. “I should be loath to exercise any undue pressure upon my sister Ada; but I have given her to understand that there is no one whom I should prefer for a brother-in-law to my most brilliant scholar, the author of Some Remarks upon the Bile-Pigments, with special reference to Urobilin.”

“You are very kind, Professor Grey—you have always been very kind,” said the other. “I approached Miss Grey upon the subject; she did not say No.”

“She said Yes, then?”

“No; she proposed to leave the matter open until my return from Edinburgh. I go to-day, as you know, and I hope to commence my research to-morrow.”

“On the comparative anatomy of the vermiform appendix, by James M’Murdo O’Brien,” said the Professor, sonorously. “It is a glorious subject—a subject which lies at the very root of evolutionary philosophy.”

“Ah! she is the dearest girl,” cried O’Brien, with a sudden little spurt of Celtic enthusiasm—“she is the soul of truth and of honour.”

“The vermiform appendix——” began the Professor.

“She is an angel from heaven,” interrupted the other. “I fear that it is my advocacy of scientific freedom in religious thought which stands in my way with her.”

“You must not truckle upon that point. You must be true to your convictions; let there be no compromise there.”

“My reason is true to agnosticism, and yet I am conscious of a void—a vacuum. I had feelings at the old church at home between the scent of the incense and the roll of the organ, such as I have never experienced in the laboratory or the lecture-room.”

“Sensuous-purely sensuous,” said the Professor, rubbing his chin. “Vague hereditary tendencies stirred into life by the stimulation of the nasal and auditory nerves.”

“Maybe so, maybe so,” the younger man answered thoughtfully. “But this was not what I wished to speak to you about. Before I enter your family, your sister and you have a claim to know all that I can tell you about my career. Of my worldly prospects I have already spoken to you. There is only one point which I have omitted to mention. I am a widower.”

The Professor raised his eyebrows.

“This is news indeed,” said he.

“I married shortly after my arrival in Australia. Miss Thurston was her name. I met her in society. It was a most unhappy match.”

Some painful emotion possessed him. His quick, expressive features quivered, and his white hands tightened upon the arms of the chair. The Professor turned away towards the window.

“You are the best judge,” he remarked “but I should not think that it was necessary to go into details.”

“You have a right to know everything—you and Miss Grey. It is not a matter on which I can well speak to her direct. Poor Jinny was the best of women, but she was open to flattery, and liable to be misled by designing persons. She was untrue to me, Grey. It is a hard thing to say of the dead, but she was untrue to me. She fled to Auckland with a man whom she had known before her marriage. The brig which carried them foundered, and not a soul was saved.”

“This is very painful, O’Brien,” said the Professor, with a deprecatory motion of his hand. “I cannot see, however, how it affects your relation to my sister.”

“I have eased my conscience,” said O’Brien, rising from his chair; “I have told you all that there is to tell. I should not like the story to reach you through any lips but my own.”

“You are right, O’Brien. Your action has been most honourable and considerate. But you are not to blame in the matter, save that perhaps you showed a little precipitancy in choosing a life-partner without due care and inquiry.”

O’Brien drew his hand across his eyes.

“Poor girl!” he cried. “God help me, I love her still! But I must go.”

“You will lunch with us?”

“No, Professor; I have my packing still to do. I have already bade Miss Grey adieu. In two months I shall see you again.”

“You will probably find me a married man.”

“Married!”

“Yes, I have been thinking of it.”

“My dear Professor, let me congratulate you with all my heart. I had no idea. Who is the lady?”

“Mrs. O’James is her name—a widow of the same nationality as yourself. But to return to matters of importance, I should be very happy to see the proofs of your paper upon the vermiform appendix. I may be able to furnish you with material for a footnote or two.”

“Your assistance will be invaluable to me,” said O’Brien, with enthusiasm, and the two men parted in the hall. The Professor walked back into the dining-room, where his sister was already seated at the luncheon-table.

“I shall be married at the registrar’s,” he remarked; “I should strongly recommend you to do the same.”

Professor Ainslie Grey was as good as his word. A fortnight’s cessation of his classes gave him an opportunity which was too good to let pass. Mrs. O’James was an orphan, without relations and almost without friends in the country. There was no obstacle in the way of a speedy wedding. They were married, accordingly, in the quietest manner possible, and went off to Cambridge together, where the Professor and his charming wife were present at several academic observances, and varied the routine of their honeymoon by incursions into biological laboratories and medical libraries. Scientific friends were loud in their congratulations, not only upon Mrs. Grey’s beauty, but upon the unusual quickness and intelligence which she displayed in discussing physiological questions. The Professor was himself astonished at the accuracy of her information. “You have a remarkable range of knowledge for a woman, Jeannette,” he remarked upon more than one occasion. He was even prepared to admit that her cerebrum might be of the normal weight.

One foggy, drizzling morning they returned to Birchespool, for the next day would re-open the session, and Professor Ainslie Grey prided himself upon having never once in his life failed to appear in his lecture-room at the very stroke of the hour. Miss Ada Grey welcomed them with a constrained cordiality, and handed over the keys of office to the new mistress. Mrs. Grey pressed her warmly to remain, but she explained that she had already accepted an invitation which would engage her for some months. The same evening she departed for the south of England.

A couple of days later the maid carried a card just after breakfast into the library where the Professor sat revising his morning lecture. It announced the re-arrival of Dr. James M’Murdo O’Brien. Their meeting was effusively genial on the part of the younger man, and coldly precise on that of his former teacher.

“You see there have been changes,” said the Professor.

“So I heard. Miss Grey told me in her letters, and I read the notice in the British Medical Journal. So it’s really married you are. How quickly and quietly you have managed it all!”

“I am constitutionally averse to anything in the nature of show or ceremony. My wife is a sensible woman—I may even go the length of saying that, for a woman, she is abnormally sensible. She quite agreed with me in the course which I have adopted.”

“And your research on Vallisneria?”

“This matrimonial incident has interrupted it, but I have resumed my classes, and we shall soon be quite in harness again.”

“I must see Miss Grey before I leave England. We have corresponded, and I think that all will be well. She must come out with me. I don’t think I could go without her.”

The Professor shook his head.

“Your nature is not so weak as you pretend,” he said. “Questions of this sort are, after all, quite subordinate to the great duties of life.”

O’Brien smiled.

“You would have me take out my Celtic soul and put in a Saxon one,” he said. “Either my brain is too small or my heart is too big. But when may I call and pay my respects to Mrs. Grey? Will she be at home this afternoon?”

“She is at home now. Come into the morning-room. She will be glad to make your acquaintance.”

They walked across the linoleum-paved hall. The Professor opened the door of the room, and walked in, followed by his friend. Mrs. Grey was sitting in a basket-chair by the window, light and fairy-like in a loose-flowing, pink morning-gown. Seeing a visitor, she rose and swept towards them. The Professor heard a dull thud behind him. O’Brien had fallen back into a chair, with his hand pressed tight to his side.

“Jinny!” he gasped—“Jinny!”

Mrs. Grey stopped dead in her advance, and stared at him with a face from which every expression had been struck out, save one of astonishment and horror. Then with a sharp intaking of the breath she reeled, and would have fallen had the Professor not thrown his long, nervous arm round her.

“Try this sofa,” said he.

She sank back among the cushions with the same white, cold, dead look upon her face. The Professor stood with his back to the empty fireplace and glanced from the one to the other.

“So, O’Brien,” he said at last, “you have already made the acquaintance of my wife!”

“Your wife,” cried his friend hoarsely. “She is no wife of yours. God help me, she is MY wife.”

The Professor stood rigidly upon the hearthrug. His long, thin fingers were intertwined, and his head sunk a little forward. His two companions had eyes only for each other.

“Jinny!” said he.

“James!”

“How could you leave me so, Jinny? How could you have the heart to do it? I thought you were dead. I mourned for your death—ay, and you have made me mourn for you living. You have withered my life.”

She made no answer, but lay back among her cushions with her eyes still fixed upon him.

“Why do you not speak?”

“Because you are right, James. I HAVE treated you cruelly—shamefully. But it is not as bad as you think.”

“You fled with De Horta.”

“No, I did not. At the last moment my better nature prevailed. He went alone. But I was ashamed to come back after what I had written to you. I could not face you. I took passage alone to England under a new name, and here I have lived ever since. It seemed to me that I was beginning life again. I knew that you thought I was drowned. Who could have dreamed that fate would throw us together again! When the Professor asked me——”

She stopped and gave a gasp for breath.

“You are faint,” said the Professor—“keep the head low; it aids the cerebral circulation.” He flattened down the cushion. “I am sorry to leave you, O’Brien; but I have my class duties to look to. Possibly I may find you here when I return.”

With a grim and rigid face he strode out of the room. Not one of the three hundred students who listened to his lecture saw any change in his manner and appearance, or could have guessed that the austere gentleman in front of them had found out at last how hard it is to rise above one’s humanity. The lecture over, he performed his routine duties in the laboratory, and then drove back to his own house. He did not enter by the front door, but passed through the garden to the folding glass casement which led out of the morning-room. As he approached he heard his wife’s voice and O’Brien’s in loud and animated talk. He paused among the rose-bushes, uncertain whether to interrupt them or no. Nothing was further from his nature than play the eavesdropper; but as he stood, still hesitating, words fell upon his ear which struck him rigid and motionless.

“You are still my wife, Jinny,” said O’Brien; “I forgive you from the bottom of my heart. I love you, and I have never ceased to love you, though you had forgotten me.”

“No, James, my heart was always in Melbourne. I have always been yours. I thought that it was better for you that I should seem to be dead.”

“You must choose between us now, Jinny. If you determine to remain here, I shall not open my lips. There shall be no scandal. If, on the other hand, you come with me, it’s little I care about the world’s opinion. Perhaps I am as much to blame as you. I thought too much of my work and too little of my wife.”

The Professor heard the cooing, caressing laugh which he knew so well.

“I shall go with you, James,” she said.

“And the Professor——?”

“The poor Professor! But he will not mind much, James; he has no heart.”

“We must tell him our resolution.”

“There is no need,” said Professor Ainslie Grey, stepping in through the open casement. “I have overheard the latter part of your conversation. I hesitated to interrupt you before you came to a conclusion.”

O’Brien stretched out his hand and took that of the woman. They stood together with the sunshine on their faces. The Professor paused at the casement with his hands behind his back, and his long black shadow fell between them.

“You have come to a wise decision,” said he. “Go back to Australia together, and let what has passed be blotted out of your lives.”

“But you—you——” stammered O’Brien.

The Professor waved his hand.

“Never trouble about me,” he said.

The woman gave a gasping cry.

“What can I do or say?” she wailed. “How could I have foreseen this? I thought my old life was dead. But it has come back again, with all its hopes and its desires. What can I say to you, Ainslie? I have brought shame and disgrace upon a worthy man. I have blasted your life. How you must hate and loathe me! I wish to God that I had never been born!”

“I neither hate nor loathe you, Jeannette,” said the Professor, quietly. “You are wrong in regretting your birth, for you have a worthy mission before you in aiding the life-work of a man who has shown himself capable of the highest order of scientific research. I cannot with justice blame you personally for what has occurred. How far the individual monad is to be held responsible for hereditary and engrained tendencies, is a question upon which science has not yet said her last word.”

He stood with his finger-tips touching, and his body inclined as one who is gravely expounding a difficult and impersonal subject. O’Brien had stepped forward to say something, but the other’s attitude and manner froze the words upon his lips. Condolence or sympathy would be an impertinence to one who could so easily merge his private griefs in broad questions of abstract philosophy.

“It is needless to prolong the situation,” the Professor continued, in the same measured tones. “My brougham stands at the door. I beg that you will use it as your own. Perhaps it would be as well that you should leave the town without unnecessary delay. Your things, Jeannette, shall be forwarded.”

O’Brien hesitated with a hanging head.

“I hardly dare offer you my hand,” he said.

“On the contrary. I think that of the three of us you come best out of the affair. You have nothing to be ashamed of.”

“Your sister——”

“I shall see that the matter is put to her in its true light. Good-bye! Let me have a copy of your recent research. Good-bye, Jeannette!”

“Good-bye!”

Their hands met, and for one short moment their eyes also. It was only a glance, but for the first and last time the woman’s intuition cast a light for itself into the dark places of a strong man’s soul. She gave a little gasp, and her other hand rested for an instant, as white and as light as thistle-down, upon his shoulder.

“James, James!” she cried. “Don’t you see that he is stricken to the heart?”

He turned her quietly away from him.

“I am not an emotional man,” he said. “I have my duties—my research on Vallisneria. The brougham is there. Your cloak is in the hall. Tell John where you wish to be driven. He will bring you anything you need. Now go.”

His last two words were so sudden, so volcanic, in such contrast to his measured voice and mask-like face, that they swept the two away from him. He closed the door behind them and paced slowly up and down the room. Then he passed into the library and looked out over the wire blind. The carriage was rolling away. He caught a last glimpse of the woman who had been his wife. He saw the feminine droop of her head, and the curve of her beautiful throat.

Under some foolish, aimless impulse, he took a few quick steps towards the door. Then he turned, and throwing himself into his study-chair he plunged back into his work.

There was little scandal about this singular domestic incident. The Professor had few personal friends, and seldom went into society. His marriage had been so quiet that most of his colleagues had never ceased to regard him as a bachelor. Mrs. Esdaile and a few others might talk, but their field for gossip was limited, for they could only guess vaguely at the cause of this sudden separation.

There was little scandal about this singular domestic incident. The Professor had few personal friends, and seldom went into society. His marriage had been so quiet that most of his colleagues had never ceased to regard him as a bachelor. Mrs. Esdaile and a few others might talk, but their field for gossip was limited, for they could only guess vaguely at the cause of this sudden separation.

The Professor was as punctual as ever at his classes, and as zealous in directing the laboratory work of those who studied under him. His own private researches were pushed on with feverish energy. It was no uncommon thing for his servants, when they came down of a morning, to hear the shrill scratchings of his tireless pen, or to meet him on the staircase as he ascended, grey and silent, to his room. In vain his friends assured him that such a life must undermine his health. He lengthened his hours until day and night were one long, ceaseless task.

Gradually under this discipline a change came over his appearance. His features, always inclined to gauntness, became even sharper and more pronounced. There were deep lines about his temples and across his brow. His cheek was sunken and his complexion bloodless. His knees gave under him when he walked; and once when passing out of his lecture-room he fell and had to be assisted to his carriage.

This was just before the end of the session and soon after the holidays commenced the professors who still remained in Birchespool were shocked to hear that their brother of the chair of physiology had sunk so low that no hopes could be entertained of his recovery. Two eminent physicians had consulted over his case without being able to give a name to the affection from which he suffered. A steadily decreasing vitality appeared to be the only symptom—a bodily weakness which left the mind unclouded. He was much interested himself in his own case, and made notes of his subjective sensations as an aid to diagnosis. Of his approaching end he spoke in his usual unemotional and somewhat pedantic fashion. “It is the assertion,” he said, “of the liberty of the individual cell as opposed to the cell-commune. It is the dissolution of a co-operative society. The process is one of great interest.”

And so one grey morning his co-operative society dissolved. Very quietly and softly he sank into his eternal sleep. His two physicians felt some slight embarrassment when called upon to fill in his certificate.

“It is difficult to give it a name,” said one.

“Very,” said the other.

“If he were not such an unemotional man, I should have said that he had died from some sudden nervous shock—from, in fact, what the vulgar would call a broken heart.”

“I don’t think poor Grey was that sort of a man at all.”

“Let us call it cardiac, anyhow,” said the older physician.

So they did so.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859 – 1930)

Round the Red Lamp: Being Facts and Fancies of Medical Life

Physiologist’s Wife (#08)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Doyle, Arthur Conan, Doyle, Arthur Conan, DRUGS & DISEASE & MEDICINE & LITERATURE, Round the Red Lamp

Oscar Wilde

(1854 – 1900)

Le Jardin Des Tuileries

This winter air is keen and cold,

And keen and cold this winter sun,

But round my chair the children run

Like little things of dancing gold.

Sometimes about the painted kiosk

The mimic soldiers strut and stride,

Sometimes the blue-eyed brigands hide

In the bleak tangles of the bosk.

And sometimes, while the old nurse cons

Her book, they steal across the square,

And launch their paper navies where

Huge Triton writhes in greenish bronze.

And now in mimic flight they flee,

And now they rush, a boisterous band –

And, tiny hand on tiny hand,

Climb up the black and leafless tree.

Ah! cruel tree! if I were you,

And children climbed me, for their sake

Though it be winter I would break

Into spring blossoms white and blue!

Oscar Wilde

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive W-X, Wilde, Oscar, Wilde, Oscar

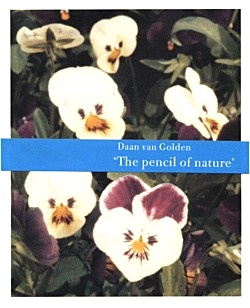

Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen betreurt het overlijden van een van de belangrijkste hedendaagse Nederlandse kunstenaars, de in Rotterdam geboren kunstenaar Daan van Golden (1936 -2017). Zijn kunstwerken roepen de toeschouwer op tot stille overdenking van het alledaagse en het vluchtige karakter van de tijd. Het museum richt nu ter nagedachtenis aan het overlijden van Van Golden (op 9 januari) een tijdelijke presentatie in voor zijn familie en vrienden om waardig afscheid te kunnen nemen van de kunstenaar. Vanaf dinsdag 17 januari tot en met 19 februari 2017 is een kleine selectie uit zijn indrukwekkende oeuvre te zien in de Serra zaal.

Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen betreurt het overlijden van een van de belangrijkste hedendaagse Nederlandse kunstenaars, de in Rotterdam geboren kunstenaar Daan van Golden (1936 -2017). Zijn kunstwerken roepen de toeschouwer op tot stille overdenking van het alledaagse en het vluchtige karakter van de tijd. Het museum richt nu ter nagedachtenis aan het overlijden van Van Golden (op 9 januari) een tijdelijke presentatie in voor zijn familie en vrienden om waardig afscheid te kunnen nemen van de kunstenaar. Vanaf dinsdag 17 januari tot en met 19 februari 2017 is een kleine selectie uit zijn indrukwekkende oeuvre te zien in de Serra zaal.

Directeur Sjarel Ex: ‘Met het overlijden van Daan van Golden verliest de Nederlandse kunst wereld een van zijn meest eigenzinnige kunstenaars, een andersdenkende, vrije en leuke man die altijd de verbinding maakte tussen mooi en aandachtig leven en mooi en aandachtig werken. Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen was meer dan veertig jaar nauw met hem verbonden. Onze gedachten gaan uit naar zijn gezin.’