Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Der weiße Wolf

Ein König ritt jagen in einem großen Walde, darinnen er sich verirrte, und mußte manchen Tag wandern und manche Nacht, fand immer nicht den rechten Weg und mußte Hunger und Durst leiden. Endlich begegnete ihm ein kleines schwarzes Männlein, das fragte der König nach dem rechten Weg. »Ich will dich wohl führen und geleiten«, sagte das Männlein, »aber du mußt mir auch  etwas dafür geben, du mußt mir das geben, was dir aus deinem Hause zuerst entgegen kommt.« Der König war froh und sprach unterwegs: »Du bist recht brav, Männchen; wahrlich und wenn mein bester Hund mir entgegenlief, so wollt ich dir ihn doch gern zum Lohne geben.« Das Männlein aber erwiderte: »Deinen besten Hund, den mag ich nicht, mir ist was andres lieb.« Wie sie nun beim Schlosse ankamen, so sah des Königs jüngste Tochter durchs Fenster ihren Vater geritten kommen und sprang ihm fröhlich entgegen. Da sie ihn aber in ihre Arme schloß, sprach er: »Ei wollt ich doch, daß lieber mein bester Hund mir entgegen gekommen wäre!« Über diese Rede erschrak die Königstochter gar sehr, und weinte und rief: »Wie das, mein Vater? Ist dir dein Hund lieber denn ich, und sollte er dich froher willkommen heißen?« aber der König tröstete sie und sagte: »O liebe Tochter, so war es ja nicht gemeint!« und erzählte ihr alles. Sie aber blieb ganz standhaft und sagte: »Es ist besser so, als daß mein lieber Vater umgekommen wäre im wilden Walde«, und das Männchen sagte: »Nach acht Tagen hole ich dich.«

etwas dafür geben, du mußt mir das geben, was dir aus deinem Hause zuerst entgegen kommt.« Der König war froh und sprach unterwegs: »Du bist recht brav, Männchen; wahrlich und wenn mein bester Hund mir entgegenlief, so wollt ich dir ihn doch gern zum Lohne geben.« Das Männlein aber erwiderte: »Deinen besten Hund, den mag ich nicht, mir ist was andres lieb.« Wie sie nun beim Schlosse ankamen, so sah des Königs jüngste Tochter durchs Fenster ihren Vater geritten kommen und sprang ihm fröhlich entgegen. Da sie ihn aber in ihre Arme schloß, sprach er: »Ei wollt ich doch, daß lieber mein bester Hund mir entgegen gekommen wäre!« Über diese Rede erschrak die Königstochter gar sehr, und weinte und rief: »Wie das, mein Vater? Ist dir dein Hund lieber denn ich, und sollte er dich froher willkommen heißen?« aber der König tröstete sie und sagte: »O liebe Tochter, so war es ja nicht gemeint!« und erzählte ihr alles. Sie aber blieb ganz standhaft und sagte: »Es ist besser so, als daß mein lieber Vater umgekommen wäre im wilden Walde«, und das Männchen sagte: »Nach acht Tagen hole ich dich.«

Und nach acht Tagen richtig, da kam ein weißer Wolf in das Königsschloß, und die Königstochter mußte sich auf seinen Rücken setzen, und heisa, da ging’s durch dick und dünn, bergauf und ab, und die Königstochter konnte das Reiten auf dem Wolf nicht aushalten, und fragte: »Ist’s noch weit?« – »Schweig! Weit weit ist’s noch zum gläsernen Berge – schweigst du nicht, so werf ich dich herunter!« Nun ging es wieder so fort, bis die arme Königstochter wieder zagte und klagte und fragte, ob es noch weit sei? Und da sagte ihr der Wolf die nämlichen drohenden Worte, und rannte immer fort, immer weiter, bis sie zum drittenmale die Frage wagte, da warf er sie auf der Stelle von seinen Rücken herunter und rannte davon.

Nun war die arme Prinzessin ganz allein in dem finstern Walde, und ging und ging und dachte, endlich werde ich doch einmal zu Leuten kommen. Und endlich kam sie an eine Hütte, da brannte ein Feuerchen und da saß ein altes Waldmütterchen, das hatte ein Töpfchen am Feuer. Und da fragte die Königstochter: »Mütterchen, hast du den weißen Wolf nicht gesehen?« – »Nein, da mußt du den Wind fragen, der fragt überall herum, aber bleibe erst noch ein wenig hier, und iß mit mir. Ich koche hier ein Hühnersüppchen.« Das tat die Prinzessin, und als sie gegessen hatten, sagte die Alte: »Nimm die Hühnerknöchelchen mit dir, du wirst sie gut gebrauchen können.« Dann zeigte ihr die Alte den rechten Weg nach dem Winde.

Als die Königstochter bei dem Winde ankam, fand sie ihn auch am Feuer sitzen und sich eine Hühnersuppe kochen, aber auf ihre Frage nach dem weißen Wolf antwortete er ihr: »Liebes Kind, ich habe ihn nicht gesehen, ich bin heute einmal nicht gegangen, und wollte mich einmal hübsch ausruhen. Frage die Sonne, die geht alle Tage auf und unter, aber erst mache es wie ich, ruhe dich aus, und iß mit mir, kannst hernach auch alle die Hühnerknöchlein mit dir nehmen, wirst sie wohl gut brauchen können.«

Als dies geschehen war, ging die Kleine nach der Sonne zu, und es ging da gerade wieder wie beim Winde, die Sonne kochte sich gerade eine Hühnersuppe an sich selbst, daher es damit sehr geschwind ging, hatte auch den weißen Wolf nicht gesehen, und lud  die Prinzessin zum Mitessen ein. »Du mußt den Mond fragen, denn wahrscheinlich läuft der weiße Wolf nur des Nachts, und da sieht der Mond alles.« Als nun die Königstochter mit der Sonne gegessen und die Knöchlein aufgesammelt hatte, ging sie weiter und fragte den Mond. Auch er kochte Hühnersuppe und sagte: »Es ist fatal, ich habe letzt nicht geschienen, oder bin zu spät aufgegangen, ich weiß gar nichts von dem weißen Wolf.« Da weinte das Mädchen und rief: »O Himmel, wen soll ich nun fragen?« – »Nun nur Geduld mein Kind«, sagte der Mond. – »Vor Essen, wird kein Tanz, setze dich und iß erst die Hühnersuppe mit mir und nimm auch die Knöchelchen mit, du wirst sie wohl brauchen. Etwas Neues weiß ich doch; im gläsernen Berge das schwarze Männchen – das hält heute Hochzeit, der Mann im Mond ist auch dazu eingeladen.« – »Ach der gläserne Berg, der gläserne Berg! dahin wollte ich ja eben, dahin hat mich ja der weiße Wolf tragen sollen!« rief die Königstochter. »Nun bis dorthin kann ich dir schon leuchten und den Weg zeigen«, sagte der Mond, »sonst könntest du dich leichtlich irren, denn ich zum Beispiel bestehe ganz und gar aus lauter gläsernen Bergen. Nimm immer deine Knöchlein hübsch alle mit.« Das tat die Prinzessin, aber in der Eile vergaß sie doch ein Knöchlein.

die Prinzessin zum Mitessen ein. »Du mußt den Mond fragen, denn wahrscheinlich läuft der weiße Wolf nur des Nachts, und da sieht der Mond alles.« Als nun die Königstochter mit der Sonne gegessen und die Knöchlein aufgesammelt hatte, ging sie weiter und fragte den Mond. Auch er kochte Hühnersuppe und sagte: »Es ist fatal, ich habe letzt nicht geschienen, oder bin zu spät aufgegangen, ich weiß gar nichts von dem weißen Wolf.« Da weinte das Mädchen und rief: »O Himmel, wen soll ich nun fragen?« – »Nun nur Geduld mein Kind«, sagte der Mond. – »Vor Essen, wird kein Tanz, setze dich und iß erst die Hühnersuppe mit mir und nimm auch die Knöchelchen mit, du wirst sie wohl brauchen. Etwas Neues weiß ich doch; im gläsernen Berge das schwarze Männchen – das hält heute Hochzeit, der Mann im Mond ist auch dazu eingeladen.« – »Ach der gläserne Berg, der gläserne Berg! dahin wollte ich ja eben, dahin hat mich ja der weiße Wolf tragen sollen!« rief die Königstochter. »Nun bis dorthin kann ich dir schon leuchten und den Weg zeigen«, sagte der Mond, »sonst könntest du dich leichtlich irren, denn ich zum Beispiel bestehe ganz und gar aus lauter gläsernen Bergen. Nimm immer deine Knöchlein hübsch alle mit.« Das tat die Prinzessin, aber in der Eile vergaß sie doch ein Knöchlein.

Bald stand sie an dem gläsernen Berge, aber der war ganz glatt und glitschig, da war nicht hinauf zu kommen, aber da nahm die Königstochter alle Hühnerknöchlein von der alten Waldmutter, von dem Wind, von der Sonne und von dem Monde, und machte sich daraus eine Leiter, die wurde sehr lang, aber o weh, zuletzt fehlte noch eine einzige Sprosse, noch ein Glied. Da schnitt sich die Prinzessin das oberste Gelenk von ihrem kleinen Finger ab, und so tat es gut, und sie konnte nun rasch zum Gipfel des gläsernen Berges klimmen. Oben war eine große Öffnung, da führte eine schöne Treppe hinunter, und war alles voll Glanz und Pracht, und war ein Saal da voll Hochzeitgäste und viele Musikanten und reichbesetzte Tafeln. Und da saß das schwarze Männlein und an seiner Seite saß eine Dame, die war seine Braut, das schwarze Männlein aber schien traurig. Und der Königstochter tat es auch so weh, so weh, daß sie nun zu spät kam, und daß das schwarze Männlein so traurig war, und dachte bei sich, ich will ein Lied vom weißen Wolf singen, vielleicht kennt er mich dann – denn er hatte sie noch gar nicht angesehen, folglich auch nicht wieder erkannt. Und da stand eine Harfe an der Wand, welche die Prinzessin gut spielte, die nahm sie nun und sang

»Deinen besten Hund, den mag ich nicht,

Mir ist was andres lieb!

Die jüngste Königstochter.

Der weiße Wolf, der lief davon,

Sie weiß nicht, wo er blieb;

Die jüngste Königstochter.«

Da horchte das schwarze Männlein hoch auf,

aber die Prinzessin fuhr fort zu spielen und zu singen.

»Sie ist dem Wolfe nachgereist,

Schnitt ab ihr Fingerglied,

Die jüngste Königstochter.

Nun ist sie da – du kennst sie nicht,

Traurig singt dir dies Lied

Die jüngste Königstochter.«

Da sprang das schwarze Männlein von seinem Sitze auf und war plötzlich ein ganz schöner junger Prinz und eilte auf sie zu, und schloß sie in seine Arme.

Alles war Zauber gewesen. Der Prinz war in das alte Männlein und in den weißen Wolf und in den gläsernen Berg hinein verzaubert so lange bis eine Prinzessin, um zu ihm zu gelangen, sich’s ein Glied von ihrem kleinen Finger kosten lassen würde, wenn das aber bis zu einer gewissen Zeit nicht geschähe, so müsse er eine andre freien und ein schwarzes Männlein bleiben all sein Leben lang. Nun war der Zauber gelöst, die andre Braut verschwand, der entzauberte Prinz heiratete die Königstochter, reiste darauf mit ihr zu ihrem Vater, der sich herzlich freute, sie wieder zu sehen, und lebten alle glücklich miteinander bis an ihr Ende. Sollte dieses aber nicht erfolgt sein, so ist es einigermaßen wahrscheinlich, daß sie noch heute leben.

Ludwig Bechstein

(1801 – 1860)

Der weiße Wolf

Sämtliche Märchen

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Bechstein, Bechstein, Ludwig

Protestgedicht, 1968

(gevonden in een oud schoolboek van een soixante-huitard)

Ga weg, op uw plaats wil ik zitten.

Va-t’en, gij daar in uw driedelig grijs.

De tijd is rijp voor nieuwe winden.

Wij willen grote auto’s, en een parking

voor onszelf. Want ruimte moet er zijn.

Recht hebben wij daarop, besef dat wel.

Het volk moet alles weten, iedereen toch

evenveel ongeveer. Af willen wij van geloven

in de Werkelijke Tegenwoordigheid, af!

En negers mogen dromen wat ze willen,

maar negers mogen zij niet meer heten.

Ouden-van-dagen bestaan niet meer

en vrouwen moeten kinderen wíllen.

Herenigen zullen wij hier families die

uit hun bergdorpen oma’s willen en net

zo ongeletterde bruiden. Opvoeden zullen

wij het volk vanachter megafoons en vanaf

uitklaphoezen, beschijnen met nieuw licht.

Ga weg, maak onze plaats snel vrij nu.

Wij pardonneren u uw desertie.

Wij vergeven jou jouw deesertsie.

Bert Bevers

Ongepubliceerd

Bert Bevers is a poet and writer who lives and works in Antwerp (Be)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Bevers, Bert

Folded Power

Sorrow can wait,

For there is magic in the calm estate

Of grief; lo, where the dust complies

Wisdom lies.

Sorrow can rest,

Indifferent, with her head upon her breast;

Idle and hushed, guarded from fears;

Content with tears.

Sorrow can bide,

With sealèd lids and hands unoccupied.

Sorrow can fold her latent might,

Dwelling with night.

But Sorrow will rise

From her dream of sombre and hushed eternities.

Lifting a Child, she will softly move

With a mother’s love.

She will softly rise.

Her embrace the dying will recognize,

Lifting them gently through strange delight

To a clearer light.

Gladys Cromwell

(1885-1919)

Folded Power

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Cromwell, Gladys, Gladys Cromwell

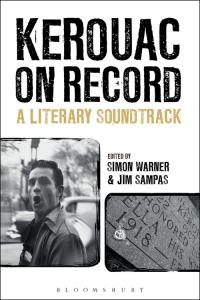

Kerouac on Record.

A Literary Soundtrack

He was the leading light of the Beat Generation writers and the most dynamic author of his time, but Jack Kerouac also had a lifelong passion for music, particularly the mid-century jazz of New York City, the development of which he witnessed first-hand during the 1940s with Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie and Thelonious Monk to the fore.

The novelist, most famous for his 1957 book On the Road, admired the sounds of bebop and attempted to bring something of their original energy to his own writing, a torrent of semi-autobiographical stories he published between 1950 and his early death in 1969. Yet he was also drawn to American popular music of all kinds – from the blues to Broadway ballads – and when he came to record albums under his own name, he married his unique spoken word style with some of the most talented musicians on the scene.

Kerouac’s musical legacy goes well beyond the studio recordings he made himself: his influence infused generations of music makers who followed in his work – from singer-songwriters to rock bands. Some of the greatest transatlantic names – Bob Dylan and the Grateful Dead, Van Morrison and David Bowie, Janis Joplin and Tom Waits, Sonic Youth and Death Cab for Cutie, and many more – credited Kerouac’s impact on their output.

In Kerouac on Record, we consider how the writer brought his passion for jazz to his prose and poetry, his own record releases, the ways his legacy has been sustained by numerous more recent talents, those rock tributes that have kept his memory alive and some of the scores that have featured in Hollywood adaptations of the adventures he brought to the printed page.

Simon Warner is a journalist, lecturer and broadcaster who teaches Popular Music Studies at the University of Leeds in the UK. He has, over a number of years, written live reviews and counterculture obituaries for The Guardian and The Independent, and has a particular interest in the relationship between the Beat Generation writers–Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, William Burroughs and others–and rock culture. His previous books include Rockspeak: The Language of Rock and Pop (1996) and Howl for Now: A Celebration of Allen Ginsberg’s epic protest poem (2005).

Jim Sampas is a music and film producer. His musical works often focuses on major cultural figures such Jack Kerouac (who is his Uncle), The Beatles, Bruce Springsteen, The Smiths, Bob Dylan, and The Rolling Stones. He has persuaded a galaxy of stars to partake of a unique aesthetic marriage, as vintage works are resurrected in contemporary arrangements in projects covered by such major news outlets as People Magazine, NPR, The New York Times, Entertainment Weekly, Rolling Stone, and many others.

Kerouac on Record

A Literary Soundtrack

Editor(s): Simon Warner, Jim Sampas

Hardback £25.20

Paperback £16.19

Published: 2018

Format: Hardback

Extent: 480 p.

ISBN: 9781501323348

Imprint: Bloomsbury Academic

Dimensions: 229 x 152 mm

£28.00

# more books

Jack Kerouac

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: # Music Archive, - Book News, - Book Stories, Archive K-L, Archive K-L, Art & Literature News, AUDIO, CINEMA, RADIO & TV, Bob Dylan, David Bowie, Kerouac, Jack

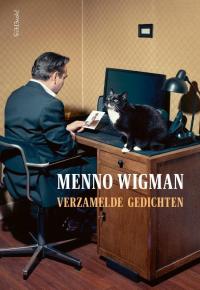

M enno Wigman (1966-2018) was een van de grootste en eigenzinnigste dichters van Nederland.

enno Wigman (1966-2018) was een van de grootste en eigenzinnigste dichters van Nederland.

Zijn stijl werd gekenmerkt door een zwart-romantische toon die, afgewisseld met een weemoedige blik, direct tot de verbeelding sprak. Zijn gedichten waren even toegankelijk als experimenteel, een combinatie van een uitgesproken intensiteit met de beleving van het alledaagse. Wigmans Verzamelde gedichten zijn samengesteld door Neeltje Maria Min en Rob Schouten, zijn goede vrienden en de beste kenners van zijn werk.

Van Menno Wigman (1966-2018) verschenen vijf dichtbundels, een dagboek, een essaybundel en vele vertalingen, bloemlezingen en gelegenheidsuitgaven. Tot de vele prijzen die hij kreeg, behoren de Gedichtendagprijs (2002), de Jan Campert-prijs (2002), de A. Roland Holstprijs (2015) en de Ida Gerhardt Poëzieprijs (2018).

Verzamelde gedichten

Menno Wigman

336 pagina’s

Druk 1

Verschenen 27-09-19

Taal Nederlands

Poëzie

Gebonden

ISBN 9789044641936

Uitgever Prometheus

€ 29,99

# new poetry

menno wigman

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Book Stories, Archive W-X, Archive W-X, Art & Literature News, Wigman, Menno

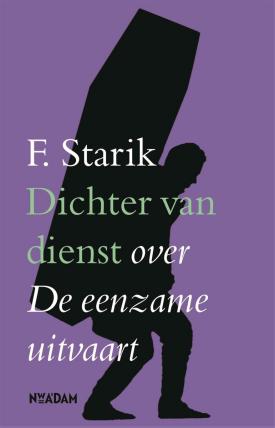

Laatste boek van F. Starik: ‘Dichter van dienst’ over De eenzame uitvaart. Dichter van dienst is het vaarwel van F. Starik, zijn indrukwekkend en aangrijpend laatste boek over eenzame uitvaarten in Amsterdam die hij zestien jaar lang vormgaf.

‘Ik ben De Eenzame Uitvaart in de loop van tijd als een levensopdracht gaan zien, als een Taak die je tot het einde zult vervullen, niet als een project waarmee je na een tijdje weer ophoudt.

‘Ik ben De Eenzame Uitvaart in de loop van tijd als een levensopdracht gaan zien, als een Taak die je tot het einde zult vervullen, niet als een project waarmee je na een tijdje weer ophoudt.

Het recept is eenvoudig en inmiddels bekend: dichters schrijven een gedicht – en dragen dat op de uitvaart voor – voor die mensen, die anders waren overgeschoten, voor wie niemand zou komen, over wie niemand had gesproken, was de dichter er niet geweest om afscheid te nemen, vaarwel te zeggen.’

Het boek: ‘Dichter van dienst’ is het vaarwel van F. Starik (1958-2018), zijn indrukwekkend en aangrijpend laatste boek over eenzame uitvaarten in Amsterdam die hij zestien jaar lang vormgaf.

Met gedichten van o.a. Maria Barnas, Wim Brands, Anneke Brassinga, Eva Gerlach, Erik Jan Harmens, Judith Herzberg, Neeltje Maria Min, Marieke Lucas Rijneveld en Menno Wigman.

F. Starik

Dichter van dienst

over De eenzame uitvaart

Uitgever: Nieuw Amsterdam

Verwacht: November 2019

ISBN 9789046825983

paperback

288 pagina’s

€ 20,99

# new books

F. Starik

Dichter van dienst

over De eenzame uitvaart

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #More Poetry Archives, - Book News, - Book Stories, Archive S-T, Art & Literature News, Brands, Wim, In Memoriam, Rijneveld, Marieke Lucas

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, although renowned for his novels, memoirs, and plays, honed his craft as a short story writer. From “The Fig Tree” (“Mugumo” in this collection), written in 1960, his first year as an undergraduate at Makerere University College in Uganda, to the playful “The Ghost of Michael Jackson,” written as a professor at the University of California, Irvine, these collected stories reveal a master of the short form.

Covering the period of British colonial rule and resistance in Kenya to the bittersweet experience of independence—and including two stories that have never before been published in the United States— Ngũgĩ’s collection features women fighting for their space in a patriarchal society; big men in their Bentleys who have inherited power from the British; and rebels who still embody the fighting spirit of the downtrodden.

Covering the period of British colonial rule and resistance in Kenya to the bittersweet experience of independence—and including two stories that have never before been published in the United States— Ngũgĩ’s collection features women fighting for their space in a patriarchal society; big men in their Bentleys who have inherited power from the British; and rebels who still embody the fighting spirit of the downtrodden.

One of Ngũgĩ’s most beloved stories, “Minutes of Glory,” tells of Beatrice, a sad but ambitious waitress who fantasizes about being feted and lauded over by the middle-class clientele in the city’s beer halls. Her dream leads her on a witty and heartbreaking adventure.

Published for the first time in America, Minutes of Glory and Other Stories is a major literary event that celebrates the storytelling might of one of Africa’s best-loved writers.

Title: Minutes of Glory and Other Stories

Author: Ngugi wa Thiong’o

Publisher: New Press, The

Format Hardcover

224 pages

ISBN-10 1620974657

ISBN-13 9781620974650

Publication Date 01 March 2019

Hardcover – $24.95

# new books

Ngugi wa Thiong’o

Minutes of Glory and Other Stories

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #Short Stories Archive, - Book News, - Book Stories, Archive M-N, Art & Literature News, FDM in Africa

An meine Schwester

Wo du gehst wird Herbst und Abend,

Blaues Wild, das unter Bäumen tönt,

Einsamer Weiher am Abend.

Leise der Flug der Vögel tönt,

Die Schwermut über deinen Augenbogen.

Dein schmales Lächeln tönt.

Gott hat deine Lider verbogen.

Sterne suchen nachts Karfreitagskind

Deinen Stirnenbogen.

Georg Trakl

(1887 – 1914)

An meine Schwester, 1913

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Archive Tombeau de la jeunesse, Archive S-T, Trakl, Georg, Trakl, Georg, WAR & PEACE

Theresa Lola’s debut poetry collection In Search of Equilibrium is an extraordinary, and exacting study of death and grieving. Where the algorithms of the body and the memory fail, Lola finds the words that will piece together the binary code of family and restart the recovery program. In doing so, these unflinching poems work towards the hard-wired truths of life itself – finding hope in survival, lines of rescue in faith, a stubborn equilibrium in the equations of loss and renewal.

“You can call me arrogant, call me black Marilyn,

come celebrate with me,

I am so beautiful death can’t take its eyes off me.”

Theresa Lola’s debut poetry collection In Search of Equilibrium is an extraordinary and exacting study of death and grieving.

Theresa Lola’s debut poetry collection In Search of Equilibrium is an extraordinary and exacting study of death and grieving.

Where the algorithms of the body and the memory fail, Lola finds the words that will piece together the binary code of family and restart the recovery program.

In doing so, these unflinching poems work towards the hard-wired truths of life itself – finding hope in survival, lines of rescue in faith, a stubborn equilibrium in the equations of loss and renewal.

Theresa Lola is a British Nigerian Poet, born 1994. She was joint-winner of the 2018 Brunel International African Poetry Prize and was shortlisted for the 2017 Bridport Poetry Prize. In 2018 she was invited by the Mayor of London’s Office to read at Parliament Square alongside Sadiq Khan and actress Helen McCory at the unveiling of Millicent Fawcett’s statue. She has appeared on BBC Radio 4 Woman’s Hour, and ASOS Magazine with Octavia Collective among others. She is an alumni of the Barbican Young Poets Programme.

In Search of Equilibrium

by Theresa Lola

Poetry

Paperback

80 pages

Publisher: Nine Arches Press

Date: 28th Feburary 2019

Language: English

ISBN-10: 1911027689

ISBN-13: 978-1911027683

Price £9.99

# more poetry

Theresa Lola

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #Editors Choice Archiv, - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive K-L, Archive K-L

Frankfurter Buchmesse is the international publishing industry’s biggest trade fair – with over 7,500 exhibitors from 109 countries, around 285,000 visitors, over 4,000 events and some 10,000 accredited journalists and bloggers in attendance.

It also brings together key players from the fields of technology education, film, games, STM, academic publishing, and business information. Frankfurter Buchmesse organises the participation of publishers at around 20 international book fairs and hosts trade events throughout the year in major international markets. Frankfurter Buchmesse is a subsidiary of the Börsenverein des Deutschen Buchhandels (German Publishers & Booksellers Association).

Norway is 2019 the Guest of Honour of Frankfurter Buchmesse – the land of big Literature: from the classics of Henrik Ibsen to the modern best-sellers of Jo Nesbø.

Frankfurter Buchmesse

16 – 20 Oktober 2019

# More information on website: https://www.buchmesse.de/en

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, - Book News, - Bookstores, Art & Literature News, AUDIO, CINEMA, RADIO & TV, LITERARY MAGAZINES, PRESS & PUBLISHING

Scott Walker and the Song of the One-All-Alone offers, in detailed interpretative commentaries of his best songs, a sustained assessment of the work and career of Scott Walker, one of the most significant and perplexing artists of the late 20th and 21st century.

For Brian Eno, Walker was not only a great composer and a superlative lyricist but also a significant contemporary poet. Marc Almond goes further, ‘an absolute musical genius, existential and intellectual and a star right from the days of The Walker Brothers’. As Almond suggests, Walker’s work is marked by a continual engagement with existentialist philosophy informing his approach to art, politics and life. In particular, the device of the solitary figure or ‘one-all-alone’ evoked in his songs provides the basis for his lyrical exploration of the singularity of existence – in all its darkness as well as light.

For Brian Eno, Walker was not only a great composer and a superlative lyricist but also a significant contemporary poet. Marc Almond goes further, ‘an absolute musical genius, existential and intellectual and a star right from the days of The Walker Brothers’. As Almond suggests, Walker’s work is marked by a continual engagement with existentialist philosophy informing his approach to art, politics and life. In particular, the device of the solitary figure or ‘one-all-alone’ evoked in his songs provides the basis for his lyrical exploration of the singularity of existence – in all its darkness as well as light.

Through following his own path, Walker arrived at a unique sound according to his own method that produced a genuinely new form of song. Looking closely at these songs, this book also considers the wider political implications of his approach in its rejection of external authorities and common or consensual ideals.

Scott Wilson is Professor of Media and Psychoanalysis at Kingston University, London, UK. He is the author of Stop Making Sense: Music from the Perspective of the Real (Karnac, 2015) and the editor of Melancology: Black Metal Theory and Ecology (Zone Books, 2014).

Scott Walker and the Song of the One-All-Alone

By: Scott Wilson

Published: 03-10-2019

Format: Paperback

Edition: 1st

Extent: 232 pg

ISBN: 9781501332555

Imprint: Bloomsbury Academic

Series: EX:CENTRICS

Dimensions: 216 x 140 mm

RRP: £22.99

# more music books

Scott Walker

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Book Stories, Art & Literature News, AUDIO, CINEMA, RADIO & TV, Scott Walker

De Scheffer 2019 is gewonnen door kunstenaar Susanna Inglada (Spanje, 1983). De Scheffer is een tweejaarlijkse aanmoedigingsprijs van de Vereniging Dordrechts Museum (VDM) voor jonge beeldend kunstenaars. De prijs bestaat uit de aankoop van een werk en een expositie in het Dordrechts Museum.

Susanna Inglada wist de jury te overtuigen met haar zeggingskracht, vernieuwingsdrang en de sociale en politieke relevantie van haar werk. Haar werk is vanaf 16 november te bewonderen in het Dordrechts Museum.

De Schefferprijs wordt mogelijk gemaakt door het Schefferfonds dat dankzij legaten van de kunstenaar Ary Scheffer (Dordrecht 1795 – Argenteuil 1858) en zijn familie kon worden opgericht. De Vereniging Dordrechts Museum geeft invulling aan hun wens om jonge talentvolle kunstenaars te ondersteunen. De prijs werd eerder toegekend aan Frank Ammerlaan (2013), Joost Krijnen (2015) en in 2017 aan Raquel van Haver.

De Schefferprijs wordt mogelijk gemaakt door het Schefferfonds dat dankzij legaten van de kunstenaar Ary Scheffer (Dordrecht 1795 – Argenteuil 1858) en zijn familie kon worden opgericht. De Vereniging Dordrechts Museum geeft invulling aan hun wens om jonge talentvolle kunstenaars te ondersteunen. De prijs werd eerder toegekend aan Frank Ammerlaan (2013), Joost Krijnen (2015) en in 2017 aan Raquel van Haver.

Susanna Inglada maakt expressieve tekeningen van mensen die in een intense, soms zelfs gewelddadige interactie met elkaar verwikkeld zijn. Geïnspireerd door aspecten van de Spaanse geschiedenis, creëert Inglada theatrale ‘scenes’ waarin bovendien verschillende verwijzingen naar de schilderkunst te vinden zijn.

Inglada volgde een theateropleiding in Barcelona voor ze zich toelegde op de beeldende kunst en studies volgde aan de universiteit van Barcelona, het Frank Mohr Instituut in Groningen en het HISK in Gent.

‘Inglada’s werk getuigt van een onderzoekende geest en is gebaseerd op een dramatische verteltraditie. Haar werk refereert aan een verleden dat nog altijd actueel is en waarin machtsverhoudingen centraal staan’ aldus het juryrapport. De jury bestond deze editie uit Margriet Schavemaker, artistiek directeur Amsterdam Museum, Judith Spijksma conservator moderne en hedendaagse kunst Dordrechts Museum, Ton Kraayeveld, beeldend kunstenaar en Bea de Visser, beeldend kunstenaar.

Solotentoonstelling Susanna Inglada: Onder de titel De Scheffer 2019 is van 16 november tot 8 maart 2020 een solotentoonstelling van Susanna Inglada te zien. Deze expositie toont werk wat niet eerder in Nederland te zien was. Daarnaast is er nieuw werk te bezichtigen waarin de kunstenaar ingaat op de rol van de vrouw in de schilderkunst.

16 november 2019 tot 8 maart 2020

solotentoonstelling van Susanna Inglada

Museum Dordrecht

Museumstraat 40, Dordrecht

https://www.dordrechtsmuseum.nl/

# Foto: Susanna Inglada in haar atelier. Foto: Milan Rinck

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Art & Literature News, Awards & Prizes, Exhibition Archive, FDM Art Gallery

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature