Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

Anthem for Doomed Youth

What passing-bells for these who die as cattle?

— Only the monstrous anger of the guns.

Only the stuttering rifles’ rapid rattle

Can patter out their hasty orisons.

No mockeries now for them; no prayers nor bells;

Nor any voice of mourning save the choirs,—

The shrill, demented choirs of wailing shells;

And bugles calling for them from sad shires.

What candles may be held to speed them all?

Not in the hands of boys, but in their eyes

Shall shine the holy glimmers of goodbyes.

The pallor of girls’ brows shall be their pall;

Their flowers the tenderness of patient minds,

And each slow dusk a drawing-down of blinds.

Wilfred Owen

(1893 – 1918)

Anthem for Doomed Youth (Poem)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Archive O-P, Galerie des Morts, Owen, Wilfred, WAR & PEACE

Hij rijdt de winkel in, rechtdoor naar de bloemenhoek die nu op de plek zit waar vroeger de keuken van juffrouw Fijnhout was.

Al een paar dagen na de begrafenis van juffrouw Fijnhout betrok nicht Jozefien, met man en kinderen, het huis.

Al een paar dagen na de begrafenis van juffrouw Fijnhout betrok nicht Jozefien, met man en kinderen, het huis.

Haar man begon direct met het uitbreiden van de winkel. Hij verkocht ook verf en behang, kalk en wasbenzine. En hij had een drukpersje voor geboortekaartjes. En wie geboortekaartjes kocht, kocht ook bloemen. Daarom stond een hoek van de winkel altijd vol kleurige bloemen voor geboortefeesten en een andere hoek vol witte ruikers voor bruiloften en begrafenissen.

Nicht Jozefien vlocht ook grafkransen. Ze had wel wat van haar overleden tante. Voor alles kon men bij haar terecht.

In de loop der jaren is de winkel uitgebreid. Mels komt er nog graag. De geuren van de bloemen doen hem goed. En de kleuren. Hij hoort het druppelen van de fonteintjes. Overal staan ze. Het is mode. Fonteintjes van aardewerk, van hard, gekleurd plastic, van glas. En veel spiegels die het wereldje van de winkel uitvergroten tot een ware tuin. Door al die spiegels lijken er meer meisjes in de winkel te zijn, maar er is alleen Christine, de kleindochter van nicht Jozefien.

`Geef die witte aronskelken maar’, zegt Mels. Hij is een beetje gek op haar, door de manier waarop ze alles doet, bedachtzaam en vanzelfsprekend. Ze weet precies wat mooi is. Een prinses in een koninklijke tuin. Ze is altijd vriendelijk.

`Jammer dat het kerkhof weggaat, hè’, zegt Christine, terwijl ze bezig is met een bloemstuk voor een begrafenis. Ze lijkt als twee druppels water op haar grootmoeder Jozefien. Ze is al de vijfde generatie in de winkel.

`Ik kom er zelf niet meer te liggen’, zegt Mels. `Ik dacht bij mijn vriend Tijger begraven te worden, maar als het zover is, brengen ze me naar een plek waar ik nu al niet meer op eigen kracht kan komen.’

`Hoelang is uw vriend al dood?’

`Al bijna vijftig jaar. Hem laten ze gewoon liggen. De huizen worden gewoon op de resterende graven gebouwd.’

`Ik zou daar niet willen wonen.’

`Tijger kan er wel om lachen’, zegt Mels.

Christine pakt de aronskelken in en legt ze op zijn schoot. Ze zijn wit en ruiken naar vanille.

Hij ziet zichzelf in de spiegel naast de kassa. Vanaf zijn borst. De bloemen op zijn schoot verbergen zijn onderlijf. Hij ziet er goed uit, met die bloemen op schoot. Bloemen houden van hem. Ze maken hem mooier. Daarom geeft hij ze aan Tijger. Hij weet nog wat zijn moeder zei: je moet altijd de dingen geven waarvan je het meest houdt.

Mels betaalt. De kassa rinkelt. Het is een geluid dat in een winkel hoort.

`Ik voel me hier nog steeds net zo thuis als toen het de kleine winkel van juffrouw Fijnhout was.’

`Juffrouw Fijnhout?’

`De oudtante van je grootmoeder.’

`O, die. Ze had geen kinderen, hè?’

`Jouw grootmoeder leek ook op haar. Net als jouw moeder op haar lijkt. En jij op allemaal.’

`Was ze knap?’

`Wil je weten of jij knap bent?’

`Zeg maar niets’, lacht ze.

`Ja, ze was knap. Maar dat besefte ik later pas. Een kind ziet zoiets niet. Maar ik kwam graag bij haar. Dat is wat telt. Of jij knap bent, laat ik over aan de jongemannen.’

`Bonnetje?’

`Welnee’, zegt hij, overmoedig door de bloemen op zijn schoot. `Geef mij maar een kus.’

Ze kijkt hem lachend aan en geeft hem dan een kus op zijn wang.

`Ik hoop dat er ook nog iemand aan mij denkt als ík al vijftig jaar dood ben’, zegt ze.

`Vast wel’, lacht Mels. `Ik gun je veel kleinkinderen.’

Hij rijdt de winkel uit en kijkt nog een keer om. Hij ziet Christine in drie spiegels tegelijk. Van voor en van achter en van opzij. Alle Christines zijn even mooi.

Hij rijdt door naar het kerkhof en stopt bij het graf van grootvader Rudolf. Hij haalt een bloem uit het boeket en legt die bij het kruis waaronder grootvader Rudolf is begraven, boven op zijn veel eerder gestorven vrouw.

`Rudolphus Johannes Cremers’, leest hij hardop. `Voormalig hoofd der school.’ En daarboven staat: `Katelijne Melanie Jansen’, `huisvrouw’. De kruisjes geven aan dat grootmoeder Katelijne in 1944 is overleden en grootvader Rudolf in 1978. Hij is, geboren in 1882, bijna honderd geworden. Grootmoeder Katelijne is geboren in 1906. Ze was dus achttien jaar jonger en pas achtendertig toen ze stierf. Van horen zeggen weet hij dat ze pianospeelde op familiefeestjes.

Wat doen ze nu met hen? Wordt grootvader naar het nieuwe kerkhof verhuisd en blijft grootmoeder hier achter omdat ze hier al meer dan veertig jaar ligt?

Op elk graf van een familielid legt hij een bloem.

Hij rijdt een rondje. Een deel van de graven is al weg. Door al die lege plekken, ziet het er rommelig uit.

Het graf van Tijger ligt tussen de kindergraven. De meeste opschriften op de kinderkruisen zijn onleesbaar geworden. Ook dat van Tijger is afgebladderd. Van zijn voornaam is alleen een a over, maar het kan ook een o zijn. Hij is een vergeten kind. Wie geen nageslacht heeft, houdt op te bestaan.

Hij legt de bloemen op het graf.

`Dank je.’ Het is de stem van Tijger. Elke keer als hij bloemen op het graf legt, hoort hij hem. Het kan natuurlijk niet, maar toch.

Hij klopt het stuifmeel van zijn jas.

In de eerste maanden na zijn dood brachten Thija en hij vaak boeketten naar het graf. Bloemen die ze langs de Wijer hadden geplukt. Distels, lelies, judaspenningen, alles wat er in het wild groeide.

Vroeger, met de schoolklas, hebben ze vaak het kerkhof geharkt, het onkruid gewied, het mos van de stenen gekrast. Er was hun respect bijgebracht voor het kerkhof. De plek van de voorouders, die altijd zo hoorde te blijven.

Het graf van vliegenier John Wilkington, dat altijd door Mels’ moeder werd onderhouden, is allang weg. Het houten kruis, waarvan de verf verdwenen is, staat in een hoekje van het kerkhof te wachten op mensen die zich het lot van John Wilkington willen aantrekken en de geschiedenis aan hem levend willen houden, maar Mels is een van de weinigen die nog weten wie John Wilkington was. En hij is niet meer in staat het kruis op te knappen om John de eer te geven die hem toekomt.

Bij de poort van het kerkhof staat het beeld van Christoffel met Jezus op zijn schouder. Half tussen de struiken. Langgeleden is het bij de grote kerkbrand van de toren gevallen. Christoffel is een deel van zijn hoofd kwijtgeraakt en mist ook zijn voeten. Jezus heeft de arm verloren die hij om Christoffels schouder had geslagen. Na de restauratie van de kerk is het beeld niet teruggeplaatst op de toren maar vervangen door een haan. Het gehavende beeld is in de tuin gezet en vergeten. Het is een verkeerde plek. Christoffel met op zijn schouder het kind dat over het water wil worden gedragen, had langs de Wijer moeten staan.

De brand van de kerk was de grootste ramp die het dorp ooit getroffen had.

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (094)

wordt vervolgd

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

Guerre civile

La foule était tragique et terrible ; on criait :

À mort ! Autour d’un homme altier, point inquiet,

Grave, et qui paraissait lui-même inexorable,

Le peuple se pressait : À mort le misérable !

Et lui, semblait trouver toute simple la mort.

La partie est perdue, on n’est pas le plus fort,

On meurt, soit. Au milieu de la foule accourue,

Les vainqueurs le traînaient de chez lui dans la rue.

— À mort l’homme ! — On l’avait saisi dans son logis ;

Ses vêtements étaient de carnage rougis ;

Cet homme était de ceux qui font l’aveugle guerre

Des rois contre le peuple, et ne distinguent guère

Scévola de Brutus, ni Barbès de Blanqui ;

Il avait tout le jour tué n’importe qui ;

Incapable de craindre, incapable d’absoudre,

Il marchait, laissant voir ses mains noires de poudre ;

Une femme le prit au collet : « À genoux !

C’est un sergent de ville. Il a tiré sur nous !

— C’est vrai, dit l’homme. — À bas ! à mort ! qu’on le fusille !

Dit le peuple. — Ici ! Non ! Plus loin ! À la Bastille !

À l’arsenal ! Allons ! Viens ! Marche ! — Où vous voudrez »,

Dit le prisonnier. Tous, hagards, les rangs serrés,

Chargèrent leurs fusils. « Mort au sergent de ville !

Tuons-le comme un loup ! — Et l’homme dit, tranquille :

— C’est bien, je suis le loup, mais vous êtes les chiens.

— Il nous insulte ! À mort ! » Les pâles citoyens

Croisaient leurs poings crispés sur le captif farouche ;

L’ombre était sur son front et le fiel dans sa bouche ;

Cent voix criaient : « À mort ! À bas ! Plus d’empereur ! »

On voyait dans ses yeux un reste de fureur

Remuer vaguement comme une hydre échouée ;

Il marchait poursuivi par l’énorme huée,

Et, calme, il enjambait, plein d’un superbe ennui,

Des cadavres gisants, peut-être faits par lui.

Le peuple est effrayant lorsqu’il devient tempête ;

L’homme sous plus d’affronts levait plus haut la tête ;

Il était plus que pris, il était envahi.

Dieu ! comme il haïssait ! comme il était haï !

Comme il les eût, vainqueur, fusillés tous ! « Qu’il meure !

Il nous criblait encor de balles tout à l’heure !

À bas cet espion, ce traître, ce maudit !

À mort ! c’est un brigand ! » Soudain on entendit

Une petite voix qui disait : « C’est mon père ! »

Et quelque chose fit l’effet d’une lumière.

Un enfant apparut. Un enfant de six ans.

Ses deux bras se dressaient suppliants, menaçants.

Tous criaient : « Fusillez le mouchard ! Qu’on l’assomme ! »

Et l’enfant se jeta dans les jambes de l’homme,

Et dit, ayant au front le rayon baptismal :

« Père, je ne veux pas qu’on te fasse de mal ! »

Et cet enfant sortait de la même demeure.

Les clameurs grossissaient : « À bas l’homme ! Qu’il meure !

À bas ! finissons-en avec cet assassin !

Mort ! » Au loin le canon répondait au tocsin.

Toute la rue était pleine d’hommes sinistres.

À bas les rois ! À bas les prêtres, les ministres,

Les mouchards ! Tuons tout ! c’est un tas de bandits ! »

Et l’enfant leur cria : « Mais puisque je vous dis

Que c’est mon père ! — Il est joli, dit une femme,

Bel enfant ! » On voyait dans ses yeux bleus une âme ;

Il était tout en pleurs, pâle, point mal vêtu.

Une autre femme dit : « Petit, quel âge as-tu ?

Et l’enfant répondit : — Ne tuez pas mon père ! »

Quelques regards pensifs étaient fixés à terre,

Les poings ne tenaient plus l’homme si durement.

Un de plus furieux, entre tous inclément,

Dit à l’enfant : « Va-t’en ! — Où ? — Chez toi. — Pourquoi faire ?

— Chez ta mère. — Sa mère est morte, dit le père.

— Il n’a donc plus que vous ? — Qu’est-ce que cela fait ? »

Dit le vaincu. Stoïque et calme, il réchauffait

Les deux petites mains dans sa rude poitrine,

Et disait à l’enfant : « Tu sais bien, Catherine ?

— Notre voisine ? — Oui. Va chez elle. — Avec toi ?

— J’irai plus tard. — Sans toi je ne veux pas. — Pourquoi ?

— Parce qu’on te ferait du mal. » Alors le père

Parla tout bas au chef de cette sombre guerre :

« Lâchez-moi le collet. Prenez-moi par la main,

Doucement. Je vais dire à l’enfant : À demain !

Vous me fusillerez au détour de la rue,

Ailleurs, où vous voudrez. — Et, d’une voix bourrue :

— Soit, dit le chef, lâchant le captif à moitié.

Le père dit : — Tu vois. C’est de bonne amitié.

Je me promène avec ces messieurs. Sois bien sage,

Rentre. » Et l’enfant tendit au père son visage,

Et s’en alla content, rassuré, sans effroi.

« Nous sommes à notre aise à présent, tuez-moi,

Dit le père aux vainqueurs ; où voulez-vous que j’aille ? »

Alors, dans cette foule où grondait la bataille,

On entendit passer un immense frisson,

Et le peuple cria : « Rentre dans ta maison ! »

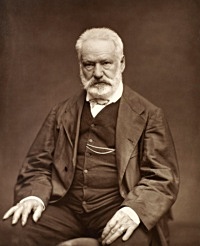

Victor Hugo

(1802-1885)

Guerre civile

(Poème)

La Légende des siècles, 1877

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Archive G-H, Hugo, Victor, Victor Hugo

2019 Jubileumjaar Lustwarande

26 mei – 20 oktober

In 2019 jubileert Lustwarande. Delirious is de tiende expositie in park De Oude Warande.

Ook paviljoen Grotto, door Callum Morton voor De Oude Warande ontworpen, bestaat tien jaar.

Lustwarande start het seizoen op 26 mei met de eerste van twee edities van Brief Encounters ’19.

2019 Jubileumjaar Lustwarande

Delirious

15 juni – 20 oktober

Delirious presenteert een overzicht van recente ontwikkelingen en focust op materialiteit, de huid van hedendaagse sculptuur.

Met nieuw werk van zesentwintig kunstenaars, onder wie Isabelle Andriessen (NL) – Steven Claydon (UK) – Claudia Comte (CH) – Hadrien Gerenton (FR) – Camille Henrot (FR) – Nicholas Hlobo (SA) – Saskia Noor van Imhoff (NL) – Esther Kläs (DE) – Sarah Lucas (UK) – Justin Matherly (US) – Bettina Pousttchi (DE) – Magali Reus (NL) – Bojan Šarčević (RS) – Filip Vervaet (BE)

curatoren: Chris Driessen & David Jablonowski

2019 Jubileumjaar Lustwarande

Brief Encounters ‘19

26 mei & 8 september

Op 26 mei presenteert Lustwarande de eerste editie van Brief Encounters van dit jaar, met nieuwe performances van Melanie Bonajo (NL), William Hunt (UK) en Grace Schwindt (DE).

Op 26 mei presenteert Lustwarande de eerste editie van Brief Encounters van dit jaar, met nieuwe performances van Melanie Bonajo (NL), William Hunt (UK) en Grace Schwindt (DE).

Het programma wordt begin mei bekend gemaakt.

Op 8 september vindt de tweede editie plaats, met onder andere nieuw werk van Gosie Vervloessem (BE).

curatoren: Chris Driessen & Lucette ter Borg

Locatie: Lustwarande – park De Oude Warande, Tilburg

# meer info op website fundament/lustwarande

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Art & Literature News, Art Criticism, Exhibition Archive, FDM Art Gallery, Fundament - Lustwarande, Natural history, Performing arts, Sculpture

Livre Paris

Salon du Livre de Paris

Porte de Versailles – Paris

15-18 Mars 2019

Literary event of the year

165 000 visitors

3 900 authors

250 conferences and debates

688 school groups

391 stands and 515 brands

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, - Book News, - Bookstores, Art & Literature News, AUDIO, CINEMA, RADIO & TV, FDM in Paris, Literary Events

Totentanz 1916

So sterben wir, so sterben wir

Und sterben alle Tage,

Weil es so gemütlich sich sterben lässt.

Morgens noch in Schlaf und Traum,

Mittags schon dahin,

Abends schon zu unterst im Grabe drin.

Die Schlacht ist unser Freudenhaus,

Von Blut ist unsre Sonne,

Tod ist unser Zeichen und Losungswort.

Kind und Weib verlassen wir:

Was gehen sie uns an!

Wenn man sich auf uns nur verlassen kann!

So morden wir, so morden wir

Und morden alle Tage

Unsere Kameraden im Totentanz.

Bruder, reck Dich auf vor mir!

Bruder, Deine Brust!

Bruder, der Du fallen und sterben musst.

Wir murren nicht, wir knurren nicht,

Wir schweigen alle Tage

Bis sich vom Gelenke das Hüftbein dreht.

Hart ist unsre Lagerstatt,

Trocken unser Brot,

Blutig und besudelt der liebe Gott.

Wir danken Dir, wir danken Dir,

Herr Kaiser für die Gnade,

Dass Du uns zum Sterben erkoren hast.

Schlafe Du, schlaf sanft und still,

Bis Dich auferweckt

Unser armer Leib, den der Rasen deckt.

Hugo Ball

(1886-1927)

Totentanz 1916

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Ball, Hugo, Dada, DADA, Dadaïsme

There be none of Beauty’s daughters

Stanzas for Music

There be none of Beauty’s daughters

With a magic like Thee;

And like music on the waters

Is thy sweet voice to me:

When, as if its sound were causing

The charméd ocean’s pausing,

The waves lie still and gleaming,

And the lull’d winds seem dreaming:

And the midnight moon is weaving

Her bright chain o’er the deep,

Whose breast is gently heaving

As an infant’s asleep:

So the spirit bows before thee

To listen and adore thee;

With a full but soft emotion,

Like the swell of Summer’s ocean.

George Gordon Byron

(1788 – 1824)

There be none of Beauty’s daughters

Stanzas for Music

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: # Music Archive, Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Byron, Lord

Als Mels door de achterdeur binnenkomt hoort hij het direct: het is te stil.

Op zijn tenen loopt hij naar de keuken. Juffrouw Fijnhout zit aan tafel, met haar hoofd op haar armen.

Het is zes uur, tijd om de klok op te winden. Is ze het vergeten? Is ze er te moe voor?

Hij gaat tegenover haar zitten en kijkt naar haar witte haar. De ene helft van haar gezicht. Haar ogen zijn dicht.

Hij gaat tegenover haar zitten en kijkt naar haar witte haar. De ene helft van haar gezicht. Haar ogen zijn dicht.

Nu pas valt hem de vreemde lucht op. Hij ziet het plasje onder haar stoel.

Kalm gaat hij naar huis.

`Er is iets met juffrouw Fijnhout’, zegt hij tegen zijn moeder.

`Ze is dood’, zegt ze. `Dat zie ik aan je gezicht.’ Ze slaat een kruis. `Dat de Here zich over haar moge ontfermen. Ze heeft een mooie plek in de hemel verdiend. Amen.’

`Ze hield van haar winkel. Denk jij dat ze in de hemel een winkeltje begint?’

`Maar of ze daar ook Hohner-muziekinstrumenten hebben? Haal je tante. We moeten juffrouw Fijnhout gaan verzorgen. En waarschuw de dokter. Ze is niet dood voordat hij het zegt.’

Mels rent naar zijn tante en brengt haar het nieuws. Nog geen vijf minuten later weet iedereen in de buurt over de dood van juffrouw Fijnhout, die zonder veel pijn is overleden. De mensen zijn tevreden. Ze heeft een zachte dood verdiend.

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (093)

wordt vervolgd

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

Bachten de Kupe

Je kunt wel putten in de aarde vloeken

omdat gebeden schaars zijn en schuren

als zand, maar beter is het trots te zijn

omdat je ergens gebleven bent. Waar je

dolend wakker kunt worden uit gemelijk

genot, geschaakte dromen, verzakende

grenzen. Waar je een vogel van vele lentes

herkent als jezelf. Toen ik ontwaakte wist

ik loepzuiver weer hoe gisteren voor me

een meisje huppelend riep: “Een olm is

een iep! Een olm is een iep! Een olm is

een iep!” Het is hier niet druk, maar kijk:

hier loopt niet ieder in zijn eigen ochtend.

Bert Bevers

Gedicht: Bachten de Kupe

Verschenen in Ballustrada, Terneuzen, 2012

Bert Bevers is a poet and writer who lives and works in Antwerp (Be)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Bevers, Bert

Counting Her Dresses

A Play

Part I.

ACT I.

When they did not see me.

I saw them again.

I did not like it.

ACT II.

I count her dresses again.

ACT III.

Can you draw a dress.

ACT IV.

In a minute.

Part II.

ACT I.

Believe in your mistake.

ACT II.

Act quickly.

ACT III.

Do not mind the tooth.

ACT IV.

Do not be careless.

Part III.

ACT I.

I am careful.

ACT II.

Yes you are.

ACT III.

And obedient.

ACT IV.

Yes you are.

ACT V.

And industrious.

ACT VI.

Certainly.

Part IV.

ACT I.

Come to sing and sit.

ACT II.

Repeat it.

ACT III.

I repeat it.

Part V.

ACT I.

Can you speak quickly.

ACT II.

Can you cough.

ACT III.

Remember me to him.

ACT IV.

Remember that I want a cloak.

Part VI.

ACT I.

I know what I want to say. How do you do I forgive you everything and there is nothing to forgive.

Part VII.

ACT I.

The dog. You mean pale.

ACT II.

No we want dark brown.

ACT III.

I am tired of blue.

Part VIII.

ACT I.

Shall I wear my blue.

ACT II.

Do.

Part IX.

ACT I.

Thank you for the cow.

Thank you for the cow.

ACT II.

Thank you very much.

Part X.

ACT I.

Collecting her dresses.

ACT II.

Shall you be annoyed.

ACT III.

Not at all.

Part XI.

ACT I.

Can you be thankful.

ACT II.

For what.

ACT III.

For me.

Part XII.

ACT I.

I do not like this table.

ACT II.

I can understand that.

ACT III.

A feather.

ACT IV.

It weighs more than a feather.

Part XIII.

ACT I.

It is not tiring to count dresses.

Part XIV.

ACT I.

What is your belief.

Part XV.

ACT I.

In exchange for a table.

ACT II.

In exchange for or on a table.

ACT III.

We were satisfied.

Part XVI.

ACT I.

Can you say you like negro sculpture.

Part XVII.

ACT I.

The meaning of windows is air.

ACT II.

And a door.

ACT III.

A door should be closed.

Part XVIII.

ACT I.

Can you manage it.

ACT II.

You mean dresses.

ACT III.

Do I mean dresses.

Part XIX.

ACT I.

I mean one two three.

Part XX.

ACT I.

Can you spell quickly.

ACT II.

I can spell very quickly.

ACT III.

So can my sister-in-law.

ACT IV.

Can she.

Part XXI.

ACT I.

Have you any way of sitting.

ACT II.

You mean comfortably.

ACT III.

Naturally.

ACT IV.

I understand you.

Part XXII.

ACT I.

Are you afraid.

ACT II.

I am not any more afraid of water than they are.

ACT III.

Do not be insolent.

Part XXIII.

ACT I.

We need clothes.

ACT II.

And wool.

ACT III.

And gloves.

ACT IV.

And waterproofs.

Part XXIV.

ACT I.

Can you laugh at me.

ACT II.

And then say.

ACT III.

Married.

ACT IV.

Yes.

Part XXV.

ACT I.

Do you remember how he looked at clothes.

ACT II.

Do you remember what he said about wishing.

ACT III.

Do you remember all about it.

Part XXVI.

ACT I.

Oh yes.

ACT II.

You are stimulated.

ACT III.

And amused.

ACT IV.

We are.

Part XXVII.

ACT I.

What can I say that I am fond of.

ACT II.

I can see plenty of instances.

ACT III.

Can you.

Part XXVIII.

ACT I.

For that we will make an arrangement.

ACT II.

You mean some drawings.

ACT III.

Do I talk of art.

ACT IV.

All numbers are beautiful to me.

Part XXIX.

ACT I.

Of course they are.

ACT II.

Thursday.

ACT III.

We hope for Thursday.

ACT IV.

So do we.

Part XXX.

ACT I.

Was she angry.

ACT II.

Whom do you mean was she angry.

ACT III.

Was she angry with you.

Part XXXI.

ACT I.

Reflect more.

ACT II.

I do want a garden.

ACT III.

Do you.

ACT IV.

And clothes.

ACT V.

I do not mention clothes.

ACT VI.

No you didn’t but I do.

ACT VII.

Yes I know that.

Part XXXII.

ACT I.

He is tiring.

ACT II.

He is not tiring.

ACT III.

No indeed.

ACT IV.

I can count them.

ACT V.

You do not misunderstand me.

ACT VI.

I misunderstand no one.

Part XXXIII.

ACT I.

Can you explain my wishes.

ACT II.

In the morning.

ACT III.

To me.

ACT IV.

Yes in there.

ACT V.

Then you do not explain.

ACT VI.

I do not press for an answer.

Part XXXIV.

ACT I.

Can you expect her today.

ACT II.

We saw a dress.

ACT III.

We saw a man.

ACT IV.

Sarcasm.

Part XXXV.

ACT I.

We can be proud of tomorrow.

ACT II.

And the vests.

ACT III.

And the doors.

ACT IV.

I always remember the roads.

Part XXXVI.

ACT I.

Can you speak English.

ACT II.

In London.

ACT III.

And here.

ACT IV.

With me.

Part XXXVII.

ACT I.

Count her dresses.

ACT II.

Collect her dresses.

ACT III.

Clean her dresses.

ACT IV.

Have the system.

Part XXXVIII.

ACT I.

She polished the table.

ACT II.

Count her dresses again.

ACT III.

When can you come.

ACT IV.

When can you come.

Part XXXIX.

ACT I.

Breathe for me.

ACT II.

I can say that.

ACT III.

It isn’t funny.

ACT IV.

In the meantime.

Part XL.

ACT I.

Can you say.

ACT II.

What.

ACT III.

We have been told.

ACT IV.

Oh read that.

Part XLI.

ACT I.

I do not understand this home-coming.

ACT II.

In the evening.

ACT III.

Naturally.

ACT IV.

We have decided.

ACT V.

Indeed.

ACT VI.

If you wish.

Gertrude Stein

(1874-1946)

Counting Her Dresses.

A Play

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Archive S-T, Gertrude Stein, Stein, Gertrude, THEATRE

Les innocents

Mais les enfants sont là. Le murmure qui sort

De ces âmes en fleur est-il compris du sort ?

L’enfant va devant lui gaîment ; mais la prière,

Quand il rit, parle-t-elle à quelqu’un en arrière ?

Le frais chuchotement du doux être enfantin

Attendrit-il l’oreille obscure du destin ?

Oh ! que d’ombre ! Tous deux chantent, fragiles têtes

Où flotte la lueur d’on ne sait quelles fêtes,

Et que dore un reflet d’un paradis lointain !

Les enfants ont des coeurs faits comme le matin

Ils ont une innocence étonnée et joyeuse ;

Et pas plus que l’oiseau gazouillant sous l’yeuse,

Pas plus que l’astre éclos sur les noirs horizons,

Ils ne sont inquiets de ce que nous faisons,

Ayant pour toute affaire et pour toute aventure

L’épanouissement de la grande nature ;

Ils ne demandent rien à Dieu que son soleil ;

Ils sont contents pourvu qu’un beau rayon vermeil

Chauffe les petits doigts de leur main diaphane

Et que le ciel soit bleu, cela suffit à Jeanne.

Victor Hugo

(1802-1885)

Les innocents

(Poème)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Archive G-H, Hugo, Victor, Victor Hugo

The She-Wolf

Leonard Bilsiter was one of those people who have failed to find this world attractive or interesting, and who have sought compensation in an “unseen world” of their own experience or imagination — or invention.

Children do that sort of thing successfully, but children are content to convince themselves, and do not vulgarise their beliefs by trying to convince other people. Leonard Bilsiter’s beliefs were for “the few,” that is to say, anyone who would listen to him.

His dabblings in the unseen might not have carried him beyond the customary platitudes of the drawing-room visionary if accident had not reinforced his stock-intrade of mystical lore. In company with a friend, who was interested in a Ural mining concern, he had made a trip across Eastern Europe at a moment when the great Russian railway strike was developing from a threat to a reality; its outbreak caught him on the return journey, somewhere on the further side of Perm, and it was while waiting for a couple of days at a wayside station in a state of suspended locomotion that he made the acquaintance of a dealer in harness and metalware, who profitably whiled away the tedium of the long halt by initiating his English travelling companion in a fragmentary system of folk-lore that he had picked up from Trans–Baikal traders and natives.

His dabblings in the unseen might not have carried him beyond the customary platitudes of the drawing-room visionary if accident had not reinforced his stock-intrade of mystical lore. In company with a friend, who was interested in a Ural mining concern, he had made a trip across Eastern Europe at a moment when the great Russian railway strike was developing from a threat to a reality; its outbreak caught him on the return journey, somewhere on the further side of Perm, and it was while waiting for a couple of days at a wayside station in a state of suspended locomotion that he made the acquaintance of a dealer in harness and metalware, who profitably whiled away the tedium of the long halt by initiating his English travelling companion in a fragmentary system of folk-lore that he had picked up from Trans–Baikal traders and natives.

Leonard returned to his home circle garrulous about his Russian strike experiences, but oppressively reticent about certain dark mysteries, which he alluded to under the resounding title of Siberian Magic. The reticence wore off in a week or two under the influence of an entire lack of general curiosity, and Leonard began to make more detailed allusions to the enormous powers which this new esoteric force, to use his own description of it, conferred on the initiated few who knew how to wield it. His aunt, Cecilia Hoops, who loved sensation perhaps rather better than she loved the truth, gave him as clamorous an advertisement as anyone could wish for by retailing an account of how he had turned a vegetable marrow into a wood pigeon before her very eyes. As a manifestation of the possession of supernatural powers, the story was discounted in some quarters by the respect accorded to Mrs. Hoops’ powers of imagination.

However divided opinion might be on the question of Leonard’s status as a wonderworker or a charlatan, he certainly arrived at Mary Hampton’s house-party with a reputation for preeminence in one or other of those professions, and he was not disposed to shun such publicity as might fall to his share. Esoteric forces and unusual powers figured largely in whatever conversation he or his aunt had a share in, and his own performances, past and potential, were the subject of mysterious hints and dark avowals.

“I wish you would turn me into a wolf, Mr. Bilsiter,” said his hostess at luncheon the day after his arrival.

“My dear Mary,” said Colonel Hampton, “I never knew you had a craving in that direction.”

“A she-wolf, of course,” continued Mrs. Hampton; “it would be too confusing to change one’s sex as well as one’s species at a moment’s notice.”

“I don’t think one should jest on these subjects,” said Leonard.

“I’m not jesting, I’m quite serious, I assure you. Only don’t do it today; we have only eight available bridge players, and it would break up one of our tables. To-morrow we shall be a larger party. To-morrow night, after dinner —”

“In our present imperfect understanding of these hidden forces I think one should approach them with humbleness rather than mockery,” observed Leonard, with such severity that the subject was forthwith dropped.

Clovis Sangrail had sat unusually silent during the discussion on the possibilities of Siberian Magic; after lunch he side-tracked Lord Pabham into the comparative seclusion of the billiard-room and delivered himself of a searching question.

“Have you such a thing as a she-wolf in your collection of wild animals? A she-wolf of moderately good temper?”

Lord Pabham considered. “There is Loiusa,” he said, “a rather fine specimen of the timber-wolf. I got her two years ago in exchange for some Arctic foxes. Most of my animals get to be fairly tame before they’ve been with me very long; I think I can say Louisa has an angelic temper, as she-wolves go. Why do you ask?”

“I was wondering whether you would lend her to me for tomorrow night,” said Clovis, with the careless solicitude of one who borrows a collar stud or a tennis racquet.

“To-morrow night?”

“Yes, wolves are nocturnal animals, so the late hours won’t hurt her,” said Clovis, with the air of one who has taken everything into consideration; “one of your men could bring her over from Pabham Park after dusk, and with a little help he ought to be able to smuggle her into the conservatory at the same moment that Mary Hampton makes an unobtrusive exit.”

Lord Pabham stared at Clovis for a moment in pardonable bewilderment; then his face broke into a wrinkled network of laughter.

“Oh, that’s your game, is it? You are going to do a little Siberian Magic on your own account. And is Mrs. Hampton willing to be a fellow-conspirator?”

“Mary is pledged to see me through with it, if you will guarantee Louisa’s temper.”

“I’ll answer for Louisa,” said Lord Pabham.

By the following day the house-party had swollen to larger proportions, and Bilsiter’s instinct for self-advertisement expanded duly under the stimulant of an increased audience. At dinner that evening he held forth at length on the subject of unseen forces and untested powers, and his flow of impressive eloquence continued unabated while coffee was being served in the drawing-room preparatory to a general migration to the card-room.

His aunt ensured a respectful hearing for his utterances, but her sensation-loving soul hankered after something more dramatic than mere vocal demonstration.

“Won’t you do something to convince them of your powers, Leonard?” she pleaded; “change something into another shape. He can, you know, if he only chooses to,” she informed the company.

“Oh, do,” said Mavis Pellington earnestly, and her request was echoed by nearly everyone present. Even those who were not open to conviction were perfectly willing to be entertained by an exhibition of amateur conjuring.

Leonard felt that something tangible was expected of him.

“Has anyone present,” he asked, “got a three-penny bit or some small object of no particular value —?”

“You’re surely not going to make coins disappear, or something primitive of that sort?” said Clovis contemptuously.

“I think it very unkind of you not to carry out my suggestion of turning me into a wolf,” said Mary Hampton, as she crossed over to the conservatory to give her macaws their usual tribute from the dessert dishes.

“I have already warned you of the danger of treating these powers in a mocking spirit,” said Leonard solemnly.

“I don’t believe you can do it,” laughed Mary provocatively from the conservatory; “I dare you to do it if you can. I defy you to turn me into a wolf.”

As she said this she was lost to view behind a clump of azaleas.

“Mrs. Hampton —” began Leonard with increased solemnity, but he got no further. A breath of chill air seemed to rush across the room, and at the same time the macaws broke forth into ear-splitting screams.

“What on earth is the matter with those confounded birds, Mary?” exclaimed Colonel Hampton; at the same moment an even more piercing scream from Mavis Pellington stampeded the entire company from their seats. In various attitudes of helpless horror or instinctive defence they confronted the evil-looking grey beast that was peering at them from amid a setting of fern and azalea.

Mrs. Hoops was the first to recover from the general chaos of fright and bewilderment.

“Leonard!” she screamed shrilly to her nephew, “turn it back into Mrs. Hampton at once! It may fly at us at any moment. Turn it back!”

“I— I don’t know how to,” faltered Leonard, who looked more scared and horrified than anyone.

“What!” shouted Colonel Hampton, “you’ve taken the abominable liberty of turning my wife into a wolf, and now you stand there calmly and say you can’t turn her back again!”

To do strict justice to Leonard, calmness was not a distinguishing feature of his attitude at the moment.

“I assure you I didn’t turn Mrs. Hampton into a wolf; nothing was farther from my intentions,” he protested.

“Then where is she, and how came that animal into the conservatory?” demanded the Colonel.

“Of course we must accept your assurance that you didn’t turn Mrs. Hampton into a wolf,” said Clovis politely, “but you will agree that appearances are against you.”

“Are we to have all these recriminations with that beast standing there ready to tear us to pieces?” wailed Mavis indignantly.

“Lord Pabham, you know a good deal about wild beasts —” suggested Colonel Hampton.

“The wild beasts that I have been accustomed to,” said Lord Pabham, “have come with proper credentials from well-known dealers, or have been bred in my own menagerie. I’ve never before been confronted with an animal that walks unconcernedly out of an azalea bush, leaving a charming and popular hostess unaccounted for. As far as one can judge from outward characteristics,” he continued, “it has the appearance of a well-grown female of the North American timber-wolf, a variety of the common species canis lupus.”

“Oh, never mind its Latin name,” screamed Mavis, as the beast came a step or two further into the room; “can’t you entice it away with food, and shut it up where it can’t do any harm?”

“If it is really Mrs. Hampton, who has just had a very good dinner, I don’t suppose food will appeal to it very strongly,” said Clovis.

“Leonard,” beseeched Mrs. Hoops tearfully, “even if this is none of your doing can’t you use your great powers to turn this dreadful beast into something harmless before it bites us all — a rabbit or something?”

“I don’t suppose Colonel Hampton would care to have his wife turned into a succession of fancy animals as though we were playing a round game with her,” interposed Clovis.

“I absolutely forbid it,” thundered the Colonel.

“Most wolves that I’ve had anything to do with have been inordinately fond of sugar,” said Lord Pabham; “if you like I’ll try the effect on this one.”

He took a piece of sugar from the saucer of his coffee cup and flung it to the expectant Louisa, who snapped it in mid-air. There was a sigh of relief from the company; a wolf that ate sugar when it might at the least have been employed in tearing macaws to pieces had already shed some of its terrors. The sigh deepened to a gasp of thanks-giving when Lord Pabham decoyed the animal out of the room by a pretended largesse of further sugar. There was an instant rush to the vacated conservatory. There was no trace of Mrs. Hampton except the plate containing the macaws’ supper.

“The door is locked on the inside!” exclaimed Clovis, who had deftly turned the key as he affected to test it.

Everyone turned towards Bilsiter.

“If you haven’t turned my wife into a wolf,” said Colonel Hampton, “will you kindly explain where she has disappeared to, since she obviously could not have gone through a locked door? I will not press you for an explanation of how a North American timber-wolf suddenly appeared in the conservatory, but I think I have some right to inquire what has become of Mrs. Hampton.”

Bilsiter’s reiterated disclaimer was met with a general murmur of impatient disbelief.

“I refuse to stay another hour under this roof,” declared Mavis Pellington.

“If our hostess has really vanished out of human form,” said Mrs. Hoops, “none of the ladies of the party can very well remain. I absolutely decline to be chaperoned by a wolf!”

“It’s a she-wolf,” said Clovis soothingly.

The correct etiquette to be observed under the unusual circumstances received no further elucidation. The sudden entry of Mary Hampton deprived the discussion of its immediate interest.

“Some one has mesmerised me,” she exclaimed crossly; “I found myself in the game larder, of all places, being fed with sugar by Lord Pabham. I hate being mesmerised, and the doctor has forbidden me to touch sugar.”

The situation was explained to her, as far as it permitted of anything that could be called explanation.

“Then you really did turn me into a wolf, Mr. Bilsiter?” she exclaimed excitedly.

But Leonard had burned the boat in which he might now have embarked on a sea of glory. He could only shake his head feebly.

“It was I who took that liberty,” said Clovis; “you see, I happen to have lived for a couple of years in North–Eastern Russia, and I have more than a tourist’s acquaintance with the magic craft of that region. One does not care to speak about these strange powers, but once in a way, when one hears a lot of nonsense being talked about them, one is tempted to show what Siberian magic can accomplish in the hands of someone who really understands it. I yielded to that temptation. May I have some brandy? the effort has left me rather faint.”

If Leonard Bilsiter could at that moment have transformed Clovis into a cockroach and then have stepped on him he would gladly have performed both operations.

The She-Wolf

From ‘Beasts and Super-Beasts’

by Saki (H. H. Munro)

(1870 – 1916)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Saki, Saki, The Art of Reading

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature