Fleurs du Mal Magazine

D.H.Lawrence

Bei Hennef

The little river twittering in the twilight,

The wan, wondering look of the pale sky,

This is almost bliss.

And everything shut up and gone to sleep,

All the troubles and anxieties and pain

Gone under the twilight.

Only the twilight now, and the soft “Sh!” of the river

That will last for ever.

And at last I know my love for you is here;

I can see it all, it is whole like the twilight,

It is large, so large, I could not see it before,

Because of the little lights and flickers and interruptions,

Troubles, anxieties and pains.

You are the call and I am the answer,

You are the wish, and I the fulfilment,

You are the night, and I the day.

What else – it is perfect enough.

It is perfectly complete,

You and I,

What more-?

Strange, how we suffer in spite of this.

D.H.Lawrence (1883 – 1930)

Bei Hennef

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, D.H. Lawrence, Lawrence, D.H.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Youth And Age a poem

Verse, a breeze ‘mid blossoms straying,

Where Hope clung feeding, like a bee

Both were mine! Life went a-maying

With Nature, Hope, and Poesy,

When I was young!

When I was young? Ah, woeful When!

Ah! for the change ‘twixt Now and Then!

This breathing house not built with hands,

This body that does me grievous wrong,

O’er aery cliffs and glittering sands

How lightly then it flashed along,

Like those trim skiffs, unknown of yore,

On winding lakes and rivers wide,

That ask no aid of sail or oar,

That fear no spite of wind or tide!

Nought cared this body for wind or weather

When Youth and I lived in’t together.

Flowers are lovely; Love is flower-like;

Friendship is a sheltering tree;

O the joys! that came down shower-like,

Of Friendship, Love, and Liberty,

Ere I was old!

Ere I was old? Ah woeful Ere,

Which tells me, Youth’s no longer here!

O Youth! for years so many and sweet

‘Tis known that Thou and I were one,

I’ll think it but a fond conceit

It cannot be that Thou art gone!

Thy vesper-bell hath not yet tolled

And thou wert aye a masker bold!

What strange disguise hast now put on,

To make believe that thou art gone?

I see these locks in silvery slips,

This drooping gait, this altered size:

But Springtide blossoms on thy lips,

And tears take sunshine from thine eyes:

Life is but Thought: so think I will

That Youth and I are housemates still.

Dew-drops are the gems of morning,

But the tears of mournful eve!

Where no hope is, life’s a warning

That only serves to make us grieve

When we are old:

That only serves to make us grieve

With oft and tedious taking-leave,

Like some poor nigh-related guest

That may not rudely be dismist;

Yet hath out-stayed his welcome while,

And tells the jest without the smile.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772 – 1834)

Poem: Youth And Age

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Coleridge, Coleridge, Samuel Taylor

Foto Antony Kok – Archief JVK Tilburg

GESCHIEDENIS VAN EEN BIOGRAFIE

Over Antony Kok

Door Jef en Hanneke van Kempen

‘De wereld van heden raast door in Dada’s voetspoor’ is een veel geciteerd aforisme van de dichter Antony Kok, dat hij schreef toen hij al oud was. Maar was Kok ook de Dada-dichter die auteur K. Schippers in hem zag, in zijn lezing ter gelegenheid van de opening van de grote Kok-tentoonstelling in de Stadsschouwburg / Kultureel Sentrum van Tilburg begin 1985? Bedoelde Kok, zoals K. Schippers zei, dat Dada niet behoorde tot een tijd of een plaats? Dat Dada niet gebonden was aan een beweging. Dat Antony Kok met zijn aforisme moet hebben bedoeld, dat Dada stond voor een mentaliteit, die van alle tijden was en van de hele wereld? 1)

Of was Antony Kok de man die alleen door toeval, door het feit dat hij beste vrienden zou worden met enkele van de grootste kunstenaars van de 20ste Eeuw, Theo van Doesburg( (1883 – 1931) en Kurt Schwitters, en in navolging van hen Dada-dichter werd, zoals J.A. Dautzenberg (1944 – 2009) in 1985 – in een paginagroot artikel- in De Volkskrant schreef: Een Dada-dichter die op latere leeftijd verstrikt zou raken in mystiek. 2)

Of is het allebei waar? Wat helpt het de biograaf die al 35 jaar probeert het leven van een ander te ontrafelen? Is het niet zo dat zowel Hugo Bal als Theo van Doesburg aan het eind van hun leven Rooms-katholiek zijn geworden? Daar hoor je nooit veel over.

Ottevanger haalt in haar zeer degelijke, maar weinig empathische brievenboek, zelfs meer dan eens dichter Til Brugman aan, die Antony Kok omschreef als een : ‘Een wezensvreemde man, die hij altijd al geweest was’. Is dat echt zo? 3)

Zoveel schrijvers, zoveel meningen. Kok is de afgelopen jaren gekenschetst als een wereldvreemde, een absurdist, een socialist, een pacifist, een religieus fanaat, een middeleeuwer, een dadaïst en nog zoveel meer.

# LEES HIER VERDER GeschiedenisVanEenBiografie PDF

Jaargang 35 – 2017 – nummer 1

Tijdschrift Tilburg

Jef van Kempen en Hanneke van Kempen:

Geschiedenis van een biografie. Over Antony Kok

En verder o.a.

Petra Robben: Mijmering over een Mondriaan in Tilburg. Internationale Tentoonstelling van Nijverheid, Handel en Kunst, 1913

Niko de Wit: ‘Den Does’, een uitkijktoren voor Tilburg. Een hommage aan Theo van Doesburg

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Antony Kok, Art & Literature News, Bauhaus, BIOGRAPHY, Dada, De Stijl, Doesburg, Theo van, Hanneke van Kempen, Jef van Kempen, Kok, Antony, Kurt Schwitters, Piet Mondriaan, Piet Mondriaan, Schwitters, Kurt, Theo van Doesburg, Theo van Doesburg

Innokenti Annenski

(1855–1909)

Mijn ideaal

Het ruisen van ontstoken gaslicht

Boven het grauw en grijs bezoek,

De stille weemoed in het aanzicht

Van een terloops vergeten boek,

En dat ik daar dan, onbewogen,

Als ging het immer wonderwel,

Over vergeeld papier gebogen,

Die irritante zijnsvraag stel.

Innokenti Annenski, Идеал, 1904

Vertaling Paul Bezembinder, 2016

Paul Bezembinder studeerde theoretische natuurkunde in Nijmegen. In zijn poëzie zoekt hij in vooral klassieke versvormen en thema’s naar de balans tussen serieuze poëzie, pastiche en smartlap. Zijn gedichten (Nederlands) en vertalingen (Russisch-Nederlands) verschenen in verschillende (online) literaire tijdschriften. Voorbeelden van zijn werk zijn te vinden op zijn website, www.paulbezembinder.nl

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Annenski, Annenski, Innokenti, Archive A-B

Oscar Wilde

Oscar Wilde

(1854 – 1900)

The Disciple

When Narcissus died the pool of his pleasure changed from a cup of sweet waters into a cup of salt tears, and the Oreads came weeping through the woodland that they might sing to the pool and give it comfort.

And when they saw that the pool had changed from a cup of sweet waters into a cup of salt tears, they loosened the green tresses of their hair and cried to the pool and said, ‘We do not wonder that you should mourn in this manner for Narcissus, so beautiful was he.’

‘But was Narcissus beautiful?’ said the pool.

‘Who should know that better than you?’ answered the Oreads. ‘Us did he ever pass by, but you he sought for, and would lie on your banks and look down at you, and in the mirror of your waters he would mirror his own beauty.’

And the pool answered, ‘But I loved Narcissus because, as he lay on my banks and looked down at me, in the mirror of his eyes I saw ever my own beauty mirrored.’

Oscar Wilde 1894

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive W-X, Wilde, Oscar, Wilde, Oscar

Eens in de zoveel jaar verschijnt er een roman die zó verslavend is dat je er afspraken voor afzegt, uit de trein vergeet te stappen en stiekem iets eerder van je werk vertrekt. Zo’n uitzonderlijke roman schreef Johan Harstad: zijn manier van vertellen maakt dat je niet rust voordat je de laatste pagina hebt omgeslagen.

Eens in de zoveel jaar verschijnt er een roman die zó verslavend is dat je er afspraken voor afzegt, uit de trein vergeet te stappen en stiekem iets eerder van je werk vertrekt. Zo’n uitzonderlijke roman schreef Johan Harstad: zijn manier van vertellen maakt dat je niet rust voordat je de laatste pagina hebt omgeslagen.

Max, Mischa & het Tet-offensief is het verhaal van toneelregisseur Max Hansen, die als puber vanuit Noorwegen naar Amerika emigreert. Hij heeft moeite om zijn jeugd in Stavanger, waar hij als kind van communistische ouders het Tet-offensief naspeelde, achter zich te laten, maar ontdekt in New York dat eigenlijk iedereen daar ontheemd is. In kunstenares Mischa, acteur Mordecai en Vietnamveteraan Owen vindt hij dierbare lotgenoten.

Harstads magnum opus is een hypnotiserende vertelling die vele decennia en continenten omspant: van de oorlog in Vietnam en Apocalypse Now tot jazzmuziek, van Mark Rothko en Burning Man tot de aanslag op de Twin Towers. Uitgeverij Podium zegt bijzonder trots te zijn dat zij deze monumentale roman als eerste buitenlandse uitgever kunnen brengen, in een indrukwekkende vertaling van Edith Koenders en Paula Stevens.

Quote: ‘De werelden die Harstad creëert zijn zo verontrustend, romantisch en verslavend, dat het mij moeite kost om naar de echte terug te keren.’ Arjen Lubach

Johan Harstad (1979) debuteerde in 2001 met een bundel verzameld proza. Zijn debuutroman Buzz Aldrin, waar ben je gebleven? werd opgevolgd door de roman Hässelby, een David Lynch-achtig verhaal over een man die al 42 jaar bij zijn vader woont. In 2011 verscheen zijn young adult sf-roman Darlah. Naast zijn schrijverschap werkt Harstad als grafisch ontwerper onder het label LACKTR. Voorafgaand aan zijn succesvolle roman Buzz Aldrin, waar ben je gebleven? publiceerde de Noorse schrijver Johan Harstad de verhalenbundel Ambulance. De Nederlandse vertaling van deze verhalenbundel verscheen in 2014. In 2017 verschijnt zijn nieuwe roman: Max, Mischa & het Tet-offensief.

Bibliografie Johan Harstad

2006 Buzz Aldrin, waar ben je gebleven? (roman)

2009 Hässelby (roman)

2011 Darlah (roman)

2014 Ambulance (verhalen)

2017 Max, Mischa & het Tet-offensief (roman)*

Johan Harstad

Max, Mischa & het Tet-offensief

1232 pagina’s – € 29,99

Omslag: b’IJ Barbara

ISBN: 978 90 5759 849 4

vertaler: Edith Koenders & Paula Stevens

Uitgeverij Podium

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Archive G-H, Art & Literature News, DICTIONARY OF IDEAS

William Blake

The Lamb

Little Lamb, who made thee

Does thou know who made thee

Gave thee life & bid thee feed.

By the stream & o’er the mead;

Gave thee clothing of delight,

Softest clothing woolly bright;

Gave thee such a tender voice.

Making all the vales rejoice:

Little Lamb who made thee

Does thou know who made thee

Little Lamb I’ll tell thee,

Little Lamb I’ll tell thee;

He is called by thy name,

For he calls himself a Lamb:

He is meek & he is mild,

He became a little child

I a child & thou a lamb,

We are called by His name,

Little Lamb God bless thee,

Little Lamb God bless thee.

William Blake (1757 – 1827)

Poem: The Lamb

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Blake, William

Vertaling van het gedicht Theater van Jef van Kempen in het Zuid-Afrikaans door Bernard Odendaal.

Eerder gepubliceerd door Carina van der Walt in: Versindaba – ‘n Kollektiewe weblog vir die Afrikaanse digkuns –

http://versindaba.co.za/2016/03/31/carina-van-der-walt-jeroen-bosch-se-skilderye/

Theater

Stel je voor: een toneel van dolende nachtvogels

boven een doorweekte woestijn, in een duister

hospitaal voor koortsige landlopers.

Stel je voor: een opera van rondborstige gedrochten,

verwekt in een glazen stolp, amechtig lispelend,

op kromme stelten strompelend, in een vuile

sneeuwjacht van de diepe winter.

Eind goed al goed vonden de trage doden hun draai

en bestegen, tegen de keer, het paard van Troje

en maakten hun dromen waar.

Jef van Kempen

(Uit de bundel ‘Laatste Bedrijf’ 2012)

Teater

Stel jou voor: ’n toneel van dolende nagvoëls

bokant ’n deurweekte woestyn, in ’n donker

hospitaal vir koorsige boemelaars.

Stel jou voor: ’n opera van rondborstige gedrogte

verwek onder ’n glasstolp, uitasem lispelend,

op krom stelte strompelend, morsig aan die

jag in die diepwintersneeuw.

Einde goed alles goed kry die trae dooies hul draai

en bestyg, dwarstrekkerig, die perd van Troje

en maak hulle drome waar.

Vertaling Bernard Odendaal (2016)

FOTO: v.l.n.r. Martin Beversluis, Desmond Painter, Bernard Odendaal, Carina van der Walt, Annelie David, Bert Bevers en Jef van Kempen (foto Nel van Kempen 2015)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Archive O-P, Bernard Odendaal, Bevers, Bert, Beversluis, Martin, Carina van der Walt, Jef van Kempen, Kempen, Jef van, Literaire Salon in 't Wevershuisje, TRANSLATION ARCHIVE

Wim Brands schreef in 2010 op het blog van Tirade: ‘Er werd mij gevraagd of er iemand is die ik me wil blijven herinneren. Ik mocht maar één persoon kiezen. Ik koos mijn grootvader. Aan wie ik wel eens een gedicht heb gewijd dat begon met de regel: “Hij had een bokkenwagen en een kraai.”‘

Wim Brands schreef in 2010 op het blog van Tirade: ‘Er werd mij gevraagd of er iemand is die ik me wil blijven herinneren. Ik mocht maar één persoon kiezen. Ik koos mijn grootvader. Aan wie ik wel eens een gedicht heb gewijd dat begon met de regel: “Hij had een bokkenwagen en een kraai.”‘

Veel van Wim Brands’ anekdotes waren aanleiding tot poëzie. In zes bundels en heel veel tijdschriftpublicaties veroverde Brands zijn plek als dichter, naast zijn groeiende statuur als anchorman van VPRO Boeken, of eigenlijk – bij uitbreiding – als de belangrijke televisiepersoonlijkheid die kunst en literatuur hoog in het vaandel had.

Er is dan ook geen betere manier om kennis te nemen van wat en wie Wim Brands allemaal was dan door lezing van deze Verzamelde gedichten. In de geest van Brands zijn we met de keuze overigens soepel omgesprongen. Er staat een stripverhaal in deze bundel, en er zijn blogs en brieven in te vinden. Voor Brands zijn gedichten verhalen, en hij maakt van verhalen poëzie,steeds door heel goed over de vorm na te denken, door in te dikken en te schrappen – want het kon altijd preciezer.

Deze verzameling toont wat een geweldig dichter Wim Brands was. De bundel bestaat uit zijn verschenen bundels plus veel ongepubliceerd materiaal. Thomas Verbogt schreef een nawoord.

Wim Brands (1959-2016) was een Nederlands dichter, journalist en presentator. Hij publiceerde acht dichtbundels, werkte jarenlang voor de VPRO-radio en presenteerde van 2005 tot 2016 het televisieprogramma Boeken.

Wim Brands schreef in 2010: ‘Er werd mij gevraagd of er iemand is die ik me wil blijven herinneren. Ik mocht maar één persoon kiezen. Ik koos mijn grootvader. Aan wie ik wel eens een gedicht heb gewijd dat begon met de regel: “Hij had een bokkenwagen en een kraai.”’

Veel van Brands’ anekdotes waren aanleiding tot poëzie. Met zijn bundels en vele tijdschriftpublicaties veroverde Brands zijn plek als dichter, naast zijn groeiende statuur als anchorman van VPRO Boeken. Er is dan ook geen betere manier om kennis te nemen van wat en wie Wim Brands allemaal was dan door lezing van deze Verzamelde gedichten. In de geest van Brands is er met de keuze soepel omgesprongen; de verzameling bevat zijn bundels, maar ook niet eerder gepubliceerd werk, blogs, brieven en zelfs een stripverhaal.

Over de poëzie van Wim Brands:

‘De gedichten zijn romantisch van inhoud en nuchter van toon. Ze openen op een haast vanzelfsprekende manier duistere gebieden en dieptes in de geest.’ – De Volkskrant (*****)

‘Mooie gedichten, die op een terloopse manier een raadselachtigheid behouden.’ – Het Parool

Wim Brands

Verzamelde gedichten

ISBN 9789028261921

Van Oorschot 2017, € 27,50

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Archive A-B, Art & Literature News, AUDIO, CINEMA, RADIO & TV, Brands, Wim

The Monkey’s Paw

The Monkey’s Paw

by W. W. Jacobs

Without, the night was cold and wet, but in the small parlor of Lakesnam Villa the blinds were drawn and the fire burned brightly. Father and son were at chess, the former, who possessed ideas about the game involving radical changes, putting his king into such sharp and unnecessary perils that it even provoked comment from the whitehaired old lady knitting placidly by the fire.

“Hark at the wind,” said Mr. White, who, having seen a fatal mistake after it was too late, was amiably desirous of preventing his son from seeing it.

“I’m listening,” said the latter, grimly surveying the board as he stretched out his hand. “Check.”

“I should hardly think that he’d come tonight,” said his father, with his hand poised over the board.

“Mate,” replied the son.

“That’s the worst of living so far out,” bawled Mr. White, with sudden and unlooked-for violence; “of all the beastly, slushy, out-of-the-way places to live in, this is the worst. Pathway’s a bog, and the road’s a torrent. I don’t know what people are thinking about. I suppose because only two houses on the road are let, they think it doesn’t matter.”

“Never mind, dear,” said his wife soothingly; “perhaps you’ll win the next one.”

Mr. White looked up sharply, just in time to intercept a knowing glance between mother and son. The words died away on his lips, and he hid a guilty grin in his thin grey beard.

“There he is,” said Herbert White, as the gate banged to loudly and heavy footsteps came toward the door.

The old man rose with hospitable haste, and opening the door, was heard condoling with the new arrival. The new arrival also condoled with himself, so that Mrs. White said, “Tut, tut!” and coughed gently as her husband entered the room, followed by a tall, burly man, beady of eye and rubicund of visage.

“Sergeant Major Morris,” he said, introducing him.

The sergeant major shook hands, and taking the proffered seat by the fire, watched contentedly while his host got out whisky and tumblers and stood a small copper kettle on the fire.

At the third glass his eyes got brighter, and he began to talk, the little family circle regarding with eager interest this visitor from distant parts, as he squared his broad shoulders in the chair and spoke of strange scenes and doughty deeds, of wars and plagues and strange peoples.

“Twenty-one years of it,” said Mr. White, nodding at his wife and son. “When he went away he was a slip of a youth in the warehouse. Now look at him.”

“He don’t look to have taken much harm,” said Mrs. White politely. “I’d like to go to India myself,” said the old man, “just to look round a bit, you know.”

“Better where you are,” said the sergeant major, shaking his head. He put down the empty glass, and sighing softly, shook it again.

“I should like to see those old temples and fakirs and jugglers,” said the old man. “What was that you started telling me the other day about a monkey’s paw or something, Morris?”

“Nothing,” said the soldier hastily. “Leastways, nothing worth hearing.”

“Monkey’s paw?” said Mrs. White curiously.

“Well, it’s just a bit of what you might call magic, perhaps,” said the sergeant major offhandedly.

His three listeners leaned forward eagerly. The visitor absentmindedly put his empty glass to his lips and then set it down again. His host filled it for him.

“To look at,” said the sergeant major, fumbling in his pocket, “it’s just an ordinary little paw, dried to a mummy.”

He took something out of his pocket and proffered it. Mrs. White drew back with a grimace, but her son, taking it, examined it curiously.

“And what is there special about it?” inquired Mr. White, as he took it from his son, and having examined it, placed it upon the table.

“It had a spell put on it by an old fakir,” said the sergeant major, “a very holy man. He wanted to show that fate ruled people’s lives, and that those who interfered with it did so to their sorrow. He put a spell on it so that three separate men could each have three wishes from it.”

His manner was so impressive that his hearers were conscious that their light laughter jarred somewhat.

“Well, why don’t you have three, sir?” said Herbert White cleverly.

The soldier regarded him in the way that middle age is wont to regard presumptuous youth. “I have,” he said quietly, and his blotchy face whitened.

“And did you really have the three wishes granted?” asked Mrs. White.

“I did,” said the sergeant major, and his glass tapped against his strong teeth.

“And has anybody else wished?” inquired the old lady.

“The first man had his three wishes, yes,” was the reply. “I don’t know what the first two were, but the third was for death. That’s how I got the paw.”

His tones were so grave that a hush fell upon the group.

“If you’ve had your three wishes, it’s no good to you now, then, Morris,” said the old man at last. “What do you keep it for?”

The soldier shook his head. “Fancy, I suppose,” he said slowly. “I did have some idea of selling it, but I don’t think I will. It has caused enough mischief already. Besides, people won’t buy. They think it’s a fairy tale, some of them, and those who do think anything of it want to try it first and pay me afterward.”

“If you could have another three wishes,” said the old man, eyeing him keenly, “would you have them?”

“I don’t know,” said the other. “I don’t know.”

He took the paw, and dangling it between his front finger and thumb, suddenly threw it upon the fire. White, with a slight cry, stooped down and snatched it off.

“Better let it burn,” said the soldier solemnly.

“If you don’t want it, Morris,” said the old man, “give it to me.”

“I won’t,” said his friend doggedly. “I threw it on the fire. If you keep it, don’t blame me for what happens. Pitch it on the fire again, like a sensible man.”

The other shook his head and examined his new possession closely. “How do you do it?” he inquired.

“Hold it up in your right hand and wish aloud,” said the sergeant major, “but I warn you of the consequences.”

“Sounds like the Arabian Nights,” said Mrs. White, as she rose and began to set the supper. “Don’t you think you might wish for four pairs of hands for me?”

Her husband drew the talisman from his pocket and then all three burst into laughter as the sergeant major, with a look of alarm on his face, caught him by the arm.

“If you must wish,” he said gruffly, “wish for something sensible.”

Mr. White dropped it back into his pocket, and placing chairs, motioned his friend to the table. In the business of supper the talisman was partly forgotten, and afterward the three sat listening in an enthralled fashion to a second installment of the soldier’s adventures in India.

“If the tale about the monkey’s paw is not more truthful than those he has been telling us,” said Herbert, as the door closed behind their guest, just in time for him to catch the last train, “we shan’t make much out of it.”

“Did you give him anything for it, Father?” inquired Mrs. White, regarding her husband closely.

“A trifle,” said he, coloring slightly. “He didn’t want it, but I made him take it. And he pressed me again to throw it away.”

“Likely,” said Herbert, with pretended horror. “Why, we’re going to be rich, and famous, and happy. Wish to be an emperor, Father, to begin with; then you can’t be henpecked.”

He darted around the table, pursued by the maligned Mrs. White armed with an antimacassar.

Mr. White took the paw from his pocket and eyed it dubiously. “I don’t know what to wish for, and that’s a fact,” he said slowly. “It seems to me I’ve got all I want.”

“If you only cleared the house, you’d be quite happy, wouldn’t you?” said Herbert, with his hand on his shoulder. “Well, wish for two hundred pounds, then; that’ll just do it.”

His father, smiling shamefacedly at his own credulity, held up the talisman, as his son, with a solemn face somewhat marred by a wink at his mother, sat down at the piano and struck a few impressive chords.

“I wish for two hundred pounds,” said the old man distinctly.

A fine crash from the piano greeted the words, interrupted by a shuddering cry from the old man. His wife and son ran toward him.

“It moved,” he cried, with a glance of disgust at the object as it lay on the floor. “As I wished, it twisted in my hand like a snake.”

“Well, I don’t see the money,” said his son, as he picked it up and placed it on the table, “and I bet I never shall.”

“It must have been your fancy, Father,” said his wife, regarding him anxiously.

He shook his head. “Never mind, though; there’s no harm done, but it gave me a shock all the same.”

They sat down by the fire again while the two men finished their pipes. Outside, the wind was higher than ever, and the old man started nervously at the sound of a door banging upstairs. A silence unusual and depressing settled upon all three, which lasted until the old couple rose to retire for the night.

“I expect you’ll find the cash tied up in a big bag in the middle of your bed,” said Herbert, as he bade them good night, “and something horrible squatting up on top of the wardrobe watching you as you pocket your ill-gotten gains.”

. . .

In the brightness of the wintry sun next morning as it streamed over the breakfast table, Herbert laughed at his fears. There was an air of prosaic wholesomeness about the room which it had lacked on the previous night, and the dirty, shriveled little paw was pitched on the sideboard with a carelessness which betokened no great belief in its virtues.

“I suppose all old soldiers are the same,” said Mrs. White. “The idea of our listening to such nonsense! How could wishes be granted in these days? And if they could, how could two hundred pounds hurt you, Father?”

“Might drop on his head from the sky,” said the frivolous Herbert.

“Morris said the things happened so naturally,” said his father, “that you might, if you so wished, attribute it to coincidence.”

“Well, don’t break into the money before I come back,” said Herbert, as he rose from the table. “I’m afraid it’ll turn you into a mean, avaricious man, and we shall have to disown you.”

His mother laughed, and following him to the door, watched him down the road, and returning to the breakfast table, was very happy at the expense of her husband’s credulity. All of which did not prevent her from scurrying to the door at the postman’s knock, nor prevent her from referring somewhat shortly to retired sergeant majors of bibulous habits, when she found that the post brought a tailor’s bill.

“Herbert will have some more of his funny remarks, I expect, when he comes home,” she said, as they sat at dinner.

“I daresay,” said Mr. White, pouring himself out some beer; “but for all that, the thing moved in my hand; that I’ll swear to.”

“You thought it did,” said the old lady soothingly.

“I say it did,” replied the other. “There was no thought about it; I had just– What’s the matter?”

His wife made no reply. She was watching the mysterious movements of a man outside, who, peering in an undecided fashion at the house, appeared to be trying to make up his mind to enter. In mental connection with the two hundred pounds, she noticed that the stranger was well dressed and wore a silk hat of glossy newness. Three times he paused at the gate, and then walked on again. The fourth time he stood with his hand upon it, and then with sudden resolution flung it open and walked up the path. Mrs. White at the same moment placed her hands behind her, and hurriedly unfastening the strings of her apron, put that useful article of apparel beneath the cushion of her chair.

She brought the stranger, who seemed ill at ease, into the room. He gazed furtively at Mrs. White, and listened in a preoccupied fashion as the old lady apologized for the appearance of the room, and her husband’s coat, a garment which he usually reserved for the garden. She then waited as patiently as her sex would permit for him to broach his business, but he was at first strangely silent.

“I–was asked to call,” he said at last, and stooped and picked a piece of cotton from his trousers. “I come from Maw and Meggins.”

The old lady started. “Is anything the matter?” she asked breathlessly. “Has anything happened to Herbert? What is it? What is it?”

Her husband interposed. “There, there, Mother,” he said hastily. “Sit down, and don’t jump to conclusions. You’ve not brought bad news, I’m sure, sir,” and he eyed the other wistfully.

“I’m sorry–” began the visitor.

“Is he hurt?” demanded the mother.

The visitor bowed in assent. “Badly hurt,” he said quietly, “but he is not in any pain.”

“Oh, thank God!” said the old woman, clasping her hands. “Thank God for that! Thank–“

She broke off suddenly as the sinister meaning of the assurance dawned upon her and she saw the awful confirmation of her fears in the other’s averted face. She caught her breath, and turning to her slower-witted husband, laid her trembling old hand upon his. There was a long silence.

“He was caught in the machinery,” said the visitor at length, in a low voice.

“Caught in the machinery,” repeated Mr. White, in a dazed fashion, “yes.”

He sat staring blankly out at the window, and taking his wife’s hand between his own, pressed it as he had been wont to do in their old courting days nearly forty years before.

“He was the only one left to us,” he said, turning gently to the visitor. “It is hard.”

The other coughed, and rising, walked slowly to the window. “The firm wished me to convey their sincere sympathy with you in your great loss,” he said, without looking around. “I beg that you will understand I am only their servant and merely obeying orders.”

There was no reply; the old woman’s face was white, her eyes staring, and her breath inaudible; on the husband’s face was a look such as his friend the sergeant might have carried into his first action.

“I was to say that Maw and Meggins disclaim all responsibility,” continued the other. “They admit no liability at all, but in consideration of your son’s services they wish to present you with a certain sum as compensation.”

Mr. White dropped his wife’s hand, and rising to his feet, gazed with a look of horror at his visitor. His dry lips shaped the words, “How much?”

“Two hundred pounds,” was the answer.

Unconscious of his wife’s shriek, the old man smiled faintly, put out his hands like a sightless man, and dropped, a senseless heap, to the floor.

. . .

In the huge new cemetery, some two miles distant, the old people buried their dead, and came back to a house steeped in shadow and silence. It was all over so quickly that at first they could hardly realize it, and remained in a state of expectation, as though of something else to happen–something else which was to lighten this load, too heavy for old hearts to bear. But the days passed, and expectation gave place to resignation–the hopeless resignation of the old, sometimes miscalled apathy. Sometimes they hardly exchanged a word, for now they had nothing to talk about, and their days were long to weariness.

It was about a week after that that the old man, waking suddenly in the night, stretched out his hand and found himself alone. The room was in darkness, and the sound of subdued weeping came from the window. He raised himself in bed and listened.

“Come back,” he said tenderly. “You will be cold.”

“It is colder for my son,” said the old woman, and wept afresh.

The sound of her sobs died away on his ears. The bed was -warm, and his eyes heavy with sleep. He dozed fitfully, and then slept until a sudden cry from his wife awoke him with a start.

“The monkey’s paw!” she cried wildly. “The monkey’s paw!”

He started up in alarm. “Where? Where is it? What’s the matter?” She came stumbling across the room toward him. “I want it,” she said quietly. “You’ve not destroyed it?”

“It’s in the parlor, on the bracket,” he replied, marveling. “Why?”

She cried and laughed together, and bending over, kissed his cheek.

“I only just thought of it,” she said hysterically. “Why didn’t I think of it before? Why didn’t you think of it?”

“Think of what?” he questioned.

“The other two wishes,” she replied rapidly. “We’ve only had one.”

“Was not that enough?” he demanded fiercely.

“No,” she cried triumphantly; “we’ll have one more. Go down and get it quickly, and wish our boy alive again.”

The man sat up in bed and flung the bedclothes from his quaking limbs. “Good God, you are mad!” he cried, aghast.

“Get it,” she panted; “get it quickly, and wish– Oh, my boy, my boy!”

Her husband struck a match and lit the candle. “Get back to bed,” he said unsteadily. “You don’t know what you are saying.”

“We had the first wish granted,” said the old woman feverishly; “why not the second?”

“A coincidence,” stammered the old man.

“Go and get it and wish,” cried the old woman, and dragged him toward the door.

He went down in the darkness, and felt his way to the parlor, and then to the mantelpiece.

The talisman was in its place, and a horrible fear that the unspoken wish might bring his mutilated son before him ere he could escape from the room seized upon him, and he caught his breath as he found that he had lost the direction of the door. His brow cold with sweat, he felt his way around the table, and groped along the wall until he found himself in the small passage with the unwholesome thing in his hand.

Even his wife’s face seemed changed as he entered the room. It was white and expectant, and to his fears seemed to have an unnatural look upon it. He was afraid of her.

“Wish!” she cried, in a strong voice.

“It is foolish and wicked,” he faltered.

“Wish!” repeated his wife.

He raised his hand. “I wish my son alive again.”

The talisman fell to the floor, and he regarded it shudderingly. Then he sank trembling into a chair as the old woman, with burning eyes, walked to the window and raised the blind.

He sat until he was chilled with the cold, glancing occasionally at the figure of the old woman peering through the window. The candle end, which had burned below the rim of the china candlestick, was throwing pulsating shadows on the ceiling and walls, until, with a flicker larger than the rest, it expired. The old man, with an unspeakable sense of relief at the failure of the talisman, crept back to his bed, and a minute or two afterward the old woman came silently and apathetically beside him.

Neither spoke, but both lay silently listening to the ticking of the clock. A stair creaked, and a squeaky mouse scurried noisily through the wall. The darkness was oppressive, and after lying for some time screwing up his courage, the husband took the box of matches, and striking one, went downstairs for a candle.

At the foot of the stairs the match went out, and he paused to strike another, and at the same moment a knock, so quiet and stealthy as to be scarcely audible, sounded on the front door.

The matches fell from his hand. He stood motionless, his breath suspended until the knock was repeated. Then he turned and fled swiftly back to his room, and closed the door behind him. A third knock sounded through the house.

“What’s that?” cried the old woman, starting up.

“A rat,” said the old man, in shaking tones, “a rat. It passed me on the stairs.”

His wife sat up in bed listening. A loud knock resounded through the house.

“It’s Herbert!” she screamed. “It’s Herbert!”

She ran to the door, but her husband was before her, and catching her by the arm, held her tightly.

“What are you going to do?” he whispered hoarsely.

“It’s my boy; it’s Herbert!” she cried, struggling mechanically. “I forgot it was two miles away. What are you holding me for? Let go. I must open the door.”

“For God’s sake don’t let it in,” cried the old man, trembling.

“You’re afraid of your own son,” she cried, struggling. “Let me go. I’m coming, Herbert; I’m coming.”

There was another knock, and another. The old woman with a sudden wrench broke free and ran from the room. Her husband followed to the landing, and called after her appealingly as she hurried downstairs. He heard the chain rattle back and the bottom bolt drawn slowly and stiffly from the socket. Then the old woman’s voice, strained and panting.

“The bolt,” she cried loudly. “Come down. I can’t reach it.”

But her husband was on his hands and knees groping wildly on the floor in search of the paw. If he could only find it before the thing outside got in. A perfect fusillade of knocks reverberated through the house, and he heard the scraping of a chair as his wife put it down in the passage against the door. He heard the creaking of the bolt as it came slowly back, and at the same moment, he found the monkey’s paw, and frantically breathed his third and last wish.

The knocking ceased suddenly, although the echoes of it were still in the house. He heard the chair drawn back and the door opened. A cold wind rushed up the staircase, and a long, loud wail of disappointment and misery from his wife gave him courage to run down to her side, and then to the gate beyond. The streetlamp flickering opposite shone on a quiet and deserted road.

W. W. Jacobs (1863-1943)

The Monkey’s Paw

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #Short Stories Archive, Archive I-J

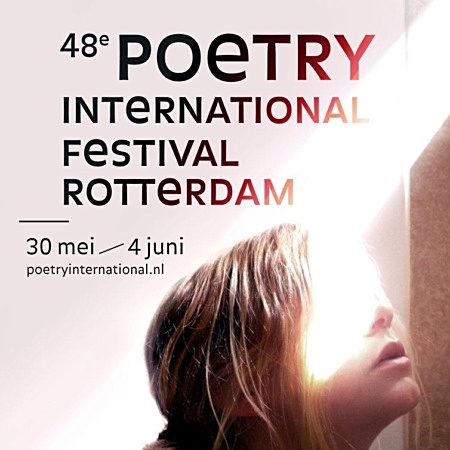

Op dinsdag 30 mei 2017 opent de 48e Poetry International in de Rotterdamse Schouwburg, aansluitend vindt het festival plaats tot en met zaterdag 3 juni in de zaal van het Ro Theater aan de William Boothlaan.

Voor de achtenveertigste keer haalt Poetry International de beste dichters uit alle windstreken naar Rotterdam. Naast gedichten in uiteenlopende talen brengt het festival een randprogramma met film, muziek, interviews, themabijeenkomsten en masterclasses. Een reis langs verre culturen met de kunst van het woord als brandstof. Iedereen is uitgenodigd op het jaarlijkse feest van de poëzie.

Op dinsdag 30 mei gaat het 48e Poetry International Festival van start in de Rotterdamse Schouwburg. Van woensdag 31 mei tot en met zondag 4 juni wordt het festival vervolgd in het Ro Theater aan de William Boothlaan en op verschillende andere locaties in het Witte de With Kwartier. Voor de achtenveertigste keer haalt Poetry International de beste dichters uit alle windstreken naar Rotterdam. Naast poëzievoordrachten in uiteenlopende talen brengt het festival films, muziek, interviews, lezingen, themabijeenkomsten en masterclasses. Een kermis van verlangen, kritiek, avontuur en troost, met de kunst van het woord als brandstof. Iedereen is uitgenodigd op het jaarlijkse feest van de poëzie.

Roberto Amato (ITA)

Mischa Andriessen (NLD)

Hannah van Binsbergen (NLD)

Dumitru Crudu (MDA)

Mária Ferenčuhová (SVK)

Gozo Yoshimasu (JAP)

Stefan Hertmans (BEL)

Ishion Hutchinson (JAM)

Mookie Katigbak-Lacuesta (PHL)

Anne Kawala (FRA)

John Kinsella (AUS)

Harry Man (GBR)

Marianne Morris (CAN / GBR)

Cees Nooteboom (NLD)

Michael Palmer (USA)

Margarida Vale de Gato (PRT)

Jan Wagner (DEU)

Mae Yway (MMR)

Zang Di (CHN)

Zhu Zhu (CHN)

48e Poetry International 30 mei – 4 juni 2017

Het jaarlijkse feest van de internationale poëzie

# Meer info op website Poetry International

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, Art & Literature News, POETRY ARCHIVE, Poetry International

Robert Bridges

A Toast to our Native Land

Huge and alert, irascible yet strong,

We make our fitful way ‘mid right and wrong.

One time we pour out millions to be free,

Then rashly sweep an empire from the sea!

One time we strike the shackles from the slaves,

And then, quiescent, we are ruled by knaves.

Often we rudely break restraining bars,

And confidently reach out toward the stars.

Yet under all there flows a hidden stream

Sprung from the Rock of Freedom, the great dream

Of Washington and Franklin, men of old

Who knew that freedom is not bought with gold.

This is the Land we love, our heritage,

Strange mixture of the gross and fine, yet sage

And full of promise destined to be great.

Drink to Our Native Land! God Bless the State!

Robert Seymour Bridges (1844 – 1930)

A Toast to our Native Land

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Bridges, Robert

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature