Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Naissance de Vénus

De sa profonde mère, encor froide et fumante,

Voici qu’au seuil battu de tempêtes, la chair

Amèrement vomie au soleil par la mer,

Se délivre des diamants de la tourmente.

Son sourire se forme, et suit sur ses bras blancs

Qu’éplore l’orient d’une épaule meurtrie,

De l’humide Thétis la pure pierrerie,

Et sa tresse se fraye un frisson sur ses flancs.

Le frais gravier, qu’arrose et fuit sa course agile,

Croule, creuse rumeur de soif, et le facile

Sable a bu les baisers de ses bonds puérils;

Mais de mille regards ou perfides ou vagues,

Son œil mobile mêle aux éclairs de périls

L’eau riante, et la danse infidèle des vagues.

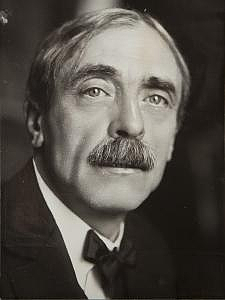

Paul Valéry

(1871-1945)

Naissance de Vénus

Poème

Album de vers anciens

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive U-V, Archive U-V, Valéry, Paul

When I Heard at the Close of the Day

When I heard at the close of the day how my name had been receiv’d with plaudits in the capitol, still it was not a happy night for me that follow’d,

And else when I carous’d, or when my plans were accomplish’d, still I was not happy,

But the day when I rose at dawn from the bed of perfect health, refresh’d, singing, inhaling the ripe breath of autumn,

When I saw the full moon in the west grow pale and disappear in the morning light,

When I wander’d alone over the beach, and undressing bathed, laughing with the cool waters, and saw the sun rise,

And when I thought how my dear friend my lover was on his way coming, O then I was happy,

O then each breath tasted sweeter, and all that day my food nourish’d me more, and the beautiful day pass’d well,

And the next came with equal joy, and with the next at evening came my friend,

And that night while all was still I heard the waters roll slowly continually up the shores,

I heard the hissing rustle of the liquid and sands as directed to me whispering to congratulate me,

For the one I love most lay sleeping by me under the same cover in the cool night,

In the stillness in the autumn moonbeams his face was inclined toward me,

And his arm lay lightly around my breast – and that night I was happy.

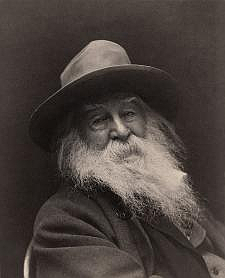

Walt Whitman

(1819 – 1892)

Poem: When I Heard at the Close of the Day

(Published in the Leaves of Grass. 1900)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive W-X, Archive W-X, Whitman, Walt

Friedrike

1

Verlaß Berlin, mit seinem dicken Sande

Und dünnen Tee und überwitz’gen Leuten,

Die Gott und Welt, und was sie selbst bedeuten,

Begriffen längst mit Hegelschem Verstande.

Komm mit nach Indien, nach dem Sonnenlande,

Wo Ambrablüten ihren Duft verbreiten,

Die Pilgerscharen nach dem Ganges schreiten,

Andächtig und im weißen Festgewande.

Dort, wo die Palmen wehn, die Wellen blinken,

Am heil’gen Ufer Lotosblumen ragen

Empor zu Indras Burg, der ewig blauen;

Dort will ich gläubig vor dir niedersinken,

Und deine Füße drücken, und dir sagen:

»Madame! Sie sind die schönste aller Frauen!«

2

Der Ganges rauscht, mit klugen Augen schauen

Die Antilopen aus dem Laub, sie springen

Herbei mutwillig, ihre bunten Schwingen

Entfaltend, wandeln stolzgespreizte Pfauen.

Tief aus dem Herzen der bestrahlten Auen

Blumengeschlechter, viele neue, dringen,

Sehnsuchtberauscht ertönt Kokilas Singen –

Ja, du bist schön, du schönste aller Frauen!

Gott Kama lauscht aus allen deinen Zügen,

Er wohnt in deines Busens weißen Zelten,

Und haucht aus dir die lieblichsten Gesänge;

Ich sah Wassant auf deinen Lippen liegen,

In deinem Aug’ entdeck ich neue Welten,

Und in der eignen Welt wird’s mir zu enge.

3

Der Ganges rauscht, der große Ganges schwillt,

Der Himalaja strahlt im Abendscheine,

Und aus der Nacht der Banianenhaine

Die Elefantenherde stürzt und brüllt –

Ein Bild! Ein Bild! Mein Pferd für’n gutes Bild!

Womit ich dich vergleiche, Schöne, Feine,

Dich Unvergleichliche, dich Gute, Reine,

Die mir das Herz mit heitrer Lust erfüllt!

Vergebens siehst du mich nach Bildern schweifen,

Und siehst mich mit Gefühl und Reimen ringen –

Und, ach! du lächelst gar ob meiner Qual!

Doch lächle nur! Denn wenn du lächelst, greifen

Gandarven nach der Zither, und sie singen

Dort oben in dem goldnen Sonnensaal.

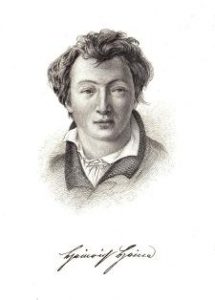

Heinrich Heine

(1797-1856)

Friedrike

1823

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Archive G-H, Heine, Heinrich

Peggy

My Peggy is a young thing,

Just enter’d in her teens,

Fair as the day, and sweet as May

Fair as the day, and always gay.

My Peggy is a young thing,

And I’m not very auld,

Yet well I like to meet her at

The Wawking of the Fauld.

My Peggy speaks sæ sweetly,

When’er we meet alane,

I wish næ mair to lay my care,

I wish næ mair of a’ that’s rare.

My Peggy speaks sæ sweetly,

To a’ the lave I’m cauld;

But she gars a’ my spirits glow

At Wawking of the Fauld.

My Peggy smiles sæ kindly,

Whene’er I whisper Love,

That I look down on a’ the Town,

That I look down upon a Crown.

My Peggy smiles sæ kindly,

It makes my blythe and bauld,

And naithing gi’es me sic delight,

As Wawking of the Fauld.

My Peggy sings sæ saftly,

When on my pipe I play;

By a’ the rest it is confest,

By a’ the rest, that she sings best.

My Peggy sings sæ saftly,

And in her songs are tald,

With innocence the wale of Sense,

At Wawking of the Fauld.

Allan Ramsay

(1684-1758)

Peggy

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: # Classic Poetry Archive, Archive Q-R, Archive Q-R

A Coat

I made my song a coat

Covered with embroideries

Out of old mythologies

From heel to throat;

But the fools caught it,

Wore it in the world’s eyes

As though they’d wrought it.

Song, let them take it,

For there’s more enterprise

In walking naked.

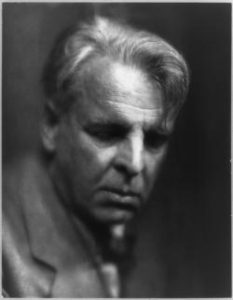

William Butler Yeats

(1865-1939)

A Coat

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive Y-Z, Archive Y-Z, Yeats, William Butler

Loud Shout

The Flaming Tongues of war

Ta’n Sionac Ar Sraidib Ag Faire Go Caocrac

Air—“The West’s Asleep.”

Loud shout the flaming tongues of war.

The cannon’s thunder rolls afar

While Empires tremble for their fall.

Thou art alone amongst them all.

Where is the friend who for thy sake

Will on his sword thy freedom take?

The son who holds thy right alone

Above an Empire or a throne?

Ah, Grannia Wael, thy stricken head

Is bowed in sorrow o’er thy dead,

Thy dead who died for love of thee,

Not for some foreign liberty.

Shall we betray when hope is near,

Our Motherland whom we hold dear,

To go to fight on foreign strand,

For foreign rights and foreign land?

The Lion’s fangs have sought to kill

A Nation’s soul, a Nation’s will;

From tooth and claw thy wounded breast

Has held them safe, has held them blest.

About thy head great eagles are,

They fly with scream and storm of war,

Their shadows fall, we do not know

If they be friend,—if they be foe.

For Lion’s roar we have no fears,

We fought him down the restless years.

We watch the Eagles in the sky,

Lest they should land—or pass us by.

But, yet beware! the Lion goes

To strike our friends—to charm our foes.

By hamlet small, by hill and dale

The creeping foe is on our trail;

His face is kind, his voice is bland,

He prates of faith and fatherland;

Shall we go forth to die and die

For Belgium’s tear, and Serbia’s sigh?

Oh, Volunteers, through field and town

He seeks his prey, he tracks thee down

His voice is soft, his words are fair,

It is the creeping foe, Beware!

Ah, Grannia Wael, in blood and tears

We fought thy battles through the years,

That thou shouldst live we’re glad to die

In prison cell or gallows high.

Oh, cursed be he ! who to our shame

Drives forth thy manhood in thy name,

O, WHILE THE LION LAPS YOUR BLOOD

SHALL WE UNITE IN SERVITUDE.

Dora Maria Sigerson Shorter

(1866 – 1918)

Loud Shout The Flaming Tongues of war

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Archive S-T, Sigerson Shorter, Dora Maria, WAR & PEACE

Kruisiging in schermopdeling

Mulier, ecce filius tuus … Ecce mater tua.

I

Dismas spreekt naar links. Gestas weigert nors

de bekoring van bekering. Willen die geschieden

gaan hem voorbij in de vaart van het duister. O,

ontraadseling: veel kleiner dan de lucht is huid.

II

Nog maar onlangs was Hij timmermanskind,

glimlachend jong. Nu vertrouwt Hij in Zijn

laatste strijd en nakend onweder de leerling

Zijn moeder, en haar hem toe. Maria’s wenen.

III

Nabij het Schedelveld verschieten hogepriesters

en tollenaren in hun gewaden vol verraad als het

bliksemt, de aarde trilt. Ze erkennen hun nederlaag

wel maar wensen er die naam niet aan te geven.

Bert Bevers

Kruisiging in schermopdeling

Verschenen in Kruiswoorden in Poëziepuntgl, Oosterbeek, 2017

Bert Bevers is dichter en schrijver

Hij woont en werkt in Antwerpen (Be)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Bevers, Bert

Ferdinand, le héros de Guerre, a quitté la France pour rejoindre Londres, « où viennent fatalement un jour donné se dissimuler toutes les haines et tous les accents drôles ».

Il y retrouve son amie prostituée Angèle, désormais en ménage avec le major anglais Purcell. Ferdinand prend domicile dans une mansarde de Leicester Pension, où le dénommé Cantaloup, un maquereau de Montpellier, organise un intense trafic sexuel de filles, avec quelques autres personnages hauts en couleur, dont un policier, Bijou, et un ancien poseur de bombes, Borokrom.

Il y retrouve son amie prostituée Angèle, désormais en ménage avec le major anglais Purcell. Ferdinand prend domicile dans une mansarde de Leicester Pension, où le dénommé Cantaloup, un maquereau de Montpellier, organise un intense trafic sexuel de filles, avec quelques autres personnages hauts en couleur, dont un policier, Bijou, et un ancien poseur de bombes, Borokrom.

Proxénétisme, alcoolisme, trafic de poudre, violences et irrégularités en tout genre rendent chaque jour plus suspecte cette troupe de sursitaires déjantés, hantés par l’idée d’être envoyés ou renvoyés au front.

S’il entretient des liens avec Guignol’s band, l’autre roman anglais plus tardif de Céline, Londres, établi depuis le manuscrit récemment retrouvé, s’impose avec puissance comme le grand récit d’une double vocation : celle de la médecine et de l’écriture… Ou comment se tenir au plus près de la vérité des hommes, plongé dans cette farce outrancière et mensongère qu’est la vie.

Louis-Ferdinand Céline

Né en 1894 à Courbevoie, près de Paris, Louis-Ferdinand Céline (pseudonyme de L.-F. Destouches) prépare seul son baccalauréat tout en travaillant. Engagé en 1912, il est gravement blessé en novembre 1914. Invalide à 75 % et réformé, il devient agent commercial et part au Cameroun (1916), puis à Londres (1917).

Après la Victoire, il fait des études de médecine, puis accomplit des missions en Afrique et aux États-Unis pour le compte de la Société des Nations. De retour en France, il exerce la médecine dans la banlieue parisienne et publie en 1932 son premier ouvrage Voyage au bout de la nuit, suivi, en 1936, de Mort à crédit.

De 1944 à 1951, Céline, exilé, vit en Allemagne et au Danemark. Revenu en France, il s’installe à Meudon où il poursuit son œuvre (D’un château l’autre, Nord, Rigodon) et continue à soigner essentiellement les pauvres. Il meurt en 1961.

Louis-Ferdinand Céline

Londres

Édition de Regis Tettamanzi

Collection Blanche, Gallimard

Parution : 13-10-2022

576 pages

Grand format: 140 x 205 mm

Littérature française

Époque : XXe siècle

ISBN : 9782072983375

Gencode : 9782072983375

Code distributeur : G06460

€ 24.00

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive C-D, Louis-Ferdinand Céline

Parmi les manuscrits de Louis-Ferdinand Céline récemment retrouvés figurait une liasse de deux cent cinquante feuillets révélant un roman dont l’action se situe dans les Flandres durant la Grande Guerre.

Avec la transcription de ce manuscrit de premier jet, écrit quelque deux ans après la parution de Voyage au bout de la nuit (1932), une pièce capitale de l’œuvre de l’écrivain est mise au jour. Car Céline, entre récit autobiographique et œuvre d’imagination, y lève le voile sur l’expérience centrale de son existence : le traumatisme physique et moral du front, dans l’« abattoir international en folie ».

Avec la transcription de ce manuscrit de premier jet, écrit quelque deux ans après la parution de Voyage au bout de la nuit (1932), une pièce capitale de l’œuvre de l’écrivain est mise au jour. Car Céline, entre récit autobiographique et œuvre d’imagination, y lève le voile sur l’expérience centrale de son existence : le traumatisme physique et moral du front, dans l’« abattoir international en folie ».

On y suit la convalescence du brigadier Ferdinand depuis le moment où, gravement blessé, il reprend conscience sur le champ de bataille jusqu’à son départ pour Londres. À l’hôpital de Peurdu-sur-la-lys, objet de toutes les attentions d’une infirmière entreprenante, Ferdinand, s’étant lié d’amitié au souteneur Bébert, trompe la mort et s’affranchit du destin qui lui était jusqu’alors promis.

Ce temps brutal de la désillusion et de la prise de conscience, que l’auteur n’avait jamais abordé sous la forme d’un récit littéraire autonome, apparaît ici dans sa lumière la plus crue. Vingt ans après 14, le passé, « toujours saoul d’oubli », prend des « petites mélodies en route qu’on lui demandait pas ». Mais il reste vivant, à jamais inoubliable, et Guerre en témoigne tout autant que la suite de l’œuvre de Céline.

Louis-Ferdinand Céline

Né en 1894 à Courbevoie, près de Paris, Louis-Ferdinand Céline (pseudonyme de L.-F. Destouches) prépare seul son baccalauréat tout en travaillant. Engagé en 1912, il est gravement blessé en novembre 1914. Invalide à 75 % et réformé, il devient agent commercial et part au Cameroun (1916), puis à Londres (1917).

Après la Victoire, il fait des études de médecine, puis accomplit des missions en Afrique et aux États-Unis pour le compte de la Société des Nations. De retour en France, il exerce la médecine dans la banlieue parisienne et publie en 1932 son premier ouvrage Voyage au bout de la nuit, suivi, en 1936, de Mort à crédit.

De 1944 à 1951, Céline, exilé, vit en Allemagne et au Danemark. Revenu en France, il s’installe à Meudon où il poursuit son œuvre (D’un château l’autre, Nord, Rigodon) et continue à soigner essentiellement les pauvres. Il meurt en 1961.

Louis-Ferdinand Céline

Guerre

Édition de Pascal Fouché.

Avant-propos de François Gibault

Collection Blanche, Gallimard

Parution : 05-05-2022

192 pages

ill.

140 x 205 mm

Littérature française

Époque: XXe siècle

ISBN: 9782072983221

Gencode: 9782072983221

Code distributeur: G06457

€ 19,00

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive C-D, Louis-Ferdinand Céline

Au bois dormant

La princesse, dans un palais de rose pure,

Sous les murmures, sous la mobile ombre dort,

Et de corail ébauche une parole obscure

Quand les oiseaux perdus mordent ses bagues d’or.

Elle n’écoute ni les gouttes, dans leurs chutes,

Tinter d’un siècle vide au lointain le trésor,

Ni, sur la forêt vague, un vent fondu de flûtes

Déchirer la rumeur d’une phrase de cor.

Laisse, longue, l’écho rendormir la diane,

Ô toujours plus égale à la molle liane

Qui se balance et bat tes yeux ensevelis.

Si proche de ta joue et si lente la rose

Ne va pas dissiper ce délice de plis

Secrètement sensible au rayon qui s’y pose.

Paul Valéry

(1871-1945)

Au bois dormant

Poème

Album de vers anciens

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive U-V, Archive U-V, Valéry, Paul

Eeuwenhout

(Een droom)

Is het valsheid in geschrifte wanneer ik

uit vannacht noteer dat waar de paarden

graasden het gras weerbarstig was?

Streelde daar bij Eeuwenhout hun manen,

kende niet hun namen maar ze roken naar

de weergalm van gebeden uit een oude tijd.

Vervolgens stak ik langs diens linkerzijde

traag een heel lang mes het hart in van een

stille, vreemde man. Amper zat er bloed

aan toen ik het terugtrok. Hoe merkwaardig.

Je zou denken dat het er van druipen zou.

Wat smaakte even later toch het bier me goed.

Bert Bevers

Eeuwenhout (Een droom)

Verschenen in het Droomnummer van Gierik & NVT, Antwerpen, 2017

Bert Bevers is dichter en schrijver

Hij woont en werkt in Antwerpen (Be)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Bevers, Bert

Vereinsamt

I. Die Krähen schrei’n

Die Krähen schrein

Und ziehen schwirren Flugs zur Stadt:

Bald wird es schnein. –

Wohl dem, der jetzt noch Heimat hat!

Nun stehst du starr,

Schaust rückwärts, ach! wie lange schon!

Was bist Du Narr

Vor Winters in die Welt entflohn?

Die Welt – ein Tor

Zu tausend Wüsten stumm und kalt!

Wer das verlor,

Was du verlorst, macht nirgends halt.

Nun stehst du bleich,

Zur Winter-Wanderschaft verflucht,

Dem Rauche gleich,

Der stets nach kältern Himmeln sucht.

Flieg, Vogel, schnarr

Dein Lied im Wüstenvogel-Ton! –

Versteck, du Narr,

Dein blutend Herz in Eis und Hohn!

Die Krähen schrein

Und ziehen schwirren Flugs zur Stadt:

Bald wird es schnein. –

Weh dem, der keine Heimat hat.

II. Antwort

Daß Gott erbarm’!

Der meint, ich sehnte mich zurück

In’s deutsche Warm.

In’s dumpfe deutsche Stuben-Glück!

Mein Freund, was hier

Mich hemmt und und hält, ist dein Verstand,

Mitleid mit dir!

Mitleid mit deutschem Quer-Verstand!

Friedrich Nietzsche

(1844 – 1900)

Vereinsamt

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive M-N, Archive M-N, Friedrich Nietzsche, Nietzsche

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature