Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Frost at Midnight

The Frost performs its secret ministry,

Unhelped by any wind. The owlet’s cry

Came loud, -and hark, again! loud as before.

The inmates of my cottage, all at rest,

Have left me to that solitude, which suits

Abstruser musings: save that at my side

My cradled infant slumbers peacefully.

‘Tis calm indeed! so calm, that it disturbs

And vexes meditation with its strange

And extreme silentness. Sea, hill, and wood,

With all the numberless goings-on of life,

Inaudible as dreams! the thin blue flame

Lies on my low-burnt fire, and quivers not;

Only that film, which fluttered on the grate,

Still flutters there, the sole unquiet thing.

Methinks its motion in this hush of nature

Gives it dim sympathies with me who live,

Making it a companionable form,

Whose puny flaps and freaks the idling Spirit

By its own moods interprets, every where

Echo or mirror seeking of itself,

And makes a toy of Thought.

But O! how oft,

How oft, at school, with most believing mind,

Presageful, have I gazed upon the bars,

To watch that fluttering stranger! and as oft

With unclosed lids, already had I dreamt

Of my sweet birthplace, and the old church-tower,

Whose bells, the poor man’s only music, rang

From morn to evening, all the hot Fair-day,

So sweetly, that they stirred and haunted me

With a wild pleasure, falling on mine ear

Most like articulate sounds of things to come!

So gazed I, till the soothing things, I dreamt,

Lulled me to sleep, and sleep prolonged my dreams!

And so I brooded all the following morn,

Awed by the stern preceptor’s face, mine eye

Fixed with mock study on my swimming book:

Save if the door half opened, and I snatched

A hasty glance, and still my heart leaped up,

For still I hoped to see the stranger’s face,

Townsman, or aunt, or sister more beloved,

My playmate when we both were clothed alike!

Dear Babe, that sleepest cradled by my side,

Whose gentle breathings, heard in this deep calm,

Fill up the interspersed vacancies

And momentary pauses of the thought!

My babe so beautiful! it thrills my heart

With tender gladness, thus to look at thee,

And think that thou shalt learn far other lore,

And in far other scenes! For I was reared

In the great city, pent mid cloisters dim,

And saw nought lovely but the sky and stars.

But thou, my babe! shalt wander like a breeze

By lakes and sandy shores, beneath the crags

Of ancient mountain, and beneath the clouds,

Which image in their bulk both lakes and shores

And mountain crags: so shalt thou see and hear

The lovely shapes and sounds intelligible

Of that eternal language, which thy God

Utters, who from eternity doth teach

Himself in all, and all things in himself.

Great universal Teacher! he shall mould

Thy spirit, and by giving make it ask.

Therefore all seasons shall be sweet to thee,

Whether the summer clothe the general earth

With greenness, or the redbreast sit and sing

Betwixt the tufts of snow on the bare branch

Of mossy apple-tree, while the nigh thatch

Smokes in the sun-thaw; whether the eave-drops fall

Heard only in the trances of the blast,

Or if the secret ministry of frost

Shall hang them up in silent icicles,

Quietly shining to the quiet Moon.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772 – 1834)

Frost at Midnight

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Coleridge, Coleridge, Samuel Taylor

Anne Finch

Adam Posed

Could our first father, at his toilsome plow,

Thorns in his path, and labor on his brow,

Clothed only in a rude, unpolished skin,

Could he a vain fantastic nymph have seen,

In all her airs, in all her antic graces,

Her various fashions, and more various faces;

How had it posed that skill, which late assigned

Just appellations to each several kind!

A right idea of the sight to frame;

T’have guessed from what new element she came;

T’have hit the wav’ring form, or giv’n this thing a name.

Anne Finch (1661 – 1720)

Adam Posed

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive E-F, CLASSIC POETRY

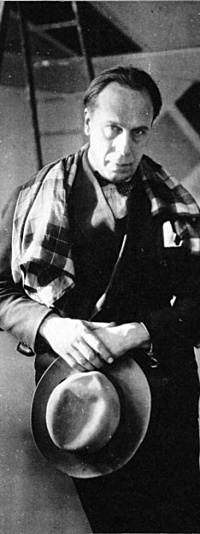

Robert Desnos

Coucher avec elle

Coucher avec elle

Pour le sommeil côte à côte

Pour les rêves parallèles

Pour la double respiration

Coucher avec elle

Pour l’ombre unique et surprenante

Pour la même chaleur

Pour la même solitude

Coucher avec elle

Pour l’aurore partagée

Pour le minuit identique

Pour les mêmes fantômes

Coucher coucher avec elle

Pour l’amour absolu

Pour le vice, pour le vice

Pour les baisers de toute espèce

Coucher avec elle

Pour un naufrage ineffable

Pour se prouver et prouver vraiment

Que jamais n’a pesé sur l’âme et le corps des amants

Le mensonge d’une tache originelle

Robert Desnos (1900 – 1945)

Poème: Coucher avec elle, 1942

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Desnos, Robert

De internationaal bekroonde kunstenaar Fiona Tan (Indonesia, 1966) is een goede bekende van museum De Pont, waar ze in 2003 haar eerste grote tentoonstelling in Nederland kreeg en ook ruim vertegenwoordigd is in de collectie.

De internationaal bekroonde kunstenaar Fiona Tan (Indonesia, 1966) is een goede bekende van museum De Pont, waar ze in 2003 haar eerste grote tentoonstelling in Nederland kreeg en ook ruim vertegenwoordigd is in de collectie.

Haar tweede tentoonstelling in Tilburg, in de onlangs geopende nieuwe vleugel van het museum, biedt de bezoeker een meeslepende audiovisuele ervaring. Hier is de tweedelige installatie Ascent te zien die Tan maakte in opdracht van het Izu Photo Museum in Shizuoka, Japan. Ascent is samengesteld als een montage van meer dan 4000 foto’s van de berg Fuji die werden aangeleverd door het publiek of geselecteerd uit de collectie van het Izu Photo Museum.

Geen berg is zo vaak gefotografeerd als de Fuji: van alle kanten, van dichtbij, van veraf en van boven, op elk moment van de dag en in elk jaargetijde. Vereerd als een god en ingezet als symbool van Japan als natiestaat heeft de vulkaan mythische betekenis. Mount Fuji is icoon én cliché, zoiets als molens en klompen voor Nederland.

Ascent is een bespiegeling over deze voor de Japanners zo bijzondere berg, maar ook een studie van de beeldcultuur en een eerbetoon aan de geschiedenis van zowel fotografie als film.

Tan combineerde de beelden met een fictief verhaal, waarmee de grens tussen stilstaand en bewegend beeld wordt verlegd en zij een uniek gebied blootlegt waar fotografie en film elkaar ontmoeten en een verbinding aangaan. Het verhaal, waarin de klim naar de top van de berg weerklinkt, zigzagt tussen vertelling en geschiedenis, van westers imperialisme tot hedendaags toerisme, van de beginjaren van de fotografie tot de huidige tijd. Behalve de film omvat de tentoonstelling in De Pont ook twee andere video installaties en daarmee verbonden werken op papier. The Changeling (2006) en Depot (2015) balanceren eveneens op de grens tussen stilstaande en bewegende beelden.

Fiona Tan:

Ascent

tot en met 11 juni 2017

Museum De Pont Tilburg

Wilhelminapark 1

5041 EA Tilburg

T 013 – 543 8300

# Meer informatie op website Museum De Pont Tilburg

february 2017

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Art & Literature News, AUDIO, CINEMA, RADIO & TV, DICTIONARY OF IDEAS, Exhibition Archive, FDM Art Gallery, Photography, Spurensicherung

Sérgio Monteiro de Almeida

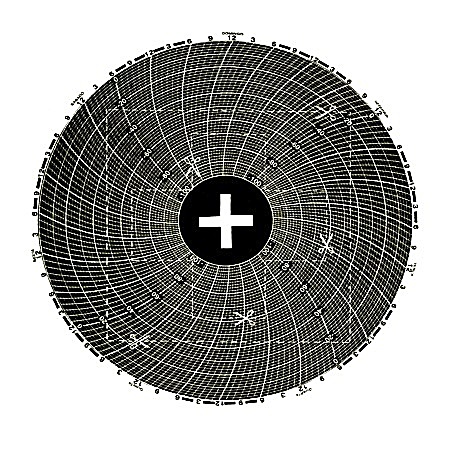

Poema visual

A Cruz q carrego

Sérgio Monteiro de Almeida cv:

Curitiba, Brazil (1964). Intermedia visual poet and conceptual artist. – He has published in numerous anthologies and specialized magazines in Brazil and outside; participated in exhibitions of visual poetry as International Biennial of Visual and Alternative Poetry in Mexico (editions from 1987 to 2010); Post-Art International Exhibition of Visual / Experimental Poetry, San Diego State University-USA (1988); 51 and 53 Venice Biennial (2005 and 2009). – He published in 2007 the book Sérgio Monteiro de Almeida with a global vision about his work as a visual artist and poet. – This book was incorporated into the “Artist Books” collection of the New York City Library (USA). – Author of the CD of kinetic visual poems (EU) NI/IN VERSO (still unpublished). – He presented urban interventions in Curitiba, San Diego, Seattle, New York, Paris, Rome. – In 2014 and 2015 visual poems published in the Rampike experimental literature magazine of the University of Windsor, Canada. – He recently had his poems published in Jornal Candido (n. 64) and Relevo (2015 and 2016).

More about his work:

Livro eletrônico http://issuu.com/boek861/docs/sergio_monteiro_libro;

Enciclopédia Itaú Cultural de artes visuais www.itaucultural.com.br;

Videos no Youtube: http://www.youtube.com/user/SergioMAlmeida

Sérgio Monteiro de Almeida

Curitiba – PR – Brazil

email: sergio.ma@ufpr.br

february 2017

magazine fleursdumal.nl

More in: Archive M-N, Sérgio Monteiro de Almeida

What must be said

You cannot believe it possible to say

What must be said—words being

So few and dry, catchwords,

‘Your journey, our worldview’,

So hostile to living intent.

But you find the words without searching,

As at need, and they have a beauty,

As, once in a while, the desert,

At the touch of rain, is starred

Endlessly with small white flowers.

John Leonard

John Leonard Writer’s CV:

1965: Born, Cambridge, UK

1984-87: Read English at Oxford University, UK

1990: Unlove (poems) published in UK

1991: Emigrated to Australia

1991-94: PhD studies at University of Queensland; ‘Lyric and Modernity’ awarded 1995

1997: 100 Elegies for Modernity (poems, Sydney, Hale and Iremonger)

2003: Jesus in Kashmir (poems, Canberra, Proensa)

2003-07: Poetry Editor, Overland (Melbourne)

2009: Poem published in Best Australian Poetry 2009 (Melbourne, Black Inc)

2010: Braided Lands (poems, Ginninderra Press, Adelaide)

2010: The Way of Poetry (criticism linking poetry and Daoism; Three Pines Press, Dunedin, Florida) (see www.threepinespress.com, under ‘Dao Today’ tab)

2014: A Spell, A Charm (poems, Melbourne, Hybrid Publishers

Poetry widely published in quality journals, eg Overland, Meanjin, Island

Poems translated into French, Spanish, Croatian and Chinese and published in those versions, eg When the Moon Is Swimming Naked: Australasian Poetry for the Chinese Youngster, Ed Kit Kelen and Mark Carthew, ASM Poetry, Association of Stories in Macao, 2013 (8 poems), http://poetassigloveintiuno.blogspot.com.au/2012/07/7271-john-leonard.html (5 poems)&c

Poems published in anthologies eg The Best Australian Poems 2009, (Melbourne, Black Inc), The Turnrow Anthology of Contemporary Australian Poetry 2014, Canberra Poets Anthology 2014

Website: www.jleonard.net

february 2017

magazine fleursdumal.nl

More in: Archive K-L, Leonard, John

Het themajaar Mondriaan tot Dutch Design begint in Museum Dr8888 op 29 januari 2017 met de tentoonstelling César Domela, De Stijl in kunst en typografie. César Domela Nieuwenhuis (1900-1992) was graficus, fotograaf, typograaf, edelsmid en lid van kunstbeweging De Stijl. Hij heeft een belangrijke bijdrage geleverd aan de kunstbeweging door de introductie van reliëfs en door elementen uit De Stijl en constructivisme toe te passen op de vormgeving van advertenties en typografie. Hij was de jongste zoon van politicus en grondlegger van de socialistische beweging in Nederland, Ferdinand Domela Nieuwenhuis (1846-1919). De herinnering aan Ús Ferlosser, zoals deze laatste door de Friezen in de Zuidoosthoek genoemd wordt, wordt levend gehouden in Museum Heerenveen.

Het themajaar Mondriaan tot Dutch Design begint in Museum Dr8888 op 29 januari 2017 met de tentoonstelling César Domela, De Stijl in kunst en typografie. César Domela Nieuwenhuis (1900-1992) was graficus, fotograaf, typograaf, edelsmid en lid van kunstbeweging De Stijl. Hij heeft een belangrijke bijdrage geleverd aan de kunstbeweging door de introductie van reliëfs en door elementen uit De Stijl en constructivisme toe te passen op de vormgeving van advertenties en typografie. Hij was de jongste zoon van politicus en grondlegger van de socialistische beweging in Nederland, Ferdinand Domela Nieuwenhuis (1846-1919). De herinnering aan Ús Ferlosser, zoals deze laatste door de Friezen in de Zuidoosthoek genoemd wordt, wordt levend gehouden in Museum Heerenveen.

Over de tentoonstelling: Museum Dr8888 toont een dwarsdoorsnede van deze duizendpoot: van zijn ontwerpen voor tijdschriften tot zijn reliëfs. Naast werken van César Domela zijn op de tentoonstelling werken te zien van collega-kunstenaars Theo van Doesburg en Thijs Rinsema,  alsmede Piet Zwart, Jac Jongert en andere vormgevers en typografen die zowel door het constructivisme als De Stijl zijn beïnvloed.

alsmede Piet Zwart, Jac Jongert en andere vormgevers en typografen die zowel door het constructivisme als De Stijl zijn beïnvloed.

César Domela, De Stijl in kunst en typografie is de eerste van vier tentoonstellingen die het museum in het kader van de landelijke viering van 100 jaar De Stijl organiseert. Naast Museum Dr8888 doen ook Keramiekmuseum Princessehof Leeuwarden en de voormalig Rijksluchtvaartschool in Eelde als vertegenwoordigers van Noord-Nederland mee aan het themajaar Mondriaan tot Dutch Design.

César Domela, De Stijl in kunst en typografie

(29 januari – 2 april 2017)

Dr8888

Museum Drachten

Museumplein 2

Drachten 9203 DD

tel. 0512 515 647

# Meer informatie op website Dr8888

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Art & Literature News, César Domela, Constructivism, De Stijl, Exhibition Archive, FDM Art Gallery, Piet Mondriaan, Piet Mondriaan, Theo van Doesburg, Theo van Doesburg

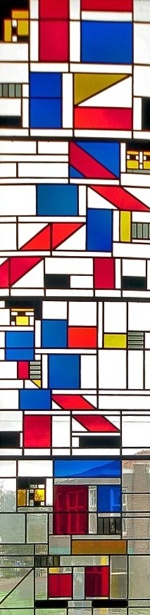

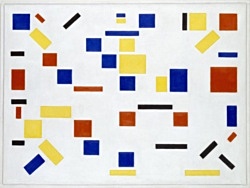

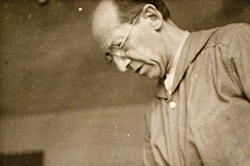

Rondom 1920 vinden de nieuwe kunststromingen De Stijl en Dada hun weg naar Drachten door een bijzondere vriendschap tussen architect en schilder Theo van Doesburg en twee broers uit Drachten: Evert en Thijs Rinsema.

Rondom 1920 vinden de nieuwe kunststromingen De Stijl en Dada hun weg naar Drachten door een bijzondere vriendschap tussen architect en schilder Theo van Doesburg en twee broers uit Drachten: Evert en Thijs Rinsema.

Theo van Doesburg

Theo van Doesburg is een van de oprichters van De Stijl, een belangrijke avant-garde beweging in Europa. De Stijl omvat een groep kunstenaars die nieuwe eisen stelt aan alle vormen van kunst, maar vooral aan architectuur. Uitgangspunt is dat vorm en materiaal worden teruggebracht tot de meeste elementaire constructie. Kleur wordt gebruikt om de lijnen van de architectuur te doorbreken en om een evenwicht te brengen tussen horizontaal en verticaal.

Gebroeders Rinsema

Gebroeders Rinsema

Evert Rinsema is dichter. In 1920 verschijnen zijn aforismen ‘Verzamelde volzinnen’ als uitgave van De Stijl. Thijs Rinsema is schilder. Hij schildert het liefst eenvoudige alledaagse voorwerpen die hij modelleert naar de principes van het kubisme en De Stijl. Thijs is net als zijn broer Evert autodidact. Evert en Thijs Rinsema leren de Duitse dadaïst Kurt Schwitters kennen via Theo van Doesburg. In het voorjaar van 1923 staat er een kleine advertentie in de Drachtster Courant met de tekst: ‘Een Dada avond, door K. Schwitters, vrijdag 13 april, 8 uur ’s avonds, entree Fl. 1,-. De Phoenix in Drachten’. Het is een kleine maar opvallende advertentie, die net als het Dada-affiche van Van Doesburg, is gedrukt in een mengeling van hoofdletters en kleine letters. Die avond klinkt de Ur-sonate van Kurt Schwitters.

Door de vriendschap met de gebroeders Rinsema komt Theo van Doesburg in contact met de gemeente-architect Cees Rienks de Boer. Theo van Doesburg ontwerpt voor 16 middenstandswoningen aan de Torenstraat en de Landbouwwinterschool een kleuroplossing. Ook ontwerpt Van Doesburg op verzoek van De Boer glas-in-loodramen voor de Christelijke ULO en de Landbouwwinterschool.

Museum Dr8888

Museum Dr8888 bezit een belangrijke verzameling werken van deze roemruchte avant-gardestromingen van de 20ste eeuw. Deze collectie mag zich tegenwoordig ook verheugen in internationale belangstelling. In 2009 en 2010 waren een groot aantal werken van Van Doesburg en Schwitters te zien in exposities in de Tate Modern in Londen en Centre Pompidou in Parijs.

100 jaar De Stijl

In 2017 is het honderd jaar geleden dat de Nederlandse kunstbeweging De Stijl is opgericht. Nederland viert dit met het themajaar Mondriaan tot Dutch Design. 100 jaar De Stijl. Gedurende het hele jaar vinden er door heel Nederland tal van inspirerende tentoonstellingen en evenementen plaats. Van 29 januari t/m 2 april 2017 vindt de eerste grote tentoonstelling in het kader van 100 jaar de Stijl plaats in Museum Dr8888: César Domela, De Stijl in kunst en typografie. Naast Museum Dr8888 doen ook Keramiekmuseum Princessehof Leeuwarden en de voormalig Rijksluchtvaartschool in Eelde als vertegenwoordigers van Noord-Nederland mee.

Exposities Museum Dr8888 in 2017

César Domela: De Stijl in kunst en typografie

César Domela: De Stijl in kunst en typografie

28 januari – 2 april 2017

César Domela was een Nederlands kunstschilder, graficus, fotograaf, typograaf en lid van kunstbeweging De Stijl. Museum Dr8888 toont een dwarsdoorsnede van het werk van deze creatieve duizendpoot.

De Stijl in Drachten: Theo van Doesburg, kleur in architectuur

16 april – 25 juni 2017

Deze tentoonstelling bestaat uit o.a. kleurontwerpen, glas-in-loodramen, schilderijen en poëzie van kunstenaars als Theo van Doesburg, Thijs Rinsema en Evert Rinsema. Bijna alle ontwerpen van Theo van Doesburg in Drachten voor het eerst bij elkaar te zien.

De Stijl en expressionisme in de tropen: Sandberg, Rietveld, Chris en Lucila Engels op Curaçao

9 juli 2017 – 17 september 2017

Expositie van de projecten die Gerrit Rietveld heeft uitgevoerd op Curaçao. Daar heeft hij o.a. het interieur van Villa Stroomzigt mede ontworpen en een tehuis voor kinderen met een beperking. Daarnaast een uitgebreide selectie werken uit de collectie van kunstenaarsechtpaar Chris en Lucila Engels en hun adviseur en vriend Willem Sandberg.

Museum Dr8888 en RLS Eelde: De Stijl & constructivisme in Noord-Nederland

Museum Dr8888 en RLS Eelde: De Stijl & constructivisme in Noord-Nederland

30 september 2017- 7 januari 2018

Een overzicht van (Stijl)kunstenaars die actief waren tijdens het Interbellum in Noord-Nederland, maar ook hedendaagse kunstenaars uit die zich laten inspireren door De Stijl en het constructivisme. In Drachten ligt het accent op De Stijl in ontwerp en architectuur. In RLS Eelde hedendaagse kunst geïnspireerd op De Stijl en constructivisme, met o.a. Jan van der Ploeg en Krijn de Koning.

Dada & 100 jaar Kunstbeweging DE STIJL in Museum Dr8888

Vier exposities in 2017

Museum Drachten (Dr8888)

Museumplein 2

Drachten 9203 DD

tel. 0512 515 647

# Meer informatie op website Dr8888

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Antony Kok, Art & Literature News, Bauhaus, Bauhaus, César Domela, Constructivism, Constuctivisme, Dada, Dadaïsme, De Ploeg, De Stijl, Design, Doesburg, Theo van, Dutch Landscapes, Evert en Thijs Rinsema, Exhibition Archive, FDM Art Gallery, Futurism, Futurisme, Gerrit Rietveld, Gerrit Rietveld, Kok, Antony, Kubisme, Kurt Schwitters, Kurt Schwitters, Piet Mondriaan, Piet Mondriaan, Schwitters, Kurt, Theo van Doesburg, Theo van Doesburg, Werkman, Hendrik Nicolaas

Novalis

Letzte Liebe

Also noch ein freundlicher Blick am Ende der Wallfahrt,

Ehe die Pforte des Hains leise sich hinter mir schließt.

Dankbar nehm ich das Zeichen der treuen Begleiterin Liebe

Fröhlichen Mutes an, öffne das Herz ihr mit Lust.

Sie hat mich durch das Leben allein ratgebend geleitet,

Ihr ist das ganze Verdienst, wenn ich dem Guten gefolgt,

Wenn manch zärtliches Herz dem Frühgeschiedenen nachweint

Und dem erfahrenen Mann Hoffnungen welken mit mir.

Noch als das Kind, im süßen Gefühl sich entfaltender Kräfte,

Wahrlich als Sonntagskind trat in den siebenten Lenz,

Rührte mit leiser Hand den jungen Busen die Liebe,

Weibliche Anmut schmückt jene Vergangenheit reich.

Wie aus dem Schlummer die Mutter den Liebling weckt mit dem Kusse,

Wie er zuerst sie sieht und sich verständigt an ihr:

Also die Liebe mit mir – durch sie erfuhr ich die Welt erst,

Fand mich selber und ward, was man als Liebender wird.

Was bisher nur ein Spiel der Jugend war, das verkehrte

Nun sich in ernstes Geschäft, dennoch verließ sie mich nicht

Zweifel und Unruh suchten mich oft von ihr zu entfernen,

Endlich erschien der Tag, der die Erziehung vollzog,

Welcher mein Schicksal mir zur Geliebten gab und auf ewig

Frei mich gemacht und gewiß eines unendlichen Glücks.

Novalis (1772 – 1801)

Gedicht: Letzte Liebe

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive M-N, Novalis, Novalis

Eén van de scherpzinnigste en opvallendste hedendaagse auteurs doet na diepgaand onderzoek verslag van de laatste levensdagen van Susan Sontag, Sigmund Freud, John Updike, Dylan Thomas, Maurice Sendak en James Salter. Het levert een aantal fascinerende en uiterst originele overwegingen op over de eindigheid van het leven.

Eén van de scherpzinnigste en opvallendste hedendaagse auteurs doet na diepgaand onderzoek verslag van de laatste levensdagen van Susan Sontag, Sigmund Freud, John Updike, Dylan Thomas, Maurice Sendak en James Salter. Het levert een aantal fascinerende en uiterst originele overwegingen op over de eindigheid van het leven.

In Het uur van het violet kiest Katie Roiphe voor een onverwachte en bevrijdende benadering van een onderwerp waar niemand omheen kan. Ze gaat na hoe de laatste levensdagen waren van zes grote denkers, schrijvers en kunstenaars en hoe zij omgingen met de realiteit van de naderende dood, of, zoals T.S. Eliot het noemde: ‘het avondlijk uur dat Huiswaarts gericht is en de zeeman thuisbrengt’.

We maken kennis met Susan Sontag, die, wanneer ze voor de derde keer de strijd tegen kanker aangaat, worstelt met haar engagement met het rationele denken. Roiphe neemt ons mee naar de kamer in het ziekenhuis waar de 76-jarige John Updike, nadat hem de slechtst mogelijke diagnose is meegedeeld, een gedicht begint te schrijven. Ze schept een levendig beeld van de twee weken durende, bijna suïcidaal overmatige inspanning die culmineerde in de totale instorting van Dylan Thomas in het Chelsea Hotel. Ze schetst voor ons een moedgevend portret van Sigmund Freud die, nadat hij het door de nazi’s bezette Wenen is ontvlucht, in zijn Londense ballingschap het dwangmatige roken van sigaren voortzet waarvan hij weet dat het zijn aftakeling zal verhaasten. En ze toont ons dat Maurice Sendaks geliefde kinderboeken doordesemd zijn van het feit dat hij zijn leven lang geobsedeerd was door de dood, al was dat niet altijd evident.

Het uur van het violet staat vol met intieme en verrassende onthullingen. In de laatste daden van al deze creatieve genieën worden we geconfronteerd met moed, passie, zelfbedrog, zinloos lijden en onovertroffen toewijding. Door de laatste levensdagen van deze grote auteurs te beschrijven in indrukwekkende, niet-sentimentele termen helpt Katie Roiphe ons om de dood moedig onder ogen te zien en er minder bang voor te zijn.

Katie Roiphe

Het uur van het violet

Grote schrijvers in hun laatste dagen

Vertaald uit het Engels door Anne Jongeling

Uitg. Hollands Diep

Paperback, 352 p.

ISBN: 9789048836420

€ 19.99 – Januari 2017

# Meer informatie op website Hollands Diep

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Art & Literature News, DEAD POETS CORNER, DICTIONARY OF IDEAS, Galerie des Morts, Susan Sontag, Thomas, Dylan, TOMBEAU DE LA JEUNESSE - early death: writers, poets & artists who died young

Rond het uitbreken van de Eerste Wereldoorlog waart er een vernieuwingsdrang door het neutrale Nederland. Kunstenaars willen de heersende traditie van gemeenschapskunst verder ontwikkelen, maar in een compleet nieuwe beeldtaal. De bruine bakstenen van de decoratieve architectuur van de populaire Amsterdamse School vinden zij ongeschikt voor de moderne wereld. Een aantal jonge kunstenaars en architecten propageert daarom een ver doorgevoerde abstractie. Alleen die kunst kan de moderne tijd inluiden en het leven transformeren tot kunst. Hun visie leidt tot de wereldwijd bekende kunst en architectuur van De Stijl. De Stijl vormt – samen met het Duitse Bauhaus – de invloedrijkste avant-gardebeweging uit de eerste helft van de twintigste eeuw.

Rond het uitbreken van de Eerste Wereldoorlog waart er een vernieuwingsdrang door het neutrale Nederland. Kunstenaars willen de heersende traditie van gemeenschapskunst verder ontwikkelen, maar in een compleet nieuwe beeldtaal. De bruine bakstenen van de decoratieve architectuur van de populaire Amsterdamse School vinden zij ongeschikt voor de moderne wereld. Een aantal jonge kunstenaars en architecten propageert daarom een ver doorgevoerde abstractie. Alleen die kunst kan de moderne tijd inluiden en het leven transformeren tot kunst. Hun visie leidt tot de wereldwijd bekende kunst en architectuur van De Stijl. De Stijl vormt – samen met het Duitse Bauhaus – de invloedrijkste avant-gardebeweging uit de eerste helft van de twintigste eeuw.

In 1917 begint het in eerste instantie allemaal met een tijdschrift. Schilder, dichter en criticus Theo van Doesburg verzamelt een aantal vernieuwende kunstenaars zoals Piet Mondriaan, Bart van der Leck en Vilmos Huszar die in het tijdschrift willen publiceren. Ook al denken zij op sommige punten anders over kunst, zij geloven allen dat abstracte kunst de weg vooruit is. In oktober 1917 verschijnt uiteindelijk het eerste nummer van De Stijl. Op de cover staat dat De Stijl een bijdrage wil leveren aan “de ontwikkeling van het nieuwe schoonheidsbewustzijn,” met als bedoeling “den modernen mensch ontvankelijk [te] maken voor het nieuwe in de Beeldende Kunst.” Niet alleen schilderkunst, beeldhouwkunst, literatuur en architectuur zijn daartoe in staat. Juist design, typografie, reclame-uitingen, verpakkingen en modeontwerpen zijn bepalend in het straatbeeld. In tegenstelling tot een beweging als Bauhaus, die gestandaardiseerde oplossingen nastreeft, houdt De Stijl wel altijd maatwerk en vakmanschap hoog in het vaandel. Iedere specifieke omgeving vraagt om specifieke oplossingen. De Stijl is als een groep jonge jongens, die de wereld willen bestormen; en verbeteren.

In 1917 begint het in eerste instantie allemaal met een tijdschrift. Schilder, dichter en criticus Theo van Doesburg verzamelt een aantal vernieuwende kunstenaars zoals Piet Mondriaan, Bart van der Leck en Vilmos Huszar die in het tijdschrift willen publiceren. Ook al denken zij op sommige punten anders over kunst, zij geloven allen dat abstracte kunst de weg vooruit is. In oktober 1917 verschijnt uiteindelijk het eerste nummer van De Stijl. Op de cover staat dat De Stijl een bijdrage wil leveren aan “de ontwikkeling van het nieuwe schoonheidsbewustzijn,” met als bedoeling “den modernen mensch ontvankelijk [te] maken voor het nieuwe in de Beeldende Kunst.” Niet alleen schilderkunst, beeldhouwkunst, literatuur en architectuur zijn daartoe in staat. Juist design, typografie, reclame-uitingen, verpakkingen en modeontwerpen zijn bepalend in het straatbeeld. In tegenstelling tot een beweging als Bauhaus, die gestandaardiseerde oplossingen nastreeft, houdt De Stijl wel altijd maatwerk en vakmanschap hoog in het vaandel. Iedere specifieke omgeving vraagt om specifieke oplossingen. De Stijl is als een groep jonge jongens, die de wereld willen bestormen; en verbeteren.

Na de Eerste Wereldoorlog waart er een vernieuwingsdrang door Nederland. Kunstenaars keren zich af van de traditionele kunst, zoals de Amsterdamse School en de Haagse School. In 1917 richt kunstenaar, architect en criticus Theo van Doesburg, samen met de Tilburgse dichter Antony Kok, het tijdschrift ‘De Stijl’ op, waarin kunstenaars, vormgevers en architecten hun vernieuwende ideeën over kunst kunnen publiceren. In een mum van tijd weet hij onder andere Gerrit Rietveld, Bart van der Leck en Vilmos Huszar aan het tijdschrift te verbinden. Een aantal van deze kunstenaars tekent later ook een Manifest. Ook Piet Mondriaan doet mee. Met zijn abstracte kunst, primaire kleuren en zwart-witte lijnenspel is hij het grote voorbeeld voor De Stijl. De kunstenaars, architecten en vormgevers geloven dat zij met innovatieve en abstracte kunst de samenleving kunnen moderniseren. Daarvoor moeten wel alle kunstvormen samenwerken; en alles om ons heen moet opnieuw worden vormgegeven. Van de meubels waarop we zitten. De huizen waarin we wonen. En de steden die we bouwen. Zo groeit De Stijl uit tot een internationale beweging vergelijkbaar met het latere Bauhaus.

Na de Eerste Wereldoorlog waart er een vernieuwingsdrang door Nederland. Kunstenaars keren zich af van de traditionele kunst, zoals de Amsterdamse School en de Haagse School. In 1917 richt kunstenaar, architect en criticus Theo van Doesburg, samen met de Tilburgse dichter Antony Kok, het tijdschrift ‘De Stijl’ op, waarin kunstenaars, vormgevers en architecten hun vernieuwende ideeën over kunst kunnen publiceren. In een mum van tijd weet hij onder andere Gerrit Rietveld, Bart van der Leck en Vilmos Huszar aan het tijdschrift te verbinden. Een aantal van deze kunstenaars tekent later ook een Manifest. Ook Piet Mondriaan doet mee. Met zijn abstracte kunst, primaire kleuren en zwart-witte lijnenspel is hij het grote voorbeeld voor De Stijl. De kunstenaars, architecten en vormgevers geloven dat zij met innovatieve en abstracte kunst de samenleving kunnen moderniseren. Daarvoor moeten wel alle kunstvormen samenwerken; en alles om ons heen moet opnieuw worden vormgegeven. Van de meubels waarop we zitten. De huizen waarin we wonen. En de steden die we bouwen. Zo groeit De Stijl uit tot een internationale beweging vergelijkbaar met het latere Bauhaus.

In 2017 is het honderd jaar geleden dat De Stijl is opgericht. Nederland viert dit met het feestjaar Mondriaan tot Dutch design. 100 jaar De Stijl. Met ’s werelds grootste Mondriaan-collectie – en tevens een van de grootste De Stijl-collecties – is het Gemeentemuseum het middelpunt van dit feestelijke jaar. Drie tentoonstellingen zetten de groep hemelbestormers op het erepodium dat zij verdienen. Op 11 februari trapt het museum af met een tentoonstelling over de ontstaansgeschiedenis van een nieuwe kunst die de wereld voorgoed heeft veranderd.

In 2017 is het honderd jaar geleden dat De Stijl is opgericht. Nederland viert dit met het feestjaar Mondriaan tot Dutch design. 100 jaar De Stijl. Met ’s werelds grootste Mondriaan-collectie – en tevens een van de grootste De Stijl-collecties – is het Gemeentemuseum het middelpunt van dit feestelijke jaar. Drie tentoonstellingen zetten de groep hemelbestormers op het erepodium dat zij verdienen. Op 11 februari trapt het museum af met een tentoonstelling over de ontstaansgeschiedenis van een nieuwe kunst die de wereld voorgoed heeft veranderd.

In de mode of de vormgeving van magazines. Op verpakkingen, in advertenties of in videoclips. De kleurencombinatie van rood, geel en blauw die De Stijl iconische status heeft gegeven, is nog steeds heel geliefd. Maar wie heeft deze kenmerkende signature style eigenlijk bedacht? Het antwoord vindt u vanaf februari in het Gemeentemuseum Den Haag. De tentoonstelling Piet Mondriaan en Bart van der Leck. De uitvinding van een nieuwe kunst vertelt het verhaal van de vriendschap en wederzijdse beïnvloeding tussen twee schilders die heeft geleid tot het inhoudelijk fundament van De Stijl.

Piet Mondriaan en Bart van der Leck ontmoeten elkaar in 1917 in Laren. Een dorpje waar zich op dat moment veel kunstenaars verzamelen. Mondriaan heeft dan al even in Parijs gewoond, maar kan door het uitbreken van de Eerste Wereldoorlog na een familiebezoek in Nederland tijdelijk niet terug naar Parijs. Bart van der Leck heeft veel in Nederland gewerkt, waaronder in Den Haag.

Piet Mondriaan en Bart van der Leck ontmoeten elkaar in 1917 in Laren. Een dorpje waar zich op dat moment veel kunstenaars verzamelen. Mondriaan heeft dan al even in Parijs gewoond, maar kan door het uitbreken van de Eerste Wereldoorlog na een familiebezoek in Nederland tijdelijk niet terug naar Parijs. Bart van der Leck heeft veel in Nederland gewerkt, waaronder in Den Haag.

Van der Leck en Mondriaan zijn er allebei van overtuigd dat er een nieuwe kunst voor een moderne wereld moet komen. Van der Leck bouwt voort op zijn ervaringen als glasschilder en zijn bewondering van de simpele vormgeving van Egyptische kunst. Mondriaan is direct geboeid door het kleurgebruik van Van der Leck. Van der Leck op zijn beurt is onder de indruk van Mondriaans zoektocht naar abstractie. In navolging van Mondriaan begint hij zijn doeken ook ‘composities’ te noemen en durft hij de figuratie los te laten.

In Parijs vindt Mondriaan de sleutel tot de abstractie in het kubisme. Tijdens zijn eerste jaren daar maakt hij voornamelijk kubistische bewerkingen van eerder gemaakt figuratief werk. Van der Leck legt een andere route af. Hij maakt gebruik van een methode die hij doorbeelding noemt. Beginnend bij een schets van een situatie uit de werkelijkheid, een persoon of een dier, brengt hij deze stap voor stap terug tot geometrische vormen. Zo komen beide kunstenaars onafhankelijk van elkaar tot een manier om abstracte kunst te maken.

In Parijs vindt Mondriaan de sleutel tot de abstractie in het kubisme. Tijdens zijn eerste jaren daar maakt hij voornamelijk kubistische bewerkingen van eerder gemaakt figuratief werk. Van der Leck legt een andere route af. Hij maakt gebruik van een methode die hij doorbeelding noemt. Beginnend bij een schets van een situatie uit de werkelijkheid, een persoon of een dier, brengt hij deze stap voor stap terug tot geometrische vormen. Zo komen beide kunstenaars onafhankelijk van elkaar tot een manier om abstracte kunst te maken.

Niet eerder waren de onderlinge relatie en blijvende invloed van Mondriaan en Van der Leck onderwerp van een tentoonstelling. De presentatie ontrafelt het verhaal van de vriendschap aan de hand van schilderijen, historische foto’s en ander archiefmateriaal. Met prachtige bruiklenen uit het Museum of Modern Art (MoMa) en het Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum.

Rembrandt, Van Gogh en Mondriaan. Het zijn de drie Nederlandse kunstenaars die wereldberoemd zijn. 2015 was het Van Gogh jaar. En in 2016 keek de wereld naar het Rijksmuseum voor Rembrandt van Rijn. Nu is het tijd voor een groots internationaal eerbetoon aan Piet Mondriaan. Het Gemeentemuseum is daarvoor de best denkbare plek. De collectie telt maar liefst 300 kunstwerken uit alle fases van Mondriaans baanbrekende oeuvre en in 2017 zijn deze allemaal te zien in één grote tentoonstelling. Al die kunstwerken bij elkaar vormen een unieke tijdreis door de moderne kunst én door Mondriaans boeiende leven in de metropolen Amsterdam, Parijs, Londen en New York. Mondriaans werk is als een tijdreis door de moderne kunst.

Rembrandt, Van Gogh en Mondriaan. Het zijn de drie Nederlandse kunstenaars die wereldberoemd zijn. 2015 was het Van Gogh jaar. En in 2016 keek de wereld naar het Rijksmuseum voor Rembrandt van Rijn. Nu is het tijd voor een groots internationaal eerbetoon aan Piet Mondriaan. Het Gemeentemuseum is daarvoor de best denkbare plek. De collectie telt maar liefst 300 kunstwerken uit alle fases van Mondriaans baanbrekende oeuvre en in 2017 zijn deze allemaal te zien in één grote tentoonstelling. Al die kunstwerken bij elkaar vormen een unieke tijdreis door de moderne kunst én door Mondriaans boeiende leven in de metropolen Amsterdam, Parijs, Londen en New York. Mondriaans werk is als een tijdreis door de moderne kunst.

Waar veel mensen denken dat De Stijl heel serieus en kil was; alsof hun kunst met de liniaal op de tekentafel is gemaakt, ontdekt u in Den Haag dat het tegendeel waar is. Met het gebruik van heldere, primaire kleuren geven De Stijl-kunstenaars vorm aan hun levendige, vrije en vrolijke visie op de toekomst: een wereld vol kunst. U ziet schilderijen, meubels, reclameposters, mode en maquettes van schilders, ontwerpers en architecten zoals Vilmos Huszár, Bart van der Leck en Gerrit Rietveld, die de wereld voorgoed hebben veranderd.

Al hoewel veel mensen denken dat Mondriaan een strenge man was, die zich opsloot in zijn atelier om zich te wijden aan zijn kunst, is niets minder waar. Mondriaan was een levensgenieter die woonde in de wereldsteden Amsterdam, Parijs, Londen en New York. Overal waar hij kwam behoorde hij al snel tot de crème de la crème van de kunstwereld en omarmde hij de nieuwste uitvindingen en het leven. Zo was hij gek op jazz, en bezocht hij avond na avond de Parijse ‘Bar Americains’. Hij woonde zelfs een optreden met cheetah van de beroemde Josephine Baker bij. Hij volgde de laatste mode op de voet en gaf al zijn geld uit aan muziek, pakken, dansen en vrouwen. In Londen rekende hij Peggy Guggenheim en Naum Gabo tot zijn vrienden en eenmaal in New York danste hij de sterren van de hemel op zijn favoriete dans: de boogie Woogie. Zijn levensenergie en ‘swing’ bleven waren de ultieme vertaling van alles waar De Stijl voor stond: energiek, positief, het nieuwe omarmend en hemelbestormend.

Al hoewel veel mensen denken dat Mondriaan een strenge man was, die zich opsloot in zijn atelier om zich te wijden aan zijn kunst, is niets minder waar. Mondriaan was een levensgenieter die woonde in de wereldsteden Amsterdam, Parijs, Londen en New York. Overal waar hij kwam behoorde hij al snel tot de crème de la crème van de kunstwereld en omarmde hij de nieuwste uitvindingen en het leven. Zo was hij gek op jazz, en bezocht hij avond na avond de Parijse ‘Bar Americains’. Hij woonde zelfs een optreden met cheetah van de beroemde Josephine Baker bij. Hij volgde de laatste mode op de voet en gaf al zijn geld uit aan muziek, pakken, dansen en vrouwen. In Londen rekende hij Peggy Guggenheim en Naum Gabo tot zijn vrienden en eenmaal in New York danste hij de sterren van de hemel op zijn favoriete dans: de boogie Woogie. Zijn levensenergie en ‘swing’ bleven waren de ultieme vertaling van alles waar De Stijl voor stond: energiek, positief, het nieuwe omarmend en hemelbestormend.

Zaterdag 11 februari 2017

De Koning opent viering van 100 jaar De Stijl

Zijne Majesteit de Koning opent op zaterdag 11 februari 2017

de tentoonstelling ‘Piet Mondriaan en Bart van der Leck –

De uitvinding van een nieuwe kunst’ in het Gemeentemuseum Den Haag.

11 februari 2017 t/m 21 mei 2017

Piet Mondriaan en Bart van der Leck

De uitvinding van een nieuwe kunst

03 juni 2017 t/m 24 september 2017

De ontdekking van Mondriaan

Amsterdam – Parijs -Londen – New York

10 juni 2017 t/m 17 september 2017

De architectuur en interieurs van De Stijl

De basis voor het design van nu

Doorlopend Gemeentemuseum Den Haag

Mondriaan & De Stijl

Ontdek de wereld van Mondriaan en De Stijl

Gemeentemuseum Den Haag

Stadhouderslaan 41

2517 HV Den Haag

# Meer informatie op website Gemeentemuseum Den Haag

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Antony Kok, Antony Kok, Art & Literature News, Bauhaus, Bauhaus, Constructivism, Constuctivisme, Dada, Dadaïsme, De Ploeg, De Stijl, Design, DICTIONARY OF IDEAS, Doesburg, Theo van, Dutch Landscapes, Essays about Van Doesburg, Kok, Mondriaan, Schwitters, Milius & Van Moorsel, Evert en Thijs Rinsema, Exhibition Archive, Futurism, Futurisme, Kok, Antony, Kurt Schwitters, Magazines, Piet Mondriaan, Schwitters, Kurt, Theo van Doesburg, Theo van Doesburg, Theo van Doesburg (I.K. Bonset), Werkman, Hendrik Nicolaas

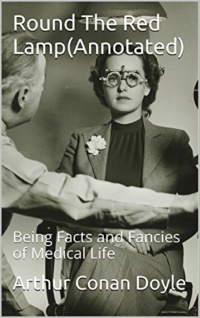

A Question of Diplomacy

A Question of Diplomacy

by Arthur Conan Doyle

The Foreign Minister was down with the gout. For a week he had been confined to the house, and he had missed two Cabinet Councils at a time when the pressure upon his department was severe. It is true that he had an excellent undersecretary and an admirable staff, but the Minister was a man of such ripe experience and of such proven sagacity that things halted in his absence. When his firm hand was at the wheel the great ship of State rode easily and smoothly upon her way; when it was removed she yawed and staggered until twelve British editors rose up in their omniscience and traced out twelve several courses, each of which was the sole and only path to safety. Then it was that the Opposition said vain things, and that the harassed Prime Minister prayed for his absent colleague.

The Foreign Minister sat in his dressing-room in the great house in Cavendish Square. It was May, and the square garden shot up like a veil of green in front of his window, but, in spite of the sunshine, a fire crackled and sputtered in the grate of the sick-room. In a deep-red plush armchair sat the great statesman, his head leaning back upon a silken pillow, one foot stretched forward and supported upon a padded rest. His deeply-lined, finely-chiselled face and slow-moving, heavily-pouched eyes were turned upwards towards the carved and painted ceiling, with that inscrutable expression which had been the despair and the admiration of his Continental colleagues upon the occasion of the famous Congress when he had made his first appearance in the arena of European diplomacy. Yet at the present moment his capacity for hiding his emotions had for the instant failed him, for about the lines of his strong, straight mouth and the puckers of his broad, overhanging forehead, there were sufficient indications of the restlessness and impatience which consumed him.

And indeed there was enough to make a man chafe, for he had much to think of and yet was bereft of the power of thought. There was, for example, that question of the Dobrutscha and the navigation of the mouths of the Danube which was ripe for settlement. The Russian Chancellor had sent a masterly statement upon the subject, and it was the pet ambition of our Minister to answer it in a worthy fashion. Then there was the blockade of Crete, and the British fleet lying off Cape Matapan, waiting for instructions which might change the course of European history. And there were those three unfortunate Macedonian tourists, whose friends were momentarily expecting to receive their ears or their fingers in default of the exorbitant ransom which had been demanded. They must be plucked out of those mountains, by force or by diplomacy, or an outraged public would vent its wrath upon Downing Street. All these questions pressed for a solution, and yet here was the Foreign Minister of England, planted in an arm-chair, with his whole thoughts and attention riveted upon the ball of his right toe! It was humiliating—horribly humiliating! His reason revolted at it. He had been a respecter of himself, a respecter of his own will; but what sort of a machine was it which could be utterly thrown out of gear by a little piece of inflamed gristle? He groaned and writhed among his cushions.

But, after all, was it quite impossible that he should go down to the House? Perhaps the doctor was exaggerating the situation. There was a Cabinet Council that day. He glanced at his watch. It must be nearly over by now. But at least he might perhaps venture to drive down as far as Westminster. He pushed back the little round table with its bristle of medicine-bottles, and levering himself up with a hand upon either arm of the chair, he clutched a thick oak stick and hobbled slowly across the room. For a moment as he moved, his energy of mind and body seemed to return to him. The British fleet should sail from Matapan. Pressure should be brought to bear upon the Turks. The Greeks should be shown—Ow! In an instant the Mediterranean was blotted out, and nothing remained but that huge, undeniable, intrusive, red-hot toe. He staggered to the window and rested his left hand upon the ledge, while he propped himself upon his stick with his right. Outside lay the bright, cool, square garden, a few well-dressed passers-by, and a single, neatly-appointed carriage, which was driving away from his own door. His quick eye caught the coat-of-arms on the panel, and his lips set for a moment and his bushy eyebrows gathered ominously with a deep furrow between them. He hobbled back to his seat and struck the gong which stood upon the table.

“Your mistress!” said he as the serving-man entered.

It was clear that it was impossible to think of going to the House. The shooting up his leg warned him that his doctor had not overestimated the situation. But he had a little mental worry now which had for the moment eclipsed his physical ailments. He tapped the ground impatiently with his stick until the door of the dressing-room swung open, and a tall, elegant lady of rather more than middle age swept into the chamber. Her hair was touched with grey, but her calm, sweet face had all the freshness of youth, and her gown of green shot plush, with a sparkle of gold passementerie at her bosom and shoulders, showed off the lines of her fine figure to their best advantage.

“You sent for me, Charles?”

“Whose carriage was that which drove away just now?”

“Oh, you’ve been up!” she cried, shaking an admonitory forefinger. “What an old dear it is! How can you be so rash? What am I to say to Sir William when he comes? You know that he gives up his cases when they are insubordinate.”

“In this instance the case may give him up,” said the Minister, peevishly; “but I must beg, Clara, that you will answer my question.”

“Oh! the carriage! It must have been Lord Arthur Sibthorpe’s.”

“I saw the three chevrons upon the panel,” muttered the invalid.

His lady had pulled herself a little straighter and opened her large blue eyes.

“Then why ask?” she said. “One might almost think, Charles, that you were laying a trap! Did you expect that I should deceive you? You have not had your lithia powder.”

“For Heaven’s sake, leave it alone! I asked because I was surprised that Lord Arthur should call here. I should have fancied, Clara, that I had made myself sufficiently clear on that point. Who received him?”

“I did. That is, I and Ida.”

“I will not have him brought into contact with Ida. I do not approve of it. The matter has gone too far already.”

Lady Clara seated herself on a velvet-topped footstool, and bent her stately figure over the Minister’s hand, which she patted softly between her own.

“Now you have said it, Charles,” said she. “It has gone too far—I give you my word, dear, that I never suspected it until it was past all mending. I may be to blame—no doubt I am; but it was all so sudden. The tail end of the season and a week at Lord Donnythorne’s. That was all. But oh! Charlie, she loves him so, and she is our only one! How can we make her miserable?”

“Tut, tut!” cried the Minister impatiently, slapping on the plush arm of his chair. “This is too much. I tell you, Clara, I give you my word, that all my official duties, all the affairs of this great empire, do not give me the trouble that Ida does.”

“But she is our only one, Charles.”

“The more reason that she should not make a mesalliance.”

“Mesalliance, Charles! Lord Arthur Sibthorpe, son of the Duke of Tavistock, with a pedigree from the Heptarchy. Debrett takes them right back to Morcar, Earl of Northumberland.”

The Minister shrugged his shoulders.

“Lord Arthur is the fourth son of the poorest duke in England,” said he. “He has neither prospects nor profession.”

“But, oh! Charlie, you could find him both.”

“I do not like him. I do not care for the connection.”

“But consider Ida! You know how frail her health is. Her whole soul is set upon him. You would not have the heart, Charles, to separate them?”

There was a tap at the door. Lady Clara swept towards it and threw it open.

“Yes, Thomas?”

“If you please, my lady, the Prime Minister is below.”

“Show him up, Thomas.”

“Now, Charlie, you must not excite yourself over public matters. Be very good and cool and reasonable, like a darling. I am sure that I may trust you.”

She threw her light shawl round the invalid’s shoulders, and slipped away into the bed-room as the great man was ushered in at the door of the dressing-room.

“My dear Charles,” said he cordially, stepping into the room with all the boyish briskness for which he was famous, “I trust that you find yourself a little better. Almost ready for harness, eh? We miss you sadly, both in the House and in the Council. Quite a storm brewing over this Grecian business. The Times took a nasty line this morning.”

“So I saw,” said the invalid, smiling up at his chief. “Well, well, we must let them see that the country is not entirely ruled from Printing House Square yet. We must keep our own course without faltering.”

“Certainly, Charles, most undoubtedly,” assented the Prime Minister, with his hands in his pockets.

“It was so kind of you to call. I am all impatience to know what was done in the Council.”

“Pure formalities, nothing more. By-the-way, the Macedonian prisoners are all right.”

“Thank Goodness for that!”

“We adjourned all other business until we should have you with us next week. The question of a dissolution begins to press. The reports from the provinces are excellent.”

The Foreign Minister moved impatiently and groaned.

“We must really straighten up our foreign business a little,” said he. “I must get Novikoff’s Note answered. It is clever, but the fallacies are obvious. I wish, too, we could clear up the Afghan frontier. This illness is most exasperating. There is so much to be done, but my brain is clouded. Sometimes I think it is the gout, and sometimes I put it down to the colchicum.”

“What will our medical autocrat say?” laughed the Prime Minister. “You are so irreverent, Charles. With a bishop one may feel at one’s ease. They are not beyond the reach of argument. But a doctor with his stethoscope and thermometer is a thing apart. Your reading does not impinge upon him. He is serenely above you. And then, of course, he takes you at a disadvantage. With health and strength one might cope with him. Have you read Hahnemann? What are your views upon Hahnemann?”

The invalid knew his illustrious colleague too well to follow him down any of those by-paths of knowledge in which he delighted to wander. To his intensely shrewd and practical mind there was something repellent in the waste of energy involved in a discussion upon the Early Church or the twenty-seven principles of Mesmer. It was his custom to slip past such conversational openings with a quick step and an averted face.

“I have hardly glanced at his writings,” said he. “By-the-way, I suppose that there was no special departmental news?”

“Ah! I had almost forgotten. Yes, it was one of the things which I had called to tell you. Sir Algernon Jones has resigned at Tangier. There is a vacancy there.”

“It had better be filled at once. The longer delay the more applicants.”

“Ah, patronage, patronage!” sighed the Prime Minister. “Every vacancy makes one doubtful friend and a dozen very positive enemies. Who so bitter as the disappointed place-seeker? But you are right, Charles. Better fill it at once, especially as there is some little trouble in Morocco. I understand that the Duke of Tavistock would like the place for his fourth son, Lord Arthur Sibthorpe. We are under some obligation to the Duke.”

The Foreign Minister sat up eagerly.

“My dear friend,” he said, “it is the very appointment which I should have suggested. Lord Arthur would be very much better in Tangier at present than in—in——”

“Cavendish Square?” hazarded his chief, with a little arch query of his eyebrows.

“Well, let us say London. He has manner and tact. He was at Constantinople in Norton’s time.”

“Then he talks Arabic?”

“A smattering. But his French is good.”

“Speaking of Arabic, Charles, have you dipped into Averroes?”

“No, I have not. But the appointment would be an excellent one in every way. Would you have the great goodness to arrange the matter in my absence?”

“Certainly, Charles, certainly. Is there anything else that I can do?”

“No. I hope to be in the House by Monday.”

“I trust so. We miss you at every turn. The Times will try to make mischief over that Grecian business. A leader-writer is a terribly irresponsible thing, Charles. There is no method by which he may be confuted, however preposterous his assertions. Good-bye! Read Porson! Goodbye!”

He shook the invalid’s hand, gave a jaunty wave of his broad-brimmed hat, and darted out of the room with the same elasticity and energy with which he had entered it.

The footman had already opened the great folding door to usher the illustrious visitor to his carriage, when a lady stepped from the drawing-room and touched him on the sleeve. From behind the half-closed portiere of stamped velvet a little pale face peeped out, half-curious, half-frightened.

“May I have one word?”

“Surely, Lady Clara.”

“I hope it is not intrusive. I would not for the world overstep the limits——”

“My dear Lady Clara!” interrupted the Prime Minister, with a youthful bow and wave.

“Pray do not answer me if I go too far. But I know that Lord Arthur Sibthorpe has applied for Tangier. Would it be a liberty if I asked you what chance he has?”

“The post is filled up.”

“Oh!”

In the foreground and background there was a disappointed face.

“And Lord Arthur has it.”

The Prime Minister chuckled over his little piece of roguery.

“We have just decided it,” he continued.

“Lord Arthur must go in a week. I am delighted to perceive, Lady Clara, that the appointment has your approval. Tangier is a place of extraordinary interest. Catherine of Braganza and Colonel Kirke will occur to your memory. Burton has written well upon Northern Africa. I dine at Windsor, so I am sure that you will excuse my leaving you. I trust that Lord Charles will be better. He can hardly fail to be so with such a nurse.”

He bowed, waved, and was off down the steps to his brougham. As he drove away, Lady Clara could see that he was already deeply absorbed in a paper-covered novel.

She pushed back the velvet curtains, and returned into the drawing-room. Her daughter stood in the sunlight by the window, tall, fragile, and exquisite, her features and outline not unlike her mother’s, but frailer, softer, more delicate. The golden light struck one half of her high-bred, sensitive face, and glimmered upon her thickly-coiled flaxen hair, striking a pinkish tint from her closely-cut costume of fawn-coloured cloth with its dainty cinnamon ruchings. One little soft frill of chiffon nestled round her throat, from which the white, graceful neck and well-poised head shot up like a lily amid moss. Her thin white hands were pressed together, and her blue eyes turned beseechingly upon her mother.

“Silly girl! Silly girl!” said the matron, answering that imploring look. She put her hands upon her daughter’s sloping shoulders and drew her towards her. “It is a very nice place for a short time. It will be a stepping stone.”

“But oh! mamma, in a week! Poor Arthur!”

“He will be happy.”

“What! happy to part?”

“He need not part. You shall go with him.”

“Oh! mamma!”

“Yes, I say it.”

“Oh! mamma, in a week?”

“Yes indeed. A great deal may be done in a week. I shall order your trousseau to-day.”

“Oh! you dear, sweet angel! But I am so frightened! And papa? Oh! dear, I am so frightened!”

“Your papa is a diplomatist, dear.”

“Yes, ma.”

“But, between ourselves, he married a diplomatist too. If he can manage the British Empire, I think that I can manage him, Ida. How long have you been engaged, child?”

“Ten weeks, mamma.”

“Then it is quite time it came to a head. Lord Arthur cannot leave England without you. You must go to Tangier as the Minister’s wife. Now, you will sit there on the settee, dear, and let me manage entirely. There is Sir William’s carriage! I do think that I know how to manage Sir William. James, just ask the doctor to step in this way!”

A heavy, two-horsed carriage had drawn up at the door, and there came a single stately thud upon the knocker. An instant afterwards the drawing-room door flew open and the footman ushered in the famous physician. He was a small man, clean-shaven, with the old-fashioned black dress and white cravat with high-standing collar. He swung his golden pince-nez in his right hand as he walked, and bent forward with a peering, blinking expression, which was somehow suggestive of the dark and complex cases through which he had seen.

“Ah,” said he, as he entered. “My young patient! I am glad of the opportunity.”

“Yes, I wish to speak to you about her, Sir William. Pray take this arm-chair.”

“Thank you, I will sit beside her,” said he, taking his place upon the settee. “She is looking better, less anaemic unquestionably, and a fuller pulse. Quite a little tinge of colour, and yet not hectic.”

“I feel stronger, Sir William.”

“But she still has the pain in the side.”

“Ah, that pain!” He tapped lightly under the collar-bones, and then bent forward with his biaural stethoscope in either ear. “Still a trace of dulness—still a slight crepitation,” he murmured.

“You spoke of a change, doctor.”

“Yes, certainly a judicious change might be advisable.”

“You said a dry climate. I wish to do to the letter what you recommend.”

“You have always been model patients.”

“We wish to be. You said a dry climate.”

“Did I? I rather forget the particulars of our conversation. But a dry climate is certainly indicated.”

“Which one?”

“Well, I think really that a patient should be allowed some latitude. I must not exact too rigid discipline. There is room for individual choice—the Engadine, Central Europe, Egypt, Algiers, which you like.”

“I hear that Tangier is also recommended.”

“Oh, yes, certainly; it is very dry.”

“You hear, Ida? Sir William says that you are to go to Tangier.”

“Or any——”

“No, no, Sir William! We feel safest when we are most obedient. You have said Tangier, and we shall certainly try Tangier.”

“Really, Lady Clara, your implicit faith is most flattering. It is not everyone who would sacrifice their own plans and inclinations so readily.”

“We know your skill and your experience, Sir William. Ida shall try Tangier. I am convinced that she will be benefited.”

“I have no doubt of it.”

“But you know Lord Charles. He is just a little inclined to decide medical matters as he would an affair of State. I hope that you will be firm with him.”

“As long as Lord Charles honours me so far as to ask my advice I am sure that he would not place me in the false position of having that advice disregarded.”

The medical baronet whirled round the cord of his pince-nez and pushed out a protesting hand.

“No, no, but you must be firm on the point of Tangier.”

“Having deliberately formed the opinion that Tangier is the best place for our young patient, I do not think that I shall readily change my conviction.”

“Of course not.”

“I shall speak to Lord Charles upon the subject now when I go upstairs.”

“Pray do.”

“And meanwhile she will continue her present course of treatment. I trust that the warm African air may send her back in a few months with all her energy restored.”

He bowed in the courteous, sweeping, old-world fashion which had done so much to build up his ten thousand a year, and, with the stealthy gait of a man whose life is spent in sick-rooms, he followed the footman upstairs.

As the red velvet curtains swept back into position, the Lady Ida threw her arms round her mother’s neck and sank her face on to her bosom.

“Oh! mamma, you ARE a diplomatist!” she cried.

But her mother’s expression was rather that of the general who looked upon the first smoke of the guns than of one who had won the victory.

“All will be right, dear,” said she, glancing down at the fluffy yellow curls and tiny ear. “There is still much to be done, but I think we may venture to order the trousseau.”

“Oh I how brave you are!”

“Of course, it will in any case be a very quiet affair. Arthur must get the license. I do not approve of hole-and-corner marriages, but where the gentleman has to take up an official position some allowance must be made. We can have Lady Hilda Edgecombe, and the Trevors, and the Grevilles, and I am sure that the Prime Minister would run down if he could.”

“And papa?”

“Oh, yes; he will come too, if he is well enough. We must wait until Sir William goes, and, meanwhile, I shall write to Lord Arthur.”

Half an hour had passed, and quite a number of notes had been dashed off in the fine, bold, park-paling handwriting of the Lady Clara, when the door clashed, and the wheels of the doctor’s carriage were heard grating outside against the kerb. The Lady Clara laid down her pen, kissed her daughter, and started off for the sick-room. The Foreign Minister was lying back in his chair, with a red silk handkerchief over his forehead, and his bulbous, cotton-wadded foot still protruding upon its rest.

“I think it is almost liniment time,” said Lady Clara, shaking a blue crinkled bottle. “Shall I put on a little?”

“Oh! this pestilent toe!” groaned the sufferer. “Sir William won’t hear of my moving yet. I do think he is the most completely obstinate and pig-headed man that I have ever met. I tell him that he has mistaken his profession, and that I could find him a post at Constantinople. We need a mule out there.”

“Poor Sir William!” laughed Lady Clara. “But how has he roused your wrath?”

“He is so persistent-so dogmatic.”

“Upon what point?”

“Well, he has been laying down the law about Ida. He has decreed, it seems, that she is to go to Tangier.”

“He said something to that effect before he went up to you.”

“Oh, he did, did he?”

The slow-moving, inscrutable eye came sliding round to her.

Lady Clara’s face had assumed an expression of transparent obvious innocence, an intrusive candour which is never seen in nature save when a woman is bent upon deception.

Lady Clara’s face had assumed an expression of transparent obvious innocence, an intrusive candour which is never seen in nature save when a woman is bent upon deception.

“He examined her lungs, Charles. He did not say much, but his expression was very grave.”

“Not to say owlish,” interrupted the Minister.

“No, no, Charles; it is no laughing matter. He said that she must have a change. I am sure that he thought more than he said. He spoke of dulness and crepitation, and the effects of the African air. Then the talk turned upon dry, bracing health resorts, and he agreed that Tangier was the place. He said that even a few months there would work a change.”

“And that was all?”

“Yes, that was all.”

Lord Charles shrugged his shoulders with the air of a man who is but half convinced.

“But of course,” said Lady Clara, serenely, “if you think it better that Ida should not go she shall not. The only thing is that if she should get worse we might feel a little uncomfortable afterwards. In a weakness of that sort a very short time may make a difference. Sir William evidently thought the matter critical. Still, there is no reason why he should influence you. It is a little responsibility, however. If you take it all upon yourself and free me from any of it, so that afterwards——”

“My dear Clara, how you do croak!”

“Oh! I don’t wish to do that, Charles. But you remember what happened to Lord Bellamy’s child. She was just Ida’s age. That was another case in which Sir William’s advice was disregarded.”

Lord Charles groaned impatiently.

“I have not disregarded it,” said he.

“No, no, of course not. I know your strong sense, and your good heart too well, dear. You were very wisely looking at both sides of the question. That is what we poor women cannot do. It is emotion against reason, as I have often heard you say. We are swayed this way and that, but you men are persistent, and so you gain your way with us. But I am so pleased that you have decided for Tangier.”

“Have I?”

“Well, dear, you said that you would not disregard Sir William.”

“Well, Clara, admitting that Ida is to go to Tangier, you will allow that it is impossible for me to escort her?

“Utterly.”

“And for you?

“While you are ill my place is by your side.”

“There is your sister?”

“She is going to Florida.”

“Lady Dumbarton, then?”

“She is nursing her father. It is out of the question.”

“Well, then, whom can we possibly ask? Especially just as the season is commencing. You see, Clara, the fates fight against Sir William.”

His wife rested her elbows against the back of the great red chair, and passed her fingers through the statesman’s grizzled curls, stooping down as she did so until her lips were close to his ear.

“There is Lord Arthur Sibthorpe,” said she softly.

Lord Charles bounded in his chair, and muttered a word or two such as were more frequently heard from Cabinet Ministers in Lord Melbourne’s time than now.

“Are you mad, Clara!” he cried. “What can have put such a thought into your head?”

“The Prime Minister.”

“Who? The Prime Minister?”

“Yes, dear. Now do, do be good! Or perhaps I had better not speak to you about it any more.”

“Well, I really think that you have gone rather too far to retreat.”

“It was the Prime Minister, then, who told me that Lord Arthur was going to Tangier.”

“It is a fact, though it had escaped my memory for the instant.”

“And then came Sir William with his advice about Ida. Oh! Charlie, it is surely more than a coincidence!”

“I am convinced,” said Lord Charles, with his shrewd, questioning gaze, “that it is very much more than a coincidence, Lady Clara. You are a very clever woman, my dear. A born manager and organiser.”

Lady Clara brushed past the compliment.

“Think of our own young days, Charlie,” she whispered, with her fingers still toying with his hair. “What were you then? A poor man, not even Ambassador at Tangier. But I loved you, and believed in you, and have I ever regretted it? Ida loves and believes in Lord Arthur, and why should she ever regret it either?”

Lord Charles was silent. His eyes were fixed upon the green branches which waved outside the window; but his mind had flashed back to a Devonshire country-house of thirty years ago, and to the one fateful evening when, between old yew hedges, he paced along beside a slender girl, and poured out to her his hopes, his fears, and his ambitious. He took the white, thin hand and pressed it to his lips.

“You, have been a good wife to me, Clara,” said he.

She said nothing. She did not attempt to improve upon her advantage. A less consummate general might have tried to do so, and ruined all. She stood silent and submissive, noting the quick play of thought which peeped from his eyes and lip. There was a sparkle in the one and a twitch of amusement in the other, as he at last glanced up at her.

“Clara,” said he, “deny it if you can! You have ordered the trousseau.”

She gave his ear a little pinch.

“Subject to your approval,” said she.

“You have written to the Archbishop.”

“It is not posted yet.”

“You have sent a note to Lord Arthur.”

“How could you tell that?”

“He is downstairs now.”

“No; but I think that is his brougham.”

Lord Charles sank back with a look of half-comical despair.

“Who is to fight against such a woman?” he cried. “Oh! if I could send you to Novikoff! He is too much for any of my men. But, Clara, I cannot have them up here.”

“Not for your blessing?”

“No, no!”

“It would make them so happy.”

“I cannot stand scenes.”

“Then I shall convey it to them.”

“And pray say no more about it—to-day, at any rate. I have been weak over the matter.”

“Oh! Charlie, you who are so strong!”

“You have outflanked me, Clara. It was very well done. I must congratulate you.”

“Well,” she murmured, as she kissed him, “you know I have been studying a very clever diplomatist for thirty years.”

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859 – 1930)

Round the Red Lamp: Being Facts and Fancies of Medical Life

A Question of Diplomacy (#10)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Doyle, Arthur Conan, Doyle, Arthur Conan, DRUGS & DISEASE & MEDICINE & LITERATURE, Round the Red Lamp

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature