Fleurs du Mal Magazine

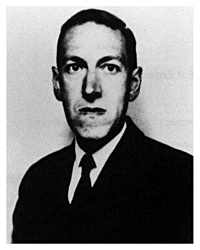

Max Jacob

(1876 – 1944)

Romance

Je garde dans la solitude comme un pressentiment de toi.

Tu viens ! et le ciel se déploie, la forêt, l’océan reculent.

Tous deux le soleil nous désigne par-dessus la ville et les toits les fenêtres renvoient ses lignes les fleurs éclatent comme des voix.

Lorsque ton jardin nous reçoit, ta maison prend un air étrange: comme un reflet, la véranda nous accueille, sourit et change.

Les arbres ont de grands coups d’ailes derrière et devant les buissons.

La vague, au loin, parallèle, se met à briller par frissons.

Je garde dans la solitude comme un pressentiment de toi.

Tu viens ! et le ciel se déploie, la forêt, l’océan reculent.

Max Jacob poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive I-J, Jacob, Max

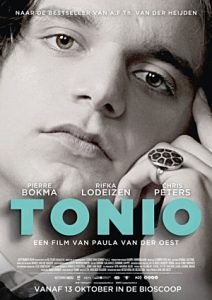

TONIO – Drama gebaseerd op de gelijknamige roman van A.F.Th. van der Heijden met in de hoofdrollen Pierre Bokma en Rifka Lodeizen.

TONIO – Drama gebaseerd op de gelijknamige roman van A.F.Th. van der Heijden met in de hoofdrollen Pierre Bokma en Rifka Lodeizen.

Regie: Paula van der Oest

Cast: Pierre Bokma (Adri), Rifka Lodeizen (Mirjam), Chris Peters (Tonio), Stefanie van Leersum (Jenny), Beppie Melissen, Henri Garcin, Pauline Greidanus, Nick Vorsselman, Jorn Pronk, Marieke Giebels e.a.

Op Eerste Pinksterdag 2010 fietst de 21-jarige Tonio vroeg in de ochtend richting huis na een avond uit met zijn vrienden. Hij wordt onderweg geschept door een auto en komt hierbij om het leven. Zijn ouders Adri en Mirjam worden geconfronteerd met het grootste verlies dat hun leven voorgoed zal veranderen. Terwijl Mirjam hard vecht om niet in een neerwaartse spiraal van verdriet terecht te komen, doet Adri het enige waar hij op dat moment toe in staat is: in zijn herinnering graven, aantekeningen maken, schrijven. Zijn gedachten worden voortgedreven door twee  dwingende vragen: wat gebeurde er met Tonio in de laatste uren en dagen voorafgaand aan de ramp, en hoe kon dit ongeluk plaatsvinden? Een zoektocht naar het wat en het hoe, die leidt langs verschillende ooggetuigen, vrienden, politieagenten en artsen. Zo reconstrueert hij het leven van zijn zoon in een radeloze queeste naar zin en betekenis.

dwingende vragen: wat gebeurde er met Tonio in de laatste uren en dagen voorafgaand aan de ramp, en hoe kon dit ongeluk plaatsvinden? Een zoektocht naar het wat en het hoe, die leidt langs verschillende ooggetuigen, vrienden, politieagenten en artsen. Zo reconstrueert hij het leven van zijn zoon in een radeloze queeste naar zin en betekenis.

TONIO van regisseur Paula van der Oest is geselecteerd om Nederland te vertegenwoordigen voor de aankomende Academy Awards.

TONIO is gebaseerd op de gelijknamige roman van auteur A. F. TH. van der Heijden. Het scenario voor de film is geschreven door Hugo Heinen en geproduceerd door Alain de Levita, Sytze van der Laan en Sabine Brian. Speelduur: 100 minuten. Jaar: 2016

# Waar draait Tonio in de bioscoop?

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Stories, A.F.Th. van der Heijden, Art & Literature News, AUDIO, CINEMA, RADIO & TV

Bloomsbury Festival 2016 London October 19 to 23 october

Bloomsbury Festival 2016 London October 19 to 23 october

For hundreds of years, Bloomsbury has been catalyst for ideas that have had impact across the world. Bloomsbury Festival celebrates contemporary Bloomsbury; a hotbed of creativity and pioneering development which has one of the youngest and most diverse populations in the country.

For five days in October, Bloomsbury will be full to the brim with artistic, scientific and literary events for all ages and tastes, from breakfast until late in the evenings taking place in the streets, parks, museums, galleries, laboratories and public and (normally) private buildings of this vibrant cultural quarter. There will be over 150 events created with over 100 partners.

Inspired by the centenary of SOAS and with Bloomsbury residents reflecting one of highest levels of diversity in the UK, the theme selected for this year’s festival is Language. Language comes in many forms; speech, symbols, non-verbal communication, performance language, dance notation, morse code, sign language, computer code. Language will be explored throughout all the events; from the cuneiform inscriptions on tablets of clay at the British Museum inspiring a collaboration by an artist and historian, to investigations of Legal and medical ‘languages’ that are used in many firms and laboratories and hospitals in Bloomsbury.

Baroness Valerie Amos, Director of SOAS says: ‘As we celebrate 100 years of SOAS teaching and research, we are delighted that the Bloomsbury Festival’s theme this year is dedicated to language. SOAS is a special place with its unique blend of languages, regional and discipline expertise. We are proud of our Bloomsbury location and, with the addition of Senate House North Block, the growth of our Bloomsbury Campus. As we look forward to the next 100 years, we will continue to play a central role in the cultural and creative life of the area.’

Kate Anderson, Bloomsbury Festival director says ‘Bloomsbury Festival is unique, as is the area of Bloomsbury in which leading institutions and world-class creative organisations rub shoulders with primary schools and lawyers. We make the Festival with over 100 Bloomsbury partners, providing opportunities for unusual collaborations and development opportunities for all. The result is a very distinctive festival indeed! And with over 150 events including all art forms, science, architecture, walks, technology, outdoor music, debating and hubs focusing on families, I think we can safely say there is something for everyone at Bloomsbury Festival.

A few of this year’s headline events include Coram’s Songs, a promenade performance set in the known and secret spaces around the Foundling Hospital. 2016 marks the 275th anniversary of the Foundling Hospital and the 80th anniversary of Coram’s Fields. Created by director Emma Bernard in partnership with renowned composers including Jocelyn Pook, Orlando Gough, Michael Henry and Melanie Pappenheim, Coram’s Songs is inspired by this unique seven acre, greenfield site in central London that has been preserved as a sanctuary for children for circa 300 years.

A few of this year’s headline events include Coram’s Songs, a promenade performance set in the known and secret spaces around the Foundling Hospital. 2016 marks the 275th anniversary of the Foundling Hospital and the 80th anniversary of Coram’s Fields. Created by director Emma Bernard in partnership with renowned composers including Jocelyn Pook, Orlando Gough, Michael Henry and Melanie Pappenheim, Coram’s Songs is inspired by this unique seven acre, greenfield site in central London that has been preserved as a sanctuary for children for circa 300 years.

Step Out Store Street will be a night-time street party with a twist: the street will be transformed by an array of artists and dancers, showcasing and teaching different dance disciplines from around the world, from Bollywood to BBoy and Swing to Line dancing. Pa-BOOM’s fiery pyrotechnic art installations will make a welcome return and the event will also feature a premiere of a new street dance commission from acclaimed dancer Tony Adigun’s Avant Garde Youth Dance Company. The street’s eclectic mix of boutiques, shops and restaurants will each house a different art, music and dance experience and an abundance of street food and bars will be available.

Other headline events will include The Last Whisperers at the British Museum, Calling Tree in St George’s Gardens, a specially curated programme at The Wellcome Trust, Goodensemble and ENO at Goodenough College, and SOAS’ World Music Stage inside the newly opened north block of Senate House.

The festival centres around three main hub venues Goodenough college, UCL, and Conway Hall with activities also taking place at a further 20+ satellite venues including the Wellcome Trust, the British Museum, the British Library, Pushkin House, Charles Dickens Museum, Coram’s Fields, the Music Room, Bloomsbury Hotel, the Curzon Bloomsbury, and Store Street. There will be lunchtime events Wed 19 – Fri 21 for locals and workers to attend and breakfast events and talks in local cafes.

Every year the Festival runs a competition for BA (Hons) Graphic Communication Design, Central Saint Martin’s students to design the festival logo. This year’s winning entry is by Wies van der Wal which the judges felt illustrated the theme of language, the coming together of ideas and joy of the Festival perfectly.

Key Dates and Times:

Key Dates and Times:

Festival Dates: Wednesday 19 October to Sunday 23 October, throughout the day, everyday

Coram’s Songs: Wednesday 19 October, evening and repeated during the Festival, Coram’s Fields, 93 Guilford Street, London, WC1N 1DN

Step Out Store Street: Friday October 21 2016, 6.30pm to 9.30pm, Store Street, Bloomsbury, WC1E 7DH, Free outdoor event, just turn up

Key Locations:

Coram’s Fields, 93 Guilford St, London WC1N 1DN, Camden

Foundling Museum, 40 Brunswick Square, London WC1N 1AZ, Camden

Goodenough College, Mecklenburgh Square, London WC1N 2AB, Camden

Conway Hall, 25 Red Lion Square, London WC1R 4RL

Store Street WC1E 7DB, Camden

UCL Gower St, London WC1E 6BT

Bloomsbury is an area of the London Borough of Camden, in central London, between Euston Road and Holborn, developed by the Russell family in the 17th and 18th centuries into a fashionable residential area. It is notable for its array of garden squares, literary connections (exemplified by the Bloomsbury Group), and numerous cultural, educational and health-care institutions.

Bloomsbury is an area of the London Borough of Camden, in central London, between Euston Road and Holborn, developed by the Russell family in the 17th and 18th centuries into a fashionable residential area. It is notable for its array of garden squares, literary connections (exemplified by the Bloomsbury Group), and numerous cultural, educational and health-care institutions.

Established in 2006, Bloomsbury Festival is a creative explosion of arts, science, literature, culture and fun throughout the streets, parks, museums, galleries, laboratories and public and (normally) private buildings of this vibrant cultural quarter. For hundreds of years Bloomsbury has been a catalyst for ideas that have had impact across the world.

Bloomsbury Festival celebrates contemporary Bloomsbury; a hotbed of creativity and pioneering development which has one of the youngest and most diverse populations in the country. Created with its extraordinary community including more libraries, museums, and educational establishments than any other part of the city, the Festival acts as catalyst bringing together its diverse population, and as a spur to develop new projects and new ideas. Each year, the Festival attracts an audience of around 50,000 people.

# The final programme will be online on Bloomsbury festival website

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Art & Literature News, AUDIO, CINEMA, RADIO & TV, DANCE & PERFORMANCE, FDM in London, Literary Events, MUSIC, Street Art, STREET POETRY, THEATRE, Virginia Woolf

Ehrengast Flandern und die Niederlande

Ehrengast Flandern und die Niederlande

Dies ist, was wir teilen

454 Neuerscheinungen aus und über Flandern und die Niederlande

Der Ehrengast der diesjährigen Frankfurter Buchmesse zeigt 2016 beispielhaft, wie man Grenzen überwindet und zusammen auf Gemeinsamkeiten blickt. Denn in diesem Jahr ist am Main nicht eine Nation, sondern ein Sprach- und Kulturraum Ehrengast. Wie aktiv und erfolgreich Flandern und die Niederlande zusammen gearbeitet haben, belegt die ausgesprochen hohe Anzahl von 454 Neuerscheinungen – und das in vielen Genres: Belletristik, Sachbuch, Lyrik, Kinder- und Jugendliteratur, Comic und Graphic Novel. Zum Vergleich: In den letzten Jahren erschienen im deutschen Sprachraum durchschnittlich 85 neue Übersetzungen pro Jahr.

Im Rahmen der Frankfurter Buchmesse (19. – 23. Oktober 2016) findet ein umfangreiches literarisches und kulturelles Programm statt, an dem etwa 70 flämische und niederländische Schriftsteller aller Genres teilnehmen. Die Besucher erwarten unter anderem Virtual- Reality-Präsentationen, Theater- und Filmfestivals, literarische Gespräche vor großem Publikum sowie Kunst-, Design- und Architekturausstellungen. Ein Teil dieses Geschehens ereignet sich im 2.300 Quadratmeter großen Ehrengast- Pavillon (Forum, Ebene 1) auf dem Messegelände, ein anderer Teil in der Stadt Frankfurt. Künstlerischer Leiter der Ehrengast-Präsentation ist der flämische Kinder- und Jugendbuch-Autor Bart Moeyaert.

Im eigens für den Ehrengast eingerichteten Pavillon findet von 9.30 bis 19.00 Uhr ein abwechslungsreiches Programm bestehend aus zehn unterschiedlichen Formaten statt. Hier eine Auswahl: Via Virtual Reality werden die Besucher den Barcelona-Pavillon betreten können, den Mies van der Rohe anlässlich der Weltausstellung in 1929 in der katalanischen Hauptstadt errichtet hat. Im Kino können Cineasten verschiedene Filme aus und über Flandern und die Niederlande sehen und sich von den Geschichten und Bildern begeistern lassen. Im Atelier entsteht unter der Doppel-Leitung von Joost Swarte und Randall Casaer die Zeitschrift Parade – jeden Tag eine Ausgabe. In der Ausstellung „Books on… Flandern und die Niederlande“ sind Titel über den Ehrengast aus aller Welt zu besichtigen.

Im eigens für den Ehrengast eingerichteten Pavillon findet von 9.30 bis 19.00 Uhr ein abwechslungsreiches Programm bestehend aus zehn unterschiedlichen Formaten statt. Hier eine Auswahl: Via Virtual Reality werden die Besucher den Barcelona-Pavillon betreten können, den Mies van der Rohe anlässlich der Weltausstellung in 1929 in der katalanischen Hauptstadt errichtet hat. Im Kino können Cineasten verschiedene Filme aus und über Flandern und die Niederlande sehen und sich von den Geschichten und Bildern begeistern lassen. Im Atelier entsteht unter der Doppel-Leitung von Joost Swarte und Randall Casaer die Zeitschrift Parade – jeden Tag eine Ausgabe. In der Ausstellung „Books on… Flandern und die Niederlande“ sind Titel über den Ehrengast aus aller Welt zu besichtigen.

Über den Zeitraum von sechs Wochen bietet das Künstlerhaus Mousonturm ein spannendes, Bühnenkunstfestival und lädt an den Messetagen ins Ehrengast-Café ein. Das MMK (Museum Moderne Kunst) hat drei Künstler zu Gast: Fiona Tan (MMK1), Willem de Rooij (MMK2) und Laure Prouvost (MMK3). Auch das Schauspiel Frankfurt, das Städel Museum, das Foto Forum, die basis, das DAM (Deutsches Architektur Museum) und das Deutsche Filminstitut – DIF präsentieren bekannte und weniger bekannte Künstler aus Flandern und den Niederlande. Auf Initiative der Niederländischen Stiftung für Literatur und des Flämischen Literaturfonds finden im Rahmen des Ehrengastauftritts in ganz Deutschland über 400 Veranstaltungen statt. Nähere Informationen unter: www.frankfurt2016.com

Über die Frankfurter Buchmesse: Die Frankfurter Buchmesse ist mit 7.100 Ausstellern aus über 100 Ländern, rund 275.000 Besuchern, über 4.000 Veranstaltungen und rund 9.300 anwesenden akkreditierten Journalisten die größte Fachmesse für das internationale Publishing. Darüber hinaus ist sie ein branchenübergreifender Treffpunkt für Player aus der Filmwirtschaft und der Gamesbranche. Einen inhaltlichen Schwerpunkt bildet seit 1976 der jährlich wechselnde Ehrengast, der dem Messepublikum auf vielfältige Weise seinen Buchmarkt, seine Literatur und Kultur präsentiert. Die Frankfurter Buchmesse organisiert die Beteiligung deutscher Verlage an rund 20 internationalen Buchmessen und veranstaltet ganzjährig Fachveranstaltungen in den wichtigen internationalen Märkten. Mit der Gründung des Frankfurt Book Fair Business Clubs bietet die Frankfurter Buchmesse Unternehmern, Verlegern, Gründern, Vordenkern, Experten und Visionären ideale Voraussetzungen für ihr Geschäft. Die Frankfurter Buchmesse ist ein Tochterunternehmen des Börsenvereins des Deutschen Buchhandels. www.buchmesse.de

# Mehr über die Frankfurter Buchmesse

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, - Book News, - Bookstores, Art & Literature News, AUDIO, CINEMA, RADIO & TV, Literary Events, THEATRE

William Shakespeare

(1564-1616)

To-morrow

To-morrow, and to-morrow, and to-morrow,

Creeps in this petty pace from day to day

To the last syllable of recorded time,

And all our yesterdays have lighted fools

The way to dusty death. Out, out, brief candle!

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage

And then is heard no more: it is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.

William Shakespeare, “Macbeth”, Act 5 scene 5

Shakespeare 400 (1616 – 2016)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Shakespeare, William

DOREHAMI

ددووررههممیی

A GROUP SHOW

No Man’s Art Gallery brings

Iranian emerging art to Amsterdam

15 October – 20 November 2016

Majid Biglari

Mehrdad Jafari

Shirin Mohammad

Sam Salehi Samiee

Arya Tabandehpoor

Sepide Zamani

No Man’s Art Gallery (NMAG) is a young Amsterdam-based gallery that has been organizing pop-up galleries in the unlikeliest of locations all over the world since 2011. The gallery aims to create an alternative art world in which artists can be free of any circumstances that might limit them at home, enabling them to seek a maximum of dialogue and exchange with an audience abroad.

In May 2016 the Dutch NMAG team travelled to Iran and organised exhibitions in Tehran as part of its ninth international pop-up gallery. The gallery selected six Iranian emerging artists after mapping the Tehran art scene and exhibited their work alongside the 18 international artists they brought to the Iranian capital. The pop-up gallery became the centre of attention in the Tehran art world for the ten days that it was open and a point of departure for a series of collaborative efforts between No Man’s Art Gallery and Iranian artists and art professionals.

For the first in the series of collaborations No Man’s Art Gallery invited the following artists to exhibit their work in Amsterdam: Majid Biglari, Mehrdad Jafari, Shirin Mohammad, Sam Salehi Samiee (nominee of the Royal Award of Modern Painting), Arya Tabandehpoor and Sepide Zamani.

Dorehami opens Friday October 14th in presence of the artists at the Nieuwe Herengracht 123 in Amsterdam.

Dorehami opens Friday October 14th in presence of the artists at the Nieuwe Herengracht 123 in Amsterdam.

The Farsi expression “Dorehami” is literally translated to “surrounded by each other” most commonly used by the younger generation to gather and hang out. Generally, the “Dorehami” takes place in the private sphere, which allows different rules of behaviour. Preparing the pop-up gallery in Tehran, this type of social gathering allowed the gallery team a more open engagement and interaction and provided access to a vibrant art scene driven by a young generation that experiences a post-revolution and post-war period, witnesses many social changes and gains ever more access to global tendencies in a time of digitalisation.

Dorehami gathers narratives that touch upon a wide range of subjects and use of media such as the limitations of the medium of photography, the rejection of authorship and investigations of collective memory. Artists present representations of daily issues, and address propaganda and nostalgic imagery in their work. They dare to celebrate ornament(ality) and decorum. Some are occupied with archival and found footage and the ambiguities of history while others show an interest in the possibilities of new technologies and digital forms of expression.

Altogether the exhibition creates a space to share stories and continues the dialogue in Amsterdam that started in Tehran. Emphasising the “Dorehami” as an occasion to introduce the artists and the Tehran art world to the Dutch audience, No Man’s Art Gallery has programmed a number of events surrounding the exhibition (for full programme, visit www.nomansart.com).

No Man’s Art Gallery

Nieuwe Herengracht 123,

Amsterdam

Exhibition Duration:

15 October – 20 November 2016

open FriSun, 11h00 - 18h00

No Man’s Art Gallery hosts a number of events surrounding the exhibition.

# More information on website No Man’s Art Gallery

photos © HU Jiahui (still from War no.2 by Shirin Mohammad & The slide project by Arya Tabandehpoor)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Art & Literature News, Exhibition Archive, FDM Art Gallery, Persian Art

The Man Without a Temperament

The Man Without a Temperament

by Katherine Mansfield

He stood at the hall door turning the ring, turning the heavy signet ring upon his little finger while his glance travelled coolly, deliberately, over the round tables and basket chairs scattered about the glassed-in veranda. He pursed his lips-he might have been going to whistle-but he did not whistle-only turned the ring-turned the ring on his pink, freshly washed hands.

Over in the corner sat The Two Topknots, drinking a decoction they always drank at this hour-something whitish, greyish, in glasses, with little husks floating on the top-and rooting in a tin full of paper shavings for pieces of speckled biscuit, which they broke, dropped into the glasses and fished for with spoons. Their two coils of knitting, like two snakes, slumbered beside the tray.

The American Woman sat where she always sat against the glass wall, in the shadow of a great creeping thing with wide open purple eyes that pressed-that flattened itself against the glass, hungrily watching her. And she knoo it was there-she knoo it was looking at her just that way. She played up to it; she gave herself little airs. Sometimes she even pointed at it, crying: “Isn’t that the most terrible thing you’ve ever seen! Isn’t that ghoulish!” It was on the other side of the veranda, after all . . . and besides it couldn’t touch her, could it, Klaymongso? She was an American Woman, wasn’t she, Klaymongso, and she’d just go right away to her Consul. Klaymongso, curled in her lap, with her torn antique brocade bag, a grubby handkerchief, and a pile of letters from home on top of him, sneezed for reply.

The other tables were empty. A glance passed between the American and the Topknots. She gave a foreign little shrug; they waved an understanding biscuit. But he saw nothing. Now he was still, now from his eyes you saw he listened. “Hoo-e-zip-zoo-oo!” sounded the lift. The iron cage clanged open. Light dragging steps sounded across the hall, coming towards him. A hand, like a leaf, fell on his shoulder. A soft voice said: “Let’s go and sit over there-where we can see the drive. The trees are so lovely.” And he moved forward with the hand still on his shoulder, and the light, dragging steps beside his. He pulled out a chair and she sank into it, slowly, leaning her head against the back, her arms falling along the sides.

“Won’t you bring the other up closer? It’s such miles away.” But he did not move.

“Where’s your shawl?” he asked.

“Oh!” She gave a little groan of dismay. “How silly I am, I’ve left it upstairs on the bed. Never mind. Please don’t go for it. I shan’t want it, I know I shan’t.”

“You’d better have it.” And he turned and swiftly crossed the veranda into the dim hall with its scarlet plush and gilt furniture-conjuror’s furniture-its Notice of Services at the English Church, its green baize board with the unclaimed letters climbing the black lattice, huge “Presentation” clock that struck the hours at the half-hours, bundles of sticks and umbrellas and sunshades in the clasp of a brown wooden bear, past the two crippled palms, two ancient beggars at the foot of the staircase, up the marble stairs three at a time, past the life-size group on the landing of two stout peasant children with their marble pinnies full of marble grapes, and along the corridor, with its piled-up wreckage of old tin boxes, leather trunks, canvas holdalls, to their room.

The servant girl was in their room, singing loudly while she emptied soapy water into a pail. The windows were open wide, the shutters put back, and the light glared in. She had thrown the carpets and the big white pillows over the balcony rails; the nets were looped up from the beds; on the writing-table there stood a pan of fluff and match-ends. When she saw him her small, impudent eyes snapped and her singing changed to humming. But he gave no sign. His eyes searched the glaring room. Where the devil was the shawl!

“Vous desirez, Monsieur? “ mocked the servant girl.

No answer. He had seen it. He strode across the room, grabbed the grey cobweb and went out, banging the door. The servant girl’s voice at its loudest and shrillest followed him along the corridor.

“Oh, there you are. What happened? What kept you? The tea’s here, you see. I’ve just sent Antonio off for the hot water. Isn’t it extraordinary? I must have told him about it sixty times at least, and still he doesn’t bring it. Thank you. That’s very nice. One does just feel the air when one bends forward.”

“Thanks.” He took his tea and sat down in the other chair. “No, nothing to eat.”

“Oh do! Just one, you had so little at lunch and it’s hours before dinner.”

Her shawl dropped off as she bent forward to hand him the biscuits. He took one and put it in his saucer.

“Oh, those trees along the drive,” she cried. “I could look at them for ever. They are like the most exquisite huge ferns. And you see that one with the grey-silver bark and the clusters of cream-coloured flowers, I pulled down a head of them yesterday to smell, and the scent”-she shut her eyes at the memory and her voice thinned away, faint, airy–“was like freshly ground nutmegs.” A little pause. She turned to him and smiled. “You do know what nutmegs smell like-do you Robert?”

And he smiled back at her. “Now how am I going to prove to you that I do?”

Back came Antonio with not only the hot water-with letters on a salver and three rolls of paper.

“Oh, the post! Oh, how lovely! Oh, Robert, they mustn’t be all for you! Have they just come, Antonio?” Her thin hands flew up and hovered over the letters that Antonio offered her, bending forward.

“Just this moment, Signora,” grinned Antonio. “I took-a them from the postman myself. I made-a the postman give them for me.”

“Noble Antonio!” laughed she. “There-those are mine, Robert; the rest are yours.”

Antonio wheeled sharply, stiffened, the grin went out of his face. His striped linen jacket and his flat gleaming fringe made him look like a wooden doll.

Mr. Salesby put the letters into his pocket; the papers lay on the table. He turned the ring, turned the signet ring on his little finger and stared in front of him, blinking, vacant.

But she-with her teacup in one hand, the sheets of thin paper in the other, her head tilted back, her lips open, a brush of bright colour on her cheek-bones, sipped, sipped, drank . . . drank.

“From Lottie,” came her soft murmur. “Poor dear . . . such trouble . . . left foot. She thought . . . neuritis . . . Doctor Blyth . . . flat foot . . . massage. So many robins this year . . . maid most satisfactory . . . Indian Colonel . . . every grain of rice separate . . . very heavy fall of snow.” And her wide lighted eyes looked up from the letter. “Snow, Robert! Think of it!” And she touched the little dark violets pinned on her thin bosom and went back to the letter.

. . . Snow. Snow in London. Millie with the early morning cup of tea. “There’s been a terrible fall of snow in the night, sir.” “Oh, has there, Millie?” The curtains ring apart, letting in the pale, reluctant light. He raises himself in the bed; he catches a glimpse of the solid houses opposite framed in white, of their window boxes full of great sprays of white coral . . . . In the bathroom-overlooking the back garden. Snow-heavy snow over everything. The lawn is covered with a wavy pattern of cat’s -paws; there is a thick, thick icing on the garden table; the withered pods of the laburnum tree are white tassels; only here and there in the ivy is a dark leaf showing. . . . Warming his back at the dining-room fire, the paper drying over a chair. Millie with the bacon. “Oh, if you please, Sir, there’s two little boys come as will do the steps and front for a shilling, shall I let them?” . . . And then flying lightly, lightly down the stairs–Jinnie. “Oh, Robert, isn’t it wonderful! Oh, what a pity it has to melt. Where’s the pussy-wee?” “I’ll get him from Millie.” . . . “Millie, you might just hand me up the kitten if you’ve got him down there.” “Very good, sir.” He feels the little beating heart under his hand. “Come on, old chap, your missus wants you.” “Oh, Robert, do show him the snow-his first snow. Shall I open the window and give him a little piece on his paw to hold? . . . ”

“Well, that’s very satisfactory on the whole-very. Poor Lottie! Darling Anne! How I only wish I could send them something of this,” she cried, waving her letters at the brilliant, dazzling garden. “More tea, Robert? Robert dear, more tea?”

“No, thanks, no. It was very good,” he drawled.

“Well, mine wasn’t. Mine was just like chopped hay. Oh, here comes the Honeymoon Couple.”

Half striding, half running, carrying a basket between them and rods and lines, they came up the drive, up the shallow steps.

“My! have you been out fishing?” cried the American Woman. They were out of breath, they panted: “Yes, yes, we have been out in a little boat all day. We have caught seven. Four are good to eat. But three we shall give away. To the children.”

Mrs. Salesby turned her chair to look; the Topknots laid the snakes down. They were a very dark young couple-black hair, olive skin, brilliant eyes and teeth. He was dressed “English fashion” in a flannel jacket, white trousers and shoes. Round his neck he wore a silk scarf; his head, with his hair brushed back, was bare. And he kept mopping his forehead, rubbing his hands with a brilliant handkerchief. Her white skirt had a patch of wet; her neck and throat were stained a deep pink. When she lifted her arms big half-hoops of perspiration showed under her arm-pits; her hair clung in wet curls to her cheeks. She looked as though her young husband had been dipping her in the sea and fishing her out again to dry in the sun and then-in with her again-all day.

“Would Klaymongso like a fish?” they cried. Their laughing voices charged with excitement beat against the glassed-in veranda like birds and a strange, saltish smell came from the basket.

“You will sleep well tonight,” said a Topknot, picking her ear with a knitting needle while the other Topknot smiled and nodded.

The Honeymoon Couple looked at each other. A great wave seemed to go over them. They gasped, gulped, staggered a little and then came up laughing-laughing.

“We cannot go upstairs, we are too tired. We must have tea just as we are. Here-coffee. No-tea. No-coffee. Tea-coffee, Antonio!” Mrs. Salesby turned.

“Robert! Robert!” Where was he? He wasn’t there. Oh, there he was at the other end of the veranda, with his back turned, smoking a cigarette. “Robert, shall we go for our little turn?”

“Right.” He stumped the cigarette into an ash-tray and sauntered over, his eyes on the ground. “Will you be warm enough?”

“Oh, quite.”

“Sure?”

“Well,” she put her hand on his arm, “perhaps”-and gave his arm the faintest pressure–“it’s not upstairs, it’s only in the hall-perhaps you’d get me my cape. Hanging up.”

He came back with it and she bent her small head while he dropped it on her shoulders. Then, very stiff, he offered her his arm. She bowed sweetly to the people of the veranda while he just covered a yawn, and they went down the steps together.

“Vous avez voo ca! “ said the American Woman.

“He is not a man,” said the Two Topknots, “he is an ox. I say to my sister in the morning and at night when we are in bed, I tell her–No man is he, but an ox!”

Wheeling, tumbling, swooping, the laughter of the Honeymoon Couple dashed against the glass of the veranda.

The sun was still high. Every leaf, every flower in the garden lay open, motionless, as if exhausted, and a sweet, rich, rank smell filled the quivering air. Out of the thick, fleshy leaves of a cactus there rose an aloe stem loaded with pale flowers that looked as though they had been cut out of butter; light flashed upon the lifted spears of the palms; over a bed of scarlet waxen flowers some black insects “zoom-zoomed”; a great, gaudy creeper, orange splashed with jet, sprawled against the wall.

“I don’t need my cape after all,” said she. “It’s really too warm.” So he took it off and carried it over his arm. “Let us go down this path here. I feel so well today-marvellously better. Good heavens-look at those children! And to think it’s November!”

In a corner of the garden there were two brimming tubs of water. Three little girls, having thoughtfully taken off their drawers and hung them on a bush, their skirts clasped to their waists, were standing in the tubs and tramping up and down. They screamed, their hair fell over their faces, they splashed one another. But suddenly, the smallest, who had a tub to herself, glanced up and saw who was looking. For a moment she seemed overcome with terror, then clumsily she struggled and strained out of her tub, and still holding her clothes above her waist, “The Englishman! The Englishman!” she shrieked and fled away to hide. Shrieking and screaming the other two followed her. In a moment they were gone; in a moment there was nothing but the two brimming tubs and their little drawers on the bush.

“How-very-extraordinary!” said she. “What made them so frightened? Surely they were much too young to . . . “ She looked up at him. She thought he looked pale-but wonderfully handsome with that great tropical tree behind him with its long, spiked thorns.

For a moment he did not answer. Then he met her glance, and smiling his slow smile, ”Très rum!” said he.

Très rum! Oh, she felt quite faint. Oh, why should she love him so much just because he said a thing like that. Très rum! That was Robert all over. Nobody else but Robert could ever say such a thing. To be so wonderful, so brilliant, so learned, and then to say in that queer, boyish voice . . . She could have wept.

“You know you’re very absurd, sometimes,” said she.

“I am,” he answered. And they walked on.

But she was tired. She had had enough. She did not want to walk any more.

“Leave me here and go for a little constitutional, won’t you? I’ll be in one of these long chairs. What a good thing you’ve got my cape; you won’t have to go upstairs for a rug. Thank you, Robert, I shall look at that delicious heliotrope. . . . You won’t be gone long?”

“No-no. You don’t mind being left?”

“Silly! I want you to go. I can’t expect you to drag after your invalid wife every minute . . . . How long will you be?”

He took out his watch. “It’s just after half-past four. I’ll be back at a quarter-past five.”

“Back at a quarter-past five,” she repeated, and she lay still in the long chair and folded her hands.

He turned away. Suddenly he was back again. “Look here, would you like my watch?” And he dangled it before her.

“Oh!” She caught her breath. “Very, very much.” And she clasped the watch, the warm watch, the darling watch in her fingers. “Now go quickly.”

The gates of the Pension Villa Excelsior were open wide, jammed open against some bold geraniums. Stooping a little, staring straight ahead, walking swiftly, he passed through them and began climbing the hill that wound behind the town like a great rope looping the villas together. The dust lay thick. A carriage came bowling along driving towards the Excelsior. In it sat the General and the Countess; they had been for his daily airing. Mr. Salesby stepped to one side but the dust beat up, thick, white, stifling like wool. The Countess just had time to nudge the General.

“There he goes,” she said spitefully.

But the General gave a loud caw and refused to look.

“It is the Englishman,” said the driver, turning round and smiling. And the Countess threw up her hands and nodded so amiably that he spat with satisfaction and gave the stumbling horse a cut.

On-on-past the finest villas in the town, magnificent palaces, palaces worth coming any distance to see, past the public gardens with the carved grottoes and statues and stone animals drinking at the fountain, into a poorer quarter. Here the road ran narrow and foul between high lean houses, the ground floors of which were scooped and hollowed into stables and carpenters’ shops. At a fountain ahead of him two old hags were beating linen. As he passed them they squatted back on their haunches, stared, and then their “A-hak-kak-kak!” with the slap, slap, of the stone on the linen sounded after him.

He reached the top of the hill; he turned a corner and the town was hidden. Down he looked into a deep valley with a dried-up river bed at the bottom. This side and that was covered with small dilapidated houses that had broken stone verandas where the fruit lay drying, tomato lanes in the garden and from the gates to the doors a trellis of vines. The late sunlight, deep, golden, lay in the cup of the valley; there was a smell of charcoal in the air. In the gardens the men were cutting grapes. He watched a man standing in the greenish shade, raising up, holding a black cluster in one hand, taking the knife from his belt, cutting, laying the bunch in a flat boat-shaped basket. The man worked leisurely, silently, taking hundreds of years over the job. On the hedges on the other side of the road there were grapes small as berries, growing among the stones. He leaned against a wall, filled his pipe, put a match to it . . . .

Leaned across a gate, turned up the collar of his mackintosh. It was going to rain. It didn’t matter, he was prepared for it. You didn’t expect anything else in November. He looked over the bare field. From the corner by the gate there came the smell of swedes, a great stack of them, wet, rank coloured. Two men passed walking towards the straggling village. “Good day!” “Good day!” By Jove! he had to hurry if he was going to catch that train home. Over the gate, across a field, over the stile, into the lane, swinging along in the drifting rain and dusk . . . . Just home in time for a bath and a change before supper. . . . In the drawing-room; Jinnie is sitting pretty nearly in the fire. “Oh, Robert, I didn’t hear you come in. Did you have a good time? How nice you smell! A present?” “Some bits of blackberry I picked for you. Pretty colour.” “Oh, lovely, Robert! Dennis and Beaty are coming to supper.” Supper-cold beef, potatoes in their jackets, claret, household bread. They are gay– everybody’s laughing. “Oh, we all know Robert,” says Dennis, breathing on his eyeglasses and polishing them. “By the way, Dennis, I picked up a very jolly little edition of . . . ”

A clock struck. He wheeled sharply. What time was it. Five? A quarter past? Back, back the way he came. As he passed through the gates he saw her on the look-out. She got up, waved and slowly she came to meet him, dragging the heavy cape. In her hand she carried a spray of heliotrope.

“You’re late,” she cried gaily. “You’re three minutes late. Here’s your watch, it’s been very good while you were away. Did you have a nice time? Was it lovely? Tell me. Where did you go?”

“I say-put this on,” he said, taking the cape from her. “Yes, I will. Yes, it’s getting chilly. Shall we go up to our room?”

When they reached the lift she was coughing. He frowned.

“It’s nothing. I haven’s been out too late. Don’t be cross.” She sat down on one of the red plush chairs while he rang and rang, and then, getting no answer, kept his finger on the bell.

“Oh, Robert, do you think you ought to?”

“Ought to what?”

The door of the salon opened. “What is that? Who is making that noise?” sounded from within. Klaymongso began to yelp. “Caw! Caw! Caw!” came from the General. A Topknot darted out with one hand to her ear, opened the staff door, “Mr. Queet! Mr. Queet!” she bawled. That brought the manager up at a run.

“Is that you ringing the bell, Mr. Salesby? Do you want the lift? Very good, sir. I’ll take you up myself. Antonio wouldn’t have been a minute, he was just taking off his apron–” And having ushered them in, the oily manager went to the door of the salon. “Very sorry you should have been troubled, ladies and gentlemen.” Salesby stood in the cage, sucking in his cheeks, staring at the ceiling and turning the ring, turning the signet ring on his little finger . . . .

Arrived in their room he went swiftly over to the washstand, shook the bottle, poured her out a dose and brought it across.

“Sit down. Drink it. And don’t talk.” And he stood over her while she obeyed. Then he took the glass, rinsed it and put it back in its case. “Would you like a cushion?”

“No, I’m quite all right, come over here. Sit down by me just a minute, will you, Robert? Ah, that’s very nice.” She turned and thrust the piece of heliotrope in the lapel of his coat. “That,” she said, “is most becoming.” And then she leaned her head against his shoulder and he put his arm round her.

“Robert–” her voice like a sigh-like a breath.

“Yes–”

They sat there for a long while. The sky flamed, paled; the two white beds were like two ships . . . . At last he heard the servant girl running along the corridor with the hot-water cans, and gently he released her and turned on the light.

“Oh, what time is it? Oh, what a heavenly evening. Oh, Robert, I was thinking while you were away this afternoon . . . “

They were the last couple to enter the dining-room. The Countess was there with her lorgnette and her fan, the General was there with his special chair and the air cushion and the small rug over his knees. The American Woman was there showing Klaymongso a copy of the Saturday Evening Post . . . “We’re having a feast of reason and a flow of soul.” The Two Topknots were there feeling over the peaches and the pears in their dish of fruit and putting aside all they considered unripe or overripe to show to the manager, and the Honeymoon Couple leaned across the table, whispering, trying not to burst out laughing.

Mr. Queet, in everyday clothes and white canvas shoes, served the soup, and Antonio, in full evening dress, handed it round.

“No,” said the American Woman, “take it away, Antonio. We can’t eat soup. We can’t eat anything mushy, can we, Klaymongso?”

“Take them back and fill them to the rim!” said the Topknots, and they turned and watched while Antonio delivered the message.

“What is it? Rice? Is it cooked?” The Countess peered through her lorgnette. “Mr. Queet, the General can have some of this soup if it is cooked.”

“Very good, Countess.”

The Honeymoon Couple had their fish instead.

“Give me that one. That’s the one I caught. No, it’s not. Yes, it is. No, it’s not. Well, it’s looking at me with its eye, so it must be. Tee! Hee! Hee!” Their feet were locked together under the table.

“Robert, you’re not eating again. Is anything the matter?”

“No. Off food, that’s all.”

“Oh, what a bother. There are eggs and spinach coming. You don’t like spinach, do you. I must tell them in future . . . “

An egg and mashed potatoes for the General.

“Mr. Queet! Mr. Queet!”

“Yes, Countess.”

“The General’s egg’s too hard again.”

“Caw! Caw! Caw!”

“Very sorry, Countess. Shall I have you another cooked, General?”

. . . They are the first to leave the dining-room. She rises, gathering her shawl and he stands aside, waiting for her to pass, turning the ring, turning the signet ring on his little finger. In the hall Mr. Queet hovers. “I thought you might not want to wait for the lift. Antonio’s just serving the finger bowls. And I’m sorry the bell won’t ring, it’s out of order. I can’t think what’s happened.”

“Oh, I do hope . . . “ from her.

“Get in,” says he.

Mr. Queet steps after them and slams the door . . . .

. . . “Robert, do you mind if I go to bed very soon? Won’t you go down to the salon or out into the garden? Or perhaps you might smoke a cigar on the balcony. It’s lovely out there. And I like cigar smoke. I always did. But if you’d rather . . . ”

“No, I’ll sit here.”

He takes a chair and sits on the balcony. He hears her moving about in the room, lightly, lightly, moving and rustling. Then she comes over to him. “Good night, Robert.”

“Good night.” He takes her hand and kisses the palm. “Don’t catch cold.”

The sky is the colour of jade. There are a great many stars; an enormous white moon hangs over the garden. Far away lightning flutters-flutters like a wing-flutters like a broken bird that tries to fly and sinks again and again struggles.

The lights from the salon shine across the garden path and there is the sound of a piano. And once the American Woman, opening the French window to let Klaymongso into the garden, cries: “Have you seen this moon?” But nobody answers.

He gets very cold sitting there, staring at the balcony rail. Finally he comes inside. The moon-the room is painted white with moonlight. The light trembles in the mirrors; the two beds seem to float. She is asleep. He sees her through the nets, half sitting, banked up with pillows, her white hands crossed on the sheet, her white cheeks, her fair hair pressed against the pillow, are silvered over. He undresses quickly, stealthily and gets into bed. Lying there, his hands clasped behind his head . . .

. . . In his study. Late summer. The virginia creeper just on the turn . . . .

“Well, my dear chap, that’s the whole story. That’s the long and the short of it. If she can’t cut away for the next two years and give a decent climate a chance she don’t stand a dog’s -h’m-show. Better be frank about these things.” “Oh, certainly . . . . “ “And hang it all, old man, what’s to prevent you going with her? It isn’t as though you’ve got a regular job like us wage earners. You can do what you do wherever you are–” “Two years.” “Yes, I should give it two years. You’ll have no trouble about letting this house, you know. As a matter of fact . . . ”

. . . He is with her. “Robert, the awful thing is–I suppose it’s my illness–I simply feel I could not go alone. You see-you’re everything. You’re bread and wine, Robert, bread and wine. Oh, my darling-what am I saying? Of course I could, of course I won’t take you away. . . . ”

He hears her stirring. Does she want something?

“Boogles?”

Good Lord! She is talking in her sleep. They haven’t used that name for years.

“Boogles. Are you awake?”

“Yes, do you want anything?”

“Oh, I’m going to be a bother. I’m so sorry. Do you mind? There’s a wretched mosquito inside my net–I can hear him singing. Would you catch him? I don’t want to move because of my heart.”

“No, don’t move. Stay where you are.” He switches on the light, lifts the net. “Where is the little beggar? Have you spotted him?”

“Yes, there, over by the corner. Oh, I do feel such a fiend to have dragged you out of bed. Do you mind dreadfully?”

“No, of course not.” For a moment he hovers in his blue and white pyjamas. Then, “got him,” he said.

“Oh, good. Was he a juicy one?”

“Beastly.” He went over to the washstand and dipped his fingers in water. “Are you all right now? Shall I switch off the light?”

“Yes, please. No. Boogles! Come back here a moment. Sit down by me. Give me your hand.” She turns his signet ring. “Why weren’t you asleep? Boogles, listen. Come closer. I sometimes wonder-do you mind awfully being out here with me?”

He bends down. He kisses her. He tucks her in, he smooths the pillow.

“Rot!” he whispers.

The Man Without a Temperament

by Katherine Mansfield (1888 – 1923)

From: Bliss, and other stories

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive M-N, Katherine Mansfield, Mansfield, Katherine

The Nobel Prize in Literature 2016

Bob Dylan

The Nobel Prize in Literature for 2016 is awarded to Bob Dylan: “for having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition”.

Bob Dylan Albums

Bob Dylan (1962)

The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan (1963)

The Times They Are A-Changin’ (1964)

Another Side Of Bob Dylan (1964)

Bringing It All Back Home (1965)

Highway 61 Revisited (1965)

Blonde On Blonde (1966)

Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits (1967)

John Wesley Harding (1968)

Nashville Skyline (1969)

Self Portrait (1970)

New Morning (1970)

Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits Vol. 2 (1971)

Pat Garrett & Billy The Kid (1973)

Dylan (1973)

Planet Waves (1974)

Before The Flood (1974)

Blood On The Tracks (1975)

The Basement Tapes (1975)

Desire (1976)

Hard Rain (1976)

Street Legal (1978)

Bob Dylan At Budokan (1978)

Slow Train Coming (1979)

Saved (1980)

Shot Of Love (1981)

Infidels (1983)

Real Live (1984)

Empire Burlesque (1985)

Biograph (1985)

Knocked Out Loaded (1986)

Down In The Groove (1988)

Dylan & The Dead (1989)

Oh Mercy (1989)

Under The Red Sky (1990)

The Bootleg Series Vols. 1-3: Rare And Unreleased 1961-1991 (1991)

Good As I Been to You (1992)

World Gone Wrong (1993)

Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits Vol. 3 (1994)

MTV Unplugged (1995)

The Best Of Bob Dylan (1997)

The Songs Of Jimmie Rodgers: A Tribute (1997)

Time Out Of Mind (1997)

The Bootleg Series, Vol. 4: Bob Dylan Live 1966: The ’Royal Albert Hall’ Concert (1998)

The Essential Bob Dylan (2000)

”Love And Theft” (2001)

The Bootleg Series, Vol. 5: Live 1975: The Rolling Thunder Revue (2002)

Masked And Anonymous: The Soundtrack (2003)

Gotta Serve Somebody: The Gospel Songs Of Bob Dylan (2003)

The Bootleg Series, Vol. 6: Live 1964: Concert At Philharmonic Hall (2004)

The Bootleg Series, Vol. 7: No Direction Home: The Soundtrack (2005)

Live At The Gaslight 1962 (2005)

Live At Carnegie Hall 1963 (2005)

Modern Times (2006)

The Traveling Wilburys Collection (2007)

The Bootleg Series, Vol. 8: Tell Tale Signs: Rare And Unreleased, 1989-2006 (2008)

Together Through Life (2009)

Christmas In The Heart (2009)

The Original Mono Recordings (2010)

The Bootleg Series, Vol. 9: The Witmark Demos: 1962-1964 (2010)

Good Rockin’ Tonight: The Legacy Of Sun (2011)

Timeless (2011)

Tempest (2012)

The Lost Notebooks Of Hank Williams (2011)

The Bootleg Series, Vol. 10: Another Self Portrait (2013)

The Bootleg Series, Vol. 11: The Basement Tapes Complete (2014)

The Bootleg Series, Vol. 12: The Cutting Edge 1965-1966 (2015)

Shadows In The Night (2015)

Fallen Angels (2016)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

13 oct. 2016

More in: Archive C-D, Art & Literature News, Awards & Prizes, Bob Dylan, Dylan, Bob, Literary Events

The Third Generation

The Third Generation

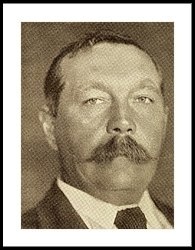

by Arthur Conan Doyle

Scudamore Lane, sloping down riverwards from just behind the Monument, lies at night in the shadow of two black and monstrous walls which loom high above the glimmer of the scattered gas lamps. The footpaths are narrow, and the causeway is paved with rounded cobblestones, so that the endless drays roar along it like breaking waves. A few old-fashioned houses lie scattered among the business premises, and in one of these, half-way down on the left-hand side, Dr. Horace Selby conducts his large practice. It is a singular street for so big a man; but a specialist who has an European reputation can afford to live where he likes. In his particular branch, too, patients do not always regard seclusion as a disadvantage.

It was only ten o’clock. The dull roar of the traffic which converged all day upon London Bridge had died away now to a mere confused murmur. It was raining heavily, and the gas shone dimly through the streaked and dripping glass, throwing little circles upon the glistening cobblestones. The air was full of the sounds of the rain, the thin swish of its fall, the heavier drip from the eaves, and the swirl and gurgle down the two steep gutters and through the sewer grating. There was only one figure in the whole length of Scudamore Lane. It was that of a man, and it stood outside the door of Dr. Horace Selby.

He had just rung and was waiting for an answer. The fanlight beat full upon the gleaming shoulders of his waterproof and upon his upturned features. It was a wan, sensitive, clear-cut face, with some subtle, nameless peculiarity in its expression, something of the startled horse in the white-rimmed eye, something too of the helpless child in the drawn cheek and the weakening of the lower lip. The man-servant knew the stranger as a patient at a bare glance at those frightened eyes. Such a look had been seen at that door many times before.

“Is the doctor in?”

The man hesitated.

“He has had a few friends to dinner, sir. He does not like to be disturbed outside his usual hours, sir.”

“Tell him that I MUST see him. Tell him that it is of the very first importance. Here is my card.” He fumbled with his trembling fingers in trying to draw one from his case. “Sir Francis Norton is the name. Tell him that Sir Francis Norton, of Deane Park, must see him without delay.”

“Yes, sir.” The butler closed his fingers upon the card and the half-sovereign which accompanied it. “Better hang your coat up here in the hall. It is very wet. Now if you will wait here in the consulting-room, I have no doubt that I shall be able to send the doctor in to you.”

It was a large and lofty room in which the young baronet found himself. The carpet was so soft and thick that his feet made no sound as he walked across it. The two gas jets were turned only half-way up, and the dim light with the faint aromatic smell which filled the air had a vaguely religious suggestion. He sat down in a shining leather armchair by the smouldering fire and looked gloomily about him. Two sides of the room were taken up with books, fat and sombre, with broad gold lettering upon their backs. Beside him was the high, old-fashioned mantelpiece of white marble—the top of it strewed with cotton wadding and bandages, graduated measures, and little bottles. There was one with a broad neck just above him containing bluestone, and another narrower one with what looked like the ruins of a broken pipestem and “Caustic” outside upon a red label. Thermometers, hypodermic syringes bistouries and spatulas were scattered about both on the mantelpiece and on the central table on either side of the sloping desk. On the same table, to the right, stood copies of the five books which Dr. Horace Selby had written upon the subject with which his name is peculiarly associated, while on the left, on the top of a red medical directory, lay a huge glass model of a human eye the size of a turnip, which opened down the centre to expose the lens and double chamber within.

Sir Francis Norton had never been remarkable for his powers of observation, and yet he found himself watching these trifles with the keenest attention. Even the corrosion of the cork of an acid bottle caught his eye, and he wondered that the doctor did not use glass stoppers. Tiny scratches where the light glinted off from the table, little stains upon the leather of the desk, chemical formulae scribbled upon the labels of the phials—nothing was too slight to arrest his attention. And his sense of hearing was equally alert. The heavy ticking of the solemn black clock above the mantelpiece struck quite painfully upon his ears. Yet in spite of it, and in spite also of the thick, old-fashioned wooden partition, he could hear voices of men talking in the next room, and could even catch scraps of their conversation. “Second hand was bound to take it.” “Why, you drew the last of them yourself!”

“How could I play the queen when I knew that the ace was against me?” The phrases came in little spurts falling back into the dull murmur of conversation. And then suddenly he heard the creaking of a door and a step in the hall, and knew with a tingling mixture of impatience and horror that the crisis of his life was at hand.

Dr. Horace Selby was a large, portly man with an imposing presence. His nose and chin were bold and pronounced, yet his features were puffy, a combination which would blend more freely with the wig and cravat of the early Georges than with the close-cropped hair and black frock-coat of the end of the nineteenth century. He was clean shaven, for his mouth was too good to cover—large, flexible, and sensitive, with a kindly human softening at either corner which with his brown sympathetic eyes had drawn out many a shame-struck sinner’s secret. Two masterful little bushy side-whiskers bristled out from under his ears spindling away upwards to merge in the thick curves of his brindled hair. To his patients there was something reassuring in the mere bulk and dignity of the man. A high and easy bearing in medicine as in war bears with it a hint of victories in the past, and a promise of others to come. Dr. Horace Selby’s face was a consolation, and so too were the large, white, soothing hands, one of which he held out to his visitor.

“I am sorry to have kept you waiting. It is a conflict of duties, you perceive—a host’s to his guests and an adviser’s to his patient. But now I am entirely at your disposal, Sir Francis. But dear me, you are very cold.”

“Yes, I am cold.”

“And you are trembling all over. Tut, tut, this will never do! This miserable night has chilled you. Perhaps some little stimulant——”

“No, thank you. I would really rather not. And it is not the night which has chilled me. I am frightened, doctor.”

The doctor half-turned in his chair, and he patted the arch of the young man’s knee, as he might the neck of a restless horse.

“What then?” he asked, looking over his shoulder at the pale face with the startled eyes.

Twice the young man parted his lips. Then he stooped with a sudden gesture, and turning up the right leg of his trousers he pulled down his sock and thrust forward his shin. The doctor made a clicking noise with his tongue as he glanced at it.

“Both legs?”

“No, only one.”

“Suddenly?”

“This morning.”

“Hum.”

The doctor pouted his lips, and drew his finger and thumb down the line of his chin. “Can you account for it?” he asked briskly.

“No.”

A trace of sternness came into the large brown eyes.

“I need not point out to you that unless the most absolute frankness——”

The patient sprang from his chair. “So help me God!” he cried, “I have nothing in my life with which to reproach myself. Do you think that I would be such a fool as to come here and tell you lies. Once for all, I have nothing to regret.” He was a pitiful, half-tragic and half-grotesque figure, as he stood with one trouser leg rolled to the knee, and that ever present horror still lurking in his eyes. A burst of merriment came from the card-players in the next room, and the two looked at each other in silence.

“Sit down,” said the doctor abruptly, “your assurance is quite sufficient.” He stooped and ran his finger down the line of the young man’s shin, raising it at one point. “Hum, serpiginous,” he murmured, shaking his head. “Any other symptoms?”

“My eyes have been a little weak.”

“Let me see your teeth.” He glanced at them, and again made the gentle, clicking sound of sympathy and disapprobation.

“Now your eye.” He lit a lamp at the patient’s elbow, and holding a small crystal lens to concentrate the light, he threw it obliquely upon the patient’s eye. As he did so a glow of pleasure came over his large expressive face, a flush of such enthusiasm as the botanist feels when he packs the rare plant into his tin knapsack, or the astronomer when the long-sought comet first swims into the field of his telescope.

“This is very typical—very typical indeed,” he murmured, turning to his desk and jotting down a few memoranda upon a sheet of paper. “Curiously enough, I am writing a monograph upon the subject. It is singular that you should have been able to furnish so well-marked a case.” He had so forgotten the patient in his symptom, that he had assumed an almost congratulatory air towards its possessor. He reverted to human sympathy again, as his patient asked for particulars.

“My dear sir, there is no occasion for us to go into strictly professional details together,” said he soothingly. “If, for example, I were to say that you have interstitial keratitis, how would you be the wiser? There are indications of a strumous diathesis. In broad terms, I may say that you have a constitutional and hereditary taint.”

The young baronet sank back in his chair, and his chin fell forwards upon his chest. The doctor sprang to a side-table and poured out half a glass of liqueur brandy which he held to his patient’s lips. A little fleck of colour came into his cheeks as he drank it down.

“Perhaps I spoke a little abruptly,” said the doctor, “but you must have known the nature of your complaint. Why, otherwise, should you have come to me?”

“God help me, I suspected it; but only today when my leg grew bad. My father had a leg like this.”

“It was from him, then——?”

“No, from my grandfather. You have heard of Sir Rupert Norton, the great Corinthian?”

The doctor was a man of wide reading with a retentive, memory. The name brought back instantly to him the remembrance of the sinister reputation of its owner—a notorious buck of the thirties—who had gambled and duelled and steeped himself in drink and debauchery, until even the vile set with whom he consorted had shrunk away from him in horror, and left him to a sinister old age with the barmaid wife whom he had married in some drunken frolic. As he looked at the young man still leaning back in the leather chair, there seemed for the instant to flicker up behind him some vague presentiment of that foul old dandy with his dangling seals, many-wreathed scarf, and dark satyric face. What was he now? An armful of bones in a mouldy box. But his deeds— they were living and rotting the blood in the veins of an innocent man.

“I see that you have heard of him,” said the young baronet. “He died horribly, I have been told; but not more horribly than he had lived. My father was his only son. He was a studious man, fond of books and canaries and the country; but his innocent life did not save him.”

“His symptoms were cutaneous, I understand.”

“He wore gloves in the house. That was the first thing I can remember. And then it was his throat. And then his legs. He used to ask me so often about my own health, and I thought him so fussy, for how could I tell what the meaning of it was. He was always watching me—always with a sidelong eye fixed upon me. Now, at last, I know what he was watching for.”

“Had you brothers or sisters?”

“None, thank God.”

“Well, well, it is a sad case, and very typical of many which come in my way. You are no lonely sufferer, Sir Francis. There are many thousands who bear the same cross as you do.”

“But where is the justice of it, doctor?” cried the young man, springing from his chair and pacing up and down the consulting-room. “If I were heir to my grandfather’s sins as well as to their results, I could understand it, but I am of my father’s type. I love all that is gentle and beautiful—music and poetry and art. The coarse and animal is abhorrent to me. Ask any of my friends and they would tell you that. And now that this vile, loathsome thing—ach, I am polluted to the marrow, soaked in abomination! And why? Haven’t I a right to ask why? Did I do it? Was it my fault? Could I help being born? And look at me now, blighted and blasted, just as life was at its sweetest. Talk about the sins of the father—how about the sins of the Creator?” He shook his two clinched hands in the air—the poor impotent atom with his pin-point of brain caught in the whirl of the infinite.

The doctor rose and placing his hands upon his shoulders he pressed him back into his chair once more. “There, there, my dear lad,” said he; “you must not excite yourself. You are trembling all over. Your nerves cannot stand it. We must take these great questions upon trust. What are we, after all? Half-evolved creatures in a transition stage, nearer perhaps to the Medusa on the one side than to perfected humanity on the other. With half a complete brain we can’t expect to understand the whole of a complete fact, can we, now? It is all very dim and dark, no doubt; but I think that Pope’s famous couplet sums up the whole matter, and from my heart, after fifty years of varied experience, I can say——”

But the young baronet gave a cry of impatience and disgust. “Words, words, words! You can sit comfortably there in your chair and say them—and think them too, no doubt. You’ve had your life, but I’ve never had mine. You’ve healthy blood in your veins; mine is putrid. And yet I am as innocent as you. What would words do for you if you were in this chair and I in that? Ah, it’s such a mockery and a make-believe! Don’t think me rude, though, doctor. I don’t mean to be that. I only say that it is impossible for you or any other man to realise it. But I’ve a question to ask you, doctor. It’s one on which my whole life must depend.” He writhed his fingers together in an agony of apprehension.

“Speak out, my dear sir. I have every sympathy with you.”

“Do you think—do you think the poison has spent itself on me? Do you think that if I had children they would suffer?”

“I can only give one answer to that. ‘The third and fourth generation,’ says the trite old text. You may in time eliminate it from your system, but many years must pass before you can think of marriage.”

“I am to be married on Tuesday,” whispered the patient.

It was the doctor’s turn to be thrilled with horror. There were not many situations which would yield such a sensation to his seasoned nerves. He sat in silence while the babble of the card-table broke in upon them again. “We had a double ruff if you had returned a heart.” “I was bound to clear the trumps.” They were hot and angry about it.

“How could you?” cried the doctor severely. “It was criminal.”

“You forget that I have only learned how I stand to-day.” He put his two hands to his temples and pressed them convulsively. “You are a man of the world, Dr. Selby. You have seen or heard of such things before. Give me some advice. I’m in your hands. It is all very sudden and horrible, and I don’t think I am strong enough to bear it.”

The doctor’s heavy brows thickened into two straight lines, and he bit his nails in perplexity.

“The marriage must not take place.”

“Then what am I to do?”

“At all costs it must not take place.”

“And I must give her up?”

“There can be no question about that.”

The young man took out a pocketbook and drew from it a small photograph, holding it out towards the doctor. The firm face softened as he looked at it.

“It is very hard on you, no doubt. I can appreciate it more now that I have seen that. But there is no alternative at all. You must give up all thought of it.”

“But this is madness, doctor—madness, I tell you. No, I won’t raise my voice. I forgot myself. But realise it, man. I am to be married on Tuesday. This coming Tuesday, you understand. And all the world knows it. How can I put such a public affront upon her. It would be monstrous.”

“None the less it must be done. My dear lad, there is no way out of it.”

“You would have me simply write brutally and break the engagement at the last moment without a reason. I tell you I couldn’t do it.”

“I had a patient once who found himself in a somewhat similar situation some years ago,” said the doctor thoughtfully. “His device was a singular one. He deliberately committed a penal offence, and so compelled the young lady’s people to withdraw their consent to the marriage.”

The young baronet shook his head. “My personal honour is as yet unstained,” said he. “I have little else left, but that, at least, I will preserve.”

“Well, well, it is a nice dilemma, and the choice lies with you.”

“Have you no other suggestion?”

“You don’t happen to have property in Australia?”

“None.”

“But you have capital?”

“Yes.”

“Then you could buy some. To-morrow morning would do. A thousand mining shares would be enough. Then you might write to say that urgent business affairs have compelled you to start at an hour’s notice to inspect your property. That would give you six months, at any rate.”

“Well, that would be possible. Yes, certainly, it would be possible. But think of her position. The house full of wedding presents—guests coming from a distance. It is awful. And you say that there is no alternative.”

The doctor shrugged his shoulders.

“Well, then, I might write it now, and start to-morrow—eh? Perhaps you would let me use your desk. Thank you. I am so sorry to keep you from your guests so long. But I won’t be a moment now.”

He wrote an abrupt note of a few lines. Then with a sudden impulse he tore it to shreds and flung it into the fireplace.

“No, I can’t sit down and tell her a lie, doctor,” he said rising. “We must find some other way out of this. I will think it over and let you know my decision. You must allow me to double your fee as I have taken such an unconscionable time. Now good-bye, and thank you a thousand times for your sympathy and advice.”

“Why, dear me, you haven’t even got your prescription yet. This is the mixture, and I should recommend one of these powders every morning, and the chemist will put all directions upon the ointment box. You are placed in a cruel situation, but I trust that these may be but passing clouds. When may I hope to hear from you again?”

“To-morrow morning.”

“Very good. How the rain is splashing in the street! You have your waterproof there. You will need it. Good-bye, then, until to-morrow.”

He opened the door. A gust of cold, damp air swept into the hall. And yet the doctor stood for a minute or more watching the lonely figure which passed slowly through the yellow splotches of the gas lamps, and into the broad bars of darkness between. It was but his own shadow which trailed up the wall as he passed the lights, and yet it looked to the doctor’s eye as though some huge and sombre figure walked by a manikin’s side and led him silently up the lonely street.

Dr. Horace Selby heard again of his patient next morning, and rather earlier than he had expected. A paragraph in the Daily News caused him to push away his breakfast untasted, and turned him sick and faint while he read it. “A Deplorable Accident,” it was headed, and it ran in this way:

“A fatal accident of a peculiarly painful character is reported from King William Street. About eleven o’clock last night a young man was observed while endeavouring to get out of the way of a hansom to slip and fall under the wheels of a heavy, two-horse dray. On being picked up his injuries were found to be of the most shocking character, and he expired while being conveyed to the hospital. An examination of his pocketbook and cardcase shows beyond any question that the deceased is none other than Sir Francis Norton, of Deane Park, who has only within the last year come into the baronetcy. The accident is made the more deplorable as the deceased, who was only just of age, was on the eve of being married to a young lady belonging to one of the oldest families in the South. With his wealth and his talents the ball of fortune was at his feet, and his many friends will be deeply grieved to know that his promising career has been cut short in so sudden and tragic a fashion.”

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859 – 1930)

Round the Red Lamp: Being Facts and Fancies of Medical Life

The Third Generation. (#04)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Doyle, Arthur Conan, Doyle, Arthur Conan, DRUGS & DISEASE & MEDICINE & LITERATURE, Round the Red Lamp

Op 9 Augustus sal dit presies vyfhonderd jaar wees dat die middeleeuse skilder Hieronymus Bosch oorlede is. Sy nalatenskap tel vierentwintig skilderye, twintig tekeninge en om nou maar ’n wilde sprong te maak: enkele Afrikaanse gedigte. Kenners kloof nogal hare oor die aantal skilderye en sketse. Versamelaars en museums se aansien en geld styg en val erger as op die aandelebeurs. Kontroversie en roem sorg daarvoor dat die 75 000 kaartjies wat gedruk is vir die tentoonstelling “Jheronimus Bosch – Visioenen van een genie” in ’s Hertogenbosch (Den Bosch) reeds uitverkoop is. Dié tentoonstelling duur tot 8 Mei. Op 31 Mei open die Nasionale Museum Prado in Madrid, met “Bosch – The Centenary Exhibition”.

As onderdeel van die vyfhonderd jaar vierings van Bosch se kunstenaarskap het sy Nederlandse geboortestad en die Noord-Brabants Museum saamgewerk om die Bosch Research and Conservation Project (BRCP) op te rig. Dit is hier waar wetenskap en kuns saamkom. En dít sorg vir beroering. Die BRCP is vyf jaar terug uit nood gestig om as ruilmiddel te dien vir soveel moontlik van Jeroen Bosch se oorspronklike werk met die oog op “ – Visioenen van een genie”. Daarvoor moes minstens museums soos die Prado, die Louvre in Parys en die National Art Gallery in London benader word. Dit was van die begin af duidelik dat Prado nie “De tuin der Lusten” – Bosch se meesterwerk – sou afstaan vir ´n tentoonstelling in Nederland of op enige ander plek nie. Te kwesbaar, was hulle verskoning. Bosch is eintlik ´n Spaanse skilder in hulle oë. Hulle noem hom El Bosco.

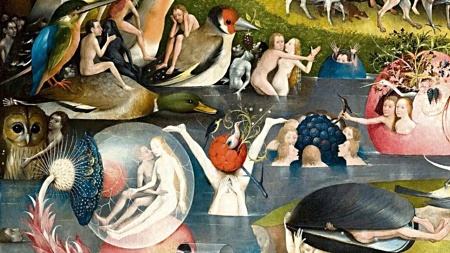

D.J. Opperman het gelukkig al in die bundel “Engel uit die klip” (1950) oor “De tuin der Lusten” geskryf en dit toeganklik gemaak vir Afrikaanse poësielesers, al het JEROEN BOSCH nooit so bekend geword soos “Draaikewers” en “Sproeireën” nie. Hy het die skildery as ’n onontkombaar bekoorlike nagmerrie beskryf. Vandag kan die detail van “De tuin der Lusten” op internet bestudeer word. Dan verstaan mens sommer baie beter Opperman se verwysings na “stekelige plante, voëls en mens” en “laat ons vlug uit die gebras / en skuil in mossel” en na “sweef in belle glas”. Hierdie aanhalings uit Opperman se gedig is almal bo-aan die artikel in ’n uitsnede van “Die tuin der Lusten” afgebeeld. Dis moeilik om ´n mens se oë daarvan los te skeur wanneer Bosch duiwelsadvokaat speel. Hy vra as kluisenaar en absolute eenling aandag vir die verval van morele waardes in sy tyd.

JEROEN BOSCH

Ydel is die wêreld, maar ydeler my gees,

wat om die dertig nagte in nagmerries

van stekelige plante, voëls en mens genees.

Uit ou en nuwe streke van die aarde kies

die duiwel al hoe lustiger vir my, vir jou,

vir die derduisende kostuum en mombakkies.

Dit trek stoete, kermis om die Kruis, wissel

van gedaante deur die eeue; maar die spel

bly steeds dieselfde in monnike, masjiene of dissel.

En ewig in die kringloop van die lus gevang

ry ons en kap die lieste van die hingste

om en om die kraaie op kaal vrouens in die dam.

Ag, Liefste! Kom dan, laat ons vlug uit die gebras

en skuil in mossel, horingpeul – en ver bokant

die kermis van die bose sweef in belle glas.

Want in my is die swaap, die visgelipte sot

wat elke toertjie van ’n towenaar befluit …

maar wonderwerke en Sy kruisiging bespot;

en, as ek God saam met Antonius aanroep,

is hy reeds daar wat van ’n nuwe geilte

roekeloos die eerste swaeltjies deur ’n tregter poep.

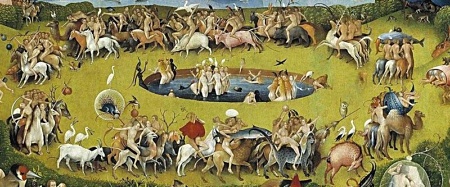

In strofe 4 fokus Opperman op die deel regs, skuins bokant die eerste gedetailleerde afbeelding. Dit word die Moredans genoem. Die dans vind plaas om die dam met die kaal vrouens en kraaie.

Bogenoemde twee afbeeldings is onderdele van die middelste paneel van “De tuin der Lusten”, wat eintlik ´n drieluik is. Die linkerkantste luik beeld die skepping van Adam en Eva uit. Die middelste luik beeld die aardse lewe as ´n tuin vol verleidings met eksotiese plante en diere, kaal mense, fabelagtige wesens en pienk fonteine uit. Dis hierdie luik wat die oorkoepelende naam “De tuin der Lusten” dra en waardeur Opperman verlei is om sy gedig JEROEN BOSCH te skryf. Die regterkantste luik beeld die hel uit. Die slotreël van die gedig verwys na ´n onderdeel uit die hel en word in die volgende afbeelding uitgebeeld.

Opperman se verwysing na Antonius roep die skildery “De verzoeking van de heilige Antonius” op. Dit is één van die werke wat ´n opskudding veroorsaak het. Die BRCP het ´n nuwe sisteem ontwikkel waarmee hulle die egtheid van al die Bosch-skilderye getoets het. Daarvolgens is “De verzoeking van de heilige Antonius” in Prado ´n vervalsing. Tegelykertyd het die BRCP het ook ´n egte skilderytjie uit 1500 – 1510 met dieselfde naam ontdek. Dit het in die Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, Missouri, gehang, maar is nou op bruikleen in Den Bosch. Die BRCP het onder andere skildertegnieke vergelyk. Jeroen Bosch se handtekening is sigbaar gemaak met behulp van infrafrooi fotografie. Die Spanjaarde is woedend. Hulle het geweier om die bruikleenkontrak met die Noord-Brabantse Museum volledig uit te voer en twee skilderye teruggehou: “De verzoeking van de heilige Antonius” en “De Keisnijding”. Die twee weergawes van “De verzoeking van de heilige Antonius” verskil nogal. Hieronder is ´n afbeelding van die ontdekking in Missouri: net 38,6 by 25,1 sentimeter groot.

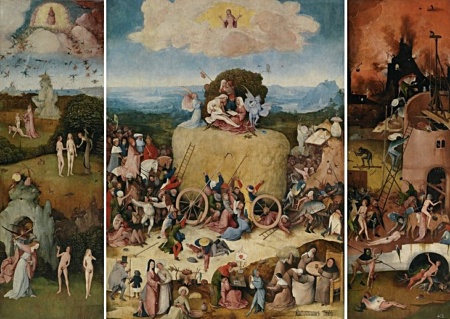

Gelukkig het Prado “De hooiwagen” (’n ander drieluik van Bosch) wél in bruikleen aan die Nederlandse museum toegestaan, maar ook hier was daar ´n slang in die gras. In plaas van om dit direk na die Noord-Brabantse Museum in Den Bosch toe te stuur, gaan maak “De hooiwagen” eers vir drie maande ´n draai in Museum Boijmans van Beuningen in Rotterdam! Dit het weer vir groot teleurstelling gesorg by die Noord-Brabants Museum, maar hulle hande was afgekap. Boijmans van Beuningen besit kosbaarder ruilware vir so ´n tipe transaksie as die BRCP.

Johan van Wyk se gedig oor “De hooiwagen” is in sy bundel “Deur die oog van die luiperd” (1976) gepubliseer. In hieronymus bosch se koringwa word die linkerkantste paneel in die eerste vyf strofes beskryf. Wat Van Wyk herkenbaar verwoord, is “die rebelse insekte swem in ’n boeg af” en ook “’n markvrou / tussen vrugtebome, God trou / adam en eva”.