Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Edith Wharton

(1862-1937)

Chartres

I

Immense, august, like some Titanic bloom,

The mighty choir unfolds its lithic core,

Petalled with panes of azure, gules and or,

Splendidly lambent in the Gothic gloom,

And stamened with keen flamelets that illume

The pale high-alter. On the prayer-worn floor,

By worshippers innumerous thronged of yore,

A few brown crones, familiars of the tomb,

The stranded driftwood of Faith’s ebbing sea—

For these alone the finials fret the skies,

The topmost bosses shake their blossoms free,

While from the triple portals, with grave eyes,

Tranquil, and fixed upon eternity,

The cloud of witnesses still testifies.

II

The crimson panes like blood-drops stigmatise

The western floor. The aisles are mute and cold.

A rigid fetich in her robe of gold,

The Virgin of the Pillar, with blank eyes,

Enthroned beneath her votive canopies,

Gathers a meagre remnant to her fold.

The rest is solitude; the church, grown old,

Stands stark and grey beneath the burning skies.

Well-nigh again its mighty framework grows

To be a part of nature’s self, withdrawn

From hot humanity’s impatient woes;

The floor is ridged like some rude mountain lawn,

And in the east one giant window shows

The roseate coldness of an Alp at dawn.

Edith Wharton poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive W-X, CLASSIC POETRY

Hans Hermans © photos: History of Britain

(Exmoor National Park, near Woody Bay 2014)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Hans Hermans Photos, History of Britain, Photography

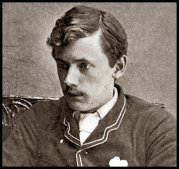

Ernest Dowson

(1867-1900)

Lost Love

I seek no more to bridge the gulf that lies

Betwixt our separate ways;

For vainly my heart prays,

Hope droops her head and dies;

I see the sad, tired answer in your eyes.

I did not heed, and yet the stars were clear;

Dreaming that love could mate

Lives grown so separate;—

But at the best, my dear,

I see we should not have been very near.

I knew the end before the end was nigh:

The stars have grown so plain;

Vainly I sigh, in vain

For things that come to some,

But unto you and me will never come.

Ernest Dowson poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Dowson, Ernest

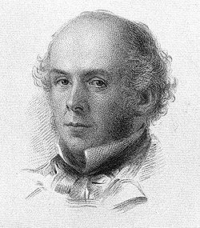

Arthur Cravan

Arthur Cravan

(1887-1918)

L’EXPOSITION DES INDÉPENDANTS PARIS 1914

Les peintres, — ils sont 2 ou 3 en France, — ont vraiment peu de représentations, et je me figure facilement leur état de mort, quand, durant de longs mois, ils ne paraissent plus en public. C’est une des raisons pourquoi je viens grossir le nombre des spectateurs qui se rendent au Salon des Indépendants ; bien que la meilleure soit encore le profond dégoût de la peinture que j’emporterai en sortant de l’exposition, et c’est un sentiment que le plus souvent on ne peut jamais assez développer. Mon Dieu, que les temps sont changés !

Aussi vrai que je suis rieur, je préfère le plus simplement du monde la photographie à l’art pictural et la lecture du Matin à celle de Racine. Pour vous, ceci demande une petite explication que je m’empresse de vous donner. Par exemple, il y a trois catégories de lecteurs de journaux : tout d’abord l’illettré, qui ne saurait prendre aucun goût à la lecture d’un chef-d’œuvre, puis l’homme supérieur, l’homme instruit, le monsieur distingué, sans imagination, qui lit à peine le journal parce qu’il a besoin de la fiction des autres, enfin l’homme ou la brute avec un tempérament qui sent son journal et qui se moque de la sensibilité des maîtres. Il y a de même trois sortes d’amoureux de photographies. Il faut absolument vous fourrez dans la tête que l’art est aux bourgeois et j’entends par bourgeois : un monsieur sans imagination. C’est entendu ; mais alors, me permettez-vous de demander pourquoi, méprisant la peinture, vous vous donnez la peine d’en faire la critique?

C’est bien simple : si j’écris c’est pour faire enrager mes confrères ; pour faire parler de moi et tenter de me faire un nom. Avec un nom on réussit avec les femmes et dans les affaires. Si j’avais la gloire de Paul Bourget je me montrerai tous les soirs en cache-sexe dans une revue de music-hall et je vous garantis que je ferai recette. Ma plume peut me donner encore l’avantage de passer pour un connaisseur, qui, aux yeux de la foule, est quelqu’un d’enviable, car il est à peu près certain qu’il n’y aura pas plus deux personnes intelligentes qui fréquenteront le Salon.

Avec des lecteurs aussi intellectuels que les miens, je suis obligé de m’expliquer une fois de plus et de dire que je ne trouve un être intelligent seulement lorsque son intelligence a un tempérament, étant donné qu’un homme vraiment intelligent ressemble à un million d’hommes vraiment intelligents. Pour moi donc un homme fin ou subtil n’est presque toujours qu’un idiot.

Le Salon, vu du dehors, me plaît, avec ses tentes, qui lui donnent un air de cirque monté par quelque Barnum ; mais quelles sales gueules d’artistes vont le remplir : y en aura, y en aura : des rapins aux longs cheveux, des littérateurs aux longs cheveux; des rapins aux cheveux courts, des littérateurs aux cheveux courts ; des rapins mal vêtus, des littérateurs mal vêtus ; des rapins bien habillés, des littérateurs bien habillé ; des rapins aux sales gueules, des littérateurs aux sales gueules ; des rapins aux chics gueules… il n’y en a pas… il n’y en a pas ; mais il y a des artistes, nom de Dieu ! Dans la rue on ne verra bientôt plus que des artistes et l’on aura toutes les peines du monde à y découvrir un homme. Ils sont partout : les cafés en sont pleins, de nouvelles académies de peintures ouvrent chaque jour. A ce propos je me suis toujours demandé comment un professeur de peinture, s’il n’enseigne pas la copie à un serrurier, ait pu, depuis que le monde existe, trouver un seul élève. On se moque des clients des chiromanciennes ou cartomanciennes et l’on n’a jamais d’ironie pour les naïfs qui fréquentent les académies de peinture. Peut-on apprendre à dessiner, peindre, avoir du talent ou du génie ? Et pourtant, on voit dans ces ateliers de grands dadais de trente et même quarante ans et, Dieu me pardonne ! des tutus de 50 ans, oui, doux Jésus ! de pauvres fofos de cinquante ans ! Il y a aussi de jeunes Américains d’un mètre quatre-vingt-dix, heureux dans leurs épaules, qui savent boxer et qui viennent des pays arrosés par le Mississipi, où nagent les nègres avec des mufles d’hippopotames ; des contrées où les belles filles aux fesses dures montent à cheval ; qui viennent de New-York plein de gratte-ciels, de New-York sur les bords de l’Hudson où dorment les torpilleurs chargés comme les nuages. Il y a également de fraîches Américaines, ô pauvres Gratteciella ! !

On pourra m’objecter que les peintres trouvent dans les académies la chaleur en hiver et un modèle. Le modèle pour un vrai peintre c’est la vie. De toute façon, vous voyez d’ici si le modèle professionnel est plus vivant que les plâtres que l’on copie à l’École des Beaux-Arts : mais les clients de l’académie Matisse se moquent des pompiers des Beaux-Arts ; pensez donc : ils font de la peinture avancée. Il est vrai qu’il en est parmi ceux-ci qui croient que l’art est supérieur à la nature. Oui chéri !

Je m’étonne qu’un escroc d’esprit n’ait pas eu l’idée d’ouvrir une académie de littérature.

Pénétrons dans l’exposition, comme dirait un critique bon enfant. (Moi, je suis une vache.)

999 toiles sur 1.000 figureraient avec honneur au Salon des Artistes Français, à la Nationale ou au Salon d’Automne. Cézanne lui-même, avec ses natures mortes, et Van Gogh, avec sa toile qui représente des livres feraient encore très bien au Salon d’Automne. On s’est tellement moqué des peintres qui se servent de pommade, de vaseline et de savon pour faire des tableaux, que je ne reviendrai pas sur ce sujet, et si je vais citer une quantité de noms, c’est uniquement par roublardise et le seul moyen de vendre mon numéro, car j’aurai beau dire que Tavernier, par exemple, est le dernier des fruits secs, et citer ce petit con de Zac au milieu d’une interminable liste de nullités, ils m’achèteront tous deux, avec les autres, pour le seul plaisir de voir leurs noms imprimés. Du reste, si j’étais cité, je ferai comme eux.

Il y en a-t-il de faux Roybet, de faux Chabat, de faux primitifs, de faux Cézanne, de faux Gauguin, de faux Maurice Denis et de faux Charles Guérin. Ces chers Maurice Denis et Charles Guérin ! Quel coup de pied dans le derrière je leur fouterai volontiers. Ah ! nom de Dieu de nom de Dieu ! Quel faux idéal que celui de Maurice Denis, il peint des femmes et des enfants nus dans la nature, ce qui ne se voit jamais de nos jours. Devant ses toiles, comme disait un de mes amis, Édouard Archinard, on dirait que les enfants s’élèvent tout seuls, que les ressemelages de souliers ne coûtent rien. Qu’on est loin des accidents de chemins de fer : Maurice Denis devrait peindre au ciel, car il ignore le smoking et le fromage des pieds. Non point que je trouve très audacieux de peindre un acrobate ou un chieur, puisque, au contraire, j’estime qu’une rose faite avec nouveauté est beaucoup plus démoniaque. Dans le même ordre d’idées, je sens le même mépris envers un pasticheur de Carolus Duran qu’envers un de Van Gogh. Le premier a plus de naïveté et le second plus de culture et de bonne volonté : deux choses bien piètres.

Ce que j’ai dit de Maurice Denis convient à peu près à Charles Guérin et je n’insiste pas.

Ce que l’on remarquera surtout au Salon, c’est la place qu’a pris l’intelligence chez les soi-disant artistes. Tout d’abord, je trouve que la première condition pour un artiste est de savoir nager. Je sens également que l’art à l’état mystérieux de la forme chez un lutteur a plutôt son siège dans le ventre que dans le cerveau, et c’est pourquoi je m’exaspère lorsque je suis devant une toile et que je vois, quand j’évoque l’homme, se dresser seulement une tête. Où sont les jambes, la rate et le foie ?

C’est pourquoi je ne puis avoir que du dégoût pour la peinture d’un Chagall ou Chacal, qui vous montrera un homme versant du pétrole dans le trou du cul d’une vache, quand la véritable folie elle-même ne peut me plaire parce qu’elle met uniquement en évidence un cerveau alors que le génie n’est qu’une manifestation extravagante du corps.

Henry Hayden. Si je parle d’abord de ce peintre, c’est que le chapeau de madame Cravan a servi à sa confection. Confection, en vérité, que ce tableau. Tout y est mal venu, sale, écrasé de cérébralité. Je préférerai rester deux minutes sous l’eau que devant ce tableau : j’étoufferai moins. Les valeurs y sont arrangées, pour faire bien, quand dans une œuvre sortie d’une vision les valeurs ne sont que les couleurs d’une boule lumineuse. Celui qui voit la boule n’a pas besoin de remanier ses valeurs qui resteront toujours fausses. Hayden n’a pas vu la boule, car il y a au moins dix tableaux dans sa toile.

Un bon conseil : prenez quelques pilules et purgez votre esprit ; baisez beaucoup ou encore entraînez-vous à outrance : lorsque vous aurez cinquante centimètres de tour de bras peut-être serez-vous enfin une brute, si vous êtes doué.

Loeb. Son envoi donne l’impression de travail et non de peinture.

Morgan Russell essaye de voiler son impuissance derrière les procédés du synchromisme. J’avais déjà vu de ses toiles conventionnelles, d’une saleté de couleurs repoussante à son exposition chez Bernheim Jeunes. Je ne lui découvre aucune qualité. Chagall a, malgré tout, une certaine naïveté et une certaine couleur. C’est peut-être un innocent, mais un trop petit innocent. Chamier, un rien. Frost, rien. Pec Krogh est un vieux roublard qui veut le faire au vieux naïf. Alexandre Exler est un de ces pauvres artistes qui feraient cent fois mieux d’exposer aux Artistes Français, car un Bouguereau cubiste est malgré tout un Bougereau. Laboureur ses toiles, bien qu’encore sales, ont quelque vie, surtout celle qui montre un café avec des joueurs de billard ; mais le plaisir qu’on a de la regarder n’est pas immense, parce qu’elle n’est pas assez différente. Boussingault, j’ai vu ça partout. Kesmarky, c’est moche, oui marquis ! Einhorn, Lucien Laforge, Szobotka, Valmier sont des cubistes sans talent. Suzanne Valadin connaît bien les petites recettes, mais simplifier ce n’est pas faire simple, vieille salope ! Tobeen. Ah, ah ! Hum… hum ! ! Mon vieux Tobeen (je ne vous connais pas, mais ça ne fait rien), si Machinchouette vous donne encore rendez-vous à la « Rotonde », collez-lui un lapin. Il y a quelque chose dans votre peinture (ça c’est gentil), mais on sent qu’elle doit encore pas mal de choses aux petites discussions sur l’esthétique dans les cafés. Tous vos amis sont de petits crétins (ça c’est vache, par exemple). Voulez-vous me ficher cette petite dignité en l’air ! Allez courir dans les champs, traverser les plaines à fond de train comme un cheval ; sautez à la corde et, quand vous aurez six ans, vous ne saurez plus rien et vous verrez des choses insensées. André Ritter envoie un cochonnerie noire. En voilà un qui est obscène sans s’en douter. Ermein, un autre abruti. Schmalzigang donne à penser que le futurisme (je ne sais pas si sa toile est précisément futuriste), aura le même défaut que l’école impressionniste : la sensibilité unique de l’œil. On dirait que c’est une mouche, et une mouche frivole qui voit la nature et non pas une mouche qui s’enivre de la merde, car ce qui est odeur ou son est toujours absent avec tout ce qui semble impossible de mettre en peinture et qui est justement tout.

D’avoir parlé aussi longuement de Schmalzigang ne veut pas dire que je trouve sa toile un chef-d’œuvre, loin de là. Mlle Hanna Koschinski, très Kochonski. Pauvre Russe ! Marval expose un tableau charmant. Je sais que beaucoup de gens préféreraient que l’on dise en parlant d’eux que leur toile est diabolique. Mais savez-vous toute la substance que contiennent les mots adorables ou charmants ? Je me ferai mieux comprendre en indiquant que je ne trouve pas charmantes les fleurs de la nationale Madeleine Lemaire. Flandrin a un certain talent. Évidemment que le génie ne souffle pas en tempête dans ses toiles, balayant les blés et les arbres. Sa peinture sent la règle générale et non sa règle personnelle, mais enfin nous voudrions bien voir les Gleize et Metzinger donner l’équivalent dans leurs tableaux cubistes. Marya Rubezac, un petit rien dans une de ses toiles. Kulbin fait du chiqué.

Hassenberg, comme c’est sale. Alice Bailly, il y a de la gaieté dans son envoi Le Patinage au Bois et c’est déjà beaucoup. Je m’attendais à quelque chose d’horrible, car Mlle Bailly n’a jamais été mariée. Arthur Cravan, s’il n’avait pas été dans une période de paresse eut envoyé une toile avec ce titre : Le Champion du Monde au Bordel. De la Fresnaye, j’avais déjà remarqué son envoi au Salon d’Automne, car sa toile était fraîche. Je suis prêts à donner cent francs à celui qui peut me montrer vingt toiles fraîches dans une exposition. Cette fois-ci cette prodigieuse qualité a disparu en grande partie. (Je suis obligé d’avertir mes lecteurs que je n’ai vu que deux toiles sur les trois qu’il doit envoyer, l’autre n’étant pas encore arrivée), J’ignore si la critique du juif Apollinaire — je n’ai aucun préjugé contre les juifs, préférant, la plupart du temps, un juif à un protestant — lui donna de l’incertitude, quand cet espèce de Catulle Mendès déclara dans une de ses critiques qu’il était le disciple de Delaunay. Se laissa-t-il prendre à pareille fourberie ?

Ses deux natures mortes ont un peu cette même sécheresse d’aspect qui se montre dans la typographie des couvertures des livres de M. Gide. Ne sachant absolument rien de M. de la Fresnaye, j’ignore quel milieu il fréquente, mais je suis persuadé qu’il est mauvais. Son nom me dit qu’il est noble et sa peinture qu’il est distingué. La distinction est bornée d’un côté par la voyoucratie et de l’autre par la noblesse. Elle est donc au milieu et, comme toutes les choses au milieu, elle est la médiocrité. Tout noble a du voyou en lui et tout voyou du noble parce qu’ils sont les deux extrêmes. La distinction étant enfermée dans des limites n’est jamais qu’elle-même et appartient aux talents. Il manque donc à M. de la Fresnaye le dernier jeu de la couleur et la liberté suprême. Cet artiste ne doit pas être un de ceux qui, ayant terminé un chef-d’œuvre, penseront : je n’ai pas fini de rire. Metzinger, un raté qui s’est raccroché au cubisme. Sa couleur a l’accent allemand. II me dégoûte. K. Malevitch, du chiqué. Alfred Hagint triste, triste. Peské, t’es moche ! Luce n’a aucun talent. Signac, je ne dis rien de lui parce qu’on a déjà tant écrit sur son œuvre. Qu’il sache seulement que je pense beaucoup de bien de lui. Deltombe, quel con ! Aurora Folquer, et ta sœur ? Puech la Rose rose : tais-toi méchante ! Marcoussis, de l’insincérité, mais l’on sent comme devant toutes les toiles cubistes qu’il devrait y avoir quelque chose, mais quoi ? La beauté, bougre d’idiot ! Robert Lotiron, peut-être. Gleizes n’est pas non plus le sauveur, car il faudrait un génie aux cubistes pour peindre sans truquages et sans procédés. Je ne crois pas que Gleizes ait même aucun talent. C’est très embêtant pour lui, mais c’est ainsi. On va croire peut-être que j’ai un parti-pris contre le cubisme. Aucunement : je préfère toutes les excentricités d’un esprit même banal aux œuvres plates d’un imbécile bourgeois. A. Kristians est un imitateur et non un disciple de Van Dongen.

A. Kistein, mon pauvre vieux, c’est pas ça du tout. Van Dongen, selon son habitude depuis quelques années, envoie ce qu’il a de plus mauvais au Salon. Van Dongen a fait des choses admirables. Il a la peinture dans la peau. Quand je cause avec lui et que je le regarde, je me figure toujours que ses cellules sont pleines de couleur, que sa barbe elle-même et ses cheveux charrient du vert, du jaune, du rouge ou du bleu dans leurs canaux. Mon amour me fera écrire plus tard tout un article sur lui, et c’est pourquoi j’en dis si peu de chose aujourd’hui.

De Segonzac, je n’ai pas vu son envoi. A en juger par ses dernières toiles, ce peintre, qui avait donné quelques promesses à ses débuts, ne fait plus que de petites saloperies. Kipling, je n’ai pas vu son envoi et j’ignore jusqu’à l’ortographe correct de son nom. Je me suis laissé dire qu’il avait du talent, mais je réserve mon opinion. Chacun comprendra qu’il m’est impossible de tout voir en une seule fois. Dans mon prochain numéro je ne manquerai pas d’attirer l’attention sur l’inconnu que j’aurai pu découvrir. Il est très difficile de se guider sous les tentes quand les toiles ne sont pas encore accrochées : on en retourne quelques-unes dans une salle et, comme on ne voit que des horreurs, on imagine, peut-être à tort, que le merle blanc n’est point là, alors qu’il y a mille chances contre une qu’il se trouve n’importe où et non dans la salle d’honneur, puisqu’à l’Exposition des Indépendants il y a une chose aussi dégoûtante qu’une salle d’honneur. Szaman Mondszain, il paraît que je me suis saoulé en compagnie de cet artiste ; mais je ne m’en souviens plus — on va dire que j’étais ivre-mort. — Toujours est-il que ce compagnon oublié a prié ma femme de parler de lui et, comme il lui a fait quelques courbettes, je m’empresse de m’exécuter. Je n’ai pas découvert sa toile : il a de la chance ! Robert Delaunay, je suis tenu à prendre quelques précautions avant de parler de lui. Nous nous sommes battus et je tiens à ce que ni lui ni personne ne pense que ma critique en ait été influencé. Je ne m’occupe ni des haines ni des amitiés personnelles. C’est une grande vertu qui trouve à l’heure actuelle, où la critique sincère est pour ainsi dire inexistante, un excellent placement et peut être d’un fort bon rapport. Si je parle beaucoup de l’homme et que certains détails vous choquent, je vous assure que cette façon de faire n’est que toute naturelle, puisque c’est ma manière de voir les choses.

Une fois de plus, je dois avouer que je n’ai pas vu sa peinture. Il paraît que Delaunay a l’habitude d’envoyer ses toiles le dernier jour pour emmerder la critique, ce en quoi je lui donne parfaitement raison. Celui qui écrit sérieusement une ligne sur la peinture est ce que je pense.

Je crois que ce peintre a mal tourné. Je dis « mal tourné », bien que je sente que ce soit une prouesse irréalisable. M. Delaunay, qui a une gueule de porc enflammé ou de cocher de grande maison pouvait ambitionner avec une pareille hure de faire une peinture de brute. L’extérieur était prometteur, l’intérieur valait peu de chose. J’exagère probablement en disant que l’apparence phénoménale de Delaunay était quelque chose d’admirable. Au physique c’est un fromage mou : il court avec peine et Robert a quelque peine à lancer un caillou à trente mètres. Vous conviendrez que ce n’est pas fameux. Malgré tout, comme je le disais plus haut, il avait sa gueule pour lui : cette figure d’une vulgarité tellement provocante qu’elle donne l’impression d’un pet rouge. Par malheur pour lui — vous comprenez bien qu’il me soit indifférent que tel ou tel ait du talent ou n’en ait pas — il épousa une Russe, oui. Vierge Marie ! une Russe, mais une Russe qu’il n’ose pas tromper. Pour ma part, je préférerai faire de mauvaises manières avec un professeur de philosophie au Collège de France — Monsieur Bergson, par exemple, — que de coucher avec la plupart des femmes russes. Je ne prétends pas que je ne forniquerai pas une fois Madame Delaunay, puisque, avec la grande majorité des hommes, je suis né collectionneur et que, par conséquent, j’aurai une satisfaction cruelle à mettre à mal une maîtresse d’école enfantine, d’autant plus, qu’au moment où je la briserai, j’aurai l’impression de casser un verre de lunettes.

Avant de connaître sa femme, Robert était un âne ; il en avait peut-être toutes les qualités : il était braîlleur, il aimait les chardons, à se rouler dans l’herbe et il regardait avec de grands yeux stupéfaits le monde qui est si beau sans songer s’il était moderne ou ancien, prenant un poteau télégraphique pour un végétal et croyant qu’une fleur était une invention. Depuis qu’il est avec sa Russe, il sait que la Tour Eiffel, le téléphone, les automobiles, un aéroplane sont des choses modernes. Eh bien ça lui a fait beaucoup de tort à ce gros bêta d’en savoir aussi long, non pas que les connaissances puissent nuire à un artiste, mais un âne est un âne et avoir du tempérament c’est s’imiter. Je vois donc un manque de tempérament chez Delaunay. Quand on a la chance d’être une brute, il faut savoir le rester. Tout le monde comprendra que je préfère un gros Saint-Bernhard obtus à Mademoiselle Faufreluche qui peut exécuter les pas de la gavotte et, de toute façon, un jaune à un blanc, un nègre à un jaune et un nègre boxeur à un nègre étudiant. Madame Delaunay qui est une cé-ré-brâââle, bien qu’elle ait encore moins de savoir que moi, ce qui n’est pas peu dire, lui a bourré la tête de principes pas mêmes extravagants, mais simplement excentriques. Robert a pris une leçon de géométrie, une de physique et une autre d’astronomie et il a regardé la lune au télescope, quand il a été un faux savant. Son futurisme — je ne dis pas ça pour le vexer, car je crois que presque toute la peinture à venir dérivera du futurisme auquel il manque également un génie, les Cara ou Boccioni étant des nullités — a de grandes qualités de toupet. — comme sa gueule — bien que sa peinture ait des défauts de la hâte de vouloir être coûte que coûte le premier.

J’oubliais de vous dire que dans la vie il s’efforce d’imiter la petite existence du douanier Rousseau.

J’ignore s’il viendra à cette exposition affublé d’un pardessus rouge comme au Salon d’Automne, ce qui n’est pas d’un vivant, mais d’un mort, étant donné qu’aujourd’hui tous les hommes sont noirs et que la mode est l’expression de la vie.

Marie Laurencin (je n’ai pas vu son envoi). En voilà une qui aurait besoin qu’on lui relève les jupes et qu’on lui mette une grosse… quelque part pour lui apprendre que l’art n’est pas une petite pose devant le miroir. Oh ! chochotte ! (ta gueule !) La peinture c’est marcher, courir, boire, manger, dormir et faire ses besoins. Vous aurez beau dire que je suis un dégueulasse, c’est tout ça.

C’est outrager l’Art que de dire que pour être un artiste il faut commencer par boire et manger. Je ne suis pas une réaliste et l’art est heureusement en dehors de toutes ces contingences (et ta sœur ?)

L’Art, avec un grand A, est au contraire, chère Mademoiselle, littérairement parlant, une fleur (ô, ma gosse !) qui ne s’épanouit qu’au milieu des contingences, et il n’est point douteux qu’un étron soit aussi nécessaire à la formation d’un chef d’œuvre que le loquet de votre porte, ou, pour frapper votre imagination d’une manière saisissante, ne soit pas aussi nécessaire, dis-je, que la rosé délicieusement alangourée qui expire adorablement en parfum ses pétales languissamment rosées sur le paros virginalement apâli de votre délicatement tendre et artiste cheminé (poil aux nénés !)

arthur cravan.

P. S. — Ne pouvant pas me défendre dans la presse contre les critiques qui ont hypocritement insinué que je m’apparentais soit à Apollinaire ou à Marinetti, je viens les avertir que, s’ils recommencent, je leur torderai les parties sexuelles.

L’un d’eux disait à ma femme : « Que voulez-vous, Monsieur Cravan ne vient pas assez parmi nous. ». Qu’on le sache une fois pour toutes : Je ne veux pas me civiliser.

D’autre part, je tiens à informer mes lecteurs que je recevrai avec plaisir tout ce qu’ils trouveront bon de m’envoyer : pots de confiture, mandats, liqueurs, timbres-postes de tous les pays, etc., etc. En tout cas chaque cadeau me fera rire.

A. C.

Arthur Cravan: L’exposition des indépendants

Revue Maintenant n°4 (mars-avril 1914)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Cravan, Arthur, Dada

Jonathan Swift

(1667–1745)

Market Women’s Cries

APPLES

Come buy my fine wares,

Plums, apples and pears.

A hundred a penny,

In conscience too many:

Come, will you have any?

My children are seven,

I wish them in Heaven;

My husband ’s a sot,

With his pipe and his pot,

Not a farthen will gain them,

And I must maintain them.

ONIONS

Come, follow me by the smell,

Here are delicate onions to sell;

I promise to use you well.

They make the blood warmer,

You’ll feed like a farmer;

For this is every cook’s opinion,

No savoury dish without an onion;

But, lest your kissing should be spoiled,

Your onions must be thoroughly boiled:

Or else you may spare

Your mistress a share,

The secret will never be known:

She cannot discover

The breath of her lover,

But think it as sweet as her own.

HERRINGS

Be not sparing,

Leave off swearing.

Buy my herring

Fresh from Malahide,

Better never was tried.

Come, eat them with pure fresh butter and mustard,

Their bellies are soft, and as white as a custard.

Come, sixpence a dozen, to get me some bread,

Or, like my own herrings, I soon shall be dead.

Jonathan Swift poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Swift, Jonathan

Arthur Hugh Clough

(1819-1861)

Say not the struggle

Say not the struggle naught availeth,

The labour and the wounds are vain,

The enemy faints not, nor faileth,

And as things have been, things remain.

If hopes were dupes, fears may be liars;

It may be, in yon smoke concealed,

Your comrades chase e’en now the fliers,

And, but for you, possess the field.

For while the tired waves, vainly breaking,

Seem here no painful inch to gain,

Far back through creeks and inlets making

Comes silent, flooding in, the main.

And not by eastern windows only,

When daylight comes, comes in the light,

In front the sun climbs slow, how slowly,

But westward, look, the land is bright.

Arthur Hugh Clough poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, CLASSIC POETRY

Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf

(1882-1941)

4. An Unwritten Novel

(from: Monday or Tuesday)

Such an expression of unhappiness was enough by itself to make one’s eyes slide above the paper’s edge to the poor woman’s face — insignificant without that look, almost a symbol of human destiny with it. Life’s what you see in people’s eyes; life’s what they learn, and, having learnt it, never, though they seek to hide it, cease to be aware of — what?

That life’s like that, it seems. Five faces opposite — five mature faces — and the knowledge in each face. Strange, though, how people want to conceal it! Marks of reticence are on all those faces: lips shut, eyes shaded, each one of the five doing something to hide or stultify his knowledge. One smokes; another reads; a third checks entries in a pocket book; a fourth stares at the map of the line framed opposite; and the fifth — the terrible thing about the fifth is that she does nothing at all. She looks at life. Ah, but my poor, unfortunate woman, do play the game — do, for all our sakes, conceal it!

As if she heard me, she looked up, shifted slightly in her seat and sighed. She seemed to apologise and at the same time to say to me, “If only you knew!” Then she looked at life again. “But I do know,” I answered silently, glancing at the Times for manners’ sake. “I know the whole business. ‘Peace between Germany and the Allied Powers was yesterday officially ushered in at Paris — Signor Nitti, the Italian Prime Minister — a passenger train at Doncaster was in collision with a goods train. ..’ We all know — the Times knows — but we pretend we don’t.” My eyes had once more crept over the paper’s rim She shuddered, twitched her arm queerly to the middle of her back and shook her head. Again I dipped into my great reservoir of life. “Take what you like,” I continued, “births, deaths, marriages, Court Circular, the habits of birds, Leonardo da Vinci, the Sandhills murder, high wages and the cost of living — oh, take what you like,” I repeated, “it’s all in the Times!” Again with infinite weariness she moved her head from side to side until, like a top exhausted with spinning, it settled on her neck.

The Times was no protection against such sorrow as hers. But other human beings forbade intercourse. The best thing to do against life was to fold the paper so that it made a perfect square, crisp, thick, impervious even to life. This done, I glanced up quickly, armed with a shield of my own. She pierced through my shield; she gazed into my eyes as if searching any sediment of courage at the depths of them and damping it to clay. Her twitch alone denied all hope, discounted all illusion.

So we rattled through Surrey and across the border into Sussex. But with my eyes upon life I did not see that the other travellers had left, one by one, till, save for the man who read, we were alone together. Here was Three Bridges station. We drew slowly down the platform and stopped. Was he going to leave us? I prayed both ways — I prayed last that he might stay. At that instant he roused himself, crumpled his paper contemptuously, like a thing done with, burst open the door, and left us alone.

The unhappy woman, leaning a little forward, palely and colourlessly addressed me — talked of stations and holidays, of brothers at Eastbourne, and the time of year, which was, I forget now, early or late. But at last looking from the window and seeing, I knew, only life, she breathed, “Staying away — that’s the drawback of it —” Ah, now we approached the catastrophe, “My sister-in-law”— the bitterness of her tone was like lemon on cold steel, and speaking, not to me, but to herself, she muttered, “nonsense, she would say — that’s what they all say,” and while she spoke she fidgeted as though the skin on her back were as a plucked fowl’s in a poulterer’s shop-window.

“Oh, that cow!” she broke off nervously, as though the great wooden cow in the meadow had shocked her and saved her from some indiscretion. Then she shuddered, and then she made the awkward angular movement that I had seen before, as if, after the spasm, some spot between the shoulders burnt or itched. Then again she looked the most unhappy woman in the world, and I once more reproached her, though not with the same conviction, for if there were a reason, and if I knew the reason, the stigma was removed from life.

“Sisters-in-law,” I said —

Her lips pursed as if to spit venom at the word; pursed they remained. All she did was to take her glove and rub hard at a spot on the window-pane. She rubbed as if she would rub something out for ever — some stain, some indelible contamination. Indeed, the spot remained for all her rubbing, and back she sank with the shudder and the clutch of the arm I had come to expect. Something impelled me to take my glove and rub my window. There, too, was a little speck on the glass. For all my rubbing it remained. And then the spasm went through me I crooked my arm and plucked at the middle of my back. My skin, too, felt like the damp chicken’s skin in the poulterer’s shop-window; one spot between the shoulders itched and irritated, felt clammy, felt raw. Could I reach it? Surreptitiously I tried. She saw me. A smile of infinite irony, infinite sorrow, flitted and faded from her face. But she had communicated, shared her secret, passed her poison she would speak no more. Leaning back in my corner, shielding my eyes from her eyes, seeing only the slopes and hollows, greys and purples, of the winter’s landscape, I read her message, deciphered her secret, reading it beneath her gaze.

Hilda’s the sister-in-law. Hilda? Hilda? Hilda Marsh — Hilda the blooming, the full bosomed, the matronly. Hilda stands at the door as the cab draws up, holding a coin. “Poor Minnie, more of a grasshopper than ever — old cloak she had last year. Well, well, with too children these days one can’t do more. No, Minnie, I’ve got it; here you are, cabby — none of your ways with me. Come in, Minnie. Oh, I could carry you, let alone your basket!” So they go into the dining-room. “Aunt Minnie, children.”

Slowly the knives and forks sink from the upright. Down they get (Bob and Barbara), hold out hands stiffly; back again to their chairs, staring between the resumed mouthfuls. [But this we’ll skip; ornaments, curtains, trefoil china plate, yellow oblongs of cheese, white squares of biscuit — skip — oh, but wait! Half-way through luncheon one of those shivers; Bob stares at her, spoon in mouth. “Get on with your pudding, Bob;” but Hilda disapproves. “Why should she twitch?” Skip, skip, till we reach the landing on the upper floor; stairs brass-bound; linoleum worn; oh, yes! little bedroom looking out over the roofs of Eastbourne — zigzagging roofs like the spines of caterpillars, this way, that way, striped red and yellow, with blue-black slating]. Now, Minnie, the door’s shut; Hilda heavily descends to the basement; you unstrap the straps of your basket, lay on the bed a meagre nightgown, stand side by side furred felt slippers. The looking-glass — no, you avoid the looking-glass. Some methodical disposition of hat-pins. Perhaps the shell box has something in it? You shake it; it’s the pearl stud there was last year — that’s all. And then the sniff, the sigh, the sitting by the window. Three o’clock on a December afternoon; the rain drizzling; one light low in the skylight of a drapery emporium; another high in a servant’s bedroom — this one goes out. That gives her nothing to look at. A moment’s blankness — then, what are you thinking? (Let me peep across at her opposite; she’s asleep or pretending it; so what would she think about sitting at the window at three o’clock in the afternoon? Health, money, bills, her God?) Yes, sitting on the very edge of the chair looking over the roofs of Eastbourne, Minnie Marsh prays to Gods. That’s all very well; and she may rub the pane too, as though to see God better; but what God does she see? Who’s the God of Minnie Marsh, the God of the back streets of Eastbourne, the God of three o’clock in the afternoon? I, too, see roofs, I see sky; but, oh, dear — this seeing of Gods! More like President Kruger than Prince Albert — that’s the best I can do for him; and I see him on a chair, in a black frock-coat, not so very high up either; I can manage a cloud or two for him to sit on; and then his hand trailing in the cloud holds a rod, a truncheon is it? — black, thick, thorned — a brutal old bully — Minnie’s God! Did he send the itch and the patch and the twitch? Is that why she prays? What she rubs on the window is the stain of sin. Oh, she committed some crime!

I have my choice of crimes. The woods flit and fly — in summer there are bluebells; in the opening there, when Spring comes, primroses. A parting, was it, twenty years ago? Vows broken? Not Minnie’s! . . . She was faithful. How she nursed her mother! All her savings on the tombstone — wreaths under glass — daffodils in jars. But I’m off the track. A crime . . . They would say she kept her sorrow, suppressed her secret — her sex, they’d say — the scientific people. But what flummery to saddle her with sex! No — more like this. Passing down the streets of Croydon twenty years ago, the violet loops of ribbon in the draper’s window spangled in the electric light catch her eye. She lingers — past six. Still by running she can reach home. She pushes through the glass swing door. It’s sale-time. Shallow trays brim with ribbons. She pauses, pulls this, fingers that with the raised roses on it — no need to choose, no need to buy, and each tray with its surprises. “We don’t shut till seven,” and then it is seven. She runs, she rushes, home she reaches, but too late. Neighbours — the doctor — baby brother — the kettle — scalded — hospital — dead — or only the shock of it, the blame? Ah, but the detail matters nothing! It’s what she carries with her; the spot, the crime, the thing to expiate, always there between her shoulders.

“Yes,” she seems to nod to me, “it’s the thing I did.”

Whether you did, or what you did, I don’t mind; it’s not the thing I want. The draper’s window looped with violet — that’ll do; a little cheap perhaps, a little commonplace — since one has a choice of crimes, but then so many (let me peep across again — still sleeping, or pretending sleep! white, worn, the mouth closed — a touch of obstinacy, more than one would think — no hint of sex)— so many crimes aren’t your crime; your crime was cheap; only the retribution solemn; for now the church door opens, the hard wooden pew receives her; on the brown tiles she kneels; every day, winter, summer, dusk, dawn (here she’s at it) prays. All her sins fall, fall, for ever fall. The spot receives them. It’s raised, it’s red, it’s burning. Next she twitches. Small boys point. “Bob at lunch to-day”— But elderly women are the worst.

Indeed now you can’t sit praying any longer. Kruger’s sunk beneath the clouds — washed over as with a painter’s brush of liquid grey, to which he adds a tinge of black — even the tip of the truncheon gone now. That’s what always happens! Just as you’ve seen him, felt him, someone interrupts. It’s Hilda now.

How you hate her! She’ll even lock the bathroom door overnight, too, though it’s only cold water you want, and sometimes when the night’s been bad it seems as if washing helped. And John at breakfast — the children — meals are worst, and sometimes there are friends — ferns don’t altogether hide ‘em — they guess, too; so out you go along the front, where the waves are grey, and the papers blow, and the glass shelters green and draughty, and the chairs cost tuppence — too much — for there must be preachers along the sands. Ah, that’s a nigger — that’s a funny man — that’s a man with parakeets — poor little creatures! Is there no one here who thinks of God? — just up there, over the pier, with his rod — but no — there’s nothing but grey in the sky or if it’s blue the white clouds hide him, and the music — it’s military music — and what they are fishing for? Do they catch them? How the children stare! Well, then home a back way —“Home a back way!” The words have meaning; might have been spoken by the old man with whiskers — no, no, he didn’t really speak; but everything has meaning — placards leaning against doorways — names above shop-windows — red fruit in baskets — women’s heads in the hairdresser’s — all say “Minnie Marsh!” But here’s a jerk. “Eggs are cheaper!” That’s what always happens! I was heading her over the waterfall, straight for madness, when, like a flock of dream sheep, she turns t’other way and runs between my fingers. Eggs are cheaper. Tethered to the shores of the world, none of the crimes, sorrows, rhapsodies, or insanities for poor Minnie Marsh; never late for luncheon; never caught in a storm without a mackintosh; never utterly unconscious of the cheapness of eggs. So she reaches home — scrapes her boots.

Have I read you right? But the human face — the human face at the top of the fullest sheet of print holds more, withholds more. Now, eyes open, she looks out; and in the human eye — how d’you define it? — there’s a break — a division — so that when you’ve grasped the stem the butterfly’s off — the moth that hangs in the evening over the yellow flower — move, raise your hand, off, high, away. I won’t raise my hand. Hang still, then, quiver, life, soul, spirit, whatever you are of Minnie Marsh — I, too, on my flower — the hawk over the down — alone, or what were the worth of life? To rise; hang still in the evening, in the midday; hang still over the down. The flicker of a hand — off, up! then poised again. Alone, unseen; seeing all so still down there, all so lovely. None seeing, none caring. The eyes of others our prisons; their thoughts our cages. Air above, air below. And the moon and immortality . . . Oh, but I drop to the turf! Are you down too, you in the corner, what’s your name — woman — Minnie Marsh; some such name as that? There she is, tight to her blossom; opening her hand-bag, from which she takes a hollow shell — an egg — who was saying that eggs were cheaper? You or I? Oh, it was you who said it on the way home, you remember, when the old gentleman, suddenly opening his umbrella — or sneezing was it? Anyhow, Kruger went, and you came “home a back way,” and scraped your boots. Yes. And now you lay across your knees a pocket-handkerchief into which drop little angular fragments of eggshell — fragments of a map — a puzzle. I wish I could piece them together! If you would only sit still. She’s moved her knees — the map’s in bits again. Down the slopes of the Andes the white blocks of marble go bounding and hurtling, crushing to death a whole troop of Spanish muleteers, with their convoy — Drake’s booty, gold and silver. But to return —

To what, to where? She opened the door, and, putting her umbrella in the stand — that goes without saying; so, too, the whiff of beef from the basement; dot, dot, dot. But what I cannot thus eliminate, what I must, head down, eyes shut, with the courage of a battalion and the blindness of a bull, charge and disperse are, indubitably, the figures behind the ferns, commercial travellers. There I’ve hidden them all this time in the hope that somehow they’d disappear, or better still emerge, as indeed they must, if the story’s to go on gathering richness and rotundity, destiny and tragedy, as stories should, rolling along with it two, if not three, commercial travellers and a whole grove of aspidistra. “The fronds of the aspidistra only partly concealed the commercial traveller —” Rhododendrons would conceal him utterly, and into the bargain give me my fling of red and white, for which I starve and strive; but rhododendrons in Eastbourne — in December — on the Marshes’ table — no, no, I dare not; it’s all a matter of crusts and cruets, frills and ferns. Perhaps there’ll be a moment later by the sea. Moreover, I feel, pleasantly pricking through the green fretwork and over the glacis of cut glass, a desire to peer and peep at the man opposite — one’s as much as I can manage. James Moggridge is it, whom the Marshes call Jimmy? [Minnie, you must promise not to twitch till I’ve got this straight]. James Moggridge travels in — shall we say buttons? — but the time’s not come for bringing them in — the big and the little on the long cards, some peacock-eyed, others dull gold; cairngorms some, and others coral sprays — but I say the time’s not come. He travels, and on Thursdays, his Eastbourne day, takes his meals with the Marshes. His red face, his little steady eyes — by no means. altogether commonplace — his enormous appetite (that’s safe; he won’t look at Minnie till the bread’s swamped the gravy dry), napkin tucked diamond-wise — but this is primitive, and, whatever it may do the reader, don’t take me in. Let’s dodge to the Moggridge household, set that in motion. Well, the family boots are mended on Sundays by James himself. He reads Truth. But his passion? Roses — and his wife a retired hospital nurse — interesting — for God’s sake let me have one woman with a name I like! But no; she’s of the unborn children of the mind, illicit, none the less loved, like my rhododendrons. How many die in every novel that’s written — the best, the dearest, while Moggridge lives. It’s life’s fault. Here’s Minnie eating her egg at the moment opposite and at t’other end of the line — are we past Lewes? — there must be Jimmy — or what’s her twitch for?

There must be Moggridge — life’s fault. Life imposes her laws; life blocks the way; life’s behind the fern; life’s the tyrant; oh, but not the bully! No, for I assure you I come willingly; I come wooed by Heaven knows what compulsion across ferns and cruets, table splashed and bottles smeared. I come irresistibly to lodge myself somewhere on the firm flesh, in the robust spine, wherever I can penetrate or find foothold on the person, in the soul, of Moggridge the man. The enormous stability of the fabric; the spine tough as whalebone, straight as oaktree; the ribs radiating branches; the flesh taut tarpaulin; the red hollows; the suck and regurgitation of the heart; while from above meat falls in brown cubes and beer gushes to be churned to blood again — and so we reach the eyes. Behind the aspidistra they see something: black, white, dismal; now the plate again; behind the aspidistra they see elderly woman; “Marsh’s sister, Hilda’s more my sort;” the tablecloth now. “Marsh would know what’s wrong with Morrises . . . ” talk that over; cheese has come; the plate again; turn it round — the enormous fingers; now the woman opposite. “Marsh’s sister — not a bit like Marsh; wretched, elderly female . . . You should feed your hens . . . God’s truth, what’s set her twitching? Not what I said? Dear, dear, dear! these elderly women. Dear, dear!”

[Yes, Minnie; I know you’ve twitched, but one moment — James Moggridge].

“Dear, dear, dear!” How beautiful the sound is! like the knock of a mallet on seasoned timber, like the throb of the heart of an ancient whaler when the seas press thick and the green is clouded. “Dear, dear!” what a passing bell for the souls of the fretful to soothe them and solace them, lap them in linen, saying, “So long. Good luck to you!” and then, “What’s your pleasure?” for though Moggridge would pluck his rose for her, that’s done, that’s over. Now what’s the next thing? “Madam, you’ll miss your train,” for they don’t linger.

That’s the man’s way; that’s the sound that reverberates; that’s St. Paul’s and the motor-omnibuses. But we’re brushing the crumbs off. Oh, Moggridge, you won’t stay? You must be off? Are you driving through Eastbourne this afternoon in one of those little carriages? Are you man who’s walled up in green cardboard boxes, and sometimes has the blinds down, and sometimes sits so solemn staring like a sphinx, and always there’s a look of the sepulchral, something of the undertaker, the coffin, and the dusk about horse and driver? Do tell me — but the doors slammed. We shall never meet again. Moggridge, farewell!

Yes, yes, I’m coming. Right up to the top of the house. One moment I’ll linger. How the mud goes round in the mind — what a swirl these monsters leave, the waters rocking, the weeds waving and green here, black there, striking to the sand, till by degrees the atoms reassemble, the deposit sifts itself, and again through the eyes one sees clear and still, and there comes to the lips some prayer for the departed, some obsequy for the souls of those one nods to, the people one never meets again.

James Moggridge is dead now, gone for ever. Well, Minnie —“I can face it no longer.” If she said that —(Let me look at her. She is brushing the eggshell into deep declivities). She said it certainly, leaning against the wall of the bedroom, and plucking at the little balls which edge the claret-coloured curtain. But when the self speaks to the self, who is speaking? — the entombed soul, the spirit driven in, in, in to the central catacomb; the self that took the veil and left the world — a coward perhaps, yet somehow beautiful, as it flits with its lantern restlessly up and down the dark corridors. “I can bear it no longer,” her spirit says. “That man at lunch — Hilda — the children.” Oh, heavens, her sob! It’s the spirit wailing its destiny, the spirit driven hither, thither, lodging on the diminishing carpets — meagre footholds — shrunken shreds of all the vanishing universe — love, life, faith, husband, children, I know not what splendours and pageantries glimpsed in girlhood. “Not for me — not for me.”

But then — the muffins, the bald elderly dog? Bead mats I should fancy and the consolation of underlinen. If Minnie Marsh were run over and taken to hospital, nurses and doctors themselves would exclaim . . . There’s the vista and the vision — there’s the distance — the blue blot at the end of the avenue, while, after all, the tea is rich, the muffin hot, and the dog —“Benny, to your basket, sir, and see what mother’s brought you!” So, taking the glove with the worn thumb, defying once more the encroaching demon of what’s called going in holes, you renew the fortifications, threading the grey wool, running it in and out.

Running it in and out, across and over, spinning a web through which God himself — hush, don’t think of God! How firm the stitches are! You must be proud of your darning. Let nothing disturb her. Let the light fall gently, and the clouds show an inner vest of the first green leaf. Let the sparrow perch on the twig and shake the raindrop hanging to the twig’s elbow.. . Why look up? Was it a sound, a thought? Oh, heavens! Back again to the thing you did, the plate glass with the violet loops? But Hilda will come. Ignominies, humiliations, oh! Close the breach.

Having mended her glove, Minnie Marsh lays it in the drawer. She shuts the drawer with decision. I catch sight of her face in the glass. Lips are pursed. Chin held high. Next she laces her shoes. Then she touches her throat. What’s your brooch? Mistletoe or merry-thought? And what is happening? Unless I’m much mistaken, the pulse’s quickened, the moment’s coming, the threads are racing, Niagara’s ahead. Here’s the crisis! Heaven be with you! Down she goes. Courage, courage! Face it, be it! For God’s sake don’t wait on the mat now! There’s the door! I’m on your side. Speak! Confront her, confound her soul!

“Oh, I beg your pardon! Yes, this is Eastbourne. I’ll reach it down for you. Let me try the handle.” [But, Minnie, though we keep up pretences, I’ve read you right — I’m with you now].

“That’s all your luggage?”

“Much obliged, I’m sure.”

(But why do you look about you? Hilda don’t come to the station, nor John; and Moggridge is driving at the far side of Eastbourne).

“I’ll wait by my bag, ma’am, that’s safest. He said he’d meet me . . . Oh, there he is! That’s my son.”

So they walk off together.

Well, but I’m confounded . . . Surely, Minnie, you know better! A strange young man . . . Stop! I’ll tell him — Minnie! — Miss Marsh! — I don’t know though. There’s something queer in her cloak as it blows. Oh, but it’s untrue, it’s indecent . . . Look how he bends as they reach the gateway. She finds her ticket. What’s the joke? Off they go, down the road, side by side . . . Well, my world’s done for! What do I stand on? What do I know? That’s not Minnie. There never was Moggridge. Who am I? Life’s bare as bone.

And yet the last look of them — he stepping from the kerb and she following him round the edge of the big building brims me with wonder — floods me anew. Mysterious figures! Mother and son. Who are you? Why do you walk down the street? Where to-night will you sleep, and then, to-morrow? Oh, how it whirls and surges — floats me afresh! I start after them. People drive this way and that. The white light splutters and pours. Plate-glass windows. Carnations; chrysanthemums. Ivy in dark gardens. Milk carts at the door. Wherever I go, mysterious figures, I see you, turning the corner, mothers and sons; you, you, you. I hasten, I follow. This, I fancy, must be the sea. Grey is the landscape; dim as ashes; the water murmurs and moves. If I fall on my knees, if I go through the ritual, the ancient antics, it’s you, unknown figures, you I adore; if I open my arms, it’s you I embrace, you I draw to me — adorable world!

Monday or Tuesday, by Virginia Woolf

4. An Unwritten Novel

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Monday or Tuesday, Archive W-X, Woolf, Virginia

Anna de Noailles

(1876-1933)

Il n’est pas un instant

Il n’est pas un instant où près de toi couchée

Dans la tombe ouverte d’un lit,

Je n’évoque le jour où ton âme arrachée

Livrera ton corps à l’oubli. […]

Quand ma main sur ton coeur pieusement écoute

S’apaiser le feu du combat,

Et que ton sang reprend paisiblement sa route,

Et que tu respires plus bas,

Quand, lassés de l’immense et mouvante folie

Qui rend les esprits dévorants,

Nous gisons, rapprochés par la langueur qui lie

Le veilleur las et le mourant,

Je songe qu’il serait juste, propice et tendre

D’expirer dans ce calme instant

Où, soi-même, on ne peut rien sentir, rien entendre

Que la paix de son coeur content.

Ainsi l’on nous mettrait ensemble dans la terre,

Où, seule, j’eus si peur d’aller ;

La tombe me serait un moins sombre mystère

Que vivre seule et t’appeler.

Et je me réjouirais d’être un repas funèbre

Et d’héberger la mort qui se nourrit de nous,

Si je sentais encor, dans ce lit des ténèbres,

L’emmêlement de nos genoux…

Anna de Noailles poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive M-N, Noailles, Anna de

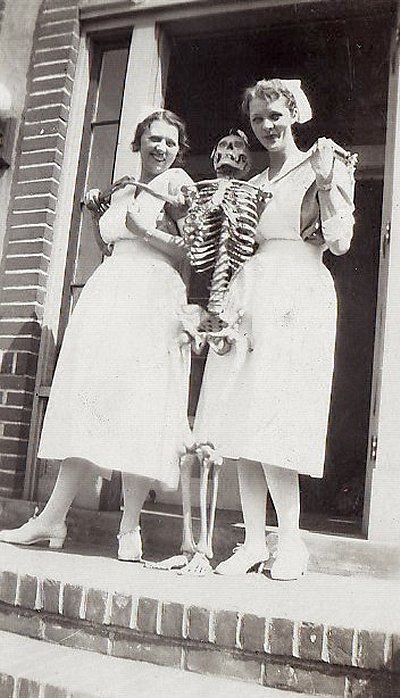

Lentedansje

Op een prachtige voorjaarsochtend na een strenge winter die ver achter ons ligt, ging in een sanatorium te D. de deur open van de afdeling waar TBC-patiënten hun dagen sleten. Het eerste wat men zag waren de bleke botjes van een hand die naar buiten werd gestoken en begon te zwaaien. En het eerste wat men hoorde was het geluid van lachende vrouwen. De deur ging verder open en nu kwamen twee verpleegsters te voorschijn die tussen hen in een menselijk skelet droegen. Ze liepen ermee de tuin in en bij de lichtpaars bloeiende tulpenboom gekomen begonnen de drie zowaar te dansen. “Eindelijk lente”, zei dokter V. die vanaf zijn balkon mooi zicht had op het tafereeltje.

De afstand was te groot om een foto te nemen. Hij zou toch eens serieus werk moeten maken van een lens waarmee je stukken dichterbij je onderwerp kon komen. Maar kijk, ze liepen al weer terug en zuster P. zag hem nu ook op zijn balkon staan. “Leuk!”, riep hij nu. “Als jullie even wachten kom ik zo een foto van jullie maken.”

En hoewel de twee aanvankelijk licht protesteerden, stonden ze even later bereidwillig te poseren. “Alleen jammer van die uniformen”, dacht dokter V. voor hij afdrukte.

Joep Eijkens

(eerder gepubliceerd op www.cubra.nl)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Fotoalbum Joep Eijkens, - Objets Trouvés (Ready-Mades)

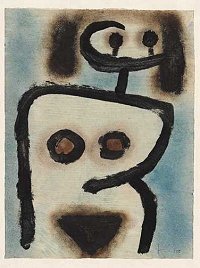

Paul Klee

(1879-1940)

Warum machst du das, Bimbo

Warum machst du das, Bimbo,

grad an der Tür?

«Das der wißt, was da ist!»

Ein Fogel feift ein lid auf sein

Schnabel, hohe Döne.

Paul Klee poetry, 1933

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Expressionism, Klee, Paul

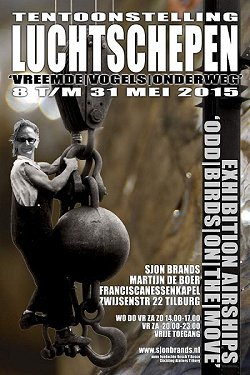

Balts met een bevlogen constructeur van gevleugelde luchtschepen

Hilde van Urvel, interview met Sjon Brands

“Waar zijt ge?” Ik kom een kamer binnen vol breed uitwaaierende bouwwerken. De fantasie is hier op hol geslagen. “Hier,” antwoordt ergens een stem, “achter de Zilte Zomergeus!” Achter een bont vogelgeraamte van gips en koper ontwaar ik een vrolijke man met warrig haar. Een kunstenaar. “Kunt u zo wel leven?” vraag ik. “Nog net,” antwoordt de man achter het beeld, “ik kan nog bij de deur en de telefoon. Het bed wordt al moeilijker.” De grote vogel tussen ons staart me doordringend aan. Twee koperen ogen keken de jager aan. “Wordt u hier niet een beetje gestoord van?” “Nee hoor, dat was ik al eerder. Het valt best mee.”

“Waar zijt ge?” Ik kom een kamer binnen vol breed uitwaaierende bouwwerken. De fantasie is hier op hol geslagen. “Hier,” antwoordt ergens een stem, “achter de Zilte Zomergeus!” Achter een bont vogelgeraamte van gips en koper ontwaar ik een vrolijke man met warrig haar. Een kunstenaar. “Kunt u zo wel leven?” vraag ik. “Nog net,” antwoordt de man achter het beeld, “ik kan nog bij de deur en de telefoon. Het bed wordt al moeilijker.” De grote vogel tussen ons staart me doordringend aan. Twee koperen ogen keken de jager aan. “Wordt u hier niet een beetje gestoord van?” “Nee hoor, dat was ik al eerder. Het valt best mee.”

De Nederlander Sjon Brands maakt vogels en sinds jaren luchtschepen. In een Engels aandoende kamer vol kasten, spiegels, scheepslampen en een rode Chesterfield, staan vijf levensgrote beelden van vogels in aanbouw. “Luchtschepen!” verbetert Sjon. Waarop ik niet kan nalaten: “Gaan ze ook vliegen?” “Nòg niet!” zegt hij beslist. Ik had het kunnen weten.

Wegwerpkunst

De vogels, pardon luchtschepen, zijn samengesteld uit alledaagse gebruiksvoorwerpen. Het is een feest van herkenning. Boeken, broodplankjes, een kraan, een bel, waterleiding, glazen, fittingen en tomatenblikjes. Veel glanzende metalen, glas en marmer. Een wonderlijke wereld uit alles wat wij mensen weggooien. “Veel gekregen en verder van rommelmarkten, vooral in Frankrijk.” “Waarom zover?” vraag ik. “Hier zie je veel plastic, lelijk plastic, vreselijke kleuren,” terwijl zijn hand over een koperen vogelkopje gaat, “maar daar vind je nog volop messing, brons of onyx. Prachtig. En de prijs is vriendelijker, hier vragen ze maar wat.”

“En dan maakt u zo’n luchtschip? Maakt u schetsen vooraf?” “Oh, nee,” wimpelt hij af, “ik heb geen enkel plan, daar is helemaal geen lol aan. Ik begin gewoon met het materiaal, met de rommel om me heen. Ik ga zitten spelen, net als vroeger met de Lego of het zand op het strand. Het ontstaat vanzelf.” “Leg eens uit,” werp ik tegen, “dat lijkt me iets te eenvoudig.” “Ik ga zitten kijken. Ik pak voorwerpen in mijn hand, of stukjes daarvan, en houd die tegen elkaar. Soms uren aan een stuk, kijken en nog eens kijken, Net zo lang tot ik iets nieuws ontdek. Hé, dat lijkt wel een kopje! Of, dat stukje glas heeft iets droevigs in zich!”

“Maar u weet toch wel waar u naar toe werkt?” “Nee, helemaal niet, dat zou ook niet goed zijn. Ik kan het weten. Je wordt een soort slaaf van je eigen benarde plannen. Het is veel prettiger om gewoon te spelen. En productiever. Je ontdekt mooiere dingen. Wat ik vooraf bedenk, hoe leuk dan ook, ziet er achteraf toch weer bedacht uit. Mager, vind ik, je ziet het eraan af. Soms kan het ermee door, maar het is zelden sprankelend, bijzonder of nieuw.”

“Maar u weet toch wel waar u naar toe werkt?” “Nee, helemaal niet, dat zou ook niet goed zijn. Ik kan het weten. Je wordt een soort slaaf van je eigen benarde plannen. Het is veel prettiger om gewoon te spelen. En productiever. Je ontdekt mooiere dingen. Wat ik vooraf bedenk, hoe leuk dan ook, ziet er achteraf toch weer bedacht uit. Mager, vind ik, je ziet het eraan af. Soms kan het ermee door, maar het is zelden sprankelend, bijzonder of nieuw.”

Mijn blik dwaalt door de overvolle kamer. Langzaam kan ik het rijk van veren, theezeefjes, lampen, flessen, schakelaars, tandwielen, borsteltjes, melkkannetjes, gordijnringen, bougies, plantjes en schedeltjes loslaten. Het zijn inderdaad luchtschepen, groteske vogeldieren die hier huizen, liggend, staand of vliegend. Gestaag dringen ze tot me door, het is een vreemde surrealistische wereld die begint te werken. “Waar gaat dit over?” vraag ik me af. Ik kan het niet goed thuisbrengen. Het is anders, anders dan ik gewend ben. Het is veel, bont, grillig, absurd en tegelijkertijd ook herkenbaar en prachtig, tot in het kleinste detail afgewerkt.

“Ik heb het geluk dat ik al mijn tijd mag besteden aan het maken van vogels,” zegt Sjon, “dus doe ik het graag goed, ik vind het een voorrecht om mooie dingen te mogen maken.” “Ambacht dus?” “Ook dat, niets op tegen, maar niet alleen, het gaat mij vooral om andere betekenissen, die je niet in het herkenbare ziet. “Zoals? Noem eens een voorbeeld.” “Nou, neem dit waterpompje, van een Opel Record geloof ik, voor mij is dit een vogel, een speciale vogel, een soort god, die op zijn troon, een gedroogde zeester, de wereld overziet. Een wereld helaas ook van geweld en dood, niet zo’n fijne wereld eigenlijk. Daar voel ik me ook mee verbonden en dat doet deze vogel voor mij. Maar jij mag er best ook iets heel anders in zien.”

Ik staar in de open bek van het waterpompje, god bedoel ik. Waar gaat dit over? Naast god staat een vuurtoren, een galg, een hijskraan, medicijnflesjes op pootjes en een rij vervaarlijke vogeltjes met gehelmde schedeltjes en gele ogen. “Eh, is het niet een beetje bijeengeraapt?” vraag ik voorzichtig. “Nee, bijeengekomen,” werpt hij tegen, “langzaam bij elkaar gekomen. Dat is een heel proces geweest, waarin toeval en willekeur als breekijzer gewerkt hebben.” Ongetwijfeld is dit de logica van een dada-kunstenaar, voor wie zelfs pruimen en asfalt bij elkaar passen. Wat niet wegneemt dat al die verschillende voorwerpen, al die vogeltjes en gebouwen op zijn luchtschepen, een grillig, maar ergens samenhangend geheel vormen. Het zijn allemaal kleine verhalen, die op heel eigen wijze iets vertellen over ons mens-zijn.

‘Anna Blume hat ein Vogel’

Terug naar de luchtschepen. En dus vraag ik hem: “Waarom luchtschepen?” “Ik hou van luchtschepen. Ze zijn mooi en majestueus. Zoals in films met alles erop en eraan. Prachtige vormen, boeiender dan een modern vliegtuig. Ik hou van vliegen. Ik zie ze vliegen, zou je bijna zeggen. Mijn luchtschepen zijn droomvogels, afgeladen met gedroomde bouwsels en vogeldiertjes. Als vliegende eilanden, als fladderende schepen, als dolende werelden. Ik heb laatst een fuut met een kleintje op zijn rug gezien, fantastisch!”

“Over de fuut gesproken, wat boeit u zo in vogels?” “Vogels staan voor vrijheid. Vreemd begrip eigenlijk, iedereen verlangt ernaar, iedereen verstaat er wat anders onder, en toch weten we allemaal waar het over gaat. Zeker in deze kneuterige tijd met al zijn regeltjes. Wij willen ons vrij kunnen bewegen, uit het platte vlak komen, los van dit wel erg platte land. Vogels staan ook voor vogelperspectief, jezelf kunnen zien terwijl je bezig bent, probeert wat van dit leven te maken. Tenslotte hebben vogels de hele IJstijd overleefd, een hele prestatie.”

“Over de fuut gesproken, wat boeit u zo in vogels?” “Vogels staan voor vrijheid. Vreemd begrip eigenlijk, iedereen verlangt ernaar, iedereen verstaat er wat anders onder, en toch weten we allemaal waar het over gaat. Zeker in deze kneuterige tijd met al zijn regeltjes. Wij willen ons vrij kunnen bewegen, uit het platte vlak komen, los van dit wel erg platte land. Vogels staan ook voor vogelperspectief, jezelf kunnen zien terwijl je bezig bent, probeert wat van dit leven te maken. Tenslotte hebben vogels de hele IJstijd overleefd, een hele prestatie.”

“En, vogels zijn net mensen. Wij denken dat we een stuk verder zijn, maar dat valt best tegen. Wij kunnen niet vliegen, van een toren duiken zonder dood te vallen, een fatsoenlijk ei leggen, zelf een nest bouwen of fluiten als de nachtegaal. Kakelen dat kunnen we wel, en kwetteren en snateren, de hele dag door, liefst mobiel. Net een bos vogels in de lente, alleen hebben zij geen apparaat of abonnement nodig, geen last van internet dat eruit ligt. Ze zijn eigenlijk veel slimmer.”

De kunstenaar raakt op dreef. “Mijn vogels zijn metaforen voor mensen, ik gebruik ze om onze goede bedoelingen en vooral al onze onvolkomenheden en ondeugden te beschrijven. Vechten, ruzie maken, het mooiste meisje inpikken, jaloezie. hebzucht, hamsteren, enzovoort. Vogels hebben vast geen last van goede bedoelingen, wèl van ondeugden. Maar die gaan ergens over, die gaan over het voortbestaan. Dan mag het. Wij maken ons druk om niks, om geld, de nieuwste iPhone, het zoveelste rokje, om de buurvrouw die weer eens te hard lacht.”

“Vogels zijn ook veel aardiger voor ons dan andersom. Wij mensen zijn de èchte beesten, wij stoppen vogels in kooien voor de gezelligheid, schieten ze af voor wat jachtplezier, vriezen ze in, vreten ze per kilo, kortwieken ze, ringen ze, verven ze of vermalen ze in straalmotoren. Ja, beschaving heet dat. Ooit vogels mensenverschrikkers zien bouwen? Of legbatterijen voor mensenmeisjes? Lijmstokjes, knalapparaten of netten? Nee toch? Geef mij maar vogels!”

“Vogels zijn ook veel aardiger voor ons dan andersom. Wij mensen zijn de èchte beesten, wij stoppen vogels in kooien voor de gezelligheid, schieten ze af voor wat jachtplezier, vriezen ze in, vreten ze per kilo, kortwieken ze, ringen ze, verven ze of vermalen ze in straalmotoren. Ja, beschaving heet dat. Ooit vogels mensenverschrikkers zien bouwen? Of legbatterijen voor mensenmeisjes? Lijmstokjes, knalapparaten of netten? Nee toch? Geef mij maar vogels!”

Onze kunstenaar draaft behoorlijk door. Ik dreig de greep op dit interview kwijt te raken. Ik grijp in. “Wacht even, maar waar gaat dit allemaal over? Waarom maakt u deze beelden?”

Het wordt stil, doodstil. De kunstenaar denkt na. “Tsja,” zegt hij, “daar vraagt u me wat.” Zijn blik dwaalt af en glijdt over zijn luchtschepen alsof die zijn antwoord zouden moeten formuleren. Een beetje moedeloos. Alsof hij niet meer in zijn eigen taal, zijn beelden, mag spreken. Alsof zijn luchtschepen niet genoeg te zeggen hebben. Alsof hem de mond gesnoerd is. “Tsja,” zegt hij, “het gaat over spelen, denk ik. Vooral over liefde en liefde en nog eens liefde. En ook over Weltschmerz en wat romantiek. Of zo. Wat eigenlijk allemaal hetzelfde is. Of niet? Wat moet ik hier nou over zeggen? Begrijpt u dat? Heeft u hier wat aan?”

Dit tekent de man, die zeven dagen per week van ’s morgens vroeg tot in de avond in de weer is met wat wij rommel plegen te noemen, die kleuren uit een dozijn lagen opbouwt, die geduldig duizenden veren op een vleugel plakt, die een waterpomp voor god aanziet en toch gelukkig is. En iedere dag opnieuw twijfelt, zich afvraagt waar hij mee bezig is en vooraan staat om eigen werk te relativeren. Maar als er één stille kracht in dit werk is, dat is dat wel die betrekkelijkheid, met andere woorden humor, die van deze vreemde luchtschepen afspat.

Hilde van Urvel

Hilde van Urvel, interview met Sjon Brands, oktober 2014

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Art & Literature News, Brands, Sjon, Sjon Brands, Theater van de Verloren Tijd

Saint-Étienne-de-Tinée

I

Quatorze Juillet wordt tot in

de kleinste gehuchten gevierd. Hier

in de bergen lijkt het vuurwerk

zelfs op zijn hoogste punt omlaag

te zijn tegen dat zwaarmassief décor.

Wijn vloeit, er wordt gelachen en

beschonken is men katholiek

in hart en ziel, in koor.

De slaap zo’n nacht schijnt

voortzetting te zijn van

feestgedruis en echolach en

vol wordt stilte dan gedroomd.

II

Quinze Juillet. Vanuit het raam van ’t hotel

waarachter jij toevallig even woont zie je

een oude dorpspastoor het plein aanvegen.

Zijn takkenbezem raspt net zo scherp de stilte

weg als het scheermes de stoppels van je wang.

De klokken gaan luiden: heel kalm zet hij

de bezem aan de kant en schuifelt zich

aan het hoofd van de uitvaartstoet die

doorheen de confetti de kerk aandoet.

De morgen na een feest of niet: er

wordt begraven want het leven moet weer door.

Achter de bergen rommelt donder.

Bert Bevers

Eerder verschenen in ’t Kofschip, Dilbeek, 16de jaargang, nummer 5

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Bevers, Bert

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature