Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Hendrik Marsman

(1899-1940)

De zee

Wie schrijft, schrijv’ in den geest van deze zee

of schrijve niet; hier ligt het maansteenrif

dat stand houdt als de vloed ons overvalt

en de cultuur gelijk Atlantis zinkt;

hier alleen scheert de wiekslag van het licht

de kim van het drievoudig continent

dat aan ons lied den blanken weerschijn schenkt

van zacht ivoor en koolzwart ebbenhout,

en in den dronk den geur der rozen mengt

met de extasen van den wingerdrank.

Hier golft de nacht van ‘t dionysisch schip

dat van de Zuilen naar den Hellespont

en van Damascus naar den Etna zwierf;

hier de fontein die naar het zenith sprong

en regenbogen naar de kusten wierp

van de moskee, de tempel en het kruis.

Hier heeft het hart de hoge stem gehoord

waardoor Odysseus zich bekoren liet

en ‘t woord dat Solon te Athene sprak;

en in de branding dezer kusten brak

de trots van Rome en van Babylon.

Zolang de europese wereld leeft

en, bloedend, droomt den roekelozen droom

waarin het kruishout als een wijnstok rankt,

ruist hier de bron, zweeft boven déze zee

het lichten van den creatieven geest.

Hendrik Marsman poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive M-N, Marsman, Hendrik

Lizette Woodworth Reese

(1856–1935)

Thomas A Kempis

Brother of mine, good monk with cowlëd head,

Walled from that world which thou hast long since fled,

And pacing thy green close beyond the sea,

I send my heart to thee.

Down gust-sweet walks, bordered by lavender,

While eastward, westward, the mad swallows whir,

All afternoon poring thy missal fair,

Serene thou pacest there.

Mixed with the words and fitting like a tune,

Thou hearest distantly the voice of June,—

The little, gossipping noises in the grass,

The bees that come and pass.

Fades the long day; the pool behind the hedge

Burns like a rose within the windy sedge;

The lilies ghostlier grow in the dim air;

The convent windows flare.

Yet still thou lingerest; from pastures steep,

Past the barred gate the shepherd drives his sheep;

A nightingale breaks forth, and for a space

Makes sweeter the sweet place.

Then the gray monks by hooded twos and threes

Move chapelward beneath the flaming trees;

Closing thy book, back by the alleys fair

Thou followest to prayer.

Born to these brawling days, this work-sick age,

Oft long I for thy simpler heritage;

A thought of thee is like a breath of bloom

Blown through a noisy room.

For thou art quick, not dead. I picture thee

Forever in that close beyond the sea;

And find, despite this weather’s headlong stir,

Peace and a comforter.

Lizette Woodworth Reese poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive Q-R, CLASSIC POETRY, Thomas a Kempis

Hans Hermans © photos: London 2013 (3)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: FDM in London, Hans Hermans Photos, Photography

Geschrokken keek hij op. Zag dat de buizerd in paniek tussen de dichte takken rond de kruin van de meidoorn fladderde, veel zachte veertjes verliezend die langzaam naar beneden dwarrelden. Toen pas zag hij Elysee bij de spoelbak.

Geschrokken keek hij op. Zag dat de buizerd in paniek tussen de dichte takken rond de kruin van de meidoorn fladderde, veel zachte veertjes verliezend die langzaam naar beneden dwarrelden. Toen pas zag hij Elysee bij de spoelbak.

Met zijn rechterhand hield hij Angela vast. Met de andere streelde hij haar dunne lijf. De andere kinderen zaten verstijfd van schrik in de spoelbak, hun ogen open, alsof ze waren betoverd. Zonder er verder over na te denken mikte Kaffa nauwkeurig met zijn linkerhand. Het mes trof de waarzegger in zijn poot. De man leek af te breken en zakte door zijn knieën. Wilde schreeuwen of vloeken of God weet wat, zijn mond ging tenminste open en dicht, maar er kwam alleen een vuile fontein van afgevreten woorden naar buiten. Angela sprong van de spoelbak, rende luidkeels gillend langs de geschrokken kraaien en de zieke jongen naar haar moeder, die naar buiten kwam hollen, en sprong haar in de armen. De katachtige heks Josanna had zich als eerste hersteld van de schrik en zakte languit in het water, kopje-onder. Om aandacht te trekken wilde ze laten zien dat het gebeuren haar verder koud liet. Wist zo’n kind veel! Opgehitst door de sensatie renden de kraaien kakelend rond het bed. Op het rode scherm voor zijn ogen zag de jongen de zwarte schaduwen op en neer dansen, wat hem deed schrikken. Hij sloeg een lange ijle kreet uit, waar zelfs opoe Ramesz een rilling van over de rug liep, zodat ze in haar stoel trilde en haar stoofje omviel, as en stof rond haar strooiend. Céleste liep tot onder de meidoorn. Ze hoorde de waarzegger janken van pijn en wilde hem helpen, maar iets in haar belette dat, al was het misschien alleen maar haar afkeer van hem.

Alleen de kaarters waren onverstoorbaar. Ze hadden niet eens bewondering voor Kaffa’s feilloze worp. In tegenstelling tot Jacob Ramesz, die enthousiast van zijn ene been op het andere hinkte en in de dovekwarteloren van opoe schreeuwde hoe goed Kaffa gemikt had. Opoe knikte maar, omdat ze bekend geluid opving. Jacob kon ouwehoeren wat hij wilde, opoe zou hem toch nooit meer tegenspreken. Een roofvogel, dacht Kaffa terwijl hij naar de waarzegger keek. Hij lachte met zijn hele gezicht. Godverdomme, een roofvogel verdiende niet beter. Kaffa trapte zijn hakken diep in het zand, om te blijven staan waar hij stond. Hij wist dat hij zich niet zou kunnen beheersen, dat hij Elysee zou afmaken als hij naar hem toe zou gaan. Het mes was in het been blijven steken. Vol afschuw trok Elysee het eruit. Bloed stroomde uit de wond. Op handen en knieën bereikte hij de ezel, die nog steeds aan de liguster in de caféhof vastgebonden stond, maakte hem los en kroop schrijlings op de rug van het dier. Traag en vol weerzin kwam de ezel in beweging. Schommelde het plein af op zijn danspasjes makende scheve poten, de man op zijn rug door elkaar rammelend als een zak knoken. Kaffa zag dat Josanna nog onder de waterspiegel lag. Roerloos, met open ogen. Hij dacht dat dit vreemde spelletje slecht kon aflopen voor het kind. Liep naar de spoelbak, trok haar uit het water en zette het wild om zich heen slaande schepsel op de grond. Hij begreep de woede van het kind niet. Zag dat er scheurtjes door het graniet van de spoelbak liepen, zo dun als haartjes. `Het is niets’, riep hij naar de vrouw die met Angela in haar armen naar hen keek. `Helemaal niets!’ Met afschuw zag hij het bloed aan het mes, dat nog in het zand lag. Raapte het op en keek nauwkeurig of het niet beschadigd was. Gelukkig had het niets geleden. Hij hield het lemmet in de waterstraal van de pomp om het bloed eraf te spoelen. Het mes tegen het licht houdend dat door de meidoorn scheen, keek hij of het schoon was. Maar het schijnsel van de meidoorn gaf alles de kleur van roze crèpepapier en roest. Kaffa zag dat Elysee zijn rijdier liet stoppen door hem met de vlakke hand op de kop te slaan. De waarzegger gleed van de ezel, ging met zijn rug tegen de muur van Chile zitten en rolde de pijp van zijn broek op. De kleine meisjes Azurri, bekomen van de schrik, waren achter de ezel aan gelopen. Om te laten zien dat ze geen angst meer hadden, raapten ze stenen op en gooiden die naar de waarzegger en zijn rijdier. De ezel, die meerdere malen werd getroffen, begreep dat het onveilig werd. Hij zette het op een lopen, zo vlug alsof hij door een horzel in zijn aars was gestoken. Zijn scheve poten ontwikkelden een ongekende vaart, hoewel ze soms onder hem uit sloegen, alsof hij over groene zeep liep. Zelfs de waarzegger liet zijn mond openvallen van verbazing toen hij het zag. Hij balde zijn vuisten naar de kinderen, maar die lachten hem uit. Elysee kon zich toch niet verweren. Hij kroop overeind. Op één been hinkend, het andere achter zich aan zeulend, verdween hij tussen de gebouwen van Chiles Plaats.

Ton van Reen: Landverbeuren (32)

wordt vervolgd

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Landverbeuren, Reen, Ton van

Elizabeth (Lizzie) Siddal

(1829-1862)

He and She and Angels Three

Ruthless hands have torn her

From one that loved her well;

Angels have upborn her,

Christ her grief to tell.

She shall stand to listen,

She shall stand and sing,

Till three winged angels

Her lover’s soul shall bring.

He and she and the angels three

Before God’s face shall stand;

There they shall pray among themselves

And sing at His right hand.

Elizabeth Siddal poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Siddal, Lizzy

Op 31 maart 2015 overleed Adriaan Cornelis (Ad) den Besten op 92 jarige leeftijd. Ad den Besten (1923-2015) was dichter, vertaler, essayist, psalmberijmer en uitgever van poëzie.

Ad den Besten debuteerde op 17-jarige leeftijd in het tijdschrift Opwaartsche Wegen. Hij studeerde eerst theologie, later Duits. Tijdens de oorlogsjaren schreef Den Besten bijdragen voor het surrealistische maandblad De Schone Zakdoek.

Ad den Besten debuteerde op 17-jarige leeftijd in het tijdschrift Opwaartsche Wegen. Hij studeerde eerst theologie, later Duits. Tijdens de oorlogsjaren schreef Den Besten bijdragen voor het surrealistische maandblad De Schone Zakdoek.

Ad den Besten zou zeer gewaardeerd worden als medewerker aan het Liedboek voor de Kerken en de Psalmberijming van 1968.

Na een prijs te hebben ontvangen voor zijn medewerking aan het Liedboek voor de Kerken, ontving hij in 1989 de Martinus Nijhoff Prijs voor zijn vertaling van gedichten van Friedrich Hölderlin.

Als redacteur van de Poëziereeks De Windroos, o.a. een springplank voor de Beweging van Vijftig, had hij grote invloed op de vernieuwing van de Nederlandse poëzie.

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Art & Literature News, In Memoriam

Emma Lazarus

(1849 – 1887)

Grief

There is a hungry longing in the soul,

A craving sense of emptiness and pain,

She may not satisfy nor yet control,

For all the teeming world looks void and vain.

No compensation in eternal spheres,

She knows the loneliness of all her years.

There is no comfort looking forth nor back,

The present gives the lie to all her past.

Will cruel time restore what she doth lack?

Why was no shadow of this doom forecast?

Ah! she hath played with many a keen-edged thing;

Naught is too small and soft to turn and sting.

In the unnatural glory of the hour,

Exalted over time, and death, and fate,

No earthly task appears beyond her power,

No possible endurance seemeth great.

She knows her misery and her majesty,

And recks not if she be to live or die.

Emma Lazarus poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Lazarus, Emma

Arthur Rimbaud

(1854-1891)

Bottom

La réalité étant trop épineuse pour mon grand caractère, — je me trouvai néanmoins chez ma dame, en gros oiseau gris bleu s’essorant vers les moulures du plafond et traînant l’aile dans les ombres de la soirée.

Je fus, au pied du baldaquin supportant ses bijoux adorés et ses chefs-d’œuvre physiques, un gros ours aux gencives violettes et au poil chenu de chagrin, les yeux aux cristaux et aux argents des consoles.

Tout se fit ombre et aquarium ardent. Au matin, — aube de juin batailleuse, — je courus aux champs, âne, claironnant et brandissant mon grief, jusqu’à ce que les Sabines de la banlieue vinrent se jeter à mon poitrail.

Arthur Rimbaud poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive Q-R, Arthur Rimbaud, Rimbaud, Arthur, Rimbaud, Arthur

Stefan Zweig

(1881-1942)

Junge Glut

Tiefe Nacht. –

Aus sinneheißem Traum bin ich erwacht.

Ich träumte von schimmernder Glieder Pracht

Von Frauen, die mit liebesfrohen und verständnisstillen

Verschwiegnen Blicken Wunsch und Sucht erfüllen,

Ich träumte von glühenden brennenden Küssen

Von trunkener Geigen laut jubelndem Klang,

Von wilden, berauschenden Glutgenüssen

Von Mädchen, die ich als Sieger bezwang …

Und jede Sehnsucht fand im Traum ihr Ende

Doch nun bin ich erwacht!

Allein! . . . . . . Allein!! . . . . .

… Und sinnetrunken tappen meine Hände

In schweigende Dunkelheiten hinein

Hinein in die leere, nichtssagende Nacht! …

Stefan Zweig poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive Y-Z, Stefan Zweig, Zweig, Stefan

Wachtend op lijn 3

Nu hoor ik voor de tweede keer in een minuut

een zelfde conversatie. Doodernstig staat een meisje

op dit ondergronds perron met een recordertje

te spelen. Daar drukt ze weer de opnameknop in,

luistert met haar stalen oor, spoelt rroetssjj terug

en draait met fonkelende ogen stemmen af die zij bezit:

dertig seconden terug in de tijd op dezelfde plek,

met geluiden van mensen die niet weten wat

ze moeten vinden. Ze oogt niet gek. Daar is de metro.

Zij hoeft niet mee. Ik kijk haar na, zie nieuwe

woorden zinloos op haar band verdwalen.

Waar ligt betekenis? In kogelgaten of de ruimte

daar tussen? Ik weet het niet, en zie verder leven,

verder.

Bert Bevers

(verschenen in Antwerpen – De stad in gedichten, Uitgeverij 521, Amsterdam, 2003)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Bevers, Bert

Journalist Warna Oosterbaan en fotograaf Theo Baart krijgen voor het boek Ons Erf – identiteit, erfgoed, culturele dynamiek de E. du Perronprijs 2014 toegekend. Deze prijs is bedoeld voor personen of instellingen die met een cultuuruiting in brede zin een bijdrage leveren aan een beter begrip van de multiculturele samenleving. Op donderdagavond 2 april reikt de Tilburgse Cultuurwethouder Marcelle Hendrickx de prijs uit. Voorafgaand aan de prijsuitreiking houdt Bas Heijne, onder meer columnist bij NRC Handelsblad, een lezing getiteld ‘De omgekeerde wereld’.

De multiculturele samenleving is een feit, maar daar is ook verzet tegen; mensen gaan dan vaak “het eigene” van de oude Nederlandse cultuur extra benadrukken. Wat zien wij, en anderen, als typisch voor het eigene aan onze cultuur? Volgens de E. du Perronjury doet voormalig NRC-journalist Warna Oosterbaan “intelligent verslag” van de zoektocht naar de betekenis van het nationale gevoel, de toekomst van de multiculturele samenleving en de rol van religie. Volgens het juryrapport ‘weet Oosterbaan met uitstapjes naar een variëteit aan cultuurdomeinen en wetenschappers in onberispelijk heldere taal zichtbaar te maken wat ons toch zo oproept tot introspectie of navelstaren’.

De multiculturele samenleving is een feit, maar daar is ook verzet tegen; mensen gaan dan vaak “het eigene” van de oude Nederlandse cultuur extra benadrukken. Wat zien wij, en anderen, als typisch voor het eigene aan onze cultuur? Volgens de E. du Perronjury doet voormalig NRC-journalist Warna Oosterbaan “intelligent verslag” van de zoektocht naar de betekenis van het nationale gevoel, de toekomst van de multiculturele samenleving en de rol van religie. Volgens het juryrapport ‘weet Oosterbaan met uitstapjes naar een variëteit aan cultuurdomeinen en wetenschappers in onberispelijk heldere taal zichtbaar te maken wat ons toch zo oproept tot introspectie of navelstaren’.

Voor dit boek fietste Warna Oosterbaan langs de Amsterdamse grachten en bezocht hij Kamp Westerbork, het Rietveld Schröderhuis en andere herinneringsplaatsen. Hij luisterde naar stadsgeluiden uit 1895, en reisde met antropologen mee naar Brazilië, Indonesië, Curaçao en Marokko. Ook interviewde hij sociologen, antropologen, historici en cultuurwetenschappers die meededen aan het NWO-onderzoeksprogramma ‘Culturele dynamiek’ over wat onze actuele en historische maatschappij kenmerkt. De beelden van fotograaf Theo Baart maken volgens de jury ‘de meerduidigheid van de nationale cultuur zichtbaar: soms herkenbaar in zijn alledaagsheid, soms verrassend vervreemdend’.

Bas Heijne-lezing over Verlichting, stammenstrijd en de EU: In zijn E. du Perron-lezing getiteld ‘De omgekeerde wereld’ onderzoekt schrijver en columnist Bas Heijne hoe de verlichting tot haar eigen vijand heeft kunnen worden. Waarom ontaardt een anti-racisme demonstratie in een onverkwikkelijke stammenstrijd? Hoe kan het dat de Europese Unie niet langer wordt gezien als een nieuwe gemeenschap, maar juist als een bedreiging van onze gemeenschap? Waarom lopen de gemoederen zo hoog wanneer de zwartheid van Zwarte Piet ter discussie wordt gesteld? Waarom vinden zovelen dat de vermoorde satirici van Charlie Hebdo te ver zijn gegaan?

In zijn lezing zal Heijne proberen antwoord te geven op deze en andere vragen, die volgens hem stuk voor stuk terugvoeren op een groeiende afkeer van de idealen van de Verlichting.

Andere genomineerden voor 2014 waren schrijver Peter Vermeersch met zijn boek Ex. Over een land dat zoek is en Fikry El Azzouzi met Drarrie in de nacht. De E. du Perronprijs is een initiatief van de gemeente Tilburg, de School of Humanities van Tilburg University en brabants kenniscentrum voor kunst en cultuur (bkkc). De prijs bestaat uit een geldbedrag van 2500 euro en een sjaal ontworpen door Miriam van der Lubbe en vervaardigd bij het TextielMuseum. In 2013 won Mohammed Benzakour de prijs voor zijn werk Yemma. Andere laureaten waren onder meer Koen Peeters (2012), Ramsey Nasr (2011), Alice Boot & Rob Woortman (2010), Abdelkader Benali (2009), Adriaan van Dis (2008) en Guus Kuijer (2007).

Andere genomineerden voor 2014 waren schrijver Peter Vermeersch met zijn boek Ex. Over een land dat zoek is en Fikry El Azzouzi met Drarrie in de nacht. De E. du Perronprijs is een initiatief van de gemeente Tilburg, de School of Humanities van Tilburg University en brabants kenniscentrum voor kunst en cultuur (bkkc). De prijs bestaat uit een geldbedrag van 2500 euro en een sjaal ontworpen door Miriam van der Lubbe en vervaardigd bij het TextielMuseum. In 2013 won Mohammed Benzakour de prijs voor zijn werk Yemma. Andere laureaten waren onder meer Koen Peeters (2012), Ramsey Nasr (2011), Alice Boot & Rob Woortman (2010), Abdelkader Benali (2009), Adriaan van Dis (2008) en Guus Kuijer (2007).

De E. du Perronprijs wil mensen en instellingen bekronen, die in het multiculturele Nederland, evenals Du Perron, door middel van cultuuruitingen in brede zin, grenzen durven te doorbreken en scheidsmuren kunnen slechten. De laureaten van de E. du Perronprijs tonen zich betrokken bij de maatschappij zonder zichzelf daarin te verliezen; zij zoeken hun eigen waarden in relatie tot en soms in confrontatie met die maatschappij. Soms beschikken zij over de instelling van de outsider, die bepaalde dingen scherper ziet dan degenen die in de maalstroom van de gebeurtenissen zijn opgenomen. Zij overstijgen de waan van de dag in hun originele visie en verbeelding daarvan. Zij zijn nieuwsgierig naar de drijfveren van mensen en zoeken zichzelf te definiëren in relatie tot de ander.

# Meer informatie website duperronprijs

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Art & Literature News, Eddy du Perron, MONTAIGNE

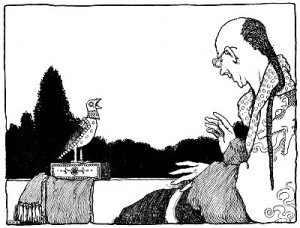

Hans Christian Andersen

(1805—1875)

The nightingale

In China, you know, the emperor is a Chinese, and all those about him are Chinamen also. The story I am going t tell you happened a great many years ago, so it is well to hear it now before it is forgotten. The emperor’s palac was the most beautiful in the world. It was built entirely of porcelain, and very costly, but so delicate and brittle tha whoever touched it was obliged to be careful. In the garden could be seen the most singular flowers, with prett silver bells tied to them, which tinkled so that every one who passed could not help noticing the flowers.

Indeed everything in the emperor’s garden was remarkable, and it extended so far that the gardener himself did not kno where it ended. Those who travelled beyond its limits knew that there was a noble forest, with lofty trees, slopin down to the deep blue sea, and the great ships sailed under the shadow of its branches. In one of these trees live a nightingale, who sang so beautifully that even the poor fishermen, who had so many other things to do, woul stop and listen. Sometimes, when they went at night to spread their nets, they would hear her sing, and say, “Oh, i not that beautiful?” But when they returned to their fishing, they forgot the bird until the next night. Then they woul hear it again, and exclaim “Oh, how beautiful is the nightingale’s song!

Travellers from every country in the world came to the city of the emperor, which they admired very much, as well as the palace and gardens; but when they heard the nightingale, they all declared it to be the best of all.

And the travellers, on their return home, related what they had seen; and learned men wrote books, containing descriptions of the town, the palace, and the gardens; but they did not forget the nightingale, which was really the greatest wonder. And those who could write poetry composed beautiful verses about the nightingale, who lived in a forest near the deep sea.

The books travelled all over the world, and some of them came into the hands of the emperor; and he sat in his golden chair, and, as he read, he nodded his approval every moment, for it pleased him to find such a beautiful description of his city, his palace, and his gardens. But when he came to the words, “the nightingale is the most beautiful of all,” he exclaimed:

“What is this? I know nothing of any nightingale. Is there such a bird in my empire? and even in my garden? I have never heard of it. Something, it appears, may be learnt from books.”

Then he called one of his lords-in-waiting, who was so high-bred, that when any in an inferior rank to himself spoke to him, or asked him a question, he would answer, “Pooh,” which means nothing.

“There is a very wonderful bird mentioned here, called a nightingale,” said the emperor; “they say it is the best thing in my large kingdom. Why have I not been told of it?”

“I have never heard the name,” replied the cavalier; “she has not been presented at court.”

“It is my pleasure that she shall appear this evening.” said the emperor; “the whole world knows what I possess better than I do myself.”

“I have never heard of her,” said the cavalier; “yet I will endeavor to find her.”

But where was the nightingale to be found? The nobleman went up stairs and down, through halls and passages; yet none of those whom he met had heard of the bird. So he returned to the emperor, and said that it must be a fable, invented by those who had written the book. “Your imperial majesty,” said he, “cannot believe everything contained in books; sometimes they are only fiction, or what is called the black art.”

“But the book in which I have read this account,” said the emperor, “was sent to me by the great and mighty emperor of Japan, and therefore it cannot contain a falsehood. I will hear the nightingale, she must be here this evening; she has my highest favor; and if she does not come, the whole court shall be trampled upon after supper is ended.”

“Tsing-pe!” cried the lord-in-waiting, and again he ran up and down stairs, through all the halls and corridors; and half the court ran with him, for they did not like the idea of being trampled upon. There was a great inquiry about this wonderful nightingale, whom all the world knew, but who was unknown to the court.

At last they met with a poor little girl in the kitchen, who said, “Oh, yes, I know the nightingale quite well; indeed, she can sing. Every evening I have permission to take home to my poor sick mother the scraps from the table; she lives down by the sea-shore, and as I come back I feel tired, and I sit down in the wood to rest, and listen to the nightingale’s song. Then the tears come into my eyes, and it is just as if my mother kissed me.”

“Little maiden,” said the lord-in-waiting, “I will obtain for you constant employment in the kitchen, and you shall have permission to see the emperor dine, if you will lead us to the nightingale; for she is invited for this evening to the palace.”

So she went into the wood where the nightingale sang, and half the court followed her. As they went along, a cow began lowing.

“Oh,” said a young courtier, “now we have found her; what wonderful power for such a small creature; I have certainly heard it before.”

“No, that is only a cow lowing,” said the little girl; “we are a long way from the place yet.”

Then some frogs began to croak in the marsh.

“Beautiful,” said the young courtier again. “Now I hear it, tinkling like little church bells.”

“No, those are frogs,” said the little maiden; “but I think we shall soon hear her now:”

And presently the nightingale began to sing.

“Hark, hark! there she is,” said the girl, “and there she sits,” she added, pointing to a little gray bird who was perched on a bough.

“Is it possible?” said the lord-in-waiting, “I never imagined it would be a little, plain, simple thing like that. She has certainly changed color at seeing so many grand people around her.”

“Little nightingale,” cried the girl, raising her voice, “our most gracious emperor wishes you to sing before him.”

“With the greatest pleasure,” said the nightingale, and began to sing most delightfully.

“It sounds like tiny glass bells,” said the lord-in-waiting, “and see how her little throat works. It is surprising that we have never heard this before; she will be a great success at court.”

“Shall I sing once more before the emperor?” asked the nightingale, who thought he was present.

“My excellent little nightingale,” said the courtier, “I have the great pleasure of inviting you to a court festival this evening, where you will gain imperial favor by your charming song.”

“My song sounds best in the green wood,” said the bird; but still she came willingly when she heard the emperor’s wish.

The palace was elegantly decorated for the occasion. The walls and floors of porcelain glittered in the light of a thousand lamps. Beautiful flowers, round which little bells were tied, stood in the corridors: what with the running to and fro and the draught, these bells tinkled so loudly that no one could speak to be heard.

In the centre of the great hall, a golden perch had been fixed for the nightingale to sit on. The whole court was present, and the little kitchen-maid had received permission to stand by the door. She was not installed as a real court cook. All were in full dress, and every eye was turned to the little gray bird when the emperor nodded to her to begin.

The nightingale sang so sweetly that the tears came into the emperor’s eyes, and then rolled down his cheeks, as her song became still more touching and went to every one’s heart. The emperor was so delighted that he declared the nightingale should have his gold slipper to wear round her neck, but she declined the honor with thanks: she had been sufficiently rewarded already.

“I have seen tears in an emperor’s eyes,” she said, “that is my richest reward. An emperor’s tears have wonderful power, and are quite sufficient honor for me;” and then she sang again more enchantingly than ever.

“That singing is a lovely gift;” said the ladies of the court to each other; and then they took water in their mouths to make them utter the gurgling sounds of the nightingale when they spoke to any one, so thay they might fancy themselves nightingales. And the footmen and chambermaids also expressed their satisfaction, which is saying a great deal, for they are very difficult to please. In fact the nightingale’s visit was most successful.

She was now to remain at court, to have her own cage, with liberty to go out twice a day, and once during the night. Twelve servants were appointed to attend her on these occasions, who each held her by a silken string fastened to her leg. There was certainly not much pleasure in this kind of flying.

The whole city spoke of the wonderful bird, and when two people met, one said “nightin,” and the other said “gale,” and they understood what was meant, for nothing else was talked of. Eleven peddlers’ children were named after her, but not of them could sing a note.

One day the emperor received a large packet on which was written “The Nightingale.”

“Here is no doubt a new book about our celebrated bird,” said the emperor. But instead of a book, it was a work of art contained in a casket, an artificial nightingale made to look like a living one, and covered all over with diamonds, rubies, and sapphires. As soon as the artificial bird was wound up, it could sing like the real one, and could move its tail up and down, which sparkled with silver and gold. Round its neck hung a piece of ribbon, on which was written “The Emperor of China’s nightingale is poor compared with that of the Emperor of Japan’s.”

“This is very beautiful,” exclaimed all who saw it, and he who had brought the artificial bird received the title of “Imperial nightingale-bringer-in-chief.”

“Now they must sing together,” said the court, “and what a duet it will be.”

But they did not get on well, for the real nightingale sang in its own natural way, but the artificial bird sang only waltzes. “That is not a fault,” said the music-master, “it is quite perfect to my taste,” so then it had to sing alone, and was as successful as the real bird; besides, it was so much prettier to look at, for it sparkled like bracelets and breast-pins.

Thirty three times did it sing the same tunes without being tired; the people would gladly have heard it again, but the emperor said the living nightingale ought to sing something. But where was she? No one had noticed her when she flew out at the open window, back to her own green woods.

“What strange conduct,” said the emperor, when her flight had been discovered; and all the courtiers blamed her, and said she was a very ungrateful creature. “But we have the best bird after all,” said one, and then they would have the bird sing again, although it was the thirty-fourth time they had listened to the same piece, and even then they had not learnt it, for it was rather difficult. But the music-master praised the bird in the highest degree, and even asserted that it was better than a real nightingale, not only in its dress and the beautiful diamonds, but also in its musical power.

“For you must perceive, my chief lord and emperor, that with a real nightingale we can never tell what is going to be sung, but with this bird everything is settled. It can be opened and explained, so that people may understand how the waltzes are formed, and why one note follows upon another.”

“This is exactly what we think,” they all replied, and then the music-master received permission to exhibit the bird to the people on the following Sunday, and the emperor commanded that they should be present to hear it sing. When they heard it they were like people intoxicated; however it must have been with drinking tea, which is quite a Chinese custom. They all said “Oh!” and held up their forefingers and nodded, but a poor fisherman, who had heard the real nightingale, said, “it sounds prettily enough, and the melodies are all alike; yet there seems something wanting, I cannot exactly tell what.”

And after this the real nightingale was banished from the empire.

The artificial bird was placed on a silk cushion close to the emperor’s bed. The presents of gold and precious stones which had been received with it were round the bird, and it was now advanced to the title of “Little Imperial Toilet Singer,” and to the rank of No. 1 on the left hand; for the emperor considered the left side, on which the heart lies, as the most noble, and the heart of an emperor is in the same place as that of other people. The music-master wrote a work, in twenty-five volumes, about the artificial bird, which was very learned and very long, and full of the most difficult Chinese words; yet all the people said they had read it, and understood it, for fear of being thought stupid and having their bodies trampled upon.

So a year passed, and the emperor, the court, and all the other Chinese knew every little turn in the artificial bird’s song; and for that same reason it pleased them better. They could sing with the bird, which they often did. The street-boys sang, “Zi-zi-zi, cluck, cluck, cluck,” and the emperor himself could sing it also. It was really most amusing.

One evening, when the artificial bird was singing its best, and the emperor lay in bed listening to it, something inside the bird sounded “whizz.” Then a spring cracked. “Whir-r-r-r” went all the wheels, running round, and then the music stopped.

The emperor immediately sprang out of bed, and called for his physician; but what could he do? Then they sent for a watchmaker; and, after a great deal of talking and examination, the bird was put into something like order; but he said that it must be used very carefully, as the barrels were worn, and it would be impossible to put in new ones without injuring the music. Now there was great sorrow, as the bird could only be allowed to play once a year; and even that was dangerous for the works inside it. Then the music-master made a little speech, full of hard words, and declared that the bird was as good as ever; and, of course no one contradicted him.

Five years passed, and then a real grief came upon the land. The Chinese really were fond of their emperor, and he now lay so ill that he was not expected to live. Already a new emperor had been chosen and the people who stood in the street asked the lord-in-waiting how the old emperor was.

But he only said, “Pooh!” and shook his head.

Cold and pale lay the emperor in his royal bed; the whole court thought he was dead, and every one ran away to pay homage to his successor. The chamberlains went out to have a talk on the matter, and the ladies’-maids invited company to take coffee. Cloth had been laid down on the halls and passages, so that not a footstep should be heard, and all was silent and still. But the emperor was not yet dead, although he lay white and stiff on his gorgeous bed, with the long velvet curtains and heavy gold tassels. A window stood open, and the moon shone in upon the emperor and the artificial bird.

The poor emperor, finding he could scarcely breathe with a strange weight on his chest, opened his eyes, and saw Death sitting there. He had put on the emperor’s golden crown, and held in one hand his sword of state, and in the other his beautiful banner. All around the bed and peeping through the long velvet curtains, were a number of strange heads, some very ugly, and others lovely and gentle-looking. These were the emperor’s good and bad deeds, which stared him in the face now Death sat at his heart.

“Do you remember this?” “Do you recollect that?” they asked one after another, thus bringing to his remembrance circumstances that made the perspiration stand on his brow.

“I know nothing about it,” said the emperor. “Music! music!” he cried; “the large Chinese drum! that I may not hear what they say.”

But they still went on, and Death nodded like a Chinaman to all they said.

“Music! music!” shouted the emperor. “You little precious golden bird, sing, pray sing! I have given you gold and costly presents; I have even hung my golden slipper round your neck. Sing! sing!”

But the bird remained silent. There was no one to wind it up, and therefore it could not sing a note. Death continued to stare at the emperor with his cold, hollow eyes, and the room was fearfully still.

Suddenly there came through the open window the sound of sweet music. Outside, on the bough of a tree, sat the living nightingale. She had heard of the emperor’s illness, and was therefore come to sing to him of hope and trust. And as she sung, the shadows grew paler and paler; the blood in the emperor’s veins flowed more rapidly, and gave life to his weak limbs; and even Death himself listened, and said, “Go on, little nightingale, go on.”

“Then will you give me the beautiful golden sword and that rich banner? and will you give me the emperor’s crown?” said the bird.

So Death gave up each of these treasures for a song; and the nightingale continued her singing. She sung of the quiet churchyard, where the white roses grow, where the elder-tree wafts its perfume on the breeze, and the fresh, sweet grass is moistened by the mourners’ tears. Then Death longed to go and see his garden, and floated out through the window in the form of a cold, white mist.

“Thanks, thanks, you heavenly little bird. I know you well. I banished you from my kingdom once, and yet you have charmed away the evil faces from my bed, and banished Death from my heart, with your sweet song. How can I reward you?”

“You have already rewarded me,” said the nightingale. “I shall never forget that I drew tears from your eyes the first time I sang to you. These are the jewels that rejoice a singer’s heart. But now sleep, and grow strong and well again. I will sing to you again.”

And as she sung, the emperor fell into a sweet sleep; and how mild and refreshing that slumber was!

When he awoke, strengthened and restored, the sun shone brightly through the window; but not one of his servants had returned– they all believed he was dead; only the nightingale still sat beside him, and sang.

“You must always remain with me,” said the emperor. “You shall sing only when it pleases you; and I will break the artificial bird into a thousand pieces.”

“No; do not do that,” replied the nightingale; “the bird did very well as long as it could. Keep it here still. I cannot live in the palace, and build my nest; but let me come when I like. I will sit on a bough outside your window, in the evening, and sing to you, so that you may be happy, and have thoughts full of joy. I will sing to you of those who are happy, and those who suffer; of the good and the evil, who are hidden around you. The little singing bird flies far from you and your court to the home of the fisherman and the peasant’s cot. I love your heart better than your crown; and yet something holy lingers round that also. I will come, I will sing to you; but you must promise me one thing.”

“Everything,” said the emperor, who, having dressed himself in his imperial robes, stood with the hand that held the heavy golden sword pressed to his heart.

“I only ask one thing,” she replied; “let no one know that you have a little bird who tells you everything. It will be best to conceal it.”

So saying, the nightingale flew away.

The servants now came in to look after the dead emperor; when, lo! there he stood, and, to their astonishment, said, “Good morning.”

END

Hans Christian Andersen fairy tales and stories

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Andersen, Andersen, Hans Christian, Archive A-B, Grimm, Andersen e.o.: Fables, Fairy Tales & Stories

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature