Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

Mels klopt zijn schouders af, een routinehandeling, altijd bang dat Lizet roos op zijn jas vindt. Ze heeft een hekel aan roos. Vaak borstelt ze de schouders van zijn jas af. Op straat moeten de mensen weten dat ze voor hem zorgt.

Op weg naar huis passeert hij het voormalige huis van Tijger, waarin nu de jongere zus van Tijger woont. Met haar heeft hij nauwelijks contact. Ze groeten elkaar. Soms maken ze een praatje, maar nooit over vroeger. Er zijn voor haar weinig mooie herinneringen overgebleven.

Op weg naar huis passeert hij het voormalige huis van Tijger, waarin nu de jongere zus van Tijger woont. Met haar heeft hij nauwelijks contact. Ze groeten elkaar. Soms maken ze een praatje, maar nooit over vroeger. Er zijn voor haar weinig mooie herinneringen overgebleven.

Haar vader die overleden is toen ze net geboren was. Tijger die ze nauwelijks heeft gekend. Haar moeder die gek was geworden van verdriet en zichzelf had opgeknoopt op de zolder, waar haar dochter, nog net geen zestien, haar had gevonden. Misschien dat de dochter zich daarom nooit aan iemand heeft kunnen hechten. Drie keer is ze getrouwd geweest, drie keer zijn de mannen vertrokken.

Hij kijkt altijd weer naar die deur. Nog steeds dezelfde deur, dezelfde vorm, maar in de loop der jaren met vele kleuren verf bestreken, vaak er afgebrand en weer opnieuw geschilderd.

Alle kleuren heeft de deur gehad, passend bij de stemming van de bewoners. Grijs in de jaren van Tijgers jeugd. Paars toen de jongere zus er woonde met een jonge man die aan yoga deed en elke dag op zijn kop voor het raam stond. Groen toen ze er woonde met een langharige man die dag en nacht blokfluit speelde en die haar twee kinderen naliet toen hij vertrok voor een wereldreis waarvan hij nooit was teruggekomen. Rood toen ze met een andere man ging samenwonen. En weer grijs, omdat die man zomaar verdwenen was en haar met een derde kind liet zitten. Al haar kindjes heeft ze rood haar meegegeven, als eerbetoon aan haar moeder.

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (082)

wordt vervolgd

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

The Romancers

It was autumn in London, that blessed season between the harshness of winter and the insincerities of summer; a trustful season when one buys bulbs and sees to the registration of one’s vote, believing perpetually in spring and a change of Government.

Morton Crosby sat on a bench in a secluded corner of Hyde Park, lazily enjoying a cigarette and watching the slow grazing promenade of a pair of snow-geese, the male looking rather like an albino edition of the russet-hued female. Out of the corner of his eye Crosby also noted with some interest the hesitating hoverings of a human figure, which had passed and repassed his seat two or three times at shortening intervals, like a wary crow about to alight near some possibly edible morsel. Inevitably the figure came to an anchorage on the bench, within easy talking distance of its original occupant. The uncared-for clothes, the aggressive, grizzled beard, and the furtive, evasive eye of the new-comer bespoke the professional cadger, the man who would undergo hours of humiliating tale-spinning and rebuff rather than adventure on half a day’s decent work.

Morton Crosby sat on a bench in a secluded corner of Hyde Park, lazily enjoying a cigarette and watching the slow grazing promenade of a pair of snow-geese, the male looking rather like an albino edition of the russet-hued female. Out of the corner of his eye Crosby also noted with some interest the hesitating hoverings of a human figure, which had passed and repassed his seat two or three times at shortening intervals, like a wary crow about to alight near some possibly edible morsel. Inevitably the figure came to an anchorage on the bench, within easy talking distance of its original occupant. The uncared-for clothes, the aggressive, grizzled beard, and the furtive, evasive eye of the new-comer bespoke the professional cadger, the man who would undergo hours of humiliating tale-spinning and rebuff rather than adventure on half a day’s decent work.

For a while the new-comer fixed his eyes straight in front of him in a strenuous, unseeing gaze; then his voice broke out with the insinuating inflection of one who has a story to retail well worth any loiterer’s while to listen to.

“It’s a strange world,” he said.

As the statement met with no response he altered it to the form of a question.

“I daresay you’ve found it to be a strange world, mister?”

“As far as I am concerned,” said Crosby, “the strangeness has worn off in the course of thirty-six years.”

“Ah,” said the greybeard, “I could tell you things that you’d hardly believe. Marvellous things that have really happened to me.”

“Nowadays there is no demand for marvellous things that have really happened,” said Crosby discouragingly; “the professional writers of fiction turn these things out so much better. For instance, my neighbours tell me wonderful, incredible things that their Aberdeens and chows and borzois have done; I never listen to them. On the other hand, I have read ‘The Hound of the Baskervilles’ three times.”

The greybeard moved uneasily in his seat; then he opened up new country.

“I take it that you are a professing Christian,” he observed.

“I am a prominent and I think I may say an influential member of the Mussulman community of Eastern Persia,” said Crosby, making an excursion himself into the realms of fiction.

The greybeard was obviously disconcerted at this new check to introductory conversation, but the defeat was only momentary.

“Persia. I should never have taken you for a Persian,” he remarked, with a somewhat aggrieved air.

“I am not,” said Crosby; “my father was an Afghan.”

“An Afghan!” said the other, smitten into bewildered silence for a moment. Then he recovered himself and renewed his attack.

“Afghanistan. Ah! We’ve had some wars with that country; now, I daresay, instead of fighting it we might have learned something from it. A very wealthy country, I believe. No real poverty there.”

He raised his voice on the word “poverty” with a suggestion of intense feeling. Crosby saw the opening and avoided it.

“It possesses, nevertheless, a number of highly talented and ingenious beggars,” he said; “if I had not spoken so disparagingly of marvellous things that have really happened I would tell you the story of Ibrahim and the eleven camel-loads of blotting-paper. Also I have forgotten exactly how it ended.”

“My own life-story is a curious one,” said the stranger, apparently stifling all desire to hear the history of Ibrahim; “I was not always as you see me now.”

“We are supposed to undergo complete change in the course of every seven years,” said Crosby, as an explanation of the foregoing announcement.

“I mean I was not always in such distressing circumstances as I am at present,” pursued the stranger doggedly.

“That sounds rather rude,” said Crosby stiffly, “considering that you are at present talking to a man reputed to be one of the most gifted conversationalists of the Afghan border.”

“I don’t mean in that way,” said the greybeard hastily; “I’ve been very much interested in your conversation. I was alluding to my unfortunate financial situation. You mayn’t hardly believe it, but at the present moment I am absolutely without a farthing. Don’t see any prospect of getting any money, either, for the next few days. I don’t suppose you’ve ever found yourself in such a position,” he added.

“In the town of Yom,” said Crosby, “which is in Southern Afghanistan, and which also happens to be my birthplace, there was a Chinese philosopher who used to say that one of the three chiefest human blessings was to be absolutely without money. I forget what the other two were.”

“Ah, I daresay,” said the stranger, in a tone that betrayed no enthusiasm for the philosopher’s memory; “and did he practise what he preached? That’s the test.”

“He lived happily with very little money or resources,” said Crosby.

“Then I expect he had friends who would help him liberally whenever he was in difficulties, such as I am in at present.”

“In Yom,” said Crosby, “it is not necessary to have friends in order to obtain help. Any citizen of Yom would help a stranger as a matter of course.”

The greybeard was now genuinely interested.

The conversation had at last taken a favourable turn.

“If someone, like me, for instance, who was in undeserved difficulties, asked a citizen of that town you speak of for a small loan to tide over a few days’ impecuniosity — five shillings, or perhaps a rather larger sum — would it be given to him as a matter of course?”

“There would be a certain preliminary,” said Crosby; “one would take him to a wine-shop and treat him to a measure of wine, and then, after a little high-flown conversation, one would put the desired sum in his hand and wish him good-day. It is a roundabout way of performing a simple transaction, but in the East all ways are roundabout.”

The listener’s eyes were glittering.

“Ah,” he exclaimed, with a thin sneer ringing meaningly through his words, “I suppose you’ve given up all those generous customs since you left your town. Don’t practise them now, I expect.”

“No one who has lived in Yom,” said Crosby fervently, “and remembers its green hills covered with apricot and almond trees, and the cold water that rushes down like a caress from the upland snows and dashes under the little wooden bridges, no one who remembers these things and treasures the memory of them would ever give up a single one of its unwritten laws and customs. To me they are as binding as though I still lived in that hallowed home of my youth.”

“Then if I was to ask you for a small loan —” began the greybeard fawningly, edging nearer on the seat and hurriedly wondering how large he might safely make his request, “if I was to ask you for, say —”

“At any other time, certainly,” said Crosby; “in the months of November and December, however, it is absolutely forbidden for anyone of our race to give or receive loans or gifts; in fact, one does not willingly speak of them. It is considered unlucky. We will therefore close this discussion.”

“But it is still October!” exclaimed the adventurer with an eager, angry whine, as Crosby rose from his seat; “wants eight days to the end of the month!”

“The Afghan November began yesterday,” said Crosby severely, and in another moment he was striding across the Park, leaving his recent companion scowling and muttering furiously on the seat.

“I don’t believe a word of his story,” he chattered to himself; “pack of nasty lies from beginning to end. Wish I’d told him so to his face. Calling himself an Afghan!”

The snorts and snarls that escaped from him for the next quarter of an hour went far to support the truth of the old saying that two of a trade never agree.

The Romancers

From ‘Beasts and Super-Beasts’

by Saki (H. H. Munro)

(1870 – 1916)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Saki, Saki, The Art of Reading

An indispensable anthology of brilliant hard-to-find writings by Poe on poetry, the imagination, humor, and the sublime which adds a new dimension to his stature as a speculative thinker and philosopher. Essays (in translation) by Charles Baudelaire, Stéphane Mallarmé, Paul Valéry, & André Breton shed light on Poe’s relevance within European literary tradition.

These are the arcana of Edgar Allan Poe: writings on wit, humor, dreams, drunkenness, genius, madness, and apocalypse. Here is the mind of Poe at its most colorful, its most incisive, and its most exceptional.

Edgar Allan Poe’s dark, melodic poems and tales of terror and detection are known to readers everywhere, but few are familiar with his cogent literary criticism, or his speculative thinking in science, psychology or philosophy. This book is an attempt to present his lesser known, out of print, or hard to find writings in a single volume, with emphasis on the theoretical and esoteric. The second part, “The Friend View,” includes seminal essays by Poe’s famous admirers in France, clarifying his international literary importance.

Edgar Allan Poe’s dark, melodic poems and tales of terror and detection are known to readers everywhere, but few are familiar with his cogent literary criticism, or his speculative thinking in science, psychology or philosophy. This book is an attempt to present his lesser known, out of print, or hard to find writings in a single volume, with emphasis on the theoretical and esoteric. The second part, “The Friend View,” includes seminal essays by Poe’s famous admirers in France, clarifying his international literary importance.

America has never seen such a personage as Edgar Allan Poe. He is a figure who appears once an epoch, before passing into myth. American critics from Henry James to T. S. Eliot have disparaged and attempted to explain away his influence to no end, save to perpetuate his fame. Even the disdainful Eliot once conceded, “and yet one cannot be sure that one’s own writing has not been influence by Poe.”

Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849), born in Boston, Massachusetts, was an American poet, writer, editor, and literary critic. He is well known for his haunting poetry and mysterious short stories. Regarded as being a central figure of Romanticism, he is also considered the inventor of detective fiction and the growing science fiction genre. Some of his most famous works include poems such as The Raven, Annabel Lee, and A Dream Within a Dream; tales such as The Cask of Amontillado, The Masque of Red Death, and The Tell-Tale Heart.

Title: The Unknown Poe

Subtitle: An Anthology of Fugitive Writings

Author: Edgar Allan Poe

Edited by Raymond Foye

Publisher: City Lights Publishers

Format: Paperback

124 pages

1980

ISBN-10 0872861104

ISBN-13 9780872861107

List Price $11.95

# American writers

Edgar Allan Poe

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, - Book Stories, Archive O-P, Archive O-P, Art & Literature News, Edgar Allan Poe, Poe, Edgar Allan, Poe, Edgar Allan, Tales of Mystery & Imagination

A series of disruptive, unnerving sounds haunts the fictional writings of Franz Kafka.

These include the painful squeak in Gregor Samsa’s voice, the indeterminate whistling of Josefine the singer, the relentless noise in “The Burrow,” and telephonic disturbances in The Castle.

These include the painful squeak in Gregor Samsa’s voice, the indeterminate whistling of Josefine the singer, the relentless noise in “The Burrow,” and telephonic disturbances in The Castle.

In Kafka and Noise, Kata Gellen applies concepts and vocabulary from film theory to Kafka’s works in order to account for these unsettling sounds. Rather than try to decode these noises, Gellen explores the complex role they play in Kafka’s larger project.

Kafka and Noise offers a method for pursuing intermedial research in the humanities—namely, via the productive “misapplication” of theoretical tools, which exposes the contours, conditions, and expressive possibilities of the media in question. This book will be of interest to scholars of modernism, literature, cinema, and sound, as well as to anyone wishing to explore how artistic and technological media shape our experience of the world and the possibilities for representing it.

Kata Gellen is an assistant professor in the Department of Germanic Languages and Literature at Duke University.

Kata Gellen (Author)

Kafka and Noise.

The Discovery of Cinematic Sound in Literary Modernism

272 pages

Northwestern University Press

Literary Criticism

Cloth Text – $99.95

ISBN 978-0-8101-3894-0

Paper Text – $34.95

ISBN 978-0-8101-3893-3

Publication Date: January 2019

# new books

The Discovery of Cinematic Sound in Literary Modernism

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: # Music Archive, #Archive A-Z Sound Poetry, #Archive Concrete & Visual Poetry, *Concrete + Visual Poetry K-O, - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive G-H, Archive K-L, Art & Literature News, Franz Kafka, Kafka, Franz, Kafka, Franz, Modernisme

Tijger grijpt de punterstok om de boot uit het riet te houden. Grootvader Bernhard staat voor zijn molenhuis en zwaait hen na.

`Je zult zelf zien dat de Chinezen op hun handen lopen’, roept hij. `Ze eten met hun voeten.’

`Je zult zelf zien dat de Chinezen op hun handen lopen’, roept hij. `Ze eten met hun voeten.’

`Ik stuur u een kaart van het paleis van de keizer’, roept Mels.

Hij roeit. Hij roeit altijd. De taken zijn verdeeld. Tijger is stuurman en piloot.

Iemand moet de leiding hebben. Dat is altijd Tijger. Tijger die op de kracht van Mels vertrouwt. Mels is matroos en machinist tegelijk. Het roeien gaat hem makkelijk af. Hij hoeft zich nauwelijks in te spannen. Het water in de Wijer staat hoog en stroomt flink, alsof het haast heeft zich onder de brug door te wurmen en uit het dorp weg te komen. De boot gaat als vanzelf.

`Moet je zien hoeveel mensen ons uitzwaaien’, zegt Thija. `Het hele dorp is uitgelopen om afscheid te nemen.’

Ze zijn al bijna bij de brug. Opeens ziet hij Lizet, die haar tong uitsteekt tegen Thija. Haar been dat ze op de reling zet. De kanten strik rond haar dij. De slip die haar billen bijna bloot laat. Thija doet of ze het niet ziet.

Ze glijden onder de brug door. In de geheimzinnige grot onder de brug wordt opeens alles anders. De natte wanden glinsteren groen, om aan te kondigen dat er een wonder staat te gebeuren. In het schemerdonker veranderen hun stemmen en nemen alle dingen andere vormen aan. Als een dartel klein vliegtuig komt de boot onder de overkapping te voorschijn en vliegt omhoog. Een kleine pipercub op weg naar China, die opstijgend onophoudelijk van vorm en kleur verandert.

De mensen juichen. Mels ziet zijn moeder met haar beide handen wuiven, net of ze zelf ook mee wil. Hij zwaait terug.

`Ik breng zijden bloemen voor je mee’, roept hij naar zijn moeder. `En voor jou breng ik een … een …’ roept hij naar zijn vader, die hem in zijn deftigste zwart nawuift. `Een … een …’ probeert hij nog, maar hij weet niet wat hij voor zijn vader mee moet brengen, want ook als hij jarig is, weet hij nooit wat hij voor hem moet kopen.

`We gaan!’ schreeuwt Tijger enthousiast vanuit de cockpit. Hij heeft het nog maar net geroepen, of het vliegtuig klapt tegen de starre, dode muur van de graansilo. Meel stuift in het rond. Alles is wit. De zwaaiende mensen stuiven onder, maar ze blijven doorgaan met zwaaien, alsof ze niet hebben gezien dat het vliegtuig voor hun ogen uit elkaar is gespat. Ze blijven zwaaien tot het allemaal sneeuwpoppen zijn geworden, met zwarte hoeden en verkoolde ogen.

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (081)

wordt vervolgd

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

Nu Mels zelf grootvader is, lijkt het soms of hij zijn leven heeft gedroomd. Net als zijn moeder. Hij weet nog hoe ze zong terwijl ze frambozen plukte. Hij twijfelt aan de waarheid van de dingen die hij zich herinnert. Soms bleken ze achteraf heel anders. Hij herinnerde zich zijn vader als een groot man tegen wie hij opkeek, maar toen hij later in de kast de overjas van zijn vader vond en hem paste, bleek die hem te klein.

En zijn moeder? Was ze echt zo meisjesachtig? Jammer dat hij geen foto’s van haar heeft zoals hij zich haar herinnert, haar mond rood van frambozensap. Alle foto’s die hij van haar heeft zijn in zwart-wit.

En zijn moeder? Was ze echt zo meisjesachtig? Jammer dat hij geen foto’s van haar heeft zoals hij zich haar herinnert, haar mond rood van frambozensap. Alle foto’s die hij van haar heeft zijn in zwart-wit.

Daardoor missen ze ook de geuren die bij haar hoorden. Rijp fruit. Gras. Appelgebak. Hij bewaart een paar foto’s van haar in zijn portefeuille, samen met die van Tijger en Thija. Hij haalt ze te voorschijn, zoals hij bijna elke dag even doet. Zijn moeder, lachend, op het weitje achter het huis waar ze de was te bleken legt, een beetje verrast door de fotograaf. Was dat zijn vader geweest? Of haar eigen vader, grootvader Bernhard?

Een andere foto toont haar op haar paasbest, samen met zijn vader, in het zwart, de voordeur achter zich dichttrekkend. Op weg naar de kerk. In dat grijs is ze veel te deftig voor de moeder uit zijn herinnering. De zondagse kleren zitten haar zelfs op de foto onwennig. Na de mis gooide ze die altijd direct uit, om wat luchtigs aan te trekken, om de bossen in te gaan, samen met Mels en vaak ook met Tijger en Thija. Maar altijd zonder vader. Die zat op zondag in zijn zwarte kleren deftig zondags te wezen in het café.

Of gewoon in de kamer, slapend in zijn stoel. Niet voor niets was hij een zoon van grootvader Rudolf. Hij stond stijf van de regels.

Een foto waar ze allemaal op staan: grootvader Bernhard, moeder, Thija, Tijger en hijzelf. Geen vader. Allemaal tot de knieën in een zee van gras aan de oever van de Wijer. Toen was zijn vader er nog. De foto moet door hem genomen zijn. Hij moet nog hebben geprobeerd de compositie van de foto te redden, maar daarbij heeft hij het hele groepje een beetje scheef gefotografeerd.

Of misschien was hij gewoon dronken, zoals vaak op zondag. De Wijer stroomt in de richting van de brug een beetje omhoog, net alsof ze allemaal wankel staan. Thija staat vooraan, met opgeschorte jurk, bang dat haar onderrok onder het stuifmeel van de oeverlelies komt te zitten. Haar benen dun, maar sterk. Alles aan haar is sterk. Haar lach, haar houding. Hoe klein en spichtig ze ook is, niemand is altijd en overal zo nadrukkelijk aanwezig als zij. Tijger staat naast haar, een arm om haar hals. Hij trekt haar een beetje naar zich toe. Zelf staat Mels vlak bij zijn moeder, die troostend een hand op zijn schouder legt.

Een foto van Tijger alleen, stoer, in starthouding op zijn fiets, als op een motor.

En de adembenemend mooie foto van Thija op de dag van haar plechtige communie. Voor de bloementuin van de kerk. In haar roze jurk, die zelfs op de zwartwitfoto, in de speciale tint grijs, laat zien hoe roze die is. In haar hand draagt ze een boeket van margrieten en Gipskruid, in haar andere hand het nieuwe missaal. Haar ogen staan groot, maar voor haar doen wat verlegen. Ze vertolkt de hoofdrol in een toneelstuk. Het hele dorp was erbij toen alle communicanten, een voor een, door de fotograaf werden gekiekt, allemaal in dezelfde houding, voor de bloementuin tussen de kerk en de pastorie.

Nog altijd herinnert Mels zich dat moment. Hoe stil het werd; het was al stil toen ze naar de plek liep. De ogen waarmee ze naar de fotograaf keek, haar grote wat verbaasde ogen. Het bleef maar duren. Ze trok het toneelstuk helemaal naar zich toe. Maar de fotograaf moest verder. Andere meisjes stonden te dringen.

Mels weet nog precies hoe het was; hoe ze hem heel even aankeek. Maar later zei Tijger dat ze naar hem had gekeken en zo had iedereen gedacht dat ze naar hem of naar haar keek, zelfs zijn moeder.

Hij stopt de foto’s terug in de portefeuille en kijkt uit over de Wijer die er, vanaf dit punt gezien, nog net zo bij ligt als een halve eeuw geleden.

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (080)

wordt vervolgd

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

For the bicentennial of its first publication, Mary Shelley’s original 1818 text, introduced by National Book Critics Circle award-winner Charlotte Gordon. Nominated as one of America’s best-loved novels by PBS’s The Great American Read.

2018 marks the bicentennial of Mary Shelley’s seminal novel. For the first time, Penguin Classics will publish the original 1818 text, which preserves the hard-hitting and politically-charged aspects of Shelley’s original writing, as well as her unflinching wit and strong female voice. This edition also emphasizes Shelley’s relationship with her mother—trailblazing feminist Mary Wollstonecraft, who penned A Vindication of the Rights of Woman—and demonstrates her commitment to carrying forward her mother’s ideals, placing her in the context of a feminist legacy rather than the sole female in the company of male poets, including Percy Shelley and Lord Byron.

2018 marks the bicentennial of Mary Shelley’s seminal novel. For the first time, Penguin Classics will publish the original 1818 text, which preserves the hard-hitting and politically-charged aspects of Shelley’s original writing, as well as her unflinching wit and strong female voice. This edition also emphasizes Shelley’s relationship with her mother—trailblazing feminist Mary Wollstonecraft, who penned A Vindication of the Rights of Woman—and demonstrates her commitment to carrying forward her mother’s ideals, placing her in the context of a feminist legacy rather than the sole female in the company of male poets, including Percy Shelley and Lord Byron.

This edition includes a new introduction and suggestions for further reading by National Book Critics Circle award-winner and Shelley expert Charlotte Gordon, literary excerpts and reviews selected by Gordon, and a chronology and essay by preeminent Shelley scholar Charles E. Robinson.

Mary Shelley: The daughter of Mary Wollestonecraft, the ardent feminist and author of A Vindication on the Right of Women, and William Godwin, the radical-anarchist philosopher and author of Lives of the Necromancers, Mary Goodwin was born into a freethinking, revolutionary household in London on August 30,1797. Educated mainly by her intellectual surroundings, she had little formal schooling and at 16 eloped with the young poet Percy Bysshe Shelley; they eventually married in 1816. Mary Shelley’s life had many tragic elements. Her mother died giving birth to Mary; her half-sister committed suicide; Harriet Shelley (Percy’s wife) drowned herself and her unborn child after he ran off with Mary. William Godwin disowned Mary and Shelley after their elopement, but—heavily in debt—recanted and came to them for money; Mary’s first child died soon after its birth; and in 1822 Percy Shelley drowned in the Gulf of La Spezia—when Mary was not quite 25. Mary Shelley recalled that her husband was “forever inciting” her to “obtain literary reputation.” But she did not begin to write seriously until the summer of 1816, when she and Shelley were in Switzerland, neighbor to Lord Byron. One night following a contest to compose ghost stories, Mary conceived her masterpiece, Frankenstein. After Shelley’s death she continued to write Valperga (1823), The Last Man (1826), Ladore (1835), and Faulkner (1837), in addition to editing her husband’s works. In 1838 she began to work on his biography, but owing to poor health she completed only a fragment. Although she received marriage proposals from Trelawney, John Howard Payne, and perhaps Washington Irving, Mary Shelley never remarried. “I want to be Mary Shelley on my tombstone,” she is reported to have said. She died on February 1, 1851, survived by her son, Percy Florence.

For more than seventy years, Penguin has been the leading publisher of classic literature in the English-speaking world. With more than 1,800 titles, Penguin Classics represents a global bookshelf of the best works throughout history and across genres and disciplines. Readers trust the series to provide authoritative texts enhanced by introductions and notes by distinguished scholars and contemporary authors, as well as up-to-date translations by award-winning translators.

Frankenstein: The 1818 Text

By Mary Shelley

Introduction by Charlotte Gordon

Contribution by Charlotte Gordon

Fiction Classics

Paperback

Penguin Random House

Published by Penguin Classics

Jan 16, 2018

288 Pages

ISBN 9780143131847

$10.00

# new books

Frankenstein – Mary Shelley

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, - Book News, Archive S-T, Art & Literature News, Mary Shelley, Shelley, Mary, Tales of Mystery & Imagination

Literary and music group Feest der Poëzie brings a theatrical lecture on the life and work of Oscar Wilde and one of his favorite beverages – absinthe. This Saturday at the Pianola Museum, 8.30 PM.

Immerse yourself in the story of one of the best-loved writers in the English language with prose, poetry, songs and drama by Oscar Wilde and his contemporaries, on a journey through his rise and fall.

Poet and absintheur David Kwa will demonstrate the absinthe ritual and read manifold roles, such as that of the dreaded Marquess of Queensberry.

Daan van de Velde (piano) and Susanne Winkler (soprano) will perform Irish and English art songs, as performing poet Simon Mulder takes on the roles of narrator and Oscar Wilde (indeed, wearing a contemporary pair of silk breeches) in the fascinating story of his life.

Also, Van de Velde and Mulder will bring the very special performance of a long lost work for piano and voice on Wilde’s ‘Ballad of Reading Gaol’ by early 20th century composer Henri Zagwijn.

The Poetry Bar will bring you carefully prepared absinthe, along with a decadent sonnet.

Saturday the 24th of November 2018

venue open: 8 PM

start: 8.30PM

(English spoken)

venue:

Pianola Museum

Westerstraat 116

Amsterdam

Tickets: € 15/12.50

www.feestderpoezie.nl

trailer: www.youtube.com/watch?v=-V6yx3X8rwg

Music, stories, absinthe and more during ‘The Green Hour’ with Oscar Wilde

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: # Music Archive, Archive M-N, Archive W-X, Art & Literature News, Literary Events, THEATRE, Wilde, Oscar, Wilde, Oscar

Het schuurtje achter het huis van grootvader Rudolf is een klein oorlogsmuseum. Er staan een paar ingevette geweren van Duitsers en Engelsen. Militaire uitrustingen. Helmen. Blinkend opgepoetste koperen hulzen van granaten.

De helm van vliegenier John Wilkington heeft een apart plaatsje onder een glazen stolp. Daarnaast ligt een handgeschreven vel met de informatie die grootvader over het leven van John Wilkington bij elkaar heeft gezocht. En een carbonkopie van de getypte brief die grootvader naar Engeland heeft gestuurd, waarin hij de laatste weken van het leven van Wilkington heeft beschreven.

De helm van vliegenier John Wilkington heeft een apart plaatsje onder een glazen stolp. Daarnaast ligt een handgeschreven vel met de informatie die grootvader over het leven van John Wilkington bij elkaar heeft gezocht. En een carbonkopie van de getypte brief die grootvader naar Engeland heeft gestuurd, waarin hij de laatste weken van het leven van Wilkington heeft beschreven.

Daar heeft hij een dankbrief voor teruggekregen van een majoor Kirk Harlewood, die hem ook het thuisadres van Wilkington heeft gegeven. Waarna zijn schoondochter, Mels’ moeder, bij wie Wilkington in huis was geweest, een brief naar de weduwe heeft gestuurd. Met grootvaders toestemming, omdat hij zelf niet in staat was om emoties op papier te zetten.

Verder bevat het museum veel foto’s in lijstjes. Vooral kiekjes van vrolijke Engelse tommy’s, boven op tanks en in jeeps, met meisjes met opgetrokken rokken op schoot. Door al die vrolijke soldaten en glunderende meisjes lijkt de oorlog vooral op een groot feest.

Bij sommige meisjes heeft grootvader een kruisje op het voorhoofd gezet.

`Waar dient dat kruisje voor?’ vraagt Mels, die de gezichten van de meisjes bestudeert.

`Het is een brandmerk’, zegt grootvader. `Het waren meiden die met Duitse soldaten liepen en later met de tommy’s. Het betekende dat ze voor onze eigen jongens afgeschreven waren. Maar ze trouwden het eerst. Het geheugen van de mensen is kort. De oorlog waren we vlug vergeten.’

`Waarom bewaart u die spullen dan?’

`Omdat ik wil onthouden waar wij angst voor hebben gehad.’

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (079)

wordt vervolgd

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

Mels herinnert zich het gesprek op het kerkhof als de dag van gisteren.

Nog geen twee dagen later vonden ze grootvader Bernhard dood in zijn stoel. Met de kat op schoot, die misschien niet eens wist dat hij dood was of dat misschien niet wilde weten.

Nog geen twee dagen later vonden ze grootvader Bernhard dood in zijn stoel. Met de kat op schoot, die misschien niet eens wist dat hij dood was of dat misschien niet wilde weten.

Hij was zo maar ingeslapen, nog geen uur nadat Mels’ moeder bij hem op bezoek was geweest en zijn bed had opgemaakt met schone lakens.

Misschien vond hij het bed te schoon en te wit om erin te sterven en was hij liever in zijn onopgemaakte holletje doodgegaan.

Grootvader Rudolf heeft hem twintig jaar overleefd. Die is bijna honderd geworden. Hij heeft Bernhard zo lang overleefd dat hij zelfs vergeten was dat hij zijn hele leven ruzie met hem had gemaakt. Toen hij stokoud was, sprak hij alleen nog maar over zijn jeugd, over toen hij en Bernhard nog vrienden waren en alles samen deden en voor eeuwig vrienden wilden zijn. De ouderdom zette in het hoofd van grootvader Rudolf alles op zijn kop.

In het jaar dat hij stierf, was zijn lijf net zo uitgewoond als het grijze kostuum dat hij dertig jaar had gedragen en dat hij nooit meer had willen vervangen, maar in zijn hoofd was hij een jongeman van achttien die de hele wereld aankon. Alles wat er na zijn achttiende gebeurd was, was hij vergeten. De nette man was allang dood. Hij riep naar de meiden op straat en was lastig voor de verpleegsters die hem kwamen wassen en aankleden. Na een lang keurig leven bewees hij in zijn dementie dat hij geen haar was veranderd.

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (078)

wordt vervolgd

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

Kafka’s Other Prague: Writings from the Czechoslovak Republic examines Kafka’s late writings from the perspective of the author’s changing relationship with Czech language, culture, and literature—the least understood facet of his meticulously researched life and work.

Franz Kafka was born in Prague, a bilingual city in the Habsburg Empire. He died a citizen of Czechoslovakia. Yet Kafka was not Czech in any way he himself would have understood. He could speak Czech, but, like many Prague Jews, he was raised and educated and wrote in German. Kafka critics to date have had little to say about the majority language of his native city or its “minor literature,” as he referred to it in a 1913 journal entry. Kafka’s Other Prague explains why Kafka’s later experience of Czech language and culture matters.

Franz Kafka was born in Prague, a bilingual city in the Habsburg Empire. He died a citizen of Czechoslovakia. Yet Kafka was not Czech in any way he himself would have understood. He could speak Czech, but, like many Prague Jews, he was raised and educated and wrote in German. Kafka critics to date have had little to say about the majority language of his native city or its “minor literature,” as he referred to it in a 1913 journal entry. Kafka’s Other Prague explains why Kafka’s later experience of Czech language and culture matters.

Bringing to light newly available archival material, Anne Jamison’s innovative study demonstrates how Czechoslovakia’s founding and Kafka’s own dramatic political, professional, and personal upheavals altered his relationship to this “other Prague.” It destabilized Kafka’s understanding of nationality, language, gender, and sex—and how all these issues related to his own writing.

Kafka’s Other Prague juxtaposes Kafka’s German-language work with Czechoslovak Prague’s language politics, intellectual currents, and print culture—including the influence of his lover and translator, the journalist Milena Jesenská—and shows how this changed cultural and linguistic landscape transformed one of the great literary minds of the last century.

Anne Jamison is an associate professor of English at the University of Utah.

Kafka’s Other Prague

Writings from the Czechoslovak Republic

by Anne Jamison

Publication Date June 2018

Northwestern University Press

Paper Text – $34.95

ISBN 978-0-8101-3720-2

Cloth Text – $99.95

ISBN 978-0-8101-3721-9

Categorie: Literary Criticism

208 pages

# new books

Kafka’s Other Prague

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Book Stories, Archive K-L, Archive K-L, Franz Kafka, Kafka, Franz, Kafka, Franz

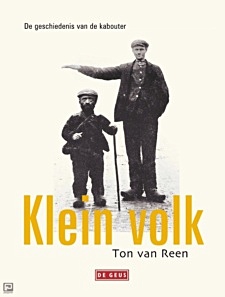

Aanstaande woensdag, 7 november, geeft schrijver Ton van Reen een lezing in de jaarlijkse lezingencyclus van het Dr. Winand Roukens Fonds, aan de Universiteit van Maastricht.

De lezing vindt plaats in de Karl Dittrichzaal van de Universiteit te Maastricht, in het voormalige Bonnefantenklooster, Bonnefantenstraat 2 te Maastricht.

De lezing vindt plaats in de Karl Dittrichzaal van de Universiteit te Maastricht, in het voormalige Bonnefantenklooster, Bonnefantenstraat 2 te Maastricht.

Het thema van de lezingencyclus van het WRF is in dit studiejaar ‘Vreemd in Limburg’.

De eerste lezing werd gehouden door prof. Joep Geraets, hoogleraar genetica en celbiologie over ‘vreemd DNA in Limburg’. De tweede werd gehouden door Dr. Lotte Thissen, cultureel antropoloog, en had als thema de taal waarin wij met elkaar omgaan. De derde lezing is door Ton van Reen. De vierde lezing, over arbeid door buitenlanders zoals Polen, wordt gehouden door Karolina Swoboda, eigenaar van een van de grootste organisaties voor arbeidsbemiddeling in Europa.

In zijn lezing zal Ton van Reen vooral vertellen over de mensen die niet bij ons mochten horen, de vreemdelingen in eigen huis. Omdat ze door de katholieke kerk benoemd waren tot kinderen van de duivel: de kubla walda, de kaboten, de kabouters. In het kort, de door de rk Kerk verstoten kinderen, zoals de kinderen die werden geboren met het syndroom van Down, die volgens de kerk duivelskinderen waren, omdat hun vader de duivel zou zijn en hun moeder omgang had met de duivel.

De rk Kerk heeft altijd de mensen die haar niet goed gezind waren, of van wie ze niet wilden dat ze katholiek werden, in verband gebracht met de duivel, zoals joden, roma en sinti, vrouwen die van hekserij werden beschuldigd, enzovoort.

De rk Kerk heeft altijd de mensen die haar niet goed gezind waren, of van wie ze niet wilden dat ze katholiek werden, in verband gebracht met de duivel, zoals joden, roma en sinti, vrouwen die van hekserij werden beschuldigd, enzovoort.

De duivel zou een geest zijn die zelf niet kon handelen , maar handlangers op aarde nodig had om zijn kwalijke werken uit te voeren, zoals misoogsten, uitbraken van pest en andere plagen, veeziektes , die tot hongersnoden hebben geleid, kinderroof, en zo meer.

Meer dan tien eeuwen lang heeft de kerk de mensen angst aangepraat voor alles wat anders was in de ogen van priesters en voor iedereen die anders dacht of een ander geloof aanhing.

Duizenden mensen, alleen al in het huidige Limburg, waren het slachtoffer van deze vervolgingen door een organisatie die zich boven alles verheven voelde en beschikte over leven en dood.

In de hele wereld werden er miljoenen mensen geslachtofferd en vaak na gruwelijke martelingen vermoord door een organisatie die zegt liefde te prediken maar haat heeft gezaaid en mensen tegen elkaar heeft opgezet.

Aanstaande woensdag, 7 november 2018, lezing van schrijver Ton van Reen in de jaarlijkse lezingencyclus van het Dr. Winand Roukens Fonds, aan de Universiteit van Maastricht.

De lezing vindt plaats in de Karl Dittrichzaal van de Universiteit te Maastricht, in het voormalige Bonnefantenklooster, Bonnefantenstraat 2 te Maastricht. De aanvang is om 16.00 uur. Graag iets eerder aanwezig. Einde om 18.00 uur. Iedereen is welkom.

# lezingen

Ton van Reen

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, - Book Stories, Archive Q-R, Art & Literature News, Literary Events, Reen, Ton van, Reen, Ton van, The Art of Reading, Ton van Reen

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature