Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

Mels is met zijn vader in het café en mag bier tappen omdat de kastelein meedoet met kaarten.

Hij bedient de paar mannen die op het terras zitten.

Mannen van het soort dat hier eerst verdwaald leek, maar van wie hij nu weet dat het wandelaars zijn die de Wijer nalopen. Van de monding van de beek in de rivier terug naar de bron. Ze dragen hoge laarzen om door de broeklanden en rietvelden te stappen.

Mannen van het soort dat hier eerst verdwaald leek, maar van wie hij nu weet dat het wandelaars zijn die de Wijer nalopen. Van de monding van de beek in de rivier terug naar de bron. Ze dragen hoge laarzen om door de broeklanden en rietvelden te stappen.

Over hun rug kijkt hij mee naar de kaart van het riviertje en het opengeslagen boek op tafel. Hij verbaast zich erover dat de Wijer meer dan honderd kilometer lang is en dat de bron ergens ligt bij een dorp dat Weierwiese heet. En dat het officieel geen beek maar een rivier is. En dat er honderdtachtig soorten vis in zitten, terwijl hij er maar tien kent. En dat hij nog nooit een zoetwaterkreeft met schaarvormige kaken heeft gezien. Geen wonder, want volgens het onderschrift bij het plaatje van het dier is het nog geen halve centimeter groot.

De mannen drinken chocomel. De bierdrinkende kerels die zitten te kaarten, lachen hen uit. Mels is boos, vooral over de opmerkingen van meneer Frans-Joseph. Die scheldt de wandelaars uit voor mietjes en hoerenlopers. Het is extra gênant omdat iedereen weet dat hij zelf een hoerenloper is.

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (087)

wordt vervolgd

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

The Match-Maker

The grill-room clock struck eleven with the respectful unobtrusiveness of one whose mission in life is to be ignored. When the flight of time should really have rendered abstinence and migration imperative the lighting apparatus would signal the fact in the usual way.

Six minutes later Clovis approached the supper-table, in the blessed expectancy of one who has dined sketchily and long ago.

Six minutes later Clovis approached the supper-table, in the blessed expectancy of one who has dined sketchily and long ago.

“I’m starving,” he announced, making an effort to sit down gracefully and read the menu at the same time.

“So I gathered;” said his host, “from the fact that you were nearly punctual. I ought to have told you that I’m a Food Reformer. I’ve ordered two bowls of bread-and-milk and some health biscuits. I hope you don’t mind.”

Clovis pretended afterwards that he didn’t go white above the collar-line for the fraction of a second.

“All the same,” he said, “you ought not to joke about such things. There really are such people. I’ve known people who’ve met them. To think of all the adorable things there are to eat in the world, and then to go through life munching sawdust and being proud of it.”

“They’re like the Flagellants of the Middle Ages, who went about mortifying themselves.”

“They had some excuse,” said Clovis. “They did it to save their immortal souls, didn’t they? You needn’t tell me that a man who doesn’t love oysters and asparagus and good wines has got a soul, or a stomach either. He’s simply got the instinct for being unhappy highly developed.”

Clovis relapsed for a few golden moments into tender intimacies with a succession of rapidly disappearing oysters.

“I think oysters are more beautiful than any religion,” he resumed presently. “They not only forgive our unkindness to them; they justify it, they incite us to go on being perfectly horrid to them. Once they arrive at the supper-table they seem to enter thoroughly into the spirit of the thing. There’s nothing in Christianity or Buddhism that quite matches the sympathetic unselfishness of an oyster. Do you like my new waistcoat? I’m wearing it for the first time to-night.”

“It looks like a great many others you’ve had lately, only worse. New dinner waistcoats are becoming a habit with you.”

“They say one always pays for the excesses of one’s youth; mercifully that isn’t true about one’s clothes. My mother is thinking of getting married.”

“Again!”

“It’s the first time.”

“Of course, you ought to know. I was under the impression that she’d been married once or twice at least.”

“Three times, to be mathematically exact. I meant that it was the first time she’d thought about getting married; the other times she did it without thinking. As a matter of fact, it’s really I who am doing the thinking for her in this case. You see, it’s quite two years since her last husband died.”

“You evidently think that brevity is the soul of widowhood.”

“Well, it struck me that she was getting moped, and beginning to settle down, which wouldn’t suit her a bit. The first symptom that I noticed was when she began to complain that we were living beyond our income. All decent people live beyond their incomes nowadays, and those who aren’t respectable live beyond other peoples. A few gifted individuals manage to do both.”

“It’s hardly so much a gift as an industry.”

“The crisis came,” returned Clovis, “when she suddenly started the theory that late hours were bad for one, and wanted me to be in by one o’clock every night. Imagine that sort of thing for me, who was eighteen on my last birthday.”

“On your last two birthdays, to be mathematically exact.”

“Oh, well, that’s not my fault. I’m not going to arrive at nineteen as long as my mother remains at thirty-seven. One must have some regard for appearances.”

“Perhaps your mother would age a little in the process of settling down.”

“That’s the last thing she’d think of. Feminine reformations always start in on the failings of other people. That’s why I was so keen on the husband idea.”

“Did you go as far as to select the gentleman, or did you merely throw out a general idea, and trust to the force of suggestion?”

“If one wants a thing done in a hurry one must see to it oneself. I found a military Johnny hanging round on a loose end at the club, and took him home to lunch once or twice. He’d spent most of his life on the Indian frontier, building roads, and relieving famines and minimizing earthquakes, and all that sort of thing that one does do on frontiers. He could talk sense to a peevish cobra in fifteen native languages, and probably knew what to do if you found a rogue elephant on your croquet-lawn; but he was shy and diffident with women. I told my mother privately that he was an absolute woman-hater; so, of course, she laid herself out to flirt all she knew, which isn’t a little.”

“And was the gentleman responsive?”

“I hear he told some one at the club that he was looking out for a Colonial job, with plenty of hard work, for a young friend of his, so I gather that he has some idea of marrying into the family.”

“You seem destined to be the victim of the reformation, after all.”

Clovis wiped the trace of Turkish coffee and the beginnings of a smile from his lips, and slowly lowered his dexter eyelid. Which, being interpreted, probably meant, “I DON’T think!”

The Match-Maker

From ‘The Chronicles of Clovis’

by Saki (H. H. Munro)

(1870 – 1916)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Saki, Saki, The Art of Reading

THE BOY AND THE BAYONET

It was June, and nearing the closing time of school. The air was full of the sound of bustle and preparation for the final exercises, field day, and drills. Drills especially, for nothing so gladdens the heart of the Washington mother, be she black or white, as seeing her boy in the blue cadet’s uniform, marching proudly to the huzzas of an admiring crowd. Then she forgets the many nights when he has come in tired out and dusty from his practice drill, and feels only the pride and elation of the result.

Although Tom did all he could outside of study hours, there were many days of hard work for Hannah Davis, when her son went into the High School. But she took it upon herself gladly, since it gave Bud the chance to learn, that she wanted him to have. When, however, he entered the Cadet Corps it seemed to her as if the first steps toward the fulfilment of all her hopes had been made. It was a hard pull to her, getting the uniform, but Bud himself helped manfully, and when his mother saw him rigged out in all his regimentals, she felt that she had not toiled in vain. And in fact it was worth all the trouble and expense just to see the joy and pride of “little sister,” who adored Bud.

Although Tom did all he could outside of study hours, there were many days of hard work for Hannah Davis, when her son went into the High School. But she took it upon herself gladly, since it gave Bud the chance to learn, that she wanted him to have. When, however, he entered the Cadet Corps it seemed to her as if the first steps toward the fulfilment of all her hopes had been made. It was a hard pull to her, getting the uniform, but Bud himself helped manfully, and when his mother saw him rigged out in all his regimentals, she felt that she had not toiled in vain. And in fact it was worth all the trouble and expense just to see the joy and pride of “little sister,” who adored Bud.

As the time for the competitive drill drew near there was an air of suppressed excitement about the little house on “D” Street, where the three lived. All day long “little sister,” who was never very well and did not go to school, sat and looked out of the window on the uninteresting prospect of a dusty thoroughfare lined on either side with dull red brick houses, all of the same ugly pattern, interspersed with older, uglier, and viler frame shanties. In the evening Hannah hurried home to get supper against the time when Bud should return, hungry and tired from his drilling, and the chore work which followed hard upon its heels.

Things were all cheerful, however, for as they applied themselves to the supper, the boy, with glowing face, would tell just how his company “A” was getting on, and what they were going to do to companies “B” and “C.” It was not boasting so much as the expression of a confidence, founded upon the hard work he was doing, and Hannah and the “little sister” shared that with him.

The child often, listening to her brother, would clap her hands or cry, “Oh, Bud, you’re just splendid an’ I know you’ll beat ’em.”

“If hard work’ll beat ’em, we’ve got ’em beat,” Bud would reply, and Hannah, to add an admonitory check to her own confidence, would break in with, “Now, don’t you be too sho’, son; dey ain’t been no man so good dat dey wasn’t somebody bettah.” But all the while her face and manner were disputing what her words expressed.

The great day came, and it was a wonderful crowd of people that packed the great baseball grounds to overflowing. It seemed that all of Washington’s coloured population was out, when there were really only about one-tenth of them there. It was an enthusiastic, banner-waving, shouting, hallooing crowd. Its component parts were strictly and frankly partisan, and so separated themselves into sections differentiated by the colours of the flags they carried and the ribbons they wore. Side yelled defiance at side, and party bantered party. Here the blue and white of Company “A” flaunted audaciously on the breeze beside the very seats over which the crimson and gray of “B” were flying, and these in their turn nodded defiance over the imaginary barrier between themselves and “C’s” black and yellow.

The band was thundering out “Sousa’s High School Cadet’s March,” the school officials, the judges, and reporters, and some with less purpose were bustling about, discussing and conferring. Altogether doing nothing much with beautiful unanimity. All was noise, hurry, gaiety, and turbulence. In the midst of it all, with blue and white rosettes pinned on their breasts, sat two spectators, tense and silent, while the breakers of movement and sound struck and broke around them. It meant too much to Hannah and “little sister” for them to laugh and shout. Bud was with Company “A,” and so the whole programme was more like a religious ceremonial to them. The blare of the brass to them might have been the trumpet call to battle in old Judea, and the far-thrown tones of the megaphone the voice of a prophet proclaiming from the hill-top.

Hannah’s face glowed with expectation, and “little sister” sat very still and held her mother’s hand save when amid a burst of cheers Company “A” swept into the parade ground at a quick step, then she sprang up, crying shrilly, “There’s Bud, there’s Bud, I see him,” and then settled back into her seat overcome with embarrassment. The mother’s eyes danced as soon as the sister’s had singled out their dear one from the midst of the blue-coated boys, and it was an effort for her to keep from following her little daughter’s example even to echoing her words.

Company “A” came swinging down the field toward the judges in a manner that called for more enthusiastic huzzas that carried even the Freshman of other commands “off their feet.” They were, indeed, a set of fine-looking young fellows, brisk, straight, and soldierly in bearing. Their captain was proud of them, and his very step showed it. He was like a skilled operator pressing the key of some great mechanism, and at his command they moved like clockwork. Seen from the side it was as if they were all bound together by inflexible iron bars, and as the end man moved all must move with him. The crowd was full of exclamations of praise and admiration, but a tense quiet enveloped them as Company “A” came from columns of four into line for volley firing. This was a real test; it meant not only grace and precision of movement, singleness of attention and steadiness, but quickness tempered by self-control. At the command the volley rang forth like a single shot. This was again the signal for wild cheering and the blue and white streamers kissed the sunlight with swift impulsive kisses. Hannah and Little Sister drew closer together and pressed hands.

The “A” adherents, however, were considerably cooled when the next volley came out, badly scattering, with one shot entirely apart and before the rest. Bud’s mother did not entirely understand the sudden quieting of the adherents; they felt vaguely that all was not as it should be, and the chill of fear laid hold upon their hearts. What if Bud’s company, (it was always Bud’s company to them), what if his company should lose. But, of course, that couldn’t be. Bud himself had said that they would win. Suppose, though, they didn’t; and with these thoughts they were miserable until the cheering again told them that the company had redeemed itself.

Someone behind Hannah said, “They are doing splendidly, they’ll win, they’ll win yet in spite of the second volley.”

Company “A,” in columns of fours, had executed the right oblique in double time, and halted amid cheers; then formed left halt into line without halting. The next movement was one looked forward to with much anxiety on account of its difficulty. The order was marching by fours to fix or unfix bayonets. They were going at a quick step, but the boys’ hands were steady—hope was bright in their hearts. They were doing it rapidly and freely, when suddenly from the ranks there was the bright gleam of steel lower down than it should have been. A gasp broke from the breasts of Company “A’s” friends. The blue and white drooped disconsolately, while a few heartless ones who wore other colours attempted to hiss. Someone had dropped his bayonet. But with muscles unquivering, without a turned head, the company moved on as if nothing had happened, while one of the judges, an army officer, stepped into the wake of the boys and picked up the fallen steel.

No two eyes had seen half so quickly as Hannah and Little Sister’s who the blunderer was. In the whole drill there had been but one figure for them, and that was Bud, Bud, and it was he who had dropped his bayonet. Anxious, nervous with the desire to please them, perhaps with a shade too much of thought of them looking on with their hearts in their eyes, he had fumbled, and lost all that he was striving for. His head went round and round and all seemed black before him.

He executed the movements in a dazed way. The applause, generous and sympathetic, as his company left the parade ground, came to him from afar off, and like a wounded animal he crept away from his comrades, not because their reproaches stung him, for he did not hear them, but because he wanted to think what his mother and “Little Sister” would say, but his misery was as nothing to that of the two who sat up there amid the ranks of the blue and white holding each other’s hands with a despairing grip. To Bud all of the rest of the contest was a horrid nightmare; he hardly knew when the three companies were marched back to receive the judges’ decision. The applause that greeted Company “B” when the blue ribbons were pinned on the members’ coats meant nothing to his ears. He had disgraced himself and his company. What would his mother and his “Little Sister” say?

To Hannah and “Little Sister,” as to Bud, all of the remainder of the drill was a misery. The one interest they had had in it failed, and not even the dropping of his gun by one of Company “E” when on the march, halting in line, could raise their spirits. The little girl tried to be brave, but when it was all over she was glad to hurry out before the crowd got started and to hasten away home. Once there and her tears flowed freely; she hid her face in her mother’s dress, and sobbed as if her heart would break.

“Don’t cry, Baby! don’t cry, Lammie, dis ain’t da las’ time da wah goin’ to be a drill. Bud’ll have a chance anotha time and den he’ll show ’em somethin’; bless you, I spec’ he’ll be a captain.” But this consolation of philosophy was nothing to “Little Sister.” It was so terrible to her, this failure of Bud’s. She couldn’t blame him, she couldn’t blame anyone else, and she had not yet learned to lay all such unfathomed catastrophes at the door of fate. What to her was the thought of another day; what did it matter to her whether he was a captain or a private? She didn’t even know the meaning of the words, but “Little Sister,” from the time she knew Bud was a private, knew that that was much better than being captain or any of those other things with a long name, so that settled it.

Her mother finally set about getting the supper, while “Little Sister” drooped disconsolately in her own little splint-bottomed chair. She sat there weeping silently until she heard the sound of Bud’s step, then she sprang up and ran away to hide. She didn’t dare to face him with tears in her eyes. Bud came in without a word and sat down in the dark front room.

“Dat you, Bud?” asked his mother.

“Yassum.”

“Bettah come now, supper’s puty ‘nigh ready.”

“I don’ want no supper.”

“You bettah come on, Bud, I reckon you mighty tired.”

He did not reply, but just then a pair of thin arms were put around his neck and a soft cheek was placed close to his own.

“Come on, Buddie,” whispered “Little Sister,” “Mammy an’ me know you didn’t mean to do it, an’ we don’ keer.”

Bud threw his arms around his little sister and held her tightly.

“It’s only you an’ ma I care about,” he said, “though I am sorry I spoiled the company’s drill; they say “B” would have won anyway on account of our bad firing, but I did want you and ma to be proud.”

“We is proud,” she whispered, “we’s mos’ prouder dan if you’d won,” and pretty soon she led him by the hand out to supper.

Hannah did all she could to cheer the boy and to encourage him to hope for next year, but he had little to say in reply, and went to bed early.

In the morning, though it neared school time, Bud lingered around and seemed in no disposition to get ready to go.

“Bettah git ready fer school,” said Hannah cheerily to him.

“I don’t believe I want to go any more,” Bud replied.

“Not go any more? Why ain’t you shamed to talk that way! O’ cose you a goin’ to school.”

“I’m ashamed to show my face to the boys.”

“What you say about de boys? De boys ain’t a-goin’ to give you no edgication when you need it.”

“Oh, I don’t want to go, ma; you don’t know how I feel.”

“I’m kinder sorry I let you go into dat company,” said Hannah musingly; “’cause it was de teachin’ I wanted you to git, not de prancin’ and steppin’; but I did t’ink it would make mo’ of a man of you, an’ it ain’t. Yo’ pappy was a po’ man, ha’d wo’kin’, an’ he wasn’t high-toned neither, but from the time I first see him to the day of his death I nevah seen him back down because he was afeared of anything,” and Hannah turned to her work.

“Little Sister” went up to Bud and slipped her hand in his. “You ain’t a-goin’ to back down, is you, Buddie?” she said.

“No,” said Bud stoutly, as he braced his shoulders, “I’m a-goin’.”

But no persuasion could make him wear his uniform.

The boys were a little cold to him, and some were brutal. But most of them recognised the fact that what had happened to Tom Harris might have happened to any one of them. Besides, since the percentage had been shown, it was found that “B” had outpointed them in many ways, and so their loss was not due to the one grave error. Bud’s heart sank when he dropped into his seat in the Assembly Hall to find seated on the platform one of the blue-coated officers who had acted as judge the day before. After the opening exercises were over he was called upon to address the school. He spoke readily and pleasantly, laying especial stress upon the value of discipline; toward the end of his address he said: “I suppose Company ‘A’ is heaping accusations upon the head of the young man who dropped his bayonet yesterday.” Tom could have died. “It was most regrettable,” the officer continued, “but to me the most significant thing at the drill was the conduct of that cadet afterward. I saw the whole proceeding; I saw that he did not pause for an instant, that he did not even turn his head, and it appeared to me as one of the finest bits of self-control I had ever seen in any youth; had he forgotten himself for a moment and stopped, however quickly, to secure the weapon, the next line would have been interfered with and your whole movement thrown into confusion.” There were a half hundred eyes glancing furtively at Bud, and the light began to dawn in his face. “This boy has shown what discipline means, and I for one want to shake hands with him, if he is here.”

When he had concluded the Principal called Bud forward, and the boys, even his detractors, cheered as the officer took his hand.

“Why are you not in uniform, sir?” he asked.

“I was ashamed to wear it after yesterday,” was the reply.

“Don’t be ashamed to wear your uniform,” the officer said to him, and Bud could have fallen on his knees and thanked him.

There were no more jeers from his comrades now, and when he related it all at home that evening there were two more happy hearts in that South Washington cottage.

“I told you we was more prouder dan if you’d won,” said “Little Sister.”

“An’ what did I tell you ’bout backin’ out?” asked his mother.

Bud was too happy and too busy to answer; he was brushing his uniform.

Paul Laurence Dunbar

(1872 – 1906)

The Boy and The Bayonet

From The Heart Of Happy Hollow, a collection of short stories reprinted in 1904 by Dodd, Mead and Company, New York.

Short Story

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Archive C-D, Dunbar, Paul Laurence, Dunbar, Paul Laurence, Paul Laurence Dunbar, Paul Laurence Dunbar

Een tik op zijn schouder. Hij trekt de plaid van zijn gezicht en opent zijn ogen. Het is Afke.

`Je was tegen iemand aan het praten.’

`Ik praatte met Tijger en Thija.’

`Over school?’

`Goh, dat ik zo duidelijk praat als ik droom.’

Ze helpt hem van het bed in zijn stoel. Ze helpt hem vaak. Tegenover haar voelt hij niet de gêne die hij wel voelt bij zijn vrouw en zijn dochter. Soms is ook Zhia erbij. Dan helpen ze hem als twee jonge verpleegsters.

Zijn vrouw haat het als de meisjes boven zijn, al weet hij niet waarom.

`Je bent nat van het zweet.’

`Je bent nat van het zweet.’

`Dat komt door de medicijnen. Ik zweet nog als het vriest.’

Ze trekt zijn overhemd uit.

`De haren op je rug zijn nog zwart.’ Ze droogt zijn rug en hals. `Had je vroeger zwart haar? Vonden de meisjes je knap?’

`Er waren hier niet zo veel meisjes. Het dorp was nog klein.’

`En die paar dan?’

`Thija vond me knap. Maar ik denk dat ze Tijger knapper vond.’

`En oma?’

`Toen zij een meisje was? Ze wilde me alleen hebben omdat ze jaloers was op Thija. Dat denk ik nu.’

`Vond jij haar knap?’

`Anders.’

`Je was toch wel verliefd op haar? Je bent toch met haar getrouwd?’

`Het liep nu eenmaal zo. Er waren hier maar een paar meisjes, dat zei ik toch. Kemp wilde haar ook.’

`Ben je met haar getrouwd omdat je haar niet aan Kemp gunde?’

`Ja.’ Tegen haar kan hij alleen maar eerlijk zijn.

`Wel vreemd’, zegt ze. `Nu heb ik precies zulke grootvaders zoals jij had.’

`Hoezo?’

`Jij zegt toch altijd dat ze elkaar niet mochten.’

Ze rijdt hem voor de wastafel.

`Moet ik je scheren?’

`Ik doe het zelf.’

Ze pakt het mes uit de la, haalt het uit de houder en pakt kwast en scheerzeep uit de kast.

`Scheerzeep ruikt lekker.’

`Het ruikt naar jongens.’

`Jongens! Was je gelukkig als kind?’

`Alleen toen Tijger en Thija er nog waren.’

`Er waren toch ook anderen die van je hielden.’

`Wie dan?’

`Je moeder.’

`Dat is ook zo.’

`Ik hou ook van je.’

Hij ziet haar oprechte gezicht in de spiegel.

`Het is waar’, zegt hij. `Jij houdt net zo veel van mij als ik van jou. En je opa Kemp?’

`Van hem hou ik ook. Anders. Zal ik je inzepen?’ Ze haalt de kwast door het schuim en zeept hem zorgvuldig in. `Ik kan je ook scheren. Laat mij het maar doen. Jij snijdt je te vaak.’

`Ik heb een zware baard. Een scheerapparaat werkt niet bij mij.’

`Voortaan scheer ik je wel.’ Ze zet het mes aan. Protesteren helpt niet. Hij voelt hoe zacht het mes over zijn huid glijdt. In de spiegel ziet hij de inspanning op haar gezicht. Hij blijft muisstil zitten. Ze wil het beter doen dan hij.

Terwijl ze met hem bezig is, hoort hij een zacht gebrom, door de muur heen. Net alsof in het buurhuis een of ander apparaat aanstaat. Hij spant zich in om het geluid te kunnen traceren. Het kan ook een vliegtuig zijn, ver weg.

`Klaar’, zegt ze triomfantelijk en ze bet zijn gezicht. `Geen bloed. Zie je dat ik het beter kan.’

`Mooi. Je moet verpleegster worden.’

`Later ga ik met dieren werken. In een circus. Of bij een dierenarts. Of in een asiel. Zhia wordt verpleegster. Of dokter. Ze wil naar Afrika. Of in een kindertehuis.’

`Dat jullie al zo goed weten wat je wilt! Toen ik twaalf was, wist ik nog niets.’

Hij hoort de voordeur dichtslaan.

`Kan ik boven komen?’

`Kom maar’, roept Afke.

Zhia holt de trap op en komt de kamer binnen.

`Bij de silo is een ongeluk gebeurd’, hijgt Zhia.

`Ernstig?’ schrikt Mels.

`Een witte muis is van het dak gevallen. Recht in de bek van een buizerd.’

`Dat is dubbele pech’, zegt Mels.

`Of dubbel geluk’, zegt Zhia. `Misschien was de muis blij dat ze werd opgevreten en dat ze niet te pletter viel.’

`Van dat laatste had ze niets gevoeld’, zegt Mels. `Maar zo’n roofvogel die je verslindt, dat is wel erg.’

`Het is niet waar’, zegt Zhia. `Het was geen witte muis, het was een zwarte.’

Afke trekt hem een overhemd aan en maakt de knoopjes dicht.

`We moeten naar school. Na het avondeten kom ik weer, als je zin hebt in vertellen.’

`Daar heb ik altijd zin in.’

Hij hoort hen de trap af lopen. De deur valt dicht.

Ze hollen weg. Hij luistert tot hij niets meer hoort in de straat. Hij weet weer voor wie hij leeft.

Hij rolt naar de kast en pakt het boek. Elke dag kijkt hij er even in. Het boek dat Thija aan Tijger heeft gegeven toen hij twaalf werd, maar dat hij niet wilde. `Chine, pays inconnu.’ `Les couleurs pastel de la Chine’, leest hij onder een foto van een rivier van blauw krijt. De oevers zijn van pastelkleurig paars, de lucht is blauw en vet van de regen en gepokt met zwarte ganzen die zich op het water laten vallen. Boten met rieten daken, met naakte jongens voorop die met een stok de diepte peilen, drijven op het water.

De foto van een riviertje van blauw porselein, en een man in een bootje van bamboe, omringd door groenten met de kleur van gras. `Un homme transporte des légumes’.

Hij zet het boek terug, rolt naar het bureau en opent het album met de levenslopen van de directeuren van de fabriek. Hun levensbeschrijvingen, hun foto’s en doodsprentjes. Hij is bezig ze te ordenen, er een lijn in te krijgen.

Een grote leugen is het doodsprentje van Frans-Joseph Hubben, waarop te lezen staat dat hij zijn leven lang gehoorzaam aan God is geweest en een goed en trouw echtgenoot en vader was. Mels weet beter. Meneer Frans-Joseph kwam zelden in de kerk. Vlak na de verkoop van de fabriek is hij in Zwitserland gestorven aan een hartaanval, naar men zegt nadat ze hem uit een café hadden gezet waar hij vrouwen lastigviel.

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (086)

wordt vervolgd

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

Christian Kunda Mutoki porte un nouveau regard sur Le Horla de Guy de Maupassant.

Il est précédé d’une préface et suivi d’une postface.

Il est précédé d’une préface et suivi d’une postface.

Il vient rafraîchir les problématiques qui touchent à la morale, à l’athéisme, à des amours tumultueuses et infidèles. . .

Le monde d’aujourd’hui diffère-t-il de celui décrit au XIXe siècle par l’écrivain français ? La science a-t-elle amélioré la condition existentielle de l’homme ?

Voici quelques questions majeures qui trouvent ici un regard neuf.

Christian Kunda Mutoki a préparé sa thèse de doctorat à l’Université Paul Verlaine, actuelle Université de la Lorraine (Metz, France). Il est écrivain et professeur de Littérature et civilisation françaises à l’Université de Lubumbashi, en RDC.

GUY DE MAUPASSANT

Une certaine idée de l’homme dans Le Horla

Christian Kunda Mutoki

Cahiers des sciences du langage

Langue Linguistique Littérature

Broché

Format : 15,5 x 24 cm

ISBN : 978-2-8066-3665-2

14 décembre 2018

70 pages

€ 11,5

# New books

Une certaine idée de l’homme dans Le Horla

de Guy de Maupassant

Christian Kunda Mutoki

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive M-N, Archive M-N, Art & Literature News, Guy de Maupassant, Maupassant, Guy de, Maupassant, Guy de

THE RACE QUESTION

Scene—Race track. Enter old coloured man, seating himself.

“Oomph, oomph. De work of de devil sho’ do p’ospah. How ‘do, suh? Des tol’able, thankee, suh. How you come on? Oh, I was des a-sayin’ how de wo’k of de ol’ boy do p’ospah. Doesn’t I frequent the racetrack? No, suh; no, suh. I’s Baptis’ myse’f, an’ I ‘low hit’s all devil’s doin’s. Wouldn’t ‘a’ be’n hyeah to-day, but I got a boy named Jim dat’s long gone in sin an’ he gwine ride one dem hosses. Oomph, dat boy! I sut’ny has talked to him and labohed wid him night an’ day, but it was allers in vain, an’ I’s feahed dat de day of his reckonin’ is at han’.

“Ain’t I nevah been intrusted in racin’? Humph, you don’t s’pose I been dead all my life, does you? What you laffin’ at? Oh, scuse me, scuse me, you unnerstan’ what I means. You don’ give a ol’ man time to splain hisse’f. What I means is dat dey has been days when I walked in de counsels of de on-gawdly and set in de seats of sinnahs; and long erbout dem times I did tek most ovahly strong to racin’.

“Ain’t I nevah been intrusted in racin’? Humph, you don’t s’pose I been dead all my life, does you? What you laffin’ at? Oh, scuse me, scuse me, you unnerstan’ what I means. You don’ give a ol’ man time to splain hisse’f. What I means is dat dey has been days when I walked in de counsels of de on-gawdly and set in de seats of sinnahs; and long erbout dem times I did tek most ovahly strong to racin’.

“How long dat been? Oh, dat’s way long back, ‘fo’ I got religion, mo’n thuty years ago, dough I got to own I has fell from grace several times sense.

“Yes, suh, I ust to ride. Ki-yi! I nevah furgit de day dat my ol’ Mas’ Jack put me on ‘June Boy,’ his black geldin’, an’ say to me, ‘Si,’ says he, ‘if you don’ ride de tail offen Cunnel Scott’s mare, “No Quit,” I’s gwine to larrup you twell you cain’t set in de saddle no mo’.’ Hyah, hyah. My ol’ Mas’ was a mighty han’ fu’ a joke. I knowed he wan’t gwine to do nuffin’ to me.

“Did I win? Why, whut you spec’ I’s doin’ hyeah ef I hadn’ winned? W’y, ef I’d ‘a’ let dat Scott maih beat my ‘June Boy’ I’d ‘a’ drowned myse’f in Bull Skin Crick.

“Yes, suh, I winned; w’y, at de finish I come down dat track lak hit was de Jedgment Day an’ I was de las’ one up! Ef I didn’t race dat maih’s tail clean off, I ‘low I made hit do a lot o’ switchin’. An’ aftah dat my wife Mandy she ma’ed me. Hyah, hyah, I ain’t bin much on hol’in’ de reins sence.

“Sh! dey comin’ in to wa’m up. Dat Jim, dat Jim, dat my boy; you nasty putrid little rascal. Des a hundred an’ eight, suh, des a hundred an’ eight. Yas, suh, dat’s my Jim; I don’t know whaih he gits his dev’ment at.

“What’s de mattah wid dat boy? Whyn’t he hunch hisse’f up on dat saddle right? Jim, Jim, whyn’t you limber up, boy; hunch yo’se’f up on dat hoss lak you belonged to him and knowed you was dah. What I done showed you? De black raskil, goin’ out dah tryin’ to disgrace his own daddy. Hyeah he come back. Dat’s bettah, you scoun’ril.

“Dat’s a right smaht-lookin’ hoss he’s a-ridin’, but I ain’t a-trustin’ dat bay wid de white feet—dat is, not altogethah. She’s a favourwright too; but dey’s sumpin’ else in dis worl’ sides playin’ favourwrights. Jim bettah had win dis race. His hoss ain’t a five to one shot, but I spec’s to go way fum hyeah wid money ernuff to mek a donation on de pa’sonage.

“Does I bet? Well, I don’ des call hit bettin’; but I resks a little w’en I t’inks I kin he’p de cause. ‘Tain’t gamblin’, o’ co’se; I wouldn’t gamble fu nothin’, dough my ol’ Mastah did ust to say dat a honest gamblah was ez good ez a hones’ preachah an’ mos’ nigh ez skace.

“Look out dah, man, dey’s off, dat nasty bay maih wid de white feet leadin’ right fu’m ‘de pos’. I knowed it! I knowed it! I had my eye on huh all de time. Oh, Jim, Jim, why didn’t you git in bettah, way back dah fouf? Dah go de gong! I knowed dat wasn’t no staht. Troop back dah, you raskils, hyah, hyah.

“I wush dat boy wouldn’t do so much jummying erroun’ wid dat hoss. Fust t’ing he know he ain’t gwine to know whaih he’s at.

“Dah, dah dey go ag’in. Hit’s a sho’ t’ing dis time. Bettah, Jim, bettah. Dey didn’t leave you dis time. Hug dat bay mare, hug her close, boy. Don’t press dat hoss yit. He holdin’ back a lot o’ t’ings.

“He’s gainin’! doggone my cats, he’s gainin’! an’ dat hoss o’ his’n gwine des ez stiddy ez a rockin’-chair. Jim allus was a good boy.

“Confound these spec’s, I cain’t see ’em skacely; huh, you say dey’s neck an’ neck; now I see ’em! now I see ’em! and Jimmy’s a-ridin’ like——Huh, huh, I laik to said sumpin’.

“De bay maih’s done huh bes’, she’s done huh bes’! Dey’s turned into the stretch an’ still see-sawin’. Let him out, Jimmy, let him out! Dat boy done th’owed de reins away. Come on, Jimmy, come on! He’s leadin’ by a nose. Come on, I tell you, you black rapscallion, come on! Give ’em hell, Jimmy! give ’em hell! Under de wire an’ a len’th ahead. Doggone my cats! wake me up w’en dat othah hoss comes in.

“No, suh, I ain’t gwine stay no longah, I don’t app’ove o’ racin’, I’s gwine ‘roun’ an’ see dis hyeah bookmakah an’ den I’s gwine dreckly home, suh, dreckly home. I’s Baptis’ myse’f, an’ I don’t app’ove o’ no sich doin’s!”

Paul Laurence Dunbar

(1872 – 1906)

The Race Question

From The Heart Of Happy Hollow, a collection of short stories reprinted in 1904 by Dodd, Mead and Company, New York.

Short story

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: *Archive African American Literature, Archive C-D, Archive C-D, Dunbar, Paul Laurence, Dunbar, Paul Laurence, Paul Laurence Dunbar, Paul Laurence Dunbar

The Blind Spot

“You’ve just come back from Adelaide’s funeral, haven’t you?” said Sir Lulworth to his nephew; “I suppose it was very like most other funerals?”

“I’ll tell you all about it at lunch,” said Egbert.

“You’ll do nothing of the sort. It wouldn’t be respectful either to your great-aunt’s memory or to the lunch. We begin with Spanish olives, then a borshch, then more olives and a bird of some kind, and a rather enticing Rhenish wine, not at all expensive as wines go in this country, but still quite laudable in its way. Now there’s absolutely nothing in that menu that harmonises in the least with the subject of your great-aunt Adelaide or her funeral. She was a charming woman, and quite as intelligent as she had any need to be, but somehow she always reminded me of an English cook’s idea of a Madras curry.”

“You’ll do nothing of the sort. It wouldn’t be respectful either to your great-aunt’s memory or to the lunch. We begin with Spanish olives, then a borshch, then more olives and a bird of some kind, and a rather enticing Rhenish wine, not at all expensive as wines go in this country, but still quite laudable in its way. Now there’s absolutely nothing in that menu that harmonises in the least with the subject of your great-aunt Adelaide or her funeral. She was a charming woman, and quite as intelligent as she had any need to be, but somehow she always reminded me of an English cook’s idea of a Madras curry.”

“She used to say you were frivolous,” said Egbert. Something in his tone suggested that he rather endorsed the verdict.

“I believe I once considerably scandalised her by declaring that clear soup was a more important factor in life than a clear conscience. She had very little sense of proportion. By the way, she made you her principal heir, didn’t she?”

“Yes,” said Egbert, “and executor as well. It’s in that connection that I particularly want to speak to you.”

“Business is not my strong point at any time,” said Sir Lulworth, “and certainly not when we’re on the immediate threshold of lunch.”

“It isn’t exactly business,” explained Egbert, as he followed his uncle into the dining-room.

“It’s something rather serious. Very serious.”

“Then we can’t possibly speak about it now,” said Sir Lulworth; “no one could talk seriously during a borshch. A beautifully constructed borshch, such as you are going to experience presently, ought not only to banish conversation but almost to annihilate thought. Later on, when we arrive at the second stage of olives, I shall be quite ready to discuss that new book on Borrow, or, if you prefer it, the present situation in the Grand Duchy of Luxemburg. But I absolutely decline to talk anything approaching business till we have finished with the bird.”

For the greater part of the meal Egbert sat in an abstracted silence, the silence of a man whose mind is focussed on one topic. When the coffee stage had been reached he launched himself suddenly athwart his uncle’s reminiscences of the Court of Luxemburg.

“I think I told you that great-aunt Adelaide had made me her executor. There wasn’t very much to be done in the way of legal matters, but I had to go through her papers.”

“That would be a fairly heavy task in itself. I should imagine there were reams of family letters.”

“Stacks of them, and most of them highly uninteresting. There was one packet, however, which I thought might repay a careful perusal. It was a bundle of correspondence from her brother Peter.”

“The Canon of tragic memory,” said Lulworth.

“Exactly, of tragic memory, as you say; a tragedy that has never been fathomed.”

“Probably the simplest explanation was the correct one,” said Sir Lulworth; “he slipped on the stone staircase and fractured his skull in falling.”

Egbert shook his head. “The medical evidence all went to prove that the blow on the head was struck by some one coming up behind him. A wound caused by violent contact with the steps could not possibly have been inflicted at that angle of the skull. They experimented with a dummy figure falling in every conceivable position.”

“But the motive?” exclaimed Sir Lulworth; “no one had any interest in doing away with him, and the number of people who destroy Canons of the Established Church for the mere fun of killing must be extremely limited. Of course there are individuals of weak mental balance who do that sort of thing, but they seldom conceal their handiwork; they are more generally inclined to parade it.”

“His cook was under suspicion,” said Egbert shortly.

“I know he was,” said Sir Lulworth, “simply because he was about the only person on the premises at the time of the tragedy. But could anything be sillier than trying to fasten a charge of murder on to Sebastien? He had nothing to gain, in fact, a good deal to lose, from the death of his employer. The Canon was paying him quite as good wages as I was able to offer him when I took him over into my service. I have since raised them to something a little more in accordance with his real worth, but at the time he was glad to find a new place without troubling about an increase of wages. People were fighting rather shy of him, and he had no friends in this country. No; if anyone in the world was interested in the prolonged life and unimpaired digestion of the Canon it would certainly be Sebastien.”

“People don’t always weigh the consequences of their rash acts,” said Egbert, “otherwise there would be very few murders committed. Sebastien is a man of hot temper.”

“He is a southerner,” admitted Sir Lulworth; “to be geographically exact I believe he hails from the French slopes of the Pyrenees. I took that into consideration when he nearly killed the gardener’s boy the other day for bringing him a spurious substitute for sorrel. One must always make allowances for origin and locality and early environment; ‘Tell me your longitude and I’ll know what latitude to allow you,’ is my motto.”

“There, you see,” said Egbert, “he nearly killed the gardener’s boy.”

“My dear Egbert, between nearly killing a gardener’s boy and altogether killing a Canon there is a wide difference. No doubt you have often felt a temporary desire to kill a gardener’s boy; you have never given way to it, and I respect you for your self-control. But I don’t suppose you have ever wanted to kill an octogenarian Canon. Besides, as far as we know, there had never been any quarrel or disagreement between the two men. The evidence at the inquest brought that out very clearly.”

“Ah!” said Egbert, with the air of a man coming at last into a deferred inheritance of conversational importance, “that is precisely what I want to speak to you about.”

He pushed away his coffee cup and drew a pocket-book from his inner breast-pocket. From the depths of the pocket-book he produced an envelope, and from the envelope he extracted a letter, closely written in a small, neat handwriting.

“One of the Canon’s numerous letters to Aunt Adelaide,” he explained, “written a few days before his death. Her memory was already failing when she received it, and I daresay she forgot the contents as soon as she had read it; otherwise, in the light of what subsequently happened, we should have heard something of this letter before now. If it had been produced at the inquest I fancy it would have made some difference in the course of affairs. The evidence, as you remarked just now, choked off suspicion against Sebastien by disclosing an utter absence of anything that could be considered a motive or provocation for the crime, if crime there was.”

“Oh, read the letter,” said Sir Lulworth impatiently.

“It’s a long rambling affair, like most of his letters in his later years,” said Egbert. “I’ll read the part that bears immediately on the mystery.

“‘I very much fear I shall have to get rid of Sebastien. He cooks divinely, but he has the temper of a fiend or an anthropoid ape, and I am really in bodily fear of him. We had a dispute the other day as to the correct sort of lunch to be served on Ash Wednesday, and I got so irritated and annoyed at his conceit and obstinacy that at last I threw a cupful of coffee in his face and called him at the same time an impudent jackanapes. Very little of the coffee went actually in his face, but I have never seen a human being show such deplorable lack of self-control. I laughed at the threat of killing me that he spluttered out in his rage, and thought the whole thing would blow over, but I have several times since caught him scowling and muttering in a highly unpleasant fashion, and lately I have fancied that he was dogging my footsteps about the grounds, particularly when I walk of an evening in the Italian Garden.’

“It was on the steps in the Italian Garden that the body was found,” commented Egbert, and resumed reading.

“‘I daresay the danger is imaginary; but I shall feel more at ease when he has quitted my service.’”

Egbert paused for a moment at the conclusion of the extract; then, as his uncle made no remark, he added: “If lack of motive was the only factor that saved Sebastien from prosecution I fancy this letter will put a different complexion on matters.”

“Have you shown it to anyone else?” asked Sir Lulworth, reaching out his hand for the incriminating piece of paper.

“No,” said Egbert, handing it across the table, “I thought I would tell you about it first. Heavens, what are you doing?”

Egbert’s voice rose almost to a scream. Sir Lulworth had flung the paper well and truly into the glowing centre of the grate. The small, neat handwriting shrivelled into black flaky nothingness.

“What on earth did you do that for?” gasped Egbert. “That letter was our one piece of evidence to connect Sebastien with the crime.”

“That is why I destroyed it,” said Sir Lulworth.

“But why should you want to shield him?” cried Egbert; “the man is a common murderer.”

“A common murderer, possibly, but a very uncommon cook.”

The Blind Spot

From ‘Beasts and Super-Beasts’

by Saki (H. H. Munro)

(1870 – 1916)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Saki, Saki, The Art of Reading

`Als we China hebben gezien, zullen we pas begrijpen hoe nietig het hier allemaal is’, zegt Tijger.

`Hoe klein het dorp is, hoe smal de beek, hoe de fabriek stinkt.’

`Hoe klein het dorp is, hoe smal de beek, hoe de fabriek stinkt.’

`Jij hoeft helemaal niet op reis te gaan om dat te ontdekken’, zegt Thija. `Jij weet het nu al.’

`Na de zomervakantie gaan we ieder naar een andere school’, zegt Tijger.

`Het is ellendig’, zegt Mels. `Ik wil helemaal niet naar een andere school. We moeten bij elkaar blijven.’

`We hebben er niets over te zeggen’, zegt Tijger. `Het is allemaal al beslist.’

`Stom’, zegt Thija. `Ik zal jullie maanden niet zien.’

`Dat is het ergst van alles,’ zegt Mels, `dat jij naar kostschool moet.’

`Ik wil het niet. Mijn váder wil het.’

`Ons vragen ze niets’, zegt Mels.

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (085)

wordt vervolgd

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

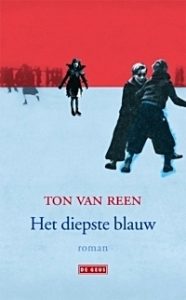

“And I? May I say nothing, my lord?” With these words, Oscar Wilde’s courtroom trials came to a close. The lord in question, High Court justice Sir Alfred Wills, sent Wilde to the cells, sentenced to two years in prison with hard labor for the crime of “gross indecency” with other men.

As cries of “shame” emanated from the gallery, the convicted aesthete was roundly silenced.

As cries of “shame” emanated from the gallery, the convicted aesthete was roundly silenced.

But he did not remain so. Behind bars and in the period immediately after his release, Wilde wrote two of his most powerful works—the long autobiographical letter De Profundis and an expansive best-selling poem, The Ballad of Reading Gaol.

In The Annotated Prison Writings of Oscar Wilde, Nicholas Frankel collects these and other prison writings, accompanied by historical illustrations and his rich facing-page annotations. As Frankel shows, Wilde experienced prison conditions designed to break even the toughest spirit, and yet his writings from this period display an imaginative and verbal brilliance left largely intact.

Wilde also remained politically steadfast, determined that his writings should inspire improvements to Victorian England’s grotesque regimes of punishment. But while his reformist impulse spoke to his moment, Wilde also wrote for eternity.

At once a savage indictment of the society that jailed him and a moving testimony to private sufferings, Wilde’s prison writings—illuminated by Frankel’s extensive notes—reveal a very different man from the famous dandy and aesthete who shocked and amused the English-speaking world.

Nicholas Frankel is Professor of English at Virginia Commonwealth University.

“Frankel provides a valuable service in comprehensively editing these works for a fresh generation of readers.” — Joseph Bristow, University of California, Los Angeles

The Annotated Prison Writings of Oscar Wilde

Oscar Wilde

Edited by Nicholas Frankel

Harvard University Press

Paperback

408 pages

Publication: May 2018

ISBN 9780674984387

€17.00

# more books

The Annotated Prison Writings of Oscar Wilde

-Clemency Petition to the Home Secretary, 2 July 1896

-De Profundis

-Letter to the Daily Chronicle, 27 May 1897

-The Ballad of Reading Gaol

-Letter to the Daily Chronicle, 23 March 1898

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Book Stories, Archive W-X, Archive W-X, Art & Literature News, CRIME & PUNISHMENT, REPRESSION OF WRITERS, JOURNALISTS & ARTISTS, Wilde, Oscar, Wilde, Oscar

Hij heeft geen idee waar Jacob begraven is. Toen heeft hij er niet naar gevraagd.

Hebben ze met z’n drieën nooit bloemen willen brengen naar zijn graf? Hij weet het niet meer. Er was te veel afstand tussen de zigeuners en de dorpelingen. Ze werden gedoogd, daar hield het mee op. Je ging er niet mee om. Dat wilden ze zelf waarschijnlijk ook niet. Ze bleven onder elkaar.

Hij rijdt door naar huis. Het is bijna twaalf uur.

Met moeite kan hij bij de bel.

Lizet doet open.

Lizet doet open.

`Dat werd tijd. Ik zit op je te wachten.’

`Het is nog geen twaalf uur.’

`Ik wil de boel aan kant hebben. Hoe was het?’

`Geen mens. Jij niet. Niemand.’

Over die hoerenmadam praat hij niet.

Hij rijdt door naar de keuken. De tafel is gedekt. In een hoek staat de kinderwagen. De baby van zijn dochter slaapt. De kat ligt in het mandje onder in de wagen.

Lizet legt een beboterde snee brood op zijn bord en doet er een omelet op.

Hij neemt een hap. Het ei is koud. Hij schuift het bord terug.

`Is het niet goed?’

`Het smaakt niet als het koud is.’

Buiten slaat de torenklok twaalf uur. Hij rolt zijn stoel terug.

`Eet je niet?’

`Nee.’

`Doe ik daar al die moeite voor?’

`Vanochtend gooide je mijn koffie weg. Nu is het ei koud.’

`Je was beter af in dat revalidatiecentrum’, gooit ze eruit.

`Ik ben blij dat je het gezegd hebt.’

`Zo bedoel ik het niet.’

`Je krijgt je zin.’

`Dram niet zo door.’

`Ik geef je gelijk.’

Ze weet dat ze te ver is gegaan. Nu heeft hij haar in de tang, ook al is het maar voor een paar tellen.

Met de lift gaat hij naar boven. Hij kijkt niet naar de schilderijen van de Wijer bij de trap. Hij wil niets zien.

Als hij van buiten komt, ziet hij elke keer hoe klein zijn kamer is. Ze lijkt steeds kleiner te worden. Een cel. Hij wil hier weg.

Hij kijkt niet in de spiegel. Hij wil zijn kwade hoofd niet zien.

Zijn bed is niet opgemaakt. Hij sluit zijn ogen en houdt de handen voor zijn oren, om de woede in hem te bedaren. Hij moet rustig worden. Aanvallen van woede kunnen het tekort aan bloed in zijn hoofd verergeren, zodat hij een aanval van verwardheid kan krijgen. Hij wil het niet. Hij moet overeind blijven. Als hij een aanval krijgt, laat ze hem in zijn vet gaar koken. Dan komt ze niet eens naar zijn kamer om hem te verzorgen.

Ze heeft hem al eens een hele nacht in zijn rolstoel laten zitten, voor straf. Hij was zo duizelig dat hij niet bij machte was om zelf in bed te komen. Toen hij naar het toilet ging, was hij naast de pot gevallen. Pas toen had ze hem geholpen. De vernedering had meer pijn gedaan dan de blauwe plekken.

Toch moet hij eventjes gaan liggen. Plat liggen is het best voor de bloedtoevoer naar zijn hoofd. Hij glijdt vanuit de rolstoel op bed en valt achterover. Het is gelukt. Hij rukt de plaid uit de rolstoel en trekt die over zijn hoofd. Donker verzacht zijn woede.

In huis is het stil. Zijn woorden hebben pijn gedaan, daar is hij zeker van. Hij heeft het niet gewild, maar hij heeft het ook niet kunnen voorkomen.

Hoe moet hij hier weg? Nergens zitten ze te wachten op een man die thuis nog een vrouw en dochter heeft die hem kunnen verzorgen. Maar de grens is bereikt.

Kan hij zijn manuscripten meenemen? Al die mappen? Het zijn stofnesten. Daar hebben ze de pest aan in zo’n verpleeghuis.

Hij zal het dorp missen. En de kleine rivier. De kleuren en de geuren van de Wijer.

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (084)

wordt vervolgd

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

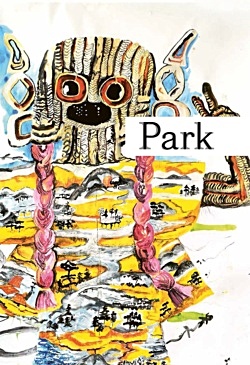

PARK vierde in oktober 2018 het vijfjarig bestaan en maakte een boek waarin de activiteiten in de periode 2016-2018 zijn vastgelegd.

Het rijk geïllustreerde full-colour boek, met teksten van Esther Porcelijn en Rob Moonen, is opnieuw vormgegeven door Berry van Gerwen.

Het rijk geïllustreerde full-colour boek, met teksten van Esther Porcelijn en Rob Moonen, is opnieuw vormgegeven door Berry van Gerwen.

Het telt ruim 240 pagina’s en heeft een oplage van 600 stuks.

Alle tentoonstellingsprojecten, de bijna 200 exposerende kunstenaars en de extra activiteiten in de periode 2016-2018 komen aan bod. Het is de opvolger van het eerder verschenen ‘PARK 2013-2015‘.

Het boek kost € 20,- inclusief BTW, exclusief eventuele verzendkosten. Het verschijnt verschijnt op zondag 16 december 2018 tijdens een boekpresentatie om 16:00 uur bij PARK.

U kunt uw exemplaar ook bestellen via shop@park013.nl

PARK 2016-2018

Teksten van Esther Porcelijn en Rob Moonen

Vormgeving door Berry van Gerwen

PARK

Platform for visual arts

240 pagina’s

Oplage 600 stuks

€ 20,-

PARK is een kunstinitiatief opgericht in 2013 door Rob Moonen in samenwerking met een zestal andere Tilburgse kunstenaars. Op dit moment bestaat de PARK werkgroep uit Linda Arts, René Korten, Rob Moonen en Liza Voetman.

PARK richt zich op actuele ontwikkelingen binnen de hedendaagse kunst én op kunstenaars met gedegen ervaring en bewezen kwaliteit. Er wordt plek geboden aan regionale collega’s maar ook aan landelijk of internationaal opererende kunstenaars, juist om een positieve bijdrage aan de discussie over actuele kunst tot stand te brengen. De werkgroep ambieert het podium van belang te laten zijn op landelijk niveau, maar bij elk project wordt met nadruk gezocht naar een inhoudelijke koppeling met de stad. De werkgroep is er van overtuigd dat samenwerking met andere partijen de zichtbaarheid en functionaliteit van de plek zal versterken, maar ook dat de plek een waardevolle stimulans voor de beeldende kunst in de stad en de regio zal kunnen zijn.

PARK wil steeds nieuwe verbindingen leggen, bijvoorbeeld door (internationaal opererende) curatoren uit te nodigen om kennis te nemen van de keur aan regionale beeldende kunstenaars en daarvan mogelijk enkele op te nemen in een tentoonstellingsproject. PARK wil een bijdrage leveren aan de ontwikkeling van een gunstig productie- en vestigingsklimaat voor beeldend kunstenaars uit de regio door deze in contact te brengen met een nationaal en internationaal netwerk.

Per jaar worden er vijf projecten gerealiseerd met waar mogelijk een bijpassend raamprogramma in de vorm van lezingen, kunstenaarsgesprekken, muziek en film.

PARK

Wilhelminapark 53, 5041 ED Tilburg

info@park013.nl

Twitter.com/ParkTilburg

Facebook.com/Park013

Instagram.com/platform_for_visual_arts

Tijdens tentoonstellingen geopend:

vrijdag 13.00 – 17.00 uur

zaterdag 13.00 – 17.00 uur

zondag 13.00 – 17.00 uur

Toegang is gratis

PARK ligt op 10 minuten loopafstand van het Centraal Station Tilburg in de nabijheid van Museum De Pont. Er is beperkt gratis parkeergelegenheid voor de deur.

# new books

visual arts

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #Editors Choice Archiv, - Book News, Architecture, Art & Literature News, Art Criticism, FDM Art Gallery, Linda Arts, Park, Performing arts, Porcelijn, Esther, Porcelijn, Esther, Sculpture, The talk of the town

`Doe de deur achter je dicht en loop maar naar boven’, roept Tijgers moeder, de lieve roodharige heks.

Mels holt de trap op, zijn vingers roffelend langs de spijlen. De deur van Tijgers slaapkamer staat open. Thija is er al. Ze zit op het hoofdeinde naast Tijger, haar arm om zijn hals. Hun ogen zijn gericht op iets wat voor Tijger op het bed ligt, maar Mels kan het niet zien.

Mels holt de trap op, zijn vingers roffelend langs de spijlen. De deur van Tijgers slaapkamer staat open. Thija is er al. Ze zit op het hoofdeinde naast Tijger, haar arm om zijn hals. Hun ogen zijn gericht op iets wat voor Tijger op het bed ligt, maar Mels kan het niet zien.

Ze hebben hem niet gehoord. Geruisloos gaat Mels achterwaarts de trap af, opent zacht de voordeur en sluipt naar buiten. Met kloppend hart loopt hij naar de Wijer, de handen gebald in zijn broekzakken, alsof hij iemand wil wurgen.

Pas laat komt hij thuis. Het is al donker. Zijn moeder vraagt niets, ze begrijpt altijd alles.

Ze geeft hem thee met een stapel biscuitjes en wacht tot hij tot rust is gekomen.

`Ik heb slecht nieuws’, zegt ze dan. `Wil je het horen. Of is het voor vandaag te veel?’

`Zeg maar.’

`Die zigeunerjongen is gestorven.’

`Hij wilde nog lang niet dood.’ Mels is geschokt. En kwaad. `Het is niet eerlijk.’

`In het leven is niets eerlijk. Wat je graag wilt hebben, krijg je nooit.’

Denkt ze aan zijn vader? Hij vindt het verschrikkelijk dat die twee zo verschillend zijn en bijna nooit met elkaar praten. Zou zijn moeder gelukkiger zijn geweest met een andere man?

Omdat zijn vader er niet is, kan hij wat tegen zijn moeder aanhangen op de bank, op zoek naar troost. Zijn vader wil nooit dat hij zich door haar laat aanhalen. Hij vindt het iets voor moederskindjes.

Die nacht kan hij niet slapen. De hele nacht klinkt er vioolmuziek van heel ver. Woedende muziek. Alsof er wolven naar de maan huilen.

Als het nog donker is, staat hij al op en zoekt op de radio naar verre zenders. Vier uur. Tijd voor nachtraven. De fluitende en joelende tonen die van wie weet waar komen, stemmen hem rustig. Hij weet zeker dat het geheime boodschappen zijn. Misschien zijn er berichten bij uit China. Van de Chinese communisten voor de communisten hier die in het land geheime cellen opzetten, om later, samen met de Chinese legers, de macht te grijpen. Grootvader Rudolf weet zeker dat het ooit zover komt. Hij heeft visioenen van horden grijnzende gele mannetjes die het land onder de voet lopen. Voor elk van hen die sneuvelt komen er tientallen anderen.

Volgens grootvader hebben de Chinezen meer ruimte nodig in de wereld omdat ze met zo veel zijn. `Ze planten zich voort als ratten’, zegt hij. `Alleen maar om de wereld te overheersen. Wij zijn hier al bijna net zover. In het Rood Dorp zijn ook gezinnen met tien of twaalf kinderen. Die leggen rode lopers voor hen uit. Heel Europa zal worden platgewalst door het Gele Gevaar.’ `Is dat net zoiets als de gele verf?’ `Jazeker, mijn jongen, alleen wat erger.’ Maar grootvader Bernhard denkt er precies het tegenovergestelde van. Hij zegt juist dat de Chinezen liever in China blijven en dat China groot genoeg voor hen is. `En als ze dan toch zullen komen, dan zal ik ze vriendelijk ontvangen. In China heb ik alleen maar aardige mensen gezien.’

Mels probeert de code van een zender die een aantal verschillende pieptonen laat horen, te ontcijferen. Drie pieptonen in veel verschillende combinaties. Hij schrijft zijn vingers blauw op een velletje papier, maar alle rijtjes naast elkaar laten geen enkel verband met elkaar zien. Is het een zender die er juist voor bedoeld is om de vijand in de war te brengen? Hij komt er niet eens achter van wie de zender is en uit welk land hij zendt.

Al vroeg staat hij bij Thija aan de deur. Tijger heeft hem voorbij zien komen en volgt hem op de voet.

`Waar was je gisteren?’ vraagt Thija.

`Ik kon niet’, zegt hij. `Heb jij vannacht die viool ook gehoord?’

`Ik heb niets gehoord.’

`Jacob is dood’, zegt Mels. `Het moet zijn vader zijn geweest.’

`We wisten dat hij doodging.’

`We hadden vaker naar hem toe moeten gaan.’

`Stom, om zoiets achteraf te zeggen’, zegt Thija.

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (083)

wordt vervolgd

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature