Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

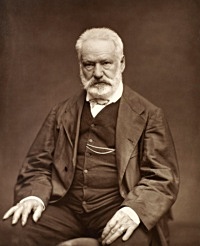

Chanson de grand-père

Dansez, les petites filles,

Toutes en rond.

En vous voyant si gentilles,

Les bois riront.

Dansez, les petites reines,

Toutes en rond.

Les amoureux sous les frênes

S’embrasseront.

Dansez, les petites folles,

Toutes en rond.

Les bouquins dans les écoles

Bougonneront.

Dansez, les petites belles,

Toutes en rond.

Les oiseaux avec leurs ailes

Applaudiront.

Dansez, les petites fées,

Toutes en rond.

Dansez, de bleuets coiffées,

L’aurore au front.

Dansez, les petites femmes,

Toutes en rond.

Les messieurs diront aux dames

Ce qu’ils voudront.

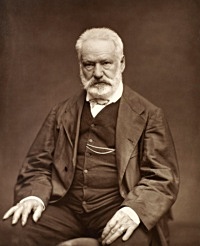

Victor Hugo

(1802-1885)

Chanson de grand-père

(Poème)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Archive G-H, Hugo, Victor, Victor Hugo

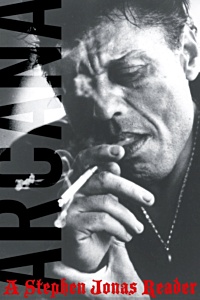

Arcana: A Stephen Jonas Reader is the first selection of his work to appear in 25 years.

With a biographical introduction and a postscript delving into recent discoveries concerning the poet’s birthplace and background, Arcana is a crucial corrective to our understanding of post-war American poetry, restoring Jonas to his rightful place among the period’s vanguard.

With a biographical introduction and a postscript delving into recent discoveries concerning the poet’s birthplace and background, Arcana is a crucial corrective to our understanding of post-war American poetry, restoring Jonas to his rightful place among the period’s vanguard.

Featuring previously uncollected and unpublished work, a section of never-before-seen facsimiles from notebooks, and a generous selection from his innovative serial poem Exercises for Ear (1968), Arcana is a much-needed retrieval of an overlooked American poet, as well as a valuable contribution to African American and Queer literature.

Beginning in the 1950s until his untimely death at age 49, Stephen Jonas (1921-1970) was an influential if underground figure of the New American Poetry. A gay, African-American poet of self-obscured origins, heavily influenced by Ezra Pound and Charles Olson, the Boston-based Jonas was a pioneer of the serial poem and an erudite mentor to such acknowledged masters as Jack Spicer and John Wieners, even as he lived a shadowy existence among drug addicts, thieves, and hustlers.

Major publications include Love, the Poem, the Sea & Other Pieces Examined by Me (1957), Exerces for Ear (1968), and Selected Poems (1994).

“A true poet of modern classic culture in mid-twentieth century U.S.A.”—Allen Ginsberg

Title: Arcana

Subtitle: A Stephen Jonas Reader

Author: Stephen Jonas

Edited by Garrett Caples, Derek Fenner, David Rich, Joseph Torra

Introduction by Joseph Torra

Afterword by David Rich

Publisher: City Lights Publishers

African American poetry

Format Paperback

ISBN-10 0872867919

ISBN-13 9780872867918

Publication Date: 16 April 2019

Main content page count 264

List Price $21.95

# new books

Arcana

A Stephen Jonas Reader

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Archive I-J, Archive I-J, Art & Literature News

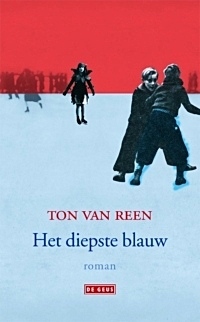

`Zullen we doen wie het eerst bij de kerk is?’ vraagt Tijger.

`Goed’, zegt Mels. `Maar ik wil twintig meter voorsprong. Mijn fiets is niet zo goed als die van jou.’

`Jij mag mijn fiets.’

`Jij mag mijn fiets.’

`Dan starten we gelijk.’

`Jullie wachten maar op me bij de kerk’, zegt Thija.

`Ik tel tot drie’, roept Tijger.

Bij `drie’ vliegen ze ervandoor. De betere fiets helpt Mels niet. Tijger gaat op kop. Maar Mels geeft zich nog niet gewonnen.

Ze naderen het dorp. In volle vaart schiet Tijger van het pad, zoeft rakelings langs de Wijer en vindt het pad terug. Bijna had Mels hem ingehaald.

De kerk is al dichtbij. Het pad wordt breder. Op het laatste stuk van het pad, vanaf het kerkhof tot de kerk, ligt grind. Daar kunnen ze nog harder.

Tijger zoeft de straat op. Een paar tellen later gevolgd door Mels.

Hij hoort een klap. Roepen. Schelden.

Tijger ligt bewegingloos op straat. De fiets ligt verwrongen onder het wiel van de tractor. Mensen schieten te hulp. Vrouwen met handdoeken en verband. Mannen stropen in paniek hun mouwen op.

De boer probeert de fiets onder het tractorwiel vandaan te trekken.

Mels wil naar zijn vriend, maar de mensen duwen hem aan de kant. Hij ziet hoe een straaltje bloed uit het oor van Tijger loopt.

Thija slaat een arm om Mels heen. Hij ziet haar grote ogen waar de tranen uit stromen.

`Hij is dood’, horen ze de man zeggen die zijn oor aan Tijgers borst houdt.

`Hij is dood’, zegt de man tegen Tijgers moeder.

`Hij is dood’, fluistert Mels.

Thija’s tranen vloeien langs haar hals en vormen een donkere vlek op haar lichtgroene blouse.

Een politieman stuurt alle kinderen weg. Het helpt niet als ze zeggen dat Tijger hun vriend is.

`Jullie moeten weg’, zegt de agent. `En hij heet geen Tijger. Hij heet Bart.’

Ze gaan op de bank voor de kerk zitten en zien hoe een ambulance voorrijdt, hoe Tijger op een brancard wordt gelegd en hoe hij het dorp uit wordt gereden.

De moeder van Mels komt naar hem en Thija toe, gaat bij hen zitten en legt een arm om hen heen. Samen zitten ze op de bank, totdat het donker wordt. En dan blijven ze ook nog zitten, omdat ze weer moeten huilen als ze steeds opnieuw het ijselijke gillen van Tijgers moeder horen. De dokter is bij haar, en de pastoor, maar geen pillen en geen gebeden krijgen haar stil.

Dan komt ook de moeder van Thija bij hen zitten. Zo zitten ze daar uren, in het almaar killer wordende maanlicht. En opeens begint Thija’s moeder te vertellen in haar wonderlijke taal die een mengeling is van Engels, Nederlands, Chinees en gebarentaal. Haar woorden verdoven de pijn. Ze vertelt dat ze als meisje leerde zwemmen in de Jangtsekiang. Dat ze als kind met haar ouders uit China is gevlucht, en dat ze het niet erg vindt om niet in China te wonen, maar dat ze zo dolgraag dat plekje aan de Gele Rivier terug zou willen zien.

Pas als beide wijzers van de kerkklok op twaalf staan, gaan ze naar huis.

Als Thija wegloopt, ziet Mels weer hoe dun ze is. Ze is niet meer dan vel over been.

De volgende ochtend wordt er op school over Tijger gesproken. De juf vertelt verhalen over de overstap van het leven naar de dood. En dan moeten ze allemaal huilen. De juf kan zo goed vertellen dat zelfs de meisjes die een hekel hadden aan Tijger moeten huilen.

Ze maken een rouwkrans en leggen die op Tijgers bank. Daar zal hij de rest van het schooljaar blijven liggen.

Na school gaan Mels en Thija naar het molenhuis van grootvader Bernhard.

Ze klimmen naar de doodstille zolder.

`Hoe gaat het in China als kinderen doodgaan?’ vraagt Mels.

`Vraag je dat aan mij?’

`Jij was er toch? Tenminste, jouw moeder.’

`Kinderen begraven ze in glazen kisten.’

`Net als Sneeuwwitje?’

`Soms worden ze verbrand, zodat de ziel van de overledene terug kan keren in een ander lichaam.’

`Kan Tijger dat ook?’

`Hij zal wel moeten’, zegt Thija. `We kunnen niet zonder hem.’

Mels ziet dat er tranen in haar ogen staan en daarom moeten ze opeens weer allebei huilen.

`Hij moet terugkomen’, zegt Mels.

`Misschien is hij al terug.’ Thija wijst op de grote vlinder die op de ruit gaat zitten en met zijn grote gekleurde vleugels naar hen wuift.

`Zo’n grote kapel heb ik hier nog nooit gezien’, zegt Mels. `Kapellen zijn heel zeldzaam. Denk je écht dat hij het is?’

`Ik denk het wel’, zegt Thija. `In China leven de zielen van gestorven kinderen ook voort in vlinders. En dan vliegen ze wuivend door het dorp. Je ziet toch dat hij naar ons wuift! Ik vind het echt iets voor Tijger.’

Bij de begrafenis loopt Thija aan de hand van haar moeder. Mels loopt ingehaakt in de arm van zijn moeder, die zachtjes huilt, maar toch zo hard dat iedereen het hoort. Ze kan er niets aan doen.

Mels huilt niet. En ook Thija huilt niet meer. Het meer achter haar ogen is leeg. Maar haar ogen staan schuiner dan ooit, alsof ze bij de begrafenis van Tijger extra mooi wil zijn.

De kist van Tijger wordt gedragen door mannen uit de buurt.

Het hele dorp loopt van de kerk naar het kerkhof. Ook de boer die Tijger doodgereden heeft. Hij heeft een vreemd bleek voorhoofd, precies waar zijn pet gewoonlijk staat, de rest van zijn gezicht is bruingebrand door de zon. Hij houdt de pet in de hand en knijpt hem bijna fijn.

De mannen laten Tijgers kist in het graf zakken. Mels probeert naar zichzelf te luisteren, maar zo stil is het in zijn hoofd nog nooit geweest.

Thija fluistert iets. Haar mond gaat open. Ze wijst. Dan pas ziet hij de kapel met grote gekleurde vleugels die over het kerkhof vliegt en tussen de bomen verdwijnt. Tijger is voorgoed vertrokken.

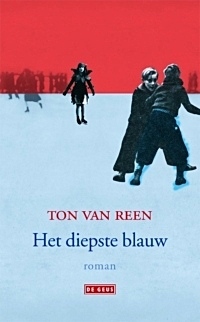

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (097)

wordt vervolgd

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

Love, death, Bruce Willis, public urination, being a woman, love, The Nanny, love.

This pamphlet of poetry by Hera Lindsay Bird is a startling departure from her bestselling debut Hera Lindsay Bird by defying convention and remaining exactly the same, only worse. This collection, which focuses on love, childish behaviours, 90’s celebrity references and being a woman, is sure to confirm all your worst suspicions and prejudices.

This pamphlet of poetry by Hera Lindsay Bird is a startling departure from her bestselling debut Hera Lindsay Bird by defying convention and remaining exactly the same, only worse. This collection, which focuses on love, childish behaviours, 90’s celebrity references and being a woman, is sure to confirm all your worst suspicions and prejudices.

Selected in 2018 by Carol Ann Duffy as part of the Laureate’s Choice Collection. Carol Ann Duffy: “Without doubt the most arresting and original new young poet – on page and in performance – to arrive.”

Hera Lindsay Bird was born in Thames, NZ, in 1987 and lives in Wellington. Her debut book of verse, blithely titled Hera Lindsay Bird, was published in 2016 to immediate and vast acclaim, and won best first book of poetry at the 2017 Ockham New Zealand Book Awards.

Pamper Me to Hell & Back

Author: Hera Lindsay Bird

Published by Smith/Doorstop

(The Poetry Business)

Language: English

ISBN-10: 1910367842

ISBN-13: 978-1910367841

Paperback

30 pages

2018

£7.50

# new poetry

Hera Lindsay Bird

Pamper Me to Hell & Back

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Art & Literature News

Singeries

Quand je te vois penché, mon mignon, tout en nage,

Sur le croûton de pain qui te sert de joujou,

Je me repens, mon Dieu, d’avoir pris pour un page

Ce qui n’était pourtant qu’un affreux sapajou.

C’est un maki mordant ses dix doigts avec rage,

Ce faune gentillet, taillé comme un bijou,

Un ouistiti grimpant aux barreaux de sa cage,

Un macaque à poil ras, un singe en acajou.

Ton masque enluminé, sillonné de grimaces,

Semble servir d’album à croquis aux limaces

Pour crayonner l’argent de leurs chemins crochus.

Et les casques noircis qui couronnent tes ongles,

Piqués dans tes cheveux brouillés comme des jungles,

Font penser que tu dois avoir les pieds fourchus.

Marcel Schwob

(1867-1905)

Singeries

Juin 1888

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #Editors Choice Archiv, Archive S-T, Archive S-T, Marcel Schwob

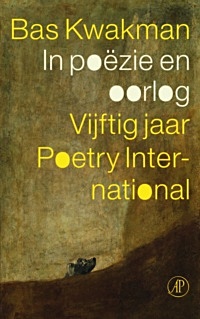

In In poëzie en oorlog onthult directeur Bas Kwakman van Poetry International op verrassende en soms ontluisterende wijze de wereld van de poëzie.

Daarbij ontziet de schrijver niets en niemand, ook zichzelf niet. In poëzie en oorlog is alles geoorloofd.

Daarbij ontziet de schrijver niets en niemand, ook zichzelf niet. In poëzie en oorlog is alles geoorloofd.

Leidraad is de geschiedenis van het Poetry International Festival in Rotterdam, dat in 1970 in anarchie werd geboren en inmiddels wereldwijd een van de belangrijkste ontmoetingsplaatsen voor dichters en poëzieliefhebbers is geworden.

Gedreven door de liefde voor poëzie en een gezonde argwaan jegens het menselijke bedrijf daarachter beschrijft Kwakman met warmte, humor, kennis en verbazing zijn unieke ervaringen in de bijzondere wereld tussen de versregels.

Auteur: Bas Kwakman

In poëzie en oorlog.

Vijftig jaar Poetry International

Uitgeverij: De Arbeiderspers

NUR: 320

Paperback

ISBN: 9789029525602

Taal: Nederlands

Bladzijden: 400 pp.

Paperback

Literaire non-fictie

Prijs: € 24,99

Publicatiedatum: 21-05-2019

# new books

In poëzie en oorlog.

Vijftig jaar Poetry International

Bas Kwakman

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #More Poetry Archives, - Book Lovers, - Book News, Archive K-L, Art & Literature News, MODERN POETRY, Poetry International

Il fait froid

L’hiver blanchit le dur chemin

Tes jours aux méchants sont en proie.

La bise mord ta douce main ;

La haine souffle sur ta joie.

La neige emplit le noir sillon.

La lumière est diminuée…

Ferme ta porte à l’aquilon !

Ferme ta vitre à la nuée !

Et puis laisse ton coeur ouvert !

Le coeur, c’est la sainte fenêtre.

Le soleil de brume est couvert ;

Mais Dieu va rayonner peut-être !

Doute du bonheur, fruit mortel ;

Doute de l’homme plein d’envie ;

Doute du prêtre et de l’autel ;

Mais crois à l’amour, ô ma vie !

Crois à l’amour, toujours entier,

Toujours brillant sous tous les voiles !

A l’amour, tison du foyer !

A l’amour, rayon des étoiles !

Aime, et ne désespère pas.

Dans ton âme, où parfois je passe,

Où mes vers chuchotent tout bas,

Laisse chaque chose à sa place.

La fidélité sans ennui,

La paix des vertus élevées,

Et l’indulgence pour autrui,

Eponge des fautes lavées.

Dans ta pensée où tout est beau,

Que rien ne tombe ou ne recule.

Fais de ton amour ton flambeau.

On s’éclaire de ce qui brûle.

A ces démons d’inimitié

Oppose ta douceur sereine,

Et reverse leur en pitié

Tout ce qu’ils t’ont vomi de haine.

La haine, c’est l’hiver du coeur.

Plains-les ! mais garde ton courage.

Garde ton sourire vainqueur ;

Bel arc-en-ciel, sors de l’orage !

Garde ton amour éternel.

L’hiver, l’astre éteint-il sa flamme ?

Dieu ne retire rien du ciel ;

Ne retire rien de ton âme !

Victor Hugo

(1802-1885)

Il fait froid

(Poème)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Archive G-H, Hugo, Victor, Victor Hugo

Who has not suffered grief?

Who has not suffered grief?

In Mourning Songs, the brilliant poet and editor Grace Schulman has gathered together the most moving poems about sorrow by the likes of Elizabeth Bishop, William Carlos Williams, Gwendolyn Brooks, Neruda, Catullus, Dylan Thomas, W. H. Auden, Shakespeare, Emily Dickinson, W. S. Merwin, Lorca, Denise Levertov, Keats, Hart Crane, Michael Palmer, Robert Frost, Hopkins, Hardy, Bei Dao, and Czeslaw Milosz—to name only some of the masters in this slim volume.

“The poems in this collection,” as Schulman notes in her introduction, “sing of grief as they praise life.” She notes: “As any bereaved survivor knows, there is no consolation. ‘Time doesn’t heal grief; it emphasizes it,’ wrote Marianne Moore.

The loss of a loved one never leaves us. We don’t want it to. In grief, one remembers the beloved. But running beside it, parallel to it, is the joy of existence, the love that causes pain of loss, the loss that enlarges us with the wonder of existence.”

Winner of the Poetry Society of America’s highest award, The Frost Medal, Grace Schulman is the author of seven poetry volumes as well as a book of essays and a new memoir, Strange Paradise: Portrait of a Marriage, about her life with her beloved late husband Jerome. She is a Distinguished Professor of English at Baruch College, CUNY, the former director of the Poetry Center, 92nd Street Y, and was for thirty-five years the poetry editor of The Nation.

Mourning Songs

Poems of sorrow and Beauty

Edited by Grace Schulman

Paperback

96 pages

Publisher: New Directions

Language: English

ISBN-10: 0811228665

ISBN-13: 978-0811228664

Product Dimensions: 4 x 6 inches

Price US 11.95

1 edition: May 28, 2019

# new books

Mourning Songs

Poetry

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Archive S-T, Archive S-T, Art & Literature News, Danse Macabre

De herinnering aan de grote brand emotioneert hem. Hij merkt dat zijn hoofd gaat dazen, of er bijen in rond zoemen. Het zijn geen bijen, maar kinderstemmen. De school is uit.

`Zit je hier al lang, opa?’ Het zijn Afke en Zhia. In hun kleurige jurken hinkelen ze rond zijn rolstoel.

`Zit je hier al lang, opa?’ Het zijn Afke en Zhia. In hun kleurige jurken hinkelen ze rond zijn rolstoel.

`Ik wachtte op jullie.’

`Wat gaan we doen?’

`Naar de watermolen?’

`Goed’, zegt Afke.

`Is er feest?’

`Hoezo?’

`Omdat jullie jurken dragen. Jullie lopen altijd in broeken.’

`Straks ga ik bij haar thuis spelen’, zegt Afke. `Zhia’s oma is over. Ze is heel aardig, maar tegen meisjes in broeken praat ze niet.’

`Ik vind die jurken ook veel mooier.’ Hij meent het echt.

Als vlinders lopen ze voor hem uit.

Bij het vlondertje van het voormalige huis van grootvader Rudolf staan ze even stil. Omdat ze daar altijd even stilstaan en omdat Mels er altijd wat vertelt.

`Hier legde ik vroeger mijn boot vast’, zegt hij. `Dan liep ik naar binnen. Grootvader vertelde vaak over zijn denkbeeldige reizen, of over de oorlog. In het schuurtje had hij een klein museum.’

`Waar is dat spul gebleven?’ vraagt Afke.

`Het meeste ligt bij mij op zolder.’

`Mogen wij er gaan kijken?’

`Zeker. Het spul moet er trouwens weg. Misschien is het iets voor een echt museum.’

`En als we het zelf willen houden?’ zegt Afke. `Je kunt het aan mij geven. Ik bewaar het goed.’

`Dan mag jij alles hebben.’

De meisjes hinkelen voor hem uit. Als ze te ver voorop zijn, wachten ze op hem.

`Ik wil het weitje bij mijn grootvaders huis wel weer eens zien’, zegt Mels.

`Wij spelen daar vaak’, zegt Afke.

`Vroeger kwam er nooit iemand. Alleen wij. Tijger heeft er een kist met spullen begraven. Voor later.’

`Wat zat erin?’

`Zijn cadeaus van een verjaardagsfeestje. Ook de mondharmonica die ik hem had gegeven.’

`Die is allang verroest’, zegt Zhia. `Waarom heeft hij dat spul begraven?’

`Tijger was net een eekhoorn. Hij stopte de dingen waarvan hij hield weg.’

`Eekhoorns vergeten waar ze hun noten begraven hebben’, zegt Zhia.

`Tijger kreeg niet eens de tijd om zijn spullen terug te zoeken.’

Bij de brug slaat hij de weg in die langs de Wijer naar de molen en de parkeerplaats loopt.

`Jij rijdt hard’, roept Afke tegen hem. `Straks rij je het water in.’

`Passen júllie maar op. Er zitten duiveltjes in het water, die je met hun haakstokken de beek in trekken.’

Hij stopt omdat hij een dode kraai aan de kant ziet liggen. Verderop ligt een dode egel. Vroeger stonden hier de frambozen van zijn moeder. De dieren hadden er vrij spel, maar op het asfalt hebben ze geen kans. De vogels en dieren die vroeger te snel of te stekelig waren om ze te kunnen pakken, zijn nu te langzaam of te zacht om te ontsnappen aan de auto’s van de mensen die de molen bezoeken.

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (096)

wordt vervolgd

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

A poet and anthropologist explores the surprising world of war games in mock Middle Eastern villages in which the U.S. military trains.

With deft lyrical attention, these documentary poems reveal the nuanced culture and violence of the war machine—alive and well within these basecamp villages, the American military, and, ultimately, the human heart.

With deft lyrical attention, these documentary poems reveal the nuanced culture and violence of the war machine—alive and well within these basecamp villages, the American military, and, ultimately, the human heart.

Kill Class is based on Nomi Stone’s two years of fieldwork in mock Middle Eastern villages at military bases across the United States.

The speaker in these poems, an anthropologist, both witnesses and participates in combat training exercises staged at “Pineland,” a simulated country in the woods of the American South, where actors of Middle Eastern origin are hired to theatricalize war, repetitively pretending to bargain and mourn and die.

Kill Class is an arresting ethnography of American military culture, one that allows readers to circle at length through the cloverleaf interchanges where warfare nestles into even the most mundane corners of everyday life.

Nomi Stone is a poet, anthropologist, and author of a previous book of poems, Stranger’s Notebook (TriQuarterly, 2008). Winner of a 2018 Pushcart Prize, Stone’s poems appear recently in POETRY Magazine, American Poetry Review, The Best American Poetry, The New Republic, Tin House, New England Review, and elsewhere. Stone has a PhD in Cultural Anthropology from Columbia University, an MPhil in Middle East Studies from Oxford, and an MFA in Poetry from Warren Wilson College. She teaches at Princeton University and her ethnography in progress, Human Technology and American War, is a finalist for the University of California Press Atelier Series.

Kill Class

by Nomi Stone (Author)

Paperback

87 pages

Publisher: Tupelo Press

February 1, 2019

Language: English

Poetry

ISBN-10: 1946482196

ISBN-13: 978-1946482198

$17.95

# new poetry

Kill Class

by Nomi Stone

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: *War Poetry Archive, - Book News, - Book Stories, Archive S-T, Archive S-T, Art & Literature News, WAR & PEACE

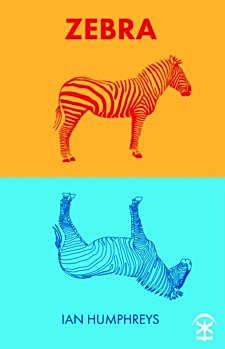

In Zebra, a boy steps tentatively from the shadows onto a strobe-lit dancefloor.

Ian Humphreys’ much-anticipated debut shimmers with music, wit and humour while exploring mixed identities, otherness, and coming-of-age as a gay man in 1980s Manchester.

Ian Humphreys’ much-anticipated debut shimmers with music, wit and humour while exploring mixed identities, otherness, and coming-of-age as a gay man in 1980s Manchester.

These acutely-observed, joyful poems pay homage to those who took the first steps – minority writers, LGBT civil rights activists, 70s queer night-clubbers and the poet’s own mixed-race parents.

A heady cocktail of the playful, political and mythical, Humphreys’ Zebra is also a creature of opposites – light and dark, countryside and cityscape, highs and lows. The collection moves from semi-rural England to the metropolitan hubs of Hong Kong, London and New York, circling its subjects, often finding the uncanny in the familiar, always drawing the reader centre-stage.

Ian’s debut full-length collection of poetry, Zebra, is forthcoming from Nine Arches Press in Spring, 2019. A portfolio of his poems was published in 2017 by Bloodaxe in Ten: Poets of the New Generation. His work has featured in magazines and anthologies, such as The Poetry Review, The Rialto, Ambit, Magma and The Forward Book of Poetry.

Ian Humphreys has won a number of awards, including first prize in both the 2016 Hamish Canham Prize and the 2013 PENfro Open Poetry Competition. In 2018, he was Highly Commended in the Forward Prizes for Poetry. Ian has also been published internationally in overseas journals and anthologies. His fiction has been shortlisted three times for the Bridport Prize.

Ian Humphreys has had work featured in journals and anthologies such as The Poetry Review, The Rialto, Magma and The Forward Book of Poetry 2019. Awards include first prize in the Poetry Society’s Hamish Canham Prize. He has been highly commended in the Forward Prizes for Poetry, and two of his poems have been longlisted in the National Poetry Competition. Ian is a fellow of The Complete Works, which promotes diversity, quality and innovation in British poetry. A portfolio of his poems is published in Ten: Poets of the New Generation (Bloodaxe).

Zebra

Ian Humphreys

Poetry

Format Paperback

80 pages

Dimensions 150 x 210 x 22mm

Publication date 11 Apr 2019

Publisher Nine Arches Press

Publication City/Country Rugby, United Kingdom

Language English

ISBN10 1911027700

ISBN13 9781911027706

Cover artwork: Louise Crosby

BIC Code: DCF

€15,99

# new poetry

Ian Humphreys

Zebra

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Book Stories, Archive G-H, Archive G-H, Art & Literature News, Riding a Zebra

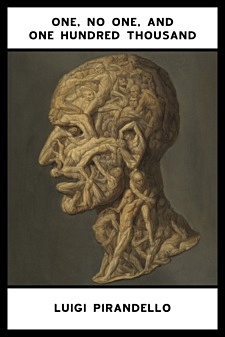

Luigi Pirandello’s extraordinary final novel begins when Vitangelo Moscarda’s wife remarks that Vitangelo’s nose tilts to the right.

This commonplace interaction spurs the novel’s unemployed, wealthy narrator to examine himself, the way he perceives others, and the ways that others perceive him.

This commonplace interaction spurs the novel’s unemployed, wealthy narrator to examine himself, the way he perceives others, and the ways that others perceive him.

At first he only notices small differences in how he sees himself and how others do; but his self-examination quickly becomes relentless, dizzying, leading to often darkly comic results as Vitangelo decides that he must demolish that version of himself that others see.

Pirandello said of his 1926 novel that it “deals with the disintegration of the personality. It arrives at the most extreme conclusions, the farthest consequences.” Indeed, its unnerving humor and existential dissection of modern identity find counterparts in Samuel Beckett’s Molloy trilogy and the works of Thomas Bernhard and Vladimir Nabokov.

Luigi Pirandello (1867-1936) was an Italian author, who was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1934 for his “bold and brilliant renovation of the drama and the stage.” Pirandello’s works include novels, hundreds of short stories, and plays. Pirandello’s plays are often seen as forerunners for the theatre of the absurd.

One, No One, and One Hundred Thousand

Luigi Pirandello

Translated by William Weaver

Publisher Spurl Editions

Format Paperback

218 pages

ISBN-10 194367907X

ISBN-13 9781943679072

2018

$18.00

# new books

Title One, No One, and One Hundred Thousand

Author Luigi Pirandello

Translated by William Weaver

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Book Stories, Archive O-P, Archive O-P, Luigi Pirandello, Pirandello, Luigi, Pirandello, Luigi, Samuel Beckett, Thomas Bernhard, Vladimir Nabokov

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature