Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

Toddler-Hunting and Other Stories introduces a startlingly original voice. Winner of Japan’s top literary prizes for fiction (among them the Akutagawa, the Tanizaki, the Noma, and the Yomiuri), Taeko Kono writes with a strange beauty, pinpricked with sadomasochistic and disquieting scenes.

In the title story, the protagonist loathes young girls, but compulsively buys expensive clothes for little boys so that she can watch them dress and undress. The impersonal gaze Taeko Kono turns on this behavior transfixes the reader with a fatal question: What are we hunting for? And why?

In the title story, the protagonist loathes young girls, but compulsively buys expensive clothes for little boys so that she can watch them dress and undress. The impersonal gaze Taeko Kono turns on this behavior transfixes the reader with a fatal question: What are we hunting for? And why?

Multiplying perspectives and refracting light from the strangely facing mirrors of fantasy and reality, pain and pleasure, these ten stories present Kono at her very best.

Winner of Japan’s top literary prizes (the Akutagawa, the Tanizaki, the Noma, and the Yomiuri), Taeko Kono writes with a strange beauty: her tales are pinpricked with disquieting scenes, her characters all teetering on self-dissolution, especially in the context of their intimate relationships. In the title story, the protagonist loathes young girls but compulsively buys expensive clothes for little boys so that she can watch them dress and undress. Taeko Kono’s detached gaze at this alarming behavior transfixes the reader: What are we hunting for? And why? Multiplying perspectives and refracting light from the facing mirrors of fantasy and reality, pain and pleasure, Toddler-Hunting and Other Stories presents a major Japanese writer at her very best.

Toddler Hunting: And Other Stories

Taeko Kono

Publisher: New Directions Publishing Corporation

Publication date: Nov. 2018

Publication country:United States

Paperback

Pages:272

ISBN: 978-0-81122-827-5

17.00 €

# More books

Taeko Kono

Fiction

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Book Stories, Archive K-L

Met haar succesdebuut Habitus wint Radna Fabias na de C. Buddingh’-prijs 2018 en de Awater Poëzieprijs en Herman De Coninckprijs 2019 óók deze eerste editie van De Grote Poëzieprijs.

De prijs, € 25.000,- voor de beste Nederlandstalige bundel van het jaar, werd op de slotdag van het gouden Poetry International Festival uitgereikt samen met de C. Buddingh’-prijs, die naar Roberta Petzoldt ging, voor haar debuut Vruchtwatervuurlinie’. Habitus is daarmee zonder meer de meest prijswinnende debuutbundel ooit.

Ook werden op het festival prijzen uitgereikt door jongeren, een initiatief van School der Poëzie.

De School der Poëzie-Communityprijs ging naar Ted van Lieshout voor Ze gaan er met je neus vandoor,

Roelof ten Napel kreeg de Jongerenprijs voor Het woedeboek waarmee hij ook kans maakte op De Grote Poëzieprijs én de C. Buddingh’-prijs. Met het uitreikingsprogramma ‘Prijs de poëzie!’ sloot Poetry International het gouden jubileumfestival even feestelijk af als dat het begon.

De Grote Poëzieprijs voor Radna Fabias

De Grote Poëzieprijs is dé prijs voor Nederlandstalige poëzie en bekroont de beste Nederlandstalige bundel van het jaar met € 25.000,-.

De Grote Poëzieprijs is dé prijs voor Nederlandstalige poëzie en bekroont de beste Nederlandstalige bundel van het jaar met € 25.000,-.

De jury van De Grote Poëzieprijs 2019 kreeg 150 bundels ter lezing en nomineerde er niet vijf maar zes, vanwege het hoge aantal inzendingen, de verlengde periode waarover werd gejureerd en de aangetroffen kwaliteit.

Opnieuw gaat de hoofdprijs dus naar Radna Fabias: “Fabias graaft net zo lang in wat bedenkelijk is – waarbij ze ook zichzelf niet spaart – totdat de complexiteit van een probleem zich openbaart.

Dit maakt dat Habitus (Arbeiderspers) deelneemt aan het ‘gesprek van de dag’, maar tegelijk – en belangrijker – dat de bundel er ook een krachtig tegengif tegen is.

Niets is eenvoudig in deze bundel, niets is op te lossen met een paar slimme oneliners of standpunten. Fabias maakt het persoonlijke politiek en het politieke persoonlijk,” oordeelde de jury.

De C. Buddingh’-prijs voor Roberta Petzoldt

De prijs voor beste Nederlandstalige poëziedebuut – jaarlijks uitgereikt op het Poetry International Festival – gaat dit jaar naar Roberta Petzoldt.

De prijs voor beste Nederlandstalige poëziedebuut – jaarlijks uitgereikt op het Poetry International Festival – gaat dit jaar naar Roberta Petzoldt.

Haar debuut Vruchtwatervuurlinie (Van Oorschot) gaat over verlies en is strijdbaar, humoristisch, prikkelend en fel maar boven alles een rigoureus allerindividueelst onderzoek waarbij de dichter, sneller dan de eigen schaduw, de poëzie zelf op de staart probeert te trappen of ‘zonder vliegtuig de wolken raken / bewegen door / een getraind gevoel voor humor / en een eenzame logica’.

Op intieme wijze creëert de dichter een verrassend nieuw poëtisch universum, wat weergaloze gedichten en tijdloze regels oplevert: ‘ik weet dat mensen op hun honden lijken, maar jij / lijkt op de hond van iemand anders’”, aldus de jury.

Jongerenprijzen bij De Grote Poëzieprijs

School der Poëzie reikte op de slotavond van Poetry International twee prijzen uit namens de Poëzie Community en namens scholieren uit Nederland en Vlaanderen.

School der Poëzie reikte op de slotavond van Poetry International twee prijzen uit namens de Poëzie Community en namens scholieren uit Nederland en Vlaanderen.

De Poëzie Community van School der Poëzie koos unaniem voor Ze gaan er met je neus vandoor (Leopold) van Ted van Lieshout, omdat het “een avontuur was om te lezen.” Jongeren van scholen uit Antwerpen, Amsterdam, Rotterdam en Gent namen deel aan workshops van School der Poëzie en lieten zich inspireren door de gedichten van de zes genomineerden. Zij kenden hun Jongerenprijs toe aan Roelof ten Napel voor Het woedeboek (Hollands Diep) “omdat het over woede gaat én over liefde.”

De jury van De Grote Poëzieprijs bestond uit Joost Baars, Yra van Dijk, Adriaan van Dis, Cindy Kerseborn en Maud Vanhauwaert.

De jury van De Grote Poëzieprijs bestond uit Joost Baars, Yra van Dijk, Adriaan van Dis, Cindy Kerseborn en Maud Vanhauwaert.

Zij nomineerden naast Habitus van Radna Fabias ook Nachtboot van Maria Barnas, Stalker van Joost Decorte, Het woedeboek van Roelof ten Napel, Genadeklap van Willem Jan Otten en Onze kinderjaren van Xavier Roelens. De jury van de C. Buddingh’-prijs bestond uit Els Moors, Tsead Bruinja en Kila van der Starre. Zij nomineerden ook Obelisque van Obe Alkema, Dwaallichten van Gerda Blees en Het woedeboek van Roelof ten Napel.

Eerste Grote Poëzieprijs voor Radna Fabias

Roberta Petzoldt wint ‘de Buddingh’

Jongerenprijzen voor Ted van Lieshout en Roelof ten Napel

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #Editors Choice Archiv, #More Poetry Archives, - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive E-F, Archive E-F, Archive K-L, Archive M-N, Archive O-P, Art & Literature News, Awards & Prizes, Lieshout, Ted van, Poetry International

Exil

Si je pouvais voir, ô patrie,

Tes amandiers et tes lilas,

Et fouler ton herbe fleurie,

Hélas !

Si je pouvais, – mais, ô mon père,

O ma mère, je ne peux pas, –

Prendre pour chevet votre pierre,

Hélas !

Dans le froid cercueil qui vous gêne,

Si je pouvais vous parler bas,

Mon frère Abel, mon frère Eugène,

Hélas !

Si je pouvais, ô ma colombe,

Et toi, mère, qui t’envolas,

M’agenouiller sur votre tombe,

Hélas !

Oh ! vers l’étoile solitaire,

Comme je lèverais les bras !

Comme je baiserais la terre,

Hélas !

Loin de vous, ô morts que je pleure,

Des flots noirs j’écoute le glas ;

Je voudrais fuir, mais je demeure,

Hélas !

Pourtant le sort, caché dans l’ombre,

Se trompe si, comptant mes pas,

Il croit que le vieux marcheur sombre

Est las.

Victor Hugo

(1802-1885)

Exil

(Poème)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Archive G-H, Hugo, Victor, Victor Hugo

Sredni Vashtar

Conradin was ten years old, and the doctor had pronounced his professional opinion that the boy would not live another five years. The doctor was silky and effete, and counted for little, but his opinion was endorsed by Mrs. de Ropp, who counted for nearly everything. Mrs. De Ropp was Conradin’s cousin and guardian, and in his eyes she represented those three-fifths of the world that are necessary and disagreeable and real; the other two-fifths, in perpetual antagonism to the foregoing, were summed up in himself and his imagination. One of these days Conradin supposed he would succumb to the mastering pressure of wearisome necessary things — such as illnesses and coddling restrictions and drawn-out dullness. Without his imagination, which was rampant under the spur of loneliness, he would have succumbed long ago.

Mrs. de Ropp would never, in her honestest moments, have confessed to herself that she disliked Conradin, though she might have been dimly aware that thwarting him “for his good” was a duty which she did not find particularly irksome. Conradin hated her with a desperate sincerity which he was perfectly able to mask. Such few pleasures as he could contrive for himself gained an added relish from the likelihood that they would be displeasing to his guardian, and from the realm of his imagination she was locked out — an unclean thing, which should find no entrance.

Mrs. de Ropp would never, in her honestest moments, have confessed to herself that she disliked Conradin, though she might have been dimly aware that thwarting him “for his good” was a duty which she did not find particularly irksome. Conradin hated her with a desperate sincerity which he was perfectly able to mask. Such few pleasures as he could contrive for himself gained an added relish from the likelihood that they would be displeasing to his guardian, and from the realm of his imagination she was locked out — an unclean thing, which should find no entrance.

In the dull, cheerless garden, overlooked by so many windows that were ready to open with a message not to do this or that, or a reminder that medicines were due, he found little attraction. The few fruit-trees that it contained were set jealously apart from his plucking, as though they were rare specimens of their kind blooming in an arid waste; it would probably have been difficult to find a market-gardener who would have offered ten shillings for their entire yearly produce. In a forgotten corner, however, almost hidden behind a dismal shrubbery, was a disused tool-shed of respectable proportions, and within its walls Conradin found a haven, something that took on the varying aspects of a playroom and a cathedral. He had peopled it with a legion of familiar phantoms, evoked partly from fragments of history and partly from his own brain, but it also boasted two inmates of flesh and blood. In one corner lived a ragged-plumaged Houdan hen, on which the boy lavished an affection that had scarcely another outlet. Further back in the gloom stood a large hutch, divided into two compartments, one of which was fronted with close iron bars. This was the abode of a large polecat-ferret, which a friendly butcher-boy had once smuggled, cage and all, into its present quarters, in exchange for a long-secreted hoard of small silver. Conradin was dreadfully afraid of the lithe, sharp-fanged beast, but it was his most treasured possession. Its very presence in the tool-shed was a secret and fearful joy, to be kept scrupulously from the knowledge of the Woman, as he privately dubbed his cousin. And one day, out of Heaven knows what material, he spun the beast a wonderful name, and from that moment it grew into a god and a religion. The Woman indulged in religion once a week at a church near by, and took Conradin with her, but to him the church service was an alien rite in the House of Rimmon. Every Thursday, in the dim and musty silence of the tool-shed, he worshipped with mystic and elaborate ceremonial before the wooden hutch where dwelt Sredni Vashtar, the great ferret. Red flowers in their season and scarlet berries in the winter-time were offered at his shrine, for he was a god who laid some special stress on the fierce impatient side of things, as opposed to the Woman’s religion, which, as far as Conradin could observe, went to great lengths in the contrary direction. And on great festivals powdered nutmeg was strewn in front of his hutch, an important feature of the offering being that the nutmeg had to be stolen. These festivals were of irregular occurrence, and were chiefly appointed to celebrate some passing event. On one occasion, when Mrs. de Ropp suffered from acute toothache for three days, Conradin kept up the festival during the entire three days, and almost succeeded in persuading himself that Sredni Vashtar was personally responsible for the toothache. If the malady had lasted for another day the supply of nutmeg would have given out.

The Houdan hen was never drawn into the cult of Sredni Vashtar. Conradin had long ago settled that she was an Anabaptist. He did not pretend to have the remotest knowledge as to what an Anabaptist was, but he privately hoped that it was dashing and not very respectable. Mrs. de Ropp was the ground plan on which he based and detested all respectability.

After a while Conradin’s absorption in the tool-shed began to attract the notice of his guardian. “It is not good for him to be pottering down there in all weathers,” she promptly decided, and at breakfast one morning she announced that the Houdan hen had been sold and taken away overnight. With her short-sighted eyes she peered at Conradin, waiting for an outbreak of rage and sorrow, which she was ready to rebuke with a flow of excellent precepts and reasoning. But Conradin said nothing: there was nothing to be said. Something perhaps in his white set face gave her a momentary qualm, for at tea that afternoon there was toast on the table, a delicacy which she usually banned on the ground that it was bad for him; also because the making of it “gave trouble,” a deadly offence in the middle-class feminine eye.

“I thought you liked toast,” she exclaimed, with an injured air, observing that he did not touch it.

“Sometimes,” said Conradin.

In the shed that evening there was an innovation in the worship of the hutch-god. Conradin had been wont to chant his praises, to-night he asked a boon.

“Do one thing for me, Sredni Vashtar.”

The thing was not specified. As Sredni Vashtar was a god he must be supposed to know. And choking back a sob as he looked at that other empty corner, Conradin went back to the world he so hated.

And every night, in the welcome darkness of his bedroom, and every evening in the dusk of the tool-shed, Conradin’s bitter litany went up: “Do one thing for me, Sredni Vashtar.”

Mrs. de Ropp noticed that the visits to the shed did not cease, and one day she made a further journey of inspection.

“What are you keeping in that locked hutch?” she asked. “I believe it’s guinea-pigs. I’ll have them all cleared away.”

Conradin shut his lips tight, but the Woman ransacked his bedroom till she found the carefully hidden key, and forthwith marched down to the shed to complete her discovery. It was a cold afternoon, and Conradin had been bidden to keep to the house. From the furthest window of the dining-room the door of the shed could just be seen beyond the corner of the shrubbery, and there Conradin stationed himself. He saw the Woman enter, and then he imagined her opening the door of the sacred hutch and peering down with her short-sighted eyes into the thick straw bed where his god lay hidden. Perhaps she would prod at the straw in her clumsy impatience. And Conradin fervently breathed his prayer for the last time. But he knew as he prayed that he did not believe. He knew that the Woman would come out presently with that pursed smile he loathed so well on her face, and that in an hour or two the gardener would carry away his wonderful god, a god no longer, but a simple brown ferret in a hutch. And he knew that the Woman would triumph always as she triumphed now, and that he would grow ever more sickly under her pestering and domineering and superior wisdom, till one day nothing would matter much more with him, and the doctor would be proved right. And in the sting and misery of his defeat, he began to chant loudly and defiantly the hymn of his threatened idol:

Sredni Vashtar went forth,

His thoughts were red thoughts and his teeth were white.

His enemies called for peace, but he brought them death.

Sredni Vashtar the Beautiful.

And then of a sudden he stopped his chanting and drew closer to the window-pane. The door of the shed still stood ajar as it had been left, and the minutes were slipping by. They were long minutes, but they slipped by nevertheless. He watched the starlings running and flying in little parties across the lawn; he counted them over and over again, with one eye always on that swinging door. A sour-faced maid came in to lay the table for tea, and still Conradin stood and waited and watched. Hope had crept by inches into his heart, and now a look of triumph began to blaze in his eyes that had only known the wistful patience of defeat. Under his breath, with a furtive exultation, he began once again the paean of victory and devastation. And presently his eyes were rewarded: out through that doorway came a long, low, yellow-and-brown beast, with eyes a-blink at the waning daylight, and dark wet stains around the fur of jaws and throat. Conradin dropped on his knees. The great polecat-ferret made its way down to a small brook at the foot of the garden, drank for a moment, then crossed a little plank bridge and was lost to sight in the bushes. Such was the passing of Sredni Vashtar.

“Tea is ready,” said the sour-faced maid; “where is the mistress?”

“She went down to the shed some time ago,” said Conradin.

And while the maid went to summon her mistress to tea, Conradin fished a toasting-fork out of the sideboard drawer and proceeded to toast himself a piece of bread. And during the toasting of it and the buttering of it with much butter and the slow enjoyment of eating it, Conradin listened to the noises and silences which fell in quick spasms beyond the dining-room door. The loud foolish screaming of the maid, the answering chorus of wondering ejaculations from the kitchen region, the scuttering footsteps and hurried embassies for outside help, and then, after a lull, the scared sobbings and the shuffling tread of those who bore a heavy burden into the house.

“Whoever will break it to the poor child? I couldn’t for the life of me!” exclaimed a shrill voice. And while they debated the matter among themselves, Conradin made himself another piece of toast.

Sredni Vashtar

From ‘The Chronicles of Clovis’

by Saki (H. H. Munro)

(1870 – 1916)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Saki, Saki, The Art of Reading

In 2019 jubileert Lustwarande. Delirious is de tiende expositie in De Oude Warande en de zesde overzichtseditie, met voor het merendeel nieuwe werken van vijfentwintig internationale kunstenaars.

Delirious

Jubileumeditie

15 juni – 20 oktober 2019

Opening: zaterdag 15 juni om 14.00

Evenals voorgaande overzichtsedities van Lustwarande presenteert Delirious recente ontwikkelingen in de hedendaagse sculptuur. Die recente ontwikkelingen worden gekenschetst door grote diversiteit. Naast reflecties op actuele thema’s (vloeiende identiteit, migratie, wetenschappelijke innovaties, het veranderende besef over de verhouding tussen mens en natuur, de hyperversnelling van het alledaagse leven als gevolg van nieuwe technologieën en psychologische reacties hierop) is de nadruk die er op materiaal gelegd wordt onmiskenbaar en uiterst opmerkelijk. Dit is voor een groot deel het gevolg van de sterke focus op nieuwe denkmodellen die de laatste jaren in het beeldende kunstdiscours waarneembaar is.

Evenals voorgaande overzichtsedities van Lustwarande presenteert Delirious recente ontwikkelingen in de hedendaagse sculptuur. Die recente ontwikkelingen worden gekenschetst door grote diversiteit. Naast reflecties op actuele thema’s (vloeiende identiteit, migratie, wetenschappelijke innovaties, het veranderende besef over de verhouding tussen mens en natuur, de hyperversnelling van het alledaagse leven als gevolg van nieuwe technologieën en psychologische reacties hierop) is de nadruk die er op materiaal gelegd wordt onmiskenbaar en uiterst opmerkelijk. Dit is voor een groot deel het gevolg van de sterke focus op nieuwe denkmodellen die de laatste jaren in het beeldende kunstdiscours waarneembaar is.

Het is niet verwonderlijk dat dergelijke denkkaders directe invloed hebben op de hedendaagse kunstproductie. De onophoudelijke nadruk die er op het belang van materie gelegd wordt heeft ertoe geleid dat een nieuwe generatie kunstenaars de oude filosofische vraag weer op de voorgrond gesteld heeft hoe materie ons beïnvloed en hoe wij materie beïnvloeden. In de context van voortschrijdende technologie, toenemende digitalisering, alles nivellerende globalisering en noodzakelijke herdefiniëring van ons wereldbeeld, is er hernieuwde aandacht voor de fysieke productie van beelden en voor heronderzoek naar bestaande en nieuwe materialen. Net als midden jaren ’80 van de vorige eeuw staat de huid van sculptuur opnieuw centraal, ditmaal echter in een niet eerder vertoonde mix van combinaties. Metalen, plastic, nieuwe kunststoffen, 3D prints, aarde, pigmenten, textiel, glas, klei, – en terug van weggeweest – hout en marmer en andere steensoorten en gevonden voorwerpen worden scrupuleus geassembleerd en gebricoleerd, veelal met een conceptuele inslag.

Dit vloeit niet alleen rechtstreeks voort uit bovengeschetste nieuwe theoretische modellen maar ook uit de fundamenteel veranderde eigenschappen van de hedendaagse beeldcultuur, die bijna vloeiend geworden is, uit de toenemende huidige mengmogelijkheden en uit de drang om die zowel digitaal als fysiek verder te onderzoeken, wat gepaard gaat met de noodzaak alle mogelijkheden opnieuw onder de loep te nemen, fysiek en ideologisch. En niet in de laatste plaats doordat kunstenaars een toenemende neiging ervaren zich van het beeldscherm af te wenden om weer in contact te komen met fysieke materialen. Of de kunstenaar het werk eigenhandig maakt of uitbesteedt aan producenten is daarbij van geen belang. De titel Delirious verwijst naar deze hang naar een hernieuwde fysieke sculptuurpraktijk, die zowel ongebreideld euforisch is als ook kritisch reflecterend.

Dit vloeit niet alleen rechtstreeks voort uit bovengeschetste nieuwe theoretische modellen maar ook uit de fundamenteel veranderde eigenschappen van de hedendaagse beeldcultuur, die bijna vloeiend geworden is, uit de toenemende huidige mengmogelijkheden en uit de drang om die zowel digitaal als fysiek verder te onderzoeken, wat gepaard gaat met de noodzaak alle mogelijkheden opnieuw onder de loep te nemen, fysiek en ideologisch. En niet in de laatste plaats doordat kunstenaars een toenemende neiging ervaren zich van het beeldscherm af te wenden om weer in contact te komen met fysieke materialen. Of de kunstenaar het werk eigenhandig maakt of uitbesteedt aan producenten is daarbij van geen belang. De titel Delirious verwijst naar deze hang naar een hernieuwde fysieke sculptuurpraktijk, die zowel ongebreideld euforisch is als ook kritisch reflecterend.

Deelnemende kunstenaars

Isabelle Andriessen (NL)

Nina Canell (SE)

Steven Claydon (UK)

Claudia Comte (CH)

Morgan Courtois (FR)

Hadrien Gerenton (FR)

Daiga Grantina (LV)

Siobhán Hapaska (IR)

Lena Henke (DE)

Camille Henrot (FR)

Nicholas Hlobo (SA)

Saskia Noor van Imhoff (NL)

Sven ’t Jolle (BE)

Sonia Kacem (CH)

Esther Kläs (DE)

Sarah Lucas (UK)

Justin Matherly (US)

Win McCarthy (US)

Bettina Pousttchi (DE)

Magali Reus (NL)

Jehoshua Rozenman (IL/NL)

Bojan Šarčević (FR)

Grace Schwindt (DE)

Eric Sidner (US)

Filip Vervaet (BE)

Publicatie

Publicatie

DELIRIOUS LUSTWARANDE – EXCURSIONS IN CONTEMPORARY SCULPTURE III

Ter gelegenheid van Delirious geeft Lustwarande in dit jubileumjaar de publicatie DELIRIOUS LUSTWARANDE – EXCURSIONS IN CONTEMPORARY SCULPTURE III uit. Naast documentatie van de werken in deze expositie wordt tevens documentatie van alle werken in de voorgaande vier edities (Hybrids (2018), Disruption (2017), Luster (2016) en Rapture & Pain (2015)) opgenomen. De vijf exposities samen geven een helder beeld van de stand van zaken in de hedendaagse sculptuur.

Om de exposities en de werken van een bredere context te voorzien, heeft Lustwarande drie auteurs uitgenodigd om speciaal voor deze publicatie een essay te schrijven: Dominic van den Boogerd, kunstcriticus en coördinator artistieke begeleiding en research bij De Ateliers, Amsterdam, Johan Pas, kunsthistoricus, auteur en hoofd Koninklijke Academie voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerpen, Domeniek Ruyters, kunsthistoricus en editor in chief Metropolis M, Utrecht

Locatie: park De Oude Warande

Bredaseweg 441

Tilburg

•Chris Driessen

artistiek directeur

•Heidi van Mierlo

zakelijk directeur

# meer informatie website lustwarande

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Book Stories, Art & Literature News, Art Criticism, Dutch Landscapes, Exhibition Archive, Fundament - Lustwarande, Sculpture

`Ken jij dat verhaal nog, over die koopman?’ vraagt Mels. `Het verhaal dat de juf voorlas?’

`Ik ken het nog’, zegt Tijger. `Het verhaal van de man in het zwart, die als een koopman langs de huizen ging. Als de mensen aan de deuren kwamen, lichtte hij zijn hoed, zodat ze de horentjes op zijn hoofd zagen.

`Ik ken het nog’, zegt Tijger. `Het verhaal van de man in het zwart, die als een koopman langs de huizen ging. Als de mensen aan de deuren kwamen, lichtte hij zijn hoed, zodat ze de horentjes op zijn hoofd zagen.

Niemand durfde de duivel te weigeren iets van hem te kopen. Maar wat hij te koop aanbood, maakte hen bang. Het waren lege zakken, lege dozen en holle vaten met niks erin. Voor veel geld had je niks gekocht. De duivel verkocht alleen maar lucht. Daar betaalden de mensen voor, uit angst door hem te worden meegenomen. De duivel was de patroon van de kooplui, hun leermeester en hun voorbeeld.’

`Precies, zo ging dat verhaal’, zegt Mels. `Vroeger kende ik het vanbuiten.’

`Daarin was jij beter’, geeft Tijger toe. `Je had een open oor voor verhalen. Maar met sporten was ik beter. Ik heb vaak van je gewonnen.’

`Je kon niet tegen je verlies. Erger was dat je altijd beloond wilde worden. Mijn zakmes, mijn vulpen, jij pikte het allemaal in.’

`Kleine dingen maar. Weet je nog dat we onder de brug door voeren en Lizet op de brug stond. Weet je dat ik je bij de volgende overwinning de kousenband van Lizet had willen vragen?’

`Daar was ik nooit op ingegaan’, zegt Mels een beetje driftig. `Ik kon Lizet niet uitstaan.’

`Je kon je ogen niet van haar afhouden.’

`Hou op.’

`Ik vind het niet gek dat je met haar getrouwd bent.’

`En Thija?’

`Nu denk ik dat het ook een wedstrijd was.’

`Voor jou?’

`Ja, zeker voor mij.’

`En jij zou hebben gewonnen?’

`Ik won toch altijd alles?’

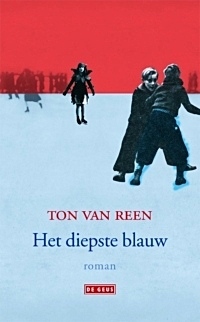

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (106)

wordt vervolgd

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

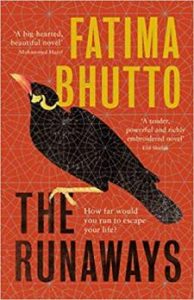

How far would you run to escape your life?

Anita lives in Karachi’s biggest slum. Her mother is a maalish wali, paid to massage the tired bones of rich women. But Anita’s life will change forever when she meets her elderly neighbour, a man whose shelves of books promise an escape to a different world.

On the other side of Karachi lives Monty, whose father owns half the city and expects great things of him. But when a beautiful and rebellious girl joins his school, Monty will find his life going in a very different direction.

On the other side of Karachi lives Monty, whose father owns half the city and expects great things of him. But when a beautiful and rebellious girl joins his school, Monty will find his life going in a very different direction.

Sunny’s father left India and went to England to give his son the opportunities he never had. Yet Sunny doesn’t fit in anywhere. It’s only when his charismatic cousin comes back into his life that he realises his life could hold more possibilities than he ever imagined.

These three lives will cross in the desert, a place where life and death walk hand in hand, and where their closely guarded secrets will force them to make a terrible choice.

‘Incredibly ambitious, extremely powerful and moving’ – BBC Radio 4

Fatima Bhutto was born in Kabul. She is the author of a book of poetry, two works of non-fiction, including her bestselling memoir Songs of Blood and Sword, and the highly acclaimed novel The Shadow Of The Crescent Moon, which was longlisted in 2014 for the Bailey’s Women’s Prize for Fiction.

Fatima Bhutto

The Runaways

Penguin Books Ltd

Imprint: Viking

Fiction

English

Published: 07/03/2019

ISBN: 9780241346990

Hardcover

Length: 432 Pages

RRP: £14.99

# new novel

Fatima Bhutto

The Runaways

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Book Stories, Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Art & Literature News, Fatima Bhutto

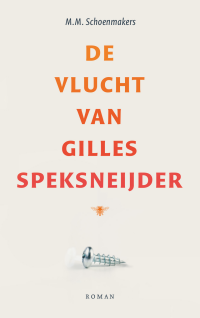

Gilles Speksneijder, een weinig uitgesproken man, bekleedt een bescheiden functie in een dienstverlenende organisatie.

Als hij van de ene op de andere dag wordt gepromoveerd tot assistentverhuiscoördinator, bezwijkt hij bijna onder zijn verantwoordelijkheden en taken. De tijdsdruk neemt toe en het verhuisproces raakt vertroebeld door machtsspelletjes, vileine roddels en complotten.

Als hij van de ene op de andere dag wordt gepromoveerd tot assistentverhuiscoördinator, bezwijkt hij bijna onder zijn verantwoordelijkheden en taken. De tijdsdruk neemt toe en het verhuisproces raakt vertroebeld door machtsspelletjes, vileine roddels en complotten.

Wanneer Gilles uit schimmige motieven een jonge vrouw meebrengt, een antikraakwacht die het verhuisproces dreigt te vertragen, verschuiven de verhoudingen in huize Speksneijder: terwijl Gilles naar de marge wordt gedrongen, neemt zijn vrouw steeds meer het heft in handen.

M.M. Schoenmakers werd geboren in Den Bosch (1949), studeerde af aan de Universiteit van Tilburg en vertrok in 1977 naar Suriname, waar hij werkte met indiaanse gemeenschappen in het binnenland. In 1989 keerde hij terug naar Nederland. Zijn Surinaamse jaren leidden tot vijf romans, die in de periode 1989-1998 bij De Bezige Bij verschenen. Na een lange stilte verscheen in 2015 opnieuw werk van zijn hand, de alom geprezen roman De wolkenridder. In februari 2019 verscheen de ontroerende en geestige roman De vlucht van Gilles Speksneijder.

Auteur: M.M. Schoenmakers

Titel: De vlucht van Gilles Speksneijder

Literaire roman

Taal: Nederlands

Paperback

256 pagina’s

Uitgever De Bezige Bij

2017

EAN 9789023454076

€ 21,99

# new novel

schoenmakers mm

de vlucht van Gilles Speksneijder

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Archive S-T, M.M. Schoenmakers

Les Remorqueurs De Macchabés

Allons, Polyte, un coup de croc:

Vois-tu comme le mec ballotte.

On croirait que c’est un poivrot

Ballonné de vin qui barbote;

Pour baigner un peu sa ribote

Il a les arpions imbibés:

Mince, alors, comme il nous dégote,

Pauv’ remorqueurs de macchabés.

Allons, Polyte, au petit trot,

Le mec a la mine pâlotte:

Il a bouffé trop de sirop;

Bientôt faudra qu’on le dorlote,

Qu’on le bichonne, qu’on lui frotte

Les quatre abatis embourbés.

Vrai, dans le métier on en rote.

Pauv’ remorqueurs de Macchabés.

Allons, Polyte, pas d’accroc,

Tu pionces plus qu’une marmotte,

Nous pinterons chez le bistro:

Le nouveau dab de la gargote

A le nez comme une carotte

Pour tous les marcs qu’il a gobés.

Un verre, ça vous ravigote,

Pauv’ remorqueurs de macchabés!

ENVOI

Prince, Polyte de la flotte,

Plus boueux que trente barbets,

Nous vivons toujours dans la crotte,

Pauv’ remorqueurs de macchabés!

Marcel Schwob

(1867-1905)

Les Remorqueurs De Macchabés

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Archive S-T, Marcel Schwob

`Knikkeren?’ vraagt Tijger.

`Knikkeren?’ vraagt Tijger.

`Heb je penningen?’

`Twee. Ik zet. Jij gooit.’

Tijger gaat op zijn kont zitten, de benen uit elkaar, de penning, met de beeltenis van de Duitse keizer, staat op zijn rand. Mels probeert hem te raken, maar alle knikkers gaan er langs. Ze rollen Tijgers broekspijpen in.

De schoolbel maakt een einde aan het spel. Fluisterend lopen ze door de gang naar het natuurkundelokaal. Binnen ruikt het naar krijt en naar de meisjes die in het uur daarvoor les hebben gehad. Meisjes krijgen altijd apart natuurkundeles, omdat ze iets moeten leren wat jongens niet mogen weten.

Juf Elsbeth zet de fles kikkervisjes op haar lessenaar en begint te praten over het wonder van de schepping. Haar stem zakt weg in het geluid van motoren buiten. De ruiten van de klas trillen van het zware gebrom van de vrachtwagens die door de slurf van de silo worden leeggezogen. Een man staat op het dak van de silo en draait met een handel de slurf hoger op. Hij schreeuwt tegen de stem van de juffrouw in. `Joehoe, joehoe!’ Niemand lijkt hem te horen. Een van de ruiten van het klaslokaal protesteert tegen het lawaai op deze zonnige middag, waarop het rustig hoort te zijn, en springt met een knal in tweeën. Splinters spatten over de leerlingen, als kleine stukjes ijs.

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (105)

wordt vervolgd

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

Le poète dans les révolutions

” Le vent chasse loin des campagnes

Le gland tombé des rameaux verts ;

Chêne, il le bat sur les montagnes ;

Esquif, il le bat sur les mers.

Jeune homme, ainsi le sort nous presse.

Ne joins pas, dans ta folle ivresse,

Les maux du monde à tes malheurs ;

Gardons, coupables et victimes,

Nos remords pour nos propres crimes,

Nos pleurs pour nos propres douleurs. “

Quoi ! mes chants sont-ils téméraires ?

Faut-il donc, en ces jours d’effroi,

Rester sourd aux cris de ses frères !

Ne souffrir jamais que pour soi !

Non, le poëte sur la terre

Console, exilé volontaire,

Les tristes humains dans leurs fers ;

Parmi les peuples en délire,

Il s’élance, armé de sa lyre,

Comme Orphée au sein des enfers.

” Orphée aux peines éternelles

Vint un moment ravir les morts ;

Toi, sur les têtes criminelles,

Tu chantes l’hymne du remords.

Insensé ! quel orgueil t’entraîne ?

De quel droit vien§-tu dans l’arène

Juger sans avoir combattu ?

Censeur échappé de l’enfance,

Laisse vieillir ton innocence,

Avant de croire à ta vertu. “

Quand le crime, Python perfide,

Brave, impuni, le frein des lois,

La Muse devient l’Euménide,

Apollon saisit son carquois.

Je cède au Dieu qui me rassure ;

J’ignore à ma vie encor pure

Quels maux le sort veut attacher ;

Je suis sans orgueil mon étoile ;

L’orage déchire la voile

La voile sauve le nocher.

” Les hommes vont aux précipices.

Tes chants ne les sauveront pas.

Avec eux, loin des cieux propices,

Pourquoi donc égarer tes pas ?

Peux-tu, dès tes jeunes années,

Sans briser d’autres destinées,

Rompre la chaîne de tes jours ?

Épargne ta vie éphémère :

Jeune homme, n’as-tu pas de mère ?

Poëte, n’as-tu pas d’amours ? “

Eh bien, à mes terrestres flammes,

Si je meurs, les cieux vont s’ouvrir.

L’amour chaste agrandit les âmes,

Et qui sait aimer sait mourir.

Le poëte, en des temps de crime,

Fidèle aux justes qu’on opprime,

Célèbre, imite les héros ;

Il a, jaloux de leur martyre,

Pour les victimes une lyre,

Une tête pour les bourreaux.

” On dit que jadis le poëte,

Chantant des jours encor lointains,

Savait à la terre inquiète

Révéler ses futurs destins.

Mais toi, que peux-tu pour le monde ?

Tu partages sa nuit profonde ;

Le ciel se voile et veut punir ;

Les lyres n’ont plus de prophète,

Et la Muse, aveugle et muette,

Ne sait plus rien de l’avenir ! “

Le mortel qu’un Dieu même anime

Marche à l’avenir, plein d’ardeur ;

C’est en s’élançant dans l’abîme

Qu’il en sonde la profondeur.

Il se prépare au sacrifice ;

Il sait que le bonheur du vice

Par l’innocent est expié ;

Prophète à son jour mortuaire,

La frison est son sanctuaire,

Et l’échafaud est son trépied.

” Que n’est-tu né sur les rivages

Des Abbas et des Cosroës,

Aux rayons d’un ciel sans nuages,

Parmi le myrte et l’aloès !

Là, sourd aux maux que tu déplores,

Le poëte voit ses aurores

Se lever sans trouble et sans pleurs ;

Et la colombe, chère aux sages,

Porte aux vierges ses doux messages

Où l’amour parle avec des fleurs ! “

Qu’un autre au céleste martyre

Préfère un repos sans honneur !

La gloire est le but où j’aspire ;

On n’y va point par le bonheur.

L’alcyon, quand l’océan gronde,

Craint que les vents ne troublent l’onde

Où se berce son doux sommeil ;

Mais pour l’aiglon, fils des orages,

Ce n’est qu’à travers les nuages

Qu’il prend son vol vers le soleil !

Victor Hugo

(1802-1885)

Le poète dans les révolutions

(Poème)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Archive G-H, Hugo, Victor, Victor Hugo

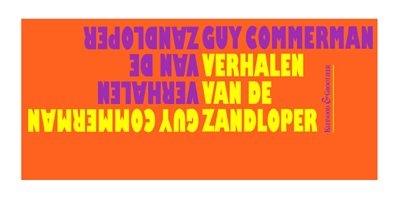

Guy Commerman, een hoog gewaardeerde auteur bij Uitgeverij Kleinood & Grootzeer is op 10 januari 2019 overleden.

Juist op dat moment was zijn nieuwe bundel: Verhalen van de zandloper, voltooid. De bundel bevat zijn laatste gedichten en is tevens een eerbetoon aan deze veelzijdige dichter en aimabel mens.

Guy Commerman (1938 – 2019)

Verhalen van de zandloper

De derde bundel van Guy Commerman bij Kleinood & Grootzeer

Eerste druk 100 genummerde en door de auteur gesigneerde exemplaren. Boekje, 62 pagina’s,

gelijmd 21 x 10,5 cm.

ISBN/EAN 978-90-76644-93-6

€18,-

# Meer informatie bij Uitgeverij Kleinood & Grootzeer

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #Editors Choice Archiv, - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive C-D, Archive C-D, Art & Literature News, In Memoriam, LITERARY MAGAZINES

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature