Fleurs du Mal Magazine

.jpg)

G U I D O G E Z E L L E

(1830-1899)

O! ‘t ruischen van het ranke riet!

O! ‘t ruischen van het ranke riet!

o wist ik toch uw droevig lied!

wanneer de wind voorbij u voert

en buigend uwe halmen roert,

gij buigt, ootmoedig nijgend, neer,

staat op en buigt ootmoedig weêr,

en zingt al buigen ‘t droevig lied,

dat ik beminne, o ranke riet!

O! ‘t ruischen van het ranke riet!

hoe dikwijls dikwijls zat ik niet

nabij den stillen waterboord,

alleen en van geen mensch gestoord,

en lonkte ‘t rimpelend water na,

en sloeg uw zwakke stafjes ga,

en luisterde op het lieve lied,

dat gij mij zongt, o ruischend riet!

O! ‘t ruischen van het ranke riet!

hoe menig mensch aanschouwt u niet

en hoort uw’ zingend’ harmonij,

doch luistert niet en gaat voorbij!

voorbij alwaar hem ‘t herte jaagt,

voorbij waar klinkend goud hem plaagt;

maar uw geluid verstaat hij niet,

o mijn beminde ruischend riet!

Nochtans, o ruischend ranke riet,

uw stem is zo verachtelijk niet!

God schiep den stroom, God schiep uw stam,

God zeide: "Waait!…" en ‘t windtje kwam,

en ‘t windtje woei, en wabberde om

uw stam, die op en neder klom!

God luisterde… en uw droevig lied

behaagde God, o ruischend riet!

O neen toch, ranke ruischend riet,

mijn ziel misacht uw tale niet;

mijn ziel, die van den zelven God

‘t gevoel ontving, op zijn gebod,

‘t gevoel, dat uw geruisch verstaat,

wanneer gij op en neder gaat:

o neen, o neen toch, ranke riet,

mijn ziel misacht uw tale niet!

O! ‘t ruischen van het ranke riet

weergalleme in mijn droevig lied,

en klagend kome ‘t voor uw voet,

Gij, die ons beiden leven doet!

o Gij, die zelf de kranke taal

bemint van enen rieten staal,

verwerp toch ook mijn klachte niet:

ik! arme, kranke, klagend riet!

Het Schrijverke

(Gyrinus Natans)

O Krinklende winklende waterding

met ‘t zwarte kabotseken aan,

wat zien ik toch geren uw kopke flink

al schrijven op ‘t waterke gaan!

Gij leeft en gij roert en gij loopt zo snel,

al zie ‘k u noch arrem noch been;

gij wendt en gij weet uwen weg zo wel,

al zie ‘k u geen ooge, geen één.

Wat waart, of wat zijt, of wat zult gij zijn?

Verklaar het en zeg het mij, toe!

Wat zijt gij toch, blinkende knopke fijn,

dat nimmer van schrijven zijt moe?

Gij loopt over ‘t spegelend water klaar,

en ‘t water niet meer en verroert

dan of het een gladdige windtje waar,

dat stille over ‘t waterke voert.

o Schrijverkes, schrijverkes, zegt mij dan, –

met twintigen zijt gij en meer,

en is er geen een die ‘t mij zeggen kan: –

Wat schrijft en wat schrijft gij zo zeer?

Gij schrijft, en ‘t en staat in het water niet,

gij schrijft, en ‘t is uit en ‘t is weg;

geen christen en weet er wat dat bediedt:

och, schrijverke, zeg het mij, zeg!

Zijn ‘t visselkes daar ge van schrijven moet?

Zijn ‘t kruidekes daar ge van schrijft?

Zijn ‘t keikes of bladtjes of blomkes zoet,

of ‘t water, waarop dat ge drijft?

Zijn ‘t vogelkes, kwietlende klachtgepiep,

of is ‘et het blauwe gewelf,

dat onder en boven u blinkt, zoo diep,

of is het u, schrijverken zelf?

En t krinklende winklende waterding,

met ‘t zwarte kapoteken aan,

het stelde en het rechtte zijne oorkes flink,

en ‘t bleef daar een stondeke staan:

"Wij schrijven," zoo sprak het, "al krinklen af

het gene onze Meester, weleer,

ons makend en leerend, te schrijven gaf,

één lesse, niet min nochte meer;

wij schrijven, en kunt gij die lesse toch

niet lezen, en zijt gij zo bot?

Wij schrijven, herschrijven en schrijven nog,

den heiligen Name van God!"

Abeelen

Verschgevelde abeelenboomen

liggen kangs de grachten heen,

die den ouden zandweg zoomen,

hoofd en armen afgesneên.

Sterke stammen, kon dat wezen,

gij, die, op en in den grond,

met uw’ voeten vastgevezen,

vamen diep, ondelgbaar, stondt?

Gij, die ‘t zwaar geweld der winden,

kreunende, op uw kruinen droegt;

die zoo lang den boosgezinden

wintervijand wedersloegt?

‘t Edel hoofd intweengespleten,

knoken in den grond geboord,

wie heeft ‘t al u afgebeten,

dat uw’ schoonheid toebehoort?

Spillen zie ‘k, en spanen, dragen;

splenters, uit uw hoofdgewaai;

takken uit uw’ toppen zagen,

kerven af uw’ teenen taai!

Elk komt uit en wondt en snijdt u;

raapt en rooft, met volle hand;

nu dat, omme’ en verre en wijd, uw

hooge kroone ligt in ‘t zand.

Vijandschap, aan alle zijden,

woedt om uwe ellendigheid:

heeft u ooit, in vroeger’ tijden,

vrede en vriendschap één ontzeid?

Edel volk, wanneer gij wachttet,

langs den weg, en schaduw smeet

op die, moegegaan, versmachtte ‘t

zonnevier, was ‘t iemand leed?

Iemand leed! Ach, laat mij weten

wie dat ‘t is, die, afgemat,

heeft ondankbaar neêrgezeten,

in de schaduw! Leert mij dat!

Meermaals mocht ik asem halen,

vluchten onder ‘t groene dak,

als het zweerd der zonnestralen

scherp mij in de lenden stak.

Boomen, in uw’ looverlane,

tellende, een voor een, u al,

‘s zomers, zoete abeelenbane,

zelden ik nog komen zal!

‘t Deert mij zoo! – De abeelenboomen

liggen langs de grachten heen,

die den ouden zandweg zoomen,

hals en handen afgesneên!

Guido Gezelle: Drie gedichten

kemp=mag poetry magazine

More in: Gezelle, Guido

.jpg)

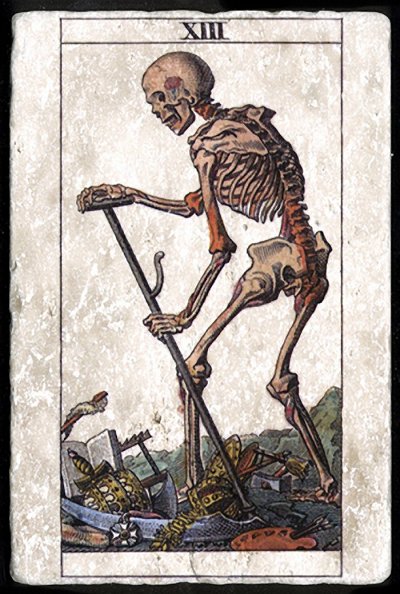

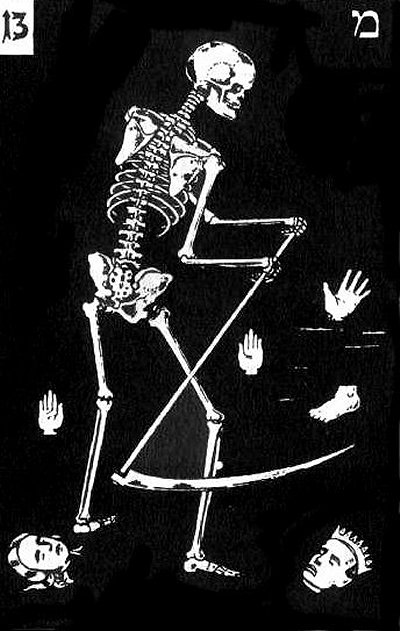

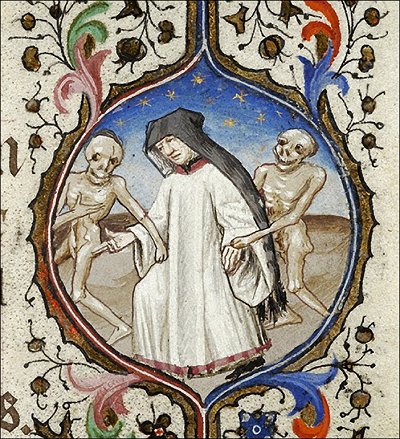

Memento Mori II

fleursdumal.nl magazine for art & literature

More in: Danse Macabre

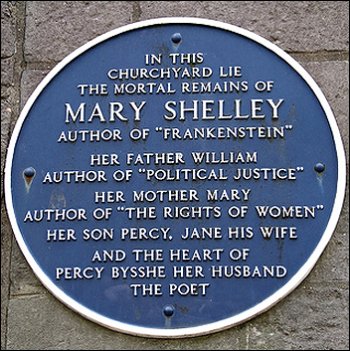

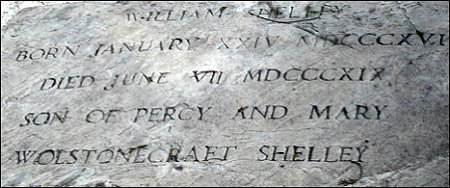

Percy Bysshe Shelley

(August 4, 1792 Horsham, England – July 8, 1822 Livorno, Italy)

Nine Poems

Death

1

They die–the dead return not–Misery

Sits near an open grave and calls them over,

A Youth with hoary hair and haggard eye–

They are the names of kindred, friend and lover,

Which he so feebly calls–they all are gone–

Fond wretch, all dead! those vacant names alone,

This most familiar scene, my pain–

These tombs–alone remain.

2

Misery, my sweetest friend–oh, weep no more!

Thou wilt not be consoled–I wonder not!

For I have seen thee from thy dwelling’s door

Watch the calm sunset with them, and this spot

Was even as bright and calm, but transitory,

And now thy hopes are gone, thy hair is hoary;

This most familiar scene, my pain–

These tombs–alone remain.

Satan broken loose

(fragment)

A golden-winged Angel stood

Before the Eternal Judgement-seat:

His looks were wild, and Devils’ blood

Stained his dainty hands and feet.

The Father and the Son

Knew that strife was now begun.

They knew that Satan had broken his chain,

And with millions of daemons in his train,

Was ranging over the world again.

Before the Angel had told his tale,

A sweet and a creeping sound

Like the rushing of wings was heard around;

And suddenly the lamps grew pale–

The lamps, before the Archangels seven,

That burn continually in Heaven.

Lines to a critic

1

Honey from silkworms who can gather,

Or silk from the yellow bee?

The grass may grow in winter weather

As soon as hate in me.

2

Hate men who cant, and men who pray,

And men who rail like thee;

An equal passion to repay

They are not coy like me.

3

Or seek some slave of power and gold

To be thy dear heart’s mate;

Thy love will move that bigot cold

Sooner than me, thy hate.

4

A passion like the one I prove

Cannot divided be;

I hate thy want of truth and love–

How should I then hate thee?

To…?

1

I fear thy kisses, gentle maiden,

Thou needest not fear mine;

My spirit is too deeply laden

Ever to burthen thine.

2

I fear thy mien, thy tones, thy motion,

Thou needest not fear mine;

Innocent is the heart’s devotion

With which I worship thine.

Song of Proserpine while gathering flowers

on the Plain of Enna

1

Sacred Goddess, Mother Earth,

Thou from whose immortal bosom

Gods, and men, and beasts have birth,

Leaf and blade, and bud and blossom,

Breathe thine influence most divine

On thine own child, Proserpine.

2

If with mists of evening dew

Thou dost nourish these young flowers

Till they grow, in scent and hue,

Fairest children of the Hours,

Breathe thine influence most divine

On thine own child, Proserpine.

Autumn: A Dirge

1

The warm sun is failing, the bleak wind is wailing,

The bare boughs are sighing, the pale flowers are dying,

And the Year

On the earth her death-bed, in a shroud of leaves dead,

Is lying.

Come, Months, come away,

From November to May,

In your saddest array;

Follow the bier

Of the dead cold Year,

And like dim shadows watch by her sepulchre.

2

The chill rain is falling, the nipped worm is crawling,

The rivers are swelling, the thunder is knelling

For the Year;

The blithe swallows are flown, and the lizards each gone

To his dwelling;

Come, Months, come away;

Put on white, black, and gray;

Let your light sisters play–

Ye, follow the bier

Of the dead cold Year,

And make her grave green with tear on tear.

Death

1

Death is here and death is there,

Death is busy everywhere,

All around, within, beneath,

Above is death–and we are death.

2

Death has set his mark and seal

On all we are and all we feel,

On all we know and all we fear,

3

First our pleasures die–and then

Our hopes, and then our fears–and when

These are dead, the debt is due,

Dust claims dust–and we die too.

4

All things that we love and cherish,

Like ourselves must fade and perish;

Such is our rude mortal lot–

Love itself would, did they not.

To the moon

1

Art thou pale for weariness

Of climbing heaven and gazing on the earth,

Wandering companionless

Among the stars that have a different birth,–

And ever changing, like a joyless eye

That finds no object worth its constancy?

2

Thou chosen sister of the Spirit,

That grazes on thee till in thee it pities…

Sonnet

Ye hasten to the grave! What seek ye there,

Ye restless thoughts and busy purposes

Of the idle brain, which the world’s livery wear?

O thou quick heart, which pantest to possess

All that pale Expectation feigneth fair!

Thou vainly curious mind which wouldest guess

Whence thou didst come, and whither thou must go,

And all that never yet was known would know–

Oh, whither hasten ye, that thus ye press,

With such swift feet life’s green and pleasant path,

Seeking, alike from happiness and woe,

A refuge in the cavern of gray death?

O heart, and mind, and thoughts! what thing do you

Hope to inherit in the grave below?

Percy Bysshe Shelley: Nine Poems

• fleursdumal.nl magazine for art & literature

More in: Archive S-T, Archive S-T, Percy Byssche Shelley, Shelley, Percy Byssche

Tentoonstelling Vodou,

kunst & mystiek

31 oktober 2008 t/m 10 mei 2009

T r o p e n m u s e u m A m s t e r d a m

Bezoekers van het Tropenmuseum kunnen deze winter kennismaken met vodou: de volksreligie van Haïti. Meer dan 250 (kunst)voorwerpen geven een beeld van de intrigerende goden- en geestenwereld van vodou. Ze zijn gemaakt voor vodou-tempels en geheime genootschappen. De objecten maken deel uit van de belangrijkste vodou-collectie van Haïti: de privé verzameling van Marianne Lehmann. Veel van deze voorwerpen zijn nog nooit buiten Haïti getoond.

Kleurrijke ceremoniële vlaggen, levensgrote Bizango-krijgers, reusachtige spiegels en complete altaren zijn in de tentoonstelling te zien. De bezoeker van het Tropenmuseum maakt kennis met een religie die rijk is aan historie en traditie, met unieke rituelen en fascinerende kunstvoorwerpen. De expositie laat vodou zien op een indringende manier, die voorbij gaat aan de extreme clichébeelden van Hollywood.

De volksreligie vodou ontstond met de onvrijwillige vestiging van Afrikaanse slaven op Haïti. Vodou is een mengeling van verschillende door hen meegenomen Afrikaanse religies, aangevuld met aspecten van katholieke rites. Als geloof van de massa’s en de onderdrukten heeft vodou een cruciale rol gespeeld in de geschiedenis van Haïti, vanaf de eerste slavenopstand die het in 1804 tot een onafhankelijke zwarte republiek maakte, tot aan de dag van vandaag. Ondanks lange periodes van onderdrukking is vodou een levende religie gebleven, beleden door miljoenen Haïtianen in Haïti en daarbuiten. Het is een complexe maar ook flexibele religie zonder dogma of hiërarchie die haar gelovigen veel vrijheden biedt, ook op artistiek gebied.

Een groot deel van de expositie in het Tropenmuseum is gewijd aan de beelden en voorwerpen van geheime Bizango-genootschappen. Deze gaan terug tot de tijd van slavernij en de gewelddadige vrijheidsstrijd. De levensgrote beelden die tientallen Bizango-geesten verbeelden, herinneren op beklemmende wijze aan deze oorsprong van chaos en strijd, en zijn tegelijkertijd indrukwekkend door hun artistieke waarde.

Bijna alle objecten in de tentoonstelling zijn gewijd aan de Lwa’s: de talloze goden en geesten die het vodou-pantheon bevolken. Vaak worden deze Lwa’s uitgebeeld als de katholieke heiligen met wie ze geïdentificeerd worden. Lwa’s worden ook weergegeven door vévé’s: grafische tekens. De geborduurde vlaggen, sculpturen, bewerkte kruiken en spiegels hebben zelf vaak een sacrale betekenis of zijn ‘geladen’ met magische krachten.

De rijk geïllustreerde tentoonstellingscatalogus ‘Vodou, kunst & mystiek uit Haïti’ is samengesteld door Jacques Hainard, Philippe Mathez en Olivier Schinz en wordt uitgegeven door KIT Publishers. ISBN 9789068327441, € 24,50, 176 pagina’s.

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: African Art, Tales of Mystery & Imagination

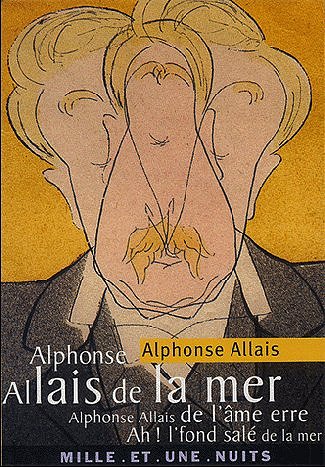

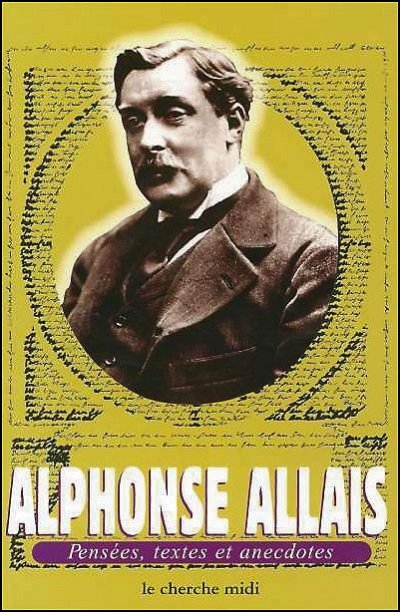

A l p h o n s e A l l a i s

(1854-1905)

Complainte Amoureuse

Oui dès l’instant que je vous vis

Beauté féroce, vous me plûtes

De l’amour qu’en vos yeux je pris

Sur-le-champ vous vous aperçûtes

Ah ! Fallait-il que vous me plussiez

Qu’ingénument je vous le dise

Qu’avec orgueil vous vous tussiez

Fallait-il que je vous aimasse

Que vous me désespérassiez

Et qu’enfin je m’opiniâtrasse

Et que je vous idolâtrasse

Pour que vous m’assassinassiez

Poem of the week – November 16, 2008

kemp=mag poetry magazine – magazine for art & literature

More in: Archive A-B

.jpg)

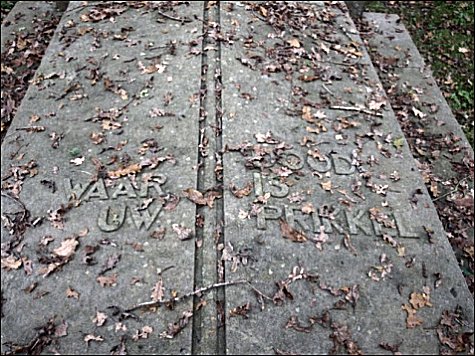

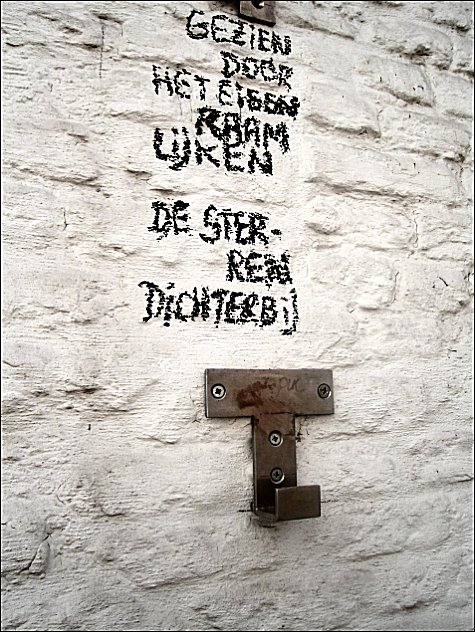

Joep Eijkens Photos

Dood waar is uw prikkel – I

fleursdumal.nl magazine – magazine for art & literature

Joep Eijkens Photos: Dood waar is uw prikkel – I

© J. Eijkens

More in: Galerie des Morts, Joep Eijkens Photos

Ed Schilders

De strepen van John Keats

Er is een hardnekkig misverstand dat zegt, dat schrijven en strepen in een boek niet mag. Dat dat zoiets is als het papier striemen, of, nog erger, een vorm van lezers-onanie: een geperverteerde vorm van leesgedrag.

Daar is iets voor te zeggen, maar niet alles. Tenslotte zijn het de eigen boeken, bestemd voor de eigen ogen en gedachten, dus wie wil strepen of schrijven, die gaat zijn gang (zij het met inachtneming van het te hanteren schrijfmateriaal). En dan? Als de streper dood is en zijn boeken door de erfgenamen verkwanseld worden omdat ze meer van bankpapier houden? Juist dan worden strepen en margeschrifturen belangrijk. Het enige probleem dat ik met bestreepte boeken uit de tweede hand heb, is dat ik zelden te weten kan komen wie voor de lezersaccenten gezorgd heeft. Het ex-libris of het ex-bibliotheca is in onbruik geraakt, en namen op schutbladen is hoogst onvoldoende. Lezers zouden er minstens een gewoonte van moeten maken het boek te voorzien van jaartallen, en een korte indruk op een ingeplakt velletje papier. Zo zou je de 120 Dagen van Sodom van een staatssecretaris kunnen kopen, of de Gedachten van Leopardi van een taxichauffeur uit Lisse, beide werken voorzien van uitroeptekens in de marge. Oude boeken hebben een stamboom, en de lezer kan bijdragen aan de genealogie.

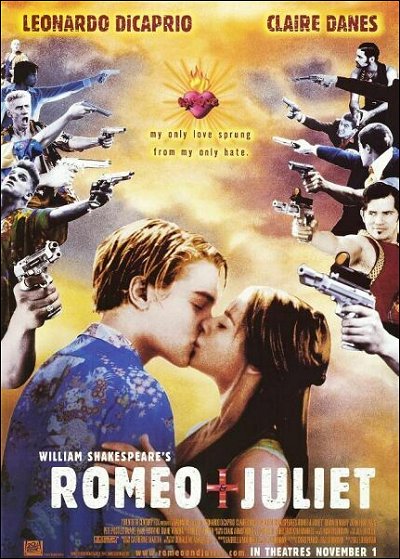

Het enige boek (in mijn kast) dat over een boek met onderstrepingen gaat, is Keats’s Shakespeare van Caroline Spurgeon (Oxford University Press, 1928). De titel zegt het al: Spurgeon onderzocht de Shakespeare-uitgave die John Keats bezat op potloodstrepen, doorhalingen en bijschriften, en vergeleek die passages met het werk van Keats zelf. Een groot deel van het boek is een nauwkeurige weergave van die pagina’s, met daarbij een voorbeeld hoe Keats zich liet inspireren door de gelezen tekst.

Die inspiratie blijkt met name in Endymion zo overweldigend te zijn dat sommigen zouden beweren dat Keats The Tempest en A Midsummer Night’s Dream geplagieerd heeft. Zo lees je niet alleen, en tegelijkertijd Spurgeon, Shakespeare en Keats, maar ook hoe Keats Shakespeare las, en hoe Spurgeon las hoe Keats Shakespeare gelezen heeft.

Vanavond knip ik dit artikel uit en zal ik het netjes en met deugdelijke lijm, in Spurgeons boek plakken. De stamboom van dit boek zal daarmee weer wat groter zijn geworden want het bevat al aardige sporen van mijn vóórlezers. Het is een bibliotheekexemplaar geweest (tussen 1935 en 1937 achtmaal uitgeleend). Toen werd het weggeschonken, en wel door het Canadian Book Centre uit Halifax. Het kwam terecht in het Moederhuis van de fraters in Tilburg dat er zijn ex-libris inplakte, en vervolgens in de centrale bibliotheek die het bestempelde. Dat de oorspronkelijke bibliotheek de Public Library van Toronto is geweest, weet ik omdat men daar met een gaatjestang de naam in de titelpagina heeft geperforeerd en op iedere prent — foto’s van de pagina’s met de strepen van Keats — een klein rond stempeltje gezet heeft om de terreur van de uitscheurders te bestrijden. Ze zijn trouwens toch heel zuinig op boeken in Toronto. Hun ex-libris wordt ten dele aan het oog onttrokken door dat van de fraters, maar de gekalligrafeerde tekst die ik nog kan lezen, zegt in vertaling: “De bibliothecaris zal ieder teruggebracht boek onderzoeken, en als hetzelfde gemarkeerd of met inkt bevlekt is, de pagina’s omgevouwen zijn, of het anderszins beschadigd is, zal de lener de waarde van het boek betalen.” Zo pak je leners aan, maar voor lezers blijft zoiets toch wel heel opmerkelijk in een boek over onderstrepingen.

.jpg)

Spurgeons boek heeft onder het frontispiece van een lezende Keats een citaat uit een van zijn brieven. “Te weten in welke houding Shakespeare zat toen hij “To be or not to be” begon op te schrijven, zoiets wordt interessant door de afstand in tijd en plaats.” Twee alinea’s hoger heeft Keats beschreven in welke houding hijzelf op dat moment zat: met de rug naar het haardvuur, aan één voet op het tapijt, de andere met de hiel enigszins opgetild. “Ik schrijf dit met “The Maid’s Tragedy”” als ondergrond, dat ik na de lunch met veel plezier gelezen heb.” Even lijkt het of hier niets anders aan de hand is dan bladvulling en behoefte aan Shakespeare, maar het toeval wil meer.

“The Maid’s Tragedy”, werd geschreven door Francis Beaumont en John Fletcher. Hun literaire samenwerking wordt geoordeeld het fraaiste toneelwerk te hebben opgeleverd op de stukken van hun tijdgenoot Shakespeare na. Beiden figureren bovendien in studies omtrent de ware identiteit van de schrijver die ‘Shakespeare’ genoemd wordt, maar van wie we geen portret hebben, geen biografie, laat staan dat we weten hoe hij achter zijn schrijftafel zat. En wat gebruikte hij als ondergrond? Met name Fletcher wordt geacht te hebben samengewerkt met Shakespeare, of Shakespeare wordt geacht bij Fletcher de inspiratie te hebben gevonden voor “Hendrik VIII”, zoals Keats zijn inspiratie vond voor “Endymion”. Strepend?

Het zoeken naar de ware biografie van Shakespeare heeft een kleine kast vol aardige, curieuze werken opgeleverd. Bacon, Essex, Raleigh, Edward de Vere, en Lord Rutland zijn de bekendste identiteiten die aan de dichter uit Stratford gegeven zijn.

Het is duidelijk dat historisch onderzoek en filologische listen de oplossing van het Shakespeare-raadsel niet meer zullen brengen. Er is, denk ik, een laatste kans. Als Shakespeare zoveel inspiratie opdeed bij andere auteurs, dan zal hij, net als Keats, ook veel gestreept hebben. Willen we ooit te weten komen wie hij was, en hoe hij zat, dan zullen we niet naar zijn verloren persoonsbewijs of zijn verdwenen manuscripten moeten zoeken maar naar de boeken die hij in zijn kast had. Naar de werken die hij las, waarin hij streepte en in de marge schreef.

.jpg)

Ed Schilders: De Strepen van John Keats

© E. Schilders

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Stories, BOOKS. The final chapter?, Ed Schilders, John Keats, Keats, John

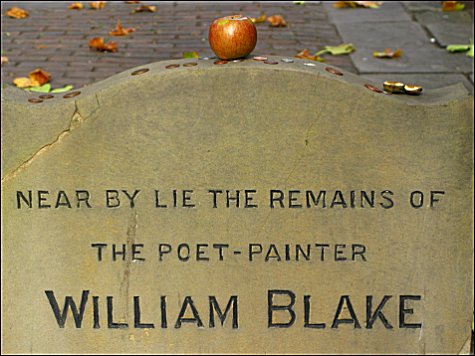

.jpg)

GALERIE DES MORTS IV

Bunhill Fields Cemetery London

Photos Anton K.

© kemp=mag poetry magazine

magazine for art & literature

More in: Galerie des Morts

William Shakespeare

(1564-1616)

F i v e S o n n e t s

20

A woman’s face with nature’s own hand painted,

Hast thou the master mistress of my passion,

A woman’s gentle heart but not acquainted

With shifting change as is false women’s fashion,

An eye more bright than theirs, less false in rolling:

Gilding the object whereupon it gazeth,

A man in hue all hues in his controlling,

Which steals men’s eyes and women’s souls amazeth.

And for a woman wert thou first created,

Till nature as she wrought thee fell a-doting,

And by addition me of thee defeated,

By adding one thing to my purpose nothing.

But since she pricked thee out for women’s pleasure,

Mine be thy love and thy love’s use their treasure.

31

Thy bosom is endeared with all hearts,

Which I by lacking have supposed dead,

And there reigns love and all love’s loving parts,

And all those friends which I thought buried.

How many a holy and obsequious tear

Hath dear religious love stol’n from mine eye,

As interest of the dead, which now appear,

But things removed that hidden in thee lie.

Thou art the grave where buried love doth live,

Hung with the trophies of my lovers gone,

Who all their parts of me to thee did give,

That due of many, now is thine alone.

Their images I loved, I view in thee,

And thou (all they) hast all the all of me.

36

Let me confess that we two must be twain,

Although our undivided loves are one:

So shall those blots that do with me remain,

Without thy help, by me be borne alone.

In our two loves there is but one respect,

Though in our lives a separable spite,

Which though it alter not love’s sole effect,

Yet doth it steal sweet hours from love’s delight.

I may not evermore acknowledge thee,

Lest my bewailed guilt should do thee shame,

Nor thou with public kindness honour me,

Unless thou take that honour from thy name:

But do not so, I love thee in such sort,

As thou being mine, mine is thy good report.

40

Take all my loves, my love, yea take them all,

What hast thou then more than thou hadst before?

No love, my love, that thou mayst true love call,

All mine was thine, before thou hadst this more:

Then if for my love, thou my love receivest,

I cannot blame thee, for my love thou usest,

But yet be blamed, if thou thy self deceivest

By wilful taste of what thy self refusest.

I do forgive thy robbery gentle thief

Although thou steal thee all my poverty:

And yet love knows it is a greater grief

To bear love’s wrong, than hate’s known injury.

Lascivious grace, in whom all ill well shows,

Kill me with spites yet we must not be foes.

46

Mine eye and heart are at a mortal war,

How to divide the conquest of thy sight,

Mine eye, my heart thy picture’s sight would bar,

My heart, mine eye the freedom of that right,

My heart doth plead that thou in him dost lie,

(A closet never pierced with crystal eyes)

But the defendant doth that plea deny,

And says in him thy fair appearance lies.

To side this title is impanelled

A quest of thoughts, all tenants to the heart,

And by their verdict is determined

The clear eye’s moiety, and the dear heart’s part.

As thus, mine eye’s due is thy outward part,

And my heart’s right, thy inward love of heart.

kemp=mag poetry magazine

More in: Shakespeare, William

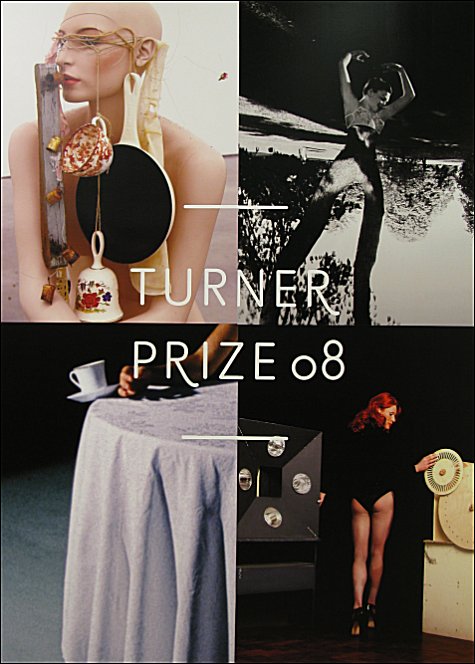

IN SEARCH OF ART: LONDON

fleursdumal.nl magazine

© Photos Anton K.

More in: FDM in London

.jpg)

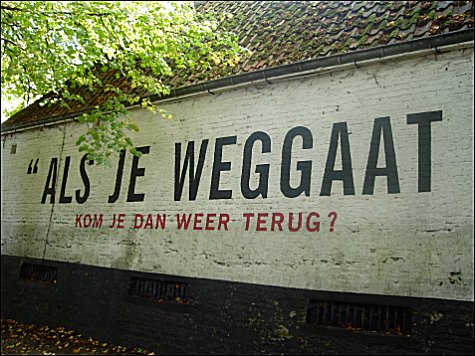

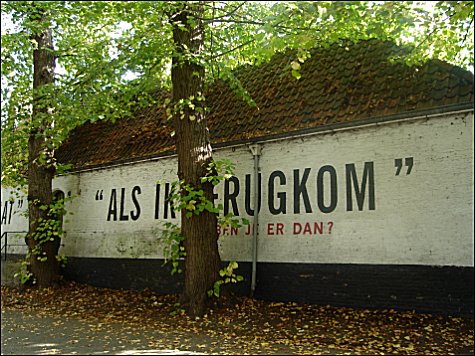

HISTORIA BELGICA

Belgian Landscapes I

Photos Kempis

© kemp=mag ► magazine for art & literature

More in: Historia Belgica

![]()

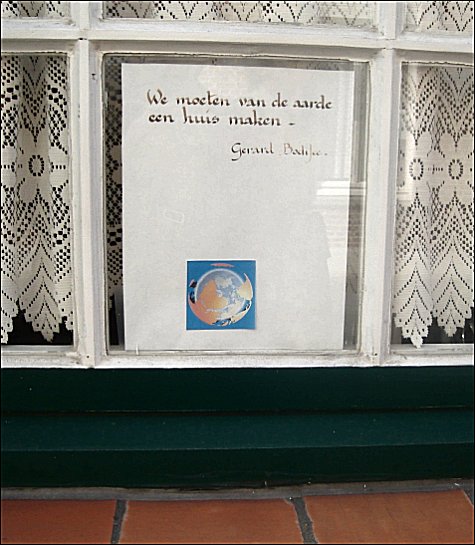

Gregor Schneider: END

The second phase of construction at

Museum Abteiberg in Mönchengladbach

Gregor Schneider’s concept for the second phase of construction at Museum Abteiberg takes the form of an over-dimensioned walk-in sculpture to be implemented as a temporary building.

Schneider’s concept envisages the museum as a black hole leading into an unknown space. The visitor enters it through a black opening. Total blackness removes all sense of place and engenders an experience of complete isolation, compelling visitors to feel their way along the walls of a corridor into total darkness, before eventually discovering a new entrance to the museum. The exhibition rooms located beyond the entrance are also entirely dark, their architecture vanishing into a black and obscure nothingness. Sensitised in this manner, visitors then enter Gregor Schneider’s innovative presentation of the museum’s collection, which includes original rooms from Haus u r.

Gregor Schneider has designed a new entrance for the Abteiberg Museum that is as monumental as it is mysterious. The huge walk-in sculpture will be erected on the lawn in front of the museum where the second part of the museum building, designed by Hans Hollein, will eventually be built. The front of the black edifice faces the vision axis of Mönchengladbach’s main shopping street. It will have a 14 x 14 meter square entrance, black both in- and outside and visible from afar, which will lead into a 70-meter long, totally dark corridor. It will extend diagonally in the shape of a tapering funnel, ending in a small, 1 x 1 meter hole that breaks through the closed museum wall and eventually reaches one of the ‘clover-leaf’ rooms in the museum interior.

The dimensions of this project both as urban architecture and a critical statement are one of its key features. This work was made possible by generous funding from the state of North-Rhine Westphalia (NRW) and the NRW Art Foundation as well as companies and private sponsors. The result is a major landmark that draws attention to what was previously a rather inconspicuous inner-city museum and endows its currently hidden entrances with new prominence. The enormous entrance tunnel, located in front of the museum on land due to become available for development, catches the eye from several perspectives including the central axis of Hindenburgstraße and the driveway from Abteistraße, virtually drawing the viewer’s gaze into itself.

Gregor Schneider and Museum Abteiberg are connected by both the locale and the concept, since Haus u r and the museum are both rooted in this city. Moreover, the ideas behind and history of Museum Abteiberg are closely associated with contemporary discourse on architectonic space. Not only Hans Hollein’s pioneering architecture, but also objects in the museum’s collection by his contemporary Gordon-Matta Clark, which were among its early acquisitions, testify to the museum’s special place in the discourse on the meaning of architecture.

It has therefore been one of the museum’s main wishes to acquire for the museum’s collection the central “Kaffee Zimmer” (Coffee Room) from Haus u r for its collection to join the “Abstellkammer” (Storeroom), which it purchased some time ago. It was equally important that the artist himself should design the installation for Museum Abteiberg. Here, Gregor Schneider further explores themes that have always been important to the museum: how to retrieve, present and communicate complex works of contemporary art that pose new challenges for museums (see also the artist’s extensive preliminary remarks: “Von der Zeit, da das immobile Haus mobil wurde” (About the time when the immobile house became mobile), interview in the June 2007 issue of Kunstforum International).

Starting from the museum’s acquisition of “Kaffeezimmer”, made possible by generous funding from the Kulturstiftung der Länder (KSL), the state of North-Rhine Westphalia and the Foundation for Culture and Science of Stadtsparkasse Mönchengladbach, Gregor Schneider designed a set of six rooms, which extend from the tunnel END inside the museum. The installation is staged in the completely darkened museum space, in which a number of rooms can be combined without having to refer to the surrounding architecture. The result is a stage-like presence, emphasising Gregor Schneider’s recent preoccupation with theatre and the importance of his film work. Alongside the illuminated original rooms, projections from Haus u r are presented together with unpublished film work that presents former villages in the nearby lignite mining fields as well as the house on Odenkirchener Straße in Rheydt (not far from Haus u r) where Joseph Goebbels was born. A further feature is the presentation of the geographical and historical origins of Schneider’s artistic discourse: the house in Rheydt and its regional vicinity, abandoned houses awaiting demolition and the landscapes of the Rhineland opencast mining industry, all traces of suppressed recent history. All these media will be used to create the “Smithsonesque” situation of a “non-site” in the museum (freely adapted from Robert Smithson’s dialectical thesis), which will be considerably enhanced by the special END entrance.

Website Museum Abteiberg Mönchengladbach

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Architecture, Exhibition Archive, Galerie Deutschland, Gregor Schneider, Sculpture

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature