Fleurs du Mal Magazine

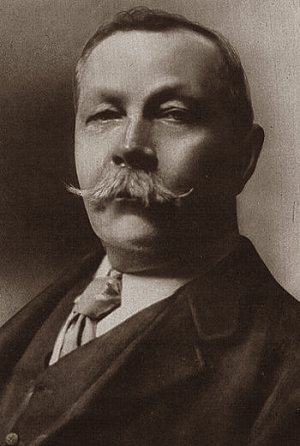

Arthur Conan Doyle

(1859-1930)

Haig is moving

August 1918

Haig is moving!

Three plain words are all that matter,

Mid the gossip and the chatter,

Hopes in speeches, fears in papers,

Pessimistic froth and vapours–

Haig is moving!

Haig is moving!

We can turn from German scheming,

From humanitarian dreaming,

From assertions, contradictions,

Twisted facts and solemn fictions–

Haig is moving!

Haig is moving!

All the weary idle phrases,

Empty blamings, empty praises,

Here’s an end to their recital,

There is only one thing vital–

Haig is moving!

Haig is moving!

He is moving, he is gaining,

And the whole hushed world is straining,

Straining, yearning, for the vision

Of the doom and the decision–

Haig is moving!

Arthur Conan Doyle poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: *War Poetry Archive, Archive C-D, Arthur Conan Doyle, Doyle, Arthur Conan

Gustave Flaubert

(1821-1880)

DICTIONNAIRE DES IDÉES REÇUES (R-S)

R

RACINE: Polisson!

RADEAU: Toujours de la Méduse.

RADICALISME: D’autant plus dangereux qu’il est latent. La république nous mène au radicalisme.

RAMONEUR: Hirondelle de l’hiver.

RATE: Autrefois, on l’enlevait au coureur.

RATELIER: Troisième dentition. Prendre garde de l’avaler en dormant.

RECONNAISSANCE: N’a pas besoin d’être exprimée.

RELIGION (la): Fait partie des bases de la société. Est nécessaire pour le peuple, cependant pas trop n’en faut. «La religion de nos pères» , doit se dire avec onction.

RÉPUBLICAINS: Les républicains ne sont pas tous des voleurs, mais les voleurs sont tous républicains.

RESTAURANT: On doit toujours y demander les mets qu’on ne mange pas habituellement chez soi. Quand on est embarrassé, il suffit de choisir les plats que l’on sert aux voisins.

RÊVASSERIE: Les idées élevées qu’on ne comprend pas.

RÉVEILLON: C’est le boudin qui constitue le réveillon.

RICHESSE: Tient lieu de tout, même de considération.

RIME: Ne s’accorde jamais avec la raison.

RINCE-BOUCHE: Signe de richesse dans une maison.

RIRE: Toujours homérique.

ROBE: Inspire le respect.

ROMANCES: Le chanteur de romances plaît aux dames.

ROMANS: Pervertissent les masses. Sont moins immoraux en feuilletons qu’en volumes. Seuls les romans historiques peuvent être tolérés parce qu’ils enseignent l’histoire. Il y a des romans écrits avec la pointe d’un scalpel, d’autres qui reposent sur la pointe d’une aiguille.

RONSARD: Ridicule avec ses mots grecs et latins.

ROUSSEAU: Croire que J. -J. Rousseau et J. -B. Rousseau sont les deux frères, comme l’étaient les deux Corneille.

ROUSSES: V. blondes, brunes et négresses.

RUINES: Font rêver et donnent de la poésie à un paysage.

S

SABOTS: Un homme riche qui a eu des commencements difficiles est toujours venu à Paris en sabots.

SABRE: Les Français veulent être gouvernés par le sabre.

SACERDOCE: L’art, la médecine, etc. , sont des sacerdoces.

SACRILÈGE: C’est un sacrilège d’abattre un arbre.

SAIGNER: Se faire saigner au printemps.

SAINT-BARTHÉLEMY: Vieille blague.

SAINTE-BEUVE: Le Vendredi Saint, dînait exclusivement de charcuterie.

SAINTE-HÉLÈNE: Ile connue par son rocher.

SALIÈRE: La renverser porte malheur.

SALON (faire le): Début littéraire qui pose très bien son homme.

SALUTATIONS: toujours empressées.

SANTÉ: trop de santé, cause de maladie.

SAPHIQUE ET ADONIQUE (vers): Produit un excellent effet dans un article de littérature.

SATRAPE: Homme riche et débauché.

SATURNALES: Fêtes du Directoires.

SAVANTS: Les blaguer. Pour être savant, il ne faut que de la mémoire et du travail.

SBIRE: S’emploie par les Républicains farouches pour désigner les agents de police.

SCIENCE: Un peu de science écarte de la religion et beaucoup y ramène.

SCUDÉRY: On doit le blaguer, sans savoir si c’était un homme ou une femme.

SÉNÈQUE: Ecrivait sur un pupitre d’or.

SERPENT: Tous venimeux.

SERVICE: C’est rendre service aux enfants que de les calotter; aux animaux que de les battre; aux domestiques, que de les chasser; aux malfaiteurs, que de les punir.

SÉVILLE: Célèbre endroit pour son barbier. Voir Séville et mourir! (v. Naples).

SITE: Endroits pour faire des vers.

SOCIÉTÉ: Ses ennemis. Ce qui cause sa perte.

SOMBREUIL (Mlle de): rappeler le verre de sang.

SOMMEIL: Epaissit le sang.

SOUFFLET: Ne jamais s’en servir.

SOMNAMBULE: Se promène la nuit sur la crête des toits.

SOUPERS DE LA RÉGENCE: On y dépensait encore plus d’esprit que de champagne.

SOUPIR: Doit s’exhaler près d’une femme.

SPIRITUALISME: Le meilleur système de philosophie.

STOÏCISME: Est impossible.

STUART (MARIE): S’apitoyer sur son sort.

SUFFRAGE UNIVERSEL: Dernier terme de la science politique.

SUICIDE: Preuve de lâcheté.

SYBARITES: Tonner contre.

SYPHILIS: Plus ou moins, tout le monde en est affecté.

Gustave Flaubert

DICTIONNAIRE DES IDÉES REÇUES (R-S)

(Oeuvre posthume: publication en 1913)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: - Dictionnaire des idées reçues, DICTIONARY OF IDEAS

Ton van Reen

DE MOORD XXVI

Langs de muren van de werkplaats stonden speelgoeddieren uit vergeeld varkensleer. Paardjes, hondjes, katjes en weet ik wat al meer. Ik had wat tegen dode beesten. Ik kon geen vlees eten van een beest dat ik had zien sterven. Ik heb nooit kunnen verdragen dat een slager zijn pistool tegen de kop van een varken zette en de hersens kapotschoot. Of dat men een varken keelde. Ik heb eens toe moeten zien hoe vier kerels op een varken zaten om het stil te houden, een vijfde boorde in het varkenslijf, met een groot stalen mes, om het hart te zoeken en het bloed op te kunnen vangen. Ik heb eens gedroomd van vijf varkens die een slager keelden. Vier varkens zaten op de rug van de slager. Het vijfde sneed gaten in het lijf van de schreeuwende slager die niet sterven kon omdat hij geen hart had. En wat ik allemaal zag bij het opzetten van beesten! De beesten van deze schoenmaker waren niet opgezet. Die waren echt. Ze waren van varkensleer. Paardjes van echt varkensleer. Aapjes van echt varkensleer. De hele varkensleren ark van Noach liep leeg. Twee aan twee kwamen de varkensleren dieren naar buiten. Niemand zou kunnen zien wie van elk stel het mannetje was en wie het wijfje. Ook Noach was van varkensleer. En zijn vrouw. En zijn zonen. En hun vrouwen. Allemaal waren ze van varkensleer. Het was opvallend hoe goed de huid van een varken paste in de gezichten van de mensen. Opvallend hoe Noach leek op de schoenmaker.

Later reden we met de bus terug naar Wrak. Reden over de brug van Kork, kwamen door Tepple, het Tepple van de forensen. We zaten achter in de bus, en zoals ik wel verwachtte, op de bank voor me zat de oude man die op een mijn van de partizanen was gelopen. Tussen Tepple en Wrak sloeg hij de vrede in de bus weer aan scherven door aan de noodrem te trekken en een verhaal over partizanen te vertellen. Zijn gal bereikte opnieuw de chauffeur. Die hield zich echter koest omdat hij een van de partizanen was geweest.

Alice had de rest van de dag geen zin meer in spelletjes. Ik bleef naar de melker kijken die met zijn harde vingernagels vormloze figuurtjes sneed in het hout van het tafelblad. Het waren allemaal dieren die hij maakte.

(wordt vervolgd)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: - De moord

No Slick Shit:

Een nomadisch podium voor kuren met ongelijke leggers

No SlickShit biedt levens verfrissende guerrilla keutels met een gouden randje.

De eerste editie vindt plaats op 16 februari. Op het affiche staan de bands El Cantina, Ivo van Leeuwen, Betonfraktion en Zibabu. Ad Fijneman exposeert schilderijen. Machinery presenteert een live art performance. Auteur A.H.J. Dautzenberg draagt voor. Ook wordt de winnaar bekend gemaakt van de No Slick ShitVideo Contest: ‘Go For The Golden Turd’.

No Slick Shit 16 februari 2013

We beginnen om 19.00 uur Stipt. Wie niets wil missen komt op tijd in Cafe Little devil, stationstraat nummer nog wat, Tilburg.

Programma:

Openingswoord door Nick (J. Swarth)

El Cantina

Anton Dautzenberg

Betonfraktion

Uitreiking Golden Turd

Machinery

Zibabu

Disco Goof

Disco Little Devil

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Betonfraction, Ivo van Leeuwen, The talk of the town

Mijn stad

Nu speelt men hier de

nazomerkoning miauwt

men tegen muren of raast

in een richting door over

de cityring elk mooi oud

gebouw slopen we direct

maakt niet uit over veertig

jaar staat hier de toekomst

de lindeboom een hologram

de stadsheer verpauperd

verpulverd met de grond

gelijk bewoners op straat

Dit lijkt wel mijn stad

we proberen eens wat en

tonen vooral niet teveel

gevoel zo gewend reeds

aan afbraak dat melancholie

is als overrijp fruit in een

stilleven het ziet er nog uit

maar het begint meer en

meer te rotten.

Martin Beversluis

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Beversluis, Martin

Jack London

(1876-1916)

When Alice told her soul

This, of Alice Akana, is an affair of Hawaii, not of this day, but

of days recent enough, when Abel Ah Yo preached his famous revival

in Honolulu and persuaded Alice Akana to tell her soul. But what

Alice told concerned itself with the earlier history of the then

surviving generation.

For Alice Akana was fifty years old, had begun life early, and,

early and late, lived it spaciously. What she knew went back into

the roots and foundations of families, businesses, and plantations.

She was the one living repository of accurate information that

lawyers sought out, whether the information they required related

to land-boundaries and land gifts, or to marriages, births,

bequests, or scandals. Rarely, because of the tight tongue she

kept behind her teeth, did she give them what they asked; and when

she did was when only equity was served and no one was hurt.

For Alice had lived, from early in her girlhood, a life of flowers,

and song, and wine, and dance; and, in her later years, had herself

been mistress of these revels by office of mistress of the hula

house. In such atmosphere, where mandates of God and man and

caution are inhibited, and where woozled tongues will wag, she

acquired her historical knowledge of things never otherwise

whispered and rarely guessed. And her tight tongue had served her

well, so that, while the old-timers knew she must know, none ever

heard her gossip of the times of Kalakaua’s boathouse, nor of the

high times of officers of visiting warships, nor of the diplomats

and ministers and councils of the countries of the world.

So, at fifty, loaded with historical dynamite sufficient, if it

were ever exploded, to shake the social and commercial life of the

Islands, still tight of tongue, Alice Akana was mistress of the

hula house, manageress of the dancing girls who hula’d for royalty,

for luaus (feasts), house-parties, poi suppers, and curious

tourists. And, at fifty, she was not merely buxom, but short and

fat in the Polynesian peasant way, with a constitution and lack of

organic weakness that promised incalculable years. But it was at

fifty that she strayed, quite by chance of time and curiosity, into

Abel Ah Yo’s revival meeting.

Now Abel Ah Yo, in his theology and word wizardry, was as much

mixed a personage as Billy Sunday. In his genealogy he was much

more mixed, for he was compounded of one-fourth Portuguese, one-

fourth Scotch, one-fourth Hawaiian, and one-fourth Chinese. The

Pentecostal fire he flamed forth was hotter and more variegated

than could any one of the four races of him alone have flamed

forth. For in him were gathered together the cannyness and the

cunning, the wit and the wisdom, the subtlety and the rawness, the

passion and the philosophy, the agonizing spirit-groping and he

legs up to the knees in the dung of reality, of the four radically

different breeds that contributed to the sum of him. His, also,

was the clever self-deceivement of the entire clever compound.

When it came to word wizardry, he had Billy Sunday, master of slang

and argot of one language, skinned by miles. For in Abel Ah Yo

were the five verbs, and nouns, and adjectives, and metaphors of

four living languages. Intermixed and living promiscuously and

vitally together, he possessed in these languages a reservoir of

expression in which a myriad Billy Sundays could drown. Of no

race, a mongrel par excellence, a heterogeneous scrabble, the

genius of the admixture was superlatively Abel Ah Yo’s. Like a

chameleon, he titubated and scintillated grandly between the

diverse parts of him, stunning by frontal attack and surprising and

confouding by flanking sweeps the mental homogeneity of the more

simply constituted souls who came in to his revival to sit under

him and flame to his flaming.

Abel Ah Yo believed in himself and his mixedness, as he believed in

the mixedness of his weird concept that God looked as much like him

as like any man, being no mere tribal god, but a world god that

must look equally like all races of all the world, even if it led

to piebaldness. And the concept worked. Chinese, Korean,

Japanese, Hawaiian, Porto Rican, Russian, English, French–members

of all races–knelt without friction, side by side, to his revision

of deity.

Himself in his tender youth an apostate to the Church of England,

Abel Ah Yo had for years suffered the lively sense of being a Judas

sinner. Essentially religious, he had foresworn the Lord. Like

Judas therefore he was. Judas was damned. Wherefore he, Abel Ah

Yo, was damned; and he did not want to be damned. So, quite after

the manner of humans, he squirmed and twisted to escape damnation.

The day came when he solved his escape. The doctrine that Judas

was damned, he concluded, was a misinterpretation of God, who,

above all things, stood for justice. Judas had been God’s servant,

specially selected to perform a particularly nasty job. Therefore

Judas, ever faithful, a betrayer only by divine command, was a

saint. Ergo, he, Abel Ah Yo, was a saint by very virtue of his

apostasy to a particular sect, and he could have access with clear

grace any time to God.

This theory became one of the major tenets of his preaching, and

was especially efficacious in cleansing the consciences of the

back-sliders from all other faiths who else, in the secrecy of

their subconscious selves, were being crushed by the weight of the

Judas sin. To Abel Ah Yo, God’s plan was as clear as if he, Abel

Ah Yo, had planned it himself. All would be saved in the end,

although some took longer than others, and would win only to

backseats. Man’s place in the ever-fluxing chaos of the world was

definite and pre-ordained–if by no other token, then by denial

that there was any ever-fluxing chaos. This was a mere bugbear of

mankind’s addled fancy; and, by stinging audacities of thought and

speech, by vivid slang that bit home by sheerest intimacy into his

listeners’ mental processes, he drove the bugbear from their

brains, showed them the loving clarity of God’s design, and,

thereby, induced in them spiritual serenity and calm.

What chance had Alice Akana, herself pure and homogeneous Hawaiian,

against his subtle, democratic-tinged, four-race-engendered, slang-

munitioned attack? He knew, by contact, almost as much as she

about the waywardness of living and sinning–having been singing

boy on the passenger-ships between Hawaii and California, and,

after that, bar boy, afloat and ashore, from the Barbary Coast to

Heinie’s Tavern. In point of fact, he had left his job of Number

One Bar Boy at the University Club to embark on his great

preachment revival.

So, when Alice Akana strayed in to scoff, she remained to pray to

Abel Ah Yo’s god, who struck her hard-headed mind as the most

sensible god of which she had ever heard. She gave money into Abel

Ah Yo’s collection plate, closed up the hula house, and dismissed

the hula dancers to more devious ways of earning a livelihood, shed

her bright colours and raiments and flower garlands, and bought a

Bible.

It was a time of religious excitement in the purlieus of Honolulu.

The thing was a democratic movement of the people toward God.

Place and caste were invited, but never came. The stupid lowly,

and the humble lowly, only, went down on its knees at the penitent

form, admitted its pathological weight and hurt of sin, eliminated

and purged all its bafflements, and walked forth again upright

under the sun, child-like and pure, upborne by Abel Ah Yo’s god’s

arm around it. In short, Abel Ah Yo’s revival was a clearing house

for sin and sickness of spirit, wherein sinners were relieved of

their burdens and made light and bright and spiritually healthy

again.

But Alice was not happy. She had not been cleared. She bought and

dispersed Bibles, contributed more money to the plate, contralto’d

gloriously in all the hymns, but would not tell her soul. In vain

Abel Ah Yo wrestled with her. She would not go down on her knees

at the penitent form and voice the things of tarnish within her–

the ill things of good friends of the old days. “You cannot serve

two masters,” Abel Ah Yo told her. “Hell is full of those who have

tried. Single of heart and pure of heart must you make your peace

with God. Not until you tell your soul to God right out in meeting

will you be ready for redemption. In the meantime you will suffer

the canker of the sin you carry about within you.”

Scientifically, though he did not know it and though he continually

jeered at science, Abel Ah Yo was right. Not could she be again as

a child and become radiantly clad in God’s grace, until she had

eliminated from her soul, by telling, all the sophistications that

had been hers, including those she shared with others. In the

Protestant way, she must bare her soul in public, as in the

Catholic way it was done in the privacy of the confessional. The

result of such baring would be unity, tranquillity, happiness,

cleansing, redemption, and immortal life.

“Choose!” Abel Ah Yo thundered. “Loyalty to God, or loyalty to

man.” And Alice could not choose. Too long had she kept her

tongue locked with the honour of man. “I will tell all my soul

about myself,” she contended. “God knows I am tired of my soul and

should like to have it clean and shining once again as when I was a

little girl at Kaneohe–“

“But all the corruption of your soul has been with other souls,”

was Abel Ah Yo’s invariable reply. “When you have a burden, lay it

down. You cannot bear a burden and be quit of it at the same time.”

“I will pray to God each day, and many times each day,” she urged.

“I will approach God with humility, with sighs and with tears. I

will contribute often to the plate, and I will buy Bibles, Bibles,

Bibles without end.”

“And God will not smile upon you,” God’s mouthpiece retorted. “And

you will remain weary and heavy-laden. For you will not have told

all your sin, and not until you have told all will you be rid of any.”

“This rebirth is difficult,” Alice sighed.

“Rebirth is even more difficult than birth.” Abel Ah Yo did

anything but comfort her. “‘Not until you become as a little child . . . ‘”

“If ever I tell my soul, it will be a big telling,” she confided.

“The bigger the reason to tell it then.”

And so the situation remained at deadlock, Abel Ah Yo demanding

absolute allegiance to God, and Alice Akana flirting on the fringes

of paradise.

“You bet it will be a big telling, if Alice ever begins,” the

beach-combing and disreputable kamaainas (old-timers) gleefully

told one another over their Palm Tree gin.

In the clubs the possibility of her telling was of more moment.

The younger generation of men announced that they had applied for

front seats at the telling, while many of the older generation of

men joked hollowly about the conversion of Alice. Further, Alice

found herself abruptly popular with friends who had forgotten her

existence for twenty years.

One afternoon, as Alice, Bible in hand, was taking the electric

street car at Hotel and Fort, Cyrus Hodge, sugar factor and

magnate, ordered his chauffeur to stop beside her. Willy nilly, in

excess of friendliness, he had her into his limousine beside him

and went three-quarters of an hour out of his way and time

personally to conduct her to her destination.

“Good for sore eyes to see you,” he burbled. “How the years fly!

You’re looking fine. The secret of youth is yours.”

Alice smiled and complimented in return in the royal Polynesian way

of friendliness.

“My, my,” Cyrus Hodge reminisced. “I was such a boy in those days!”

“SOME boy,” she laughed acquiescence.

“But knowing no more than the foolishness of a boy in those long-

ago days.”

“Remember the night your hack-driver got drunk and left you–“

“S-s-sh!” he cautioned. “That Jap driver is a high-school graduate

and knows more English than either of us. Also, I think he is a

spy for his Government. So why should we tell him anything?

Besides, I was so very young. You remember . . . “

“Your cheeks were like the peaches we used to grow before the

Mediterranean fruit fly got into them,” Alice agreed. “I don’t

think you shaved more than once a week then. You were a pretty

boy. Don’t you remember the hula we composed in your honour, the– “

“S-s-sh!” he hushed her. “All that’s buried and forgotten. May it

remain forgotten.”

And she was aware that in his eyes was no longer any of the

ingenuousness of youth she remembered. Instead, his eyes were keen

and speculative, searching into her for some assurance that she

would not resurrect his particular portion of that buried past.

“Religion is a good thing for us as we get along into middle age,”

another old friend told her. He was building a magnificent house

on Pacific Heights, but had recently married a second time, and was

even then on his way to the steamer to welcome home his two

daughters just graduated from Vassar. “We need religion in our old

age, Alice. It softens, makes us more tolerant and forgiving of

the weaknesses of others–especially the weaknesses of youth of–of

others, when they played high and low and didn’t know what they

were doing.”

He waited anxiously.

“Yes,” she said. “We are all born to sin and it is hard to grow

out of sin. But I grow, I grow.”

“Don’t forget, Alice, in those other days I always played square.

You and I never had a falling out.”

“Not even the night you gave that luau when you were twenty-one and

insisted on breaking the glassware after every toast. But of

course you paid for it.”

“Handsomely,” he asserted almost pleadingly.

“Handsomely,” she agreed. “I replaced more than double the

quantity with what you paid me, so that at the next luau I catered

one hundred and twenty plates without having to rent or borrow a

dish or glass. Lord Mainweather gave that luau–you remember him.”

“I was pig-sticking with him at Mana,” the other nodded. “We were

at a two weeks’ house-party there. But say, Alice, as you know, I

think this religion stuff is all right and better than all right.

But don’t let it carry you off your feet. And don’t get to telling

your soul on me. What would my daughters think of that broken

glassware!”

“I always did have an aloha” (warm regard) “for you, Alice,” a

member of the Senate, fat and bald-headed, assured her.

And another, a lawyer and a grandfather: “We were always friends,

Alice. And remember, any legal advice or handling of business you

may require, I’ll do for you gladly, and without fees, for the sake

of our old-time friendship.”

Came a banker to her late Christmas Eve, with formidable, legal-

looking envelopes in his hand which he presented to her.

“Quite by chance,” he explained, “when my people were looking up

land-records in Iapio Valley, I found a mortgage of two thousand on

your holdings there–that rice land leased to Ah Chin. And my mind

drifted back to the past when we were all young together, and wild-

-a bit wild, to be sure. And my heart warmed with the memory of

you, and, so, just as an aloha, here’s the whole thing cleared off

for you.”

Nor was Alice forgotten by her own people. Her house became a

Mecca for native men and women, usually performing pilgrimage

privily after darkness fell, with presents always in their hands–

squid fresh from the reef, opihis and limu, baskets of alligator

pears, roasting corn of the earliest from windward Cahu, mangoes

and star-apples, taro pink and royal of the finest selection,

sucking pigs, banana poi, breadfruit, and crabs caught the very day

from Pearl Harbour. Mary Mendana, wife of the Portuguese Consul,

remembered her with a five-dollar box of candy and a mandarin coat

that would have fetched three-quarters of a hundred dollars at a

fire sale. And Elvira Miyahara Makaena Yin Wap, the wife of Yin

Wap the wealthy Chinese importer, brought personally to Alice two

entire bolts of pina cloth from the Philippines and a dozen pairs

of silk stockings.

The time passed, and Abel Ah Yo struggled with Alice for a properly

penitent heart, and Alice struggled with herself for her soul,

while half of Honolulu wickedly or apprehensively hung on the

outcome. Carnival week was over, polo and the races had come and

gone, and the celebration of Fourth of July was ripening, ere Abel

Ah Yo beat down by brutal psychology the citadel of her reluctance.

It was then that he gave his famous exhortation which might be

summed up as Abel Ah Yo’s definition of eternity. Of course, like

Billy Sunday on certain occasions, Abel Ah Yo had cribbed the

definition. But no one in the Islands knew it, and his rating as a

revivalist uprose a hundred per cent.

So successful was his preaching that night, that he reconverted

many of his converts, who fell and moaned about the penitent form

and crowded for room amongst scores of new converts burnt by the

pentecostal fire, including half a company of negro soldiers from

the garrisoned Twenty-Fifth Infantry, a dozen troopers from the

Fourth Cavalry on its way to the Philippines, as many drunken man-

of-war’s men, divers ladies from Iwilei, and half the riff-raff of

the beach.

Abel Ah Yo, subtly sympathetic himself by virtue of his racial

admixture, knowing human nature like a book and Alice Akana even

more so, knew just what he was doing when he arose that memorable

night and exposited God, hell, and eternity in terms of Alice

Akana’s comprehension. For, quite by chance, he had discovered her

cardinal weakness. First of all, like all Polynesians, an ardent

lover of nature, he found that earthquake and volcanic eruption

were the things of which Alice lived in terror. She had been, in

the past, on the Big Island, through cataclysms that had slacken

grass houses down upon her while she slept, and she had beheld

Madame Pele (the Fire or Volcano Goddess) fling red-fluxing lava

down the long slopes of Mauna Loa, destroying fish-ponds on the

sea-brim and licking up droves of beef cattle, villages, and humans

on her fiery way.

The night before, a slight earthquake had shaken Honolulu and given

Alice Akana insomnia. And the morning papers had stated that Mauna

Kea had broken into eruption, while the lava was rising rapidly in

the great pit of Kilauea. So, at the meeting, her mind vexed

between the terrors of this world and the delights of the eternal

world to come, Alice sat down in a front seat in a very definite

state of the “jumps.”

And Abel Ah Yo arose and put his finger on the sorest part of her

soul. Sketching the nature of God in the stereotyped way, but

making the stereotyped alive again with his gift of tongues in

Pidgin-English and Pidgin-Hawaiian, Abel Ah Yo described the day

when the Lord, even His infinite patience at an end, would tell

Peter to close his day book and ledgers, command Gabriel to summon

all souls to Judgment, and cry out with a voice of thunder: “Welakahao!”

This anthromorphic deity of Abel Ah Yo thundering the modern

Hawaiian-English slang of welakahao at the end of the world, is a

fair sample of the revivalist’s speech-tools of discourse.

Welakahao means literally “hot iron.” It was coined in the

Honolulu Iron-works by the hundreds of Hawaiian men there employed,

who meant by it “to hustle,” “to get a move on,” the iron being hot

meaning that the time had come to strike.

“And the Lord cried ‘Welakahao,’ and the Day of Judgment began and

was over wiki-wiki” (quickly) “just like that; for Peter was a

better bookkeeper than any on the Waterhouse Trust Company Limited,

and, further, Peter’s books were true.”

Swiftly Abel Ah Yo divided the sheep from the goats, and hastened

the latter down into hell.

“And now,” he demanded, perforce his language on these pages being

properly Englished, “what is hell like? Oh, my friends, let me

describe to you, in a little way, what I have beheld with my own

eves on earth of the possibilities of hell. I was a young man, a

boy, and I was at Hilo. Morning began with earthquakes.

Throughout the day the mighty land continued to shake and tremble,

till strong men became seasick, and women clung to trees to escape

falling, and cattle were thrown down off their feet. I beheld

myself a young calf so thrown. A night of terror indescribable

followed. The land was in motion like a canoe in a Kona gale.

There was an infant crushed to death by its fond mother stepping

upon it whilst fleeing her falling house.

“The heavens were on fire above us. We read our Bibles by the

light of the heavens, and the print was fine, even for young eyes.

Those missionary Bibles were always too small of print. Forty

miles away from us, the heart of hell burst from the lofty

mountains and gushed red-blood of fire-melted rock toward the sea.

With the heavens in vast conflagration and the earth hulaing

beneath our feet, was a scene too awful and too majestic to be

enjoyed. We could think only of the thin bubble-skin of earth

between us and the everlasting lake of fire and brimstone, and of

God to whom we prayed to save us. There were earnest and devout

souls who there and then promised their pastors to give not their

shaved tithes, but five-tenths of their all to the church, if only

the Lord would let them live to contribute.

“Oh, my friends, God saved us. But first he showed us a foretaste

of that hell that will yawn for us on the last day, when he cries

‘Welakahao!’ in a voice of thunder. When the iron is hot! Think

of it! When the iron is hot for sinners!

“By the third day, things being much quieter, my friend the

preacher and I, being calm in the hand of God, journeyed up Mauna

Loa and gazed into the awful pit of Kilauea. We gazed down into

the fathomless abyss to the lake of fire far below, roaring and

dashing its fiery spray into billows and fountaining hundreds of

feet into the air like Fourth of July fireworks you have all seen,

and all the while we were suffocating and made dizzy by the immense

volumes of smoke and brimstone ascending.

“And I say unto you, no pious person could gaze down upon that

scene without recognizing fully the Bible picture of the Pit of

Hell. Believe me, the writers of the New Testament had nothing on

us. As for me, my eyes were fixed upon the exhibition before me,

and I stood mute and trembling under a sense never before so fully

realized of the power, the majesty, and terror of Almighty God–the

resources of His wrath, and the untold horrors of the finally

impenitent who do not tell their souls and make their peace with

the Creator.

“But oh, my friends, think you our guides, our native attendants,

deep-sunk in heathenism, were affected by such a scene? No. The

devil’s hand was upon them. Utterly regardless and unimpressed,

they were only careful about their supper, chatted about their raw

fish, and stretched themselves upon their mats to sleep. Children

of the devil they were, insensible to the beauties, the

sublimities, and the awful terror of God’s works. But you are not

heathen I now address. What is a heathen? He is one who betrays a

stupid insensibility to every elevated idea and to every elevated

emotion. If you wish to awaken his attention, do not bid him to

look down into the Pit of Hell. But present him with a calabash of

poi, a raw fish, or invite him to some low, grovelling, and

sensuous sport. Oh, my friends, how lost are they to all that

elevates the immortal soul! But the preacher and I, sad and sick

at heart for them, gazed down into hell. Oh, my friends, it WAS

hell, the hell of the Scriptures, the hell of eternal torment for

the undeserving . . . “

Alice Akana was in an ecstasy or hysteria of terror. She was

mumbling incoherently: “O Lord, I will give nine-tenths of my all.

I will give all. I will give even the two bolts of pina cloth, the

mandarin coat, and the entire dozen silk stockings . . . “

By the time she could lend ear again, Abel Ah Yo was launching out

on his famous definition of eternity.

“Eternity is a long time, my friends. God lives, and, therefore,

God lives inside eternity. And God is very old. The fires of hell

are as old and as everlasting as God. How else could there be

everlasting torment for those sinners cast down by God into the Pit

on the Last Day to burn for ever and for ever through all eternity?

Oh, my friends, your minds are small–too small to grasp eternity.

Yet is it given to me, by God’s grace, to convey to you an

understanding of a tiny bit of eternity.

“The grains of sand on the beach of Waikiki are as many as the

stars, and more. No man may count them. Did he have a million

lives in which to count them, he would have to ask for more time.

Now let us consider a little, dinky, old minah bird with one broken

wing that cannot fly. At Waikiki the minah bird that cannot fly

takes one grain of sand in its beak and hops, hops, all day lone

and for many days, all the day to Pearl Harbour and drops that one

grain of sand into the harbour. Then it hops, hops, all day and

for many days, all the way back to Waikiki for another grain of

sand. And again it hops, hops all the way back to Pearl Harbour.

And it continues to do this through the years and centuries, and

the thousands and thousands of centuries, until, at last, there

remains not one grain of sand at Waikiki and Pearl Harbour is

filled up with land and growing coconuts and pine-apples. And

then, oh my friends, even then, IT WOULD NOT YET BE SUNRISE IN

HELL!

Here, at the smashing impact of so abrupt a climax, unable to

withstand the sheer simplicity and objectivity of such artful

measurement of a trifle of eternity, Alice Akana’s mind broke down

and blew up. She uprose, reeled blindly, and stumbled to her knees

at the penitent form. Abel Ah Yo had not finished his preaching,

but it was his gift to know crowd psychology, and to feel the heat

of the pentecostal conflagration that scorched his audience. He

called for a rousing revival hymn from his singers, and stepped

down to wade among the hallelujah-shouting negro soldiers to Alice

Akana. And, ere the excitement began to ebb, nine-tenths of his

congregation and all his converts were down on knees and praying

and shouting aloud an immensity of contriteness and sin.

Word came, via telephone, almost simultaneously to the Pacific and

University Clubs, that at last Alice was telling her soul in

meeting; and, by private machine and taxi-cab, for the first time

Abel Ah Yo’s revival was invaded by those of caste and place. The

first comers beheld the curious sight of Hawaiian, Chinese, and all

variegated racial mixtures of the smelting-pot of Hawaii, men and

women, fading out and slinking away through the exits of Abel Ah

Yo’s tabernacle. But those who were sneaking out were mostly men,

while those who remained were avid-faced as they hung on Alice’s

utterance.

Never was a more fearful and damning community narrative enunciated

in the entire Pacific, north and south, than that enunciated by

Alice Akana; the penitent Phryne of Honolulu.

“Huh!” the first comers heard her saying, having already disposed

of most of the venial sins of the lesser ones of her memory. “You

think this man, Stephen Makekau, is the son of Moses Makekau and

Minnie Ah Ling, and has a legal right to the two hundred and eight

dollars he draws down each month from Parke Richards Limited, for

the lease of the fish-pond to Bill Kong at Amana. Not so. Stephen

Makekau is not the son of Moses. He is the son of Aaron Kama and

Tillie Naone. He was given as a present, as a feeding child, to

Moses and Minnie, by Aaron and Tillie. I know. Moses and Minnie

and Aaron and Tillie are dead. Yet I know and can prove it. Old

Mrs. Poepoe is still alive. I was present when Stephen was born,

and in the night-time, when he was two months old, I myself carried

him as a present to Moses and Minnie, and old Mrs. Poepoe carried

the lantern. This secret has been one of my sins. It has kept me

from God. Now I am free of it. Young Archie Makekau, who collects

bills for the Gas Company and plays baseball in the afternoons, and

drinks too much gin, should get that two hundred and eight dollars

the first of each month from Parke Richards Limited. He will blow

it in on gin and a Ford automobile. Stephen is a good man. Archie

is no good. Also he is a liar, and he has served two sentences on

the reef, and was in reform school before that. Yet God demands

the truth, and Archie will get the money and make a bad use of it.”

And in such fashion Alice rambled on through the experiences of her

long and full-packed life. And women forgot they were in the

tabernacle, and men too, and faces darkened with passion as they

learned for the first time the long-buried secrets of their other halves.

“The lawyers’ offices will be crowded to-morrow morning,”

MacIlwaine, chief of detectives, paused long enough from storing

away useful information to lean and mutter in Colonel Stilton’s ear.

Colonel Stilton grinned affirmation, although the chief of

detectives could not fail to note the ghastliness of the grin.

“There is a banker in Honolulu. You all know his name. He is ‘way

up, swell society because of his wife. He owns much stock in

General Plantations and Inter-Island.”

MacIlwaine recognized the growing portrait and forbore to chuckle.

“His name is Colonel Stilton. Last Christmas Eve he came to my

house with big aloha” (love) “and gave me mortgages on my land in

Iapio Valley, all cancelled, for two thousand dollars’ worth. Now

why did he have such big cash aloha for me? I will tell you . . .”

And tell she did, throwing the searchlight on ancient business

transactions and political deals which from their inception had

lurked in the dark.

“This,” Alice concluded the episode, “has long been a sin upon my

conscience, and kept my heart from God.

“And Harold Miles was that time President of the Senate, and next

week he bought three town lots at Pearl Harbour, and painted his

Honolulu house, and paid up his back dues in his clubs. Also the

Ramsay home at Honokiki was left by will to the people if the

Government would keep it up. But if the Government, after two

years, did not begin to keep it up, then would it go to the Ramsay

heirs, whom old Ramsay hated like poison. Well, it went to the

heirs all right. Their lawyer was Charley Middleton, and he had me

help fix it with the Government men. And their names were . . . “

Six names, from both branches of the Legislature, Alice recited,

and added: “Maybe they all painted their houses after that. For

the first time have I spoken. My heart is much lighter and softer.

It has been coated with an armour of house-paint against the Lord.

And there is Harry Werther. He was in the Senate that time.

Everybody said bad things about him, and he was never re-elected.

Yet his house was not painted. He was honest. To this day his

house is not painted, as everybody knows.

“There is Jim Lokendamper. He has a bad heart. I heard him, only

last week, right here before you all, tell his soul. He did not

tell all his soul, and he lied to God. I am not lying to God. It

is a big telling, but I am telling everything. Now Azalea Akau,

sitting right over there, is his wife. But Lizzie Lokendamper is

his married wife. A long time ago he had the great aloha for

Azalea. You think her uncle, who went to California and died, left

her by will that two thousand five hundred dollars she got. Her

uncle did not. I know. Her uncle cried broke in California, and

Jim Lokendamper sent eighty dollars to California to bury him. Jim

Lokendamper had a piece of land in Kohala he got from his mother’s

aunt. Lizzie, his married wife, did not know this. So he sold it

to the Kohala Ditch Company and wave the twenty-five hundred to

Azalea Akau–“

Here, Lizzie, the married wife, upstood like a fury long-thwarted,

and, in lieu of her husband, already fled, flung herself tooth and

nail on Azalea.

“Wait, Lizzie Lokendamper!” Alice cried out. “I have much weight

of you on my heart and some house-paint too . . . “

And when she had finished her disclosure of how Lizzie had painted

her house, Azalea was up and raging.

“Wait, Azalea Akau. I shall now lighten my heart about you. And

it is not house-paint. Jim always paid that. It is your new bath-

tub and modern plumbing that is heavy on me . . . “

Worse, much worse, about many and sundry, did Alice Akana have to

say, cutting high in business, financial, and social life, as well

as low. None was too high nor too low to escape; and not until two

in the morning, before an entranced audience that packed the

tabernacle to the doors, did she complete her recital of the

personal and detailed iniquities she knew of the community in which

she had lived intimately all her days. Just as she was finishing,

she remembered more.

“Huh!” she sniffed. “I gave last week one lot worth eight hundred

dollars cash market price to Abel Ah Yo to pay running expenses and

add up in Peter’s books in heaven. Where did I get that lot? You

all think Mr. Fleming Jason is a good man. He is more crooked than

the entrance was to Pearl Lochs before the United States Government

straightened the channel. He has liver disease now; but his

sickness is a judgment of God, and he will die crooked. Mr.

Fleming Jason gave me that lot twenty-two years ago, when its cash

market price was thirty-five dollars. Because his aloha for me was

big? No. He never had aloha inside of him except for dollars.

“You listen. Mr. Fleming Jason put a great sin upon me. When

Frank Lomiloli was at my house, full of gin, for which gin Mr.

Fleming Jason paid me in advance five times over, I got Frank

Lomiloli to sign his name to the sale paper of his town land for

one hundred dollars. It was worth six hundred then. It is worth

twenty thousand now. Maybe you want to know where that town land

is. I will tell you and remove it off my heart. It is on King

Street, where is now the Come Again Saloon, the Japanese Taxicab

Company garage, the Smith & Wilson plumbing shop, and the Ambrosia

lee Cream Parlours, with the two more stories big Addison Lodging

House overhead. And it is all wood, and always has been well

painted. Yesterday they started painting it attain. But that

paint will not stand between me and God. There are no more paint

pots between me and my path to heaven.”

The morning and evening papers of the day following held an unholy

hush on the greatest news story of years; but Honolulu was half a-

giggle and half aghast at the whispered reports, not always basely

exaggerated, that circulated wherever two Honoluluans chanced to meet.

“Our mistake,” said Colonel Chilton, at the club, “was that we did

not, at the very first, appoint a committee of safety to keep track

of Alice’s soul.”

Bob Cristy, one of the younger islanders, burst into laughter, so

pointed and so loud that the meaning of it was demanded.

“Oh, nothing much,” was his reply. “But I heard, on my way here,

that old John Ward had just been run in for drunken and disorderly

conduct and for resisting an officer. Now Abel Ah Yo fine-

toothcombs the police court. He loves nothing better than soul-

snatching a chronic drunkard.”

Colonel Chilton looked at Lask Finneston, and both looked at Gary

Wilkinson. He returned to them a similar look.

“The old beachcomber!” Lask Finneston cried. “The drunken old

reprobate! I’d forgotten he was alive. Wonderful constitution.

Never drew a sober breath except when he was shipwrecked, and, when

I remember him, into every deviltry afloat. He must be going on eighty.”

“He isn’t far away from it,” Bob Cristy nodded. “Still beach-

combs, drinks when he gets the price, and keeps all his senses,

though he’s not spry and has to use glasses when he reads. And his

memory is perfect. Now if Abel Ah Yo catches him . . . “

Gary Wilkinson cleared his throat preliminary to speech.

“Now there’s a grand old man,” he said. “A left-over from a

forgotten age. Few of his type remain. A pioneer. A true

kamaaina” (old-timer). “Helpless and in the hands of the police in

his old age! We should do something for him in recognition of his

yeoman work in Hawaii. His old home, I happen to know, is Sag

Harbour. He hasn’t seen it for over half a century. Now why

shouldn’t he be surprised to-morrow morning by having his fine

paid, and by being presented with return tickets to Sag Harbour,

and, say, expenses for a year’s trip? I move a committee. I

appoint Colonel Chilton, Lask Finneston, and . . . and myself. As

for chairman, who more appropriate than Lask Finneston, who knew

the old gentleman so well in the early days? Since there is no

objection, I hereby appoint Lask Finneston chairman of the

committee for the purpose of raising and donating money to pay the

police-court fine and the expenses of a year’s travel for that

noble pioneer, John Ward, in recognition of a lifetime of devotion

of energy to the upbuilding of Hawaii.”

There was no dissent.

“The committee will now go into secret session,” said Lask

Finneston, arising and indicating the way to the library.

GLEN ELLEN, CALIFORNIA,

August 30, 1916.

From Jack London: ON THE MAKALOA MAT/ISLAND TALES

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Archive K-L, London, Jack

James Joyce

(1882-1941)

A Painful Case

Mr. James Duffy lived in Chapelizod because he wished to live as far as possible from the city of which he was a citizen and because he found all the other suburbs of Dublin mean, modern and pretentious. He lived in an old sombre house and from his windows he could look into the disused distillery or upwards along the shallow river on which Dublin is built. The lofty walls of his uncarpeted room were free from pictures. He had himself bought every article of furniture in the room: a black iron bedstead, an iron washstand, four cane chairs, a clothes-rack, a coal-scuttle, a fender and irons and a square table on which lay a double desk. A bookcase had been made in an alcove by means of shelves of white wood. The bed was clothed with white bedclothes and a black and scarlet rug covered the foot. A little hand-mirror hung above the washstand and during the day a white-shaded lamp stood as the sole ornament of the mantelpiece. The books on the white wooden shelves were arranged from below upwards according to bulk. A complete Wordsworth stood at one end of the lowest shelf and a copy of the Maynooth Catechism, sewn into the cloth cover of a notebook, stood at one end of the top shelf. Writing materials were always on the desk. In the desk lay a manuscript translation of Hauptmann’s Michael Kramer, the stage directions of which were written in purple ink, and a little sheaf of papers held together by a brass pin. In these sheets a sentence was inscribed from time to time and, in an ironical moment, the headline of an advertisement for Bile Beans had been pasted on to the first sheet. On lifting the lid of the desk a faint fragrance escaped, the fragrance of new cedarwood pencils or of a bottle of gum or of an overripe apple which might have been left there and forgotten.

Mr. Duffy abhorred anything which betokened physical or mental disorder. A medival doctor would have called him saturnine. His face, which carried the entire tale of his years, was of the brown tint of Dublin streets. On his long and rather large head grew dry black hair and a tawny moustache did not quite cover an unamiable mouth. His cheekbones also gave his face a harsh character; but there was no harshness in the eyes which, looking at the world from under their tawny eyebrows, gave the impression of a man ever alert to greet a redeeming instinct in others but often disappointed. He lived at a little distance from his body, regarding his own acts with doubtful side-glasses. He had an odd autobiographical habit which led him to compose in his mind from time to time a short sentence about himself containing a subject in the third person and a predicate in the past tense. He never gave alms to beggars and walked firmly, carrying a stout hazel.

He had been for many years cashier of a private bank in Baggot Street. Every morning he came in from Chapelizod by tram. At midday he went to Dan Burke’s and took his lunch, a bottle of lager beer and a small trayful of arrowroot biscuits. At four o’clock he was set free. He dined in an eating-house in George’s Street where he felt himself safe from the society of Dublin’s gilded youth and where there was a certain plain honesty in the bill of fare. His evenings were spent either before his landlady’s piano or roaming about the outskirts of the city. His liking for Mozart’s music brought him sometimes to an opera or a concert: these were the only dissipations of his life.

He had neither companions nor friends, church nor creed. He lived his spiritual life without any communion with others, visiting his relatives at Christmas and escorting them to the cemetery when they died. He performed these two social duties for old dignity’s sake but conceded nothing further to the conventions which regulate the civic life. He allowed himself to think that in certain circumstances he would rob his hank but, as these circumstances never arose, his life rolled out evenly, an adventureless tale.

One evening he found himself sitting beside two ladies in the Rotunda. The house, thinly peopled and silent, gave distressing prophecy of failure. The lady who sat next him looked round at the deserted house once or twice and then said:

“What a pity there is such a poor house tonight! It’s so hard on people to have to sing to empty benches.”

He took the remark as an invitation to talk. He was surprised that she seemed so little awkward. While they talked he tried to fix her permanently in his memory. When he learned that the young girl beside her was her daughter he judged her to be a year or so younger than himself. Her face, which must have been handsome, had remained intelligent. It was an oval face with strongly marked features. The eyes were very dark blue and steady. Their gaze began with a defiant note but was confused by what seemed a deliberate swoon of the pupil into the iris, revealing for an instant a temperament of great sensibility. The pupil reasserted itself quickly, this half-disclosed nature fell again under the reign of prudence, and her astrakhan jacket, moulding a bosom of a certain fullness, struck the note of defiance more definitely.

He met her again a few weeks afterwards at a concert in Earlsfort Terrace and seized the moments when her daughter’s attention was diverted to become intimate. She alluded once or twice to her husband but her tone was not such as to make the allusion a warning. Her name was Mrs. Sinico. Her husband’s great-great-grandfather had come from Leghorn. Her husband was captain of a mercantile boat plying between Dublin and Holland; and they had one child.

Meeting her a third time by accident he found courage to make an appointment. She came. This was the first of many meetings; they met always in the evening and chose the most quiet quarters for their walks together. Mr. Duffy, however, had a distaste for underhand ways and, finding that they were compelled to meet stealthily, he forced her to ask him to her house. Captain Sinico encouraged his visits, thinking that his daughter’s hand was in question. He had dismissed his wife so sincerely from his gallery of pleasures that he did not suspect that anyone else would take an interest in her. As the husband was often away and the daughter out giving music lessons Mr. Duffy had many opportunities of enjoying the lady’s society. Neither he nor she had had any such adventure before and neither was conscious of any incongruity. Little by little he entangled his thoughts with hers. He lent her books, provided her with ideas, shared his intellectual life with her. She listened to all.

Sometimes in return for his theories she gave out some fact of her own life. With almost maternal solicitude she urged him to let his nature open to the full: she became his confessor. He told her that for some time he had assisted at the meetings of an Irish Socialist Party where he had felt himself a unique figure amidst a score of sober workmen in a garret lit by an inefficient oil-lamp. When the party had divided into three sections, each under its own leader and in its own garret, he had discontinued his attendances. The workmen’s discussions, he said, were too timorous; the interest they took in the question of wages was inordinate. He felt that they were hard-featured realists and that they resented an exactitude which was the produce of a leisure not within their reach. No social revolution, he told her, would be likely to strike Dublin for some centuries.

She asked him why did he not write out his thoughts. For what, he asked her, with careful scorn. To compete with phrasemongers, incapable of thinking consecutively for sixty seconds? To submit himself to the criticisms of an obtuse middle class which entrusted its morality to policemen and its fine arts to impresarios?

He went often to her little cottage outside Dublin; often they spent their evenings alone. Little by little, as their thoughts entangled, they spoke of subjects less remote. Her companionship was like a warm soil about an exotic. Many times she allowed the dark to fall upon them, refraining from lighting the lamp. The dark discreet room, their isolation, the music that still vibrated in their ears united them. This union exalted him, wore away the rough edges of his character, emotionalised his mental life. Sometimes he caught himself listening to the sound of his own voice. He thought that in her eyes he would ascend to an angelical stature; and, as he attached the fervent nature of his companion more and more closely to him, he heard the strange impersonal voice which he recognised as his own, insisting on the soul’s incurable loneliness. We cannot give ourselves, it said: we are our own. The end of these discourses was that one night during which she had shown every sign of unusual excitement, Mrs. Sinico caught up his hand passionately and pressed it to her cheek.

Mr. Duffy was very much surprised. Her interpretation of his words disillusioned him. He did not visit her for a week, then he wrote to her asking her to meet him. As he did not wish their last interview to be troubled by the influence of their ruined confessional they meet in a little cakeshop near the Parkgate. It was cold autumn weather but in spite of the cold they wandered up and down the roads of the Park for nearly three hours. They agreed to break off their intercourse: every bond, he said, is a bond to sorrow. When they came out of the Park they walked in silence towards the tram; but here she began to tremble so violently that, fearing another collapse on her part, he bade her good-bye quickly and left her. A few days later he received a parcel containing his books and music.

Four years passed. Mr. Duffy returned to his even way of life. His room still bore witness of the orderliness of his mind. Some new pieces of music encumbered the music-stand in the lower room and on his shelves stood two volumes by Nietzsche: Thus Spake Zarathustra and The Gay Science. He wrote seldom in the sheaf of papers which lay in his desk. One of his sentences, written two months after his last interview with Mrs. Sinico, read: Love between man and man is impossible because there must not be sexual intercourse and friendship between man and woman is impossible because there must be sexual intercourse. He kept away from concerts lest he should meet her. His father died; the junior partner of the bank retired. And still every morning he went into the city by tram and every evening walked home from the city after having dined moderately in George’s Street and read the evening paper for dessert.

One evening as he was about to put a morsel of corned beef and cabbage into his mouth his hand stopped. His eyes fixed themselves on a paragraph in the evening paper which he had propped against the water-carafe. He replaced the morsel of food on his plate and read the paragraph attentively. Then he drank a glass of water, pushed his plate to one side, doubled the paper down before him between his elbows and read the paragraph over and over again. The cabbage began to deposit a cold white grease on his plate. The girl came over to him to ask was his dinner not properly cooked. He said it was very good and ate a few mouthfuls of it with difficulty. Then he paid his bill and went out.

He walked along quickly through the November twilight, his stout hazel stick striking the ground regularly, the fringe of the buff Mail peeping out of a side-pocket of his tight reefer overcoat. On the lonely road which leads from the Parkgate to Chapelizod he slackened his pace. His stick struck the ground less emphatically and his breath, issuing irregularly, almost with a sighing sound, condensed in the wintry air. When he reached his house he went up at once to his bedroom and, taking the paper from his pocket, read the paragraph again by the failing light of the window. He read it not aloud, but moving his lips as a priest does when he reads the prayers Secreto. This was the paragraph:

DEATH OF A LADY AT SYDNEY PARADE

A PAINFUL CASE

Today at the City of Dublin Hospital the Deputy Coroner (in the absence of Mr. Leverett) held an inquest on the body of Mrs. Emily Sinico, aged forty-three years, who was killed at Sydney Parade Station yesterday evening. The evidence showed that the deceased lady, while attempting to cross the line, was knocked down by the engine of the ten o’clock slow train from Kingstown, thereby sustaining injuries of the head and right side which led to her death.

James Lennon, driver of the engine, stated that he had been in the employment of the railway company for fifteen years. On hearing the guard’s whistle he set the train in motion and a second or two afterwards brought it to rest in response to loud cries. The train was going slowly.

P. Dunne, railway porter, stated that as the train was about to start he observed a woman attempting to cross the lines. He ran towards her and shouted, but, before he could reach her, she was caught by the buffer of the engine and fell to the ground.

A juror. “You saw the lady fall?”

Witness. “Yes.”

Police Sergeant Croly deposed that when he arrived he found the deceased lying on the platform apparently dead. He had the body taken to the waiting-room pending the arrival of the ambulance.

Constable 57 corroborated.

Dr. Halpin, assistant house surgeon of the City of Dublin Hospital, stated that the deceased had two lower ribs fractured and had sustained severe contusions of the right shoulder. The right side of the head had been injured in the fall. The injuries were not sufficient to have caused death in a normal person. Death, in his opinion, had been probably due to shock and sudden failure of the heart’s action.

Mr. H. B. Patterson Finlay, on behalf of the railway company, expressed his deep regret at the accident. The company had always taken every precaution to prevent people crossing the lines except by the bridges, both by placing notices in every station and by the use of patent spring gates at level crossings. The deceased had been in the habit of crossing the lines late at night from platform to platform and, in view of certain other circumstances of the case, he did not think the railway officials were to blame.

Captain Sinico, of Leoville, Sydney Parade, husband of the deceased, also gave evidence. He stated that the deceased was his wife. He was not in Dublin at the time of the accident as he had arrived only that morning from Rotterdam. They had been married for twenty-two years and had lived happily until about two years ago when his wife began to be rather intemperate in her habits.

Miss Mary Sinico said that of late her mother had been in the habit of going out at night to buy spirits. She, witness, had often tried to reason with her mother and had induced her to join a League. She was not at home until an hour after the accident. The jury returned a verdict in accordance with the medical evidence and exonerated Lennon from all blame.

The Deputy Coroner said it was a most painful case, and expressed great sympathy with Captain Sinico and his daughter. He urged on the railway company to take strong measures to prevent the possibility of similar accidents in the future. No blame attached to anyone.

Mr. Duffy raised his eyes from the paper and gazed out of his window on the cheerless evening landscape. The river lay quiet beside the empty distillery and from time to time a light appeared in some house on the Lucan road. What an end! The whole narrative of her death revolted him and it revolted him to think that he had ever spoken to her of what he held sacred. The threadbare phrases, the inane expressions of sympathy, the cautious words of a reporter won over to conceal the details of a commonplace vulgar death attacked his stomach. Not merely had she degraded herself; she had degraded him. He saw the squalid tract of her vice, miserable and malodorous. His soul’s companion! He thought of the hobbling wretches whom he had seen carrying cans and bottles to be filled by the barman. Just God, what an end! Evidently she had been unfit to live, without any strength of purpose, an easy prey to habits, one of the wrecks on which civilisation has been reared. But that she could have sunk so low! Was it possible he had deceived himself so utterly about her? He remembered her outburst of that night and interpreted it in a harsher sense than he had ever done. He had no difficulty now in approving of the course he had taken.

As the light failed and his memory began to wander he thought her hand touched his. The shock which had first attacked his stomach was now attacking his nerves. He put on his overcoat and hat quickly and went out. The cold air met him on the threshold; it crept into the sleeves of his coat. When he came to the public-house at Chapelizod Bridge he went in and ordered a hot punch.

The proprietor served him obsequiously but did not venture to talk. There were five or six workingmen in the shop discussing the value of a gentleman’s estate in County Kildare They drank at intervals from their huge pint tumblers and smoked, spitting often on the floor and sometimes dragging the sawdust over their spits with their heavy boots. Mr. Duffy sat on his stool and gazed at them, without seeing or hearing them. After a while they went out and he called for another punch. He sat a long time over it. The shop was very quiet. The proprietor sprawled on the counter reading the Herald and yawning. Now and again a tram was heard swishing along the lonely road outside.

As he sat there, living over his life with her and evoking alternately the two images in which he now conceived her, he realised that she was dead, that she had ceased to exist, that she had become a memory. He began to feel ill at ease. He asked himself what else could he have done. He could not have carried on a comedy of deception with her; he could not have lived with her openly. He had done what seemed to him best. How was he to blame? Now that she was gone he understood how lonely her life must have been, sitting night after night alone in that room. His life would be lonely too until he, too, died, ceased to exist, became a memory, if anyone remembered him.

It was after nine o’clock when he left the shop. The night was cold and gloomy. He entered the Park by the first gate and walked along under the gaunt trees. He walked through the bleak alleys where they had walked four years before. She seemed to be near him in the darkness. At moments he seemed to feel her voice touch his ear, her hand touch his. He stood still to listen. Why had he withheld life from her? Why had he sentenced her to death? He felt his moral nature falling to pieces.

When he gained the crest of the Magazine Hill he halted and looked along the river towards Dublin, the lights of which burned redly and hospitably in the cold night. He looked down the slope and, at the base, in the shadow of the wall of the Park, he saw some human figures lying. Those venal and furtive loves filled him with despair. He gnawed the rectitude of his life; he felt that he had been outcast from life’s feast. One human being had seemed to love him and he had denied her life and happiness: he had sentenced her to ignominy, a death of shame. He knew that the prostrate creatures down by the wall were watching him and wished him gone. No one wanted him; he was outcast from life’s feast. He turned his eyes to the grey gleaming river, winding along towards Dublin. Beyond the river he saw a goods train winding out of Kingsbridge Station, like a worm with a fiery head winding through the darkness, obstinately and laboriously. It passed slowly out of sight; but still he heard in his ears the laborious drone of the engine reiterating the syllables of her name.

He turned back the way he had come, the rhythm of the engine pounding in his ears. He began to doubt the reality of what memory told him. He halted under a tree and allowed the rhythm to die away. He could not feel her near him in the darkness nor her voice touch his ear. He waited for some minutes listening. He could hear nothing: the night was perfectly silent. He listened again: perfectly silent. He felt that he was alone.

James Joyce: A Painful Case

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive I-J, Joyce, James, Joyce, James

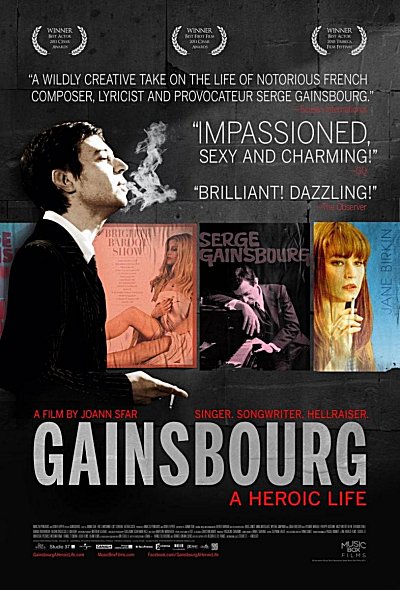

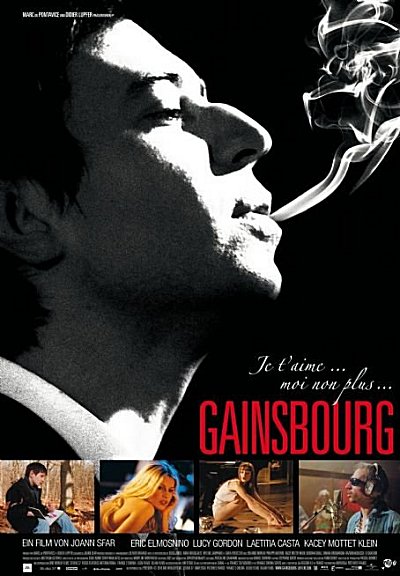

Serge Gainsbourg, vie héroïque

film met Lucy Gordon

CANVAS TV BE

vrijdag 15 februari 2013 – 22.10

Film, Frankrijk – 2010

Duur: 130 min

Door haar Joods-Russische afkomst heeft de familie van de jonge Lucien Ginsburg het niet gemakkelijk in het bezette Parijs tijdens de oorlogsjaren. Later gaat Lucien aan de kunstschool studeren. Hij komt aan de kost met optredens in bars en cabarets. In de jaren 60 breekt hij door als Serge Gainsbourg, de ster van het cabaret de Swinging Sixties. Hij verlegt de grenzen van het chanson en maakt naam met zijn onconventionele muziek en zijn rebelse gedrag. Hij is bevriend met onder meer Brigitte Bardot en Juliette Gréco. Gainsbourg wordt een icoon van de Franse cultuur, maar maakt ook ophef met zijn turbulente liefdesleven met Jane Birkin en vele anderen

Regisseur Joann SFAR

Acteurs

Eric ELMOSNINO / Serge Gainsbourg

Lucy GORDON / Jane Birkin

Laetitia CASTA / Brigitte Bardot

Anna MOUGLALIS / Juliette Gréco

Sara FORESTIER / France Gall

Kacey MOTTET KLEIN / Lucien Ginsburg

Lucy Gordon

(May 22, 1980 – May 20, 2009)

Lucy Gordon was a British actress and model, born in Oxford, England. She committed suicide on 20 May 2009, in her apartment in Paris, France, two days before her 29th birthday.

Filmography

2001: Perfume (Lucy Gordon as Sarah)

2001: Serendipity (Lucy Gordon as Caroline Mitchell)

2002: The Four Feathers by Shekhar Kapur (Lucy Gordon as Isabelle)

2005: The Russian Dolls by Cédric Klapisch (Lucy Gordon as Celia Shelburn)

2007: Serial de Kevin Arbouet et Larry Strong (Lucy Gordon as Sadie Grady)

2007: Spider-Man 3 by Sam Raimi (Lucy Gordon as Jennifer Dugan)

2008: Frost by Steve Clark (Lucy Gordon as Kate Hardwick)

2009: Brief Interviews with Hideous Men by John Krasinski (Lucy Gordon as Hitchhiker)

2009: Cinéman (Lucy gordon as Fernandel’s friend)

2010: Serge Gainsbourg, vie héroïque (Lucy Gordon as Jane Birkin)

To be published soon Collected Stories by Jef van Kempen:

(with Angel of Paris. Life and death of Lucy Gordon)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: AUDIO, CINEMA, RADIO & TV, Jef van Kempen, Kempen, Jef van, Lucy Gordon

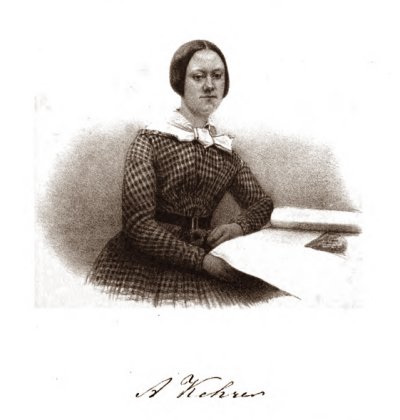

Albertine Kehrer

(1826-1852)

Wat niet is uit te staan

Wat niet is uit te staan

De geur van ingemaakte kropsla

Rijmend proza; slappe thee;

Vorken met een haringsmaakje

Op een uitgezocht diner;

Een bon mot, dat, niet begrepen,

Uitleg of herhaling eist;

Van uw goed te zijn verstoken,

Als gij voor genoegen reist;

In de kerk, in januari,

Bij abuis uw stoof niet warm;

Als gij worsten denkt te stoppen,

Heel veel gaten in de darm

(…)

En – een hand, die niet gedrukt wordt,

Zoo trouwhartig als gij ‘t doet;

(…)

Door de Torenstraat te moeten

Met een parapluie als ‘t stormt;

(…)

Complimenten aan te horen,

Niet verdiend en niet gemeend;

En – een vingerhoed met gaatjes

Dien gij van een kennis leent;

‘t Carillon des maandagsochtends,

Vrijdagmorgens bovendien,

Ingesteld in oude dagen,

Tot vermaak van ‘k weet niet wien;

Naaiwerk, thuis gestuurd, doortrokken

Met een geur van zoutevis

Was opdoen met winterhanden

Als het goed bevroren is;

Rolpens in ‘t begin van juli

Onuitsprekelijk zout en hard:

Iemand met een neusverkoudheid

Naast u zittend op ‘t concert

Zonneschijn en zomerwarmte

Als gij op een stoomboot wacht;

En in ‘t eind de lof der zotten

Openlijk u toegebracht!

Albertine Kehrer poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Albertine Kehrer, Archive K-L, Kehrer, Albertine

Gottfried Keller

(1819–1890)

Modernster Faust

Ich bin ein ganzer Held! Den Mantel umgeschlagen

– Romantisch schwarzer Samt erglänzt an Kleid und Kragen –

Stürm ich dahin in eitlem Wahn!

Ob Samt? ob nur Kattun? es war ein langes Zanken

Mit meinem Mütterlein; doch fest und ohne Wanken

Erstritt ich Samt, und niemand sieht mir’s an.

Leichtsinnig, hohen Muts mach ich die Morgenrunde;

Die Wintersonne scheint, Cigarro brennt im Munde,

Den ich dem Kaufmann schuldig bin;

Die Wintersonne scheint, kalt ist ihr Silberflimmer,

Und kalt ist mir das Herz, kalt meiner Augen Schimmer

Und trüb, befangen immerhin.

Da treff ich einen Freund auf meiner irren Bahn,

Wir halten mit Geklatsch ein halbes Stündchen an;

Wie wenn zwei alte Hexen schelten,

So bricht von Bosheit nun und Neid ein ganzer Chor

Von Zoten, schlechtem Witz und Haß aus uns hervor,

Daß mir verschämt die eignen Ohren gellten.

Da kommt ein Handwerksbursch, bleich, mit zerrißnen Sohlen,

Mütz in der Hand, geduckt, ein Gäblein sich zu holen;

Mit einem Kreuzer wär ihm wohlgetan.

Doch weil ich diesen nicht in leerer Tasche trage

Und doch nicht freundlich ihm es zu gestehen wage,

Fahr ich ihn rauh abweisend an.

Ob mir das kühle Herz in rascher Scham erglüht,

Ob auch ein blut’ger Schnitt mir durch die Seele zieht:

Man sieht es nicht in meinen Blicken;

Ich habe ja gelernt, mit höhnisch leichtem Spiel

Den halberfrornen Lenz, das innere Gefühl,

Wenn es erblühen will, zu unterdrücken!

O ich war treu, wie Gold, begeistert, klar und offen;

Ein Blatt ums andre fiel von meinem grünen Hoffen,

Und taube Nüsse tauscht ich ein!

Schmach über dich, o Welt! du hast mich ganz beladen

Mit deinem Schlamm und Staub! O könnt ich rein mich baden

Im wilden Meer, sollt’s auch ein Sterben sein!

Kokett ist dies Gedicht, Naivetät erlogen

Und nur das Schnöde wahr! Ich hab euch arg betrogen,

Denn zwei geworden sind mir Herz und Mund!

Ich bin ganz euer Bild: selbstsüchtig, falsch und eitel

Und unklar in mir selbst; vom Fuße bis zur Scheitel

Ein europäisch schlechter Hund!

Gottfried Keller poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Keller, Gottfried

Karl Kraus

(1874-1936)

Die Freiheit, die ich nicht meine

Die Freiheit, die möcht’ ich echt haben,

drum möcht’ ich sie früher befrein

von solchen, die zwar recht haben,

doch ohne berechtigt zu sein.

Denn die, deren die sich erfrecht haben,

ist die Freiheit nicht, die ich mein’!

1925

Karl Kraus poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Kraus, Karl

Arthur Conan Doyle

(1859-1930)

The Bigot

The foolish Roan fondly thought

That gods must be the same to all,

Each alien idol might be brought

Within their broad Pantheon Hall.

The vision of a jealous Jove

Was far above their feeble ken;

They had no Lord who gave them love,

But scowled upon all other men.

But in our dispensation bright,

What noble progress have we made!

We know that we are in the light,

And outer races in the shade.

Our kindly creed ensures us this–

That Turk and infidel and Jew

Are safely banished from the bliss

That’s guaranteed to me and you.

The Roman mother understood

That, if the babe upon her breast

Untimely died, the gods were good,

And the child’s welfare manifest.

With tender guides the soul would go

And there, in some Elysian bower,

The tiny bud plucked here below

Would ripen to the perfect flower.

Poor simpleton! Our faith makes plain

That, if no blest baptismal word

Has cleared the babe, it bears the stain

Which faithless Adam had incurred.

How philosophical an aim!

How wise and well-conceived a plan

Which holds the new-born babe to blame

For all the sins of early man!

Nay, speak not of its tender grace,

But hearken to our dogma wise:

Guilt lies behind that dimpled face,

And sin looks out from gentle eyes.

Quick, quick, the water and the bowl!

Quick with the words that lift the load!

Oh, hasten, ere that tiny soul

Shall pay the debt old Adam owed!

The Roman thought the souls that erred

Would linger in some nether gloom,

But somewhere, sometime, would be spared

To find some peace beyond the tomb.

In those dark halls, enshadowed, vast,

They flitted ever, sad and thin,

Mourning the unforgotten past

Until they shed the taint of sin.

And Pluto brooded over all

Within that land of night and fear,

Enthroned in some dark Judgment Hall,

A god himself, reserved, austere.

How thin and colourless and tame!

Compare our nobler scheme with it,

The howling souls, the leaping flame,

And all the tortures of the pit!

Foolish half-hearted Roman hell!

To us is left the higher thought

Of that eternal torture cell

Whereto the sinner shall be brought.

Out with the thought that God could share

Our weak relenting pity sense,

Or ever condescend to spare

The wretch who gave Him just offence!

‘Tis just ten thousand years ago

Since the vile sinner left his clay,

And yet no pity can he know,