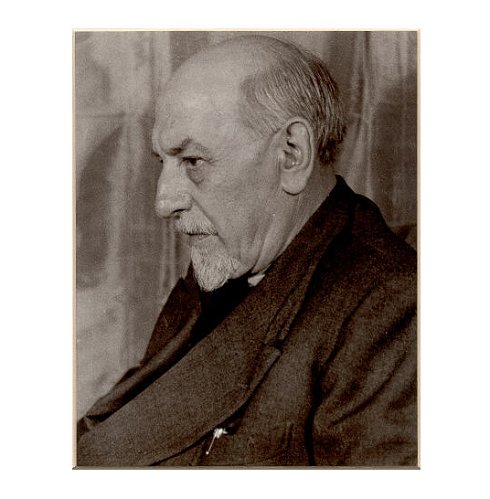

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (25)

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (25)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926). The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator by Luigi Pirandello. Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK V

3

I have laid these notes aside for some days.

They have been days of sorrow and trepidation. They are still not quite over; but now the storm, which broke with terrific force in the soul of this unhappy man whom all of us here have vied with one another in helping compassionately and with all the more devotion in that he was virtually a stranger to us all and what little we knew of him combined with his appearance and the suggestion of fatality that he conveyed to inspire in us pity and a keen interest in his most wretched plight; this storm, I say, seems to be shewing signs of gradually abating. Unless it is only a brief lull. I fear it. Often, at the height of a gale, a formidable peal of thunder succeeds in clearing the sky for a little, but presently the mass of clouds, rent asunder for a moment, return to accumulate slowly and ever more menacingly, and the gale having increased its strength breaks out afresh, more furious than before. The calm, in fact, in which Nuti’s spirit seems gradually to be gathering strength after his delirious ravings and the horrible frenzy of all these days, is tremendously dark, just like the calm of a sky in which a storm is gathering.

No one takes any notice, or seems to take any notice of this, perhaps from the need which we all feel to heave a momentary sigh of relief, saying that in any case the worst is over. We ought, we intend to adjust first, to the best of our ability, ourselves, and also everything round us, swept by the whirlwind of his madness; because there remains not only in all of us but even in the room, in the very furniture of the room, a sort of blind stupefaction, a strange uncertainty in the appearance of everything, as it were an air of hostility, suspended and diffused.

In vain do we detach ourselves from the outburst of a soul which from its profoundest depths hurls forth, broken and disordered, the most recondite thoughts, never yet confessed to itself even, its most serious and awful feelings, the strangest sensations which strip things of every familiar meaning, to give them at once another, unexpected meaning, with a truth that springs forth and imposes itself, disconcerting and terrifying. The terror is due to our recognition, with an appalling clarity, that madness dwells and lurks within each of us and that a mere trifle may let it loose: release it for a moment from the elastic web of present consciousness, and lo, all the imaginings accumulated in years past and now wandering unconnected; the fragments of a life that has remained hidden, because we could not or would not let it be reflected in ourselves by the light of reason; dubious actions, shameful falsehoods, dark hatreds, crimes meditated in the shadow of our inward selves and planned to the last detail, and forgotten memories and unconfessed desires burst in tumultuous, with diabolical fury, roaring like wild beasts. On more than one occasion, we all looked at one another with madness in our eyes, the terror of the spectacle of that madman being sufficient to release in us too for a moment the elastic net of consciousness. And even now we eye askance, and go up and touch with a sense of misgiving some object in the room which was for a moment illumined with the sinister light of a new and terrible meaning by the sick man’s hallucinations; and, going to our own rooms, observe with stupefaction and repugnance that… yes, positively, we too have been overborne by that madness, even at a distance, even when alone: we find here and there clear signs of it, pieces of furniture, all sorts of things, strangely out of place.

We ought, we intend to adjust ourselves, we need to believe that the patient is now in this state, in this brooding calm, because he is still stunned by the violence of his final outbursts and is now exhausted, worn out.

There suffices to support this deception a slight smile of gratitude which he just perceptibly offers with his lips or eyes to Signorina Luisetta: a breath, an imperceptible glimmer which does not, in my opinion, emanate from the sick man, but is rather suffused over his face by his gentle nurse, whenever she draws near and bends over the bed.

Alas, how she too is worn out, his gentle nurse! But no one gives her a thought; least of all herself. And yet the same storm has torn up and swept away this innocent creature!

It has been an agony of which as yet perhaps not even she can form any idea, because she still perhaps has not with her, within her, her own soul. She has given it to him, as a thing not her own, as a thing which he in his delirium might appropriate to derive from it refreshment and comfort.

I have been present at this agony. I have done nothing, nor could I perhaps have done anything to prevent it. But I see and confess that I am revolted by it. Which means that my feelings are compromised. Indeed, I fear that presently I may have to make another painful confession to myself.

This is what has happened: Nuti, in his delirium, mistook Signorina Luisetta for Duccella and, at first, inveighed furiously against her, shouting in her face that her obduracy, her cruelty to him were unjust, since he was in no way to blame for the death of her brother, who, of his own accord, like an idiot, like a madman, had killed himself for that woman; then, as soon as she, overcoming her first terror, grasping at once the nature of his hallucination, went compassionately to his side, lie refused to let her leave him for a moment, clasped her tightly to him, sobbing broken-heartedly or murmuring the most burning, the tenderest words of love to her, and caressing her or kissing her hands, her hair, her brow.

And she allowed him to do it. And all the rest of us allowed it. Because those words, those caresses, those embraces, those kisses were not intended for her: they were for a hallucination, in which his delirium found peace. And so we had to allow him. She, Signorina Luisetta, made her heart pitiful and loving for another girl’s sake; and this heart, thus made pitiful and loving, she gave to him, as a thing not her own, but belonging to that other girl, to Duccella. And while he appropriated that heart, she could not, must not appropriate those words, those caresses, those kisses…. But she trembled at them in every fibre of her body, poor child, ready from the first moment to feel such pity for this man who was suffering so on account of the other woman. And not on her own behalf, who did really pity him, did it come to her to feel pitiful, but for that other, whom she naturally supposes to be harsh and cruel. Well, she has given her pity to the other, that the other might pass it on to him, and by him–through the medium of Luisetta’s body–be loved and caressed in return. But love, love, who has given that? It was she that had to give it, to give love, together with her pity. And the poor child has given it. She knows, she feels that she has given it, with all her soul, with all her heart; and at the same time she must suppose that she has given it for the other.

The result has been as follows: that while he, now, is gradually returning to himself and collecting himself, and shutting himself up again darkly in his trouble; she remains empty and lost, held in suspense, without a gleam in her eye, as though she had lost her wits, a ghost, the ghost that entered into his hallucination. For him, the ghost has vanished, and with the ghost, love. But this poor child who has emptied herself to fill that ghost with herself, her love, her pity, is now herself left a ghost; and he notices nothing. He barely smiles at her in gratitude. The remedy has proved effective: the hallucination has vanished: nothing more at present, is that it?

I should not be so distressed, had I not, for all these days, seen myself obliged to bestow my pity, also, to spend myself, to run in all directions, to sit up for several nights in succession, not from a feeling that was genuinely my own, that is to say one inspired in me by Nuti, as I could have wished; but from a different feeling, one of pity indeed, but of interested pity, so interested that it made and still makes appear false and odious to me the pity which I she-wed and am still shewing for Nuti.

I feel that, as a witness of the sacrifice (without doubt involuntary) which he has made of Signorina Luisetta’s heart, I, who seek to obey my true feelings, ought to have withdrawn my pity from him. I did indeed withdraw it inwardly, to pour it all upon that poor, tormented little heart, but I continued to shew pity for him, seeing that I could do no less, compelled by her sacrifice, which was even greater. If she actually subjected herself to that torture ‘out of pity’ for him, could I, could the rest of us shrink from devotion, fatigue, proofs of Christian charity that were far less? For me to draw back meant my admitting and letting it be seen that she was undergoing this torture not ‘out of pity only’, but also ‘for love’ of him, indeed principally ‘for love’. And that could not, must not be. I have had to pretend, because she has had to believe that she was bestowing her love upon him for that other woman. And I have pretended, albeit with self-contempt, marvellously. Only in this way have I been able to modify her attitude towards myself; to make her my friend again. And yet, by shewing myself for her sake so compassionate towards Nuti, I have perhaps lost the one way that remained to me of calling her back to herself; that, namely, of proving to her that Duccella, on whose behalf she imagines that she loves him, has no reason whatever to feel any pity for him. Were I to give Duccella her true shape, her ghost, that loving and pitiful ghost, into which she, Signorina Luisetta, has transformed herself, would have to vanish, and leave her, SignorinaLuisetta, with her love ‘unjustified’ and in no way sought by him: because he has sought it from the other, not from her, and she has given it to him for the other, and not for herself, thus publicly, before us all.

Very good, but if I know that she has really given it to him, beneath this pious fiction of pity, upon which I am now weaving sophistries?

As Aldo Nuti thinks Duccella hard and cruel, so she would think me hard and cruel, were I to tear from her the veil of this pious fiction. She is a sham Duccella, simply because she is in love; and she knows that the true Duccella has not the slightest reason to be in love; she knows it from the very fact that Aldo Nuti, now that his hallucination has passed, no longer sees any sign of love in her, and sadly just thanks her for her pity.

Perhaps, at the cost of suffering a little more, she might cover herself, but only on condition that Duccella became really pitiful, upon learning the wretched plight to which her former sweetheart had been brought, and appeared in person here, by the bed upon which he lies, to give him her love again and so to save him. But Duccella will not come. And Signorina Luisetta will continue to pretend to all of us and also to herself, in good faith, that it is for her sake that she is in love with Aldo Nuti.

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (25)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shoot!