Fleurs du Mal Magazine

![]()

Zwaluwen

Het venster zoemt de cello van een bromvlieg

In zijn trapeze van glas. Scherfjes middagzon

Prikken vochtparels in de haag; het rekwisiet

voor een jong lerende spin die lenig en bon-

vivant zijn maaltijd verschalkt. Het waterballet

van muggen in de regenton is een mime

zonder slot, verklankt in het stille verzet

dat in mij sterft. Het is dat pijnlijke stramien

van gekoosde ogenblikken, die meereizen

op de vleugels van zwaluwen naar oorden ver

van mij, hoog scherend over schralende weiden,

als de herfst mijn hart drenkt in een altijd lijden.

O, goden, wie roept in een vlucht die ogen spert

om mij met erbarmen naast haar neer te vlijen.

Niels Landstra

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Landstra, Niels

![]()

Ontmoeting

Van ver

klinkt vaag uw

orgeltje van yesterday

het vloog u spelend

tegemoet vandaag en

zal nu altijd hoorbaar zijn.

Freda Kamphuis

Gedicht bij het overlijden van Rutger Kopland

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: In Memoriam, Kamphuis, Freda, Kopland, Rutger

![]()

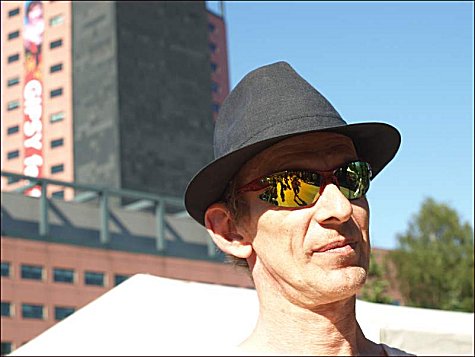

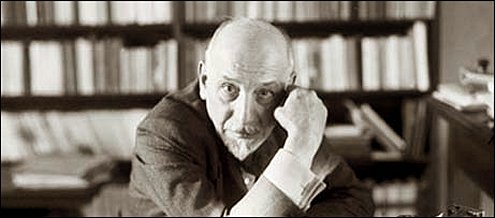

In memoriam Rutger Kopland (1934-2012)

Dichter en schrijver Rutger Kopland is woensdag 11 juli 2012 overleden. Hij is 77 jaar geworden.

Rutger Kopland is de schrijversnaam van de psychiater R.H. van den Hoofdakker (1934). Van den Hoofdakker was hoogleraar aan de Rijksuniversiteit Groningen. Als onderzoeker en behandelaar hield hij zich persoonlijk vooral bezig met de betekenis van de slaap en de biologische klok voor het emotionele leven van zowel gezonde als psychisch gestoorde mensen. Daarbij werkte hij ook als psychotherapeut. Behalve artikelen en hoofdstukken in wetenschappelijke tijdschriften en leerboeken schreef hij ook essays over psychiatrie in de algemene maatschappelijke context. Een aantal van deze stukken werd opgenomen in De mens als speelgoed (1995) en in Twee ambachten (2003).

Als Rutger Kopland publiceerde Van den Hoofdakker veertien gedichtenbundels. Hij debuteerde in 1966 met Onder het vee, zijn meest recente bundel is Toen ik dit zag, die verscheen in het najaar van 2008. Kopland schreef daarnaast literaire essays: Het mechaniek van de ontroering (1995) en Mooi, maar dat is het woord niet (1998). Al jaren behoort Kopland tot de meest gelezen dichters in ons land. Bloemlezingen uit zijn werk verschenen in onder meer in Engeland, Finland, Frankrijk, Ierland, Israel, Italië, Noorwegen, Polen en de Verenigde Staten; bundels in het Duits en Italiaans zijn in voorbereiding.

In 1999 en in 2001 ontving Van den Hoofdakker / Kopland eredoctoraten van respectievelijk de Universiteit voor Humanistiek en de Rijksuniversiteit Utrecht, in beide gevallen voor de combinatie van zijn verdiensten op wetenschappelijk en literair gebied. In 1988 ontving de dichter de P.C. Hooftprijs voor zijn oeuvre en de VSB Poëzieprijs 1998 voor zijn bundel Tot het ons loslaat.

In 2006 verschenen zijn Verzamelde gedichten ter markering van zijn veertigjarig dichterschap. Ter gelegenheid van zijn vijfenzeventigste verjaardag verscheen het boekje met cd Aan het grensland. Geluiden uit het Noorden 2. In 2008 verscheen zijn recentste bundel Toen ik dit zag. Een nieuwe druk van zijn Verzamelde gedichten waarin ook deze laatste bundel opgenomen werd, verscheen in 2010.

Bron: Uitgeverij Van Oorschot

Rutger Kopland (Goor, 4 augustus 1934 – Glimmen, 11 juli 2012)

Ars moriendi

Als het zover is – laat me dan eindelijk

weten hoe je dat kan, sterven

hoe je kan weggaan, weg

zou het iets hebben van wat er in mij

gebeurt wanneer een choraal van Bach klinkt:

er welt een gevoel op, een besef van onontkoombaar

verlies maar het geeft niet, nu even niet

het heeft misschien ook iets van het zien van

een uitzicht over de bergen, die lucht en leegte

en de huiver voor de eenzaamheid die in die verte

op mij wacht, maar het geeft niet, nu even niet

af en toe is er zo’n avond dat er over de wereld

het mooiste licht valt dat er is, laat laag licht

en dat ik denk: dit was het dus

als het zover is – laat me dan eindelijk

weten hoe het is om te zeggen: ik kom

Rutger Kopland overleden

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, In Memoriam, Kopland, Rutger

William Shakespeare

(1564-1616)

THE SONNETS

Sonnet 135

Whoever hath her wish, thou hast thy will,

And ‘Will’ to boot, and ‘Will’ in over-plus,

More than enough am I that vex thee still,

To thy sweet will making addition thus.

Wilt thou whose will is large and spacious,

Not once vouchsafe to hide my will in thine?

Shall will in others seem right gracious,

And in my will no fair acceptance shine?

The sea all water, yet receives rain still,

And in abundance addeth to his store,

So thou being rich in will add to thy will

One will of mine to make thy large will more.

Let no unkind, no fair beseechers kill,

Think all but one, and me in that one ‘Will.’

![]()

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shakespeare Sonnets

Iers gedicht

vertaald door Lauran Toorians

Ut dixit Gráinne ingen Chormaic fri Finn:

Fil duine

frismad buide lemm díuterc,

ara tabrinn in mbith mbuide

huile, huile, cid díupert.

Zoals Gráinne, de dochter van Cormac, zei tegen Finn:

Er is een man

die ik zou willen zien,

voor wie ik de gouden aarde geven zou,

alles, alles, al was het voor niets.

Middeleeuwse Ierse gedichten vertaald door Lauran Toorians

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: CELTIC LITERATURE, Lauran Toorians

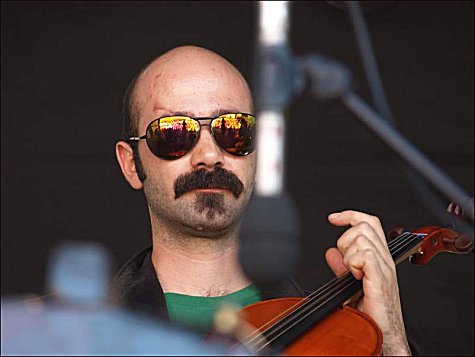

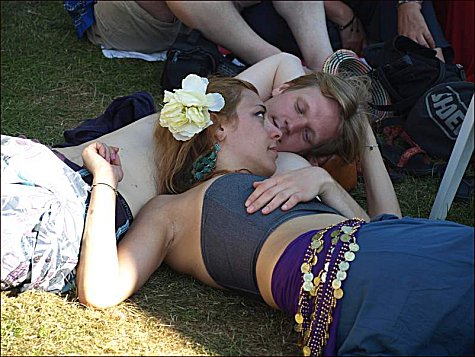

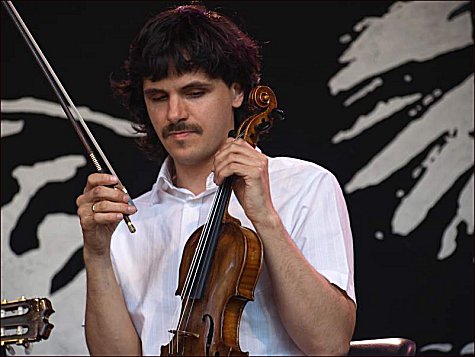

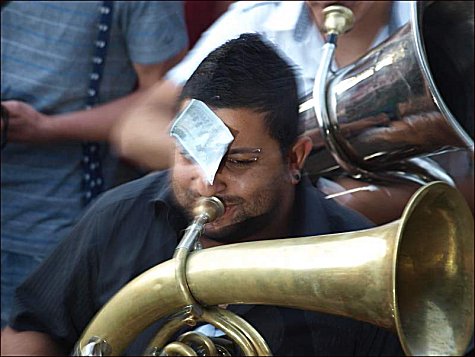

Op het 16e International Gipsyfestival: Doorspelen!

Het International Gipsyfestival beleefde op 2e Pinksterdag zijn 16e editie in de Tilburgse Interpolistuin. Ik vind het elk jaar weer een genot om er rond te lopen, te luisteren, te kijken en – vooral – te fotograferen. Er lopen veel mensen met een camera en die richten ze vooral op de muzikanten, danseressen en andere artiesten. Zelf vind ik het publiek minstens zo fotogeniek.

In de loop der jaren kom je steeds weer dezelfde gezichten tegen. Zoals die ene Duitse die er in haar felrood folkloristisch kostuum nog zigeunerachtiger uit lijkt te zien dan de echte Roma. (Het fototoestel in haar handen vormt daarmee weer een merkwaardig contrast). Of zoals die ene man die altijd aan het tekenen is. Edgar Jansen heet hij. En hij blijkt een rijkgevulde website te hebben met muziek- en danstekeningen en portretten; (zie: www.edgarportraits.com). Zo zijn er wel meer oude bekenden – mensen die je groet, ook als je hun naam niet kent.

Het festival eindigde ditmaal officieel na het overdonderende optreden van de Band of Gipsy’s – andere koek dan destijds Jimi Hendrix c.s. uiteraard maar ook behoorlijk opzwepend: een gelegenheidsformatie van Taraf de Haïdouks en Kocani Orkestar. Maar mooier nog vond ik wat daarna gebeurde, naar ik vermoed gewoon spontaan. De blazers van de band trokken als een ouderwets looporkest van het ene podium naar het andere om daarvoor temidden van het publiek een serenade te brengen aan de mensen die het allemaal mogelijk maken, de organisatoren en vrijwilligers. Tenminste, zo leek het mij op afstand. En of ik gelijk heb of niet, zo was het. En het mooiste moment brak aan toen de loftrompetten gestoken werden op Albert Siebelink. De door een ernstige ziekte getroffen geestelijke vader van het festival kwam er zelfs even voor uit zijn rolstoel om mee te swingen.

En daarna ging de onvermoeibare troep weer verder. Hoe lang duurde die toegift eigenlijk? Tien minuten, twintig, een half uur of nog langer? Er werden zelfs biljetten van vijf en tien op muzikantenhoofden geplakt met de boodschap: doorspelen! Ze mochten gewoon niet ophouden…

Joep Eijkens

Joep Eijkens foto’s en tekst:

16e International Gipsyfestival. Doorspelen!

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Joep Eijkens Photos

Ernst Stadler

(1883-1914)

Beata Beatrix

D. G. R.

Dämmerläuten schüttet in den veilchenblauen Abend

weiße Blütenflocken. Kleine Flocken

blank wie Muschelperlen rieseln· tanzen·

schwärmen weich wie dünne blasse Daunen·

wirbelnd· wölkend. Schwere Blütenbäume

streuen goldne Garben. Wilde Gärten

tragen mich in blaue Wundernächte·

große wilde Gärten. Tiefe Beete

schwanken brennend auf· wie Traumgewässer

still und spiegelnd. Silberkähne heben

mich von braunen Uferwiesen

in das Leuchten. Über Scharlachfluten

dunklen Mohns· der rot in Flammensäulen

züngelt· treibt der Nachen. Bleiche Lilien

tropfen schillernd drüberhin wie Wellen.

Düfte aus kristallnen Nächten tauchend·

schlingen wirr und hängen sich ins Haar·

und sie locken . . leise· leise . .

und die grünen klaren Tiefen flimmern . .

Purpurstrahlen schießen . . leise sink ich . .

süß umfängt mich müder Laut von Geigen . .

schwingt· sinkt· gleitende Paläste

funkeln fern. Licht stürzt

über mich. Weit· grün

schwebt ein Glänzen .

1904

Ernst Stadler poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: *War Poetry Archive, - Archive Tombeau de la jeunesse, Archive S-T, Archive S-T, Stadler, Ernst

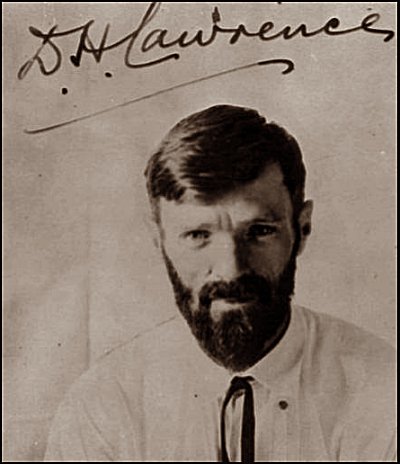

D. H. Lawrence

(1885-1930)

Whales Weep Not!

They say the sea is cold, but the sea contains

the hottest blood of all, and the wildest, the most urgent.

All the whales in the wider deeps, hot are they, as they urge

on and on, and dive beneath the icebergs.

The right whales, the sperm-whales, the hammer-heads, the killers

there they blow, there they blow, hot wild white breath out of

the sea!

And they rock, and they rock, through the sensual ageless ages

on the depths of the seven seas,

and through the salt they reel with drunk delight

and in the tropics tremble they with love

and roll with massive, strong desire, like gods.

Then the great bull lies up against his bride

in the blue deep bed of the sea,

as mountain pressing on mountain, in the zest of life:

and out of the inward roaring of the inner red ocean of whale-blood

the long tip reaches strong, intense, like the maelstrom-tip, and

comes to rest

in the clasp and the soft, wild clutch of a she-whale’s

fathomless body.

And over the bridge of the whale’s strong phallus, linking the

wonder of whales

the burning archangels under the sea keep passing, back and

forth,

keep passing, archangels of bliss

from him to her, from her to him, great Cherubim

that wait on whales in mid-ocean, suspended in the waves of the

sea

great heaven of whales in the waters, old hierarchies.

And enormous mother whales lie dreaming suckling their whale-

tender young

and dreaming with strange whale eyes wide open in the waters of

the beginning and the end.

And bull-whales gather their women and whale-calves in a ring

when danger threatens, on the surface of the ceaseless flood

and range themselves like great fierce Seraphim facing the threat

encircling their huddled monsters of love.

And all this happens in the sea, in the salt

where God is also love, but without words:

and Aphrodite is the wife of whales

most happy, happy she!

and Venus among the fishes skips and is a she-dolphin

she is the gay, delighted porpoise sporting with love and the sea

she is the female tunny-fish, round and happy among the males

and dense with happy blood, dark rainbow bliss in the sea.

D.H. Lawrence poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, D.H. Lawrence, Lawrence, D.H.

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (24)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926) The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator by Luigi Pirandello. Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK V

2

“Then it is a serious matter?” Cavalena came to my room, mysteriously,this morning to ask me. The poor man had three handkerchiefs in his hand. At a certain point in the conversation, after many expressions of pity for that “dear Baron” (to wit, Nuti), and many observations touching the innumerable misfortunes of the human race, as though they were a proof of these misfortunes he spread out before me the three handkerchiefs, one after another, exclaiming:

“Look!”

They were all three in holes, as though they had been gnawed by mice. I gazed at them with pity and wonder; after which I gazed at him, shewing plainly that I did not understand. Cavalena sneezed, or rather, I thought that he had sneezed. Not at all. He had said:

“Piccini.”

Seeing that I still gazed at him with that air of bewilderment, he shewed me the handkerchiefs once more and repeated:

“Piccini.”

“The little dog?”

He shut his eyes and nodded his head with a tragic solemnity.

“A hard worker, it seems,” said I.

“And I must not say a word!” exclaimed Cavalena. “Because she is the one creature here, in my house, by whom my wife feels herself loved, and is not afraid of her playing her false. Ah, Signor Gubbio, nature is really wicked, believe me. No misfortune can be greater or worse than mine. To have a wife who feels that no one loves her but a dog! And it is not true, you know. That animal does not love anyone. My wife loves her, and do you know why? Because it is only with that animal that she can play at having a heart in her bosom that is overflowing with charity. And you should see how she consoles herself!

A tyrant with all the rest of us, the woman becomes a slave to an old, ugly animal; ugly isn’t the word–you’ve seen it?–with claws like bill-hooks and bleared eyes. … And she loves it all the more now that she sees that an antipathy has been growing up for some time between the dog and me, an antipathy, Signor Gubbio, that is insuperable! Insuperable! That nasty beast, being quite certain that I, who know how she is protected by her mistress, will never give her the kick that would turn her inside out, reduce her–I swear to you, Signor Gubbio–to a jelly, shews me with the most irritating calmness every possible and imaginable sign of contempt, she positively insults me: she is always dirtying the carpet in my study; she lies on the armchairs, on the sofa in my study; she refuses her food and gnaws all my dirty linen: look at these, three handkerchiefs, yesterday, not to mention shirts, table-napkins, towels, pillow-slips; and I have to admire her and thank her, because do you know what this gnawing means to my wife? Affection! I assure you. It means that the dog smells her masters’ scent. ‘But how? When she eats it?’ ‘She doesn’t know what she is doing,’ would be my wife’s answer. She has destroyed more than half our linen-cupboard. I have to keep quiet, put a stopper in, otherwise my wife would at once find an excuse for reminding me once again, in so many words, of my own brutality. That’s just how it is! A fortunate thing, Signor Gubbio, a fortunate thing, as I always say, that I am a Doctor! I am bound, as a Doctor, to realise that this passionate adoration for an animal is merely another symptom of the disease! Typical, don’t you know?”

He stood gazing at me for a while, undecided, perplexed: then, pointing to a chair, asked:

“May I?”

“Why, of course!” I told him.

He sat down; studied one of the handkerchiefs, shaking his head, then, with a wan, almost imploring smile:

“I am not in your way, am I? I am not disturbing you?”

I assured him warmly that he was not disturbing me in the least.

“I know, I can see that you are a warmhearted man… let me say it, a quiet man, but a man who can understand and feel for other people. And I…”

He broke off, with a worried expression, listened intently, then sprang to his feet:

“I think that was Luisetta calling me….”

I too listened for a moment, then said:

“No, I don’t think so.”

Sorrowfully he raised his hands to his wig and straightened it on his head.

“Do you know what Luisetta said to me yesterday? ‘Daddy, don’t start again.’ You see before you, Signor Grubbio, an exasperated man. Inevitably. Shut up here in the house from morning to night, without ever setting eyes on anyone, shut out from life, I can never find any outlet for my rage at the injustice of my fate! And Luisetta tells me that I drive all the lodgers away!”

“Oh, but I…” I began to protest.

“No, it is true, you know, it is true!” Cavalena interrupted me. “And, you, since you are so kind, must promise me that as soon as I begin to bore you, as soon as I am in your way, you will take me by the scruff of my neck and fling me out of the room! Promise me that, please. Eight away; you must give me your hand and promise.”

I gave him my hand, smiling:

“There… just as you please… to satisfy you.”

“Thank you! Now I feel more at my ease. I am conscious, Signor Gubbio, you wouldn’t believe! Conscious, do you know of what? Of being no longer myself! When a man reaches this depth, that is when he loses all sense of shame at his own disgrace, he is finished! But I should never have lost that sense of shame! I was too jealous of my dignity! It was that woman made me lose it, crying her madness aloud. My disgrace is known to everyone from now onwards? And it is obscene, obscene, obscene.”

“But no… why?”

“Obscene!” shouted Cavalena. “Would you care to see it? Look! Here it is!”

And so speaking, he seized his wig between his fingers and plucked it from his head. I was left thunderstruck, gazing at that bare, pallid scalp, the scalp of a flayed goat, while Cavalena, the tears starting to his eyes, went on:

“Tell me, can it help being obscene, the disgrace of a man reduced to this state, whose wife is still jealous?”

“But you are a Doctor! You know that it is a disease!” I made haste to remind him, greatly distressed, raising my hands as though to help him to replace the wig on his head.

He settled it in its place, and said:

“But it is precisely because I am a Doctor and know that it is a disease, Signor Gubbio! That is the disgrace! That I am a Doctor! If I could only not know that she did it from madness, I should turn her out of the house, don’t you see? Procure a separation from her, defend my own dignity at all costs. But I am a Doctor! I know that she is mad! And I know therefore that it is my duty to have sense for two, for myself and for her who has lost hers! But to have sense, for a madwoman, when her madness is so supremely ridiculous, Signor Gubbio, what does it mean? It means covering myself with ridicule, of course! It means resigning myself to endure the holocaust that madwoman makes of my dignity, before our daughter, before the servants, before everyone, in public; and so I lose all shame at my own disgrace!”

“Papa!”

Ah, this time, yes; it really was Signorina Luisetta calling.

Cavalena at once controlled himself, straightened his wig carefully, cleared his throat by way of changing his voice, and struck a sweet little playful, caressing note in which to answer:

“Here I am, Sesè.”

And he hurried out, making a sign to me, with his finger, to be silent.

I too, shortly afterwards, left my room, to pay Nuti a visit. I listened for a moment outside the door of his room. Silence. Perhaps he was asleep. I stood there for a while in perplexity, then looked at my watch: it was already time for me to be going to the Kosmograph; only I did not wish to leave him, particularly as Polacco had expressly enjoined me to bring him with me. All of a sudden, I thought I heard what sounded like a deep sigh, a sigh of anguish. I knocked at the door. Nuti, from his bed, answered:

“Come in.”

I went in. The room was in darkness. I went up to the bed. Nuti said:

“I think… I think I have a temperature. …”

I leaned over him; I felt one of his hands. It was trembling.

“Why, yes!” I exclaimed. “You have a temperature, and a high one. Wait a minute. I am going to call Signor Cavalena. Our landlord is a Doctor,”

“No, don’t bother… it will pass off!” he said. “I have been working too hard.”

“Quite so,” I replied. “But why won’t you let me call in Cavalena? It will pass away all the sooner. Do you mind if I open the shutters a little?”

I looked at him by daylight; his appearance terrified me. His face was a brick red, hard, grim, rigid; the whites of his eyes, bloodshot overnight, were now almost black between their horribly swollen lids; his straggling moustache was glued to his parched, tumid, gaping lips.

“You must be feeling really bad.”

“Yes, I do feel bad…” he said. “My head.”

And he drew a hand from beneath the blankets to lay it with his fist clenched on his forehead.

I went to call Cavalena who was still talking to his daughter at the end of the passage. Signorina Luisetta, seeing me approach, stared at me with an icy frown.

She evidently supposed that her father had already found an outlet in me. Alas, I find myself unjustly condemned to atone thus for the excessive confidence which her father places in me.

Signorina Luisetta is my enemy already. But not only because of her father’s excessive confidence in me, because also of the presence of another lodger in the house. The feeling aroused in her by this other lodger from the first moment rules out any friendliness towards me. I noticed this immediately. It is useless to argue about it. It is one of those secret, instinctive impulses by which our mental attitudes are determined and which at any moment, without any apparent reason, alter the relations between one person and another. Now, certainly, her ill-feeling will be increased by the tone of voice and the manner in which I–having noticed this–almost unconsciously, announced that Aldo Nuti was lying in bed, in his room, with a high temperature. She turned deathly pale, first of all; then blushed a deep crimson. Perhaps at that very moment she became aware of her still undefined feeling of aversion towards myself.

Cavalena at once hurried to Nuti’s room; she stopped outside the door, as though she did not wish me to enter; so that I was obliged to say to her:

“May I pass, please?”

But a moment later, that is to say when her father told her to go and fetch the thermometer to take Nuti’s temperature, she came into the room also. I did not take my eyes from her face for a moment, and saw that she, feeling that I was looking at her, was making a violent effort to conceal the mingled pity and dismay which the sight of Nuti inspired in her.

The examination was prolonged. But, apart from a high fever and headache, Cavalena was unable to diagnose anything. When we had left the room, however, after fastening the shutters again, so that the patient should not be dazzled by the light, Cavalena shewed signs of the utmost consternation. He is afraid that it may be an inflammation of the brain.

“We must send for another Doctor at once, Signor Gubbio! I, especially as I am the owner of the house, you understand, cannot assume responsibility for an illness which I consider serious.”

He gave me a note for this other Doctor, his friend, who receives calls at the neighbouring chemist’s, and I went off to leave the note and then, being already behind my time, hastened to the Kosmograph.

I found Polacco on tenterhooks, bitterly repenting his having let Nuti in for this mad enterprise. He says that he could never, never have imagined that he would see him in the state in which he suddenly appeared, unexpectedly, because from his letters written first from Russia, then from Germany, afterwards from Switzerland, there was nothing to be made. He wished to shew me these letters, in self-defence; but then, all at once, seemed to have forgotten them. The news of the illness has almost made him cheerful, it has at any rate taken a great weight off his mind for the moment.

“Inflammation of the brain? I say, Gubbio, if he should die…. By Jove, when a man has worked himself into that state, when he has become a danger to himself and to other people, death… you might almost say… But let us hope not; let us hope it is a good sign. It often is, one never knows. I am sorry for you, poor Gubbio, and also for that poor Cavalena…. What a business…. I shall come and see you this evening. But it’s providential, you know. So far, he has seen nobody here except yourself; nobody knows that he is here. Mum’s the word, eh! You said to me that it would be advisable to relieve Ferro of his part in the tiger film!

“But without letting him suppose…”

“Simpleton! You are talking to me. I have thought of everything. Listen: yesterday afternoon, shortly after you people left, I had a visit from the Nestoroff.”

“Indeed? Here?”

“She must have felt in the air that Nuti had come. My dear fellow, she’s in a great fright! Frightened of Ferro, not of Nuti. She came to ask me… like that, just as if it was nothing at all, whether it was really necessary that she should continue to come to the Kosmograph, or for that matter remain in Rome, as soon as, in a few days from now, all four companies are employed on the tiger film, in which she is not to take part. Do you follow? I caught the ball on the rebound. I answered that Commendator Borgalli’s orders were that, before all four companies were amalgamated, we should finish the three or four films that have been hung up for various nature scenes, which will have to be taken out of Rome. There’s that one of the Otranto sailors, the story Bertini gave us. ‘But I have no part in it,’ said the Nestoroff. ‘I know that,’ I told her, ‘but Ferro has a part in it, the chief part, and it might be better perhaps, more convenient for us, if we were to release him from the part he is taking in the tiger film and send him down South with Bertini. But perhaps he won’t agree. Now, if you were to persuade him, Signora Nestoroff.’ She looked me in the face for a time… you know how she does… then said: ‘I might be able to….’ And finally, after thinking it over, ‘In that case, he would go down there by himself; I should remain here, in his place, to take some part, even a minor part, in the tiger film….'”

“Ah, no, in that case, no!” I could not help interrupting Polacco. “Carlo Ferro will not go down there by himself, you may be certain of that!”

Polacco began to laugh.

“Simpleton! If she really wishes it, you may I be quite sure he will go! He would go to hell I for her!”

“I don’t understand. Why does she wish to remain here?”

“But it’s not true. She says she does…. Don’t you understand that she’s pretending, so as not to let me see that she’s afraid of Nuti? She will go too, you’ll see. Or perhaps… or perhaps… who knows? She may really wish to remain, to meet Nuti here by herself, without interference, and make him give up the whole idea. She is capable of that and of more; she is capable of anything. Oh, what a business! Come along; let us get to work. Tell me, though: Signorina Luisetta? She simply must come here for the rest of that film.”

I told him of Signora Nene’s rage, and that Cavalena, the day before, had come to return (albeit unwillingly, so far as he was concerned) the money and the presents. Polacco said once more that he would come, this evening, to Cavalena’s, to persuade him and Signora Nene to send Signorina Luisetta back to the Kosmograph. We were by this time at the entrance to the Positive Department: I ceased to be Gubbio and became a hand.

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (24)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shoot!

Wandering At Morn

Wandering at morn,

Emerging from the night, from gloomy thoughts–thee in my thoughts,

Yearning for thee, harmonious Union! thee, Singing Bird divine!

Thee, seated coil’d in evil times, my Country, with craft and black

dismay–with every meanness, treason thrust upon thee;

–Wandering–this common marvel I beheld–the parent thrush I

watch’d, feeding its young,

(The singing thrush, whose tones of joy and faith ecstatic,

Fail not to certify and cheer my soul.)

There ponder’d, felt I,

If worms, snakes, loathsome grubs, may to sweet spiritual songs be

turn’d,

If vermin so transposed, so used, so bless’d may be, 10

Then may I trust in you, your fortunes, days, my country;

–Who knows that these may be the lessons fit for you?

From these your future Song may rise, with joyous trills,

Destin’d to fill the world.

Walt Whitman

(1819-1892)

Hans Hermans photos – Natuurdagboek 04-12

Gedicht Walt Whitman

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Hans Hermans Photos, Whitman, Walt

William Shakespeare

(1564-1616)

THE SONNETS

Sonnet 134

So now I have confessed that he is thine,

And I my self am mortgaged to thy will,

My self I’ll forfeit, so that other mine,

Thou wilt restore to be my comfort still:

But thou wilt not, nor he will not be free,

For thou art covetous, and he is kind,

He learned but surety-like to write for me,

Under that bond that him as fist doth bind.

The statute of thy beauty thou wilt take,

Thou usurer that put’st forth all to use,

And sue a friend, came debtor for my sake,

So him I lose through my unkind abuse.

Him have I lost, thou hast both him and me,

He pays the whole, and yet am I not free.

![]()

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shakespeare Sonnets

Father writes Amy Winehouse’s biography:

‘Amy, My Daughter’

‘Amy, My Daughter’, a deeply intimate and moving account of Amy Winehouse’s life is published yesterday in the UK. Documenting Amy’s earlier years, her rise to stardom and struggles with addiction, and including never before seen pictures of Amy, the book will bring the many layers of her life together – the personal, the private and the public – to create a fitting tribute and celebration of her life.

Written by Mitch Winehouse, all author proceeds from every copy sold will be donated to the Amy Winehouse Foundation, the charity set up in Amy’s name. The charity provides help, support or care for young people, especially those who are in need by reason of ill health, disability, financial disadvantage or addiction.

Amy, My Daughter by Mitch Winehouse

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #Biography Archives, Amy Winehouse, Amy Winehouse, Exhibition Archive

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature