Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

The She-Wolf

Leonard Bilsiter was one of those people who have failed to find this world attractive or interesting, and who have sought compensation in an “unseen world” of their own experience or imagination — or invention.

Children do that sort of thing successfully, but children are content to convince themselves, and do not vulgarise their beliefs by trying to convince other people. Leonard Bilsiter’s beliefs were for “the few,” that is to say, anyone who would listen to him.

His dabblings in the unseen might not have carried him beyond the customary platitudes of the drawing-room visionary if accident had not reinforced his stock-intrade of mystical lore. In company with a friend, who was interested in a Ural mining concern, he had made a trip across Eastern Europe at a moment when the great Russian railway strike was developing from a threat to a reality; its outbreak caught him on the return journey, somewhere on the further side of Perm, and it was while waiting for a couple of days at a wayside station in a state of suspended locomotion that he made the acquaintance of a dealer in harness and metalware, who profitably whiled away the tedium of the long halt by initiating his English travelling companion in a fragmentary system of folk-lore that he had picked up from Trans–Baikal traders and natives.

His dabblings in the unseen might not have carried him beyond the customary platitudes of the drawing-room visionary if accident had not reinforced his stock-intrade of mystical lore. In company with a friend, who was interested in a Ural mining concern, he had made a trip across Eastern Europe at a moment when the great Russian railway strike was developing from a threat to a reality; its outbreak caught him on the return journey, somewhere on the further side of Perm, and it was while waiting for a couple of days at a wayside station in a state of suspended locomotion that he made the acquaintance of a dealer in harness and metalware, who profitably whiled away the tedium of the long halt by initiating his English travelling companion in a fragmentary system of folk-lore that he had picked up from Trans–Baikal traders and natives.

Leonard returned to his home circle garrulous about his Russian strike experiences, but oppressively reticent about certain dark mysteries, which he alluded to under the resounding title of Siberian Magic. The reticence wore off in a week or two under the influence of an entire lack of general curiosity, and Leonard began to make more detailed allusions to the enormous powers which this new esoteric force, to use his own description of it, conferred on the initiated few who knew how to wield it. His aunt, Cecilia Hoops, who loved sensation perhaps rather better than she loved the truth, gave him as clamorous an advertisement as anyone could wish for by retailing an account of how he had turned a vegetable marrow into a wood pigeon before her very eyes. As a manifestation of the possession of supernatural powers, the story was discounted in some quarters by the respect accorded to Mrs. Hoops’ powers of imagination.

However divided opinion might be on the question of Leonard’s status as a wonderworker or a charlatan, he certainly arrived at Mary Hampton’s house-party with a reputation for preeminence in one or other of those professions, and he was not disposed to shun such publicity as might fall to his share. Esoteric forces and unusual powers figured largely in whatever conversation he or his aunt had a share in, and his own performances, past and potential, were the subject of mysterious hints and dark avowals.

“I wish you would turn me into a wolf, Mr. Bilsiter,” said his hostess at luncheon the day after his arrival.

“My dear Mary,” said Colonel Hampton, “I never knew you had a craving in that direction.”

“A she-wolf, of course,” continued Mrs. Hampton; “it would be too confusing to change one’s sex as well as one’s species at a moment’s notice.”

“I don’t think one should jest on these subjects,” said Leonard.

“I’m not jesting, I’m quite serious, I assure you. Only don’t do it today; we have only eight available bridge players, and it would break up one of our tables. To-morrow we shall be a larger party. To-morrow night, after dinner —”

“In our present imperfect understanding of these hidden forces I think one should approach them with humbleness rather than mockery,” observed Leonard, with such severity that the subject was forthwith dropped.

Clovis Sangrail had sat unusually silent during the discussion on the possibilities of Siberian Magic; after lunch he side-tracked Lord Pabham into the comparative seclusion of the billiard-room and delivered himself of a searching question.

“Have you such a thing as a she-wolf in your collection of wild animals? A she-wolf of moderately good temper?”

Lord Pabham considered. “There is Loiusa,” he said, “a rather fine specimen of the timber-wolf. I got her two years ago in exchange for some Arctic foxes. Most of my animals get to be fairly tame before they’ve been with me very long; I think I can say Louisa has an angelic temper, as she-wolves go. Why do you ask?”

“I was wondering whether you would lend her to me for tomorrow night,” said Clovis, with the careless solicitude of one who borrows a collar stud or a tennis racquet.

“To-morrow night?”

“Yes, wolves are nocturnal animals, so the late hours won’t hurt her,” said Clovis, with the air of one who has taken everything into consideration; “one of your men could bring her over from Pabham Park after dusk, and with a little help he ought to be able to smuggle her into the conservatory at the same moment that Mary Hampton makes an unobtrusive exit.”

Lord Pabham stared at Clovis for a moment in pardonable bewilderment; then his face broke into a wrinkled network of laughter.

“Oh, that’s your game, is it? You are going to do a little Siberian Magic on your own account. And is Mrs. Hampton willing to be a fellow-conspirator?”

“Mary is pledged to see me through with it, if you will guarantee Louisa’s temper.”

“I’ll answer for Louisa,” said Lord Pabham.

By the following day the house-party had swollen to larger proportions, and Bilsiter’s instinct for self-advertisement expanded duly under the stimulant of an increased audience. At dinner that evening he held forth at length on the subject of unseen forces and untested powers, and his flow of impressive eloquence continued unabated while coffee was being served in the drawing-room preparatory to a general migration to the card-room.

His aunt ensured a respectful hearing for his utterances, but her sensation-loving soul hankered after something more dramatic than mere vocal demonstration.

“Won’t you do something to convince them of your powers, Leonard?” she pleaded; “change something into another shape. He can, you know, if he only chooses to,” she informed the company.

“Oh, do,” said Mavis Pellington earnestly, and her request was echoed by nearly everyone present. Even those who were not open to conviction were perfectly willing to be entertained by an exhibition of amateur conjuring.

Leonard felt that something tangible was expected of him.

“Has anyone present,” he asked, “got a three-penny bit or some small object of no particular value —?”

“You’re surely not going to make coins disappear, or something primitive of that sort?” said Clovis contemptuously.

“I think it very unkind of you not to carry out my suggestion of turning me into a wolf,” said Mary Hampton, as she crossed over to the conservatory to give her macaws their usual tribute from the dessert dishes.

“I have already warned you of the danger of treating these powers in a mocking spirit,” said Leonard solemnly.

“I don’t believe you can do it,” laughed Mary provocatively from the conservatory; “I dare you to do it if you can. I defy you to turn me into a wolf.”

As she said this she was lost to view behind a clump of azaleas.

“Mrs. Hampton —” began Leonard with increased solemnity, but he got no further. A breath of chill air seemed to rush across the room, and at the same time the macaws broke forth into ear-splitting screams.

“What on earth is the matter with those confounded birds, Mary?” exclaimed Colonel Hampton; at the same moment an even more piercing scream from Mavis Pellington stampeded the entire company from their seats. In various attitudes of helpless horror or instinctive defence they confronted the evil-looking grey beast that was peering at them from amid a setting of fern and azalea.

Mrs. Hoops was the first to recover from the general chaos of fright and bewilderment.

“Leonard!” she screamed shrilly to her nephew, “turn it back into Mrs. Hampton at once! It may fly at us at any moment. Turn it back!”

“I— I don’t know how to,” faltered Leonard, who looked more scared and horrified than anyone.

“What!” shouted Colonel Hampton, “you’ve taken the abominable liberty of turning my wife into a wolf, and now you stand there calmly and say you can’t turn her back again!”

To do strict justice to Leonard, calmness was not a distinguishing feature of his attitude at the moment.

“I assure you I didn’t turn Mrs. Hampton into a wolf; nothing was farther from my intentions,” he protested.

“Then where is she, and how came that animal into the conservatory?” demanded the Colonel.

“Of course we must accept your assurance that you didn’t turn Mrs. Hampton into a wolf,” said Clovis politely, “but you will agree that appearances are against you.”

“Are we to have all these recriminations with that beast standing there ready to tear us to pieces?” wailed Mavis indignantly.

“Lord Pabham, you know a good deal about wild beasts —” suggested Colonel Hampton.

“The wild beasts that I have been accustomed to,” said Lord Pabham, “have come with proper credentials from well-known dealers, or have been bred in my own menagerie. I’ve never before been confronted with an animal that walks unconcernedly out of an azalea bush, leaving a charming and popular hostess unaccounted for. As far as one can judge from outward characteristics,” he continued, “it has the appearance of a well-grown female of the North American timber-wolf, a variety of the common species canis lupus.”

“Oh, never mind its Latin name,” screamed Mavis, as the beast came a step or two further into the room; “can’t you entice it away with food, and shut it up where it can’t do any harm?”

“If it is really Mrs. Hampton, who has just had a very good dinner, I don’t suppose food will appeal to it very strongly,” said Clovis.

“Leonard,” beseeched Mrs. Hoops tearfully, “even if this is none of your doing can’t you use your great powers to turn this dreadful beast into something harmless before it bites us all — a rabbit or something?”

“I don’t suppose Colonel Hampton would care to have his wife turned into a succession of fancy animals as though we were playing a round game with her,” interposed Clovis.

“I absolutely forbid it,” thundered the Colonel.

“Most wolves that I’ve had anything to do with have been inordinately fond of sugar,” said Lord Pabham; “if you like I’ll try the effect on this one.”

He took a piece of sugar from the saucer of his coffee cup and flung it to the expectant Louisa, who snapped it in mid-air. There was a sigh of relief from the company; a wolf that ate sugar when it might at the least have been employed in tearing macaws to pieces had already shed some of its terrors. The sigh deepened to a gasp of thanks-giving when Lord Pabham decoyed the animal out of the room by a pretended largesse of further sugar. There was an instant rush to the vacated conservatory. There was no trace of Mrs. Hampton except the plate containing the macaws’ supper.

“The door is locked on the inside!” exclaimed Clovis, who had deftly turned the key as he affected to test it.

Everyone turned towards Bilsiter.

“If you haven’t turned my wife into a wolf,” said Colonel Hampton, “will you kindly explain where she has disappeared to, since she obviously could not have gone through a locked door? I will not press you for an explanation of how a North American timber-wolf suddenly appeared in the conservatory, but I think I have some right to inquire what has become of Mrs. Hampton.”

Bilsiter’s reiterated disclaimer was met with a general murmur of impatient disbelief.

“I refuse to stay another hour under this roof,” declared Mavis Pellington.

“If our hostess has really vanished out of human form,” said Mrs. Hoops, “none of the ladies of the party can very well remain. I absolutely decline to be chaperoned by a wolf!”

“It’s a she-wolf,” said Clovis soothingly.

The correct etiquette to be observed under the unusual circumstances received no further elucidation. The sudden entry of Mary Hampton deprived the discussion of its immediate interest.

“Some one has mesmerised me,” she exclaimed crossly; “I found myself in the game larder, of all places, being fed with sugar by Lord Pabham. I hate being mesmerised, and the doctor has forbidden me to touch sugar.”

The situation was explained to her, as far as it permitted of anything that could be called explanation.

“Then you really did turn me into a wolf, Mr. Bilsiter?” she exclaimed excitedly.

But Leonard had burned the boat in which he might now have embarked on a sea of glory. He could only shake his head feebly.

“It was I who took that liberty,” said Clovis; “you see, I happen to have lived for a couple of years in North–Eastern Russia, and I have more than a tourist’s acquaintance with the magic craft of that region. One does not care to speak about these strange powers, but once in a way, when one hears a lot of nonsense being talked about them, one is tempted to show what Siberian magic can accomplish in the hands of someone who really understands it. I yielded to that temptation. May I have some brandy? the effort has left me rather faint.”

If Leonard Bilsiter could at that moment have transformed Clovis into a cockroach and then have stepped on him he would gladly have performed both operations.

The She-Wolf

From ‘Beasts and Super-Beasts’

by Saki (H. H. Munro)

(1870 – 1916)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Saki, Saki, The Art of Reading

THE HOME-COMING OF ‘RASTUS SMITH

There was a great commotion in that part of town which was known as “Little Africa,” and the cause of it was not far to seek. Contrary to the usual thing, this cause was not an excursion down the river, nor a revival, baptising, nor an Emancipation Day celebration. None of these was it that had aroused the denizens of “Little Africa,” and kept them talking across the street from window to window, from door to door, through alley gates, over backyard fences, where they stood loud-mouthed and arms akimboed among laden clothes lines. No, the cause of it all was that Erastus Smith, Aunt Mandy Smith’s boy, who had gone away from home several years before, and who, rumour said, had become a great man, was coming back, and “Little Africa,” from Douglass Street to Cat Alley, was prepared to be dazzled. So few of those who had been born within the mile radius which was “Little Africa” went out into the great world and came into contact with the larger humanity that when one did he became a man set apart. And when, besides, he went into a great city and worked for a lawyer whose name was known the country over, the place of his birth had all the more reason to feel proud of her son.

So there was much talk across the dirty little streets, and Aunt Mandy’s small house found itself all of a sudden a very popular resort. The old women held Erastus up as an example to their sons. The old men told what they might have done had they had his chance. The young men cursed him, and the young girls giggled and waited.

So there was much talk across the dirty little streets, and Aunt Mandy’s small house found itself all of a sudden a very popular resort. The old women held Erastus up as an example to their sons. The old men told what they might have done had they had his chance. The young men cursed him, and the young girls giggled and waited.

It was about an hour before the time of the arrival of Erastus, and the neighbours had thinned out one by one with a delicacy rather surprising in them, in order that the old lady might be alone with her boy for the first few minutes. Only one remained to help put the finishing touches to the two little rooms which Mrs. Smith called home, and to the preparations for the great dinner. The old woman wiped her eyes as she said to her companion, “Hit do seem a speshul blessin’, Lizy, dat I been spaihed to see dat chile once mo’ in de flesh. He sholy was mighty nigh to my hea’t, an’ w’en he went erway, I thought it ‘ud kill me. But I kin see now dat hit uz all fu’ de bes’. Think o’ ‘Rastus comin’ home, er big man! Who’d evah ‘specked dat?”

“Law, Mis’ Smif, you sholy is got reason to be mighty thankful. Des’ look how many young men dere is in dis town what ain’t nevah been no ‘count to dey pa’ents, ner anybody else.”

“Well, it’s onexpected, Lizy, an’ hit’s ‘spected. ‘Rastus allus wuz a wonnerful chil’, an’ de way he tuk to work an’ study kin’ o’ promised something f’om de commencement, an’ I ‘lowed mebbe he tu’n out a preachah.”

“Tush! yo’ kin thank yo’ stahs he didn’t tu’n out no preachah. Preachahs ain’t no bettah den anybody else dese days. Dey des go roun’ tellin’ dey lies an’ eatin’ de whiders an’ orphins out o’ house an’ home.”

“Well, mebbe hit’s bes’ he didn’ tu’n out dat way. But f’om de way he used to stan’ on de chaih an’ ‘zort w’en he was a little boy, I thought hit was des what he ‘ud tu’n out. O’ co’se, being’ in a law office is des as pervidin’, but somehow hit do seem mo’ worl’y.”

“Didn’t I tell you de preachahs is ez worldly ez anybody else?”

“Yes, yes, dat’s right, but den ‘Rastus, he had de eddication, fo’ he had gone thoo de Third Readah.”

Just then the gate creaked, and a little brown-faced girl, with large, mild eyes, pushed open the door and came shyly in.

“Hyeah’s some flowahs, Mis’ Smif,” she said. “I thought mebbe you might like to decorate ‘Rastus’s room,” and she wiped the confusion from her face with her apron.

“La, chil’, thankee. Dese is mighty pu’tty posies.” These were the laurels which Sally Martin had brought to lay at the feet of her home-coming hero. No one in Cat Alley but that queer, quiet little girl would have thought of decorating anybody’s room with flowers, but she had peculiar notions.

In the old days, when they were children, and before Erastus had gone away to become great, they had gone up and down together along the byways of their locality, and had loved as children love. Later, when Erastus began keeping company, it was upon Sally that he bestowed his affections. No one, not even her mother, knew how she had waited for him all these years that he had been gone, few in reality, but so long and so many to her.

And now he was coming home. She scorched something in the ironing that day because tears of joy were blinding her eyes. Her thoughts were busy with the meeting that was to be. She had a brand new dress for the occasion—a lawn, with dark blue dots, and a blue sash—and there was a new hat, wonderful with the flowers of summer, and for both of them she had spent her hard-earned savings, because she wished to be radiant in the eyes of the man who loved her.

Of course, Erastus had not written her; but he must have been busy, and writing was hard work. She knew that herself, and realised it all the more as she penned the loving little scrawls which at first she used to send him. Now they would not have to do any writing any more; they could say what they wanted to each other. He was coming home at last, and she had waited long.

They paint angels with shining faces and halos, but for real radiance one should have looked into the dark eyes of Sally as she sped home after her contribution to her lover’s reception.

When the last one of the neighbours had gone Aunt Mandy sat down to rest herself and to await the great event. She had not sat there long before the gate creaked. She arose and hastened to the window. A young man was coming down the path. Was that ‘Rastus? Could that be her ‘Rastus, that gorgeous creature with the shiny shoes and the nobby suit and the carelessly-swung cane? But he was knocking at her door, and she opened it and took him into her arms.

“Why, howdy, honey, howdy; hit do beat all to see you agin, a great big, grown-up man. You’re lookin’ des’ lak one o’ de big folks up in town.”

Erastus submitted to her endearments with a somewhat condescending grace, as who should say, “Well, poor old fool, let her go on this time; she doesn’t know any better.” He smiled superiorly when the old woman wept glad tears, as mothers have a way of doing over returned sons, however great fools these sons may be. She set him down to the dinner which she had prepared for him, and with loving patience drew from his pompous and reluctant lips some of the story of his doings and some little word about the places he had seen.

“Oh, yes,” he said, crossing his legs, “as soon as Mr. Carrington saw that I was pretty bright, he took me right up and gave me a good job, and I have been working for him right straight along for seven years now. Of course, it don’t do to let white folks know all you’re thinking; but I have kept my ears and my eyes right open, and I guess I know just about as much about law as he does himself. When I save up a little more I’m going to put on the finishing touches and hang out my shingle.”

“Don’t you nevah think no mo’ ’bout bein’ a preachah, ‘Rastus?” his mother asked.

“Haw, haw! Preachah? Well, I guess not; no preaching in mine; there’s nothing in it. In law you always have a chance to get into politics and be the president of your ward club or something like that, and from that on it’s an easy matter to go on up. You can trust me to know the wires.” And so the tenor of his boastful talk ran on, his mother a little bit awed and not altogether satisfied with the new ‘Rastus that had returned to her.

He did not stay in long that evening, although his mother told him some of the neighbours were going to drop in. He said he wanted to go about and see something of the town. He paused just long enough to glance at the flowers in his room, and to his mother’s remark, “Sally Ma’tin brung dem in,” he returned answer, “Who on earth is Sally Martin?”

“Why, ‘Rastus,” exclaimed his mother, “does yo’ ‘tend lak yo’ don’t ‘member little Sally Ma’tin yo’ used to go wid almos’ f’om de time you was babies? W’y, I’m s’prised at you.”

“She has slipped my mind,” said the young man.

For a long while the neighbours who had come and Aunt Mandy sat up to wait for Erastus, but he did not come in until the last one was gone. In fact, he did not get in until nearly four o’clock in the morning, looking a little weak, but at least in the best of spirits, and he vouchsafed to his waiting mother the remark that “the little old town wasn’t so bad, after all.”

Aunt Mandy preferred the request that she had had in mind for some time, that he would go to church the next day, and he consented, because his trunk had come.

It was a glorious Sunday morning, and the old lady was very proud in her stiff gingham dress as she saw her son come into the room arrayed in his long coat, shiny hat, and shinier shoes. Well, if it was true that he was changed, he was still her ‘Rastus, and a great comfort to her. There was no vanity about the old woman, but she paused before the glass a longer time than usual, settling her bonnet strings, for she must look right, she told herself, to walk to church with that elegant son of hers. When he was all ready, with cane in hand, and she was pausing with the key in the door, he said, “Just walk on, mother, I’ll catch you in a minute or two.” She went on and left him.

He did not catch her that morning on her way to church, and it was a sore disappointment, but it was somewhat compensated for when she saw him stalking into the chapel in all his glory, and every head in the house turned to behold him.

There was one other woman in “Little Africa” that morning who stopped for a longer time than usual before her looking-glass and who had never found her bonnet strings quite so refractory before. In spite of the vexation of flowers that wouldn’t settle and ribbons that wouldn’t tie, a very glad face looked back at Sally Martin from her little mirror. She was going to see ‘Rastus, ‘Rastus of the old days in which they used to walk hand in hand. He had told her when he went away that some day he would come back and marry her. Her heart fluttered hotly under her dotted lawn, and it took another application of the chamois to take the perspiration from her face. People had laughed at her, but that morning she would be vindicated. He would walk home with her before the whole church. Already she saw him bowing before her, hat in hand, and heard the set phrase, “May I have the pleasure of your company home?” and she saw herself sailing away upon his arm.

She was very happy as she sat in church that morning, as happy as Mrs. Smith herself, and as proud when she saw the object of her affections swinging up the aisle to the collection table, and from the ring she knew that it could not be less than a half dollar that he put in.

There was a special note of praise in her voice as she joined in singing the doxology that morning, and her heart kept quivering and fluttering like a frightened bird as the people gathered in groups, chattering and shaking hands, and he drew nearer to her. Now they were almost together; in a moment their eyes would meet. Her breath came quickly; he had looked at her, surely he must have seen her. His mother was just behind him, and he did not speak. Maybe she had changed, maybe he had forgotten her. An unaccustomed boldness took possession of her, and she determined that she would not be overlooked. She pressed forward. She saw his mother take his arm and heard her whisper, “Dere’s Sally Ma’tin” this time, and she knew that he looked at her. He bowed as if to a stranger, and was past her the next minute. When she saw him again he was swinging out of the door between two admiring lines of church-goers who separated on the pavement. There was a brazen yellow girl on his arm.

She felt weak and sick as she hid behind the crowd as well as she could, and for that morning she thanked God that she was small.

Aunt Mandy trudged home alone, and when the street was cleared and the sexton was about to lock up, the girl slipped out of the church and down to her own little house. In the friendly shelter of her room she took off her gay attire and laid it away, and then sat down at the window and looked dully out. For her, the light of day had gone out.

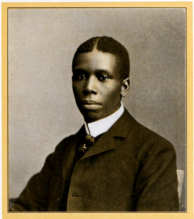

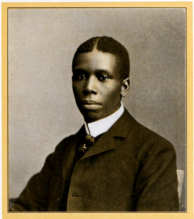

Paul Laurence Dunbar

(1872 – 1906)

The Home-Coming Of ‘Rastus Smith

From The Heart Of Happy Hollow, a collection of short stories reprinted in 1904 by Dodd, Mead and Company, New York. Short Story

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Archive C-D, Dunbar, Paul Laurence, Dunbar, Paul Laurence, Paul Laurence Dunbar, Paul Laurence Dunbar

Vaak koopt Mels een boeketje bloemen, voor op het graf van Tijger. Soms gaan er weken voorbij zonder dat hij aan hem denkt, maar er zijn dagen dat hij juist heel vaak aan hem denkt, vooral nu de gemeente bekend heeft gemaakt dat het kerkhof zal worden verplaatst.

Als hij die plek niet meer kan bezoeken, raakt hij een groot deel van zichzelf kwijt. En wie zal de graven van zijn dierbaren op het nieuwe kerkhof verzorgen? Alle graven die jonger zijn dan veertig jaar worden verplaatst naar het nieuwe kerkhof, een paar kilometer buiten het dorp, waar de nieuwe overledenen al een jaar of tien worden begraven. De overige graven zullen worden geruimd. Tijger en grootvader Bernhard zullen worden weggewist.

Als hij die plek niet meer kan bezoeken, raakt hij een groot deel van zichzelf kwijt. En wie zal de graven van zijn dierbaren op het nieuwe kerkhof verzorgen? Alle graven die jonger zijn dan veertig jaar worden verplaatst naar het nieuwe kerkhof, een paar kilometer buiten het dorp, waar de nieuwe overledenen al een jaar of tien worden begraven. De overige graven zullen worden geruimd. Tijger en grootvader Bernhard zullen worden weggewist.

Het nieuwe kerkhof is ver weg. Te ver voor een rolstoel. Hij zou moeten protesteren tegen de ruiming, maar hij beseft dat hij te weinig medestanders heeft. De mensen op het oude kerkhof zijn grotendeels vergeten. De meeste mensen in het dorp zijn nieuw. Mensen uit de stad die op het platteland willen wonen, maar door hun komst de stad naar het dorp hebben gehaald.

Hoelang zal hij zijn doden nog kunnen bezoeken?

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (092)

wordt vervolgd

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

`Ik heb het schrift van Jacob bij me’, zegt Mels. `Ik wil eruit voorlezen.’

`Dat doen we op het dak van de silo’, zegt Thija. `Kom op.’

Aan de achterkant van de fabriek lopen ze door een openstaande deur naar binnen. De fabriek zelf is klein en valt in het niet bij de silo waarin het graan wordt opgeslagen.

Aan de achterkant van de fabriek lopen ze door een openstaande deur naar binnen. De fabriek zelf is klein en valt in het niet bij de silo waarin het graan wordt opgeslagen.

Over een ijzeren trap gaan ze omhoog. Hun schoenen klepperen op de stalen roosters die de traptreden vormen.

Het gebouw is gevuld met vier kleinere, ronde silo’s, voor elke graansoort een. Het ruikt er naar de enorme berg graan die opgeslagen is. Stoffig graan, dat op hun keel werkt.

`Het is helemaal niet wit hierbinnen’, zegt Thija. `Ik dacht altijd dat het vol meel zat.’

`Na de oogst komt hier het graan binnen’, zegt Tijger. `Genoeg om de fabriek het hele jaar te laten draaien.’

Door kleine raampjes kijken ze uit over het dorp en de Wijer, die nu lang en dun is en op een slang lijkt.

Door een luik stappen ze op het dak. De wind krijgt vat op Thija’s rok en blaast hem bollend op.

`Hou je vast!’ roept Tijger. `Je vliegt weg!’

`Dat wil ik juist’, lacht Thija, maar toch houdt ze zich aan hem vast.

Ze kijken uit over het dorp. Ze horen de mensen beneden, die bonkende, kloppende en tikkende geluiden maken.

Ze gaan op hun rug op het dak liggen. Van zo hoog lijkt de hemel veel weidser.

Mels droomt, met open ogen. Met z’n drieën zitten ze in de boot op de Wijer. Ze zijn van plan naar China te gaan. Thija heeft haar reistas op schoot, met daarin een cadeautje voor de keizer. Alleen zij weet wat het is. Ze heeft er Tijger en Mels niets over gezegd. Die vragen er ook niet naar. Dat heeft geen zin, want als je haar wat vraagt, zegt ze het zeker niet.

De boot gaat maar langzaam vooruit. Het water staat laag. Mels moet flink roeien.

Eindelijk komen ze in het dorp aan. Tijd om afscheid te nemen. Er staat maar één persoon op de brug. Tijgers moeder, in een zwarte flodderjurk. Door de wind wappert haar rode haar rond haar hoofd. Mels mist zijn moeder. En waar zijn de grootvaders? Hij is teleurgesteld. Ze horen er te staan, om hen uit te wuiven. Interesseert het hen niet meer dat ze weggaan?

Mels vindt het vooral vreemd dat zijn eigen moeder hem niet uitzwaait en dat ze doodgewoon de ramen aan het lappen is. Hij hoort haar zingen. `Je bent al groter dan mijn buik voordat je werd geboren. Ik zal nog van je houden, ook al word je zo groot als de kerktoren.’ Maar als ze zo veel van hem houdt, waarom zwaait ze hem dan niet uit?

Terwijl ze onder de brug door varen, verandert de boot in een groene helikopter.

Tijger zit aan de stuurknuppel. Hij roept iets. Wat? Het lawaai van de helikopter is zo oorverdovend dat Mels hem niet verstaat. Hij ziet dat Thija tegen Tijger praat, want haar mond beweegt. Hij hoort alleen zijn moeder die zingt: `Je bent al groter dan mijn buik voordat je werd geboren.’

Dan gebeurt er iets vreemds. De helikopter verandert in een zwarte flodderjurk. Opeens zitten Mels en Thija in de donkere buik van Tijgers moeder. Tijger zit in haar glazen hoofd. Hij kijkt door haar ogen en veegt de wapperende rode haren weg die hem het uitzicht ontnemen.

`Ze vliegt ons naar de duivel!’ roept Mels.

Mels hoort dat Tijger iets terugroept, in paniek, maar zijn stem gaat verloren in het geraas. Met een enorme klap vliegen ze tegen de silo. De jurk van zwart glas laat een sneeuwbui van zwarte splinters over het dorp vallen.

`Je ligt te slapen’, zegt Thija.

`Het komt door de wind’, zegt Mels. `Ik droomde dat we naar China vertrokken, in een groene helikopter die veranderde in Tijgers moeder.’

`En toen?’

`We vlogen tegen de silo.’

`Zie je wel’, zegt Thija. `Die droom voorspelt dat onze reis nooit zal lukken. Tijger komt nooit van zijn moeder los.’

`En jij?’

`Ik?’ Thija lijkt verbaasd. `Ik ben geen moederskindje. Jij?’

`Nee’, zegt Mels, maar hij weet dat het anders is. Hij houdt ervan dat zijn moeder zingt.

Om zich niet verder te hoeven verdedigen, pakt Mels het schrift van Jacob.

`Lees jij voor?’ Hij geeft het schrift aan Thija.

Ze slaat het open, bladert het door.

`Hij schreef ook gedichten.’

Ze schraapt haar keel, zoals ook meester Hajenius altijd deed als hij begon met voorlezen.

`Ze vroegen aan mij waarom ik huilde.

Het was de wind die mij dat vroeg,

het waren de vogels die mij vroegen,

jongen, waarom ben jij zo alleen?

Ze zeggen tegen mij,

ze zeggen het niet,

maar ze zouden het willen zeggen.

Waarom is je huis zo leeg?

Waarom is je hart alleen?

Waarom ben je verlaten?

Ze zeggen het niet.

Het was de wind die mij dat vroeg,

het waren de vogels die mij dat vroegen.

Als ik gestorven ben,

zal de wind het aan jullie vragen.

Als ik gestorven ben,

zullen de vogels aan jullie vragen,

waarom ik zo alleen was.’

Ze zijn er stil van, omdat Jacob zo precies had geweten hoe het hem zou vergaan.

Ze staan op en dalen de trap af.

Beneden, in bijna lege ruimtes, draaien de machines die het lawaai veroorzaken. Het is er zo lawaaiig dat ze naar elkaar schreeuwen en elkaar toch nauwelijks kunnen verstaan. Het is niet duidelijk wat de machines doen. Er is niemand. Het is net of er niemand werkt. Het is een spookfabriek.

`Het lijkt of we in een boek van Jules Verne terecht zijn gekomen’, roept Tijger.

`We zijn op de maan’, roept Mels terug in Tijgers oor. `De machines maken lucht en water, zodat wij hier ook kunnen leven.’

`Bij die herrie kan niemand leven’, roept Thija, de handen voor de oren.

`Ik wel’, roept Tijger. `Ik hou van hard. Lawaai is mooi. Ik zou hier graag willen wonen.’

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (091)

wordt vervolgd

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

The Unrest-Cure

On the rack in the railway carriage immediately opposite Clovis was a solidly wrought travelling-bag, with a carefully written label, on which was inscribed, “J. P. Huddle, The Warren, Tilfield, near Slowborough.” Immediately below the rack sat the human embodiment of the label, a solid, sedate individual, sedately dressed, sedately conversational.

Even without his conversation (which was addressed to a friend seated by his side, and touched chiefly on such topics as the backwardness of Roman hyacinths and the prevalence of measles at the Rectory), one could have gauged fairly accurately the temperament and mental outlook of the travelling bag’s owner. But he seemed unwilling to leave anything to the imagination of a casual observer, and his talk grew presently personal and introspective.

Even without his conversation (which was addressed to a friend seated by his side, and touched chiefly on such topics as the backwardness of Roman hyacinths and the prevalence of measles at the Rectory), one could have gauged fairly accurately the temperament and mental outlook of the travelling bag’s owner. But he seemed unwilling to leave anything to the imagination of a casual observer, and his talk grew presently personal and introspective.

“I don’t know how it is,” he told his friend, “I’m not much over forty, but I seem to have settled down into a deep groove of elderly middle-age. My sister shows the same tendency. We like everything to be exactly in its accustomed place; we like things to happen exactly at their appointed times; we like everything to be usual, orderly, punctual, methodical, to a hair’s breadth, to a minute. It distresses and upsets us if it is not so. For instance, to take a very trifling matter, a thrush has built its nest year after year in the catkin-tree on the lawn; this year, for no obvious reason, it is building in the ivy on the garden wall. We have said very little about it, but I think we both feel that the change is unnecessary, and just a little irritating.”

“Perhaps,” said the friend, “it is a different thrush.”

“We have suspected that,” said J. P. Huddle, “and I think it gives us even more cause for annoyance. We don’t feel that we want a change of thrush at our time of life; and yet, as I have said, we have scarcely reached an age when these things should make themselves seriously felt.”

“What you want,” said the friend, “is an Unrest-cure.”

“An Unrest-cure? I’ve never heard of such a thing.”

“You’ve heard of Rest-cures for people who’ve broken down under stress of too much worry and strenuous living; well, you’re suffering from overmuch repose and placidity, and you need the opposite kind of treatment.”

“But where would one go for such a thing?”

“Well, you might stand as an Orange candidate for Kilkenny, or do a course of district visiting in one of the Apache quarters of Paris, or give lectures in Berlin to prove that most of Wagner’s music was written by Gambetta; and there’s always the interior of Morocco to travel in. But, to be really effective, the Unrest-cure ought to be tried in the home. How you would do it I haven’t the faintest idea.”

It was at this point in the conversation that Clovis became galvanized into alert attention. After all, his two days’ visit to an elderly relative at Slowborough did not promise much excitement. Before the train had stopped he had decorated his sinister shirt-cuff with the inscription, “J. P. Huddle, The Warren, Tilfield, near Slowborough.”

Two mornings later Mr. Huddle broke in on his sister’s privacy as she sat reading Country Life in the morning room. It was her day and hour and place for reading Country Life, and the intrusion was absolutely irregular; but he bore in his hand a telegram, and in that household telegrams were recognized as happening by the hand of God. This particular telegram partook of the nature of a thunderbolt. “Bishop examining confirmation class in neighbourhood unable stay rectory on account measles invokes your hospitality sending secretary arrange.”

“I scarcely know the Bishop; I’ve only spoken to him once,” exclaimed J. P. Huddle, with the exculpating air of one who realizes too late the indiscretion of speaking to strange Bishops. Miss Huddle was the first to rally; she disliked thunderbolts as fervently as her brother did, but the womanly instinct in her told her that thunderbolts must be fed.

“We can curry the cold duck,” she said. It was not the appointed day for curry, but the little orange envelope involved a certain departure from rule and custom. Her brother said nothing, but his eyes thanked her for being brave.

“A young gentleman to see you,” announced the parlour-maid.

“The secretary!” murmured the Huddles in unison; they instantly stiffened into a demeanour which proclaimed that, though they held all strangers to be guilty, they were willing to hear anything they might have to say in their defence. The young gentleman, who came into the room with a certain elegant haughtiness, was not at all Huddle’s idea of a bishop’s secretary; he had not supposed that the episcopal establishment could have afforded such an expensively upholstered article when there were so many other claims on its resources. The face was fleetingly familiar; if he had bestowed more attention on the fellow-traveller sitting opposite him in the railway carriage two days before he might have recognized Clovis in his present visitor.

“You are the Bishop’s secretary?” asked Huddle, becoming consciously deferential.

“His confidential secretary,” answered Clovis. “You may call me Stanislaus; my other name doesn’t matter. The Bishop and Colonel Alberti may be here to lunch. I shall be here in any case.”

It sounded rather like the programme of a Royal visit.

“The Bishop is examining a confirmation class in the neighbourhood, isn’t he?” asked Miss Huddle.

“Ostensibly,” was the dark reply, followed by a request for a large-scale map of the locality.

Clovis was still immersed in a seemingly profound study of the map when another telegram arrived. It was addressed to “Prince Stanislaus, care of Huddle, The Warren, etc.” Clovis glanced at the contents and announced: “The Bishop and Alberti won’t be here till late in the afternoon.” Then he returned to his scrutiny of the map.

The luncheon was not a very festive function. The princely secretary ate and drank with fair appetite, but severely discouraged conversation. At the finish of the meal he broke suddenly into a radiant smile, thanked his hostess for a charming repast, and kissed her hand with deferential rapture.

Miss Huddle was unable to decide in her mind whether the action savoured of Louis Quatorzian courtliness or the reprehensible Roman attitude towards the Sabine women. It was not her day for having a headache, but she felt that the circumstances excused her, and retired to her room to have as much headache as was possible before the Bishop’s arrival. Clovis, having asked the way to the nearest telegraph office, disappeared presently down the carriage drive. Mr. Huddle met him in the hall some two hours later, and asked when the Bishop would arrive.

“He is in the library with Alberti,” was the reply.

“But why wasn’t I told? I never knew he had come!” exclaimed Huddle.

“No one knows he is here,” said Clovis; “the quieter we can keep matters the better. And on no account disturb him in the library. Those are his orders.”

“But what is all this mystery about? And who is Alberti? And isn’t the Bishop going to have tea?”

“The Bishop is out for blood, not tea.”

“Blood!” gasped Huddle, who did not find that the thunderbolt improved on acquaintance.

“To-night is going to be a great night in the history of Christendom,” said Clovis. “We are going to massacre every Jew in the neighbourhood.”

“To massacre the Jews!” said Huddle indignantly. “Do you mean to tell me there’s a general rising against them?”

“No, it’s the Bishop’s own idea. He’s in there arranging all the details now.”

“But — the Bishop is such a tolerant, humane man.”

“That is precisely what will heighten the effect of his action. The sensation will be enormous.”

That at least Huddle could believe.

“He will be hanged!” he exclaimed with conviction.

“A motor is waiting to carry him to the coast, where a steam yacht is in readiness.”

“But there aren’t thirty Jews in the whole neighbourhood,” protested Huddle, whose brain, under the repeated shocks of the day, was operating with the uncertainty of a telegraph wire during earthquake disturbances.

“We have twenty-six on our list,” said Clovis, referring to a bundle of notes. “We shall be able to deal with them all the more thoroughly.”

“Do you mean to tell me that you are meditating violence against a man like Sir Leon Birberry,” stammered Huddle; “he’s one of the most respected men in the country.”

“He’s down on our list,” said Clovis carelessly; “after all, we’ve got men we can trust to do our job, so we shan’t have to rely on local assistance. And we’ve got some Boy-scouts helping us as auxiliaries.”

“Boy-scouts!”

“Yes; when they understood there was real killing to be done they were even keener than the men.”

“This thing will be a blot on the Twentieth Century!”

“And your house will be the blotting-pad. Have you realized that half the papers of Europe and the United States will publish pictures of it? By the way, I’ve sent some photographs of you and your sister, that I found in the library, to the MATIN and DIE WOCHE; I hope you don’t mind. Also a sketch of the staircase; most of the killing will probably be done on the staircase.”

The emotions that were surging in J. P. Huddle’s brain were almost too intense to be disclosed in speech, but he managed to gasp out: “There aren’t any Jews in this house.”

“Not at present,” said Clovis.

“I shall go to the police,” shouted Huddle with sudden energy.

“In the shrubbery,” said Clovis, “are posted ten men who have orders to fire on anyone who leaves the house without my signal of permission. Another armed picquet is in ambush near the front gate. The Boy-scouts watch the back premises.”

At this moment the cheerful hoot of a motor-horn was heard from the drive. Huddle rushed to the hall door with the feeling of a man half awakened from a nightmare, and beheld Sir Leon Birberry, who had driven himself over in his car. “I got your telegram,” he said, “what’s up?”

Telegram? It seemed to be a day of telegrams.

“Come here at once. Urgent. James Huddle,” was the purport of the message displayed before Huddle’s bewildered eyes.

“I see it all!” he exclaimed suddenly in a voice shaken with agitation, and with a look of agony in the direction of the shrubbery he hauled the astonished Birberry into the house. Tea had just been laid in the hall, but the now thoroughly panic-stricken Huddle dragged his protesting guest upstairs, and in a few minutes’ time the entire household had been summoned to that region of momentary safety. Clovis alone graced the tea-table with his presence; the fanatics in the library were evidently too immersed in their monstrous machinations to dally with the solace of teacup and hot toast. Once the youth rose, in answer to the summons of the front-door bell, and admitted Mr. Paul Isaacs, shoemaker and parish councillor, who had also received a pressing invitation to The Warren. With an atrocious assumption of courtesy, which a Borgia could hardly have outdone, the secretary escorted this new captive of his net to the head of the stairway, where his involuntary host awaited him.

And then ensued a long ghastly vigil of watching and waiting. Once or twice Clovis left the house to stroll across to the shrubbery, returning always to the library, for the purpose evidently of making a brief report. Once he took in the letters from the evening postman, and brought them to the top of the stairs with punctilious politeness. After his next absence he came half-way up the stairs to make an announcement.

“The Boy-scouts mistook my signal, and have killed the postman. I’ve had very little practice in this sort of thing, you see. Another time I shall do better.”

The housemaid, who was engaged to be married to the evening postman, gave way to clamorous grief.

“Remember that your mistress has a headache,” said J. P. Huddle. (Miss Huddle’s headache was worse.)

Clovis hastened downstairs, and after a short visit to the library returned with another message:

“The Bishop is sorry to hear that Miss Huddle has a headache. He is issuing orders that as far as possible no firearms shall be used near the house; any killing that is necessary on the premises will be done with cold steel. The Bishop does not see why a man should not be a gentleman as well as a Christian.”

That was the last they saw of Clovis; it was nearly seven o’clock, and his elderly relative liked him to dress for dinner. But, though he had left them for ever, the lurking suggestion of his presence haunted the lower regions of the house during the long hours of the wakeful night, and every creak of the stairway, every rustle of wind through the shrubbery, was fraught with horrible meaning. At about seven next morning the gardener’s boy and the early postman finally convinced the watchers that the Twentieth Century was still unblotted.

“I don’t suppose,” mused Clovis, as an early train bore him townwards, “that they will be in the least grateful for the Unrest-cure.”

The Unrest-Cure

From ‘The Chronicles of Clovis’

by Saki (H. H. Munro)

(1870 – 1916)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Saki, Saki, The Art of Reading

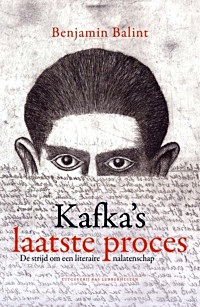

Het nagelaten werk van Franz Kafka is dankzij zijn vriend Max Brod bewaard gebleven, maar na het overlijden van Brod in 1968 begint een hevige en absurde strijd om het eigendomsrecht.

De originele, handgeschreven versies van meesterwerken als Het proces en De gedaanteverwisseling komen achtereenvolgens in handen van Brods secretaresse Esther Hoffe en haar dochter Eva.

De originele, handgeschreven versies van meesterwerken als Het proces en De gedaanteverwisseling komen achtereenvolgens in handen van Brods secretaresse Esther Hoffe en haar dochter Eva.

Er ontvouwt zich echter een juridisch getouwtrek als zowel Israël als Duitsland het werk claimen.

Duitsland, waar drie zussen van Kafka stierven tijdens de Tweede Wereldoorlog, wil de schrijver recht doen, en Israël meent rechten te hebben als Joodse staat en Kafka’s gedroomde land.

Kafka’s laatste proces leest als een waargebeurde thriller, maar maakt pijnlijk duidelijk hoe de Joodse schrijver Franz Kafka inzet wordt van zionistische claims. In de verbeten strijd die de twee landen uitvechten, lijken ze vooral de geschiedenis te willen herschrijven.

Benjamin Balint woont in Jeruzalem, waar hij verbonden is aan het Van Leer Institute. Hij schrijft o.a. voor Haaretz en de Wall Street Journal. Over de Joods-Amerikaanse schrijvers die publiceerden in het tijdschrift Commentary, schreef hij Running Commentary (2010).

Benjamin Balint (Auteur)

Kafka’s laatste proces.

De strijd om een literaire nalatenschap

Vertaling Frank Lekens

Oorspronkelijke titel:

Kafka’s Last Trial.

The Case of a Literary Legacy

Omslagtekening Jirí Slíva

Omslag Bart van den Tooren

Uitg. Bas Lubberhuizen

304 pagina’s

15 x 23 cm

Geïllustreerde paperback

ISBN 9789059375284

Verschenen: januari 2019

€ 24,99

# New books

Benjamin Balint

Kafka’s Last Trial.

The Case of a Literary Legacy

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive A-B, Archive K-L, Archive K-L, Art & Literature News, Franz Kafka, Kafka, Franz, Kafka, Franz

Een lange vrachtwagen van Bouwbedrijf Leon van Wijk en Zonen stopt bij de silo. Een kraan takelt bouwmateriaal uit de bak: planken, stalen stutbalken, steigermateriaal, een werkkeet en een bouwlift. Een ploegje arbeiders begint met het bouwen van de steigers.

Met gemengde gevoelens ziet Mels het aan. Als een moederkloek heeft het enorme gebouw altijd het dorp beheerst. Tot zomaar, van de ene op de andere dag, aan de werknemers werd verteld dat het bedrijf verkocht was en de productie werd gestaakt. Terwijl het toch volop winst maakte en er een paar maanden eerder nog een uitbreiding was aangekondigd. De fabriek was ten onder gegaan aan haar eigen succes en was opgekocht door de concurrentie om te worden uitgeschakeld.

Met gemengde gevoelens ziet Mels het aan. Als een moederkloek heeft het enorme gebouw altijd het dorp beheerst. Tot zomaar, van de ene op de andere dag, aan de werknemers werd verteld dat het bedrijf verkocht was en de productie werd gestaakt. Terwijl het toch volop winst maakte en er een paar maanden eerder nog een uitbreiding was aangekondigd. De fabriek was ten onder gegaan aan haar eigen succes en was opgekocht door de concurrentie om te worden uitgeschakeld.

De vrachtwagen van het bouwbedrijf vertrekt. De chauffeur steekt een hand op. Mels groet terug.

Even later loopt de opzichter naar het café. Hij staat stil op de brug en kijkt naar het water.

`Viswater?’

`Vroeger zat er forel in’, zegt Mels. `Als jongen heb ik er genoeg gevangen. En aal.’

`Nu niets meer?’

`Ze vangen soms baars. Een enkele snoek.’

`Kom ik zondag eens kijken. Ik gooi graag een hengeltje uit.’

Hij loopt door naar het café en komt even later naar buiten met een pakje shag.

`Wat komt er in de silo?’ vraagt Mels.

`Appartementen.’ De man rolt een sigaret. `Ze worden verkocht als exclusief.’

`Dat ding is toch niet apart?’

`Ze zeggen dat het een monument is. Een dorpsbepalend beeld. Zoiets. Hij moet blijven staan vanwege het historisch belang.’ Hij likt zijn shagje dicht. `Ze hadden er beter een bom op kunnen gooien. Hadden ze plaats gehad voor echte huizen. Mij maakt het niks uit. Wij hebben er een mooie klus aan.’

`Ik wil je wat vragen. Ik zoek iemand om een paar pannen op mijn dak te vervangen.’

`Heb je nog pannen?’

`Genoeg.’

`Ik stuur wel een mannetje. Stop hem maar wat toe. Altijd goed.’

`Dank je.’

De man loopt verder.

`Toch missen we de fabriek’, zegt Mels nog. `We waren eraan gewend. Het lawaai in de maalderij was onbeschrijflijk mooi.’

`Mooi?’

`De een vindt dit mooi, de ander dat.’

`Gelukkig dat we allemaal van andere meisjes houden,’ lacht de man, `anders bleven er veel over.’

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (090)

wordt vervolgd

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

Er is steeds minder te koop in de winkel van juffrouw Fijnhout. Er komt weinig geld binnen. En daar moet wat op gevonden worden, want ze moet ook haar medicijnen kunnen betalen. En de abonnementen op de meer dan twintig missieblaadjes.

Daar zitten ze steeds in te bladeren, op zoek naar foto’s van China. Die knippen ze uit en plakken ze in. Ze hebben al drie schriften vol met foto’s van katholieke Chinese kinderen, zodat het lijkt of bijna heel China katholiek is, maar in werkelijkheid zijn het er maar een paar duizend tussen de miljoenen. Volgens Tijger kijken de Chinezen zelf naar de katholieken zoals de mensen hier naar de Jehova’s getuigen kijken: een paar fanatieke dwepers die de bijbel naar hun hand zetten en hun kinderen nog liever dood laten gaan dan ze in te laten enten tegen pokken en kinderverlamming.

Daar zitten ze steeds in te bladeren, op zoek naar foto’s van China. Die knippen ze uit en plakken ze in. Ze hebben al drie schriften vol met foto’s van katholieke Chinese kinderen, zodat het lijkt of bijna heel China katholiek is, maar in werkelijkheid zijn het er maar een paar duizend tussen de miljoenen. Volgens Tijger kijken de Chinezen zelf naar de katholieken zoals de mensen hier naar de Jehova’s getuigen kijken: een paar fanatieke dwepers die de bijbel naar hun hand zetten en hun kinderen nog liever dood laten gaan dan ze in te laten enten tegen pokken en kinderverlamming.

Om de rekken in de winkel minder leeg te laten lijken leggen de jongens er van alles bij. Zomerappels, maar die krijgen al vlug een oud vel. Niemand koopt appels, omdat de meeste mensen zelf zomerappels in de tuin hebben. Overbodig speelgoed. Te klein geworden laarzen. Schaatsen met lint, maar wie koopt er in de zomer schaatsen? Oude jaargangen van missieblaadjes, maar iedereen wordt al onder die dingen bedolven. Soms wijst juffrouw Fijnhout iets aan in haar kast om in de rekken te zetten, een servies, kristallen glazen, een blauwe puddingvorm in de vorm van een vis, een zilveren asbak. Ze doet er glimlachend afstand van omdat ze ze toch niet meer gebruikt. Soms koopt iemand wat, niet omdat hij iets nodig heeft, maar omdat niemand wil dat juffrouw Fijnhout in armoede sterft.

In de winkel blijven vooral spullen over die wachten op volgende seizoenen, voor de herfst en de winter. Overgebleven pakjes zaaigoed voor tomaten, bonen en prei, die onder een luchtdichte glazen stolp worden bewaard en ook volgend jaar nog goed zijn.

Bij het leegruimen van een kast vindt Mels spullen die jarenlang achter andere spullen verborgen zijn gebleven. Een foto van een jongeman met de toen nog jonge juffrouw Fijnhout, een meisje nog. De jongeman heeft een arm rond haar schouder geslagen. Mels denkt dat de foto met opzet op de bovenste plank is gelegd. Achteloos legt hij hem op de hoek van de tafel. Ze ziet het direct en pakt hem op.

`Nadat die foto is gemaakt, heb ik hem nooit meer gezien.’

`Wie is het?’

`Tom, de oudste zoon van de weduwe Hubben-Houba. De broer van directeur Frits. Het was zijn laatste dag hier. Hij ging studeren, in Amerika. Een paar jaar later zou hij terugkomen, om zijn moeder op te volgen en met mij te trouwen. Ik heb nooit meer iets van hem gehoord. Zijn jongere broer Frits heeft de zaak alleen overgenomen.’

`Wist zijn moeder niet waar hij was?’

`Dat denk ik wel, maar die sprak niet met mij. De rijk geworden familie haalde haar neus op voor de dochter van een dorpssmid.’

`En andere jongens?’ vraagt Mels, de foto bekijkend waarop ze een knappe, jonge vrouw is.

`Eerst heb ik te lang gewacht. En daarna was ik te zeer teleurgesteld. En later vond ik het wel goed zoals het ging. Van mijn winkel kon ik bestaan.’

Mels ruimt alles weer op. Hij legt de foto’s op een schapje waar juffrouw Fijnhout ze kan pakken zonder op te staan.

Tijgers moeder komt Mels aflossen, want juffrouw Fijnhout mag niet meer alleen zijn. Om de beurt blijven de vrouwen uit de buurt ‘s nachts bij haar.

Mels gaat naar huis.

Ze hebben bezoek. De moeder van Jacob zit in de kamer. Ze drinken thee.

`Ik heb wat voor je meegebracht’, zegt Jacobs moeder. Uit haar tas haalt ze het schrift. `Jacob wilde dat ik de verhalen die hij heeft opgeschreven aan jou gaf.’

`Wilt u ze zelf niet houden?’

`Ik kan niet lezen. Jacob heeft vier jaar in een sanatorium gelegen. Daar heeft hij leren lezen en schrijven.’

`En vioolspelen?’

`Wij maken allemaal muziek. Dat is hem met de paplepel ingegoten.’

`Dank u voor het schrift’, zegt Mels. `Jammer dat ik Jacob maar zo kort heb gekend.’

`Lang genoeg om vrienden te worden.’ Jacobs moeder staat op. Mels’ moeder brengt haar naar de deur.

`U komt nog maar eens aan’, zegt moeder.

`Wij gaan hier weg’, zegt Jacobs moeder. `Wij hebben hier weinig geluk gevonden. Misschien gaat het ons ergens anders beter.’

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (089)

wordt vervolgd

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

THE LYNCHING OF JUBE BENSON

Gordon Fairfax’s library held but three men, but the air was dense with clouds of smoke. The talk had drifted from one topic to another much as the smoke wreaths had puffed, floated, and thinned away. Then Handon Gay, who was an ambitious young reporter, spoke of a lynching story in a recent magazine, and the matter of punishment without trial put new life into the conversation.

“I should like to see a real lynching,” said Gay rather callously.

“I should like to see a real lynching,” said Gay rather callously.

“Well, I should hardly express it that way,” said Fairfax, “but if a real, live lynching were to come my way, I should not avoid it.”

“I should,” spoke the other from the depths of his chair, where he had been puffing in moody silence. Judged by his hair, which was freely sprinkled with gray, the speaker might have been a man of forty-five or fifty, but his face, though lined and serious, was youthful, the face of a man hardly past thirty.

“What, you, Dr. Melville? Why, I thought that you physicians wouldn’t weaken at anything.”

“I have seen one such affair,” said the doctor gravely, “in fact, I took a prominent part in it.”

“Tell us about it,” said the reporter, feeling for his pencil and notebook, which he was, nevertheless, careful to hide from the speaker.

The men drew their chairs eagerly up to the doctor’s, but for a minute he did not seem to see them, but sat gazing abstractedly into the fire, then he took a long draw upon his cigar and began:

“I can see it all very vividly now. It was in the summer time and about seven years ago. I was practising at the time down in the little town of Bradford. It was a small and primitive place, just the location for an impecunious medical man, recently out of college.

“In lieu of a regular office, I attended to business in the first of two rooms which I rented from Hiram Daly, one of the more prosperous of the townsmen. Here I boarded and here also came my patients—white and black—whites from every section, and blacks from ‘nigger town,’ as the west portion of the place was called.

“The people about me were most of them coarse and rough, but they were simple and generous, and as time passed on I had about abandoned my intention of seeking distinction in wider fields and determined to settle into the place of a modest country doctor. This was rather a strange conclusion for a young man to arrive at, and I will not deny that the presence in the house of my host’s beautiful young daughter, Annie, had something to do with my decision. She was a beautiful young girl of seventeen or eighteen, and very far superior to her surroundings. She had a native grace and a pleasing way about her that made everybody that came under her spell her abject slave. White and black who knew her loved her, and none, I thought, more deeply and respectfully than Jube Benson, the black man of all work about the place.

“He was a fellow whom everybody trusted; an apparently steady-going, grinning sort, as we used to call him. Well, he was completely under Miss Annie’s thumb, and would fetch and carry for her like a faithful dog. As soon as he saw that I began to care for Annie, and anybody could see that, he transferred some of his allegiance to me and became my faithful servitor also. Never did a man have a more devoted adherent in his wooing than did I, and many a one of Annie’s tasks which he volunteered to do gave her an extra hour with me. You can imagine that I liked the boy and you need not wonder any more that as both wooing and my practice waxed apace, I was content to give up my great ambitions and stay just where I was.

“It wasn’t a very pleasant thing, then, to have an epidemic of typhoid break out in the town that kept me going so that I hardly had time for the courting that a fellow wants to carry on with his sweetheart while he is still young enough to call her his girl. I fumed, but duty was duty, and I kept to my work night and day. It was now that Jube proved how invaluable he was as a coadjutor. He not only took messages to Annie, but brought sometimes little ones from her to me, and he would tell me little secret things that he had overheard her say that made me throb with joy and swear at him for repeating his mistress’ conversation. But best of all, Jube was a perfect Cerberus, and no one on earth could have been more effective in keeping away or deluding the other young fellows who visited the Dalys. He would tell me of it afterwards, chuckling softly to himself. ‘An,’ Doctah, I say to Mistah Hemp Stevens, “‘Scuse us, Mistah Stevens, but Miss Annie, she des gone out,” an’ den he go outer de gate lookin’ moughty lonesome. When Sam Elkins come, I say, “Sh, Mistah Elkins, Miss Annie, she done tuk down,” an’ he say, “What, Jube, you don’ reckon hit de——” Den he stop an’ look skeert, an’ I say, “I feared hit is, Mistah Elkins,” an’ sheks my haid ez solemn. He goes outer de gate lookin’ lak his bes’ frien’ done daid, an’ all de time Miss Annie behine de cu’tain ovah de po’ch des’ a laffin’ fit to kill.’

“Jube was a most admirable liar, but what could I do? He knew that I was a young fool of a hypocrite, and when I would rebuke him for these deceptions, he would give way and roll on the floor in an excess of delighted laughter until from very contagion I had to join him—and, well, there was no need of my preaching when there had been no beginning to his repentance and when there must ensue a continuance of his wrong-doing.

“This thing went on for over three months, and then, pouf! I was down like a shot. My patients were nearly all up, but the reaction from overwork made me an easy victim of the lurking germs. Then Jube loomed up as a nurse. He put everyone else aside, and with the doctor, a friend of mine from a neighbouring town, took entire charge of me. Even Annie herself was put aside, and I was cared for as tenderly as a baby. Tom, that was my physician and friend, told me all about it afterward with tears in his eyes. Only he was a big, blunt man and his expressions did not convey all that he meant. He told me how my nigger had nursed me as if I were a sick kitten and he my mother. Of how fiercely he guarded his right to be the sole one to ‘do’ for me, as he called it, and how, when the crisis came, he hovered, weeping, but hopeful, at my bedside, until it was safely passed, when they drove him, weak and exhausted, from the room. As for me, I knew little about it at the time, and cared less. I was too busy in my fight with death. To my chimerical vision there was only a black but gentle demon that came and went, alternating with a white fairy, who would insist on coming in on her head, growing larger and larger and then dissolving. But the pathos and devotion in the story lost nothing in my blunt friend’s telling.

“It was during the period of a long convalescence, however, that I came to know my humble ally as he really was, devoted to the point of abjectness. There were times when for very shame at his goodness to me, I would beg him to go away, to do something else. He would go, but before I had time to realise that I was not being ministered to, he would be back at my side, grinning and pottering just the same. He manufactured duties for the joy of performing them. He pretended to see desires in me that I never had, because he liked to pander to them, and when I became entirely exasperated, and ripped out a good round oath, he chuckled with the remark, ‘Dah, now, you sholy is gittin’ well. Nevah did hyeah a man anywhaih nigh Jo’dan’s sho’ cuss lak dat.’

“Why, I grew to love him, love him, oh, yes, I loved him as well—oh, what am I saying? All human love and gratitude are damned poor things; excuse me, gentlemen, this isn’t a pleasant story. The truth is usually a nasty thing to stand.

“It was not six months after that that my friendship to Jube, which he had been at such great pains to win, was put to too severe a test.

“It was in the summer time again, and as business was slack, I had ridden over to see my friend, Dr. Tom. I had spent a good part of the day there, and it was past four o’clock when I rode leisurely into Bradford. I was in a particularly joyous mood and no premonition of the impending catastrophe oppressed me. No sense of sorrow, present or to come, forced itself upon me, even when I saw men hurrying through the almost deserted streets. When I got within sight of my home and saw a crowd surrounding it, I was only interested sufficiently to spur my horse into a jog trot, which brought me up to the throng, when something in the sullen, settled horror in the men’s faces gave me a sudden, sick thrill. They whispered a word to me, and without a thought, save for Annie, the girl who had been so surely growing into my heart, I leaped from the saddle and tore my way through the people to the house.

“It was Annie, poor girl, bruised and bleeding, her face and dress torn from struggling. They were gathered round her with white faces, and, oh, with what terrible patience they were trying to gain from her fluttering lips the name of her murderer. They made way for me and I knelt at her side. She was beyond my skill, and my will merged with theirs. One thought was in our minds.

“‘Who?’ I asked.

“Her eyes half opened, ‘That black——’ She fell back into my arms dead.

“We turned and looked at each other. The mother had broken down and was weeping, but the face of the father was like iron.

“‘It is enough,’ he said; ‘Jube has disappeared.’ He went to the door and said to the expectant crowd, ‘She is dead.’

“I heard the angry roar without swelling up like the noise of a flood, and then I heard the sudden movement of many feet as the men separated into searching parties, and laying the dead girl back upon her couch, I took my rifle and went out to join them.

“As if by intuition the knowledge had passed among the men that Jube Benson had disappeared, and he, by common consent, was to be the object of our search. Fully a dozen of the citizens had seen him hastening toward the woods and noted his skulking air, but as he had grinned in his old good-natured way they had, at the time, thought nothing of it. Now, however, the diabolical reason of his slyness was apparent. He had been shrewd enough to disarm suspicion, and by now was far away. Even Mrs. Daly, who was visiting with a neighbour, had seen him stepping out by a back way, and had said with a laugh, ‘I reckon that black rascal’s a-running off somewhere.’ Oh, if she had only known.

“‘To the woods! To the woods!’ that was the cry, and away we went, each with the determination not to shoot, but to bring the culprit alive into town, and then to deal with him as his crime deserved.

“I cannot describe the feelings I experienced as I went out that night to beat the woods for this human tiger. My heart smouldered within me like a coal, and I went forward under the impulse of a will that was half my own, half some more malignant power’s. My throat throbbed drily, but water nor whiskey would not have quenched my thirst. The thought has come to me since that now I could interpret the panther’s desire for blood and sympathise with it, but then I thought nothing. I simply went forward, and watched, watched with burning eyes for a familiar form that I had looked for as often before with such different emotions.

“Luck or ill-luck, which you will, was with our party, and just as dawn was graying the sky, we came upon our quarry crouched in the corner of a fence. It was only half light, and we might have passed, but my eyes had caught sight of him, and I raised the cry. We levelled our guns and he rose and came toward us.

“‘I t’ought you wa’n’t gwine see me,’ he said sullenly, ‘I didn’t mean no harm.’

“‘Harm!’

“Some of the men took the word up with oaths, others were ominously silent.

“We gathered around him like hungry beasts, and I began to see terror dawning in his eyes. He turned to me, ‘I’s moughty glad you’s hyeah, doc,’ he said, ‘you ain’t gwine let ’em whup me.’

“‘Whip you, you hound,’ I said, ‘I’m going to see you hanged,’ and in the excess of my passion I struck him full on the mouth. He made a motion as if to resent the blow against even such great odds, but controlled himself.

“‘W’y, doctah,’ he exclaimed in the saddest voice I have ever heard, ‘w’y, doctah! I ain’t stole nuffin’ o’ yo’n, an’ I was comin’ back. I only run off to see my gal, Lucy, ovah to de Centah.’

“‘You lie!’ I said, and my hands were busy helping the others bind him upon a horse. Why did I do it? I don’t know. A false education, I reckon, one false from the beginning. I saw his black face glooming there in the half light, and I could only think of him as a monster. It’s tradition. At first I was told that the black man would catch me, and when I got over that, they taught me that the devil was black, and when I had recovered from the sickness of that belief, here were Jube and his fellows with faces of menacing blackness. There was only one conclusion: This black man stood for all the powers of evil, the result of whose machinations had been gathering in my mind from childhood up. But this has nothing to do with what happened.

“After firing a few shots to announce our capture, we rode back into town with Jube. The ingathering parties from all directions met us as we made our way up to the house. All was very quiet and orderly. There was no doubt that it was as the papers would have said, a gathering of the best citizens. It was a gathering of stern, determined men, bent on a terrible vengeance.

“We took Jube into the house, into the room where the corpse lay. At sight of it, he gave a scream like an animal’s and his face went the colour of storm-blown water. This was enough to condemn him. We divined, rather than heard, his cry of ‘Miss Ann, Miss Ann, oh, my God, doc, you don’t t’ink I done it?’

“Hungry hands were ready. We hurried him out into the yard. A rope was ready. A tree was at hand. Well, that part was the least of it, save that Hiram Daly stepped aside to let me be the first to pull upon the rope. It was lax at first. Then it tightened, and I felt the quivering soft weight resist my muscles. Other hands joined, and Jube swung off his feet.

“No one was masked. We knew each other. Not even the Culprit’s face was covered, and the last I remember of him as he went into the air was a look of sad reproach that will remain with me until I meet him face to face again.

“We were tying the end of the rope to a tree, where the dead man might hang as a warning to his fellows, when a terrible cry chilled us to the marrow.

“‘Cut ‘im down, cut ‘im down, he ain’t guilty. We got de one. Cut him down, fu’ Gawd’s sake. Here’s de man, we foun’ him hidin’ in de barn!’

“Jube’s brother, Ben, and another Negro, came rushing toward us, half dragging, half carrying a miserable-looking wretch between them. Someone cut the rope and Jube dropped lifeless to the ground.

“‘Oh, my Gawd, he’s daid, he’s daid!’ wailed the brother, but with blazing eyes he brought his captive into the centre of the group, and we saw in the full light the scratched face of Tom Skinner—the worst white ruffian in the town—but the face we saw was not as we were accustomed to see it, merely smeared with dirt. It was blackened to imitate a Negro’s.

“God forgive me; I could not wait to try to resuscitate Jube. I knew he was already past help, so I rushed into the house and to the dead girl’s side. In the excitement they had not yet washed or laid her out. Carefully, carefully, I searched underneath her broken finger nails. There was skin there. I took it out, the little curled pieces, and went with it to my office.

“There, determinedly, I examined it under a powerful glass, and read my own doom. It was the skin of a white man, and in it were embedded strands of short, brown hair or beard.

“How I went out to tell the waiting crowd I do not know, for something kept crying in my ears, ‘Blood guilty! Blood guilty!’

“The men went away stricken into silence and awe. The new prisoner attempted neither denial nor plea. When they were gone I would have helped Ben carry his brother in, but he waved me away fiercely, ‘You he’ped murder my brothah, you dat was his frien’, go ‘way, go ‘way! I’ll tek him home myse’f’ I could only respect his wish, and he and his comrade took up the dead man and between them bore him up the street on which the sun was now shining full.

“I saw the few men who had not skulked indoors uncover as they passed, and I—I—stood there between the two murdered ones, while all the while something in my ears kept crying, ‘Blood guilty! Blood guilty!'”

The doctor’s head dropped into his hands and he sat for some time in silence, which was broken by neither of the men, then he rose, saying, “Gentlemen, that was my last lynching.”

Paul Laurence Dunbar

(1872 – 1906)

The Lynching Of Jube Benson

From The Heart Of Happy Hollow, a collection of short stories reprinted in 1904 by Dodd, Mead and Company, New York.

Short Story

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Archive C-D, Dunbar, Paul Laurence, Dunbar, Paul Laurence, Paul Laurence Dunbar, Paul Laurence Dunbar

Het was Frans-Joseph die de nieuwe tijd naar het dorp had gehaald, toen hij het gezellenhuis had laten bouwen. Jonggezellen op kamertjes hadden meisjes nodig. Een van de kasteleins was op die behoefte ingesprongen, had rode lampen voor het raam gezet en meisjes uit de stad laten komen.

Frans-Joseph dacht als een grootindustrieel. Hij was ook de man die het grote flatgebouw had laten bouwen, net niet zo hoog als de silo. Zestig woningen in vier lagen, niet ver van de fabriek. Flats voor buitenlandse gezinnen met veel kinderen die later, naar hij dacht, vanzelf in de fabriek zouden gaan werken. Maar daar had hij zich in misrekend. Met de fabriek liep het mis toen de kinderen groot waren. Bovendien wilden de zonen van de gastarbeiders geen werkezels zijn zoals hun vaders.

Frans-Joseph dacht als een grootindustrieel. Hij was ook de man die het grote flatgebouw had laten bouwen, net niet zo hoog als de silo. Zestig woningen in vier lagen, niet ver van de fabriek. Flats voor buitenlandse gezinnen met veel kinderen die later, naar hij dacht, vanzelf in de fabriek zouden gaan werken. Maar daar had hij zich in misrekend. Met de fabriek liep het mis toen de kinderen groot waren. Bovendien wilden de zonen van de gastarbeiders geen werkezels zijn zoals hun vaders.

Mels rommelt wat in de paperassen. Vraagt zich af of hij al de kladjes en volgeschreven vellen toch nog kan ordenen tot een boek. Een exemplaar voor zichzelf. Na zijn dood kan dat naar het archief van de gemeente.

Hij heeft moeite om het verhaal rond te maken. Hij zit met te veel losse stukjes. Van de arbeidersfamilies die in de jaren zeventig naar het dorp kwamen, weet hij maar weinig. In de flats is hij nooit geweest.

Vanaf de dag dat de fabriek gesloten is en de arbeiders uit de uitgewoonde flatwoningen zijn vertrokken, op zoek naar werk elders of door verhuizing naar de nieuwe wijken in het dorp, staat de flat erbij als een blind bakbeest. Kapotgegooide ruiten. Uitgebroken sponningen. Graffiti, waaruit nog steeds de haat van de nieuwkomers tegen de oorspronkelijke dorpsbevolking af te lezen is. En omgekeerd. Het heeft nooit geboterd tussen de flatbewoners en de dorpelingen.