Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

The Unrest-Cure

On the rack in the railway carriage immediately opposite Clovis was a solidly wrought travelling-bag, with a carefully written label, on which was inscribed, “J. P. Huddle, The Warren, Tilfield, near Slowborough.” Immediately below the rack sat the human embodiment of the label, a solid, sedate individual, sedately dressed, sedately conversational.

Even without his conversation (which was addressed to a friend seated by his side, and touched chiefly on such topics as the backwardness of Roman hyacinths and the prevalence of measles at the Rectory), one could have gauged fairly accurately the temperament and mental outlook of the travelling bag’s owner. But he seemed unwilling to leave anything to the imagination of a casual observer, and his talk grew presently personal and introspective.

Even without his conversation (which was addressed to a friend seated by his side, and touched chiefly on such topics as the backwardness of Roman hyacinths and the prevalence of measles at the Rectory), one could have gauged fairly accurately the temperament and mental outlook of the travelling bag’s owner. But he seemed unwilling to leave anything to the imagination of a casual observer, and his talk grew presently personal and introspective.

“I don’t know how it is,” he told his friend, “I’m not much over forty, but I seem to have settled down into a deep groove of elderly middle-age. My sister shows the same tendency. We like everything to be exactly in its accustomed place; we like things to happen exactly at their appointed times; we like everything to be usual, orderly, punctual, methodical, to a hair’s breadth, to a minute. It distresses and upsets us if it is not so. For instance, to take a very trifling matter, a thrush has built its nest year after year in the catkin-tree on the lawn; this year, for no obvious reason, it is building in the ivy on the garden wall. We have said very little about it, but I think we both feel that the change is unnecessary, and just a little irritating.”

“Perhaps,” said the friend, “it is a different thrush.”

“We have suspected that,” said J. P. Huddle, “and I think it gives us even more cause for annoyance. We don’t feel that we want a change of thrush at our time of life; and yet, as I have said, we have scarcely reached an age when these things should make themselves seriously felt.”

“What you want,” said the friend, “is an Unrest-cure.”

“An Unrest-cure? I’ve never heard of such a thing.”

“You’ve heard of Rest-cures for people who’ve broken down under stress of too much worry and strenuous living; well, you’re suffering from overmuch repose and placidity, and you need the opposite kind of treatment.”

“But where would one go for such a thing?”

“Well, you might stand as an Orange candidate for Kilkenny, or do a course of district visiting in one of the Apache quarters of Paris, or give lectures in Berlin to prove that most of Wagner’s music was written by Gambetta; and there’s always the interior of Morocco to travel in. But, to be really effective, the Unrest-cure ought to be tried in the home. How you would do it I haven’t the faintest idea.”

It was at this point in the conversation that Clovis became galvanized into alert attention. After all, his two days’ visit to an elderly relative at Slowborough did not promise much excitement. Before the train had stopped he had decorated his sinister shirt-cuff with the inscription, “J. P. Huddle, The Warren, Tilfield, near Slowborough.”

Two mornings later Mr. Huddle broke in on his sister’s privacy as she sat reading Country Life in the morning room. It was her day and hour and place for reading Country Life, and the intrusion was absolutely irregular; but he bore in his hand a telegram, and in that household telegrams were recognized as happening by the hand of God. This particular telegram partook of the nature of a thunderbolt. “Bishop examining confirmation class in neighbourhood unable stay rectory on account measles invokes your hospitality sending secretary arrange.”

“I scarcely know the Bishop; I’ve only spoken to him once,” exclaimed J. P. Huddle, with the exculpating air of one who realizes too late the indiscretion of speaking to strange Bishops. Miss Huddle was the first to rally; she disliked thunderbolts as fervently as her brother did, but the womanly instinct in her told her that thunderbolts must be fed.

“We can curry the cold duck,” she said. It was not the appointed day for curry, but the little orange envelope involved a certain departure from rule and custom. Her brother said nothing, but his eyes thanked her for being brave.

“A young gentleman to see you,” announced the parlour-maid.

“The secretary!” murmured the Huddles in unison; they instantly stiffened into a demeanour which proclaimed that, though they held all strangers to be guilty, they were willing to hear anything they might have to say in their defence. The young gentleman, who came into the room with a certain elegant haughtiness, was not at all Huddle’s idea of a bishop’s secretary; he had not supposed that the episcopal establishment could have afforded such an expensively upholstered article when there were so many other claims on its resources. The face was fleetingly familiar; if he had bestowed more attention on the fellow-traveller sitting opposite him in the railway carriage two days before he might have recognized Clovis in his present visitor.

“You are the Bishop’s secretary?” asked Huddle, becoming consciously deferential.

“His confidential secretary,” answered Clovis. “You may call me Stanislaus; my other name doesn’t matter. The Bishop and Colonel Alberti may be here to lunch. I shall be here in any case.”

It sounded rather like the programme of a Royal visit.

“The Bishop is examining a confirmation class in the neighbourhood, isn’t he?” asked Miss Huddle.

“Ostensibly,” was the dark reply, followed by a request for a large-scale map of the locality.

Clovis was still immersed in a seemingly profound study of the map when another telegram arrived. It was addressed to “Prince Stanislaus, care of Huddle, The Warren, etc.” Clovis glanced at the contents and announced: “The Bishop and Alberti won’t be here till late in the afternoon.” Then he returned to his scrutiny of the map.

The luncheon was not a very festive function. The princely secretary ate and drank with fair appetite, but severely discouraged conversation. At the finish of the meal he broke suddenly into a radiant smile, thanked his hostess for a charming repast, and kissed her hand with deferential rapture.

Miss Huddle was unable to decide in her mind whether the action savoured of Louis Quatorzian courtliness or the reprehensible Roman attitude towards the Sabine women. It was not her day for having a headache, but she felt that the circumstances excused her, and retired to her room to have as much headache as was possible before the Bishop’s arrival. Clovis, having asked the way to the nearest telegraph office, disappeared presently down the carriage drive. Mr. Huddle met him in the hall some two hours later, and asked when the Bishop would arrive.

“He is in the library with Alberti,” was the reply.

“But why wasn’t I told? I never knew he had come!” exclaimed Huddle.

“No one knows he is here,” said Clovis; “the quieter we can keep matters the better. And on no account disturb him in the library. Those are his orders.”

“But what is all this mystery about? And who is Alberti? And isn’t the Bishop going to have tea?”

“The Bishop is out for blood, not tea.”

“Blood!” gasped Huddle, who did not find that the thunderbolt improved on acquaintance.

“To-night is going to be a great night in the history of Christendom,” said Clovis. “We are going to massacre every Jew in the neighbourhood.”

“To massacre the Jews!” said Huddle indignantly. “Do you mean to tell me there’s a general rising against them?”

“No, it’s the Bishop’s own idea. He’s in there arranging all the details now.”

“But — the Bishop is such a tolerant, humane man.”

“That is precisely what will heighten the effect of his action. The sensation will be enormous.”

That at least Huddle could believe.

“He will be hanged!” he exclaimed with conviction.

“A motor is waiting to carry him to the coast, where a steam yacht is in readiness.”

“But there aren’t thirty Jews in the whole neighbourhood,” protested Huddle, whose brain, under the repeated shocks of the day, was operating with the uncertainty of a telegraph wire during earthquake disturbances.

“We have twenty-six on our list,” said Clovis, referring to a bundle of notes. “We shall be able to deal with them all the more thoroughly.”

“Do you mean to tell me that you are meditating violence against a man like Sir Leon Birberry,” stammered Huddle; “he’s one of the most respected men in the country.”

“He’s down on our list,” said Clovis carelessly; “after all, we’ve got men we can trust to do our job, so we shan’t have to rely on local assistance. And we’ve got some Boy-scouts helping us as auxiliaries.”

“Boy-scouts!”

“Yes; when they understood there was real killing to be done they were even keener than the men.”

“This thing will be a blot on the Twentieth Century!”

“And your house will be the blotting-pad. Have you realized that half the papers of Europe and the United States will publish pictures of it? By the way, I’ve sent some photographs of you and your sister, that I found in the library, to the MATIN and DIE WOCHE; I hope you don’t mind. Also a sketch of the staircase; most of the killing will probably be done on the staircase.”

The emotions that were surging in J. P. Huddle’s brain were almost too intense to be disclosed in speech, but he managed to gasp out: “There aren’t any Jews in this house.”

“Not at present,” said Clovis.

“I shall go to the police,” shouted Huddle with sudden energy.

“In the shrubbery,” said Clovis, “are posted ten men who have orders to fire on anyone who leaves the house without my signal of permission. Another armed picquet is in ambush near the front gate. The Boy-scouts watch the back premises.”

At this moment the cheerful hoot of a motor-horn was heard from the drive. Huddle rushed to the hall door with the feeling of a man half awakened from a nightmare, and beheld Sir Leon Birberry, who had driven himself over in his car. “I got your telegram,” he said, “what’s up?”

Telegram? It seemed to be a day of telegrams.

“Come here at once. Urgent. James Huddle,” was the purport of the message displayed before Huddle’s bewildered eyes.

“I see it all!” he exclaimed suddenly in a voice shaken with agitation, and with a look of agony in the direction of the shrubbery he hauled the astonished Birberry into the house. Tea had just been laid in the hall, but the now thoroughly panic-stricken Huddle dragged his protesting guest upstairs, and in a few minutes’ time the entire household had been summoned to that region of momentary safety. Clovis alone graced the tea-table with his presence; the fanatics in the library were evidently too immersed in their monstrous machinations to dally with the solace of teacup and hot toast. Once the youth rose, in answer to the summons of the front-door bell, and admitted Mr. Paul Isaacs, shoemaker and parish councillor, who had also received a pressing invitation to The Warren. With an atrocious assumption of courtesy, which a Borgia could hardly have outdone, the secretary escorted this new captive of his net to the head of the stairway, where his involuntary host awaited him.

And then ensued a long ghastly vigil of watching and waiting. Once or twice Clovis left the house to stroll across to the shrubbery, returning always to the library, for the purpose evidently of making a brief report. Once he took in the letters from the evening postman, and brought them to the top of the stairs with punctilious politeness. After his next absence he came half-way up the stairs to make an announcement.

“The Boy-scouts mistook my signal, and have killed the postman. I’ve had very little practice in this sort of thing, you see. Another time I shall do better.”

The housemaid, who was engaged to be married to the evening postman, gave way to clamorous grief.

“Remember that your mistress has a headache,” said J. P. Huddle. (Miss Huddle’s headache was worse.)

Clovis hastened downstairs, and after a short visit to the library returned with another message:

“The Bishop is sorry to hear that Miss Huddle has a headache. He is issuing orders that as far as possible no firearms shall be used near the house; any killing that is necessary on the premises will be done with cold steel. The Bishop does not see why a man should not be a gentleman as well as a Christian.”

That was the last they saw of Clovis; it was nearly seven o’clock, and his elderly relative liked him to dress for dinner. But, though he had left them for ever, the lurking suggestion of his presence haunted the lower regions of the house during the long hours of the wakeful night, and every creak of the stairway, every rustle of wind through the shrubbery, was fraught with horrible meaning. At about seven next morning the gardener’s boy and the early postman finally convinced the watchers that the Twentieth Century was still unblotted.

“I don’t suppose,” mused Clovis, as an early train bore him townwards, “that they will be in the least grateful for the Unrest-cure.”

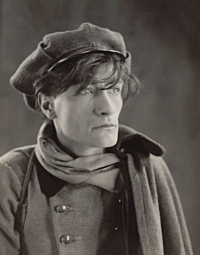

The Unrest-Cure

From ‘The Chronicles of Clovis’

by Saki (H. H. Munro)

(1870 – 1916)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Saki, Saki, The Art of Reading

Het nagelaten werk van Franz Kafka is dankzij zijn vriend Max Brod bewaard gebleven, maar na het overlijden van Brod in 1968 begint een hevige en absurde strijd om het eigendomsrecht.

De originele, handgeschreven versies van meesterwerken als Het proces en De gedaanteverwisseling komen achtereenvolgens in handen van Brods secretaresse Esther Hoffe en haar dochter Eva.

De originele, handgeschreven versies van meesterwerken als Het proces en De gedaanteverwisseling komen achtereenvolgens in handen van Brods secretaresse Esther Hoffe en haar dochter Eva.

Er ontvouwt zich echter een juridisch getouwtrek als zowel Israël als Duitsland het werk claimen.

Duitsland, waar drie zussen van Kafka stierven tijdens de Tweede Wereldoorlog, wil de schrijver recht doen, en Israël meent rechten te hebben als Joodse staat en Kafka’s gedroomde land.

Kafka’s laatste proces leest als een waargebeurde thriller, maar maakt pijnlijk duidelijk hoe de Joodse schrijver Franz Kafka inzet wordt van zionistische claims. In de verbeten strijd die de twee landen uitvechten, lijken ze vooral de geschiedenis te willen herschrijven.

Benjamin Balint woont in Jeruzalem, waar hij verbonden is aan het Van Leer Institute. Hij schrijft o.a. voor Haaretz en de Wall Street Journal. Over de Joods-Amerikaanse schrijvers die publiceerden in het tijdschrift Commentary, schreef hij Running Commentary (2010).

Benjamin Balint (Auteur)

Kafka’s laatste proces.

De strijd om een literaire nalatenschap

Vertaling Frank Lekens

Oorspronkelijke titel:

Kafka’s Last Trial.

The Case of a Literary Legacy

Omslagtekening Jirí Slíva

Omslag Bart van den Tooren

Uitg. Bas Lubberhuizen

304 pagina’s

15 x 23 cm

Geïllustreerde paperback

ISBN 9789059375284

Verschenen: januari 2019

€ 24,99

# New books

Benjamin Balint

Kafka’s Last Trial.

The Case of a Literary Legacy

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive A-B, Archive K-L, Archive K-L, Art & Literature News, Franz Kafka, Kafka, Franz, Kafka, Franz

Een lange vrachtwagen van Bouwbedrijf Leon van Wijk en Zonen stopt bij de silo. Een kraan takelt bouwmateriaal uit de bak: planken, stalen stutbalken, steigermateriaal, een werkkeet en een bouwlift. Een ploegje arbeiders begint met het bouwen van de steigers.

Met gemengde gevoelens ziet Mels het aan. Als een moederkloek heeft het enorme gebouw altijd het dorp beheerst. Tot zomaar, van de ene op de andere dag, aan de werknemers werd verteld dat het bedrijf verkocht was en de productie werd gestaakt. Terwijl het toch volop winst maakte en er een paar maanden eerder nog een uitbreiding was aangekondigd. De fabriek was ten onder gegaan aan haar eigen succes en was opgekocht door de concurrentie om te worden uitgeschakeld.

Met gemengde gevoelens ziet Mels het aan. Als een moederkloek heeft het enorme gebouw altijd het dorp beheerst. Tot zomaar, van de ene op de andere dag, aan de werknemers werd verteld dat het bedrijf verkocht was en de productie werd gestaakt. Terwijl het toch volop winst maakte en er een paar maanden eerder nog een uitbreiding was aangekondigd. De fabriek was ten onder gegaan aan haar eigen succes en was opgekocht door de concurrentie om te worden uitgeschakeld.

De vrachtwagen van het bouwbedrijf vertrekt. De chauffeur steekt een hand op. Mels groet terug.

Even later loopt de opzichter naar het café. Hij staat stil op de brug en kijkt naar het water.

`Viswater?’

`Vroeger zat er forel in’, zegt Mels. `Als jongen heb ik er genoeg gevangen. En aal.’

`Nu niets meer?’

`Ze vangen soms baars. Een enkele snoek.’

`Kom ik zondag eens kijken. Ik gooi graag een hengeltje uit.’

Hij loopt door naar het café en komt even later naar buiten met een pakje shag.

`Wat komt er in de silo?’ vraagt Mels.

`Appartementen.’ De man rolt een sigaret. `Ze worden verkocht als exclusief.’

`Dat ding is toch niet apart?’

`Ze zeggen dat het een monument is. Een dorpsbepalend beeld. Zoiets. Hij moet blijven staan vanwege het historisch belang.’ Hij likt zijn shagje dicht. `Ze hadden er beter een bom op kunnen gooien. Hadden ze plaats gehad voor echte huizen. Mij maakt het niks uit. Wij hebben er een mooie klus aan.’

`Ik wil je wat vragen. Ik zoek iemand om een paar pannen op mijn dak te vervangen.’

`Heb je nog pannen?’

`Genoeg.’

`Ik stuur wel een mannetje. Stop hem maar wat toe. Altijd goed.’

`Dank je.’

De man loopt verder.

`Toch missen we de fabriek’, zegt Mels nog. `We waren eraan gewend. Het lawaai in de maalderij was onbeschrijflijk mooi.’

`Mooi?’

`De een vindt dit mooi, de ander dat.’

`Gelukkig dat we allemaal van andere meisjes houden,’ lacht de man, `anders bleven er veel over.’

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (090)

wordt vervolgd

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

Songs can be incredibly prophetic, like subconscious warnings or messages to myself, but I often don’t know what I’m trying to say till years later.

Or a prediction comes true and I couldn’t do anything to stop it, so it seems like a kind of useless magic.

Or a prediction comes true and I couldn’t do anything to stop it, so it seems like a kind of useless magic.

The first book from songwriter and Florence + the Machine frontwoman Florence Welch, Useless Magic brings together 288 pages of lyrics, never-before-seen poetry and sketches.

Taken from Welch’s own scrapbook-style journals, the book offers an extraordinary chance to see inside the creative alchemy behind some of Florence + The Machine’s chart-topping anthems.

It also offers unique personal insights into Welch’s own life from her experiences of suffering with an eating disorder to her thoughts on love and what it means to live your life in the glare of the spotlight. .

Useless Magic:

Lyrics and Poetry

by Florence Welch

Publisher Penguin Books Ltd

Imprint Fig Tree

London, 5 July 2018

Number of pages: 288

Language English

ISBN-10: 0241347939

ISBN-13: 978-0241347935

€ 28,95

# New books

Florence Welch

Lyrics and Poetry

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive W-X, Archive W-X, Art & Literature News, Florence Welch

Willem Wilmink (1936-2003) is een van de meest geliefde dichters van Nederland.

Zijn eenvoudige maar treffende gedichten en liedjes, veelal geschreven voor legendarische tv-programma’s als De Stratemakeropzeeshow, J.J. de Bom en De film van Ome Willem, spreken iedereen aan. ‘De oude school’, ‘Deze vuist op deze vuist’ en ‘Ben Ali Libi’ behoren tot de canon van de Nederlandse literatuur. Hetzelfde geldt voor Wilminks hertalingen van Middeleeuwse klassiekers. Hij was een groot kenner van poëzie uit alle tijdvakken en in al haar verschijningsvormen.

Zijn eenvoudige maar treffende gedichten en liedjes, veelal geschreven voor legendarische tv-programma’s als De Stratemakeropzeeshow, J.J. de Bom en De film van Ome Willem, spreken iedereen aan. ‘De oude school’, ‘Deze vuist op deze vuist’ en ‘Ben Ali Libi’ behoren tot de canon van de Nederlandse literatuur. Hetzelfde geldt voor Wilminks hertalingen van Middeleeuwse klassiekers. Hij was een groot kenner van poëzie uit alle tijdvakken en in al haar verschijningsvormen.

Zijn werk is doortrokken van heimwee naar een veilige kinderwereld die nooit heeft bestaan. Naar eigen zeggen is Wilmink altijd elf jaar gebleven, wat aanvankelijk zijn loopbaan en privéleven ernstig frustreerde, maar tegelijkertijd zijn poëtische kapitaal bleek. Met humor en zelfspot maakte hij zijn lange tijd door miskenning en afwijzing getekende leven leefbaar.

Voor In de man zit nog een jongen sprak neerlandicus en journalist Elsbeth Etty met tientallen tijdgenoten en intimi van Wilmink. Het resultaat is een intiem en niets verhullend portret.

Elsbeth Etty (1951) is literair criticus, columnist en voormalig bijzonder hoogleraar literaire kritiek. Ze publiceerde o.a. verschillende essay- en columnbundels. Voor Liefde is heel het leven niet, haar biografie van Henriette Roland Holst, werd ze genomineerd voor de AKO Literatuurprijs en bekroond met de Gouden Uil en de Busken Huetprijs.

In de man zit nog een jongen

Willem Wilmink – De biografie

Auteur: Elsbeth Etty

Uitgeverij: Nijgh & van Ditmar

NUR: 321

Taal Nederlands

Bladzijden 552 pp.

Bindwijze Hardcover

ISBN: 9789038806112

Publicatiedatum: 22-01-2019

Prijs: € 34,99

# New books

Willem Wilmink – De biografie

Auteur: Elsbeth Etty

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #Biography Archives, - Book News, - Book Stories, - Bookstores, Archive E-F, Archive W-X, Archive W-X, Art & Literature News, Willem Wilmink

Claire

Quoi donc ! la vôtre aussi ! la vôtre suit la mienne !

O mère au coeur profond, mère, vous avez beau

Laisser la porte ouverte afin qu’elle revienne,

Cette pierre là-bas dans l’herbe est un tombeau !

La mienne disparut dans les flots qui se mêlent ;

Alors, ce fut ton tour, Claire, et tu t’envolas.

Est-ce donc que là-haut dans l’ombre elles s’appellent,

Qu’elles s’en vont ainsi l’une après l’autre, hélas ?

Enfant qui rayonnais, qui chassais la tristesse,

Que ta mère jadis berçait de sa chanson,

Qui d’abord la charmas avec ta petitesse

Et plus tard lui remplis de clarté l’horizon,

Voilà donc que tu dors sous cette pierre grise !

Voilà que tu n’es plus, ayant à peine été !

L’astre attire le lys, et te voilà reprise,

O vierge, par l’azur, cette virginité !

Te voilà remontée au firmament sublime,

Échappée aux grands cieux comme la grive aux bois,

Et, flamme, aile, hymne, odeur, replongée à l’abîme

Des rayons, des amours, des parfums et des voix !

Nous ne t’entendrons plus rire en notre nuit noire.

Nous voyons seulement, comme pour nous bénir,

Errer dans notre ciel et dans notre mémoire

Ta figure, nuage, et ton nom, souvenir !

Pressentais-tu déjà ton sombre épithalame ?

Marchant sur notre monde à pas silencieux,

De tous les idéals tu composais ton âme,

Comme si tu faisais un bouquet pour les cieux !

En te voyant si calme et toute lumineuse,

Les coeurs les plus saignants ne haïssaient plus rien.

Tu passais parmi nous comme Ruth la glaneuse ,

Et, comme Ruth l’épi, tu ramassais le bien.

La nature, ô front pur, versait sur toi sa grâce,

L’aurore sa candeur, et les champs leur bonté ;

Et nous retrouvions, nous sur qui la douleur passe,

Toute cette douceur dans toute ta beauté !

Chaste, elle paraissait ne pas être autre chose

Que la forme qui sort des cieux éblouissants ;

Et de tous les rosiers elle semblait la rose,

Et de tous les amours elle semblait l’encens.

Ceux qui n’ont pas connu cette charmante fille

Ne peuvent pas savoir ce qu’était ce regard

Transparent comme l’eau qui s’égaie et qui brille

Quand l’étoile surgit sur l’océan hagard.

Elle était simple, franche, humble, naïve et bonne ;

Chantant à demi-voix son chant d’illusion,

Ayant je ne sais quoi dans toute sa personne

De vague et de lointain comme la vision.

On sentait qu’elle avait peu de temps sur la terre,

Qu’elle n’apparaissait que pour s’évanouir,

Et qu’elle acceptait peu sa vie involontaire ;

Et la tombe semblait par moments l’éblouir.

Elle a passé dans l’ombre où l’homme se résigne ;

Le vent sombre soufflait ; elle a passé sans bruit,

Belle, candide, ainsi qu’une plume de cygne

Qui reste blanche, même en traversant la nuit !

Elle s’en est allée à l’aube qui se lève,

Lueur dans le matin, vertu dans le ciel bleu,

Bouche qui n’a connu que le baiser du rêve,

Ame qui n’a dormi que dans le lit de Dieu !

Nous voici maintenant en proie aux deuils sans bornes,

Mère, à genoux tous deux sur des cercueils sacrés,

Regardant à jamais dans les ténèbres mornes

La disparition des êtres adorés !

Croire qu’ils resteraient ! quel songe ! Dieu les presse.

Même quand leurs bras blancs sont autour de nos cous,

Un vent du ciel profond fait frissonner sans cesse

Ces fantômes charmants que nous croyons à nous.

Ils sont là, près de nous, jouant sur notre route ;

Ils ne dédaignent pas notre soleil obscur,

Et derrière eux, et sans que leur candeur s’en doute,

Leurs ailes font parfois de l’ombre sur le mur.

Ils viennent sous nos toits ; avec nous ils demeurent ;

Nous leur disons : Ma fille, ou : Mon fils ; ils sont doux,

Riants, joyeux, nous font une caresse, et meurent. –

O mère, ce sont là les anges, voyez-vous !

C’est une volonté du sort, pour nous sévère,

Qu’ils rentrent vite au ciel resté pour eux ouvert ;

Et qu’avant d’avoir mis leur lèvre à notre verre,

Avant d’avoir rien fait et d’avoir rien souffert,

Ils partent radieux ; et qu’ignorant l’envie,

L’erreur, l’orgueil, le mal, la haine, la douleur,

Tous ces êtres bénis s’envolent de la vie

A l’âge où la prunelle innocente est en fleur !

Nous qui sommes démons ou qui sommes apôtres,

Nous devons travailler, attendre, préparer ;

Pensifs, nous expions pour nous-même ou pour d’autres ;

Notre chair doit saigner, nos yeux doivent pleurer.

Eux, ils sont l’air qui fuit, l’oiseau qui ne se pose

Qu’un instant, le soupir qui vole, avril vermeil

Qui brille et passe ; ils sont le parfum de la rose

Qui va rejoindre aux cieux le rayon du soleil !

Ils ont ce grand dégoût mystérieux de l’âme

Pour notre chair coupable et pour notre destin ;

Ils ont, êtres rêveurs qu’un autre azur réclame,

Je ne sais quelle soif de mourir le matin !

Ils sont l’étoile d’or se couchant dans l’aurore,

Mourant pour nous, naissant pour l’autre firmament ;

Car la mort, quand un astre en son sein vient éclore,

Continue, au delà, l’épanouissement !

Oui, mère, ce sont là les élus du mystère,

Les envoyés divins, les ailés, les vainqueurs,

A qui Dieu n’a permis que d’effleurer la terre

Pour faire un peu de joie à quelques pauvres coeurs.

Comme l’ange à Jacob, comme Jésus à Pierre,

Ils viennent jusqu’à nous qui loin d’eux étouffons,

Beaux, purs, et chacun d’eux portant sous sa paupière

La sereine clarté des paradis profonds.

Puis, quand ils ont, pieux, baisé toutes nos plaies,

Pansé notre douleur, azuré nos raisons,

Et fait luire un moment l’aube à travers nos claies,

Et chanté la chanson du ciel dam nos maisons,

Ils retournent là-haut parler à Dieu des hommes,

Et, pour lui faire voir quel est notre chemin,

Tout ce que nous souffrons et tout ce que nous sommes,

S’en vont avec un peu de terre dans la main.

Ils s’en vont ; c’est tantôt l’éclair qui les emporte,

Tantôt un mal plus fort que nos soins superflus.

Alors, nous, pâles, froids, l’oeil fixé sur la porte,

Nous ne savons plus rien, sinon qu’ils ne sont plus.

Nous disons : – A quoi bon l’âtre sans étincelles ?

A quoi bon la maison où ne sont plus leurs pas ?

A quoi bon la ramée où ne sont plus les ailes ?

Qui donc attendons-nous s’ils ne reviendront pas ? –

Ils sont partis, pareils au bruit qui sort des lyres.

Et nous restons là, seuls, près du gouffre où tout fuit,

Tristes ; et la lueur de leurs charmants sourires

Parfois nous apparaît vaguement dans la nuit.

Car ils sont revenus, et c’est là le mystère ;

Nous entendons quelqu’un flotter, un souffle errer,

Des robes effleurer notre seuil solitaire,

Et cela fait alors que nous pouvons pleurer.

Nous sentons frissonner leurs cheveux dans notre ombre ;

Nous sentons, lorsqu’ayant la lassitude en nous,

Nous nous levons après quelque prière sombre,

Leurs blanches mains toucher doucement nos genoux.

Ils nous disent tout bas de leur voix la plus tendre :

« Mon père, encore un peu ! ma mère, encore un jour !

« M’entends-tu ? je suis là, je reste pour t’attendre

« Sur l’échelon d’en bas de l’échelle d’amour.

« Je t’attends pour pouvoir nous en aller ensemble.

« Cette vie est amère, et tu vas en sortir.

« Pauvre coeur, ne crains rien, Dieu vit ! la mort rassemble.

« Tu redeviendras ange ayant été martyr. »

Oh ! quand donc viendrez-vous ? Vous retrouver, c’est naître.

Quand verrons-nous, ainsi qu’un idéal flambeau,

La douce étoile mort, rayonnante, apparaître

A ce noir horizon qu’on nomme le tombeau ?

Quand nous en irons-nous où vous êtes, colombes !

Où sont les enfants morts et les printemps enfuis,

Et tous les chers amours dont nous sommes les tombes,

Et toutes les clartés dont nous sommes les nuits ?

Vers ce grand ciel clément où sont tous les dictames,

Les aimés, les absents, les êtres purs et doux,

Les baisers des esprits et les regards des âmes,

Quand nous en irons-nous ? quand nous en irons-nous ?

Quand nous en irons-nous où sont l’aube et la foudre ?

Quand verrons-nous, déjà libres, hommes encor,

Notre chair ténébreuse en rayons se dissoudre,

Et nos pieds faits de nuit éclore en ailes d’or ?

Quand nous enfuirons-nous dans la joie infinie

Où les hymnes vivants sont des anges voilés,

Où l’on voit, à travers l’azur de l’harmonie,

La strophe bleue errer sur les luths étoilés ?

Quand viendrez-vous chercher notre humble coeur qui sombre ?

Quand nous reprendrez-vous à ce monde charnel,

Pour nous bercer ensemble aux profondeurs de l’ombre,

Sous l’éblouissement du regard éternel ?

Victor Hugo

(1802-1885)

Claire

(Poème)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Archive G-H, Hugo, Victor, Victor Hugo

Er is steeds minder te koop in de winkel van juffrouw Fijnhout. Er komt weinig geld binnen. En daar moet wat op gevonden worden, want ze moet ook haar medicijnen kunnen betalen. En de abonnementen op de meer dan twintig missieblaadjes.

Daar zitten ze steeds in te bladeren, op zoek naar foto’s van China. Die knippen ze uit en plakken ze in. Ze hebben al drie schriften vol met foto’s van katholieke Chinese kinderen, zodat het lijkt of bijna heel China katholiek is, maar in werkelijkheid zijn het er maar een paar duizend tussen de miljoenen. Volgens Tijger kijken de Chinezen zelf naar de katholieken zoals de mensen hier naar de Jehova’s getuigen kijken: een paar fanatieke dwepers die de bijbel naar hun hand zetten en hun kinderen nog liever dood laten gaan dan ze in te laten enten tegen pokken en kinderverlamming.

Daar zitten ze steeds in te bladeren, op zoek naar foto’s van China. Die knippen ze uit en plakken ze in. Ze hebben al drie schriften vol met foto’s van katholieke Chinese kinderen, zodat het lijkt of bijna heel China katholiek is, maar in werkelijkheid zijn het er maar een paar duizend tussen de miljoenen. Volgens Tijger kijken de Chinezen zelf naar de katholieken zoals de mensen hier naar de Jehova’s getuigen kijken: een paar fanatieke dwepers die de bijbel naar hun hand zetten en hun kinderen nog liever dood laten gaan dan ze in te laten enten tegen pokken en kinderverlamming.

Om de rekken in de winkel minder leeg te laten lijken leggen de jongens er van alles bij. Zomerappels, maar die krijgen al vlug een oud vel. Niemand koopt appels, omdat de meeste mensen zelf zomerappels in de tuin hebben. Overbodig speelgoed. Te klein geworden laarzen. Schaatsen met lint, maar wie koopt er in de zomer schaatsen? Oude jaargangen van missieblaadjes, maar iedereen wordt al onder die dingen bedolven. Soms wijst juffrouw Fijnhout iets aan in haar kast om in de rekken te zetten, een servies, kristallen glazen, een blauwe puddingvorm in de vorm van een vis, een zilveren asbak. Ze doet er glimlachend afstand van omdat ze ze toch niet meer gebruikt. Soms koopt iemand wat, niet omdat hij iets nodig heeft, maar omdat niemand wil dat juffrouw Fijnhout in armoede sterft.

In de winkel blijven vooral spullen over die wachten op volgende seizoenen, voor de herfst en de winter. Overgebleven pakjes zaaigoed voor tomaten, bonen en prei, die onder een luchtdichte glazen stolp worden bewaard en ook volgend jaar nog goed zijn.

Bij het leegruimen van een kast vindt Mels spullen die jarenlang achter andere spullen verborgen zijn gebleven. Een foto van een jongeman met de toen nog jonge juffrouw Fijnhout, een meisje nog. De jongeman heeft een arm rond haar schouder geslagen. Mels denkt dat de foto met opzet op de bovenste plank is gelegd. Achteloos legt hij hem op de hoek van de tafel. Ze ziet het direct en pakt hem op.

`Nadat die foto is gemaakt, heb ik hem nooit meer gezien.’

`Wie is het?’

`Tom, de oudste zoon van de weduwe Hubben-Houba. De broer van directeur Frits. Het was zijn laatste dag hier. Hij ging studeren, in Amerika. Een paar jaar later zou hij terugkomen, om zijn moeder op te volgen en met mij te trouwen. Ik heb nooit meer iets van hem gehoord. Zijn jongere broer Frits heeft de zaak alleen overgenomen.’

`Wist zijn moeder niet waar hij was?’

`Dat denk ik wel, maar die sprak niet met mij. De rijk geworden familie haalde haar neus op voor de dochter van een dorpssmid.’

`En andere jongens?’ vraagt Mels, de foto bekijkend waarop ze een knappe, jonge vrouw is.

`Eerst heb ik te lang gewacht. En daarna was ik te zeer teleurgesteld. En later vond ik het wel goed zoals het ging. Van mijn winkel kon ik bestaan.’

Mels ruimt alles weer op. Hij legt de foto’s op een schapje waar juffrouw Fijnhout ze kan pakken zonder op te staan.

Tijgers moeder komt Mels aflossen, want juffrouw Fijnhout mag niet meer alleen zijn. Om de beurt blijven de vrouwen uit de buurt ‘s nachts bij haar.

Mels gaat naar huis.

Ze hebben bezoek. De moeder van Jacob zit in de kamer. Ze drinken thee.

`Ik heb wat voor je meegebracht’, zegt Jacobs moeder. Uit haar tas haalt ze het schrift. `Jacob wilde dat ik de verhalen die hij heeft opgeschreven aan jou gaf.’

`Wilt u ze zelf niet houden?’

`Ik kan niet lezen. Jacob heeft vier jaar in een sanatorium gelegen. Daar heeft hij leren lezen en schrijven.’

`En vioolspelen?’

`Wij maken allemaal muziek. Dat is hem met de paplepel ingegoten.’

`Dank u voor het schrift’, zegt Mels. `Jammer dat ik Jacob maar zo kort heb gekend.’

`Lang genoeg om vrienden te worden.’ Jacobs moeder staat op. Mels’ moeder brengt haar naar de deur.

`U komt nog maar eens aan’, zegt moeder.

`Wij gaan hier weg’, zegt Jacobs moeder. `Wij hebben hier weinig geluk gevonden. Misschien gaat het ons ergens anders beter.’

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (089)

wordt vervolgd

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

Onlangs verscheen de dichtbundel Gedichten van Paul Bezembinder, bij Uitg. Pittige Pixels Amsterdam, 2018, Eerste druk, 104 pag., ISBN 978-90-829774-0-0.

Bezembinder (1961) studeerde theoretische natuurkunde in Nijmegen. In zijn poëzie zoekt hij in vooral klassieke versvormen en thema’s naar de balans tussen serieuze poëzie, pastiche en smartlap.

Bezembinder (1961) studeerde theoretische natuurkunde in Nijmegen. In zijn poëzie zoekt hij in vooral klassieke versvormen en thema’s naar de balans tussen serieuze poëzie, pastiche en smartlap.

Zijn gedichten (Nederlands) en vertalingen (Russisch – Nederlands) verschenen in verschillende (online) literaire tijdschriften, waaronder in het bijzonder op fleursdumal.nl. De bundel Gedichten is zijn tweede bundel.

Bezembinders eerste bundel, Kwatrijnen. Filosofische Verkenningen, verscheen in de reeks digitale publicaties van fleursdumal.nl: Fantom Ebooks.

De reeks is een uitgave van Art Brut Digital Editions, die onregelmatig bijzondere kunst- en literatuurprojecten publiceert. Deze bundel is als pdf op de site van fleursdumal.nl te vinden.

Meer voorbeelden van Bezembinders werk zijn te vinden op de website van de auteur, paulbezembinder.nl

Paul Bezembinder

Kwatrijnen

Uitgeverij. Pittige Pixels Amsterdam,

2018 Eerste druk,

104 pag.,

ISBN 978-90-829774-0-0

De bundel is per e-mail te bestellen.

Prijs: €17.50.

www.paulbezembinder.nl

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, - Book News, Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Art & Literature News, Bezembinder, Paul, PRESS & PUBLISHING

Je ne crois plus

aux mots des poème

Je ne crois plus aux mots des poèmes,

car ils ne soulèvent rien

et ne font rien.

Autrefois il y avait des poèmes

qui envoyaient un guerrier

se faire trouer la gueule,

mais la gueule trouée

le guerrier était mort,

et que lui restait-il de sa gloire à lui ?

Je veux dire de son transport ?

Rien.

Il était mort,

cela servait à éduquer dans les classes

les cons et les fils de cons qui viendraient

après lui et sont allés à de nouvelles guerres

atomiquement réglementées,

je crois qu’il y a un état où le guerrier

la gueule trouée

et mort, reste là

il continue à se battre

et à avancer,

il n’est pas mort,

il avance pour l’éternité.

Mais qui en voudrait

sauf moi ?

Et moi, qu’il vienne celui

qui me trouera la gueule

je l’attends.

Antonin Artaud

(1896 — 1948)

Je ne crois plus aux mots des poème

Poème

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Antonin Artaud, Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Artaud, Antonin

Het thema van de Poëzieweek 2019 is Vrijheid, met als motto: Zonder handen, zonder tanden.

De week opent op donderdag 31 januari met Gedichtendag en wordt woensdagavond 6 februari feestelijk afgesloten met De Grote Poëzieprijs, de Awater Poëzieprijs en de Turing Gedichtenwedstrijd. Tom Lanoye schrijft het Poëziegeschenk Vrij – Wij?, cadeau van de boekwinkel bij aankoop van € 12,50 aan poëzie.

Met Gedichtendag (31 januari 2019) gaat op de laatste donderdag van januari traditiegetrouw de Poëzieweek van start. Gedichtendag, sinds 2000 georganiseerd door Poetry International Rotterdam, is hét poëziefeest van Nederland en Vlaanderen.

Poëzieliefhebbers in Nederland en Vlaanderen organiseren die dag een grote diversiteit aan eigen poëzieactiviteiten en ook de media klinken die dag een stuk poëtischer.

Poëzieliefhebbers in Nederland en Vlaanderen organiseren die dag een grote diversiteit aan eigen poëzieactiviteiten en ook de media klinken die dag een stuk poëtischer.

Voor de enorme hoeveelheid optredens, publicaties, poëzieprijzen, -programma’s en -activiteiten is één dag simpelweg veel te kort!

De Poëzieweek wil een zo groot mogelijk bereik voor poëzie creëren en bundelt tal van activiteiten van organisatoren in Nederland en Vlaanderen.

De Poëzieweek is een samenwerking van Stichting CPNB, Poëziecentrum, Stichting Poetry International, Vlaams Fonds voor de Letteren, Nederlands Letterenfonds, Stichting Lezen Nederland, Iedereen Leest Vlaanderen, De Schrijverscentrale, Boek.be, Taalunie, Stichting Van Beuningen/Peterich-fonds, Turing Foundation, Awater, Het Literatuurhuis, Poëzieclub, SLAG, School der Poëzie en De Nieuwe Oost | Wintertuin.

# Voor een overzicht van alle activiteiten zie de website POËZIEWEEK

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #Archive A-Z Sound Poetry, #Archive Concrete & Visual Poetry, #More Poetry Archives, *War Poetry Archive, - Book Lovers, - Bookstores, Art & Literature News, LIGHT VERSE, Literary Events, MODERN POETRY, Poetry International, Poetry Slam, Poëziepaleis, Poëzieweek, STREET POETRY, THEATRE, Tilt Festival Tilburg, Tom Lanoye

THE LYNCHING OF JUBE BENSON

Gordon Fairfax’s library held but three men, but the air was dense with clouds of smoke. The talk had drifted from one topic to another much as the smoke wreaths had puffed, floated, and thinned away. Then Handon Gay, who was an ambitious young reporter, spoke of a lynching story in a recent magazine, and the matter of punishment without trial put new life into the conversation.

“I should like to see a real lynching,” said Gay rather callously.

“I should like to see a real lynching,” said Gay rather callously.

“Well, I should hardly express it that way,” said Fairfax, “but if a real, live lynching were to come my way, I should not avoid it.”

“I should,” spoke the other from the depths of his chair, where he had been puffing in moody silence. Judged by his hair, which was freely sprinkled with gray, the speaker might have been a man of forty-five or fifty, but his face, though lined and serious, was youthful, the face of a man hardly past thirty.

“What, you, Dr. Melville? Why, I thought that you physicians wouldn’t weaken at anything.”

“I have seen one such affair,” said the doctor gravely, “in fact, I took a prominent part in it.”

“Tell us about it,” said the reporter, feeling for his pencil and notebook, which he was, nevertheless, careful to hide from the speaker.

The men drew their chairs eagerly up to the doctor’s, but for a minute he did not seem to see them, but sat gazing abstractedly into the fire, then he took a long draw upon his cigar and began:

“I can see it all very vividly now. It was in the summer time and about seven years ago. I was practising at the time down in the little town of Bradford. It was a small and primitive place, just the location for an impecunious medical man, recently out of college.

“In lieu of a regular office, I attended to business in the first of two rooms which I rented from Hiram Daly, one of the more prosperous of the townsmen. Here I boarded and here also came my patients—white and black—whites from every section, and blacks from ‘nigger town,’ as the west portion of the place was called.

“The people about me were most of them coarse and rough, but they were simple and generous, and as time passed on I had about abandoned my intention of seeking distinction in wider fields and determined to settle into the place of a modest country doctor. This was rather a strange conclusion for a young man to arrive at, and I will not deny that the presence in the house of my host’s beautiful young daughter, Annie, had something to do with my decision. She was a beautiful young girl of seventeen or eighteen, and very far superior to her surroundings. She had a native grace and a pleasing way about her that made everybody that came under her spell her abject slave. White and black who knew her loved her, and none, I thought, more deeply and respectfully than Jube Benson, the black man of all work about the place.

“He was a fellow whom everybody trusted; an apparently steady-going, grinning sort, as we used to call him. Well, he was completely under Miss Annie’s thumb, and would fetch and carry for her like a faithful dog. As soon as he saw that I began to care for Annie, and anybody could see that, he transferred some of his allegiance to me and became my faithful servitor also. Never did a man have a more devoted adherent in his wooing than did I, and many a one of Annie’s tasks which he volunteered to do gave her an extra hour with me. You can imagine that I liked the boy and you need not wonder any more that as both wooing and my practice waxed apace, I was content to give up my great ambitions and stay just where I was.

“It wasn’t a very pleasant thing, then, to have an epidemic of typhoid break out in the town that kept me going so that I hardly had time for the courting that a fellow wants to carry on with his sweetheart while he is still young enough to call her his girl. I fumed, but duty was duty, and I kept to my work night and day. It was now that Jube proved how invaluable he was as a coadjutor. He not only took messages to Annie, but brought sometimes little ones from her to me, and he would tell me little secret things that he had overheard her say that made me throb with joy and swear at him for repeating his mistress’ conversation. But best of all, Jube was a perfect Cerberus, and no one on earth could have been more effective in keeping away or deluding the other young fellows who visited the Dalys. He would tell me of it afterwards, chuckling softly to himself. ‘An,’ Doctah, I say to Mistah Hemp Stevens, “‘Scuse us, Mistah Stevens, but Miss Annie, she des gone out,” an’ den he go outer de gate lookin’ moughty lonesome. When Sam Elkins come, I say, “Sh, Mistah Elkins, Miss Annie, she done tuk down,” an’ he say, “What, Jube, you don’ reckon hit de——” Den he stop an’ look skeert, an’ I say, “I feared hit is, Mistah Elkins,” an’ sheks my haid ez solemn. He goes outer de gate lookin’ lak his bes’ frien’ done daid, an’ all de time Miss Annie behine de cu’tain ovah de po’ch des’ a laffin’ fit to kill.’

“Jube was a most admirable liar, but what could I do? He knew that I was a young fool of a hypocrite, and when I would rebuke him for these deceptions, he would give way and roll on the floor in an excess of delighted laughter until from very contagion I had to join him—and, well, there was no need of my preaching when there had been no beginning to his repentance and when there must ensue a continuance of his wrong-doing.

“This thing went on for over three months, and then, pouf! I was down like a shot. My patients were nearly all up, but the reaction from overwork made me an easy victim of the lurking germs. Then Jube loomed up as a nurse. He put everyone else aside, and with the doctor, a friend of mine from a neighbouring town, took entire charge of me. Even Annie herself was put aside, and I was cared for as tenderly as a baby. Tom, that was my physician and friend, told me all about it afterward with tears in his eyes. Only he was a big, blunt man and his expressions did not convey all that he meant. He told me how my nigger had nursed me as if I were a sick kitten and he my mother. Of how fiercely he guarded his right to be the sole one to ‘do’ for me, as he called it, and how, when the crisis came, he hovered, weeping, but hopeful, at my bedside, until it was safely passed, when they drove him, weak and exhausted, from the room. As for me, I knew little about it at the time, and cared less. I was too busy in my fight with death. To my chimerical vision there was only a black but gentle demon that came and went, alternating with a white fairy, who would insist on coming in on her head, growing larger and larger and then dissolving. But the pathos and devotion in the story lost nothing in my blunt friend’s telling.

“It was during the period of a long convalescence, however, that I came to know my humble ally as he really was, devoted to the point of abjectness. There were times when for very shame at his goodness to me, I would beg him to go away, to do something else. He would go, but before I had time to realise that I was not being ministered to, he would be back at my side, grinning and pottering just the same. He manufactured duties for the joy of performing them. He pretended to see desires in me that I never had, because he liked to pander to them, and when I became entirely exasperated, and ripped out a good round oath, he chuckled with the remark, ‘Dah, now, you sholy is gittin’ well. Nevah did hyeah a man anywhaih nigh Jo’dan’s sho’ cuss lak dat.’

“Why, I grew to love him, love him, oh, yes, I loved him as well—oh, what am I saying? All human love and gratitude are damned poor things; excuse me, gentlemen, this isn’t a pleasant story. The truth is usually a nasty thing to stand.

“It was not six months after that that my friendship to Jube, which he had been at such great pains to win, was put to too severe a test.

“It was in the summer time again, and as business was slack, I had ridden over to see my friend, Dr. Tom. I had spent a good part of the day there, and it was past four o’clock when I rode leisurely into Bradford. I was in a particularly joyous mood and no premonition of the impending catastrophe oppressed me. No sense of sorrow, present or to come, forced itself upon me, even when I saw men hurrying through the almost deserted streets. When I got within sight of my home and saw a crowd surrounding it, I was only interested sufficiently to spur my horse into a jog trot, which brought me up to the throng, when something in the sullen, settled horror in the men’s faces gave me a sudden, sick thrill. They whispered a word to me, and without a thought, save for Annie, the girl who had been so surely growing into my heart, I leaped from the saddle and tore my way through the people to the house.

“It was Annie, poor girl, bruised and bleeding, her face and dress torn from struggling. They were gathered round her with white faces, and, oh, with what terrible patience they were trying to gain from her fluttering lips the name of her murderer. They made way for me and I knelt at her side. She was beyond my skill, and my will merged with theirs. One thought was in our minds.

“‘Who?’ I asked.

“Her eyes half opened, ‘That black——’ She fell back into my arms dead.

“We turned and looked at each other. The mother had broken down and was weeping, but the face of the father was like iron.

“‘It is enough,’ he said; ‘Jube has disappeared.’ He went to the door and said to the expectant crowd, ‘She is dead.’

“I heard the angry roar without swelling up like the noise of a flood, and then I heard the sudden movement of many feet as the men separated into searching parties, and laying the dead girl back upon her couch, I took my rifle and went out to join them.

“As if by intuition the knowledge had passed among the men that Jube Benson had disappeared, and he, by common consent, was to be the object of our search. Fully a dozen of the citizens had seen him hastening toward the woods and noted his skulking air, but as he had grinned in his old good-natured way they had, at the time, thought nothing of it. Now, however, the diabolical reason of his slyness was apparent. He had been shrewd enough to disarm suspicion, and by now was far away. Even Mrs. Daly, who was visiting with a neighbour, had seen him stepping out by a back way, and had said with a laugh, ‘I reckon that black rascal’s a-running off somewhere.’ Oh, if she had only known.

“‘To the woods! To the woods!’ that was the cry, and away we went, each with the determination not to shoot, but to bring the culprit alive into town, and then to deal with him as his crime deserved.

“I cannot describe the feelings I experienced as I went out that night to beat the woods for this human tiger. My heart smouldered within me like a coal, and I went forward under the impulse of a will that was half my own, half some more malignant power’s. My throat throbbed drily, but water nor whiskey would not have quenched my thirst. The thought has come to me since that now I could interpret the panther’s desire for blood and sympathise with it, but then I thought nothing. I simply went forward, and watched, watched with burning eyes for a familiar form that I had looked for as often before with such different emotions.

“Luck or ill-luck, which you will, was with our party, and just as dawn was graying the sky, we came upon our quarry crouched in the corner of a fence. It was only half light, and we might have passed, but my eyes had caught sight of him, and I raised the cry. We levelled our guns and he rose and came toward us.

“‘I t’ought you wa’n’t gwine see me,’ he said sullenly, ‘I didn’t mean no harm.’

“‘Harm!’

“Some of the men took the word up with oaths, others were ominously silent.

“We gathered around him like hungry beasts, and I began to see terror dawning in his eyes. He turned to me, ‘I’s moughty glad you’s hyeah, doc,’ he said, ‘you ain’t gwine let ’em whup me.’

“‘Whip you, you hound,’ I said, ‘I’m going to see you hanged,’ and in the excess of my passion I struck him full on the mouth. He made a motion as if to resent the blow against even such great odds, but controlled himself.

“‘W’y, doctah,’ he exclaimed in the saddest voice I have ever heard, ‘w’y, doctah! I ain’t stole nuffin’ o’ yo’n, an’ I was comin’ back. I only run off to see my gal, Lucy, ovah to de Centah.’

“‘You lie!’ I said, and my hands were busy helping the others bind him upon a horse. Why did I do it? I don’t know. A false education, I reckon, one false from the beginning. I saw his black face glooming there in the half light, and I could only think of him as a monster. It’s tradition. At first I was told that the black man would catch me, and when I got over that, they taught me that the devil was black, and when I had recovered from the sickness of that belief, here were Jube and his fellows with faces of menacing blackness. There was only one conclusion: This black man stood for all the powers of evil, the result of whose machinations had been gathering in my mind from childhood up. But this has nothing to do with what happened.

“After firing a few shots to announce our capture, we rode back into town with Jube. The ingathering parties from all directions met us as we made our way up to the house. All was very quiet and orderly. There was no doubt that it was as the papers would have said, a gathering of the best citizens. It was a gathering of stern, determined men, bent on a terrible vengeance.

“We took Jube into the house, into the room where the corpse lay. At sight of it, he gave a scream like an animal’s and his face went the colour of storm-blown water. This was enough to condemn him. We divined, rather than heard, his cry of ‘Miss Ann, Miss Ann, oh, my God, doc, you don’t t’ink I done it?’

“Hungry hands were ready. We hurried him out into the yard. A rope was ready. A tree was at hand. Well, that part was the least of it, save that Hiram Daly stepped aside to let me be the first to pull upon the rope. It was lax at first. Then it tightened, and I felt the quivering soft weight resist my muscles. Other hands joined, and Jube swung off his feet.

“No one was masked. We knew each other. Not even the Culprit’s face was covered, and the last I remember of him as he went into the air was a look of sad reproach that will remain with me until I meet him face to face again.

“We were tying the end of the rope to a tree, where the dead man might hang as a warning to his fellows, when a terrible cry chilled us to the marrow.

“‘Cut ‘im down, cut ‘im down, he ain’t guilty. We got de one. Cut him down, fu’ Gawd’s sake. Here’s de man, we foun’ him hidin’ in de barn!’

“Jube’s brother, Ben, and another Negro, came rushing toward us, half dragging, half carrying a miserable-looking wretch between them. Someone cut the rope and Jube dropped lifeless to the ground.

“‘Oh, my Gawd, he’s daid, he’s daid!’ wailed the brother, but with blazing eyes he brought his captive into the centre of the group, and we saw in the full light the scratched face of Tom Skinner—the worst white ruffian in the town—but the face we saw was not as we were accustomed to see it, merely smeared with dirt. It was blackened to imitate a Negro’s.

“God forgive me; I could not wait to try to resuscitate Jube. I knew he was already past help, so I rushed into the house and to the dead girl’s side. In the excitement they had not yet washed or laid her out. Carefully, carefully, I searched underneath her broken finger nails. There was skin there. I took it out, the little curled pieces, and went with it to my office.

“There, determinedly, I examined it under a powerful glass, and read my own doom. It was the skin of a white man, and in it were embedded strands of short, brown hair or beard.

“How I went out to tell the waiting crowd I do not know, for something kept crying in my ears, ‘Blood guilty! Blood guilty!’

“The men went away stricken into silence and awe. The new prisoner attempted neither denial nor plea. When they were gone I would have helped Ben carry his brother in, but he waved me away fiercely, ‘You he’ped murder my brothah, you dat was his frien’, go ‘way, go ‘way! I’ll tek him home myse’f’ I could only respect his wish, and he and his comrade took up the dead man and between them bore him up the street on which the sun was now shining full.

“I saw the few men who had not skulked indoors uncover as they passed, and I—I—stood there between the two murdered ones, while all the while something in my ears kept crying, ‘Blood guilty! Blood guilty!'”

The doctor’s head dropped into his hands and he sat for some time in silence, which was broken by neither of the men, then he rose, saying, “Gentlemen, that was my last lynching.”

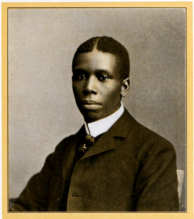

Paul Laurence Dunbar

(1872 – 1906)

The Lynching Of Jube Benson

From The Heart Of Happy Hollow, a collection of short stories reprinted in 1904 by Dodd, Mead and Company, New York.

Short Story

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Archive C-D, Dunbar, Paul Laurence, Dunbar, Paul Laurence, Paul Laurence Dunbar, Paul Laurence Dunbar

Op 24 januari 2019 verscheen ‘Fantoommerrie’ de nieuwe dichtbundel van Marieke Lucas Rijneveld, een van de grootste nieuwe talenten van de Nederlandse letteren.

Je zou kunnen zeggen dat deze bundel verder gaat waar haar vorige bundel,‘Kalfsvlies’, was opgehouden, maar dat suggereert dat we met een vervolg te maken hebben, en dat is niet zo.

Je zou kunnen zeggen dat deze bundel verder gaat waar haar vorige bundel,‘Kalfsvlies’, was opgehouden, maar dat suggereert dat we met een vervolg te maken hebben, en dat is niet zo.

Deze bundel is een nieuwe verkenning in het universum van Rijneveld, dat paradoxaal genoeg aan de ene kant compleet onnavolgbaar is, maar aan de andere kant ook onmiddellijk herkenbaar en altijd eigen. Over een oma die onsterfelijk had moeten zijn, het noodlottig einde van een onvoorzichtige kat, over dromen natuurlijk: mooie en lelijke, over bidden om speelgoed, de zithouding van de schrijver – en over voorleesvaders, die lastige vragen krijgen: ‘waar komen kinderen vandaan als ouders nooit kussen?

‘Fantoommerrie’ is een dichtbundel om in te verdwalen, en dan te besluiten om er te blijven.

Marieke Lucas Rijneveld

Fantoommerrie

Gedichten

Gepubliceerd 24 januari 2019

Uitgeverij Atlas Contact

Pagina’s 64

Type Paperback / softback

ISBN 9789025453459

€ 19,99

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Archive Q-R, Archive Q-R, Art & Literature News, Marieke Lucas Rijneveld, Rijneveld, Marieke Lucas

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature