Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Het Literaire Pleidooi

Elisabeth Leijnse over Patricia de Martelaere

Tijdens de eerste zitting van onze literaire rechtbank ontving rechter Philip Freriks Joke Linders en Gerda Dendooven die ervoor pleitten om Annie M.G. Schmidt op te nemen in Het Pantheon: de permanente tentoonstelling van het Letterkundig Museum (Den Haag). De tekst van openbaar aanklager Joke Linders vindt u hier. Elisabeth Leijnse en Marja Pruis wilden op hun beurt dat Patricia de Martelaere een plaatsje krijgt in deze eregalerij. Uiteindelijk besloot de jury (het publiek) dat aan Annie M.G. Schmidt een gelegenheidstentoonstelling wordt gewijd! Hieronder leest u het vurige betoog dat Elisabeth Leijnse hield om Patricia de Martelaere op te nemen in het Pantheon. Of… toch niet?

De grafkelder van het Letterkundig Museum

Door Elisabeth Leijnse

Zes dode auteurs werden niet bijgezet in de grafkelder van het Letterkundig Museum. Is dit misschien een bewijs dat ze nog springlevend zijn? Jammer genoeg niet lijfelijk. Was één van hen nog onder ons, Herman de Coninck, dan was de kans groot dat hij nu hier in mijn plaats had gestaan. Hij was een groot bewonderaar van het werk van Patricia de Martelaere. ‘Zij is de enige filosofe in dit taalgebied,’ schreef hij, ‘die van filosofie niet alleen iets onacademisch, iets begrijpelijks, maar ook iets aangrijpends kan maken.’ Wie de muzen liefheeft nemen zij jong tot zich. De Coninck werd 53 jaar, De Martelaere net geen 52. De woorden dood en troost komen in hun werk vaak voor. De Coninck schreef de essaybundel Over de troost van pessimisme, De Martelaere publiceerde de bundel Een verlangen naar ontroostbaarheid.

Dat Patricia de Martelaere, áls ze nog had geleefd, hier zou hebben gestaan om een pleidooi te houden voor een ánder Nederlandstalig auteur, wie weet voor Annie M.G. Schmidt, valt echter zeer te betwijfelen. Ik acht de kans groot dat zij het Letterkundig Museum of het Letterenhuis zelfs nooit heeft betreden. Het idee van een rederijkerswedstrijd voor dode zangvogeltjes zou ze bespottelijk hebben gevonden. Dat bovendien een volksjury beslist welk vogeltje bekransd wordt: een verwerpelijke vorm van literair populisme. Dit verhindert niet dat De Martelaere in haar laatste roman juist haar postume mededingster Annie M.G. Schmidt ten tonele voert als een zeer leesbare schrijfster. Of liever als een voorleesbare schrijfster. In Het onverwachte antwoord schrijft een van de personages aan haar afwezige minnaar:

nu wil ik op je schoot zitten, met mijn armen rond je nek, en je moet over mijn rug strelen en mij verhalen vertellen, sprookjes en zo, of versjes van Annie M.G. Schmidt, alles is goed, als het maar niet voor volwassenen is.

► Lees verder: Vervolg literair pleidooi op website deBuren…..

kempis.nl poetry magazine

.jpg)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Annie M.G. Schmidt, Coninck, Herman de, Martelaere, Patricia de, The talk of the town

.jpg)

Hank Denmore

Moord in lichtdruk

drieënveertig

De twee kwamen op Rope af, die Lime in de onderbuik trapte, maar Antonio nam Rope zwijgend in een judogreep. Spartelend hing Rope in de armen van de Napolitaan en probeerde vergeefs aan diens greep te ontkomen. Vloekend kwam Lime overeind en uit diens geelgroene ogen straalde een ongelooflijke haat. Hij haalde een smerige zakdoek te voorschijn, stompte Rope in diens maag en propte de zakdoek snel in de van pijn opengesperde mond.

Tino schopte de benen van de spartelende figuur onderuit en ging zwaar op diens buik zitten. De andere arrestanten reageerden door stil op hun britsen te gaan liggen, wie niets ziet kan ook niets vertellen.

Vincente keek naar Tino die naar de keel van Rope knikte, daarop zette Vincente zijn rechterschoen op de keel van de onderliggende man en begon te drukken. Rope spartelde zo hevig tegen dat hij even los kwam. Met een ruk trok hij de zakdoek uit zijn mond en schreeuwde uit alle macht om hulp.

De deur van het bureau werd opengegooid en de agent die Rope al eerder bij de Mustang als CIA-agent had herkend kwam snel aanlopen. Hij zag Rope zijn pijnlijke keel wrijven en de verhitte gezichten van de anderen. Op zijn vraag wat er aan de hand was werd niet gereageerd. Toen maakte de agent de celdeur open, Rope werd er uit gehaald en in de cel er naast bij twee anderen ingesloten. De agent vroeg aan Rope of hij nog iets voor hem kon doen. Rope schudde nee en ging op een brits liggen, zover mogelijk van de traliewand tussen de cellen in. Door de stalen spijlen heen zag hij de van haat vertrokken gezichten van zijn eerdere celmaten en begon te grijnzen.

Toen voelde hij een klopje op zijn schouder. Toen hij opkeek zag hij dat een van de twee celgenoten van de tegen de traliewand gemonteerde brits was opgestaan en daar naar toe wees. Rope schudde nee, waarop ook de andere kwam aanlopen. Die haalde uit een plooi in zijn stijve jeansbroek een lange stevige naald en kwam hiermee dreigend op zijn gezicht af. Rope koos eieren voor zijn geld en ging tergend langzaam op de hem aangewezen brits liggen.

Zich toch veilig voelend riep hij hatelijk naar Lime: ‘Moet je nog een trap? Wacht dan totdat ik weer buiten sta, dan pak ik je wel. Zal ik de groeten doen aan de KGB, meneer Tino?’ Hij haalde het beruchte nylonkoord uit zijn broekzak, draaide de einden stevig om zijn hand en zwaaide uitdagend met het lusvormige koord naar Lime.

‘Zal ik jou een stropdas geven of meneer Vandezzi?’

Terwijl hij het koord op en neer zwaaide riep een van de twee celgenoten zijn naam. Verbaasd keek hij om, op dat ogenblik dook Lime naar het koord en trok met een ruk het koord en Rope’s arm door de tralies heen. Bliksemsnel pakte Vincente de arm in een houdgreep, terwijl Lime het koord losrukte. Antonio bukte zich naar een broekspijp van Rope en trok die strak tegen het traliewerk aan.

Toen trok Vincente de arm van Rope zo hard tegen de zware stalen tralies aan, dat het hoofd van Rope binnen het bereik van Lime kwam. Die gooide het koord over Rope’s van pijn geopende mond, haalde snel de einden om een tralie en trok het koord strak.

Tino kwam op hem af en riep: ‘Dit is je laatste kans, toen Knife en Doc die griet ondervroegen, heb jij toen Knife omgelegd?’

Rope riep met moeite dat hij daar niets vanaf wist.

Tino trok woest aan het haar van Rope en draaide diens hoofd zo erg dat de nekwervels kraakten en herhaalde zijn vraag, waarop Rope met een van pijn vertrokken gezicht ja kreunde.

Lime keek naar Tino, die knikte, waarop Vincente het koord strakker aantrok.

Rope wilde schreeuwen maar het strakgetrokken koord drukte zijn tong in de keelholte en sloot de luchtwegen af. Hij begon wild met zijn vrije been te schoppen, maar het koord werd steeds strakker aangehaald. Langzaam werd het gezicht van Rope blauw en sneed het nylonkoord de mond in een afzichtelijke wond open, waardoor de tanden als in een horrorfilm zichtbaar werden. Door de enorme druk van de longen, die wanhopig probeerden de samengeperste lucht kwijt te raken, puilden de ogen uit de kassen. Het schoppen werd minder en wat Rope dikwijls bij zijn slachtoffers had zien gebeuren, overkwam hem nu zelf. Het schoppen ging over in spastische bewegingen, zijn urine stroomde op de brits en kletterde op de betonnen celvloer. Vincente kon na enige tijd de arm loslaten, alle leven was uit Rope verdwenen.

.jpg)

Hank Denmore: Moord in lichtdruk

kempis.nl poetry magazine

(wordt vervolgd)

More in: -Moord in lichtdruk

Edith Södergran

(1892-1923)

The Stars

When night comes

I stand on the steps and listen,

stars swarm in the yard

and I stand in the dark.

Listen, a star fell with a clang!

Don’t go out in the grass with bare feet;

my yard is full of shards.

Hope

I want to let go –

so I don’t give a damn about fine writing,

I’m rolling my sleeves up.

The dough’s rising…

Oh what a shame

I can’t bake cathedrals…

that sublimity of style

I’ve always yearned for…

Child of our time –

haven’t you found the right shell for your soul?

Before I die I shall

bake a cathedral.

Edith Södergran poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Södergran, Edith

.jpg)

William Shakespeare

(1564-1616)

THE SONNETS

65

Since brass, nor stone, nor earth, nor boundless sea,

But sad mortality o’ersways their power,

How with this rage shall beauty hold a plea,

Whose action is no stronger than a flower?

O how shall summer’s honey breath hold out,

Against the wrackful siege of batt’ring days,

When rocks impregnable are not so stout,

Nor gates of steel so strong but time decays?

O fearful meditation, where alack,

Shall Time’s best jewel from Time’s chest lie hid?

Or what strong hand can hold his swift foot back,

Or who his spoil of beauty can forbid?

O none, unless this miracle have might,

That in black ink my love may still shine bright.

![]()

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shakespeare Sonnets

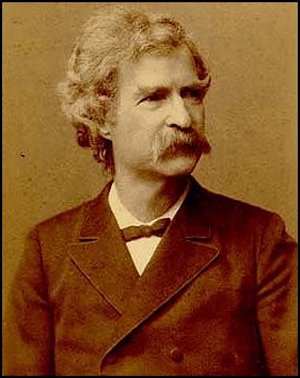

Mark Twain

(1835-1910)

Eve’s Diary

Translated from the original

Saturday.—I am almost a whole day old, now. I arrived yesterday. That is as it seems to me. And it must be so, for if there was a day-before-yesterday I was not there when it happened, or I should remember it. It could be, of course, that it did happen, and that I was not noticing. Very well; I will be very watchful, now, and if any day-before-yesterdays happen I will make a note of it. It will be best to start right and not let the record get confused, for some instinct tells me that these details are going to be important to the historian some day. For I feel like an experiment, I feel exactly like an experiment; it would be impossible for a person to feel more like an experiment than I do, and so I am coming to feel convinced that that is what I am—an experiment; just an experiment, and nothing more.

Then if I am an experiment, am I the whole of it? No, I think not; I think the rest of it is part of it. I am the main part of it, but I think the rest of it has its share in the matter. Is my position assured, or do I have to watch it and take care of it? The latter, perhaps. Some instinct tells me that eternal vigilance is the price of supremacy. [That is a good phrase, I think, for one so young.]

Everything looks better to-day than it did yesterday. In the rush of finishing up yesterday, the mountains were left in a ragged condition, and some of the plains were so cluttered with rubbish and remnants that the aspects were quite distressing. Noble and beautiful works of art should not be subjected to haste; and this majestic new world is indeed a most noble and beautiful work. And certainly marvellously near to being perfect, notwithstanding the shortness of the time. There are too many stars in some places and not enough in others, but that can be remedied presently, no doubt. The moon got loose last night, and slid down and fell out of the scheme—a very great loss; it breaks my heart to think of it. There isn’t another thing among the ornaments and decorations that is comparable to it for beauty and finish. It should have been fastened better. If we can only get it back again—

But of course there is no telling where it went to. And besides, whoever gets it will hide it; I know it because I would do it myself. I believe I can be honest in all other matters, but I already begin to realize that the core and centre of my nature is love of the beautiful, a passion for the beautiful, and that it would not be safe to trust me with a moon that belonged to another person and that person didn’t know I had it. I could give up a moon that I found in the daytime, because I should be afraid some one was looking; but if I found it in the dark, I am sure I should find some kind of an excuse for not saying anything about it. For I do love moons, they are so pretty and so romantic. I wish we had five or six; I would never go to bed; I should never get tired lying on the moss-bank and looking up at them. Stars are good, too. I wish I could get some to put in my hair. But I suppose I never can. You would be surprised to find how far off they are, for they do not look it. When they first showed, last night, I tried to knock some down with a pole, but it didn’t reach, which astonished me; then I tried clods till I was all tired out, but I never got one. It was because I am left-handed and cannot throw good. Even when I aimed at the one I wasn’t after I couldn’t hit the other one, though I did make some close shots, for I saw the black blot of the clod sail right into the midst of the golden clusters forty or fifty times, just barely missing them, and if I could have held out a little longer maybe I could have got one.

So I cried a little, which was natural, I suppose, for one of my age, and after I was rested I got a basket and started for a place on the extreme rim of the circle, where the stars were close to the ground and I could get them with my hands, which would be better, anyway, because I could gather them tenderly then, and not break them. But it was farther than I thought, and at last I had to give it up; I was so tired I couldn’t drag my feet another step; and besides, they were sore and hurt me very much. I couldn’t get back home; it was too far and turning cold; but I found some tigers and nestled in among them and was most adorably comfortable, and their breath was sweet and pleasant, because they live on strawberries. I had never seen a tiger before, but I knew them in a minute by the stripes. If I could have one of those skins, it would make a lovely gown.

To-day I am getting better ideas about distances. I was so eager to get hold of every pretty thing that I giddily grabbed for it, sometimes when it was too far off, and sometimes when it was but six inches away but seemed a foot—alas, with thorns between! I learned a lesson; also I made an axiom, all out of my own head—my very first one: The scratched Experiment shuns the thorn. I think it is a very good one for one so young.

I followed the other Experiment around, yesterday afternoon, at a distance, to see what it might be for, if I could. But I was not able to make out. I think it is a man. I had never seen a man, but it looked like one, and I feel sure that that is what it is. I realize that I feel more curiosity about it than about any of the other reptiles. If it is a reptile, and I suppose it is; for it has frowsy hair and blue eyes, and looks like a reptile. It has no hips; it tapers like a carrot; when it stands, it spreads itself apart like a derrick; so I think it is a reptile, though it may be architecture.

I was afraid of it at first, and started to run every time it turned around, for I thought it was going to chase me; but by-and-by I found it was only trying to get away, so after that I was not timid any more, but tracked it along, several hours, about twenty yards behind, which made it nervous and unhappy. At last it was a good deal worried, and climbed a tree. I waited a good while, then gave it up and went home.

To-day the same thing over. I’ve got it up the tree again.

Sunday.—It is up there yet. Resting, apparently. But that is a subterfuge: Sunday isn’t the day of rest; Saturday is appointed for that. It looks to me like a creature that is more interested in resting than in anything else. It would tire me to rest so much. It tires me just to sit around and watch the tree. I do wonder what it is for; I never see it do anything.

They returned the moon last night, and I was so happy! I think it is very honest of them. It slid down and fell off again, but I was not distressed; there is no need to worry when one has that kind of neighbors; they will fetch it back. I wish I could do something to show my appreciation. I would like to send them some stars, for we have more than we can use. I mean I, not we, for I can see that the reptile cares nothing for such things. It has low tastes, and is not kind. When I went there yesterday evening in the gloaming it had crept down and was trying to catch the little speckled fishes that play in the pool, and I had to clod it to make it go up the tree again and let them alone. I wonder if that is what it is for? Hasn’t it any heart? Hasn’t it any compassion for those little creatures? Can it be that it was designed and manufactured for such ungentle work? It has the look of it. One of the clods took it back of the ear, and it used language. It gave me a thrill, for it was the first time I had ever heard speech, except my own. I did not understand the words, but they seemed expressive.

When I found it could talk I felt a new interest in it, for I love to talk; I talk, all day, and in my sleep, too, and I am very interesting, but if I had another to talk to I could be twice as interesting, and would never stop, if desired. If this reptile is a man, it isn’t an it, is it? That wouldn’t be grammatical, would it? I think it would be he. I think so. In that case one would parse it thus: nominative, he; dative, him; possessive, his’n. Well, I will consider it a man and call it he until it turns out to be something else. This will be handier than having so many uncertainties.

Next week Sunday.—All the week I tagged around after him and tried to get acquainted. I had to do the talking, because he was shy, but I didn’t mind it. He seemed pleased to have me around, and I used the sociable “we” a good deal, because it seemed to flatter him to be included.

Wednesday.—We are getting along very well indeed, now, and getting better and better acquainted. He does not try to avoid me any more, which is a good sign, and shows that he likes to have me with him. That pleases me, and I study to be useful to him in every way I can, so as to increase his regard.

During the last day or two I have taken all the work of naming things off his hands, and this has been a great relief to him, for he has no gift in that line, and is evidently very grateful. He can’t think of a rational name to save him, but I do not let him see that I am aware of his defect. Whenever a new creature comes along I name it before he has time to expose himself by an awkward silence. In this way I have saved him many embarrassments. I have no defect like his. The minute I set eyes on an animal I know what it is. I don’t have to reflect a moment; the right name comes out instantly, just as if it were an inspiration, as no doubt it is, for I am sure it wasn’t in me half a minute before. I seem to know just by the shape of the creature and the way it acts what animal it is.

When the dodo came along he thought it was a wild-cat—I saw it in his eye. But I saved him. And I was careful not to do it in a way that could hurt his pride. I just spoke up in a quite natural way of pleased surprise, and not as if I was dreaming of conveying information, and said, “Well, I do declare, if there isn’t the dodo!” I explained—without seeming to be explaining—how I knew it for a dodo, and although I thought maybe he was a little piqued that I knew the creature when he didn’t, it was quite evident that he admired me. That was very agreeable, and I thought of it more than once with gratification before I slept. How little a thing can make us happy when we feel that we have earned it.

Thursday.—My first sorrow. Yesterday he avoided me and seemed to wish I would not talk to him. I could not believe it, and thought there was some mistake, for I loved to be with him, and loved to hear him talk, and so how could it be that he could feel unkind towards me when I had not done anything? But at last it seemed true, so I went away and sat lonely in the place where I first saw him the morning that we were made and I did not know what he was and was indifferent about him; but now it was a mournful place, and every little thing spoke of him, and my heart was very sore. I did not know why very clearly, for it was a new feeling; I had not experienced it before, and it was all a mystery, and I could not make it out. But when night came I could not bear the lonesomeness, and went to the new shelter which he has built, to ask him what I had done that was wrong and how I could mend it and get back his kindness again; but he put me out in the rain, and it was my first sorrow.

Sunday.—It is pleasant again, now, and I am happy; but those were heavy days; I do not think of them when I can help it. I tried to get him some of those apples, but I cannot learn to throw straight. I failed, but I think the good intention pleased him. They are forbidden, and he says I shall come to harm; but so I come to harm through pleasing him, why shall I care for that harm?

Monday.—This morning I told him my name, hoping it would interest him. But he did not care for it. It is strange. If he should tell me his name, I would care. I think it would be pleasanter in my ears than any other sound.

He talks very little. Perhaps it is because he is not bright, and is sensitive about it and wishes to conceal it. It is such a pity that he should feel so, for brightness is nothing; it is in the heart that the values lie. I wish I could make him understand that a loving good heart is riches, and riches enough, and that without it intellect is poverty. Although he talks so little he has quite a considerable vocabulary. This morning he used a surprisingly good word. He evidently recognized, himself, that it was a good one, for he worked it in twice afterwards, casually. It was not good casual art, still it showed that he possesses a certain quality of perception. Without a doubt that seed can be made to grow, if cultivated. Where did he get that word? I do not think I have ever used it. No, he took no interest in my name. I tried to hide my disappointment, but I suppose I did not succeed. I went away and sat on the moss-bank with my feet in the water. It is where I go when I hunger for companionship, some one to look at, some one to talk to. It is not enough—that lovely white body painted there in the pool—but it is something, and something is better than utter loneliness. It talks when I talk; it is sad when I am sad; it comforts me with its sympathy; it says, “Do not be downhearted, you poor friendless girl; I will be your friend.” It is a good friend to me, and my only one; it is my sister.

That first time that she forsook me! ah, I shall never forget that—never, never. My heart was lead in my body! I said, “She was all I had, and now she is gone!” In my despair I said, “Break, my heart; I cannot bear my life any more!” and hid my face in my hands, and there was no solace for me. And when I took them away, after a little, there she was again, white and shining and beautiful, and I sprang into her arms!

That was perfect happiness; I had known happiness before, but it was not like this, which was ecstasy. I never doubted her afterwards. Sometimes she stayed away—maybe an hour, maybe almost the whole day, but I waited and did not doubt; I said, “She is busy, or she is gone a journey, but she will come.” And it was so: she always did. At night she would not come if it was dark, for she was a timid little thing; but if there was a moon she would come. I am not afraid of the dark, but she is younger than I am; she was born after I was. Many and many are the visits I have paid her; she is my comfort and my refuge when my life is hard—and it is mainly that.

Tuesday.—All the morning I was at work improving the estate; and I purposely kept away from him in the hope that he would get lonely and come. But he did not. At noon I stopped for the day and took my recreation by flitting all about with the bees and the butterflies and revelling in the flowers, those beautiful creatures that catch the smile of God out of the sky and preserve it! I gathered them, and made them into wreaths and garlands and clothed myself in them while I ate my luncheon—apples, of course; then I sat in the shade and wished and waited. But he did not come.

But no matter. Nothing would have come of it, for he does not care for flowers. He calls them rubbish, and cannot tell one from another, and thinks it is superior to feel like that. He does not care for me, he does not care for flowers, he does not care for the painted sky at eventide—is there anything he does care for, except building shacks to coop himself up in from the good clean rain, and thumping the melons, and sampling the grapes, and fingering the fruit on the trees, to see how those properties are coming along?

I laid a dry stick on the ground and tried to bore a hole in it with another one, in order to carry out a scheme that I had, and soon I got an awful fright. A thin, transparent bluish film rose out of the hole, and I dropped everything and ran! I thought it was a spirit, and I was so frightened! But I looked back, and it was not coming; so I leaned against a rock and rested and panted, and let my limbs go on trembling until they got steady again; then I crept warily back, alert, watching, and ready to fly if there was occasion; and when I was come near, I parted the branches of a rose-bush and peeped through—wishing the man was about, I was looking so cunning and pretty—but the sprite was gone. I went there, and there was a pinch of delicate pink dust in the hole. I put my finger in, to feel it, and said ouch! and took it out again. It was a cruel pain. I put my finger in my mouth; and by standing first on one foot and then the other, and grunting, I presently eased my misery; then I was full of interest, and began to examine. I was curious to know what the pink dust was. Suddenly the name of it occurred to me, though I had never heard of it before. It was fire! I was as certain of it as a person could be of anything in the world. So without hesitation I named it that—fire. I had created something that didn’t exist before; I had added a new thing to the world’s uncountable properties; I realized this, and was proud of my achievement, and was going to run and find him and tell him about it, thinking to raise myself in his esteem—but I reflected, and did not do it. No—he would not care for it. He would ask what it was good for, and what could I answer? for if it was not good for something, but only beautiful, merely beautiful—So I sighed, and did not go. For it wasn’t good for anything; it could not build a shack, it could not improve melons, it could not hurry a fruit crop; it was useless, it was a foolishness and a vanity; he would despise it and say cutting words. But to me it was not despicable; I said, “Oh, you fire, I love you, you dainty pink creature, for you are beautiful—and that is enough!” and was going to gather it to my breast. But refrained. Then I made another maxim out of my own head, though it was so nearly like the first one that I was afraid it was only a plagiarism: “The burnt Experiment shuns the fire.”

I wrought again; and when I had made a good deal of fire-dust I emptied it into a handful of dry brown grass, intending to carry it home and keep it always and play with it; but the wind struck it and it sprayed up and spat out at me fiercely, and I dropped it and ran. When I looked back the blue spirit was towering up and stretching and rolling away like a cloud, and instantly I thought of the name of it—smoke!—though, upon my word, I had never heard of smoke before. Soon, brilliant yellow-and-red flares shot up through the smoke, and I named them in an instant—flames!—and I was right, too, though these were the very first flames that had ever been in the world. They climbed the trees, they flashed splendidly in and out of the vast and increasing volume of tumbling smoke, and I had to clap my hands and laugh and dance in my rapture, it was so new and strange and so wonderful and so beautiful! He came running, and stopped and gazed, and said not a word for many minutes. Then he asked what it was. Ah, it was too bad that he should ask such a direct question. I had to answer it, of course, and I did. I said it was fire. If it annoyed him that I should know and he must ask, that was not my fault; I had no desire to annoy him. After a pause he asked:

“How did it come?” Another direct question, and it also had to have a direct answer.

“I made it.”

The fire was travelling farther and farther off. He went to the edge of the burned place and stood looking down, and said:.

“What are these?”

“Fire-coals.”

He picked up one to examine it, but changed his mind and put it down again. Then he went away. Nothing interests him.

But I was interested. There were ashes, gray and soft and delicate and pretty—I knew what they were at once. And the embers; I knew the embers, too. I found my apples, and raked them out, and was glad; for I am very young and my appetite is active. But I was disappointed; they were all burst open and spoiled. Spoiled apparently; but it was not so; they were better than raw ones. Fire is beautiful; some day it will be useful, I think

Friday.—I saw him again, for a moment, last Monday at nightfall, but only for a moment. I was hoping he would praise me for trying to improve the estate, for I had meant well and had worked hard. But he was not pleased, and turned away and left me. He was also displeased on another account: I tried once more to persuade him to stop going over the Falls. That was because the fire had revealed to me a new passion—quite new, and distinctly different from love, grief, and those others which I had already discovered—fear. And it is horrible!—I wish I had never discovered it; it gives me dark moments, it spoils my happiness, it makes me shiver and tremble and shudder. But I could not persuade him, for he has not discovered fear yet, and so he could not understand me.

.jpg)

Mark Twain short stories

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Twain, Mark

.jpg)

Ton van Reen

EZELS ZIJN VERACHTELIJKE DIEREN

Ezels zijn verachtelijke dieren

als ze worden geslagen

huilen ze als vrouwen die worden geslagen

als ze bijna sterven van dorst

krijsen ze als verongelijkte kinderen

Ezels zijn het uitschot van de dieren

als ze oud zijn en overbodig

en de mensen hen laten creperen

stellen ze zich aan als mensen en vragen ze aandacht

Dienstbaarheid is hun lot

daarom is het belachelijk

hoe luid ezels om dankbaarheid vragen

ze vergeten dat ze slaven zijn

die zijn geschapen door de duivel

en daarom alleen verachting verdienen

Omdat ezels zo achterlijk zijn

blijven ze luid om aandacht vragen

vroeg in de ochtend hoor je ze tekeergaan

ver weg, vastgebonden in droog land

ezels willen maar niet begrijpen

dat ze levende wezens zijn zonder ziel

en het daarom verdienen te creperen

Ton van Reen: De naam van het mes. Afrikaanse gedichten

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -De naam van het mes, Ton van Reen

.jpg)

Hank Denmore

Moord in lichtdruk

tweeënveertig

De gangsterboss Vincente werd met zijn bende, die nu nog uit Antonio, Lime en Rope bestond, nog dezelfde dag gearresteerd. Maar bij het hoofdbureau aangekomen bleken alle cellen al in gebruik te zijn. Noodgedwongen werd uitgeweken naar een wijkbureau in Lower East. De vier werden voorlopig in één cel opgesloten. Het cellenblok bestond uit een vrij lange gang met aan een zijde de cellen. Die bestonden uit drie traliewanden en een buitenmuur van zware dubbelgebakken klinkers, waarop elk mes bij een poging om in de steen te kerven in de kortste keren bot werd. In elke cel waren betonnen britsen tegen de buitenmuur en de traliewanden aangebracht. Na het nuttigen van een sober middagmaal, bestaande uit uiensoep, aardappelen met een schijf van een of andere onbekende vleessoort met lawaaisaus en melige pudding, zaten ze aangeslagen te wachten op de dingen die kwamen. Na enkele uren, die erg traag en zwijgend verliepen, ging de deur naar het bureau open en tot hun grote verbazing zagen ze Tino Vandezzi die, geflankeerd door twee geüniformeerde agenten, binnen werd gebracht. Zwijgend volgden ze Tino, die tot hun nog grotere verbazing bij hen in de toch al volle cel werd ingesloten.

‘Jullie kennen elkaar toch, veel plezier.’, was het commentaar van een van de agenten.

Tino keek, bijna onmerkbaar nee schuddend, naar Vincente. Die begreep niet goed wat Tino daarmee bedoelde maar hield wijselijk zijn mond dicht. Toen ze alleen waren stonden Vincente, Lime en Antonio eerbiedig op en lieten Tino kiezen op welke brits hij wilde gaan zitten. Tino knikte dat de anderen ook mochten gaan zitten en keek naar het grijnzende gezicht van Rope. ‘Wat heb jij te lachen, vind je het leuk om hier te zitten?’

‘Je maakt wel indruk op mijn boss, had ik ook moeten gaan staan?’

‘Dat weet je maar nooit, we zitten hier niet voor lang.’

Rope slikte even en ging zwijgend in een hoekje zitten.

De deur ging weer open en een agent kwam binnen met een karretje waarop een grote theekan en enkele kommen stonden. Eerst kregen in een paar cellen naast hen andere arrestanten een kom thee, toen reed de agent het karretje naar de nu overvolle cel.

‘Wie wil thee, met of zonder suiker? Je hebt het maar voor het kiezen. Wij verwennen onze gasten, maar wel zelf komen halen.’

Toen Rope bij de tralies kwam keek de agent hem aan: ‘Hier is uw thee, ik hoop dat hij smaakt.’

Tino keek vreemd naar Rope, die zag dat en haalde zijn schouders op: ‘Ik weet niet waarom die vent zo tegen me praat. Ik heb hem nog nooit gezien.’

De agent verdween weer met de theekar en iedereen dronk min of meer hoorbaar zijn thee op. Na een minuut of tien ging de deur weer open, er kwam een andere agent met de nu lege theekar. Bij elke cel haalde hij de kommen op.

Toen hij bij de cel van Tino en aanhang kwam, keek hij zoekend rond totdat hij Rope zag. Hij keek te onopvallend naar Rope die zich geërgerd van de agent afkeerde.

Maar alles was door Lime gezien en dat liet deze merken: ‘Hé, kennen jullie elkaar?’

‘Welnee, die kerel moet zich vergissen,’ zei Rope.

‘Maar dan moeten zich twéé agenten vergissen,’ sneerde Vincente.

Rope werd onrustig en mopperde: ‘Laat me toch, ik vind het hier ook niet leuk en zeker niet als jullie me gaan plagen.’

‘Plagen?’ zei Tino, ‘Maar dit is menens. Zeg op, ken jij die kerels, ja of nee? En als je ze kent wil ik nu weten waarvan je ze kent.’

‘Ik zweer dat ik die twee niet ken, misschien hebben ze me ooit eens een parkeerbon of zoiets gegeven. Maar nogmaals, ik ken ze niet.’

Plotseling sprong Antonio op: ‘Ik weet het, die ene agent, die achter het stuur zat, keek Rope aan en schreef toen iets in een notitieboekje op en sprak hem ook al met u aan.’

‘En wat zou dat, jij weet toch niet wat die toen opschreef? Misschien vond die mijn jas wel mooi en noteerde hij het merk.’

Langzaam zei Vincente : ‘Als die twee jou kennen en volgens mij is dat zo, kan dat alleen maar betekenen dat jij ook politieman bent. Wanneer ik ontdek dat iemand van mijn mensen een stille is heb ik daar maar één antwoord op, afmaken.’

Rope voelde zich in het nauw gedreven en schreeuwde: ‘Verrek zelf, weet je wel wie Tino in werkelijkheid is? Hij is hier het hoofd van de KGB’.

Tino riep tegen Lime en Antonio: ‘Pak die regeringsspion en werk hem tegen de vloer.’

.jpg)

Hank Denmore: Moord in lichtdruk

kempis.nl poetry magazine

(wordt vervolgd)

More in: -Moord in lichtdruk

.jpg)

Mikhail Yuryevich Lermontov

(Михаи́л Ю́рьевич Ле́рмонтов 1814 – 1841)

![]() The reed

The reed

A fisherman sat humming

Beside a stream one day

And watched the wind of morning

The reeds and grasses sway.

He cut a reed, and, making

A hole in it or two,

To one end held a finger

And in the other blew.

The reed to life was wakened,

It spoke up with a sigh.

Was’t voice of wind or maiden,

Its gentle voice and shy?

"0 fisherman," it begged him,

"Do not torment me so.

0 fisherman, I pray you,

Hear out my tale of woe.

"A fair and lovely maiden

But motherless I was.

I bloomed, but bloomed unwanted,

By no one loved, alas!

My father he remarried

And took a witch to wife.

I called on death to claim me

So wretched was my life.

"The witch she had a dearly

Beloved son, had she,

A worthless rogue and scapegrace

Who fooled young maids was he.

I went with him one evening

To walk beside the stream

And watch its waters mirror

The sun’s last dying gleam.

"My love in vain he begged forþ

Him and his pleas i spurned.

Gold coins to me he offeredþ

In ire from him I turned.

Then with his knife he struck me.

He struck me in the breast.

A grave he dug and put me

There on the bank to rest.

"And o’er my grave soon after

There grew a slender reed,

And in it live the sorrows

That made my young heart bleed.

0 fisherman, pray leave me,

Do not disturb my sleep.

Alack, you cannot help me

And have not learnt to weep!…"

.jpg)

Mikhail Lermontov poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive K-L

.jpg)

Freedom of Speech

Freedom of Speech

Oranienburgerstrasse

Potzdamerplatz

Kurfürstendamm

Kurfürstendamm

Nachrichten aus Berlin:

unser Korrespondent Anton K. berichtet

January 2011- fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Anton K. Photos & Observations, FDM in Berlin, Nachrichten aus Berlin

.jpg)

Joris-Karl Huysmans

(1849-1907)

Le Drageoir aux épices (1874)

XVIII. L’Emailleuse

Un beau matin, le poète Amilcar enfonça sur sa tête son chapeau noir, un chapeau célèbre, d’une hauteur prodigieuse, d’une envergure insolite, plein de plats et de méplats, de rides et de bosses, de crevasses et de meurtrissures, mit dans une poche, sise au-dessous de sa mamelle gauche, une pipe en terre à long col et s’achemina vers le nouveau domicile qu’avait choisi un sien ami, le peintre José.

Il le trouva couché sur un éboulement de coussins, l’oeil morne, la figure blafarde.

—Tu es malade, lui dit-il.

—Non.

—Tu vas bien alors?

—Non.

—Tu es amoureux

—Oui.

—Patatras! et de qui? bon Dieu!

—D’une Chinoise.

—D’une Chinoise? tu es amoureux d’une Chinoise!

—Je suis amoureux d’une Chinoise.

Amilcar s’affaissa sur l’unique chaise qui meublait la chambre.

—Mais enfin, clama-t-il lorsqu’il fut revenu de sa stupeur, où l’as-tu rencontrée, cette Chinoise?

—Ici, à deux pas, là, derrière ce mur. Ecoute, je l’ai suivie un soir, j’ai su qu’elle demeurait ici avec son père, j’ai loué la chambre contiguë à la sienne, je lui ai écrit une lettre à laquelle elle n’a pas encore répondu, mais j’ai appris par la concierge son nom: elle s’appelle Ophélie. Oh! si tu savais comme elle est belle, cria-t-il en se levant; un teint d’orange mûrie, une bouche aussi rose que la chair des pastèques, des yeux noirs comme du jayet!

Amilcar lui serra la main d’un air désolé et s’en fut annoncer a ses amis que José était devenu fou.

A peine eut-il franchi la porte, que celui-ci fit dans la muraille un petit trou avec une vrille et se mit aux aguets, espérant bien voir sa douce déité. Il était huit heures du matin, rien ne bougeait dans la chambre voisine; il commençait à se désespérer quand un bâillement se fit entendre, un bruit retentit, le bruit d’un corps sautant a terre, et une jeune fille parut dans le cercle que son oeil pouvait embrasser. Il reçut un grand coup dans l’estomac et manqua défaillir. C’était elle et ce n’était pas elle; c’était une Française qui ressemblait, autant que peut ressembler une Française à une Chinoise, à la fille jaune dont le regard l’avait bouleversé. Et pourtant c’était bien le même oeil câlin et profond, mais la peau était terne et pâle, le rouge de la bouche s’était amorti; enfin, c’était une Européenne! Il descendit l’escalier précipitamment. «Ophélie a donc une soeur? dit-il à la concierge. —Non. —Mais elle n’est pas Chinoise alors? —La concierge éclata de rire. «Comment, pas Chinoise! ah çà! est-ce que j’ai une figure comme elle, moi qui ne suis pas née en Chine?» poursuivit le vieux monstre en mirant sa peau ridée dans un miroir trouble. José restait debout, effaré, stupide, quand une voix forte fit tressaillir les carreaux de la loge. «Mlle Ophélie est là?» José se retourna et vit en face de lui, non une figure de vieux reître, comme semblait l’indiquer la voix, mais celle d’une vieille femme, gonflée comme une outre, le nez chevauché par d’énormes besicles, la bouche dessinant dans la bouffissure des chairs de capricieux zigzags. Sur la réponse affirmative de la portière, cette femme monta, et José s’aperçut qu’elle tenait à la main une boîte en toile cirée. Il s’élança sur ses pas, mais la porte se referma sur elle; alors il se précipita dans sa chambre et colla son oeil contre le trou qu’il avait percé dans la cloison.

Ophélie s’assit, lui tournant le dos, devant une grande glace, et la femme, s’étant débarrassée de son tartan, ouvrit sa valise et en tira un grand nombre de petites boites d’estompes et de brosses. Puis, soulevant la tête d’Ophélie comme si elle la voulait raser, elle étendit avec un petit pinceau une pâte d’un jaune rosé sur la figure de la jeune fille, brossa doucement la peau, pétrit un petit morceau de cire devant le feu, rectifia le nez, assortissant la teinte avec celle de la figure, soudant avec un blanc laiteux le morceau artificiel du nez avec la chair du véritable; enfin elle prit ses estompes, les frotta sur la poudre des boites, étendit une légère couche de bleu pâle sous l’oeil noir qui se creusa et s’allongea vers les tempes. La toilette terminée, elle se recula à distance pour mieux juger de l’effet, dodelina la tête, revint vers son pastel qu’elle retoucha, resserra ses outils et, après avoir pressé la main d’Ophélie sortit en reniflant.

José était inerte, les bras lui en étaient tombés. Eh quoi! c’était un tableau qu’il avait aimé, un déguisement de bal masqué! Il finit cependant par reprendre ses sens et courut à la recherche de l’émailleuse. Elle était déjà au bout de la rue; il bouscula tout le monde, courut à travers les voitures et la rejoignit enfin. «Que signifie tout cela? cria-t-il; qui êtes-vous? pourquoi la transfigurez-vous en Chinoise? —Je suis émailleuse, mon cher Monsieur; voici ma carte; toute à votre service si vous avez besoin de moi. —Eh! il s’agit bien de votre carte! cria le peintre tout haletant; je vous en prie, expliquez-moi le motif de cette comédie.

—Oh! pour ça, si vous y tenez et si vous êtes assez honnête pour offrir à une pauvre vieille artiste un petit verre de ratafia, je vous dirai tout au long pourquoi, tous les matins, je viens peindre Ophélie.

—Allons, dit José, en la poussant dans un cabaret et en l’installant sur une chaise, dans un cabinet particulier, voici du ratafia, parlez.

—Je vous dirai tout d’abord, commença-t-elle, que je suis émailleuse fort habile; au reste, vous avez pu voir… Ah! çà mais, à propos, comment avez-vous vu? … —Peu importe, cela ne peut vous regarder, continuez. —Eh bien! je vous disais donc que j’étais une émailleuse fort habile et que si jamais vous… —Au fait! au fait! cria José furieux. —Ne vous emportez pas, voyons, là, vous savez bien que la colère… —Mais tu me fais bouillir, misérable! hurla le peintre qui se sentait de furieuses envies de l’étrangler, parleras-tu? —Ah! mais pardon, jeune homme, je ne sais pourquoi vous vous permettez de me tutoyer et de m’appeler misérable; je vous préviens tout d’abord que si… —Ah! mon Dieu, gémit le pauvre garçon en frappant du pied il y a de quoi devenir fou.

—Voyons, jeune homme, taisez-vous et je continue; surtout ne m’interrompez pas, ajouta-t-elle en dégustant son verre. Je vous disais donc… —Que vous étiez une émailleuse fort habile; oui, je le sais, j’ai votre carte; voyons, passons: pourquoi Ophélie se fait-elle peindre en Chinoise?

—Mon Dieu, que vous êtes impatient! Connaissez-vous l’homme qui habite avec elle? —Son père? —Non. D’abord, ce n’est pas son vrai père, mais bien son père adoptif. —C’est un Chinois? —Pas le moins du monde; il est Chinois comme vous et moi; mais il a vécu longtemps dans le Thibet et y a fait fortune. Cet homme, qui est un brave et honnête homme, je vous avouerai même qu’il ressemble un peu à mon défunt qui… —Oui, oui, vous me l’avez déjà dit. —Bah! dit la femme, en le regardant avec stupeur, je vous ai parlé d’Isidore? —De grâce, laissons Isidore dans sa tombe, buvez votre ratafia et continuez. —Tiens, c’est drôle! il me semble pourtant que… Enfin, peu importe, je vous disais donc que c’était un brave et digne homme. Il se maria là-bas avec une Chinoise qui l’a planté là au bout d’un mois de mariage. Il faillit devenir fou, car il aimait sa femme, et ses amis durent le faire revenir en France au plus vite. Il se rétablit peu à peu et, un soir, il a trouvé dans la rue, défaillante de froid et de faim, prête à se livrer pour un morceau de pain, une jeune fille dont les yeux avaient la même expression que ceux de sa femme. Elle lui ressemblait même comme grandeur et comme taille; c’est alors qu’il lui a proposé de lui laisser toute sa fortune si elle consentait à se laisser peindre tous les matins. Il est venu me trouver, et chaque jour, à huit heures, je la déguise; il arrive à dix heures et déjeune avec elle. Jamais plus, depuis le jour où il l’a recueillie, il ne l’a vue telle qu’elle est réellement. Voilà; maintenant, je me sauve, car j’ai de l’ouvrage. Bonsoir, Monsieur.

Il resta abruti, inerte, sentant ses idées lui échapper. Il rentra chez lui dans un état à faire pitié.

Amilcar arriva sur ces entrefaites, suivi d’un de ses amis qui était médecin. Ils eurent toutes les peines du monde à faire sortir de sa torpeur le malheureux José, qui ne parlait rien moins que de s’aller jeter dans la Seine.

—Ce n’est, ma foi! pas la peine de se noyer pour si peu, dit derrière eux une petite voix aigrelette; je suis Ophélie, mon gros père, et ne suis point si cruelle que je vous laisse mourir d’amour pour moi. Profitons, si vous voulez, de l’absence du vieux, pour aller visiter les magasins de soieries. J’ai justement envie d’une robe; je vous autoriserai à me l’offrir. —Oh! non, cria le peintre, profondément révolté par cette espèce de marché, je suis guéri à tout jamais de mon amour.

Entendre de telles paroles sortir de la bouche de sa bien-aimée ou recevoir sur la tête une douche d’eau froide, l’effet est le même, observa le poète Amilcar, qui dégringola les escaliers et, chemin faisant, rima immédiatement un sonnet qu’il envoya le lendemain à la belle enfant, sous ce titre quelque peu satirique:

O Fleur de nénuphar!

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Le Drageoir aux épices, Archive G-H, Huysmans, J.-K.

![]()

Braco Dimitrijevic’

Braco Dimitrijevic, one of the pioneers of conceptual art, had his first one-man exhibition at the age of 10. In 1963 he made his first conceptual work, The Flag of the World, in which he replaced a national flag with an alternative sign. It marked the beginning of his artistic interventions into urban landscapes.

Over the past forty years he has exhibited extensively all over the world. His solo shows have included venues such as Tate Gallery and ICA in London, Kunsthalle Bern, Museum Ludwig in Cologne, Kunsthalle Dusseldorf, MUMOK in Vienna, Russian State Museum in St. Petersburg, Xin-Dong Cheng Space for Contemporary Art in Beijing and Musee d’Orsay in Paris.

He has participated in major group shows such as the Kassel Documenta 5. Documenta 6, Documenta 9, several times at the Venice Biennale, Sao Paulo Biennale, Sydney Biennale, as well as Santa Fe Biennale, Havana Biennale, Kwangju Biennale. He also took part in the exhibition Magiciens de la Terre at the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris.

Dimitrijevic gained an international reputation in the seventies with his Casual passer-by series, in which gigantic photo portraits of anonymous people were displayed on prominent facades and billboards in European and American cities. The artist also mimicked other ways of glorifying important persons by building monuments to passers-by and installing memorial plaques in honour of anonymous citizens.

In the mid-seventies he started incorporating in his installations original paintings borrowed from museum collections. The Triptychos Post Historicus, realized in numerous museums around the world, unite in a harmonious synthesis high art, everyday objects, and fruit. The artist’s statement “Louvre is my studio, street is my museum” expresses both the dialectical and transgressive nature of his oeuvre. In the last thirty years, Dimitrijevic has realized over 500 Triptychos Post Historicus, with paintings ranging from Leonardo’s Madonna to Malevich’s Red Square, in numerous museum collections including the Tate Gallery, London, the Louvre, the Musee National d’Art Moderne Paris, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum New York, the Musee d’Orsay, and the Russian State Museum, St Petersburg, amongst many others.

In the early 1980s, Braco Dimitrijevic started making installations in which wild animals confront artifacts and works of art, thus joining two cultural models, the occidental model and the model offered by other cultures that live in greater harmony with nature. In 1998, the artist realized one-man shows at Paris Zoo with installations in the cages of lions, tigers, crocodiles, camels and bisons.

The exhibition was seen by one million people. It was reviewed by the international press of some 40 countries and received repeated CNN Television coverage.

Braco Dimitrijevic’s work, as well as his theoretical book Tractatus Post Historicus, (1976) were an important influence on two tendencies that dominate artistic discourse today: critical practices in public space and interventions in museum collections.

BRACO DIMITRIJEVIC was born in Sarajevo in 1948. He had his first one man show in 1958 at the age of 10. From 1968 to 1971 studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Zagreb (MA).

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Art Criticism, FDM Art Gallery

.jpg)

Hank Denmore

Moord in lichtdruk

eenenveeertig

Na een rustige rit kwamen Otto en Tom bij het hospitaal in Harrisburg aan. Ondanks het grote parkeerterrein had Tom toch moeite met het vinden van een plaatsje. Maar na enkele rondjes kwam er toch een vak vrij. Bij de receptie werd hun het kamernummer van Ebson Simmons gegeven.

Tussen het andere bezoek in liepen ze naar Simmons, die nog geen bezoek had. Ze stelden zich voor als medewerkers van Evelyne Steinbruch, of hij zich die nog herinnerde?

‘Was dat die dame met blond haar?’

‘Ja, dat is ze.’

Na de gebruikelijke vragen over hoe het met hem en zijn pols ging zei Otto: ‘We hebben enkele foto’s bij ons en willen dat u die bekijkt.’ Tom stond aan het voeteinde van het bed en keek naar het gezicht van Ebson Simmons. Toen Otto de foto’s van de genodigden bij de begrafenis liet zien reageerde hij niet. Toen hij echter de foto van Maureen Mc.Ferrit liet zien hield Ebson zijn adem in en keek snel naar de eerder getoonde foto’s.

Te haastig zei hij: ‘Die dame heb ik nooit gezien, trouwens de rest ook niet.’

‘Heb je Margo nog nooit gezien?’, vroeg Otto.

‘Nee, die Margo heb ik nog nooit gezien. Ik zou niet weten waar ik haar ontmoet zou moeten hebben.’

Na nog wat over het weer en het verkeer te hebben gepraat gingen de twee weer.

Bij het verlaten van de kamer wenkte de oude man Otto. Die liep naar het bed van het oudje en vroeg wat hij kon doen.

‘Laat mij die foto’s eens zien. Ik krijg weinig bezoek en heb dus de tijd om het bezoek van de andere patiënten op te nemen. Dat ik oud ben wil nog niet zeggen dat ik kinds ben. Mijn geheugen is nog goed.’

Hoopvol liet Otto de foto’s zien. Toen de oude man de foto van Maureen zag knikte hij en zei: ‘Die is hier geweest. Het gesprek was nogal spannend want Simmons heeft daarna koorts gekregen en mocht voorlopig geen bezoek hebben. Dat moet met dat meisje te maken hebben gehad. Het was een kordate dame, mooi gekleed in blauw en niet op haar mondje gevallen. Wat ze bespraken heb ik niet kunnen horen maar zij was aan het woord en hij moest luisteren. Vlak voor ze weer ging gaf ze aan Simmons een dikke enveloppe, toen ze weg was heeft hij die in zijn kastje verborgen.’

Omdat de oude man in een hoek van de kamer lag en Tom en Otto tussen de oude man en Simmons in stonden, kon deze niets zien of horen van wat er zich bij het bed van het oudje afspeelde.

‘Nou meneer, we zullen de groeten doen aan uw vrouw en beterschap.’ zei Otto tegen de oude man en ging richting deur, de oude man verbaasd kijkend achterlatend.

Simmons haalde opgelucht adem, gelukkig scheen die oude vent die twee ergens anders van te kennen. Gerustgesteld pakte hij een leesboek en wilde net gaan lezen toen Otto hem toeriep: ‘Je moet nog de groeten van Maureen hebben.’

‘Doe ze de groeten terug.’ zei Simmons, waarop Otto met een grijns de deur sloot.

Evelyne luisterde naar het relaas van de twee en knikte instemmend toe Otto vertelde van de groeten doen.

‘Hij kent Maureen en Sperry moet daar veel mee te maken hebben. Ik denk toch dat Simmons meer afweet van dat plotterpapier. Maar dat hij aan geheime gegevens heeft kunnen komen betwijfel ik. Daarvoor zijn de toegangcodes te omvangrijk en te ingewikkeld.’

‘Kunnen we Greener niet op zijn spoor zetten?’

‘Nee Otto, die heeft daar niets te zoeken, maar we kunnen hem wel vertellen dat Simmons bezoek van de blauwe dame heeft gehad.’

‘En dat dus de Russen erbij betrokken zullen zijn.’, zei Tom snel.

‘Ja dat zou kunnen, maar dan moet Simmons bij Sperry Rand wél iets van waarde hebben meegenomen.’, zei Evelyne. Op dat moment ging de telefoon.

Evelyne luisterde even en zei: ‘Oké Sidney, we komen onmiddellijk met ons drieën naar je toe.’ Ze draaide zich naar Tom en Otto: ‘Dat was inspecteur Greener, hij heeft meer gevonden over die pistolen van Tino Vandezzi.’

De inspecteur wees de drie een stoel aan en ging zelf achter het boordevolle stalen bureau zitten. Zijn assistent Thomas Brisbane zat in een hoek van de kamer en zwaaide als groet met zijn hand.

‘Evelyne, Tino Vandezzi heeft een grote fout gemaakt. De Russische pistolen die hij in bezit heeft worden alleen door de Russische regeringsdiensten gebruikt. Het zijn geen legerwapens en ze zijn ook particulier niet te koop, daarom staan er ook geen serienummers op. Burgers die betrapt worden op het bezit van zo’n pistool worden naar Siberië gestuurd. We kunnen dus wel aannemen dat Tino verbindingen heeft met de KGB of een andere Russische dienst. We hebben echter geen spoor van bewijs van die aanname kunnen vinden.’

Thomas kwam uit zijn stoel overeind: ‘Die Tino heeft een vreemde macht over Garcioli, dat ben ik van een exgevangene te weten gekomen. Maar het zijn geen vrienden, want tijdens de twee jaren die Garcioli in eenzame opsluiting doorbracht, heeft hij nooit bezoek of zelfs maar een briefkaartje van Tino gekregen. Nu ik dat verhaal van die pistolen hoor weet ik bijna zeker dat Tino van de Russische geheime dienst is en ook Garcioli heeft daar erg veel mee te maken.’

Greener knikte instemmend: ‘Ik denk dat we dat stelletje maar eens gaan ophalen. We kunnen het gooien op ongeoorloofd bezit van wapens.’

‘Maar hij had toch een invoervergunning?’, merkte Thomas op.

‘Ja, dat wel, maar we kunnen niemand vinden die deze vergunning heeft geschreven. Bovendien is daar dat verouderde stempel. Ik heb dat laten navragen bij alle douanekantoren, maar dat stempel wordt sinds het gebruik van een nieuw logo al enkele jaren niet meer gebruikt.

.jpg)

Hank Denmore: Moord in lichtdruk

kempis.nl poetry magazine

(wordt vervolgd)

More in: -Moord in lichtdruk

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature