Fleurs du Mal Magazine

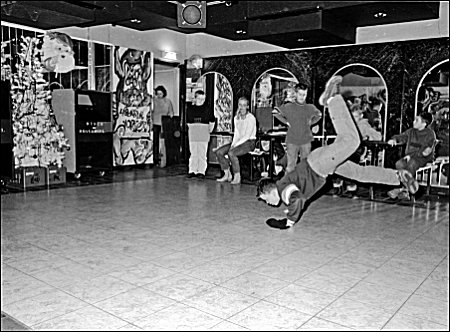

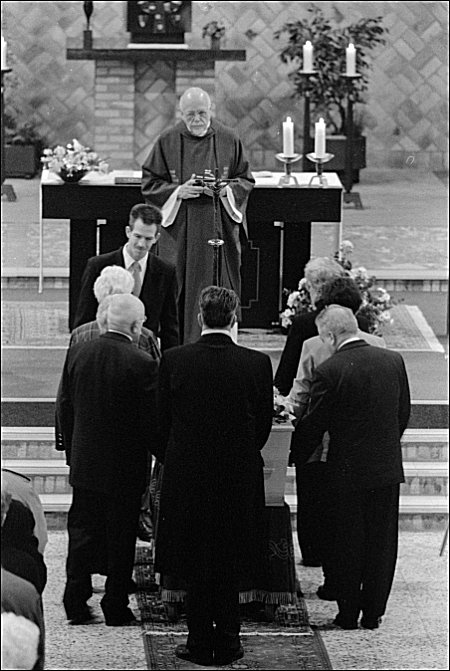

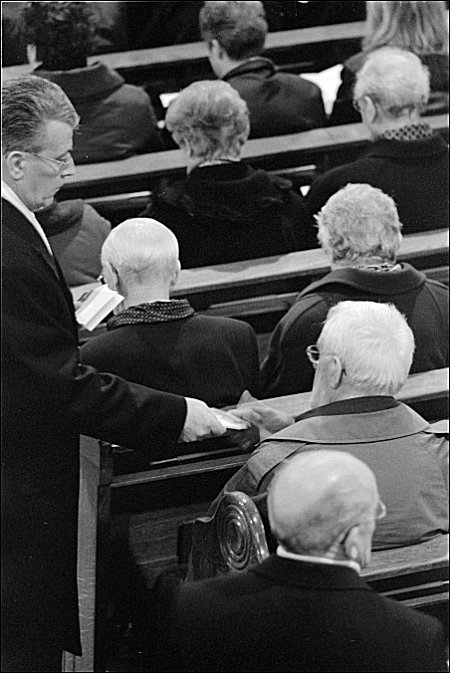

Kunstakademie Düsseldorf

RUNDGANG 2009

Die Geschichte der Kunstakademie Düsseldorf

Die Düsseldorfer Akademie wurde 1773 durch den Kurfürsten Carl Theodor als Kurfürstlich Pfälzische Akademie der Maler-, Bildhauer- und Baukunst gegründet. Im Jahr 1819 wurde sie in den Rheinprovinzen Preußens Königliche Kunstakademie. Heute ist sie Körperschaft des öffentlichen Rechts und zugleich Einrichtung des Landes Nordrhein-Westfalen.

Die Düsseldorfer Akademie ist eine Hochschule der Kunst und der Künstler. Diese Bestimmung ist in der Grundordnung vom 30.06.2008 festgelegt, die ältere Akademieverfassungen aus den Jahren 1777 und 1831 fortführt. Ergänzt wird die künstlerische Bestimmung durch die Pflege und Entwicklung der kunstbezogenen Wissenschaften.

Die künstlerische Betätigung geschieht im Sinne einer freien Kunst. Außer Malerei, Bildhauerei und freier Graphik schließt dies auch die Baukunst, das Bühnenbild, die Photographie sowie Film und Video ein. Dabei setzt die Kunstakademie auf künstlerische Qualität, Vielfalt und Internationalität.

Seit vielen Jahrzehnten ist dieses Konzept sehr erfolgreich. Die Akademie als Hochschule, aber auch ihre Künstler (Professoren und Absolventen) genießen hohes nationales und internationales Ansehen. Bereits im 19. Jahrhundert (“Düsseldorfer Malerschule”) waren viele der berühmtesten Künstler Deutschlands Düsseldorfer Absolventen. Seit den fünfziger Jahren behauptet die Kunstakademie eine ähnlich bedeutende Stellung für die Kunst der Gegenwart. Dies äußert sich etwa durch maßgebliche Beteiligungen an internationalen Ausstellungen (z.B. der Biennale Venedig). Heute befindet sich in Düsseldorf die “Kunstakademie der fünf Kontinente” mit Lehrern und Schülern aus aller Welt. Die Künstler der Akademie repräsentieren die internationale Kunstszene, viele zählen zu ihren bekanntesten Protagonisten.

Rektoren

1819 – 1824 Peter von Cornelius

1826 – 1859 Wilhelm von Schadow

1924 – 1933 Walter Kaesbach

1945 – 1946 Ewald Mataré

1959 – 1965 Hans Schwippert

1972 – 1981 Norbert Kricke

seit 1988 Markus Lüpertz

Einige Studenten und Professoren von 1819 bis heute: Andreas Achenbach – Adolf Seel – Oswald Achenbach – Peter Angermann – Glenn Bautista – Bernd Becher – Joseph Beuys – Arnold Böcklin – Christoph Büchel – Maria Buras – Michael Buthe – Max Clarenbach – Tony Cragg – Siegfried Cremer – Rolf Krummenauer – Felix Droese – Alfred Eckhardt – John Whetton Ehninger – Helmut Federle – Anselm Feuerbach – Rupprecht Geiger – Eugen Gomringer – Günter Grass – Gotthard Graubner – Andreas Gursky – Erwin Heerich – Shadrack Hlalele – Hans Schwippert – Hans Hollein – Ottmar Hörl – Candida Höfer – Johannes Hüppi – Axel Hütte – Oliver Jordan – Jörg Immendorff – Karin Kneffel – Paul Klee – Imi Knoebel – Heinrich Christoph Kolbe – Attila Kotányi – Walter Köngeter – Dieter Krieg – Rainer Maria Latzke – Rita McBride – Orlando Mohorovic – Yoshitomo Nara – Heinrich Nauen – Albert Oehlen – Markus Oehlen – Nam June Paik – Blinky Palermo – Sigmar Polke – Lois Renner – Gerhard Richter – Klaus Rinke – Reiner Ruthenbeck – Thomas Ruff – Rolf Sackenheim – Kaspar Scheuren – Felix Schramm – Rudolf Schwarz – Thomas Schütte – Dirk Skreber – Thomas Struth – Norbert Tadeusz – Rosemarie Trockel – Günther Uecker – Oswald Mathias Ungers – Georg Wilhelm Volkhart – Max Volkhart – Karl Ferdinand Wimar

Kunstakademie Düsseldorf

RUNDGANG 11-15 FEBRUAR 2009

Erster Teil

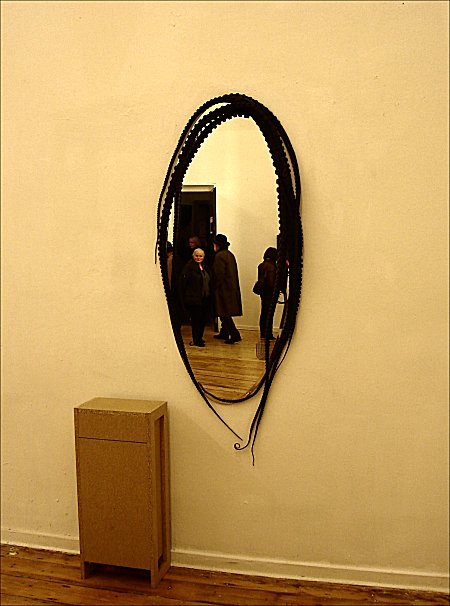

photos: anton & joseph K.

fleursdumal.nl magazine – magazine for art & literature

to be continued

More in: FDM Art Gallery, Galerie Deutschland

![]()

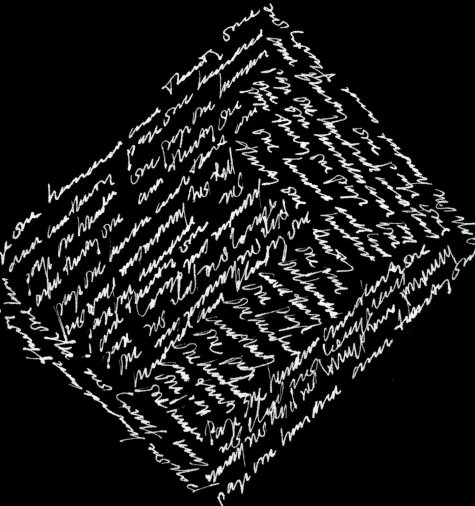

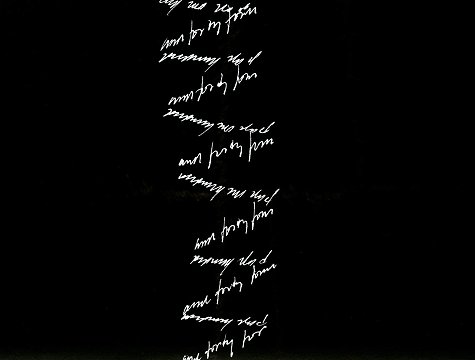

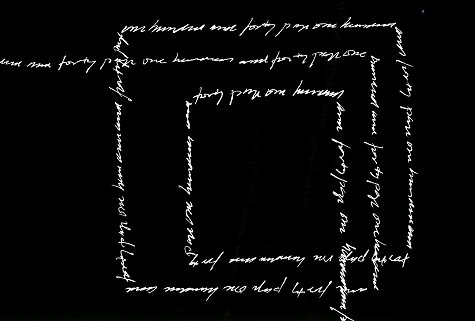

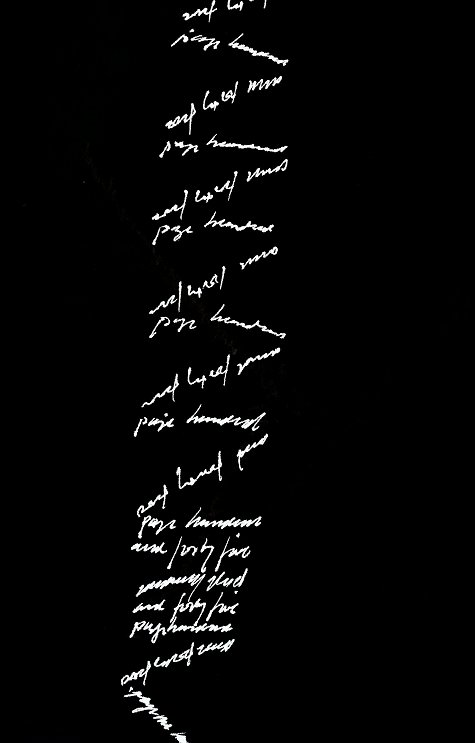

Museum of Lost Concepts

Disclosure 21-25 (1968-2008)

© Monica Richter

kemp=mag poetry magazine

More in: *Concrete + Visual Poetry P-T, Conceptual writing, FLUXUS LEGACY, Monica Richter, Richter, Monica, Visual & Concrete Poetry

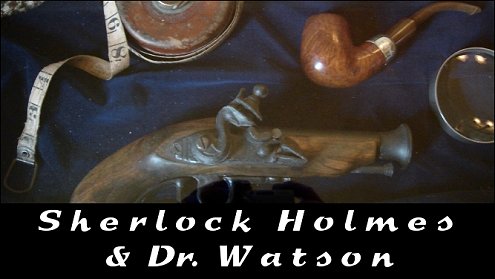

Museum of Literary Treasures

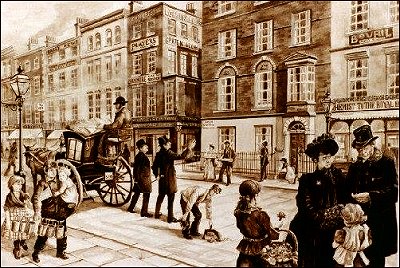

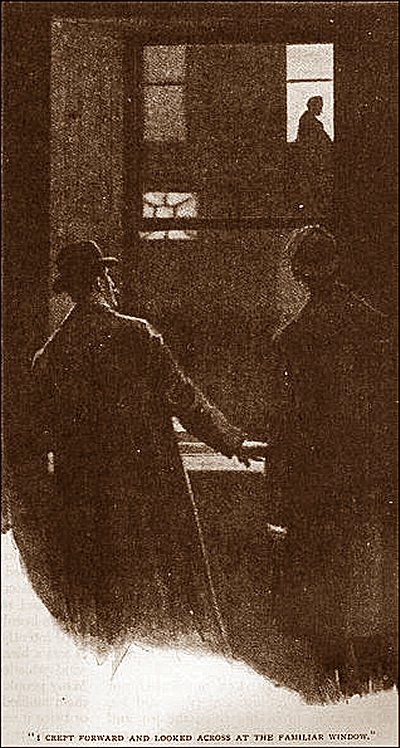

SHERLOCK HOLMES part I

The Sherlock Holmes Pub

Northumberland Street – LONDON

The Sherlock Holmes Museum

Bakerstreet – LONDON

photos: jefvankempen

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Arthur Conan Doyle, Museum of Literary Treasures, Sherlock Holmes Theatre

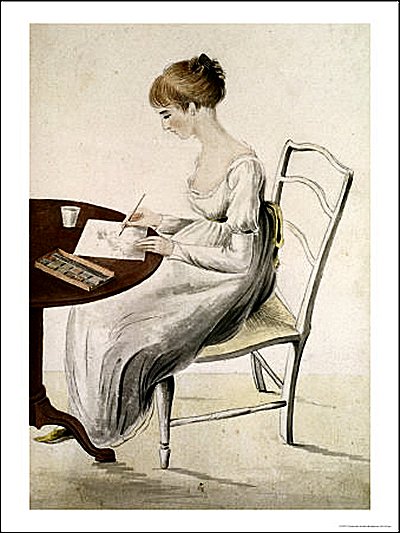

J a n e A u s t e n

(1775 – 1817)

F O U R P O E M S

I’ve a pain in my head

‘I’ve a pain in my head’

Said the suffering Beckford;

To her Doctor so dread.

‘Oh! what shall I take for’t?’

Said this Doctor so dread

Whose name it was Newnham.

‘For this pain in your head

Ah! What can you do Ma’am?’

Said Miss Beckford, ‘Suppose

If you think there’s no risk,

I take a good Dose

Of calomel brisk.’–

‘What a praise worthy Notion.’

Replied Mr. Newnham.

‘You shall have such a potion

And so will I too Ma’am.

Happy the Lab’rer

Happy the lab’rer in his Sunday clothes!

In light-drab coat, smart waistcoat, well-darn’d hose,

Andhat upon his head, to church he goes;

As oft, with conscious pride, he downward throws

A glance upon the ample cabbage rose

That, stuck in button-hole, regales his nose,

He envies not the gayest London beaux.

In church he takes his seat among the rows,

Pays to the place the reverence he owes,

Likes best the prayers whose meaning least he knows,

Lists to the sermon in a softening doze,

And rouses joyous at the welcome close.

My dearest Frank

My dearest Frank, I wish you joy

Of Mary’s safety with a Boy,

Whose birth has given little pain

Compared with that of Mary Jane.–

May he a growing Blessing prove,

And well deserve his Parents’ Love!–

Endow’d with Art’s and Nature’s Good,

Thy Name possessing with thy Blood,

In him, in all his ways, may we

Another Francis WIlliam see!–

Thy infant days may he inherit,

THey warmth, nay insolence of spirit;–

We would not with one foult dispense

To weaken the resemblance.

May he revive thy Nursery sin,

Peeping as daringly within,

His curley Locks but just descried,

With ‘Bet, my be not come to bide.’–

Fearless of danger, braving pain,

And threaten’d very oft in vain,

Still may one Terror daunt his Soul,

One needful engine of Controul

Be found in this sublime array,

A neigbouring Donkey’s aweful Bray.

So may his equal faults as Child,

Produce Maturity as mild!

His saucy words and fiery ways

In early Childhood’s pettish days,

In Manhood, shew his Father’s mind

Like him, considerate and Kind;

All Gentleness to those around,

And anger only not to wound.

Then like his Father too, he must,

To his own former struggles just,

Feel his Deserts with honest Glow,

And all his self-improvement know.

A native fault may thus give birth

To the best blessing, conscious Worth.

As for ourselves we’re very well;

As unaffected prose will tell.–

Cassandra’s pen will paint our state,

The many comforts that await

Our Chawton home, how much we find

Already in it, to our mind;

And how convinced, that when complete

It will all other Houses beat

The ever have been made or mended,

With rooms concise, or rooms distended.

You’ll find us very snug next year,

Perhaps with Charles and Fanny near,

For now it often does delight us

To fancy them just over-right us.–

This little bag

This little bag I hope will prove

To be not vainly made–

For, if you should a needle want

It will afford you aid.

And as we are about to part

T’will serve another end,

For when you look upon the Bag

You’ll recollect your friend

Jane Austen: Four Poems

KEMP=MAG poetry magazine – magazine for art & literature

More in: Austen, Jane, Austen, Jane

.jpg)

![]()

Passie, lief en leed

de oudste poëzie van het Keltische Cornwall

![]()

door Lauran Toorians

Het hier volgende artikel bestaat uit twee delen. Het eerste en omvangrijkste deel wil de lezer vooral op een informatieve manier onderhouden over het begin van de onbekende literatuur in een inmiddels uitgestorven taal: het Middelcornisch. Cornisch is (was) de taal van het middeleeuwse Cornwall, het schiereiland dat het uiterste zuidwesten van Groot-Brittannië vormt, middelcornisch is daarvan de middeleeuwse variant. Het tweede deel (de appendices A en B) poogt op een onderhoudende manier te informeren. Het bevat achtergrondinformatie over de metriek in de nauw aan het Cornisch verwante talen, en over de spelling en uitspraak van de tekstfragmenten in het eerste deel.

Leven en dood van een taal

Dat ook talen een beperkte levensduur hebben, is een gegeven. Volgens voorzichtige schattingen ‘sterft’ gemiddeld eens per maand ergens ter wereld een taal. Meestal gebeurt dat in een ver en vreemd land en betreft het een taal waar wij, ‘geciviliseerde’ westerlingen, niets of nauwelijks iets van weten, maar soms gebeurt het ook vlak onder onze neus. Wat het betekent dat een taal ‘(uit)sterft’, is dat de laatste personen voor deze taal de eerste, als peuter geleerde, taal was, het leven laten. Dat dit nauwelijks een sluitende definitie is, zal duidelijk zijn en de vaststelling van de overlijdensdatum van een taal is dan ook een hachelijke zaak. Uiteraard is het na de verdwijning van de laatste zogenaamde ‘moedertaalsprekers’ (de Engelse term is native speakers) van een taal niet langer mogelijk uit de eerste hand kennis van de betreffende taal op te doen.

Voor taalkundigen is dit een ramp, want hele taalgroepen gaan op deze wijze verloren voor verder onderzoek, soms zelfs zonder ook maar een naam te hebben gekregen in de wetenschappelijke literatuur. Te denken valt daarbij aan de vele talen van (Papoea) Nieuw Guinea (meer dan 300 totaal verschillende talen!), of de inheemse talen van Australië en de beide Amerika’s. Zoals bij het uitsterven van dieren en planten de biodiversiteit op aarde vermindert, zo verdwijnt met elke taal een stuk van de culturele diversiteit en het intellectuele erfgoed van de mensheid. In taalkundig opzicht is van belang dat naarmate minder diverse talen onderzocht kunnen worden, het ook moeilijker wordt inzicht te verwerven over het fenomeen taal in het algemeen, en dat bovendien de relaties tussen talen onderling onduidelijker worden (blijven) naarmate meer talen buiten beeld blijven. Dat het meestal juist onbekende talen betreft die bovendien nooit zijn opgeschreven, maakt dit alles uiteraard nog problematischer.

In de alledaagse praktijk heeft het uitsterven van een taal nog heel andere consequenties. Met een taal sterft vaak ook een wereldbeeld, een levenswijze, en – in de meeste gevallen – een (orale) literatuur in de meest brede zin van het woord. De meest recente ‘taaldood’ die zich vrijwel ongemerkt in onze nabije omgeving voltrok, was die van het Manx, de Keltische taal van het eiland Man in de Ierse Zee. Toen in 1974 Ned Maddrell op 97-jarige leeftijd overleed, was hij al twaalf jaar de enige moedertaalspreker die deze taal nog in leven hield. In 1950 waren er nog tien moedertaalsprekers geweest, allen ongeveer van dezelfde generatie. Tien jaar later waren er nog maar twee, en vanaf 1962 was Ned Maddrell de enige. En dat heeft hij geweten ook! Weinig mensen zullen de ontwikkeling van de geluidsopname-techniek – van wasrol tot en met cassetterecorder – van zo nabij hebben meegemaakt als hij. Een echte schrijftraditie heeft het Manx nooit gekend, en vrijwel alles wat we aan Manx volksverhalen, liederen, spreekwoorden en dergelijke bezitten (en dat is bar weinig) komt dan ook uit het geheugen van Ned Maddrell en circa twintig van zijn generatiegenoten. Daarbuiten bestaat de hele ‘literatuur’ in het Manx uit niet veel meer dan een bijbelvertaling, een Book of Common Prayer en een catechismus.

Dat er blijkens een volkstelling in 1971 toch nog 284 Manx-sprekers waren, heeft twee oorzaken. Ten eerste is dat te verklaren uit het feit dat er een aantal mensen op het eiland zijn die de taal weliswaar als tweede taal, maar toch nog op jonge leeftijd leerden. In de tweede plaats bracht de nood waarin de taal verkeerde een aantal (vooral jongere) mensen op Man tot het inzicht dat dit deel van hun culturele erfgoed niet verloren mocht gaan. Zij leerden de taal en kregen de regering op het eiland zover het belang van de taal te erkennen en er faciliteiten voor te scheppen in bijvoorbeeld het onderwijs.

Andere ‘kleine’ talen in Europa staat wellicht eenzelfde lot te wachten en de vastlegging en beschrijving van wat er nog leeft, is hier dan ook beslist van net zo groot belang als voor alle andere bedreigde talen van de wereld. Hier beperken we ons tot een kort overzicht van de Keltische talen, die geen van allen een zekere toekomst tegemoet gaan. Zo lijkt het Schots-Gaelic (in Schotland) het Manx snel te volgen. Er zijn nog maar enkele tienduizenden sprekers en hun aantal daalt snel, er is niet erg veel literatuur om het taalbewustzijn te steunen en de cultuur waarin de taal was geworteld, is goeddeels verdwenen. Voor het Iers is de situatie niet veel beter. Deze taal mag dan wel de eerste officiële taal van de Ierse Republiek zijn en als zodanig door iedere Ier op school geleerd worden, het werkelijke aantal mensen dat met en in deze taal opgroeit en haar nog dagelijks gebruikt overschrijdt de 20.000 waarschijnlijk nauwelijks of niet.

Binnen afzienbare tijd zullen dus ook de laatste afstammelingen van het Oudiers, dat ons zo’n rijke en boeiende literatuur heeft nagelaten, niet meer te horen zijn op deze planeet. Voor de andere nog levende tak van de Keltische taalfamilie – de talen die afstammen van het oude Brits of Brittannisch dat ten tijde van de Romeinen in vrijwel geheel Groot-Brittannië gesproken werd – is de situatie wat onduidelijker. Het Wels (in Wales) beleeft sinds enige decennia een geweldige opbloei en telde in 1981 ruim een half miljoen sprekers, maar in procenten van de bevolking blijft het aantal sprekers nog steeds dalen. Het Wels beschikt over zowat alles wat een taal zich wensen kan: onderwijs van kleuterschool tot en met universiteit, onafhankelijke radio- en televisiezenders, een bloeiend literair leven, een pers met tenminste één Welstalig dagblad, en aanzien bij zowel sprekers als niet-sprekers. Alleen een garantie voor de toekomst, die durft zelfs de meest optimistische beschouwer niet hardop uit te spreken.

Voor het Bretons in Bretagne is de situatie zo complex en zo ondoorzichtig dat er eigenlijk geen zinnig woord over te zeggen valt. Het aantal sprekers is nog nooit serieus vastgesteld – volgens de Franse regering bestaan er in Frankrijk geen andere talen dan het Frans, zodat dit bij volkstellingen geen vraag is. Hoewel diverse schattingen erop wijzen dat het aantal sprekers van het Bretons ongeveer een half miljoen zou kunnen zijn, is het goed mogelijk heel Bretagne rond te reizen zonder ook maar één woord Bretons te horen. Maatschappelijk aanzien heeft de taal niet, onderwijs is er nauwelijks en de (rijke) literatuur is er een van en voor insiders. Wanneer de Franse overheid haar beleid dan ook niet grondig wijzigt, en wanneer het de Bretons niet lukt elkaar te vinden in één allesomvattende reddingsactie, dan is de kans groot dat het Bretons geen lang leven meer beschoren zal zijn.

Een derde Brits-Keltische taal is al enige tijd niet meer onder de levenden. We hebben het dan over het Cornisch, de taal waartoe we ons hier verder zullen beperken. Rond 1800 overleden de laatste sprekers van deze taal – tot dan gesproken in het uiterste westen van Cornwall. Hier deed zich evenwel een merkwaardig fenomeen voor: er vond een herrijzenis plaats! In 1904 publiceerde Henry Jenner zijn Handbook of the Cornish Language, met de expliciete bedoeling dat de mensen van Cornwall de taal weer zouden leren en gaan gebruiken. In kleine kring sloeg dit idee aan en er ontstond een groepje liefhebbers die elkaar brieven en korte verhalen en gedichten in het Cornisch gingen toesturen. Uit deze groep trad vooral R. Morton Nance naar voren, die in 1929 een eenvoudige grammatica het licht deed zien onder de titel Cornish for All. Hierin propageerde hij ook een door hemzelf ontworpen, systematische spelling die nog steeds voor hedendaags – zogenaamd Revived – Cornisch gebruikt wordt (sinds 1986 is de Cornish Language Board begonnen met het invoeren van een verbeterde, zogenaamde ‘fonemische’ spelling voor deze taal; zie hiervoor ook Appendix B). In 1938 produceerde Nance zijn eerste woordenboek, dat meer dan vijftig jaar lang het enige was dat het hele Cornisch omvat. In 1993 verscheen een eerste versie van een woordenboek in de vernieuwde spelling, samengesteld door Ken George.

Of het werkelijk ooit zo ver zal komen dat Cornwall weer Cornisch-sprekend zal zijn, is hoogst onwaarschijnlijk, maar de ‘revival-beweging’ bestaat nu toch al zo’n eeuw en heeft het voor elkaar gekregen dat op scholen in Cornwall facultatief Cornisch onderwezen kan worden en dat de taal (zij het sporadisch) te horen is in regionale radioprogramma’s. Wel is het Revived Cornish nog steeds in hoge mate een ‘papieren’ taal; er wordt druk in geschreven, echte sprekers zijn er maar weinig. Ken George, taalkundige en actief revivalist, schatte hun aantal begin jaren ’90 op ongeveer tachtig personen who can speak the language all day without due fatigue. In tenminste twee gezinnen, waarvan één in Cardiff in Zuidoost-Wales, werden op dat moment de kinderen tweetalig (Cornisch – Engels) opgevoed…

L e e s m e e r…..

![]()

Lees de volledige tekst van Lauran Toorians:

Passie, lief en leed

de oudste poëzie van het Keltische Cornwall

![]()

![]()

Inleidend essay van Lauran Toorians:

De Keltische talen

en hun literaturen

![]()

© Lauran Toorians

KEMP=MAG poetry magazine

More in: CELTIC LITERATURE, Lauran Toorians

.jpg)

L o u i s e H e n s e l

(1798 – 1876)

A b e n d l i e d

Müde bin ich, geh’ zur Ruh’,

Schließe beide Äuglein zu;

Vater, laß die Augen dein

Über meinem Bette sein.

♦

Hab’ ich Unrecht heut getan,

Sieh’ es, lieber Gott, nicht an;

Deine Gnad’ und Jesu Blut

Macht ja allen Schaden gut.

♦

Alle, die mir sind verwandt,

Herr, laß ruhn in deiner Hand;

Alle Menschen, groß und klein,

Sollen dir befohlen sein.

♦

Kranken Herzen sende Ruh’,

Nasse Augen schließe zu;

Laß den Mond am Himmel stehn

Und die stille Welt besehn!

KEMP=MAG poetry magazine

More in: Archive G-H

Thomas a Kempis

(ca. 1380-1471)

Against vain and worldly knowledge

1

“My Son, let not the fair and subtle sayings of men move thee.

For the kingdom of God is not in word, but in power. (1) Give ear

to My words, for they kindle the heart and enlighten the mind,

they bring contrition, and they supply manifold consolations.

Never read thou the word that thou mayest appear more learned or

wise; but study for the mortification of thy sins, for this will

be far more profitable for thee than the knowledge of many

difficult questions.

.jpg)

2

“When thou hast read and learned many things, thou must always

return to one first principle. I am He that teacheth man

knowledge, (2) and I give unto babes clearer knowledge than can

be taught by man. He to whom I speak will be quickly wise and

shall grow much in the spirit. Woe unto them who inquire into

many curious questions from men, and take little heed concerning

the way of My service. The time will come when Christ will

appear, the Master of masters, the Lord of the Angels, to hear

the lessons of all, that is to examine the consciences of each

one. And then will He search Jerusalem with candles, (3) and the

hidden things of darkness (4) shall be made manifest, and the

arguings of tongues shall be silent.

3

“I am He who in an instant lift up the humble spirit, to learn

more reasonings of the Eternal Truth, than if a man had studied

ten years in the schools. I teach without noise of words,

without confusion of opinions, without striving after honour,

without clash of arguments. I am He who teach men to despise

earthly things, to loathe things present, to seek things

heavenly, to enjoy things eternal, to flee honours, to endure

offences, to place all hope in Me, to desire nothing apart from

Me, and above all things to love Me ardently.

4

“For there was one, who by loving Me from the bottom of his

heart, learned divine things, and spake things that were

wonderful; he profited more by forsaking all things than by

studying subtleties. But to some I speak common things, to

others special; to some I appear gently in signs and figures, and

again to some I reveal mysteries in much light. The voice of

books is one, but it informeth not all alike; because I inwardly

am the Teacher of truth, the Searcher of the heart, the Discerner

of the thoughts, the Mover of actions, distributing to each man,

as I judge meet.”

(1) 1 Corinthians iv. 20

(2) Psalm xciv. 10

(3) Zephaniah i. 12

(4) 1 Corinthians iv. 5

Thomas a Kempis: Imitatio Christi

The Third Book – Chapter XLIII

kempis poetry magazine

More in: MONTAIGNE, Thomas a Kempis

.jpg)

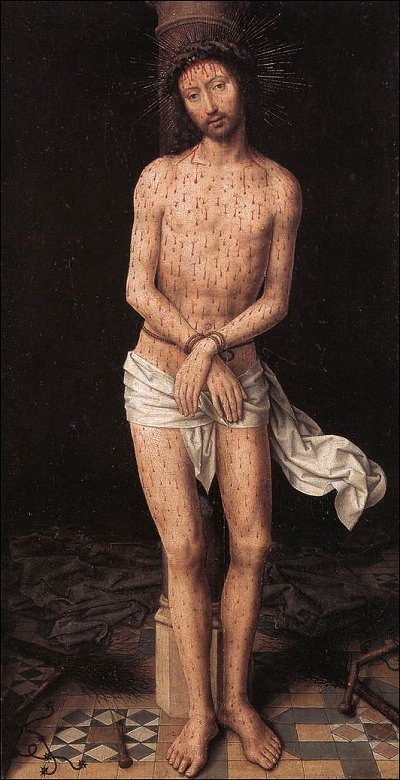

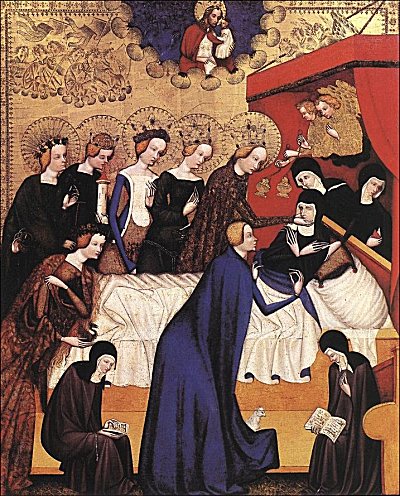

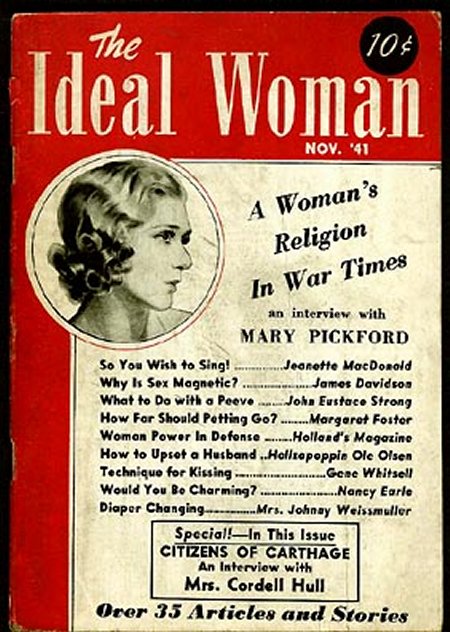

D e I d e a l e V r o u w 4

.jpg)

Noordbrabants Museum Den Bosch

De Ideale Vrouw

24 januari t/m/ 3 mei 2009

.jpg)

fleursdumal.nl magazine – magazine for art & literature

More in: The Ideal Woman

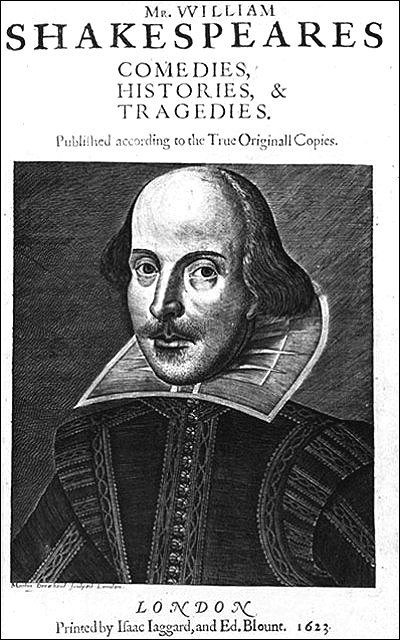

William Shakespeare

(1564-1616)

Sonnets 65 – 71

65

Since brass, nor stone, nor earth, nor boundless sea,

But sad mortality o’ersways their power,

How with this rage shall beauty hold a plea,

Whose action is no stronger than a flower?

O how shall summer’s honey breath hold out,

Against the wrackful siege of batt’ring days,

When rocks impregnable are not so stout,

Nor gates of steel so strong but time decays?

O fearful meditation, where alack,

Shall Time’s best jewel from Time’s chest lie hid?

Or what strong hand can hold his swift foot back,

Or who his spoil of beauty can forbid?

O none, unless this miracle have might,

That in black ink my love may still shine bright.

66

Tired with all these for restful death I cry,

As to behold desert a beggar born,

And needy nothing trimmed in jollity,

And purest faith unhappily forsworn,

And gilded honour shamefully misplaced,

And maiden virtue rudely strumpeted,

And right perfection wrongfully disgraced,

And strength by limping sway disabled

And art made tongue-tied by authority,

And folly (doctor-like) controlling skill,

And simple truth miscalled simplicity,

And captive good attending captain ill.

Tired with all these, from these would I be gone,

Save that to die, I leave my love alone.

67

Ah wherefore with infection should he live,

And with his presence grace impiety,

That sin by him advantage should achieve,

And lace it self with his society?

Why should false painting imitate his cheek,

And steal dead seeming of his living hue?

Why should poor beauty indirectly seek,

Roses of shadow, since his rose is true?

Why should he live, now nature bankrupt is,

Beggared of blood to blush through lively veins,

For she hath no exchequer now but his,

And proud of many, lives upon his gains?

O him she stores, to show what wealth she had,

In days long since, before these last so bad.

68

Thus is his cheek the map of days outworn,

When beauty lived and died as flowers do now,

Before these bastard signs of fair were born,

Or durst inhabit on a living brow:

Before the golden tresses of the dead,

The right of sepulchres, were shorn away,

To live a second life on second head,

Ere beauty’s dead fleece made another gay:

In him those holy antique hours are seen,

Without all ornament, it self and true,

Making no summer of another’s green,

Robbing no old to dress his beauty new,

And him as for a map doth Nature store,

To show false Art what beauty was of yore.

69

Those parts of thee that the world’s eye doth view,

Want nothing that the thought of hearts can mend:

All tongues (the voice of souls) give thee that due,

Uttering bare truth, even so as foes commend.

Thy outward thus with outward praise is crowned,

But those same tongues that give thee so thine own,

In other accents do this praise confound

By seeing farther than the eye hath shown.

They look into the beauty of thy mind,

And that in guess they measure by thy deeds,

Then churls their thoughts (although their eyes were kind)

To thy fair flower add the rank smell of weeds:

But why thy odour matcheth not thy show,

The soil is this, that thou dost common grow.

70

That thou art blamed shall not be thy defect,

For slander’s mark was ever yet the fair,

The ornament of beauty is suspect,

A crow that flies in heaven’s sweetest air.

So thou be good, slander doth but approve,

Thy worth the greater being wooed of time,

For canker vice the sweetest buds doth love,

And thou present’st a pure unstained prime.

Thou hast passed by the ambush of young days,

Either not assailed, or victor being charged,

Yet this thy praise cannot be so thy praise,

To tie up envy, evermore enlarged,

If some suspect of ill masked not thy show,

Then thou alone kingdoms of hearts shouldst owe.

71

No longer mourn for me when I am dead,

Than you shall hear the surly sullen bell

Give warning to the world that I am fled

From this vile world with vilest worms to dwell:

Nay if you read this line, remember not,

The hand that writ it, for I love you so,

That I in your sweet thoughts would be forgot,

If thinking on me then should make you woe.

O if (I say) you look upon this verse,

When I (perhaps) compounded am with clay,

Do not so much as my poor name rehearse;

But let your love even with my life decay.

Lest the wise world should look into your moan,

And mock you with me after I am gone.

William Shakespeare: Sonnets 65-71

kemp=mag poetry magazine

More in: Shakespeare, William

.jpg)

Galerie des Morts VII

Les Morts de Bruges

Photos Kempis

kemp=mag poetry magazine

More in: Galerie des Morts

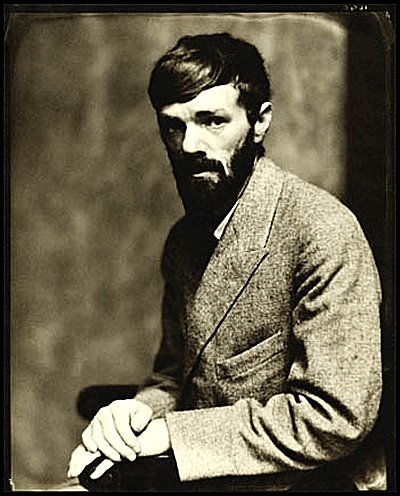

D.H. Lawrence

(1885-1930)

Ballad of Another Ophelia

Oh the green glimmer of apples in the orchard,

Lamps in a wash of rain!

Oh the wet walk of my brown hen through the stackyard,

Oh tears on the window pane!

Nothing now will ripen the bright green apples,

Full of disappointment and of rain,

Brackish they will taste, of tears, when the yellow dapples

Of autumn tell the withered tale again.

All round the yard it is cluck, my brown hen,

Cluck, and the rain-wet wings,

Cluck, my marigold bird, and again

Cluck for your yellow darlings.

For the grey rat found the gold thirteen

Huddled away in the dark,

Flutter for a moment, oh the beast is quick and keen,

Extinct one yellow-fluffy spark.

Once I had a lover bright like running water,

Once his face was laughing like the sky;

Open like the sky looking down in all its laughter

On the buttercups, and the buttercups was I.

What, then, is there hidden in the skirts of all the blossom?

What is peeping from your wings, oh mother hen?

’Tis the sun who asks the question, in a lovely haste for wisdom;

What a lovely haste for wisdom is in men!

Yea, but it is cruel when undressed is all the blossom,

And her shift is lying white upon the floor,

That a grey one, like a shadow, like a rat, a thief, a rain-storm,

Creeps upon her then and gathers in his store.

Oh the grey garner that is full of half-grown apples,

Oh the golden sparkles laid extinct!

And oh, behind the cloud-sheaves, like yellow autumn dapples,

Did you see the wicked sun that winked!

On That Day

On that day

I shall put roses on roses, and cover your grave

With multitude of white roses: and since you were brave

One bright red ray.

So people, passing under

The ash-trees of the valley-road, will raise

Their eyes and look at the grave on the hill, in wonder,

Wondering mount, and put the flowers asunder

To see whose praise

Is blazoned here so white and so bloodily red.

Then they will say: “’Tis long since she is dead,

Who has remembered her after many days?”

And standing there

They will consider how you went your ways

Unnoticed among them, a still queen lost in the maze

Of this earthly affair.

A queen, they’ll say,

Has slept unnoticed on a forgotten hill.

Sleeps on unknown, unnoticed there, until

Dawns my insurgent day.

Jealousy

The jealousy of an ego-bound woman

is hideous and fearful,

it is so much stronger than her love could ever be.

The jealousy of an ego-bound woman

is a fearful thing to behold

The ego revealed in all its monstrous inhumanity.

All I ask

All I ask of a woman is that she shall feel gently towards

me

when my heart feels kindly towards her,

and there shall be the soft, soft tremor as of unheard bells

between us.

It is all I ask.

I am so tired of violent women lashing out and insisting

on being loved, when there is no love in them.

kemp=mag poetry magazine

More in: Lawrence, D.H.

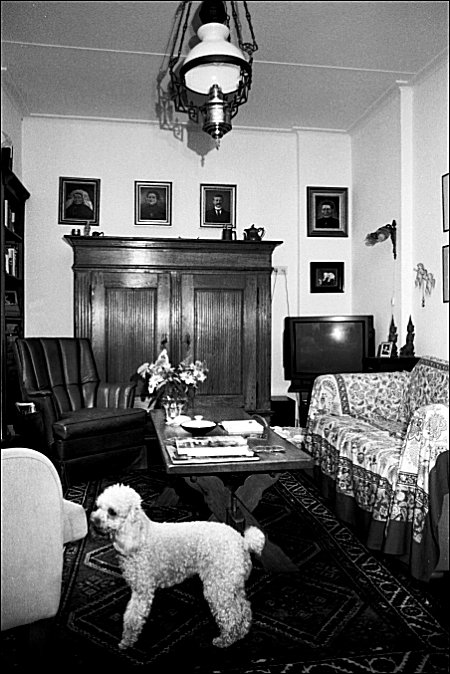

Harrie Janssens & Jef van Kempen

Het gevoel dat je hier thuishoort

Een geschiedenis van de Trouwlaan,

Zeehelden- en Uitvindersbuurt in Tilburg

Livius Boekhandel Tilburg

ISBN 90-807430-2-X

.jpg)

© H. Janssens

kempis mag poetry magazine

More in: Harrie Janssens Photos, OLV van de Veestraat

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature