Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Ton van Reen

DE GEVANGENE VIII

Ze stond met het kinderkaartje in de hand, had toch de tram genomen. De conducteur had meewarig naar het groene kinderkaartje gekeken. Hij knipte het toch, zonder wat te zeggen. Hij had haar net zo goed uit de tram kunnen zetten. Hij wist dat ze geen geld bij zich had. Het was zo’n man die iemands gezicht kon lezen. Waarschijnlijk had hij ook een dochter die dingen deed die hij zou moeten begrijpen.

De tram was vuil geweest. In de richeltjes van het hout zat fijn stof dat je er met een mes makkelijk uit zou kunnen peuteren. Daar zou bij de trammaatschappij nooit iemand aan gedacht hebben. De richeltjes hoorden niet in de vloer. Oorspronkelijk was de vloer mooi glad geweest. Die richeltjes waren er gekomen in zomer en winter. Van natte schoenen die sneeuw binnenbrachten, van blote voeten die graag gevoeld zouden hebben dat de vloer koel was.

Er zaten weinig mensen in de tram. Niet één die ze kende. Dat was ook niet nodig. Het waren slaperige mensen. Ze keken er haar op aan dat ze niet slaperig was. Ze dachten natuurlijk: dat meisje gaat naar hotel Eden. Zolang ze in hotel Eden kwam, verried ze zich. Was het haar manier van kijken? Ook al wist ze het, ze kon het niet veranderen.

Ze stapte uit de tram, vlak voor hotel Eden. De mensen knikten elkaar toe met blikken van: `Zie je nu wel, straks loopt ze naakt over het podium van hotel Eden, het zalige hotel voor de zondige feesten.’

De tram reed weg. Een zwarte rups zonder groen. Met lichte ogen en donkere wielen die je over de steentjes hoorde knerpen maar niet kon zien en die eigenlijk vleugels waren, al kon je ze nog zo goed horen lopen. Boven de tram spatte de bliksem van de elektriciteit alsof hij dat voor de lol deed. Misschien was dat ook zo en liet de stroom de tram alleen lopen omdat het een grap was. De kabel die hem van stroom voorzag, hing er alleen om te lachen.

Tussen de rails van de tram liep ze tot midden voor de poort van hotel Eden. Ze zag ergens een hond staan en dacht: jezus, het is weer allemaal hetzelfde. Onder het lopen maakte ze de knopen van haar kleren los, zodat ze die van haar lijf konden trekken, direct bij het binnenkomen. Voor de deur stonden Spaanse gastarbeiders die niet naar binnen mochten. Ze hadden te weinig geld. Ze zeiden dat ze waren gekomen om haar te zien. Toen ze geen asem gaf, hadden ze haar al te grazen. Gillen kon ze niet. Ze wilde het ook niet. Het interesseerde haar niet welke vent aan haar lijf zat, welke erin. Eigenlijk had ze een nieuwe tramkaart moeten hebben. Elke keer als er een Spanjaard was klaargekomen, had ze daar een knipteken in kunnen maken. Ze had nooit geld voor de tram. De conducteurs zagen dat aan haar. Toch waren ze nooit zo goed geweest om haar een rittenkaart te geven.

Nadat alle Spanjaarden waren klaargekomen, liepen ze weg. Een kwam er stiekem terug. Voorzichtig. De anderen mochten het blijkbaar niet zien. Hij hielp haar met aankleden. Ze bleven tussen de struiken liggen. Ze lag met haar hoofd in zijn schoot. Dat was fijn. Al kon ze ruiken dat hij zich slecht waste. Waarschijnlijk kwam hij uit een dorre streek waar ze water nog heilig vonden.

Plotseling hield ze van hem. Daarom keek ze niet naar zijn gezicht. Ze zou bang zijn dat hij het gebruikelijke gezicht van een vent had. Het liefst wilde ze dat zijn gezicht een dikke, vette puist was waar hij door ademde. En waarmee hij sprak. En at. Een puist zou beter zijn dan de kop van een kerel die je naaide en dan liet liggen. Per ongeluk zag ze zijn gezicht. Het was mooi. Het gezicht had de ogen dicht.

(wordt vervolgd)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - De gevangene

Hans Hermans photos ©2013: Splash 3

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Hans Hermans Photos

A n i t a B e r b e r

Gedicht für Sebastian Droste

I c h

Wachs schimmerndes Wachs

Ein Kopf – ein Brokatmantel

Wachs –

Rot – wie Kupfer so rot und lebende Haare

Funkelnde Haare wie heilige Schlangen und Flammen

Tot

Millionenmal tot

Verwest

Und schön – so schön

Blut wie fliessendes Blut

Ein Mund stumm

Nacht ohne Sterne und Mond

Die Lider – so schwer

Schnee wie kalter wärmende Schnee

Ein Hals – und fünf Finger wie Blut

Wachs wie Kerzen

Ein Opfer von ihm

S e b a s t i a n D r o s t e

Gedicht für Anita Berber

Tanz Anita zu eigen

Aufwirbelndes jauchzendes Begehren

Sprung – – –

Webenden Wellen

Weichwelle Wogen

Kreist kreist unendliche Kreise – – –

Verlangendes Weben schwebt wellwoges Wogen

Auf einsamen Thronen thront der Gott – –

Sturzwelles spitzes grelles Begehren

Kreisgelles gelbgrünes Belachen

Zerkreisen zerwellen zerwogen zerhauchen

Springpflanzartiges Zerblättern

Beschwingen

Besingen

Klang –

Aufjublendes Zerfliessen

Zergreifen

Zerweben – –

Tanz – – –

Anita Berber (1899-1928)

& Sebastian Droste (1892-1927):

2 Gedichte

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Anita Berber, Anita Berber, Berber, Anita, DANCE & PERFORMANCE

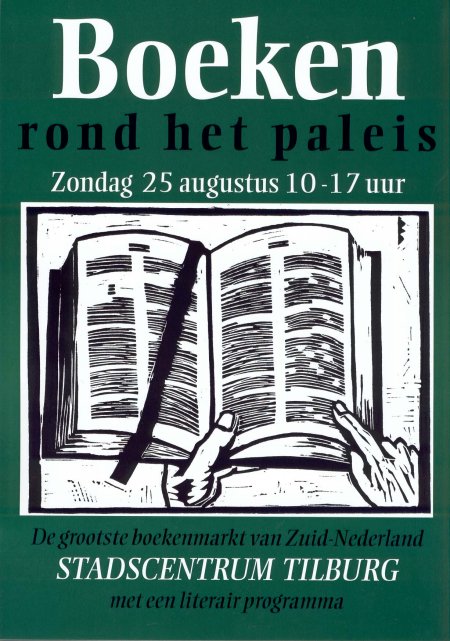

16e editie Boeken Rond Het Paleis Tilburg

op zondag 25 augustus 2013

+ installatie stadsdichter Jasper Mikkers

+ veel aandacht voor vertalers

Op zondag 25 augustus a.s. wordt voor de zestiende maal de boekenmarkt ‘Boeken rond het Paleis’ gehouden. Van 10.00 tot 17.00 uur kunnen de bezoekers weer hun slag slaan bij hun rondgang langs de meer dan 300 kramen. Leesvoer, te kust en te keur.

De markt belooft zeer levendig te worden, met erg aantrekkelijke koopwaar. Ook dit jaar speelt de BE-Brassband, en zal het carillon tijdens een speciaal concert haar zilveren klanken over de markt en haar bezoekers uitstrooien. Voor de allerjongste bezoekers is er een puzzeltocht uitgezet, waarmee zij een prijsje kunnen winnen. De literair geïnteresseerden kunnen, met Cees van Raak als gids, deelnemen aan een letterkundige wandeling door het centrum van Tilburg.

Zondag 25 augustus is ook de dag waarop Jasper Mikkers door wethouder Frenk officieel tot stadsdichter van Tilburg wordt geïnstalleerd. Dit zal plaatsvinden in het Paleis-Raadhuis. Van 12.00 tot 14.00 uur wordt daar gesproken, voorgedragen en gemusiceerd tijdens een programma dat er globaal als volgt uitziet:

– wethouder Frenk opent met een kort woordje de boekenmarkt 2013

– intermezzo

– wethouder Frenk neemt afscheid van de vorige stadsdichter, Esther Porcelijn

– commissievoorzitter Van Herwijnen leest juryrapport voor

– wethouder Frenk installeert Jasper Mikkers tot stadsdichter

– optreden Paul van Kemenade

– dankwoord Jasper Mikkers

– optreden Frank Starik (2010-2011 stadsdichter Amsterdam)

Het programma zal worden gepresenteerd door Max van den Burg.

Op de boekenmarkt wordt dit jaar ook aandacht geschonken aan de vertalers. Ze zijn aanwezig: u kunt ze aanspreken, met ze in discussie gaan, en en passant ook nog een mooi boek scoren!

Boekvertalers uit de kast!

Op de markt rond het Paleis komen behalve veel boeken ook boekvertalers uit de kast. Belangstellenden kunnen met ons een praatje aanknopen over ons mooie vak of in discussie gaan: “Tegenwoordig hebben we toch Google translate, dan zijn er toch geen vertalers meer nodig? En bovendien lees ik liever het origineel.”

Bij de boekvertalerskraam kun je ook kennismaken met Katrien, die enkele misverstanden over het vak aan de kaak stelt, en meespelen met een toepasselijk ‘electro’-spel en een vertalersganzenbord.

Verder kun je unieke boekenleggers scoren, en met een donatie aan een goed doel mag je (zolang de voorraad strekt) als tegenprestatie een vertaald boek meenemen!

Stichting Cools hoopt op veel aanloop en boeiende gesprekken!

Bij de landelijke groep boekvertalers zijn meer dan vierhonderd leden aangesloten, die uiteenlopende genres vertalen, van literatuur tot kookboeken, van thrillers tot kinderboeken, van fantasy tot bouquetreeks en chicklit. De taal waarin of waaruit vertaald wordt is het Nederlands. Engels is de meest voorkomende brontaal, maar ook vertalers uit het Frans, Duits, Italiaans, Portugees, Spaans, Noors, Hongaars en de klassieke talen nemen deel.

De groep treedt onder meer naar buiten met het weblog www.boekvertalers.nl, gericht op iedereen die van boeken houdt en belangstelling heeft voor het vertalersvak.

zondag 25 augustus 2013: 16e editie boeken rond het paleis tilburg

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, Art & Literature News

Edith Södergran

1892-1923

Der Schmerz

Das Glück hat keine Lieder, das Glück hat keine Gedanken,

das Glück hat nichts.

Stoß an dein Glück, daß es zerbricht, denn das Glück ist boshaft.

Das Glück kommt sacht wie das Säuseln des Morgens in

das schlafende Gebüsch,

das Glück gleitet vorbei wie leichte Wolken über dunkelblaue Tiefen,

das Glück ist wie das Feld, das in der Mittagsglut schläft

wie die endlose Weite des Meeres in den heißen lotrechten Strahlen,

das Glück ist machtlos, es schläft und atmet und weiß

von nichts …

Kennst du den Schmerz? Er ist stark und groß mit

geballten Fäusten.

Kennst du den Schmerz? Er lächelt hoffnungsvoll mit

verweinten Augen.

Der Schmerz gibt uns alles, was wir brauchen.

er gibt uns die Schlüssel zum Reich des Todes,

er schiebt uns durch die Pforte, wenn wir noch zaudern.

Der Schmerz tauft das Kind und wacht mit der Mutter

und schmiedet all die goldenen Hochzeitsringe.

Der Schmerz herrscht über alle, er glättet die Stirn des Denkers,

er legt den Schmuck um den Hals der begehrten Frau,

er steht in der Tür, wenn der Mann von der Geliebten kommt …

Was ist es noch, was der Schmerz seinen Lieblingen gibt?

Ich weiß nichts mehr.

Er gibt Perlen und Blumen, er gibt Lieder und Träume,

er gibt tausend Küsse, die alle leer sind,

er gibt den einzigen Kuß, der wirklich ist.

Er gibt uns unsere sonderbaren Seelen und merkwürdigen Einfälle,

er gibt uns allen Lebens höchsten Gewinn:

Liebe, Einsamkeit und das Angesicht des Todes.

Edith Södergran poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Södergran, Edith

.jpg)

Marcel Proust

(1871-1922)

Petit pastiche de Mme de Noailles

Mon coeur sage, fuyez l’odeur des térébinthes,

Voici que le matin frise comme un jet d’eau.

L’air est un écran d’or où des ailes sont peintes ;

Pourquoi partiriez-vous pour Nice ou pour Yeddo ?

Quel besoin avez-vous de la luisante Asie

Des monts de verre bleu qu’Hokusaï dessinait

Quand vous sentez si fort la belle frénésie

D’une averse dorant les toits du Vésinet !

Ah ! partir pour le Pecq, dont le nom semble étrange,

Voir avant de mourir le Mont Valérien

Quand le soigneux couchant se dispose et s’effrange

Entre la Grande Roue et le Puits artésien.

.jpg)

Marcel Proust poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Marcel Proust, Proust, Marcel

![]()

James Joyce

(1882-1941)

Counterparts

The bell rang furiously and, when Miss Parker went to the tube, a furious voice called out in a piercing North of Ireland accent:

“Send Farrington here!”

Miss Parker returned to her machine, saying to a man who was writing at a desk:

“Mr. Alleyne wants you upstairs.”

The man muttered “Blast him!” under his breath and pushed back his chair to stand up. When he stood up he was tall and of great bulk. He had a hanging face, dark wine-coloured, with fair eyebrows and moustache: his eyes bulged forward slightly and the whites of them were dirty. He lifted up the counter and, passing by the clients, went out of the office with a heavy step.

He went heavily upstairs until he came to the second landing, where a door bore a brass plate with the inscription Mr. Alleyne. Here he halted, puffing with labour and vexation, and knocked. The shrill voice cried:

“Come in!”

The man entered Mr. Alleyne’s room. Simultaneously Mr. Alleyne, a little man wearing gold-rimmed glasses on a cleanshaven face, shot his head up over a pile of documents. The head itself was so pink and hairless it seemed like a large egg reposing on the papers. Mr. Alleyne did not lose a moment:

“Farrington? What is the meaning of this? Why have I always to complain of you? May I ask you why you haven’t made a copy of that contract between Bodley and Kirwan? I told you it must be ready by four o’clock.”

“But Mr. Shelley said, sir—-“

“Mr. Shelley said, sir …. Kindly attend to what I say and not to what Mr. Shelley says, sir. You have always some excuse or another for shirking work. Let me tell you that if the contract is not copied before this evening I’ll lay the matter before Mr. Crosbie…. Do you hear me now?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Do you hear me now?… Ay and another little matter! I might as well be talking to the wall as talking to you. Understand once for all that you get a half an hour for your lunch and not an hour and a half. How many courses do you want, I’d like to know…. Do you mind me now?”

“Yes, sir.”

Mr. Alleyne bent his head again upon his pile of papers. The man stared fixedly at the polished skull which directed the affairs of Crosbie & Alleyne, gauging its fragility. A spasm of rage gripped his throat for a few moments and then passed, leaving after it a sharp sensation of thirst. The man recognised the sensation and felt that he must have a good night’s drinking. The middle of the month was passed and, if he could get the copy done in time, Mr. Alleyne might give him an order on the cashier. He stood still, gazing fixedly at the head upon the pile of papers. Suddenly Mr. Alleyne began to upset all the papers, searching for something. Then, as if he had been unaware of the man’s presence till that moment, he shot up his head again, saying:

“Eh? Are you going to stand there all day? Upon my word, Farrington, you take things easy!”

“I was waiting to see…”

“Very good, you needn’t wait to see. Go downstairs and do your work.”

The man walked heavily towards the door and, as he went out of the room, he heard Mr. Alleyne cry after him that if the contract was not copied by evening Mr. Crosbie would hear of the matter.

He returned to his desk in the lower office and counted the sheets which remained to be copied. He took up his pen and dipped it in the ink but he continued to stare stupidly at the last words he had written: In no case shall the said Bernard Bodley be… The evening was falling and in a few minutes they would be lighting the gas: then he could write. He felt that he must slake the thirst in his throat. He stood up from his desk and, lifting the counter as before, passed out of the office. As he was passing out the chief clerk looked at him inquiringly.

“It’s all right, Mr. Shelley,” said the man, pointing with his finger to indicate the objective of his journey.

The chief clerk glanced at the hat-rack, but, seeing the row complete, offered no remark. As soon as he was on the landing the man pulled a shepherd’s plaid cap out of his pocket, put it on his head and ran quickly down the rickety stairs. From the street door he walked on furtively on the inner side of the path towards the corner and all at once dived into a doorway. He was now safe in the dark snug of O’Neill’s shop, and filling up the little window that looked into the bar with his inflamed face, the colour of dark wine or dark meat, he called out:

“Here, Pat, give us a g.p.. like a good fellow.”

The curate brought him a glass of plain porter. The man drank it at a gulp and asked for a caraway seed. He put his penny on the counter and, leaving the curate to grope for it in the gloom, retreated out of the snug as furtively as he had entered it.

Darkness, accompanied by a thick fog, was gaining upon the dusk of February and the lamps in Eustace Street had been lit. The man went up by the houses until he reached the door of the office, wondering whether he could finish his copy in time. On the stairs a moist pungent odour of perfumes saluted his nose: evidently Miss Delacour had come while he was out in O’Neill’s. He crammed his cap back again into his pocket and re-entered the office, assuming an air of absentmindedness.

“Mr. Alleyne has been calling for you,” said the chief clerk severely. “Where were you?”

The man glanced at the two clients who were standing at the counter as if to intimate that their presence prevented him from answering. As the clients were both male the chief clerk allowed himself a laugh.

“I know that game,” he said. “Five times in one day is a little bit… Well, you better look sharp and get a copy of our correspondence in the Delacour case for Mr. Alleyne.”

This address in the presence of the public, his run upstairs and the porter he had gulped down so hastily confused the man and, as he sat down at his desk to get what was required, he realised how hopeless was the task of finishing his copy of the contract before half past five. The dark damp night was coming and he longed to spend it in the bars, drinking with his friends amid the glare of gas and the clatter of glasses. He got out the Delacour correspondence and passed out of the office. He hoped Mr. Alleyne would not discover that the last two letters were missing.

The moist pungent perfume lay all the way up to Mr. Alleyne’s room. Miss Delacour was a middle-aged woman of Jewish appearance. Mr. Alleyne was said to be sweet on her or on her money. She came to the office often and stayed a long time when she came. She was sitting beside his desk now in an aroma of perfumes, smoothing the handle of her umbrella and nodding the great black feather in her hat. Mr. Alleyne had swivelled his chair round to face her and thrown his right foot jauntily upon his left knee. The man put the correspondence on the desk and bowed respectfully but neither Mr. Alleyne nor Miss Delacour took any notice of his bow. Mr. Alleyne tapped a finger on the correspondence and then flicked it towards him as if to say: “That’s all right: you can go.”

The man returned to the lower office and sat down again at his desk. He stared intently at the incomplete phrase: In no case shall the said Bernard Bodley be… and thought how strange it was that the last three words began with the same letter. The chief clerk began to hurry Miss Parker, saying she would never have the letters typed in time for post. The man listened to the clicking of the machine for a few minutes and then set to work to finish his copy. But his head was not clear and his mind wandered away to the glare and rattle of the public-house. It was a night for hot punches. He struggled on with his copy, but when the clock struck five he had still fourteen pages to write. Blast it! He couldn’t finish it in time. He longed to execrate aloud, to bring his fist down on something violently. He was so enraged that he wrote Bernard Bernard instead of Bernard Bodley and had to begin again on a clean sheet.

He felt strong enough to clear out the whole office singlehanded. His body ached to do something, to rush out and revel in violence. All the indignities of his life enraged him…. Could he ask the cashier privately for an advance? No, the cashier was no good, no damn good: he wouldn’t give an advance…. He knew where he would meet the boys: Leonard and O’Halloran and Nosey Flynn. The barometer of his emotional nature was set for a spell of riot.

His imagination had so abstracted him that his name was called twice before he answered. Mr. Alleyne and Miss Delacour were standing outside the counter and all the clerks had turn round in anticipation of something. The man got up from his desk. Mr. Alleyne began a tirade of abuse, saying that two letters were missing. The man answered that he knew nothing about them, that he had made a faithful copy. The tirade continued: it was so bitter and violent that the man could hardly restrain his fist from descending upon the head of the manikin before him:

“I know nothing about any other two letters,” he said stupidly.

“You–know–nothing. Of course you know nothing,” said Mr. Alleyne. “Tell me,” he added, glancing first for approval to the lady beside him, “do you take me for a fool? Do you think me an utter fool?”

The man glanced from the lady’s face to the little egg-shaped head and back again; and, almost before he was aware of it, his tongue had found a felicitous moment:

“I don’t think, sir,” he said, “that that’s a fair question to put to me.”

There was a pause in the very breathing of the clerks. Everyone was astounded (the author of the witticism no less than his neighbours) and Miss Delacour, who was a stout amiable person, began to smile broadly. Mr. Alleyne flushed to the hue of a wild rose and his mouth twitched with a dwarf s passion. He shook his fist in the man’s face till it seemed to vibrate like the knob of some electric machine:

“You impertinent ruffian! You impertinent ruffian! I’ll make short work of you! Wait till you see! You’ll apologise to me for your impertinence or you’ll quit the office instanter! You’ll quit this, I’m telling you, or you’ll apologise to me!”

He stood in a doorway opposite the office watching to see if the cashier would come out alone. All the clerks passed out and finally the cashier came out with the chief clerk. It was no use trying to say a word to him when he was with the chief clerk. The man felt that his position was bad enough. He had been obliged to offer an abject apology to Mr. Alleyne for his impertinence but he knew what a hornet’s nest the office would be for him. He could remember the way in which Mr. Alleyne had hounded little Peake out of the office in order to make room for his own nephew. He felt savage and thirsty and revengeful, annoyed with himself and with everyone else. Mr. Alleyne would never give him an hour’s rest; his life would be a hell to him. He had made a proper fool of himself this time. Could he not keep his tongue in his cheek? But they had never pulled together from the first, he and Mr. Alleyne, ever since the day Mr. Alleyne had overheard him mimicking his North of Ireland accent to amuse Higgins and Miss Parker: that had been the beginning of it. He might have tried Higgins for the money, but sure Higgins never had anything for himself. A man with two establishments to keep up, of course he couldn’t….

He felt his great body again aching for the comfort of the public-house. The fog had begun to chill him and he wondered could he touch Pat in O’Neill’s. He could not touch him for more than a bob — and a bob was no use. Yet he must get money somewhere or other: he had spent his last penny for the g.p. and soon it would be too late for getting money anywhere. Suddenly, as he was fingering his watch-chain, he thought of Terry Kelly’s pawn-office in Fleet Street. That was the dart! Why didn’t he think of it sooner?

He went through the narrow alley of Temple Bar quickly, muttering to himself that they could all go to hell because he was going to have a good night of it. The clerk in Terry Kelly’s said A crown! but the consignor held out for six shillings; and in the end the six shillings was allowed him literally. He came out of the pawn-office joyfully, making a little cylinder, of the coins between his thumb and fingers. In Westmoreland Street the footpaths were crowded with young men and women returning from business and ragged urchins ran here and there yelling out the names of the evening editions. The man passed through the crowd, looking on the spectacle generally with proud satisfaction and staring masterfully at the office-girls. His head was full of the noises of tram- gongs and swishing trolleys and his nose already sniffed the curling fumes punch. As he walked on he preconsidered the terms in which he would narrate the incident to the boys:

“So, I just looked at him — coolly, you know, and looked at her. Then I looked back at him again — taking my time, you know. ‘I don’t think that that’s a fair question to put to me,’ says I.”

Nosey Flynn was sitting up in his usual corner of Davy Byrne’s and, when he heard the story, he stood Farrington a half-one, saying it was as smart a thing as ever he heard. Farrington stood a drink in his turn. After a while O’Halloran and Paddy Leonard came in and the story was repeated to them. O’Halloran stood tailors of malt, hot, all round and told the story of the retort he had made to the chief clerk when he was in Callan’s of Fownes’s Street; but, as the retort was after the manner of the liberal shepherds in the eclogues, he had to admit that it was not as clever as Farrington’s retort. At this Farrington told the boys to polish off that and have another.

Just as they were naming their poisons who should come in but Higgins! Of course he had to join in with the others. The men asked him to give his version of it, and he did so with great vivacity for the sight of five small hot whiskies was very exhilarating. Everyone roared laughing when he showed the way in which Mr. Alleyne shook his fist in Farrington’s face. Then he imitated Farrington, saying, “And here was my nabs, as cool as you please,” while Farrington looked at the company out of his heavy dirty eyes, smiling and at times drawing forth stray drops of liquor from his moustache with the aid of his lower lip.

When that round was over there was a pause. O’Halloran had money but neither of the other two seemed to have any; so the whole party left the shop somewhat regretfully. At the corner of Duke Street Higgins and Nosey Flynn bevelled off to the left while the other three turned back towards the city. Rain was drizzling down on the cold streets and, when they reached the Ballast Office, Farrington suggested the Scotch House. The bar was full of men and loud with the noise of tongues and glasses. The three men pushed past the whining matchsellers at the door and formed a little party at the corner of the counter. They began to exchange stories. Leonard introduced them to a young fellow named Weathers who was performing at the Tivoli as an acrobat and knockabout artiste. Farrington stood a drink all round. Weathers said he would take a small Irish and Apollinaris. Farrington, who had definite notions of what was what, asked the boys would they have an Apollinaris too; but the boys told Tim to make theirs hot. The talk became theatrical. O’Halloran stood a round and then Farrington stood another round, Weathers protesting that the hospitality was too Irish. He promised to get them in behind the scenes and introduce them to some nice girls. O’Halloran said that he and Leonard would go, but that Farrington wouldn’t go because he was a married man; and Farrington’s heavy dirty eyes leered at the company in token that he understood he was being chaffed. Weathers made them all have just one little tincture at his expense and promised to meet them later on at Mulligan’s in Poolbeg Street.

When the Scotch House closed they went round to Mulligan’s. They went into the parlour at the back and O’Halloran ordered small hot specials all round. They were all beginning to feel mellow. Farrington was just standing another round when Weathers came back. Much to Farrington’s relief he drank a glass of bitter this time. Funds were getting low but they had enough to keep them going. Presently two young women with big hats and a young man in a check suit came in and sat at a table close by. Weathers saluted them and told the company that they were out of the Tivoli. Farrington’s eyes wandered at every moment in the direction of one of the young women. There was something striking in her appearance. An immense scarf of peacock-blue muslin was wound round her hat and knotted in a great bow under her chin; and she wore bright yellow gloves, reaching to the elbow. Farrington gazed admiringly at the plump arm which she moved very often and with much grace; and when, after a little time, she answered his gaze he admired still more her large dark brown eyes. The oblique staring expression in them fascinated him. She glanced at him once or twice and, when the party was leaving the room, she brushed against his chair and said “O, pardon!” in a London accent. He watched her leave the room in the hope that she would look back at him, but he was disappointed. He cursed his want of money and cursed all the rounds he had stood, particularly all the whiskies and Apolinaris which he had stood to Weathers. If there was one thing that he hated it was a sponge. He was so angry that he lost count of the conversation of his friends.

When Paddy Leonard called him he found that they were talking about feats of strength. Weathers was showing his biceps muscle to the company and boasting so much that the other two had called on Farrington to uphold the national honour. Farrington pulled up his sleeve accordingly and showed his biceps muscle to the company. The two arms were examined and compared and finally it was agreed to have a trial of strength. The table was cleared and the two men rested their elbows on it, clasping hands. When Paddy Leonard said “Go!” each was to try to bring down the other’s hand on to the table. Farrington looked very serious and determined.

The trial began. After about thirty seconds Weathers brought his opponent’s hand slowly down on to the table. Farrington’s dark wine-coloured face flushed darker still with anger and humiliation at having been defeated by such a stripling.

“You’re not to put the weight of your body behind it. Play fair,” he said.

“Who’s not playing fair?” said the other.

“Come on again. The two best out of three.”

The trial began again. The veins stood out on Farrington’s forehead, and the pallor of Weathers’ complexion changed to peony. Their hands and arms trembled under the stress. After a long struggle Weathers again brought his opponent’s hand slowly on to the table. There was a murmur of applause from the spectators. The curate, who was standing beside the table, nodded his red head towards the victor and said with stupid familiarity:

“Ah! that’s the knack!”

“What the hell do you know about it?” said Farrington fiercely, turning on the man. “What do you put in your gab for?”

“Sh, sh!” said O’Halloran, observing the violent expression of Farrington’s face. “Pony up, boys. We’ll have just one little smahan more and then we’ll be off.”

A very sullen-faced man stood at the corner of O’Connell Bridge waiting for the little Sandymount tram to take him home. He was full of smouldering anger and revengefulness. He felt humiliated and discontented; he did not even feel drunk; and he had only twopence in his pocket. He cursed everything. He had done for himself in the office, pawned his watch, spent all his money; and he had not even got drunk. He began to feel thirsty again and he longed to be back again in the hot reeking public-house. He had lost his reputation as a strong man, having been defeated twice by a mere boy. His heart swelled with fury and, when he thought of the woman in the big hat who had brushed against him and said Pardon! his fury nearly choked him.

His tram let him down at Shelbourne Road and he steered his great body along in the shadow of the wall of the barracks. He loathed returning to his home. When he went in by the side- door he found the kitchen empty and the kitchen fire nearly out. He bawled upstairs:

“Ada! Ada!”

His wife was a little sharp-faced woman who bullied her husband when he was sober and was bullied by him when he was drunk. They had five children. A little boy came running down the stairs.

“Who is that?” said the man, peering through the darkness.

“Me, pa.”

“Who are you? Charlie?”

“No, pa. Tom.”

“Where’s your mother?”

“She’s out at the chapel.”

“That’s right…. Did she think of leaving any dinner for me?”

“Yes, pa. I –“

“Light the lamp. What do you mean by having the place in darkness? Are the other children in bed?”

The man sat down heavily on one of the chairs while the little boy lit the lamp. He began to mimic his son’s flat accent, saying half to himself: “At the chapel. At the chapel, if you please!” When the lamp was lit he banged his fist on the table and shouted:

“What’s for my dinner?”

“I’m going… to cook it, pa,” said the little boy.

The man jumped up furiously and pointed to the fire.

“On that fire! You let the fire out! By God, I’ll teach you to do that again!”

He took a step to the door and seized the walking-stick which was standing behind it.

“I’ll teach you to let the fire out!” he said, rolling up his sleeve in order to give his arm free play.

The little boy cried “O, pa!” and ran whimpering round the table, but the man followed him and caught him by the coat. The little boy looked about him wildly but, seeing no way of escape, fell upon his knees.

“Now, you’ll let the fire out the next time!” said the man striking at him vigorously with the stick. “Take that, you little whelp!”

The boy uttered a squeal of pain as the stick cut his thigh. He clasped his hands together in the air and his voice shook with fright.

“O, pa!” he cried. “Don’t beat me, pa! And I’ll… I’ll say a Hail Mary for you…. I’ll say a Hail Mary for you, pa, if you don’t beat me…. I’ll say a Hail Mary….”

James Joyce stories

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Joyce, James, Joyce, James

.jpg)

Amy Levy

(1861-1889)

A Farewell

(After Heine.)

The sad rain falls from Heaven,

A sad bird pipes and sings ;

I am sitting here at my window

And watching the spires of “King’s.”

O fairest of all fair places,

Sweetest of all sweet towns!

With the birds, and the greyness and greenness,

And the men in caps and gowns.

All they that dwell within thee,

To leave are ever loth,

For one man gets friends, and another

Gets honour, and one gets both.

The sad rain falls from Heaven;

My heart is great with woe–

I have neither a friend nor honour,

Yet I am sorry to go.

Amy Levy poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

Ton van Reen

DE GEVANGENE VII

Eigenlijk haatte ze de asman. Als ze door de Libertystraat liep, dacht ze altijd dat hij daar alleen zat om haar de stuipen op het lijf te jagen. Als ze uit het raam keek en de asman zat niet op het asvat, was ze bang dat hij ergens in huis was. Dan durfde ze haar kamer niet uit. Niet dat ze het erg zou vinden om door hem genaaid te worden! Welk meisje vond dat nog erg? Maar ze was bang dat zijn pik van as zou zijn. Dat hij als een gloeiende kool af zou knappen wanneer hij in haar lijf stak en dat ze hem er niet meer uit zou kunnen krijgen. De gloeiende kool zou haar vagina uitbranden. De asman zou, achter zijn vuile ogen aan, de trap af rennen en met zijn blote achterwerk en bloederige plek waar zijn pik had gezeten over straat rennen. Ze zou bang zijn dat in haar lijf iets zou knappen. Dat er een stuk uit zou springen.

Ze was blij dat ze de asman nog op het asvat zag zitten. Hij hield zijn handen in zijn zak, alsof hij ze daar warm kon houden aan zijn pik. Zou zijn bloedsomloop daar heviger zijn dan op de andere plaatsen van zijn gore lijf? Ze zou wel eens willen weten wanneer hij zich waste. Zou hij daar water bij gebruiken of alleen het vuil van zijn lijf strijken door de huid met zijn handen te masseren, zoals sommige diersoorten dat doen?

Het leek alsof hij veel nadacht. Soms verwachtte ze zelfs dat de woorden en zinnen aan zijn hersens zouden ontsnappen en in een ballon, net als in strips, boven zijn hoofd kwamen te hangen. Dan zou hij nooit meer wat zeggen, alleen af en toe de woorden in de denkzak om zijn hoofd veranderen.

Bij het aankleden trapte ze per ongeluk in het vocht dat op de vloer lag. Moet ik nu gillen? dacht ze. Hoeveel matten ze ook op de vloer legde en hoe dikwijls ze de kamer ook dweilde, het bleef altijd hetzelfde. Het vocht vrat als een grote gele zwam aan de vloerkleden. De twijnen in de stof werden zichtbaar. Net of de ratten aan moderne kunst deden, zich volvraten aan de impressie en de expressie als vuile poep lieten liggen. Ze deed haar beha aan. Haar borsten schoten onder de stof vandaan. Ze wenste dat er een vent in de buurt was die haar borsten wilde vasthouden en tegen haar lijf drukken, anders zou het haakje van de sluiting weer losschieten. Als de vent achter haar zou staan, de armen om haar borst, zou hij haar achterstevoren moeten naaien. Als een vent haar toch eenmaal vast zou hebben, wilde ze alles.

Zou ze zich straks weer moeten uitkleden in hotel Eden? Achter haar rug hingen dan foto’s van de beste klanten boven hun richels in de spaarkas. De spaarders zelf zouden om haar heen staan, haar een handje helpen met uitkleden. Ze voelde hun handen al in haar nek, op haar rug en aan de binnenkant van haar dijen.

Gisteravond was ze genaaid. Onmiddellijk nadat het was gebeurd, probeerde de vent haar kwijt te raken. Gaf haar een tramkaartje. Dacht dat een groen kinderkaartje genoeg voor haar was. Liep weg. Deed soms of hij zich wilde omdraaien. Om haar te laten zien dat hij aan zichzelf twijfelde, maar niet anders kon. Het was erger. Het was alleen zijn bedoeling ervandoor te gaan. Als ze een kind van hem zou krijgen, zou ze het ophangen met de benen omhoog. Omdat de vader een ploert was die alleen klaar wilde komen in een meisje en anders niets.

(wordt vervolgd)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - De gevangene

.jpg)

Novalis

(Friedrich von Hardenberg, 1772–1802)

Hymnen an die Nacht 4

Nun weiß ich, wenn der letzte Morgen seyn wird – wenn das Licht nicht mehr die Nacht und die Liebe scheucht – wenn der Schlummer ewig und nur Ein unerschöpflicher Traum seyn wird. Himmlische Müdigkeit fühl ich in mir. – Weit und ermüdend ward mir die Wallfahrt zum heiligen Grabe, drückend das Kreutz. Die krystallene Woge, die gemeinen Sinnen unvernehmlich, in des Hügels dunkeln Schooß quillt, an dessen Fuß die irdische Flut bricht, wer sie gekostet, wer oben stand auf dem Grenzgebürge der Welt, und hinübersah in das neue Land, in der Nacht Wohnsitz – warlich der kehrt nicht in das Treiben der Welt zurück, in das Land, wo das Licht in ewiger Unruh hauset.

Oben baut er sich Hütten, Hütten des Friedens, sehnt sich und liebt, schaut hinüber, bis die willkommenste aller Stunden hinunter ihn in den Brunnen der Quelle zieht – das Irdische schwimmt obenauf, wird von Stürmen zurückgeführt, aber was heilig durch der Liebe Berührung ward, rinnt aufgelöst in verborgenen Gängen auf das jenseitige Gebiet, wo es, wie Düfte, sich mit entschlummerten Lieben mischt.

Noch weckst du, muntres Licht den Müden zur Arbeit – flößest fröhliches Leben mir ein – aber du lockst mich von der Erinnerung moosigem Denkmal nicht. Gern will ich die fleißigen Hände rühren, überall umschaun, wo du mich brauchst – rühmen deines Glanzes volle Pracht – unverdroßen verfolgen deines künstlichen Werks schönen Zusammenhang – gern betrachten deiner gewaltigen, leuchtenden Uhr sinnvollen Gang – ergründen der Kräfte Ebenmaß und die Regeln des Wunderspiels unzähliger Räume und ihrer Zeiten. Aber getreu der Nacht bleibt mein geheimes Herz, und der schaffenden Liebe, ihrer Tochter. Kannst du mir zeigen ein ewig treues Herz? hat deine Sonne freundliche Augen, die mich erkennen? fassen deine Sterne meine verlangende Hand? Geben mir wieder den zärtlichen Druck und das kosende Wort? Hast du mit Farben und leichtem Umriß Sie geziert – oder war Sie es, die deinem Schmuck höhere, liebere Bedeutung gab? Welche Wollust, welchen Genuß bietet dein Leben, die aufwögen des Todes Entzückungen? Trägt nicht alles, was uns begeistert, die Farbe der Nacht? Sie trägt dich mütterlich und ihr verdankst du all deine Herrlichkeit. Du verflögst in dir selbst – in endlosen Raum zergingst du, wenn sie dich nicht hielte, dich nicht bände, daß du warm würdest und flammend die Welt zeugtest. Warlich ich war, eh du warst – die Mutter schickte mit meinen Geschwistern mich, zu bewohnen deine Welt, sie zu heiligen mit Liebe, daß sie ein ewig angeschautes Denkmal werde – zu bepflanzen sie mit unverwelklichen Blumen. Noch reiften sie nicht diese göttlichen Gedanken – Noch sind der Spuren unserer Offenbarung wenig – Einst zeigt deine Uhr das Ende der Zeit, wenn du wirst wie unser einer, und voll Sehnsucht und Inbrunst auslöschest und stirbst. In mir fühl ich deiner Geschäftigkeit Ende – himmlische Freyheit, selige Rückkehr. In wilden Schmerzen erkenn ich deine Entfernung von unsrer Heymath, deinen Widerstand gegen den alten, herrlichen Himmel. Deine Wuth und dein Toben ist vergebens. Unverbrennlich steht das Kreutz – eine Siegesfahne unsers Geschlechts.

Hinüber wall ich,

Und jede Pein

Wird einst ein Stachel

Der Wollust seyn.

Noch wenig Zeiten,

So bin ich los,

Und liege trunken

Der Lieb’ im Schooß.

Unendliches Leben

Wogt mächtig in mir

Ich schaue von oben

Herunter nach dir.

An jenem Hügel

Verlischt dein Glanz –

Ein Schatten bringet

Den kühlenden Kranz.

O! sauge, Geliebter,

Gewaltig mich an,

Daß ich entschlummern

Und lieben kann.

Ich fühle des Todes

Verjüngende Flut,

Zu Balsam und Aether

Verwandelt mein Blut –

Ich lebe bey Tage

Voll Glauben und Muth

Und sterbe die Nächte

In heiliger Glut.

![]()

Novalis poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

Charlotte Brontë

(1816 -1855)

The Wife’s Will

Sit still–a word–a breath may break

(As light airs stir a sleeping lake)

The glassy calm that soothes my woes–

The sweet, the deep, the full repose.

O leave me not! for ever be

Thus, more than life itself to me!

Yes, close beside thee let me kneel–

Give me thy hand, that I may feel

The friend so true–so tried–so dear,

My heart’s own chosen–indeed is near;

And check me not–this hour divine

Belongs to me–is fully mine.

‘Tis thy own hearth thou sitt’st beside,

After long absence–wandering wide;

‘Tis thy own wife reads in thine eyes

A promise clear of stormless skies;

For faith and true love light the rays

Which shine responsive to her gaze.

Ay,–well that single tear may fall;

Ten thousand might mine eyes recall,

Which from their lids ran blinding fast,

In hours of grief, yet scarcely past;

Well mayst thou speak of love to me,

For, oh! most truly–I love thee!

Yet smile–for we are happy now.

Whence, then, that sadness on thy brow?

What sayst thou? “We muse once again,

Ere long, be severed by the main!”

I knew not this–I deemed no more

Thy step would err from Britain’s shore.

“Duty commands!” ‘Tis true–’tis just;

Thy slightest word I wholly trust,

Nor by request, nor faintest sigh,

Would I to turn thy purpose try;

But, William, hear my solemn vow–

Hear and confirm!–with thee I go.

“Distance and suffering,” didst thou say?

“Danger by night, and toil by day?”

Oh, idle words and vain are these;

Hear me! I cross with thee the seas.

Such risk as thou must meet and dare,

I–thy true wife–will duly share.

Passive, at home, I will not pine;

Thy toils, thy perils shall be mine;

Grant this–and be hereafter paid

By a warm heart’s devoted aid:

‘Tis granted–with that yielding kiss,

Entered my soul unmingled bliss.

Thanks, William, thanks! thy love has joy,

Pure, undefiled with base alloy;

‘Tis not a passion, false and blind,

Inspires, enchains, absorbs my mind;

Worthy, I feel, art thou to be

Loved with my perfect energy.

This evening now shall sweetly flow,

Lit by our clear fire’s happy glow;

And parting’s peace-embittering fear,

Is warned our hearts to come not near;

For fate admits my soul’s decree,

In bliss or bale–to go with thee!

.jpg)

Currer Bell (Charlotte Brontë) poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Archive Tombeau de la jeunesse, Anne, Emily & Charlotte Brontë, Archive A-B, Brontë, Anne, Emily & Charlotte

Hendrik Marsman

(1899-1940)

Afscheid

Slaap met het donker, vrouw

slaap met de nacht

ons diepst omarmen

heeft de droom omgebracht

donker en zonder erbarmen

zijn bloed en geslacht

slaap met het donker, vrouw

slaap met de nacht.

Afscheid II

Ik ga op weg

en laat mijn huis

verdonkren

in het avondrood

– o, ga niet weg,

de nacht is groot.

Ik kan niet blijven

lieveling,

de dood ontbood mij

tot zijn kring;

vergeef mij

dat ik achterlaat

wat ik zozeer

heb liefgehad:

mijn huis, mijn stad,

mijn kleine straat

en u

mijn eigen hart,

ik hoor een lied

een grote stem.

– zijt gij dan niet

van mij?

. . . . . . van hem.

o, vrouw die

eenzaam achterblijft

in het verwaaiend

avondrood

o dood, o stem

de nacht is groot

en sterk de stem

die tussen slaap

en morgenrood

roept uit het

nieuw Jeruzalem.

.jpg)

Hendrik Marsman poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive M-N, Marsman, Hendrik

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature