Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Gabriele D’Annunzio

(1863-1938)

Sopra un erotik

Voglio un amore doloroso, lento,

che lento sia come una lenta morte,

e senza fine (voglio che più forte

sia de la morte) e senza mutamento.

Voglio che senza tregua in un tormento

occulto sian le nostre anime assorte;

e un mare sia presso a le nostre porte,

solo che pianga in un silenzio intento.

Voglio che sia la torre alta granito,

ed alta sia così che nel sereno

sembri attingere il grande astro polare.

Voglio un letto di porpora, e trovare

in quell’ombra giacendo su quel seno,

come in fondo a un sepolcro l’Infinito.

Pace

Pace, pace! La bella Simonetta

adorna del fugace emerocàllide

vagola senza scorta per le pallide

ripe cantando nova ballatetta.

Le colline s’incurvano leggiere

come le onde del vento nella sabbia

del mare e non fanno ombra, quasi d’aria.

L’Arno favella con la bianca ghiaia,

recando alle Nereidi tirrene

il vel che vi bagnò forse la Grazia,

forse il velo onde fascia

la Grazia questa terra di Toscana

escita della casalinga lana

che fu l’arte sua prima.

Pace, pace! Richiama la tua rima

nel cor tuo come l’ape nel tuo bugno.

Odi tenzon che in su l’estremo giugno

ha la cicala con la lodoletta!

Voglio un amore doloroso di

Voglio un amore doloroso, lento,

che lento sia come una lenta morte,

e senza fine (voglio che più forte

sia della morte) e senza mutamento.

Voglio che senza tregua in un tormento

occulto sian le nostre anime assorte;

e un mare sia presso a le nostre porte,

solo, che pianga in un silenzio intento.

Voglio che sia la torre alta granito,

ed alta sia così che nel sereno

sembri attingere il grande astro polare.

Voglio un letto di porpora, e trovare

in quell’ombra giacendo su quel seno,

come in fondo a un sepolcro, l’infinito.

Gabriele D’Annunzio poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, D'Annunzio, Gabriele

Alfonsina Storni

(1892-1938)

A Madona Poesia

Aqui a tus pies lanzada, pecadora,

contra tu tierra azul, mi cara oscura,

tú, virgen entre ejércitos de palmas

que no encanecen como los humanos.

No me atrevo a mirar tus ojos puros

ni a tocarte la mano milagrosa;

miro hacia atrás y un río de lujurias

me ladra contra tí, sin Culpa Alzada.

Una pequeña rama verdecida

en tu orla pongo con humilde intento

de pecar menos, por tu fina gracia,

ya que vivir cortada de tu sombra

posible no me fue, que me cegaste

cuando nacida con tus hierros bravos.

![]()

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Storni, Alfonsina

John Keats

(1795–1821)

Ode to a nightingale

My heart aches, and a drowsy numbness pains

My sense, as though of hemlock I had drunk,

Or emptied some dull opiate to the drains

One minute past, and Lethe-wards had sunk:

‘Tis not through envy of thy happy lot,

But being too happy in thine happiness,–

That thou, light-winged Dryad of the trees,

In some melodious plot

Of beechen green, and shadows numberless,

Singest of summer in full-throated ease.

O, for a draught of vintage! that hath been

Cool’d a long age in the deep-delved earth,

Tasting of Flora and the country green,

Dance, and Provençal song, and sunburnt mirth!

O for a beaker full of the warm South,

Full of the true, the blushful Hippocrene,

With beaded bubbles winking at the brim,

And purple-stained mouth;

That I might drink, and leave the world unseen,

And with thee fade away into the forest dim:

Fade far away, dissolve, and quite forget

What thou among the leaves hast never known,

The weariness, the fever, and the fret

Here, where men sit and hear each other groan;

Where palsy shakes a few, sad, last gray hairs,

Where youth grows pale, and spectre-thin, and dies;

Where but to think is to be full of sorrow

And leaden-eyed despairs,

Where Beauty cannot keep her lustrous eyes,

Or new Love pine at them beyond to-morrow.

Away! away! for I will fly to thee,

Not charioted by Bacchus and his pards,

But on the viewless wings of Poesy,

Though the dull brain perplexes and retards:

Already with thee! tender is the night,

And haply the Queen-Moon is on her throne,

Cluster’d around by all her starry Fays;

But here there is no light,

Save what from heaven is with the breezes blown

Through verdurous glooms and winding mossy ways.

I cannot see what flowers are at my feet,

Nor what soft incense hangs upon the boughs,

But, in embalmed darkness, guess each sweet

Wherewith the seasonable month endows

The grass, the thicket, and the fruit-tree wild;

White hawthorn, and the pastoral eglantine;

Fast fading violets cover’d up in leaves;

And mid-May’s eldest child,

The coming musk-rose, full of dewy wine,

The murmurous haunt of flies on summer eves.

Darkling I listen; and, for many a time

I have been half in love with easeful Death,

Call’d him soft names in many a mused rhyme,

To take into the air my quiet breath;

Now more than ever seems it rich to die,

To cease upon the midnight with no pain,

While thou art pouring forth thy soul abroad

In such an ecstasy!

Still wouldst thou sing, and I have ears in vain–

To thy high requiem become a sod.

Thou wast not born for death, immortal Bird!

No hungry generations tread thee down;

The voice I hear this passing night was heard

In ancient days by emperor and clown:

Perhaps the self-same song that found a path

Through the sad heart of Ruth, when, sick for home,

She stood in tears amid the alien corn;

The same that oft-times hath

Charm’d magic casements, opening on the foam

Of perilous seas, in faery lands forlorn.

Forlorn! the very word is like a bell

To toll me back from thee to my sole self!

Adieu! the fancy cannot cheat so well

As she is fam’d to do, deceiving elf.

Adieu! adieu! thy plaintive anthem fades

Past the near meadows, over the still stream,

Up the hill-side; and now ’tis buried deep

In the next valley-glades:

Was it a vision, or a waking dream?

Fled is that music:–Do I wake or sleep?

Ode aan een nachtegaal

Hartzeer en lome sufheid plaagt mijn geest,

Alsof ‘k een kerveldrank mij had bereid,

Of juist aan duffe opium was geweest

En was verzonken in vergetelheid:

‘t Komt niet door afgunst op jouw gunstig lot

Maar door te grote vreugd om jouw geluk, –

Dat jij, die vederlichte nimf van ‘t woud,

Vol melodiegenot

In ‘t schaduwrijke groen, zo druk

En zoetgevooisd een zomerzangfeest houdt.

O, gun mij een goede wijn! gekoeld bewaard

Diep in de grond, in jaren niet verzet,

Smakend naar Flora en de groene gaard,

Dans, Provençaalse zang, en zonnepret!

O, dat vol zuiderwarmte een glas hier stond,

Vol blozende en ware Hippocreen,

Met luchtbelkraaltjes glinsterend aan de rand,

En paars-gevlekte mond;

Dat ik mij laafde en uit het zicht verdween,

Met jou vervaagd in ‘t schimmig bomenland:

Vervaagd naar ver, versmolten, en gans kwijt

Wat tussen ‘t groen jij nooit hebt opgemerkt:

De sleur, de onrust en de narigheid

Alhier, waar men elkaars gekreun verwerkt;

Waar ziekte ‘t laatste, arm, grijs haar aantast,

Waar – ‘n bleke, magere schim – de jongen sterft;

Waar ‘t denken zelf al leidt tot diepe zorgen

En wanhoop’s loden last,

Waar ‘t oog van Schoonheid snel haar schittering derft,

Of nieuwe Liefd’ haar niet begeert na morgen.

Naar ver! naar ver! want ‘k volg jouw melodie,

Niet weggekard door Bacchus’ luipaard-span,

Maar op de blinde wiek der Poëzie,

Hoewel het trage brein dwarsliggen kan:

Teer is de nacht, bij jou daar in ‘t verschiet!

En ook, door al haar sterren-feeën omringd,

Zit op haar vorstentroon tevree de Maan;

Licht is híer echter niet,

Behalve wat uit hemelbriezen blinkt

Op somber groen en ‘t mos der slingerlaan.

Ik heb geen zicht op bloemen aan mijn voet,

Of welke wierook aan de takken hangt,

Maar raad in ‘t donker elk welriekend zoet

Dat bosje, vruchtboom wild, en gras ontvangt,

Geschonken door het passend jaargetij;

Rustieke egelantier en haagdoorn wit;

Viooltjes, snel verwelkt, door blad omhuld;

En ‘t oudste kind van Mei,

De muskusroos, waar nevelwijn in zit,

Op ‘n zomernacht met vlieggezoem gevuld.

In ‘t duister luister ik; en ik heb vaak

De Dood, die kalm maakt, half verliefd gekust,

Liefkoosde hem ook vaak met dichtersspraak,

Om lucht te geven aan mijn ademrust;

Nu meer dan ooit schijnt mij het sterven rijk,

Een middennachtelijk einde, vrij van pijn,

Terwijl jouw ziel zich uitstort uit ‘t gewas

En hoe hartstochtelijk!

Dan zong jij door: mijn oor zou nietig zijn –

En bij jouw requiem was ik wat gras.

Eeuwige Vogel! boreling vrij van dood;

Geen hongerbende ondermijnt jouw lot;

De stem die mij dit nachtuur heeft genood

Hoorde vanouds de keizer en de zot:

Misschien dezelfde zang die toegang vond

Tot ‘t droeve hart van Ruth, van heimwee ziek,

In tranen tussen ‘t vreemde koren staand;

Dezelfde die ‘t bestond

Vensters te openen, magisch met muziek,

Naar zeeschuim wild, in ‘n eens betoverd land.

Betoverd! juist het woord dat als een klok

Van jou mij terugluidt enkel naar mijzelf!

Vaarwel! De illusie mist de toverstok

Vaak toegedicht aan die misleidende elf.

Vaarwel! vaarwel! Jouw klaaglied vlucht ook al

Langs weiden hier, over de stille stroom,

De heuvel op, heeft nu een duik gemaakt

Diep in het volgend dal:

Was het een visioen, of wakkere droom?

Weg is het lied: – Slaap ik of ben ‘k ontwaakt?

Vertaling: Cornelis W. Schoneveld

Uit: Bestorm mijn hart, de beste Engelse gedichten uit de 16e-19e eeuw gekozen en vertaald door Cornelis W. Schoneveld, tweetalige editie. Rainbow Essentials no. 55, Uitgeverij Maarten Muntinga, Amsterdam, 2008, 296 pp, € 9,95 ISBN: 9789041740588

Bestorm mijn hart bevat een dwarsdoorsnede van vier eeuwen lyrische Engelse dichtkunst. Dichters uit de zestiende tot en met de negentiende eeuw dichter onder andere over liefde, natuur, dood en religie. Niet alleen de Nederlandse vertaling is in deze bundel te vinden, maar ook de originele Engelse versie. Deze prachtige bloemlezing, met gedichten van onder anderen Shakespeare, Milton, Pope en Wordsworth, is samengesteld en vertaald door Cornelis W. Schoneveld. Hij is vele jaren docent historische Engelse letterkunde en vertaalwetenschapper aan de Universiteit van Leiden geweest.

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, John Keats, Keats, Keats, John

![]()

Babelmatrix Translation Project

Imre Kertész

Imre Kertész was born in Budapest on November 9, 1929. Of Jewish descent, in 1944 he was deported to Auschwitz and from there to Buchenwald, where he was liberated in 1945. On his return to Hungary he worked for a Budapest newspaper, Világosság, but was dismissed in 1951 when it adopted the Communist party line. After two years of military service he began supporting himself as an independent writer and translator of German-language authors such as Nietzsche, Hofmannsthal, Schnitzler, Freud, Roth, Wittgenstein, and Canetti, who have all had a significant influence on his own writing.

Kertész’s first novel, Sorstalanság (Eng. Fateless, 1992; see WLT 67:4, p. 863), a work based on his experiences in Auschwitz and Buchenwald, was published in 1975. “When I am thinking about a new novel, I always think of Auschwitz,” he has said. This does not mean, however, that Sorstalanság is autobiographical in any simple sense: Kertész says himself that he has used the form of the autobiographical novel but that it is not autobiography. Sorstalanság was initially rejected for publication. When published eventually in 1975, it was received with compact silence. Kertész has written about this experience in A kudarc (1988; Fiasco). This novel is normally regarded as the second volume in a trilogy that begins with Sorstalanság and concludes with Kaddis a meg nem született gyermekért (1990; Eng. Kaddish for a Child Not Born, 1997; see WLT 74:1, p. 205), in a title that refers to the Jewish prayer for the dead. In Kaddis a meg nem született gyermekért, the protagonist of Sorstalanság and A kudarc, György Köves, reappears. His Kaddish is said for the child he refuses to beget in a world that permitted the existence of Auschwitz. Other prose works are A nyomkereso” (1977; The pathfinder) and Az angol labogó (1991; The English flag; see WLT 67:2, p. 412)

Sorstalanság (Hungarian)

A pályaudvarhoz érve, mivel kezdtem igen érezni a lábom, no meg mivel a sok többi közt a régröl ismert számmal is épp elibém kanyarodott egy, villamosra szálltam. Szikár öregasszony húzódott a nyitott peronon egy kissé félrébb, fura, ódivatú csipkegallérban. Hamarosan egy ember jött, sapkában, egyenruhában, és a jegyemet kérte. Mondtam néki: nincsen. Indítványozta: váltsak. Mondtam: idegenböl jövök, nincsen pénzem. Akkor megnézte a kabátomat, engem, s azután meg az öregasszonyt is, majd értésemre adta, hogy az utazásnak törvényei vannak, s ezeket a törvényeket nem ö, hanem az o” fölötte állók hozták. – Ha nem vált jegyet, le kell szállnia – volt a véleménye. Mondtam neki: de hisz fáj a lábam, s erre, észrevettem, az öregasszony ki, a tájék felé fordult, de oly sértödötten valahogyan, mintha csak néki hánytam volna a szemére netán, nem tudnám, mért. De a kocsi nyitott ajtaján, már messziroö nagy lármával, termetes, fekete, csapzott ember csörtetett ki. Nyitott inget, világos vászonöltönyt, a válláról szíjon függö fekete dobozt, kezében meg irattáskát hordott. Miféle dolog ez, kiáltotta, és: – Adjon egy jegyet! – intézkedett, pénzdarabot nyújtva, lökve inkább a kalauznak oda. Próbáltam köszönetet mondani, de félbeszakított, indulatosan tekintve körbe: – Inkább némelyeknek szégyenkezniük kellene – szólt, de a kalauz már a kocsiban járt, az öregasszony meg továbbra is kinézett. Akkor, megenyhült arccal, énfelém fordult. Kérdezte: – Németországból jössz, fiam? – Igen. – Koncentrációs táborból-e? – Természetesen. – Melyikbo”l? – A buchenwaldiból. – Igen, hallotta már hírét, tudja, az is „a náci pokolnak volt egyik bugyra” – így mondta. – Honnan hurcoltak ki? – Budapestro”l. – Meddig voltál oda? – Egy évig, egészében. – Sok mindent láthattál, fiacskám, sok borzalmat – mondta arra, s nem feleltem semmit. No de – így folytatta – foöhogy vége, elmúlt, s földerülö arccal a házakra mutatva, melyek közt épp csörömpöltünk, érdeklödött: mit érzek vajon most, újra itthon, s a város láttán, melyet elhagytam? Mondtam neki: – Gyülöletet. – Elhallgatott, de hamarosan azt az észrevételt tette, hogy meg kell, sajnos, értenie az érzelmeimet. Egyébként öszerinte „adott helyzetben” a gyülöletnek is megvan a maga helye, szerepe, „so haszna”, és föltételezi, tette hozzá, egyetértünk és jól tudja, hogy kit gyu”lölök. Mondtam neki: – Mindenkit. – Megint elhallgatott, ezúttal már hosszabb ido”re, utána meg újra kezdte: – Sok borzalmon kellett-e keresztülmenned? –, s azt feleltem, attól függ, mit tart borzalomnak. Bizonyára – mondta erre, némiképpen feszélyezettnek látszó arccal – sokat kellett nélkülöznöm, éheznem, és valószínu”leg vertek is talán, s mondtam neki: természetesen. – Miért mondod, édes fiam – kiáltott arra fel, de már-már úgy néztem, a türelmét vesztve –, mindenre azt, hogy „természetesen”, és mindig olyasmire, ami pedig egyáltalán nem az?! – Mondtam: koncentrációs táborban ez természetes. – Igen, igen – így o” –, ott igen, de… – s itt elakadt, habozott kissé – de… nohát, de maga a koncentrációs tábor nem természetes! – bukkant végre a megfelelo” szóra mintegy, s nem is feleltem néki semmit, mivel kezdtem lassan belátni: egy s más dologról sosem vitázhatunk, úgy látszik, idegenekkel, tudatlanokkal, bizonyos értelemben véve gyerekekkel, hogy így mondjam. Különben is – kaptam magam a változatlanul ott levo”, s éppen csak egy kissé kopárabbá és gondozatlanabbá vált térröl rajta –, ideje leszállanom, és ezt be is jelentettem neki. De velem tartott, s egy árnyas, támlája vesztett padot mutatva arrébb, indítványozta: telepednénk oda egy percre.

Elöször némelyest bizonytalankodni látszott. Valójában – jegyezte meg – most kezdenek még csak „igazán feltárulni a rémségek”, és hozzátette, „a világ egyelo”re értetlenül áll a kérdés elött: hogyan, miként is történhetett mindez egyáltalán meg”? Nem szóltam semmit, és akkor egész felém fordulva, egyszerre csak azt mondta: – Nem akarnál fiacskám, beszámolni az élményeidro”l? – Elcsodálkoztam kissé, és azt feleltem, hogy roppant sok érdekeset nemigen tudnék mondani neki. Akkor mosolygott kicsikét, és azt mondta: – Nem nekem: a világnak. – Amire, míg jobban csodálkozva, tudakoltam to”le: – De hát miröl? – A lágerek pokláról – válaszolta ö, melyre én azt jegyeztem meg, hogy meg egyáltalában semmit se mondhatok, mivel a pokolt nem ismerem, és még csak elképzelni se tudnám. De kijelentette, ez csak afféle hasonlat: – Nem pokolnak kell-e – kérdezte – elképzelnünk a koncentrációs tábort? – és azt feleltem, sarkammal közben néhány karikát írva lábam alá a porba, hogy ezt mindenki a maga módja és kedve szerint képzelheti el, hogy az én részemro”l azonban mindenesetre csak a koncentrációs tábort tudom elképzelni, mivel ezt valamennyire ismerem, a pokolt viszont nem. – De ha, mondjuk, mégis? – ero”sködött, s pár újabb karika után azt feleltem: – Akkor olyan helynek képzelném, ahol nem lehet unatkozni –; márpedig, tettem hozzá, koncentrációs táborban lehetett, meg Auschwitzban is – már bizonyos föltételek közt, persze. Arra hallgatott egy kicsit, majd meg azt kérdezte, de némiképp valahogy már-már a kedve ellenére szinte, úgy éreztem: – És ezt mivel magyarázod? –, s kis gondolkodás után azt találtam: – Az ido”vel. – Hogyhogy az ido”vel? – Úgy, hogy az ido” segít. – Segít…? miben? – Mindenben –, s próbáltam neki elmagyarázni, mennyire más dolog például megérkezni egy, ha nem is éppen fényu”zo”, de egészében elfogadható, tiszta, takaros állomásra, ahol csak lassacskán, ido”rendben, fokonként világosodik meg elo”ttünk minden. Mire egy fokozaton túl vagyunk, magunk mögött tudjuk, máris jön a következo”. Mire aztán mindent megtudunk, már meg is értettünk mindent. S mialatt mindent megért, ezenközben nem marad tétlen az ember: máris végzi az új dolgát, él, cselekszik, mozog, teljesíti minden újabb fok minden újabb követelményét. Ha viszont nem volna ez az ido”rend, s az egész ismeret mindjárt egyszerre, ott a helyszínen zúdulna ránk, meglehet, azt el sem bírná tán se koponyánk, sem a szívünk – próbáltam valamennyire megvilágítani néki, amire ö zsebéböl közben szakadozott papirosú dobozt halászva elö, melynek gyu”rött cigarettáit énfelém is idetartotta, de elhárítottam, majd két nagy szippantás után két könyékkel a térdére támaszkodva, így elo”redöntött felso”testtel és rám se nézve, kissé valahogy érctelen, tompa hangon ezt mondta: – Értem. – Másrészt, folytattam, az ebben a hiba, mondhatnám hátrány, hogy az ido”t viszont ki is kell tölteni. Láttam például – mondtam neki – foglyokat, akik négy, hat vagy éppen tizenkét esztendeje voltak már – pontosabban: voltak még mindig meg – koncentrációs táborban. Mármost ezeknek az embereknek mindezt a négy, hat vagy tizenkét esztendo”t, vagyis utóbbi esetben tizenkétszer háromszázhatvanöt napot, azaz tizenkétszer, háromszázhatvanötször huszonnégy órát, továbbá tizenkétszer, háromszázhatvanötször, huszonnégyszer… s mindezt vissza, pillanatonként, percenként, óránként, naponként: vagyis végig az egészet el kellett valahogy tölteniök. Megint másrészt viszont – fu”ztem tovább – épp ez segíthetett o”nekik is, mert ha mindez a tizenkétszer, háromszázhatvanötször, huszonnégyszer, hatvanszor és újra hatvanszornyi ido” mind egyszerre, egyetlen csapással szakadt volna a nyakukba, úgy bizonyára ök se állták volna – mint ahogy így állani bírták – se testtel, sem aggyal. S mivel hallgatott, hozzátettem még: – Így kell hát körülbelül elképzelni. – Ö meg erre, ugyanúgy, mint elöbb, csak cigaretta helyett, amit idöközben eldobott már, ezúttal az arcát tartva mind a két kezében, s talán etto”l még tompább, még fojtottabb hangon azt mondta: – Nem, nem lehet elképzelni –, s részemröl ezt be is láttam. Gondoltam is: akkor hát, úgy látszik, ezért mondanak helyette inkább poklot, bizonyára.

Imre Kertész

Onbepaald door het lot (Dutch)

Bij het station aangekomen, stapte ik op de tram omdat ik last kreeg van mijn voeten, bovendien was het een lijn die ik van vroeger kende. Op het open balkon ging een magere, oude vrouw met een eigenaardige, ouderwetse kanten kraag haastig opzij toen ze me zag. Weldra verscheen er een man met een pet en een uniform, die mijn kaartje wilde zien. Ik zei dat ik uit het buitenland kwam en geen geld bij me had. Hij monsterde mijn jas, keek eerst mij aan en vervolgens de oude vrouw en zei toen dat er bepaalde voorschriften golden voor het passagiersvervoer, die overigens niet door hem, maar ‘door de lui boven hem’ waren gemaakt. Als ik geen geld had voor een kaartje, moest ik de tram verlaten. Ik antwoordde dat ik pijn in mijn voeten had, waarop de oude vrouw haar blik afwendde en naar de straat keek, alsof ze beledigd was door mijn woorden, ja alsof ik haar een verwijt had gemaakt. Op dat ogenblik ging de tussendeur van het rijtuig open en kwam er een zwaar gebouwde, donkerharige man met een verwaarloosd uiterlijk het balkon op gestommeld die iets onverstaanbaars riep. Hij droeg een overhemd zonder stropdas en een lichtgekleurd linnen pak en had een aktentas in zijn hand. Aan een riem om zijn schouder hing iets wat eruitzag als een zwarte doos. ‘Wat heeft dat te betekenen?’ riep hij, en tegen de conducteur snauwde hij: ‘Geef die jongen oumiddellijk een kaartje!’ terwijl hij hem met een nogal bruusk gebaar een geldstuk overhandigde, of liever gezegd: toestopte. Ik wilde hem bedanken, maar hij onderbrak mij nog steeds boos om zich heen kijkend, en zei: ‘Bepaalde mensen hier zouden zich moeten schamen.’ De conducteur was echter al doorgelopen en de oude vrouw staarde nog steeds aandachtig naar de straat. Toen hij dit zag, wendde hij zich met een veel vriendelijker gezicht naar mij en vroeg: ‘Kom je net terug uit Duitsland, mijn jongen?’ ‘Ja’, zei ik. ‘Uit een concentratiekamp?’ ‘Natuurlijk.’ ‘Welk kamp?’ ‘Buchenwald.’ Hij zei dat hij daarvan had gehoord en noemde het een der meest beruchte krochten van de nazi-hel. ‘Waar ben je opgepakt?’ ‘In Boedapest.’ ‘Hoe lang heb je in het kamp gezeten?’ ‘Alles bij elkaar één jaar.’ ‘Die ogen van je zullen heel wat gezien hebben, jongen, veel gruwelijks’, zei hij toen hij dit hoorde, waarop ik niets terugzei. ‘Gelukkig is het nu allemaal voorbij’, vervolgde hij, en met een opgewekt gezicht naar de huizen wijzend waar de tram tussendoor ratelde, vroeg hij wat fik voelde nu ik weer thuis was en de stad terugzag. Ik zei: ‘Haat.’ Even zweeg hij, maar toen zei hij dat hij vreesde mijn gevoelens te moeten begrijpen. Overigens waren haatgevoelens volgens hem ‘in bepaalde situaties’ zeer functioneel en zelfs ‘nuttig’, wat ik waarschijnlijk uit eigen ervaring wel wist. Hij zei ook nog: ‘Ik weet heel goed wie je haat.’ Ik antwoordde: ‘Iedereen.’ Na dit antwoord zweeg hij opnieuw en nu duurde het veel langer voordat hij weer begon te spreken. Hij vroeg: ‘Heb je veel gruwelijke dingen meegemaakt?’ Ik zei hem dat ik die vraag moeilijk kon beantwoorden omdat ik niet wist wat hij met ‘gruwelijk’ bedoelde. ‘Je hebt ongetwijfeld veel ontberingen moeten doorstaan en honger geleden en misschien hebben ze je in het kamp ook geslagen’, zei hij met een enigszins gespannen gelaatsuitdrukking.’ Ik antwoordde: ’Natuurlijk.’ Daarop riep hij luid: ‘Waarom antwoord je op alles wat ik zeg „natuurlijk”, beste jongen, terwijl we het over zaken hebben die helemaal niet natuurlijk zijn?’ Ik had de indruk dat hij op het punt stond zijn geduld te verliezen en zei: ‘In een concentratiekamp zijn ze wel natuurlijk.’ ‘Nu ja, goed, daar misschien wel, maar…’ – op dat punt aangeland bleef hij even steken en aarzelde hij – ‘maar een concentratiekamp is op zichzelf niet natuurlijk.’ Dit laatste zei hij op opgeluchte toon, alsof hij eindelijk het juiste woord had gevonden. Ik gaf geen antwoord omdat ik langzamerhand begon in te zien dat je over sommige zaken eenvoudig niet kon discussiëren met buitenstaanders, die wat de kampen betreft totaal onwetend waren en als kleine kinderen konden worden beschouwd. Toen ik uit het raam keek, zag ik dat we het plein naderden waar ik moest uitstappen. Het lag er nog net zo bij als vroeger, maar de huizen waren wat grauwer en vervelozer dan bij mijn vertrek uit Boedapest en zagen er enigszins verwaarloosd uit. Ik zei tegen de onbekende dat ik mijn bestemming had bereikt en dus afscheid van hem moest nemen, maar hij wilde me kennelijk nog wat langer gezelschap houden en stapte eveneens uit. Buiten wees hij op een overschaduwd bankje waar de rugleuning van was verdwenen en hij stelde voor om daar even te gaan zitten.

Aanvankelijk wist hij niet goed hoe hij van wal moest steken. ‘Eigenlijk’, merkte hij op, ‘komen al die gruwelen nu pas aan het licht’, en hij voegde eraan toe ‘dat de wereld zich verbijsterd afvroeg hoe dit alles had kunnen gebeuren.’ Ik zei niets, waarop hij zich geheel naar mij toekeerde en onverwachts vroeg: ‘Zou je de mensen niet willen vertellen wat je allemaal hebt meegemaakt, mijn jongen?’ Ik was nogal verbaasd door deze vraag en antwoordde dat ik hem niet veel interessants te vertellen had, maar hij glimlachte flauwtjes en zei: ‘Niet mij, maar de wereld.’ Nog meer verbaasd dan eerst vroeg ik: ‘Maar wát zou ik dan moeten vertellen?’ ‘Wat een hel het concentratiekamp was’, antwoordde hij, waarop ik opmerkte dat ik daar niets over wist te zeggen omdat ik de hel niet kende en me die ook absoluut niet kon voorstellen. Hij zei daarop dat dit ook maar een vergelijking was. ‘Is een concentratiekamp dan geen hel?’ vroeg hij, en ik antwoordde met mijn hak kringetjes in het stof trekkend dat iedereen natuurlijk vrij was om zich bepaalde voorstellingen te maken, maar dat ik alleen wist wat een concentratiekamp was, althans ertigszins, doordat ik daar zelf in had gezeten, maar dat ik me bij het woord ‘hel’ niets kon voorstellen. ‘Maar als je je de hel toch probeert voor te stellen, hoe ziet die er dan uit?’ hield hij aan en ik antwoordde na nog wat nieuwe kringetjes te hebben getrokken: ‘Als een plaats waar je je niet kunt vervelen, en dat kon je in de kampen wel, zelfs in Auschwitz in bepaalde omstandigheden.’ Daarop zweeg hij enige tijd en vervolgens vroeg hij, bijna met tegenzin naar het scheen: ‘Heb je daar een verklaring voor?’ Na even nagedacht te hebben antwoordde ik: ‘Dat komt door de tijd.’ ‘Door de tijd? Wat bedoel je daarmee?’ ‘Ik bedoel dat de tijd helpt.’ ‘Helpt? Waarmee dan?’ ‘Met alles.’ Ik probeerde hem uit te leggen wat het was om op een misschien niet luxueus maar in elk geval acceptabel, goed onderhouden en schoon station aan te komen, waar de werkelijkheid pas langzaam en geleidelijk, als het ware stukje bij beetje, tot je doordrong. Zodra je een brokstukje van het geheel aan de weet was gekomen, diende zich alweer het volgende aan en tegen de tijd dat je alles wist, begreep je ook alles. Intussen keek je niet werkeloos toe, je deed wat je te doen stond, leefde, handelde, spande je in en trachtte aan de eisen te voldoen die bij elke nieuwe graad van inzicht hoorden. Als dit niet zo was geweest, als je niet geleidelijk met de werkelijkheid was geconfronteerd, maar door al die kennis onmiddellijk bij aankomst was overspoeld, hadden je hersenen en je hart dat waarschijnlijk niet kunnen verdragen. In dergelijke bewoordingen trachtte ik hem duidelijk te maken wat het is om in een concentratiekamp te zitten, waarop hij een rafelig kartonnen doosje uit zijn zak opdiepte en me een verfomfaaide sigaret aanbood, die ik niet accepteerde. Hij stak zelf wel op, maar na de rook tweemaal diep geïnhaleerd te hebben boog hij zijn bovenlichaam voorover, legde zijn ellebogen op zijn knieën en zei zonder me aan te kijken, op enigszins doffe, moedeloze toon: ‘Ik begrijp het.’ ‘Aan de andere kant’, vervolgde ik, ‘werkte de tijd ook tegen je, of laat ik zeggen in je nadeel, want je moest hem zien door te komen. Ik heb gevangenen gezien die al vier, zes of meer jaren in het kamp zaten, beter gezegd nog in het kamp zaten, en sommigen zelfs twaalf jaar. Deze mensen moesten vier, zes of twaalf lange jaren doorkomen, in het laatste geval dus twaalfmaal driehonderdvijfenzestig dagen, oftewel twaalfmaal driehonderdvijfenzestig maal vierentwintig uren, dat wil zeggen twaalfmaal driehonderdvijfenzestig maal vierentwintig… enzovoort. Al die seconden, minuten, uren, dagen, die hele lange tijd, moesten ze het op de een of andere manier zien vol te houden. En toch… toch was dit juist hun geluk, want als ze die onmetelijke hoeveelheid van twaalfmaal driehonderdvijfenzestig maal vierentwintig maal zestig maal nog eens zestig seconden in één keer over zich uitgestort hadden gekregen, waren ze daar vast niet tegen bestand geweest, lichamelijk noch geestelijk, terwijl ze dat nu wel waren.’ ‘Toen de man bleef zwijgen, voegde ik er nog aan toe: ’Zo moet u zich dat ongeveer voorstellen.’ Hiecrop gooide hij zijn sigaret weg en zei, nog steeds in dezelfde gebogen houding gezeten maar met zijn handen zijn gezicht bedekkend: ‘Nee, ik kán me dat niet voorstellen!’ Zijn stem klonk nog doffer dan daarstraks, bijna verstikt, zodat ik begreep dat hij daar werkelijk niet toe in staat was. Ik dacht: daarom noemen buitenstaanders de kampen natuurlijk graag een hel.

Henry Kammer

Publisher Van Gennep, Amsterdam

Source of the quotation p. 226-231.

Imre Kertész

Fateless (English)

On reaching the train station, I climbed aboard a streetcar because my leg was hurting and because I recognized one out of many with a familiar number. A thin old woman wearing a strange, old-fashioned lace collar moved away from me. Soon a man came by with a hat and a uniform and asked to see my ticket. I told him I had none. He insisted that I should buy one. I said I had just come back from abroad and was penniless. He looked at my coat, then at me, then at the old woman, and then he informed me that there were rules governing public transportation that not he but people above him had made. He said that if I didn’t buy a ticket, I’d have to get off. I told him my leg ached, and I noticed that the old woman responded to this by turning to look outside the window, in an insulted way, as if I were somehow accusing her of who knows what. Then through the car’s open door a large, black-haired man noisily galloped in. He wore a shirt without a tie and a light canvas suit. From his shoulder a black box hung, and an attaché case was in his hand. „What a shame!” he shouted. „Give him a ticket,” he ordered, and he gave or rather pushed a coin toward the conductor. I tried to thank him, but he interrupted me, looking around, annoyed: „Some people ought to be ashamed of themselves!” he said, but the conductor was already gone. The old woman continued to stare outside.

Then with a softened voice he said to me: „Are you coming from Germany, son?” „Yes,” I said. „From a concentration camp?” „Yes, of course.” „Which one?” „Buchenwald.” „Yes,” he answered, he had heard of it-one of the „pits of Nazi hell.” „Where did they carry you away from?” „Budapest.” „How long were you there?” „One year.” „You must have seen a lot, son, a lot of terrible things,” he said, but I didn’t reply. „Anyway,” he went on, „what’s important is that it’s over, it’s finished,” and with a cheerful face pointing to the buildings that we were passing, he asked me to tell him what I now felt, being home again, seeing the city I had left. I answered, „Hatred.” He fell silent, but soon he observed that, unfortunately, he had to say that he understood how I felt. He also felt that „under certain circumstances” there is a place and a role for hatred, „even a benefit,” and, he added, he assumed that we understood each other, and he knew full well the people I hated. I told him, „Everyone.” Then he fell silent again, this time for a longer period, and then he asked: „Did you have to go through many horrors?” I answered, „That depends on what you call a horror.” Surely, he replied with a tense face, I had been deprived of a lot, had gone hungry, and had probably been beaten. I said, „Naturally.” „Why do you keep saying ‘naturally,’ son,” he exclaimed, seeming to lose his temper, „when you are referring to things that are not natural at all?” „In a concentration camp,” I said, „they are very natural.” „Yes, yes,” he gasped, „it’s true there, but … well … but the concentration camp itself is not natural.” He seemed to have found the appropriate expression, but I didn’t even answer him, because I began to understand that there are certain subjects you can’t discuss, it seems, with strangers, ignorant people, and children, one might say. Besides – I suddenly noticed an unchanged, only slightly more bare and uncared-for square – it was time for me to get off, and I told him so. But he came after me, and pointing to a backless bench over in the shade, he suggested, „Let’s sit down for a minute.”

First he seemed somewhat insecure. „To tell the truth,” he observed, „it’s only now that the horrors are beginning to surface, and the world is still standing speechless and without understanding before the question How could all this have happened?” I was quiet, but he turned toward me and said: „Son, wouldn’t you like to tell me about your experiences?” I was a little surprised and told him that I couldn’t tell him very many interesting things. Then he smiled a little and said, „Not to me, to the world.” Even more astonished, I replied, „What should I talk about?” „The hell of the camps,” he replied, but I answered that I couldn’t say anything about that because I didn’t know anything about hell and couldn’t even imagine what it was like. He assured me that this was simply a metaphor. „Shouldn’t we picture the concentration camp like hell?” he asked. I answered, while drawing circles in the dust with my heels, that people were free to ignore it according to their means and pleasure but that, as far as I was concerned, I was only able to picture the concentration camp because I knew it a bit, but I didn’t know hell at all. „But, still, if you tried,” he insisted. After a few more circles, I answered, „In that case I’d imagine it as a place where you can’t be bored. But,” I added, „you can be bored in a concentration camp, even in Auschwitz – given, of course, certain circumstances.” Then he fell silent and asked, almost as if it was against his will: „How do you explain that?” After giving it some thought, I said, „By the time.” „What do you mean `by the time’?” „Because time helps.” „Helps? How?” „It helps in every way.”

I tried to explain how fundamentally different it is, for instance, to be arriving at a station that is spectacularly white, clean, and neat, where everything becomes clear only gradually, step by step, on schedule. As we pass one step, and as we recognize it as being behind us, the next one already rises up before us. By the time we learn everything, we slowly come to understand it. And while you come to understand everything gradually, you don’t remain idle at any moment: you are already attending to your new business; you live, you act, you move, you fulfill the new requirements of every new step of development. If, on the other hand, there were no schedule, no gradual enlightenment, if all the knowledge descended on you at once right there in one spot, then it’s possible neither your brains nor your heart could bear it. I tried to explain this to him as he fished out a torn package from his pocket and offered me a wrinkled cigarette, which I declined. Then, after two large inhalations, supporting his elbows on his knees with his upper body leaning forward, he said, without looking at me, in a colorless, dull voice: „I understand.”

„On the other hand,” I continued, „there is the unfortunate disadvantage that you somehow have to pass away the time. I’ve seen prisoners who were there for 4, 6, or even 12 years or more who were still hanging on in the camp. And these people had to spend these 4, 6, or 12 years times 365 days-that is, 12 times 365 times 24 hours – in other words, they had to somehow occupy the time by the second, the minute, the day. But then again,” I added, „that may have been precisely what helped them too, because if the whole time period had descended on them in one fell swoop, they probably wouldn’t have been able to bear it, either physically or mentally, the way they did.” Because he was silent, I added: „You have to imagine it this way.” He answered the same as before, except now he covered his face with his hands, threw the cigarette away, and then said in a somewhat more subdued, duller voice: „No, you can’t imagine it.” I, for my part, thought to myself. „That’s probably why they say `hell’ instead.”

Christopher C. Wilson, Katharina M. Wilson

Wilson, Katharina M.; Wilson, Christopher C.

Imre Kertész

Los utracony (Polish)

Dochodza;c do dworca, poniewaz. noga zaczyna?a juz. porza;dnie dawac’ mi sie; we znaki, a takz.e dlatego, z.e w?as’nie zatrzyma? sie; przede mna; jeden ze znanych mi z dawna numerów, wsiad?em do tramwaju. Na otwartym pomos’cie sta?a nieco z boku chuda, stara kobieta w dziwacznym, staromodnym koronkowym ko?nierzu. Wkrótce przyszed? jakis’ cz?owiek, w czapce, w mundurze, i poprosi? o bilet. Powiedzia?em mu: – Nie mam. – Zaproponowa?, z.ebym kupi?. Rzek?em: – Nie mam pienie;dzy. – Wtedy przyjrza? sie; mojej kurtce, mnie, potem równiez. starej kobiecie, i poinformowa? mnie, z.e jazda tramwajem ma swoje prawa i te prawa wymys’li? nie on, lecz ci, którzy stoja; nad nirn. – Jes’li pan nie wykupi biletu, musi pan wysia;s’c’ – orzek?. Powiedzia?em mu: – Ale przeciez. boli mnie noga – i wtedy zauwaz.y?em, z.e stara kobieta odwróci?a sie; i patrzy?a na ulice; z obraz.ona; mina;, jakbym mia? do niej pretensje, nie wiadomo dlaczego. Ale przez otwarte drzwi wagonu wpad?, czynia;c juz. z daleka wielki ha?as, postawny, czarnow?osy, rozczochrany me;z.czyzna. Nosi? rozpie;ta; koszule; i jasny p?ócienny garnitur, na ramieniu zawieszone na pasku czarne pude?ko i teczce; w re;ku. – Co tu sie; dzieje? – wykrzykna;? i zarza;dzi?: – Niech mu pan da bilet – wycia;gaja;c, raczej wpychaja;c konduktorowi pienia;dze. Próbowa?em podzie;kowac’, ale mi przerwa?, rozgla;daja;c sie; ze z?os’cia; dooko?a: – Raczej niektórzy powinni sie; wstydzic’ – oznajmi?, ale konduktor by? juz. w s’rodku, a stara kobieta nadal patrzy?a na ulice;. Wtedy ze z?agodnia?a; twarza; zwróci? sie; do mnie. Zapyta?: – Wracasz z Niemiec, synu? – Talc.- Zobozu?- Oczywis’cie.- Zktórego?- Z Buchenwaldu. – Tak, juz. o nim s?ysza?, wie, to takz.e „by?o dno nazistowskiego piek?a”, powiedzia?. – Ska;d cie; wiez’li? – Z Budapesztu. – Jak d?ugo tam by?es’? – Rok, ca?y rok. – Musia?es’ duz.o widziec’, synku, duz.o okrucien’stw -rzek?, a ja nic nie odpowiedzia?em. – No, ale – cia;gna;? – najwaz.niejsze, z.e to juz. koniec, mine;?o – i wskazuja;c z pojas’nia?a; twarza; domy, obok których w?as’nie przejez.dz.alis’my, zainteresowa? sie;: co teraz czuje;, znów w domu i na widok miasta, które opus’ci?em? Odpar?em mu: – Nienawis’c’. – Zamilk?, ale wkrótce zauwaz.y?, z.e niestety rozumie moje uczucia. Nawiasem mówia;c, wed?ug niego „w danej sytuacji” nienawis’c’ takz.e ma swoje miejsce i role;, „jest nawet poz.yteczna”, i przypuszcza, doda?, z.e sie; zgadzamy i on dobrze wie, kogo nienawidze;. Powiedzia?em mu: – Wszystkich. – Znów zamilk?, tym razem na d?uz.ej, a potem zacza;? na nowo: – Przeszed?es’ wiele potwornos’ci? – a ja odpar?em, z.e zalez.y, co uwaz.a za potwornos’c’. Na pewno, powiedzia? na to z troche; zaz.enowana; mina;, musia?em duz.o biedowac’, g?odowac’, i prawdopodobnie mnie takz.e bita, a ja mu powiedzia?em: – Oczywis’cie. – Dlaczego, synu – wykrzykna;? i widzia?em, z.e juz. traci cierpliwos’c’ – mówisz na wszystko „oczywis’cie”, i to zawsze wtedy, kiedy cos’ w ogóle nie jest oczywiste?! – Rzek?em: – W obozie koncentracyjnym jest oczywiste. – Tak, tak – on -tam tak, ale… – i utkna;?, zawaha? sie; troche;- ale… przeciez. sam obóz koncentracyjny nie jest oczywisty! – jakby wreszcie znalaz? w?as’ciwe s?owa, i nic mu nie odpowiedzia?em, poniewaz. z wolna zaczyna?em pojmowac’: o takich czy innych rzeczach nie dyskutuje sie; z obcymi, nies’wiadomymi, w pewnym sensie dziec’mi, z.e tak powiem. Zreszta; dostrzeg?em niezmiennie be;da;cy na swoim miejscu i tylko troche; bardziej pusty, bardziej zaniedbany plac: pora wysiadac’, i powiedzia?em mu o tym. AIe wysiad? ze mna; i wskazuja;c nieco dalsza;, zacieniona; ?awke;, która straci?a oparcie, zaproponowa?: – Moz.e usiedlibys’my na minutke;.

Najpierw mia? troche; niepewna; mine;. W istocie, zauwaz.y?, dopiero teraz zaczynaja; sie; „naprawde; ujawniac’ koszmary”, i doda?, z.e „s’wiat stoi na razie bezrozumnie przed pytaniem: jak, w jaki sposób mog?o sie; to wszystko w ogóle zdarzyc'”. Nic nie powiedzia?em, wtedy odwróci? sie; do mnie i nagle zapyta?: – Nie zechcia?bys’, synku, zrelacjonowac’ swoich przez.yc’? – Troche; sie; zdziwi?em i odpar?em, z.e w?as’ciwie nie mia?bym mu nic szczególnie ciekawego do powiedzenia. Na to sie; lekko us’miechna;? i powiedzia?: – Nie mnie, s’wiatu – na co jeszcze bardziej zdziwiony zapyta?em: – Ale o czym? – O piekle obozów – odpar?, na co zauwaz.y?em, z.e o tym to juz. w ogóle nic nie móg?bym powiedziec’, poniewaz. nie znam piek?a i nawet nie potrafi?bym go sobie wyobrazic’. Ale on oznajmi?, z.e to tylko taka przenos’nia: – Czyz. nie jako piek?o- spyta?- wyobraz.amy sobie obóz koncentracyjny? – a ja mu na to, zakres’laja;c przy tym obcasem kilka kó?ek w kurzu, z.e piek?o kaz.dy moz.e sobie wyobraz.ac’ na swój sposób i jes’li o mnie chodzi, to potrafie; sobie wyobrazic’ tylko obóz koncentracyjny, bo obóz troche; znam, piek?a natomiast nie. – Ale, gdyby, powiedzmy, jednak? – upiera? sie; i po kilku nowych kó?kach odpar?em: – To wyobraz.a?bym sobie, z.e jest to takie miejsce, gdzie nie moz.na sie; nudzic’, w obozie zas’ – doda?em -by?o moz.na, nawet w Os’wie;cimiu, rzecz jasna w pewnych warunkach. – Troche; milcza?, a potem jeszcze zapyta?, ale wyczu?em, z’e juz. jakos’ niemal wbrew woli: – Czym to t?umaczysz? – i po krótkim namys’le oznajmi?em: – Czasem. – Dlaczego czasem? – Bo czas pomaga. – Pomaga?… W czym?- We wszystkim – i próbowa?em mu wyt?umaczyc’, jaka to ca?kiem inna sprawa przyjechac’, na przyk?ad, na jes’li nawet nie wspania?a;, to ca?kiem do przyje;cia, czysta;, schludna; stacje;, gdzie powolutku, w porza;dku chronologicznym, stopniowo zaczyna sie; nam wszystko klarowac’. Kiedy mamy za soba; jeden etap, juz. przychodzi naste;pny. Kiedy sie; wszystkiego dowiemy, to rozumiemy tez. wszystko. A kiedy sie; cz?owiek wszystkiego dowiaduje, nie pozostaje bezczynny: wykonuje nowe zadanie, z.yje, dzia?a, porusza sie;, spe?nia wszystkie nowe wymagania wszystkich nowych etapów. Gdyby natomiast nie by?o tej chronologii i gdyby ca?a wiedza rune;?a nam na g?owe; od razu tam na stacji, to moz.e nie wytrzyma?aby tego ani g?owa, ani serce, próbowa?em mu jakos’ wyjas’nic’, na co wycia;gna;wszy z kieszeni poszarpana; paczke;, podsuna;? mi pogniecione papierosy, ale odmówi?em, patem zacia;gna;? sie; mocno dwa razy i opieraja;c ?okcie na kolanach, pochylony, nawet na mnie nie patrza;c, powiedzia? jakims’ troche; matowym, g?uchym g?osem: – Rozumiem. – Z drugiej strony – cia;gna;?em – wada;, powiedzia?bym, b?e;dem, jest to, z.e trzeba wype?nic’ czas. Widzia?em na przyk?ad – powiedzia?em mu – wie;z’niów, którzy cztery, szes’c’, a nawet dwanas’cie lat byli juz., a dok?adniej, wcia;z. jeszcze byli, w obozie. Otóz. ci ludzie musieli jakos’ wype?nic’ te cztery, szes’c’ czy dwanas’cie lat, czyli w ostatnim przypadku dwanas’cie razy po trzysta szes’c’dziesia;t pie;c’ dni, to jest dwanas’cie razy trzysta szes’c’dziesia;t pie;c’ razy dwadzies’cia cztery godziny, dalej: dwanas’cie razy trzysta szes’c’dziesia;t pie;c’ razy dwadzies’cia cztery razy… i wszystko od nowa, co chwile;, minute;, godzine;, dzien’, czyli z.e musza; ca?y ten czas jakos’ wype?nic’. Z drugiej natomiast strony- cia;gna;?em dalej – w?as’nie to mog?o im pomóc, bo gdyby ten ca?y czas, to znaczy dwanas’cie razy trzysta szes’c’dziesia;t pie;c’, razy dwadzies’cia cztery razy szes’c’dziesia;t i znów razy szes’c’dziesia;t, zlecia? im jednoczes’nie i za jednym zamachem na kark, to na pewno nie byliby tacy, jak sa;, ani jes’li idzie o g?owe;, ani o cia?o. – A poniewaz. milcza?, doda?em jeszcze: – A wie;c tak to mniej wie;cej trzeba sobie wyobraz.ac’. – A on na to tak samo jak przedtem, tylko zamiast papierosa, którego juz. tymczasem wyrzuci?, tym razem trzymaja;c w obu d?oniach twarz i moz.e przez to jeszcze bardziej g?uchym i jeszcze bardziej st?umionym g?osem powiedzia?: – Nie, nie moz.na sobie wyobrazic’ – i ja ze swojej strony zrozumia?em go. Pomys’la?em tez.: zatem, jak widac’, dlatego zamiast „obóz” mówia; „piek?o”, na pewno.

Pisarska, Krystyna

Source of the quotation : Los utracony, p. 250-255., WAB, Varsó, 2001

FLEURSDUMAL.NL MAGAZINE

More in: Archive K-L, Kertész, Imre

Hendrik Marsman

(1899-1940)

Doodstrijd

Ik lig zwaar en verminkt in een hoek van de nacht,

weerloos en blind: ik wacht

op de dood die nu eindelijk komen moet.

het paradijs is verbrand: ik proef roet,

dood, angst en bloed.

ik ben bang, ik ben bang voor de dood.

ik kan hem niet zien,

ik kan hem niet zien,

maar ik voel hem achter mij staan.

hij is misschien rakelings langs mij gegaan.

hij sluipt op zware geruisloze voeten onzichtbaar

achter het leven aan.

hij is weergaloos laf:

hij valt aan in de rug;

hij durft niet recht tegenover mij staan;

ik zou zijn schedel te pletter slaan.

ik heb nu nog, nu nog, een wild ontembaar

verlangen naar bloed.

Ontwaken

Ik lig nog te bed in de blinkende morgen

en hoor in mijn hart en daarbuiten het ruisen der nieuwe zee,

reuken en blijde geluiden

en de bloeiende geuren der kruiden

vervliegend als schuim in het zonlicht

en op de wind drijft het mee.

nu is er rust en een wijdheid vol nieuwe kracht;

voor mijn vertwijfeling en mijn stoutmoedigste droom

een onpeilbaar heelal:

water, zonlicht en gletschers

en ook bij nacht de kristallen

der glinsterende eeuwige sneeuw.

en hier – aan mijn zijde – het dal:

als de zachte gebogen kust van een klein en sluimerend meer;

zie hoe hij zich vouwt

in de bocht van een tere

en onuitputlijke droom.

.jpg)

Hendrik Marsman poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive M-N, Marsman, Hendrik

Street poetry: Rood, Wit, Groen

photo jef van kempen – brugge b

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Jef van Kempen Photos & Drawings, Photography, Street Art, Urban Art

Karl Kraus

(1874-1936)

Dichterschule

Was sind denn das für ausgelassne Knaben,

die in der Form ein Nichtgenügend haben?

Sie machen heute sichs wie ehedem

in Fleiß und Sitten immerzu bequem,

die nur im Fortgang von der Schule glänzen.

Und froh, daß sie die Syntax nicht beherrschen,

so wetzen sie auf ungegerbten Ärschen

und lassen hier und dort das Komma aus.

Dann aber tragen sie ein Nichts nachhaus,

das sie zuhaus zu einem Dreck ergänzen.

Heißt man zur Strafe sie dada zu bleiben,

und ihren Aufsatz zweimal abzuschreiben,

und besten Falles fällt es ihnen ein,

daß sie ihn noch beklecksen und betrenzen.

Kein Substantiv steht mehr an seinem Platze,

der Hauptsatz wird zu einem Nebensatze,

der Nebensatz ist nur ein Adjektiv.

Die ganze Gottesschöpfung lacht sich schief,

wenn solch ein grüner Lümmel singt von Lenzen.

Hier wirkt Natur in andern Dimensionen,

in solchem Wirrsal wollt’ kein Teufel wohnen,

nichts was sie greifen, wächst zur Wortgestalt.

Allein ihr Ethos freilich ist geballt

und sehr dynamisch sind die Impotenzen.

Ein Rattenschwanz im gegenseitigen Loben,

wenn sie in allezu freien Rhythmen toben;

mit uns geht alles bei dem Treiben rund!

Doch schließen sie zumeist den Vers mit Und.

Und dennoch geht es über alle Grenzen.

Sehr mir die Rotte von den letzten Bänken,

sie wollen nur den Oberlehrer kränken,

der schwergeprügelt in solcher Klasse sitzt.

Was sie nicht konnten, haben sie verschwitz.

O laßt uns diese Dichterschule schwänzen!

1920

Karl Kraus poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Kraus, Karl

USA: Commute Bradley Manning’s sentence and investigate the abuses he exposed

President Obama should commute US Army Private Bradley Manning’s sentence to time already served to allow his immediate release, Amnesty International said today.

Military judge Col Denise Lind today sentenced the Wikileaks source to 35 years in military prison – out of a possible 90 – for leaking reams of classified information. He has already served more than three years in pre-trial detention, including 11 months in conditions described by the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture as cruel and inhumane.

“Bradley Manning acted on the belief that he could spark a meaningful public debate on the costs of war, and specifically on the conduct of the US military in Iraq and Afghanistan. His revelations included reports on battlefield detentions and previously unseen footage of journalists and other civilians being killed in US helicopter attacks, information which should always have been subject to public scrutiny,” said Widney Brown, Senior Director of International Law and Policy at Amnesty International.

“Instead of fighting tooth and nail to lock him up for the equivalent of several life sentences, the US government should turn its attention to investigating and delivering justice for the serious human rights abuses committed by its officials in the name of countering terror.”

Some of the materials Manning leaked, published by Wikileaks, pointed to potential human rights violations and breaches of international humanitarian law by US troops abroad, by Iraqi and Afghan forces operating alongside US forces, and by military contractors. Yet the judge had ruled before the trial that Private Manning would not be able to defend himself by presenting evidence that he was acting in the public interest.

“Manning had already pleaded guilty to leaking information, so for the US to have continued prosecuting him under the Espionage Act, even charging him with ‘aiding the enemy,’ can only be seen as a harsh warning to anyone else tempted to expose government wrongdoing. ” said Brown.

“More than anything else, the case shows the urgent need to reform the USA’s antiquated Espionage Act and strengthen protections for those who reveal information that the public has a need and a right to know.”

Manning’s defence counsel is expected to file a petition for clemency shortly with the U.S. Department of Justice office that reviews requests for pardons and other acts of clemency before passing them on to the President for a final decision. Such requests are normally made after all appeals are exhausted, but the President may grant clemency at any time.

“Bradley Manning should be shown clemency in recognition of his motives for acting as he did, the treatment he endured in his early pre-trial detention, and the due process shortcomings during his trial. The President doesn’t need to wait for this sentence to be appealed to commute it; he can and should do so right now,” said Brown.

Amnesty International 21 august 2013

≡ website amnesty international

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: REPRESSION OF WRITERS, JOURNALISTS & ARTISTS

UK must account for its actions to repress Guardian reporting on surveillance

Attacks on the Guardian newspaper by UK authorities mark a new low in the struggle to protect freedom of expression, the right to information and protecting the independence of the media in the UK, Amnesty International said today.

The Guardian has reported that the UK authorities repeatedly threatened the newspaper’s management and led to it being forced to destroy information it had received from the US whistleblower Edward Snowden. This information is about unlawful surveillance by the US and the UK governments which violates their citizens’ and other people’s right to privacy.

“Forcing the Guardian to destroy information received from a whistleblower, without the authority of a court order, is a sinister turn of events that is both criminal and reprehensible,” said Tawanda Hondora, Deputy Director of Law and Policy at Amnesty International.

“This is just another example of the government trying to undermine press freedoms. It also seriously undermines the right of the public to know what governments do with their personal and private information. If confirmed, these actions expose the UK’s hypocrisy as it pushes for freedom of expression overseas.

“The UK government must explain its actions and publicly affirm its commitment to the rule of law, freedom of expression and the independence of the media. They should initiate an inquiry into who ordered this action against the Guardian.”

“Using strong-arm tactics to try to silence media outlets and reports that divulge information relating to Prism and other surveillance efforts, is unlawful and clearly against the public interest.”

The Guardian editor Alan Rusbridger on Monday published allegations about the UK authorities’ actions over the past several months to pressure the newspaper to hand over or destroy evidence related to the government surveillance.

Amnesty International 20 august 2013

≡ website amnesty international

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: REPRESSION OF WRITERS, JOURNALISTS & ARTISTS

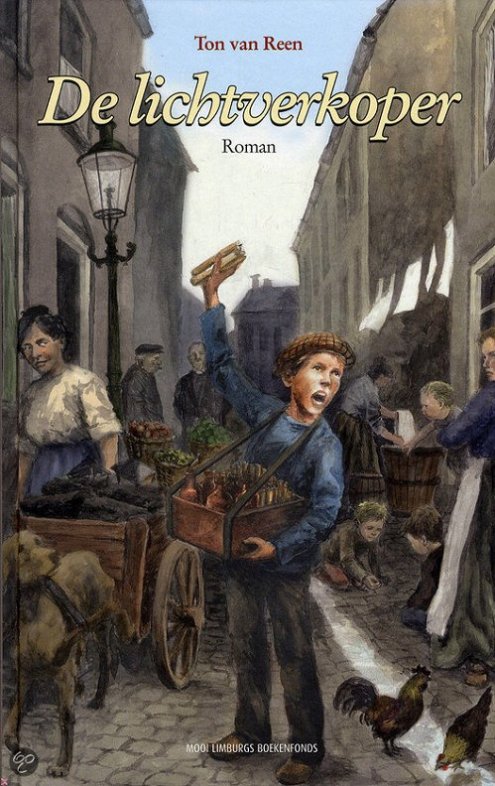

Op zondag 25 augustus vertelt Ton van Reen over zijn nieuwste roman De Lichtverkoper in Herberg De Bongerd te Beesel.

Maastricht in het jaar 1873. De twaalfjarige Casper Marres woont in de Cité Ouvrière, het mensenpakhuis dat grootindustrieel Petrus Regout voor arbeiders van zijn fabrieken heeft laten bouwen, dicht bij hun werk. Hoewel iedereen in het gezin Marres werkt, komen ze toch nauwelijks rond. De schatrijke Regout en de andere fabrieksdirecteuren in Limburg worden in hun liberale overtuigingen gesteund door behoudende geestelijken die de arbeiders leren dat de macht wordt geschonken door God en dat de armen de rijken moeten accepteren.

Het boek De Lichtverkoper is de ontroerende geschiedenis van Caspar en zijn familie, hun vrienden en de arbeiders die langzaam tot het inzicht komen dat ze hun armoede en rechteloosheid niet langer moeten aanvaarden. Het werpt licht op een donker tijdperk in de geschiedenis van de arbeiders, niet alleen in Maastricht, maar overal in Limburg.

Ton van Reen schreef dit boek om stem te geven aan de mensen die het slachtoffer waren van de hebzucht van de kleine groep schatrijke industriëlen die kapitalen verdienden over de ruggen van de arbeiders en hun gezinnen.

Dit boek verscheen eerder als feuilleton in Dagblad De Limburger/Limburgs dagblad en werd enthousiast door de lezers ontvangen.

Herberg De Bongerd, Markt 13, Beesel

Aanvang: 11.00 uur

More in: The talk of the town, Ton van Reen

.jpg)

E u g e n e M a r a i s

(1871-1936)

Don Quixote

Na A. von Chamisso

Nog ‘n avontuur

wat my roem beloof!

Sien jy al dié reuse,

klaar om weer te roof?

Toringhoog, misgeskape;

as jy vinnig kyk,

is dit of die rakkers

net soos meules lyk!

Met verlof, heer Ridder,

kyk hulle stip maar aan.

Dit is blote meules,

wat daar draaiend staan.

Sien jy, arme domkop,

gapend waar jy staan,

al die ongediertes

vas vir meules aan?

Oogverblindery

mag ‘n Kneg bedrieg,

maar ‘n edel Ridder

kan g’n Reus belieg.

Met verlof, heer Ridder,

glo my dit is waar,

net opregte meules

op die bultjie daar!

Beef, jy, vette lafaard?

Dit is klaar en hel,

stryd met sulke skepsels

is net kinderspel!

Een teen almal – daag ek,

vol van riddermoed!

Netnou drink die aarde

al jou ketterbloed!

Ag, my liewe Ridder,

glo my tog dié keer!

Meules is dit waarlik;

ek kan dit besweer!

“Soetste Dulcinea!

Bron van al my hoop!”

– En die brawe ridder

druk sy ros op loop;

storm af op die eerste

met die lans gemik –

en oorrompel stort hy

in die stof verstik.

Leef jy, edele Ridder?

Ek het jou gesê –

net so seker Meules

as jy nou daar lê!

Vra jy my miskien –

– soos baie mense meer –

was dit werklik reuse

soos die Baas beweer?

Of net blote Meules

glo ek met die Kneg?

Gee ek onbedenklik

onse Ridder reg?

Met die heer ooreenstem

is die kloekste kreet.

Wat van sulke dinge

kan ‘n Kneg tog weet?

Eugene Marais poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive M-N, Marais, Eugène

Renée Vivien

(1877–1909)

The Touch

The trees have kept some lingering sun in their branches,

Veiled like a woman, evoking another time,

The twilight passes, weeping. My fingers climb,

Trembling, provocative, the line of your haunches.

My ingenious fingers wait when they have found

The petal flesh beneath the robe they part.

How curious, complex, the touch, this subtle art—

As the dream of fragrance, the miracle of sound.

I follow slowly the graceful contours of your hips,

The curves of your shoulders, your neck, your unappeased breasts.

In your white voluptuousness my desire rests,

Swooning, refusing itself the kisses of your lips.

Renée Vivien poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive U-V, Renée Vivien, Vivien, Renée

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature