Fleurs du Mal Magazine

VPRO BOEKEN

Tineke Cleiren & Theodor Holman

Zondag 10 maart 2013 om 11.20 uur op Nederland 1

Tineke Cleiren en Antoine Hol: Strafrecht, tussen ratio en emotie

De Leidse hoogleraar strafrecht Tineke Cleiren schreef samen met haar man Antoine Hol, eveneens jurist, eveneens hoogleraar, het boek Strafrecht, tussen ratio en emotie. Het werd een boek waarin Cleiren uitlegt wat recht eigenlijk is, waar het voor staat en waar op dit moment in onze samenleving de knelpunten zitten.

Strafrecht, tussen ratio en emotie is een boek geworden dat uitlegt dat een goed functionerend strafrecht laveert tussen ratio en emotie, in plaats van een van die twee kanten te kiezen. Het beantwoordt vragen over eigenrichting, slachtofferschap, vergelding, verwerking en volksgerichten. Bijvoorbeeld legt het uit dat Officieren van Justitie niet alleen maar ‘crimefighters’ zijn die zorgen voor belastend bewijsmateriaal, maar dat ze ook voor ontlastend materiaal moeten zorgen. Alle denkbare paden moeten gevolgd worden, en aan iedere zaak zitten twee kanten. Hoe dit in de praktijk werkt, legt Cleiren zondag uit.

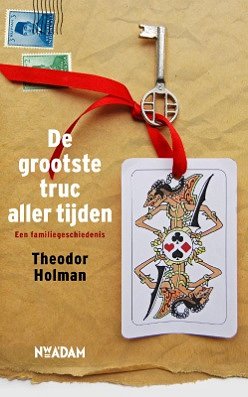

Theodor Holman: De grootste truc aller tijden

Schrijver Theodor Holman wist vrijwel niets van de Tweede Wereldoorlog in Nederlands-Indië. Daar kwam hij achter toen hij twee jaar geleden een redevoering hield bij een herdenking. Zijn ouders en zijn zus zaten in een jappenkamp, maar zijn ouders konden de woorden niet vinden om er goed over te vertellen en de jonge Theodor sloot zich af voor de verhalen. Nu maakt hij het goed, met De grootste truc aller tijden schreef hij een Indische familiegeschiedenis.

In de nalatenschap van zijn ouders vond hij het kampdagboek van zijn vader. Een klein, beduimeld boekje van pakpapier waarin zijn vader in priegelig handschrift zijn belevenissen aan de Birma-spoorlijn neerschreef. Achterin het boekje had zijn vader, die een niet onverdienstelijk goochelaar was, alle kaarttrucs die hij kende opgeschreven. De schrijver had zijn invalshoek gevonden en vertelt aanstaande zondag over zijn nieuwe boek, dat gaat over de ‘illusies die het leven ons flikt’.

Meer informatie op website: ≡ VPRO BOEKEN

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Archive G-H, The talk of the town

In Memoriam

Tsjêbbe Hettinga

(1949 – 2013)

Op 7 maart 2013 is in Leeuwarden de Friese dichter Tsjêbbe Hettinga overleden in. Vanaf zijn jeugdjaren kampte hij met een beperkt gezichtsvermogen. Desondanks trad hij vaak op tijdens poëzieavonden en literaire festivals. In december vorig jaar werd kanker bij hem geconstateerd. Hij werd vierenzestig jaar.

Hettinga groeide op als boerenzoon, op het Friese platteland. Hij volgde de kweekschool en studeerde in Groningen Nederlands en Fries. De afgelopen dertig jaar woonde hij in Leeuwarden. Tsjêbbe Hettinga heeft meer dan tien dichtbundels geschreven in de Friese Taal. Hij werd het boegbeeld van de Friese literatuur. Er is ook werk van hem vertaald in het Nederlands (Benno Barnard) en het Engels (James Brockway en Susan Massotty). In 2010 schreef Tsjêbbe Hettinga de Nationale Gedichtendagbundel.

Meer informatie op: ≡ Fryske literatuerside

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, In Memoriam

Ton van Reen

DE MOORD XXXIII

Zou ik nog ooit kunnen mierrijden? Kon ik nog beestjes in tweeën delen? Kon ik nog mieren berijden over een afstand van dertig centimeter of zou ik ze te vroeg kapotmaken? Godverdomme! Ik haatte mieren. Ik zou ze allemaal kapot willen trappen.

De melker stond op. Hij wreef over zijn gekneusde gezicht en liep naar buiten. Het paard stond vastgebonden aan een boom. De melker streelde het dier. Had het paard weet van wat er hier gebeurde? Had een paard weet van dingen en gebeurtenissen?

Ik probeerde op te staan. Het ging moeilijk. De soldaten hadden tegen mijn benen geschopt. Vellen hingen langs het vlees. Ik strompelde naar buiten.

‘Je moet hier blijven,’ riep ik tegen de melker.

Hij begon hard te lachen.

‘Waarom, waarom,’ riep hij. ‘Ik blijf hier niet. Ik breng het paard terug. Ik hoor niet bij het gezin. Ik hoor bij de beesten.’ Hij schreeuwde het uit. Het was angst, dat was duidelijk. Hij hoorde bij de beesten en hun ademhaling. De koeien, het gras en het prikkeldraad. Hij had gelijk. Hij hoorde niet bij de familie. Het liefst zou hij eeuwigdurend paarden tellen, zoals in Oeroe op de kermis. Hij telde de paarden op de draaimolen. De dolle paarden. Hij telde er meer dan driehonderd. Hij sprong op het paard. Het beest liep langzaam naar de weg. Wat ging er in zo’n beest om? En wat in de melker? Hij hoorde wel bij de familie!

‘Je moet terugkomen!’ schreeuwde ik.

De hoeven van het paard ketsten op de keien van de straat. Het laatste dat ik van de melker zag, was zijn rug. Hij zat met de armen omhoog, alsof iemand hem dat had bevolen. Misschien was hij bang dat er op hem geschoten werd. Dat was dan ook goed mogelijk.

Cherubijn staarde me aan toen ik binnenkwam. Hij had het schreeuwen gehoord. Hij vroeg niets maar leek alles te begrijpen. Jonas Uit De Walvis begreep alles. Voor Jonas Uit De Walvis bestond geen geluk. Ik kon me voorstellen hoe ze Jonas uit de tank schoten, hoe hij in een boog door de lucht vloog, te pletter viel en toch bleef leven. Ik kon het me best voorstellen. Nu schroefde Jonas zijn houten poot los en sloeg hard op de vloer zodat de splinters eraf vlogen en er fraaie wolken van stof door de kamer dwarrelden.

(wordt vervolgd)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: - De moord

![]()

hollands maandblad schrijversbeurzen uitgereikt

De dichteres en theatermaakster Esther Porcelijn (1985), schrijfster en kunsthistorica Bregje Hofstede (1988) en schrijver Maxim Roozen (1991) zijn de winnaars van de Hollands Maandblad beurzen 2012/2013. De laureaten kregen de prijzen uitgereikt in Amsterdam door Wim Brands tijdens het jaarlijkse Hollands Maandblad-literatuurfeest. Porcelijn en Hofstede ontvingen elk de Hollands Maandblad Aanmoedigingsbeurs (ter waarde van € 1000), en Roozen ontving de Hollands Maandblad schrijversbeurs (ter waarde van € 2000). Alle drie de schrijvers zijn medewerkers van het 54-jaar oude toonaangevende literaire tijdschrift dat onder redactie staat van Bastiaan Bommeljé, wordt uitgegeven door Uitgeverij Nieuw Amsterdam en onlangs door het Letterenfonds en Prins Bernhard Cultuurfonds als een der vier beste literair tijdschriften van Nederland werd beloond met € 25.000 subsidie.

Porcelijn werd door de jury bekroond voor haar poëzie ‘die zonder kloppen binnenkomt’ met verzen die ‘onomwonden, gekarteld en tegendraads’ zijn. Hofstede kreeg de prijs vanwege het brede literaire spectrum dat zij bestrijkt, ‘dat reikt van dromerig proza tot hard-boiled essayistiek’. Roozen werd onderscheiden voor de ‘verbluffend vanzelfsprekende’ wijze waarop hij als debutant ‘het levensgevoel en de geesteswereld van de hedendaagse jeugd wist te schetsen’.

Eerdere laureaten van de Hollands Maandblad-beurzen waren onder anderen Vrouwkje Tuinman, Yusuf el-Halal (Ernest van der Kwast), Anke Scheeren, Nina Roos, Philip Huff en Kira Wuck.

Hollands Maandblad is het grootste zelfstandige literaire tijdschrift van Nederland en werd in 1959 opgericht door K.L. Poll. Tot de medewerkers behoren o.m. Arnon Grunberg, Leo Vroman, Kira Wuck, Eva Gerlach, Iris Le Rutte, Hugo Brandt Corstius, J.M.A. Biesheuvel, Wim Brands, Philip Huff, David Pefko, A.H.J. Dautzenberg, Maartje Wortel, Vrouwkje Tuinman en Maarten ’t Hart.

juryrapport hollands maandblad schrijversbeurzen 2012/2013

Redactie, redactieraad en uitgever van Hollands Maandblad,

tezamen met het bestuur van de Stichting Hollands Maandblad,

hebben het genoegen mede te delen dat tijdens een feestelijke bijeenkomst

te Amsterdam de Hollands Maandblad Schrijversbeurzen 2012/2013 zijn uitgereikt.

Op voordracht van redactie & redactieraad werden de volgende medewerkers

van Hollands Maandblad aangewezen als winnaar

*

Hollands Maandblad Aanmoedigingsbeurs: categorie poëzie

esther porcelijn

*

Hollands Maandblad Aanmoedigingsbeurs: categorieën proza & essayistiek

bregje hofstede

*

Hollands Maandblad Schrijversbeurs:

maxim roozen

*

Esther Porcelijn (1985) werd bekroond met een Hollands Maandblad Aanmoedigingsbeurs in de categorie poëzie. En dat terwijl deze theatermaakster, toneelspeelster, schrijfster, filosofiestudente in feite weinig aanmoediging meer nodig heeft. Dat zij eind vorig jaar vrijwel gelijktijdig debuteerde met haar poëzie in Hollands Maandblad en werd uitverkoren tot stadsdichter van Tilburg was geen toeval. De laureaat heeft op talrijke podia en diverse festivals bewezen een buitengewoon multi-talent te zijn, en te beschikken over een tomeloze dadendrang, een wervelende dynamiek en een navenante pen. De jury werd onmiddellijk getroffen door haar gedichten die Hollands Maandblad binnenkwamen zonder kloppen en gewapend met woorden die even glashelder als persoonlijk, en even poëtisch als onomwonden, maar bovenal hard, gekarteld en tegendraads waren. In elk geval kreeg de lezer van Hollands Maandblad nimmer eerder nog voordat de titel van het gedicht aan de orde was bij wijze van poëtische preambule deze verzen toegeworpen:

Laten we het even niet over kwantummechanica hebben…

Even niet over mensenrechten…

Want daar loopt een vrouw met grote borsten.

Waarna een dichterlijk-wijsgerige zoektocht naar de zin van het leven volgt die klinkt als een urban rap met de urgentie van een locomotief die aan komt stormen uit de donkerste krochten van de menselijke beschaving, of misschien uit die van Tilburg. Vol verwachtingen over de letterkundige toekomst van deze laureaat kent de jury de Hollands Maandblad Aanmoedigingsbeurs in de categorie poëzie toe aan Esther Porcelijn.

Bregje Hofstede (1988) werd bekroond met de Hollands Maandblad Aanmoedigingsbeurs in de categorieën proza & essayistiek. In de ogen van de jury wist de laureaat haar diverse bijdragen aan de jaargang 2012 van Hollands Maandblad op drie overtuigende literaire fundamenten te grondvesten: ideeën, stijl en doorzettingsvermogen. Het is de jury niet ontgaan dat de laureaat ondanks, doch wellicht dankzij twee studies (Frans en Kunstgeschiedenis) die deels aan de Sorbonne en in Berlijn werden afgerond met het judicium cum laude, een bijzonder breed spectrum bestrijkt, dat reikt van dromerige fictie tot hard-boiled essayistiek. Vooral haar eersteling, het debuutverhaal over een al dan niet fictieve amour fou in de Parijse metro, waarbij de hartenklop samenvalt met het passeren van al die oh zo bekende ondergrondse stations, en haar laatsteling, een even wetenschappelijk als hartstochtelijk essay over de kosmopolitische kunstenaar en het multi-talent Alexander Alexeieff konden op unanieme bijval rekenen. De jury is ervan overtuigd dat deze laureaat nog van zich zal doen spreken, want zij heeft alles wat elke gewone sterveling zo graag zou willen hebben: intelligence, ténacité, promptitude et avant tout promesse et jeunesse. Vervuld van zowel ontzag als verwachtingen over haar schrijflust kent de jury Bregje Hofstede de Hollands Maandblad Aanmoedigingsbeurs in de categorieën proza & essayistiek toe.

Maxim Roozen (1991) werd bekroond met de Hollands Maandblad Schrijversbeurs. Hij is jong, in de ogen van de jury misschien wel benauwend jong, en toch is hij in zekere zin al gewassen door de literaire wateren die tegenwoordig zo vervaarlijk over de lage dijken van ons cultuurlandschap klotsen. Het is de jury niet ontgaan dat deze laureaat in 2009 op 17-jarige leeftijd een Wild Card wist te bemachtigen voor Write Now!-schrijfwedstrijd, die hij vervolgens zonder bloeddoping wist te winnen met een opmerkelijk verhaal dat hem meteen een pre-contract van een respectabele hoofdstedelijke uitgeverij voor een roman opleverde. Het is de jury evenmin ontgaan dat de schrijfster Maartje Wortel hem uitriep tot haar ‘jonge god’ en dat zij haar hartenkreet publiceerde nog voordat de laureaat buiten zijn vriendenkring bekend was. ‘Onthoud die naam,’ schreef zij over haar jonge god, ‘Voor nu en in de toekomst.’ Het kan dus geen toeval zijn dat het literaire debuut van deze laureaat, dat gewoon via de post in de brievenbus viel en eenmaal afgedrukt in Hollands Maandblad op de pagina stond met een verbluffende vanzelfsprekendheid alsof het altijd zo had moeten zijn. Overigens was er weinig vanzelfsprekends aan het verhaal van de laureaat, dat op treffende wijze het levensgevoel en het geestesleven van de hedendaagse jeugd wist te schetsen. De jury beseft dat de laureaat schrijven kan, de jury beseft ook dat zij de schouders van de laureaat thans belaadt met de verwachting dat hij een bijzonder talent is. Al met al leek het de redactieraad passend deze laureaat haar hoogste teken van waardering, ondersteuning en aanmoediging te verlenen, in de verwachting dat hij nog van zich zal doen spreken. Vandaar dat de jury de Hollands Maandblad Schrijversbeurs 2012/2013 toekent aan Maxim Roozen.

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Art & Literature News, Porcelijn, Esther, Porcelijn, Esther

Laatste rol

In memoriam Jeroen Willems (15-11-1962- 3-12-2012), acteur

Je speelt je laatste rol

je laatste wedstrijd en

het maakt niet uit of je

nu acteur of scheidsrechter

bent je speelt voor het

laatst ongeacht of je dood

gaat door wat vijftienjarige

jongens of een hartstilstand

werkt anders ook heel goed

er schuilt veel onrecht in

leven in elk mens zeker

twee wedstrijden en zo’n

vijfhonderd rollen het kan

voor iedereen vandaag nog

waar zijn dat je die laatste

wedstrijd speelt en dan

doodgetrapt wordt op het

veld je speelt een laatste rol

sterft op het hoogste podium.

Martin Beversluis

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Beversluis, Martin

Ton van Reen

DE MOORD XXXII

HET VERTREK VAN DE MELKER

‘Hoe laat is het?’ vroeg de melker. Waarom vroeg hij dat nu? Het was twee uur. De klok hing tegenover hem. Hij hoefde er alleen maar naar te kijken. Misschien durfde hij dat niet. Misschien was hij doodsbang. Je wist het nooit met de melker. Zijn ogen stonden te scheef. De laatste dagen dacht hij alleen maar aan zijn paard. Alsof hij het paard zelf gemaakt had uit klei. Zo gehecht was hij aan het beest.

Cherubijn lag als een zak in een hoek. Zijn hemd hing open. Eva woonde op zijn borst. Getatoeëerd op de lellen en vellen van zijn vergane spieren. Cherubijn moest al oud zijn, anders konden zijn spieren niet zo ver weggeteerd zijn onder zijn huid. Vroeger had hij veel gevochten. Hij had littekens over zijn hele lijf. Hij was er trots op. Hij peuterde er soms aan met een mes, omdat ze in elkaar schrompelden en er als huidplooien uitzagen.

Mijn hemd voelde aan als een dweil. Mijn rug was nat. Zweet en de kou van de angst. Angst kan je kil maken en stijf. Het was zoiets als de dood. Die kon zich ook zo in je vastgrijpen dat je uit elkaar viel als een rotte appel.

Alice was weg. Haar bloed zat op mijn huid en kleren. Het lag in een plas op de vloer. Haar kapotte kleren lagen in een hoek en her en der op het pad naar de deur. En tussen de verwilderde bloemen die stonden te wuiven en onze zuurstof opvraten.

Zouden we de schuld van de oorlog op de bloemen kunnen schuiven? Groengele bladeren die elkaar in de weg stonden, nooit ouder werden dan een halfjaar omdat ze elkaar zo nodig moesten opvreten? Waarom vraten de soldaten aan Alice? Waarom?

De marmot was ziek. Hij lag op een deken. Hij had aan het bloed gelikt. Besefte hij dat het bloedschande was? En dat hij nu gestenigd zou worden? Wie zou de marmot stenigen?

Ons gezin bestond nog uit vier personen. Vanavond nog uit drie. Ik wist zeker dat de melker zou vertrekken met het paard. En niet meer terug zou komen. Dan zou ons gezin nog uit drie man bestaan. Wie ging er dan het eerst dood? Cherubijn, ik of de marmot? Kende ik het spelletje nog? Koning Karel had geen brood en daarom sloeg hij een van zijn soldaten dood. Wie was koning Karel? Kon hij ons zo maar doodslaan? Was iemand van ons koning Karel? Was Cherubijn koning Karel? Was de marmot koning Karel? Was ik koning Karel?

Wat moesten we doen met Alices bloed? Iemand zou het moeten opdweilen. Ik kon het niet. Het was mijn eigen bloed. Alice was van mij. Dat was ze nog, ook al was ze dood.

(wordt vervolgd)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: - De moord

Richard Zoozmann

(1863-1934)

Der Tod und das Mädchen

Ich habe mich in deinen Reiz verliebt,

Der ohne Gleichnis ist und ohne Namen:

Welch schönes Haar! das, wie ein goldner Rahmen

Ein Heil’genbild, dein Angesicht umgibt.

Ich liebe dich. Vom ersten Tage an,

Der dich gesandt in dieses dunkle Leben,

Ließ ich dich meinen Flügelschlag umweben,

Bis ich dem Himmel heute dich gewann.

Ich bin der Tod. Erschrecke nicht: ich bin

Ein sanfter Engel, der dich sanft geleitet

Und unter dich die Schwingen hält gebreitet;

So trag’ ich dich zu Gottes Himmel hin.

Hier unten warst du eine Blume nur;

Ein Lenz schuf dich, ein Herbst läßt dich vergehen.

Zu ew’ger Blüte wirst du auferstehen

In Gottes winterloser Gartenflur.

Richard Zoozmann poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive Y-Z

James Joyce

(1882-1941)

After The Race

The cars came scudding in towards Dublin, running evenly like pellets in the groove of the Naas Road. At the crest of the hill at Inchicore sightseers had gathered in clumps to watch the cars careering homeward and through this channel of poverty and inaction the Continent sped its wealth and industry. Now and again the clumps of people raised the cheer of the gratefully oppressed. Their sympathy, however, was for the blue cars, the cars of their friends, the French.

The French, moreover, were virtual victors. Their team had finished solidly; they had been placed second and third and the driver of the winning German car was reported a Belgian. Each blue car, therefore, received a double measure of welcome as it topped the crest of the hill and each cheer of welcome was acknowledged with smiles and nods by those in the car. In one of these trimly built cars was a party of four young men whose spirits seemed to be at present well above the level of successful Gallicism: in fact, these four young men were almost hilarious. They were Charles Segouin, the owner of the car; Andre Riviere, a young electrician of Canadian birth; a huge Hungarian named Villona and a neatly groomed young man named Doyle. Segouin was in good humour because he had unexpectedly received some orders in advance (he was about to start a motor establishment in Paris) and Riviere was in good humour because he was to be appointed manager of the establishment; these two young men (who were cousins) were also in good humour because of the success of the French cars. Villona was in good humour because he had had a very satisfactory luncheon; and besides he was an optimist by nature. The fourth member of the party, however, was too excited to be genuinely happy.

He was about twenty-six years of age, with a soft, light brown moustache and rather innocent-looking grey eyes. His father, who had begun life as an advanced Nationalist, had modified his views early. He had made his money as a butcher in Kingstown and by opening shops in Dublin and in the suburbs he had made his money many times over. He had also been fortunate enough to secure some of the police contracts and in the end he had become rich enough to be alluded to in the Dublin newspapers as a merchant prince. He had sent his son to England to be educated in a big Catholic college and had afterwards sent him to Dublin University to study law. Jimmy did not study very earnestly and took to bad courses for a while. He had money and he was popular; and he divided his time curiously between musical and motoring circles. Then he had been sent for a term to Cambridge to see a little life. His father, remonstrative, but covertly proud of the excess, had paid his bills and brought him home. It was at Cambridge that he had met Segouin. They were not much more than acquaintances as yet but Jimmy found great pleasure in the society of one who had seen so much of the world and was reputed to own some of the biggest hotels in France. Such a person (as his father agreed) was well worth knowing, even if he had not been the charming companion he was. Villona was entertaining also, a brilliant pianist, but, unfortunately, very poor.

The car ran on merrily with its cargo of hilarious youth. The two cousins sat on the front seat; Jimmy and his Hungarian friend sat behind. Decidedly Villona was in excellent spirits; he kept up a deep bass hum of melody for miles of the road The Frenchmen flung their laughter and light words over their shoulders and often Jimmy had to strain forward to catch the quick phrase. This was not altogether pleasant for him, as he had nearly always to make a deft guess at the meaning and shout back a suitable answer in the face of a high wind. Besides Villona’s humming would confuse anybody; the noise of the car, too.

Rapid motion through space elates one; so does notoriety; so does the possession of money. These were three good reasons for Jimmy’s excitement. He had been seen by many of his friends that day in the company of these Continentals. At the control Segouin had presented him to one of the French competitors and, in answer to his confused murmur of compliment, the swarthy face of the driver had disclosed a line of shining white teeth. It was pleasant after that honour to return to the profane world of spectators amid nudges and significant looks. Then as to money, he really had a great sum under his control. Segouin, perhaps, would not think it a great sum but Jimmy who, in spite of temporary errors, was at heart the inheritor of solid instincts knew well with what difficulty it had been got together. This knowledge had previously kept his bills within the limits of reasonable recklessness, and if he had been so conscious of the labour latent in money when there had been question merely of some freak of the higher intelligence, how much more so now when he was about to stake the greater part of his substance! It was a serious thing for him.

Of course, the investment was a good one and Segouin had managed to give the impression that it was by a favour of friendship the mite of Irish money was to be included in the capital of the concern. Jimmy had a respect for his father’s shrewdness in business matters and in this case it had been his father who had first suggested the investment; money to be made in the motor business, pots of money. Moreover Segouin had the unmistakable air of wealth. Jimmy set out to translate into days’ work that lordly car in which he sat. How smoothly it ran. In what style they had come careering along the country roads! The journey laid a magical finger on the genuine pulse of life and gallantly the machinery of human nerves strove to answer the bounding courses of the swift blue animal.

They drove down Dame Street. The street was busy with unusual traffic, loud with the horns of motorists and the gongs of impatient tram-drivers. Near the Bank Segouin drew up and Jimmy and his friend alighted. A little knot of people collected on the footpath to pay homage to the snorting motor. The party was to dine together that evening in Segouin’s hotel and, meanwhile, Jimmy and his friend, who was staying with him, were to go home to dress. The car steered out slowly for Grafton Street while the two young men pushed their way through the knot of gazers. They walked northward with a curious feeling of disappointment in the exercise, while the city hung its pale globes of light above them in a haze of summer evening.

In Jimmy’s house this dinner had been pronounced an occasion. A certain pride mingled with his parents’ trepidation, a certain eagerness, also, to play fast and loose for the names of great foreign cities have at least this virtue. Jimmy, too, looked very well when he was dressed and, as he stood in the hall giving a last equation to the bows of his dress tie, his father may have felt even commercially satisfied at having secured for his son qualities often unpurchaseable. His father, therefore, was unusually friendly with Villona and his manner expressed a real respect for foreign accomplishments; but this subtlety of his host was probably lost upon the Hungarian, who was beginning to have a sharp desire for his dinner.

The dinner was excellent, exquisite. Segouin, Jimmy decided, had a very refined taste. The party was increased by a young Englishman named Routh whom Jimmy had seen with Segouin at Cambridge. The young men supped in a snug room lit by electric candle lamps. They talked volubly and with little reserve. Jimmy, whose imagination was kindling, conceived the lively youth of the Frenchmen twined elegantly upon the firm framework of the Englishman’s manner. A graceful image of his, he thought, and a just one. He admired the dexterity with which their host directed the conversation. The five young men had various tastes and their tongues had been loosened. Villona, with immense respect, began to discover to the mildly surprised Englishman the beauties of the English madrigal, deploring the loss of old instruments. Riviere, not wholly ingenuously, undertook to explain to Jimmy the triumph of the French mechanicians. The resonant voice of the Hungarian was about to prevail in ridicule of the spurious lutes of the romantic painters when Segouin shepherded his party into politics. Here was congenial ground for all. Jimmy, under generous influences, felt the buried zeal of his father wake to life within him: he aroused the torpid Routh at last. The room grew doubly hot and Segouin’s task grew harder each moment: there was even danger of personal spite. The alert host at an opportunity lifted his glass to Humanity and, when the toast had been drunk, he threw open a window significantly.

That night the city wore the mask of a capital. The five young men strolled along Stephen’s Green in a faint cloud of aromatic smoke. They talked loudly and gaily and their cloaks dangled from their shoulders. The people made way for them. At the corner of Grafton Street a short fat man was putting two handsome ladies on a car in charge of another fat man. The car drove off and the short fat man caught sight of the party.

“Andre.”

“It’s Farley!”

A torrent of talk followed. Farley was an American. No one knew very well what the talk was about. Villona and Riviere were the noisiest, but all the men were excited. They got up on a car, squeezing themselves together amid much laughter. They drove by the crowd, blended now into soft colours, to a music of merry bells. They took the train at Westland Row and in a few seconds, as it seemed to Jimmy, they were walking out of Kingstown Station. The ticket-collector saluted Jimmy; he was an old man:

“Fine night, sir!”

It was a serene summer night; the harbour lay like a darkened mirror at their feet. They proceeded towards it with linked arms, singing Cadet Roussel in chorus, stamping their feet at every:

“Ho! Ho! Hohe, vraiment!”

They got into a rowboat at the slip and made out for the American’s yacht. There was to be supper, music, cards. Villona said with conviction:

“It is delightful!”

There was a yacht piano in the cabin. Villona played a waltz for Farley and Riviere, Farley acting as cavalier and Riviere as lady. Then an impromptu square dance, the men devising original figures. What merriment! Jimmy took his part with a will; this was seeing life, at least. Then Farley got out of breath and cried “Stop!” A man brought in a light supper, and the young men sat down to it for form’s sake. They drank, however: it was Bohemian. They drank Ireland, England, France, Hungary, the United States of America. Jimmy made a speech, a long speech, Villona saying: “Hear! hear!” whenever there was a pause. There was a great clapping of hands when he sat down. It must have been a good speech. Farley clapped him on the back and laughed loudly. What jovial fellows! What good company they were!

Cards! cards! The table was cleared. Villona returned quietly to his piano and played voluntaries for them. The other men played game after game, flinging themselves boldly into the adventure. They drank the health of the Queen of Hearts and of the Queen of Diamonds. Jimmy felt obscurely the lack of an audience: the wit was flashing. Play ran very high and paper began to pass. Jimmy did not know exactly who was winning but he knew that he was losing. But it was his own fault for he frequently mistook his cards and the other men had to calculate his I.O.U.’s for him. They were devils of fellows but he wished they would stop: it was getting late. Someone gave the toast of the yacht The Belle of Newport and then someone proposed one great game for a finish.

The piano had stopped; Villona must have gone up on deck. It was a terrible game. They stopped just before the end of it to drink for luck. Jimmy understood that the game lay between Routh and Segouin. What excitement! Jimmy was excited too; he would lose, of course. How much had he written away? The men rose to their feet to play the last tricks. talking and gesticulating. Routh won. The cabin shook with the young men’s cheering and the cards were bundled together. They began then to gather in what they had won. Farley and Jimmy were the heaviest losers.

He knew that he would regret in the morning but at present he was glad of the rest, glad of the dark stupor that would cover up his folly. He leaned his elbows on the table and rested his head between his hands, counting the beats of his temples. The cabin door opened and he saw the Hungarian standing in a shaft of grey light:

“Daybreak, gentlemen!”

James Joyce: After the race

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Joyce, James, Joyce, James

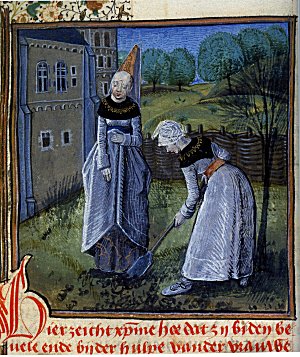

Christine de Pisan

(ca. 1364-1430)

Priez, dames et damoiselles

Priez, dames et damoiselles,

Pour les bons chevaliers vaillans

Qui, pour soustenir voz querelles,

Mettent leurs corps et leurs vaillans:

Que ja Dieu ne leur soit faillans,

Ains leur doint honneur et victoire

Encontre tous leur assaillans,

Si qu’a tousjours en soit memoire.

Qui l’escu vert aux dames belles

Portent sanz estre deffaillans,

Pour demonstrer que l’onneur d’elles

Veulent, aux espées taillans,

Garder contre leur mauvueillans.

Si devez prier Dieu de gloire

Que priz et loz soient cueillans,

Si qu’a tousjours en soit memoire.

Du bon Torsay bonnes nouvelles

Avons, com preux et traveillans

Les armes Obissecourt, celles

Facent joye a ses bienvueillans;

Castelbayart qui est veillans

A poursuivre armes, chose est voire,

A honneur en soit hors saillans,

Si qu’a tousjours en soit memoire.

Or priez Dieu a yeulx moillans,

Qu’on die d’eulx si bonne hystoire,

Que chascun en soit merveillans,

Si qu’a tousjours en soit memoire.

Christine de Pisan poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Pisan, Christine de

Christine de Pisan

(ca. 1364-1430)

Il me semble qu’il a cent ans

Il me semble qu’il a cent ans

Que mon ami de moy parti!

Il ara quinze jours par temps,

Il me semble qu’il a cent ans!

Ainsi m’a anuié le temps,

Car depuis lors qu’il departi

Il me semble qu’il a cent ans!

Christine de Pisan poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Pisan, Christine de

![]()

Languit in de vonk (Rustdag)

Hij voelt zich nu jonger dan gisteren.

Er mag geen schilfer van de bloedlijn,

vindt hij. In zijn hoofd een rare kalmte

vol gaten. En het ongeloof dat dit dorp

stil zal wezen als zij er straks vertrekken.

Met zijn snelheid laat hij langzaam iets

achter in de dikke boeken waarin hij ooit

graag bladeren zal. Het is hard te weten

dat je dan slechts de schim van jezelf

zult zijn, van de kampioen van vroeger

die je vandaag nog aan het worden bent.

Dat je ooit op de krater van jezelf terug

zult blikken op de volheid die toen, en

het kabaal dat daarna. Later zal zijn zoon

hem vragen hoe het was, maar nu is die er

nog niet. Leg je dus maar even languit

in de vonk van voorlopig geluk. Allez.

Bert Bevers

uit Geelzucht III, De Letterloods, Puyvelde, 2012

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Bevers, Bert

Christine de Pisan

(ca 1364-1430)

BALLAD

Command of me, my Lady and my queen,

All thy good pleasure, as I were thy slave,

Which I shall do with glad and humble mien

That whatsoe’er thou willest, thou may’st have.

I owe no less

Being bound thereto for so great pleasantness,

More than to other lovers may betide:

For sweeter are thy gifts than all beside.

Thy love delivered me from dule and teen,

All that was needful to my soul it gave:

Is there not here in truth good reason seen

Thy love should rule the heart thy love did save?

Ah, what mistress

So guerdoneth her servant with largess

Of love’s delight? The rest have I denied,

For sweeter are thy gifts than all beside.

Since such a harvest of reward I glean,

Love in my heart hath risen like a wave:

Thy slave am I, as I thy slave have been,

While life shall last. Ah, damsel bright and brave,

Sweet patroness

Of spirit and strength, and lady of noblesse,

All other comfort doth my heart deride,

For sweeter are thy gifts than all beside.

Most dear princess

Of joy thou art the fount, as I confess:

I thirst no longer, but am satisfied,

For sweeter are thy gifts than all beside.

Christine de Pisan poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Pisan, Christine de

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature