Fleurs du Mal Magazine

‘Meeslepend en tot het einde toe spannend!’

Jonge Jury 2013

Wie wint de Prijs van de Jonge Jury 2013? In september gingen duizenden jongeren tussen 12 en 15 jaar in Nederland van start met het lezen voor de Jonge Jury. Tot 1 maart hebben zij de kans een stem uit te brengen op hun favoriete boek.

Hoewel alle jeugdboeken die verschenen in 2011 kans maken op de prijs, koos een onafhankelijke selectiecommissie – Jasper Leibbrand (docent), Geertje Plug (docent), John Schrijnemakers (Speelboek Amersfoort, oprichter De Leesfabriek), Ellen Stinis (docent) en Richard de Wal (jeugdbibliothecaris) – twintig kerntitels. Verfrissende en uitdagende uitgaven die bijdragen aan het leesenthousiasme van jongeren.

Kerntitels Jonge Jury 2013

Danielle Bakhuis – Wraak

Caja Cazemier – Iets van mij

Caja Cazemier & Martine Letterie – Familiegeheim

Marian De Smet – Geen bereik

Theo & Marianne Hoogstraaten – (ff) Out!

Enne Koens – Vogel

Gill Lewis – Kulanjango, mijn vogelvriend

Endre Lund Eriksen – Super

Andy Mulligan – Trash

Tamsyn Murray – Het geestige leven van Lucy Shaw

Annabel Pitcher – Mijn zus woont op de schoorsteenmantel

Ursula Poznanski – Erebos

Anna van Praag – Vossenjacht

Cees van Roosmalen – Kracht

Rob Ruggenberg – IJsbarbaar

Aline Sax en Caryl Strzelecki – De kleuren van het getto

Simon Scarrow – Gladiator, vechten voor vrijheid

Ruta Sepetys – Schaduwliefde

Mel Wallis de Vries – Verstrikt

Anna Woltz & Vicky Janssen – Meisje van Mars

De Jonge Jury is het grootste landelijke leesbevorderingsproject voor jongeren in klas 1 t/m 3 van het voortgezet onderwijs. In totaal bereikte de Jonge Jury vorig jaar 65.000 jongeren. De vijf boeken die de meeste stemmen ontvangen, worden genomineerd voor de Prijs van de Jonge Jury. Tijdens de Dag van de Jonge Jury – een uniek eendaags literair festival op 17 april 2013 in het AFAS Circustheater te Scheveningen – wordt de winnaar bekendgemaakt.

Ook op school, in de bibliotheek en boekhandel is deelname aan dit grootste landelijke leesbevorderingsproject mogelijk. Een Jonge Jurypakket bestaat uit posters, magazines met leestips en een handboek om de Jonge Jury te integreren in de lessen Nederlands.

≡ Informatie website: www.jongejury.nl

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Art & Literature News, FICTION & NON-FICTION - books, booklovers, lit. history, biography, essays, translations, short stories, columns, literature: celtic, beat, travesty, war, dada & de stijl, drugs, dead poets

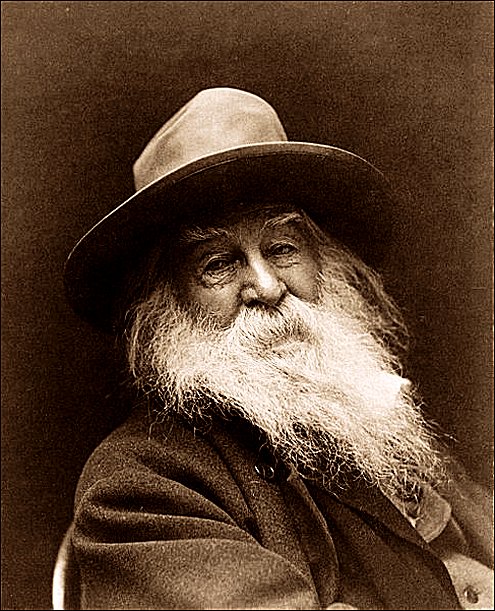

Walt Whitman

(1819–1892)

A Song

Come, I will make the continent indissoluble;

I will make the most splendid race the sun ever yet shone upon;

I will make divine magnetic lands,

With the love of comrades,

With the life-long love of comrades.

I will plant companionship thick as trees along all the rivers of

America, and along the shores of the great lakes, and all over

the prairies;

I will make inseparable cities, with their arms about each other’s

necks;

By the love of comrades,

By the manly love of comrades.

For you these, from me, O Democracy, to serve you, ma femme! 10

For you! for you, I am trilling these songs,

In the love of comrades,

In the high-towering love of comrades.

Walt Whitman poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive W-X, Whitman, Walt

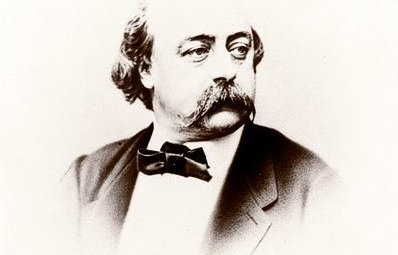

Gustave Flaubert

(1821-1880)

DICTIONNAIRE DES IDÉES REÇUES (E)

E

EAU: L’eau de Paris donne des coliques. L’eau de mer soutient pour nager. L’eau de Cologne sent bon.

ÉBÉNISTE: Ouvrier qui travaille surtout l’acajou.

ÉCHAFAUD: S’arranger quand on y monte pour prononcer quelques mots éloquents avant de mourir.

ÉCHARPE: Poétique.

ÉCHECS (jeu des): Image de la tactique militaire. Tous les grands capitaines y étaient forts. Trop sérieux pour un jeu, trop futile pour une science.

ÉCHO: Citer ceux du Panthéon et du pont de Neuilly.

ÉCLECTISME: Tonner contre comme étant une philosophie immorale.

ÉCOLES: Polytechnique, rêve de toutes les mères (vieux). Terreur du bourgeois dans les émeutes quand il apprend que ‘Ecole Polytechnique sympathise avec les ouvriers (vieux). Dire simplement «l’Ecole» fait accroire qu’on y a été. A Saint-Cyr: jeunes gens nobles. A l’Ecole de Médecine: tous exaltés. A l’Ecole de Droit: jeunes gens de bonne famille.

ÉCONOMIE: Toujours précédé de «ordre» . Mène à la fortune. Citer l’anecdote de Laffitte ramassant une épingle dans la cour du banquier Perrégaux.

ÉCONOMIE POLITIQUE: Science sans entrailles.

ÉCREVISSE: Marche à reculons. Toujours appeler les réactionnaires des écrevisses.

ÉCRIRE: Currente calamo, c’est l’excuse pour les fautes de style ou d’orthographe.

ÉCRIT, BIEN ÉCRIT: Mots de portier, pour désigner les romans-feuilletons qui les amusent.

ÉCRITURE: Une belle écriture mène à tout. Indéchiffrable: signe de science. Ex.: les ordonnances des médecins.

ÉCUME DE MER: Se trouve dans la terre. On en fait des pipes.

ÉDILES: Tonner contre à propos du pavage des rues. «A quoi songent nos édiles?»

ÉGOÏSME: Se plaindre de celui des autres et ne pas s’apercevoir du sien.

ÉLÉPHANTS: Se distinguent par leur mémoire, et adorent le soleil.

ÉMAIL: Le secret en est perdu.

EMBONPOINT: Signe de richesse et de fainéantise.

ÉMIGRÉS: Gagnaient leur vie à donner des leçons de guitare et à faire la salade.

ÉMIR: Ne se dit qu’en parlant d’Abd-el-Kader.

EMPIRE: «L’Empire c’est la paix.» (Napoléon III.)

ENCEINTE: Fait bien dans les discours officiels: «Messieurs, dans cette enceinte…»

ENCRIER: Se donne en cadeau à un médecin.

ENCYCLOPÉDIE: En rire de pitié, comme étant un ouvrage rococo, et même tonner contre.

ENFANTS: Affecter pour eux une tendresse lyrique, quand il y a du monde.

ENGELURE: Signe de santé: vient de s’être chauffé quand on avait froid.

ENTERREMENT: A propos du défunt: «Et dire que je dînais avec lui il y a huit jours!» S’appelle obsèques quand il s’agit d’un général, enfouissement quand c’est celui d’un philosophe.

ENTHOUSIASME: Ne peut être provoqué que par le retour des cendres de l’Empereur. Toujours impossible à décrire, et pendant deux colonnes le journal ne parle que de ça.

ENTRACTE: Toujours trop long.

ENVERGURE: Se disputer sur la prononciation du mot.

ÉPACTE, NOMBRE D’OR, LETTRE DOMINICALE: Sur les calendriers, on ne sait pas ce que c’est.

ÉPARGNE (Caisse d’): Occasion de vol pour les domestiques.

ÉPÉE: On ne connaît que celle de Damoclès. Regretter le temps où on en portait. «Brave comme une épée.» Quelquefois elle n’a jamais servi.

ÉPÉRONS: Font bien à une paire de bottes.

ÉPICURE: Le mépriser.

ÉPINARDS: Sont le balai de l’estomac. Ne jamais rater la phrase célèbre de Prudhomme: «Je ne les aime pas, j’en suis bien aise, car si je les aimais, j’en mangerai et je ne puis pas les souffrir.» (Il y en a qui trouveront cela parfaitement logique et qui ne riront pas).

ÉPOQUE (la nôtre): Tonner contre elle. Se plaindre de ce qu’elle n’est pas poétique. L’appeler époque de transition, de décadence.

ÉPUISEMENT: Toujours prématuré.

ÉQUITATION: Bon exercice pour faire maigrir. Ex.: tous les soldats de cavalerie sont maigres. Bon exercice pour engraisser. Ex.: tous les officiers de cavalerie ont un gros ventre. «Il monte à cheval comme un vrai centaure.»

ÈRE (des révolutions): Toujours ouverte puisque chaque nouveau gouvernement promet de la fermer.

ÉRECTION: Ne se dit qu’en parlant des monuments.

ÉRUDITION: La mépriser comme étant la marque d’un esprit étroit.

ESCRIME: Les maîtres d’escrime savent des bottes secrètes.

ESCROC: Toujours du grand monde (v. espion).

ESPION: Toujours du grand monde (v. escroc).

ESPLANADE: Ne se voit qu’aux Invalides.

ESPRIT: Toujours suivi d’étincelant. Court les rues. Les beaux esprits se rencontrent.

ESTOMAC: Toutes les maladies viennent de l’estomac.

ÉTAGÈRE: Indispensable chez une jolie femme.

ÉTALON: Toujours vigoureux. Une femme doit ignorer la différence qu’il y a entre un étalon et un cheval.

ÉTÉ: Toujours exceptionnel (v. hiver).

ÉTERNUEMENT: Après qu’on a dit: «Dieu vous bénisse» , engager une discussion sur l’origine de cet usage.

ÉTERNUER: C’est une raillerie spirituelle de dire: le russe et le polonais ne se parlent pas, ça s’éternue.

ÉTOILE: Chacun a la sienne, comme l’Empereur.

ÉTRANGER: Engouement pour tout ce qui vient de l’étranger, preuve de l’esprit libéral. Dénigrement de tout ce qui n’est pas français, preuve de patriotisme.

ÉTRENNES: S’indigner contre.

ÉTRUSQUE: Tous les vases anciens sont étrusques.

ÉTUDIANT: Portent tous des bérets rouges, des pantalons à la hussarde, fumant la pipe dans la rue et n’étudie pas.

ÉTYMOLOGIE: Rien de plus facile à trouver avec le latin et un peu de réflexion.

EUNUQUE: N’a jamais d’enfants… Fulminer contre les castrats de la chapelle Sixtine.

ÉVACUATIONS: Les évacuations sont souvent copieuses et toujours de mauvaise nature.

ÉVANGILES: Livres divins, sublimes, etc.

ÉVIDENCE: Vous aveugle, quand elle ne crève pas les yeux.

EXASPÉRATION: Constamment à son comble.

EXCEPTION: Dites qu’elle confirme la règle. Ne vous risquez pas à expliquer comment.

EXÉCUTIONS CAPITALES: Se plaindre des femmes qui vont les voir.

EXERCICE: Préserve de toutes les maladies: toujours conseiller d’en faire.

EXPIRER: Ne se conjugue qu’à propos des abonnements de journaux.

EXPOSITION: Sujet de délire du XIXe siècle.

EXTINCTION: Ne s’emploie qu’avec paupérisme.

EXTIRPER: Ce verbe ne s’emploie que pour les hérésies et les cors aux pieds.

Gustave Flaubert

DICTIONNAIRE DES IDÉES REÇUES (E)

(Oeuvre posthume: publication en 1913)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: - Dictionnaire des idées reçues, DICTIONARY OF IDEAS

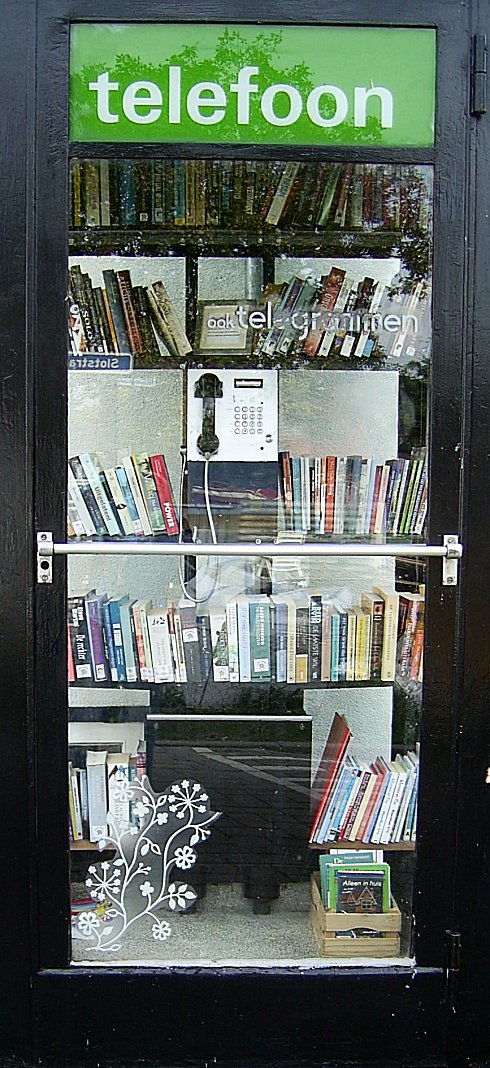

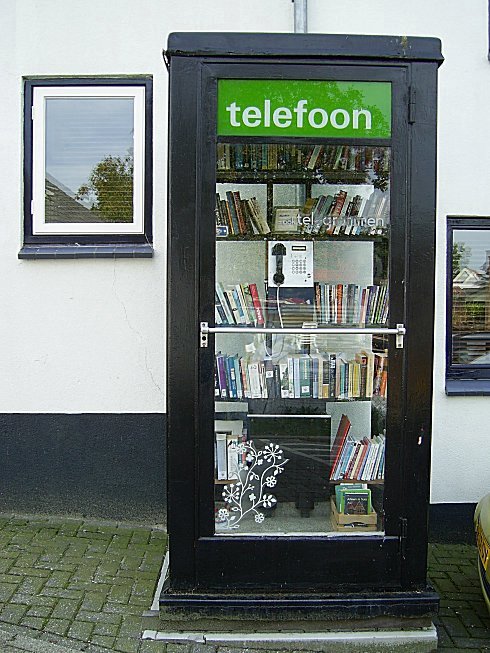

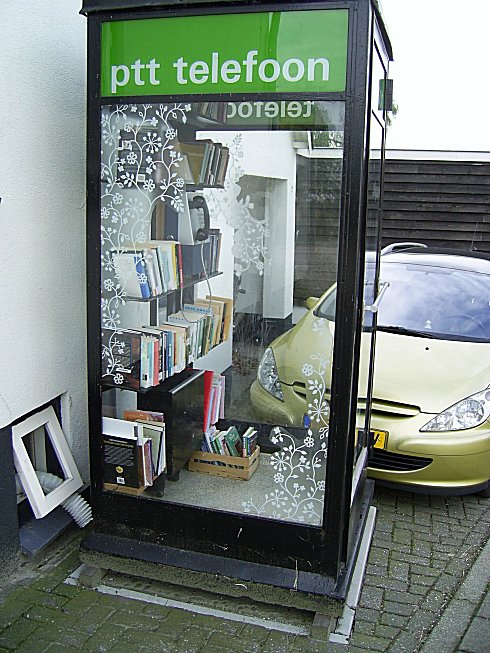

Gratis ruilbibliotheek van Jordi en Michelle de Groot

in een telefooncel

hoek van de Havendijk en Slotstraat te Beesd.

photo fleurdumal

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, - Guerilla Libraries

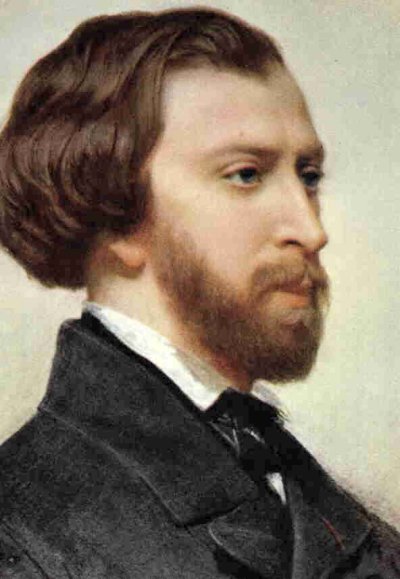

George Sand

(1804-1876)

Lettre envoyée par Aurore Dupin

dite George SAND

à Alfred de MUSSET

Je suis très émue de vous dire que j’ai

bien compris l’autre soir que vous aviez

toujours une envie folle de me faire

danser. Je garde le souvenir de votre

baiser et je voudrais bien que ce soit

là une preuve que je puisse être aimée

par vous. Je suis prête à vous montrer mon

affection toute désintéressée et sans cal-

cul, et si vous voulez me voir aussi

vous dévoiler sans artifice mon âme

toute nue, venez me faire une visite.

Nous causerons en amis, franchement.

Je vous prouverai que je suis la femme

sincère, capable de vous offrir l’affection

la plus profonde comme la plus étroite

amitié, en un mot la meilleure preuve

que vous puissiez rêver, puisque votre

âme est libre. Pensez que la solitude où j’ha-

bite est bien longue, bien dure et souvent

difficile. Ainsi en y songeant j’ai l’âme

grosse. Accourez donc vite et venez me la

faire oublier par l’amour où je veux me

mettre

George Sand (1835)

NB : A vous de découvrir l’érotisme caché.

Relisez-la en sautant les lignes paires

La réponse d’Alfred de Musset

Quand je mets à vos pieds un éternel hommage,

Voulez-vous qu’un instant je change de visage ?

Vous avez capturé les sentiments d’un coeur

Que pour vous adorer forma le créateur.

Je vous chéris, amour, et ma plume en délire

Couche sur le papier ce que je n’ose dire.

Avec soin de mes vers lisez les premiers mots,

Vous saurez quel remède apporter à mes maux.

Alfred de Musset

La réponse de George Sand

Cette insigne faveur que votre coeur réclame

Nuit à ma renommée et répugne à mon âme.

George Sand poetry & prose

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive S-T, George Sand, Musset, Alfred de

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (31)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926). The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator by Luigi Pirandello. Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK VI

4

The villa.

Was this it? Is it possible that this was it?

And yet, there was nothing altered about it, or very little. Only that gate, a little higher, that pair of pillars, a little higher, replacing the little pillars of the old days, from one of which Grandfather Carlo had had the marble tablet with his name on it torn down.

But could this new gate have changed so completely the whole appearance of the old villa.

I saw that it was the same house, and it seemed to me impossible that it could be; I saw that it had remained much the same; why then did it appear a different house?

What a tragedy! The memory that seeks to live again, and cannot find its way among places that seem changed, that seem different, because our sentiments have changed, our sentiments are different. And yet I imagined that I had come hurrying to the villa with the sentiments of those days, the heart of long ago!

There it is. Knowing quite well that places have no other life, no other reality than that which we bestow on them, I saw myself obliged to admit with dismay, with infinite regret: “How I have changed!” The reality now is this. Something different.

I rang the bell. A different sound. But now I no longer knew whether this were due to some change in myself or to there being a different bell. How depressing!

There appeared an old gardener, without a coat, his shirt sleeves rolled up to the elbows, with a watering-can in his hand and a brimless hat perched on the crown of his head like a priest’s biretta.

“Donna Rosa Mirelli?”

“Who?”

“Is she dead?”

“Who do you mean?”

“Donna Rosa….”

“Ah, you want to know if she’s dead? How should I know?”

“She doesn’t live here any longer?”

“I don’t know what Donna Rosa you’re talking about. She doesn’t live here. It’s Pèrsico lives here, Don Filippo, the Cavaliere.”

“Has he a wife? Donna Duccella?”

“No, Sir. He’s a widower. He lives in town.”

“Then there’s no one living here?”

“There’s myself here, Nicola Tavuso, the gardener.”

The flowers in the borders on either side of the path from the gate to the house, red, yellow, white, hung motionless like discs of enamel in the limpid, silent air, dripping still from their recent bath. Flowers born yesterday, but upon those old borders. I looked at them: they disconcerted me; they said that it really was Tavuso who was living there now, as far as they were concerned, that he watered them well every morning, and that they were grateful to him for it: fresh, scentless, smiling with all those drops of water.

Fortunately, there appeared on the scene an old peasant woman, all breast and belly and hips, enormous under a big basket of greenstuff, with one eye shut, imprisoned beneath its swollen red lid, and the other keenly alert, clear, sky-blue, glazed with tears.

“Donna Rosa? Eh, the old mistress…. Many’s the long year since she left here…. Alive, yes, Sir, why not, poor soul? An old woman now… with the grandchild, yes, Sir, … Donna Duccella, yes, Sir…. Good folk! All for God…. No use for this world, or anything. … The house here they sold, yes, Sir, years ago, to Don Filippo the ‘surer’….”

“Pèrsico, the Cavaliere.”

“Go on, Don Nico, everyone knows Don Filippo! Now, Sir, you come along with me, and I’ll take you to Donna Rosa’s, next door to the New Church.”

Before leaving it, I took a final look at the villa. There was nothing left of it now; all of a sudden, nothing left; as though in a moment a cloud had passed from before my eyes. There it was: poverty-stricken, old, empty… nothing left! And in that case, perhaps,… Granny Rosa, Duccella…. Nothing left, of them either? Phantoms of a dream, my sweet phantoms, my dear phantoms, and nothing more!

I felt chilled. A bare, dull, icy hardness. That stout peasant’s words: “Good folk! All for God…. No use for this world….” I could feel the Church in them: hard, bare, icy. Across those green fields that smiled no longer…. But then?

I allowed myself to be led away. I cannot say what long account followed of that Don Filippo, who was aptly named ‘surer’, because… a never-ending because… the old Government … not him, no, his father… a man of God too, he was, but… his father, or so the story went, at least. And with my weariness, in my weariness, as I went, all those impressions of a sordid reality, hard, bare, icy,… a donkey covered in flies, that refused to move, the squalid road, a crumbling wall, the fetid odour of the stout woman…. Oh, what a temptation to dash to the station and take the train home again! Twice, three times, I was on the point of doing it; I checked myself; said to myself: “Let us see!”

A narrow stair, filthy, damp, almost in pitch darkness; and the old woman shouting to me from below:

“Straight on, keep straight on…. The second floor…. The bell is broken, Sir…. Knock loud; she doesn’t hear; knock loud.”

As though I were deaf too…. “Here?” I said to myself as I climbed the stair. “How have they come down to this? Lost all their money? Perhaps, two women by themselves…. That Don Filippo….”

On the landing of the second floor, two old doors, low in the lintel, freshly painted. By one hung the broken cord of its bell. The other had none. This one or that? I knocked first at this one, loud, with my fist, once, twice, thrice. I tried to pull the bell of the other: it did not ring. Was it this one, then? I knocked at it, loud, three times, four times…. No answer! But how in the world? Was Duccella deaf too? Or was she not living with her grandmother? I knocked again, more loudly. I was turning to go, when I heard on the stair the heavy step and breathing of somebody coming up. A short, thickset woman, in one of those garments that signify devotion, with the penitential cord round her waist: a coffee-coloured garment, of devotion to Our Lady of Mount Carmel. Over her head and shoulders a ‘spagnoletta’, of black lace; in her hand, a fat prayer-book and the key of the house.

She stopped on the landing and looked at me with pale, lifeless eyes from a fat white face ending in a flaccid chin: on her upper lip, here and there, at the corners of her mouth, a few hairs sprouted. Duecella.

I had had enough; I wished only to make my escape! Ah, if only she had remained with that apathetic, stupid air with which she stopped short in front of me, still a little breathless, on the landing! But no: she wanted to entertain me, she wanted to be polite–she, now, like that–with those eyes that were no longer hers, with that fat, colourless nun’s face, with that short, stout body, and a voice, a voice and a kind of smile which I did not recognise: entertainment, compliments, ceremonies, as though I were shewing her a great condescension; and she was absolutely determined that I should come in and see her grandmother, who would be so delighted at the honour… why, yes, why, yes…. “Step inside, please, step inside….”

To remove her from my path I would have given her a shove, even at the risk of sending her flying downstairs! What a flabby horror! What an object! That deaf old woman, doddering with age, without a tooth in her head, with her pointed chin that protruded horribly towards the tip of her nose, chewing and mumbling, and her pallid tongue shewing between her flaccid, wrinkled lips, and those huge spectacles, monstrously enlarging her sightless eyes, scarred by an operation for cataract, between their sparse lashes, long as the feelers of an insect!

“You have made a position for yourself.” (With the soft Neapolitan z–‘posi-szi-o-ne’.)

She could think of nothing else to say to me.

I made my escape without its ever having occurred to me for a moment to suggest the plan for which I had come. What was I to say? What was there to do? Why ask them to tell me their story? If they had really fallen into poverty, as might be supposed from the appearance of the house? Perfectly content with everything, stolid and happy with God! Oh, what a horrible thing faith is! Duccella, the blushing flower… Granny Rosa, the garden of the villa with its jasmines….

In the train, I felt as though I were rushing towards madness, through the night. In what world was I? My travelling companion, a man of middle age, dark, with oval eyes, like discs of enamel, and hair that gleamed with oil, he belonged certainly to this world; firm and well established in the consciousness of his own calm and well cared for beastliness, he understood it all to perfection, without worrying about anything; he knew quite well all that it concerned him to know, where he was going, why he was travelling, the house at which he would arrive, the supper that was being prepared for him. But I? Was I of the same world? His journey and mine… his night and mine…. No, I had no time, no world, no anything. The train was his; he was travelling in it. How on earth did I come to be travelling in it also? What was I doing in the world in which he lived? How, in what respect was this night mine, when I had no means of living it, nothing to do with it? He had his night and all the time he wanted, that middle-aged man who was now twisting his neck about with signs of discomfort in his immaculate starched collar. No, no world, no time, nothing: I stood apart from everything, absent from myself and from life; and no longer knew where I was nor why I was there. Images I carried in me, not my own, of things and people; images, aspects, faces, memories of people and things which had never existed in reality, outside me, in the world which that gentleman saw round him and could touch. I had thought that I saw them, and could touch them also, but no, they were all imagination! I had never found them again, because they had never existed: phantoms, a dream…. But how could they have entered my mind? From where? Why? Was I there too, perhaps, then? Was there an I there then that now no longer existed? No; the middle-aged gentleman opposite to me told me, no: that other people existed, each in his own way and with his own space and time: I, no, I was not there; albeit, not being there, I should have found it hard to say where I really was and what I was, being thus without time or space.

I no longer understood anything. And I understood nothing when, arriving in Rome and coming to the house, about ten o’clock at night, I found in the dining-room, as gay as though nothing had happened, as though a new life had begun during my absence, Fabrizio Cavalena, a Doctor once more and restored to the bosom of his family, Aldo Nuti, Signorina Luisetta and Signora Nene, sitting round the table.

How? Why? What had happened?

I could not get rid of the impression that they were sitting there, gay and reconciled to one another, to make a fool of me, to reward me with the sight of their gaiety for the trouble that I had taken on their behalf; not only this, but that, knowing the state of mind in which I should return from the expedition, they had clubbed together to confound me utterly, making me find here also a reality such as I should never have expected.

More than any of the rest she, Signorina Luisetta, filled me with scorn, Signorina Luisetta who was impersonating Duccella in love, that Duccella, the blushing flower, of whom I had so often spoken to her! I would have liked to shout in her face how I had found her that afternoon, down at Sorrento, that Duccella, and to bid her give up this play-acting, which was an unworthy and grotesque contamination! And he too, the young man, who seemed by a miracle to be the same young man of years ago, I would have liked to shout in his face how and where I had found Duccella and Granny Rosa.

But good souls all of you! Down there, those two poor women, happy in God, and you happy here in the devil! Dear Cavalena, why yes, changed back not merely into a Doctor, but into a boy, a bridegroom, sitting by his bride! No, thank you: there is no place for me among you: don’t get up; don’t disturb yourselves: I am neither hungry nor thirsty! I can do without everything, I can. I have wasted upon you a little of what is of no use to me; you know it; a little of that heart which is of no use to me; because to me only my hand is of use: there is no need, therefore, to thank me! Indeed, you must excuse me if I have disturbed you. The fault is mine, for trying to interfere. Keep your seats, don’t get up, good night.

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (31)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: -Shoot!, Archive O-P, Pirandello, Luigi

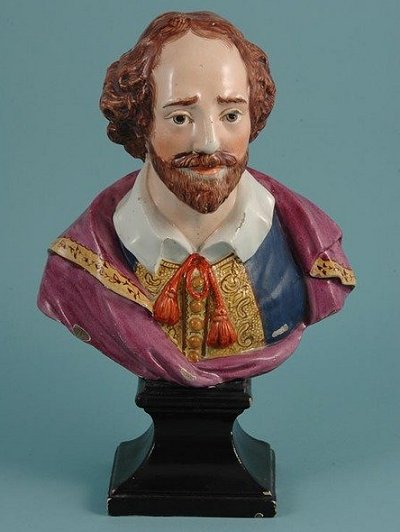

William Shakespeare

Sonnet 145 (1)

Those lips that Love’s own hand did make,

Breathed forth the sound that said ‘I hate’

To me that languished for her sake:

But when she saw my woeful state,

Straight in her heart did mercy come,

Chiding that tongue that ever sweet,

Was used in giving gentle doom:

And taught it thus anew to greet:

‘I hate’ she altered with an end,

That followed it as gentle day,

Doth follow night who like a fiend

From heaven to hell is flown away.

‘I hate’ from hate away she threw,

And saved my life saying ‘not you’.

Die mond, door Liefde zelf bedacht,

Blies een geluid, dat sprak ‘ik haat’

Tot mij, die kwijnend naar haar smacht.

Maar, ziende op mijn droeve staat,

Beving genade prompt haar hart;

Boos op die tong, altijd zo zoet,

Die mild verdoeming was gestart,

Dicteerde z’ hem een nieuwe groet:

Ze gaf ‘Ik haat’ een ander slot,

Dat volgt zoals een milde dag

Volgt op een nacht die als anti-god

Uit d’ hemel helwaarts vluchten mag,

Haat in ‘ik haat’ verwierp ze gauw,

En spaarde mij met haar ‘niet jou’.

Vertaling Cornelis W. Schoneveld (oktober 2012)

[1] Het opmerken waard is, dat dit van Shakespeare’s 154 sonnetten het enige is dat acht letergrepen per regel telt, in plaats van de 10 welhaast voorgeschreven door gehele Engelse sonnet traditie heen.

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Shakespeare

![]()

In Memoriam Raoul De Keyser (1930 – 2012)

Op 6 oktober is in Deinze Raoul De Keyser, een van de belangrijkste Belgische abstracte schilders, overleden. Hij was 82 jaar. De Keyser werkte sinds de jaren 60 aan een persoonlijk en subtiel oeuvre dat niet in een vaste categorie kan worden ondergebracht.

In het begin van zijn carrière was De Keyser een belangrijk vertegenwoordiger van de Nieuwe Visie, waarbij herkenbare motieven uit het dagelijks leven worden herleid tot kleurvlakken en lijnen. Samen met o.a. Roger Raveel beschilderde hij in die periode de kelders van het kasteel van Beervelde in de buurt van Gent.

Vanaf de jaren 70 wordt zijn werk steeds abstracter, al bleef het gebaseerd op motieven uit zijn omgeving. Hij raakte bekend met schilderijen die stukjes voetbalveld tonen: groene vlakken met krijtlijnen. Over de man die de krijtlijnen kalkte, zei hij: “Dat is mijn collega. Hij schildert, net als ik.”

Voetbalvelden, maar ook andere sporttaferelen inspireerden De Keyser: hij volgde jarenlang sportwedstrijden als correspondent voor de schrijvende pers. “Ik ben aandachtig voor wat het toeval mij brengt”, zei hij over zijn thema’s.

Later koos hij voor levendige en erg kleurrijke doeken. “Een collega zei ooit tegen mij: gij zijt een verver, ik ben een schilder”, vertelde hij een paar jaar geleden in een portret in het programma “Goudvis”. “Ken je het verschil? Verven is een kleur geven. Schilderen is meer doordacht.”

Raoul De Keyser had vorig jaar nog een tentoonstelling in de Lokettenzaal van het Vlaams Parlement. Zijn werk is te zien in binnen- en buitenlandse musea. De Keyser nam ook deel aan Documenta in Kassel en de Biënnale van Venetië.

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Exhibition Archive, In Memoriam

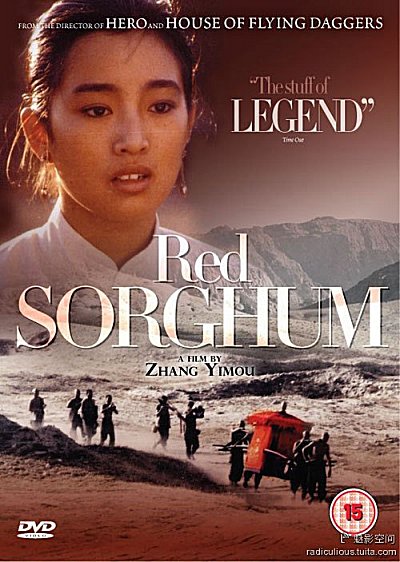

The Nobel Prize in Literature 2012

Mo Yan

Born: 1955, Gaomi, China

Lives still in China

Prize motivation: “who with hallucinatory realism merges folk tales, history and the contemporary”

Biobibliographical notes

Mo Yan (a pseudonym for Guan Moye) was born in 1955 and grew up in Gaomi in Shandong province in north-eastern China. His parents were farmers. As a twelve-year-old during the Cultural Revolution he left school to work, first in agriculture, later in a factory. In 1976 he joined the People’s Liberation Army and during this time began to study literature and write. His first short story was published in a literary journal in 1981. His breakthrough came a few years later with the novella Touming de hong luobo (1986, published in French as Le radis de cristal 1993).

In his writing Mo Yan draws on his youthful experiences and on settings in the province of his birth. This is apparent in his novel Hong gaoliang jiazu (1987, in English Red Sorghum 1993). The book consists of five stories that unfold and interweave in Gaomi in several turbulent decades in the 20th century, with depictions of bandit culture, the Japanese occupation and the harsh conditions endured by poor farm workers. Red Sorghum was successfully filmed in 1987, directed by Zhang Yimou. The novel Tiantang suantai zhi ge (1988, in English The Garlic Ballads 1995) and his satirical Jiuguo (1992, in English The Republic of Wine 2000) have been judged subversive because of their sharp criticism of contemporary Chinese society.

Fengru feitun (1996, in English Big Breasts and Wide Hips 2004) is a broad historical fresco portraying 20th-century China through the microcosm of a single family. The novel Shengsi pilao (2006, in English Life and Death are Wearing Me Out 2008) uses black humour to describe everyday life and the violent transmogrifications in the young People’s Republic, while Tanxiangxing (2004, to be published in English as Sandalwood Death 2013) is a story of human cruelty in the crumbling Empire. Mo Yan’s latest novel Wa (2009, in French Grenouilles 2011) illuminates the consequences of China’s imposition of a single-child policy.

Through a mixture of fantasy and reality, historical and social perspectives, Mo Yan has created a world reminiscent in its complexity of those in the writings of William Faulkner and Gabriel García Márquez, at the same time finding a departure point in old Chinese literature and in oral tradition. In addition to his novels, Mo Yan has published many short stories and essays on various topics, and despite his social criticism is seen in his homeland as one of the foremost contemporary authors.

A selection of major works in Chinese

Touming de hong luobo, 1986

Hong gaoliang jiazu, 1987

Baozha, 1988

Tiantang suantai zhi ge, 1988

Huanle shisan zhang, 1989

Shisan bu, 1989

Jiuguo, 1992

Shicao jiazu, 1993

Dao shen piao, 1995

Fengru feitun, 1996

Hong shulin, 1999

Shifu yuelai yue youmo, 2000

Tanxiangxing, 2001

Cangbao tu, 2003

Sishiyi pao, 2003

Shengsi pilao, 2006

Wa, 2009

Works in English

Explosions and Other Stories / edited by Janice Wickeri. – Hong Kong : Research Centre for Translations, Chinese University of Hong Kong, 1991

Red Sorghum : a Novel of China / translated from the Chinese by Howard Goldblatt. – New York : Viking, 1993. – Translation of Hong gaoliang jiazu

The Garlic Ballads : a Novel / translated from the Chinese by Howard Goldblatt. – New York : Viking, 1995. – Translation of Tiantang suantai zhi ge

The Republic of Wine / translated from the Chinese by Howard Goldblatt. – New York : Arcade Pub., 2000. – Translation of Jiuguo

Shifu, You’ll Do Anything for a Laugh / translated from the Chinese by Howard Goldblatt. – New York : Arcade Pub., 2001. – Translation of Shifu yuelai yue youmo

Big Breasts and Wide Hips : a Novel / translated from the Chinese by Howard Goldblatt. – New York : Arcade Pub., 2004. – Translation of Fengru feitun

Life and Death are Wearing Me Out : a Novel / translated from the Chinese by Howard Goldblatt. – New York : Arcade Pub., 2008. – Translation of Shengsi pilao

Change / translated by Howard Goldblatt. – London : Seagull, 2010. – Translation of Bian

Pow / translated by Howard Goldblatt. – London : Seagull, 2013

Sandalwood Death / translated by Howard Goldblatt. – Norman : Univ. of Oklahoma Press, 2013. – Translation of Tanxiangxing

Selected Stories by Mo Yan / translated by Howard Goldblatt. – Hong Kong : The Chinese University Press, 20-?. – (Announced but not yet published)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Awards & Prizes, The talk of the town

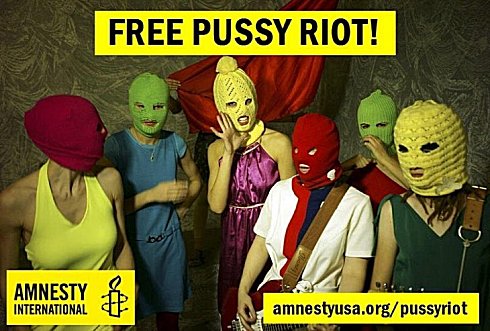

Pussy Riot:

Russian court orders conditional release of one,

other two jailed

The decision by a Moscow court to give Ekaterina Samutsevich a suspended sentence and release her while upholding jail sentences against Maria Alekhina and Nadezhda Tolokonnikova is only a half-measure in achieving justice for the three members of feminist punk group Pussy Riot, Amnesty International said.

“Any decision that shortens the wrongful detention of the three women is welcome. But no-one should be fooled – justice has not been done today. The government has introduced numerous new restrictions to freedom of expression in recent months. As this decision demonstrates, Russia’s judiciary is unlikely to offer much protection to those who fall foul of them”, said David Diaz-Jogeix, Europe and Central Asia Deputy Programme Director.

“The three women should not have been prosecuted in the first place. Maria Alekhina and Nadezhda Tolokonnikova should also be released immediately and unconditionally”, said David Diaz-Jogeix.

The organization considers the three convicted Pussy Riot members – Maria Alekhina, Ekaterina Samutsevich and Nadezhda Tolokonnikova – to be prisoners of conscience wrongfully prosecuted and convicted solely for the peaceful expression of their beliefs.

≡ Source: AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: REPRESSION OF WRITERS, JOURNALISTS & ARTISTS

Hallo Wereld

Hallo, kan iemand mij verstaan?

Alle mensen op de wereld,

Luister…

Luister even…

Ook vandaag lees ik

Weer voor uit,

Een van mijn gedichten.

Radio,

En televisie

Luister allemaal, vandaag de

Dag lees ik iets voor, wat ik al keren deed.

Pleun Andriessen

Pleun Andriessen is kinderstadsdichter van Tilburg

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Andriessen, Pleun, Archive A-B

Middeleeuws Iers gedicht

vertaald door Lauran Toorians

Dom-arcai fidbaidæ fál,

fom-chain loíd luin – lúad nad cél;

húas mo lebrán, ind línech,

fom-chain trírech inna n-én.

Fomm-chain coí menn – medair mass –

hi mbrot glass de dindgnaib doss.

Débrad! nom-choimmdiu coíma,

caín-scríbaimm fo roída ross.

Een wand van houtopstand kijkt neer op mij,

merelzang klink naar mij op – verhaal zonder pretentie;

boven mijn boekje, het gelinieerde,

klinken de trillers van de vogels naar mij op.

De heldere roep van de koekoek, lichtvoetig en vrolijk

in zijn grijze mantel, klinkt vanuit zijn bladerburcht.

Ach God, moge de Heer mij beschermen,

terwijl ik zo goed schrijf, onder aan de boshelling.

Middeleeuwse Ierse gedichten vertaald door Lauran Toorians

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: CELTIC LITERATURE, Lauran Toorians

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature